Histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACi) induce diverse biological responses that include antiparasitic, antiproliferative, anti-inflammatory, and cognition-enhancing activities. In fact, inhibition of HDAC activity is now a clinically proven strategy for cancer treatment.[1] Several mechanisms have been proposed to account for the molecular basis of the biological activities of HDACi. The most widely accepted mechanism is the perturbation of chromatin remodeling as well as the acetylation status of a subset of nonhistone proteins.[2]

The broadness of the biological responses caused by HDACi could compromise their efficacy and may result in toxic side effects, which could therefore constitute a major obstacle to their long-term clinical use. For example, a large number of the identified HDACi currently under investigation as antiproliferative agents have elicited only limited in vivo antitumor activities and have not progressed beyond preclinical characterizations.[3–5] Moreover, the general clinical use of recently US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved FK-228 (romidepsin), a promising depsipeptide macrocyclic HDACi with a nanomolar HDAC inhibitory activity, may be hampered owing to an as-yet unresolved cardiotoxicity issue.[6] An understanding of the structural attributes that confer a specific biological response to HDACi is vital for their long-term therapeutic applications. However, this is slow in coming, principally due to a dearth of structural information on HDACs.

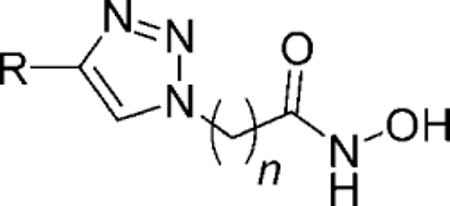

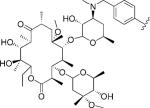

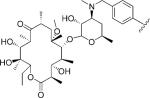

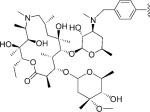

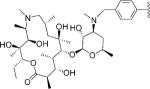

All HDACi so far reported fit a three-motif pharmacophoric model comprising a zinc-binding group (ZBG), a hydrophobic linker, and a recognition cap-group. Macrocyclic peptide moieties are the most complex of all HDACi recognition cap groups and present an excellent opportunity for the modulation of their biological activities. Aware of the challenges associated with the development of peptide-based therapeutics, one of our goals is the identification of nonpeptide isosteres for the recognition cap-group moieties of macrocyclic peptide HDACi. We reported recently that nonpeptide macrocyclic skeletons derived from 14- and 15-membered macrolides are suitable as surrogates for the cap groups of macrocyclic HDACi.[7]

To pursue the depth of the biological activities of these nonpeptide macrocyclic HDACi further, we herein characterize their antiparasitic activities against Plasmodium falciparum and Leishmania donovani. P. falciparum and L. donovani are the causative parasites of malaria and leishmaniasis, respectively, two human diseases that constitute a serious threat to public health in tropical and subtropical countries.[8,9] These human pathogens are responsive to HDACi because their genomes contain multiple genes encoding different HDAC isozymes, some of which are essential for their survival and proliferation.[10,11] The structure–activity relationship (SAR) of the antimalarial and antileishmanial activities of HDACi is just beginning to emerge,[12–15] and much needs to be done to decipher this important bioactivity of HDACi completely. We report that spacer-group length is a major structural determinant of antimalarial and antileishmanial activities of this class of nonpeptide macrocyclic HDACi. Specifically, we found that for either macrolide skeleton, the antimalarial activities peak in analogues that have six methylene spacer groups separating the active-site zinc-binding hydroxamate moiety from the triazolyl moiety of the recognition cap-group, whereas antileishmanial activities are optimum in analogues that have eight or nine methylene spacer groups. A similar spacer-length restriction on antimalarial activity has been observed for suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA)-like and macrocyclic peptide HDACi.[12,14,15]

We evaluated the in vitro antimalarial activity of all nonpeptide macrocyclic HDACi herein disclosed by using chloroquine-sensitive (D6, Sierra Leone) and chloroquine-resistant (W2, Indochina) strains of P. falciparum. The antileishmanial activities of the compounds were initially tested against the promastigote stage of L. donovani. Plasmodium growth inhibition was determined by a parasite lactate dehydrogenase assay by using Malstat reagent,[16] whereas inhibition of the viability of the promastigote stage of L. donovani was determined by using standard Alamar blue assay, which was modified to a fluorometric assay.[17] Amphotericin B and pentamidine (standard antileishmanial agents), chloroquine and artimisinin (standard antimalarial agents), and suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (a standard HDACi) were all used as positive controls. To determine the selective toxicity index, all compounds were tested against monkey kidney epithelial cells (Vero), a nontransformed mammalian cell line, by using Neutral Red assay.[18]

These nonpeptide macrocyclic HDACi potently inhibit the proliferation of both the sensitive and the resistant strains of P. falciparum with an IC50 value ranging from 0.1 to 3.5 μg mL−1 (Table 1). In particular, compounds 5–8, derived from either the 14- or 15-membered macrolide analogues and having six methylene spacers separating the triazole ring from the zinc-binding hydroxamic acid group (n=6), have the most potent antimalarial activities in this series. These compounds are equipotent or are more than four times more potent than the control compound SAHA. Moreover, they are several folds more selectively toxic to either strain of P. falciparum compared with SAHA.

Table 1.

HDAC inhibition, antileishmanial (promastigote stage of L. donovani) and antimalarial (P. falciparum) activity, and cytotoxicity of the lead macrocyclic HDACi.

| ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lead | R | n | HDAC[a] | L. donovani[b] | P. falciparum[c] | Cytotoxicity[c] | S.I. | |||

| IC50 [nm] | IC50 [μg mL−1] | IC90 [μg mL−1] | IC50 (D6 clone) [μg mL−1] | IC50 (W2 clone) [μg mL−1] | IC50 (Vero) [μg mL−1] | D6 | W2 | |||

| 1 |

|

5 | 37.0 | NA | NA | 0.897±0.115 | 0.965±0.076 | NC | >5.3 | >5.1 |

| 2 |

|

5 | 44.3 | NA | NA | 1.295±0.214 | 1.489±0.155 | NC | >4.0 | >3.4 |

| 3 |

|

5 | 91.6 | NA | NA | 1.274±0.065 | 1.697±0.165 | NC | >4.0 | >3.0 |

| 4 |

|

5 | 88.8 | NA | NA | 1.389±0.043 | 1.776±0.107 | NC | >3.7 | >2.8 |

| 5 | as for compound 1 | 6 | 4.1 | 18.24±1.17 | >40 | 0.276±0.022 | 0.317±0.012 | NC | >17.6 | >15.4 |

| 6 | as for compound 2 | 6 | 1.9 | NA | NA | 0.183±0.007 | 0.248±0.026 | NC | >26.4 | >19.0 |

| 7 | as for compound 3 | 6 | 13.9 | NA | NA | 0.234±0.057 | 0.098±0.006 | NC | >20.7 | >47.6 |

| 8 | as for compound 4 | 6 | 10.6 | NA | NA | 0.158±0.007 | 0.108±0.012 | NC | >29.8 | >28.0 |

| 9 | as for compound 1 | 7 | 55.6 | 21.45±0.54 | 34.76±4.55 | 2.548±0.145 | 2.189±0.451 | NC | >1.9 | >2.4 |

| 10 | as for compound 2 | 7 | 123.0 | NA | NA | 3.176±0.085 | 2.734±0.245 | NC | >1.6 | >1.8 |

| 11 | as for compound 3 | 7 | 58.9 | NA | NA | 2.419±0.153 | 2.321±0.074 | NC | >2.0 | >2.1 |

| 12 | as for compound 4 | 7 | 72.4 | NA | NA | 3.527±0.098 | 3.243±0.248 | NC | >1.4 | >1.5 |

| 13 | as for compound 1 | 8 | 169.8 | 3.41±0.35 | 7.12±0.57 | 1.725±0.153 | 1.107±0.043 | NC | >2.8 | >4.8 |

| 14 | as for compound 3 | 8 | 145.5 | 21.76±0.98 | 35.35±4.11 | 1.117±0.076 | 0.833±0.054 | NC | >4.3 | >5.7 |

| 15 | as for compound 1 | 9 | 223.4 | 3.47±0.45 | 7.19±0.65 | 1.443±0.019 | 0.828±0.066 | NC | >3.4 | >6.0 |

| 16 | as for compound 3 | 9 | 226.7 | 3.54±0.27 | 7.15±0.67 | 0.842±0.112 | 0.883±0.043 | NC | >5.7 | >5.4 |

| chloroquine | - | NT | NT | NT | 0.017 | 0.125 | NT | NT | ||

| artemisinin | - | NT | NT | NT | 0.004 | 0.006 | NT | NT | ||

| pentamidine | - | NT | 0.89±0.05 | 1.78±0.08 | NT | NT | NT | NT | ||

| amphotericine B | - | NT | 0.18±0.02 | 0.32±0.04 | NT | NT | NT | NT | ||

| SAHA | - | 65 | 21.5±3.51 | 51.7±8.1 | 0.279±0.077 | 0.392±0.045 | 1.375±0.255 | 4.9 | 3.5 | |

| azithromycin | - | NT | NA | NA | NA | NA | NC | - | - | |

From reference [13].

Maximum tested concentration=40 μg mL−1.

Maximum tested concentration=4.8 μg mL−1.

NA=Not active up to the highest concentration tested. NC=Not cytotoxic up to the highest concentration tested. NT=Not tested. S.I.=Selectivity Index (IC50 Vero/IC50).

The antimalarial activities of these macrocyclic HDACi followed a similar trend to that of their anti-HDAC activity against HDAC-1/2 from HeLa nuclear extract,[7] suggesting that the parasite HDACs could be one of their intracellular targets. To obtain evidence for the involvement of P. falciparum HDACs as one of the potential intracellular targets for these compounds, we investigated the activities of selected analogues against P. falciparum HDAC-1 (pfHDAC-1). The compound selection criterion for the anti-pfHDAC-1 activity assay was based on the spread of the antimalarial potency. Gratifyingly, many of these compounds inhibited the activity of pfHDAC-1 with IC50 values that closely mirrored their antimalarial activities (Table 2). Specifically, compounds 5 and 7, which represent the 14- and 15-membered analogues, respectively, demonstrated the highest anti-pfHDAC-1 activities with low nanomolar IC50 values. Coincidentally, these analogues also have the most potent antimalarial activity. Compounds 1, 2, 4, 15, and 16, analogues with attenuated antimalarial activities relative to 5 and 7, are less potent against pfHDAC-1. Although there is approximately a two-fold spread in the antimalarial activities of these later compounds, there is no clear trend in their anti-pfHDAC-1 activity. This may be partly due to differences in the cell penetration abilities of these compounds.

Table 2.

In vitro inhibition of pfHDAC-1 by selected lead HDACi.[a]

| Lead | IC50 [nm] |

|---|---|

| 1 | 134±4.5 |

| 2 | 93±3.6 |

| 4 | 62±5.3 |

| 5 | 30±2.7 |

| 7 | 29±0.9 |

| 15 | 401±19.7 |

| 16 | 182±13.6 |

| SAHA | 98±2.8 |

Data obtained through contract arrangement with BPS Bioscience (San Diego, USA; www.bpsbioscience.com).

Interestingly, compounds 1–12 (n=5–7) are devoid of antileishmanial activity against the promastigote stage of L. donovani, except 5 and 9, which have only a modest activity. This result is contrary to our previous data on simple aryltriazolyl hydroxamates, which have antimalarial and antileishmanial activities that follow a similar trend.[19] A comparison of the antileishmanial activities of compounds 13 and 14, analogues with n=8, revealed an interesting disparity between the activity of 14- and 15-membered macrocyclic rings. The 14-membered compound 13 is five to six times more potent than its 15-membered congener 14. However, this disparity dissipates after a single methylene group extension (n=9) because compounds 15 and 16 have virtually indistinguishable activity against the promastigote stage of L. donovani. Comparatively, compounds 13, 15, and 16, analogues with the most potent antileishmanial activities, are about seven to ten times more potent than SAHA and approximately three times less potent than pentamidine.

Encouraged by this promising activity against the promastigote stage of L. donovani, we proceeded to screen all compounds against the axenic amastigote stage of L. donovani. The amastigote stage is the second evolutive form of L. donovani that thrives, and hence is responsible for systemic infections, in mammalian hosts.[20] Inhibition of the viability of the amastigote stage was determined as described for the promastigote stage, except that incubation was at 37 instead of 26°C.[21] We observed that compounds 1–12 and 14 are either modestly active or inactive against the amastigote stage of L. donovani (Table 3). This closely mirrored the effects of these compounds against the promastigote stage (Table 1). Among the remaining three compounds with the most potent antipromastigote activities, only 15 inhibits the viability of the amastigote stage with an IC50 value comparable to that of the promastigote stage (Table 3). The apparent lack of concordance in the activities of 13, 15, and 16 against the promastigote and amastigote stages is rather surprising. Nevertheless, 15 is an intriguing lead compound, the antileishmanial activity of which warrants further study.

Table 3.

Inhibition values for lead macrocyclic HDACi against the axenic amastigote stage of L. donovani.

| Lead | Antileishmanial activity[a] | |

|---|---|---|

| IC50 [μg mL−1] | IC50 [μg mL−1] | |

| 1 | 23.3±4.3 | >40 |

| 2 | 37.4±6.1 | >40 |

| 3 | 37.8±3.1 | >40 |

| 4 | 35.4±1.9 | >40 |

| 5 | 31.1±2.6 | >40 |

| 6 | NA | NA |

| 7 | NA | NA |

| 8 | NA | NA |

| 9 | 19.7±2.9 | >40 |

| 10 | 28.4±2.2 | >40 |

| 11 | 40.0±0.0 | >40 |

| 12 | 29.4±4.1 | >40 |

| 13 | 16.3±3.1 | 32.4±1.1 |

| 14 | 33.2±1.7 | >40 |

| 15 | 5.1±0.7 | 21.3±2.1 |

| 16 | 19.4±1.1 | 32.3±3.2 |

| azithromycin | NA | NA |

Maximum tested concentration=40 μg mL−1.

NA=Not active up to the highest concentration tested.

The starting macrocyclic scaffolds, erythromycin and azithromycin, from which these HDACi are derived have been reported to possess some antiparasitic activity.[22] To account for the possibility of the contribution of the latent antiparasitic activity of these scaffolds to the observed bioactivity of these macrocyclic HDACi, we included azithromycin as a negative control in the whole-cell activity studies. We observed that azithromycin has no antimalarial and antileishmanial activity up to the highest concentration tested (Table 1 and Table 3).

The observed disparity in the trend of the antimalarial and antileishmanial activities of these nonpeptide macrocyclic HDACi may have implication in the organization of the active sites of the relevant P. falciparum and L. donovani HDAC isozymes. Our observation provides additional evidence on the suitability of HDAC inhibition as a viable therapeutic option to curb infections caused by apicomplexan protozoans and trypanosomatids,[12–15] and could facilitate the identification of other HDACi that are more selective for either parasite. Efforts are underway in our laboratory to investigate the in vivo efficacy of selected compounds in appropriate murine parasite models.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the Georgia Institute of Technology, the Blanchard fellowship and by NIH Grant R01 A131217 (A.K.O.). NCNPR is partially supported by USDA-ARS scientific cooperative agreement no. 58-6408-2-0009. P.C.C. and W.G. are recipients of the GAANN predoctoral fellowship from the Georgia Tech Center for Drug Design, Development and Delivery. John Trott and Rajnish Sahu at NCNPR provided technical assistance for antimalarial and antileishmanial assays, respectively.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cmdc.201000087.

References

- [1].Marks PA. Oncogene. 2007;26:1351. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bolden JE, Peart MJ, Johnstone RW. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov. 2006;5:769. doi: 10.1038/nrd2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kelly WK, O'Connor OA, Marks PA. Expert Opin. Invest. Drugs. 2002;11:1695. doi: 10.1517/13543784.11.12.1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Rosato RR, Grant S. Expert Opin. Invest. Drugs. 2004;13:21. doi: 10.1517/13543784.13.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Yoo CB, Jones PA. Nat. Mater. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov. 2006;5:37. doi: 10.1038/nrd1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].a) Shah MH, Binkley P, Chan K, Xiao J, Arbogast D, Collamore M, Farra Y, Young D, Grever M. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006;12:3997. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Piekarz RL, Frye AR, Wright JJ, Steinberg SM, Liewehr DJ, Rosing DR, Sachdev V, Fojo T, Bates SE. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006;12:3762. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Oyelere AK, Chen PC, Guerrant W, Mwakwari SC, Hood R, Zhang Y, Fan Y. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:456. doi: 10.1021/jm801128g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Croft SL, Sundar S, Fairlamb AH. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2006;19:111. doi: 10.1128/CMR.19.1.111-126.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Snow RW, Guerra CA, Noor AM, Myint HY, Hay SI. Nature. 2005;434:214. doi: 10.1038/nature03342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].a) Ivens AC, Peacock CS, Worthey EA. Science. 2005;309:436. [Google Scholar]; b) Vergnes B, Sereno D, Tavares J, da Silva AC, Vanhille L, Madjidian-Sereno N, Depoix D, Monte-Alegre A, Ouaissi A. Gene. 2005;363:85. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Ouaissi M, Ouaissi A. J. Biomed. Biotech. 2006:1. doi: 10.1155/JBB/2006/13474. ID 13474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Adriano M-A, Vergnes B, Poncet J, Mathieu-Daude F, da Silva AC, Ouaissi A, Sereno D. Parasitol. Res. 2007;100:811. doi: 10.1007/s00436-006-0352-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].a) Joshi MB, Lin DT, Chiang PH, Goldman ND, Fujioka H, Aikawa M, Syin C. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1999;99:11. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(98)00177-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Mukherjee P, Pradhan A, Shah F, Tekwani BL, Avery MA. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008;16:5254. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Andrews KT, Tran TN, Wheatley NC, Fairlie DP. Curr Top Med Chem. 2009;9:292. doi: 10.2174/156802609788085313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Sriwilaijaroen N, Boonma S, Attasart P, Pothikasikorn J, Panyim S, Noonpakdee W. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009;381:144–147. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.01.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Andrews KT, Tran TN, Lucke AJ, Kahnberg P, Le GT, Boyle GM, Gardiner DL, Skinner-Adams TS, Fairlie DP. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008;52:1454. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00757-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Darkin-Rattray SJ, Gurnett AM, Myers RW, Dulski PM, Crumley TM, Allocco JJ, Cannova C, Meinke PT, Colletti SL, Bednarek MA, Singh SB, Goetz MA, Dombrowski AW, Polishook JD, Schmatz DM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:13143. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].a) Colletti SL, Myers RW, Darkin-Rattray SJ, Gurnett AM, Dulski PM, Galuska S, Allocco JJ, Ayer MB, Li C, Lim J, Crumley TM, Cannova C, Schmatz DM, Wyvratt MJ, Fisher MH, Meinke PT. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2001;11:107. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(00)00604-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Dow GS, Chen Y, Andrews KT, Caridha D, Gerena L, Gettayacamin M, Johnson J, Li Q, Melendez V, Obaldia N, III, Tran TN, Kozikowski AP. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008;52:3467. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00439-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Patel V, Mazitschek R, Coleman B, Nguyen C, Urgaonkar S, Cortese J, Barker RH, Jr., Greenberg E, Tang W, Bradner JE, Schreiber SL, Duraisingh MT, Wirth DF, Clardy J. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:2185. doi: 10.1021/jm801654y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Makler MT, Ries JM, Williams JA, Bancroft JE, Piper RC, Gibbins BL, Hinriches DJ. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1993;48:739. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1993.48.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Mikus J, Steverding D. Parasitol. Int. 2000;48:265. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5769(99)00020-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Babich H, Borenfreund E. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1991;57:2101. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.7.2101-2103.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Patil V, Guerrant W, Chen PC, Gryder B, Benicewicz DB, Tekwani BL, Oyelere AK. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010;18:415. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.10.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kima PE. Int. J. Parasitol. 2007;37:1087–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Luque-Ortega JR, Martínez S, Saugar JM, Izquierdo LR, Abad T, Luis JG, Pinero J, Valladares B, Rivas L. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004;48:1534–1540. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.5.1534-1540.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].a) Krolewiecki AJ, Leon S, Scott P, Abraham D. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2002;67:273–277. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.67.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) de Oliveira-Silva F, de Morais-Teixeira E, Rabello A. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2008;78:745–749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.