Abstract

Repeated intermittent exposure to psychostimulants was found to produce behavioral sensitization. The present study was designed to establish a mouse model and by which to investigate whether opioidergic system plays a role in methamphetamine-induced behavioral sensitization. Mice injected with 2.5 mg/kg of methamphetamine once a day for 7 consecutive days showed behavioral sensitization after challenge with 0.3125 mg/kg of the drug on day 11, whereas mice injected with a lower daily dose (1.25 mg/kg) did not. Mice received daily injections with either 1.25 or 2.5 mg/kg of methamphetamine showed behavioral sensitization after challenge with 1.25 mg/kg of the drug on days 11, 21, and 28. To investigate the role of opioidergic system in the induction and expression of behavioral sensitization, long-acting but non-selective opioid antagonist naltrexone was administrated prior to the daily injections of and challenge with methamphetamine, respectively. Our results show that the expressions of behavioral sensitization were attenuated by pretreatment with 10 or 20 mg/kg of naltrexone either during the induction period or before methamphetamine challenge when they were tested on days 11 and 21. These results indicate that repeated injection with methamphetamine dose-dependently induced behavioral sensitization in mice, and suggest the involvement of opioid receptors in the induction and expression of methamphetamine-induced behavioral sensitization.

Keywords: Induction and expression of behavioral sensitization, Locomotor activity, Methamphetamine, Naltrexone, Opioid receptors

1. Introduction

Methamphetamine (METH) is a synthetic drug and chemically related to amphetamine (AMPH) but has a higher potential for abuse. AMPH and related compounds mainly elicit impulse-independent release of monoamines from cytosolic stores by reversal of reuptake carrier activity [42]. Continued use of psychostimulants is typically associated with the development of tolerance. However, repeated intermittent exposure to these psychostimulants such as AMPH, METH, and cocaine was found to produce behavioral sensitization, which is characterized by progressive and enduring augmentation of the behavioral effects in response to subsequent exposure to the same dose of the drug [38,39]. The potential clinical relevance of behavioral sensitization has been associated with development of craving in addicts and psychosis that arise from repeated exposure to these psychostimulants [13,39]. The most important characteristic of behavioral sensitization to psychostimulants is long lasting, which persists for months even years after cessation of drug treatment [7,13,38]. Therefore, rearrangement and structural modification of neural networks and circuitry in the CNS must be involved in the development of behavioral sensitization.

The ventral tegmental area (VTA) is the somatodendritic region of the mesolimbic dopamine neurons, whose nerve terminals project primarily to the nucleus accumbens (NAcc), an important structure which has been described to mediate spontaneous and pharmacologically stimulated locomotor activity [9]. The behavioral activating effects of AMPH are thought to depend primarily on its ability to increase dopamine release in the terminal regions of the mesoaccumbens and neostriatum [16]. In addition, by regulating dopamine release in the midbrain, glutamate also plays an important role in regulation of motor activity [32]. Therefore, the majority of studies related to behavioral sensitization were focused on dopaminergic and glutamatergic systems. Neuroadaptations in the VTA and NAcc are now believed to be associated with the induction and expression of behavioral sensitization to psychostimulants, respectively [15,51]. An abundance of neuroadaptive phenomena observed during the establishment of behavioral sensitization was occurring in a time-dependent fashion [58], and some of these alterations appear to be vanished at post-treatment periods [54,57]. Therefore, the expression of behavioral sensitization after short-term and long-term periods of abstinence may be dependent on different cellular mechanisms, and other neurotransmitter systems may be involved in and contribute to the expression of behavioral sensitization during the period of abstinence.

Topographic overlaps between opioid and dopamine neurons were found in the VTA, substantia nigra, striatum, and limbic areas, suggesting that there are interactions between these two systems [21,43]. Acute administration of AMPH or METH is known to increase endogenous opioid contents [35], and mesolimbic structures such as VTA and NAcc receive β-endorphin containing fibers [29]. Although opioid agonists had been known to increase the firing rate of dopamine neurons [31] and increase dopamine levels [20] in the VTA, the character of opioidergic system in chronic use of psychostimulants still remains unclear. Numerous studies strongly suggest the involvement of opioidergic system in some effects of AMPH or METH. For example, METH is more toxic in morphine-dependent mice than in normal mice (LD50: 20.6 mg/kg versus 43.2 mg/kg) [10]. METH-induced conditioned place preference was found to be additively enhanced by co-administration with morphine [30], but inhibited by pretreatment with opioid receptor antagonist [49]. In various laboratory animal species, specific opioid receptor antagonist naloxone was found to decrease both AMPH-induced locomotor activity and AMPH-induced increase in extracellular levels of dopamine [12,41]. Moreover, morphine given alone not merely increases locomotor activity, but cross-sensitizes the behavioral effects to direct dopamine agonist, apomorphine, and indirect dopamine agonist, AMPH or METH [10,14,50]. These findings provided us an interest to determine whether opioidergic system is involved in the chronic actions of METH. Therefore, the present study was designed to investigate the role of opioidergic system in METH-induced behavioral sensitization. This may lead not only to a better understanding of how this drug affects the behavior, but also to a better understanding of the underlying interactions between neurotransmitter systems.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals

Male NIH Swiss mice (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN), weighing 20–25 g at the beginning of the experiment were used. Upon arrival, mice were housed in groups of four in animal colony room on a 12 h light–dark cycle, and at constant temperature (22 ± 2 °C). Before any treatment, mice were maintained in the colony room for at least 7 days without disturbance. Food and water were available ad libitum except during the behavioral testing. All procedures for animal handling and experiments were approved by Institutional Animal Care Committee of the University of Mississippi Medical Center, and performed in compliance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

2.2. Drug administration

Although extravascular routes of administrations such as intraperitoneal (i.p.) or subcutaneous injection do not resemble those preferred by human drug abusers (intravenous injection and smoking), they are more convenient and accurate for repeated drug administration into small size animals such as mice. Therefore, i.p. injection was used to administer METH or naltrexone (NAT) into mice in this study. METH hydrochloride and NAT hydrochloride dihydrate (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) were freshly dissolved in saline before use and injected at a volume of 10 ml/kg of body weight.

2.3. Measurement of locomotor activity

In order to minimize the external, environmental influences, physically identical home cages (28.5 cm × 17.5 cm × 12 cm) without bedding were used as the locomotor arena. On the day of experiment, mice were transferred to the behavioral testing room in their home cages and allowed to acclimatize to the testing room for 60 min undisturbed with food and water. Following the acclimatization period, the mice were placed individually in locomotor arena and habituated in the arena for 60 min. Locomotor activity during the last 30 min of habituation period in the locomotor arena was considered as baseline activity. After the habituation period, mice were injected with saline or METH and their locomotor activities were measured immediately for 120 min. The locomotor activities in 12 mice were monitored simultaneously and measured as the distance traveled in 5 min intervals using a video tracking system (SMART, San Diego Instruments, San Diego, CA), which recorded and analyzed the real time position of the animal. All experiments were performed during the animals' light cycle. The locomotor activity in each mouse was monitored only once with the exception of those to determine the effects of repeated injection of METH.

2.4. Induction and expression of behavioral sensitization

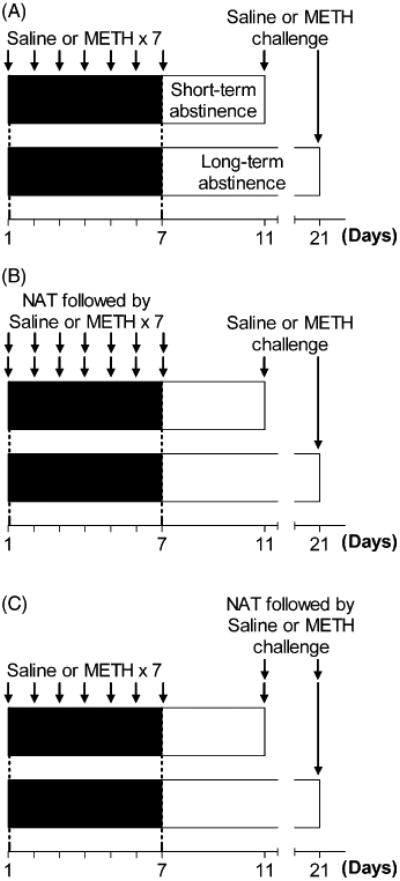

For induction of behavioral sensitization, each mouse was injected i.p. with either METH or saline once daily for 7 consecutive days. Except those for examination of the effects of repeated injection of METH, mice were kept in animal colony room and received all injections in their home cages until the day of measurement of locomotor activity, in order to prevent potential environmental influences. As described in Section 1, the expression of behavioral sensitization after short-term and long-term periods of abstinence may be dependent on different cellular mechanisms. Therefore, in order to investigate the possible differential role of opioid receptors in the expressions of behavioral sensitization after short-term and long-term periods of abstinence, locomotor response to METH challenge was determined on days 11 and 21, 4 and 14 days after repeated injection of METH, respectively (Fig. 1A). Locomotor activity was measured as described above. All mice were challenged with METH only once.

Fig. 1.

Experimental protocol. For induction of behavioral sensitization, mice were injected with saline or METH once a day for 7 consecutive days in their home cages. The expressions of behavioral sensitization after short-term and long-term abstinence from METH were tested in locomotor arena on days 11 and 21, respectively (A). To investigate the involvement of opioid receptors in the induction of behavioral sensitization, NAT was administered 60 min prior to the daily injections of saline or METH, and the expressions of behavioral sensitization were tested on days 11 and 21 in the absence of NAT (B). To investigate the involvement of opioid receptors in the expression of sensitization, NAT was administered 60 min prior to saline or METH challenge (C).

2.5. NAT treatment

To investigate the effects of blockade of opioid receptors on the induction of behavioral sensitization, non-selective opioid receptor antagonist NAT was administered 60 min prior to the daily injections of saline or METH during the induction period (days 1–7; Fig. 1B) for the purpose of preventing the possible drug interactions. To investigate the effects of blockade of opioid receptors on the expression of behavioral sensitization, NAT was administered 60 min prior to saline or METH challenge on the day of behavioral testing (days 11 and 21; Fig. 1C) with the same consideration.

2.6. Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SigmaStat 3.0 (SPSS Science, Rochester, MN). Data are expressed as mean ± standard errors of the mean (S.E.M.). When the effects of treatment of various doses of a drug on the locomotor response were measured at a fixed time point, statistical analysis was done by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by post-hoc Student–Newman–Keuls multiple comparison tests. In the experiment in which the effects of repeated injection of saline or METH on the locomotor response were assessed across days, one-way repeated measures ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post-tests were used. The effects of NAT on the induction or expression of METH-induced behavioral sensitization were analyzed by two-way ANOVA (METH×NAT) followed by Bonferroni post-tests.

3. Results

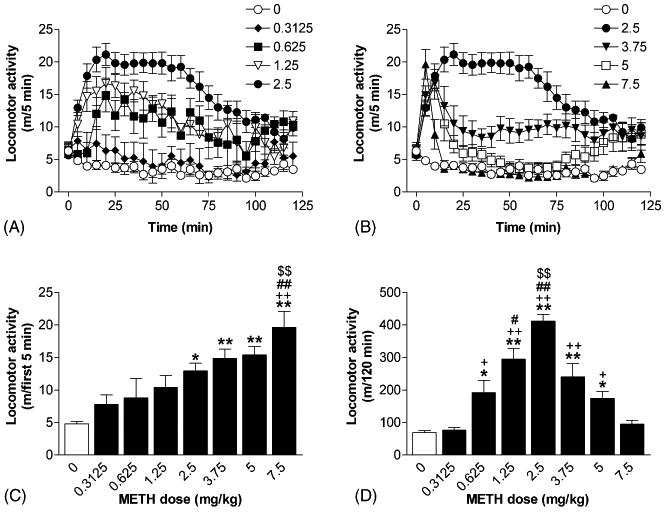

3.1. Dose effects of acute injection of METH on locomotor activity in mice

In order to establish a METH-induced behavioral sensitization model in mice, we first determined the dose effects of acute injection of the drug on locomotor activity in mice. A maximal dose of 7.5 mg/kg of METH was used in this experiment, since it was reported that 10 mg/kg (i.p.) of METH was too high, and animals died before the end of experiments [44]. Fig. 2A and B show the temporal profiles of locomotor activity expressed by mice treated with 0 (saline), 0.3125, 0.625, 1.25, 2.5, 3.75, 5, and 7.5 mg/kg of METH during the 120 min period of testing (m/5 min). Although METH dose-dependently increased locomotor activity in mice during the first 5 min after the injection (F[7, 32] = 7.08, P < 0.001; Fig. 2C), mice treated with higher doses of the drug (3.75, 5.0, or 7.5 mg/kg) exhibited significant stereotypic behaviors (e.g. rearing and grooming; data not shown) and locomotor activities returned to near basal level 20 min after the injection. METH, 2.5 mg/kg, induced sustained elevation in locomotor activity and this effect lasted for at least 60 min. A dose of 0.3125 mg/kg of METH had no effect while 2.5 mg/kg of the drug caused a maximal response during the entire 120 min period of testing (F[7, 32] = 21.84, P < 0.001; Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Dose effects of acute injection of METH on locomotor activity in mice. Temporal profiles of locomotor activity in mice induced by 0 (saline), 0.3125, 0.625, 1.25, 2.5 mg/kg (A), 3.75, 5, and 7.5 mg/kg (B) of METH. Dose–response of METH for locomotor activities during the first 5 min and the entire 120 min period of testing after drug injection are summarized in (C) and (D), respectively. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. (n = 5). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, compared with the response induced by saline; +P < 0.05, ++P < 0.01, compared with the response induced by the dose of 0.3125 mg/kg; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, compared with the response induced by the dose of 0.625 mg/kg; $$P < 0.01, compared with the response induced by the dose of 1.25 mg/kg, according to Student–Newman–Keuls multiple comparison test after a one-way ANOVA.

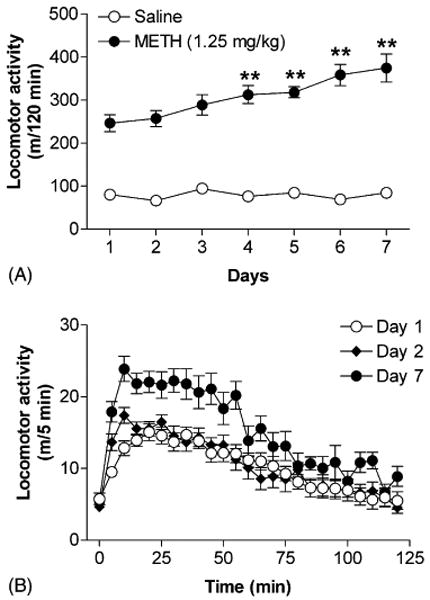

3.2. Effects of repeated injection of METH on locomotor activity in mice

Next, we examined the effects of repeated injection of METH on the changes of locomotor response to the same dose of the drug. A previous study in mice has suggested that an interdose interval of 24 h or longer is required for the induction of behavioral sensitization to METH, cocaine, and morphine [23]. Therefore, the locomotor activities after saline or METH injection were measured once a day for 7 days. According to our previous experiment, a sub-maximal stimulatory dose (1.25 mg/kg) of METH was used in this experiment for the purpose of optimizing the observation of sensitization that may be obscured by the saturation of locomotor activity induced by higher dose of the drug. Repeated injection with 1.25 mg/kg of METH had no effect on baseline activity (data not shown). One-way repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant effect of METH treatment (F[6, 60] = 44.47, P < 0.001). On days 4–7, METH-induced locomotor responses were significantly higher than those of the same group of mice on day 1 (Fig. 3A), suggesting the development of behavioral sensitization. The sensitizing effects of repeated injection of METH also reduced the onset of locomotor response of the same dose of the drug, which was observed after a single injection on day 2 (Fig. 3B). Repeated injection with saline had no effect on locomotor activity in mice on any given day (Fig. 3A). Based on these results, the treatment regimen of METH (i.p. injections, once daily for 7 consecutive days) was used to induce behavioral sensitization in the following experiments.

Fig. 3.

Effects of repeated injection of METH on locomotor activity in mice. Locomotor activities induced by daily injections of saline or 1.25 mg/kg of METH during the entire 120 min period of testing (A). Temporal profiles of locomotor activity in mice induced by 1.25 mg/kg of METH on days 1, 2, and 7 (B). Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. (n = 8–11). **P < 0.01, compared with the response in the same group of mice on day 1, according to Dunnett's post-tests after a one-way repeated measures ANOVA.

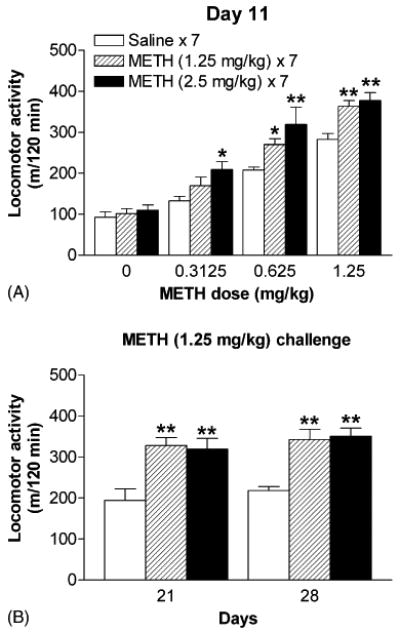

3.3. Effects of METH on the induction and expression of behavioral sensitization

To obtain an optimal dose of METH for the induction of behavioral sensitization, sub-maximal (1.25 mg/kg) and maximal (2.5 mg/kg) doses of METH were used according to the dose–response experiment. Specific environmental context associated with drug administration is considered to be an important experimental factor for the induction of behavioral sensitization [39,45]. However, in order to prevent these context-dependent influences, the induction of behavioral sensitization was conducted in animal's home cages as described in methods. Effects of these doses of METH on the induction of behavioral sensitization were tested on days 11, 21, and 28 by determining the locomotor response of METH challenge. Different doses of METH ranging from 0 (saline) to 1.25 mg/kg were used on day 11 to further obtain an optimal dose of METH for expression of behavioral sensitization.

The first test for sensitization was performed on day 11, 4 days after the drug treatment was stopped. On day 11, mice that had pretreated with 1.25 or 2.5 mg/kg of METH for 7 days did not show any change in locomotor activity in response to saline challenge (Fig. 4A) when it was compared with the response of the corresponding saline-pretreated (saline × 7) group. This finding indicates that no context-dependent locomotion was developed under this experimental condition. Moreover, mice that had pretreated with 2.5 mg/kg of METH for 7 days expressed robust locomotor response even after challenge with 0.3125 mg/kg (Fig. 4A), a very low dose of METH which had no significant acute effect on locomotor activity in mice as showed in Fig. 2D. Next, the expressions of behavioral sensitization were measured on days 21 and 28, 2 and 3 weeks after repeated injection of the drug, respectively. On days 21 and 28, mice that had pretreated with either 1.25 or 2.5 mg/kg of METH exhibited behavioral sensitization after challenge with 1.25 mg/kg of the drug (Fig. 4B). These results demonstrate that behavioral sensitization can be induced more effectively by 2.5 mg/kg of METH than by 1.25 mg/kg of the drug, and the sensitization can last at least 3 weeks after the cessation of the drug treatment. Thus, a dose of 2.5 mg/kg of METH was used to induce while a dose of 1.25 mg/kg of the drug was used to express behavioral sensitization in the following experiments. This was the purpose of optimizing the observation of sensitization that may be decreased by the treatment of opioid receptor antagonist.

Fig. 4.

Effects of METH on the induction and expression of behavioral sensitization. Dose effects of METH on locomotor activity in mice tested on day 11, 4 days after pretreatments with saline, 1.25 or 2.5 mg/kg of METH (A). Locomotor activities in mice induced by 1.25 mg/kg of METH on days 21 and 28, 14 and 21 days after repeated drug pretreatment, respectively (B). Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. (n = 5–8). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, compared with the response of the corresponding saline-pretreated (saline × 7) group, according to Student–Newman–Keuls multiple comparison test after a one-way ANOVA.

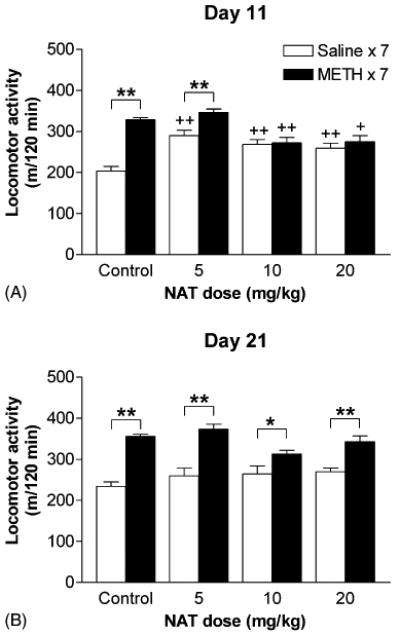

3.4. Effects of NAT on the induction of behavioral sensitization

NAT is a specific, non-selective opioid receptor antagonist but has longer duration of action than naloxone, another commonly used opioid receptor antagonist [28]. To investigate whether opioid receptors participate in the induction of METH-induced behavioral sensitization, mice were injected i.p. with 0 (control), 5, 10 or 20 mg/kg of NAT 60 min prior to the daily injections of saline (saline-pretreated group) or METH (METH-pretreated group) during the induction period (days 1–7). The effects of antagonism of opioid receptors by NAT on the induction of behavioral sensitization were tested after short-term and long-term periods of abstinence on days 11 and 21, respectively, by determining the locomotor response of METH challenge in the absence of the antagonist (Fig. 1B).

Pretreatment with NAT during the induction period had no effect on baseline activity in mice of any group (data not shown). Two-way ANOVA (METH×NAT) revealed significant effects for locomotor responses on days 11 (METH: F[1, 68] = 38, P < 0.001; NAT: F[3, 68] = 9.96, P < 0.001; interaction: F[3, 68] = 11.29, P < 0.001) and 21 (METH: F[1, 82] = 90.19, P < 0.001; interaction: F[3, 82] = 3.61, P = 0.017). Compared with the response of the corresponding control group, pretreatment with NAT significantly enhanced the locomotor response of saline-pretreated mice (saline × 7, open bars in figures) to METH challenge when tested on day 11 (Fig. 5A), but had no effect when tested on day 21 (Fig. 5B). In contrast, pretreatment with higher doses (10 or 20 mg/kg) of NAT suppressed the locomotor response of METH-pretreated mice (METH × 7, closed bars in figures) to METH challenge when tested on day 11 (Fig. 5A), but had no effect when tested on day 21 (Fig. 5B). Compared with the response of the corresponding saline-pretreated group, METH-pretreated mice injected with 10 or 20 mg/kg of NAT during the induction period did not express behavioral sensitization when tested on day 11 (Fig. 5A) but showed some degree of behavioral sensitization when tested on day 21 (Fig. 5B). However, when the data were expressed as percentage of the corresponding saline-pretreated group, pretreatment with 10 or 20 mg/kg of NAT still significantly suppressed the magnitude of sensitization on day 21 (Table 1). These findings indicate that 10 or 20 mg/kg of NAT blocked the induction of sensitization to locomotor stimulating effect of METH.

Fig. 5.

Dose effects of NAT on the induction of behavioral sensitization. During the induction period, mice were pretreated with 0 (control), 5, 10, or 20 mg/kg of NAT prior to daily injections of saline (saline × 7) or 2.5 mg/kg of METH (METH × 7). Effects of NAT on the induction of behavioral sensitization were tested on days 11 (A) and 21 (B), respectively, by determining the locomotor activities in mice induced by 1.25 mg/kg of METH challenge in the absence of the antagonist. Data are expressed as total distance traveled (mean ± S.E.M.) for the entire 120 min period of testing (n = 8–12). +P < 0.05, ++P < 0.01, compared with the response of the corresponding control group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, compared with the response of the corresponding saline-pretreated (saline × 7) group, according to Bonferroni post-tests after a two-way ANOVA.

Table 1. Effects of pretreatment with NAT during the induction period on magnitude of behavioral sensitization.

| Control | NAT (10 mg/kg) | NAT (20 mg/kg) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Day 11 | 162 ± 3 (n = 10) | 101 ± 5** (n = 9) | 106 ± 6** (n = 8) |

| Day 21 | 152 ± 2 (n = 12) | 118 ± 4** (n = 12) | 127 ± 5** (n = 9) |

Locomotor activity induced by 1.25 mg/kg of METH challenge in METH-pretreated group is expressed as percentage of the corresponding saline-pretreated group (mean ± S.E.M.).

P < 0.01, compared to respective control group, according to Student–Newman–Keuls multiple comparison test after a one-way ANOVA.

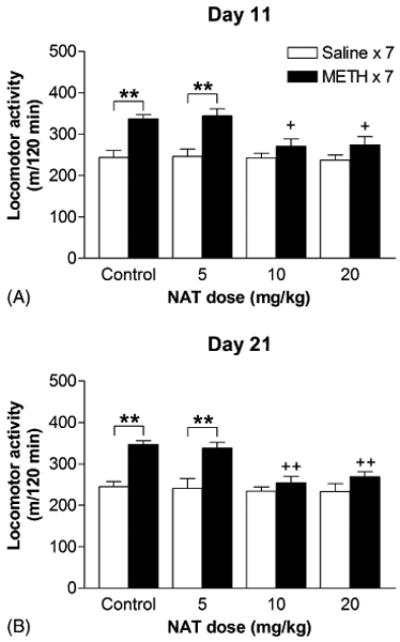

3.5. Effects of NAT on the expression of behavioral sensitization

To further investigate whether opioid receptors participate in the expression of METH-induced behavioral sensitization, non-sensitized (saline-pretreated) and sensitized (METH-pretreated) mice were injected i.p. with 0 (control), 5, 10 or 20 mg/kg of NAT 60 min prior to METH challenge on the day of behavioral testing. The effects of NAT on the expression of behavioral sensitization after short-term and long-term periods of abstinence were tested on days 11 and 21, respectively (Fig. 1C). Pretreatment with NAT had no effect on baseline activity in mice of any group (data not shown). Two-way ANOVA (METH × NAT) revealed significant effects for locomotor responses on days 11 (METH: F[1, 88] = 31.34, P < 0.001; NAT: F[3, 88] = 3.47, P = 0.02) and 21 (METH: F[1, 105] = 37.42, P < 0.001; NAT: F[3, 105] = 6.89, P < 0.001; interaction: F[3, 105] = 4.20, P = 0.008). Compared with the response of the corresponding control group, pretreatment with 10 or 20 mg/kg of NAT had no effect on the locomotor activity of saline-pretreated mice (saline × 7, open bars in figures) in response to METH challenge on days 11 and 21, but suppressed the response of METH-pretreated mice (METH × 7, closed bars in figures) to METH challenge on day 11 (Fig. 6A) and day 21 (Fig. 6B). The inhibitory effects of 10 and 20 mg/kg of NAT on day 21 appeared to be more potent than those on day 11. Compared with the response of the corresponding saline-pretreated group, METH-pretreated mice injected with 10 or 20 mg/kg of NAT prior to METH challenge did not express behavioral sensitization on days 11and 21. These findings indicate that 10 or 20 mg/kg of NAT blocked the expression of sensitization to locomotor stimulating effect of METH.

Fig. 6.

Dose effects of NAT on the expression of behavioral sensitization. Effects of NAT on the expression of behavioral sensitization after short-term and long-term periods of abstinence were tested on days 11 (A) and 21 (B), respectively, by determining the locomotor response to 1.25 mg/kg of METH challenge following the pretreatment of 0 (control), 5, 10, or 20 mg/kg of NAT. Data are expressed as total distance traveled (mean ± S.E.M.) for the entire 120 min period of testing (n = 10–16). +P < 0.05, ++P < 0.01, compared with the response of the corresponding control group; **P < 0.01, compared with the response of the corresponding saline-pretreated (saline × 7) group, according to Bonferroni post-tests after a two-way ANOVA.

4. Discussion

A previous study showed that the acute psychomotor effects of AMPH were enhanced when the treatment was administered in association with environmental novelty [4]. Recently, it was further demonstrated that the psychomotor activating effects of AMPH modulated by environmental context were independent of the primary neuropharmacological actions of the drug (e.g. changes in dopamine, glutamate, or asparate efflux) in the striatal complex [5]. In order to reveal neuropharmacological actions of the drug on behavior, physically identical home cages without bedding were used as the locomotor arena in this study. Although the variations in the characteristics of environment such as removal of bedding and varying locations (testing and colony rooms) made this test environment “semi-novel”, animals were allowed to acclimatize and habituate to this environment for several sessions before locomotor activity was measured in order to minimize the environmental influences on the locomotor stimulating effect of METH. In the experiments in which locomotor activities were measured during the first 30 min of the habituation period in the locomotor arena, locomotor activities in the mice were stabilized and returned to normal levels within this timeframe (data not shown). The present results of acute psychomotor activating effects of METH are consistent with previous findings that low doses of AMPH increased locomotor activity, while high doses of the drug induced intense stereotypic response [22]. Moreover, repeated pre-exposures to a test environment were also found to alter acute behavioral response to AMPH [6] and cocaine [19]. Therefore, in this study, the locomotor activity of each animal was monitored only once with the exception of those to determine the effects of repeated injection of METH.

Besides to reveal neuropharmacological actions of the drug on behavior, we attempted to eliminate the environmental influences in the present study in order to prevent a potential interpretation of complexity caused by environmental factors. However, behavioral sensitization has been suggested as representing a conditioning phenomenon that is largely dependent on learned interactions between drug effects and environmental cues [40,45]. In this study, the induction of behavioral sensitization was performed in home cages and the expression of behavioral sensitization was measured in the locomotor arena. By taking advantages of this “semi-novel” test environment, our results demonstrated that context-dependent locomotion did not develop under this experimental condition, even though the drug injection could be regarded as a “cue”. It might be argued that the specific environmental context associated with drug administration is an important experimental factor for the induction of behavioral sensitization. Indeed, according to our unpublished observation, mice receiving daily injections of METH in the test environment produced a higher magnitude of behavioral sensitization than those receiving drug treatment in home cages. However, our results demonstrated that repeated injection of METH dose-dependently induced behavioral sensitization in mice, and this effect lasted at least 3 weeks after the cessation of the drug treatment. These results are consistent with the findings that psychomotor stimulant-induced sensitization is not entirely dependent on drug–environment interactions [40]. The environmental context therefore does not appear to be critical for the induction of METH sensitization.

In the present study, a non-selective but long-acting antagonist NAT was used to block opioid receptors. NAT was injected 60 min prior to METH administration for the purpose of preventing the possible pharmacokinetic interactions between drugs. A previous study in mice reported that the concentrations of NAT in plasma and brain tissue 60 min after i.p. injection (1 mg/kg) were 4 ± 1 ng/ml and 9 ± 1 ng/g, respectively [53]. In order to ensure the complete blockade of all opioid receptors while METH was administered, higher doses (i.e. 5–20 mg/kg) of NAT were used. The results indicate that there was a lack of NAT effect on the locomotor response to METH challenge in saline-pretreated mice (open bars, Fig. 6). Therefore, it seems unlikely that the metabolism of METH was affected by pretreatment with NAT. As altered distribution and excretion of METH were found in METH-sensitized animals [18,34], we cannot completely rule out the potential pharmacokinetic interactions between NAT and METH in this study. Further research is needed to clarify this point.

It may be questioned that repeated treatment of NAT might cause alterations in neurotransmitter systems and that these alterations per se would affect the outcome of sensitization. Indeed, we found that pretreatment with NAT during the induction period produced a “cross-sensitization” effect on the locomotor stimulating effect of METH in saline-pretreated mice (open bars, Fig. 5A). However, the effect of NAT on the induction of sensitization should be revealed by making comparisons between saline- and METH-pretreated groups that received the same dose of NAT. Our results indicate the involvement of opioid receptors in the induction of METH-induced behavioral sensitization. This observation is the first time to our knowledge, that a blockade of opioid receptors during the induction period affects the development of METH-induced behavioral sensitization. Moreover, since the inhibitory effect of NAT tended to recover after a longer period of abstinence, some neuroadaptations after repeated METH treatment might occur and contribute to the expression of behavioral sensitization.

Pretreatments with 10 or 20 mg/kg of NAT prior to METH challenge blocked the expression of behavioral sensitization on days 11 and 21, 4 and 14 days after repeated injection of METH, respectively. A previous study in rats, which was similar to this experiment, found that naloxone (5 mg/kg) did not modify the expression of behavioral sensitization after 2 days of abstinence, but it completely blocked the expression when tested after 14 days of abstinence [27]. Although the inhibitory effects of 10 and 20 mg/kg of NAT on day 21 appeared to be more potent than those on day 11, the discrepancies may have resulted from differences in subjects, drugs, or experimental conditions used in the two studies. Our results indicate the involvement of opioid receptors in the expression of METH-induced behavioral sensitization and suggest potential alterations in opioid receptors, which might be time-dependent and critical for expression of METH-induced behavioral sensitization during different periods of abstinence.

Chronic treatment with opioid receptor antagonist is known to increase the density of opioid receptors in animal models. An autoradiographic study in mice further revealed that up-regulation of μ-opioid receptors by chronic NAT was more evident (74 and 57%) than δ-opioid receptors (16 and 48%). The expression of κ-opioid receptors was nearly unchanged (9 and 1% in the VTA and NAcc, respectively) [24]. This up-regulation of opioid receptors has been shown to accompany supersensitivity to opioid agonists and is an indication of their functional relevance [48]. Moreover, repeated treatment with AMPH or METH was found to increase not only the mRNA levels of μ-opioid receptors in the VTA and NAcc [27] but also the dopamine releasing effects of μ-opioid receptor agonist [55]. This suggested that the alterations in μ-opioid receptors are functionally involved. Activation of μ-opioid receptors was found to potentiate behaviors induced by either direct [14] or indirect dopamine agonists [17]. Repeated administration of morphine or repeated activation of μ-opioid receptors was found to initiate behavioral sensitization to AMPH [8,50]. A significant increase in μ-opioid receptor autoradiography in some brain regions was also found in morphine-sensitized animals [52]. The findings described above raise the possibility that μ-opioid receptors are susceptible to repeated AMPH or METH treatment, and provide a possible hypothesis to explain our observation that the up-regulation of μ-opioid receptors by chronic NAT treatment potentiates the expression of behavioral sensitization. However, whether alteration in μ-opioid receptors is involved in behavioral sensitization induced by METH has not been addressed in the present study. Further research on the effects of other specific opioid receptor antagonists and alterations in opioid receptors should offer the answer to this question.

By using a gene deletion or replacement strategy, specific opioid receptor gene knockout mice have been developed [26]. These genetically manipulated mice provide a powerful means of revealing the function of opioid receptors in vivo. However, functionally compensatory alterations in other neurotransmitter systems found in gene knockout mice [14,36,37] may sometimes complicate the outcome or even mislead the interpretation. Therefore, it is more important and necessary to determine the effects of pharmacological manipulation on genetically normal subjects in terms of potential clinical relevance.

A previous study in rats using a reinstatement model showed that NAT attenuated cue- but not drug-induced METH seeking [3]. According to our findings, pretreatment with NAT appeared to attenuate the “context-independent” part of sensitization. These results seemed to be contradictory to each other. It should be mentioned that they were based on completely different experimental approaches and conditions. Moreover, naloxone was found to reduce the neurochemical and behavioral effects of AMPH but not those of cocaine [41]. Several studies on the role of opioid receptors in cocaine-induced behavioral sensitization using genetic or pharmacological manipulations [11,25,56] revealed different results to ours in METH-induced behavioral sensitization. Although cocaine and METH are psychomotor stimulates that increase extracellular levels of monoamines, they differ in their mechanisms of action. Cocaine acts as a competitive inhibitor of the monoamine transporters while METH reverses them [42,47]. Furthermore, the consequences produced by cocaine and METH, such as the expressions of opioid peptide mRNA [1,2] and immediate early genes [33,46] in some brain regions, are distinct. Therefore, the role of opioid receptors in the induction or expression of behavioral sensitization of these drugs may not be the same.

In summary, our results confirm and extend those of previous studies by demonstrating that the induction of behavioral sensitization is independent of environmental context associated with drug administration. Context switch did not produce context-dependent locomotion and abolish sensitization. Under our experimental conditions, repeated injection of METH dose-dependently induced behavioral sensitization. In addition, the results indicate that opioid receptors participate in the induction and expression of behavioral sensitization to METH. Administrations of NAT during the induction period had differential effects on the expression of sensitization after different periods of abstinence suggesting that neuroadaptations, after repeated METH treatment, contribute to the expression of behavioral sensitization. Moreover, our results show that differential effects on the expressions of sensitization occurred when the animals were injected with NAT prior to METH challenge at different time points during abstinence. These findings suggest that potential alterations in opioid receptors after repeated METH treatment are time-dependent and critical for expression of METH-induced behavioral sensitization.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. John C. Kermode for statistical advice and Ms. Ann Pace for helpful editorial assistance on this manuscript. This study was supported by research funds received from the Center of Psychiatric Neuroscience at the University of Mississippi Medical Center which is supported by NIH Grant Number RR-P20 RRl7701 and The Human Science Grant Foundation of Japan.

Abbreviations

- AMPH

amphetamine

- METH

methamphetamine

- NAT

naltrexone

- NAcc

nucleus accumbens

- VTA

ventral tegmental area

References

- 1.Adams DH, Hanson GR, Keefe KA. Cocaine and metham-phetamine differentially affect opioid peptide mRNA expression in the striatum. J Neurochem. 2000;75:2061–2070. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0752061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams DH, Hanson GR, Keefe KA. Distinct effects of metham-phetamine and cocaine on preprodynorphin messenger RNA in rat striatal patch and matrix. J Neurochem. 2003;84:87–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anggadiredja K, Sakimura K, Hiranita T, Yamamoto T. Naltrexone attenuates cue- but not drug-induced methamphetamine seeking: a possible mechanism for the dissociation of primary and secondary reward. Brain Res. 2004;1021:272–276. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Badiani A, Anagnostaras SG, Robinson TE. The development of sensitization to the psychomotor stimulant effects of amphetamine is enhanced in a novel environment. Psychopharmacology (Berlin) 1995;117:443–452. doi: 10.1007/BF02246217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Badiani A, Oates MM, Fraioli S, Browman KE, Ostrander MM, Xue CJ, Wolf ME, Robinson TE. Environmental modulation of the response to amphetamine: dissociation between changes in behavior and changes in dopamine and glutamate overflow in the rat striatal complex. Psychopharmacology (Berlin) 2000;151:166–174. doi: 10.1007/s002139900359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bardo MT, Bowling SL, Pierce RC. Changes in locomotion and dopamine neurotransmission following amphetamine, haloperidol, and exposure to novel environmental stimuli. Psychopharmacology (Berlin) 1990;101:338–343. doi: 10.1007/BF02244051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castner SA, Goldman-Rakic PS. Long-lasting psychotomimetic consequences of repeated low-dose amphetamine exposure in rhesus monkeys. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;20:10–28. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00050-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen JC, Liang KW, Huang EY. Differential effects of endomorphin-1 and -2 on amphetamine sensitization: neurochemical and behavioral aspects. Synapse. 2001;39:239–248. doi: 10.1002/1098-2396(20010301)39:3<239::AID-SYN1005>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clarke PB, Jakubovic A, Fibiger HC. Anatomical analysis of the involvement of mesolimbocortical dopamine in the locomotor stimulant actions of d-amphetamine and apomorphine. Psychopharmacology (Berlin) 1988;96:511–520. doi: 10.1007/BF02180033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ginawi OT, al-Shabanah OA, Bakheet SA. Increased toxicity of methamphetamine in morphine-dependent mice. Gen Pharmacol. 1997;28:727–731. doi: 10.1016/s0306-3623(96)00308-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hall FS, Goeb M, Li XF, Sora I, Uhl GR. Micro-opioid receptor knockout mice display reduced cocaine conditioned place preference but enhanced sensitization of cocaine-induced locomotion. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2004;121:123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2003.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hooks MS, Jones DN, Justice JB, Jr, Holtzman SG. Naloxone reduces amphetamine-induced stimulation of locomotor activity and in vivo dopamine release in the striatum and nucleus accumbens. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1992;42:765–770. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(92)90027-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Itzhak Y, Ali SF. Behavioral consequences of methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity in mice: relevance to the psychopathology of methamphetamine addiction. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;965:127–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jang C, Park Y, Tanaka S, Ma T, Loh HH, Ho IK. Involvement of mu-opioid receptors in potentiation of apomorphine-induced climbing behavior by morphine: studies using mu-opioid receptor gene knockout mice. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2000;78:204–206. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(00)00094-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalivas PW, Stewart J. Dopamine transmission in the initiation and expression of drug- and stress-induced sensitization of motor activity. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1991;16:223–244. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(91)90007-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karler R, Calder LD, Thai LH, Bedingfield JB. The dopaminergic, glutamatergic, GABAergic bases for the action of amphetamine and cocaine. Brain Res. 1995;671:100–104. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)01334-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kimmel HL, Holtzman SG. Mu-opioid agonists potentiate amphetamine- and cocaine-induced rotational behavior in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;282:734–746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kitaichi K, Morishita Y, Doi Y, Ueyama J, Matsushima M, Zhao YL, Takagi K, Hasegawa T. Increased plasma concentration and brain penetration of methamphetamine in behaviorally sensitized rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;464:39–48. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01321-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kiyatkin EA. State-dependent peculiarities of cocaine-induced behavioral sensitization and their possible reasons. Int J Neurosci. 1992;67:93–103. doi: 10.3109/00207459208994776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klitenick MA, De Witte P, Kalivas PW. Regulation of somatodendritic dopamine release in the ventral tegmental area by opioids and GABA: an in vivo microdialysis study. J Neurosci. 1992;12:2623–2632. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-07-02623.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kubota Y, Inagaki S, Kito S, Takagi H, Smith AD. Ultrastructural evidence of dopaminergic input to enkephalinergic neurons in rat neostriatum. Brain Res. 1986;367:374–378. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)91622-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuczenski R, Segal DS. Sensitization of amphetamine-induced stereotyped behaviors during the acute response. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;288:699–709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuribara H. Effects of interdose interval on ambulatory sensitization to methamphetamine, cocaine and morphine in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;316:1–5. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(96)00635-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lesscher HM, Bailey A, Burbach JP, Van Ree JM, Kitchen I, Gerrits MA. Receptor-selective changes in mu-, delta- and kappa-opioid receptors after chronic naltrexone treatment in mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:1006–1012. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lesscher HM, Hordijk M, Bondar NP, Alekseyenko OV, Burbach JP, Van Ree JM, Gerrits MA. Mu-opioid receptors are not involved in acute cocaine-induced locomotor activity nor in development of cocaine-induced behavioral sensitization in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:278–285. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loh HH, Liu HC, Cavalli A, Yang W, Chen YF, Wei LN. Mu-opioid receptor knockout in mice: effects on ligand-induced analgesia and morphine lethality. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1998;54:321–326. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(97)00353-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Magendzo K, Bustos G. Expression of amphetamine-induced behavioral sensitization after short- and long-term withdrawal periods: participation of mu- and delta-opioid receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:468–477. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Magnan J, Paterson SJ, Tavani A, Kosterlitz HW. The binding spectrum of narcotic analgesic drugs with different agonist and antagonist properties. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1982;319:197–205. doi: 10.1007/BF00495865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mansour A, Khachaturian H, Lewis ME, Akil H, Watson SJ. Anatomy of CNS opioid receptors. Trends Neurosci. 1988;11:308–314. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(88)90093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Masukawa Y, Suzuki T, Misawa M. Differential modification of the rewarding effects of methamphetamine and cocaine by opioids and antihistamines. Psychopharmacology (Berlin) 1993;111:139–143. doi: 10.1007/BF02245515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matthews RT, German DC. Electrophysiological evidence for excitation of rat ventral tegmental area dopamine neurons by morphine. Neuroscience. 1984;11:617–625. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(84)90048-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meredith GE, Pennartz CM, Groenewegen HJ. The cellular framework for chemical signalling in the nucleus accumbens. Prog Brain Res. 1993;99:3–24. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)61335-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moratalla R, Robertson HA, Graybiel AM. Dynamic regulation of NGFI-A (zif268, egr1) gene expression in the striatum. J Neurosci. 1992;12:2609–2622. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-07-02609.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakagawa N, Hishinuma T, Nakamura H, Yamazaki T, Tsukamoto H, Hiratsuka M, Ido T, Mizugaki M, Terasaki T, Goto J. Brain and heart specific alteration of methamphetamine (MAP) distribution in MAP-sensitized rat. Biol Pharm Bull. 2003;26:506–509. doi: 10.1248/bpb.26.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olive MF, Koenig HN, Nannini MA, Hodge CW. Stimulation of endorphin neurotransmission in the nucleus accumbens by ethanol, cocaine, and amphetamine. J Neurosci. 2001;21:RC184. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-23-j0002.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park Y, Ho IK, Fan LW, Loh HH, Ko KH. Region specific increase of dopamine receptor D1/D2 mRNA expression in the brain of mu-opioid receptor knockout mice. Brain Res. 2001;894:311–315. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02001-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park Y, Jang CG, Yang KH, Loh HH, Ma T, Ho IK. Regional specific increases of [3H]AMPA binding and mRNA expression of AMPA receptors in the brain of mu-opioid receptor knockout mice. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2003;113:116–123. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(03)00123-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paulson PE, Camp DM, Robinson TE. Time course of transient behavioral depression and persistent behavioral sensitization in relation to regional brain monoamine concentrations during amphetamine withdrawal in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berlin) 1991;103:480–492. doi: 10.1007/BF02244248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robinson TE, Becker JB. Enduring changes in brain and behavior produced by chronic amphetamine administration: a review and evaluation of animal models of amphetamine psychosis. Brain Res. 1986;396:157–198. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(86)80193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Robinson TE, Browman KE, Crombag HS, Badiani A. Modulation of the induction or expression of psychostimulant sensitization by the circumstances surrounding drug administration. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1998;22:347–354. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(97)00020-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schad CA, Justice JB, Jr, Holtzman SG. Naloxone reduces the neurochemical and behavioral effects of amphetamine but not those of cocaine. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;275:9–16. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)00726-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seiden LS, Sabol KE, Ricaurte GA. Amphetamine: effects on catecholamine systems and behavior. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1993;33:639–677. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.33.040193.003231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sesack SR, Pickel VM. Dual ultrastructural localization of enkephalin and tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactivity in the rat ventral tegmental area: multiple substrates for opiate–dopamine interactions. J Neurosci. 1992;12:1335–1350. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-04-01335.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stephans SE, Yamamoto BK. Methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity: roles for glutamate and dopamine efflux. Synapse. 1994;17:203–209. doi: 10.1002/syn.890170310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stewart J, Badiani A. Tolerance and sensitization to the behavioral effects of drugs. Behav Pharmacol. 1993;4:289–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tan A, Moratalla R, Lyford GL, Worley P, Graybiel AM. The activity-regulated cytoskeletal-associated protein arc is expressed in different striosome-matrix patterns following exposure to amphetamine and cocaine. J Neurochem. 2000;74:2074–2078. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0742074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Taylor D, Ho BT. Comparison of inhibition of monoamine uptake by cocaine, methylphenidate and amphetamine. Res Commun Chem Pathol Pharmacol. 1978;21:67–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tempel A, Zukin RS, Gardner EL. Supersensitivity of brain opiate receptor subtypes after chronic naltrexone treatment. Life Sci. 1982;31:1401–1404. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(82)90391-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Trujillo KA, Belluzzi JD, Stein L. Naloxone blockade of amphetamine place preference conditioning. Psychopharmacology (Berlin) 1991;104:265–274. doi: 10.1007/BF02244190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vanderschuren LJ, De Vries TJ, Wardeh G, Hogenboom FA, Schoffelmeer AN. A single exposure to morphine induces long-lasting behavioural and neurochemical sensitization in rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;14:1533–1538. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vezina P. D1 dopamine receptor activation is necessary for the induction of sensitization by amphetamine in the ventral tegmental area. J Neurosci. 1996;16:2411–2420. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-07-02411.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vigano D, Rubino T, Di Chiara G, Ascari I, Massi P, Parolaro D. Mu-opioid receptor signaling in morphine sensitization. Neuroscience. 2003;117:921–929. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00825-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang D, Raehal KM, Lin ET, Lowery JJ, Kieffer BL, Bilsky EJ, Sadee W. Basal signaling activity of mu-opioid receptor in mouse brain: role in narcotic dependence. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;308:512–520. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.054049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.White FJ, Wang RY. Electrophysiological evidence for A10 dopamine autoreceptor subsensitivity following chronic d-amphetamine treatment. Brain Res. 1984;309:283–292. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90594-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yokoo H, Yamada S, Yoshida M, Tanaka T, Mizoguchi K, Emoto H, Koga C, Ishii H, Ishikawa M, Kurasaki N, Matsui M, Tanaka M. Effect of opioid peptides on dopamine release from nucleus accumbens after repeated treatment with methamphetamine. Eur J Pharmacol. 1994;256:335–338. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90560-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yoo JH, Yang EM, Lee SY, Loh HH, Ho IK, Jang CG. Differential effects of morphine and cocaine on locomotor activity and sensitization in mu-opioid receptor knockout mice. Neurosci Lett. 2003;344:37–40. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00410-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang XF, Hu XT, White FJ, Wolf ME. Increased responsiveness of ventral tegmental area dopamine neurons to glutamate after repeated administration of cocaine or amphetamine is transient and selectively involves AMPA receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;281:699–706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang Y, Loonam TM, Noailles PA, Angulo JA. Comparison of cocaine- and methamphetamine-evoked dopamine and glutamate overflow in somatodendritic and terminal field regions of the rat brain during acute, chronic, and early withdrawal conditions. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;937:93–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]