Abstract

Background

With increasing calls for linking HIV-infected individuals to treatment and care via expanded testing, we examined socio-demographic and behavioral characteristics associated with HIV testing among men and women in Soweto, South Africa.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional household survey involving 1539 men and 1877 women as part of the community-randomized prevention trial Project ACCEPT/HPTN043 between July 2007-October 2007. Multivariable logistic regression models, stratified by sex, assessed factors associated with HIV testing, and then repeated testing.

Results

Most women (64.8%) and 28.9% of men reported ever having been tested for HIV, among whom 57.9% reported repeated HIV testing. In multivariable analyses, youth and students had a lower odds of HIV testing. Men and women who had conversations about HIV/AIDS with increasing frequency and who had heard about antiretroviral therapy were more likely to report HIV testing, as well as repeated testing. Men who had ≥12 years of education and who were of high socio-economic status; and women who were married, who were of low socio-economic status, and who had children under their care had a higher odds of HIV testing. Women, older individuals, those with higher levels of education, married individuals, and those with children under their care had a higher odds of reporting repeated HIV testing. Uptake of HIV testing was not associated with condom use, having multiple sex partners, and HIV-related stigma.

Conclusions

Given the low uptake of HIV testing among men and youth, further targeted interventions could facilitate a test and treat strategy among urban South Africans.

Keywords: HIV, AIDS, VCT, testing, Africa

INTRODUCTION

There have been increasing calls to expand access to HIV testing and then promptly link those found to be HIV-infected to care and treatment in settings with high HIV prevalence1, 2. HIV voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) can be an important strategy for primary prevention and an entry point to care, treatment, and support for those found to be HIV-infected3, 4. Studies have demonstrated the efficacy of VCT in decreasing risky sexual behaviors in generally health populations5–7. However, individuals who report repeated VCT uptake may be more likely to engage in high-risk sexual behaviors8 and may also have higher rates of HIV acquisition9, 10, and hence may represent a potential group for targeted prevention interventions11. Most studies to date that have provided a clearer understanding of risk behaviors and socio-demographic characteristics associated with HIV testing have been conducted in the developed world among high-risk groups9, 11, 12. As VCT becomes an integrated part of a comprehensive HIV prevention and care strategy in resource-limited settings, further regional data assessing individual-level characteristics associated with HIV testing from the general population are warranted4, 13, 14.

Examining access to HIV testing in South Africa is timely as the government recently launched a national effort to test 15 million individuals for HIV and to start an estimated 0.5 million new HIV-infected individuals on antiretroviral therapy (ART) by 201115. South Africa is home to the largest HIV epidemic in the world, with 5.7 million infected individuals, prevalence among adults aged 15–49 years of nearly 20%16, and an estimated incidence in young women of 5.5 per 100 woman-years17. HIV prevalence among South African youth is among the highest in the world, which is likely driven by a range of sexual behaviors, including low levels of condom use, multiple sex partners, and densely connected sexual networks in which few HIV individuals are aware of their infection18–23. In light of increases in population testing and ART initiation in South Africa24, the current study utilizing a large representative sample of the general population can inform programs aimed at expanded testing and linkage of HIV-infected individuals to care and treatment.

We conducted a household survey in Soweto, South Africa to determine socio-demographic and behavioral characteristics associated with HIV testing among men and women as part of the baseline assessment for the community randomized trial Project ACCEPT/HPTN 043. We also examined differences between individuals who reported first-time HIV testing compared to those who reported repeated testing.

METHODS

Setting and participants

A baseline household survey was conducted in communities in Soweto between July 2007 to October 2007. Soweto, an urban African township in Gauteng Province, is located outside Johannesburg, with a population of approximately 1 million people living in an area of nearly 63 square kilometers25. Ten communities, each having a population size ranging from 15,000–20,000, were assessed. Further details about the study design, sampling procedures, including household enumeration and sampling procedures, and methods of this trial can be found elsewhere26. Briefly, a multistage sampling strategy was used to enumerate all households in each community. Households were randomly ordered and selected in batches of a pre-specified size, and all households within a batch were visited by interview teams until the target sample sizes were reached and all households in the batch were visited. One eligible household member, who met the residency criteria and was aged 18–32 years, was randomly selected to be interviewed in each household.

All assessments were performed via face-to-face interview, but no individual identifying information was collected, so participants remained anonymous. The study received ethical approval by the University of Witwatersrand.

Measurement instrument

Interviews took place in a private place in the participant’s household. The interviews were conducted in the language of the participants’ choice, including Sotho, Zulu, Tsonga, and English. Themes addressed in the baseline survey included issues such as alcohol and substance use; sexual risk behaviors; conversations about HIV/AIDS; HIV testing history and disclosure of HIV status; social norms on HIV testing; HIV/AIDS stigma; and knowledge and uptake of ART. Further information about instrument development and validation can be found elsewhere27.

HIV testing

The outcome variable of HIV testing was defined as “Have you ever been tested for HIV?” followed by the number of times a person has been tested and the reasons for testing. Responses were coded as never tested, non-voluntary (including pregnancy), tested once, and repeated testing (i.e. two or more occasions). HIV status was assessed by asking a respondent “What were the results of your last HIV test?” Answer choices included HIV-negative, HIV-positive, don’t know, and refused to answer. If participants had not been tested, they were asked questions about barriers to testing.

Socio-economic variables

The following socio-economic variables were assessed: age, education, primary occupation, income, marital status, currently has a sex partner, source of medical care, and plans to migrate. Socio-economic status was assessed as “high” if the participant owned a car, “medium” if did not own a car but did own at least two of the following items, namely drinking water in house, refrigerator, or cell phone, and “low” if otherwise.

Behavioral variables

The following behavioral variables were assessed: ever used alcohol, ever used drugs, ever had vaginal sex, and ever had anal sex. Sexual behavior over the past 6 months was assessed by inquiring about sexual frequency (regardless of the number of sex partners) and frequency of condom use. Condom use with spouse and other sex partners, number of sex partners, and forced sex were analyzed only among the subset of participants who reported being sexually active in the last 6 months. Participants were classified as “consistent” condom users if they reported using condoms for 100% of reported sex acts with all sex partners in the last month, and otherwise were classified as “inconsistent”. Participants were also asked whether they had experienced physical abuse by a sex partner, had an unwanted sexual experience before the age of 12, and had experienced physical violence before the age of 12.

Participants were asked about talking about HIV/AIDS, social norms around HIV testing, and HIV-associated stigma, and further information about how these items were operationally defined and measured can be found elsewhere28. Briefly, conversations about HIV/AIDS were assessed by asking participants if they had talked to anyone about HIV/AIDS in the last 6 months. Next, participants were asked to whom they had talked to in the last 6 months. Responses were coded into three ordinal factors: “never,” “some,” and “common” conservations about HIV/AIDS. Participants were also asked if they had heard of ART. Social norms around HIV testing were assessed with six questions, each with response choices on a Likert scale28. After calculating an overall social norms index, scores were divided into three categories—“unfavorable,” “intermediate,” and “favorable” based on the underlying distribution. HIV-related stigma was assessed with a 19-item scale, each with responses on a 5-point Likert scale, specifically developed for measuring HIV stigma in developing countries29. The overall stigma score was split into three categories: “low,” “intermediate,” and “high” based on the underlying distribution.

Statistical analyses

The primary outcome was first dichotomized as “HIV testing” and “no HIV testing” as never tested. In order to better elucidate sex-specific characteristics associated with HIV testing (effect modification), we present analyses stratified by participant sex (men vs. women). We then examined participants who reported “first-time HIV testing” relative to those who reported “repeated HIV testing.” Multivariable logistic regression models were used to calculate adjusted odds ratios (AOR) of factors associated with HIV testing. In order to elucidate the impact of more distal socio-demographic factors on more proximate behavioral factors30, 31, we constructed two multivariable logistic models, in which we first examined socio-demographic factors associated with HIV testing, and then examined behavioral factors after controlling for socio-demographic factors. A stepwise approach was used to identify independent risk factors in which variables whose association reached significance (p<0.20) were first examined, and those variables independently associated with HIV testing (p<0.10) were retained in the core model. Confounding was assessed based on either a change of >0.10 of the non-log transformed beta coefficient of independent risk factors, or a priori confounders indentified from the literature. Colinearity of included variables was examined. All data analyses were conducted using STATA (STATACORP, version 10.0, College Station, TX) software.

RESULTS

HIV testing among South African men and women

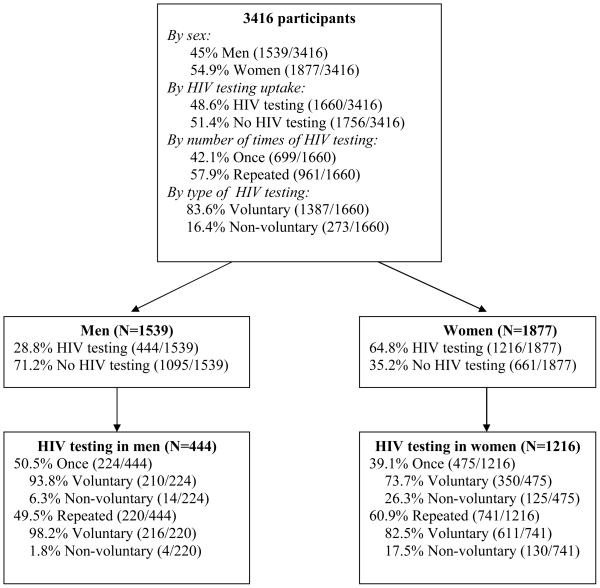

Among the 3416 enrolled participants, over half (54.9%) were women. A little under half (48.6%) of the participants reported ever having tested for HIV, with more women (64.8%) reporting past testing than men (28.9%) (p<0.0001). Among those who had ever been tested, 57.9% reported repeated HIV testing, which was also more common among women than men (60.9% vs. 49.5%; p<0.0001). Within the past 12 months, 16.8% of men and 43.8% of women reported having tested for HIV. Figure 1 presents the distribution of HIV testing by sex, number of times (first vs. repeated testing), and type (voluntary vs. non-voluntary testing). For men and women who reported never having undergone HIV testing (51.4%), the main reasons included: not thinking they were at risk (37.0%), being nervous about getting test results (17.0%), and not thinking of getting tested (14.2%).

Figure 1.

Distribution of participants

Socio-demographic characteristics associated with having tested for HIV by sex

Table 1a and 1b present univariate and multivariable analyses for socio-demographic factors associated with having tested for HIV for men and women, respectively. In multivariable analyses, men who were older (>23 years), who had ≥12 years of education, and who were of moderate and high socio-economic status had a higher odds of having tested for HIV. Men who were students, who were unemployed, who received care from the traditional medical sector, and who did not have a sex partner had a lower odds of having tested for HIV. Women who were older (>23 years), who were married, and who had ≥1 child under their care had a higher odds of having tested for HIV. Women who were students, who were of high socio-economic status, and who did not have a sex partner had a lower odds of having tested for HIV.

Table 1a.

Socio-demographic factors associated with HIV testing among men in Soweto, South Africa (N=1539)

| Socio-demographic variables | Proportion reporting HIV testing | Unadjusted odds ratio, OR (95% CI); p-value | Adjusted odds ratio, AOR (95% CI); p-value** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, % (N=444) | No, % (N=1095) | |||

| Age, years* | ||||

| 18–23 | 36.8 | 57.9 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 23–28 | 31.8 | 21.5 | 2.32 (1.84–2.95); <0.0001 | 2.08 (1.56–2.79); <0.0001 |

| ≥28 | 31.3 | 20.6 | 2.40 (1.89–3.04); <0.0001 | 1.94 (1.39–2.69); <0.0001 |

|

| ||||

| Education, years | ||||

| 7 or below | 7.5 | 6.7 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 8–12 | 82.6 | 81.4 | 0.90 (0.62–1.31); 0.591 | 1.30 (0.82–2.06); 0.249 |

| ≥12 | 10.0 | 12.0 | 0.74 (0.47–1.17); 0.199 | 2.09 (1.19–3.66); 0.010 |

|

| ||||

| Primary occupation* | ||||

| Employed | 66.7 | 46.7 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Unemployed | 23.5 | 28.9 | 0.57 (0.44–0.74); <0.0001 | 0.69 (0.49–0.97); 0.035 |

| Student | 9.7 | 24.4 | 0.28 (0.20–0.40); <0.0001 | 0.43 (0.28–0.66); <0.0001 |

|

| ||||

| Received income in the last year* | ||||

| Yes | 78.6 | 66.5 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| No | 21.4 | 33.5 | 0.54 (0.42–0.70); <0.0001 | 0.95 (0.67–1.34); 0.790 |

|

| ||||

| Socioeconomic status (SES)* | ||||

| Low | 16.0 | 22.5 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Moderate | 53.2 | 54.9 | 1.36 (1.00–1.84); 0.046 | 1.65 (1.20–2.26); 0.002 |

| High | 30.7 | 22.5 | 1.91 (1.36–2.68); <0.0001 | 2.26 (1.59–3.22); <0.0001 |

|

| ||||

| Marital status* | ||||

| Single | 81.3 | 91.7 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Married | 18.8 | 8.3 | 2.54 (1.86–3.47); <0.0001 | 1.49 (0.97–2.30); 0.065 |

|

| ||||

| Currently has a sex partner | ||||

| Yes | 77.9 | 66.1 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| No | 22.1 | 33.9 | 0.55 (0.43–0.71); <0.0001 | 0.69 (0.52–0.90); 0.008 |

|

| ||||

| Source of medical care when in need | ||||

| Public sector | 68.5 | 71.7 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Traditional system | 2.0 | 5.0 | 0.43 (0.21–0.88); 0.021 | 0.42 (0.20–0.88); 0.023 |

| Private/NGO Sector | 29.5 | 23.3 | 1.32 (1.03–1.70); 0.028 | 1.15 (0.87–1.51); 0.309 |

|

| ||||

| Plans to migrate in the next 2.5 years | ||||

| Yes | 39.9 | 34.8 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| No | 60.1 | 67.1 | 0.74 (0.59–0.93); 0.009 | 0.81 (0.64–1.04); 0.105 |

Multivariable model adjusted for age, earned income in the last 12 months, primary occupation, socioeconomic status, and marital status

Bolded findings reflect statistically significant results (p<0.05).

Table 1b.

Socio-demographic factors associated with HIV testing among women in Soweto, South Africa (N=1877)

| Socio-demographic variables | Proportion reporting HIV testing | Unadjusted odds ratio, OR (95% CI); p-value | Adjusted odds ratio, AOR (95% CI); p- value** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, % (N=1216 | No, % (N=661) | |||

| Age, years* | ||||

| 18–23 | 31.3 | 55.0 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 23–28 | 41.0 | 27.1 | 2.65 (2.04–3.45); <0.0001 | 1.60 (1.23–2.07); <0.0001 |

| ≥28 | 27.7 | 17.9 | 2.72 (2.03–3.64); <0.0001 | 1.40 (1.07–1.85); 0.013 |

|

| ||||

| Education, years | ||||

| 7 or below | 6.5 | 8.9 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 8–12 | 77.0 | 82.4 | 1.27 (0.82–1.96); 0.280 | 1.26 (0.85–1.89); 0.240 |

| ≥12 | 16.4 | 8.7 | 2.57 (1.54–4.30); <0.0001 | 1.19 (0.72–1.96); 0.481 |

|

| ||||

| Primary occupation* | ||||

| Employed | 36.1 | 30.6 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Unemployed | 54.9 | 41.4 | 1.12 (0.90–1.40); 0.293 | 1.08 (0.83–1.41); 0.522 |

| Student | 9.0 | 28.0 | 0.27 (0.20–0.36); <0.0001 | 0.36 (0.26–0.52); <0.0001 |

|

| ||||

| Received income in the last year* | ||||

| Yes | 63.8 | 58.3 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| No | 36.2 | 41.7 | 0.79 (0.65–0.96); 0.020 | 0.96 (0.75–1.22); 0.769 |

|

| ||||

| Socioeconomic status (SES)* | ||||

| Low | 18.7 | 13.2 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Moderate | 58.4 | 58.7 | 0.69 (0.52–0.92); 0.011 | 0.77 (0.58–1.03); 0.086 |

| High | 22.8 | 28.1 | 0.56 (0.41–0.77); <0.0001 | 0.63 (0.45–0.88); 0.008 |

|

| ||||

| Marital status* | ||||

| Single | 89.0 | 95.1 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Married | 11.0 | 4.9 | 2.39 (1.59–3.57); <0.0001 | 1.92 (1.38–2.69); <0.0001 |

|

| ||||

| Currently has a sex partner | ||||

| Yes | 83.5 | 62.7 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| No | 16.5 | 37.3 | 0.33 (0.27–0.42); <0.0001 | 0.45 (0.36–0.58); <0.0001 |

|

| ||||

| Children under care* | ||||

| 0 | 21.5 | 35.0 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | 54.9 | 48.9 | 1.82 (1.46–2.27); <0.0001 | 1.66 (1.31–2.09); <0.0001 |

| ≥2 | 23.6 | 16.1 | 2.39 (1.79–3.17); <0.0001 | 2.23 (1.65–3.01); <0.0001 |

|

| ||||

| Source of medical care when in need | ||||

| Public sector | 74.6 | 66.8 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Traditional system | 1.3 | 2.0 | 0.60 (0.29–1.26); 0.178 | 0.69 (0.32–1.50); 0.358 |

| Private/NGO Sector | 18.1 | 31.2 | 0.69 (0.56–0.86); 0.001 | 0.81 (0.63–1.03); 0.093 |

|

| ||||

| Plans to migrate in the next 2.5 years | ||||

| Yes | 35.1 | 32.1 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| No | 64.9 | 67.9 | 1.04 (0.86–1.27); 0.654 | 0.77 (0.62–0.96); 0.022 |

Multivariable model adjusted for age, earned income in the last 12 months, primary occupation, socioeconomic status, marital status, and children under care

Bolded findings reflect statistically significant results (p<0.05).

Behavioral characteristics associated with having tested for HIV by sex

Tables 2a and 2b present univariate and multivariable analyses of behavioral factors associated with having tested for HIV for men and women, respectively. Men who ever had vaginal sex, ever had anal sex, and who had sex in the last 6 months had a higher odds of having tested for HIV. Women who ever had vaginal sex, who had ≥1 lifetime sex partners, and who had sex in the last 6 months had a higher odds of having tested for HIV. Both men and women who had ever talked about HIV/AIDS, who had conversations about HIV/AIDS with increasing frequency, and who had heard of ART had a higher odds of having tested for HIV. Men and women who had experienced physical violence before the age of 12 had a higher odds of having tested for HIV, and also women who had ever been physically abused by a sex partner. Condom use, number of sex partners in the last 6 months, HIV-related stigma, and substance use were not significantly associated with having tested for HIV for both men and women.

Table 2a.

Behavioral factors associated with HIV testing among men in Soweto, South Africa (N=1539)

| Behavioral variables | Proportion reporting HIV testing | Unadjusted odds ratio, OR (95% CI); p-value | Adjusted odds ratio, AOR (95% CI); p- value*** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, % (N=444) | No, % (N=1095) | |||

| Ever used alcohol | ||||

| Yes | 83.8 | 79.4 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| No | 16.2 | 20.6 | 0.75 (0.56–1.00); 0.050 | 0.78 (0.57–1.06); 0.113 |

|

| ||||

| Ever used drugs | ||||

| Yes | 25.2 | 23.1 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| No | 74.8 | 76.9 | 0.89 (0.69–1.15); 0.386 | 0.83 (0.63–1.09); 0.199 |

|

| ||||

| Ever had vaginal sex | ||||

| No | 5.2 | 12.9 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 94.8 | 87.1 | 2.71 (1.72–4.27); <0.0001 | 1.71 (1.05–2.76); 0.028 |

|

| ||||

| Ever had anal sex | ||||

| No | 86.0 | 91.3 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 14.0 | 8.7 | 1.71 (1.21–2.40); 0.002 | 1.48 (1.03–2.12); 0.031 |

|

| ||||

| # of lifetime sex partners | ||||

| 0 | 9.2 | 16.2 | 1.00 | |

| 1 | 7.7 | 10.0 | 1.33 (0.80–2.23); 0.271 | 1.21 (0.70–2.07); 0.480 |

| 2–4 | 32.0 | 31.6 | 1.77 (1.20–2.62); 0.004 | 1.43 (0.94–2.16); 0.087 |

| ≥4 | 51.1 | 42.2 | 2.12 (1.46–3.09); <0.001 | 1.46 (0.98–2.18); 0.061 |

|

| ||||

| Had sex in the last 6 months | ||||

| No | 20.2 | 28.9 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 80.0 | 71.1 | 1.44 (1.22––1.70); <0.0001 | 1.45 (1.11–1.89); 0.006 |

|

| ||||

| Frequency of sex in the last 6 months** | ||||

| 1–2 times month | 30.7 | 35.8 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| More than twice a month | 29.8 | 26.7 | 1.31 (0.93–1.84); 0.117 | 1.11 (0.77–1.58); 0.559 |

| 2–4 times a week | 29.5 | 30.0 | 1.14 (0.82–1.60); 0.419 | 0.89 (0.62–1.27); 0.530 |

| ≥4 times a week | 10.0 | 7.5 | 1.55 (0.94–2.55); 0.082 | 1.15 (0.68–1.94); 0.586 |

|

| ||||

| # of sex partners in the last 6 months** | ||||

| 1 | 80.0 | 67.5 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 2 | 11.4 | 17.7 | 0.56 (0.37–0.83); 0.004 | 0.66 (0.44–1.00); 0.055 |

| > 2 | 8.7 | 12.8 | 0.59 (0.37–0.92); 0.023 | 0.68 (0.42–1.09); 0.114 |

|

| ||||

| Condom use in the last 6 months** | ||||

| Inconsistent | 66.9 | 71.4 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Consistent | 32.8 | 28.2 | 1.24 (0.93–1.65); 0.130 | 0.92 (0.67–1.26); 0.629 |

|

| ||||

| Condom use with spouse in the last 1 month** | ||||

| Inconsistent | 89.1 | 95.2 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Consistent | 10.9 | 4.8 | 2.43 (1.33–4.46); 0.004 | 1.36 (0.48–3.80); 0.557 |

|

| ||||

| Condom use with non-spousal partners in the last 1 month** | ||||

| Inconsistent | 76.6 | 71.4 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Consistent | 23.4 | 28.4 | 0.76 (0.52–1.09); 0.146 | 0.70 (0.46–1.04); 0.081 |

|

| ||||

| Forced to have sex in the last 6 months** | ||||

| No | 93.7 | 95.1 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 6.3 | 4.9 | 1.28 (0.73–2.26); 0.377 | 1.33 (0.74–2.38); 0.332 |

|

| ||||

| Ever physically abused by a sex partner | ||||

| No | 94.8 | 96.2 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 5.2 | 3.8 | 1.37 (0.81–2.30); 0.237 | 1.28 (0.74–2.22); 0.360 |

|

| ||||

| Unwanted sexual experience before age 12 | ||||

| No | 95.3 | 96.2 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 4.7 | 3.8 | 1.25 (0.69–2.18); 0.42 | 0.78 (0.44–1.38); 0.407 |

|

| ||||

| Experienced physical violence before age 12 | ||||

| No | 82.4 | 86.6 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 17.6 | 13.4 | 1.38 (1.01–1.88); 0.0346 | 1.43 (1.04–1.97); 0.025 |

|

| ||||

| Talked to anyone about HIV/AIDS in lifetime | ||||

| No | 5.6 | 16.9 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 94.4 | 83.1 | 3.40 (2.19–5.48); <0.0001 | 3.39 (2.16–5.30); <0.0001 |

|

| ||||

| Conversations about HIV/AIDS scale | ||||

| None | 16.4 | 30.0 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Some | 38.3 | 43.3 | 1.61 (1.18–2.19); 0.002 | 1.69 (1.23–2.33); 0.001 |

| Common | 45.3 | 26.8 | 3.08 (2.25–4.20); <0.0001 | 2.61 (1.89–3.61); <0.0001 |

|

| ||||

| Stigma scale | ||||

| Low | 28.7 | 25.9 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Intermediate | 48.9 | 48.8 | 0.90 (0.69–1.17); 0.446 | 1.02 (0.77–1.35); 0.855 |

| High | 22.4 | 25.3 | 0.80 (0.58–1.09); 0.151 | 0.91 (0.65–1.26); 0.576 |

|

| ||||

| Social norms scale | ||||

| Unfavorable | 31.9 | 27.0 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Intermediate | 58.6 | 63.4 | 0.78 (0.61–1.00); 0.050 | 0.75 (0.58–0.97); 0.030 |

| Favorable | 9.5 | 9.6 | 0.84 (0.56–1.26); 0.395 | 0.80 (0.52–1.24); 0.331 |

|

| ||||

| Heard of antiretroviral treatment | ||||

| Yes | 77.1 | 64.9 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| No | 22.9 | 35.0 | 0.55 (0.43–0.71); <0.0001 | 1.65 (1.27–2.16); <0.0001 |

Multivariable model adjusted for age, earned income in the last 12 months, primary occupation, socioeconomic status, and marital status

Analyzed only on the subset of participants who reported being sexually active in the last 6 months

Bolded findings reflect statistically significant results (p<0.05).

Table 2b.

Behavioral factors associated with HIV testing among women in Soweto, South Africa (N=1877)

| Behavioral variables | Proportion reporting HIV testing | Unadjusted odds ratio, OR (95% CI); p-value | Adjusted odds ratio, AOR (95% CI); p- value*** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, % (N=1216) | No, % (N=661) | |||

| Ever used alcohol | ||||

| Yes | 58.4 | 59.5 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| No | 41.6 | 40.5 | 0.75 (0.56–1.00); 0.050 | 0.84 (0.68–1.04); 0.119 |

|

| ||||

| Ever used drugs | ||||

| Yes | 3.4 | 3.6 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| No | 96.6 | 96.4 | 1.07 (0.64–1.80); 0.769 | 0.78 (0.45–1.35); 0.391 |

|

| ||||

| Ever had vaginal sex | ||||

| No | 3.8 | 14.1 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 96.2 | 74.0 | 8.95 (6.35–12.59); <0.0001 | 5.83 (4.05–8.41); <0.0001 |

|

| ||||

| Ever had anal sex | ||||

| No | 91.8 | 93.0 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 8.2 | 6.8 | 1.20 (0.83–1.72); 0.329 | 1.12 (0.76–1.64); 0.547 |

|

| ||||

| # of lifetime sex partners | ||||

| 0 | 8.0 | 28.6 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | 23.2 | 22.7 | 3.66 (2.67–5.02); <0.0001 | 3.06 (2.19–4.28); <0.0001 |

| 2–4 | 53.3 | 37.2 | 5.13 (3.85–6.83); <0.0001 | 3.52 (2.59–4.79); <0.0001 |

| ≥4 | 15.5 | 11.5 | 4.85 (3.37–6.96); <0.0001 | 3.32 (2.26–4.89); <0.0001 |

|

| ||||

| Had sex in the last 6 months | ||||

| No | 25.3 | 46.3 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 74.7 | 53.7 | 2.54 (2.08–3.10); <0.0001 | 1.90 (1.53–2.36); <0.0001 |

|

| ||||

| Frequency of sex in the last 6 months** | ||||

| 1–2 times month | 28.6 | 32.6 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| More than twice a month | 24.6 | 26.3 | 1.06 (0.76–1.47); 0.713 | 0.92 (0.65–1.30); 0.668 |

| 2–4 times a week | 38.7 | 30.9 | 1.42 (1.05–1.94); 0.023 | 1.23 (0.88–1.71); 0.216 |

| ≥4 times a week | 8.2 | 10.2 | 0.90 (0.57–1.43); 0.676 | 0.83 (0.51–1.35); 0.471 |

|

| ||||

| # of sex partners in the last 6 months** | ||||

| 1 | 96.3 | 96.3 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 2 | 2.1 | 2.8 | 0.75 (0.34–1.63); 0.470 | 0.73 (0.33–1.63); 0.453 |

| > 2 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 1.85 (0.52–6.46); 0.338 | 1.91 (0.54–6.81); 0.313 |

|

| ||||

| Condom use in the last 6 months** | ||||

| Inconsistent | 56.1 | 63.2 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Consistent | 43.9 | 36.8 | 1.34 (1.04–1.73); 0.022 | 1.20 (0.91–1.58); 0.192 |

|

| ||||

| Condom use with spouse in the last 1 month** | ||||

| Inconsistent | 84.5 | 86.6 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Consistent | 15.5 | 13.4 | 1.18 (0.79–1.78); 0.409 | 0.57 (0.30–1.11); 0.102 |

|

| ||||

| Condom use with non-spousal partners in the last 1 month** | ||||

| Inconsistent | 70.9 | 72.5 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Consistent | 29.1 | 27.5 | 1.08 (0.78–1.48); 0.635 | 1.17 (0.82–1.66); 0.384 |

|

| ||||

| Forced to have sex in the last 6 months** | ||||

| No | 97.2 | 96.6 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 2.8 | 3.4 | 0.80 (0.40–1.62); 0.553 | 1.00 (0.47–2.12); 0.987 |

|

| ||||

| Ever physically abused by a sex partner | ||||

| No | 84.9 | 91.4 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 15.1 | 8.6 | 1.88 (1.37–2.57); <0.0001 | 1.83 (1.67–3.04); <0.0001 |

|

| ||||

| Unwanted sexual experience before age 12 | ||||

| No | 94.3 | 95.6 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 6.0 | 4.4 | 1.31 (0.83–2.13); 0.2282 | 1.24 (0.77–1.99); 0.368 |

|

| ||||

| Experienced physical violence before age 12 | ||||

| No | 89.4 | 92.7 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 10.6 | 7.3 | 1.52 (1.06–2.19); 0.0175 | 1.53 (1.06–2.21); 0.023 |

|

| ||||

| Talked to anyone about HIV/AIDS in lifetime | ||||

| No | 9.5 | 17.1 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 90.5 | 82.9 | 1.97 (1.48–2.63); <0.0001 | 2.47 (1.83–3.33); <0.0001 |

|

| ||||

| Conversations about HIV/AIDS scale | ||||

| None | 19.4 | 30.9 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Some | 36.4 | 38.1 | 1.51 (1.19–1.93); 0.001 | 1.59 (1.23–2.07); <0.0001 |

| Common | 44.2 | 31.0 | 2.26 (1.76–2.89); <0.0001 | 2.32 (1.77–3.04); <0.0001 |

|

| ||||

| Stigma scale | ||||

| Low | 26.7 | 24.4 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Intermediate | 48.8 | 52.6 | 0.85 (0.67–1.07); 0.157 | 0.80 (0.63–1.03); 0.093 |

| High | 24.6 | 23.0 | 0.98 (0.74–1.28); 0.868 | 0.96 (0.72–1.29); 0.827 |

|

| ||||

| Social norms scale | ||||

| Unfavorable | 32.6 | 27.3 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Intermediate | 58.8 | 65.0 | 0.76 (0.61–0.94); 0.011 | 0.71 (0.57–0.89); 0.004 |

| Favorable | 8.6 | 7.7 | 0.93 (0.64–1.36); 0.704 | 0.95 (0.63–1.43); 0.840 |

|

| ||||

| Heard of antiretroviral treatment | ||||

| No | 20.9 | 29.8 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 79.1 | 70.1 | 1.61 (1.30–2.01); <0.0001 | 1.80 (1.43–2.28); <0.0001 |

Multivariable model adjusted for age, earned income in the last 12 months, primary occupation, socioeconomic status, marital status, and children under care.

Analyzed only on the subset of participants who reported being sexually active in the last 6 months

Bolded findings reflect statistically significant results (p<0.05).

Multivariable analysis of characteristics associated with first and repeated HIV testing

Tables 3a and 3b present multivariable analyses of socio-demographic and behavioral factors, respectively, associated with first-time and repeated HIV testing compared to those who reported no HIV testing. In general, these associations were stronger for those who reported repeated HIV testing compared to those who reported first-time HIV testing. Women, those who were older, and those who had children under their care had a higher odds of reporting both first-time and repeat HIV testing. Students and those who did not currently have a sex partner had a lower odds of first-time and repeat HIV testing. Those who had undergone repeat HIV testing were more likely to have higher levels of education (≥8 years) and be married. Both first-time and repeat HIV testing were not associated with income nor socio-economic status.

Table 3a.

Socio-demographic factors associated with first-time and repeat HIV testing compared to no HIV testing among men and women in Soweto, South Africa (N=3416)

| Proportion reporting HIV testing, % | Adjusted odds ratio, AOR (95% CI); p-value* | Adjusted odds ratio, AOR (95% CI); p-value* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographic variables | No HIV testing (N=1756) | First- time HIV testing (N=699) | Repeat HIV testing (N=961) | First-time HIV testing vs. no HIV testing | Repeat HIV testing vs. no HIV testing |

| Gender † ┼ | |||||

| Male | 37.6 | 32.0 | 22.9 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Female | 62.4 | 68.0 | 77.1 | 3.45 (2.83–4.22); <0.0001 | 5.32 (4.35–6.52); <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Age, years † ┼ | |||||

| 18–23 | 56.1 | 44.8 | 28.5 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 23–28 | 25.0 | 31.3 | 36.4 | 1.41 (1.11–1.79); 0.004 | 2.02 (1.60–2.55); <0.0001 |

| ≥28 | 18.9 | 23.9 | 35.1 | 1.19 (0.92–1.54); 0.180 | 2.00 (1.55–2.57); <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Education, years ┼ | |||||

| 7 or below | 8.0 | 8.0 | 6.7 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 8–12 | 82.0 | 80.5 | 81.5 | 1.11 (0.78–1.58); 0.551 | 1.53 (1.07–2.19); 0.017 |

| ≥12 | 9.9 | 11.4 | 11.9 | 1.33 (0.84–2.09); 0.212 | 1.79 (1.15–2.79); 0.010 |

|

| |||||

| Primary occupation † ┼ | |||||

| Employed | 40.6 | 39.7 | 47.6 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Unemployed | 33.6 | 46.3 | 46.7 | 1.05 (0.84–1.31); 0.625 | 0.83 (0.65–1.06); 0.147 |

| Student | 25.8 | 13.9 | 5.7 | 0.58 (0.43–0.79); <0.0001 | 0.23 (0.16–0.34); <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Received income in the last year ┼ | |||||

| Yes | 63.4 | 66.0 | 68.9 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| No | 36.6 | 34.0 | 31.1 | 0.90 (0.71–1.14); 0.390 | 1.10 (0.86–1.40); 0.417 |

|

| |||||

| Socioeconomic status (SES) | |||||

| Low | 20.0 | 18.8 | 17.5 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Moderate | 56.4 | 55.7 | 58.0 | 0.98 (0.76–1.26); 0.905 | 1.06 (0.82–1.37); 0.625 |

| High | 24.6 | 25.5 | 24.5 | 1.14 (0.85–1.54); 0.370 | 1.00 (0.74–1.35); 0.959 |

|

| |||||

| Marital status ┼ | |||||

| Single | 93.8 | 89.1 | 79.1 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Married | 6.2 | 10.9 | 20.9 | 1.14 (0.81–1.60); 0.441 | 1.66 (1.24–2.23); 0.001 |

|

| |||||

| Currently has a sex partner † ┼ | |||||

| Yes | 64.8 | 78.8 | 84.3 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| No | 35.2 | 21.2 | 15.7 | 0.54 (0.43–0.68); <0.0001 | 0.49 (0.39–0.62); <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Children under care † ┼ | |||||

| 0 | 44.1 | 33.0 | 25.9 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | 41.9 | 48.2 | 51.8 | 1.23 (1.00–1.53); 0.044 | 1.54 (1.25–1.91); <0.0001 |

| ≥2 | 14.0 | 18.7 | 22.3 | 1.43 (1.08–1.89); 0.011 | 2.05 (1.56–2.70); <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Source of medical care when in need † | |||||

| Public sector | 69.9 | 75.9 | 70.8 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Traditional system | 3.8 | 1.9 | 1.3 | 0.54 (0.29–1.02); 0.061 | 0.45 (0.23–0.90); 0.023 |

| Private/NGO Sector | 26.3 | 22.3 | 27.9 | 0.76 (0.61–0.96); 0.022 | 1.05 (0.85–1.31); 0.604 |

|

| |||||

| Plan to migrate in the next 2.5 years † ┼ | |||||

| Yes | 32.6 | 36.1 | 36.6 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| No | 67.4 | 63.9 | 63.4 | 0.81 (0.67–0.99); 0.046 | 0.76 (0.62–0.92); 0.007 |

Variables adjusted in multivariable model of predictors of first-time HIV testing (age, gender, occupation, migration, sex partner, children under care, source of medical care)

Variables adjusted in multivariable model of predictors of repeat HIV testing (age, gender, education, occupation, migration, sex partner, children under care, married, received income)

Bolded findings reflect statistically significant results (p<0.05).

Table 3b.

Behavioral factors associated with first-time and repeat HIV testing compared to no HIV testing among men and women in Soweto, South Africa (N=3416)

| Proportion reporting HIV testing, % | Adjusted odds ratio, AOR (95% CI); p- value*† | Adjusted odds ratio, AOR (95% CI); p- value*┼ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral variables | No HIV testing (N=1756) | First- time HIV testing (N=699) | Repeat HIV testing (N=961) | First-time HIV testing vs. no HIV testing | Repeat HIV testing vs. no HIV testing |

| Ever used alcohol | |||||

| Yes | 71.9 | 67.2 | 63.7 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| No | 28.1 | 32.8 | 36.3 | 0.91 (0.74–1.13); 0.423 | 0.86 (0.70–1.05); 0.158 |

|

| |||||

| Ever used drugs | |||||

| Yes | 15.8 | 10.4 | 8.3 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| No | 84.2 | 89.6 | 91.7 | 0.87 (0.64–1.18); 0.391 | 0.81 (0.59–1.11); 0.207 |

|

| |||||

| Ever had vaginal sex | |||||

| No | 17.8 | 5.9 | 2.9 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 82.2 | 94.1 | 97.1 | 2.86 (1.95–4.19); <0.0001 | 4.03 (2.57–6.30); <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Ever had anal sex | |||||

| No | 92.0 | 91.1 | 89.6 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 8.0 | 8.9 | 10.4 | 1.16 (0.83–1.62); 0.368 | 1.29 (0.94–1.77); 0.108 |

|

| |||||

| # of lifetime sex partners | |||||

| 0 | 20.8 | 8.9 | 7.9 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | 14.8 | 20.5 | 18.0 | 2.30 (1.60–3.31); <0.0001 | 1.73 (1.20–2.49); 0.003 |

| 2 or greater | 64.3 | 70.7 | 74.1 | 2.18 (1.56–3.03); <0.0001 | 2.02 (1.47–2.78); <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Had sex in the last 6 months | |||||

| No | 41.6 | 27.3 | 23.5 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 58.4 | 72.7 | 76.5 | 1.45 (1.13–1.87); 0.003 | 1.33 (1.04–1.71); 0.022 |

|

| |||||

| Frequency of sex in the last 6 months** | |||||

| 1–2 times month | 34.8 | 31.8 | 27.4 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| More than twice a month | 26.5 | 26.7 | 25.5 | 1.00 (0.74–1.35); 0.990 | 0.97 (0.72–1.31); 0.875 |

| 2–4 times a week | 30.3 | 34.6 | 37.3 | 1.01 (0.75–1.35); 0.920 | 1.09 (0.82–1.40); 0.525 |

| ≥4 times a week | 8.4 | 6.9 | 9.8 | 0.72 (0.45–1.15); 0.178 | 1.08 (0.71–1.64); 0.700 |

|

| |||||

| # of sex partners in the last 6 months** | |||||

| 1 | 78.8 | 88.9 | 93.9 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 2 | 12.5 | 6.5 | 3.3 | 0.76 (0.50–1.17); 0.228 | 0.56 (0.34–0.92); 0.024 |

| > 2 | 8.6 | 4.6 | 2.8 | 0.81 (0.49–1.35); 0.436 | 0.75 (0.43–1.29); 0.308 |

|

| |||||

| Condom use in the last 6 months** | |||||

| Inconsistent | 68.8 | 60.9 | 57.4 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Consistent | 31.2 | 39.1 | 41.8 | 1.16 (0.90–1.48); 0.235 | 1.09 (0.86–1.39); 0.437 |

|

| |||||

| Condom use with spouse in the last 1 month** | |||||

| Inconsistent | 92.0 | 90.4 | 82.4 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Consistent | 8.0 | 9.6 | 17.6 | 0.85 (0.52–1.37); 0.510 | 0.73 (0.40–1.33); 0.317 |

|

| |||||

| Condom use with non- spousal partners in the last 1 month** | |||||

| Inconsistent | 71.8 | 71.8 | 72.7 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Consistent | 28.2 | 28.2 | 27.3 | 0.86 (0.63–1.16); 0.336 | 1.02 (0.75–1.39); 0.883 |

|

| |||||

| Forced to have sex in the last 6 months** | |||||

| No | 95.6 | 96.3 | 96.3 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 4.4 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 1.10 (0.61–1.96); 0.744 | 1.08 (0.61–1.91); 0.779 |

|

| |||||

| Ever physically abused by a sex partner | |||||

| No | 94.4 | 89.1 | 86.4 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 5.6 | 10.9 | 13.6 | 1.47 (1.05–2.06); 0.023 | 1.75 (1.27–2.42); 0.001 |

|

| |||||

| Unwanted sexual experience before age 12 | |||||

| No | 96.0 | 94.6 | 94.6 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 4.0 | 5.4 | 5.4 | 1.41 (0.91–2.17); 0.116 | 1.11 (0.72–1.73); 0.617 |

|

| |||||

| Experienced physical violence before age 12 | |||||

| No | 88.9 | 88.4 | 86.9 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 11.1 | 11.6 | 13.1 | 1.31 (0.97–1.76); 0.072 | 1.57 (1.17–2.09); 0.002 |

|

| |||||

| Talked to anyone about HIV/AIDS in lifetime | |||||

| No | 17.0 | 10.6 | 6.9 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 83.0 | 89.3 | 93.1 | 1.91 (1.43–2.55); <0.0001 | 3.22 (2.34–4.43); <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Conversations about HIV/AIDS scale | |||||

| None | 30.2 | 22.3 | 15.9 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Some | 41.3 | 38.9 | 35.5 | 1.39 (1.09–1.77); 0.007 | 1.80 (1.40–2.33); <0.0001 |

| Common | 28.4 | 38.8 | 48.6 | 1.65 (1.28–2.12); <0.0001 | 2.67 (2.07–3.46); <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Stigma scale | |||||

| Low | 25.3 | 24.2 | 29.4 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Intermediate | 50.2 | 50.1 | 47.8 | 1.00 (0.79–1.26); 0.973 | 0.78 (0.62–0.98); 0.032 |

| High | 24.5 | 25.6 | 22.8 | 1.07 (0.82–1.40); 0.593 | 0.80 (0.61–1.04); 0.099 |

|

| |||||

| Social norms scale | |||||

| Unfavorable | 27.1 | 31.4 | 33.2 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Intermediate | 64.0 | 60.0 | 57.8 | 0.79 (0.64–0.98); 0.036 | 0.70 (0.62–0.98); 0.001 |

| Favorable | 8.9 | 8.6 | 9.0 | 0.84 (0.58–1.20); 0.352 | 0.90 (0.63–1.29); 0.588 |

|

| |||||

| Heard of antiretroviral treatment | |||||

| No | 33.0 | 26.1 | 18.0 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 66.9 | 73.8 | 82.0 | 1.37 (1.11–1.69); 0.003 | 2.12 (1.69–2.65); <0.0001 |

Variables adjusted in multivariable model of predictors of first-time HIV testing (age, gender, occupation, migration, sex partner, children under care, source of medical care)

Variables adjusted in multivariable model of predictors of repeat HIV testing (age, gender, education, occupation, migration, sex partner, children under care, married, received income)

Analyzed only on the subset of participants who reported being sexually active in the last 6 months.

Bolded findings reflect statistically significant results (p<0.05).

In regards to sexual behavior, those who had undergone both first-time and repeat HIV testing had a higher odds of ever having had vaginal sex, having ≥1 lifetime sex partners, and having a sex partner in the last 6 months compared to those who reported no HIV testing. Both first-time and repeat acceptors of HIV testing were more likely to have ever talked about HIV/AIDS, to have had conversations about HIV/AIDS with increasing frequency, and to have heard of ART. Both first-time and repeat acceptors were more likely to report having been ever physically abused by a sex partner, and repeat acceptors were also more likely to report having experienced physical violence before the age of 12. Both first-time and repeat HIV testing were not associated with substance use nor condom use.

In order to elucidate differences by gender in uptake of repeated HIV testing, we also conducted analyses stratified by participant sex (men vs. women) (See Appendix). In multivariable analyses, though correlates of repeated HIV testing were broadly similar across gender, we noted differences for the following socio-demographic variables, namely education, occupation, socio-economic status, having children under care; and the following behavioral variables, alcohol use, having had vaginal and anal sex, lifetime number of sex partners, and physical abuse.

HIV testing and disclosure history

Among those who had been tested, most (>80%) reported receiving information about the meaning of a positive or negative HIV test result before they underwent HIV testing and over 90% reported getting their last HIV test result. A high proportion (>85%) reported ever disclosing their HIV test results. On their last HIV test, 6.3% of participants reported a positive HIV test result. Men were more likely to report decreased risk behaviors following HIV testing compared to women, including using condoms more often (40.0% vs. 29.3%; p<0.0001) and reducing number of sex partners (44.1% vs. 24.9%; p<0.0001).

DISCUSSION

The current study conducted among a representative sample of urban South African men and women identified several socio-demographic and behavioral characteristics associated with HIV testing that could assist in the development of future test and treat strategies. It is of great concern that about half of the participants (51%) remained unaware of their HIV status in a hyperendemic setting following expanded public-sector access to HIV care and ART through both the South African government and PEPFAR32. Among those who had not been tested, over a third reported not thinking they were at risk for HIV. HIV testing in the urban population of Soweto was not higher than recent national South African survey data in which about half of the respondents reported past HIV testing16. Younger individuals and students, who are at particularly high risk of HIV acquisition, were less likely to report having tested for HIV16. HIV infections among youth aged 15–24 years represent more than 40% of all infections globally, and 63% reside in sub-Saharan Africa33. Further studies in Africa are needed to examine acceptable youth-specific HIV prevention programs, including school-based interventions and routine testing of youth attending healthcare facilities34, 35, as well as testing in non-clinical settings36.

Men and women who had talked about HIV with increasing frequency were more likely to report having tested for HIV, which also held for repeated HIV testing. An earlier analysis from all regional sites of the current study found that the only variable that was significantly and consistently associated with past HIV testing was frequent conversations about HIV28. Increased communication about HIV may lead to greater acceptance and uptake of testing; in addition, those who are tested for HIV may be more likely to speak openly about HIV14. Further studies are needed to elucidate with whom these conversations occur, the context of these conversations, and the impact on HIV testing. Men and women who had heard of ART were also more likely to report having tested for HIV, as well as repeated HIV testing. This is an interesting finding as the current study was conducted in 2007, which was after the roll-out of the government ART program. HIV testing has since accelerated with the increasing availability of ART37. Although there has been great concern about stigma’s role in impeding testing in South Africa38–40, HIV stigma was not associated with having tested for HIV. It is possible that national prevention campaigns, such as loveLife (www.lofeLife.com) for South African youth, may be linked to wider awareness about HIV and consequent HIV testing14.

Men who were older, employed, and of higher educational and socio-economic status were more likely to report having tested for HIV, which is consistent with earlier data from Zimbabwe and South Africa14, 41. Given what is known about risk behavior among young people, it is of concern that young and unmarried men were less likely to get tested40, 42, 43. Community-based HIV prevention programs in South Africa have been developed to involve men, such as Sonke Gender Justice Network (www.genderjustice.org.za) and Engender Health (www.engenderhealth.org). Further interventions are needed to target young men who may be left out of current public VCT programs, including routine opt-in or opt-out testing of all individuals and the expansion of community-based, barrier-free VCT 40, 44–46.

In sub-Saharan Africa, it has been estimated that nearly 80% of HIV-infected adults are unaware of their status47. This study documents a relatively high level of HIV testing (i.e. close to 50%), which is similar to recent data from Botswana but much higher than rural Zimbabwe40,41. Also, among those who had been tested, most (>90%) reported receiving their test result, which is higher than some earlier data from South Africa14, 38. However, these data suggest that there is still a great need for scaling-up HIV testing in this hyperendemic urban setting. Women were much more likely to report both first-time and repeat HIV testing compared to men, which is different from Ugandan data48, but in accordance with recent South African surveys16. Prevalence studies from South Africa suggest that younger women are four times more likely to be infected with HIV in comparison to men of the same age22, 23. In the current study, women who were married, who had an increasing number of children under their care, and who were of lower socio-economic status had a higher likelihood of HIV testing, which is consistent with previous data43. Pregnancy among young South African women is high with close to a third of 15–19 years olds and nearly two-thirds of 20–24 year olds reporting a past pregnancy23. For many women in this population, HIV testing was likely offered at the time of pregnancy through routine antenatal testing.

Despite high levels of reported sexual risk behavior in this study population27, after controlling for socio-demographic characteristics, our results do not indicate that condom use and number of sex partners are associated with HIV testing. Additionally, these data do not suggest that those who reported repeated HIV testing were more likely to report safer sex. For men and repeat testers, the current study suggests that those who were most risk-averse with the least number of sex partners in the last six months were taking up HIV testing, which is in accordance with some African studies41, 49. Other data from this region have suggested that individuals who accept repeat VCT may be more likely to engage in high-risk sexual behaviors, despite the potential prevention benefits associated with repeat VCT8, 11, 13, 50. Unless the respondent receives a positive test result, VCT may not impact subsequent risk taking12. The current baseline analysis included participants who had already undergone HIV testing as an individual-level behavioral intervention, which may not be adequate to address prevalent high-risk behaviors in the community4. The prevalence of sexual risk behaviors, measured as inconsistent condom use and multiple sex partners, was higher in this urban population than South African national survey data16. In light of the high frequency of sexual risk behaviors, particularly among men, and the lack of an association between HIV testing and sexual risk behaviors, these findings suggest that there is a need for more effective risk reduction counseling as part of HIV testing.

A limitation of this study is we were not able to investigate particular reasons for HIV testing (i.e. separating out whether non-voluntary testing was due to pregnancy vs. requested by a healthcare provider for other diagnostic purposes). Due to the cross-sectional design of the current study, causal or temporal inferences cannot be drawn from the associations. The lack of an association between HIV testing and current sexual risk behaviors may be due to the cross-sectional assessment. Questions regarding substance use and sexual behavior have the potential for misreporting due to recall and social desirability bias, especially in face-to-face interviews. However, surveys were confidential, and no identifiable personal information was collected. This baseline dataset did not involve actual HIV testing, but rather used retrospective self-report. A strength of the current study was a large representative population-based sample with high survey completion rates and very little missing data27, which allowed for greater generalizability and representativeness of these findings. Earlier studies have often relied on clinic-based populations where HIV testers may represent a self-selecting group. The large sample size allowed for assessing relatively rare exposures.

The current study highlights individual-level characteristics that influence the utilization of HIV testing, and found that a number of population sub-groups could be targeted for VCT uptake, particularly youth, students, and men. To date patterns and predictors of HIV testing use have not been fully characterized in resource-limited settings4. As VCT continues to be rapidly scaled-up in South Africa, repeat testers will represent a larger proportion of individuals undergoing VCT, and further research will be needed to examine whether sexual risk behaviors change among repeat testers. Given the continued high prevalence of HIV and plans to expand VCT in South Africa, the current study is timely in emphasizing the need for further targeted efforts to expand HIV testing.

Acknowledgments

This research was sponsored by the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health as a cooperative agreement, through contracts U01MH066687 (Johns Hopkins University – David Celentano, PI); U01MH066688 (Medical University of South Carolina – Michael Sweat, PI); U01MH066701 (University of California, Los Angeles – Thomas J. Coates, PI); and U01MH066702 (University of California, San Francisco – Stephen F. Morin, PI). In addition, this work was supported as HPTN Protocol 043 through contracts U01AI068613 (HPTN Network Laboratory – Susan Eshleman, PI); U01AI068617 (SCHARP – Deborah Donnell, PI); and U01AI068619 (HIV Prevention Trials Network – Sten Vermund, PI) of the Division of AIDS of the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; and by the Office of AIDS Research of the U.S. National Institutes of Health. Views expressed are those of the authors, and not necessarily those of sponsoring agencies.

We thank the communities that partnered with us in conducting this research, and all study participants for their contributions. We also thank study staff and volunteers at all participating institutions for their work and dedication.

APPENDIX

Table 4a.

Socio-demographic factors associated with repeat HIV testing compared to no HIV testing in Soweto, South Africa stratified by sex (N=2717)

| Socio-demographic variables | Men (N=1315) | Women (N=1402) |

|---|---|---|

| Adjusted odds ratio, AOR (95% CI); p-value* | Adjusted odds ratio, AOR (95% CI); p-value* | |

| Age, years ┼ | ||

| 18–23 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 23–28 | 2.06 (1.39–3.06); <0.0001 | 1.94 (1.44–2.62); <0.0001 |

| ≥28 | 2.41 (1.56–3.70); <0.0001 | 1.69 (1.24–2.32); <0.0001 |

|

| ||

| Education, years ┼ | ||

| 7 or below | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 8–12 | 1.59 (0.87–2.91); 0.130 | 1.55 (0.98–2.44); 0.058 |

| ≥12 | 2.84 (1.39–5.81); 0.004 | 1.41 (0.80–2.49); 0.228 |

|

| ||

| Primary occupation ┼ | ||

| Employed | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Unemployed | 0.55 (0.34–0.88); 0.013 | 0.94 (0.70–1.26); 0.693 |

| Student | 0.16 (0.07–0.36); 0.004 | 0.25 (0.16–0.40); <0.0001 |

|

| ||

| Received income in the last year ┼ | ||

| Yes | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| No | 1.31 (0.80–2.16); 0.277 | 1.08 (0.81–1.44); 0.580 |

|

| ||

| Socioeconomic status (SES) | ||

| Low | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Moderate | 1.51 (0.97–2.35); 0.064 | 0.85 (0.61–1.19); 0.357 |

| High | 1.88 (1.15–3.08); 0.011 | 0.70 (0.47–1.03); 0.077 |

|

| ||

| Marital status ┼ | ||

| Single | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Married | 1.46 (0.86–2.47); 0.150 | 1.74 (1.21–2.49); 0.002 |

|

| ||

| Currently has a sex partner ┼ | ||

| Yes | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| No | 0.77 (0.53–1.13); 0.190 | 0.40 (0.30–0.54); <0.0001 |

|

| ||

| Children under care ┼ | ||

| 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | 1.21 (0.87–1.70); 0.250 | 1.86 (1.41–2.46); <0.0001 |

| ≥2 | 1.35 (0.84–2.18); 0.208 | 2.61 (1.84–3.70); <0.0001 |

|

| ||

| Source of medical care when in need | ||

| Public sector | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Traditional system | 0.36 (0.13–1.04); 0.061 | 0.57 (0.22–1.47); 0.251 |

| Private/NGO Sector | 1.36 (0.95–1.94); 0.084 | 0.92 (0.70–1.22); 0.592 |

|

| ||

| Plan to migrate in the next 2.5 years ┼ | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 0.69 (0.50–0.94); 0.021 | 1.00 |

| No | 0.82 (0.64–1.05); 0.132 | |

Variables adjusted in multivariable model of predictors of repeat HIV testing (age, gender, education, occupation, migration, sex partner, children under care, married, received income) 30

Bolded findings reflect statistically significant results (p<0.05).

Table 4b.

Behavioral factors associated with repeat HIV testing compared to no HIV testing in Soweto, South Africa stratified by sex (N=2717)

| Behavioral variables | Men (N=1315) | Women (N=1402) |

|---|---|---|

| Adjusted odds ratio, AOR (95% CI); p-value* | Adjusted odds ratio, AOR (95% CI); p-value* | |

| Ever used alcohol | ||

| Yes | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| No | 0.54 (0.34–0.86); 0.009 | 0.95 (0.74–1.21); 0.692 |

|

| ||

| Ever used drugs | ||

| Yes | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| No | 0.79 (0.55–1.14); 0.219 | 0.76 (0.40–1.44); 0.409 |

|

| ||

| Ever had vaginal sex | ||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 1.51 (0.70–3.26); 0.282 | 5.81 (3.38–10.00); <0.0001 |

|

| ||

| Ever had anal sex | ||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 1.58 (1.01–2.47); 0.044 | 1.07 (0.69–1.65); 0.752 |

|

| ||

| # of lifetime sex partners | ||

| 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 | 0.62 (0.27–1.41); 0.260 | 2.34 (1.53–3.56); <0.0001 |

| 2 or greater | 1.04 (0.62–1.75); 0.867 | 2.72 (1.85–4.01); <0.0001 |

|

| ||

| Had sex in the last 6 months | ||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 1.36 (0.89–2.09); 0.149 | 1.31 (0.96–1.78); 0.081 |

|

| ||

| Frequency of sex in last 6 months** | ||

| 1–2 times month | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| More than twice a month | 1.08 (0.66–1.77); 0.746 | 0.87 (0.59–1.29); 0.517 |

| 2–4 times a week | 1.33 (0.83–2.13); 0.230 | 0.96 (0.66–1.40); 0.851 |

| ≥4 times a week | 1.73 (0.91–3.29); 0.092 | 0.80 (0.47–1.38); 0.437 |

|

| ||

| # of sex partners in the last 6 months** | ||

| 1 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 2 | 0.62 (0.35–1.10); 0.109 | 0.42 (0.15–1.18); 0.104 |

| > 2 | 0.70 (0.37–1.31); 0.268 | 1.86 (0.42–8.30); 0.411 |

|

| ||

| Condom use in the last 6 months** | ||

| Inconsistent | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Consistent | 1.02 (0.68–1.51); 0.920 | 1.12 (0.82–1.52); 0.460 |

|

| ||

| Condom use with spouse in the last 1 month** | ||

| Inconsistent | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Consistent | 1.42 (0.41–4.86); 0.574 | 0.58 (0.28–1.17); 0.131 |

|

| ||

| Condom use with non-spousal partners in the last 1 month** | ||

| Inconsistent | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Consistent | 0.93 (0.56–1.54); 0.783 | 1.08 (0.72–1.61); 0.699 |

|

| ||

| Forced to have sex in the last 6 months** | ||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 1.28 (0.59–2.76); 0.525 | 1.02 (0.44–2.33); 0.955 |

|

| ||

| Ever physically abused by a sex partner | ||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 0.87 (0.39–1.96); 0.752 | 1.99 (1.37–2.88); <0.0001 |

|

| ||

| Unwanted sexual experience before age 12 | ||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 0.90 (0.38–2.11); 0.810 | 1.18 (0.69–2.02); 0.540 |

|

| ||

| Experienced physical violence before age 12 | ||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 1.41 (0.93–2.13); 0.100 | 1.67 (1.10–2.54); 0.015 |

|

| ||

| Talked to anyone about HIV/AIDS in lifetime | ||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 4.19 (2.15–8.18); <0.0001 | 3.13 (2.14–4.58); <0.0001 |

|

| ||

| Conversations about HIV/AIDS scale | ||

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Some | 1.69 (1.08–2.65); 0.021 | 1.93 (1.40–2.65); <0.0001 |

| Common | 2.97 (1.90–4.64); <0.0001 | 2.74 (1.98–3.78); <0.0001 |

|

| ||

| Stigma scale | ||

| Low | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Intermediate | 0.83 (0.58–1.20); 0.342 | 0.75 (0.56–1.00); 0.052 |

| High | 0.78 (0.51–1.19); 0.254 | 0.80 (0.57–1.12); 0.209 |

|

| ||

| Social norms scale | ||

| Unfavorable | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Intermediate | 0.77 (0.54–1.08); 0.138 | 0.67 (0.51–0.88); 0.004 |

| Favorable | 1.03 (0.60–1.77); 0.907 | 0.81 (0.51–1.30); 0.396 |

|

| ||

| Heard of antiretroviral treatment | ||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 1.84 (1.26–2.69); 0.001 | 2.34 (1.76–3.12); <0.0001 |

Variables adjusted in multivariable model of predictors of repeat HIV testing (age, gender, education, occupation, migration, sex partner, children under care, married, received income)

Analyzed only on the subset of participants who reported being sexually active in the last 6 months.

Bolded findings reflect statistically significant results (p<0.05).

Footnotes

Author contributions: KKV and GEG designed the study and wrote the manuscript. KKV with assistance from GdB and MNL did the analyses. GEG and PM oversaw data collection. TJC, GdB, and MNL provided oversight on analysis and manuscript writing.

References

- 1.Dodd P, Garnett GP, Hallett TB. Examining the promise of HIV elimination by ‘test and treat’ in hyperendemic settings. AIDS. 2010;24(5):729–735. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833433fe. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Granich R, Crowley S, Vitoria M, Lo YR, Souteyrand Y, Dye C, Gilks C, Guerma T, De Cock KM, Williams B. Highly active antiretroviral treatment for the prevention of HIV transmission. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2010;12(13):1. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-13-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shorter M, Ostermann J, Crump JA, Tribble AC, Itemba DK, Mgonja A, Mtalo A, Bartlett JA, Shao JF, Schimana W, Thielman NM. Characteristics of HIV voluntary counseling and testing clients before and during care and treatment scale-up in Moshi, Tanzania. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2009;52(5):648–654. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b31a6a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Obermeyer C, Osborn M. The utilization of testing and counseling for HIV: a review of the social and behavioral evidence. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97(10):1762–1774. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.096263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Voluntary HIV-1 Counseling and Testing Efficacy Study Group. Efficacy of voluntary HIV-1 counseling and testing in individuals and couples in Kenya, Tanzania, and Trinidad: a randomized trial. The Lancet. 2000;356:103–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grinstead O, Gregorich SE, Choi KH, Coates T Voluntary HIV-1 Counselling and Testing Efficacy Study Group. Positive and negative life events after counselling and testing: the Voluntary HIV-1 Counselling and Testing Efficacy Study. AIDS. 2001;15(8):1045–1052. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200105250-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Denison J, O’Reilly KR, Schmid GP, Kennedy CE, Sweat MD. HIV voluntary counseling and testing and behavioral risk reduction in developing countries: a meta-analysis, 1990–2005. AIDS and Behavior. 2008;12(3):363–373. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9349-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matambo R, Dauya E, Mutswanga J, Makanza E, Chandiwana S, Mason PR, Butterworth AE, Corbett EL. Voluntary counseling and testing by nurse counselors: what is the role of routine repeated testing after a negative result? Clinical Infectious Disease. 2006;42(4):569–571. doi: 10.1086/499954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacKellar D, Valleroy LA, Secura GM, Bartholow BN, McFarland W, Shehan D, Ford W, LaLota M, Celentano DD, Koblin BA, Torian LV, Perdue TE, Janssen RS Young Men’s Survey Study Group. Repeat HIV testing, risk behaviors, and HIV seroconversion among young men who have sex with men: a call to monitor and improve the practice of prevention. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2002;29(1):76–85. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200201010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fernyak S, Page-Shafer K, Kellogg TA, McFarland W, Katz MH. Risk behaviors and HIV incidence among repeat testers at publicly funded HIV testing sites in San Francisco. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2002;31(1):63–70. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200209010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leaity S, Sherr L, Wells H, Evans A, Miller R, Johnson M, Elford J. Repeat HIV testing: high-risk behaviour or risk reduction strategy? AIDS. 2000;14(5):547–552. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200003310-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weinhardt LS, Carey MP, Johnson BT, Bickman NL. Effects of HIV counseling and testing on sexual risk behavior: a meta-analytic review of published research, 1985–1997. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89(9):1397–1405. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matovu J, Gray RH, Kiwanuka N, Kigozi G, Wabwire-Mangen F, Nalugoda F, Serwadda D, Sewankambo NK, Wawer MJ. Repeat voluntary HIV counseling and testing (VCT), sexual risk behavior and HIV incidence in Rakai, Uganda. AIDS and Behavior. 2007;11(1):71–78. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9170-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacPhail C, Pettifor A, Moyo W, Rees H. Factors associated with HIV testing among sexually active South African youth aged 15–24 years. AIDS Care. 2009;21(4):456–467. doi: 10.1080/09540120802282586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.UNAIDS. UNAIDS Executive Director joins President Zuma to launch national HIV counselling and testing drive in South Africa. [Accessed August 24, 2010]; http://www.unaids.org/en/KnowledgeCentre/Resources/FeatureStories/archive/2010/20100426_MS_SA.asp.

- 16.Human Sciences Research Council. South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence, Behavior, and Communication Survey, 2008: A Turning Tide Among Teenagers? Cape Town, South Africa: HSRC Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rehle T, Hallett TB, Shisana O, Pillay-van Wyk V, Zuma K, Carrara H, Jooste S. A decline in new HIV infections in south africa: estimating HIV incidence from three national HIV surveys in 2002, 2005 and 2008. PLos ONE. 2010;5(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glynn J, Caraël M, Auvert B, Kahindo M, Chege J, Musonda R, Kaona F, Buvé A Study Group on the Heterogeneity of HIV Epidemics in African Cities. Why do young women have a much higher prevalence of HIV than young men? A study in Kisumu, Kenya and Ndola, Zambia. AIDS. 2001;15(Supplement 4):S51–S60. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200108004-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Munguti K, Grosskurth H, Newell J, Senkoro K, Mosha F, Todd J, Mayaud P, Gavyole A, Quigley M, Hayes R. Patterns of sexual behaviour in a rural population in northwestern Tanzania. Social Science and Medicine. 1997;44(10):1553–1561. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halperin D, Epstein H. Concurrent sexual partnerships help to explain Africa’s high HIV prevalence: implications for prevention. Lancet. 2004;364(9428):4–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16606-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eaton L, Flisher AJ, Aarø LE. Unsafe sexual behaviour in South African youth. Social Science and Medicine. 2003;56(1):149–165. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pettifor A, Kleinschmidt I, Levin J, Rees HV, MacPhail C, Madikizela-Hlongwa L, Vermaak K, Napier G, Stevens W, Padian NS. A community-based study to examine the effect of a youth HIV prevention intervention on young people aged 15–24 in South Africa: results of the baseline survey. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 2005;10(10):971–980. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pettifor A, Rees HV, Kleinschmidt I, Steffenson AE, MacPhail C, Hlongwa-Madikizela L, Vermaak K, Padian NS. Young people’s sexual health in South Africa: HIV prevalence and sexual behaviors from a nationally representative household survey. AIDS. 2005;19(14):1525–1534. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000183129.16830.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.April M, Walensky RP, Chang Y, Pitt J, Freedberg KA, Losina E, Paltiel AD, Wood R. HIV testing rates and outcomes in a South African community, 2001–2006: implications for expanded screening policies. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2009;51(3):310–316. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e3181a248e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Statistics South Africa. General Household Survey. Statistics South Africa Pretoria. 2010 April 14;:2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khumalo-Sakutukwa G, Morin SF, Fritz K, Charlebois ED, van Rooyen H, Chingono A, Modiba P, Mrumbi K, Visrutaratna S, Singh B, Sweat M, Celentano DD, Coates TJ NIMH Project Accept Study Team. Project Accept (HPTN 043): a community-based intervention to reduce HIV incidence in populations at risk for HIV in sub-Saharan Africa and Thailand. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2008;49(4):422–431. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31818a6cb5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Genberg B, Kulich M, Kawichai S, Modiba P, Chingono A, Kilonzo GP, Richter L, Pettifor A, Sweat M, Celentano DD NIMH Project Accept Study Team (HPTN 043) HIV risk behaviors in sub-Saharan Africa and Northern Thailand: baseline behavioral data from Project Accept. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2008;49(3):309–319. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181893ed0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hendriksen E, Hlubinka D, Chariyalertsak S, Chingono A, Gray G, Mbwambo J, Richter L, Kulich M, Coates TJ. Keep talking about it: HIV/AIDS-related communication and prior HIV testing in Tanzania, Zimbabwe, South Africa, and Thailand. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13(6):1213–1221. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9608-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Genberg B, Hlavka Z, Konda KA, Maman S, Chariyalertsak S, Chingono A, Mbwambo J, Modiba P, Van Rooyen H, Celentano DD. A comparison of HIV/AIDS-related stigma in four countries: negative attitudes and perceived acts of discrimination towards people living with HIV/AIDS. Social Science and Medicine. 2009;68(12):2279–227. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boera T, Weir SS. Integrating Demographic and Epidemiological Approaches to Research on HIV/AIDS:The Proximate-Determinants Framework. Journal of Infectious Disease. 2005;191(Supplement 1):S61–S67. doi: 10.1086/425282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lewis J, Donnelly CA, Mare P, Mupambireyi Z, Garnett GP, Gregson S. Evaluating the proximate determinants framework for HIV infection in rural Zimbabwe. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2007;83(Supplement 1):i61–i69. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.023671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walensky R, Kuritzkes DR. The Impact of The President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPfAR) beyond HIV and Why It Remains Essential. Clinical Infectious Disease. 2010;50(2):272–275. doi: 10.1086/649214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilson C, Wright PF, Safrit JT, Rudy B. Epidemiology of HIV infection and risk in adolescents and youth. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2010;54(Supplement 1):S5–S6. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181e243a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harrison A, Newell ML, Imrie J, Hoddinott G. HIV prevention for South African youth: which interventions work? A systematic review of current evidence. BMC Public Health. 2010;26(10):102. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gallant M, Maticka-Tyndale E. School-based HIV prevention programmes for African youth. Social Science and Medicine. 2008;58(7):1337–1351. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00331-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chirawu P, Langhaug L, Mavhu W, Pascoe S, Dirawo J, Cowan F. Acceptability and challenges of implementing voluntary counselling and testing (VCT) in rural Zimbabwe: evidence from the Regai Dzive Shiri Project. AIDS Care. 2008;22(1):81–88. doi: 10.1080/09540120903012577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Warwick Z. The influence of antiretroviral therapy on the uptake of HIV testing in Tutume, Botswana. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 2006;17(7):479–481. doi: 10.1258/095646206777689189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kalichman S, Simbayi LC. HIV testing attitudes, AIDS stigma, and voluntary HIV counseling and testing in a black township in Cape Town, South Africa. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2003;9:442–447. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.6.442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parker R, Aggleton P. HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: a conceptual framework and implications for action. Social Science and Medicine. 2003;57(1):13–24. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weiser S, Heisler M, Leiter K, Percy-de Korte F, Tlou S, DeMonner S, Phaladze N, Bangsberg DR, Iacopino V. Routine HIV testing in Botswana: a population-based study on attitudes, practices, and human rights concerns. PLoS Medicine. 2006;3(7):e261. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sherr L, Lopman B, Kakowa M, Dube S, Chawira G, Nyamukapa C, Oberzaucher N, Cremin I, Gregson S. Voluntary counselling and testing: uptake, impact on sexual behaviour, and HIV incidence in a rural Zimbabwean cohort. AIDS. 2007;21(7):851–860. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32805e8711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bassett I, Giddy J, Wang B, Lu Z, Losina E, Freedberg KA, Walensky RP. Routine, voluntary HIV testing in Durban, South Africa: correlates of HIV infection. HIV Medicine. 2008;9(10):863–867. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2008.00635.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matovu J, Gray RH, Makumbi F, Wawer MJ, Serwadda D, Kigozi G, Sewankambo NK, Nalugoda F. Voluntary HIV counseling and testing acceptance, sexual risk behavior and HIV incidence in Rakai, Uganda. AIDS. 2005;19(5):503–511. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000162339.43310.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paltiel A, Walensky RP, Schackman BR, Seage GR, 3rd, Mercincavage LM, Weinstein MC, Freedberg KA. Expanded HIV screening in the United States: effect on clinical outcomes, HIV transmission, and costs. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2006;145(11):797–806. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-11-200612050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morin S, Khumulo-Sakutukwa G, Charlebois ED, Routh J, Fritz K, Lane T, Vaki T, Fiamma A, Coates TJ. Removing barriers to knowing HIV status: same-day mobile HIV testing in Zimbabwe. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2006;41(2):218–224. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000179455.01068.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Steen T, Seipone K, Gomez Fde L, Anderson MG, Kejelepula M, Keapoletswe K, Moffat HJ. Two and a half years of routine HIV testing in Botswana. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2007;44(4):484–488. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318030ffa9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bunnell R, Opio A, Musinguzi J, Kirungi W, Ekwaru P, Mishra V, Hladik W, Kafuko J, Madraa E, Mermin J. HIV transmission risk behavior among HIV-infected adults in Uganda: results of a nationally representative survey. AIDS. 2008;22(5):617–624. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f56b53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nyblade L, Menken J, Wawer MJ, Sewankambo NK, Serwadda D, Makumbi F, Lutalo T, Gray RH. Population-based HIV testing and counseling in rural Uganda: participation and risk characteristics. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2001;28(5):463–470. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200112150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gage A, Ali D. Factors associated with self-reported HIV testing among men in Uganda. AIDS Care. 2005;17(2):153–165. doi: 10.1080/09540120512331325635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ryder K, Haubrich DJ, Callà D, Myers T, Burchell AN, Calzavara L. Psychosocial impact of repeat HIV-negative testing: a follow-up study. AIDS and Behavior. 2005;9(4):459–464. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9032-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]