Abstract

Cytosine modification by AdoMet–dependent DNA methyltransferases is part of an epigenetic regulatory network in vertebrates. Here we show that, in the absence of AdoMet, bacterial cytosine-5 methyltransferases can catalyze condensation of aliphatic thiols and selenols to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in DNA yielding 5-chalcogenomethyl derivatives. These new atypical reactions open new ways for sequence-specific derivatization and analysis of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine, a recently discovered nucleobase in mammalian DNA

Keywords: HhaI cytosine-5 methyltransferase, 5-hydroxymethylcytosine, nucleophilic addition, DNA labeling, epigenetics, enzyme mechanism

Modification of cytosine by S-adenosylmethionine-dependent DNA methyltransferases is part of intricate epigenetic regulation in vertebrates. DNA cytosine-5 methyltransferases (C5-MTase) catalyze the transfer of a methyl group from S-adenosyl-L-methionine (AdoMet or SAM, 2)[1] to the cytosine (1) residue in CpG dinucleotides. Recent studies of genomic DNA from mouse embryonic stem cells, neurons and the brain found that a substantial fraction of 5-methylcytosine (3) in CG sequences is converted to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (hmC, 5) by the action of 2-oxoglutarate- and Fe+2-dependent oxygenases of the TET family.[2-6] As interactions of the 5-methyl- and 5-hydroxymethyl groups with cellular proteins in DNA are distinct,[7, 8] hmC residues may play an independent role in yet unknown epigenetic pathways during embryonic development, brain functioning and cancer progression. However, further studies of these intriguing phenomena are hampered by the lack of efficient analytical techniques for mapping hmC residues in the genome.[8] Here we find that C5-MTases can direct condensation of exogenous thiols and selenols to hmC in DNA yielding corresponding 5-chalcogenomethyl derivatives, which opens new ways for sequence-specific derivatization and analysis of this newly discovered epigenetic mark in mammalian DNA.

Production of hmC and its homologs in vitro has recently been demonstrated via methyltransferase-directed addition of exogenous aliphatic aldehydes, such as formaldehyde (4), to cytosine;[9] it was also found that DNA C5-MTase are capable of removing the 5-hydroxymethyl group from their target residues in vitro. The natural methylation by C5-MTases proceeds via direct transfer of the sulfonium-bound methyl group from SAM onto the C5 position of the cytosine ring which is activated by nucleophilic addition of a conserved cysteine residue in the enzyme to the 6-position of the ring (Scheme 1a).[10-12]

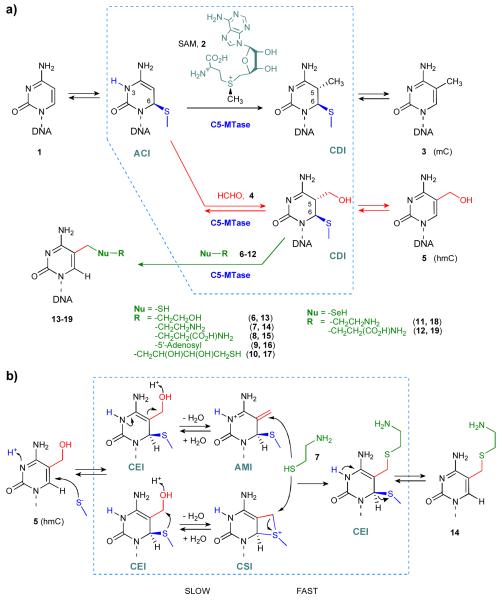

Scheme 1.

Transformations of a target residue by DNA cytosine-5 methyltransferases. a) Biological methylations by C5-MTases occur via an SN2 reaction between an activated cytosine intermediate (ACI) and cofactor SAM (2) to give a covalent 5,6-dihydrocytosine intermediate (CDI) and then 5-methylcytosine (mC, 3). The activated cytosine can also participate in reversible addition reactions (red-colored route) with formaldehyde (4) yielding 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5, hmC). The latter compound, including hmC residues in natural DNA, can undergo further methyltransferase-directed condensation (green-colored route) with thiol or selenol reagents (6–12) to give stable 5-alkylchalcogenomethyl-derivatives (13–19). b) Proposed mechanism of nucleophile condensation at the target hmC (5) residue catalyzed by a C5-MTase. The reaction is thought to proceed via a covalent enamine intermediate (CEI) followed by either a highly active 5-methylene intermediate (AMI) or a bicyclic sulfonium intermediate (CSI), which would then undergo a fast addition of a nucleophilic reagent such as (7). The C5-MTase and its catalytic moieties are shown in blue, and boxed areas denote species and reactions within the catalytic center of the enzyme.

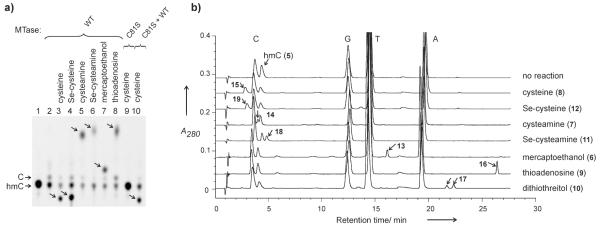

To better understand the mechanism of these novel enzymatic reactions, we examined the behavior of hmC residues in DNA duplexes (see Table 1) in the presence of C5-MTases under a variety of reaction conditions. Remarkably, we found that the presence of an exogenous thiol compound such as 2-mercaptoethanol (6), cysteamine (7) or L-cysteine (8) at millimolar concentrations led to the appearance of a new product at the expense of the original hmC (Figure 1). ESI-MS and UV spectral analyses of the new compounds show that the thiol replaces a hydroxyl group in the hmC residue, and the sulphur atom is directly attached to the nucleoside (Supporting Information, Table S1, Figures S1 and S2). Taking into account that substrates containing C or mC at the target position were completely inert in the reaction (data not shown), and based on the documented reactivity of the 5-hydroxymethyl group towards a variety of nucleophiles,[7, 13, 14] we presumed that the thiol addition occurs at the 5-hydroxymethyl group yielding 5-(2-hydroxyethyl)thiomethylcytosine (13), 5-(2-aminoethyl)thiomethylcytosine (14) and S-(5-methylcytosinyl)-L-cysteine (15) residues in DNA, respectively (Scheme 1). The identity of the isolated nucleoside 13 was confirmed by direct chromatographic comparison of its nitrous acid deamination product with a chemically synthesized 5-(2-hydroxyethyl)thiomethyl-2′-deoxyuridine 22 (Supporting Information, Figure S3). Similar reactivity but even at lower concentrations was observed (Figure 1) with corresponding selenols such as selenocysteamine 11 and L-selenocysteine 12. 5′-deoxy-5′-thioadenosine 10, which can be regarded as a simple cofactor-mimic due to a potential anchoring interaction of the adenosine moiety with the enzyme, was also reactive at submilllimolar concentrations. Other types of nucleophiles such as hydrazine, p-nitrophenol, phenol, methanol, sodium sulfide, sodium azide, potassium bromide or sodium iodide showed no detectable reaction in our hands.

Table 1.

Structure of short hmC-containing duplex substrates

| Sequence [a] 5′-… 3′-… |

Short name |

|---|---|

| TAATAATGhGCTAATAATAATAAT ATTATTACGhGATTATTATTATTA |

GhGC/ GhGC |

| TAGAGTATGATGMGCTGACCCACAACATCCG ATCTCATACTACGHGACTGGGTGTTGTAGGC |

G*HGC/ GMGC |

| TCGGATGTTGTGGGTCAGhGCATGATAGTGTA AGCCTACAACACCCAGTCGMGTACTATCACAT |

G*hG*C/ GMGC |

M, 5-methylcytosine; H, 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5) (synthetically incorporated); h, 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (introduced by enzymatic hydroxymethylation of GCGC/GCGC with formaldehyde and M.HhaI). M.HhaI/M.SssI target sites are highlighted, target nucleotides are underlined, polymerase-extended nucleotides are italicized, 33P-labeled cytosine nucleotides are shown boldface.

Figure 1.

Methyltransferase-directed coupling of thiols and selenols to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine residues in DNA. a) TLC analysis of modified [33P]-labeled hmC nucleotide. DNA containing hmC at the target site of M.HhaI was treated with 12 mM L-cysteine, 12 mM L-selenocysteine, 12 mM cysteamine, 12 mM selenocysteamine, 150 mM 2-mercaptoethanol or 0.5 mM 5′-thio-5′-deoxyadenosine in the presence of 200 nM M.HhaI (WT, catalytic C81S mutant, or both) for 1.5 hours at room temperature. Modified DNAs were digested to 5′-mononucleotides, analyzed by TLC and autoradiographed. b) Reversed-phase HPLC analysis of modified 2′-deoxynucleosides. 13 μM GhGC/GhGC duplex was treated with an exogenous reagent as above (50 mM L-cysteine, 50 mM L-selenocysteine, 12 mM cysteamine, 12 mM selenocysteamine, 0.5 mM 5′-thio-5′-deoxyadenosine, 500 mM 2-mercaptoethanol or 50 mM DTT) in the presence of 13 μM M.HhaI for 1 hour at room temperature. Modified DNAs were digested to nucleosides and analyzed by HPLC-MS. Small arrows point at peaks corresponding to modified nucleosides.

Besides M.HhaI, another bacterial C5-MTase, M.SssI, was examined and also showed clearly detectable catalytic activity at its target sites (Supporting Information, Figure S4). The generality of this phenomenon indicates that one role of the enzyme is obviously to direct the reaction by flipping out and exposing in the catalytic centre a residue that occurs at its target position.[11] Moreover, we find that the reaction requires the presence of the catalytic cysteine residue in the enzyme (Figure 1a) suggesting a covalent reaction intermediate (Scheme 1). The most straightforward mechanism is a direct SN2 attack of the nucleophile at the protonated 5-hydroxymethyl group. However, this mechanism does not agree with our finding that the rate of adduct formation is fairly independent of whether a thiol or corresponding selenol was used in the reaction. On the other hand, a seleno-product always prevailed over a thio-product even in the presence of an excess amount of thiol (Supporting Information, Figure S5 and S6). These observations clearly point to a mechanism in which the formation of an active intermediate is the slow rate-limiting step, while the relative strength of the nucleophile determines the nature of the final product. Based on previously proposed mechanisms for thymidylate synthase[15] and deoxycytidylate hydroxymethylase,[16] one could assume that the reaction proceeds via an acid-assisted dehydration at the 5-hydroxymethyl group to give a highly electrophilic 5-methylene intermediate (activated methylene intermediate, AMI) (Scheme 1b). However, this high energy exomethylene compound could in principle be avoided by an intramolecular attack of the enzyme-borne C6-bound sulphur atom onto the protonated 5-hydroxymethyl group, which would give a bicyclic sulfonium intermediate (CSI) containing an additional four-membered thietane ring. This route requires a substantial degree of conformational plasticity in the active site for the catalytic sulphur atom to approach the exocyclic target. Such conformational flexibility can be predicted from molecular dynamics studies of M.HhaI,[17] but whether the proposed bicyclic structure is well compatible with the active sites of other C5-MTases[11] and related enzymes (e.g. thymidylate synthase, deoxycytidylate hydroxymethylase) remains to be determined. In both cases, subsequent addition/attack of a nucleophile will readily give the observed product, whereas the addition of water will reverse it to the original hydroxymethylated cytosine.

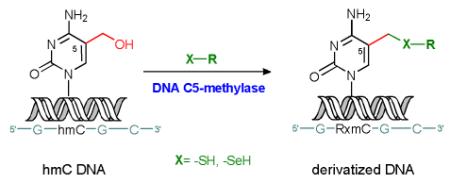

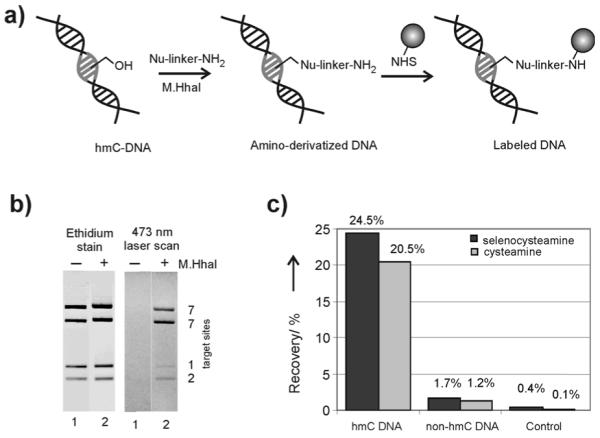

The described novel reactions of C5-MTases to catalyze the condensation of non-cofactor-like compounds to the exocyclic hydroxymethyl group of modified cytosine provide another particularly spectacular example of catalytic versatility of these cofactor-dependent enzymes.[9] Moreover, the reactions occur under mild conditions and retain high sequence- and base-specificity characteristic of bacterial DNA MTases, which offers new ways for sequence-specific derivatization and labeling of DNA. For instance, the cysteine condensation product 15 contains an aliphatic primary amino group (Scheme 1), and we thus examined if this or similar modifications can be exploited as chemical anchors for covalent attachment of reporter groups to DNA (proof of principle, see Figure 2a). For this, plasmid pUC19 DNA that was previously 5-hydroxymethylated at the target cytosine residue was treated with L-cysteine in the presence of M.HhaI and then labeled with fluorescein by treatment with an NHS-ester. The fluorescence intensity distribution in four pUC19-FspBI fragments was consistent with the positions and numbers of the HhaI sites in the original plasmid (Figure 2b). Moreover, since the MTase-directed condensation of nucleophiles is not possible at 5-methylated and unmodified cytosine, the derivatization reaction is well suited to query the hydroxymethylation status of CG sites in mammalian genomic DNA. This can be easily achieved by combining cysteamine or selenocysteamine addition with amino-selective biotinylation. Such labeled DNA is selectively retained on streptavidine beads, and the enriched hmC fractions can then be analyzed by qPCR (Figure 2c), DNA microarrays or sequencing (manuscript in preparation). The above examples demonstrate a unique potential of the new chemo-enzymatic approach for genome-wide mapping of epigenetic cytosine modifications in DNA.

Figure 2.

Sequence-specific covalent derivatization and labeling of hmC-containing DNA. a) General scheme for selective derivatization and labeling of hmC-containing DNA with a reporter group (shown as a ball). DNA bases in the HhaI target site are shown as grey sticks. b) Fluorescent labeling of pUC19 plasmid that contained hmC residues at the HhaI target sites. The DNA was amino-derivatized by treatment with L-cysteine in the presence of M.HhaI, derivatized DNA was labeled with fluorescein N-hydroxysuccinimidyl ester, fragmented with R.FspBI and analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. Fluorescein imaging of was performed using a 473 nm laser scanner (right panel), bulk DNA fragments were visualized after staining with ethidium bromide (left panel). Lane 1, control with M.HhaI omitted. c) A mixture of a hmC-containing and non-hmC DNA fragments was treated with selenocysteamine or cysteamine in the presence of M.HhaI (no M.HhaI in Control) followed by labeling with biotin N-hydroxysuccinimidyl ester. Streptavidin-coated magnetic beads were added and then washed to remove unbound DNA. Fragment recovery was determined by on-beads real-time PCR analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

[**] We thank G. Urbanavičiūtė and G. Vainorius for enzyme preparations, and M. Krenevičienė for technical assistance. Thanks are due to S. Tumkevičius, G. Lukinavičius, D. Daujotytė and A. Petronis for fruitful discussions. This work was supported by the Lithuanian State Science and Study Foundation (P-07003), the Research Council of Lithuania (student research fellowship to I.G.), FP7-REGPOT-2009-1 program (project 245721 MoBiLi) and the US National Institutes of Health (1R21HG005758).

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.angewandte.org

Contributor Information

Zita Liutkevičiūtė, Department of Biological DNA Modification Institute of Biotechnology Vilnius University V.A. Graičiūno 8, LT 02241 Vilnius, Lithuania.

Edita Kriukienė, Department of Biological DNA Modification Institute of Biotechnology Vilnius University V.A. Graičiūno 8, LT 02241 Vilnius, Lithuania.

Indrė Grigaitytė, Department of Biological DNA Modification Institute of Biotechnology Vilnius University V.A. Graičiūno 8, LT 02241 Vilnius, Lithuania.

Viktoras Masevičius, Department of Biological DNA Modification Institute of Biotechnology Vilnius University V.A. Graičiūno 8, LT 02241 Vilnius, Lithuania; Faculty of Chemistry Vilnius University Naugarduko 24, LT-03225 Vilnius, Lithuania.

Saulius Klimašauskas, Department of Biological DNA Modification Institute of Biotechnology Vilnius University V.A. Graičiūno 8, LT 02241 Vilnius, Lithuania.

References

- [1].Goll MG, Bestor TH. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2005;74:481–514. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.010904.153721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kriaucionis S, Heintz N. Science. 2009;324:929–930. doi: 10.1126/science.1169786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Tahiliani M, Koh KP, Shen Y, Pastor WA, Bandukwala H, Brudno Y, Agarwal S, Iyer LM, Liu DR, Aravind L, Rao A. Science. 2009;324:930–935. doi: 10.1126/science.1170116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ito S, D’Alessio AC, Taranova OV, Hong K, Sowers LC, Zhang Y. Nature. 2010;466:1129–1133. doi: 10.1038/nature09303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Münzel M, Globisch D, Brückl T, Wagner M, Welzmiller V, Michalakis S, Müller M, Biel M, Carell T. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:5375–5377. doi: 10.1002/anie.201002033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Szwagierczak A, Bultmann S, Schmidt CS, Spada F, Leonhardt H. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e181. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Tardy-Planechaud S, Fujimoto J, Lin SS, Sowers LC. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:553–558. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.3.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Jin S-G, Kadam S, Pfeifer GP. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e125. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Liutkeviciute Z, Lukinavicius G, Masevicius V, Daujotyte D, Klimasauskas S. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:400–402. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Wu JC, Santi DV. J. Biol.Chem. 1987;262:4778–4786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Klimasauskas S, Kumar S, Roberts RJ, Cheng X. Cell. 1994;76:357–369. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90342-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Peräkylä M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:12895–12902. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Cline RE, Fink RM, Fink K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1959;81:2521–2527. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hayatsu H, Shiragami M. Biochemistry. 1979;18:632–637. doi: 10.1021/bi00571a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Barrett JE, Maltby DA, Santi DV, Schultz PG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:449–450. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Graves KL, Butler MM, Hardy LW. Biochemistry. 1992;31:10315–10321. doi: 10.1021/bi00157a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Lau EY, Bruice TC. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;293:9–18. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.