Abstract

Although India is in the grip of HIV/AIDS epidemic, not much information is available on clinico-epidemiological and socio-behavioral aspects of people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA). This study analyzed these features using standard methodologies in 82 HIV sero-positives, AIDS patients attending ART clinic of three major government hospitals of Delhi. Majority of the patients (73%) were found to be young (<40 years) and married (79%). As high as 91.5% came from low socio-economic class and more than 95% acquired HIV transmission through heterosexual routes. A large proportion (63%) of these patients reported an extremely high level of anxiety, moderate level of stress and a borderline level of clinical depression. While most of the patients (72%) were well-adjusted with the ART, the rest of the patients reported difference in making adjustment with the treatment schedules. The study suggests that counseling and supportive therapy could play a pivotal role in controlling anxiety, stress, depression and rehabilitating people with HIV/AIDS.

Keywords: Antiretroviral treatment, commercial sex workers, counseling, people living with HIV/AIDS, willingness to participate

INTRODUCTION

As the HIV/AIDS pandemic progresses, HIV sero-positive individuals contend with devastating illness. Physical illnesses,[1] particularly those which are life threatening, are associated with socio-psychological counter effects. Although physical symptoms might be similar all over the world, the psychological impact on the affected person will depend on the socio-cultural factors prevalent in that region. Studies have reported a high prevalence of psychiatric symptoms in patients living with HIV/AIDS.[2] Profound psychological complications of AIDS leads to a variety of neuropsychiatric impairments such as dementia, delirium, fear, anxiety, depression, adjustment problems, restlessness, and various emotional reactions. Neuropsychiatric illness due to HIV infection complicate the psycho-social issues related to AIDS[3–5] and are similar to those of life-threatening illness like cancer.[6]

By the end of 2006, there were approximately 39.5 million individuals infected with HIV world-wide.[7] India has more than 5.3 million people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHAs), the world's highest number of infections after South Africa, thus representing a high public health burden. Almost one-fourth of India's AIDS cases are among children and young people below 25 years of age. According to National AIDS Control Organization (NACO), 68 new cases of HIV occur every hour[8] and the epidemic has been spreading from high to low risk populations.

Beside HIV-1, HIV-2 infection was also detected in India as early as in 1991[9] and this infection has been reported from western,[10] northern, and southern India.[11] HIV-2 is transmitted in the same way as HIV-1. Although there are structural dissimilarity in amino acid of the coat proteins of the two viruses,[12] both HIV-1 and HIV-2 are transmitted in the way and cause same range of diseases. However, the prevalence of HIV-2 worldwide is still very low as compared to HIV-1.[13]

In India, transmission of HIV is found to be mainly heterosexual that is through unprotected sexual intercourse except in the north-eastern states where the major route is by injection.[14,15] In the sex workers use of condom was consistently found protective and women with more than 50% use had a significantly lower prevalence of HIV.[16] In a study on adolescents sexuality Shalani[17] has emphasized that adolescents in low income communities are at risk of STDs and HIV owing to lack of understanding of sex and sexuality, unprotected sexual activity, and presence of non-commercial contact of sex. AIDS education program in India are being broadened to include aspects on sexuality and gender roles and relationships. Keeping this background in view.

Aim

The present study has been designed to assess the clinico-epidemiological and socio-behavioral aspects of people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHAs) in India.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

This study was carried out among HIV/AIDS positive individuals including commercial sex workers (CSWs) attending the out-patients department at the antiretroviral treatment (ART) clinic of the HIV testing centers at Lok Nayak, Safdarjung, and All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) hospitals, New Delhi. All the patients, male and female in the age range of 20-65 years and willing to participate, were included in this study. The exclusion criteria were age less than 20 years, CD4 counts more than 500 or less than 50/μl, pregnant or lactating women, and those refused to give informed consent.

Procedure

Prior to the onset of the study, the study protocols were extensively discussed and reviewed in the Scientific Advisory Committee and Institutional Ethics Committee of the Institute. All the subjects (male and female) identified as HIV+ve in above three hospital clinics during the period from July 2006 to January 2007 were recruited for the study and the follow-up was made every 4 weeks after and clinical assessment was made. The total cases were 82 HIV sero-positive/AIDS patients. Written as well as informed consent was obtained for each patient at the time of recruitment.

At the time of enrolment and at each visit of the patient 5 ml of peripheral venous blood was collected from each patient. Serum was separated and stored at –20°C until analysis. A complete physical examination including body weight, etc was performed by a clinician, along with the routine tests for hemoglobin, liver functions, X-ray chest and CD4 and CD8 counts and its ratio. The HIV status was analyzed by ELISA with further confirmation by western blot. CD4/CD8 counts were measured by a flow-cytometer.

Clinico-epidemiological evaluation

Clinico-epidemiological and socio-demographic profiles were completed by interviewing each participant separately in a well-structured and pre-tested questionnaire which were filled in by the epidemiologist during the study at the time of recruitment of the patients. The socio-economic status was elicited by interview and assessed using the Kuppuswamy scale.[18] Information was collected regarding the date of birth, gender, religion, education, employment status, income as well as social aspects like conjugal relationship, pre-marital and extra marital relationships, communication between spouses and other risky behavior including non-use/irregular use of condom, and the nature of high-risk behavior.

Psychological evaluation

The main component of psychological questionnaire includes psychological morbidity like reluctant to medication, guilt feeling, adjustment process, etc. Psycho-social and behavioral evaluations were also measured by the questionnaire. Participants completed three sets of measures in a single assessment session: (1) assessment through the questionnaires; (2) an interview to elicit information concerning health status, current treatments for HIV/AIDS, and treatment adherence; and (3) self-administered measures of emotional distress, perceived social support, and attitude toward primary care providers. Anxiety, stress, and depression were measured by standard psychological tests.[19,20,21,22]

Anxiety

Anxiety was measured by a comprehensive Anxiety Test (CA-Test)[19]. The test has 90 items relating to the “Covert” and “Overt” symptoms of the anxiety of the “Yes” and “NO” type of response. The reliability coefficient by split-half method (Gutman Formula) of the test has been found to be 0.94 and the coefficient of validity was determined by computing the correlation between scores of the test and with Spielberger's state and Trait Anxiety scale.[20] This test was adopted and standardized for Indian women.

Stress

Stress was measured by “Personal Stress Inventory.”[21] It has 35 items. Every item marked as “Seldom” was assigned a score of 1, “Sometimes” was given a score of 2, and “Frequently” a score of 3. Higher the score, the higher was the magnitude of personal stress. Ten to twelve minutes are sufficient for completion of the inventory. The test-retest reliability was found to be 0.792 and possessed a sufficient degree of content validity.

Depression

Symptoms of depression were measured by “Beck's Depression Inventory (BDI)”[22] which was adopted in a local language using 21 items self-report rating inventory measuring characteristic attitudes and symptoms of depression. Scores > 10 are considered positive for depression. The BDI has been used in numerous studies with general and cancer populations[23,24] with satisfactory reliability ranges from 0.73 to 0.92[25] and validity range from 0.62 to 0.66.[26]

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using essentially the chi-square test in order to know the significant difference between age groups for various psychological measures and for treatment responses of male and female participants receiving ART.

RESULTS

Personal, social, economic and demographic observations

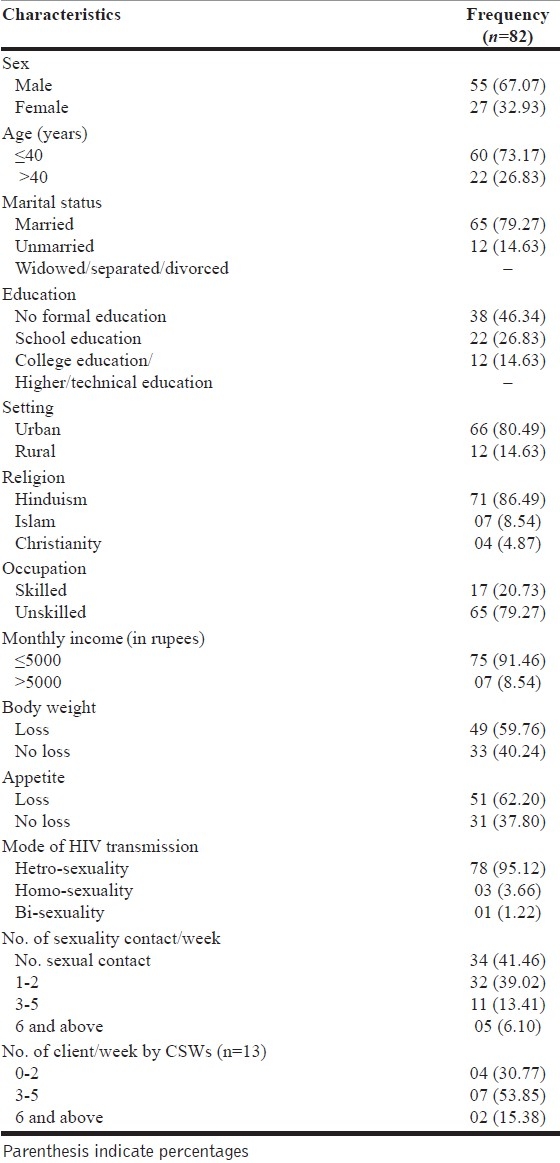

Demographic and socio-economic information of subjects belonging to PLWHA are given in Table 1. A significant proportion (73%) were young ( < 40 years), married (79%) and large majority were unskilled works (79%). 67.1% of the participants were male, while 32.9% were female, and majority of them were from low socio-economic status (91.5%). 86.58% were Hindus and 46.34% illiterate. In most of the cases (95.12%), the modes of HIV transmission was through heterosexual promiscuity. After getting HIV infection, majority of the patients (41.5%) did not have any sexual contact with their partner or had any extra marital relationships. Unfortunately, all the infected CSWs continued to entertain their clients with about 68% entertaining >3 clients per week [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic and behavioral characteristics of the participants

Clinical presentation

HIV-I and II were confirmed by the ELISA test followed by western blotting. At the recruitment time when patients came to the hospital and presented their case, a detailed clinical investigation was performed by a clinician. It is found that the total lymphocyte counts in majority (84.1%) of the patients were low (700-3500/mm3) and the mean hemoglobin level was 10.0 g/dl (11.2g/dl for men and 8.6 g/dl for women) was also less in 82.3% cases. A sputum test was also performed for T.B. patients and was confirmed by X-ray chest and acid-fast bacilli (AFB) in sputum or plural fluid, was found positive in 14.6% cases. Loss of appetite (62.19%) followed by loss of body weight (59.8%) with the mean body weight was 51 kg (63 kg for men and 52 kg for women) were also observed among PLWHA cases. In most of (71%) the patients, psychological fatigue was also observed.

Socio-behavioral analysis

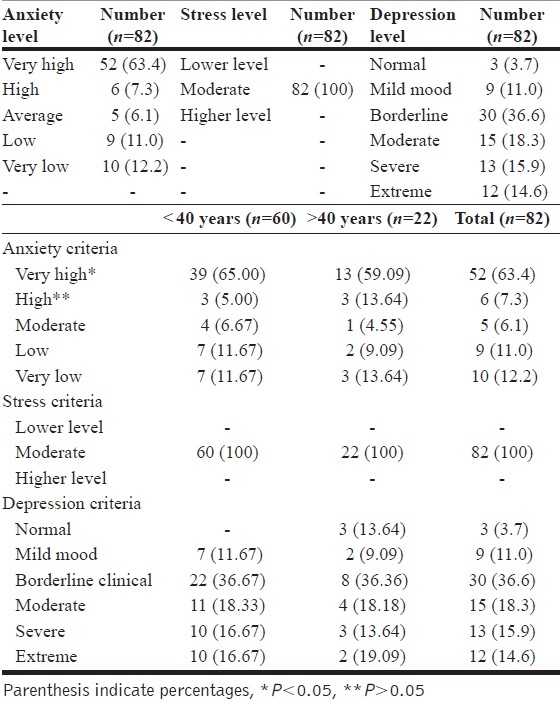

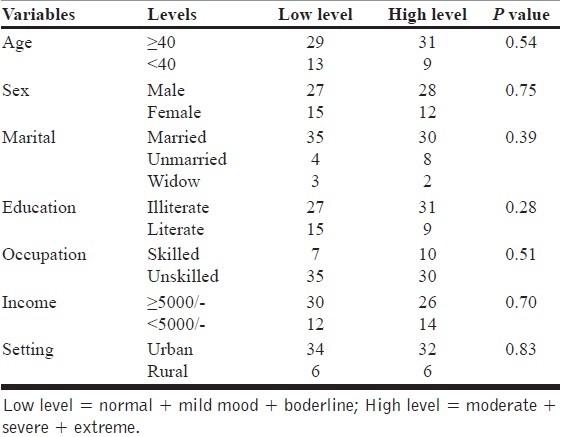

In the present study, we found that most of the patients suffered from psychological morbidity [Table 2]. The three important behavioral disorders, namely anxiety, stress, and depression were further analyzed on the basis of anxiety/depression scale which gave psychological dimension of quality of life of these cases [Table 2]. The findings suggest that majority of the cases (63.4%) reported very high level of anxiety and were anxious about their future aspects of life especially about the disease with moderate level of stressful life condition and borderline level of clinical depression. Anxiety, stress, and depression levels were not affected by the age. During the interview with the patients and after the administration of the psychological tests, individual-based supportive counseling was given, that includes educational awareness of the disease, helpful attitude, healing touch, support system, and guidance regarding secondary-care, e.g. a healthy diet, clean water, psychological care provided by health professional coping strategies and about rehabilitation and treatment [Tables 2–4].

Table 2.

Psychological measures

Table 4.

Levels of depression with demographic parameters

Table 3.

Levels of anxiety with demographic parameters

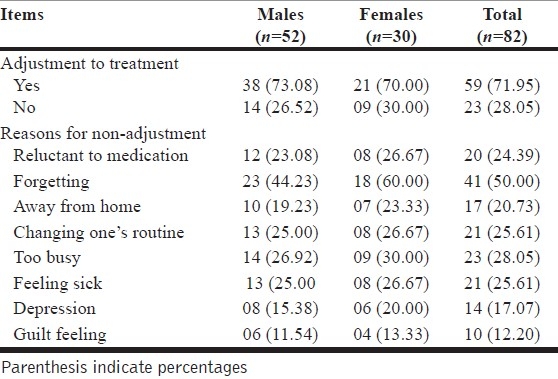

Table 5 shows adjustment of patients on ART: 72% of patients were well adjusted with the ART. There was no difference between males and females in adjusting to therapy. Rest (28%) had difficulties in making adjustment with treatment schedules. Most of the non-adjustment was due to indifference to therapy. 24% were reluctant to take medicines, 28% of them were too busy to keep to timely treatment schedules, 25.6% reported side effects of the drug (too toxic to abandon), and 50% were forgetful to late bed time/day time medicines. A small proportion (depression 17%; guilt feelings 12%) was due to illness and lack of motivation.

Table 5.

Distribution of responses of participant undertaking ART

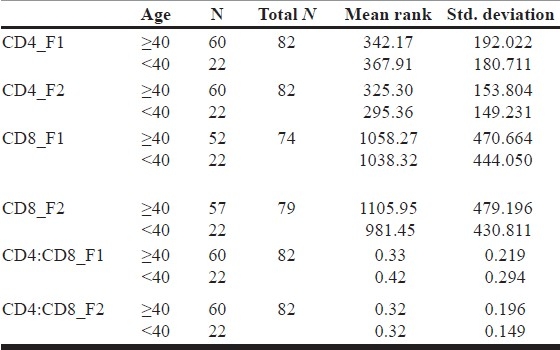

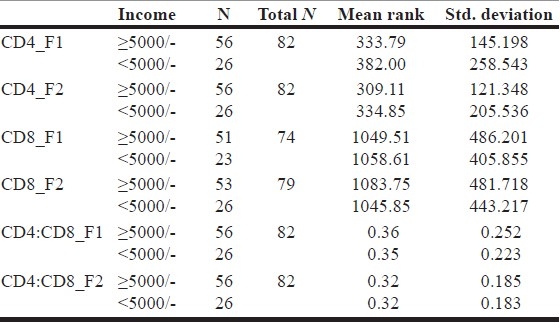

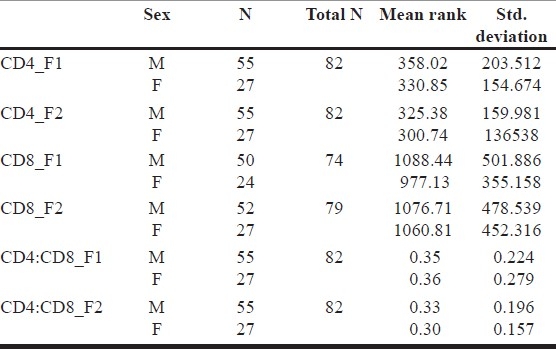

At recruitment stage, mean (± SD) scores of total CD4 and CD8 cell counts, and the mean CD4 CD8 ratio were calculated and the estimated mean CD4 counts were 349.07±188.29; mean CD8 were 1052.34±459.96 and the CD4/CD8 ratio was 0.36±0.24, respectively [Tables 6–8].

Table 6.

Clinical presentation (age wise)

Table 8.

Clinical presentation (income wise)

Table 7.

Clinical presentation (sex wise)

DISCUSSION

Demographically our study population was predominately of young patients (73% younger than 40 years) and without any formal education (46%). This calls for intensive session with patients so that they can understand implications of their illness and significance of timely medicines. Majority of these patients were unskilled (79%), with more than 90% drawing monthly income < Rs.5000/- (approx. US$ 112.00). Patients of low socio-economic class are likely to miss treatment doses as reported by Kalichman.[27,28] 80% of these patients come from urban areas. This proportion supports the view that the current Indian epidemic is more intense in urban areas and is only beginning to enter in villages.[29]

The finding indicates that 79% patients were married and disturbing in two aspects. First, that the infected patients will infect their married partners and further to their off springs. Secondly, the strong Indian family institution is showing sign of crumbling which may contribute further to this epidemic.

A large proportion of the study population was symptomatic with about 60% presenting with body weight loss and 62% with loss of appetite. This clinical presentation is supported by a rather low mean CD4/CD8 ratio. HIV destroys a person's immune system and renders the host defenseless. A measurement of CD4 T-cells is used as a marker for the extent of immune suppression. Cell counts <200 cells/μL are considered a risk for opportunistic infections (i.e., pneumocystis carnie pneumonia). The lower the CD4 T-cell count, the higher the risk of other opportunistic infections. A CD4 T-cell count of <200 cell/μL or the presence of an opportunistic infection gives the diagnosis of AIDS (Yeni et al.,[30] 2002).

Modes of HIV transmission secure to be predominantly due to heterosexual activities (95%). This is the most common mode of transmission of HIV in India and other Asian countries.[14,31]

The disturbing feature was that after the confirmation of diagnosis 59% were continued with their sexual activities within and without family, with about 20% having had three or more contacts per week. 41%, however, stopped having any sexual activities. Likewise, count-percent CSWs continued with their sexual activities, with about 69% entertaining three or more clients per week. The finding also suggests, however, that the sex worker who have unprotected sex with seroconcordant partners place themselves at risk for contracting secondary infection that may accelerate their HIV disease[32,33] Thus, it is an important area where HIV+ve individuals need to be counseled for protective sex. Innovative counseling techniques need to evolve to bring about the behavioral changes for these patients, most of whom are illiterate young, and belonging to low socio-economic class.

Psychological analysis revealed a very high proportion (100%) of stress of moderate level, a very high level (63%) of anxiety,[34] and about 30% had severe to extreme degree of depression.[35–37] This may be due to the conformation of their diagnosis of HIV infection and/or AIDS coupled with effect of their illness and toxicity of drugs (Blank and et al.,[38] 2002; Vitiello et al.[39] 2003 and Ickovics and Meisler 1997).[40]

A significant finding of this study was that substantial number of patients (28%) could not adjust to the antiretroviral treatment, which is so essential for their own well-being as well as to bring down the level of infectivity.[41] A concerted counseling is required for these patients so that they can continue with the prescribed medication. Due to low level of education and poor life circumstances and associated psychological reaction high anxiety and depression,[42–46] they run the risk of discontinuing their medication.[47] A good counseling, supportive psychotherapy, and surveillance and management of toxic reactions will go a long way to help patients to continue with treatment.

CONCLUSION

People living with HIV/AIDS need up-to-date information on a range of issues associated with the disease severity and antiretroviral treatment. It is important to help them understand disease progression to be able to seek early treatment.

Acknowledgments

Financial help from NACO, New Delhi, and infrastructural facility provided by the LNJP and GB Pant Hospital are gratefully acknowledged. Authors are also thankful to all patients and Technical/Nursing staff for their cooperation and help in carrying out this study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: NACO, Govt. of India, New Delhi

Conflict of Interest: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tindell B, Cooper DA. Primary HIV Infection: Host responses and intervention strategies. AIDS. 1991;5:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacob KS, Eapen V, John JK, John TJ. Psychiatric morbidity in HIV infected individuals. Indian J Med Res. 1991;93:62–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fenton TW. AIDS-related psychiatric disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;151:579–88. doi: 10.1192/bjp.151.5.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chitill HN, Dilley JW. In: AIDS and the nervous system. Rossenblum ML, editor. New York: Raven Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldmier D, Granville, Grossman K. In: Recent advances in clinical Psychiatry. 6th ed. Granville-Grossman K, editor. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Faulstich ME. Psychiatric aspects of AIDS. Am J Psychiatry. 1987;144:551–6. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.5.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suhadev M, Nyamathi AM, Swaminathan S, Venkatesan P, Raja Sakthivel M, Shenbagavalli R, et al. A pilot study on willingness to participate in future preventive HIV vaccine trials. Indian J Med Res. 2006;124:631–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Estimation of HIV infections among adult populations. New Delhi: National AIDS Control Organization, Govt. of India; 2004. HIV/AIDS Indian Scenario. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rübsamen-Waigmann H, Briesen HV, Maniar JK, Rao PK, Scholz C, Pfützner A. Spread of HIV-2 in India. Lancet. 1991;337:550–1. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91333-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kulkarni S, Thakur M, Rodrigues J, Banerjee K. HIV-2 antibodies in serum samples from Maharashtra state, India. Indian J Med Res. 1992;95:213–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Babu PG, Saraswathi NK, Devapriya F, John TJ. The detection of HIV-2 infection in Southern India. Indian J Med Res. 1993;97:49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barter G, Barter S, Gassard B. HIV and AIDS. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1993. pp. 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solomon S, Kumarasamy N, Ganesh AK, Amalraj RE. Prevalence and risk factors of HIV-1 and HIV-2 infection in urban and rural areas in Tamilnadu. Int J STD AIDS. 1998;9:98–103. doi: 10.1258/0956462981921756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.HIV infection-current status and future research plans. Indian Council of Medical Research Bulletin; 1991. pp. 21–128. [Google Scholar]

- 15.UNAIDS/WHO. India: Epidemiological fact sheet on HIV/AIDS and sexually transmitted infections 2004 update. [last accessed on 2005 Dec15]. Available from: http://www.unaids/org/en/geographical+area/by+country/india.asp .

- 16.Jain MK, John TJ, Keusch GT. A review of human immunodeficiency virus infection in India. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1994;7:1185–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bharat S. Geneva: 1998. Adolescent sexuality and vulnerability to HIV infection in Mumbai; p. 246. Abstract No. 14321, conference proceedings 12th World Conference, Jun 28- Jul 3. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuppuswamy B. Manual of Socio-economic status scale. New Delhi: Manasayan; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharma H, Bharadwaj R, Bhargawa M. Comprehensive Anxiety Test (CA-Test) Agra, India: National Psychological Corporation; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spielberger CD. Anxiety as an emotional state. In: Spielberger CD, editor. Current Trends in Theory and Research. New York: Academic Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh AK, Singh A. Personal Stress Inventory. Agra, India: National Psychological Corporation; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–71. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Serpil V, Aylin P. Psychopathology and body image in cosmetic surgery patients. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2001;25:474–8. doi: 10.1007/s00266-001-0009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brooks SJ, Kutcher S. Diagnosis and measurement of adolescent depression: a review of commonly utilized instruments. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2001;11:341–76. doi: 10.1089/104454601317261546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beck AT, Steer RA, Garbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. 1988;8:77–100. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Foa EB, Riggs DS, Dancu CV, Rothbaum BO. Reliability and validity of a brief instrument for assessing post traumatic stress disorder. J Traumatic Stress. 1993;6:459–73. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kalichman SC, Ramachandran BA, Catz S. Adherence to combination antiretroviral therapies in HIV patients of low health literacy. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14:267–73. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00334.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kalichman SC. 2nd ed. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 1998. Understanding AIDS: Advance in Research and Treatment. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh N, Squier C, Sivek M, Wagener M, Nguyen M, Yu VL. Determinants of compliance with antiretroviral therapy in patients with human immunodeficiency virus: Prospective assessment with implications for enhancing compliance. AIDS Care. 1996;8:261–9. doi: 10.1080/09540129650125696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yeni PG, Hammer SM, Carpenter CC, Cooper DA, Fischl MA, Gatell JM, et al. Antiretroviral treatment for adult HIV infection in 2002: updated recommendations of the International AIDS Society-USA Panel. JAMA. 2002;288:222–35. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.2.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.UNAIDS. Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Balzquez MV, Madueno JA, Jurado R, Fernandez AN, Munoz E. Human herpes virus-6 and the course of human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1995;9:389–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fleming DT, Wasserheit JN. From epidemiological synergy to public health policy and practice: the contribution of other sexually transmitted diseases to sexual transmission of HIV infection. Sex Transm Infect. 1999;75:3–17. doi: 10.1136/sti.75.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsao JC, Dobalian A, Naliboff BD. Panic disorder and pain in a national sample of persons living with HIV. Pain. 2004;109:172–180. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ferrando SJ, Wapenyi K. Psychopharmacological treatment of patients with HIV and AIDS. Psychiatr Q. 2002;73:33–49. doi: 10.1023/a:1012840717735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goldenberg D, Boyle B. HIV and Psychiatry: Part 1. AIDS Read. 2000;10:11–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goldenberg D, Boyle B. Psychiatry and HIV: Part 2. AIDS Read. 2000;10:201–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blank MB, Mandell DS, Aiken L, Hadley TR. Co-occurrence of HIV and serious mental illness among Medicaid recipients. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53:868–73. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.7.868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vitiello B, Burnam MA, Bing EG, Beckman R, Shapiro MF. Use of psychotropic medications among HIV-infected patients in the United States. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:547–54. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.3.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ickovics JR, Meisler AW. Adherence in AIDS clinical trials: A framework for clinical research and clinical care. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:385–91. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00041-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hecht FM. Presented at the meeting of clinical care of the AIDS patients. San Francisco, California: 1997. Adherence to HIV Treatment. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lyketsos CG, Hanson A, Fishman M, McHugh PR, Treisman GJ. Screening for psychiatric morbidity in a medical outpatient clinic for HIV infection: The need for a psychiatric presence. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1994;24:103–13. doi: 10.2190/URTC-AQVJ-N9KG-0RL4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Komiti A, Judd F, Grech P, Mijch A, Hoy J, Williams B, et al. Depression in people living with HIV/AIDS attending primary care and outpatient clinics. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2003;37:70–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2003.01118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McDermott BE, Sautter FJ, Jr, Winstead DK, Quirk T. Diagnosis, health beliefs and risk of HIV infection in psychiatric patients. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1994;45:580–5. doi: 10.1176/ps.45.6.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Farinpour R, Miller EN, Satz P, Selnes OA, Cohen BA, Becker JT, et al. Psychosocial risk factors of HIV morbidity: Findings from the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS) J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2003;25:654–70. doi: 10.1076/jcen.25.5.654.14577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cook JA, Grey D, Burke J, Cohen MH, Gurtman AC, Richardson JL, et al. Depressive symptoms and AIDS-related among a multisite cohort of HIV-positive women. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:1133–40. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aversa SL, Kimberlin C. Psychosocial aspects of antiretroviral medication use among HIV patients. Patient Educ Couns. 1996;29:207–19. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(96)00910-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]