Abstract

The initial section deals with basic sciences; among the various topics briefly discussed are the anatomical features of ophthalmic, central retinal and cilioretinal arteries which may play a role in acute retinal arterial ischemic disorders. Crucial information required in the management of central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) is the length of time the retina can survive following that. An experimental study shows that CRAO for 97 minutes produces no detectable permanent retinal damage but there is a progressive ischemic damage thereafter, and by 4 hours the retina has suffered irreversible damage. In the clinical section, I discuss at length various controversies on acute retinal arterial ischemic disorders.

Classification of acute retinal arterial ischemic disorders

These are of 4 types: CRAO, branch retinal artery occlusion (BRAO), cotton wools spots and amaurosis fugax. Both CRAO and BRAO further comprise multiple clinical entities. Contrary to the universal belief, pathogenetically, clinically and for management, CRAO is not one clinical entity but 4 distinct clinical entities – non-arteritic CRAO, non-arteritic CRAO with cilioretinal artery sparing, arteritic CRAO associated with giant cell arteritis (GCA) and transient non-arteritic CRAO. Similarly, BRAO comprises permanent BRAO, transient BRAO and cilioretinal artery occlusion (CLRAO), and the latter further consists of 3 distinct clinical entities - non-arteritic CLRAO alone, non-arteritic CLRAO associated with central retinal vein occlusion and arteritic CLRAO associated with GCA. Understanding these classifications is essential to comprehend fully various aspects of these disorders.

Central retinal artery occlusion

The pathogeneses, clinical features and management of the various types of CRAO are discussed in detail. Contrary to the prevalent belief, spontaneous improvement in both visual acuity and visual fields does occur, mainly during the first 7 days. The incidence of spontaneous visual acuity improvement during the first 7 days differs significantly (p<0.001) among the 4 types of CRAO; among them, in eyes with initial visual acuity of counting finger or worse, visual acuity improved, remained stable or deteriorated in nonarteritic CRAO in 22%, 66% and 12% respectively; in nonarteritic CRAO with cilioretinal artery sparing in 67%, 33% and none respectively; and in transient nonarteritic CRAO in 82%, 18% and none respectively. Arteritic CRAO shows no change. Recent studies have shown that administration of local intra-arterial thrombolytic agent not only has no beneficial effect but also can be harmful. Prevalent multiple misconceptions on CRAO are discussed.

Branch retinal artery occlusion

Pathogeneses, clinical features and management of various types of BRAO are discussed at length. The natural history of visual acuity outcome shows a final visual acuity of 20/40 or better in 89% of permanent BRAO cases, 100% of transient BRAO and 100% of nonarteritic CLRAO alone.

Cotton wools spots

These are common, non-specific acute focal retinal ischemic lesions, seen in many retinopathies. Their pathogenesis and clinical features are discussed in detail.

Amaurosis fugax

Its pathogenesis, clinical features and management are described.

1. INTRODUCTION

Central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) results in sudden, catastrophic visual loss and is therefore one of the most important topics in ophthalmology. Similarly, branch retinal arteriolar occlusion (BRAO) causes sudden segmental visual loss and may recur to involve other branch retinal arterioles. Amaurosis fugax is a common transient acute retinal ischemic condition. Thus, acute retinal arterial occlusive disorders together comprise one of the major causes of acute visual loss. There is a voluminous literature on the subject, with conflicting findings. The subject has been and continues to be rife with misconceptions and mistaken theories. Recent studies have provided new data on various aspects of acute retinal arterial occlusive disorders.

Since 1955 I have investigated the subject comprehensively by doing basic, experimental and clinical studies. Those have revealed new information about the retinal arterial blood supply and its occlusive disorders, contradicting much of the conventional thinking. The objective of this review is to provide a comprehensive overview of this important subject, based on my studies combined with a review of the relevant literature.

The first essential for an in-depth understanding of the retinal arterial occlusive disorders is a good grasp of the relevant basic scientific facts about them; the basic sciences are the foundation of Medicine. Following is a brief discussion of some of those.

2. BLOOD SUPPLY OF THE RETINA

The retina is supplied by the central retinal artery (CRA) and in some eyes also by the cilioretinal artery. The primary source of blood supply to both the arteries is the ophthalmic artery. A brief account of the anatomy of these three arteries is essential to understanding the retinal arterial vascular disorders.

2.1 OPHTHALMIC ARTERY

The ophthalmic artery is the first major branch of the internal carotid artery. However, rarely the ophthalmic artery does not arise from the internal carotid artery. The most common abnormal origin is from the middle meningeal artery by an enlargement of an anastomosis between the recurrent branch of the lacrimal artery and the orbital branch of the middle meningeal artery through the superior orbital fissure or a foramen in the greater wing of the sphenoid (Fig. 1). This anastomosis is present during fetal life and becomes stronger when the ophthalmic artery is stenosed or not connected to the internal carotid artery. In a study of 170 specimens, the ophthalmic artery arose from the middle meningeal artery in 2 (Hayreh and Dass, 1962). In some cases the ophthalmic artery trunk arising from the internal carotid artery may be markedly stenosed, so that the major source of blood supply to the ophthalmic artery is then from the middle meningeal artery; in an anatomical study of 100 specimens (Singh (Hayreh) and Dass, 1960a), this was reported in 4% (Fig. 1). Other extremely rare abnormal modes of origin of the ophthalmic artery have been reported (Hayreh and Dass 1962, Hayreh, 2006). These variations in origin and blood supply of the ophthalmic artery may have clinical significance.

Figure 1.

Variations in origin and course of the ophthalmic artery.

A = Normal pattern; B,C,D, E = The ophthalmic artery arises firm the internal carotid artery as usual, but the major contribution comes from the middle meningeal artery. F,G = The only sources is the middle meningeal artery, as its connection with the internal carotid artery is either absent (F) or obliterated (G).

Abbreviations: ICA = Internal carotid artery; Lac. = Lacrimal artery; MMA = Middle meningeal artery; OA = Ophthalmic artery. (Reproduced from Singh (Hayreh) et al. 1960a.)

2.2 CENTRAL RETINAL ARTERY

This is the primary source of blood supply to the retina. A detailed discussion of it is essential to an understanding of the various aspects of CRAO. A detailed anatomical study of 100 human specimens described the various aspects of the CRA (Hayreh, 1958; Singh (Hayreh) and Dass, 1960a). Briefly, it showed the following:

2.2.1 Source of Origin

It arises from the ophthalmic artery, irrespective of whether the latter is a branch of the internal carotid artery or of the middle meningeal artery. In that study, it was the first branch of the ophthalmic artery in 77%, second in 19% and third in 4%. In two specimens the CRA had two trunks, arising independently from the ophthalmic artery (Fig. 2). Morandi et al. (1998) described a case where the ophthalmic artery arose from the middle meningeal artery and was associated with CRAO, and they considered that such an unusual origin could be a factor for CRAO. As discussed above, I have seen the ophthalmic artery arising from the middle meningeal artery in 6 cases, none with associated CRAO (Hayreh, 1958; Singh (Hayreh) and Dass, 1960a).

Figure 2.

Two trunks (1,2) of the central retinal artery, arising independently from the ophthalmic artery, as seen on splitting open the optic nerve (ON) behind the eyeball. (Reproduced from Hayreh 1958)

2.2.2 Mode of origin

The CRA arose independently in 37.5% from the ophthalmic artery, in 59.5% by a common trunk with one or another posterior ciliary artery (PCA) (Fig. 3) and extremely rarely with other branches of the ophthalmic artery. The fact that the CRA may arise by a common trunk with a PCA has great clinical significance, as discussed later.

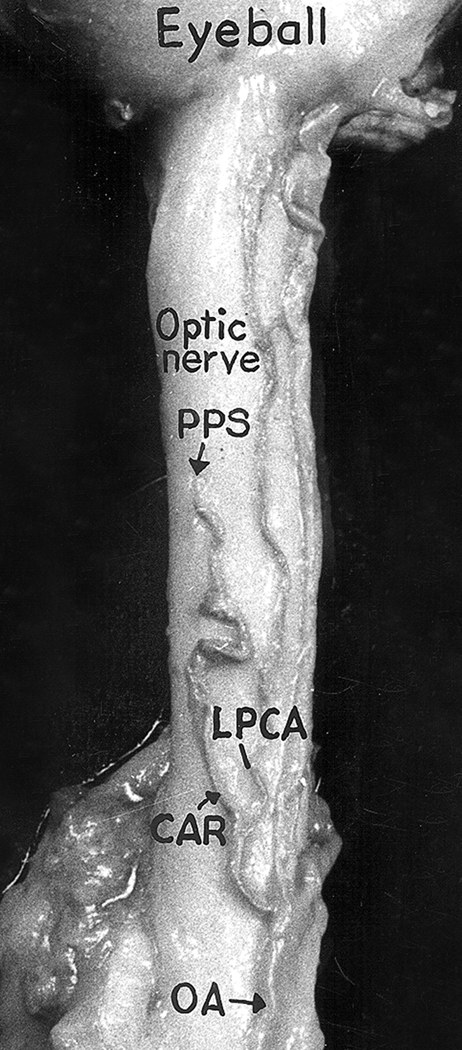

Figure 3.

The central artery of the retina (CAR) arising by a common trunk with lateral posterior ciliary artery (LPCA) from the ophthalmic artery (OA). PPS = Point of penetration of the central artery of the retina into the optic nerve sheath. (Reproduced from Hayreh 1958)

2.2.3 Course

The course of the CRA is divided into 3 parts:

2.2.3.1 Intraorbital part

This is from its origin from the ophthalmic artery till it pierces the optic nerve sheath. This site of penetration in this study was found to vary from 5.0 mm to 15.5 mm (median 10 mm; mean 9.8 ± 1.8 mm) from the eyeball, and was located in the inferior medial (86%), inferior lateral (13%) or lateral (1%) aspect of the optic nerve.

2.2.3.2 Intravaginal part

This is situated in the subdural and subarachnoid spaces of the optic nerve sheath. The artery formed a tortuous loop in this part in 8%. The length of this section of the artery is 1.2 to 4.0 mm.

2.2.3.3 Intraneural part

This lies in the optic nerve. The artery enters the optic nerve in a well-defined fissure on the inferior surface of the optic nerve anterior to the site of penetration into the dural sheath and carries a fold of pia with it. The initial, vertical part of this section runs upwards and slightly forward to reach the center of the optic nerve, and then runs forwards horizontally in the center of the optic nerve to the optic disc, where it divides into its terminal branches. In the specimens with the two trunks of the CRA, the vertical part was missing and the two trunks ran straight to the optic disc from their point of penetration into the nerve (Fig. 2).

2.2.4 Branches

2.2.4.1 Incidence

In that study, when the artery had a satisfactory injection throughout its course (64 specimens), branches were present in 97% (Hayreh, 1958; Singh (Hayreh) and Dass, 1960a). They arose from the intraorbital part only in 1.6%, intravaginal part only in 9.4%, all three parts in 42.2% and from intravaginal and intraneural in 29.7%, intravaginal and intraorbital in 9.4% and intraorbital and intraneural parts in 4.7%. The size of the branches varied widely, from minute to as big as the CRA itself.

2.2.4.2 Distribution

Branches arising from the three parts of the CRA (Figs. 4–6) have variable supply.

Figure 4.

Two views of the same optic nerve in the retrobulbar regions – (A) from inferior aspect and (B) from the superior aspect after removal of dural sheath. They show pial branches of the central retinal artery (CRA) arising from the intravaginal part of the artery, and their anastomoses anteriorly with recurrent pial branches of the circle of Zinn and Haller (CZ) and posteriorly with collateral (Col.) branches from the ophthalmic artery (O.A.). (Reproduced from Hayreh 1958)

Figure 6.

Schematic representation, showing:

(A) The course of central retinal artery and its branches and anastomoses, central retinal vein and its tributaries, and blood supply of the optic nerve.

(B) Blood vessels on the optic disc and in the retina.

(Modified from Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol 1974;78:OP240–OP254.).

Abbreviations: A = arachnoid; C = choroid; CRA = central retinal artery; Col. Br. = Collateral branches; CRV = central retinal vein; D = dura; LC = lamina cribrosa; OD = optic disc; ON = optic nerve; PCA = posterior ciliary artery; PR = prelaminar region; R = retina; S = sclera; SAS = subarachnoid space.

2.2.4.2.1

Intraorbital branches usually supply the dural sheath, about half of them penetrated the sheath to ramify on the pia of the optic nerve (Fig. 6) and a rare one entered the optic nerve.

2.2.4.2.2

Intravaginal branches ramified on the pia of the optic nerve in all specimens anterior to the site of penetration of the CRA and, in about half, also posterior to that, so that they supply the optic nerve from the eyeball to some distance posterior to the site of penetration of the dural sheath (Fig. 4). These branches ramified on the optic nerve all around the nerve in 15%, on the inferior aspect only in 36% and variably on other regions in the rest. Thus, intravaginal branches play an important role in the blood supply of the optic nerve. They are also important in establishing anastomoses in the event of CRA occlusion at its site of penetration into the dural sheath (see below),

2.2.4.2.3

Intraneural branches run radially as well as backwards and forward in the septa between the nerve fiber bundles to supply the optic nerve (Fig. 5,6). The CRA does not give out any branch in the region of the lamina cribrosa and the prelaminar region.

Figure 5.

This shows intravaginal (indicated by smaller arrow) and intraneural (anterior to the bigger arrow with asterisk where the optic nerve is split open to show the central region of the optic nerve) course of the central retinal artery (CRA) from below. It shows 2 pial branches (at and before the arrow with asterisk) and 6 intraneural branches anterior to that. (Reproduced from Hayreh 1958)

2.2.4.3 Anastomoses by the branches

This is an important subject when dealing with CRAO. Numerous anastomoses are established by the branches of the CRA with other branches of the ophthalmic artery, most on the pia of the optic nerve and between the pial branches of the CRA (mostly arising from the intravaginal part of the artery) and the recurrent pial branches of the circle of Haller and Zinn, and with the pial branches from the collateral branches of the ophthalmic artery (Figs. 4,6). These branches are most commonly situated on the inferior aspect of the optic nerve, less commonly on other aspects. The study showed that all these pial anastomoses were usually large enough to establish a variable amount of collateral circulation in the event of occlusion of the CRA at its site of penetration into the optic nerve sheath. This was also demonstrated by fluorescein fundus angiography in various studies dealing with experimental occlusion of the CRA at its site of penetration into the optic nerve in monkeys (Hayreh and Weingeist, 1980a; Petrig et al., 1999; Hayreh et al., 2004b).

2.2.5 Intraretinal Branches of the Central Retinal Artery

At the optic disc the CRA usually divides into two main branches (superior and inferior) and the two then further divide into temporal and nasal branches, which supply the four quadrants of the retina; however, there is marked variation in their vascular pattern and supply. These intraretinal arterial branches mainly lie in the nerve fiber and ganglion cell layer, usually under the internal limiting membrane; however, at the arteriovenous crossing they may extend down to the inner nuclear layer. The various branches, by multiple divisions, finally end in terminal or precapillary arterioles, which are usually not visible on ophthalmoscopy. Terminal arterioles play an important role in the regulation of retinal blood flow by constriction or dilation.

The so-called “branch retinal arteries” are in fact arterioles after the first branching in the retina, because their diameter near the optic disc is about 100 µm, which is typically the diameter of an arteriole, and, unlike arteries, they possess neither an internal elastic lamina nor a continuous muscular coat. This differentiation from arteries is important in understanding their pathological involvement in some diseases, e.g., giant cell arteritis (GCA). There are normally no interarterial or arteriovenous anastomoses in the retina, so that the retinal vascular bed is an end-arterial system.

2.3 CILIORETINAL ARTERY

These arteries belong to the PCA system. They usually arise from the peripapillary choroid or directly from one of the short PCAs. The cilioretinal artery has a characteristic hook-like appearance at its site of entry into the retina at the optic disc margin, usually on the temporal side and less frequently elsewhere. The size and area of the retina supplied by a cilioretinal artery vary widely (Figs. 7–10) - from a minute artery supplying a tiny area of the peripapillary retina (Fig. 7), to supplying half (Fig. 10A) or the entire retina (Fig. 10B). A histological study of two eyes of a rhesus monkey showed multiple cilioretinal arteries (8 in the right and 3 in the left) and the CRA was absent in the right eye and supplied only the upper part of the retina in the left (Hayreh, 1963). I have seen two cases where cilioretinal arteries supplied the entire retina. Similarly, Hegde et al. (2006) reported a case of a cilioretinal artery supplying the entire retina.

Figure 7.

Fundus photograph of the left eye with CRAO, with a tiny patent cilioretinal artery (Arrow). It shows the classical cherry-red spot in macular region and attenuated retinal vessels with “cattle-trucking” or “box-carring” in them.

Figure 10.

Two fundus photographs.

A = This shows a large cilioretinal artery (arrow with one asterisk) supplying the superior half of the retina, and the central retinal artery (arrow with two asterisks) supplying the lower half of the retina.

B = This shows two (1,2) large cilioretinal arteries supplying the entre retina and absent central retinal artery.

In 1963, I reviewed the literature on cilioretinal arteries since 1856 (Hayreh, 1963). The incidence of presence of a cilioretinal artery had been described variably by different studies, based on variable numbers of eyes, and it varied from none to 25%. Collier (1957) evaluated various aspects of the cilioretinal artery in 1,000 subjects and found an incidence of 22%, bilateral in 17% of cases, frequently associated with congenital optic disc abnormalities and most common in hypermetropic astigmatism. The incidence in all these studies was based on ophthalmoscopic evaluation, however, that can be deceptive, because what looks like a cilioretinal artery on ophthalmoscopy may actually be an early intraneural branch of the CRA, emerging at the optic disc as a separate artery. The most reliable way to ascertain the true incidence is by fluorescein fundus angiography. This is because the cilioretinal artery fills concurrently with the filling of the choroid and usually before the start of filling of the CRA. Justice and Lehmann (1976) evaluated the incidence of cilioretinal arteries in 2,000 eyes of 1,000 consecutive patients by reviewing stereoscopic color fundus photographs and fluorescein angiograms. One or more cilioretinal arteries were present in 49.5% of all patients or in 32% of the eyes. The arteries occurred bilaterally in 15% and contributed to some portion of the macular circulation in 19% of the patients. Great variation in size, number, and distribution of cilioretinal vessels was observed. The incidence reported by this study is much higher than reported previously based on ophthalmoscopic evaluation, because in this study early phase fluorescein angiography helped in the detection of these vessels that might otherwise have been missed.

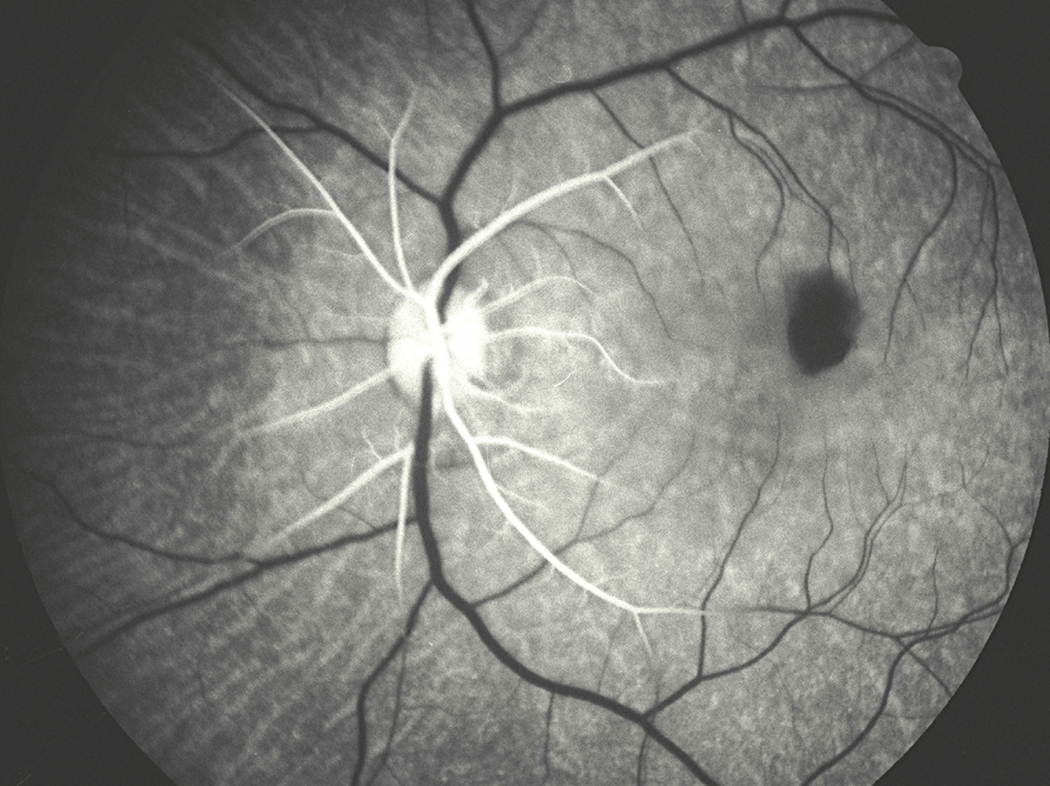

2.4 RETINAL CAPILLARY BED

Each terminal arteriole gives out a plexus of 10–20 interconnected capillaries (Fig. 11). Capillaries lie between the feeding arterioles and venules. Around the retinal arterioles there is a capillary free zone. The retinal capillaries are arranged in two layers (Fig. 12); (i) superficial layer in the ganglion cell and nerve fiber layers, and (ii) deeper layer in the inner nuclear layer which is denser and more complex than the superficial layer. However, in the posterior retina, in the peripapillary region there may be three layers and in the perifoveal region there is only one layer. The capillaries are absent in the foveal avascular zone of about 400–500 µm in diameter. Also, in the peripheral retina the deep layer disappears and only the superficial layer is left, with a wider network. At the extreme periphery of the retina, there is an avascular zone of about 1.5 mm width.

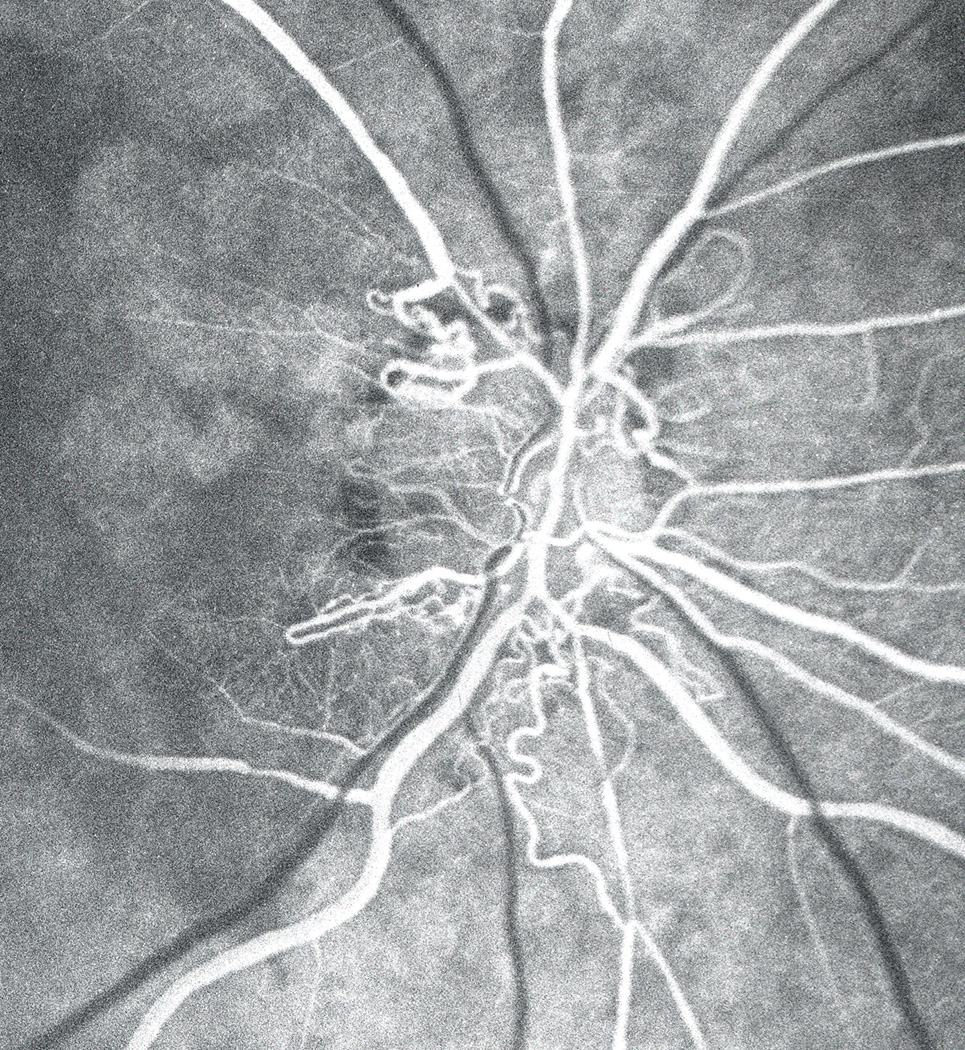

Fig. 11.

Fluorescein fundus angiogram of a rhesus money eye showing retinal vessels and capillary network. A = Retinal arteriole; V = Retinal vein.

Figure 12.

Schematic representation of two layers of the retinal capillaries and radial peripapillary capillaries (RPC). (Reproduced from Henkind P: Trans Am Ophthalmol Otolaryng 1969;73:890–897.).

2.4.1 Radial peripapillary capillaries

The following special characteristics distinguish them from other retinal capillaries (Fig. 13):

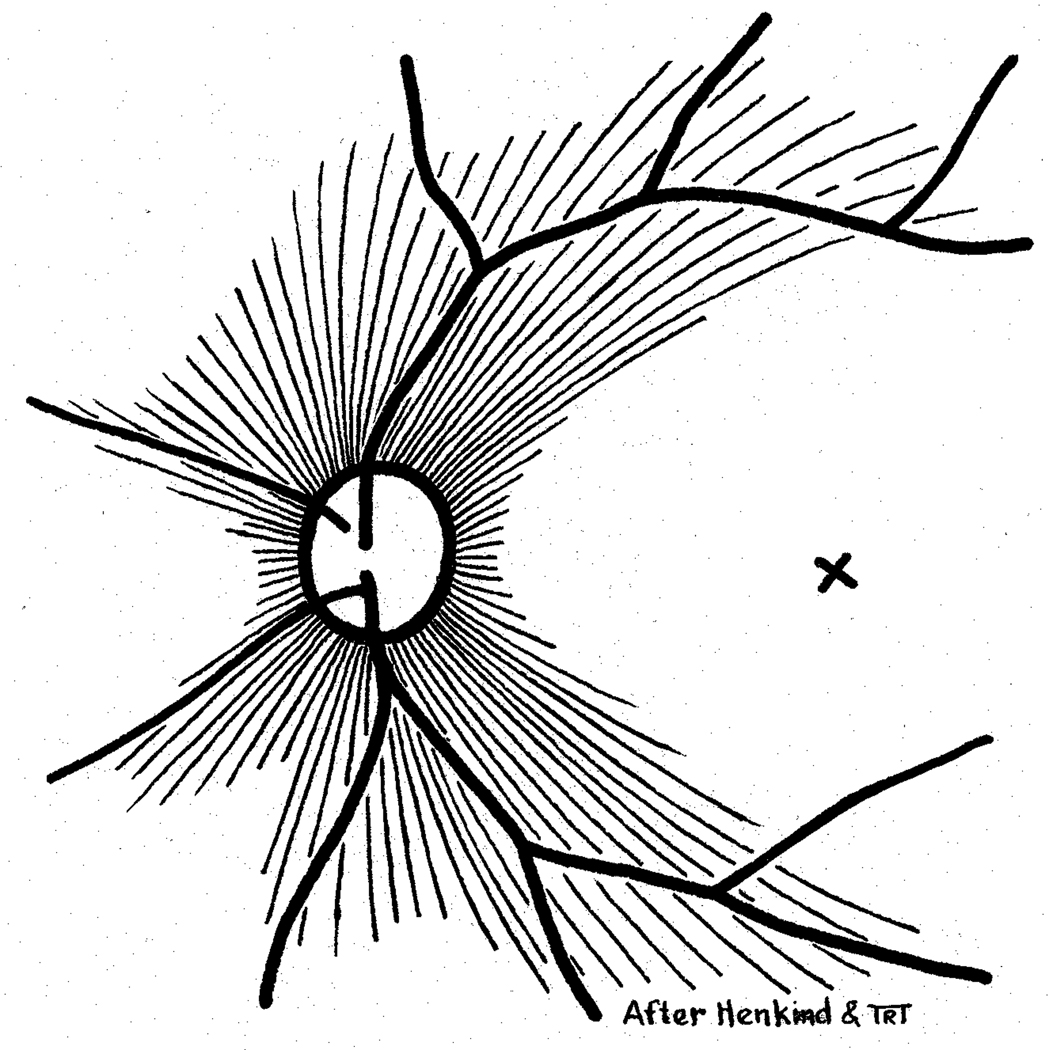

Figure 13.

Schematic representation of radial peripapillary capillaries. X = Site of foveola (Reproduced from Henkind P: Br J Ophthalmol 1967;51:115–123.).

2.4.1.1

They are long, straight capillaries, measuring several hundred microns to several millimeters.

2.4.1.2

They form the most superficial layer, lying among the superficial nerve fibers, along the superior and inferior temporal arcades of the retinal vessels and the peripapillary region.

2.4.1.3

They rarely anastomose with one another.

2.4.1.4

They arise from the peripapillary retinal arterioles, and drain into retinal venules or veins on the optic disc.

Because of these characteristics, the radial peripapillary capillaries play an important role in the development of several lesions. For example, cotton wool spots are often located in their distribution, which indicates that they may play a role in their pathogenesis (see below). Also, in chronic optic disc edema these capillaries become dilated and develop microaneurysms and hemorrhages.

The wall of the retinal capillaries consists of endothelial cells, pericytes and basement membrane. Their diameter varies from 3.5 to 6 µm. The endothelial cells have tight cell junctions, which exercise a blood-retinal barrier. In addition to the endothelial cells, there are also pericytes which form a discontinuous layer within the basement membrane of the capillaries. They have a contractile property, by virtue of which they may play a role in regulating blood flow in the capillaries and autoregulation of blood flow (see below).

2.5 RETINAL VENOUS DRAINAGE

The postcapillary venules drain the blood from the capillaries, but occasionally capillaries may join a major vein directly. The terminal arterioles and postcapillary venules are situated in an alternating pattern, with the capillary bed in between the two (Fig. 11). The postcapillary venules drain into bigger venules and finally into the major branch retinal veins, which join at the optic disc to form the central retinal vein. In the central part of the retina, the branch retinal veins and arterioles usually run in close association and at places cross one another, but in the peripheral retina, the veins do not follow the course of the arterioles.

During the third month of intrauterine life, there are always two trunks of the central retinal vein in the optic nerve, one on either side of the CRA, one of which usually disappears before birth; however, in 20% of eyes a dual-trunked central retinal vein persists into adult life. There is usually one central retinal vein, but in 20% there are two trunks of the central retinal vein in the optic nerve (Chopdar, 1984); this represents a congenital anomaly (Fig. 14) (Hayreh and Hayreh, 1980). In such eyes, only one of the two trunks may develop occlusion in the optic nerve, resulting in development of the clinical entity called "hemi-central retinal vein occlusion” (Hayreh and Hayreh, 1980). The central retinal vein travels in the optic nerve temporal to the artery, where the central retinal vein and artery lie in the center of the optic nerve, surrounded by a fibrous tissue envelope (Fig. 15). During its intraneural course, the vein receives a large number of tributaries (Fig. 6). The central retinal vein exits the optic nerve and its sheath, and finally drains into either the superior ophthalmic vein or directly into the cavernous sinus.

Figure 14.

Schematic representation of two-trunked central retinal vein in the optic nerve. For abbreviations see Figure 6. (Reproduced from Hayreh and Hayreh 1980)

Figure 15.

Light micrograph showing the central retinal vessels and surrounding fibrous tissue envelope, as seen in a transverse section of the central part of the retrolaminar region of the optic nerve. (Masson’s trichrome staining) CRA = Central retinal artery; CRV = Central retinal vein. FTE = Fibrous tissue envelope, NASAL = Nasal side of the optic nerve. (Reproduced from Hayreh et al. 1999 J Glaucoma;8:56–71.)

3. NERVE SUPPLY TO RETINAL VESSELS

During its intraorbital and intraneural portion the CRA has adrenergic nerve supply by a sympathetic nerve called the nerve of Tiedemann (Hayreh and Vrabec, 1966); however, the retinal branches of the CRA have no adrenergic nerve supply. Therefore, there is no autonomic innervation of the retinal vascular bed.

4. BLOOD–RETINAL BARRIER

The blood-retinal barrier plays an important role in the regulation of the microenvironment in the retina. There are two types of blood-retinal barrier:

4.1 Inner blood-retinal barrier

This lies in the retinal vessels. It is produced by the tight cell junctions between the endothelial cells of the vessels (due to the presence of extensive zonulae occludentes). The tight interendothelial cell junctions block movement of macromolecules from the lumen toward the interstitial space. Pericytes, Müller cells and astrocytes also contribute to the proper functioning of this barrier.

4.2 Outer blood-retinal barrier

Tight cell junctions between the retinal pigment epithelial cells also produce a blood-retinal barrier, preventing the leakage of fluid from the choroid into the retina. This barrier breaks down when the retinal pigment epithelial cells are destroyed or subjected to ischemia, as in hypertensive choroidopathy (Hayreh et al., 1986). The retinal tissue itself has no barrier in its stroma, so fluid may diffuse from one part to the adjacent areas (Hayreh et al., 1986).

5. AUTOREGULATION OF RETINAL BLOOD FLOW

The object of blood flow autoregulation is to maintain the blood flow in a tissue relatively constant during changes in its perfusion pressure. This is an important mechanism to regulate blood flow. The retinal circulation has efficient autoregulation. The exact mechanism and site of autoregulation are still unclear, except that it most probably operates by altering the vascular resistance. It is generally considered a feature of the terminal arterioles; with the rise or fall of perfusion pressure beyond normal levels, the terminal arterioles constrict or dilate, respectively, to regulate the vascular resistance and thereby the blood flow. Studies have suggested that pericytes in the retinal capillaries play a role in autoregulation as well, because of their contractile property (Anderson, 1996; Anderson and Davis, 1996). The metabolic needs of the tissue also regulate the autoregulation. But autoregulation works only within a critical range of perfusion pressure, so that it breaks down with any rise or fall of the perfusion pressure beyond the critical autoregulatory range.

6. RETINAL TOLERANCE TIME TO ACUTE ISCHEMIA

Retinal tolerance to acute ischemia is key to understanding the retinal arterial occlusive disorders and their management. We investigated this experimentally in 38 elderly, atherosclerotic and hypertensive rhesus monkeys (mimicking patients with CRAO), producing transient occlusion of the CRA varying from 97 to 240 minutes, by temporarily clamping the CRA at its site of entry into the optic nerve (Hayreh et al., 2004b). The retinal circulation, function and changes were evaluated before and during CRA clamping, after unclamping, and serially thereafter by stereoscopic color fundus photography, fluorescein fundus angiography, electroretinography, and visual evoked potential. Finally, the eyes and optic nerves were examined histologically. These studies showed that the retina of old, atherosclerotic, hypertensive rhesus monkeys suffers no detectable damage with CRAO for 97 minutes, but above that level, the longer the CRAO, the more extensive the irreversible damage (Hayreh et al., 2004b). The study suggests that CRAO lasting for about 240 minutes results in massive, irreversible retinal damage. This was further confirmed by a study of retinal nerve fiber layer damage and optic disc changes in these monkey eyes; there was no apparent morphometric evidence of damage with CRAO of less than 97 minutes, but, occlusion of 105 minutes but less than 240 minutes produced a variable degree of damage, while occlusion for 240 minutes or more produced total optic nerve atrophy and nerve fiber damage (Hayreh and Jonas, 2000).

This study (Hayreh et al., 2004b) also showed that, surprisingly, contrary to the prevalent impression, the retina of old, atherosclerotic, hypertensive rhesus monkeys could tolerate ischemia for a much longer time than in younger, normal rhesus monkeys in an exactly identical study (Hayreh et al., 1980; Hayreh and Weingeist, 1980b); the reasons for that discrepancy are discussed at length elsewhere (Hayreh et al., 2004b). Those studies also showed that in eyes where the retinal circulation was restored to normal after CRAO of more than 2 but less than 4 hours’ duration, retinal function did not show signs of major improvement until many hours or even a day or more after restoration of circulation – the longer the ischemia, the longer the lag before any improvement of function started. This finding is important clinically; because the notion has unfortunately arisen that visual recovery can occur in eyes with CRAO lasting for much longer than 4 hours and that belief has fostered the use of various advocated treatments for CRAO of much longer than 4 hours (see below). In view of the above facts, treatment instituted at any time beyond 4 hours, after the onset of CRAO cannot have any scientific rationale for improvement of vision.

7. CAUSES OF RETINAL ARTERIAL OCCLUSION

In the management of a disease, the first essential requisite is to know what caused it; therefore the first necessary task is to find out the causes of retinal arterial occlusion. There is a colossal amount of literature about the association of retinal arterial occlusion with a large variety of systemic and hematological conditions. Most of that is based on anecdotal case reports, and, given that, it is not always possible to establish a true cause-and-effect relationship between the CRAO/BRAO and the reported disease. The following associations with retinal artery occlusion have been reported:

7.1 Both CRAO and BRAO

In the literature, the information for all types of retinal artery occlusion is often combined, instead of type of retinal artery occlusion being specified. CRAO and BRAO have been reported with a variety of conditions, including the following: embolism from atheromatous plaques in the carotid arteries, during carotid angiography and stenting or cardiac cauterization or coronary angiography, atrial fibrillation, mitral or aortic valve mass, bacterial endocarditis, atrial myxoma, patent foramen ovale, Takayasu’s arteritis, and migraine. Other reported rare causes are: after radial optic neurotomy or after retinal surgery, and herpes zoster ophthalmicus.

7.2 CRAO Alone

In addition many conditions have been reported as associated with CRAO alone. These include the following: polyarteritis nodosa, Wegener's granulomatosis, Churg-Strauss syndrome, Behcet's disease, sarcoidosis, sickle cell disease, carotid artery dissection, aneurysm of the internal carotid artery, plasma lipoprotein(a) levels, high homocysteine levels, higher lupus anticoagulant, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, leukemia, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, T-cell lymphoma, oral contraceptives, incontinentia pigmenti, Fabry’s disease, cat scratch disease, following severe blow-out fracture, perioperative CRAO, peribulbar anesthesia or forehead injection with a corticosteroid suspension, and laser in situ keratomileusis. Transient CRAO has even been described following viperine snake bite (Singh et al., 2007; Hayreh, 2008c).

Combined CRAO and central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO) has often been reported. This is not a true CRAO but it is actually secondary to occlusion of the central retinal vein in the region of the lamina cribrosa; the mechanism of CRAO in this case is that blood cannot get out of the retinal vascular bed because of complete blockage in the central retinal vein – naturally if the blood cannot get out of the retina, it cannot get in, resulting in secondary CRAO (Hayreh, 2005). Therefore when CRAO is associated with CRVO, it is a hemodynamic blockage rather than actual block of the CRA, as discussed below in detail.

7.3 BRAO Alone

Apart from those already mentioned, association of a large number of conditions with BRAO alone has been reported. These include the following: retinal vasculitis, multifocal retinitis, toxoplasmic chorioretinitis, prepapillary loops, Crohn's disease, Whipple disease, Lyme disease, Viagra, or Meniere's disease. BRAO associated with GCA has been reported (Fineman et al., 1996), however, this is not credible because, as discussed above, the so-called “branch retinal arteries” in fact are arterioles. GCA is a disease of the medium-sized and large arteries and not of the arterioles. This “BRAO due to GCA” is actually cilioretinal artery occlusion due to involvement of the PCA by GCA, as discussed below.

There are large numbers of reports of BRAO in Susac's Syndrome, which consists of the clinical triad of encephalopathy, BRAO, and hearing loss. It is an autoimmune endotheliopathy affecting the precapillary arterioles of the brain, retina, and inner ear (cochlea and semicircular canals). The age range extends from 7 to 72 years, but young women (20–40) are most vulnerable (Rennebohm and Susac, 2007). I have, myself, seen a few patients with Susac's Syndrome and all were young women (Gordon et al., 1991). It tends to produce recurrent BRAO.

7.4 Cilioretinal Artery Occlusion

This has been reported in association with embolism, CRVO or GCA (see below), Viagra, systemic lupus erythematosus, antiphospholipid syndrome, migraine, and pregnancy.

In addition to these anecdotal reports of a few cases, the association of retinal artery occlusion with various systemic conditions has been reported by some large studies. Following are a few recent reports.

Schmidt et al. (2007) compiled cardiovascular risk factor findings (RFs) in a retrospective study of 134 patients with BRAO, 253 patients with CRAO, and 29 patients with hemi-CRAO. There were 66% males and 34% females, and the mean age was 66 years (range: 18–90). RFs were found in 58% - arterial hypertension in 76% (74 % among BRAO, 80% among CRAO, and 79% among hemi-CRAO). RFs such as arterial hypertension, carotid artery diseases, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, hyperuricemia, and chronic smoking did not differ statistically between patients with BRAO, CRAO or hemi--CRAO. But visible emboli in retinal arteries were observed in patients with BRAO (47 %,), or hemi-CRAO (41 %), much more often than in patients with CRAO (11 %). They concluded that every patient with retinal arterial obstruction should undergo extensive examination for RFs.

Rudkin et al. (2010) in a retrospective study of 33 consecutive patients with non-arteritic CRAO, found that 64% had at least one new vascular risk factor, with hyperlipidemia in 36% and hypertension in 27%. Nine patients had more than 50% of ipsilateral carotid stenosis; six of these proceeded with carotid endarterectomy or stenting. Systemic ischemic events occurred after CRAO in two patients (stroke and acute coronary syndrome).

Greven et al. (1995) reported 21 patients under 40 years old with retinal arterial occlusion. They found that cardiac valvular disease was the most commonly recognized etiologic agent (19%). Various associated factors leading to a hypercoagulable state or embolic condition were identified in 19 patients (91%). They concluded that retinal arterial occlusions in young adults occur via multiple mechanisms.

Hayreh et al. (2009b) in a prospective study of 439 consecutive untreated patients with retinal artery occlusion (249 CRAO, 190 BRAO) found that in both nonarteritic CRAO and BRAO the prevalence of diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension, ischemic heart disease, and cerebrovascular accidents were significantly higher compared to the prevalence of these conditions in the matched US population (all p<0.0001). Smoking prevalence, compared to the US population, was significantly higher for males (p=0.001) with nonarteritic CRAO and for females with BRAO (p=0.02). The ipsilateral internal carotid artery had ≥50% stenosis in 31% of nonarteritic CRAO patients and 30% of BRAO, and plaques in 71% of nonarteritic CRAO and 66% of BRAO. An abnormal echocardiogram with embolic source was seen in 52% of nonarteritic CRAO and 42% of BRAO. Thus, this study showed that in CRAO as well as BRAO the prevalence of various cardiovascular diseases and smoking was significantly higher than the prevalence of these conditions in the matched US population. Embolism is the most common cause of CRAO and BRAO; plaque in the carotid artery is usually the source of embolism and less commonly the aortic and/or mitral valve. The presence of plaques in the carotid artery is generally of much greater importance than the degree of stenosis in the artery. This study showed that, contrary to a prevalent misconception (Duker et al., 1991), there is no cause-and-effect relationship between CRAO and neovascular glaucoma (see below) (Hayreh et al., 2009b).

Hematologic abnormalities

Information in the literature on the association of retinal artery occlusion with hematologic abnormalities is contradictory. Reported hematologic abnormalities include familial and acquired thrombophilia (low protein C, lupus anticoagulant) in patients with CRAO (Glueck et al., 2008), antiphospholipid antibodies (Palmowski-Wolfe et al., 2007) and homocysteinemia (Weger et al., 2002; Glueck et al., 2008); however, factor V Leiden, prothrombin 20210A and homozygosity for the MTHFR C677T have not been found to be associated with retinal artery occlusion (Weger et al., 2002). Salomon et al. (2001) in a study of 21 consecutive patients with retinal artery occlusion found at least one thrombophilic marker in 43%. Chua et al. (2006) in the Blue Mountains Eye cross-sectional population-based study of 3509, age ≥49 years concluded that elevated serum homocysteine is weakly associated with increased odds of retinal emboli in this age-group. Atchaneeyasakul et al. (2005) in a retrospective, case-control study found no association between plasma homocysteine level and retinal vascular occlusion, and also found that anticardiolipin IgG antibody was not a major cause of the development of retinal vascular occlusive disease.

7.6 Retinal emboli

Thus, in summary, embolism is by far the most common cause of nonarteritic CRAO and BRAO. The major source of emboli is carotid artery disease - most commonly plaques, and much less frequently stenosis. The heart is also an important source of these emboli, though less than the carotid artery.

7.6.1 Types of retinal emboli

As discussed above, the most common cause of retinal artery occlusion is embolism. Arruga and Sanders (1982) showed that 74% of retinal emboli are made of cholesterol (Hollenhorst plaque), 10.5% calcific material and only 15.5% platelet-fibrin. The carotid artery and the heart are the most common sources of embolism to the retinal arteries. In the carotid artery, plaque is the most common source. In the heart, sources of emboli are aortic and mitral valvular lesions, patent foramen ovale, and left atrial myxoma (Schmidt et al., 2005). The study by Hayreh et al. (2009b) showed that the most common abnormality and source of embolism in the carotid arteries is plaque(s) (66%); significant carotid stenosis (i.e. ≥50%) was seen in only 30%. In that study, relating carotid Doppler/angiography findings to echocardiography findings showed an abnormal echocardiogram with embolic source in 62% of those with plaque in the carotid artery in CRAO and in 44% with BRAO. This means that in such cases, the embolus could have come from either the carotid artery or the heart or possibly both. This indicates that one has to evaluate both sources for embolism in all patients with CRAO and BRAO.

7.7

Carotid artery disease, apart from embolism, can also produce CRAO by the following two other means:

7.7.1 Hemodynamic cause

A significant stenosis (usually about 70% or more), or complete occlusion of the internal carotid artery can produce hemodynamically induced retinal and/or ocular ischemia, by markedly reducing the ocular blood flow. A fall of blood pressure, particularly nocturnal arterial hypotension (Fig. 16), with a markedly stenosed or occluded internal carotid artery, can result in transient CRAO (see below) (Hayreh and Zimmerman, 2005). Anderson et al. (2002) found that the hemodynamic effects of carotid artery stenosis do not appear to be more important in the pathogenesis of retinal events than hemispheric ones; whereas severe stenosis of the extracranial internal carotid artery is the most common identified condition associated with retinal and ocular ischemia (Hayreh and Podhajsky, 1982; Mizener et al., 1997; Sharma et al., 1998; Babikian et al., 2001).

Figure 16.

A 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure recording, starting at about 11 AM and ending at about 10 AM next day. Note that during the waking hours the blood pressure is perfectly normal but shows a marked drop during the sleeping hours (nocturnal arterial hypotension). (Reproduced from Hayreh et al. 1999.)

Sharma et al. (1998) found hemodynamically significant carotid artery stenosis in only 19% of patients with acute retinal artery occlusion. In our study, ≥ 80% stenosis of the internal carotid artery was seen in 18% of CRAO cases and 14% of BRAO (Hayreh et al., 2009b). We have found that the presence of a retinal embolus is a poor predictor of hemodynamically significant carotid stenosis on carotid Doppler, as has also been pointed out by others (Sharma et al., 1998; Wakefield et al., 2003; McCullough et al., 2004).

7.7.1 Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine) induced arterial spasm

Serotonin is released by platelet aggregation on atherosclerotic plaques in the carotid artery. Serotonin is a vasoconstrictor. A study on atherosclerotic monkeys found that Serotonin, in the presence of atherosclerotic lesions, can cause transient or complete occlusion or impaired blood flow in the CRA, by producing a transient spasm (Hayreh et al., 1997) (Fig. 17). This may contribute to CRAO and retinal ischemic disorders,

Figure 17.

Fluorescein fundus angiograms of right eye of an atherosclerotic cynomolgus monkey.

(A) Fluorescein fundus angiogram about 4 minutes after the start of serotonin infusion, showing normal filling of the choroidal circulation but complete occlusion of the central retinal artery.

(B) An angiogram about 2 hours after stopping serotonin infusion, showing normal filling of the central retinal artery and choroidal circulations. (Reproduced from Hayreh et al. 1997.)

7.8 GIANT CELL ARTERITIS AND RETINAL ARTERIAL OCCLUSION

A study investigated this in 170 consecutive patients with temporal artery biopsy confirmed GCA (Hayreh et al., 1998b). In this study 50% (85 patients, 123 eyes) presented with ocular involvement. Of the 123 eyes, CRAO was present in 18%, cilioretinal artery occlusion in 25%, and ocular ischemia in 1%. Cilioretinal artery occlusion in GCA has been erroneously diagnosed as BRAO (Fineman et al., 1996); this is because the so-called branch retinal arteries are in fact arterioles and not arteries, and GCA is a disease of medium-sized and large arteries and not of arterioles. In almost every patient with GCA, fluorescein fundus angiography disclosed occlusion of the PCAs; these arteries supply the optic nerve head and cilioretinal arteries, and occlusion of them results in development of arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy and cilioretinal artery occlusion.

8. RACIAL DIFFERENCES IN THE CAUSES OF RETINAL ARTERIAL OCCLUSION

Ahuja et al. (1999), in a retrospective study of consecutive 29 African American and 17 Caucasian patients with a diagnosis of amaurosis fugax, CRAO, BRAO, or intra-arterial retinal plaques, evaluated the causes of retinal artery occlusion. They found that their African American patients had a mean age of 61 years (range, 30 to 77 years) and the Caucasian patients a mean age of 73 years (range, 56 to 94 years) (P=0.003). There was no statistically significant difference between the 2 groups with respect to visible emboli on ophthalmoscopy, or with regard to risk factors for arterial occlusive disease such as arterial hypertension, coronary artery disease, hypercholesterolemia, tobacco use, and history of stroke or transient ischemic attacks. But Caucasian patients had a 41% incidence of high-grade ipsilateral internal carotid artery stenosis, compared with a 3.4% incidence in African American patients (P=0.002).

9. EVALUATION OF PATIENTS WITH ACUTE RETINAL ARTERIAL OCCLUSION

It is generally agreed that all patients with acute retinal arterial occlusion must be evaluated for the source of embolism, which is the commonest cause for its development.

A recent study evaluated the role of carotid Doppler/angiography and Echocardiography in a prospective study 249 CRAO and 190 BRAO patients (Hayreh et al., 2009b). It showed that the plaque in the carotid artery is the usual source of embolism and less commonly the aortic and/or mitral valve.

9.1 CAROTID DOPPLER/ANGIOGRAPHY

In general, when evaluating carotid arteries in these cases, there is a tendency to look only for the stenosis, but it is the presence of plaques in the carotid artery which is of prime interest in such cases; it is of much greater importance than the degree of stenosis in the artery. In this study, 34% had 50% or greater stenosis on the side of CRAO and 71% had plaque(s), and in BRAO that was 30% and 66% respectively (Hayreh et al., 2009b).

9.2 ECHOCARDIOGRAPHY

The transesophageal type of echocardiography is superior to the transthoracic type in detecting cardiac abnormalities. This study showed the following (Hayreh et al., 2009b):

9.2.1

In CRAO, abnormal echocardiograms of source from the mitral valve in 26%, from the aortic valve in 38%, and from both mitral and aortic valves in 36%. The mitral valve lesions comprised 57% calcified valve, 17% mitral valve prolapse, and 26% other types of lesions. The aortic valve lesions were 78% calcified valve and 22% of other types. Patent foramen ovale was detected in 2.4%.

9.2.2

In BRAO, abnormal echocardiograms of an embolic source showed an embolic source in 31% from the mitral valve, 28% from the aortic valve, and 41% from both valves. The mitral valve lesions comprised 70% calcified valve, 4% with mitral valve prolapse, and 26% with other types of lesions. The aortic valve lesions were 68% calcified valve and 32% of other types. Patent foramen ovale was detected in 2%.

9.3 SYSTEMIC EVALUATION

In CRAO as well as BRAO, the prevalence of diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension, ischemic heart disease, and transient ischemic attacks / cerebrovascular accidents is significantly higher than the prevalence of these conditions in the matched U.S. population (all p<0.0001); so also is the prevalence of smoking, compared to the US population (p=0.001) (Hayreh et al., 2009b). Therefore these patients require a complete medical evaluation. Among the laboratory studies, the first step for all patients 50 years and older is to rule out GCA, which is an ophthalmic emergency, by doing instant evaluation of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein, the latter is more reliable. We do not have any definite evidence that hematologic abnormalities play a significant role. In my studies of about 450 patients with various types of retinal artery occlusion, I have found that usually ophthalmologists had already done a large number of hematologic studies to rule out coagulation, thrombotic and other hematologic disorders before referring them to my clinic, only very rarely was any abnormality detected. Therefore, I do not advocate doing all these studies as a routine, unless there is some other strong indication.

9.4 PREVALENT MISCONCEPTIONS IN EVALUATION OF PATIENTS WITH RETINAL ARTERY OCCLUSION

There are several misconceptions about this, as discussed in detail elsewhere (Hayreh, 2005). It is widely assumed that the absence of any abnormality on Doppler evaluation of the carotid artery or echography of the heart rules out those sites as the source of embolism. On the contrary, I have seen some patients with CRAO or emboli in their retinal arteries, without either of these tests showing any abnormality at all. Following are the explanations.

9.4.1 Doppler Evaluation of the Carotid Artery

This is the most common investigation done in retinal artery occlusion patients. I have found that, when evaluating the carotid artery on Doppler, vascular surgeons, neurologists and other physicians are almost invariably interested in the degree of stenosis of the carotid artery because their primary interest is hemodynamic insufficiency and carotid endarterectomy. However, retinal arterial occlusions are almost always due to microembolism, and the major source of microemboli is the plaque(s) which may be present with or without any significant carotid artery stenosis. Thus, absence of significant stenosis of the carotid artery does not necessarily rule out the carotid artery as the source of microembolism. Vascular insufficiency in the eye caused by a significant carotid artery stenosis is seen only rarely, and occurs primarily in ocular ischemic syndrome (Hayreh and Podhajsky, 1982; Mizener et al., 1997). Therefore, from the ophthalmic point of view, when evaluating the results of carotid Doppler study for ocular microembolism, the presence or absence of plaques is usually of much greater importance than the degree of stenosis.

The other reasons why an absence of abnormality on the carotid Doppler does not rules out the carotid artery as the source of the retinal microembolism are: (a) Carotid Doppler evaluates the artery only in the neck and not above and below that, in the skull and the thorax respectively – the source of microembolism may be at those locations. (b) The resolution of Doppler is not always sensitive enough to detect very small plaques which may be enough to produce microembolism to the retina.

9.4.2 Echocardiography

Once again, the absence of any abnormality on this test does not always rule out the heart as the source of microembolism, because its resolution may not be sensitive enough to detect very small valvular or other cardiac lesions. I have also found that when routine transthoracic cardiac echography shows no abnormality, transesophageal echography may reveal abnormalities.

9.4.3 Absence of an embolus

There is another serious misconception that the absence of an evident embolus in the retinal artery means the occlusion was not caused by an embolus. A clinical study on CRAO showed that migration and disappearance of retinal emboli is common (Hayreh and Zimmerman, 2007). Of the 42 eyes which were seen on multiple visits where an embolus was seen at least once, there were 69% in which the embolus was not consistently present at all of the visits. In other words, there was migration of retinal emboli in at least 69% – the actual incidence is likely to be much higher. Thus, the axiom is that if one sees an embolus, then that means it was responsible for the occlusion; but, if one does not see an embolus, that does not rule out that embolism was not responsible for the occlusion, because it might have migrated and disappeared by the time the eye is examined. This issue is further discussed below.

10. CENTRAL RETINAL ARTERY OCCLUSION

Von Graefe (1859) was the first to diagnose CRAO ophthalmoscopically, and he wrote a classical description of the appearance of the fundus which is still well worth reading. The sudden and catastrophic visual loss with CRAO is one of the most important topics in ophthalmology. That makes it an ophthalmic emergency. In spite of this clinical entity having been well known for 150 years, and a voluminous literature on its various aspects, there are still several controversial issues. My critical review of the available literature that has accumulated on the management of CRAO has revealed that the controversy has resulted from several misconceptions on some fundamental scientific aspects of CRAO (Hayreh, 2005). The objective of my studies on CRAO has been to investigate those systematically.

10.1 CLASSIFICATION OF CRAO

CRAO is universally considered as one clinical entity; however, from the point of view of pathogenesis, clinical characteristics and management, recent studies have shown that it actually consists of the following four distinct categories (Hayreh and Zimmerman, 2005, 2007).

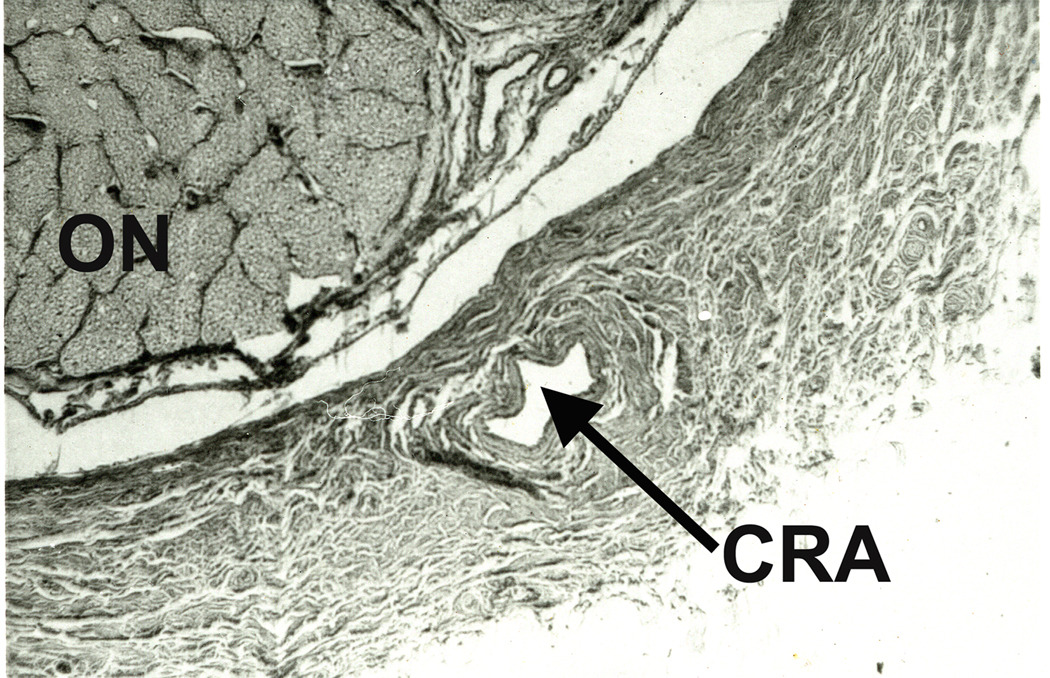

10.1.1 Non-arteritic CRAO

This includes eyes with the classical clinical picture of permanent CRAO with retinal infarction, cherry-red spot (Fig. 7) and absent or poor residual retinal circulation on fluorescein angiography, and no evidence of GCA. This is the most common type. It is usually either embolic or thrombotic in origin - embolism is a far more common cause than thrombosis (Hayreh and Podhajsky, 1982). Very rarely, vasculitis or trauma can cause CRAO. The site of occlusion in CRAO is invariably thought to be at the level of the lamina cribrosa; however, a detailed anatomical study of 100 human central retinal arteries showed that the narrowest lumen of the artery is where it pieces the dura mater of the optic nerve sheath before entering the optic nerve (Fig. 18) (Hayreh 1958). Therefore, in cases of CRAO due to embolism, the chances of an embolus getting impacted at this site are much higher than at any other site in the artery. However, histopathological studies have shown that the lamina cribrosa is the site of occlusion by thrombosis. The site of occlusion is an important factor in determining the amount of residual retinal circulation seen on fluorescein angiography following CRAO (see below).

Figure 18.

A transverse section of the optic nerve showing the central retinal artery (CRA) inferiorly lying within the substance of dural sheath of the optic nerve (ON). (Reproduced from Hayreh 1958.)

10.1.2 Non-arteritic CRAO with cilioretinal artery sparing

This type of non-arteritic CRAO develops only in eyes with a cilioretinal artery. As discussed above, the cilioretinal artery may vary in size from minute (Fig. 7) to one supplying a large part of the retina (Figs. 9,10). The visual outcome (Hayreh and Zimmerman, 2005) and fundus findings (Hayreh and Zimmerman, 2007) in this type of CRAO are different from the classical non-arteritic CRAO. Since the presence and size of a patent cilioretinal artery in permanent non-arteritic CRAO can have a marked influence on the visual outcome and retinal circulation, it is imperative not to lump these eyes together with those having non-arteritic CRAO alone.

Figure 9.

Fundus photograph of the right eye with CRAO and patent cilioretinal artery (Arrow).

10.1.3 Arteritic CRAO

This is due to GCA, which has a special predilection for involvement of the PCAs and only very rarely involves the CRA directly. As discussed above, the CRA, instead of arising directly from the ophthalmic artery, can arise from the ophthalmic artery, not infrequently by a common trunk with the PCA (Fig. 3) (Hayreh 1958). When GCA involves that common trunk, it results in occlusion of both the CRA and PCAs, and consequently development of both arteritic CRAO and arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (Hayreh, 1974a, 1975; Hayreh et al., 1998b). Therefore, in these eyes, the massive visual loss is the result of acute ischemia, not only of the retina but also of the optic nerve head. Clinically, these eyes on ophthalmoscopy have the classical fundus findings of CRAO with or without optic disc edema, but, most importantly, on fluorescein angiography there is evidence of a PCA occlusion in addition to CRAO (Hayreh, 1974a, 1975; Hayreh et al., 1998b). Without fluorescein fundus angiography, the presence of a PCA occlusion and the diagnosis of GCA is usually missed completely, resulting in the tragedy of bilateral blindness that could have been prevented by doing fluorescein angiography in all CRAO patients 50 and older, and early institution of high-dose steroid therapy.

10.1.4 Transient NA-CRAO

This is due to the following 3 reasons:

10.1.4.1 Due to transient impaction of an embolus

An embolus may occlude the CRA temporarily and then dislodge, result in restoration of circulation. The extent of visual loss and clinical features depend upon the duration of the temporary occlusion of the artery by the embolus. The type of embolus which usually causes this is platelet-fibrin embolus.

10.1.4.2 Due to fall of perfusion pressure below the critical level in the retinal vascular bed

In addition to the above causes, our study has revealed that several factors which produce a fall of perfusion pressure below the critical level in the retinal vascular bed can cause CRAO - usually transient CRAO (Hayreh and Zimmerman, 2005). We reported several patients who, in the presence of other predisposing risk factors, developed CRAO because of a fall of perfusion pressure. To understand the mechanism for this, it is essential to know the factors that can cause such a marked. The perfusion pressure in the CRA is equal to the mean blood pressure in the artery minus the intraocular pressure. Therefore, a fall of perfusion pressure can be due to the following two factors:

10.1.4.2.1 Marked fall in mean arterial blood pressure

This can occur for several reasons, including nocturnal arterial hypotension (Fig. 16) (particularly in patients who take blood pressure lowering medicines in the evening or at bedtime) (Hayreh et al., 1994; Hayreh, 1996), severe shock, during hemodialysis, spasm of the CRA, marked stenosis or occlusion of the internal carotid or ophthalmic artery, or ocular ischemia ((Hayreh and Podhajsky, 1982; Mizener et al., 1997).

10.1.4.2.2 A rise of intraocular pressure

Causes may include ocular compression during certain surgical procedures or marked orbital swelling, acute angle closure glaucoma, or neovascular glaucoma in association with ocular ischemia ((Hayreh and Podhajsky, 1982; Mizener et al., 1997).

When the intraocular pressure goes above the mean blood pressure or the blood pressure falls below the intraocular pressure, there is no retinal blood flow. Eyes with already poor perfusion pressure in the CRA are especially vulnerable to CRAO with the fall in perfusion pressure, particularly due to a fall of mean blood pressure, which acts as “the straw that breaks the camel’s back” ((Hayreh and Podhajsky, 1982; Mizener et al., 1997). Since these patients suffer from transient CRAO lasting for several hours, usually during sleep, from marked nocturnal arterial hypotension (Fig. 16), many of them typically give a history of discovering visual loss on waking in the morning or after hemodialysis or surgery. Fluorescein angiography performed during waking hours, when the perfusion pressure has returned to normal, misleadingly reveals normal retinal blood flow in spite of severe visual loss and all the classical signs of CRAO (Fig. 19). I have found that this normal angiographic finding has frequently misled ophthalmologists about the reason for the development of CRAO or even the correct diagnosis.

Figure 19.

Fundus photograph (A) and fluorescein fundus angiogram during retinal arterial phase (B) of an eye with transient CRAO. Fundus photograph shows large number of cotton wool spots, maximum in the macular region. Fluorescein angiogram shows almost normal but slightly sluggish retinal circulation except for absence of filling in the foveal region, and cotton wool spots at places masking the background fluorescence.

10.1.4.3 Due to vasospasm of the CRA

This is a rare cause of transient CRAO. There is evidence to suggest that platelets stick and aggregate on atherosclerotic plaques in the carotid arteries. An experimental study in atherosclerotic monkeys showed that serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine) released by platelet aggregation on atherosclerotic plaques, in the presence of atherosclerotic lesions, triggers transient, severe vasospasm of the CRA, resulting in transient CRAO (Fig. 17) (Hayreh et al., 1997).

Thus, transient CRAO can be produced not only by transient impaction of an embolus in the CRA but also by all these various factors. In transient CRAO, the clinical appearance and visual outcome naturally depend upon the duration of CRAO.

This classification is essential to characterize and differentiate the visual outcomes among these four types of CRAO.

10.2 DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS OF VARIOUS TYPES OF CRAO

A prospective study of 244 patients with CRAO showed the following demographic characteristics in the 4 types of CRAO (Hayreh and Zimmerman, 2005):

10.2.1. Non-arteritic CRAO

This was seen in 67% of cases. Age range in this type was 26.5 to 90.4 (mean ± SD = 67.7 ± 12.3). Of these patients 42% were female, and 5% had it in both eyes. There was a history of amaurosis fugax before development of CRAO in 12%. Visual loss was discovered on waking up in the morning by 35%.

10.2.2 Non-arteritic CRAO with cilioretinal artery sparing

This was seen in 14% of cases. Age range in this type was 39 to 87 (mean ± SD = 67.1 ± 11.6). Of these patients, 46% were female. There was a history of amaurosis fugax before development of CRAO in 20%. Visual loss was discovered on waking up in the morning by 29%.

10.2.3 Arteritic CRAO

This was seen in 4.5% of cases. Age range in this type was 62 to 87 (mean ± SD = 74.4 ± 7.2). Of these patients, 64% were female, and 18% had it in both eyes. There was a history of amaurosis fugax before development of CRAO in 9%. Visual loss was discovered on waking up in the morning by 30%.

10.2.4 Transient CRAO

This was seen in 16% of cases. Age range in this type was 20 to 89 (mean ± SD = 62.7 ± 17.1). Of these patients 54% were female, and 5% had it in both eyes. There was a history of amaurosis fugax before development of CRAO in 13%. Visual loss was discovered on waking up in the morning by 39%.

10.3 SYMPTOMS

Typically, there is a sudden, massive loss of vision in the involved eye. It can occur at any time of the day. As shown above, some discover the visual loss on waking up in the morning. In the latter case, it may be due to embolism, thrombosis or due to transient CRAO from a fall of perfusion pressure during sleep caused by nocturnal arterial hypotension (Fig. 16). The visual loss may be preceded by transient visual obscurations, which may be due to transient migrating embolism or GCA. Simultaneous onset of CRAO in both eyes does not normally occur; it happens rarely, when there is compression of both eyes during a prolonged surgical procedure, or during hemodialysis. Although CRAO is more common in the elderly, it does occur in other age groups, including the young and, rarely, even in infants.

10.4 VISUAL ACUITY

A prospective study of 260 consecutive eyes with CRAO showed that this can vary among different types of CRAO (Hayreh and Zimmerman, 2005). In this study, the time interval between the onset of CRAO and the first visit to the clinic varied greatly - 49% seen within 7 days, 26% in 8 to 30 days, 23% more than one month and in 2% it was unknown. This study showed that when CRAO was subdivided into its four types, the initial visual acuity of the eyes seen within 7 days of onset differed significantly between the four types (p<0.0001) (Hayreh and Zimmerman, 2005). Following was the initial visual acuity in various types of CRAO in that study:

10.4.1 Non-arteritic CRAO

In 171 eyes, overall the initial visual acuity was 20/200 in 3%, 20/400 in 8%, counting fingers in 39%, hand motion in 26%, light perception in 16% and no light perception in 7% of the eyes. Thus, 49% of the eyes had visual acuity of hand motion or worse. However, one eye had visual acuity of 20/30 and another one 20/70. Among 127 eyes seen within 7 days, initial visual acuity was 20/200 – 20/400 in 3% and counting fingers or worse in 93%.

10.4.2 Non-arteritic CRAO with cilioretinal artery sparing

In 35 eyes, the initial visual acuity overall was 20/30 or better in 29%, 20/60–20/100 in 14%, 20/200 in 6%, counting fingers in 20%, hand motion in 26% and light perception in 6%. Visual acuity in this group depends upon the size of the cilioretinal artery – the larger the artery, the better is the visual acuity. Among 20 patients seen within 7 days, visual acuity was 20/40 or better in 20%, 20/50 – 20/100 in 3%, 20/200 – 20/400 in 5% and counting fingers or less in 60%.

10.4.3 Arteritic CRAO

In 13 eyes, all had visual acuity 20/400 or worse, with 54% having no light perception. This type has the worst visual acuity of all types of CRAO. Among 4 patients seen within 7 days, it was 20/200 – 20/400 in 1 and counting fingers or worse in 3 eyes.

10.4.4 Transient non-arteritic CRAO

There were 41 eyes overall in this category, of which the initial visual acuity was 20/20 or better in 27%, 20/25–20/30 in 15%, 20/60–20/70 in 10%, 20/100 in 2%, 20/200 in 7%, 20/400 in 5%, counting fingers in 24% and hand motion in 10%. This type has much better visual acuity than other types of CRAO. Among 29 patients seen within 7 days, initial visual acuity was 20/40 or better in 38%, 20/50–20/100 in 7%, 20/200 – 20/400 in 17% and counting fingers or worse in 38%.

This shows that, of the eyes seen within 7 days of onset, initial visual acuity differed significantly among the 4 CRAO types (p<0.0001), 38% of transient nonarteritic CRAO patients having counting fingers or worse compared to 93% of those with nonarteritic CRAO. There is a widespread impression that all eyes with CRAO initially have very poor visual acuity, e.g., hand motion or worse. As is evident from the above, an eye with CRAO may, rarely, present with visual acuity as good as 20/30 or better. This has often resulted in the diagnosis of CRAO being missed because of the conventional thinking. In the literature, visual acuity has unfortunately always been lumped together as one group; that does not provide valid information.

10.5 VISUAL FIELDS DEFECTS

Visual acuity essentially represents the function of the foveal region and not of the rest of the retina, while visual fields plotted with a Goldmann perimeter provide information about the entire retina and its function – after all, CRAO involves the entire retina. Unfortunately, there has been little information on the visual field defects in CRAO in the literature, except for one recent prospective study of 145 eyes (Hayreh and Zimmerman, 2005). Visual field defects in that study were divided into two categories: (i) scotomas seen in the central 30°, and (ii) general visual field defects.

10.5.1 Scotomas in the central 30°

Central scotoma was the most common type of all types of CRAO; its pathogenesis is discussed below. Paracentral scotoma was the next most common. There was no scotoma in 37% of the eyes with transient NA-CRAO.

10.5.2 General visual field defects

Eyes with nonarteritic CRAO with cilioretinal artery sparing showed an intact central island field corresponding to the area of the retina supplied by the patent cilioretinal artery. Generalized constriction of the peripheral fields was more common than other types of field defect in eyes with nonarteritic CRAO with cilioretinal artery sparing (32%) and also in those with transient nonarteritic CRAO (17%). By contrast, 52% of nonarteritic CRAO eyes had only a peripheral island residual field, most frequently located in the temporal region (42%). Most interestingly, the peripheral visual field was normal in 63% of the eyes with transient nonarteritic CRAO and even in 22% with nonarteritic CRAO; the clinical importance of intact peripheral visual field is discussed below.

10.6 NATURAL HISTORY OF VISUAL OUTCOME IN CRAO

Information on the natural history of a disease is vital, so that claims of “success” for various advocated treatments can be measured against the natural history. A recent large, planned, systematic study on the natural history of visual outcome in CRAO has given useful information (Hayreh and Zimmerman, 2005). This study had 168 eyes with a follow-up of 1.1 years (interquartile range: 0.2–3.5 years). It revealed the following:

10.6.1 Visual acuity

This study revealed that visual acuity improvement essentially occurs during the first 7 days, with minimal chance of any appreciable improvement thereafter. Also, the incidence of visual acuity improvement during the first 7 days differed significantly (p<0.001) among the 4 types of CRAO. Of the eyes that presented with counting fingers or worse initial visual acuity, 37% of those seen within 7 days of onset showed an improvement in visual acuity. In contrast, only 5% of those seen 8 to 30 days after onset and 9% of those seen more than 30 days after onset had any improvement in visual acuity (p<0.0001). Among the patients seen within 7 days with initial visual acuity of counting finger or worse, visual acuity improved, remained stable or deteriorated in nonarteritic CRAO in 22%, 66% and 12% respectively; in nonarteritic CRAO with cilioretinal artery sparing in 67%, 33% and none respectively; and in transient nonarteritic CRAO in 82%, 18% and none respectively. This shows that the popular concept of the dismal outlook in CRAO is not correct, and that it varies markedly with the type of CRAO. It is possible that many of the claims of visual acuity improvement following various treatments may be no more than the natural history of the disease.

10.6.2 Visual fields

In all types of CRAO, both central and peripheral visual fields showed improvement. In eyes with a follow-up of at least 30 days, the study found that in all types of CRAO, both central and peripheral visual fields showed improvement in a variable number of eyes.

10.6.2.1 Central visual fields

These improved or remained stable in nonarteritic CRAO in 21% and 73% respectively; in nonarteritic CRAO with cilioretinal artery sparing, in 25% and 69% respectively; and in transient nonarteritic CRAO in 39% and 30% respectively.

10.6.2.2 Peripheral visual fields

These improved, remained stable or deteriorated in nonarteritic CRAO in 39% 39% and 15% respectively; in nonarteritic CRAO with cilioretinal artery sparing in 19%, 75% and 6% respectively; and in transient nonarteritic CRAO in 39%,30% and none respectively.

Most importantly, in transient nonarteritic CRAO with field defects initially, the central and peripheral visual fields recovered to normal in 26% and 30% respectively.

Thus, this natural history study (Hayreh and Zimmerman, 2005) showed:

Contrary to the prevalent impression, spontaneous improvement in both visual acuity and visual fields does occur in the first few days after onset of CRAO, and the extent of improvement depends very much upon the type of CRAO. It is worst in arteritic CRAO.

Visual acuity improvement essentially occurs during the first 7 days, and differs significantly (p<0.001) among the 4 types of CRAO. There is minimal chance of any appreciable visual acuity improvement after 7 days.

It is essential to classify CRAO into 4 types to evaluate the visual outcome realistically – this has never been done in previous studies.

10.6.2.3 Pathogenesis of central scotoma in CRAO

There is an common impression that CRAO causes generalized loss of vision. However, it is not widely realized that CRAO can produce only central scotoma (the most common visual field defect in CRAO) with fairly normal peripheral visual fields (Fig. 20-C). The mechanism of selective development of central scotoma without any peripheral visual field defect in CRAO is as follows. It is well known that the macular region has more than one layer of retinal ganglion cells (unlike the rest of the retina), and it is the thickest part of the retina – maximal thickness being close to the foveola. Experimental (Hayreh and Weingeist, 1980a; Hayreh et al., 2004b) and clinical (Hayreh, 1976; Hayreh and Zimmerman, 2005) CRAO studies have shown that the ischemic retinal whitish opacity and swelling of CRAO is essentially located in the macular region – maximal in the perifoveolar region (Figs. 7,20-A). If there is restoration of circulation in the CRA, the retinal capillaries in the central, thickest part of the macular region do not re-fill (Fig.20-B) because of compression by the surrounding swollen superficial retinal tissue, resulting in the “no re-flow phenomenon” (Hayreh and Weingeist, 1980b), and consequently in permanent ganglion cell death in the non-perfused retina; the area of central retinal capillary non-filling may vary from eye to eye, depending upon the severity of retinal swelling in the macula region. This results in the variable size of the permanent central scotoma. Oxygen supply and nutrition from the choroidal vascular bed to the thinner peripheral retina help in its much longer survival, and the maintenance of peripheral visual fields.

Figure 20.

Fundus photograph (A) and fluorescein angiogram (B) of right eye at initial visit in an eye with transient non-arteritic CRAO 10 days earlier.

A. Fundus photograph shows cherry-red spot, retinal opacity of posterior fundus – most marked in the macular region, and a small area of normal retina temporal to the optic disc corresponding to a patent cilioretinal retinal artery.

B. Angiogram during the retinal arteriovenous phase shows normal filling of the retinal vascular bed with complete absence of filling in the macular region, corresponding to the area with most marked retinal swelling.

C. Visual fields of a left eye, plotted with a Goldmann perimeter 2 months after the development of transient non-arteritic CRAO. It shows an absolute central scotoma, and slightly constricted peripheral visual field with I-4e but normal with V-4e, and visual acuity of 20/200. (Reproduced from Hayreh and Zimmerman 2005.)

Patients with a central scotoma often learn with experience to fixate eccentrically, resulting in an apparent visual acuity improvement that does not represent a genuine improvement in the retinal function and may erroneously be attributed to a therapy. Natural history studies of various types of ocular vascular occlusive disorders have shown that for genuine visual acuity improvement, there must be simultaneous improvement in both the central scotoma and visual acuity (Hayreh et al., 2002; Hayreh and Zimmerman, 2005; Hayreh et al., 2011).

10.6.2.4 Role of Visual Field Findings in Judging Functional Visual Disability in CRAO

This has important clinical implications. It is well established that the constant tracking provided by the peripheral visual fields is essential for sensory input in our day-to-day activity, for example for driving and “navigating” generally (Hayreh, 2005). In view of that, to assess the visual function disability produced by CRAO, it is important to realize that persisting peripheral fields even in the presence of central scotoma (see above) do provide the patient fairly useful functional vision for day to day living, in spite of the fact that he/she cannot see well enough to read, write, drive or do any fine work with that eye. This is particularly important if the patient loses the fellow eye. Unfortunately, this important fact is not fully realized by much of the ophthalmic community.

10.6.3 Factors Influencing the Visual Outcome in CRAO

This is an important subject, because an in-depth understanding of the fundamental facts behind the factors that play a crucial role in determining the visual outcome in CRAO is essential. Experimental (Hayreh, 1971; Hayreh et al., 1980; Hayreh and Weingeist, 1980a, b; Hayreh et al., 2004b; Kwon et al., 2005) and clinical (Hayreh, 1971, 1975, 1976; (Hayreh and Podhajsky, 1982; Mizener et al., 1997) studies on CRAO have provided important information on these factors. The factors influencing the visual outcome in CRAO are discussed at length elsewhere (Hayreh and Zimmerman, 2005) and following is a brief summary.

10.6.3.1 Duration of CRAO

This is by far the most important factor. As discussed above, CRAO lasting for 97 minutes does not produce any detectable visual loss; but after that there is a progressive loss, and when ischemia lasts for 240 minutes or more that results in massive, irreversible retinal damage (Hayreh and Jonas, 2000; Hayreh et al., 2004b). Also, studies have shown that the longer the ischemia, the longer the time-lag before the start of any visual improvement (Hayreh and Weingeist, 1980b; Hayreh et al., 2004b).

10.6.3.2 Residual retinal circulation in CRAO

This has caused a good deal of controversy as to whether there is complete or incomplete CRAO. This is discussed below, in the section dealing with fluorescein fundus angiography soon after the onset of CRAO.

10.6.3.3 Site of occlusion in the central retinal artery

It is generally believed that the site of occlusion in CRAO is at the level of the lamina cribrosa (as revealed by histopathologic studies of enucleated eyes). As discussed above, the narrowest lumen of the artery is where it pierces the dura mater of the optic nerve sheath (Fig.18) (Hayreh 1958). Therefore, in cases of CRAO due to embolism, the chances of an embolus getting impacted at this site are much higher than at any other site in the artery. In contrast to that, the site of occlusion in thrombosis of the CRA is at the lamina cribrosa, as shown by histopathological studies. The site of occlusion is an important factor in determining the amount of residual retinal circulation in CRAO, as discussed below.

10.6.3.4 Presence and area of supply by a patent cilioretinal artery