Abstract

Objective

Couples facing metastatic breast cancer (MBC) must learn to cope with stressors that can affect both partners' quality of life as well as the quality of their relationship. Common dyadic coping involves taking a “we” approach, whereby partners work together to maintain their relationship while jointly managing their shared stress. This study prospectively evaluated whether common dyadic coping was associated with less cancer-related distress and greater dyadic adjustment for female MBC patients and their male partners.

Design

Couples (N = 191) completed surveys at the start of treatment for MBC (baseline), and 3 and 6 months later.

Main Outcome Measures

Cancer-related distress was assessed with the Impact of Events Scale; dyadic adjustment was assessed using the short-form of the Dyadic Adjustment Scale.

Results

Multilevel models using the couple as the unit of analysis showed that the effects of common positive dyadic coping on cancer-related distress significantly differed for patients and their partners. Whereas partners experienced slightly lower levels of distress, patients experienced slightly higher levels of distress. Although patients and partners who used more common negative dyadic coping experienced significantly greater distress at all times, the association was stronger for patients. Finally, using more common positive dyadic coping and less common negative dyadic coping was mutually beneficial for patients and partners in terms of greater dyadic adjustment.

Conclusion

Our findings underscore the importance of couples working together to manage the stress associated with MBC. Future research may benefit from greater focus on the interactions between patients and their partners to address ways that couples can adaptively cope together.

Keywords: metastases, breast cancer, couples, dyadic coping, distress, dyadic adjustment

Unlike early stage breast cancer, metastatic breast cancer (MBC) cannot be cured. Women diagnosed with MBC experience increased physical (i.e., pain, fatigue, shortness of breath, weight loss) and emotional symptoms (Butler, Koopman, Classen, & Spiegel, 1999; Butler et al., 2003; Massie & Holland, 1990; Spiegel, 1996); their average life expectancy is 2 years (Harris, Lippman, Veronesi, & Willett, 1992). Research shows that the quality of the spousal relationship is important in terms of patient adjustment to MBC (Giese-Davis, Hermanson, Koopman, Weibel, & Spiegel, 2000). Indeed, many patients turn to their partners for increased support during this stressful time (Bloom, 1982; Primomo, Yates, & Woods, 1990). However, partners are also under extreme stress and this may impair their ability to provide adequate support to the patient. Likewise, couples coping with MBC experience shared stressors such as the need to discuss end-of-life issues and care. These shared or dyadic stressors can affect both partners' well-being as well as the quality of their relationship and thus require dyadic or collaborative coping (Berg & Upchurch, 2007; Bodenmann, 1997, 2005).

Broadly viewed, dyadic coping recognizes mutuality and interdependence in coping responses to a specific shared stressor, indicating that couples respond to stressors as interpersonal units rather than as individuals in isolation. The construct of dyadic coping goes beyond the exchange of social support, although that is a central component in most definitions (Berg & Upchurch, 2007). In dyadic coping, the members of the couple negotiate the emotional aspects of their shared experience (Coyne & Smith, 1991) or engage in collaborative coping, such as joint problem-solving (Berg et al., 2008). Mutual or common dyadic coping involves taking a “we” approach whereby both persons work together to maintain the quality of their relationship while they jointly manage their shared stress.

Why Study Couples' Psychosocial Adjustment to MBC?

The lion's share of research on couples' adaptation to cancer has studied women with early stage breast cancer and often only from the patient's perspective. Thus, we have much to learn about women in later stages of the illness and how couples manage cancer-related stressors to optimal effect. Although women with early stage breast cancer and their partners often initially experience great fear and apprehension about the future, most experience diminished distress the farther they are from the time of diagnosis or as the patient's prognosis improves (Hagedoorn, Sanderman, Bolks, Tuinstra, & Coyne, 2008). In contrast, couples facing metastatic disease must learn to cope with the psychological, practical, and relationship consequences of living with a terminal illness and the expectation of a future characterized by additional treatments, progressive physical disability, and death (Butler et al., 2003; Cella & Tross, 1986). It is not surprising that cross-sectional and longitudinal studies show that about one-third of women with MBC and their partners experience clinically significant levels of depression, anxiety, and/or traumatic stress symptoms (Baider, Perez, & DeNour, 1989; Butler, Koopman, Classen, & Spiegel, 1999; Carter & Carter, 1994; Cella, Mahon, & Donovan, 1990). Although distress often increases for patients and their partners as the patient approaches death (Brown et al., 2000; Glasdam, Jensen, Madsen, & Rose, 1996), partners are far less likely to ask for or receive professional help for their distress than are patients (Vanderwerker, Laff, Kadan-Lottick, McColl, & Prigerson, 2005).

Relationship satisfaction and social support are two resources that may enhance well-being in couples facing MBC. Higher levels of marital satisfaction have been shown to buffer the effects of cancer patients' physical impairment on their partners' distress (Fang, Manne, & Pape, 2001) and the effects of one partner's distress on that of the other (Carmack Taylor et al., 2008). Although patients report better emotional adjustment after a cancer diagnosis if their partners are highly supportive (Kayser & Sormanti, 2002; Manne et al., 2004; Northouse, Templin, & Mood, 2001), partners sometimes report that their needs are overlooked (Oberst & James, 1985). Few studies have examined the provision of support from breast cancer patients to their partners. One study found that husbands were dissatisfied with the emotional support they received from their ill wives and experienced more negative emotions (e.g., worry, tension) than those who were satisfied with the support their wives provided (Hoskins et al., 1996). Thus, research on the role of social support in patient and partner adjustment to cancer suggests a reciprocal support process, although few studies have obtained data from both members of the couple.

Dyadic Stress and Coping Models

An illness such as breast cancer affects both partners in a relationship and is thus considered a dyadic stressor. Such stressors are common in everyday life but are challenging to study because they can affect people on both an individual and a couple level. At the individual level, each person's experience of the stressor is filtered by his or her own unique needs and concerns. Thus, MBC patients may be more concerned about the emotional, physical, and practical consequences of having a terminal illness while their partners may be preoccupied with caregiving or worry about the loss of their life partner. At the couple level, patients and partners may coordinate how they cope with these illness-related stressors. This may include practical efforts such as managing household responsibilities, as well as more emotionally laden coping tasks such as coming to agreement on end-of-life issues and care.

Although dyadic stressors affect both partners individually and collectively as a couple, most research on couples' coping with cancer has adopted a patient-centered focus, guided by Lazarus and Folkman's (1984) transactional model of stress. This model views social support as a form of coping assistance (Thoits, 1986) and conceptualizes one person (usually the healthy partner) as the support provider and the other (usually the patient) as the support recipient. Research emanating from this model has shown that even though the spousal relationship can be a tremendous coping resource, partners can sometimes be negative or unsupportive. Unsupportive partner behaviors such as hiding worries, criticizing the patient's coping efforts, avoiding cancer-related discussions, and providing unsolicited advice are of concern because they can reduce the patient's ability to cope effectively and exacerbate psychological and marital distress (Badr & Carmack Taylor, 2009; Manne, Dougherty, Veach, & Kless, 1999; Manne et al., 2003; Manne et al., 2007; Manne, Taylor, Dougherty, & Kerneny, 1997). Given this, developing a better understanding of the ways that patients and partners support each other and cope together may aid in the development of couple-focused interventions.

The Systemic-Transactional Model (STM) posits a model of dyadic coping in which, faced with a shared stressor, partners cope both individually and collectively as a unit (Bodenmann, 1997, 2005). At the individual level, stress appraisals are shaped by individual needs and concerns. Based on these appraisals, a stress communication process is triggered whereby each partner communicates his or her own stress to the other in hopes of receiving support and coping feedback. The other partner can respond in either a supportive or unsupportive fashion. Supportive responses include providing advice and practical help with daily tasks, showing empathy and concern, expressing solidarity, and helping one's partner to relax and engage in positive reframing. Unsupportive responses include showing disinterest, providing support that is accompanied by criticism, distancing, or sarcasm, and minimizing the severity of the stressor. This coping is considered “dyadic” because both partners are involved; however, each person's involvement is confined to helping the other manage his or her own stress. Coping responses at this level are termed supportive and unsupportive (dyadic) coping. At the couple-level, relational well-being is affected by the couple's ability to work as a team to manage aspects of the dyadic stressor that affect both of them. This coordinated effort also has both positive and negative forms. Common positive dyadic coping involves joint problem solving, coordinating everyday demands, relaxing together, as well as mutual calming, sharing, and expressions of solidarity. Common negative dyadic coping involves mutual avoidance and withdrawal.

In summary, the STM involves multiple interactive components: (a) the degree to which both partners communicate their own stress to each other (i.e., stress communication); (b) the degree to which both partners respond to each other's stress (i.e., supportive or unsupportive coping); and (c) the degree to which both partners work together to manage dyadic stress and restore a sense of balance in their relationship (i.e., common positive or negative dyadic coping). Compared with other approaches for understanding how couples cope with stress and illness (e.g., relationship-focused coping; Coyne & Smith, 1991), the STM provides a potentially more complete portrait of how support transactions unfold in close relationships and how couples can cope as a team. Until now, no studies have systematically evaluated this model in cancer populations; however, a meta-analysis of 13 studies of healthy adult couples and couples in which one partner had a psychiatric diagnosis provided convincing evidence for the association between dyadic coping and marital functioning (d = 1.3; Bodenmann, 2005). A study of community-dwelling adults also found that couples who reported low levels of common positive dyadic coping at study entry were more likely to divorce or separate 5 years later (Bodenmann & Cina, 2000).

The Current Study

Couples coping with advanced cancers report more emotional distress, role restrictions, and physical problems than those coping with early stage disease (Lewis & Deal, 1995; Weitzner, McMillan, & Jacobsen, 1999). Some studies have identified individual-level factors associated with patient and partner adjustment to MBC (Fleming et al., 2006; Northouse, Dorms, & Charron-Moore, 1995; Northouse et al., 2002). However, few have examined how dyadic processes affect the adjustment of this vulnerable and underresearched population, and none have tested the STM with cancer patients.

Several empirical questions remain regarding the utility of the STM construct with MBC populations. First, it is unclear whether dyadic coping alleviates individual psychological distress. Given that dyadic coping unfolds because one or both partners is in need of coping assistance, it is important to evaluate whether its potential benefits extend beyond improving relationship functioning to helping individuals cope with their cancer-related distress. Second, the benefits of mutual emotional disclosure in this population are unknown. Descriptive studies have already demonstrated that disclosing concerns to a supportive partner is related to better adaptation to early stage cancer (Figueiredo, Fries, & Ingram, 2004; Manne et al., 2004; Porter, Keefe, Hurwitz, & Faber, 2005). Interventions that teach couples to engage in supportive communication have also been shown to reduce distress (Scott, Halford, & Ward, 2004). The communication processes these studies describe are similar to those described by the STM. However, they did not specifically test the STM nor did they evaluate the mutual, dyadic aspect of coping—whether patients and partners who work together to manage a shared stressor while maintaining their relationship reap added benefit beyond the benefits of receiving social support.

To address these questions, we conducted a prospective study of couples where the patient was initiating treatment for MBC. We hypothesized that engaging in common positive dyadic coping would be associated with less cancer-related distress and greater dyadic adjustment after controlling for the effects of each person's stress communication and their perceptions of their partner's supportive and unsupportive coping efforts. Thus, our goal was to examine the effects of common dyadic coping beyond the effects of support exchange. Because previous dyadic coping studies have demonstrated positive effects for both members of the couple (Bodenmann, 2005), we also hypothesized that common positive dyadic coping would be associated with lower cancer-related distress and greater dyadic adjustment for both MBC patients and their partners. Indeed, cancer patients and their partners have different perspectives on the illness experience, so it is important to evaluate whether engaging in common dyadic coping is mutually beneficial for both members of the couple.

Method

Procedure

Data were drawn from a larger study of spousal relationships and MBC pain. Female MBC patients were identified through medical chart review and approached to participate during routine clinic visits. Patients were eligible if they: (a) were initiating treatment for MBC; (b) had a physician-rated Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status score ≤2 (i.e., ambulatory and capable of all self-care but unable to perform any work activities); (c) rated their average pain as ≥1 on the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI; Cleeland & Syrjala, 1992; where 0 = no pain and 10 = worst pain imaginable); (d) could speak and understand English; and (e) had a male partner (spouse or significant other) with whom they had lived for at least 1 year. Patients and partners completed written surveys and returned them in individually sealed postage-paid envelopes. Follow-up surveys were mailed 3 and 6 months later, and participants received gift cards worth $10 upon the return of each completed survey.

Measures

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics and internal consistency reliability coefficients (Cronbach's α) for patients and partners on all the measures at each assessment.

Table 1.

Correlations, Scale Reliabilities, and Descriptive Results for Patients and Partners at Each Assessment

| CRSCa | PPSC | PPUC | CPDC | CNDC | IES | DAS7 | Patients† |

Partners† |

t‡ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha | Mean ± SD | Range | Alpha | Mean ± SD | Range | |||||||||

| CRSCa | ||||||||||||||

| Baseline | .001 | .15* | −.12 | .22* | −.09 | −.06 | .19* | .71 | 4.18 ± .92 | 1.75–6.00 | .70 | 3.26 ± .88 | 1.50–6.00 | 9.41*** |

| 3 months | − .04 | .17 | −.18 | .17 | −.07 | −.01 | .11 | .79 | 4.11 ± .95 | 2.00–6.00 | .67 | 3.28 ± .82 | 1.25–5.75 | 7.34*** |

| 6 months | − .04 | .14 | −.25* | .19 | −.26* | −.19 | .21* | .79 | 4.08 ± 1.01 | 2.00–6.00 | .76 | 3.23 ± .92 | 1.00–6.00 | 5.82*** |

| PPSCb | ||||||||||||||

| Baseline | .08 | .34 ** | −.28* | .41** | −.25** | −.04 | .29** | .90 | 4.47 ± 1.05 | 1.67–6.00 | .92 | 3.80 ± 1.06 | 1.33–6.00 | 7.23*** |

| 3 months | −.003 | .30 ** | −.16 | .33** | −.27** | −.05 | .34** | .91 | 4.34 ± 1.09 | 1.67–6.00 | .90 | 3.79 ± .94 | 1.33–6.00 | 5.40*** |

| 6 months | −.02 | .28 ** | −.38** | .36** | −.47** | −.25* | .31** | .91 | 4.32 ± 1.11 | 1.83–6.00 | .89 | 3.63 ± .96 | 1.33–6.00 | 5.68*** |

| PPUCc | ||||||||||||||

| Baseline | −.07 | −.28** | .30 ** | −.28** | .32** | .02 | −.25** | .82 | 1.68 ± .78 | 1.00–4.50 | .86 | 1.80 ± .80 | 1.00–5.50 | — |

| 3 months | −.07 | −.36** | .30 ** | −.35** | .30** | .21* | −.38** | .78 | 1.60 ± .72 | 1.00–4.00 | .82 | 1.84 ± .79 | 1.00–4.33 | −2.95*** |

| 6 months | −.08 | −.28** | .43 ** | −.34** | .52** | .39** | −.32** | .82 | 1.72 ± .81 | 1.00–4.33 | .83 | 1.96 ± .86 | 1.00–5.33 | −2.52** |

| CPDCd | ||||||||||||||

| Baseline | .20** | .43** | −.29** | .49 ** | −.27** | −.06 | .39** | .90 | 3.97 ± 1.10 | 1.17–6.00 | .90 | 3.78 ± 1.03 | 1.00–6.00 | 2.24* |

| 3 months | .15 | .54** | −.32** | .51 ** | −.40** | −.13 | .45** | .89 | 3.96 ± 1.06 | 1.50–6.00 | .91 | 3.77 ± .98 | 1.33–6.00 | 2.64** |

| 6 months | .06 | .47** | −.48** | .52 ** | −.53** | −.31** | .43** | .88 | 3.81 ± 1.04 | 1.17–6.00 | .90 | 3.61 ± 1.01 | 1.00–6.00 | 2.29* |

| CNDCe | ||||||||||||||

| Baseline | −.11 | −.31** | .31** | −.38** | .27 ** | −.05 | −.33** | — | 2.13 ± 1.20 | 1.00–6.00 | — | 2.21 ± 1.12 | 1.00–6.00 | — |

| 3 months | −.10 | −.35** | .31** | −.33** | .26 ** | .15 | −.37** | — | 1.97 ± 1.00 | 1.00–5.00 | — | 2.19 ± 1.10 | 1.00–6.00 | — |

| 6 months | −.03 | −.44** | .43** | −.45** | .56 ** | .35** | −.41** | — | 2.03 ± 1.11 | 1.00–5.00 | — | 2.18 ± 1.10 | 1.00–6.00 | — |

| IESf | ||||||||||||||

| Baseline | .04 | −.08 | .19* | −.20** | .17* | .19 ** | −.18* | .89 | 20.73 ± 14.36 | 0–55.00 | .89 | 19.38 ± 13.71 | 0–66.00 | — |

| 3 months | .001 | −.32** | .15 | −.28** | .24* | .32 ** | −.27** | .87 | 20.02 ± 13.12 | 0–58.00 | .90 | 16.95 ± 12.87 | 0–54.00 | — |

| 6 months | −.10 | −.19 | .27* | −.33** | .47** | .38 ** | −.27** | .90 | 19.23 ± 14.36 | 0–56.00 | .91 | 18.71 ± 14.15 | 0–57.00 | — |

| DAS7g | ||||||||||||||

| Baseline | .12 | .38** | −.39** | .44** | −.37** | −.18* | .55 ** | .87 | 25.66 ± 6.21 | 9.00–36.00 | .89 | 24.80 ± 5.60 | 3.00–35.00 | 2.14* |

| 3 months | .17 | .40** | −.30** | .52** | −.35** | −.24* | .57 ** | .84 | 24.92 ± 6.21 | 9.00–36.00 | .90 | 24.88 ± 6.13 | 1.00–36.00 | — |

| 6 months | .07 | .42** | −.43** | .50** | −.51** | −.43** | .54 ** | .86 | 25.00 ± 6.13 | 7.00–36.00 | .91 | 24.45 ± 6.49 | 2.00–36.00 | — |

Note. Patient correlations on lower diagonal, partner correlations on upper diagonal, and partial correlations are on the diagonal

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Mean scores did not significantly differ for patients or partners over time.

Paired t-tests examined differences in patient and partner scores at each assessment.

Own Cancer-Related Stress Communication.

Perceived Partner Supportive Coping.

Perceived Partner Unsupportive Coping.

Common Positive Dyadic Coping.

Common Negative Dyadic Coping.

Impact of Events Scale Total Score.

Short Form 7-item Dyadic Adjustment Scale Total Score.

Dyadic coping

Originally developed in German and later translated to English, the Dyadic Coping Questionnaire (FDCT-N; Fragebogen zur Erfassung des Dyadischen Copings als Tendenz) was designed to assess the three components of the STM: stress communication, support responses, and mutual or common dyadic coping (Bodenmann, 1997). Because it was developed for use in multiple populations, we modified the FDCT-N directions to be cancer-specific. In separate questionnaires, patients and partners were asked to rate: (a) how often they solicit support from each other when they are feeling stressed from the cancer experience (cancer-related stress communication); (b) what their partner usually does when he or she knows they are experiencing cancer-related stress (supportive and unsupportive coping); and (c) what the partners do together to manage cancer-related stress (common positive and negative dyadic coping). Items were rated on a 6-point Likert-type scale (1 = “never” to 6 = “always”); mean scores were computed for each FDCT-N subscale, described below.

Cancer-related stress communication

Four items assessed requests for emotional support (e.g., “I tell my partner openly how I feel and that I would appreciate his or her emotional support”) and practical assistance (e.g., “I ask my partner to do things for me”).

Supportive coping

Seven items assessed the person's perceptions of his or her partner's supportive coping efforts (e.g., conveying empathy and interest, helping to positively reframe the situation, providing information, and taking over tasks or duties).

Unsupportive coping

Five items assessed the person's perceptions of his or her partner's unsupportive coping efforts (e.g., hostility, conveying disinterest, withdrawing, and providing assistance without any real interest or empathy).

Common positive dyadic coping

Three items assessed the frequency with which patients and partners engaged in joint efforts to adaptively manage each other's emotions (e.g., “We sit down to talk together and share our feelings”).

Common negative dyadic coping

One item assessed the frequency with which patients and partners engaged in mutual avoidance, “When we are both stressed, we withdraw and avoid each other.”

Outcome Variables

Cancer-related distress

The 15-item Impact of Event Scale (IES; Horowitz, Wilner, & Alvarez, 1979) was originally developed to assess symptoms of cognitive intrusion (intrusively experienced ideas, images, feelings, or bad dreams) and avoidance (conscious avoidance of certain ideas, feelings, or situations) in response to a traumatic stressor. In this study, participants were asked to estimate the frequency of experiencing intrusive and avoidant thoughts during the past 7 days in response to “your/your partner's metastatic breast cancer” on a 4-point scale (i.e., 0 = not at all, 1 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, and 5 = often). Total scores can range from 0 to 75; scores of 20 or more indicate severe responses, warranting further psychological evaluation. The two subscale scores of intrusive thoughts and avoidance were combined to yield a total score that has been shown to be an indicator of distress in breast cancer patients (Cordova et al., 1995; Cordova, Cunningham, Carlson, & Andrykowski, 2001).

Dyadic adjustment

The 7-item, short version of the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS-7) measures relationship functioning and marital satisfaction (Hunsley, Best, Lefebvre, & Vito, 2001). It has also been found to conserve, without loss of variance, the pattern of relations found between the longer, 32-item DAS and related constructs. Scores can range from 0 to 36; scores less than 21 indicate marital distress.

Sample and Recruitment

Research staff approached 367 female MBC patients and their male partners. Of these, 24 patients (6.5%) were ineligible (7 did not live with their partner; 11 had no pain; 2 did not speak English; and 6 could not provide informed consent). Of the 343 eligible patients remaining, 50 (14.6%) declined participation (4 felt too distressed to participate and 46 were not interested). Comparisons were made between participants and decliners based on available data for age, ECOG performance status, race, average pain (BPI) at time of recruitment, and primary metastatic site. The only significant difference was for pain t(351) = −8.49, p = .001. Patients who agreed to participate had more pain (M = 4.34, SD = 3.02) than those who declined participation (M = 1.44, SD = 1.34).

In 12 cases, we were unable to contact the partner for consent. Couples who consented but did not return surveys within 2 weeks received reminder phone calls, letters, and a second set of mailed surveys. Still, 75 (27%) of the 281 couples who consented did not return their baseline surveys (passive refusal). African American, Hispanic, and Asian patients had a greater likelihood of passive refusal than White patients χ2(3, 273) = 5.79, p = .02. In 15 of the 206 remaining couples, only one person returned the survey (10 patients, 5 partners), resulting in 191 couples with complete baseline data.

Ten patients who completed the baseline survey died or were referred to hospice before the 3-month assessment, so only 181 follow-up surveys were mailed. Of the 138 couples who returned the 3-month surveys, data from both partners was obtained from 122 couples (67% of the 181 mailed out). Before the 6-month survey was mailed, we learned that 8 additional patients died and 22 either dropped out or were lost to follow-up, resulting in a mail-out of 151 surveys. Six couples did not return the 6-month survey because the patient had died. Of the 126 couples (66% of the original 191) who returned the 6-month surveys, 110 couples (73% of the 151 surveys mailed) had complete data. Comparisons were made between patients who completed the study and those who did not based on age, ECOG performance status, race/ethnicity, dyadic adjustment, and distress. No significant differences were found.

Data Analysis Plan

A multilevel modeling approach was used. Multilevel models can handle missing data and therefore maximize the utility of existing data (Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006). This is important given the repeated measures design and sample attrition. In our analyses, data from dyad members were treated as nested scores within the same group (i.e., couple; Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006). In addition, because we obtained measurements from both individuals at three points in time, the overtime component of the data is crossed with individuals within dyads.

To illustrate the multilevel models we used, consider a simple example in which we predict cancer-related distress as a function of a single dyadic coping measure (e.g., common positive dyadic coping). Both variables are measured at three time-points for each partner. The multilevel model we estimated treats both time and person as replications in coming up with the final equation that predicts a person's time-specific distress from his or her time-specific coping.1 Treating the data in this relatively complex multilevel format allows us to: (a) model how each person's predictor scores affected his or her outcomes, controlling for the nonindependence of scores within couples and over time; and (b) examine variables such as social role as moderators to test whether the associations between dyadic coping and cancer-related distress differ based on whether the respondent is a patient or partner.

Because our first goal was to evaluate the unique effect of common dyadic coping on cancer-related distress and dyadic adjustment, we included as predictors in our models length of relationship, the person's cancer-related stress communication and his or her perceptions of the partner's supportive and unsupportive coping efforts.2 In multilevel modeling terms, our models included both time varying and nonvarying predictors. Stress communication, supportive and unsupportive coping, and common positive or negative dyadic coping were time-varying (i.e., lower-level) predictors. Relationship length and social role (patient vs. partner) were time invariant. Separate analyses for each outcome (cancer-related distress and dyadic adjustment) were conducted using SAS Proc Mixed. The predictor variables (all of which were measured for both members of the couple) were grand-mean centered across couples and time (Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006). We also allowed the errors to be auto-correlated by defining the error structure as a lag 1 autoregressive structure (Bolger & Shrout, 2007; Kashy & Donnellan, 2008), and calculated effect sizes using the formula (Snijders & Bosker, 1999).

Our second goal was to evaluate whether the effects of common dyadic coping differed depending on whether the individual was a patient or a partner. Because all the patients in this study were female and all the partners were male, gender and social role could not be untangled. We chose to examine social role as a moderator of the effects of common dyadic coping (as opposed to gender) for two reasons. First, although there is evidence to suggest that gender differences in coping and distress exist (see Hagedoorn et al., 2008), the vast majority of studies have been conducted with single-sex cancers (e.g., breast, prostate) or have analyzed men's and women's data separately. Finding that a variable predicts outcomes for men but not women in different studies or by analyzing men's and women's data separately does not necessarily indicate that the relationship between that variable and the outcome differs significantly between men and women (Campbell & Kashy, 2002). Second, the few dyadic studies that have simultaneously tested for gender and social role effects have yielded mixed results, with some finding gender and social role differences (Hagedoorn, Buunk, Kuijer, Wobbes, & Sanderman, 2000), and others finding only social role differences (Badr, Acitelli, & Carmack Taylor, 2008; Badr & Carmack Taylor, 2008). Because it is not clear whether sex or social role is a stronger predictor of adjustment to cancer and because only one of these could be analyzed in this study, we chose to focus on the effects of social role. Effect coding was used (patients = 1, partners = −1) and interactions between common dyadic coping and social role were examined in models that included the main effects of these variables. Pearson correlations of the medical (i.e., number of comorbidities, length of time since initial diagnosis of breast cancer, BPI average pain at recruitment) and sociodemographic variables (i.e., age, length of relationship, number of children living at home) with the study outcomes were examined to determine potential covariates. We also examined whether there were significant differences in the study outcomes based on stage of initial diagnosis (i.e., stage 4 vs. stages 1, 2, and 3). Only length of relationship had a p value less than .05, and was thus included as a covariate in the multilevel analyses.

Results

Characteristics of the Baseline Sample

Most patients were White (92%), well-educated (70% reported at least 2 years of college study); retired (56%), and married (99%), with wide variation in the length of time married (M = 25.57, SD = 13.02; range 1 to 58 years). Average age was 52.20 years (SD = 10.51; range 23 to 78). Although all patients were initiating treatment for Stage 4 (metastatic) disease at the time of study entry, their stage when initially diagnosed with cancer was 12% Stage 1, 25.5% Stage 2, 20% Stage 3, and 25.5% Stage 4. Seventeen percent did not know or disclose their initial disease stage. Although the average length of time since initial cancer diagnosis was 5.43 years (SD = 5.20; range 5 weeks to 25.6 years), at the time of study entry almost 97% of patients had a physician-rated ECOG performance status score of 0, indicating that they were fully active and able to carry on all predisease performance without restriction. Primary metastatic sites were: 56% bone, 21% lung, 19% liver, and 4% brain. With regard to treatment, 85% of patients were initiating chemotherapy, 11% hormonal therapy, and 4% palliative radiation.

Partners' average age was 54.50 (SD = 10.85; range 24 to 79). The majority were White (93%), well-educated (75% reported at least 2 years of college); and employed full-time (66%).

Levels of Cancer-Related Distress and Dyadic Adjustment

In terms of dyadic adjustment, 22% of patients and 22% of partners scored below the DAS-7 cut-off for marital distress at baseline; in 10% of couples, both partners were below the cut-off. At 3 months, this percentage was slightly higher (28% of patients and 25% of partners; 8% of couples). At 6 months, 21% of patients and 29% of partners were maritally distressed (6% of couples). With regard to cancer-related distress, 47% of patients and 47% of partners met IES criteria for high cancer-related distress at baseline (24% of couples). At 3 months, 48% of patients and 37% of partners had high distress (21% of couples), and at 6 months, 46% of patients and 47% of partners had high distress (23% of couples). For patients, psychological distress and dyadic adjustment did not differ as a function of treatment type.

Dyadic Coping Among Couples Coping With MBC

Table 1 shows the correlations between patients and partners on the major study variables at each assessment; correlations for partners are above the diagonal, correlations for patients are below the diagonal, and partial correlations (between the two partners' scores) are on the diagonal. Of note, patients' and partners' cancer-related distress scores were significantly correlated at each assessment, but their cancer-related stress communication was not.

Table 1 also shows the means, SDs, and paired t test results for each of the major study variables by social role. At each assessment, patients reported significantly more cancer-related stress communication than partners. Patients also rated their partners more favorably with regard to supportive coping than their partners rated them. Patients and partners mostly agreed on the frequency with which they engaged in common positive and common negative dyadic coping; their dyadic adjustment and cancer-related distress scores were also comparable at each assessment.

Multilevel Analyses

Four models were tested to evaluate the degree to which engaging in common positive and negative dyadic coping predicts patients' and partners' cancer-related distress and dyadic adjustment. Analyses are presented first for the outcome of cancer-related distress and then for dyadic adjustment.

Associations between common dyadic coping and cancer-related distress

The first model evaluated whether patients' and partners' common positive dyadic coping at each assessment was associated with their cancer-related distress (IES) at that assessment. To conduct a stringent test of the effects of dyadic coping, we controlled for length of relationship, each person's cancer-related stress communication, and each person's perceptions of his or her partners' supportive and unsupportive coping. We also evaluated whether the effects of common positive dyadic coping differed by social role (1 = patient and −1 = partner).

As found in prior research, a significant main effect for unsupportive coping was found (see Table 2). Holding perceptions of supportive coping constant, patients and partners who perceived their spouses as being more unsupportive experienced greater distress. A significant interaction for common positive dyadic coping × social role was found. To test the simple slopes of the interaction, we used the procedures outlined by Preacher, Curran, and Bauer (2006), developed specifically for multilevel models. Unlike the traditional approach outlined by Aiken and West (1991) that involves inputting values that are 1 SD above and below the mean of the predictor, one advantage of this technique is that it allows one to input the upper and lower possible values of the predictor (here, common positive dyadic coping was centered, so we used the values, −3 and 3).

Table 2.

Effects of Common Positive and Negative Dyadic Coping on Patients' and Partners' Cancer-Related Distress and Dyadic Adjustment

| Cancer-related distress (IES) |

Dyadic adjustment (DAS-7) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | t | Effect size (r) | B | SE | t | Effect size (r) | |

| Common positive dyadic coping | ||||||||

| Intercept | 19.44 | .71 | 25.03 | .24 | ||||

| Length of marriage | −.11 | .06 | −2.00* | .15 | .01 | .02 | .35 | |

| Own cancer-related stress communication | −.44 | .62 | −.71 | .09 | .21 | .41 | ||

| Perceived partner supportive coping | −.02 | .69 | −.03 | .55 | .24 | 2.27* | .08 | |

| Perceived partner unsupportive coping | 3.33 | .76 | 4.40** | .16 | −1.16 | .26 | −4.41** | .16 |

| Social rolea | 1.32 | .59 | 2.25* | .15 | −.31 | .17 | −1.79 | |

| Common positive dyadic coping | .11 | .66 | .16 | 2.10 | .23 | 9.27** | .32 | |

| Common positive dyadic coping × social role | −.91 | .45 | −2.03* | .09 | .16 | .14 | 1.10 | |

| Common negative dyadic coping | ||||||||

| Intercept | 19.43 | .69 | 25.04 | .27 | ||||

| Length of marriage | −.11 | .05 | −1.98* | .15 | −.01 | .02 | −.27 | |

| Own cancer-related stress communication | −.24 | .60 | −.40 | .55 | .21 | 2.58* | .10 | |

| Perceived partner supportive coping | .23 | .64 | .36 | 1.23 | .23 | 5.29** | .20 | |

| Perceived partner unsupportive coping | 2.18 | .78 | 2.79** | .10 | −1.21 | .29 | −4.26** | .16 |

| Social rolea | 1.23 | .57 | 2.15* | .14 | −.58 | .18 | −3.20** | .22 |

| Common negative dyadic coping | 2.16 | .46 | 4.69** | .17 | −.71 | .17 | −4.21** | .16 |

| Common negative dyadic coping × social role | .78 | .39 | 1.98* | .08 | −.11 | .14 | −.78 | |

Note. B = raw coefficient; SE = standard error; effect size .

p < .05.

p < .01.

Effect coding was used for social role such that 1 = patient and −1 = partner.

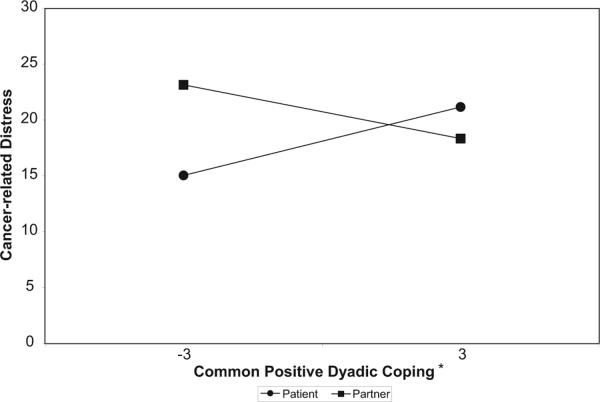

Although patients who used more common positive dyadic coping experienced slightly greater distress than those who used less common positive dyadic coping (see Figure 1), tests of the simple slopes showed that this difference was not significant (b1 = 1.02, t(498) = 1.31, p = .19). Thus, even though engaging in common dyadic coping affected patients and partners differently (i.e., the interaction between patients and partners was significant), within patients, the difference in distress between those who were high versus low on common positive dyadic coping was not statistically significant. Partners who used more common positive dyadic coping experienced less cancer-related distress than those who used less common positive dyadic coping; again, however, the simple slope was not significant (b2 = −.80; t(498) = −.98; p = .33).

Figure 1.

Results of multilevel analysis regressing IES scores on patient and partner reports of common positive dyadic coping. Note. *Common positive dyadic coping was grand mean centered.

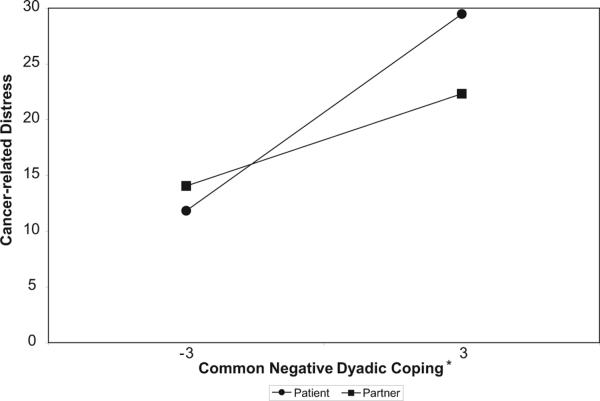

The second model was similar to the first, with the exception that we replaced common positive dyadic coping with common negative dyadic coping as the predictor. As Table 2 shows, a significant main effect for common negative dyadic coping was found. Holding perceptions of supportive and unsupportive coping constant, individuals who used more common negative dyadic coping experienced greater cancer-related distress. The interaction of common negative dyadic coping with social role was also significant (see Figure 2). Tests of the simple slopes showed that patients who used more common negative dyadic coping experienced significantly greater distress than patients who reported less common negative dyadic coping (b1 = 2.94; t(629) = 5.00, p = .001). Partners who reported more common negative dyadic coping also experienced greater distress than partners who reported less common negative dyadic coping (b1 = 1.38; t(629) = 2.26, p = .02).

Figure 2.

Results of multilevel analysis regressing IES scores on patient and partner reports of common negative dyadic coping. Note. *Common negative dyadic coping was grand mean centered.

Associations Between Common Dyadic Coping and Dyadic Adjustment

The final two models mirrored the two described above, with the exception that dyadic adjustment was the outcome instead of cancer-related distress. Specifically, the third model evaluated whether patients' and partners' reports of common positive dyadic coping at each assessment was associated with their dyadic adjustment (DAS-7 scores) at the same assessment, again controlling for length of the relationship, each person's cancer-related stress communication, and each person's perceptions of his or her partners' supportive and unsupportive coping efforts. The model also evaluated whether the effects of common positive dyadic coping on dyadic adjustment differed depending on social role.

Significant main effects were found for social role, supportive and unsupportive coping, and common positive dyadic coping (see Table 2). Specifically, patients had poorer dyadic adjustment than partners. Regardless of role, individuals who perceived their spouses as more supportive and less unsupportive had greater dyadic adjustment. Holding perceptions of supportive and unsupportive coping constant, patients and partners who used more common positive dyadic coping experienced greater dyadic adjustment. The interaction between common positive dyadic coping and social role was not significant.

The final model was the same as the previous one but replaced common positive dyadic coping with common negative dyadic coping. Similar to the results for the previous analysis, significant main effects were found for stress communication, social role, and supportive and unsupportive coping. A significant main effect for common negative dyadic coping was also found. Specifically, holding perceptions of supportive and unsupportive coping constant, patients and partners who used more common negative dyadic coping experienced poorer dyadic adjustment. The interaction between common negative dyadic coping and social role was not significant.

Discussion

Metastatic breast cancer affects both members of the couple. However, even as they are both experiencing extreme stress, patients and partners often act as the primary support provider for each other. Caring for and providing support to a partner who is seriously ill can be deeply rewarding but it can also be stressful, requiring coping efforts that address each individual's well-being as well as the health of the relationship. With these points in mind, this study evaluated the effects of dyadic coping on both partners' adjustment. In a stringent test of dyadic coping, our data showed that common positive dyadic coping was associated with better dyadic adjustment for patients and partners and common negative dyadic coping was associated with greater cancer-related distress and poorer dyadic adjustment even after controlling for length of the relationship, each person's cancer-related stress communication, and their perceptions of their partner's supportive and unsupportive coping efforts.

Although the two individuals' perceptions of their partners' supportive and unsupportive coping were moderately correlated, patients communicated their own stress more often than their partners reported communicating to them. Patients also rated partners as being more supportive than their partners rated them. Taken together, these findings are consistent with studies showing that partners often shield patients from their own distress (Coyne & Smith, 1991; Manne et al., 2007), and are less likely to solicit and receive support than are patients (Glasdam, Jensen, Madsen, & Rose, 1996). This discrepancy raises concerns. When both partners talk openly about their stress it may help open the door for managing the disease in a coordinated way that involves common positive dyadic coping strategies (Bodenmann, 2005; Kayser & Scott, 2008). From a clinical perspective, partners of patients with advanced cancer may feel compelled to focus more on the patient's needs and concerns; however, doing so may ultimately result in increased caregiver role strain and a more complicated bereavement process later on (Bernard & Guarnaccia, 2003). Thus, our findings underscore the need for more couple-focused interventions where the partner's needs and concerns are addressed along with those of the patient (e.g., Kayser, 2005; Kayser & Scott, 2008; Manne et al., 2005).

Common positive dyadic coping may not affect patients and partners in the same way. Whereas patients experienced slight increases in distress, partners experienced slight decreases in distress. Because the decrease in partner distress as a function of common positive dyadic coping was not significant, results should be interpreted with caution. However, they are consistent with published research. For example, in a study of couples coping with chronic illness, Badr and colleagues (2007) demonstrated that viewing one's relationship as an extension of oneself (or having a high level of couple identity) minimized the negative and maximized the positive effects of the caregiving experience on caregiver mental health. A subsequent study in lung cancer showed that working to maintain or enhance the relationship was particularly important for partners' emotional adjustment (Badr & Carmack Taylor, 2008). Engaging in common dyadic coping may help restore a sense of “normalcy” during an otherwise stressful time in a couple's relationship. Relating as spouses (as opposed to caregiver and care-recipient) by continuing to share activities (e.g., relaxing together, problem-solving) may help reduce partners' caregiver burden. It may also provide an opportunity for the partner to continue to seek support from his primary confidant—the patient—thereby reducing his cancer-related distress.

The fact that common dyadic coping requires both persons to actively participate in the coping process together may explain the slight but nonsignificant increase in patient distress. Helping a partner cope while trying to deal with one's own fears and concerns could be emotionally taxing—particularly for MBC patients who may already be experiencing a high degree of physical symptoms and distress. Indeed, nearly half (47%) of patients reported high distress at study entry, when starting treatment for MBC. This rate remained stable across the 6-month study period and is higher than published studies in early stage breast cancer (e.g., Cordova et al., 1995). It is also possible that engaging in open discussions with a partner about serious and sensitive issues (i.e., end of life) may initially increase their salience, resulting in greater intrusiveness or a desire for avoidance. For patients who are already distressed, engaging in common dyadic coping may thus be initially overwhelming; over time, it may bring couples together to develop the emotional resources to address end-of-life concerns. Given that all the patients enrolled were initiating treatment for metastatic disease and the average survival time for patients with MBC is 24 months (Harris, Lippman, Veronesi, & Willett, 1992), the length of the current study (6 months) may not have been sufficient to detect such changes. It is also possible that, because patients with MBC are nearing the end of life, they expect their partners to take on a more active role in the relationship and may not have the emotional resources to fully engage in common dyadic coping. Thus, our findings highlight the different support needs of patients and partners. Future research may benefit from comparisons between couples coping with MBC and those coping with early stage breast cancer to determine when dyadic coping strategies would be most (and least) beneficial to the patient.

Although most participants had good dyadic adjustment at study entry, at least one partner met DAS criteria for marital distress in a third of the original 205 couples surveyed. These rates increased over time, suggesting that this may be an important area for intervention in MBC. Perhaps couples with good relationships from the start find it easier to stay connected, are more committed to each other, and are more motivated to use common positive dyadic coping. Future research should evaluate whether couples should be screened for marital distress upon being diagnosed with MBC and whether the efficacy of couple-focused interventions may depend on couples' initial levels of dyadic adjustment.

This study had some limitations. Because we did not assess dyadic coping patterns before diagnosis, we do not know if couples' reports were specific to MBC or whether they reflected an existing pattern of coping with stress; many of the couples had been married a long time (M = 25.57 years) and were likely to have ingrained patterns of stress communication and coping.

There were also a few measurement concerns. First, dyadic coping was assessed via self-report. However, the moderate agreement between patients' and partners' reports of common dyadic coping suggests that the self-reports approximated actual behaviors. Second, the FDCT-N employs a single-item to measure common negative dyadic coping. Although the use of single-item measures is not optimal, the FDCT-N has been used in numerous published studies and the common negative dyadic coping subscale has been shown to have good predictive validity (Bodenmann, 2005). Finally, the FDCT-N focuses on instances where patients and partners engage in the same behaviors with the same valence (i.e., common positive or negative dyadic coping). Although some studies have suggested that a “mismatch” of coping (e.g., one partner wants to discuss concerns and the other withdraws) is associated with increased distress for both partners (Manne et al., 2006) and can be more destructive to one's well-being than if both partners avoid the issue, others have shown that couples can engage in complementary coping strategies without detriment (Badr, 2004; Revenson, 2003). Future research should thus examine for whom and under what circumstances complementary or common dyadic coping approaches may be more beneficial.

Greater exploration of the cultural context of coping with stress should be a direction for future research. Our sample was relatively homogeneous in terms of race/ethnicity. Because most participants were White, we had insufficient power to examine sociocultural differences. Differences in culture, family structure, and class can all affect the ways in which couples adapt to stressful circumstances.

On a related note, all the patients in this study were women and all the partners were men, so it was impossible to disentangle the possible effects of gender from social role. The marital literature has demonstrated that women in North American cultures think and talk about their relationships more than men and that such thinking and talking can affect men and women differently (Acitelli & Young, 1996). Consistent with this, we found that common dyadic coping differentially impacted patient and spouse distress. However, we also found that taking a team approach to managing cancer-related stress (by engaging in common positive dyadic coping) may generalize to other marital domains by improving or maintaining dyadic adjustment for both persons. More research on sex and role differences and the mechanisms by which common positive dyadic coping affects psychosocial adjustment in two-gender cancers (e.g., lung) may help clarify these findings.

We had considerable passive refusal rates and sample attrition. Because our sample comprised individuals initiating treatment for MBC, completing a lengthy survey may not have been a priority. Noncompletion may have also been due to factors such as psychological and marital distress. Because we did not collect such data at recruitment, we cannot determine whether passive refusers were more or less distressed than study participants. A related issue is sample attrition. A total of 110 of the 191 couples who completed baseline surveys also completed the 3 and 6 month follow-ups (58%); however, 24 women died (13%), suggesting that only 29% dropped out, which is lower than drop-out rates in other prospective studies involving cancer patients and their spouses (e.g., de Groot et al., 2005; Manne et al., 2006). Differences between study completers and noncompleters were examined with regard to baseline physical symptoms, distress, and dyadic adjustment. Although no significant differences were found, those who dropped out may have experienced sharper declines over time.

The effect sizes for the main effects of common positive and negative dyadic coping were low to moderate (r = .16 to .32); however, it is important to keep in mind that this was a stringent test of dyadic coping in that we first controlled for each person's cancer related stress communication and perceptions of his or her partner's supportive and unsupportive coping efforts. In most cases, the main effects for supportive and/or unsupportive coping also were significant, supporting the idea that these are important coping strategies in their own right. It is also interesting to note that in 3 of the 4 multilevel models tested, the main effects for cancer-related stress communication were not significant. Taken together, our main effects findings suggest that perceptions of partners' responses are more strongly related to patient and partner adjustment than the mere disclosure of cancer-related concerns. This is consistent with research demonstrating that disclosing cancer-related concerns to a supportive partner and avoiding unsupportive or critical responses are important components of both partners' psychosocial adjustment to cancer (e.g., Manne, Taylor, Dougherty, & Kerneny, 1997). Our results also extend this literature by suggesting that taking a coordinated approach to managing the shared stresses associated with MBC (i.e., common positive dyadic coping) is a potentially useful strategy for decreasing partner distress and improving both individuals' relationship satisfaction. Helping MBC couples become aware of the added benefits of engaging in common positive dyadic coping may thus help to mold more resilient relationships over time.

Finally, this study examined the effects of engaging in common dyadic coping about cancer-related concerns on cancer-related distress. To date, most couple-focused interventions in cancer have focused on general distress as an outcome. Future research may thus benefit from examining whether the benefits of engaging in common dyadic coping extend to helping alleviate general distress and determining whether cancer-related distress may be a more appropriate target for intervention.

This study also had a number of strengths. Many studies have examined relationship processes in early stage breast cancer. We examined a stage of cancer that has received very little attention but is a growing segment of the survivor population given the multiple treatment options and advances in targeted therapies that are now available for patients with MBC (Mauri, Polyzos, Salanti, Pavlidis, & Loannidis, 2008). Thus, our findings provide potentially useful information to help guide future interventions targeting these couples. To our knowledge, this is the first study to quantitatively evaluate dyadic coping in the context of cancer and to prospectively examine whether engaging in common dyadic coping is associated with cancer-related distress. Future research may benefit from examining dyadic coping in couples coping with other cancers to determine if our results generalize to other cancers and from comparing early stage and MBC couples to determine whether common dyadic coping is more beneficial to those who are in the earlier or latter stages of the disease.

This is one of very few studies to have examined the coping process from both partners' perspectives by considering the effects of social support that is not only provided but also received by patients and their partners. Indeed, few studies collect data from both members of the couple, and those that do often analyze patients' and partners' data separately, failing to take advantage of the richness of dyadic data by analyzing it as we have, with the couple as the unit of analysis. Moreover, the multilevel modeling approach we used allowed us to: (a) control for the nonindependence of patients' and partners' responses; (b) simultaneously evaluate the effects of both persons soliciting and receiving emotional and practical support; and, (c) examine whether social role affected the association between common dyadic coping and psychosocial adjustment. Finally, the prospective design allowed us to model the effects of common dyadic coping on our outcomes of interest.

In summary, our findings underscore the importance of couples working together to manage the shared stresses associated with MBC and its treatment. Future research may benefit from more couple-focused interventions that focus on the interactions between patients and their partners to identify and clarify the ways that both members of the couple can adaptively cope together.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Krystal Davis, Caroline Khalil, Irma Guerrero, Brooke White, and Leslie Schart who assisted with data collection. This research was supported by a multidisciplinary award from the U. S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command W81XWH-0401-0425 and NCI K07124668 (Hoda Badr, Principal Investigator).

Footnotes

There are several types of analyses that are potentially possible for this type of data (see Kashy & Donnellan, 2008; Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006). The most obvious is a growth-curve model in which change in the outcome score over time is predicted by person-level and dyad-level variables. However, given that the key predictors in our analyses were also time-varying, growth-curve models were not well-suited in this case. Such analyses also require that systematic change occurs over time in the dependent variable, and, perhaps surprisingly, this was not the case for this data set (see Table 1). A lagged analysis in which we examine the degree to which variables at time t-1 predict the outcomes as time t, controlling for those same predictors at time t is another possible model. Such an analysis would allow us to look at the truly prospective benefits of coping (i.e., Does dyadic coping “buffer” individuals from cancer-related distress?). Unfortunately, lagged analyses can be very difficult to estimate (a) when the predictors at time t correlate strongly with the predictors at time t-1, and (b) when there are relatively few lags. With only three lags of data, and strong lagged correlations, we were not able to estimate such a model.

Where the Social Role variable was coded as 1 = patient, −1 = spouse. As was the case for the errors in the lower-level model, the variances associated with the lower-level intercepts (d1j and d2j) were allowed to differ for patients and their partners, and were allowed to correlate.

References

- Acitelli LK, Young AM. Gender and thought in relationships. In: Fletcher G, Fitness J, editors. Knowledge structures and interactions in close relationships: A social psychological approach. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1996. pp. 147–168. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage; London: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Badr H. Coping in marital dyads: A contextual perspective on the role of gender and health. Personal Relationships. 2004;11:197–211. [Google Scholar]

- Badr H, Acitelli LK, Carmack Taylor CL. Does couple identity mediate the stress experienced by caregiving spouses? Psychology & Health. 2007;22:211–229. [Google Scholar]

- Badr H, Acitelli LK, Carmack Taylor CL. Does talking about their relationship affect couples' marital and psychological adjustment to lung cancer? Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2008;2:53–64. doi: 10.1007/s11764-008-0044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badr H, Carmack Taylor CL. Effects of relational maintenance on psychological distress and dyadic adjustment among couples coping with lung cancer. Health Psychology. 2008;27:616–627. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.5.616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badr H, Carmack Taylor CL. Sexual dysfunction and spousal communication in couples coping with prostate cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2009;18:735–746. doi: 10.1002/pon.1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baider L, Perez T, DeNour A. Gender and adjustment to chronic disease. General Hospital Psychiatry. 1989;11:1989. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(89)90018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg CA, Upchurch R. A developmental-contextual model of couples coping with chronic illness across the adult life span. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133:920–954. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.6.920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg CA, Wiebe DJ, Butner J, Bloor L, Bradstreet C, Upchurch R, Patton G. Collaborative coping and daily mood in couples dealing with prostate cancer. Psychology and Aging. 2008;23:505–516. doi: 10.1037/a0012687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard LL, Guarnaccia CA. Two models of caregiver strain and bereavement adjustment: A comparison of husband and daughter caregivers of breast cancer hospice patients. The Gerontologist. 2003;43:808–816. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.6.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom J. Social support, accommodation to stress and adjustment to breast cancer. Social Science & Medicine. 1982;16:1329–1338. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(82)90028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenmann G. Dyadic coping-a systemic-transactional view of stress and coping among couples: Theory and empirical findings. European Review of Applied Psychology. 1997;47:137–140. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenmann G. Dyadic coping and its significance for marital functioning. In: Revenson TA, Kayser K, Bodenmann G, editors. Couples coping with stress: Emerging perspectives on dyadic coping. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2005. pp. 33–50. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenmann G, Cina A. Stress and coping as predictors of divorce: A 5-year prospective longitudinal Study. Zeitschrift fur Familienforschung. 2000;12:5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Shrout P. Accounting for statistical dependency in longitudinal data on dyads. In: Little TD, Bovaird JA, Card NA, editors. Modeling ecological and contextual effects in longitudinal studies of human development. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2007. pp. 285–298. [Google Scholar]

- Brown JE, Brown RF, Miller RM, Dunn SM, King MT, Coates AS, Butow PN. Coping with metastatic melanoma: The last year of life. Psycho-Oncology. 2000;9:283–292. doi: 10.1002/1099-1611(200007/08)9:4<283::aid-pon460>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler L, Koopman C, Classen C, Spiegel D. Traumatic stress, life events, and emotional support in women with metastatic breast cancer: Cancer-related traumatic stress symptoms associated with past and current stressors. Health Psychology. 1999;18:555–560. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.6.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler L, Koopman C, Cordova M, Garlan R, DiMiceli S, Spiegel D. Psychological distress and pain significantly increase before death in metastatic breast cancer patients. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2003;65:416–426. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000041472.77692.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell L, Kashy DA. Estimating actor, partner, and interaction effects for dyadic data. Personal Relationships. 2002;9:327–342. [Google Scholar]

- Carmack Taylor CL, Badr H, Lee L, Pisters K, Fossella F, Gritz ER, Schover L. Lung Cancer patients and their spouses: Psychological and relationship functioning within 1 month of treatment initiation. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;36:129–140. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9062-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter CA, Carter RE. Some observations on individual and marital therapy with breast cancer patients and spouses. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 1994;12:65–81. [Google Scholar]

- Cella D, Mahon S, Donovan M. Cancer recurrence as a traumatic event. Behavioral Medicine. 1990;16:15–22. doi: 10.1080/08964289.1990.9934587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cella D, Tross S. Psychological adjustment to survival from Hodgkin's disease. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1986;54:616–662. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.54.5.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleeland C, Syrjala K. How To Assess Cancer Pain. In: Turk D, Melzack R, editors. Handbook of pain assessment. Guilford Press; New York: 1992. pp. 362–387. [Google Scholar]

- Cordova MJ, Andrykowski MA, Kenady DE, McGrath PC, Sloan DA, Redd WH. Frequency and correlates of posttraumatic stress disorder-like symptoms after treatment for breast cancer. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:981–986. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.6.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordova MJ, Cunningham LLC, Carlson CR, Andrykowski MA. Social constraints, cognitive processing, and adjustment to breast cancer. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:706–711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC, Smith DAF. Couples coping with a myocardial-infarction: A contextual perspective on wives distress. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61:404–412. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.3.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Groot JM, Mah K, Fyles A, Winton S, Greenwood S, DePetrillo AD, Devins GM. The psychosocial impact of cervical cancer among affected women and their partners. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer. 2005;15:918–925. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2005.00155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang CY, Manne S, Pape SJ. Functional impairment, marital quality, and patient psychological distress as predictors of psychological distress among cancer patients' spouses. Health Psychology. 2001;20:452–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo M, Fries E, Ingram K. The role of disclosure patterns and unsupportive social interactions in the well-being of breast cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology. 2004;13:96–105. doi: 10.1002/pon.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming DA, Sheppard VB, Mangan PA, Taylor KL, Tallarico M, Adams I, Ingham J. Caregiving at the End of Life: Perceptions of Health Care Quality and Quality of Life Among Patients and Caregivers. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2006;31:407–420. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giese-Davis J, Hermanson K, Koopman C, Weibel D, Spiegel D. Quality of couples' relationship and adjustment to metastatic breast cancer. Journal of Family Psychology. 2000;14:251–266. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.14.2.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasdam S, Jensen AB, Madsen EL, Rose C. Anxiety and depression in cancer patients' spouses. Psycho-Oncology. 1996;5:23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hagedoorn M, Buunk BP, Kuijer RG, Wobbes T, Sanderman R. Couples dealing with cancer: Role and gender differences regarding psychological distress and quality of life. Psycho-Oncology. 2000;9:232–242. doi: 10.1002/1099-1611(200005/06)9:3<232::aid-pon458>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagedoorn M, Sanderman R, Bolks H, Tuinstra J, Coyne JC. Distress in couples coping with cancer: A meta-analysis and critical review of role and gender effects. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;134:1–30. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris JR, Lippman ME, Veronesi U, Willett W. Breast cancer (3) New England Journal of Medicine. 1992;327:473–480. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199208133270706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of Event Scale: A measure of subjective stress. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1979;41:209–218. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197905000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoskins CN, Badker S, Budin W, Ekstrom D, Maislin G, Sherman D, Knauer C. Adjustment among husbands of women with breast cancer. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 1996;14:41–69. [Google Scholar]

- Hunsley J, Best M, Lefebvre M, Vito D. The seven item short form of the dyadic adjustment scale: Further evidence for the construct validity. The American Journal of Family Therapy. 2001;29:325–335. [Google Scholar]

- Kashy DA, Donnellan MB. Comparing MLM and SEM approaches to analyzing developmental dyadic data: Growth curve models of hostility in families. In: Card NA, Selig JP, Little TD, editors. Modeling dyadic and interdependent data in the developmental and behavioral sciences. Routledge; New York: 2008. pp. 165–190. [Google Scholar]

- Kayser K. Enhancing dyadic coping during a time of crisis: A theory-based intervention with breast cancer patients and their partners. In: Revenson TA, Kayser K, Bodenmann G, editors. The psychology of couples and illness. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2005. pp. 175–191. [Google Scholar]

- Kayser K, Scott J. Helping couples cope with women's cancers: An evidence-based approach for practitioners. Springer; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kayser K, Sormanti M. A follow-up study of women with cancer: Their psychosocial well-being and close relationships. Social Work in Health Care. 2002;35:391–406. doi: 10.1300/J010v35n01_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny D, Kashy DA, Cook D. Dyadic data analysis. Guilford Press; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress appraisal and coping. Springer; New York: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis F, Deal L. Balancing our lives: A study of the married couple's experience with breast cancer recurrence. Oncology Nursing Forum. 1995;22:943–953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manne S, Dougherty J, Veach S, Kless R. Hiding worries from one's spouse: Protective buffering among cancer patients and their spouses. Cancer Research Therapy and Control. 1999;8:175–188. [Google Scholar]

- Manne S, DuHamel K, Winkel G, Ostroff J, Parsons S, Martini R. Perceived partner critical and avoidant behaviors as predictors of anxious and depressive symptoms among mothers of children undergoing Hemopaietic stem cell transplantation. Journal Of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:1076–1083. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.6.1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manne S, Norton T, Ostroff J, Winkel G, Fox K, Grana G. Protective buffering and psychological distress among couples coping with breast cancer: The moderating role of relationship satisfaction. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21:380–388. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.3.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manne S, Ostroff J, Norton T, Fox K, Goldstein L, Grana G. Cancer-related relationship communication in couples coping with early stage breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2006;15:234–247. doi: 10.1002/pon.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manne S, Ostroff J, Sherman M, Heyman RE, Ross S, Fox K. Couples' support-related communication, psychological distress and relationship satisfaction among women with early stage breast cancer. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:660–670. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.4.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manne S, Ostroff J, Winkel G, Fox K, Grana G, Miller E, Frazier T. Couple-focused group intervention for women with early stage breast cancer. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:634–646. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manne S, Taylor KL, Dougherty J, Kerneny N. Supportive and negative responses in close relationships: Their association with psychological adjustment among individuals with cancer. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1997;20:101–126. doi: 10.1023/a:1025574626454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massie MJ, Holland J. Depression and the cancer patient. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1990;51:12–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauri D, Polyzos NP, Salanti G, Pavlidis N, Loannidis JPA. Multiple-Treatments Meta-analysis of Chemotherapy and Targeted Therapies in Advanced Breast Cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2008;100:1780–1791. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northouse L, Templin T, Mood D. Couples' adjustment to breast disease during the first year following diagnosis. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2001;24:115–136. doi: 10.1023/a:1010772913717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northouse LL, Dorms G, Charron-Moore C. Factors affecting couples' adjustment to recurrent breast cancer. Social Science and Medicine. 1995;41:69–76. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00302-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northouse LL, Mood D, Kershaw T, Schafenacker A, Mellon S, Walker J, Decker V. Quality of life of women with recurrent breast cancer and their family members. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2002;20:4050–4064. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.02.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberst MT, James RH. Going home: Patient and spouse adjustment following cancer surgery. Topics in Clinical Nursing. 1985;7:46–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter L, Keefe F, Hurwitz H, Faber M. Disclosure between patients with gastrointestinal cancer and their spouses. Psycho-Oncology. 2005;14:1030–1042. doi: 10.1002/pon.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interaction effects in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31:437–448. [Google Scholar]

- Primomo J, Yates BC, Woods NF. Social support for women during chronic illness: The relationship among sources and types to adjustment. Research in Nursing & Health. 1990;13:153–161. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770130304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revenson TA. Scenes from a marriage: The coupling of support, coping, and gender within the context of chronic illness. In: Suls J, Wallston K, editors. Social psychological foundations of health and illness. Blackwell; London: 2003. pp. 530–559. [Google Scholar]

- Scott JL, Halford WK, Ward BG. United we stand? The effects of a couple-coping intervention on adjustment to early stage breast or gynecologic cancer. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:1122–1135. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snijders T, Bosker R. Multilevel analysis. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel D. Cancer and depression. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;168(Suppl. 30):109–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA. Social support as coping assistance. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1986;54:416–423. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.54.4.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderwerker LC, Laff RE, Kadan-Lottick NS, McColl S, Prigerson HG. Psychiatric disorders and mental health service use among caregivers of advanced cancer patients. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23:6899–6907. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitzner MA, McMillan SC, Jacobsen PB. Family caregiver quality of life: Differences between curative and palliative cancer treatment settings. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 1999;17:418–428. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(99)00014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]