Abstract

The present investigation was aimed at studying the efficacy of cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) in reducing the symptoms of stuttering and dysfunctional cognitions and in enhancing assertiveness and quality of life in clients with stuttering. Five clients with stuttering who met the inclusion criteria (male clients with diagnosis of stuttering) and exclusion criteria (clients with brian damage), substance abuse or mental retardation were enrolled for the study. A single-case design was adopted. The pre-, mid- and post-assessment were carried out using Stuttering Severity Scale (SSI), Perception of Stuttering Inventory (PSI), Beck's Anxiety Inventory (BAI), Dysfunctional Attitude (DAS), Fear of Negative Evaluation (FNE), Assertiveness Scale (AS), Rosenberg's Self-Esteem Scale (RSES), and World Health Organization - Quality of Life Scale (WHO-QOL). Five clients received cognitive behavioral intervention comprising of psycho-education, relaxation, deep breathing, humming, prolongation, cognitive restructuring, problem-solving strategies and assertiveness. At post-treatment assessment, there was improvement. The findings of the study are discussed in the light of available research work, implications, limitations of the study and suggestions for future research.

Keywords: Cognitive behavioral therapy, quality of life, stuttering

INTRODUCTION

According to ICD-10,[1] stuttering is defined as speech that is characterized by frequent repetition or prolongation of sounds or syllables or words, or by frequent hesitation or pauses that disrupt the rhythmic flow of speech. Globally, the prevalence of childhood stuttering is about 2%; and adult stuttering, 1%; there being higher prevalence among males than among females.[2] Over the years, numerous theories have been proposed to explain the etiology of stuttering. Although the etiology of stuttering is not fully understood, there is strong evidence to suggest that it emerges from a combination of constitutional and environmental factors. Psychological theories propose that individuals who stutter have a predisposition to a low emotional threshold and a limited neurophysiological makeup, which make them susceptible to emotional conditioning. A cognitive behavioral model highlights stuttering as a bio-psychosocial crisis.[2] The primary symptoms of the disorder include behavioral, psychological and sociological symptoms. The experiences of individuals with this disorder include negative affect; behavioral and cognitive reactions, both from the speaker who stutters and the environment. It also involves significant limitations in the individual's ability to participate in daily activities and a negative effect on the person's overall quality of life.[3] Individuals who stutter may strive for lower levels of achievement due to low self-esteem and the overwhelming fear of failure.[4]

The stuttering treatment outcomes have traditionally focused primarily on changes in the production-of-speech dysfluencies through behavior modification. The techniques included fluency skills such as easy breathing/ appropriate phrasing and prolongation-contingent punishment for stuttering, time-out, relaxation, speech-correcting technique.[5–7] Plexico[8] et al. in a study focused on self-therapy and behavioral and cognitive change by utilization of personal experience. Dath[9] used hyno relaxation, breathing, relaxation, speech-prolongation technique and found these effective reduction of stuttering. More integrated interventions emerged that served in ameliorating stuttering, such as stuttering therapy,[10] Camperdown program.[11] In a review, Bothe (2006)[12] concluded that the powerful treatments for adults, with respect to both speech outcomes and social, emotional or cognitive outcomes, appear to combine variants of prolonged speech, self-management, response contingencies and other infrastructural variables.

Though considerable research has documented the positive influence of therapeutic interventions on stuttering frequency and behavior, the literature review suggests that treatment program ranges from 3 months to 3 years, with variable number of sessions. Due to growing urbanization and changing profiles of work and demands of society, psychological factors play an important role in clients with stuttering. The present study was an attempt to examine the efficacy of cognitive behavior therapy in stuttering, in a shorter period of time.

Method

A pre-post intervention method was adopted. Five clients with a diagnosis of stuttering according to speech pathologist recruited from the outpatient services of NIMHANS, Bangalore. Clients with concurrent diagnosis of psychosis, organic brain syndrome, substance use, mental retardation, major medical illness or previous exposure to behavioral intervention were excluded from the study. Assessments were carried out at 3 points: at pre-therapy, mid-therapy and post-therapy. Informed consent for participation in the study was obtained from participants.

Tools

Socio-demographic and clinical data sheets (SDCS) were used to obtain socio-demographic details. The behavior analysis pro forma sheet[13] was used to analyze specific behavior in various areas, which included historical, social, cognitive and biological factors, thus providing comprehensive data on various variables needed for selecting appropriate intervention strategies. Stuttering was assessed by the Stuttering Severity Scale (SSI-1972),[14] Perception of Stuttering Scale, (PSI); anxiety, by Beck's Anxiety Inventory (BAI — Beck , Epstein, Brown and Steer, 1988); dysfunctional cognition was assessed by Dysfunctional Attitude Scale (DAS), Fear of Negative Evaluation (FNE — Watson and Friend, 1969); assertiveness, by Assertiveness Scale (AS — Butler, 1982); self-esteem was measured by Rosenberg's Self-Esteem Scale (RSES — Rosenberg, 1979)[15]; and quality of life, by World Health Organization - Quality of Life Scale (WHO-QOL-BREF — the WHO-QOL group, 1998).[16]

Procedure

Therapeutic program

The program consisted of 22 to 23 sessions in total, with 16 to 18 sessions for therapeutic intervention and the rest of the sessions were used for assessments. The duration of an individual session was 60 minutes. The sessions were carried out over a period of 4 to 6 weeks. Therapy was carried out in 2 phases: Phase I of CBT comprised of training in relaxation techniques, such as Jacobson's Progressive Muscle Relaxation, mindfulness meditation, deep breathing; and in speech techniques, such as humming and prolongation; for 8 sessions. Mid-assessment was carried out after completion of phase I of the therapy. In phase II, cognitive component of the therapy was added. The components of the second phase included techniques like cognitive restructuring, problem solving and assertiveness. The contents of the sessions in the therapy were kept flexible, taking into consideration the specific needs of each individual client.

CASE REPORTS

Case I

A 16-year-old unmarried male, studying for Diploma in Mechanical Engineering, hailing from middle socio economic status (MSES), with an urban background, presented with complaints of increased severity of stuttering while talking to teachers and seniors. Since childhood, he faced criticisms both at school and at home. As a consequence, he avoided speaking with people. His stuttering had increased in the last 1 year, following change of medium of instruction in his college. His stuttering significantly impacted his personal and social domains. He also experienced autonomic arousal such as sweating, palpitation and tremors. His personal history suggested that as a child, he was temperamentally shy and reserved. Family history suggested that his father was perceived by him to be more supportive than his mother.

Case II

An 18-year-old unmarried male, studying in the first year of B.E., hailing from MSES, presented with complaints of stuttering and anxiety since the past 11 years. The onset of stuttering was during childhood, and the stuttering had a continuous course. The client and his parents noticed the problem when he entered school. He would find it difficult to pronounce a word; or would miss out words in between sentences; sometimes would repeat the same letter of a single word, especially while speaking to teachers or any new student or a relative. He was ridiculed by some of his classmates when he was in high school. He would become irritable towards them. This would lead to increase in symptoms and he would feel very distressed with this. However, he would participate in sports and other extracurricular activities. Due to his father's transfer, the family shifted from one state to another. There were frequent changes of both school and the place of residence, which caused him difficulties in adjustment. To pursue further education, he came to an urban city. He would avoid situations where he felt that he may be evaluated negatively by others. He made attempts to overcome stuttering by practicing at home by standing in front of the mirror. During practice, he would feel dejected and feel helpless about his stuttering. Both his parents encouraged him to pursue his interest and appreciated his efforts. In childhood, he had a very limited number of friends; he feared being ridiculed by classmates.

Case III

A 24-year-old unmarried male, studying in the first year of M.Pharma, from a rural background, hailing from MSES, presented with complaints of stuttering in interactions with superiors and strangers and amidst groups of people. The onset of symptoms was during childhood. The client was brought up in a brought up from a orthodox and traditional environment; he would be engaged in solitary games most of the time. Expression of emotions by a male child was not encouraged in his sociocultural background. He would be physically punished by his father for untidy handwriting. He therefore would avoid conversing as he expected negative consequences. He would quarrel with friends when ridiculed by them. To avoid confrontation with others, he focused on his academics. He completed his graduation in B - Pharma but could not get a job due to his stuttering; the options available were teaching or marketing, both of which he felt extremely threatening and incapable of handling. He avoided interacting for fear of being rejected and negative evaluation. He experienced anxiety symptoms while stuttering. Overall interpersonal relationship with family was not cordial. There is a family history of stuttering in elder brother and nephew. Personal history suggested that as a child he was extremely shy and reserved.

Case IV

A 27-year-old unmarried male, currently pursuing his postgraduation in journalism, hailing from MSES, with a rural background, presented with complaints of stuttering since the age of 5 years. His symptoms included repetition of same syllables, difficulty in pronouncing words, lack of clarity in speech and swallowing the last few words in a sentence. These would increase in the presence of superiors, strangers and in group situations. The symptoms had had a fluctuating course. They aggravated when he was admitted to school and stabilized in high school; however, when he shifted to college, he moved from a village to a city for persuasion of a degree, and his symptoms aggravated. His course in journalism demanded of him to verbally present topics, which involved ample verbal communication. He felt that he did not have the requisite power of communication. His father was critical towards him. Personal history revealed that as a child, the client was an average student. Temperamentally, he was easy to warm up.

Case V

A 30-year-old unmarried male, educated up to Masters in Social Work, currently working as Human Resource Manager, presented with complaints of difficulties while speaking with superiors and in initiating a conversation, which began early in childhood. In order to overcome all this, he would strive harder to keep up his academic performance and fluent speech. The difficult situations included any conversation that was to be initiated with superiors and classmates, especially females. The client feared committing mistakes and would make an attempt to avoid them, He constantly felt that if he made an error he might be judged to be inferior and he would be subjected to ridicule and fun by others. He would isolate himself and portray to others that he was an unapproachable person. He would feel extremely uncomfortable to converse with relatives who visited his home, and if commented upon, he would get irritated towards his mother. He felt inadequate in leading the group for the projects assigned to him. Whenever any new project would come up, he would have thoughts about being a failure and would become tense, fearful and restless. Along with these, the client would also have dryness of mouth. This symptom would aggravate during presentations.

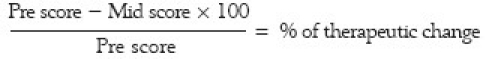

The Improvement Criteria Analysis was carried out calculating Clinically significant changes (50% and above) based on pre-therapy, mid-therapy and post therapy data (Blanchand and Schwart, 1988) was used to assess the efficacy of therapeutic intervention. Therapeutic change between pre- and mid-assessment was calculated in terms of percentages using the formula

Using the same formula between mid- and post–therapy assessments and between pre- and post-therapy assessments, % of therapeutic change was computed.

DISCUSSION

The results of this case series show that cognitive behavior strategies can be effective in reducing severity of stuttering, reducing the dysfunctional attitude and in enhancing assertiveness and improving quality of life of clients with stuttering. On analysis of results of individual cases, performances measured using SSI scores of subjects show that there was improvement observed between pre- and post-assessment phases; however, there was no improvement between the pre- and mid-assessment phases, indicating that along with behavioral techniques, cognitive components and more number of sessions would be required to bring about clinically significant changes in stuttering severity. However, in reducing anxiety, the analysis suggested 3 clients had clinically significant improvement in reduction of anxiety symptoms between pre- and post-assessment phases as compared to that between pre- and mid- and between mid- and post-assessment phases. The second objective was to study the efficacy of CBT in reducing dysfunctional cognitions. The individual analysis shows a positive trend in reduction of dysfunctional assumptions on scales of DAS, FNE. However there was significant clinical and statistical improvement (>50). The finding on DAS suggests that CBT was efficacious in reducing the severity of dysfunctional cognitions but not of dysfunctional assumptions. The third objective of the present study was to examine CBT in enhancing assertiveness in clients with stuttering. Subjectively, assertiveness skills of clients were reported to be positive from mid- to post-assessment phase. The fourth objective of the present study was to examine CBT in improving QOL. Results on WHO-QOL BREF show improvement in clients’ levels of satisfaction. The finding could be explained in terms of the time span of therapy. Since the QOL of an individual is influenced by a multitude of social and environment factors, it is probably more difficult to generalize therapeutic gains in real-life situations. The results of the present study are suggestive of the usefulness of CBT in reducing severity of stuttering, decreasing dysfunctional cognitions, enhancing assertiveness and QOL. However, the results are not clinically and statistically significant. There were qualitative changes reported subjectively by patients. Results of the present study are to be interpreted with caution; it requires further replication, validation and follow-up of CBT for stuttering to confirm its efficacy and usefulness in the treatment of this disorder. Outcome was assessed on the basis of clinically significant changes and statistical tests. In individual cases, results at post-therapy assessment indicate reduction of stuttering in 3 patients between pre- and post-therapy time points. Stuttering components such as struggle avoidance, expectancy were reduced for all 5 cases. There was a clinically significant reduction in 1 case. Clinically significant reduction in anxiety was seen in all clients. In the realm of dysfunctional cognitions, a positive favorable change was seen in all cases. In terms of self-esteem, 2 clients showed clinically significant improvement; whereas in 2 other patients, no improvement was seen; and in 1 client, there was positive change. Quality of life improved in all clients. One client had clinically significant improvement from pre- to mid-therapy, whereas the other client had improvement from pre- to post-therapy.

In conclusion, the present study indicates that CBT was partially effective in clients in reducing stuttering, reducing anxiety, reducing dysfunctional cognitions and in improving quality of Life. The implications of the study suggest usefulness of treatment protocol for clients with stuttering, along with the use of other techniques. The findings of the present study also suggest that more intensive research efforts are needed in the area to validate long-term effects. The limitations of the study include difficulty in generalization of the results due to the small sample size. Follow-up and long-term effects could not be assessed due to time constraints and therefore long-term efficacy could not be established. Control measures could not be exercised up to the desired standard. This hampers confidence in the validity of the results and findings. The quantitative improvement could not be objectively proved along with statistical significance. Suggestions for future research include that the study should be more comprehensive, including investigations of other relevant variables. Long-term efficacy of the therapeutic program should be established by follow-up over long periods. Studies should be conducted with better experimental control so as to enhance the confidence in the validity of the results.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (ICD-10) Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. World Health Organization (WHO) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bloodstein O. A Handbook on Stuttering. 2th ed. San Diego, CA: Singular Publishing Group; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yaruss JS, Quesal RW. Stuttering and the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health. J Commun Disord. 2004;34:163–82. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9924(03)00052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Riper C. In: The nature of stuttering. 2nd ed. Englewood Cliffs., editor. NJ: Prentice Hall, Inc; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andrews G, Guitar B, Howie P. Meta Analysis of the effects of stuttering treatment. J Speech Hear Disord. 1980;45:287–307. doi: 10.1044/jshd.4503.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manogoli S. Behavioral intervention in stuttering. M. Phil dissertation. NIMHANS. 1990 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Onslow M, Costa L, Andrews C, Packman A. Speech outcomes of a prolonged-speech treatment for stuttering. E Journal of speech and Language, and Hearing Research. 1996;39:739–49. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3904.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Plexico L, Manning WH, Dilollo A. A phenomenological understanding of successful stuttering management. J Fluency Disord. 2000;30:1–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jfludis.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dath S. A comparison study of fluency changes in the speech of stutters following hypnotherapy and speech therapy. PhD Thesis. NIMHANS. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blomgren M, Roy N, Callister T, Merrill RM. A Multidimensional Assessment of Treatment Outcomes. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2005;48:509–23. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2005/035). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Brian S, Onslow M, Cream A, Packman A. The Camperdown Program: Outcomes of a new prolonged-speech treatment model. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2001;46:933–46. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2003/073). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bothe AK, Davidow JH, Bramlett RE, Ingham RJ. Stuttering Treatment Research 1970–2005: I. Systematic Review Incorporating Trial Quality Assessment of Behavioral, Cognitive, and Related Approaches. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2006;15:321–41. doi: 10.1044/1058-0360(2006/031). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanfer FH, Saslow GC. Behavioural diagnosis. In: Franks CM, editor. Behaviour Therapy: Appraisal and status. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riley GD. A stuttering severity instrument for children and adults. J Speech Hear Disord. 1972;37:321–30. doi: 10.1044/jshd.3703.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenberg . Self- esteem scale: From Convincing the Self. New York: Basic books Inc; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 16.The WHOQOL Group. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF Quality of life Assessment. Psychological Med. 1998;28:551–8. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798006667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]