Abstract

Objective

The goal of this study was to determine whether the physiological effects of carbon dioxide (CO2) involve regulation of CGRP secretion from trigeminal sensory neurons.

Background

The neuropeptide calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) is implicated in the pathophysiology of allergic rhinosinusitis and migraine. Recent clinical evidence supports the use of noninhaled intranasal delivery of 100% CO2 for treatment of these diseases. Patients report 2 distinct physiological events: first, a short duration stinging or burning sensation within the nasal mucosa, and second, alleviation of primary symptoms.

Methods

Primary cultures of rat trigeminal ganglia were utilized to investigate the effects of CO2 on CGRP release stimulated by a depolarizing stimulus (KCl), capsaicin, nitric oxide, and/or protons. The amount of CGRP secreted into the culture media was determined using a CGRP-specific radioimmunoassay. Intracellular pH and calcium levels were measured in cultured trigeminal neurons in response to CO2 and stimulatory agents using fluorescent imaging techniques.

Results

Incubation of primary trigeminal ganglia cultures at pH 6.0 or 5.5 was shown to significantly stimulate CGRP release. Similarly, CO2 treatment of cultures caused a time-dependent acidification of the media, achieving pH values of 5.5–6 that stimulated CGRP secretion. In addition, KCl, capsaicin, and a nitric oxide donor also caused a significant increase in CGRP release. Interestingly, CO2 treatment of cultures under isohydric conditions, which prevents extracellular acidification while allowing changes in PCO2 values, significantly repressed the stimulatory effects of KCl, capsaicin, and nitric oxide on CGRP secretion. We found that CO2 treatment under isohydric conditions resulted in a decrease in intracellular pH and inhibition of the KCl- and capsaicin-mediated increases in intracellular calcium.

Conclusions

Results from this study provide the first evidence of a unique regulatory mechanism by which CO2 inhibits sensory nerve activation, and subsequent neuropeptide release. Furthermore, the observed inhibitory effect of CO2 on CGRP secretion likely involves modulation of calcium channel activity and changes in intracellular pH.

Keywords: calcium, CGRP, carbon dioxide, migraine, protons, rhinitis

The trigeminal nerve consists of 3 main branches, the ophthalmic, maxillary, and mandibular, each innervating distinct regions of the head and face. Activation and sensitization of trigeminal ganglion nerve fibers is thought to play a role in the pathophysiology of migraine and rhinitis. Migraine is a chronic, painful, neurovascular disorder that affects an estimated 12% of the population.1,2 It is thought that activation of trigeminovascular afferents in the dura releases neuropeptides causing vasodilation and inflammation. Release of the neuropeptides in the central nervous system is thought to contribute to pain, central sensitization, and allodynia.3,4 Similar pathophysiological mechanisms are thought to be involved in rhinitis, an inflammatory condition involving the mucous membranes of the nasal cavity,5 affecting an estimated 40 million Americans.6 Inflammation of the nasal mucosa causes activation of trigeminal nerve fibers and paracrine release of neuropeptides that cause blood vessel dilation and increased glandular secretion.7–9

Trigeminal ganglion neurons synthesize and release a number of peptides such as substance P, neurokinin A, and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) that mediate inflammation and nociception. Increased expression and release of CGRP is implicated in the pathophysiology of migraine10–13 and rhinitis.14,15 CGRP is one of the most potent vasodilators known16,17 and relays painful stimuli from the periphery to the central nervous system.10,18 In addition, CGRP has been reported to cause release of histamine from rat dural mast cells and is involved in the recruitment and activation of immune cells.15,19–21 Not surprisingly, drugs such as the triptans that inhibit CGRP release from trigeminal neurons have proven effective in the treatment of migraine.4,13

Data from phase II clinical trials recently presented at scientific meetings have provided evidence that a new therapeutic approach provides relief of allergic rhinitis and migraine headache.22,23 The method involves 100% carbon dioxide (CO2), administered at a flow rate of 10 mL/second through one nostril while holding the breath or breathing through the mouth. There are 2 major physiological events reported by patients. First, patients report an almost immediate burning/stinging sensation within the nose that typically lasts less than 10 seconds. The second major event is relief of the symptoms of allergic rhinitis and the pain of migraine headache. The cellular mechanism by which CO2 mediates these quite different physiological events is currently unknown. However, they likely involve extracellular and intracellular acidosis, respectively, caused by the generation of protons via carbonic anhydrase activity.24

In this study, we used trigeminal ganglion cultures to investigate the cellular effects of 100% CO2 on CGRP secretion under conditions that either allowed or prevented extracellular acidosis. Based on our findings, we propose that the inhibitory effect of CO2 on CGRP secretion involves a decrease in intracellular pH and inhibition of calcium channel activity. Furthermore, our results may help to explain the reported benefits of CO2 in the treatment of migraine headache and allergic rhinitis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Primary cultures of trigeminal ganglia were used to investigate the cellular effects of 100% CO2 on CGRP secretion from trigeminal neurons under conditions that either allowed or prevented extracellular acidosis. The effects of extracellular versus intracellular pH changes mediated by CO2 on CGRP secretion and intracellular pH and calcium levels were determined by allowing PCO2 to change while controlling extracellular pH, a condition termed isohydric hypercapnia.25–27

Cell Culture

All animal care and procedures were conducted in accordance with institutional and National Institutes of Health guidelines. Adult female Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories Inc., Wilmington, MA, USA) were housed in clean plastic cages on a 12-hour light/dark cycle with unrestricted access to food and water. Primary cultures of trigeminal ganglia were established based on our previously published protocols.28–30 Briefly, cells from ganglia isolated from 3–5 day old rats were resuspended in L15 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals, Norcross, GA, USA), 50 mM glucose, 250 μM ascorbic acid, 8 μM glutathione, 2 mM glutamine, and 10 ng/mL mouse 2.5 S nerve growth factor (Alomone Laboratories, Jerusalem, Israel). Penicillin (100 units/mL), streptomycin (100 μg/mL), and amphotericin B (2.5 μg/mL, Sigma) were also added to the supplemented L15 media, which will be referred to as L15 complete medium. For secretion studies, dissociated cells from the equivalent of 24 ganglia were plated on 24-well poly-D-lysine coated tissue culture plates (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA, USA) and incubated at 37°C at ambient CO2. For the pH and calcium measurements, trigeminal cultures were enriched in neuronal cells (>90%) by density-gradient centrifugation as previously described.29,30 Briefly, after dissociation, the cell pellet was resuspended in 3-mL plating medium containing 1 mg/mL bovine serum albumin (BSA). Cells were carefully layered onto 6 mL of plating medium containing 10 mg/mL BSA in a 15-mL conical tube and centrifuged at 100 × g for 3 minutes. The pellet was resuspended in L15 complete medium and plated as described above at a density of 1.5–2 ganglion per well in a 24-well plate, which corresponds to 50,000–65,000 cells per well.

Trigeminal ganglion primary cultures maintained for 48 hours in L15 complete medium were incubated in 250 μL per well of HEPES-buffered saline (HBS; 22.5 mM HEPES, 135 mM NaCl, 3.5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 3.3 mM glucose, and .1% BSA, pH 7.4). The amount of CGRP released into the HBS medium was determined using a CGRP-specific radioimmunoassay (Bachem/Peninsula Laboratories Inc., San Carlos, CA, USA). The basal (unstimulated) amount of CGRP secreted into the medium in 1 hour was determined and was used to normalize for differences between the wells. The effects of increasing proton concentrations on CGRP secretion was determined by incubating the cells for 1 hour in HBS at pH 7.4, 7.0, 6.5, 6.0, and 5.5 and the amount of CGRP measured.

Effect of CO2 on Medium pH

The effect of increasing 100% CO2 exposure on the pH of different buffered solutions alone was initially determined. HBS pH 7.4 or HBS pH 7.4 with 100-mM bicarbonate and 100-mM phosphate, was added to coverslips (80 μL) and placed in a saturated CO2 chamber for 90, 180, or 300 seconds. Immediately after CO2 exposure, the solutions were removed and pH measured. As expected, the addition of bicarbonate and phosphate to HBS prevented the decrease in extracellular pH observed with HBS alone.

Effect of CO2 on CGRP Secretion

For the CO2 studies on trigeminal ganglion cells, cultures plated and maintained on coverslips were removed from the 24-well plate and placed in a saturated CO2 chamber for 300 seconds. Prior to CO2 treatment, the cells were covered with 80 μL HBS or isohydric medium (20 mM HEPES, 100 mM phosphate, 100 mM sodium bicarbonate) to prevent external pH changes. Medium was removed and assayed 5 minutes after CO2 exposure and again 60 minutes after being returned to normal incubation conditions (37°C, ambient CO2). Following removal of medium from cultures exposed to CO2, fresh medium was added to the cultures. Cultures were either left untreated (control) or treated with 60 mM KCl, 2 μM 8-methyl-N-vanillyl-6-nonenamide (capsaicin; Sigma), or 1 mM NO donor, S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP; Sigma) for 60 minutes and the amount of secreted CGRP measured. KCl treatment causes chemical depolarization of neurons in general, while capsaicin selectively activates nociceptive C-fibers. As a control, cultures were treated with equivalent amounts of the appropriate vehicle (dimethyl sulfoxide for both capsaicin and SNAP) and the amount of secreted CGRP determined. To test for cytotoxic effects of the various treatments, neuronal survival was assessed in trigeminal ganglion cultures immediately after treatment and 24 hours later, using the trypan blue exclusion method as previously described.30 Each experimental condition was performed in duplicate and repeated in at least 5 independent experiments. The data are reported as mean ± SEM and values were normalized to basal levels. Statistical analysis was performed using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U-test. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < .05. All statistical tests were preformed using Minitab Statistical Software, Release 14.

Intracellular pH Measurements

For intracellular pH imaging, cells were plated at a density of 1.5–2 ganglia per well on poly-D-lysine coated, plastic, or glass coverslips. Cells were incubated with SNARF-4FM loading dye following manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen Inc., Carlsbad, CA, USA) and a previously published protocol.31 Briefly, SNARF-4FM and pleuronic acid (Invitrogen Inc.) were added to culture media at final concentrations of 5 μM and incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes. Fresh medium was used to rinse the coverslips once and the plate was incubated for another 30 minutes. Individual coverslips were placed in isohydric medium, pH 7.4, in a white-walled, clear-bottomed 24-well plate and analyzed using a Victor 3V plate reader following manufacturer’s instructions (Perkin Elmer, Wellesley, MA, USA), with wavelengths set at 572 nm and 665 nm for 1 second counts at 20 second intervals. Basal levels were taken from each well for 5 minutes before addition of stimulatory agents. Initially, the relative change in intracellular pH in cultured cells in response to incubation in isohydric media at acidic pH and containing nigericin (10 μM; Sigma) was determined. The ionophore nigericin is commonly used to equilibrate intracellular pH.31 Cells were incubated in isohydric medium at pH 5.5,6.0, and 6.5 for 5 minutes at 37°C. For experiments designed to measure intracellular pH changes in response to CO2 exposure, coverslips were placed in a sealed chamber saturated with 100% CO2 for 5 minutes prior to pH measurement. Data were reported as the ratio of the 572 to 665 nm wavelength measurements and, thus, are the averages of all the cells in each well. Each experimental condition was repeated a minimum of 3 times. Results of intracellular pH imaging are shown relative to basal levels under similar culture conditions.

Intracellular Calcium Measurements

For intra-cellular calcium imaging, plating conditions were identical to those used for the pH imaging studies. Cells were incubated with Fura-2AM and pleuronic acid (Invitrogen Inc.) at final concentrations of 5 μM, using a similar protocol as previously described.28,32 Absorbance was determined at 340 and 380 nm for 1 second counts at 20 second intervals in a Victor 3V plate reader following manufacturer’s instructions (Perkin Elmer). Basal levels were obtained for 5 minutes before treatment with 60 mM KCl, 2 μM capsaicin, or 5 minutes of 100% CO2 in a sealed chamber. After addition of stimulatory agents or CO2 exposure, intracellular calcium levels were determined for an additional 5 minutes. In some wells treated with CO2, cultures were subsequently treated with 60 mM KCl or 2 μM capsaicin and intracellular calcium levels measured for another 5 minutes. Data are reported as the ratio of the 340–380 wavelength measurements and, thus, are the averages of all the cells in each well. Each experimental condition was repeated a minimum of 3 times. Results of intracellular Ca2+ imaging are shown relative to basal levels under similar culture conditions.

RESULTS

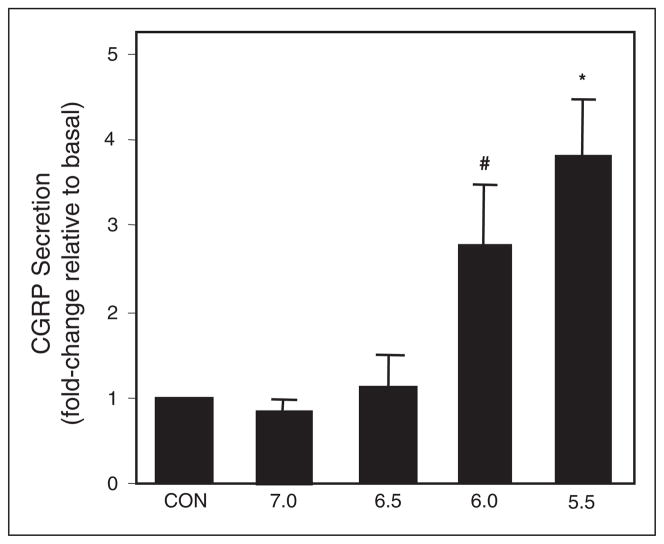

To determine whether protons could stimulate CGRP secretion, neuronal-enriched trigeminal ganglion cultures were incubated in medium at increasing acidic pH. The basal, unstimulated amount of CGRP released was measured prior to treatment and used to normalize for differences between wells. CGRP secretion was significantly increased approximately 3-fold at pH 6.0 and approximately 4-fold at pH 5.5 when compared to basal levels at pH 7.4 (Fig. 1). However, pH 7.0 and 6.5 had no significant effect on CGRP release. Thus, the threshold for activation of trigeminal neurons under our culture conditions occurs at pH 6.0.

Fig 1.

Effect of acidic medium on CGRP secretion from trigeminal ganglion neurons. The relative amount of CGRP secreted in 1 hour from untreated control cultures (CON; pH 7.4) and cultures treated with acidic HBS medium. The mean basal rate of CGRP release was 86 ± 4 pg/hour/well. The secretion rate for each condition was normalized to the basal rate for each well. The means and SE from ≥6 independent experiments are shown. #P < .05 when compared to control; *P < .01 when compared to control.

Prior to studies using primary trigeminal ganglion cultures, the effects of 100% CO2 exposure on the pH of differently buffered medium were determined. Each medium was exposed to 100% CO2 for 90, 180, or 300 seconds and the change in pH measured. As expected, CO2 exposure caused a time-dependent decrease in pH of the normal medium (HBS), dropping from a starting pH of 7.4 to pH 6.4 after 90 seconds, pH 6.2 after 180 seconds, and pH 5.8 after 300 seconds. In contrast, there was no decrease in the pH of the isohydric medium, which contained bicarbonate and phosphate, following CO2 exposure. Since increasing the exposure time did not cause any appreciable changes in pH than those seen at 300 seconds (data not shown), a CO2 treatment time of 300 seconds (5 minutes) was chosen for all subsequent experiments.

Having demonstrated that 100% CO2 exposure causes acidification of the medium, the effect of CO2 on CGRP secretion was determined. Treatment of 1-day-old trigeminal ganglion cultures for 1 hour with a depolarizing stimulus, 60 mM KCl, caused a 5-fold increase in CGRP release when compared to unstimulated control cultures (Fig. 2). For comparison, CGRP secretion was stimulated 4-fold in response to a 60-minute incubation in HBS pH 5.5 medium. After only a 5-minute exposure to 100% CO2, which decreases the medium pH to 5.8, the amount of CGRP released was increased almost 3-fold. Incubation of the cultures for 60 minutes following CO2 exposure resulted in an even greater increase in CGRP secretion (>5-fold). These results demonstrate that CO2 exposure, which causes a rapid acidification of the extracellular medium, can directly stimulate CGRP secretion.

Fig 2.

Effect of CO2 on CGRP secretion from cultured trigeminal ganglion neurons in HBS medium. The relative amounts of CGRP secreted in 1 hour from untreated control cells (CON, pH 7.4 HBS), cells treated with 60 mM KCl, pH 5.5 HBS, or 100% CO2 exposure. In addition, the amount of CGRP was determined immediately following CO2 exposure for 5 minutes. The mean basal rate of CGRP release was 98 ± 11 pg/hour/well. The means and SE from ≥6 independent experiments are shown. #P < .05 when compared to control. *P < .01 when compared to control.

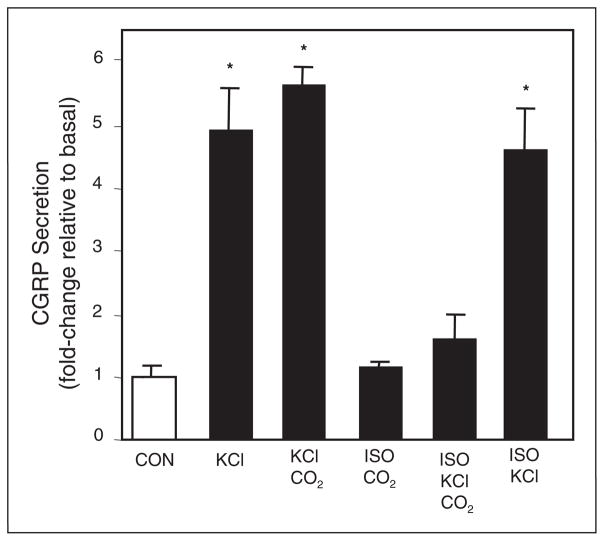

To investigate whether intracellular pH effects could be seen in the absence of extracellular pH change, we performed experiments in normal HBS medium and in isohydric medium. Initially, chemical depolarization with 60-mM KCl in HBS medium was shown to cause a 5-fold increase in CGRP secretion when compared to basal levels (Fig. 3). Pretreatment of cultures with CO2 for 5 minutes prior to addition of KCl in normal HBS medium resulted in a small increase in CGRP release. Since isohydric medium allows a change in PCO2 but not in extracellular pH, the medium allows the study of intracellular pH changes without effects on the extracellular environment.25 As expected, a 5-minute exposure to 100% CO2 in isohydric medium had no effect on medium pH, which remained at pH 7.4, and did not stimulate CGRP release. However, pretreatment of cultures in isohydric medium with CO2, greatly reduced the stimulatory effect of KCl on CGRP secretion. As a control, the effect of chemical depolarization with KCl was determined in isohydric medium. KCl caused a similar 5-fold increase in CGRP release from trigeminal neurons incubated in normal HBS medium or isohydric medium. To determine if the inhibitory effect of CO2 on CGRP secretion results were due to cellular toxicity, trypan blue exclusion was performed on cultures 24 hours post-treatment with no media change. No statistical difference in cell viability was observed under stimulatory, isohydric, basal, or hypercapnic conditions (data not shown). Taken together, these data demonstrate that under isohydric conditions CO2 exposure can repress stimulated CGRP release from trigeminal neurons in response to chemical depolarization.

Fig 3.

Effect of CO2 on CGRP secretion from cultured trigeminal ganglion neurons in isohydric medium. The relative amounts of CGRP secreted in 1 hour from untreated control cells (CON, HBS pH 7.4); cells treated with 60 mM KCl or exposed to 100% CO2 for 5 minutes prior to KCl. Additionally, the relative amount of CGRP secreted under isohydric conditions (ISO) was determined. The mean basal rate of CGRP release was 94 ± 7 pg/hour/well. The means and SE from ≥6 independent experiments are shown. *P < .01 when compared to control.

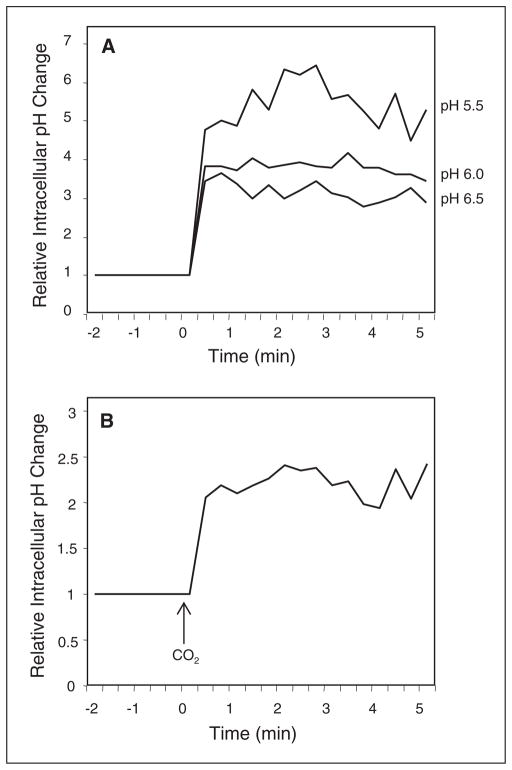

To assess whether CO2 exposure of trigeminal neurons in isohydric medium could cause a decrease in intracellular pH, cultures were loaded with the fluorescent intracellular pH indicator SNARF-4AM and intracellular pH levels measured. Initially, the relative change in intracellular pH in cultures incubated in isohydric medium at pH 6.5, 6.0, and 5.5 and containing the ionophore nigericin (10 μM) was measured. Basal levels were collected at 20 second intervals for 120 seconds in isohydric media pH 7.4 prior to incubation for 5 minutes in decreasing pH media to determine the average intracellular pH for each well. Under these conditions, isohydric medium at pH 6.5 and containing nigericin resulted in a relative intracellular pH change of 2 units above basal levels, which were made equal to 1 (Fig. 4A). Incubation of cultures in pH 6.0 medium caused an intracellular pH increase of 2.5 while incubation in pH 5.5 medium resulted in an even larger increase above basal levels (~4.5) (Fig. 4A). Having established a correlation of medium pH to relative changes in intracellular pH cultures were exposed to 100% CO2 for 5 minutes in isohydric medium and the relative change in intracellular pH measured. CO2 exposure to the cultures caused a shift in the relative intracellular pH when compared to basal levels (Fig. 4B). These data demonstrate that CO2 exposure can cause a decrease in intracellular pH in trigeminal neurons.

Fig 4.

CO2 causes a reduction in intracellular pH. Relative intracellular pH levels in cultured trigeminal ganglion neurons incubated in isohydric medium at pH 5.5, 6.0, 6.5 that contained the ionophore, nigericin (A), or in response to 5 minutes CO2 exposure (B). Levels are the average of all the cells in each well. A representative graph from ≥6 independent experiments is shown. All data are expressed relative to basal levels, which were made equal to 1.

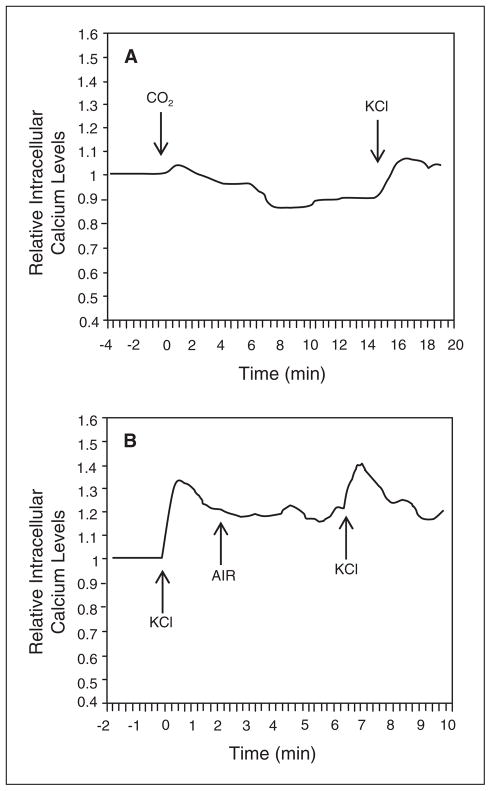

Repression of KCl stimulation under isohydric hypercapnic conditions as seen in Figure 3, suggested that CO2 might be affecting calcium ion channel activity. Calcium imaging was used to investigate the effects of 100% CO2 on intracellular calcium levels. Basal calcium levels were collected at 20 second intervals for 120 seconds prior to experimental conditions on the same wells to determine average calcium levels for each well. Exposure of cultures to CO2 prior to treatment with KCl blocked the expected increase in intracellular calcium (Fig. 5A). As a control, cultures treated with compressed air instead of CO2 for 5 minutes exhibited the typical rapid elevation of intracellular calcium in response to KCl (Fig. 5B). Based on these results, CO2 repression of KCl-stimulated CGRP release from trigeminal neurons likely involves blockage of calcium ion channels.

Fig 5.

CO2 inhibition of KCl-mediated elevation of intra-cellular calcium levels. Relative intracellular calcium levels in cultured trigeminal ganglion neurons incubated in isohydric medium in response to CO2 exposure and stimulated with 60 mM KCl (A), or stimulated with KCl before and after exposure to compressed air (B). The levels are the average of all the cells in each well. A representative graph from ≥6 independent experiments is shown. All data are expressed relative to basal calcium levels, which were made equal to 1.

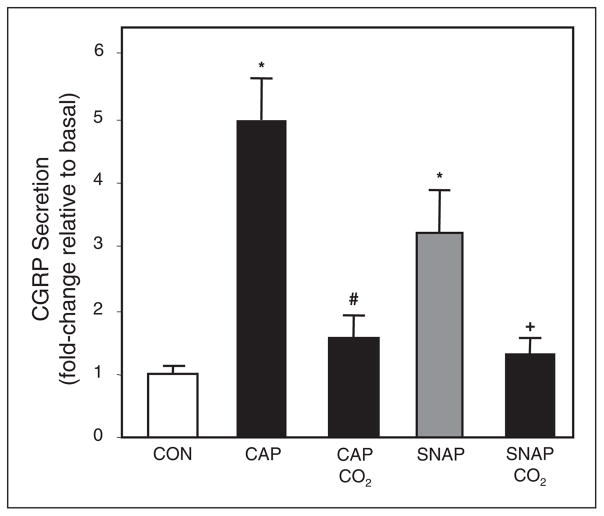

To establish whether CO2 could inhibit stimulated CGRP secretion by known inflammatory agents, trigeminal cultures were treated with capsaicin or the NO donor SNAP. In isohydric medium, capsaicin (2 μM) stimulated CGRP levels almost 5-fold above basal levels and SNAP (1 mM) increased CGRP secretion about 3-fold (Fig. 6). However, in cultures exposed to 100% CO2 for 5 minutes, the stimulatory effects of capsaicin and SNAP were significantly repressed to near basal levels (Fig. 6). As a control, vehicle alone (DMSO) did not cause increased CGRP secretion (data not shown). Thus, CO2 can inhibit CGRP release from trigeminal neurons in response to 3 different stimuli, KCl, capsaicin, and NO.

Fig 6.

Effect of CO2 on capsaicin and NO stimulation of CGRP release. The relative amounts of CGRP secreted in 1 hour from trigeminal neurons incubated in isohydric medium from untreated control cells (CON), or cells treated with 2 μM capsaicin (CAP) or the NO donor (SNAP, 1 mM) under basal conditions or following CO2 exposure. The mean basal rate of CGRP release was 104 ± 7 pg/hour/well. The means and SE from ≥6 independent experiments are shown. *P < .01 when compared to control. #P < .01 when compared to capsaicin-treated culture. +P < .05 when compared to SNAP-treated culture.

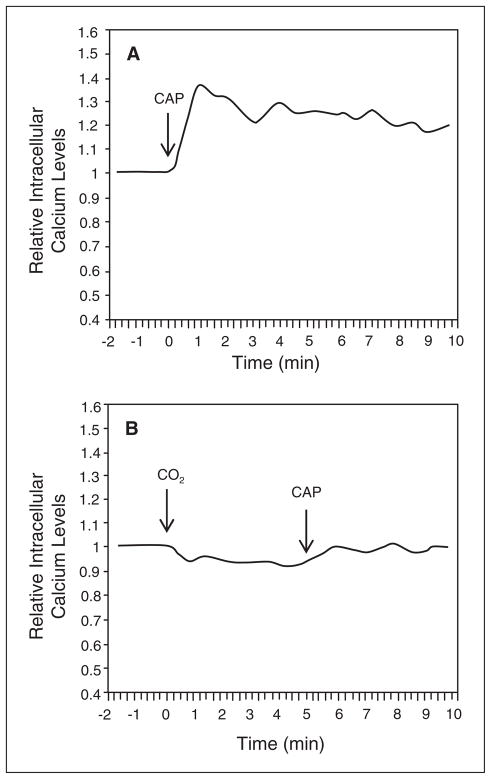

Calcium imaging was used to investigate whether the inhibitory effect of CO2 on capsaicin-stimulated CGRP secretion was due to inhibition of the reported rise in intracellular calcium in response to capsaicin.33 Basal calcium levels were measured in isohydric medium prior to stimulation with 2 μM capsaicin. Capsaicin treatment alone caused a rapid increase in intracellular calcium above basal levels (Fig. 7A) that was similar to that seen with KCl (Fig. 5B). In contrast, intracellular calcium levels did not change from basal levels when cultures were exposed to CO2 prior to addition of capsaicin (Fig. 7B). Based on these data, CO2 repression of capsaicin-stimulated CGRP release from trigeminal neurons is likely mediated via inhibition of calcium channel activity and the subsequent elevation of intracellular calcium.

Fig 7.

CO2 inhibition of capsaicin-mediated elevation of intracellular calcium levels. Relative intracellular calcium levels in cultured trigeminal ganglion neurons incubated in isohydric in response to 2 μM capsaicin (A) or following exposure to CO2 (B). The levels are the average of all the cells in each well. A representative graph from ≥6 independent experiments is shown. All data are expressed relative to basal calcium levels, which were made equal to 1.

COMMENTS

Recent phase II clinical studies suggest that non-inhaled intranasal 100% CO2 is beneficial in treating migraine headache and allergic rhinitis.22,23 The goal of this study was to determine the effects of CO2 exposure on trigeminal neurons and particularly, on CGRP secretion. We utilized a novel system originally reported by Farley and Adler34 to study extracellular versus intracellular pH changes caused by CO2 exposure and their effects on CGRP secretion, by allowing PCO2 to change while controlling extracellular pH, a condition termed isohydric hypercapnia.25–27 Using this system, we demonstrated that CO2 exposure under isohydric conditions prevented increases in CGRP secretion caused by chemical depolarization, capsaicin, or NO. Furthermore, our data suggest that the inhibitory effect of CO2 on stimulated CGRP secretion involves a decrease in intracellular pH and modulation of calcium channel activity, which may help to explain the potential benefit of CO2 in conditions involving trigeminal nerve activation as reported in migraine and allergic rhinitis. Interestingly, inhalation of 100% oxygen and sumatriptan, which are standard therapies for cluster headache, have been reported to reduce the level of CGRP in blood from the external jugular vein to near normal levels.35 The therapeutic benefit of inhaling 100% oxygen is thought to involve vasoconstriction of cerebral blood vessels and inhibition of the trigeminovascular system. In a more recent animal study, hyperoxia was shown to inhibit dural protein plasma extravasation caused by electrical stimulation of the rat trigeminal ganglion.36 In both studies, 100% oxygen was inhaled and, therefore, high arterial oxygen levels were achieved. In contrast, CO2 treatment involves noninhaled intranasal delivery and thus, would not be expected to cause a significant change in arterial CO2 levels. However, despite the differences in delivery methods, both CO2 and oxygen treatment have now been shown to inhibit trigeminal nerve activity. It will be of interest to determine whether CO2 treatment can inhibit protein plasma extravasation following trigeminal nerve stimulation and whether exposure to 100% CO2 would be effective in treating cluster headache.

This study demonstrates that CO2 can effectively block KCl as well as capsaicin stimulation of trigeminal neurons and subsequent CGRP release. This inhibitory effect likely involves inhibition of calcium channels, since CO2 treatment was shown to block the typical physiological increase in intracellular calcium. The cellular effects of KCl and capsaicin have previously been shown to be mediated by activation of calcium channels.37–40 Interestingly, high voltage-activated calcium channels, particularly the L- and N-type, are highly sensitive to protons and may be the specific targets for internal pH shifts, whereas low-threshold calcium currents are insensitive to both acidic and alkaline shifts.41 In our study, we found that CO2 treatment produced a reduction in intracellular pH when extracellular pH was held constant at 7.4 with an isohydric medium. It is well documented that lowered intracellular pH exerts inhibitory effects on voltage gated channels in neuronal cells.42–46 Importantly, intracellular acidosis has been demonstrated to specifically inhibit calcium channels in hippocampal neurons41 and Purkinje cells.47 Thus, modulation of channel activity by changes associated with intracellular acidosis may be a normal regulatory mechanism of neuronal activity. Based on these findings, it is likely that the decrease in intracellular pH observed in our study in response to CO2 under isohydric conditions was involved in blocking calcium channels and hence, stimulated CGRP secretion.

In addition to repressing CGRP secretion in response to chemical depolarization and capsaicin, CO2 treatment effectively repressed CGRP release from trigeminal neurons stimulated by NO. The stimulatory effect of NO is in agreement with results from a recently published study that showed NO treatment increased both the synthesis and release of CGRP from cultured trigeminal neurons.21 Our finding that CO2 can inhibit NO stimulation of CGRP secretion may have important therapeutic implications since increased NO production is thought to play an important role in diseases involving trigeminal nerve activation as reported in migraine headache,48,49 allergic rhinitis,50 and TMJ inflammation.51 While CO2 repression of KCl and capsaicin stimulation likely involves blockage of high voltage-activated calcium channels, its inhibitory effect on NO is likely to occur by a different mechanism. Recent studies have provided evidence that the effects of NO on trigeminal neurons are mediated via activation of T-type calcium channels.21,52 These ion channels, also known as low voltage-activated channels,53 have been reported to be expressed by nociceptive neurons.54 Furthermore, the activity of T-type channels has not been reported to be decreased by protons as are the high voltage-activated calcium channels. Thus, it appears that CO2 inhibits neuronal activation by multiple mechanisms involving modulation of the activity of different and distinct calcium channels.

Our data demonstrate that CO2 repression of stimulated CGRP release from trigeminal neurons correlates with inhibition of elevated intracellular calcium levels in response to KCl and capsaicin. Interestingly, previous studies have shown that repression of stimulated CGRP secretion by currently used antimigraine drugs such as sumatriptan and zolmatriptan also involves modulation of intracellular calcium levels.28,29,55 However, the cellular events involved in repressing CGRP release may be achieved via distinctly different mechanisms. While treatment with CO2 prevents KCl- and capsaicin-mediated increases in calcium without significantly altering basal calcium levels, treatment with sumatriptan caused a sustained elevation of intracellular calcium.28,29 The mechanism was shown to involve activation of 5-HT1 receptors and induction of specific phosphatases, changing the phosphorylation state of the cell. It is reported that hyperphosphorylation is associated with increased neuropeptide release, while hypophosphorylation is associated with decreased release.56 Although not investigated in this study, it is probable that the inhibitory effect of CO2 will involve recruitment of cytosolic phosphatases, in addition to decreasing intracellular pH and inhibiting calcium channel activity. In support of this notion, others have reported increased phosphatase activity at acidic intracellular pH.56,57

A goal of this study was to understand at the cellular level the physiological effects of CO2 administration reported by patients. These effects include relief of migraine headache and allergic rhinitis and an initial transient burning, stinging sensation within the nose. We speculated that the initial unpleasant events experienced by some individuals during CO2 treatment were caused by a reduction in extracellular pH within the nasal mucosa and subsequent proton activation of trigeminal nociceptive neurons. Toward this end, we found that at an extracellular pH < 6.0 trigeminal neurons increased CGRP release to a level several-fold higher than basal levels at pH 7.4. Similarly, CO2 exposure of cultures resulted in an acidic shift in pH that caused a significant increase in the amount of CGRP secreted. Our findings are in agreement with previous studies that reported increased neuronal activity and CGRP secretion in response to protons.58,59 The ability of protons to cause local tissue inflammation and pain has been shown to involve decreasing extracellular pH by as much as 2 pH units.60 Importantly, current theories on migraine pathology suggest an important role of protons in the generation of headache pain.13,61

The effects of protons have been reported to involve activation of TRPV162,63 or acid sensitive ion channels (ASIC) that leads to depolarization of neurons.64,65 TRPV1 receptors are predominantly expressed on nociceptive neurons such as C-fiber neurons66 and are coexpressed on CGRP immunoreactive neurons.18,67 Activation of TRPV1 is implicated in various painful conditions.68,69 Similarly, at least 2 members of the ASIC family, ASIC2a and ASIC3, are present in the trigeminal system and are expressed in CGRP containing trigeminal neurons.70–72 Once activated, these channels cause an increase in intracellular calcium and thus initiate neuropeptide secretion in response pathological extracellular acidification.73 Gu and Lee74 suggest that the proton induced transient currents observed in sensory neurons that are blocked by the nonselective ASIC inhibitor, amiloride, provides evidence that these currents are mediated by ASIC activation. In contrast, TRPV1 is likely involved in the sustained current generated in response to protons, since these currents were attenuated by pretreatment with the selective TRPV1 antagonist, capsazepine. Further studies are necessary to determine the exact mechanism by which protons stimulate CGRP secretion from trigeminal neurons.

In summary, we have shown that CO2 exposure of trigeminal neurons causes a decrease in extracellular pH that stimulates CGRP release. We speculate that the stimulatory effect of protons is mediated via activation of TRPV1 or ASICs. Interestingly, we found that CO2 treatment under isohydric conditions significantly repressed the stimulatory effects of KCl, capsaicin, and NO. This is the first evidence to our knowledge of CO2 repression of stimulated neuropeptide release from sensory neurons. Based on our results, we propose that the inhibitory effects of CO2 involve inhibition of calcium ion channels via a decrease in intracellular pH. An important question to be answered is how can noninhaled intranasal delivery of 100% CO2 abort migraine and allergic rhinitis attacks. In this study, we demonstrated that exposure of trigeminal neurons to 100% CO2 can block neuronal activation and the subsequent release of CGRP, physiological events implicated in migraine and allergic rhinitis pathology. We propose that intranasal delivery of CO2 can directly repress activity of trigeminal nerves that provide sensory innervation of the nasal mucosa and, thus, provide relief of rhinitis symptoms. With respect to migraine, activation of V1 trigeminal nerves is known to be involved in migraine pathology. Interestingly, both the frontal and sphenoid sinuses are innervated by sensory neurons from the V1 region of the trigeminal ganglion,75 whose activity would likely be repressed by CO2 treatment. We can only speculate that CO2 inhibition of V1 neurons in one region of the ganglion may lead to inhibition of other neurons within that region. In this way, inhibition of nerves that provide sensory innervation of the sinuses may mediate cellular events that decrease the activity of nerves that provide sensory innervation of the dura and are involved in migraine. In support of this notion, intra-ganglion communication or regulation has been reported to occur within other sensory ganglia, such as the dorsal root ganglion and nodose ganglion, and is thought to allow for a coordinated response to different stimulatory or inhibitory agents.76–78 In conclusion, our findings support a mechanism by which intranasal CO2 administration inhibits trigeminal neuron activity and, thus, may prove useful not only for the treatment of migraine and allergic rhinitis, but also in the treatment of other diseases involving trigeminal nerves.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ms. C. Niemann for her technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- CGRP

calcitonin gene-related peptide

- CO2

carbon dioxide

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- HBS

HEPES buffered saline

- KCl

potassium chloride

- NO

nitric oxide

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- SNAP

S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine

- ASIC

acid sensing ion channels

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: This work was supported by a grant from Capnia Inc. to P.L.D. Capnia has provided financial support for research conducted in Dr. Durham’s laboratory. Dr. Spierings is a member of the advisory board and a consultant for Capnia.

References

- 1.Stewart W, Schechter A, Rasmussen B. Migraine heterogeneity: Disability, pain, intensity, and attack frequency and duration. Neurology. 1994;44:S24–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrari MD. The economic burden of migraine to society. Pharmacoeconomics. 1998;13:667–676. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199813060-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burstein R, Yarnitsky D, Goor-Aryeh I, Ransil B, Bajwa Z. An association between migraine and cutaneous allodynia. Ann Neurol. 2000;47:614–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strassman A, Levy D. Response properties of dural nociceptors in relation to headache. J Neurophysiol. 2006;95:1298–1306. doi: 10.1152/jn.01293.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lanza D, Kennedy D. Adult rhinosinusitis defined. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;117:S1–7. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59989770001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Becker D. Sinusitis. J Long Term Eff Med Implants. 2003;13:175–194. doi: 10.1615/jlongtermeffmedimplants.v13.i3.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnes P, Baraniuk J, Belvisi M. Neuropeptides in the respiratory tract. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144:1187–1198. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/144.5.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stead R, Bienenstock J, Stanisz A. Neuropeptide regulation of mucosal immunity. Immunol Rev. 1987;100:333–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1987.tb00538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tai C, Baraniuk J. Upper airway neurogenic mechanisms. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immun. 2002;2:11–19. doi: 10.1097/00130832-200202000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Rossum D, Hanisch U, Quirion R. Neuroanatomical localization, pharmacological characterization and functions of CGRP, related peptides and their receptors. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1997;21:649–678. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(96)00023-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edvinsson L. Aspects on the pathophysiology of migraine and cluster headache. Pharm Tox. 2001;89:65–73. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0773.2001.d01-137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edvinsson L, Elsas T, Suzuki N, Shimizu T, Lee T. Origin and co-localization of nitric oxide synthase, CGRP, PACAP, and VIP in the cerebral circulation of the rat. Microsc Res Tech. 2001;53:221–228. doi: 10.1002/jemt.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pietrobon D, Striessnig J. Neurobiology of migraine. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:386–398. doi: 10.1038/nrn1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mosimann B, White M, Hohman R, Goldrich M, Kaulbach H, Kaliner M. Substance P, calcitonin gene-related peptide, and vasoactive intestinal peptide increased in nasal secretions after allergen challenge in atopic patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1993;92:95–104. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(93)90043-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bellamy J, Cady R, Durham P. Salivary levels of CGRP and VIP in rhinosinusitis and migraine patients. Headache. 2006;46:24–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCulloch J, Uddman R, Kingman T, Edvinsson L. Calcitonin gene-related peptide: Functional role in cerebrovascular regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:5731–5735. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.15.5731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Preibisz J. Calcitonin gene-related peptide and regulation of human cardiovascular homeostasis. Am J Hypertens. 1993;6:434–450. doi: 10.1093/ajh/6.5.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murata Y, Masuko S. Peripheral and central distribution of TRPV1, substance P, and CGRP of rat corneal neurons. Brain Res. 2006;1085:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenfeld M, Mermod J-J, Amara S, et al. Production of a novel neuropeptide encoded by the calcitonin gene via tissue-specific RNA processing. Nature. 1983;304:129–135. doi: 10.1038/304129a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Theoharides T, Donelan J, Kandere-Grzybowska K, Konstantinidou A. The role of mast cells in migraine pathophysiology. Brain Res. 2005;49:65–76. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bellamy J, Bowen E, Russo A, Durham P. Nitric oxide regulation of calcitonin gene-related peptide gene expression in rat trigeminal ganglia neurons. Eur J Neuroscience. 2006;23:2057–2066. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04742.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Casale T, Romero F, Mahon L, Bewtra A, Stokes J, Hopp R. Intranasal non-inhaled CO2 provides rapid relief of seasonal allergic rhinitis (SAR) nasal symptoms. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:S261. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spierings G. Abortive treatment of migraine headache with non-inhaled, intranasal carbon dioxide: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study. Headache. 2005;45:809. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geers C, Gros G. Carbon dioxide transport and carbonic anhydrase in blood and muscle. Physiol Rev. 2000;80:681–715. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.2.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Summers B, Overholt J, Prabhakar N. CO2 and pH independently modulate L-type Ca2+ current in rabbit carotid body glomus cells. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88:604–612. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.88.2.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Munoz-Cabello A, Toledo-Aral J, Lopez-Barneo J, Echevarria M. Rat adrenal chromaffin cells are neonatal CO2 senors. J Neurosci. 2005;25:6631–6640. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1139-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Otsuguro K, Yamaji Y, Ban M, Ohta T, Ito S. Involvement of adenosine in depression of synaptic transmission during hypercapnia in isolated spinal cord of neonatal rats. J Physiol. 2006;574:835–847. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.109660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Durham P, Russo A. Regulation of calcitonin gene-related peptide secretion by a serotonergic antimigraine drug. J Neurosci. 1999;19:3423–3429. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-09-03423.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Durham P, Russo A. Stimulation of the calcitonin gene-related peptide enhancer by mitogen-activated protein kinases and repression by an antimigraine drug in trigeminal ganglia neurons. J Neurosci. 2003;23:807–815. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-03-00807.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bowen E, Schmidt T, Firm C, Russo A, Durham P. Tumor necrosis factor-a stimulation of calcitonin gene-related peptide expression and secretion from rat trigeminal ganglion neurons. J Neurochem. 2006;96:65–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03524.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qian T, Nieminen A, Herman B, Lemasters J. Mitochondrial permeability transition in pH-dependent reperfusion injury to rat hepatocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1997;273:C1783–C1792. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.6.C1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Durham P, Russo A. Differential regulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase-responsive genes by the duration of a calcium signal. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14:1570–1582. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.10.0529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garcia-Hirschfeld J, Lopez-Briones L, Belmonte C, Valdeolmillos M. Intracellular free calcium responses to protons and capsaicin in cultured trigeminal neurons. Neuroscience. 1995;67:235–243. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00055-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farley D, Adler S. Isohydric regulation of plasma potassium by bicarbonate in the rat. Kidney Int. 1976;9:333–343. doi: 10.1038/ki.1976.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goadsby P, Edvinsson L. Human in vivo evidence for trigeminovascular activation in cluster headache. Neuropeptide changes and effects of acute attacks therapies. Brain. 1994;117:427–434. doi: 10.1093/brain/117.3.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schuh-Hofer S, Siekmann W, Offenhauser N, Reuter U, Arnold G. Effect of hyperoxia on neurogenic plasma protein extravasation in the rat dura mater. Headache. 2006;46:1545–1551. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bell J. Selective blockade of spinal reflexes by omega-conotoxin in the isolated spinal cord of the neonatal rat. Neuroscience. 1993;52:711–716. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90419-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kopanitsa M, Panchenko V, Magura E, Lishko P, Krishtal O. Capsaicin blocks Ca2+ channels in isolated rat trigeminal and hippocampal neurons. Neuroreport. 1995;6:2338–2340. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199511270-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brosenitsch T, Salgado-Commissariat D, Kunze D, Katz D. A role for L-type calcium channels in developmental regulation of transmitter phenotype in primary sensory neurons. J Neurosci. 1998;18:1047–1055. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-03-01047.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mohri Y, Katsura M, Shuto K, Tsujimura A, Ishii R, Ohkuma S. L-type high voltage gated calcium channels cause an increase in diazepam binding inhibitor mRNA expression after sustained exposure to ethanol in mouse cerebral cortical neurons. Brain Res. 2003;113:52–56. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(03)00089-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tombaugh G, Somjen G. Differential sensitivity to intracellular pH among high- and low-threshold Ca2+ currents in isolated rat CA1 neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1997;77:639–953. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.2.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tombaugh G. Intracellular pH buffering shapes activity-dependent Ca2+ dynamics in dendrites of CA1 interneurons. J Neurophysiol. 1998;80:1702–1712. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.4.1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Traynelis S. pH modulation of ligand gated ion channels. In: Kaila K, Ransom B, editors. pH and Brain Function. New York: Wiley-Liss; 1998. pp. 416–417. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kiss L, Korn S. Modulation of N-type Ca2+ channels by intracellular pH in chick sensory neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1999;81:1939–1947. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.4.1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bonnet U, Leniger T, Wiemann M. Alteration of intracellular pH and activity of CA3-pyramidal cells in guinea pig hippocampal slices by inhibition of transmembrane acid extrusion. Brain Res. 2000;872:116–124. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02350-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bonnet U, Leniger T, Weimann M. Moclobemide reduces intracellular pH and neuronal activity of CA3 neurons in guinea-pig hippocampal slices-implication for its neuroprotective properties. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39:2067–2074. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(00)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Willoughby D, Schwiening C. Electrically evoked dendrite pH transients in rat cerebellar Purkinje cells. J Physiol. 2002;544:487–499. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.027508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Olesen J, Jansen-Olesen I. Nitric oxide mechanisms in migraine. Pathol Biol (Paris) 2000;48:648–657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Olesen J, Iversen H, Thomsen L. Nitric oxide super-sensitivity: A possible molecular mechanism of migraine pain. Neuroreport. 1993;4:1027–1030. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199308000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Takeno S, Osada R, Furukido K, Chen J, Yajin K. Increased nitric oxide production in nasal epithelial cells from allergic patients—RT-PCR analysis and direct imaging by a flourescence indicator: DAF-2 DA. Clin Exp Allergy. 2001;31:881–888. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2001.01093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yamaza T, Masuda K, Tsukiyama Y, et al. NF-kappaB activation and iNOS expression in the synovial membrane of rat temporomandibular joints after induced synovitis. J Dent Res. 2003;82:183–188. doi: 10.1177/154405910308200307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zeng X, Keyser B, Li M, Sikka S. T-type (alpha 1G) low voltage-activated calcium channel interaction with nitric oxide-cyclic granosine monophosphate pathway and regulation of calcium homeostasis in human carvernosal cells. J Sex Med. 2005;2:620–630. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2005.00115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Perez-Reyes E. Molecular characterization of T-type calcium channels. Cell Calcium. 2006;40:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2006.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Todorovic S, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Meyenburg A, et al. Redox modulation of T-type calcium channels in rat peripheral nociceptors. Neuron. 2001;31:75–85. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00338-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Morikawa T, Matsuzawa Y, Makita K, Katayama Y. Antimigraine drug, zolmitriptan, inhibits high-voltage activated calcium currents in a population of acutely dissociated rat trigeminal sensory neurons. Molecular Pain. 2006;2:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-2-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yenush L, Merchan S, Holmes J, Serrano R. pH-responsive, posttranslational regulation of the Trk1 postassium transporter by the type 1-related Ppz1 phosphatase. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:8683–8692. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.19.8683-8692.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hingtgen C, Vasko M. The phosphatase inhibitor, okadaic acid, increases peptide release from rat sensory neurons in culture. Neurosci Lett. 1994;178:135–138. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90308-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Geppetti P, Del Bianco E, Patacchini R, Santicoli P, Maggi C, Tramontana M. Low pH-induced release of calcitonin gene-related peptide from capsaicin-sensitive sensory nerves; mechanism of action and biological response. Neurosci. 1991;41:295–301. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90218-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Del Bianco E, Santicioli P, Tramontana M, Maggi C, Cecconi R, Geppetti P. Different pathways by which extracellular Ca2+ promotes calcitonin gene-related peptide release from central terminals of capsaicin-sensitive afferents of guinea pigs: Effect of capsaicin, high K+ and low pH media. Brain Res. 1991;566:46–53. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91679-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Reeh P, Steen K. Tissue acidosis in nociception and pain. Prog Brain Res. 1996;113:143–151. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)61085-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bolay H, Moskowitz M. The emerging importance of cortical spreading depression in migraine headache. Rev Neurol (Paris) 2005;161:655–657. doi: 10.1016/s0035-3787(05)85108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Caterina M, Leffler A, Malmberg A, et al. Impaired nociception and pain sensation in mice lacking the capsaicin receptor. Science. 2000;288:306–313. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5464.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Julius D, Basbaum A. Molecular mechanisms of nociception. Nature. 2001;413:203–210. doi: 10.1038/35093019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Waldmann R. Proton-gated cation channels—neuronal acid sensors in the central and peripheral nervous system. In: Rea Roach., editor. Hypoxia: From Genes to the Bedside. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2001. pp. 293–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xiong Z, Saggau P, Stringer J. Activity-dependent intracellular acidification correlates with the duration of seizure activity. J Neurosci. 2000;20:1290–1296. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-04-01290.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Caterina M, Schumacher M, Tominaga M, Rosen T, Julius D. The capsaicin receptor: A heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature. 1997:816–824. doi: 10.1038/39807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Price T, Patwardhan A, Akopian A, Hargreaves K, Flores C. Modulation of trigeminal sensory neuron activity by the dual cannabinoid-vanilloid agonists anandamide, N-arachidonoyl-dopamine and arachidonyl-2-chloroethylamide. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;141:1118–1130. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gazerani P, Andersen O, Arendt-Nielsen L. A human experimental capsaicin model for trigeminal sensitization. Gender-specific differences. Pain. 2005;118:155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nishikawa T, Takeda M, Tanimoto T, Matsumoto S. Convergence of nociceptive information from temporomandibular joint and tooth pulp afferents on C1 spinal neurons in the rat. Life Sci. 2004;75:1465–1478. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Olson T, Riedl M, Vulchanova L, Ortiz-Gonzalez X, Elde R. An acid sensing ion channel (ASIC) localizes to small primary afferent neurons in rats. Neuroreport. 1998;9:1109–1113. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199804200-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Babinski K, Le K, Seguela P. Molecular cloning and regional distribution of a human proton receptor subunit with biphasic functional properties. J Neurochem. 1999;72:51–57. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0720051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ichikawa H, Sugimoto T. The co-expression of ASIC3 with calcitonin gene-related peptide and parvalbumin in the rat trigeminal ganglion. Brain Res. 2002;943:287–291. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02831-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Xiong Z, Chu X, Simon R. Ca2+-permeable acid-sensing Ion channels and ischemic brain injury. J Membr Biol. 2006;209:59–68. doi: 10.1007/s00232-005-0840-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gu Q, Lee L. Characterization of acid signaling in rat vagal pulmonary sensory neurons. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;291:L58–L65. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00517.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shankland W. The trigeminal nerve. Part III: The ophthalmic divison. J Craniomandib Pract. 2001;19:8–12. doi: 10.1080/08869634.2001.11746145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Amir R, Devor M. Chemically mediated cross-excitation in rat dorsal root ganglia. J Neurosci. 1996;16:4733–4741. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-15-04733.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Oh EJ, Weinreich D. Chemical communication between vagal afferent somata in nodose Ganglia of the rat and the Guinea pig in vitro. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87:2801–2807. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.87.6.2801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ulrich-Lai YM, Flores CM, Harding-Rose CA, Goodis HE, Hargreaves KM. Capsaicin-evoked release of immunoreactive calcitonin gene-related peptide from rat trigeminal ganglion: Evidence for intra-ganglionic neurotransmission. Pain. 2001;91:219–226. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00439-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]