Abstract

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) signal through a variety of mechanisms that impact cardiac function, including contractility and hypertrophy. G protein-dependent and -independent pathways each have the capacity to initiate numerous intracellular signaling cascades to mediate these effects. G protein-dependent signaling has been studied for decades and great strides continue to be made in defining the intricate pathways and effectors regulated by G proteins and their impact on cardiac function. G protein-independent signaling is a relatively newer concept that is being explored more frequently in the cardiovascular system. Recent studies have begun to reveal how cardiac function may be regulated via G protein-independent signaling, especially with respect to the ever-expanding cohort of β-arrestin-mediated processes. This review primarily focuses on the impact of both G protein-dependent and β-arrestin-dependent signaling pathways on cardiac function, highlighting the most recent data that illustrate the comprehensive nature of these mechanisms of GPCR signaling.

Keywords: GPCR, G protein, β-arrestin, cardiac contractility, hypertrophy

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) mediate numerous acute regulatory mechanisms involved in the control of cardiovascular function, such as contractility, and chronic processes, such as hypertrophy, that contribute to the development of cardiovascular diseases including heart failure1, 2. Several current drug therapies, such as β-adrenergic receptor (βAR) blockers and angiotensin II receptor (AT1R) blockers, target their GPCRs to prevent hypertrophic signaling and improve clinical outcomes of heart failure patients3. Recent research has shown that some GPCR ligands have the capacity to block hypertrophic signaling pathways while simultaneously promoting cardiac contractility or survival4-7, a property that could improve overall cardiac function relative to conventional GPCR blockers. The ability of a ligand to relay such an effect is possible due to the variety of G protein-dependent and -independent pathways that can be initiated upon GPCR stimulation. G protein-dependent signaling pathways have been explored in the heart for decades, revealing significant roles for the Gαs, Gαi/o, Gαq/11, Gα12/13, and Gβγ families in mediating contractile and/or hypertrophic responses in the heart. Newer to the field of cardiac research, G protein-independent signaling has only been studied for the last 15 years, with specific roles for β-arrestin-mediated signaling in the regulation of cardiac contractility and hypertrophy reported only in the last 5 years. The multitude of cardiac signaling pathways regulated by G proteins and β-arrestins downstream of GPCR activation provides a number of potential targets for pharmacotherapy of heart failure. This review highlights recent molecular studies that provide novel insight into the regulation of cardiac function via G protein- and β-arrestin-dependent signaling.

1. G protein-dependent signaling

The heterotrimeric G protein complex is comprised of a Gα subunit, of which there are four main families (Gαs, Gαi/o, Gαq/11 and Gα12/13) coupled to a combination of Gβ and Gγ subunits, of which there exists 5 and 12 members, respectively. The specific classifications, isoforms and various subunit compositions of the numerous G proteins have been described elsewhere8, 9. The Gα proteins primarily expressed and studied in the heart include Gαs, Gαi1/2/3, Gαq/11 and Gα12/13 (Table 1). GPCR stimulation leads to a change in conformational of the receptor such that it promotes nucleotide exchange at Gα of GDP for GTP9-11. The active GTP-bound form of Gα dissociates from the receptor and Gβγ subunits, and subsequently activates/inhibits downstream effector proteins9, though Gα subtype-selective molecular rearrangement with Gβγ subunits in the absence of dissociation has also been reported12, 13. In recent years, an expansive array of accessory proteins that modulate G protein activity has been described, including activators of G protein signaling (AGS) and regulators of G protein signaling (RGS) proteins14, 15. Members of these families may contain GTPase-activating protein (GAP), guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) or guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitor (GDI) activities, each of which contributes to the regulation of G protein activity. For instance, GEFs act to increase the rate of GTP association with Gα subunits, thereby promoting Gα protein-mediated effects, whereas GDI-containing proteins act to inhibit the dissociation of GDP from Gα subunits, thereby inhibiting Gα protein-mediated signaling14. RGS proteins containing GAP activity accelerate the GTPase activity of Gα subunits, thereby decreasing the amplitude and duration of Gα protein-mediated signaling, though these effects appear to be limited to mainly Gαq/11 and Gαi proteins15. The impact of G protein-dependent signaling via various GPCRs and downstream effector proteins on the regulation of cardiac function will be discussed with regard to the molecular mechanisms by which they impact cardiac contractility and hypertrophy.

Table 1.

Cardiac Gα proteins

| Gα Protein |

Primary Effectors (2nd messengers) |

Downstream Mediators of Signaling |

Functional Effects |

GPCR Examples |

Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gαs | AC (↑cAMP) |

PKA, EPAC, MAPK, CAMKII | ↑Inotropy ↑Chronotropy ↑Hypertrophy |

A2AR, β1AR, RXFP1 | 16, 17, 21, 22, 24, 35, 65, 104-108 |

| Gαi1/2/3 | AC (↓cAMP) |

PI3K, MAPK (via Gβγ scaffolding) | ↓Inotropy ↓Chronotropy ↓Hypertrophy |

β2AR, M2R, S1P1R | 29-31, 40, 41, 47, 109, 110 |

| Gαq/11 | PLCβ (↑DAG and IP3) |

PKC, PKD, CAMKII, MAPK | ↑Inotropy ↑Chronotropy ↑Hypertrophy |

α1AR, AT1R, ETaR | 53, 57, 61-65, 73-75, 77, 78, 80, 82, 88, 89 |

| Gα12/13 | RhoGEFs (↑RhoA activity) [no 2nd messenger] |

ROCK, MAPK | ?Inotropy ?Chronotropy ↑Hypertrophy |

α1AR, AT1R, P2Y6 | 96-100, 102 |

a) G protein-dependent effects on cardiac contractility

cAMP-mediated regulation of cardiac contractility

The mechanisms by which Gαs protein activity enhance heart rate and contractility are best exemplified by β1AR signaling (Fig. 1). β1AR stimulation results in adenylyl cyclase (AC)-mediated generation of cAMP, subsequent protein kinase A (PKA). Via phosphorylation of numerous substrates involved in the contractile response, including the ryanodine receptor (RyR), phospholamban (PLB), the L-type calcium channel (LTCC), cardiac troponin I (cTnI) and cardiac myosin-binding protein C (cMyBP-C), PKA signaling enhances contractile function, as eloquently reviewed elsewhere16. Briefly, PKA-mediated phosphorylation of RyR and LTCC, to increase Ca2+ uptake and sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) release, and PLB, to release its inhibitory effects on the sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase (SERCA) and promote Ca2+ SR storage, and TnI and cMyBP-C, to decrease Ca2+ affinity for the myofilaments and alter crossbridge kinetics, each contribute to the inotropic and lusitopic effects of β-adrenergic stimulation. While few Gαs protein-coupled receptors have been shown to augment inotropy to the same physiologic extent of βAR stimulation, modulation of βAR-dependent effects by other Gαs protein-coupled receptors, as recently demonstrated by type 2 adenosine receptor (A2AR) subtype-specific effects on βAR-mediated contractility17, may be of importance in vivo. Additionally, in the pacemaker cells PKA-mediated phosphorylation of membrane ion channels, as well as Ca2+ handling proteins such as RyR and PLB, tightly controls Ca2+ cycling and heart rate18.

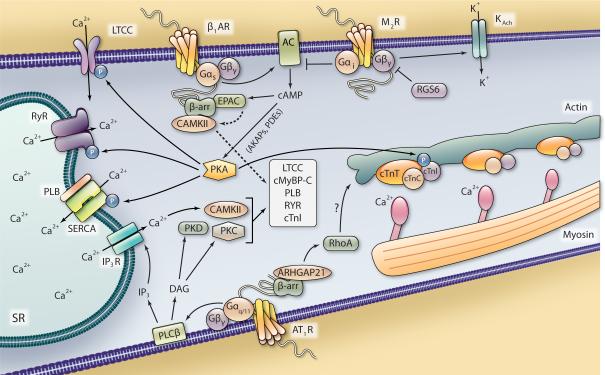

Figure 1. Proposed G protein- and β-arrestin-dependent mechanisms of contractility in ventricular myocytes.

Stimulation of the Gαs-coupled β1AR leads to AC-mediated generation of cAMP and increased PKA activity, which can be regulated in subcellular domains by AKAPs and PDEs. PKA signaling enhances contractility via phosphorylation of cTnI, RyR, LTCC and PLB. Modulation of the contractile machinery as well as Ca2+ entry and release of SR-stared Ca2+, which binds to the myofilaments (actin, myosin and troponin complex), act to induce contraction. A β-arrestin-dependent scaffold including EPAC and CAMKII can be recruited to β1AR upon stimulation, allowing cAMP-EPAC-mediated activation of CAMKII and regulation of contractility. Stimulation of the Gαi-coupled M2R antagonizes AC activity and releases Gβγ subunits that can open K+ channels to hyperpolarize the cardiomyocyte and dampen the contractile response, which is antagonized by RGS6. Stimulation of the Gαq/11-coupled AT1R leads to PLCβ-mediated generation of DAG, which subsequently leads to activation of PKC and PKD, and IP3, which induces the IP3R-mediated release of Ca2+ from the SR that can activate CAMKII, all of which can regulate some or all of the same myofilament and ion channel targets as PKA. β-arrestin scaffolds ARHGAP21 in response to AT1R stimulation, which leads to RhoA activation and effects on cytoskeletal structure, potentially influence cardiac contractility.

cAMP generation also leads to activation of exchange protein activated by cAMP (EPAC), and although the effects of EPAC signaling on contractile function have not been as extensively studied as PKA-mediated effects, EPAC has also been demonstrated to regulate cardiomyocyte Ca2+ handling and myofilament protein phosphorylation19. Through mechanisms involving phospholipase Cε (PLCε), protein kinase Cε (PKCε) and calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CAMKII), EPAC has been shown to increase cTnI, RyR and PLB phosphorylation, Ca2+ release from SR stores and sarcomeric shortening in response to either βAR stimulation or direct EPAC activation20-23. Additionally, an interaction between CAMKII, EPAC1 and the scaffolding proteins β-arrestins 1 and 2 that was enhanced upon β1AR stimulation was demonstrated in the heart (Fig. 1)24. By providing a scaffold for both CAMKII and EPAC1, β-arrestins facilitate β1AR-EPAC-Rap1-PLC-PKC-mediated CAMKII activation and downstream PLB phosphorylation24.

Cardiac electrophysiological processes (for extensive reviews of cardiac electrophysiology refer to 25, 26) have also been shown to be regulated by cAMP-dependent processes, as both PKA and EPAC have been shown to regulate ion channel activity. Whereas PKA-mediated phosphorylation of the ATP-sensitive K+ channel (KATP) increases its activity leading to hyperpolarization27, EPAC activation leads to a Ca2+-calcineurin-dependent dephosphorylation/inactivation of vascular KATP, potentially providing a negative feedback mechanism to inactivate the channel when cAMP levels become very high28. Determination of EPAC-mediated effects on cardiac K+ channel activity and the comparative effects of EPAC versus PKA signaling on the contractile machinery and ion flux specifically in cardiomyocytes requires further exploration.

In opposition to Gαs-mediated signaling, stimulation of cardiac Gαi protein-coupled receptors typically results in negative inotropy and chronotropy via Gαi-dependent inhibition of AC activity, cAMP synthesis and PKA activation. Of the Gαi-linked GPCRs, the muscarinic acetylcholine receptor 2 (M2R) is the primary example of Gαi-mediated parasympathetic antagonism of sympathetic βAR signaling, and has been shown to dampen, or block entirely, βAR-mediated inotropic and chronotropic responses (Fig. 1)29. The ability of Gαi protein-coupled receptors to mediate inhibition of AC activity may depend on membrane localization as the ability of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 (S1P1R) to decrease AC activity and inotropy in adult mouse ventricular myocytes was dependent on compartmentation of S1P1R in caveolae-rich regions of the sarcolemma30, 31.

A kinase-anchoring protein (AKAP)-mediated regulation of cardiac contractility

Via interactions with AKAPs, PKA activity can be tethered to different substrates in subcellular environments, providing precise spatiotemporal regulation of cardiac function32. Studies over that last decade have shown that intracellular targeting of other components of cAMP-mediated signaling immediately downstream of βARs, including AC and cAMP phosphodiesterases (PDE) by AKAPs tightly controls βAR signaling33, as will be discussed in another review in this series. Aside from βAR-AKAP complexes, other GPCRAKAP signaling complexes are beginning to be reported. The relaxin receptor (RXFP1) was recently shown to be precisely regulated by constitutive association with AKAP79-AC2 and β-arrestin 2-PKA-PDE4D3 complexes, which coordinately control local generation and hydrolysis of cAMP in response to low concentrations of relaxin34. While relaxin has been shown to exert positive inotropic and chronotropic responses in the heart35, it is not known whether such an intricate scaffolding system mediates these responses in vivo.

Beyond regulation of local pools of cAMP at the receptor level, AKAPs have also been shown to regulate contractility at the level of the sarcomere as cardiac troponin T (cTnT) has been reported to act as an AKAP, targeting PKA activity to the sarcomere36. In addition, it has been shown that AKAP-9 recruits a macromolecular complex to the cardiac IKs channel consisting of PDE4D3, PKA and protein phosphatase 1 (PP-1), which tightly controls cAMP-induced channel activity and current, thereby modulating cardiac hyperpolarization37. In agreement with the variety of AKAP-mediated effects on cAMP signaling in cardiomyocytes, peptide-mediated disruption of PKA-AKAP interaction in the mouse heart has been shown to act as a negative inotropic, chronotropic and lusitropic stimulus38.

Gβγ-mediated regulation of cardiac contractility

Similar to the function of AKAPs, Gβγ subunits can serve as a protein scaffold8. It has been shown that β2AR-Gαi protein coupling leads to Gβγ-mediated confinement of Gαs-cAMP-PKA signaling via increased phosphoinositide-3-kinase (PI3K) activity39. In particular, Gαi-PI3Kγ-dependent regulation of PDE4 activity was shown to control local cAMP signaling in response to β2AR stimulation and dampen the βAR-mediated inotropic response in cardiomyocytes40, 41. Further, Gβ1 interaction with nucleoside diphosphate kinase B (NDPK B) was shown to regulate basal contractility in several cardiac cell models42-44. The NDPK B-induced transfer of a phosphate to Gβ1 allows the local generation of GTP bound to Gαs and subsequent Gαs activation, AC-mediated cAMP synthesis and cardiomyocyte contractility42, 43, 45. Interestingly this process only impacts receptor-independent cAMP synthesis and cardiomyocyte contractility42, since activated GPCRs, such as βARs, act as GEFs themselves to induce Gαs protein exchange of GDP for GTP11.

Gβγ subunits can also promote negative inotropy via effects on ion channels, as Gβy-mediated inhibition of LTCC current following βAR stimulation has been reported46. Also, via a Gβγ-dependent mechanism, both M2R and S1P1R have been demonstrated in atrial and ventricular myocytes to increase the open probability of the K+ channel IKAch, promoting membrane hyperpolarization to decrease the action potential duration, thereby decreasing chronotropy and inotropy (Fig. 1)31, 47. Via a Gγ-like domain, RGS6 has been shown to interact specifically with Gβ548 and a recent study reported that this complex binds to and promotes the deactivation of IKAch, thereby modulating M2R-mediated effects on myocyte current kinetics49. Since RGS proteins are involved in promoting the reassembly of Gα subunits and Gβγ subunits into the heterotrimeric G protein complex, this study suggests that RGS6 provides a negative feedback mechanism to turn off Gαi-Gβγ-mediated hyperpolarization. Indeed, genetic ablation of RGS6 resulted in prolonged IKAch activity in both atrial myocytes and sinoatrial node cells, leading to bradycardia49.

Gαq/11-mediated regulation of cardiac contractility

Cardiac Gαq/11 protein-coupled receptors increase cardiac inotropy by modulating intracellular Ca2+ levels and contractile protein phosphorylation via PLCβ-mediated conversion of membrane inositol phospholipids into the 2nd messenger products inositol trisphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG)50. Enhanced 2nd messenger signaling downstream of Gαq/11 increases SR-dependent Ca2+ mobilization and activates a number of cardiac PKC isoforms, protein kinase D (PKD) and CAMKII51-53. Collectively, these kinases have been shown to modulate many of the same proteins involved in cardiomyocyte contractility as PKA (Fig. 1)54-61. Although acute stimulation of Gαq/11 protein-coupled receptors increases cardiomyocyte inotropy and chronotropy62-64, the physiological importance of such stimulation compared to βAR-Gαs-mediated inotropy is not well established. However, a number of important Gαq/11-activated signaling pathways can contribute to the regulation of contractility, which may be significant since crosstalk between cardiac Gαq/11 protein-coupled receptors and βAR-Gαs signaling has been established65-68.

LTCC, PLB and RyR each contribute to Ca2+ homeostasis and undergo phosphorylation by PKC and CAMKII signaling2, 59. For instance, phosphorylation of PLB can be increased in a PKCε-dependent manner involving activation of CAMKII22, or can be decreased in a PKCα-dependent manner involving PP-1-mediated dephosphorylation56. Recently, the δC isoform of CAMKII was shown in transgenic mice to mediate an alteration in myocyte Ca2+ handling at the SR involving PLB and that inhibition of its activity specifically at the SR helps to restore diastolic Ca2+ handling69. Several putative PKC phosphorylation sites on LTCC have been reported70, phosphorylation of which augments Ca2+ influx in the cardiomyocyte to promote Ca2+-mediated Ca2+ release from the SR. Different PKC isoforms can mediate LTCC phosphorylation, including PKCα, but excluding PKCε, although it has also been shown that PKCα can transiently decrease LTCC activity via a PI3Kα-dependent mechanism following AT1R stimulation57.

Beyond the control of ion flux, PKC and PKD have also been reported to associate with or phosphorylate components of the cardiac contractile machinery, resulting in differential effects on Ca2+ sensitivity and crossbridge kinetics54, 60, 61. For instance, cTnI has been demonstrated to interact with PKCα following increased Ca2+ signaling, which may result in the maintenance of contractile force58. In addition, cTnI has been shown to undergo phosphorylation by PKCβII to increase Ca2+ sensitivity55, and by PKCα and PKCε to decrease Ca2+ sensitivity in failing human myocardium54. In the latter study, PKCα- and PKCε-dependent phosphorylation of cMyBP-C, which is known to accelerate crossbridge cycling, was also shown to be increased in failing human myocardium. Activated PKD has been demonstrated to phosphorylate cTnI to actually decrease Ca2+ sensitivity71, and may accelerate crossbride cycle kinetics via phosphorylation of cMyBP-C72. Through these combined mechanisms, Gαq/11-mediated signaling has the capacity to regulate precise events involved in cardiac Ca2+ transport and contractility.

b) G protein-dependent effects on cardiac hypertrophy

Gαq/11 protein-mediated effects on cardiac hypertrophy

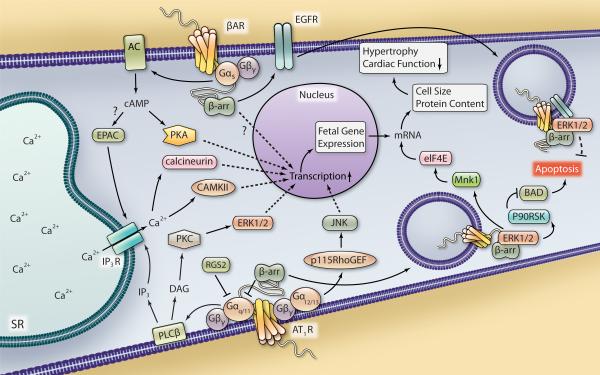

While the physiological relevance of Gαq/11 protein signaling on cardiac contractility may not be as well-established as Gαs protein-mediated effects, Gαq/11 signaling has been shown to play an important role in the development of cardiac hypertrophy51, 73, 74. Cardiac hypertrophy involves enhanced transcriptional activity and cell size, which can be a normal physiologic adaptive response to increased cardiovascular workload, or can contribute to the pathologic development of heart failure75. Increased expression of various isoforms of sarcomeric and metabolic proteins considered to be representative of a developmental phenotype, or “fetal” gene expression, is associated with decreased cardiac function during the progression of hypertrophy and transition to heart failure (Fig. 2)76. The hypertrophic role of Gαq/11 in the heart has been studied using genetic approaches to knockdown or inhibit Gαq/11 in various mouse models of cardiomyopathy, demonstrating that hypertrophic responses to chronic agonist stimulation or pressure overload are reduced or prevented in the absence of Gαq/11 activity, as reviewed by others75, 77. The regulation of Gαq activity by RGS2, which normally dampens Gαq signaling in the heart, has also been shown to influence cardiac hypertrophy. RGS2 knockout mice exhibit enhanced hypertrophic responses to pressure overload compared with RGS2-expressing mice, which include increased calcineurin expression, CAMKII activity and MAPK activity78, suggesting that RGS2-mediated inhibition of Gαq signaling could be an effective means by which to prevent cardiac hypertrophy. Similar results were shown in a recent study exploring the regulation of AT1R-induced MAPK signaling via RGS5 in neonatal cardiomyocytes79.

Figure 2. Proposed G protein- and β-arrestin-dependent regulation of ventricular myocyte hypertrophy and apoptosis.

Stimulation of the AT1R leads to Gαq/11-mediated signaling that can be antagonized by RGS2 and β-arrestin recruitment. PLCβ activity leads to DAG and IP3 generation and downstream activation of PKC, ERK1/2, CAMKII and calcineurin, each of which can increase the transcriptional response in the nucleus. AT1R-Gα12/13-mediated signaling through p115RhoGEF leads to JNK activation that can also regulate transcription. βAR-Gαs stimulation leads to AC-generated cAMP accumulation and increased PKA activity, which can also modulate gene transcription. EPAC activation, possibly downstream of βAR stimulation, also leads to CAMKII and calcineurin activation via Ca2+ mobilization. Increased cardiomyocyte transcription in response to hypertrophic stimuli can lead to an increase in fetal gene expression. β-arrestin-mediated βAR signaling can also regulate hypertrophy via an unknown mechanism. Also, β-arrestin-dependent β1AR-mediated EGFR transactivation decreases cardiac apoptosis, possibly via internalization of a β1AR-EGFR-ERK1/2 complex that directs an unknown cytosolic cell survival response. Internalization of an AT1R-β-arrestin-ERK1/2 complex has been shown to increase Mnk1 activation to enhance eIF4E-mediated mRNA translation, which could contribute to an increase in cell size and protein content, thus hypertrophy and decreased cardiac function in response to hypertrophic stimuli. AT1R-β-arrestin-ERK1/2-mediated activation of p90RSK has been shown to inhibit BAD-induced apoptosis, which could contribute to cardiomyocyte cell survival.

Studies have also begun to comprehensively characterize the transcriptional response to Gαq/11 signaling, revealing hundreds of genes whose expression is altered following Gαq/11 activation. These studies have reported an increase in Gαq/11-dependent transcript detection following stimulation with angiotensin II (Ang II) in HEK 293 cells, or endothelin in rat neonatal cardiomyocytes66, 80, 81. In particular, investigators studying the effects of Ang II on transcription have shown that the Ang II-mediated increases in gene expression is primarily dependent upon Gαq/11 signaling66. By blocking Gαq/11 protein-dependent signaling, antagonists such as AT1R blockers can diminish the hypertrophic transcription response to stimulation by endogenous factors, and reduce the rate of progression of heart failure3.

PLC-PKC-MAPK-mediated effects on cardiac hypertrophy

Aside from the antagonism of Gαq/11 protein-coupled receptors or Gαq/11 itself, inhibition of several downstream regulatory proteins has been shown to interfere with Gαq/11-mediated hypertrophic responses. As discussed above, Gαq/11 activation initiates PLCβ-mediated phospholipid hydrolysis and 2nd messenger generation. A 32-amino acid C-terminal peptide of PLCβ1b was shown to be sufficient to prevent sarcolemmal targeting of PLCβ1b in rat neonatal cardiomyocytes82. By blocking PLC1β1b targeting to the membrane, PLC-mediated 2nd messenger generation and subsequent hypertrophic responses were abrogated in response to α1AR stimulation82. Downstream of PLC, PKC activation leads to phosphorylation of numerous substrates, and in the context of hypertrophy initiation of MAPK signaling is a major route by which Gαq/11-coupled receptors mediate cell growth responses83. In particular, activated PKCs are known to increase ERK1/2 activity in the heart to increase cell growth, effects that can be prevented with PKC inhibition51. Via both cytosolic and nuclear actions, ERK1/2 signaling has been shown in different cell types to increase DNA transcription and mRNA translation84, 85. Such subcellular effects of ERK1/2 have also been demonstrated in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes to contribute to cardiac growth responses, including modulation of proteins involved in gene expression and protein synthesis, such as the nuclear transcription factor family NFAT (nuclear factor of activated T cells) and the ribosomal S6 kinase p70S6K86, 87. Interestingly, it was recently demonstrated that ERK1/2 in particular contributes to concentric cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, or increased cardiomyocyte width, associated with the addition of new sarcomeres, likely mediated via cytosolic pools of activated ERK1/288. Inhibition of ERK1/2 signaling however, led to increased cardiomyocyte length, or eccentric hypertrophy. Inhibition of downstream phosphorylation targets of ERK1/2, including mitogen and stress activated kinase 1 (MSK1) and MAP kinase-interacting kinase 1 (Mnk1), have also been shown to reduce the hypertrophic response to Gαq/11-protein coupled receptors, such as the α1AR, in cardiomyocytes89, 90.

CAMKII-mediated effects on cardiac hypertrophy

In addition to PKC-MAPK signaling, activation of Gαq/11 mediates hypertrophy via other mechanisms. PLCβ-generated IP3 binds to IP3 receptors (IP3R) on the SR to increase the release of stored Ca2+ into the cytosol where it binds calmodulin (CAM). The resulting Ca2+/CAM complex interacts with and activates numerous proteins, including CAMKII and calcineurin (Fig. 2), a protein phosphatase that regulates NFAT and has been shown to play a role in this development of hypertrophy in various models83, 91. The role of CAMKII in hypertrophy and development of heart failure has been extensively studied by the Brown group using various genetic mouse models53. From these studies, the notion that select isoforms of CAMKII can play distinct, but overlapping roles in the promotion of hypertrophic signaling in the heart has emerged. In particular, it was shown that despite differential localization of the δB, and δC cardiac isoforms of CAMKII in the nucleus and cytosol, respectively, transgenic expression of each isoform enhanced cardiac hypertrophic gene expression by promoting histone deacetylase (HDAC) 4 extrusion from the nucleus92. Interestingly, genetic deletion of CAMKIIδ in mice did not prevent the development of hypertrophy, ostensibly due to a compensatory increase in CAMKIIγ activity, but did attenuate heart failure progression following pressure overload due to a loss of altered expression of Ca2+ regulatory proteins93. This reveals a CAMKII isoform-specific transcriptional control of subsets of cardiac proteins. Most recently, CAMKIIδ deletion has been demonstrated to improve cardiac function and reduce remodeling in various mouse models of heart failure53, including myocardial ischemia, ischemia/reperfusion and transgenic overexpression of Gαq. Thus, inhibition of CAMKII signaling appears to be a viable mechanism to attenuate hypertrophy and progression to heart failure, though isoform-specific targeting and compensatory effects may need further exploration.

Gα12/13-mediated effects on cardiac hypertrophy

Contrary to Gαq/11 signaling, Gα12/13 activation does not lead to the generation of 2nd messengers, but to the activation of a small family of RhoGEFs94. RhoGEFs induce the activation of the small GTPase RhoA, which in turn mediates numerous cellular processes through effects on several downstream protein targets95. Although Gα12/13 signaling in the heart is still relatively unexplored, several studies from the Kurose laboratory have shown a role for Gα12/13 in mediating cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis. α1AR, AT1R and ET-1 stimulation were each shown in neonatal cardiomyocytes or cardiac fibroblasts to be capable of inducing hypertrophic or fibrotic responses, mainly via Gα12/13-p115RhoGEF-dependent activation of the MAPK c-Jun NH(2)-terminal kinase (JNK) (Fig. 2)96-99. Another group has also reported that AKAP-Lbc acts both as a scaffold to induce α1AR-mediated p38 MAPK activation and as a RhoGEF to activate RhoA following α1AR-Gα12/13 stimulation in neonatal cardiomyocytes100, 101. In addition, it was shown that either mechanical stretch or direct stimulation of the purinergic P2Y6 receptor increases cardiomyocyte fibrosis via Gα12/13 and that P2Y6 inhibition in vivo prevented fibrosis, but not hypertrophy, in response to pressure overload102. Thus, while Gα12/13 effects in the heart have not been as extensively studied at Gαq/11-mediated effects, they may be important mediators of cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis.

cAMP-dependent effects on cardiac hypertrophy

Although a role for Gαs in the development of hypertrophy has been recognized for many years103, as illustrated via transgenic overexpression of cardiac Gαs 104, 105, the mechanisms controlling hypertrophy downstream of Gαs and cAMP generation remain controversial. At the level of Gαs, a recent study highlighted the ability of RGS2 to influence the hypertrophic response to βAR stimulation, as RGS overexpression in neonatal rat ventricular myocytes diminished βAR-mediated cAMP synthesis, ERK1/2 and Akt phosphorylation and hypertrophy106. Additionally, using selective activators of PKA and EPAC, the authors demonstrated reliance on PKA signaling for the induction of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy with no EPAC-mediated effects on cell growth. Conversely, another group demonstrated a role for EPAC in the hypertrophic responses to both pressure overload and βAR stimulation. In a rat model of aortic constriction, both EPAC1 expression and myocardial hypertrophy increased and it was shown in isolated adult rat ventricular myocytes that the effects of EPAC on cell growth involve Ras, calcineurin and CAMKII signaling107. It was subsequently shown in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes that Ras activation in response to EPAC stimulation was dependent on PLC- and IP3R-mediated increased Ca2+ signaling and that both calcineurin-dependent NFAT transcription and CAMKII-dependent myocyte enhancer factor-2 (MEF-2) activation contributed to the hypertrophic response108. While the mechanisms by which EPAC regulates cardiac hypertrophy are still being explored, there is evidence to support a role for EPAC in this process (Fig. 2) and could provide a novel therapeutic target.

Gαi- and Gβγ- mediated effects on hypertrophy

Both Gαi and Gβγ have been implicated in the development of hypertrophy as well as the progression of heart failure. An increase in cardiac Gαi1 expression was detected in an inducible genetic model of Ras-MAPK mediated hypertrophy, correlating with alterations in the regulation of intracellular Ca2+-handling and leading to ventricular hypertrophy and arrhythmia, both of which were normalized with the inhibition of Gαi via pertussis toxin109. Also, genetic inhibition of Gαi with a cardiac-expressed inhibitory peptide (GiCT) was shown to increase apoptosis following ischemia/reperfusion injury, identifying a cardioprotective role for Gαi during cardiac stress110. More recently, it was shown that small molecule inhibition of Gβγ was able to halt the progression of heart failure in both a neurohormonal and a genetic mouse model of heart failure111. In each model, contractile function was improved with Gβγ inhibition, and the hypertrophic response reduced, as assessed by cardiomyocyte morphology and changes in fetal gene expression. Since small molecule inhibitors of Gβγ have been shown to differentially modulate different Gβγ-dependent signaling pathways8, the potential to selectively inhibit distinct cardiac Gβγ-mediated hypertrophic effects while preserving contractile function could be advantageous.

2. G protein-independent signaling

GPCR-mediated G protein-independent signaling is a newer concept compared to G protein-dependent signaling. The diverse nature of this signaling paradigm has become apparent over the last decade, and great strides have been made in unraveling the roles of G protein-independent signaling in the cardiovascular system. GPCR stimulation and subsequent phosphorylation of C-terminal serine/threonine residues by GPCR kinases (GRKs) relay the primary steps in the induction of G protein-independent signaling by inducing the recruitment of β-arrestins112. Since the role of GRKs in cardiovascular signaling and function will be reviewed elsewhere in this series, the following discussion of G protein-independent signaling will focus upon recent developments in the understanding of the signaling networks used by β-arrestins. β-arrestins 1 and 2 are ubiquitous scaffolding proteins that induce receptor desensitization, internalization as well as numerous signaling mechanisms113. Recently, identification of entire β-arrestin-interacting protein signalosomes via mass spectroscopy has greatly expanded the comprehension of the scope of β-arrestin signaling. In particular, the β-arrestin signalosomes that associate with AT1R before and after Ang II stimulation have been reported in HEK 293 cells, identifying hundreds of proteins that scaffold differentially with β-arrestins 1 and 2114. Additionally, the identification of hundreds of proteins whose phosphorylation status is altered following stimulation of AT1R also reveals entire AT1R-β-arrestin-dependent phosphoproteomes involved in numerous processes including cell growth, cell survival and cytoskeletal reorganization115, 116. Although a majority of studies investigating β-arrestin-mediated effects have focused on the downstream responses to AT1R or βAR stimulation, the increasing array of results and may be applicable to other cardiac GPCR systems as they relate to the control of cardiac contractility and hypertrophy.

a) β-arrestin-mediated effects on cardiac contractility

β-arrestin-dependent cardiomyocyte contractility

In the last five years, β-arrestins have been demonstrated to promote cardiomyocyte and cardiac contractility. Studies using β-arrestin-biased AT1R ligands that do not induce Gαq/11 protein activation have shown that AT1R-β-arrestin-dependent signaling enhances contractility in isolated adult mouse cardiomyocytes5-7. The first study, which utilized the biased ligand [Sar1, Ile4, Ile8]-angiotensin II (SII) and knockout mice to define the roles of each β-arrestin in increasing cardiomyocyte contractility, identified β-arrestin 2, but not β-arrestin 1, as the mediator of this Gαq/11-independent response5. The reliance upon β-arrestin 2 in mediating Gαq/11 protein-independent contractility in response to AT1R stimulation was confirmed in a more recent study utilizing a distinct β-arrestin-biased AT1R ligand6. In addition, unbiased activation of AT1R with Ang II in β-arrestin 2 knockout cardiomyocytes produced a blunted contractile response6, suggesting that β-arrestin 2-mediated effects on contractility may not be redundant with respect to Gαq/11 protein-dependent signaling. Violin et al. have recently demonstrated in whole animals that infusion of synthetic β-arrestin-biased AT1R peptide ligands cause increased cardiac contractility7. Interestingly, while these β-arrestin biased AT1R ligands increased cardiac contractility and decreased blood pressure, they did not alter stroke volume unlike conventional AT1R blockers7. The therapeutic implications for these ligands will be discussed in another review in this series, but these observations demonstrate the potential of targeting β-arrestin-mediated signaling pathways to selectively impact cardiovascular function.

β-arrestin-mediated effects on cytoskeletal reorganization

The mechanism(s) responsible for mediating β-arrestin-dependent cardiomyocyte contractility have not yet been defined, but could involve the aforementioned ability of β-arrestins to scaffold proteins involved in regulating contractility, such as EPAC and CAMKII24. Additionally, cytoskeletal reorganization could play a role in β-arrestin-mediated cardiac contractility. Mechanistic studies in HEK 293 cells have reported β-arrestin-mediated effects on cytoskeletal reorganization, mainly describing effects on the small GTPase RhoA downstream of AT1R. AT1R-β-arrestin 1-mediated signaling has been shown to increase RhoA activation and subsequent stress fiber reorganization, while β-arrestin 2 was shown to have no impact on this process117, highlighting distinct functional roles for β-arrestins 1 and 2 in regulating this intracellular process. In addition, increased β-arrestin 1 association with a Rho GAP (ARHGAP21) following AT1R stimulation was recently demonstrated to promote RhoA activation and stress fiber formation (Fig. 1), while disruption of this interaction diminished RhoA activity and changes in actin reorganization and cell shape118. Perhaps explaining the lack of effect of β-arrestin 2 in mediating RhoA activation downstream of AT1R, it was shown that unlike β-arrestin 1, β-arrestin 2 does not interact with ARHGAP21118. Interestingly, another group reported a dependence on β-arrestin 2, but not β-arrestin 1, in the RhoA-RhoA kinase (ROCK)-dependent regulation of myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) activity and plasma membrane blebbing following AT1R stimulation119. How AT1R stimulation promotes one β-arrestin-mediated pathway over another to confer changes in cytoskeletal organization is not clear, but could depend on local concentrations of the mediators of these effects. While β-arrestin-mediated activation of RhoA signaling is an attractive explanation for increased cardiomyocyte contractility since RhoA activity can impact regulators of cardiac contractility such as PKC and PKD95, the impact of RhoA signaling in β-arrestin-mediated contractility requires exploration.

Additional proteins known to be involved in the regulation of contractility have been demonstrated to interact with β-arrestins or have their phosphorylation status altered in a β-arrestin-dependent manner downstream of AT1R stimulation. These include ROCK, actin, cofilin, myosin and the myosin-binding subunit of myosin phosphatase (MYPT1)114-116, but extend to other proteins involved in more generalized signaling processes. Further, β-arrestin-dependent regulation of Ca2+ transport via transient receptor potential channel (TRP4) has been reported in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC)120. Following Ang II stimulation, a β-arrestin 1-dependent AT1R-TRP4 complex undergoes internalization away from the plasma membrane, reducing cation influx in response to continued AT1R stimulation. Altogether, the expanding roles for β-arrestins in the regulation of cation influx, cytoskeletal structure and cardiomyocyte contractility suggests that they provide a previously unrecognized mechanism to regulate cardiac contractile function. Whether the mechanistic observations reported thus far extend from cell culture models to the heart and apply to cardiac GPCRs other than AT1R remains to be tested.

b) β-arrestin-mediated effects on cardiac hypertrophy

β-arrestin-mediated MAPK activity

Some GPCRs, such as the AT1R, form stable complexes with β-arrestins following ligand stimulation and internalization, which promotes prolonged MAPK signaling compared to G protein-initiated signaling, as exemplified by β-arrestin-ERK1/2 signaling113. Often, G protein-dependent ERK1/2 signaling results in increased nuclear ERK1/2 activity85, 121, however β-arrestin-mediated scaffolding of ERKs has been shown for several receptors to restrict ERK1/2 signaling to the cytosol122-125. The function of this type of ERK1/2 signaling is still being explored, but the major effects of cytosolic β-arrestin-ERK1/2 signaling thus far have been shown to impact processes involved in cardiomyocyte survival and hypertrophy such as apoptosis, discussed below, and protein synthesis84, 125, 126. AT1R-β-arrestin2-dependent cytosolic ERK1/2 signaling allows phosphorylation and activation of ribosomal S6 kinase (p90RSK), shown in neonatal cardiomyocytes to increase DNA synthesis and proliferation125. In addition, Mnk1 has been shown to interact with β-arrestin 2 and become activated in an AT1R-β-arrestin-ERK1/2-dependent manner in VSMC, leading to phosphorylation of the cap binding complex member protein eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) and increased protein synthesis, which could be a mechanism common to cardiomyocytes as well (Fig. 2)84. Interestingly, ERK1/2 activity downstream of some GPCRs has been shown to be reciprocally regulated by β-arrestins 1 and 2. G protein-independent ERK2 activation downstream of the AT1R, for instance, has been demonstrated to be mediated by β-arrestin 2, whereas β-arrestin 1 impedes β-arrestin 2-mediated ERK2 scaffolding and subsequent activation127. Although an initial report has revealed opposing roles for β-arrestins 1 and 2 in the regulation of neointimal hyperplasia128, the consequence of such reciprocal regulation of ERK signaling in the heart has not been studied.

β-arrestin-dependent EGFR transactivation

An additional mechanism by which β-arrestins direct ERK1/2 signaling and may impact cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, as well as survival, is via transactivation of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). Several GPCRs have been reported to induce EGFR transactivation and ERK1/2 activity, which may contribute to hypertrophy129-131. While the molecular pathways involved in this process vary for different GPCRs, a significant role for β-arrestins in βAR-mediated EGFR transactivation has been demonstrated, as siRNA-mediated deletion of either β-arrestin or overexpression of mutant forms of β-arrestins prevents EGFR transactivation, βAR internalization and ERK1/2 activation132-134. The importance of β1AR-mediated EGFR transactivation has been demonstrated in a mouse model of heart failure in which chronic catecholamine stimulation induced dilated cardiomyopathy and increased cardiac apoptosis in mice unable to induce transactivation, compared to mice that were capable of inducing this pathway133. The mechanisms relaying survival in response to β1AR-mediated EGFR transactivation have not been elucidated, but may involve the interaction and cytosolic trafficking of a β1AR-EGFR-ERK1/2 complex in a β-arrestin-dependent manner (Fig. 2)134. Similar to β1AR, urotensin II-mediated EGFR transactivation was recently shown to be β-arrestin-dependent and to reduce cardiac apoptosis in a mouse model of pressure overload compared to mice in which EGFR was inhibited129. However, the role of β-arrestins in GPCR-mediated EGFR transactivation and the effect of this signaling paradigm on cardiomyocyte growth and survival may be GPCR-specific. The Sadoshima group has shown that G protein-independent AT1R-mediated transactivation of EGFR following Ang II stimulation augments isolated cardiac fibroblast proliferation, as well as both cardiac hypertrophy and apoptosis in vivo131, 135, though these studies did not specifically explore β-arrestins in these processes. Conversely, a recent report from Smith et al. indicates that AT1R-mediated EGFR transactivation and subsequent hypertrophy is completely dependent upon Gαq/11 protein coupling in neonatal rat ventricular cardiomyocytes, whereas β-arrestins play no role in this process136. Interestingly, ligand-independent AT1R-mediated EGFR transactivation in the heart in response to mechanical stretch was shown to relay pro-survival signaling, enhancing Akt activation and maintaining lower rates of apoptosis in a β-arrestin 2-dependent manner137. Therefore, EGFR transactivation can enhance both cardiac survival and hypertrophy, though the roles of β-arrestins versus G proteins in mediating these processes appear to be GPCR- and ligand-specific.

β-arrestin-mediated anti-apoptotic signaling

Aside from playing a role in EGFR transactivation-mediated anti-apoptotic signaling, the ability of β-arrestins to negatively regulate apoptosis downstream of various GPCRs has been known for some time138. The mechanisms relaying this effect have not been completely elucidated, though β-arrestin interaction with proteins involved in the regulation of apoptosis have been identified114. Thus far, β-arrestin 2-mediated stabilization of inactive glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK3β) has been shown to contribute to a decrease in apoptosis139, as have interactions of β-arrestins with other proteins. Heat shock protein 27 has been identified as a β-arrestin-interacting protein that confers cytoprotective signaling following β2AR stimulation by decreasing caspase activity140. Also, apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) has been shown to associate with β-arrestins, which promote the ubiquitination and proteosomal degradation of ASK1, thereby decreasing rate of apoptosis141. ERK1/2 signaling has been shown to mediate many β-arrestin-dependent effects, including apoptosis. AT1R-β-arrestin 2-ERK-mediated phosphorylation of p90RSK in VSMC has been demonstrated to promote phosphorylation of BAD (Fig. 2), a regulatory protein involved in the promotion of cellular apoptosis126. p90RSK-mediated phosphorylation of BAD increases its association with the scaffolding protein 14-3-3 and conversely decreases its association with the pro-apoptotic Bcl-xL, thereby diminishing VSMC apoptosis126. This mechanism has since been confirmed by another group studying GLP-1 receptor-β-arrestin 1-mediated effects on apoptosis142. Identification of the mechanisms by which β-arrestins regulate apoptosis downstream of GPCRs specifically in the heart requires additional study, but will help define the impact of β-arrestins on cardiac remodeling during the progression of a pathologic state such as heart failure.

β-arrestin-dependent regulation of gene expression

Recent studies have begun to describe the effect of β-arrestin signaling on gene expression as well as on specific transcriptional regulators. Stimulation of various GPCRs can increase the association of β-arrestins with proteins including the NFκB inhibitor protein IκBα and the histone acetyltransferase p300, which can enhance or diminish transcriptional activity143-145. In addition, β-arrestins have been demonstrated to play a complex role in ETAR-mediated control of β-catenin phosphorylation and nuclear translocation, promoting a transcriptional response in ovarian cancer cells, also reviewed recently146. While many studies exploring the impact of β-arrestin-mediated signaling on transcription have focused on cancer progression, immune responses and CNS signaling145-147, the role of β-arrestins in regulating gene expression in response to cardiac-expressed GPCRs has begun to be characterized. β-arrestin 1 was demonstrated to be essential for the β1AR-mediated increase in protein content and fetal gene expression in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes in response to catecholamine stimulation148. While β-arrestin-1 was demonstrated to be important in this process, the intermediate signaling components between β-arrestin 1 and increased gene expression were not completely elucidated, although a role for Akt was confirmed148, a protein kinase known to be involved in mediating cardiac hypertrophy51.

The role of β-arrestin signaling in the induction of cell proliferation and gene expression has been explored most extensively in response to AT1R stimulation in cell culture models. AT1R-mediated EGFR transactivation was shown to increase VSMC DNA synthesis in a β-arrestin 2-ERK-dependent manner130, though the regulation of gene expression was not directly measured. While Ang II was shown in increase the expression of hundreds of genes in HEK 293 cells, AT1R-β-arrestin-dependent signaling was found to increase the expression of very few genes, indicating that β-arrestins normally act to dampen the AT1R-Gαq/11 protein-induced hypertrophic response without directly contributing to a significant alteration in gene expression66, 81. Although β-arrestin signaling was shown to lack a robust impact on the regulation of genes directly downstream of AT1R, AT1R-β-arrestin signaling was demonstrated to potentiate the gene regulation response induced by β2AR stimulation66. Crosstalk between AT1R- and βAR-induced signaling on cardiomyocyte contractility and ERK activation has been established65, 67, thus could be an important feature of β-arrestin-mediated effects on hypertrophy. AT1R-β-arrestin signaling has also recently been demonstrated to increase phosphorylation of transcriptional regulators commonly associated with distinct GPCR systems116, therefore studying the coordinated effects of multiple stimulated GPCRs could provide a more comprehensive understanding of gene expression changes.

3. Concluding remarks

With the increasingly diverse array of G protein-dependent and -independent signaling pathways identified that contribute to GPCR-mediated regulation of cardiac function, there exist several challenges in trying to interpret and translate them into therapeutic strategies. A significant challenge lies in extrapolating information from the diverse array of model systems used for exploring signaling mechanisms to a clinical setting, especially with regard to β-arrestin-mediated effects on cardiac function. Since G protein-dependent signaling has been investigated for decades, studies have been performed in several neonatal and adult cardiomyocyte cell systems and in whole heart in vivo, giving credence to the importance of these pathways in humans. Still, as more detailed information describing previously unappreciated roles for known effectors or novel regulators of G protein-dependent signaling are reported, further validation of their contribution to the regulation of human cardiac function is needed. Although numerous signaling pathways have been shown to be activated in a β-arrestin-dependent manner, as demonstrated mainly in AT1R- and βAR-focused studies in non-cardiomyocyte cell models, the use of these networks in the regulation of cardiac function under normal or pathologic conditions, and in response to other GPCRs, remains to be fully explored. Another challenge relates to determining the significance of two or more signaling pathways mediating similar processes via modulation of either the same or different targets. For instance, while AT1R stimulation may regulate hypertrophy via Gαq/11-, Gα12/13- and β-arrestin-dependent pathways, is there redundancy in the activation of these pathways, or do they each serve a specific purpose during pathological development of heart failure? As well, the precise spatiotemporal targeting of signaling scaffolds by AKAPs, Gβγ subunits and β-arrestins introduces an extra level of consideration for how GPCR-mediated effects on cardiac function may be fine-tuned. Further complexity lies within the interaction of different receptor systems at a given time in physiologic or pathologic regulation of cardiac function. Since the simultaneous activation of numerous GPCRs has the potential to initiate myriad signaling pathways, how are these independent and/or overlapping events integrated to regulate cardiac contractility and/or hypertrophy? Although assembling a comprehensive interpretation of GPCR-mediated regulation of cardiac function is difficult, it is also exciting as points of interaction between G protein-dependent and -independent pathways continue to be discovered.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

Funding for D.G.T. was supported by NIH grant HL105414-01.

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- α1AR

α1-adrenergic receptor

- AC

adenylyl cyclase

- AKAP

a kinase-anchoring protein

- Ang II

angiotensin II

- ASK1

apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1

- AT1R

angiotensin II type 1 receptor

- βAR

β-adrenergic receptor

- CAMKII

calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II

- cMyBP-C

cardiac myosin-binding protein C

- CREB

cAMP response element binding protein

- cTnI

cardiac troponin I

- cTnT

cardiac troponin T

- DAG

diacylglycerol

- DKG

diacylglycerol kinase

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- eIF4E

eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E

- EPAC

exchange protein activated by cAMP

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- ETAR

endothelin type A receptor

- GAP

GTPase-activating protein (GAP)

- GDI

guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitor

- GEF

guanine nucleotide exchange factor

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- GRK

G protein-coupled receptor kinase

- GSK3β

glycogen synthase kinase-3β

- IP3

inositol trisphosphate

- JNK

c-Jun NH(2)-terminal kinase

- KATP

ATP-sensitive K+ channel

- LTCC

L-type calcium channel

- M2R

muscarinic acetylcholine receptor 2

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MEF

myocyte enhancer factor

- MLCK

myosin light chain kinase

- MMP/ADAM

matrix metalloproteinase/a disintegrin and metalloproteinase

- Mnk

MAP kinase-interacting kinase

- MSK

mitogen and stress activated kinase

- MYPT1

myosin-binding subunit of myosin phosphatase

- NDPK B

nucleoside diphosphate kinase B

- NFAT

nuclear factor of activated T cells

- p70S6K

70 kDa ribosomal S6 kinase

- p90RSK

90 kDa ribosomal S6 kinase

- P2Y6

purinergic P2Y6 receptor

- PDE

phosphodiesterase

- PI3K

phosphoinositide-3-kinase

- PKA

protein kinase A

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PKD

protein kinase D

- PLB

phospholamban

- PLC

phospholipase C

- PP-1

protein phosphatase-1

- RGS

regulators of G protein signaling

- ROCK

RhoA kinase

- RyR

ryanodine receptor

- S1P1R

sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1

- SERCA

sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase

- SII

[Sar1, Ile4, Ile8]-angiotensin II

- SR

sarcoplasmic reticulum

- VSMC

vascular smooth muscle cell

Footnotes

Disclosures

None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Penela P, Murga C, Ribas C, Tutor AS, Peregrin S, Mayor F., Jr. Mechanisms of regulation of G protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRKs) and cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;69:46–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tilley DG, Rockman HA. Role of beta-adrenergic receptor signaling and desensitization in heart failure: new concepts and prospects for treatment. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2006;4:417–432. doi: 10.1586/14779072.4.3.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ma TK, Kam KK, Yan BP, Lam YY. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system blockade for cardiovascular diseases: current status. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1273–1292. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00750.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim IM, Tilley DG, Chen J, Salazar NC, Whalen EJ, Violin JD, Rockman HA. Beta-blockers alprenolol and carvedilol stimulate beta-arrestin-mediated EGFR transactivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:14555–14560. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804745105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rajagopal K, Whalen EJ, Violin JD, Stiber JA, Rosenberg PB, Premont RT, Coffman TM, Rockman HA, Lefkowitz RJ. Beta-arrestin2-mediated inotropic effects of the angiotensin II type 1A receptor in isolated cardiac myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:16284–16289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607583103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tilley DG, Nguyen AD, Rockman HA. Troglitazone stimulates beta-arrestin-dependent cardiomyocyte contractility via the angiotensin II type 1A receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;396:921–926. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Violin JD, SM DE, Yamashita D, Rominger DH, Nguyen L, Schiller K, Whalen EJ, Gowen M, Lark MW. Selectively engaging {beta}-arrestins at the angiotensin II type 1 receptor reduces blood pressure and increases cardiac performance. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;335:572–579. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.173005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smrcka AV. G protein betagamma subunits: central mediators of G protein-coupled receptor signaling. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:2191–2214. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8006-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wettschureck N, Offermanns S. Mammalian G proteins and their cell type specific functions. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:1159–1204. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00003.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hendriks-Balk MC, Peters SL, Michel MC, Alewijnse AE. Regulation of G protein-coupled receptor signalling: focus on the cardiovascular system and regulator of G protein signalling proteins. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;585:278–291. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.02.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang CC, Tesmer JJ. Recognition in the face of diversity: the interactions of heterotrimeric G proteins and G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) kinases with activated GPCRs. J Biol Chem. 2011 doi: 10.1074/jbc.R109.051847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gales C, Van Durm JJ, Schaak S, Pontier S, Percherancier Y, Audet M, Paris H, Bouvier M. Probing the activation-promoted structural rearrangements in preassembled receptor-G protein complexes. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:778–786. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bunemann M, Frank M, Lohse MJ. Gi protein activation in intact cells involves subunit rearrangement rather than dissociation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:16077–16082. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2536719100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sato M, Blumer JB, Simon V, Lanier SM. Accessory proteins for G proteins: partners in signaling. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2006;46:151–187. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.46.120604.141115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sjogren B, Neubig RR. Thinking outside of the “RGS box”: new approaches to therapeutic targeting of regulators of G protein signaling. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;78:550–557. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.065219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bers DM. Cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Nature. 2002;415:198–205. doi: 10.1038/415198a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chandrasekera PC, McIntosh VJ, Cao FX, Lasley RD. Differential effects of adenosine A2a and A2b receptors on cardiac contractility. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;299:H2082–2089. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00511.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maltsev VA, Vinogradova TM, Lakatta EG. The emergence of a general theory of the initiation and strength of the heartbeat. J Pharmacol Sci. 2006;100:338–369. doi: 10.1254/jphs.cr0060018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Metrich M, Berthouze M, Morel E, Crozatier B, Gomez AM, Lezoualc'h F. Role of the cAMP-binding protein Epac in cardiovascular physiology and pathophysiology. Pflugers Arch. 2010;459:535–546. doi: 10.1007/s00424-009-0747-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pereira L, Metrich M, Fernandez-Velasco M, Lucas A, Leroy J, Perrier R, Morel E, Fischmeister R, Richard S, Benitah JP, Lezoualc'h F, Gomez AM. The cAMP binding protein Epac modulates Ca2+ sparks by a Ca2+/calmodulin kinase signalling pathway in rat cardiac myocytes. J Physiol. 2007;583:685–694. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.133066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cazorla O, Lucas A, Poirier F, Lacampagne A, Lezoualc'h F. The cAMP binding protein Epac regulates cardiac myofilament function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:14144–14149. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812536106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oestreich EA, Malik S, Goonasekera SA, Blaxall BC, Kelley GG, Dirksen RT, Smrcka AV. Epac and phospholipase Cepsilon regulate Ca2+ release in the heart by activation of protein kinase Cepsilon and calcium-calmodulin kinase II. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:1514–1522. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806994200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smrcka AV, Oestreich EA, Blaxall BC, Dirksen RT. EPAC regulation of cardiac EC coupling. J Physiol. 2007;584:1029–1031. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.145037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mangmool S, Shukla AK, Rockman HA. beta-Arrestin-dependent activation of Ca(2+)/calmodulin kinase II after beta(1)-adrenergic receptor stimulation. J Cell Biol. 2010;189:573–587. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200911047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nerbonne JM, Kass RS. Molecular physiology of cardiac repolarization. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:1205–1253. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00002.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bers DM. Calcium cycling and signaling in cardiac myocytes. Annu Rev Physiol. 2008;70:23–49. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang Y, Shi Y, Guo S, Zhang S, Cui N, Shi W, Zhu D, Jiang C. PKA-dependent activation of the vascular smooth muscle isoform of KATP channels by vasoactive intestinal polypeptide and its effect on relaxation of the mesenteric resistance artery. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Purves GI, Kamishima T, Davies LM, Quayle JM, Dart C. Exchange protein activated by cAMP (Epac) mediates cAMP-dependent but protein kinase A-insensitive modulation of vascular ATP-sensitive potassium channels. J Physiol. 2009;587:3639–3650. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.173534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boknik P, Grote-Wessels S, Barteska G, Jiang M, Muller FU, Schmitz W, Neumann J, Birnbaumer L. Genetic disruption of G proteins, G(i2)alpha or G(o)alpha, does not abolish inotropic and chronotropic effects of stimulating muscarinic cholinoceptors in atrium. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158:1557–1564. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00441.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Means CK, Miyamoto S, Chun J, Brown JH. S1P1 receptor localization confers selectivity for Gi-mediated cAMP and contractile responses. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:11954–11963. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707422200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Landeen LK, Dederko DA, Kondo CS, Hu BS, Aroonsakool N, Haga JH, Giles WR. Mechanisms of the negative inotropic effects of sphingosine-1-phosphate on adult mouse ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H736–749. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00316.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mauban JR, O'Donnell M, Warrier S, Manni S, Bond M. AKAP-scaffolding proteins and regulation of cardiac physiology. Physiology (Bethesda) 2009;24:78–87. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00041.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dai S, Hall DD, Hell JW. Supramolecular assemblies and localized regulation of voltage-gated ion channels. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:411–452. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Halls ML, Cooper DM. Sub-picomolar relaxin signalling by a pre-assembled RXFP1, AKAP79, AC2, beta-arrestin 2, PDE4D3 complex. EMBO J. 2010;29:2772–2787. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shaw EE, Wood P, Kulpa J, Yang FH, Summerlee AJ, Pyle WG. Relaxin alters cardiac myofilament function through a PKC-dependent pathway. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H29–36. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00482.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sumandea CA, Garcia-Cazarin ML, Bozio CH, Sievert GA, Balke CW, Sumandea MP. Cardiac troponin T, a sarcomeric AKAP, tethers protein kinase A at the myofilaments. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:530–541. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.148684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Terrenoire C, Houslay MD, Baillie GS, Kass RS. The cardiac IKs potassium channel macromolecular complex includes the phosphodiesterase PDE4D3. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:9140–9146. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805366200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patel HH, Hamuro LL, Chun BJ, Kawaraguchi Y, Quick A, Rebolledo B, Pennypacker J, Thurston J, Rodriguez-Pinto N, Self C, Olson G, Insel PA, Giles WR, Taylor SS, Roth DM. Disruption of protein kinase A localization using a trans-activator of transcription (TAT)-conjugated A-kinase-anchoring peptide reduces cardiac function. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:27632–27640. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.146589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jo SH, Leblais V, Wang PH, Crow MT, Xiao RP. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase functionally compartmentalizes the concurrent G(s) signaling during beta2-adrenergic stimulation. Circ Res. 2002;91:46–53. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000024115.67561.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gregg CJ, Steppan J, Gonzalez DR, Champion HC, Phan AC, Nyhan D, Shoukas AA, Hare JM, Barouch LA, Berkowitz DE. beta2-adrenergic receptor-coupled phosphoinositide 3-kinase constrains cAMP-dependent increases in cardiac inotropy through phosphodiesterase 4 activation. Anesth Analg. 2010;111:870–877. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181ee8312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kerfant BG, Zhao D, Lorenzen-Schmidt I, Wilson LS, Cai S, Chen SR, Maurice DH, Backx PH. PI3Kgamma is required for PDE4, not PDE3, activity in subcellular microdomains containing the sarcoplasmic reticular calcium ATPase in cardiomyocytes. Circ Res. 2007;101:400–408. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.156422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hippe HJ, Abu-Taha I, Wolf NM, Katus HA, Wieland T. Through scaffolding and catalytic actions nucleoside diphosphate kinase B differentially regulates basal and beta-adrenoceptor-stimulated cAMP synthesis. Cell Signal. 2011;23:579–585. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hippe HJ, Luedde M, Lutz S, Koehler H, Eschenhagen T, Frey N, Katus HA, Wieland T, Niroomand F. Regulation of cardiac cAMP synthesis and contractility by nucleoside diphosphate kinase B/G protein beta gamma dimer complexes. Circ Res. 2007;100:1191–1199. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000264058.28808.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hippe HJ, Wolf NM, Abu-Taha I, Mehringer R, Just S, Lutz S, Niroomand F, Postel EH, Katus HA, Rottbauer W, Wieland T. The interaction of nucleoside diphosphate kinase B with Gbetagamma dimers controls heterotrimeric G protein function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:16269–16274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901679106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hippe HJ, Wieland T. High energy phosphate transfer by NDPK B/Gbetagammacomplexes--an alternative signaling pathway involved in the regulation of basal cAMP production. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2006;38:197–203. doi: 10.1007/s10863-006-9035-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Volkers M, Weidenhammer C, Herzog N, Qiu G, Spaich K, von Wegner F, Peppel K, Muller OJ, Schinkel S, Rabinowitz JE, Hippe HJ, Brinks H, Katus HA, Koch WJ, Eckhart AD, Friedrich O, Most P. The Inotropic Peptide {beta}ARKct Improves {beta}AR Responsiveness in Normal and Failing Cardiomyocytes Through G{beta}{gamma}-Mediated L-Type Calcium Current Disinhibition. Circ Res. 2011;108:27–39. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.225201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nikolov EN, Ivanova-Nikolova TT. Dynamic integration of alpha-adrenergic and cholinergic signals in the atria: role of G protein-regulated inwardly rectifying K+ channels. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:28669–28682. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703677200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Anderson GR, Posokhova E, Martemyanov KA. The R7 RGS protein family: multi-subunit regulators of neuronal G protein signaling. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2009;54:33–46. doi: 10.1007/s12013-009-9052-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Posokhova E, Wydeven N, Allen KL, Wickman K, Martemyanov KA. RGS6/Gss5 complex accelerates IKACh gating kinetics in atrial myocytes and modulates parasympathetic regulation of heart rate. Circ Res. 2010;107:1350–1354. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.224212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Docherty JR. Subtypes of functional alpha1-adrenoceptor. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67:405–417. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0174-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dorn GW, 2nd, Force T. Protein kinase cascades in the regulation of cardiac hypertrophy. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:527–537. doi: 10.1172/JCI24178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Avkiran M, Rowland AJ, Cuello F, Haworth RS. Protein kinase d in the cardiovascular system: emerging roles in health and disease. Circ Res. 2008;102:157–163. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.168211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mishra S, Ling H, Grimm M, Zhang T, Bers DM, Brown JH. Cardiac Hypertrophy and Heart Failure Development Through Gq and CaM Kinase II Signaling. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2010 doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181e1d263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kooij V, Boontje N, Zaremba R, Jaquet K, dos Remedios C, Stienen GJ, van der Velden J. Protein kinase C alpha and epsilon phosphorylation of troponin and myosin binding protein C reduce Ca2+ sensitivity in human myocardium. Basic Res Cardiol. 2010;105:289–300. doi: 10.1007/s00395-009-0053-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang H, Grant JE, Doede CM, Sadayappan S, Robbins J, Walker JW. PKC-betaII sensitizes cardiac myofilaments to Ca2+ by phosphorylating troponin I on threonine-144. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;41:823–833. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Braz JC, Gregory K, Pathak A, Zhao W, Sahin B, Klevitsky R, Kimball TF, Lorenz JN, Nairn AC, Liggett SB, Bodi I, Wang S, Schwartz A, Lakatta EG, DePaoli-Roach AA, Robbins J, Hewett TE, Bibb JA, Westfall MV, Kranias EG, Molkentin JD. PKC-alpha regulates cardiac contractility and propensity toward heart failure. Nat Med. 2004;10:248–254. doi: 10.1038/nm1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liang W, Oudit GY, Patel MM, Shah AM, Woodgett JR, Tsushima RG, Ward ME, Backx PH. Role of phosphoinositide 3-kinase {alpha}, protein kinase C, and L-type Ca2+ channels in mediating the complex actions of angiotensin II on mouse cardiac contractility. Hypertension. 2010;56:422–429. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.149344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Molnar A, Borbely A, Czuriga D, Ivetta SM, Szilagyi S, Hertelendi Z, Pasztor ET, Balogh A, Galajda Z, Szerafin T, Jaquet K, Papp Z, Edes I, Toth A. Protein kinase C contributes to the maintenance of contractile force in human ventricular cardiomyocytes. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:1031–1039. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807600200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Couchonnal LF, Anderson ME. The role of calmodulin kinase II in myocardial physiology and disease. Physiology (Bethesda) 2008;23:151–159. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00043.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Haworth RS, Cuello F, Herron TJ, Franzen G, Kentish JC, Gautel M, Avkiran M. Protein kinase D is a novel mediator of cardiac troponin I phosphorylation and regulates myofilament function. Circ Res. 2004;95:1091–1099. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000149299.34793.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cuello F, Bardswell SC, Haworth RS, Ehler E, Sadayappan S, Kentish JC, Avkiran M. Novel Role for p90 Ribosomal S6 Kinase in the Regulation of Cardiac Myofilament Phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:5300–5310. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.202713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ishihata A, Endoh M. Species-related differences in inotropic effects of angiotensin II in mammalian ventricular muscle: receptors, subtypes and phosphoinositide hydrolysis. Br J Pharmacol. 1995;114:447–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb13247.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Proven A, Roderick HL, Conway SJ, Berridge MJ, Horton JK, Capper SJ, Bootman MD. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate supports the arrhythmogenic action of endothelin-1 on ventricular cardiac myocytes. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:3363–3375. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhai P, Yamamoto M, Galeotti J, Liu J, Masurekar M, Thaisz J, Irie K, Holle E, Yu X, Kupershmidt S, Roden DM, Wagner T, Yatani A, Vatner DE, Vatner SF, Sadoshima J. Cardiac-specific overexpression of AT1 receptor mutant lacking G alpha q/G alpha i coupling causes hypertrophy and bradycardia in transgenic mice. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3045–3056. doi: 10.1172/JCI25330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Barki-Harrington L, Luttrell LM, Rockman HA. Dual inhibition of beta-adrenergic and angiotensin II receptors by a single antagonist: a functional role for receptor-receptor interaction in vivo. Circulation. 2003;108:1611–1618. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000092166.30360.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Christensen GL, Knudsen S, Schneider M, Aplin M, Gammeltoft S, Sheikh SP, Hansen JL. AT(1) receptor Galphaq protein-independent signalling transcriptionally activates only a few genes directly, but robustly potentiates gene regulation from the beta2-adrenergic receptor. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;331:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cervantes D, Crosby C, Xiang Y. Arrestin orchestrates crosstalk between G protein-coupled receptors to modulate the spatiotemporal activation of ERK MAPK. Circ Res. 2010;106:79–88. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.198580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dorn GW, 2nd, Tepe NM, Wu G, Yatani A, Liggett SB. Mechanisms of impaired beta-adrenergic receptor signaling in G(alphaq)-mediated cardiac hypertrophy and ventricular dysfunction. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;57:278–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Huke S, Desantiago J, Kaetzel MA, Mishra S, Brown JH, Dedman JR, Bers DM. SR-targeted CaMKII inhibition improves SR Ca(2+) handling, but accelerates cardiac remodeling in mice overexpressing CaMKIIdelta(C). J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;50:230–238. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yang L, Doshi D, Morrow J, Katchman A, Chen X, Marx SO. Protein kinase C isoforms differentially phosphorylate Ca(v)1.2 alpha(1c). Biochemistry. 2009;48:6674–6683. doi: 10.1021/bi900322a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Goodall MH, Wardlow RD, 2nd, Goldblum RR, Ziman A, Lederer WJ, Randall W, Rogers TB. Novel function of cardiac protein kinase D1 as a dynamic regulator of Ca2+ sensitivity of contraction. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:41686–41700. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.179648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bardswell SC, Cuello F, Rowland AJ, Sadayappan S, Robbins J, Gautel M, Walker JW, Kentish JC, Avkiran M. Distinct sarcomeric substrates are responsible for protein kinase D-mediated regulation of cardiac myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity and cross-bridge cycling. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:5674–5682. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.066456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Adams JW, Sakata Y, Davis MG, Sah VP, Wang Y, Liggett SB, Chien KR, Brown JH, Dorn GW., 2nd Enhanced Galphaq signaling: a common pathway mediates cardiac hypertrophy and apoptotic heart failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:10140–10145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.10140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.D'Angelo DD, Sakata Y, Lorenz JN, Boivin GP, Walsh RA, Liggett SB, Dorn GW., 2nd Transgenic Galphaq overexpression induces cardiac contractile failure in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:8121–8126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.8121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dorn GW., 2nd Physiologic growth and pathologic genes in cardiac development and cardiomyopathy. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2005;15:185–189. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Taegtmeyer H, Sen S, Vela D. Return to the fetal gene program: a suggested metabolic link to gene expression in the heart. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1188:191–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05100.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Barry SP, Davidson SM, Townsend PA. Molecular regulation of cardiac hypertrophy. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:2023–2039. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Takimoto E, Koitabashi N, Hsu S, Ketner EA, Zhang M, Nagayama T, Bedja D, Gabrielson KL, Blanton R, Siderovski DP, Mendelsohn ME, Kass DA. Regulator of G protein signaling 2 mediates cardiac compensation to pressure overload and antihypertrophic effects of PDE5 inhibition in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:408–420. doi: 10.1172/JCI35620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Li H, He C, Feng J, Zhang Y, Tang Q, Bian Z, Bai X, Zhou H, Jiang H, Heximer SP, Qin M, Huang H, Liu PP, Huang C. Regulator of G protein signaling 5 protects against cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis during biomechanical stress of pressure overload. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:13818–13823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008397107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cullingford TE, Markou T, Fuller SJ, Giraldo A, Pikkarainen S, Zoumpoulidou G, Alsafi A, Ekere C, Kemp TJ, Dennis JL, Game L, Sugden PH, Clerk A. Temporal regulation of expression of immediate early and second phase transcripts by endothelin-1 in cardiomyocytes. Genome Biol. 2008;9:R32. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-2-r32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lee MH, El-Shewy HM, Luttrell DK, Luttrell LM. Role of beta-arrestin-mediated desensitization and signaling in the control of angiotensin AT1a receptor-stimulated transcription. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:2088–2097. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706892200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]