Abstract

Objective. To assess cognitive development and learning in children who have had strokes. Method. Twenty-nine stroke patients and 18 children with no brain lesions and no learning impairments were evaluated. For the cognitive assessment, Piaget's clinical method was used. Writing, arithmetic, and reading abilities were assessed by the school performance test. Results. The mean age at evaluation was 9.6 years. Among the 29 children, 20 had early lesions (mean of 2.4 years old). The stroke was ischemic in 18 subjects; there were 7 cases of recurrence. Six children could not answer the tests. A high index of cognitive delay and low performance in writing, arithmetic, and reading were verified. Comparison with the control group revealed that the children who have had strokes had significantly lower performances. Conclusion. In this sample, strokes impaired cognitive development and learning. It is important that children have access to educational support and cognitive rehabilitation after injury. These approaches may minimise the effects of strokes on learning in children.

1. Introduction

A childhood stroke is defined as a cerebrovascular event that occurs between 29 days and 18 years of age [1]. Its incidence varies from 2.3 to 13/100,000 children/year [2–9]. Although it is considered rare, the childhood stroke is among the ten main causes of death. Around 5% to 10% of the patients die, mostly in the first year of life [1, 10]. In general, children who survive strokes will live with sequelae for the rest of their lives, and these conditions may cause impairments in other aspects of their personal and familiar lives.

Over the last decade, research investigating the cognitive evolution of children [11–20] has shown that the learning also deserves special attention. In regard to school-based learning, there is evidence that these children need specialised educational assistance (at regular schools or other special education institutions) and are more likely to have school failures [13, 14, 21–24]. However, data are scarce, which justifies the development of new studies in this area. The main objective of this study was to investigate cognitive development and the writing, arithmetic, and reading abilities in children who have had strokes.

2. Method

The present study was submitted to and approved by the Ethics Research Committee of the State University of Campinas Medical Sciences Faculty (Process no. 638/2003). Parents were informed about the research content and gave signed consent.

2.1. Participants

Children ranging in age from zero to fifteen years old are followed at the Childhood and Adolescence Cerebrovascular Disease Research Outpatient Unit of the Clinics Hospital (HC), State University of Campinas (Unicamp). Patients of 15 years old or younger who had been treated for ischemic or hemorrhagic strokes were included in this study. Diagnosis was made through clinical, laboratory, and neuroimaging examinations. Patients who have had strokes caused by hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, head trauma and Down syndrome were excluded. The group of children who had strokes was labelled the experimental group (EG).

A control group (CG) was composed of subjects similar in age and gender to the EG. The children of this group attended public schools in the Campinas, São Paulo (Brazil) region, had no history of cerebral lesion and had no learning problems according to their teachers.

The evaluation of all children was done individually in an appropriate room, free from outside interferences. The EG was assessed at HC/Unicamp and the CG at the school they attended.

2.2. Cognition Functioning

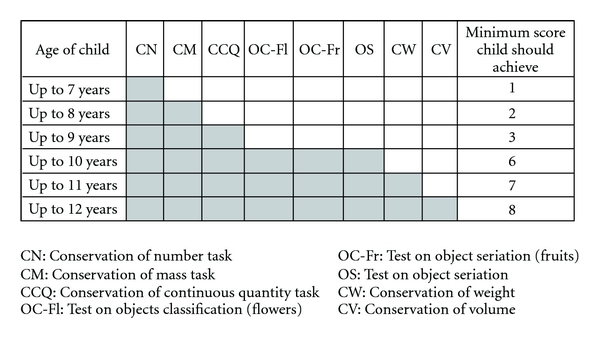

The cognitive development was evaluated through Piaget's clinical method [25]. Five conservation tasks (number, mass, continuous quantity, weight, and volume), two tests on object classification, and one test on object seriation were used. The following criteria were used for grading the tests: 1 point for correct responses, 0.5 points for partial correct responses, and 0 points for incorrect responses. Figure 1 describes the scores expected in relation to age.

Figure 1.

Grading criteria for Piaget's operation tasks.

The total score obtained by the child was compared to the total score expected for chronological age. The final classification of cognitive development complied with the following criteria: an adequate level if the score was equal to or higher than the expected score for the child's age; mild delay if the score was up to two points below the expected score; severe delay if the score was between 7 and 8 points below the expected score.

To evaluate writing, arithmetic, and reading performances, the school performance test [26], which is a developed and standardised tool for the Brazilian population, was used.

The data were analysed and compared. Statistical analysis was conducted through the SAS System for Windows (version 8.02) and SPSS for Windows (version 10.0.5) programmes. The significance level adopted was P < .05.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

There were 13 girls and 16 boys. Eighteen patients had ischemic strokes, and 11 had haemorrhagic strokes. The mean age at stroke onset was 2.4 years old (range of 1 month to 10 years old) with a median age of 1.66 years old. Twenty patients had early strokes (occurred in the time from birth up to the second year of life), and there were 7 cases of recurrence. Most of the lesions were seen in the right hemisphere, and 13 patients had cortical and subcortical lesions. The mean age of the patients at assessment was 9.6 years old (range of 7 to 12 years old), with a median age of 10 years and 1 month old (Table 1). The mean follow-up time of the EG was 7.6 years (range of 4 months to 12 years), with a median of 7 years.

Table 1.

Experimental group characteristics.

| Subject | Gender | Stroke Type | Stroke onset (y + m) | Age at assessment (y + m) | Affected hemisphere | Lesion area |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | I | 7 + 2 | 7 + 10 | B | L: C R: S |

| 2 | F | I | 2 + 11 | 8 + 4 | L | S |

| 3 | M | H | 0 + 1 | 8 + 1 | R | S |

| 4 | M | H | 11 + 8 | 12 + 0 | L | C/S |

| 5 | M | H | 1 + 0 | 7 + 1 | B | L: C R: CB |

| 6 | M | I | 2 + 6 | 8 + 10 | B | L: C/S R: S |

| 7 | F | I | 2 + 4 | 10 + 2 | R | C/S |

| 8* | F | I | 0 + 5 | 9 + 5 | B | L: C R: C |

| 9 | M | I | 4 + 10 | 10 + 9 | L | C/S |

| 10* | F | I | 1 + 2 | 9 + 7 | B | L: S R: S |

| 11 | M | I | 1 + 8 | 12 + 0 | L | S |

| 12 | M | H | 10 + 2 | 12 + 7 | L | BS |

| 13 | M | H | 0 + 2 | 7 + 0 | R | S |

| 14* | M | I/H | 4 + 8 | 12 + 5 | L | BS |

| 15 | M | H | 0 + 9 | 8 + 1 | R | S |

| 16 | M | H | 3 + 8 | 9 + 10 | R | C |

| 17 | M | I | 0 + 7 | 7 + 7 | R | C |

| 18* | F | I | 1 + 0 | 12 + 4 | B | R: C/S L: C |

| 19 | F | I | 0 + 2 | 11 + 5 | R | C/S |

| 20* | F | H/I | 2 + 8 | 8 + 4 | R | C/CB |

| 21* | F | H | 0 + 2 | 12 + 4 | B | R:C/S L: S |

| 22 | F | I | 1 + 3 | 10 + 3 | B | L: C/S R: S |

| 23 | F | H | 0 + 9 | 10 + 1 | B | R: C/CB L: C/S |

| 24 | F | I | 2 + 11 | 8 + 9 | L | C |

| 25 | M | I | 7 + 0 | 10 + 9 | R | C/S |

| 26 | F | H | 0 + 9 | 12 + 8 | R | C/S |

| 27* | M | I | 4 + 10 | 12 + 4 | B | C/S |

| 28 | M | I | 0 + 11 | 11 + 11 | L | C/S |

| 29 | M | I | 6 + 5 | 8 + 6 | R | S |

*: recurrent stroke; F: female; M: male; H: haemorrhagic, I: ischemic; y: years, m: months; B: bilateral; R: right; L: left; C: cortical, S: subcortical; CB: cerebellum; TC: brainstem.

At followup, neurological examination showed no dysfunction at all in 3 children (of the 29 examined). All physical sequelae are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Physical sequelae at followup.

| Physical sequelae | Ischemic stroke (n = 18) | Haemorrhagic stroke (n = 9) | Ischemic and haemorrhagic stroke (n = 2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motor (hemiparesis and tetraparesis) | 17 | 6 | 1 |

| Speech dysfunction | 6 | 2 | — |

| Visual deficit | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Seizures | 10 | 4 | 1 |

| Conduct disorder | 3 | 1 | — |

| Global development retardation | 4 | 1 | — |

3.2. Educational Aspects

Six patients of the EG demonstrated severe neurological impairment. For this reason, they were not capable of performing the proposed tasks. Five of these patients attended a specialised educational institution. The only child who attended a regular school was too impaired cognitively to acquire elementary learning (such as acknowledging colours). In Table 3, the school data for the other 23 children are listed.

Table 3.

School data of the 23 children in the experimental group.

| Type of education | Ischemic stroke (n = 13) | Haemorrhagic stroke (n = 8) | Ischemic and haemorrhagic stroke (n = 2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specialised institution | 1 | — | — |

| Public school (regular classroom) | 9 | 6 | 2 |

| Public school (special classroom) | 2 | 2 | — |

| Private school (regular classroom) | 1 | — | — |

| School delay (in relation to age) | 8 | 5 | 1 |

It is important to highlight that despite a policy of continuous progression in regular education in Brazil, 14 out of the 23 children were held back (in relation to age and school year) (Table 3). All of the CG children were attending public regular schools and did not experience school delays.

3.3. Cognitive Evaluation

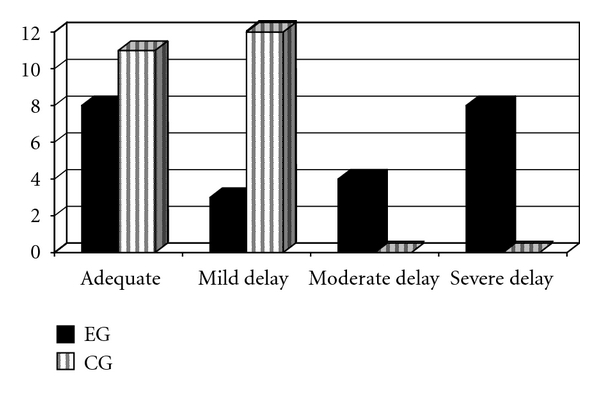

Cognitive evaluation using Piaget's clinical method [25] assessed 23 children of the EG and 23 of the CG. Eight in the EG had adequate performance. All of the other children had either mild (3/23), moderate (4/23), or severe (8/23) delays (Figure 1). The stroke type (ischemic or haemorrhagic), injured hemisphere (right, left, or bilateral), and recurrent stroke (occurred or did not occur) were not determinant factors for the best or worst performance of the EG children on operation tasks.

In the CG, 11 children had adequate performance. The other children (12/23) had a mild delay (Figure 2). The comparison between the CG and the EG showed that the performances of children who had strokes were significantly inferior to those of the control (P = .000, Mann-Whitney's test).

Figure 2.

Cognitive evaluation outcomes of the experimental and control groups (EG: control group; CG: control group).

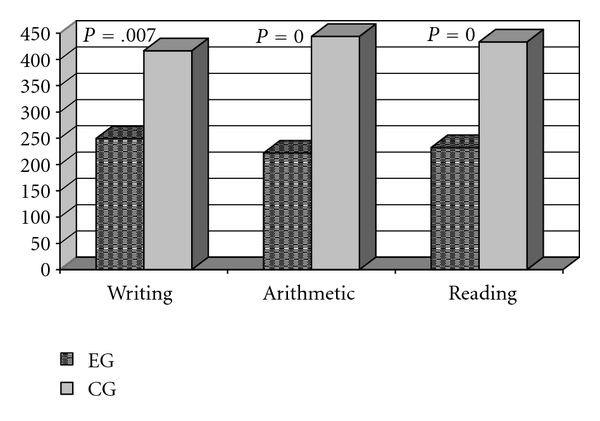

3.4. Writing, Arithmetic, and Reading Evaluation

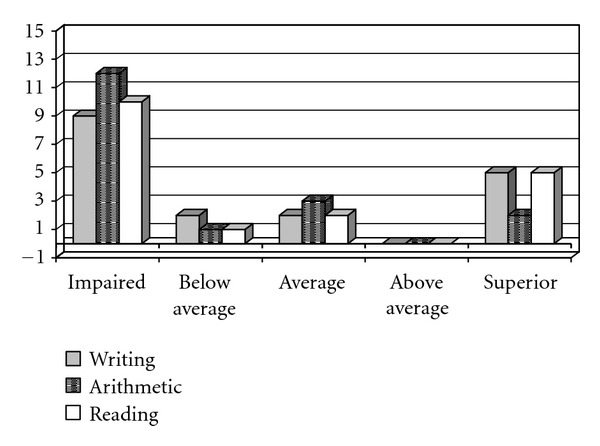

The school performance test (SPT) [26] was given to only 18 patients from the EG because five children were severely behind in school and were not capable of doing the test. Among these children, four had strokes at an early developmental stage.

Data analysis of the SPT showed that most of them had weaker performances in writing (9/18), arithmetic (12/18) and reading (10/18), (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3.

Performance of the experimental group (EG) on the writing, arithmetic, and reading test.

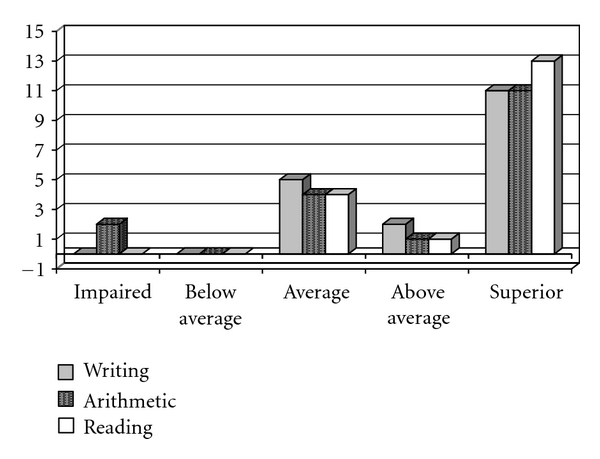

Figure 4.

Performance of the control group (CG) on the writing, arithmetic, and reading test.

In this sample, there was no relationship between the stroke type (ischemic or haemorrhagic), injured hemisphere and recurrent stroke (occurred or did not occur) and the writing, arithmetic, and reading subtest performances. However, there was a positive relationship between vascular injury at an early age and weaker performance on the test. Among the 10 children who had early strokes, six had impaired performances on the three subtests (writing, arithmetic, and reading).

The hypothesis that stroke might have negatively influenced writing, arithmetic and reading abilities was strengthened when the results were compared to those from the CG. The children who had strokes had performances significantly inferior (Mann-Whitney test) compared to those of the CG (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Comparison of EG and CG performances on the three subtests (writing, arithmetic, and reading) of the school performance test.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to understand cognitive development and learning in children who had strokes. In a previous study [17], cognitive delay was already observed in 15 children with ischemic stroke when they were compared to other children of the same gender and age. In the present study, an increase in the sample size and the inclusion of children with haemorrhagic stroke added important data that can be highlighted.

Among the children who were able to perform the tests, half of them demonstrated severe or moderate delays on Piaget's operation tasks, and most of them had inferior outcomes on the tests that assessed basic writing, arithmetic, and reading abilities. Furthermore, comparison with the control group revealed the significantly inferior performance of children with cerebrovascular disease. The consequences of poor performance were evident when educational aspects were analysed. Among the patients who attended regular schools, most showed learning disabilities and had repeated histories of school failure. This evidence has also been reported in other researchs [13, 14, 21–24].

The stroke type and affected hemisphere were not determinants for the impaired performances of the children in this study. However, there was a positive relationship between the onset of cerebrovascular injury and inferior performances on the tests.

Among the 29 children in the study, 20 had strokes in the time from birth up to the second year of life. Among these 20 children, 6 had cognitive impairments severe enough to exclude them from the assessment group for not responding to the tests. Another 5 children could not respond to the school performance test [26]. From the 9 patients who accomplished this test, most of them had low performances in writing, arithmetic, and reading.

Some authors have also drawn attention to the relationship between early stroke and impaired cognitive evolution [14, 21, 23, 27]. The first years of life are part of the most dynamic period for brain development. Lesions that occur in this period produce more severe impairments because they interfere with the reorganisation of the development of superior mental functions [23].

It is very important to emphasise that language is fundamental to the development of higher cortical functions. A large capacity for brain reorganisation is identified in early brain injury. Thus, adaptive plasticity is evident in the early stage of development. However, pathological plasticity (or maladaptive plasticity) could also occur, leading to a decrease in verbal and nonverbal skills and neuropsychological morbidity. After the first year of life, brain reorganisation is more limited but is more organised and is less likely to produce secondary sequelae [28]. Thus, children with cerebrovascular injury in later life would have less involvement in learning. This was confirmed in this study.

The concept of functional hierarchy [29] can also explain why children who have lesions at an early development stage have increasingly worse cognitive impairments. Initially, the primary zones of the brain that receive unimodal stimuli are fully active. In the case of primary zone lesion, there might be impairment in the development of multimodal areas (secondary and tertiary) due to a trophic stimulus deficit from sensorimotor activities [30]. Children who have had strokes generally have good motor development. Despite the hemiparesis, patients walk independently (with or without ortheses or other assistive devices). However, performance in other areas, such as daily life activities, communication, and socialisation, is less adequate in these patients [21]. Seizures that occurred after onset were also important because studies show that this clinical condition is related to cognitive impairment [13, 14, 18]. In this sample, 15 children had seizures, which corroborates the data reported by other studies.

5. Conclusions

Since the last decade, several studies have shown that childhood stroke can impair learning in children. This was evidenced in the present study.

Our data have shown that childhood stroke can impair cognitive development and learning in children. The lesion onset age seems to be an important factor for cognitive function development. Therefore, special attention must be given to patients who have had strokes in the initial developmental stage. Early cognitive rehabilitation might minimise the effects of the injury and provide a better quality of life for the children and their families.

Conflict of Interests

There was no conflict of interests in this study.

References

- 1.Lynch JK, Hirtz DG, DeVeber G, Nelson KB. Report of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke workshop on perinatal and childhood stroke. Pediatrics. 2002;109(1):116–123. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.1.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schoenberg BS, Mellinger JF, Schoenberg DG. Cerebrovascular disease in infants and children: a study of incidence, clinical features, and survival. Neurology. 1978;28(8):763–768. doi: 10.1212/wnl.28.8.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giroud M, Lemesle M, Gouyon JB, Nivelon JL, Milan C, Dumas R. Cerebrovascular disease in children under 16 years of age in the city of Dijon, France: a study of incidence and clinical features from 1985 to 1993. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1995;48(11):1343–1348. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(95)00039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Earley CJ, Kittner SJ, Feeser BR, et al. Stroke in children and sickle-cell disease. Neurology. 1998;51(1):169–176. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.1.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeVeber G. The Canadian Pediatric Stroke Study Group. Canadian paedoatric stroke registry: analysis of children with arterial ischemic stroke (abstract) Annals of Neurology. 2000;48:p. 526. [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeVeber G, Andrew M, Adams C, et al. Canadian Pediatric Ischemic Stroke Study Group. Cerebral sinovenous thrombosis in children. New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;345(6):417–423. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200108093450604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fullerton HJ, Wu YW, Zhao S, Johnston SC. Risk of stroke in children: ethnic and gender disparities. Neurology. 2003;61(2):189–194. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000078894.79866.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zahuranec DB, Brown DL, Lisabeth LD, Morgenstern LB. Is it time for a large, collaborative study of pediatric strokes. Stroke. 2005;36(9):1825–1829. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000177882.08802.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steinlin M, Roellin K, Schroth G. Long-term follow-up after stroke in childhood. European Journal of Pediatrics. 2004;163(4-5):245–250. doi: 10.1007/s00431-003-1357-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baumer JH. Childhood arterial stroke. Archives of Disease in Childhood: Education and Practice Edition. 2004;89(2):ep50–ep53. [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Moura-Ribeiro MV, Ciasca SM, Vale-Cavalcanti M, Etchebehere ECSC, Camargo EE. Cerebrovascular disease in newborn infants. Report of three cases with clinical follow-up and brain SPECT imaging. Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria. 1999;57(4):1005–1010. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x1999000600018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ciasca SM, Alves HL, Guimarães IE, et al. Comparação das avaliações neuropsicológicas em menina com doença cerebrovascular bilateral (moymoya) antes e após a intervenção cirúrgica. Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria. 1999;57(4):1036–1040. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x1999000600024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Schryver EL, Kappelle LJ, Jennekens-Schinkel A, Peters AC. Prognosis of ischemic stroke in childhood: a long-term follow-up study. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 2000;42(5):313–318. doi: 10.1017/s0012162200000554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ganesan V, Hogan A, Shack N, Gordon A, Isaacs E, Kirkham FJ. Outcome after ischaemic stroke in childhood. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 2000;42(7):455–461. doi: 10.1017/s0012162200000852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guimarães IE, Ciasca SM, de Moura-Ribeiro MVL. Neuropsychological evaluation of children after ischemic cerebrovascular disease. Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria. 2002;60(2-B):386–389. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2002000300009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blom I, De Schryver ELLM, Kappelle LJ, Rinkel JE, Jennekens-Schinkel A, Peters AC. Prognosis of haemorrhagic stroke in childhood: a long-term follow-up study. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 2003;45(4):233–239. doi: 10.1017/s001216220300046x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodrigues SD, Cíasca SM, de Moura-Ribeiro MVL. Ischemic cerebrovascular disease in childhood: cognitive assessment of 15 patients. Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria. 2004;62(3):802–807. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2004000500012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Härtel C, Schilling S, Sperner J, Thyen U. The clinical outcomes of neonatal and childhood stroke: review of the literature and implications for future research. European Journal of Neurology. 2004;11(7):431–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2004.00861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elias KMIF, dos Santos MFC, Ciasca SM, de Moura-Ribeiro MVLM. Processamento auditivo em criança com doença cerebrovascular. Pró-Fono Revista de Atualização Científica. 2007;19(4):393–400. doi: 10.1590/s0104-56872007000400012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guimarães IE, Ciasca SM, de Moura-Ribeiro MVL. Cerebrovascular disease in childhood: neuropsychological investigation of 14 cases. Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria. 2007;65(1):41–47. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2007000100010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hurvitz E, Warschausky S, Berg M, Tsai S. Long-term functional of outcome of pediatric stroke survivors. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation. 2004;11(2):51–59. doi: 10.1310/CL09-U2QA-9M5A-ANG2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steinlin M, Pfister I, Pavlovic J, et al. The first three years of the Swiss Neuropaediatric Stroke Registry (SNPSR): a population-based study of incidence, symptoms and risk factors. Neuropediatrics. 2005;36(2):90–97. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-837658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pavlovic J, Kaufmann F, Boltshauser E, et al. Neuropsychological problems after paediatric stroke: two year follow-up of Swiss children. Neuropediatrics. 2006;37(1):13–19. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-923932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jordan LC, Hillis AE. Hemorrhagic stroke in children. Pediatric Neurology. 2007;36(2):73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2006.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piaget J. Seis Estudos de Psicologia. 23rd edition. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Forense Universitária; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stein LM. TDE—Teste de Desempenho Escolar: Manual Para Aplicação e Interpretação. São Paulo, Brazil: Casa do Psicólogo; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Westmacott R, Askalan R, Macgregor D, Anderson P, Deveber G. Cognitive outcome following unilateral arterial ischaemic stroke in childhood: effects of age at stroke and lesion location. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 2010;52(4):386–393. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2009.03403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hernandez Muela S, Mulas F, Mattos L. Plasticidad neuronal funcional. Revista de Neurologia. 2004;38(supplement 1):S58–S68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luria AR. Fundamentos de Neuropsicologia. São Paulo, Brazil: Edusp; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Damasceno BP. Desenvolvimento das funções corticais superiores. In: de Moura-Ribeiro MVL, Gonçalves VMG, editors. Neurologia do Desenvolvimento da Criança. São Paulo, Brazil: Revinter; 2006. pp. 345–362. [Google Scholar]