Abstract

Many people ascribe great value to self-esteem, but how much value? Do people value self-esteem more than other pleasant activities, such as eating sweets and having sex? Two studies of college students (Study 1: N=130; Study 2: N=152) showed that people valued boosts to their self-esteem more than they valued eating a favorite food and engaging in a favorite sexual activity. Study 2 also showed that people valued self-esteem more than they valued drinking alcohol, receiving a paycheck, and seeing a best friend. Both studies found that people who highly valued self-esteem engaged in laboratory tasks to boost their self-esteem. Finally, personality variables interacted with these value ratings. Entitled people thought they were more deserving of all pleasant rewards, even though they did not like them all that much (both studies); and people who highly value self-esteem pursue potentially maladaptive self-image goals, presumably to elevate their self-esteem (Study 2).

Keywords: self-esteem, self-image goals, entitlement, rewards, food, sex, money, friends, alcohol

Our dependency makes slaves out of us, especially if this dependency is a dependency of our self-esteem.

— Fritz Perls (1893-1970), developer of Gestalt therapy

Are people today addicted to self-esteem, as Fritz Perls suggested? Popular culture can shed light on addiction, which can in turn inform social science research (e.g., Halkitis, 2009; Hirschman, 1996). Judging by popular culture, there are some signs that people may be addicted to self-esteem. The self-esteem movement appears to be alive and well today, at least in more individualistic cultures. It starts young too. In cars, infants sit in seats with printed messages such as: “I AM VERY SPECIAL.” In schools, children see banners above mirrors such as: “YOU ARE LOOKING AT ONE OF THE MOST SPECIAL PEOPLE IN THE WHOLE WIDE WORLD!” In sports, all children “earn” trophies regardless of their actual performance, because they are all “winners.” The self-esteem movement targets adults too. Advertisers tell us that we “need,” “deserve, ” and are “entitled” to their products, as reflected in the original L’Oreal slogan: “Because I’m worth it.” There are also plenty of books containing the word “deserve” in the title, such as “Transformation: The Mindset You Need. The Body You Want. The Life You Deserve.” People even wear T-Shirts containing messages such as “I ♥ ME” and “I am the BEST Person EVER.” In summary, popular culture provides us many ways to boost our self-esteem.

Self-Esteem as a Pleasant Reward

Whether it is due to the self-esteem movement or other factors, self-esteem levels are increasing over time (Gentile, Twenge, & Campbell, 2010; Twenge, 2006; Twenge & Campbell, 2001; but see Trzesniewski & Donnellan, 2010, and response by Twenge & Campbell, 2010). Is the rise in levels of self-esteem accompanied by a rise in its importance to people? And if so, how much value do people place on self-esteem? Many theorists view self-esteem as a fundamental human need (Allport, 1955; Baumeister, Heatherton, & Tice, 1993; Maslow, 1968; Rogers, 1961; Rosenberg, 1979; Solomon, Greenberg, & Pyszczynski, 1991; Taylor & Brown, 1988), much like other needs such as food and sex. We propose that self-esteem can be considered a pleasant reward that people highly value, much like other pleasant rewards. A boost to one’s self-esteem feels good. The present research tests whether people place as much (or even more) value on self-esteem than they place on other pleasant rewards, such as sex, food, alcohol, money, or friends.

Testing For One Sign of Self-Esteem Addiction: Wanting More Than Liking

People can both want and like pleasant rewards. Wanting motivates approach and consumptive behavior, whereas liking is a hedonic preference. Although in the vast majority of cases people like what they want and want what they like, liking and wanting are dissociable systems, as pointedly observed in drug addiction. Drugs become increasingly ‘wanted’ without an attendant increase in ‘liking’ because they sensitize brain regions involved in wanting but not liking (Robinson & Berridge, 2003). The liking/wanting distinction can apply to other pleasant rewards besides drugs. For example, someone may want to eat a cookie, even though it does not taste that delicious when they eat it. If self-esteem has become “needed” today, then people may “want” it even more than they “like” it. Wanting more than liking self-esteem would be one sign that people might be “addicted” to it, a possibility we tested in the present research.

Role of Entitlement on Wanting and Liking

Given the importance of the liking/wanting distinction for pleasant rewards, entitlement could be a potentially important moderating variable. Entitled people think they are more deserving than other people of the good things in life and should be accorded “special treatment” because they are “special people” (Campbell, Bonacci, Shelton, Exline, & Bushman, 2004). Previous research shows that entitlement contributes to maladaptive behavior more than other component of narcissism (Bushman & Baumeister, 2002; Emmons, 1984, 1987). Based on previous literature, entitlement could moderate wanting and liking of rewards in one of two ways. One possibility is that entitlement is specifically associated with higher wanting than liking of self-esteem. This possibility follows from a previous suggestion that narcissistic people, who are also highly entitled, may be “addicted” to self-esteem (Baumeister & Vohs, 2001). A second possibility is that entitlement is associated with higher wanting than liking of all rewards, not just self-esteem. This possibility follows from the idea that entitled people feel they are more deserving of everything that is good in life (Campbell et al., 2004). Perhaps entitled people want these good things more than they actually like them, much like drug-addicted individuals want drugs more than they actually like them (Robinson & Berridge, 2003).

The Present Studies

The present research approaches the question of how much people value self-esteem by comparing its value with other pleasant rewards, such as eating a favorite food and engaging in a favorite sexual activity (Studies 1 and 2), as well as receiving a paycheck, seeing a best friend, and drinking alcohol (Study 2). Our participants were American college students. Most college students highly value all of these rewards. To test for possible signs of addiction to self-esteem, we measure both wanting and liking of self-esteem. We also test the moderating role of entitlement on wanting and liking.

If people truly want self-esteem, they will behave in ways to obtain it. Indeed, one indication of the value people put on self-esteem is the amount of effort they expend to maintain, enhance, and protect their self-esteem, evidenced in self-enhancing biases, defensive responses to self-threats, self-serving attributions for success and failure, and many other self-serving strategies that can enhance self-esteem (Baumeister, 1998; Dunning, Heath, & Suls, 2005; Taylor & Brown, 1988). Thus, the present research also tests the hypothesis that people who highly value self-esteem will pursue self-regulatory strategies to boost their self-esteem. We examine this self-esteem enhancing hypothesis in two ways, testing for both temporary situational and stable personal strategies. First, to test for temporary situational self-esteem enhancement, we examine whether people who highly value self-esteem engage in behavior within the laboratory to boost their self-esteem. Second, to test for more stable self-esteem enhancement, we test the hypothesis that people who highly value self-esteem relative to other pleasant rewards will report pursuing self-image goals in important self-regulatory domains. People who pursue self-image goals seek to have others recognize their positive qualities, allowing them to garner social benefits such as inclusion, acceptance, advancement, and status while at the same time avoiding social harms such as exclusion, rejection, and humiliation (Leary, 2007; Leary & Kowalski, 1990; Miller, 2006; Pyszczynski, Greenberg, Solomon, Arndt, & Schimel, 2004; Schlenker, 2003). Yet despite the potential for achieving these social benefits, self-image goals have intrapersonal and interpersonal costs, including disrupted social relationships (Crocker & Canevello, 2008), chronic negative affect (Crocker & Canevello, 2008), conflict with others (Moeller, Crocker, & Bushman, 2009), anxiety and dysphoria (Crocker, Canevello, Breines, & Flynn, 2010), and alcohol problems (Moeller & Crocker, 2009).

STUDY 1

Study 1 provides an initial test of the hypothesis that people value self-esteem more than other pleasant rewards. Participants indicated how much they wanted and liked three different rewards: food, sex, and self-esteem. Participants also completed the Narcissistic Personality Inventory (Raskin & Terry, 1988), which contains seven subscales (i.e., Entitlement, Authority, Self-Sufficiency, Superiority, Exhibitionism, Exploitiveness, and Vanity). We tested the unique effects of entitlement on wanting and liking pleasant rewards (including self-esteem) after controlling for the other components of narcissism. Participants were also given a chance to boost their self-esteem in the lab by waiting to have their “intelligence” test rescored using an algorithm that “usually gives a higher score.”

Method

Participants

Participants were 130 University of Michigan students (Mage=18.8; 55% female; 72% Caucasian, 5% African American, 15% Asian American; 8% other) who received course credit.

Procedure

Participants first completed the 40-item Narcissistic Personality Inventory (Raskin & Terry, 1988). We were primarily interested in the Entitlement subscale, which consists of 6 forced choice items (e.g., “If I ruled the world it would be a much better place” versus “The thought of ruling the world frightens the hell out of me”; Cronbach α=.57). To examine the unique effect of entitlement, the other narcissism subscales [i.e., Authority α=.65), Self-Sufficiency (α=.44), Superiority (α=.55), Exhibitionism (α=.56), Exploitiveness (α=.52), and Vanity (α=.47)] were used as covariates in the analyses. We note that such relatively poor internal consistencies are common for these NPI subscales (Campbell et al., 2004).

Our main interest was comparing liking and wanting of self-esteem vis-à-vis other pleasant rewards. For this purpose, participants completed a modified version of the Sensitivity to Reinforcement of Addictive and other Primary Rewards scale (Goldstein et al., 2010), originally designed to test preference for addictive drugs over other pleasant rewards. Participants in the current study were asked to think about their favorite food, sexual activity, and self-esteem building experience (e.g., receiving a good grade, receiving a compliment from others). For each reward, participants rated how much they “liked” it [“How pleasant would it be to eat it (food), do it (sex), or have that experience (self-esteem)?”] and how much they “wanted” it [“How much do you want to eat it (food), do it (sex), or have that experience (self-esteem)?”]. Participants rated how much they wanted and liked each reward in four situations: “currently,” “in general,” the last time their self-esteem was high (“during good times”), and the last time their self-esteem was low (“during bad times”). All ratings were made using 5-point scales (1=not at all to 5=extremely). Because results were similar across the four situations, we combined them for all analyses in both studies.

Finally, participants completed a purported test of intellectual ability called the Remote Associates Test (Mednick & Mednick, 1967). For each item on the test, three “clue” words are shown (e.g., ACHE, HUNTER, CABBAGE). Participants have to think of a fourth word that connects the other three “clue” words in a meaningful way (e.g., HEAD). The test is timed, which was said to factor into their score. Afterwards, participants were asked if they wanted to wait 10 minutes to have their test re-scored using a new scoring algorithm that usually yields higher scores. Thus, participants could get a self-esteem boost in the lab, but it would cost them 10 minutes of their own time. A debriefing followed.

Results & Discussion

Data were analyzed using a 3 (Reward: food, sex, self-esteem) × 2 (Value: like, want) repeated measures ANOVA. Entitlement and the other narcissism subscales (centered) were subsequently entered as continuous moderators in the model. Significant main effects were followed by Bonferroni-corrected pairwise comparison tests, and significant interactions were followed by paired t-tests.

Valuing Different Rewards

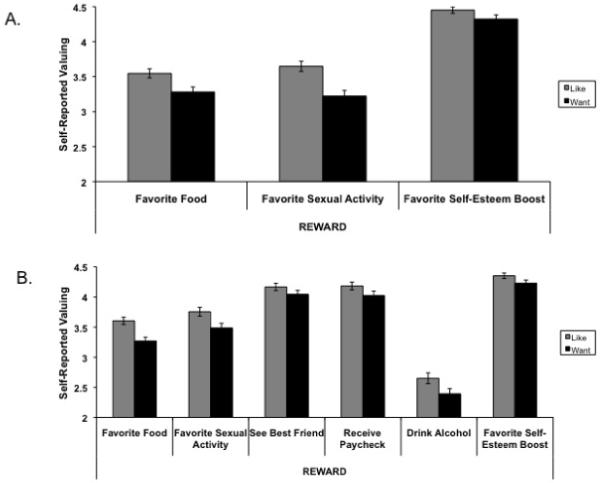

Results revealed a large and statistically significant main effect for type of Reward, F(2,127)=137.77, p<.001, ή2=.69 (Figure 1A). Pairwise tests showed that participants valued their favorite self-esteem building experience over their favorite food (Mdiff=0.97, p<.001), and over their favorite sexual activity (Mdiff=0.95, p<.001). Participants placed equal value on food and sex (Mdiff=0.02, p=1.00).

Figure 1.

Mean (± standard error) self-reported liking and wanting of the different rewards: (A) eating a favorite food, engaging in a favorite sexual activity, and receiving a favorite self-esteem boost (Study 1); (B) eating a favorite food, engaging in a favorite sexual activity, seeing a best friend, receiving a paycheck, and receiving a favorite self-esteem boost (Study 2). Liking scores were greater than wanting scores for all rewards, but the difference was smallest for self-esteem. Wanting and liking of a self-esteem boost exceeded wanting and liking for any other reward.

Liking Versus Wanting Rewards

A main effect of Value, F(1,128)=85.59, p<.001, ή2=.40, showed that participants liked the pleasant rewards more than they wanted them (Figure 1A). A significant Reward × Value interaction, F(2,127)=18.51, p<.001, ή2=.23, showed that although liking exceeded wanting for all rewards, this difference was lower for self-esteem, t(128)=3.22, p<.002, compared with food t(128)=5.89, p<.001, and especially sex, t(128)=10.14, p<.001. One indicator of addiction is that people want something more than they like it (Robinson & Berridge, 2003). Thus, if people are addicted to anything, they are more addicted to self-esteem than to food or sex.

Behavioral Validation

We next examined whether wanting of self-esteem predicts engaging in a behavioral strategy to boost self-esteem. This behavioral measure was assessed after participants reported on their liking and wanting of self-esteem. Logistic regression analysis showed that the higher the difference between wanting and liking self-esteem, the more likely participants were to wait 10 extra minutes to have their Remote Associates Test (that purportedly measured intelligence) re-scored using the new algorithm that would most likely yield a higher score (χ2= 4.78, b=1.02, p<.05). Thus, wanting self-esteem more than liking it, which would be reflective of addiction, predicted whether people would sacrifice their own time to wait for a potentially higher test score that would boost their self-esteem.

Interactions with Entitlement

A significant Value × Entitlement interaction, F(1,127)=8.85, p<.004, ή2=.07, showed that entitlement related positively to wanting (with liking controlled, β=.26, p<.004) and negatively to liking (with wanting controlled, β=−.22, p<.014). When we controlled for the other Narcissistic Personality Inventory subscales, the Value × Entitlement interaction remained significant, F(1,121)=5.70, p<.019, ή2=.05. In contrast, no other NPI subscale interacted with Value to influence liking or wanting ratings (Fs<0.56, ps>.45). Thus, it appears that a sense of entitlement leads people to want positive rewards even if they do not necessarily like them. The Reward × Value × Entitlement interaction did not reach significance, F(2,126)=0.84, p>.43, speaking against the idea that entitled people especially want self-esteem. Entitled people want food and sex just as much as they want self-esteem. The Reward × Entitlement interaction was also nonsignificant, F(2,126)=0.91, p>.40, suggesting that it is not merely that entitled people value all rewards but that they actively ‘want’ them. Taken together, these results suggest that entitled people want the good things in life (e.g., food, sex, self esteem), even if they do not like them all that much. Whether entitled people like the good things in life seems less important than the fact that they want them. This finding is consistent with the idea that entitled people think they are more deserving of the good things in life than others (Campbell et al., 2004).

Finally, we inspected moderation with gender. There was a significant reward × gender interaction, F(2,125)=6.54, p<.002, ή2=.10. This interaction was explained by higher valuing of sex among men than women, t(126)=3.46, p<.001, but no gender differences for either food or self-esteem (ts<1.36, ps>.17). Paired comparisons showed that self-esteem trumped food and sex in both genders (ts>5.29, ps<.001), consistent with the Reward main effect.

STUDY 2

One alternative explanation for the results of Study 1 is that a self-esteem boost could have consequences beyond positive feelings. For example, a good grade could increase one’s odds of securing a good job or being admitted into graduate school. A compliment from someone could be an indicator of social belonging (e.g., Baumeister & Leary, 1995). Thus, in Study 2 we included rewards besides sex and food to help rule out this alternative explanation: receiving a paycheck (to approximate success in life) and seeing a best friend (to approximate social belonging). Finally, we included drinking alcohol, given the core relevance of the liking/wanting distinction to addictive substances. These additional rewards are valuable to most people, but especially to college students who often lack stable income, are often separated from their childhood friends, and are often too young to legally drink alcohol (the legal drinking age is 21, and participants in our study were about 19 years old, on average).

Another limitation of Study 1 is that recently receiving some of these rewards may make them less valuable. Therefore, Study 2 controlled for when participants last received a paycheck, saw a best friend, drank alcohol, ate, had sex, and experienced a self-esteem boost. These latter analyses accounted for the possibility that, for example, recently receiving a self-esteem boost renders subsequent self-esteem boosts less valuable.

Study 2 also sought to replicate the higher wanting, but lower liking, effects observed for entitlement in Study 1. In addition to corroborating our previous effects, Study 2 extended Study 1 by including other pertinent individual difference measures. We included a measure of trait self-esteem, the Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965), to test whether the desire for self-esteem boosts depends upon whether individuals have chronically low or high levels of self-esteem. We also included measures of academic and friendship self-image goals, which are goals to construct or inflate desired self-views in these domains (Crocker & Canevello, 2008). We wanted to test whether people who highly value self-esteem boosts pursue potentially maladaptive self-image goals, presumably to elevate their self-esteem.

Study 2 also contained a different behavioral measure for boosting self-esteem in the lab—participants could make self-serving judgments about the likelihood of bad future events (e.g., “I will have a heart attack before age 40”) by denying that such events would happen to them. We predicted that people who highly value self-esteem would make more self-serving judgments than others by predicting fewer bad future events.

Method

Participants

Participants were 152 University of Michigan students (Mage=18.7; 60% female; 74% Caucasian, 4% African American, 10% Asian American; 12% other) who received course credit.

Procedure

First, participants completed trait measures. As in Study 1, they completed the Narcissistic Personality Inventory (Raskin & Terry, 1988), and we were again especially interested in the entitlement subscale (Cronbach α=.42). However, we again controlled for the other NPI subscales in the applicable analyses [Authority (α=.53), Self-Sufficiency (α=.40), Superiority (α=.44), Exhibitionism (α=.51), Exploitiveness (α=.49), and Vanity (α=.66). Trait self-esteem was measured using the Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965) (e.g., “I feel that I have a number of good qualities”; 1=strongly disagree to 4=strongly agree; Cronbach α=.86). We assessed self-image goals with the measure developed by Crocker and Canevello (2008) (e.g., In the past week in the area of [academics or friendships], how often did you …. “get others to recognize or acknowledge your positive qualities”; 1=not at all to 5=extremely; Cronbach α=.89), obtained for both academics and friendships. Because academic and friendship self-image goals were highly correlated (r=.66, p<.001), we averaged them to create a single index of these goals.

Next, they completed the same Reinforcement of Addictive and other Primary Rewards scale that was used in Study 1, but with three additional rewards: receiving a paycheck, seeing a best friend, and drinking alcohol. Participants also responded to individual questions assessing the amount of time since they last received a paycheck (weeks), saw a best friend (days), drank alcohol (days), ate (hours), had sex (days), received a high score on a class assignment or test (days), and received a compliment from someone (days).

Finally, participants rated the likelihood (1=will never happen to 7=will surely happen) that they would experience eight negative life events (e.g., “being burglarized,” “having a spouse, partner, or child who falls terminally ill”; Cronbach α=.75; adapted from Weinstein, 1980). Participants could boost their self-esteem by making self-serving judgments that the bad events were unlikely to happen to them. A debriefing followed.

Results & Discussion

Data were analyzed using a 6 (Reward: food, sex, money, alcohol, friends, self-esteem) × 2 (Value: like, want) repeated measures ANOVA. Entitlement and the other NPI subscales (centered) were subsequently entered as continuous moderators in the model, as done in Study 1. Following a significant main effect of reward, we compared each reward with self-esteem. This approach was guided by our a priori hypotheses on the value people ascribe to self-esteem, and also by our results from Study 1 (in which self-esteem trumped all other rewards by a statistically impressive amount); furthermore, pairwise comparisons among all six rewards would have been overly restrictive (15 individual comparisons). Instead, comparing each reward to self-esteem resulted in five comparisons; with Bonferroni correction, significance for these analyses was established at p<.01. Finally, the parallel follow-up analyses to Study 1 were conducted to inspect interactions with entitlement.

Valuing Different Rewards

Consistent with the results of Study 1, self-esteem trumped all other rewards. A significant and statistically large main effect of Reward, F(5,142)=81.97, p<.001, ή2=.74 (Figure 1B), showed that participants valued their favorite self-esteem building experience over all other rewards (.17<Mdiff<1.75, all p<.007). Thus, Study 2 replicated the finding that people value a self-esteem boost over their favorite food and sexual activity. Study 2 extended the results of Study 1 by showing that people also value a self-esteem boost over drinking alcohol, seeing a best friend, and receiving a paycheck. Moreover, the effect did not depend on how recently participants had received the particular reward.

Liking Versus Wanting Rewards

A significant main effect of Value, F(1,146)=103.12, p<.001, ή2=.41, again showed that liking ratings exceeded wanting ratings. A significant Reward × Value interaction, F(5,142)=7.35, p<.001, ή2=.21, showed that liking exceeded wanting for all rewards, although the difference between liking and wanting was smaller for self-esteem, money, and friends (4.49<t<5.04, p<.001), than for food, sex, and alcohol (6.90<t<7.75, p<.001). As in Study 1, the difference for self-esteem was smaller than the differences for food and sex. The findings from Study 2 indicate similar effects for alcohol. This finding is noteworthy given research showing that a fairly large percentage of college students meet the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) criteria for alcohol abuse while in college (e.g., McCabe, West, & Wechsler, 2007). In fact, college students have more alcohol-related problems than do their peers who are not attending college (e.g., Slutske, 2005).

Behavioral Validation

Our next analyses sought to determine if wanting self-esteem is associated with self-enhancement, further testing whether people who ‘want’ self-esteem behave in ways to obtain it. Regression analysis showed that the higher the wanting self-esteem minus liking self-esteem score, the less willing participants were to acknowledge that negative life events could happen to them (β=−0.17, p<.05). Thus, wanting self-esteem more than liking it predicted making self-serving judgments about the likelihood of future negative events.

Interactions with Personality

A significant Value × Entitlement interaction, F(1,144)=7.13, p<.008, ή2=.05, replicated the pattern of results from Study 1, showing that entitlement related positively to wanting (with liking controlled, β=.20, p<.014) and negatively to liking (with wanting controlled, β=−.22, p<.007). The Reward × Value × Entitlement interaction was again nonsignificant, F(5,140)=1.07, p>.38, speaking against the idea that entitled people especially want self-esteem. Instead, results again suggest that entitled people want more of all the good things in life, even though they do not necessarily like them. The Reward × Entitlement interaction, despite initially reaching significance F(5,140)=2.79, p<.020, ή2=.09, did not survive the lower-bound correction for violation of sphericity (p>.12). When we controlled for the other narcissism subscales, the Value × Entitlement interaction was still significant, F(1,138)=7.66, p<.006, ή2=.051

To determine whether valuing of self-esteem depends on chronically high or low levels, we included the centered (trait) self-esteem score (Rosenberg, 1965) as a continuous covariate in the initial 6 × 2 model. Trait self-esteem interacted with reward, F(5,141)=4.57, p<.001, This interaction was explained by trait self-esteem’s positive associations with valuing food (β=.18, p<.019) and friends (β=.36, p<.001), but negative association with valuing alcohol (β=−.19, p<.014). Associations did not emerge for the other three rewards (βs<.07, ps>.43). The link between self-esteem and valuing friends is not surprising. Research has shown that social relationships are an important source of self-esteem (e.g., Oishi, 2010). Trait self-esteem also interacted with Value, F(1,145)=10.69, p<.001, ή2=.07. This interaction was explained by trait self-esteem’s positive association with liking (β=.72, p<.001) and negative association with wanting (β=−.42, p<.008). This finding may reflect the fact that trait self-esteem is highly associated with general positive feelings (Pelham & Swann, 1989). Note that this pattern of results is opposite to that of entitlement.

Finally, we also examined gender differences in the observed effects. Consistent with Study 1, the reward × gender interaction reached significance, F(5,141)=4.03, ή2=.13, p<.002. Men valued sex more than did women, t(148)=3.10, p<.002, and women valued friends more than did men, t(149)=2.10, p<.038; other gender effects were nonsignificant (ps>.29). Interestingly, paired comparisons showed that whereas men valued self-esteem more than the five other rewards (ts>2.28, p<.05), women’s ratings of self-esteem did not differ from money, t(89)=1.78, p>.07, or friends, t(90)=1.17, p>.24).

Associations with Self-Image Goals

We examined whether people who highly value self-esteem pursue self-image goals. After covarying out the influence of the other pleasant rewards (through residuals), self-image goals positively related to valuing of self-esteem (β=.16, p<.05). Thus, people who highly value self-esteem boosts also pursue self-image goals to construct and inflate desired self images (Crocker & Canevello, 2008; Crocker & Park, 2004).

General Discussion

Many people highly value self-esteem. It feels good, and people try to boost it when possible. Consistent with our hypotheses, the current studies revealed, for the first time, that people value a self-esteem boost (e.g., being praised, receiving a high grade, etc.) over other pleasant rewards (e.g., eating their favorite food, drinking alcohol, engaging in their favorite sexual activity, seeing their best friend, or receiving their paycheck). Moreover, when people ‘want’ self-esteem more than they ‘like’ it, they pursue behavioral strategies to obtain it. Both men and women valued self-esteem more than sex and food. Men also valued self-esteem more than money, friends, and alcohol, whereas women also valued self-esteem more than alcohol. Collectively, these findings lend new credence to the view of self-esteem as an essential need (Allport, 1955; Baumeister et al., 1993; Maslow, 1968; Rogers, 1961; Rosenberg, 1979; Solomon et al., 1991; Taylor & Brown, 1988).

Despite its high subjective value, a question persists about whether boosting self-esteem has the potential for objective benefits to the self and others. Although some perspectives have posited essential functions for self-esteem, such as signaling belongingness (Leary & Baumeister, 2000; Leary, Tambor, Terdal, & Downs, 1995) or protecting oneself against existential anxiety (Greenberg, Pyszczynski, Solomon, & Pinel, 1993; Pyszczynski et al., 2004), other perspectives have argued that high self-esteem does little more than temporarily increase positive affect (Baumeister, Campbell, Krueger, & Vohs, 2003). Moreover, as revealed in the current research, people who highly value self-esteem boosts reported pursuing self-image goals to construct, maintain, and inflate desired images of the self (Crocker & Canevello, 2008). Unfortunately, pursuing such goals often leads to interpersonal difficulties (Crocker & Canevello, 2008; Crocker et al., 2010; Moeller & Crocker, 2009; Moeller et al., 2009). Thus, high valuing of self-esteem boosts may help shed light on how such problematic interpersonal and intrapersonal processes unfold.

This research also casts entitlement in a new light. Normally, people want only those things they like. Entitled people, in contrast, want and believe they deserve everything good in life, even if they do not necessarily like these things. In the present research, entitled people not only wanted self-esteem, they also wanted sex, good food, alcohol, friends, and money. This was not true of the other components of narcissism—only entitlement. Future research could test whether the high wanting that characterizes entitled people also underlies their exploitativeness or other maladaptive interpersonal strategies. For example, entitled men, while thinking they ‘want’ or deserve sex, might exploit or demean women to obtain it (Bushman, Bonacci, Van Dijk, & Baumeister, 2003). This type of study becomes all the more important considering that the current results showed men to value (both like and want) sex more than women.

Limitations

The primary limitation of this research is that we had to rely upon self-reports to compare the value of self-esteem with the value of other pleasant rewards. We note, however, that extending the methodology of the present studies to a laboratory choice paradigm (e.g., providing participants the choice between a favorite sexual activity and favorite self-esteem boost) would be incredibly challenging. Nevertheless, to bolster our self-report findings, we included behavioral measures in both studies. Study 1 showed that people who highly valued self-esteem were more willing to wait 10 minutes for their “intelligence” test to be rescored in hopes of receiving a higher score (and presumably get a self-esteem boost). Study 2 showed that people who highly valued self-esteem were more likely to boost their self-esteem by judging that bad events would not happen to them in the future.

Another limitation is that we are unable to know what kinds of self-esteem boosts (or other rewards) people were considering. We decided on this design because some of the content areas were sensitive (especially sexual activities, and alcohol consumption in minors), and we wanted to ensure that participants would be comfortable thinking about their favorite activity even if it was not socially desirable. However, it would be interesting for future studies to record and possibly content-analyze the types of rewards (especially self-esteem boosts) people consider.

Another limitation is that we do not presently know whether the current results generalize to other cultures. The participants in both of our studies were American college students. Previous research has shown that people from individualistic cultures self-enhance more than do people from collectivist cultures (Heine & Hamamura, 2007; Heine, Lehman, Markus, & Kitayama, 1999; but see Gaertner, Sedikides, & Chang, 2008). In addition, self-esteem levels are higher among today’s young adults than among young adults in previous generations (Gentile et al., 2010; Twenge & Campbell, 2001; but see Trzesniewski & Donnellan, 2010, and response by Twenge & Campbell, 2010). Thus, future studies are needed to determine whether these findings generalize to people of different ages and to people from collectivist cultures.

Conclusions

In summary, the current studies showed that the subjective value of self-esteem boosts surpasses the subjective value of other pleasant rewards, including food, alcohol, sex, money, and friends. People who highly value self-esteem also engage in self-serving behavior to boost their self-esteem. Moreover, people who highly value self-esteem also pursue self-image goals to boost their self-esteem, which can lead to conflict with others (e.g., Moeller, Crocker, & Bushman, 2009). Overall, our findings shed new and interesting light on just how important it is for people to feel worthy and valuable.

The current studies also show that entitled people want all of the good things in life, even if they do not particularly like them. Of course we should enjoy the good things in life, but not so much that we want them more than we like them. We do not want to become addicted to self-esteem or other rewards, or we will become “slaves” to them, to borrow the words of Frtiz Perls.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grants R01MH058869 from the National Institute of Mental Health to JC, and 1F32DA030017-01 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to SJM. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

1Unlike Study 1, however, two additional subscales interacted with Value. These included a Value × Exhibitionism interaction, F(1,138)=5.78, p<.018, ή2=.04, and a Value × Self-Sufficiency interaction, F(1,138)=15.31, p<.001, ή2=.10. These interactions generally mirrored the effects observed for entitlement, such that these NPI subscales were positively related to wanting (both Exhibitionism and Self-Sufficiency: β=.18, p<.032) and were negatively related to liking (Self-Sufficiency: β=−.18, p<.024; and a trend for Exhibitionism: β=−.12, p<.14). However, these results need to be interpreted with caution, given they are post-hoc (not hypothesized a priori) and did not emerge in Study 1.

References

- Allport GW. Becoming. Yale University Press; New Haven, CT: 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF. The self. In: Gilbert DT, Fiske ST, Lindzey G, editors. The Handbook of Social Psychology. Vol. 1. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1998. pp. 680–740. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Campbell JD, Krueger JI, Vohs KD. Does high self-esteem cause better performance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles? Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 2003;4(1):1–44. doi: 10.1111/1529-1006.01431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Heatherton TF, Tice DM. When ego threats lead to self-regulation failure: Negative consequences of high self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;64(1):141–156. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.64.1.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Vohs KD. Narcissism as addiction to esteem. Psychological Inquiry. 2001;12(4):206–210. [Google Scholar]

- Bushman BJ, Baumeister RF. Does self-love or self-hate lead to violence? Journal of Research in Personality. 2002;36(6):543–545. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.1.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Canevello A. Creating and undermining social support in communal relationships: The role of compassionate and self-image goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;95(3):555–575. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.95.3.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Canevello A, Breines JG, Flynn H. Interpersonal goals and change in anxiety and dysphoria in first-semester college students. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2010;98:1009–1024. doi: 10.1037/a0019400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Park LE. The Costly Pursuit of Self-Esteem. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130(3):392–414. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.3.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunning D, Heath C, Suls JM. Flawed self-assessment: Implications for health, education, and the workplace. Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 2005;5:69–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-1006.2004.00018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmons RA. Factor analysis and construct validity of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1984;48(3):291–300. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4803_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmons RA. Narcissism: Theory and measurement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;52(1):11–17. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaertner L, Sedikides C, Chang K. On pancultural self-enhancement: Well-adjusted Taiwanese self-enhance on personally valued traits. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2008;39(4):463–477. [Google Scholar]

- Gentile B, Twenge JM, Campbell WK. Birth cohort differences in self-esteem, 1988-2008: A cross-temporal meta-analysis. Review of General Psychology. 2010;14:261–268. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein RZ, Woicik PA, Moeller SJ, Telang F, Jayne M, Wong C, et al. Liking and wanting of drug and non-drug rewards in active cocaine users: the STRAP-R questionnaire. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2010;24(2):257–266. doi: 10.1177/0269881108096982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg J, Pyszczynski T, Solomon S, Pinel E. Effects of self-esteem on vulnerability-denying defensive distortions: Further evidence of an anxiety-buffering function of self-esteem. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1993;29(3):229–251. [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis PN. Methamphetamine addiction: Biological foundations, psychological factors, and social consequences. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Heine SJ, Hamamura T. In Search of East Asian Self-Enhancement. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2007;11(1):1–24. doi: 10.1177/1088868306294587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heine SJ, Lehman DR, Markus HR, Kitayama S. Is there a universal need for positive self-regard? Psychological Review. 1999;106(4):766–794. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.106.4.766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschman EC. Professional, personal, and popular culture perspectives on addiction. In: Hill RP, editor. Marketing and consumer research in the public interest. Sage Publications, Inc.; Thousand Oaks, CA, US: 1996. pp. 33–53. [Google Scholar]

- Leary MR. Motivational and Emotional Aspects of the Self. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:317–344. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leary MR, Baumeister RF. The nature and function of self-esteem: Sociometer theory. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Vol. 32. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2000. pp. 1–62. [Google Scholar]

- Leary MR, Kowalski RM. Impression management: A literature review and two-component model. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107(1):34–47. [Google Scholar]

- Leary MR, Tambor ES, Terdal SK, Downs DL. Self-esteem as an interpersonal monitor: The sociometer hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;68(3):518–530. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow AH. Motivation and personality. Harper & Row; New York: 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Miller DT. An invitation to social psychology. Thompson; Belmont, CA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Moeller SJ, Crocker J. Drinking and desired self-images: Path models of self-image goals, coping motives, heavy-episodic drinking, and alcohol problems. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23(2):334–340. doi: 10.1037/a0015913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller SJ, Crocker J, Bushman BJ. Creating hostility and conflict: Effects of entitlement and self-image goals. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2009;45(2):448–452. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyszczynski T, Greenberg J, Solomon S, Arndt J, Schimel J. Why Do People Need Self-Esteem? A Theoretical and Empirical Review. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130(3):435–468. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.3.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raskin R, Terry H. A principal-components analysis of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory and further evidence of its construct validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54(5):890–902. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.5.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Berridge KC. Addiction. Annual Review of Psychology. 2003;54:25–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers CR. On becoming a person. Houghton Mifflin; Boston: 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ: 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Conceiving the self. Basic Books; New York: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Ross D, Kincaid H, Spurrett D, Collins P, editors. What is addiction? MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Schlenker BR. Self-presentation. In: Leary MR, Tangney JP, editors. Handbook of self and identity. Guilford Press; New York, NY, US: 2003. pp. 492–518. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon S, Greenberg J, Pyszczynski T. A terror management theory of social behavior: The psychological functions of self-esteem and cultural worldviews. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 24. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 1991. pp. 91–159. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE, Brown JD. Illusion and well-being: A social psychological perspective on mental health. Psychological Bulletin. 1988;103(2):193–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trzesniewski KH, Donnellan MB. Rethinking “generation me”: A study of cohort effects from 1976–2006. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2010;5:58–75. doi: 10.1177/1745691609356789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twenge JM. Generation Me: Why today’s young Americans are more confident, assertive, entitled--and more miserable than ever before. Free Press; New York, NY, US: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Twenge JM, Campbell WK. Age and birth cohort differences in self-esteem: A cross-temporal meta-analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2001;5(4):321–344. [Google Scholar]

- Twenge JM, Campbell WK. Birth cohort differences in the monitoring the future dataset and elsewhere: Further evidence for Generation Me—Commentary on Trzesniewski & Donnellan (2010) Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2010;5(1):81–88. doi: 10.1177/1745691609357015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]