Abstract

Quality of nursing care across hospitals is variable, and this variation can result in poor patient outcomes. One aspect of quality nursing care is the amount of necessary care omitted. This paper reports on the extent and type of nursing care missed and the reasons for missed care. The MISSCARE Survey was administered to nursing staff (n = 4086) who provide direct patient care in ten acute care hospitals. Missed nursing care patterns, as well as reasons for missing care (labor resources, material resources, and communication) were common across all hospitals. Job title (i.e., RN vs. NA), shift worked, absenteeism, perceived staffing adequacy, and patient workloads were significantly associated with missed care. The data from this study can inform quality improvement efforts to reduced missed nursing care and promote favorable patient outcomes.

The quality of nursing care is one determinant of patient outcomes, according to the hallmark Institute of Medicine (IOM) studies that describe the status of the healthcare delivery system.1, 2 The decision by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to disallow reimbursement for selected adverse patient outcomes places greater accountability on healthcare providers to prevent such complications.3 These adverse patient outcomes include pressure ulcers, hospital-acquired infections and patient falls, which are closely linked to the delivery of nursing care.

The nursing care of patients in acute care hospitals is known to be variable, yet few studies have quantified these differences. When considering the IOM framework of quality care gaps, the primary policy focus has been to avoid errors of commission.1 However, a report by the Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality (AHRQ) states that “errors of omission are more difficult to recognize than errors of commission, but likely represent a larger problem.” 4 Conceptually, missed nursing care is considered an error of omission5 and is defined as any aspect of required patient care that is omitted (either in part or whole) or significantly delayed.6 Motivated by this knowledge gap, the purpose of this study was to identify the type and reasons for care being missed in acute care settings. This paper also explores predictors of the amount of missed nursing care including staff characteristics (i.e. gender, age, education, experience in role), work schedules (shift worked, experience in role, length of shift, weekly worked hours, absenteeism and unit type), and staffing variables (both perceived adequacy of staffing and reported number of patients cared for). The findings from this study can aid in the development of quality improvement approaches to minimize reduced care and improve patient outcomes.

Previous Studies

Selected aspects of missed nursing care have been investigated previously, including the impact of failure to ambulate patients,7-13 the assurance of providing adequate hydration and nutrition to patients following hospitalization,14 and missed medication administration.15-17 Callen and colleagues identified that 73% of patients hospitalized on a medical unit did not ambulate at all during their stay.6 A study of nutritional status of patients found that nearly 40% of hospitalized patients were malnourished and few had a nutrition plan.13 These studies, however, do not describe variation in care across settings, nor do they identify factors associated with missed care.

In Sochalski's examination, the quality of nursing care was significantly related to nurse-reported rates of unfinished care.18 A Swiss team investigated “rationed nursing care,” which occurs when nurses lack sufficient time to provide necessary care. Although they reported a low rate of rationed care, occurrence of rationed care (i.e., missed care) was related to poor patient outcomes (e.g. medication errors, patient falls, infections, pressure ulcers).19

Kalisch used focus group methodology to identify the scope of care missed in the acute care setting.20 Findings revealed nine areas of missed care (ambulation, turning, delayed or missed feedings, patient teaching, discharge planning, emotional support, hygiene, intake and output documentation and surveillance) and seven reasons for missing that care (too few staff, poor use of existing staff resources, time required for the nursing intervention, poor teamwork, ineffective delegation, habit, and denial). Following this study, the MISSCARE Survey was developed to measure the phenomena empirically.21 The survey has two parts: nursing staff perceptions of aspects of nursing care missed, and the perceived reasons for missing care. The results of the first quantitative study using the MISSCARE Survey identified that nursing interventions, basic care, and care planning were cited as missed by greater than 70% of respondents. However, a clearer examination of missed nursing care in a larger sample of hospitals is necessary to examine the size and scope of the problem, as well as propose solutions to reduce missed care and improve quality.

Conceptual Framework

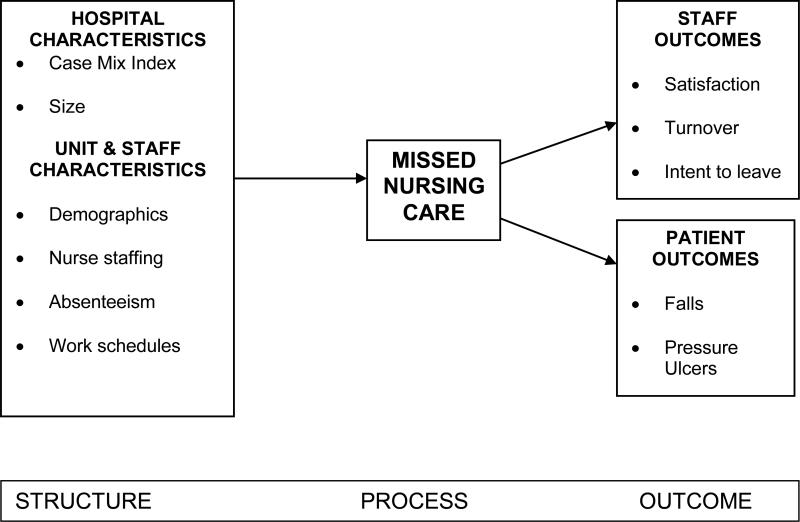

The Missed Nursing Care Model serves as a conceptual framework for this study (see Figure 1). This framework examines three concepts: structure (e.g., hospital, patient care unit and individual nursing staff characteristics); process (missed nursing care); and outcomes (staff outcomes, including job satisfaction with current position and with occupation, and patient outcomes, such as patient falls and pressure ulcer prevalence). These variables were selected following the focus group and preliminary survey studies previously reported.20, 21 Several unit and staff characteristics have been linked to patient outcomes. Increased nurse staffing levels have been linked to a reduction in several patient outcomes including mortality rates, 22, 23 infection rates 24, 25, pressure ulcers 26, and falls. 27 Furthermore, when patient load and nurse absenteeism rates are high, patient mortality rates are reportedly higher.28 Work schedules have also been linked to patient outcomes. Studies identified a direct and negative impact on patient outcome due to impaired judgment, slower response time, decreased clinical decision making by nurses, increased risk of error and near misses, and decreased vigilance.29, 30 Although the link between unit and staff characteristics and patient outcomes has been well established, few studies have focused on the process of nursing care that results in better outcomes.31 The nursing process variable utilized in this study is missed nursing care.

Figure 1.

Missed Nursing Care Model

For this study, we focused on identifying the levels and types of missed nursing care and reasons for missed care across hospitals. We also examines the relationship between unit staff characteristics (gender, age, education, experience in role), work schedules (shift worked, length of shift, weekly worked hours, absenteeism and unit type), staffing variables (perceived level of adequate staffing and number of patient cared for) and missed nursing care.

Research Questions

The purpose of this study was to confirm the findings of a previous small sample study in a larger sample of diverse hospitals. The specific study questions were:

What is the amount of nursing care being missed in acute care hospitals?

What are the reasons for care being missed?

Are the patterns of missed nursing care and its reasons common across hospitals?

What characteristics of the nursing unit's staff members, work schedules and perceptions of staffing adequacy are associated with the amount and type of missed nursing care?

METHODS

Settings and Participants

The sample for this study consisted of staff registered nurses (RNs) (n = 3,143) and nursing assistants (NAs) (n = 943) providing direct patient care in medical, surgical, rehabilitation, intermediate and intensive care units in ten hospitals of varying sizes and organizational forms (e.g., size, ownership) located in the Midwest. Licensed practical nurses were excluded from the analysis due to a small sample size (< 2% of the sample). Data were collected in November 2008 through April 2009. The overall response rate was 59.8% (61.8% for RNs and 53.4% for NAs).

Instrument

We employed the survey method, using the MISSCARE Survey, in order to protect anonymity and to be able to conduct multi-site comparison. The MISSCARE Survey was the instrument used to assess nursing staff perceptions of both missed care (Part A) and the reasons for missed care (Part B). The survey included questions about staff characteristics (e.g., education, job experience, gender, age), work schedules (shift, and hours worked), and staffing (absenteeism, perceived staffing adequacy, and patient workloads).

In Part A, RNs and NAs were asked to identify how frequently nursing care elements are missed by all of the nursing staff on their unit. Respondents were asked to check the best response: always missed, frequently missed, occasionally missed, or rarely missed. In Part B (Reasons for Missed Care), RNs and NAs were asked to indicate the reasons nursing care is missed. Respondents were asked to grade the relative importance for each reason: significant reason, moderate reason, minor reason, or not a reason for missed care.

Validity and reliability of the MISSCARE survey were previously reported. 21 The content validity index was 0.89 and test-retest reliability for Part A of the tool was 0.88 (p < 0.001). We previously performed exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis on Part B, and three factors emerged: (labor resources, material resources, and communication), with a range of factor loadings from 0.35 to 0.85. Cronbach's alpha coefficients ranged from 0.71 to 0.86.

Procedures

After Institutional Review Board approval at each facility, and securing support from nursing directors and managers, a survey packet—which included a letter explaining the study and the anonymity of their responses, the MISSCARE Survey, and return envelope—were placed in staff members’ mail boxes. Included in the packet was a candy bar as an incentive for survey completion. Units with a response rate greater than 50% received a pizza party as an additional incentive. Responses were collected in locked boxes located on the units. Reminders were sent to all staff approximately two weeks into the survey collection in an effort to increase response rates. Data were collected within a four week timeframe within each of the hospitals.

Data Analysis

After data cleaning, frequencies were calculated to explore distribution of missed care, reasons for missed care, staff characteristics, work schedules, and staffing variables across the ten hospitals. For analysis of frequency, the missed care items were treated dichotomously. Elements of care were considered missed if occasionally, frequently, or always was reported.

In the bivariate and multivariate analyses, the dependent variable was the overall missed care score. The overall missed care score is the average amount of missed care identified for each of the elements of nursing care for each participant. We then assessed if the responses from nursing personnel were clustered by nursing unit. Intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC) obtained by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) confirmed the correlation of each unit member's response to the group, with ICC values ranging from 0.05 to 0.30. Responses to missed care were significantly similar within nursing units (F[109, 3959] = 10.0, p < 0.001, ICC = 0.20). Based on these ICCs, all regression models used the robust cluster methods to account for clustering of responses in nursing units. Linear regression was used to identify significant independent variables (e.g., unit staff characteristics, work schedule, staffing) associated with missed care. To achieve a parsimonious model, a final multivariate analysis using robust cluster estimation procedures included independent variables previously significant at p < 0.05. Analyses were conducted using STATA 10.0 (College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Of the 4,086 respondents, 90% were female, and 51% held a baccalaureate degree or higher. The majority of respondents (77%) were registered nurses, and the remaining 23% were nursing assistants. Day shift was the most frequently reported work schedule (49%), followed by nights (35%), then evenings or rotating shifts (16%); most subjects (76%) worked 12 hour shifts. Work experience was widely distributed, with 32% reporting more than 10 years; 5% reporting fewer than 6 months, with the remainder evenly distributed across 6 months and 10 years of experience. One-third of subjects reported missing one shift in the last 3 months and 24 percent reported 2 or more shifts missed. The majority of subjects worked in medical-surgical units (52%), followed by intensive care (24%), intermediate care (19%), and rehabilitation (4%).

Amount and type of missed care

Table 1 shows the distribution of responses for how frequently each element of care was reported missed (always missed, frequently missed, occasionally missed, or rarely missed). Ambulation of patients three times per day (or as ordered) was the most frequently-reported element of missed care, with 32.7% of nurses reporting this action being frequently or always missed. Additional elements that were frequently or always missed included attendance at care conferences (31.8%), mouth care (25.5%). Conversely, performance of patient assessments (97.7%), glucose monitoring (97.6%) and vital signs (95.8%) were reported as only rarely or occasionally missed by almost all participants. The overall mean score of missed care was 1.56 (SD = 0.4).

Table 1.

Missed Nursing Care in 10 Hospitals: Frequency (Percent*) (n = 4086)

| Item of the MIS SCARE Survey | Rarely missed | Occasionally missed | Frequently missed | Always missed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Ambulation 3 times per day or as ordered | 906 (24.0) | 1639 (43.4) | 1153 (30.5) | 83 (2.2) |

| 2. Turning patient every 2 hours | 1647 (40.6) | 1794 (44.3) | 581 (14.3) | 31 (0.8) |

| 3. Feeding patient when the food is still warm | 1574 (42.4) | 1509 (40.7) | 595 (16.0) | 31 (0.8) |

| 4. Setting up meals for patients who feed themselves | 2382 (64.1) | 1017 (27.4) | 280 (7.5) | 37 (1.0) |

| 5. Medications administered within 30 minutes before or after scheduled time | 1507 (40.2) | 1581 (42.2) | 624 (16.6) | 36 (1.0) |

| 6. Vital signs assessed as ordered | 3024 (75.1) | 834 (20.7) | 145 (3.6) | 25 (0.6) |

| 7. Monitoring intake/output | 2020 (49.8) | 1315 (32.4) | 673 (16.6) | 45 (1.1) |

| 8. Full documentation of all necessary data | 1774 (44.4) | 1664 (41.6) | 524 (13.1) | 37 (0.9) |

| 9. Patient teaching about procedures, tests, and other diagnostic studies | 1682 (44.1) | 1565 (41.0) | 542 (14.2) | 29 (0.8) |

| 10. Emotional support to patient and/or family | 2305 (57.2) | 1249 (31.0) | 449 (11.1) | 24 (0.6) |

| 11. Patient bathing/skin care | 2183 (54.4) | 1513 (37.7) | 290 (7.2) | 24 (0.6) |

| 12. Mouth care | 1429 (35.5) | 1571 (39.0) | 949 (23.5) | 82 (2.0) |

| 13. Hand washing | 2922 (72.0) | 900 (22.2) | 207 (5.1) | 27 (0.7) |

| 14. Patient discharge planning and teaching | 2771 (67.8) | 715 (19.5) | 167 (4.5) | 18 (0.5) |

| 15. Bedside glucose monitoring as ordered | 3450 (86.2) | 455 (11.4) | 60 (1.5) | 36 (0.9) |

| 16. Patient assessments performed each shift | 3477 (90.1) | 292 (7.6) | 63 (1.6) | 27 (0.7) |

| 17. Focused reassessments according to patient condition | 2781 (73.2) | 863 (22.7) | 143 (3.8) | 14 (0.3) |

| 18. IV/central line site care and assessments according to hospital policy | 2434 (64.6) | 1086 (28.8) | 235 (6.2) | 13 (0.3) |

| 19. Response to call light is initiated within 5 minutes | 2018 (50.0) | 1467 (36.3) | 522 (12.9) | 30 (0.7) |

| 20. PRN medication requests acted on within 15 minutes | 2158 (57.1) | 1304 (34.5) | 296 (7.8) | 20 (0.5) |

| 21. Assess effectiveness of medications | 1868 (49.8) | 1520 (40.5) | 348 (9.3) | 13 (0.3) |

| 22. Attend interdisciplinary care conference whenever held | 1206 (34.4) | 1181 (33.7) | 879 (25.1) | 235 (6.7) |

| 23. Assist with toileting needs within 5 minutes of request | 2071 (51.4) | 1566 (38.8) | 371 (9.2) | 25 (0.6) |

| 24. Skin/wound care | 2626 (67.1) | 1151 (29.4) | 119 (3.0) | 18 (0.5) |

Note.

Valid percents presented in the table

MISSCARE, Missed Nursing Care; IV, intravenous; PRN, as needed

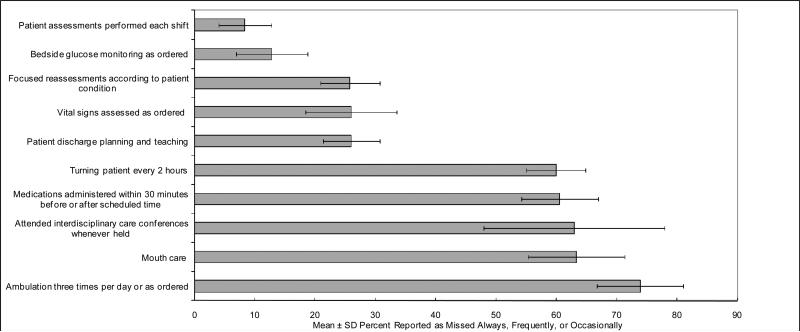

Figure 2 shows the elements of the least- and most- missed care across the ten hospitals. Although the percentages differed slightly, the least and the most-missed care items were similar across all ten hospitals. Bedside glucose monitoring and patient assessments were the least frequently reported as missed across all ten hospitals. Conversely, ambulation was among the top five elements of missed care reported across all ten hospitals, eight of which reported this as the most frequently missed element of care.

Figure 2. Elements of Care Most- and Least- Frequently Missed.

The solid bars represent the means across all ten hospitals, and the range-lines indicate the standard deviations.

Reasons for missed care

Reasons for missed care were also identified similarly in the ten hospitals (see Table 2). Inadequate labor resources was the most often cited reason for missed care (93.1% across the 10 hospitals), followed by material resources (89.6%) and communication (81.7%). Within the labor resources subscale, unexpected rise in patient volume and/or acuity was consistently identified as the top reason for missed care (94.9% for all respondents), with a range in frequency between 87.4% to 98.3% across hospitals. The most common item reported in the material resources subscale was the lack of availability of medications when needed (94.6% overall, range across hospitals 88.6% to 97.8%). Communication items were less similar across hospitals, however the most frequently reported item in this scale across hospitals was unbalanced patient assignments (91.0% overall, range across hospitals 82.2% to 95.4%).

Table 2.

Reasons for Missed Nursing Care across 10 Hospitals

| H1 (n=168) | H2 (n=46) | H3 (n=726) | H4 (n=469) | H5 (n=212) | H6 (n=198) | H7 (n=893) | H8 (n=198) | H9 (n=422) | H10 (n=754) | Total (n=4086) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

|||||||||||

| Bed size | 347 | 60 | 760 | 317 | 304 | 411 | 880 | 433 | 479 | 913 | |

| |

|||||||||||

| Participating unit # |

5 | 2 | 15 | 11 | 6 | 8 | 22 | 9 | 14 | 18 | |

| Item | |||||||||||

| | |||||||||||

| Labor Resources - Overall | 92.4% | 95.6% | 87.0% | 92.4% | 91.7% | 93.7% | 95.8% | 93.6% | 96.3% | 94.2% | 93.1% |

| | |||||||||||

| 1. Inadequate number of staff | 94.6% | 95.6% | 84.3% | 88.2% | 93.6% | 90.8% | 93.2% | 92.8% | 95.1% | 92.6% | 91.1% |

| | |||||||||||

| 2. Urgent patient situations (e.g. a patient's condition worsening) | 92.1% | 95.6% | 87.5% | 92.1% | 90.6% | 91.3% | 95.5% | 93.3% | 94.4% | 92.8% | 92.4% |

| | |||||||||||

| 3. Unexpected rise in patient volume and/or acuity on the unit | 92.7% | 97.7% | 87.4% | 95.2% | 96.0% | 97.4% | 97.6% | 95.2% | 98.3% | 96.1% | 94.9% |

| | |||||||||||

| 4. Inadequate number of assistive personnel (e.g. nursing assistants, techs, unit secretaries etc.) | 96.4% | 93.3% | 87.2% | 93.4% | 89.6% | 92.8% | 96.8% | 95.3% | 97.4% | 96.2% | 94.0% |

| | |||||||||||

| 17. Heavy admission and discharge activity | 86.1% | 95.6% | 88.5% | 93.0% | 88.8% | 96.2% | 96.1% | 91.2% | 96.4% | 93.1% | 92.9% |

| | |||||||||||

| Material Resources - Overall | 83.9% | 91.0% | 88.1% | 86.3% | 87.9% | 90.0% | 91.4% | 93.7% | 93.4% | 89.1% | 89.6% |

| | |||||||||||

| 6. Medications were not available when needed | 88.6% | 95.2% | 93.2% | 95.4% | 89.8% | 96.4% | 95.6% | 95.2% | 97.8% | 94.2% | 94.6% |

| | |||||||||||

| 9. Supplies/equipment not available when needed | 85.2% | 91.1% | 87.6% | 86.2% | 89.2% | 89.7% | 92.5% | 94.8% | 93.4% | 89.4% | 89.9% |

| | |||||||||||

| 10. Supplies/equipment not functioning properly when needed | 78.0% | 86.7% | 83.6% | 77.3% | 84.7% | 84.7% | 86.2% | 91.2% | 89.2% | 83.8% | 84.4% |

| | |||||||||||

| Communication/Teamwork - Overall | 79.2% | 75.2% | 80.2% | 79.1% | 80.0% | 83.0% | 83.5% | 78.3% | 84.4% | 83.1% | 81.7% |

| | |||||||||||

| 5. Unbalanced patient assignments | 91.6% | 82.2% | 87.7% | 89.1% | 88.7% | 91.2% | 94.2% | 85.5% | 95.4% | 91.7% | 91.0% |

| | |||||||||||

| 7. Inadequate hand-off from previous shift or sending unit | 84.6% | 84.1% | 86.1% | 88.2% | 87.1% | 89.8% | 88.8% | 84.0% | 90.0% | 89.3% | 88.0% |

| | |||||||||||

| 8. Other departments did not provide the care needed (e.g. physical therapy did not ambulate) | 73.9% | 77.8% | 84.4% | 82.5% | 88.3% | 84.9% | 87.7% | 85.3% | 86.0% | 82.8% | 84.5% |

| | |||||||||||

| 11. Lack of back up support from team members | 77.0% | 80.0% | 78.4% | 78.0% | 80.5% | 81.1% | 79.5% | 79.5% | 85.0% | 80.2% | 79.9% |

| | |||||||||||

| 12. Tension or communication breakdowns with other ancillary/support departments | 80.1% | 80.0% | 78.9% | 73.7% | 76.0% | 83.4% | 80.2% | 76.6% | 81.9% | 84.5% | 79.9% |

| | |||||||||||

| 13. Tension or communication breakdowns within the nursing team | 78.5% | 72.7% | 76.1% | 72.3% | 71.7% | 74.0% | 75.2% | 67.7% | 77.8% | 78.3% | 75.4% |

| | |||||||||||

| 14. Tension or communication breakdowns with the medical staff | 80.1% | 84.1% | 78.4% | 77.6% | 80.7% | 78.6% | 83.6% | 76.6% | 84.3% | 86.1% | 81.7% |

| | |||||||||||

| 15. Nursing assistant did not communicate that care was not done | 85.5% | 58.1% | 83.0% | 83.2% | 81.8% | 91.9% | 89.5% | 79.1% | 86.7% | 85.1% | 85.2% |

| | |||||||||||

| 16. Caregiver off unit or unavailable | 61.7% | 58.1% | 69.1% | 67.3% | 65.0% | 72.3% | 73.2% | 70.8% | 72.3% | 69.6% | 69.8% |

Missed nursing care by unit and staff characteristics

Using the overall sample (n = 4,086), a series of bivariate regression analyses using robust cluster estimation were conducted to find significant variations reported in missed care by unit staff characteristics, work schedules and perceived staffing adequacy. Eight variables were significantly associated with missed care: gender, age, job title, shift worked, years of experience, absenteeism, perceived adequacy of staffing, and number of patients they cared for. When nursing staff members were female (B = 0.84, robust S.E. = 0.02, p < 0.001), older (B = 0.03, robust S.E. = 0.01, p < 0.001), RNs (versus NAs) (B = 0.19, robust S.E. = 0.03, p < 0.001), working on a day shift (compared to those on night shifts, B = 0.05, robust S.E. = 0.02, p < 0.05), or experienced more (B = 0.04, robust S.E. = 0.01, p < 0.001), they reported more missed care. Nursing staff who missed more shifts in the past 3 months (compared to those who did not miss any shifts, B = 0.08, robust S.E. = 0.02, p < 0.001), perceived their staffing less adequate (B = 0.11, robust S.E. = 0.01, p < 0.001), or cared for more patients in the previous shift (B = 0.01, robust S.E. = 0.00, p < 0.05), reported significantly more missed care. Education level, weekly work hours, and type of unit were not significantly associated with missed care. Significant independent variables were then entered into the following multivariate analysis to determine the significant predictors of missed care.

Predictors of missed nursing care

A multiple regression model that includes variables significant from the bivariate analyses is shown in Table 3. The model significantly predicted the missed care score (R2=0.16, F[19, 109] = 28.0, p < 0.001). NAs (versus RNs) and staff with fewer years of experience reported significantly less missed care (p < 0.001). Night shift workers reported less missed care than day shift workers (p < 0.01). Nursing staff who missed 2 or more shifts in the past 3 months reported missed care more than those who did not miss any shifts (p < 0.01). Those who cared for more patients in the previous shift reported more missed care (p <0.001), while nursing staff who perceived their staffing as adequate more often reported less missed care (p < 0.001). Gender and age were not significantly associated with missed care.

Table 3.

Summary of Multiple Regression for Missed Nursing Care (n = 4086)

| Independent Variable | B | Robust SE | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 1.780 | .048 | 37.46 | .000 |

| Gender (Male=1, Female=0) | -.024 | .019 | -1.27 | .206 |

| Age | -.013 | .007 | -.1.89 | .061 |

| Job title (NA=1, RN=0) | -.284 | .037 | -7.67 | .000 |

| Shift worked: | .008 | |||

| Day (Reference) | ||||

| Night | -.052 | .016 | -3.13 | .002 |

| Other | -.028 | .018 | -1.57 | .119 |

| Years of experience in the role | .039 | .006 | 6.33 | .000 |

| Absenteeism: | .011 | |||

| One shift missed (reference: no shifts missed in past three months) | .010 | .014 | .72 | .471 |

| Two or more shifts missed | .049 | .016 | 2.98 | .004 |

| Perceived level of adequate staffing | -.104 | .009 | -11.13 | .000 |

| Number of patients cared for | .015 | .003 | 4.69 | .000 |

Note. R2 = .155, p < .000, F(19, 109) = 27.97 Analysis included a dummy variable for study hospitals to control for hospital effects (output suppressed).

DISCUSSION

This paper examined the relationship between levels and types of missed nursing care and reasons for missed care across 10 acute care hospitals. The trends in frequency and types of missed care were similar across these hospitals. Overall, ambulation, mouth care, care conference participation, medications on time, and patient turning were the top five missed care elements, while shift assessments, vital signs, discharge planning and teaching, glucose monitoring, and vital signs were the five least missed elements of care. From the clinical perspective, the least frequently reported elements of missed care from this study are obvious to others when missed and are routinely audited by nursing units. Conversely, ambulation of patients is not routinely recorded in nursing documentation, and there is less opportunity for others to perceive this care as missed. Also, patient ambulation and turning, for example, are often time-consuming (and thus placed lower on the priority list) and may require assistance from other providers (who may not be available). It is possible that these elements of care are not perceived as important by nursing staff, despite their strong correlation with patient outcomes. Increased attention to these elements, including a refocus of existing documentation systems, may be warranted.

The reasons for missed care are similar across hospitals, with labor resources most frequent, followed by material resources and communication, respectively. Taken together, these findings suggest that strategies to improve teamwork, communication, excessive workloads, poor personnel deployment, and flows in patient acuity and volume would create the conditions necessary to minimize the likelihood of missed nursing care.

Findings from this study reveal significant correlates of missed care, thus supporting the Missed Nursing Care Model (Figure 1). NAs report less missed care than RNs. This may reflect the broader scope of responsibilities conferred to RNs rather than NAs or power differences between RNs and NAs. Higher rates of missed care reported by day shift workers may suggest an imbalance in responsibilities for nursing personnel in a 24-hour period. Staff members who are absent more often report missed care, suggesting that these individuals may not have a strong connection to the nursing unit and the goals of care. Our finding of a relationship between staffing and missed care may partly explain the research findings of other researchers that link nurse staffing to patient morbidity and mortality.31

STUDY LIMITATIONS

There are several study limitations. Study data were collected from self-administered responses of nursing staff on the MISSCARE Survey as opposed to patient records. Direct observation, and/or chart review would provide additional measures of external validity. However, chart review may not be accurate in that nursing care is not consistently recorded. Direct observation may augment our approach, but raise the risk of observer bias. The multi-site nature of our design mitigates this limitation, as our findings show a level of consistency across study hospitals. Although focus groups and individual interviews with nursing staff were conducted to develop a list of all possible reasons for missing nursing care, it is not absolutely certain that all possible explanatory variables are included in our survey. Future studies could measure characteristics of health systems, patient contributing factors, and characteristics of other professionals. Despite these limitations, the results of these studies contribute evidence that an improvement in the quality of nursing care in acute care hospitals is needed and is of the highest priority.

IMPLICATIONS

From a quality of care perspective, reducing the likelihood of missed nursing care requires attention to several aspects of the care delivery system. The elements of missed nursing care and the reasons for this care were common across sites, suggesting that improvement is possible with attention to these specific aspects, such as managing personnel, admissions, and supplies more proactively. As missed nursing care has not yet been studied extensively, we recommend that open dialogue on this topic should be supported by management. The patient safety movement has benefited from open disclosure of systemic problems in care, media pressure, and expert panels in clinician groups.32 Increased discussion in a non-punitive context will highlight the size and scope of the problem, the determinants of missed care, and the strategies for improvement.

Increased measurement of this phenomenon would increase our understanding of its relationship to quality of patient care. One management intervention would entail administering the MISSCARE survey to nursing staff in a non-punitive environment. Staff could review results and use existing quality improvement programs (i.e., Plan-Do-Check-Act) to remedy the issues uncovered. Further research that correlates missed care with clinical outcomes is a needed step in assessing the priority of the corrective action needed. Once a clearer pattern of these relationships emerge in clinical areas, an important next step is to improve these processes of care across hospitals and health care systems.

In summary, our findings suggest that missed nursing care is reported similarly across acute care hospitals, and the reasons for missed nursing care are also shared across institutions. Strategies to ameliorate missed care should take these stated reasons to account, as hospitals continue to reduce complications and improve patient outcomes.

Acknowledgements

We thank the anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful suggestions. This research was supported by a research grant from the Blue Cross Blue Shield Foundation of Michigan. Dr. Friese was supported by a Pathway to Independence Award (R00 NR 10750) from the National Institute of Nursing Research.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors attest there are no conflicts of interest with the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Beatrice J. Kalisch, University of Michigan, School of Nursing Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Dana Tschannen, University of Michigan, School of Nursing Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Hyunhwa Lee, University of Michigan School of Nursing Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Christopher R. Friese, School of Nursing Ann Arbor, Michigan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Institute of Medicine (IOM) To err is human: Building a safer health system. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine (IOM) Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Federal Register [May 22, 2010];Medicare program; Hospital inpatient prospective payment systems for acute care hospitals and fiscal year 2010 rates and to the long-term care hospital prospective payment system and rate year 2010 rates: Final fiscal year 2010 wage indices and payment rates implementing the affordable care act. Available at: http://www.federalregister.gov/OFRUpload/OFRData/2010-12563_PI.pdf.

- 4.Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) [January 17, 2008];AHRQ PSNet Patient Safety Network: Glossary. Available at: http://psnet.ahrq.gov/glossary.aspx.

- 5.Kalisch BJ, Landstrom G, Williams RA. Missed nursing care: Errors of omission. Nurs Outlook. 2009;57(1):3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalisch BJ, Landstrom G, Hinshaw AS. Missed nursing care: A concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(7):1509–1517. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Callen BL, Mahoney JE, Grieves CB, Wells TJ, Enloe M. Frequency of hallway ambulation by hospitalized older adults on medical units of an academic hospital. Geriatr Nurs. 2004 Jul-Aug;25(4):212–217. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2004.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kamel H, Iqbal M, Mogallapu R, Maas D, Hoffmann R. Time to ambulation after hip fracture surgery: relation to hospitalization outcomes. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58(11):1042–1045. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.11.m1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mundy LM, Leet TL, Darst K, Schnitzler MA, Dunagan WC. Early mobilization of patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2003 Sep;124(3):883–889. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.3.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Munin MC, Rudy TE, Glynn NW, Crossett LS, Rubash HE. Early inpatient rehabilitation after elective hip and knee arthroplasty. JAMA. 1998 Mar 18;279(11):847–852. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.11.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Price P, Fowlow B. Research-based practice: early ambulation for PTCA patients. Can J Cardiovasc Nurs. 1994;5(1):23–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whitney JD, Parkman S. The effect of early postoperative physical activity on tissue oxygen and wound healing. Biol Res Nurs. 2004;6(2):79–89. doi: 10.1177/1099800404268939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yohannes AM, Connolly MJ. Early mobilization with walking aids following hospital admission with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clin Rehabil. 2003 Aug;17(5):465–471. doi: 10.1191/0269215503cr637oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rasmussen HH, Kondrup J, Staun M, Ladefoged K, Kristensen H, Wengler A. Prevalence of patients at nutritional risk in Danish hospitals. Clin Nutr. 2004 Oct;23(5):1009–1015. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anselmi ML, Peduzzi M, Dos Santos CB. Errors in the administration of intravenous medication in Brazilian hospitals. J Clin Nurs. 2007 Oct;16(10):1839–1847. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.01834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holley JL. A descriptive report of errors and adverse events in chronic hemodialysis units. Nephrol News Issues. 2006 Nov;20(12):57–58. 60–51. 63 passim. 2006. 63 passim. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rinke ML, Shore AD, Morlock L, Hicks RW, Miller MR. Characteristics of pediatric chemotherapy medication errors in a national error reporting database. Cancer. 2007 Jul 1;110(1):186–195. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sochalski J. Is more better?: the relationship between nurse staffing and the quality of nursing care in hospitals. Med Care. 2004 Feb;42(2 Suppl):II67–73. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000109127.76128.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schubert M, Glass TR, Clarke SP, et al. Rationing of nursing care and its relationship to patient outcomes: the Swiss extension of the International Hospital Outcomes Study. Int J Qual Health Care. 2008;20(4):227–237. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzn017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalisch BJ. Missed nursing care: a qualitative study. J Nurs Care Qual. 2006 Oct-Dec;21(4):306–313. doi: 10.1097/00001786-200610000-00006. quiz 314-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalisch BJ, Williams RA. Development and psychometric testing of a tool to measure missed nursing care. J Nurs Adm. 2009;39(5):211–219. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e3181a23cf5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Cheung RB, Sloane DM, Silber JH. Educational levels of hospital nurses and surgical patient mortality. JAMA. 2003;290:1617–23. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.12.1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Needleman J, Buerhaus P, Mattke S, Stewart M, Zelevinsky K. Nurse-staffing levels and the quality of care in hospitals. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1715–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cimiotti JP, Haas J, Saiman L, Larson EL. Impact of staffing on bloodstream infections in the neonatal intensive care unit. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:832–6. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.8.832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hugonnet S, Chevrolet J-C, Pittet D. The effect of workload on infection risk in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:76–81. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000251125.08629.3F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Unruh L. Licensed nurse staffing and adverse events in hospitals. Med Care. 2003;41:142–52. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200301000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dunton N, Gajewski B, Taunton RL, Moore J. Nurse staffing and patient falls on acute care hospital units. Nurs Outlook. 2004;52:53–9. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Unruh L, Joseph L, Strickland M. Nurse absenteeism and workload: negative effect on restraint use, incident reports and mortality. J Adv Nurs. 2007;60(6):673–681. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04459.x. (2007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scott LD, Rogers AE, Hwang WT, Zhang Y. Effects of critical care nurses’ work hours on vigilance and patients’ safety. Am J Crit Care. 2006;15(1):30–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hutto CB, Davis LL. 12-hour shifts: panacea or problem? Nurs Manage. 1989;20(8) doi: 10.1097/00006247-198908000-00019. 56A, 56D, 56F passim. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kane RL, Shamliyan TA, Mueller C, Duval S, Wilt TJ. The association of registered nurse staffing levels and patient outcomes: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Med Care. 2007;45(12):1195–204. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181468ca3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reason J. Managing the risks of organizational accidents. Ashgate; Hants, England: 1997. [Google Scholar]