Abstract

In this article we analyze qualitative data from a multiple methods, longitudinal study drawn from 15-year follow-up interviews with a subsample of 82 individuals arrested for driving while intoxicated in a southwestern state (1989–1995). We explore reactions to the arrest and court-mandated sanctions, including legal punishments, mandated interventions, and/or participation in programs aimed at reducing recidivism. Key findings include experiencing certain negative emotional reactions to the arrest, reactions to being jailed, experiencing other court-related sanctions as deterring driving while intoxicated behavior, and generally negative opinions regarding court-mandated interventions. We discuss interviewees’ complex perspectives on treatment and program participation and their effects on lessening recidivism, and we offer suggestions for reducing recidivism based on our findings.

Keywords: Alcohol/alcoholism, addiction/substance use, comparative analysis, intervention programs, risk, behaviors

Although repeat offenders are in the minority of all people convicted of driving while impaired or “intoxicated” (DWI), they are a particularly high-risk group. They are more likely than non-DWI drivers to involve themselves in fatal motor vehicle crashes or hit-and-run collisions with pedestrian fatalities, and to have high blood alcohol concentrations (0.15% and above) when driving (Solnick & Hemenway, 1994; Beirness, Simpson, & Mayhew, 1991; Fell, 1992; Fell, 1995). They are also more likely than first offenders to refuse the breath alcohol test and to fail to comply with court-mandated sanctions (Collier & Longest, 1996; Fredlund, 1991; Elliott & Morse, 1993).

An important target for remedial intervention is the repeat DWI offender. Consequently, they have been the focus of a variety of deterrence strategies (Lapham, Skipper, & Simpson, 1997; Peck & Peck, 1994; McMillen, Pang, Wells-Parker & Anderson, 1992; Wieczorek, Miller, & Nochajski, 1992; Gijsbers, Raymond, & Whelan, 1991; Nichols, 1990; Transportation Research Board/National Research Council, 1995; Perrine, Peck, & Fell, 1989; Hedlund & Fell, 1995). Gibbs (1968) defined general deterrence as the effect of law enforcement on the behaviors of the general driving public (i.e., those who have engaged in illegal behavior and those who have not, whether or not they have been punished for a crime). Specific deterrence refers to the effect of punishment on identified offenders (Ross & Nichols, 1990). Deterrence theory assumes that certain, swift, and severe punishment increases a person’s perception that he or she will be punished if he or she commits a crime, and this discourages offenders from repeating the illegal behavior (Taxman & Piquero, 1998). Deterrence, as it pertains to convicted DWI offenders, involves a variety of punishments, including jail time, driver’s license restrictions, fines, confiscating or immobilizing the offender’s vehicle, and community service. It also can involve other more “social” punishments, such as printing names and photos of convicted DWI offenders in the newspaper, special license plates, and other penalties. Here we focus on the specific deterrence of impaired driving by drivers who have been arrested and convicted of a first DWI offense.

Sanctions most commonly applied are those that prohibit driving or reduce the opportunity to drive after drinking. These include jail time, house arrest, driver’s license revocation or suspension, and immobilization or removal of the vehicle. Courts use jail or prison time as a punishment for and deterrent to impaired driving (Houston & Richardson, 2004). License restrictions reduce alcohol-related crashes, but the propensity of offenders to drive without a valid license hampers the effectiveness of this sanction (Voas, Tippetts, & McKnight, 2010; Voas, Romano, & Peck, 2006). Even when given the opportunity to reinstate their licenses, many offenders do not follow through with the required procedures (Brown et al., 2010; Voas et al., 2010).

Some states mandate judges to require all convicted offenders to install an ignition interlock (interlock) on their vehicles (DWI laws, 2010). An interlock is an alcohol sensor connected to the engine’s ignition system that does not allow the vehicle to start unless a breath test result is below a set level. In the state in which we conducted the study, the level is defined at .025%, less than one-third of the state’s .08% maximum legal blood alcohol concentration. Disadvantages of such mandates include reluctance of some judges to impose this sanction and the failure of a majority of offenders to have the required interlock device installed (Roth, Marques, & Voas, 2009; Voas, Fell, McKnight, & Sweedler, 2004).

In addition to court-ordered sanctions, deterrence strategies typically are combined with court-mandated treatment that requires offenders to complete an approved therapeutic regimen to avoid additional legal sanctions (Dill & Wells-Parker, 2006). Impaired drivers make up the vast majority of criminal justice system referrals to the public treatment system (i.e., community-based programs not located in jails or prisons). Although accurate statistics on the total number of criminal justice referrals to these programs are unavailable, impaired-driving offenders accounted for an estimated 36% of referrals in 2002 (Dill & Wells-Parker, 2006). Using data provided by treatment facilities that report to state administrative data systems, analysts found that, in 2002, criminal justice/DWI referrals accounted for 40% of admissions for treatment of alcoholism-only, and for 34% of admissions for treatment of abuse of alcohol and at least one other drug (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2004).

The purpose of this study was to determine the extent to which offenders’ perceptions of the legal consequences of being arrested and convicted of DWI differentiate those who did and did not report driving when they thought they were over the blood alcohol limit (DOL) in the 90-day period preceding their 15-year follow-up interview. Data were derived from a mixed-methods study of 716 DWI offenders who were tracked for 15 years after a first DWI conviction (Lapham & Skipper, 2011). In this article, we describe results from qualitative interviews conducted with 82 of these offenders. We present data on how convicted DWI offenders perceived their experiences with the criminal justice system, and we discuss whether these perceptions have implications for preventing recidivism in this high-risk population. In particular, we include descriptions of the participants’ views regarding the arrest experience itself, the sanctions they received, and their perceptions of how these affected DOL behavior. We hope that this information will lead to the development of more effective remediation strategies.

Method

Study Population

We recruited participants from subjects in a longitudinal study of offenders referred to a comprehensive screening program for individuals convicted of a first DWI offense (Lapham et al., 1995). The screening program was part of an exclusive contract with a metropolitan court to provide alcohol and drug screening services for all convicted first offenders; it existed from April 1989 to October 1995. The longitudinal study staff interviewed 1,396 offenders five years after their referral for screening, and 716 were interviewed at the 15-year study’s endpoint (Lapham & Skipper, 2011). We conducted structured and semi-structured interviews with 82 of these 716 participants. We invited participants who completed the structured interview to participate in the qualitative study, based on stratified sampling designed to select approximately equal numbers of participants who reported recently driving over the alcohol limit and those who had not. Our final sample included 37 individuals who had driven when they believed their blood alcohol levels exceeded the alcohol limit of .08% in the 90 days before either the structured or the qualitative interview (recent DOL) and 45 individuals who reported no episodes of DOL in the 90 days before either interview (no recent DOL). Participants were paid $35 to complete the one-hour interview. The Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation Institutional Review Board approved the protocol.

Qualitative Interview

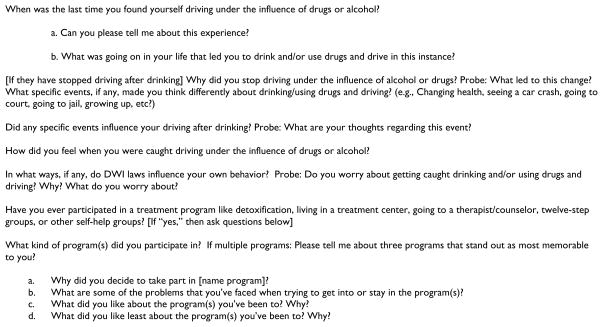

Our semi-structured interview guide consisted of open-ended questions designed to assess how various life experiences influenced the participants’ impaired-driving behaviors (see Figure 1). We recorded and transcribed these interviews. To characterize the population and obtain responses to several closed-ended questions, we imported data from the quantitative interview regarding demographic descriptors, alcohol use disorders, and perspectives toward driving after drinking into NVivo 8 (QSR International, 2008), a software program that facilitates the analysis of qualitative data, to allow comparisons between participants’ recent DOL behavior and their perspectives on sanctions.

Figure 1.

Open-ended interview questions from survey instrument

Data Analysis

We first coded transcripts by question and developed a descriptive coding scheme based on the specific questions and domains of the interview protocols. Then we categorized responses according to emerging themes using a grounded theory approach based on Strauss’ model (Duchscher & Morgan, 2004). Two researchers read transcripts and coded for particularly salient themes to create an initial structure for coding. We identified pattern codes, allowing indexing of data that illustrated emergent themes. A third coder then used a systematic line-by-line coding system to discover any other emerging themes and significant issues. We then recoded each transcript for the additional themes and issues.

Results

Results are presented in the following order: (a) participant characteristics; (b) reactions to a DWI arrest; (c) crash involvement; (d) perceptions of sanctions received, including jail, costs of the DWI in money and time, and sanctions on driving; and (e) thoughts on the benefits or lack of benefits of court-mandated completed treatment or other interventions. In each category, we have identified emerging themes that differentiated participants who reported recent DOL and those who reported no recent DOL.

Participant Characteristics

Demographic characteristics did not differ according to whether a participant reported recent DOL or not, except that those age 50 or older were more likely to have no recent DOL. Twenty of 26 participants age 50 or older (77%) had no recent DOL, whereas 23 of 56 younger participants (41%) reported no recent DOL. A little more than half the participants were women (n = 47; 57%); 45% were aged 40–49, with 23% under 40, and 32% were older than 49. Only 18% had fewer than 12 years of education, 28% had 12 years, and 54% had more than 12 years. Twenty-six percent had never been married, 43% were married or living as married, and 31% were divorced. The ethnic mix was 41% Hispanic, 29% non-Hispanic White, and 20% Native American, with the remainder from other racial/ethnic populations. Almost all (95%) were born in the United States. We used the Comprehensive International Diagnostic Interview of the World Health Organization, developed for use by trained lay interviewers (Robins et al., 1988), to evaluate relative dependence on alcohol and/or other substances. Twenty-nine participants (35%) reported no lifetime alcohol dependence, and 53 participants (65%) reported lifetime alcohol dependence.

Reactions to the DWI Arrest

For many offenders, events associated with the arrest led to an increased awareness of and change in perspectives about DOL. Key events included the actual arrest and the experience in jail. Seven people named the arrest and surrounding events as a “wake-up call,” meaning that it radically changed their perspective on their DOL behavior. Three others described the experience as such, but did not specifically use that term. Of the 10, nine reported no recent DOL. Some also viewed having caused a crash as a specific type of “wake-up call.”

More common than talking about being “awakened” was a realization of potential consequences of their DWIs, e.g., personal and/or family problems or the possibility of hurting others. Although it was sometimes reported that the DWI arrest itself did not have much impact, it appeared to be one of several factors that, in combination, eventually led to a change in perspective about DOL. Some participants needed a combination of negative consequences to alter the behavior, such as the one who said this:

I know when to say when; I restrict my driving as much as I can, in fact, I think drastically. Yeah. I’ll buy the booze, I’ll take it home and drink it; and don’t drive unless I have to. But, [the DWI conviction] is costly, time-consuming, it just turns your world around. . . . It’s not a good feeling. Your car gets impounded, you already know what goes with that: money, fines, and all of the above.

It is not surprising that nearly all respondents reported negative reactions to their DWI arrest. Descriptions of the emotional responses to the arrest varied; these were reported by 69 respondents. We classified them into seven major categories: self-deprecation (i.e., shame, guilt, anger at self, remorse, embarrassment, humiliation, degradation, feeling stupid; n=45), fear (n = 17), horror (n = 13), feeling responsible (n = 10), depression (n = 14), relief (n = 5), and surprise (n = 2). Compared with recent offenders, the participants with no recent DOL were far more likely to report feeling shamed or stupid, being afraid or anxious, and/or realizing their own responsibility for the arrest. Of those who brought up their emotional reactions to the arrest during the interview, most individuals focused on a limited number of emotional responses: 27 interviewees (39%) spoke of feeling only one emotional response; 20 people (29%) reported two responses; 16 individuals (23%) three; and six (9%) described four to six different emotional responses. Those who reported a recent DOL tended to describe fewer emotional responses than those who had not. For example, 50% of them reported only one emotional response, whereas about one third of those with no recent DOL reported only one. In addition, 12% of those who reported no recent DOL described four or more emotional responses; only 3% of those with a recent DOL mentioned four or more. Over half of the Native American interviewees described only one emotional response, and none described more than three. Hispanic and White non-Hispanic interviewees reported similar numbers of emotional responses to their DWI arrest. All five people who reported a sense of relief when arrested reported no recent DOL. One person explained it like this:

There’s always a little bit of excitement in doing the wrong thing, on the one hand. On the other hand, when you have a problem that you can’t control yourself, it’s kind of a relief to have somebody stop you. It’s like being the wayward child and having a strong parent stop you; it’s a relief.

Those with no recent DOL reported more emotional responses of every type, with the exception of depression, than did recent offenders. However, some with recent DOL events did report powerful emotional responses. As one repeater noted, “But that was so vivid and I was drunk, too, but it just was so horrendous. I cried all the way down [to the police station]. I couldn’t stop crying. . . .You would have thought that would have snapped me out of it.”

Crash Involvement

A somewhat higher percentage of those involved in a crash (14 individuals, or 17%) reported no recent DOL compared to respondents who did not cause a crash (n = 9, 11%). In the larger sample, however, there were no statistical associations between having caused a crash and reporting no recent DOL. Of 705 subjects interviewed at the 15-year follow-up whose driving records were available in the state’s motor vehicles files, 24% of the 74 participants who reported DOL had been involved in a crash in the past 15 years, whereas 29% of the 631 who reported no DOL had been involved in a crash (F-statistic, p = 0.73).

Perceptions Regarding Sanctions and Court Mandates

Participants reported a wide variety of court-related and other consequences of the DOL (see Table 1). Financial losses, court-mandated treatment, fines, and jail time were the most commonly reported DWI-related consequences. Financial loss was reported by 60 (73%) of the subjects. Examining Table 1, a trend is evident in that those who reported no recent DOL reported having experienced a higher number of consequences in almost all categories than participants with recent DOL behavior.

Table 1.

Sanctions Reported as a Consequence of a DWI Arrest and Conviction

| Type of Sanction or Other Consequence | Total N |

Did Not Drive over the Limit Within90 Days Prior to Interview N (% of those reporting sanction) |

Drove Over the Limit Within 90 Days Prior to Interview N (% of those reporting sanction) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Financial loss | 60 | 32 (53) | 28 (47) |

| Court-mandated interventions* | 49 | 25 (51) | 24 (49) |

| Jail | 27 | 20 (74) | 7 (26) |

| Fines | 43 | 20 (47) | 23 (53) |

| Property loss or loss of value (includes vehicle crash) | 29 | 19 (66) | 10 (34) |

| Time lost | 23 | 13 (57) | 10 (43) |

| Lost or gave up vehicle | 15 | 11 (73) | 4 (27) |

| Lost license | 13 | 9 (69) | 4 (31) |

| Community service | 10 | 7 (70) | 3 (30) |

| Probation | 10 | 3 (30) | 7 (70) |

| Cost of mandated treatment | 10 | 4 (40) | 6 (60) |

| DWI education | 8 | 4 (50) | 4 (50) |

| Other or unspecified | 8 | 7 (88) | 1 (12) |

| Name in newspaper | 7 | 4 (57) | 3 (43) |

| Court or lawyer costs | 5 | 3 (60) | 2 (40) |

| Interlock device in vehicle | 2 | 2 (100) | 0 |

| Increased cost of insurance | 1 | 1 (100) | 0 |

| Fatality | 1 | 1 (100) | 0 |

includes counseling, Alcoholics Anonymous, and victim impact panels

Time in Jail

Many individuals reported that their experience of being handcuffed and taken to jail was an especially memorable negative aspect of the DWI arrest experience. Interviewees reported that an experience of jail time deterred their potential future DOL. Far more participants without any recent DOL reported having gone to jail than recent offenders (see Table 1). In fact, only one individual did not seem disturbed by his time in jail. One woman with no recent DOL described the impact of her incarceration:

By the time they breathalyzed me, I was .10, the legal limit. I was drinking consistently at this party throughout the night, and the thought never occurred to me not to get in the car, and that I was gonna get [a DWI]. It never occurred to me because I had been doing it for so many years. And there was the police and it was the most embarrassing thing. My husband walked back to the party and told my friends and they all came when I’m sitting in the back of the police car. That was my last experience driving under the influence…. And then being taken to jail, put in the holding cell. . . . And staying huddled in my little corner. Little school teacher [me]. <laughs> I was way out of my element. So I don’t need to go through that again.

This participant’s emotional and richly detailed description of her jail experience is an example of the “lived experience” described by Stelter (2010) when he discusses experience-based narrative production. None of those who produced narratives of this type had recent DOL episodes. Others described their experience more succinctly, but still reflected a powerful memory of their lived experiences, as when another participant stated this:

I’ve been in jail and it’s bad. I don’t ever want to go back. I’ve done my community service, I paid my fines, and it helps; I mean it makes you stop and think about it next time ’cause you don’t want to go through that again. I know I don’t.

The experience of being in jail was powerful, even when the experience was brief (e.g., a few hours, as in the case of the school teacher quoted above). These responses seem to support the deterrent effects of jail time in reducing DOL. The jail “experience” that offenders reported in this study happened as part of the arrest, making this consequence swift and almost universally “severe.” Offenders who did not go to jail or who did not describe their experience in jail were more likely to be continued or recent offenders.

We tested the applicability of deterrence theory using structural equation modeling in the larger study population (Lapham & Todd, 2011). Our prospective analysis did not uncover strong associations between perceptions of high probability of enforcement and DWI behavior at the 15-year follow-up. However, results did suggest that punishment in the form of jail time might decrease the likelihood of DWI recidivism. We found a positive association between rates of DWI behavior at the initial interview and DWI at follow-up for those who experienced less jail time, but did not find this association for those reporting more jail time (Lapham & Todd, 2011). This finding is consistent with what participants reported regarding the lived deterrent effect of having been jailed.

In the present article, we discuss the experience in jail as a major deterrent, but jail stays were not long. Most offenders stayed in jail for a few hours, overnight, or until they could post bail. We do not know whether lengthier jail sentences for first-time offenders might bolster the deterrence effect, but studies have not borne this out. Research has not conclusively demonstrated the usefulness of jail time in preventing alcohol-related motor vehicle crashes beyond the temporary benefit of keeping offenders off the roads while they are jailed (Whetten-Goldstein, Sloan, Stout, & Liang, 2000). Longer jail sentences also could impart negative consequences on the offenders’ living situations and the probability of maintaining their jobs, as discussed earlier.

Costs of the DWI in Money and Time

The most commonly reported profoundly negative experience mentioned by participants was the financial cost of the DWI conviction, reported by 60 of the 82 participants (see Table 1). Fines were the most commonly described financial sanction/DWI-related cost. Other costs included attorney’s fees, costs from loss of or damage to property, and other financial consequences of a DWI arrest. However, nothing in these descriptions, besides the sheer number of consequences mentioned, distinguished those with recent DOL events. Individuals with no recent DOL nearly always indicated that the risk of future fines was a major consideration in their decisions related to DOL and their desire to stop. Recent offenders also complained about the fines they were required to pay. Those with no recent DOL enumerated more financial losses than those who reported current DOL. Another difference between the two groups is that those with no recent DOL were more likely to specifically compare spending the money on fines to how they might have spent it, had they not gotten a DWI (e.g., taking the family on an outing or saving the money). In contrast, those with recent DOL were likely to complain only about the cost or compare it to unrealistic possible uses.

Participants frequently described the loss of time when asked to discuss the legal consequences of their DWI arrest, typically as a form of opportunity cost. The cost of time spent in classes and other forms of treatment was the most common “loss” of time mentioned, particularly when the individual believed that she or he was deriving no benefit from the treatment. Community service was another court-mandated sanction that involved expending their time. However, few participants commented on the community service sanction. Participants were typically allowed to select the type of community service they performed. No one sentenced to community service performed tasks related to their DWI; all requirements lasted only for a short time (e.g., a few hours or weekends), and several considered the experience “enjoyable.” Two people specified that they worked in children’s daycare centers, and another picked up highway litter.

Sanctions on Driving

Thirteen participants of the 69 who described receiving at least one DWI-related court sanction reported that their driver’s license had been revoked (see Table 1); one other was driving under the influence of alcohol on a license revoked for other violations. Of these 14, one applied for and received a waiver allowing him to drive, six drove under the influence of alcohol using a revoked license, and two drove despite the revocation for unspecified reasons. Only one participant reported that the courts took away a vehicle; none reported short- or long-term “booting” (i.e., imposition of a rear-wheel lock that renders the car nondrivable). However, 15 individuals either lost their vehicles because of damage related to a DWI-related crash or voluntarily gave up their vehicles to keep themselves from driving while drunk. One recalled his experience:

When I first got out [of jail], I got an apartment. My counselor wanted to take me to get a car. I told him I didn’t want a car because that’s where I always get in trouble, because at night if I start drinking then I want to drive somewhere, because I’m alone. I would end up at a bar. So I thought if I didn’t have a car and I did start drinking, I couldn’t get a DWI. I didn’t know anybody, so I couldn’t borrow a car. I didn’t have one for a long time, almost 4 years before I got a car. I rode the bus.

Judges ordered only two participants to have an interlock installed in their vehicles. One person used the interlock to abstain from DOL, but he sold the car after a year for unrelated reasons. The other person had an interlock at the time of his interview, following his fourth DWI arrest three years before his interview. He observed this:

The only thing that’s had an influence on my drinking and driving is that little breathalyzer they put in my car two years ago…. [I have to have it in] sixteen years. Finally – a consequence. I love that thing.

He also described how he had managed to bypass the device and drive after drinking by blowing air from one of his tires into it. (Several participants who mentioned that the interlock device could be thwarted described this as a limitation of the interlock device in stopping DOL.) After confirming that he could succeed, he decided not to do it again; he said that he felt certain he would go to prison if rearrested for DOL. This participant believed that two factors caused him to stop DOL: First, he was forced to install an interlock device, and, second, he realized he would be sent to prison if he were rearrested.

Treatment and Intervention Programs

Individuals were court mandated to complete a variety of program types (see Table 1). Counseling or other treatment, Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) or other 12-step or peer-support programs, and Victim Impact Panels (VIP) were the most commonly mentioned programs. Those who sought help on their own most commonly reported going to 12-step meetings and/or counseling. Only two participants reported that a lack of insurance prevented them from getting counseling. One of these and an additional participant indicated that cost was a barrier to obtaining treatment, either directly or indirectly (e.g., the loss of ability to work and therefore to pay bills if the participant entered a residential treatment program).

No clear, consistent pattern emerged of the treatments or programs mandated for offenders, although more than half of them reported they received such services (see Table 1). Participants often could not clearly distinguish the types of services they received. Therefore, for this analysis we combined counseling, AA or other 12-step programs, and Victim Impact Panels into an “intervention” category. The court mandated 49 of the 59 people who reported having received such interventions; 21 interviewees reported seeking some type of help or counseling on their own, either in addition to or after mandated interventions (11) or without having been mandated at any time (10). Of those who were court-mandated, 25 had not recently driven over the limit, and 24 had.

Counseling

Participants’ views of and responses to interventions varied by the type of services received and by the reasons they gave for signing up for them. Individuals who were court-mandated to enroll reported more negative responses than did individuals who chose to participate on their own. Individuals were more likely to see the experience as beneficial or positive if the client-counselor pairing was a good match and/or they felt that the counseling addressed and helped resolve problems or issues in their lives. Individuals primarily focused negative comments about counseling on the client-counselor relationship. Their stated complaints included their belief that they did not “belong” in treatment or feeling that counselors belittled or ignored them, as described by one participant:

That was the first experience I’ve ever had with a counselor. He berated me and was antagonistic and kept confronting me. . . . I get pretty defensive right away and fought back and that was a bad experience. And he was a recovering alcoholic, and I think he was one of those people that saw me in him and wanted to just say the magic words and make me stop.

Overwhelmingly, those who disliked treatment also felt that they did not benefit from it. “Benefit” included stopping or decreasing DOL, learning strategies for doing so, acquiring useful information, and “turning my life around.” Everyone who believed they benefitted also said that they “liked” their treatment or program.

Counseling was the second most common sanction after mandatory AA or other 12-step programs to be described as “not beneficial.” Reported reasons for the failure of treatment varied. Four participants indicated that “real drunks never stop,” and five directly stated that their mandated treatment failed because they were “not ready” at the time (e.g., not ready to stop drinking, to address problems they were trying to escape by substance use, and/or to stop living a “partying” lifestyle). Ten interviewees said that people have to be “ready to quit” for help to be effective. An additional two individuals stated that if “the system” had imposed sanctions earlier, they might not have driven drunk as often. One reported that he has avoided punishment because he appears youthful and attractive. He believes that if he had experienced any negative consequence at all, it would have provided a “wake-up call.” Another participant wanted help, but did not know how to ask for it or where to go.

Court-mandated treatment did not appear to be related to recent DOL behavior. Ten individuals who did not feel as though they “belonged” in a treatment setting simply attended because of the court mandate. They typically reported that the treatment had little lasting effect. Failure to receive treatment did not predict whether or not interviewees had recently DOL: 11 people who reported no recent DOL said that they had not participated in any treatment or programs, as did 10 recent offenders.

About 50–70% of persons convicted of DWI have alcohol use disorders, indicating a need for alcohol treatment (Miller, Whitney, & Washousky, 1986; Lapham et al., 2001; Shaffer et al., 2007). Although data suggest that alcohol treatment is effective, more methodologically robust research is needed regarding DWI offenders, as well-controlled prospective studies with sufficient sample sizes have not supported the effectiveness of formalized alcohol treatment in this population (Wells-Parker, Bangert-Drowns, McMillen, & Williams, 1995). Although a combination of therapy and informational programming is useful in reducing recidivism of first-time offenders (Kernodle, Joyce, & Farmer, 1995), treatment programs have had limited success with repeat offenders. Success largely depends on offenders’ motivation to participate. Some offenders resist completing treatment because they do not believe they have a substance use problem, do not want to be labeled “alcoholic,” or are not willing or able to pay for services (Lapham, C’de Baca, Chang, Hunt & Berger, 2002). A meta-analysis of studies on the effectiveness of treatment with DWI offenders did not show a consistent pattern of positive results regarding reduced drinking or other nontraffic outcomes. It did show a small but significant effect in reducing DWI recidivism and alcohol-related crashes, in the range of 7–9% (Wells-Parker et al., 1995).

Conversely, several studies have demonstrated that nontreatment-seeking clients ordered into alcoholism treatment by the criminal justice system show reductions in alcohol use similar to that of clients who had entered treatment voluntarily (Hubbard, Craddock, & Anderson, 2002; Summers, 2002; Urbanoski, 2010). Perhaps the best outcomes might occur when offenders receive a combination of sanctions and treatment (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration & National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 1996). For example, a study of all drivers arrested for DWI over a two-year period in California indicates that, for single and multiple DWI convictions, the lowest recidivism rates are associated with a combination of license sanctions and alcoholism treatment (De Young, 1997).

Our study of the association of treatment with substance use disorder outcomes analyzed data from 583 subjects who completed the 15-year follow-up study and reported a substance use disorder with onset at or before the age at which they were screened for substance use disorders as part of their DWI sentence (Lapham & Skipper, 2010). We divided offenders presenting for screening into one of 4 groups: those who did not complete screening despite a court order to do so; those who completed screening and were not referred to treatment; those who completed screening, were referred to treatment, and completed it; and those who completed screening, were referred to treatment, but did not complete it. Then we examined their 15-year treatment utilization and substance use disorder outcomes. Univariate and multivariate statistics were used to determine predictors of long-term outcomes.

At follow-up, current substance use disorders were reported by 21% and DOL by 10%, of subjects. About 26% of study participants reported having received any substance abuse or mental health treatment services in the 10-year period before the last interview. Only 20% of all offenders reported that they had received at least one week of outpatient treatment services for mental health or substance abuse problems during the interval between screening and the five-year follow-up interview. Those offenders with higher levels of outpatient treatment, more detoxification services, emergency department visits, and lifetime 12-step meeting attendance were more likely than others to report a current substance use disorder (alcohol or drug abuse or dependence) at the 15-year follow-up, suggesting higher levels of problem severity and possibly a lack of efficacy in the treatment services received. These findings suggest, as observed by our study participants, that treatment programs might need to modify their approach when treating DWI offenders.

Alcoholics Anonymous and Other 12-Step Programs

The most commonly criticized court-mandated intervention by respondents in this study was Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and similar 12-step programs. They were least prone to being “liked” and/or considered beneficial, and interviewees had largely negative feelings about their mandates to attend AA. The most common complaints were that individuals did not feel as though they “belonged” there or voiced skepticism about the program itself. One participant put it this way:

I tried going to one of those a couple of times at lunch time and I just looked around and told myself, “These people are all just lying to each other and to themselves.” I guess I wasn’t ready, because I just didn’t believe them. I’d walk outside, and they’re all out there smoking and talking about where they’re going that weekend. And something told me, I just don’t believe it. So I didn’t go.

Objections were raised by another participant about calling oneself an “alcoholic”:

I don’t know if these people had problems but a lot of them say, “Hi, my name is <name> and I’m an alcoholic.” Why do they want to put a label on themselves? I don’t understand that. It doesn’t make sense.

Others, such as the following respondent, stated that the stories of attendees rang false and merely represented an attempt to linger in the past:

Either way’s not worth it. Go out and be an alcoholic and get drunk all the time. It’s not worth it, because look at the consequences. And then if you go to rehab where you become a . . . recovering alcoholic or whatever. That’s not worth it either, because then you gotta go, 12 years, 15 years they’ve been sober and they’re still going to those AA meetings, so if you’re not part of the solution, you’re part of the problem. And solution to me is not sitting in those 12-step meetings. . . . That’s not the solution, people, 15 years later. Well move on, man. . . . They’re regurgitating the past.

It appeared that the main objection to attending AA was that it was not a personal choice, but rather a forced one. Because the court required so many offenders to attend meetings, this meant that AA was a place that included people who were not committed to sobriety, but were merely complying with a court order.

Many believe that AA is an effective treatment for alcoholism (Miller & McCrady, 1993). A number of investigators have studied the efficacy of AA in achieving long-term sobriety; however, results are mixed (Tonigan, Toscova, & Miller, 1996; Kownacki & Shadish, 1999). Large-scale evaluations of this program are lacking, and the AA organization does not collect records or statistics or information on the degree to which its methods actually “work” (Denzin, 1993). One study (O’Callaghan, 1990) suggests that in the United Kingdom the low flexibility of the AA model, combined with the resistance ensuing from mandating of treatment, decreases its potential effectiveness. Kownacki and Shadish (1999) conducted a meta-analysis of studies evaluating AA that included 12 studies of typical AA meetings, the type to which DWI offenders might be referred. Three of these were randomized studies; these studies found that 12-month abstinence rates of those randomized to AA were significantly poorer compared with treatment. However, in these three studies, the majority of subjects were court-mandated to attend AA. Nonrandomized studies found effects that were significantly larger than those from randomized experiments. The authors point out that those who do well in AA are those who choose to attend.

Victim Impact Panels

Victim Impact Panels (VIPs) show offenders how surviving families and friends of individuals (victims) have been affected by substance-impaired drivers who have injured or killed their loved ones. Attendees typically pay a fee to sit in a small or large group in which victims and/or their family members and friends, commonly members of Mothers Against Drunk Driving, tell their stories for about an hour, often showing pictures of crashes and victims. Our study participants typically indicated that VIPs were emotionally powerful experiences. Nevertheless, after this experience, an equal number of individuals reported recent DOL behavior compared to those with no recent DOL (see Table 1). One participant stated that the VIP she attended exerted a powerful temporary influence, but she still continued to DOL:

You know, first time they sent me to a VIP, [it got to me] because they’re actual people that are sitting there talking about how DWI ruined their lives. Somebody else ran into their family or killed their kid because of that…. And that really gets to you … but then it didn’t stop me. But it did get to me, but it didn’t stop me, ‘cause I kept drinking.

Several individuals who reported feeling out of place in the setting went merely because the court had mandated attendance. They typically reported that VIP had little lasting effect, as in this case:

The only other thing that I remember was I went to one of the [VIPs]…. I remember the burden of having to go to a meeting rather than what the content was about. You know, you’ve gotta feel bad for the parents. You gotta feel bad for the situation and things like that…. It’s a legitimate gripe and you sit back and you reflect, “What if it was me that would’ve caused that?” But as far as a lasting effect, since I wasn’t actually touched by it, I don’t think I’ve ever really identified with it.

In other words, the experience lacked a personalized impact, and the participants could therefore more easily discount it over time. Many participants also opined that they “drive fine” after drinking. Therefore, they did not consider the possibility that they might be involved in a serious DWI crash.

Findings from the literature on VIPs, too, are mixed (Shinar & Compton, 1995; Fors & Rojek, 1999; C’de Baca, Lapham, Liang, & Skipper, 2001). Although some studies demonstrate positive effects of decreased recidivism, others, including the only randomized trial to date, suggest that VIPs do not decrease recidivism and could be harmful (Woodall, Delaney, Rogers, & Wheeler, 2000).

Discussion

We heard varying descriptions of the DWI offenders’ experiences of the consequences of their DOL arrests and convictions. Those offenders with no recent DOL reported more often that they spent time in jail, had more negative reactions to the events surrounding the DWI arrest, and both reported and complained more about consequences, compared with recent offenders. Those who felt shamed, expressed self-disappointment, or set themselves apart from others in the DWI offender population were less likely to be recent offenders. This could indicate that these individuals perceived their DOL behavior as being outside of normal societal behavior, and that their desire to move back within these bounds caused them to rethink that behavior. Spending several hours, or “the night,” in jail was a deterrent for many study participants, and it reduced their propensity to repeat DOL behavior. This reaction is consistent with deterrence theory.

Court-mandated treatment received mixed reviews. Some individuals did not feel the need for treatment and stopped DOL on their own. Assignment to providers with whom they were poorly matched, or whose approach they thought was negative or confrontational delayed progress of others for whom treatment eventually was effective. Study participants came from urban and rural areas of the state. More treatment choices are available in urban and many suburban settings. In urban areas where there are more providers, individuals might be able to request a change of therapist within an agency. However, some rural settings severely limit the choice of providers (Willging, Waitzkin, & Wagner, 2005; Waitzkin et al., 2002). Court-staff individualized case management such as that provided in DWI courts1 could help offenders receive appropriate services. Another possibility is for individuals who understand the local treatment network to work in tandem with probation officers to help individuals who are “ready” to obtain a more individualized package of treatment services. This might lessen or eliminate the time spent in poorly matched treatment settings or with mismatched counselors. Probation officers or treatment providers sometimes attempt to provide such assistance, but they might not be familiar with all the available services or have an opportunity to forge the type of relationship with offenders that would facilitate their accepting help.

In some courts, attendance at 12-step meetings, such as AA, is mandated as an adjunct to or substitute for treatment. Judges sometimes sentenced individuals in the present study to these programs. However, we know little regarding the effectiveness of court-mandated attendance at 12-step or AA meetings in reducing drinking or DOL. This issue, too, deserves additional study. In our research, many offenders who did not feel a need to be “treated” for substance use issues indicated that these programs were only appropriate for others with more severe or different problems. They felt alienated by the process.

Court-mandating offenders with these attitudes might indeed be counterproductive. As several offenders described, this could have the unintended consequence that some attendees at counseling visits or 12-step meetings might be so unmotivated to change that they attend while high or drunk, thus reducing the overall effectiveness of these services. Mandating attendance at such programs, but subsequently offering alternative options to those who have a negative reaction to the initial treatment course, could be a better approach than mandating the same type and duration of services for everyone.

Other sanctions, including VIPs and community service, were not perceived as helpful in reducing future DOL by the majority of recent offenders. More information on how to distinguish individuals who would not benefit from traditional court-mandated treatment at the time of arrest would be useful for those who screen and sentence DWI offenders. Offenders who are not willing to admit that they have alcohol- or drug-related problems are not motivated to quit drinking. A significant number of those interviewed did not completely discontinue DOL behavior because of multiple convictions, but rather were more careful about it and/or engaged in it less often. These individuals did not appreciate nor appear to benefit from their court-mandated sanctions. For this minority, strategies aimed at changing driving behavior, alone or in combination with mandates to be alcohol abstinent, might be most effective. A preliminary study revealed that an injectable medication reduced drinking by a small sample of chronic offenders (Lapham & McMillan, 2010). Results of another study of repeat DWI offenders suggests that forcing offenders to sell their vehicles could be an effective deterrent (Lapham, C’de Baca, Lapidus, & McMillan, 2007). Jones and Lacey found that repeat offenders who had their cars impounded subsequently had 34.2% fewer DOL convictions and 22% fewer traffic convictions overall. They also had 38% fewer crashes, compared to similar drivers who did not have their vehicles impounded (Jones & Lacey, 2000). For the chronic offender, a combination of intensive supervision, mandated interlock installation or other monitored driving restriction, individually tailored treatment (potentially including medication and monitoring of sobriety), and short jail sentences as a consequence for noncompliance could be an effective means for reducing chronic recidivism.

In the quantitative study we found that 10% of the 716 interviewees reported they were recent offenders (Lapham & Skipper, 2011). Of those interviewed for this sub-study, more than a quarter of participants reported being rearrested at some point in time, and 37 specifically stated that they still DOL at least occasionally. This is the major limitation of this study: the subsample represents the opinions of a small number of DWI offenders who might differ from the larger DWI population. We selected about half of the respondents for this study for interviews because they reported chronic impaired driving behaviors over the past 15 years. Therefore these participants are unlike the majority of those reporting impaired driving in national surveys or those arrested for a first offense. Because we oversampled women in the original study (Lapham et al., 2001), more than 50% of those interviewed for this study were women. This population was also older than that of new arrestees, since these participants were first arrested more than 15 years ago. Like the population of the state, a “minority majority state” (Texas, 2005; United States Census Bureau, 2000), the majority of those interviewed were members of minority populations, largely Hispanics and Native Americans.

It is remarkable that so few respondents mentioned the loss of driving privileges. Our results might indicate that the courts did not revoke the licenses of those convicted of DWI or that offenders did not believe this revocation to be a significant sanction for them. The Implied Consent Act, §§66-8-105 to 66-8-112, requires a person under arrest for DWI to provide a breath and/or blood sample to determine his or her drug or alcohol content. If the blood alcohol content (BAC) is above the legal limit, an administration sanction (in effect since 1978) suspends the driver’s license for a minimum of 90 days (Judicial Education Center, 2008). Driver’s license sanctions are one of the most effective deterrence policies (Voas et al., 2010). In addition, few participants spoke about being required to do community service or attend DWI education programs, sanctions that are commonly applied as consequences of a DWI conviction. Such sanctions merit additional research attention because of the high volume of resources required to set up and monitor them.

Chronic drinking drivers pose a substantial risk to themselves and to the community. We conducted this study to gain insight into the perspectives and opinions of offenders, and to examine factors that influence impaired driving behavior. We hope the material presented in this is article raises awareness about the perspectives of DWI offenders and, in turn, facilitates the design and utilization of more effective interventions for these hard-to-treat offenders.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Janet C’de Baca, Vivian Fernandez, and Elizabeth Lilliott for conducting interviews, Shannon Fluder for assistance with coding and analysis, Elizabeth Wozniak for manuscript preparation, Dr. Cathleen Willging for manuscript review, and all the study participants for completing the interviews.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research and authorship of this article: The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, Grant #R01 AA014750.

Biographies

Sandra Lapham, MD, MPH, FASAM, is Director of the Behavioral Health Research Center of the Southwest, a Center of the Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation in Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA.

Elizabeth England-Kennedy, PhD, is a medical anthropologist with the Behavioral Health Research Center of the Southwest.

Footnotes

For descriptions of Drug and DWI/DUI Courts, see Ronan, Scott, Collins, & Rosky, 2009 and Rempel & DeStefano, 2001.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- Beirness DJ, Simpson HM, Mayhew DR. Diagnostic assessment of problem drivers: Review of factors associated with risky and problem driving (Rep. No. TP11549E) Ottawa: Transport Canada, Road Safety and Motor Vehicle Regulation; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Brown TG, Dongier M, Ouimet MC, Tremblay J, Chanut F, Legault L, Ng Ying Kin NM. Brief motivational interviewing for DWI recidivists who abuse alcohol and are not participating in DWI intervention: A randomized controlled trial. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010;34(2):292–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- C’de Baca J, Lapham SC, Liang HC, Skipper BJ. Victim impact panels: Do they impact drunk drivers? A follow-up of female and male, first-time and repeat offenders. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62(5):615–620. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier DW, Longest DL. The technology answer to the persistent drinking driver. Chicago, IL: National Commission Against Drunk Driving; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- De Young DJ. An evaluation of the effectiveness of alcohol treatment, driver license actions and jail terms in reducing drunk driving recidivism in California. Addiction. 1997;92(8):989–997. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1997.9289898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denzin NK. The alcoholic society: Addiction and recovery of the self. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers; 1993. Alcoholics anonymous and alcoholism; pp. 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Dill PL, Wells-Parker E. Court-mandated treatment for convicted drinking drivers. Alcohol Research & Health. 2006;29(1):41–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchscher J, Morgan D. Grounded theory: reflections on the emergence vs. forcing debate. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2004;48(6):605–612. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DS, Morse BJ. In-vehicle BAC test devices as a deterrent to DUI (final report) Washington, DC: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Fell JC. Repeat DWI offenders: Their involvement in fatal crashes. In: Utzelmann HD, Berghaus G, Kroj G, editors. Alcohol, drugs and traffic safety-T92 proceedings. Cologne, Germany: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 1992. pp. 1044–1049. [Google Scholar]

- Fell JC. Traffic tech: Technology transfer series. Vol. 85. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 1995. Feb, Repeat DWI offenders in the United States; pp. 1–4. Retrieved from http://www.nhtsa.dot.gov/people/outreach/traftech/1995/TT085.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Fors SW, Rojek DG. The effect of victim impact panels on DUI/DWI rearrest rates: a twelve-month follow-up. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60(4):514–520. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredlund EV. DWI recidivism in Texas, 1985 through 1988: Results of the DWI recidivism tracking system. Austin, TX: Texas Commission on Alcohol and Drug Abuse; 1991. May, Retrieved from http://www.dshs.state.tx.us/sa/research/criminaljustice/DWIRTS85.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs JP. Crime, punishment, and deterrence. Southwestern Social Science Quarterly. 1968;48(4):515–530. [Google Scholar]

- Gijsbers AJ, Raymond A, Whelan G. Does a blood alcohol level of 0.15 or more identify accurately problem drinkers in a drink-driver population? Medical Journal of Australia. 1991;154:448–452. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1991.tb121173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedlund J, Fell J. Repeat offenders and persistent drinking drivers in the US. 1995 Retrieved from http://www.druglibrary.org/schaffer/Misc/driving/s21p2.htm.

- Houston DJ, Richardson LE. Drinking-and-driving in America: A test of behavioral assumptions underlying public policy. Political Research Quarterly. 2004;57(1):53–64. doi: 10.2307/3219834. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard RL, Craddock SG, Anderson J. Replicated effects of criminal justice involvement on substance abuse treatment retention and outcomes. Fairfax, VA: National Evaluation Data Services; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Jones RK, Lacey JH. State of knowledge of alcohol-impaired driving: Research on repeat DWI offenders. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 2000. Feb, Retrieved from http://www.nhtsa.dot.gov/people/injury/research/pub/Alcohol-ImpairedDriving.html. [Google Scholar]

- Kernodle JR, Joyce CC, Farmer RJ. Changing the behavior of DWI first offenders. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation. 1995;22(3–4):113–128. doi: 10.1300/J076v22n03_09. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kownacki RJ, Shadish WR. Does Alcoholics Anonymous work? The results from a meta-analysis of controlled experiments. Substance Use & Misuse. 1999;34(13):1897–1916. doi: 10.3109/10826089909039431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapham SC, C’de Baca J, Chang I, Hunt WC, Berger LR. Are drunk-driving offenders referred for screening accurately reporting their drug use? Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2002;66(3):243–253. doi: 10.1016/S0376-8716(02)00004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapham SC, C’de Baca J, Lapidus J, McMillan GP. Randomized sanctions to reduce re-offense among repeat impaired-driving offenders. Addiction. 2007;102(10):1618–1625. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapham SC, McMillan GP. Open-label pilot study of extended-release naltrexone to reduce drinking and driving among repeat offenders. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2010 Jun 4;4(3) doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3181eb3b89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapham SC, Skipper B. Current drinking and driving over the limit 15 years after a first DWI conviction. Manuscript submitted for publication 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Lapham SC, Skipper BJ. Does Screening Affect Treatment and Long Term Outcomes of DWI Offenders? American Journal of Health Behavior. 2010;34(6):737–749. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.34.6.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapham SC, Skipper BJ, Owen JP, Kleyboecker K, Teaf D, Thompson B, Simpson G. Alcohol abuse screening instruments: Normative test data collected from a first DWI offender screening program. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1995;56(1):51–59. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapham SC, Skipper BJ, Simpson GL. A prospective study of the utility of standardized instruments in predicting recidivism among first DWI offenders. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58(5):524–530. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapham SC, Smith E, C’de Baca J, Chang I, Skipper BJ, Baum G, Hunt WC. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among persons convicted of driving while impaired. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58(10):943–949. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.10.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapham SC, Todd M. Do the deterrence and social-control models predict driving after drinking 15 years after a DWI conviction? Manuscript submitted for publication. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillen DL, Pang MG, Wells-Parker E, Anderson BJ. Alcohol, personality traits, and high risk driving: A comparison of young, drinking driver groups. Addictive Behaviors. 1992;17(6):525–532. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(92)90062-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller BA, Whitney R, Washousky R. Alcoholism diagnoses for convicted drinking drivers referred for alcoholism evaluation. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1986;10(6):651–656. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1986.tb05162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, McCrady BS. Research on Alcoholics Anonymous: opportunities and alternatives. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers Center of Alcohol Studies; 1993. The importance of research on Alcoholics Anonymous; pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration & National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. A guide to sentencing DUI offenders (Rep. No. DOT HS 808 365) Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- New Mexico DWI laws. 2010 Retrieved May 18, 2010, from DrivingLaws.org website, http://dui.drivinglaws.org/nmexico.php.

- New Mexico Judicial Education Center. New Mexico DWI benchbook: Criminal proceedings involving driving under the influence of alcohol or drugs. Albuquerque, NM: New Mexico Judicial Education Center, Institute of Public Law, UNM School of Law; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nichols JL. Treatment versus deterrence. Alcohol Health & Research World. 1990;14(1):44– 51. [Google Scholar]

- O’Callaghan J. Alcohol, driving and public policy: The effectiveness of mandated A. A. attendance for DWI offenders. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 1990;7(4):87–99. [Google Scholar]

- Peck CR, Peck RC. The comparative effectiveness of alcohol rehabilitation and licensing control actions for drunk driving offenders: A review of the literature. Alcohol, Drugs and Driving. 1994;10:207–215. [Google Scholar]

- Perrine MW, Peck RC, Fell JC. Surgeon General's Workshop on Drunk Driving: Background Papers. Rockville, MD: Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General; 1989. Epidemiologic perspectives on drunk driving; pp. 35–76. Retrieved from http://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/NN/B/C/X/Y/ [Google Scholar]

- QSR International. NVivo 8 qualitative data analysis software [computer software] Cambridge, MA: QSR International (Americans) Inc; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rempel M, DeStefano CD. Predictors of engagement in court-mandated treatment: Findings at the Brooklyn Treatment Court, 1996–2000. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation. 2001;33(4):87–124. doi: 10.1300/J076v33n04_06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Wing J, Wittchen HU, Helzer JE, Babor TF, Burke JD, Farmer A, …Towle LH. The Composite International Diagnostic Interview. An epidemiologic instrument suitable for use in conjunction with different diagnostic systems and in different cultures. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1988;45(12):1069–1077. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800360017003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronan SM, Scott M, Collins PA, Rosky JW. The effectiveness of Idaho DUI and misdemeanor/DUI courts: Outcome evaluation. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation. 2009;48(2):154–164. doi: 10.1080/10509670802641030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ross HL, Nichols LJ. The effectiveness of legal sanctions in dealing with drinking drivers. Alcohol, Drugs and Driving. 1990;6(2):33–60. [Google Scholar]

- Roth R, Marques PR, Voas RB. A note on the effectiveness of the house-arrest alternative for motivating DWI offenders to install ignition interlocks. Journal of Safety Research. 2009;40(6):437–441. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer HJ, Nelson SE, LaPlante DA, LaBrie RA, Albanese M, Caro G. The epidemiology of psychiatric disorders among repeat DUI offenders accepting a treatment-sentencing option. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75(5):795–804. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.5.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinar D, Compton RP. Victim Impact Panels: Their impact on DWI recidivism. Alcohol, Drugs and Driving. 1995;11(1):73–87. [Google Scholar]

- Solnick SJ, Hemenway D. Hit the bottle and run: The role of alcohol in hit-and-run pedestrian fatalities. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1994;55(6):679–684. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stelter R. Experience-based, body-anchored qualitative research interviewing. Qualitative Health Research. 2010;20(6):859–867. doi: 10.1177/1049732310364624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS). Highlights 2002. National Admissions to Substance Abuse Treatment Services (Rep. No. DASIS Series S-22. DHHS Pub. No. SMA 04-3946) Rockville, MD: SAMHSA, Office of Applied Studies; 2004. Retrieved from http://wwwdasis.samhsa.gov/teds02/index.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Summers Z. Coercion and the criminal justice system. In: Petersen T, McBride A, editors. Working with substance misusers. London: Routledge; 2002. pp. 223–233. [Google Scholar]

- Taxman FS, Piquero A. On preventing drunk driving recidivism: An examination of rehabilitation and punishment approaches. Journal of Criminal Justice. 1998;26(2):129–143. doi: 10.1016/S0047-2352(97)0075-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tonigan JS, Toscova R, Miller WR. Meta-analysis of the literature on Alcoholics Anonymous: Sample and study characteristics moderate findings. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1996;57(1):65–72. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Transportation Research Board/National Research Council. Strategies for dealing with the persistent drinking driver. Transportation Research Circular. 1995;437:1–73. [Google Scholar]

- Texas becomes nation’s newest “Majority-Minority” state, Census Bureau announces. 2005 Retrieved June 6, 2005, from the U. S. Census Bureau website, http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb05-118.html.

- United States Census Bureau. American FactFinder: New Mexico DP-2 Profile of Selected Social Characteristics. 2000 Retrieved October 17, 2010, from http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/QTTable?_bm=n&_lang=en&qr_name=DEC_2000_SF3_U_DP2&ds_name=DEC_2000_SF3_U&geo_id=04000US35.

- Urbanoski KA. Coerced addiction treatment: Client perspectives and the implications of their neglect. Harm Reduction Journal. 2010;7:13. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-7-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voas RB, Fell JC, McKnight AS, Sweedler bM. Controlling impaired driving through vehicle programs: An overview. Traffic Injury Prevention. 2004;5(3):292–298. doi: 10.1080/15389580490465409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voas RB, Romano E, Peck R. Validity of the passive alcohol sensor for estimating BACs in DWI-enforcement operations. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67(5):714–721. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voas RB, Tippetts AS, McKnight AS. DUI Offenders Delay License Reinstatement: A Problem? Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010;34(7):1282–1290. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waitzkin H, Williams R, Bock J, McCloskey J, Willging C, Wagner W. Safety-net institutions buffer the impacts of Medicaid managed care: A multi-method assessment in a rural state. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(4):598–610. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.92.4.598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells-Parker E, Bangert-Drowns R, McMillen R, Williams M. Final results from a meta-analysis of remedial interventions with drink/drive offenders. Addiction. 1995;90(7):907–926. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1995.tb03500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whetten-Goldstein K, Sloan FA, Stout E, Liang L. Civil liability, criminal law, and other policies and alcohol-related motor vehicle fatalities in the United States: 1984–1995. Accident Analysis &Prevention. 2000;32(6):723–733. doi: 10.1016/S0001-4575(99)00122-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieczorek WF, Miller BA, Nochajski TH. The limited utility of BAC for identifying alcohol-related problems among DWI offenders. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1992;53(5):415–419. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1992.53.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willging CE, Waitzkin H, Wagner W. Medicaid managed care for mental health services in a rural state. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2005;16(3):497–514. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2005.0060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodall WG, Delaney H, Rogers E, Wheeler DR. A randomized trial of victim impact panels’ DWI deterrence effectiveness. Poster session presented at the annual conference of the Research Society on Alcoholism; Denver, CO. 2000. Jun, [Google Scholar]