Introduction

Since completion of the draft sequence of the human genome in 2000, the landscape of biomedical research has undergone a rapid transformation. Growing knowledge of genome structure and variation has spawned development of technologies that allow researchers to study thousands of genes, transcripts, and proteins simultaneously. This has expanded biomedical science beyond reductionist approaches that test the function of individual genes to less biased approaches that study the behavior of many or all genes in homeostasis and disease. Such studies have been grouped under the broad label of ‘functional genomics’, which can be defined as the branch of biology that seeks to uncover the properties and function of the entirety of an organism’s genes and gene products1. Functional genomics is fueling an explosion of new insights in biology and medicine, and many of these insights were completely unanticipated. Because these advances have begun to influence clinical practice2, 3, physicians will be expected to understand the potential uses and limitations of functional genomics in clinical settings.

The purpose of this review is to provide a conceptual overview of functional genomics applied to the practice of cardiovascular medicine. We begin with a review of commonly used terms and approaches, and then describe examples of their use for screening, diagnosis, and treatment selection in clinical cardiology. We will also highlight emerging trends and speculate about where the field is headed in the near term. Though some predictions will be overly optimistic and some major advances unanticipated, we hope this review will nevertheless help prepare cardiologists for their role in the application of genome science to the diagnosis and treatment of disease. This review is part of a series that introduces several related areas of cardiovascular genetics and genomics4. We will refer to these other contributions to guide further reading and avoid duplication when appropriate.

Terms and Concepts

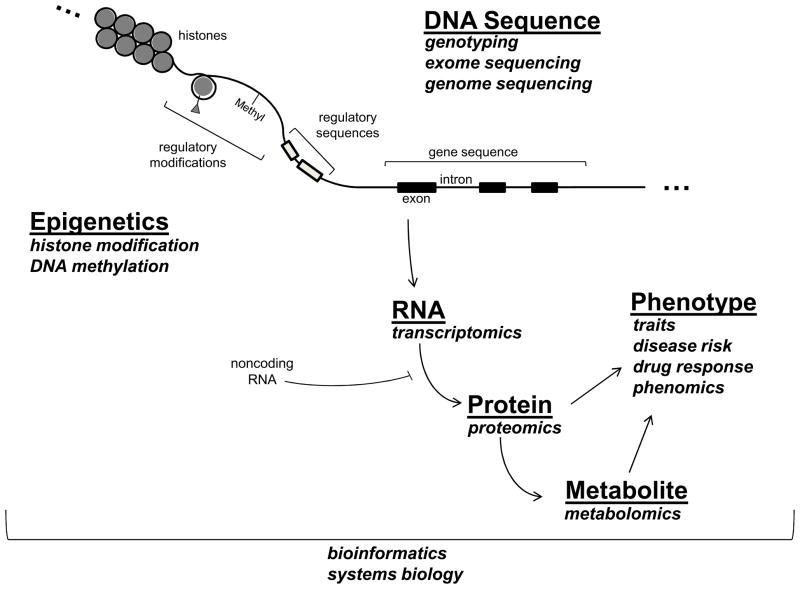

Defining how the genome shapes our risk and manifestations of disease is clearly an ongoing process. Figure 1 provides a very simplified model of how information encoded in the genome flows from DNA through various steps to ultimately influence phenotype, highlighting approaches now in common use to study each step. Although the central dogma of DNA → RNA → Protein remains largely intact, discoveries in genome science have revealed substantially more complexity than was previously appreciated, and it is a safe bet that the current picture is quite incomplete. These advances have also created advance an ever-evolving vocabulary of ‘omics’ terms and concepts. We briefly review these below.

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of how information encoded in the genome flows from DNA through various steps to ultimately influence phenotype.

Genetics vs. Genomics vs. Functional Genomics

As physicians, we are all familiar with basic concepts of genetics as the study of inherited traits, or phenotypes. Phenotypes comprise a broad category of individual characteristics, which can range from physical features such as height and eye color to an inherited tendency to develop disease. The basic unit of inheritance is the gene, which is passed on to offspring as a specific sequence of DNA (though recent research has identified other mechanisms of heritability, described below). In contrast to genetics, the term genomics has variable meanings depending on the context. The common theme across all uses of the term is the study of genome-level information. This includes the entirety of inherited DNA sequences2 and a recognition that information in one region (or ‘locus’) of the genome is modified by information at many other loci and also by non-genetic factors5. Historically, genomics has referred principally to ‘static’ DNA sequences, which, under normal circumstances, are fixed within an individual. Functional genomics also includes the study of the ‘dynamic’ changes in gene products (transcripts, proteins, metabolites) and how these changes mediate normal and abnormal biological function.

DNA Sequence

A very direct way to gain insight into genome function is to identify inherited DNA sequences that track with the presence, or absence, of disease phenotypes. In linkage studies, DNA sequence variation is tracked within family members who appear to have disorders that follow a Mendelian pattern of inheritance (dominant, recessive, sex-linked, etc.). Linkage studies have the potential to identify disease causing mutations with strong effects on gene function and on clinical phenotype. Well known examples include identification of disease causing mutations in families with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and Marfan’s syndrome, as recently reviewed by Kim et al6. By contrast, in association studies, DNA sequence variation is compared between large groups of cases and unaffected controls, or across a spectrum of a continuous trait, such as lipid levels or left ventricular mass, to identify DNA variants of interest. There are now numerous examples, including genome-wide association studies (GWAS) that have successfully identified common DNA variants that affect cardiovascular phenotypes such as myocardial infarction, dyslipidemia, atrial fibrillation, and many others7. The majority of GWAS published to date identify disease-modifying genetic variants that have a relatively small impact, but that are relevant to large numbers of individuals because the variants identified are common. A related criticism of GWAS is that many of the findings identify genomic regions, or loci, associated with disease, without determining specific disease-causing variants that alter gene function. However, more detailed sequence analysis of these loci is beginning to uncover specific disease causing variants8, 9.

Both linkage and association studies depend on the availability of technologies to comprehensively assess DNA sequences. Most published studies identify loci of interest by surveying the frequency of common genetic variations (e.g., single nucleotide polymorphisms or SNPs) scattered at intervals across the genome. Increasingly, direct sequencing of DNA in large numbers of subjects is becoming the technological platform of choice and is enabling comprehensive study of all DNA sequence variation, including common variants and a broader spectrum of rare variants10. Complete genome sequencing is still expensive, but an intermediate approach that is currently popular is ‘exome sequencing.’ Here the portions of DNA known to directly encode amino acids sequences (the exons) are sequenced in large populations to identify the full set of amino-acid altering variants associated with disease2. As technology becomes cheaper, this will undoubtedly expand to include whole genome sequencing11.

Epigenetics

Although we often think of DNA sequence as the major determinant of inheritance, research has identified mechanisms of inheritance that are independent of DNA sequence, and hence termed ‘epi-genetic’12, 13. For example, DNA can be methylated at specific loci via a highly regulated process, and the methylation status of genomic regions can have a major effect on the expression genes in that region. Chemical modifications of histone proteins that affect the packaging of DNA in chromatin are another epigenetic means of regulating transcription. Genome-wide DNA methylation and histone modification patterns are sometimes referred to as ‘epigenetic marks’, and have several interesting properties. First, they can be passed on from parent cells to daughter cells, and potentially across generations, providing a mechanism of inheritance14. Second, they respond to exposures. For example, emerging data indicate that in utero exposure to stresses such as starvation can alter DNA methylation patterns of genes involved in growth and metabolism to affect organ development and future cardiovascular risk. Exposures such as tobacco smoke and air pollution may modulate cardiovascular risk in part by inducing epigenetic changes15. Animal models have also demonstrated a substantial role for histone modification in cardiac hypertrophy, and drugs that target histone-deacetylases (HDACs) have been considered as a therapeutic strategy for heart failure 16.

Transcriptomics

Most genes exert their biological effects via transcription to messenger RNA (gene expression) in a tissue of interest. Unlike DNA sequence variation, which is normally fixed within an individual, there is tremendous variability in gene expression in different tissues and in response to stimuli. Regulation of gene expression is highly complex and underlies many fundamental biological processes such as growth, differentiation into organs and tissues, disease pathogenesis, and response to drug therapy. Transcriptomics (sometimes referred to as gene expression profiling) is the quantitative study of all genes expressed in a given biological state, and it can provide important insights into these processes. Transcriptomic studies are accomplished through use of gene expression microarrays or RNA sequencing to quantify the abundance of all transcripts expressed in a tissue of interest under a given biological state. The resulting data contain a large amount of information regarding genes that are turned on or turned off in the setting of disease. This information can be leveraged to identify individual genes of interest, or panels of genes that change together in an informative way about disease. In recent years, it has become apparent that many RNAs do not encode proteins themselves but can nevertheless have profound pathophysiological effects. These noncoding RNAs, including micro RNAs (miRs), can regulate the translation of other transcripts into proteins. Because a single miR often targets (inhibits) multiple transcripts in related biological pathways, a single miR can fine tune complex biological processes such as myocardial hypertrophy or inflammation17. The importance of miRs in cardiovascular disease is the subject of other recent reviews17, 18.

Proteomics and Metabolomics

Once regulated and expressed, most RNA transcripts are translated into proteins which exert physiological and pathological effects. Just as transcriptomics endeavors to quantify all of the transcripts within a particular biological specimen, the goal of proteomics is to provide a similar survey of translated proteins within a biological sample under particular circumstances. Since many proteins undergo chemical modifications (e.g., phosphorylation, nitrosylation, acetylation, etc.) to regulate cellular structure and function, proteomics also seeks to study chemical modification of proteins in a given biological state. Proteins with enzymatic activity chemically modify a large set of smaller biochemical intermediates in the course of normal and abnormal metabolism. Metabolomics is the quantitative study of all intermediary metabolites in a given biological state. For example, recent studies have identified a profile of proteins and metabolites that implicates changes in structural proteins, oxidant stress, and altered myocardial metabolism as contributors to the increased susceptibility to atrial fibrillation observed in experimental heart failure19. The development of high-throughput proteomic and metabolomic survey techniques has been challenged by the diversity of relevant chemical modifications affecting proteins and metabolites compared with the simpler changes affecting nucleotides. Nevertheless, advances in mass spectroscopy, nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, protein microarrays and other techniques have substantially enhanced the ability to execute such surveys, including several that are being applied to clinical cardiovascular disease20–23.

Phenotyping

Applying functional genomics to understand disease requires accurate assessment of phenotype. This can be a major challenge because clinical phenotypes such as cardiovascular disorders have substantial biological heterogeneity. For example, congestive heart failure is a common clinical phenotype, but there are numerous underlying subtypes that span a broad range of etiologies (e.g., ischemia, hypertension, ‘idiopathic’, etc.), and a broad spectrum of ventricular dysfunction (e.g., preserved versus reduced ejection fraction), each of which may have different underlying genetic contributors. There is clearly an inherited tendency to develop heart failure24, but identifying the relevant genomic loci has been a challenge25. Successful examples have focused on more narrowly defined heart failure phenotypes, such as subclinical cardiac remodeling26, advanced systolic heart failure9, 27, or idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy28. These and other examples highlight how experienced clinicians play an essential role in functional genomics by refining phenotype definitions. This often includes integrating measures of subclinical disease, such as imagining techniques and circulating biomarkers, with standard clinical data obtained from history and physical examination. Recent studies have attempted to formalize this process by incorporating tens or hundreds of phenotype measurements together in order to enhance phenotype specificity, an approach called ‘deep-phenotyping’ or ‘phenomics’29. Such efforts may ultimately feed back to clinical practice by revealing objective ways to classify heterogeneous disease syndromes.

Bioinformatics and Systems Biology

Every approach described above generates a vast quantity of data. Making sense of this information, and putting new information into context with a huge volume of existing genomic data, has mandated a new set of tools. Bioinformatics uses computer science and mathematics to integrate large datasets and answer biological questions. Interestingly, many of the concepts of bioinformatics were developed well before the human genome project30, but functional genomics technologies, the internet, and a culture of data sharing have propelled the field, which now touches nearly all domains of biomedical research31. Simple examples include easily accessible web-tools that indicate which areas the genome have been conserved across evolution (and are likely to be functionally important), which genes are expressed in a range of normal and abnormal tissues, what is the predicted function of a protein based on its sequence, etc. More complex tools provide researchers with methods to analyze output from functional genomics experiments. As new technologies continue to outstrip our ability to analyze and understand the resulting information, bioinformatics is often the rate limiting step.

Availability of genome scale data has also inspired more ‘global’ ways of thinking about biological processes as integrated systems. So-called ‘systems biology’ applies network theory to model how all genes and their products are inter-related in the setting of normal homeostasis and disease32. Several studies have demonstrated how systems biology can integrate data from DNA sequence, gene expression in tissues, and clinical phenotypes to uncover mechanisms of cardiovascular disease and identify therapeutic targets33–37. Systems biology in cardiovascular research has been recently reviewed by Lusis and Weiss38.

Clinical Applications of Functional Genomics

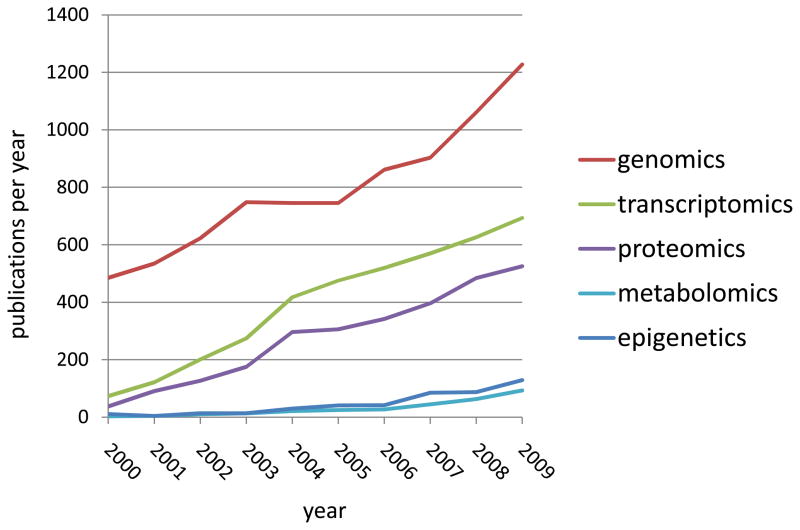

The currently limited applications of functional genomics for the clinical cardiologist are accelerating (Figure 2) and are expected to increase substantially over the next decade. In this section we highlight ways in which functional genomics is currently being used in the setting of screening, diagnosis, and treatment of cardiovascular disorders. Our aim is not to provide an exhaustive list of applications, but rather to illustrate the clinical utility of recent advances.

Figure 2.

Annual publication trends in functional genomics of human cardiovascular disorders. Data obtained from PubMed.

Screening for Cardiovascular Risk

As recently reviewed by Kim et al6, disease causing mutations for a wide range of Mendelian cardiac disorders have been revealed through linkage studies, thereby permitting screening of family members to identify mutation carriers for early intervention. A more controversial task is the use of common genetic variants identified in GWAS for risk prediction in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. For example, more than a dozen common DNA sequence variants have now been associated risk of myocardial infarction (MI) in multiple populations39. Although these associations are undoubtedly real, carrying a risk variant confers an extremely small increase in risk (generally 1.2-fold or less). A series of studies has attempted to compute aggregate risk conferred across multiple MI variants by summing the information into a genetic risk score40, 41. Such genetic risk scores are, again, convincingly associated with MI risk, but they add very little in the assessment of individual patient risk compared to simple clinical predictors such as the Framingham Risk Score. As such, the goal of risk prediction using genomic information is still a work in progress (see42 for a detailed review). It is important to note, however, that the field is still young, and using predictors identified in GWAS is just skimming the surface with regard to potential genomic contributors to cardiovascular risk. Risk prediction may improve substantially with inclusion of rare DNA variants identified via sequencing, or by incorporating other types of functional genomic data into predictive models, such as epigenetic marks, blood transcriptomics, and metabolomic biomarkers. Accomplishing this will again require novel analytic strategies43 and extensive validation in clinical cohorts.

New Approaches in Cardiovascular Diagnosis

Definitive diagnostic tests in cardiovascular medicine often subject patients to invasive procedures. Providing non-invasive alternatives that reduce the need for invasive testing is a well established clinical goal, and functional genomics is beginning to provide molecular diagnostics for this purpose. An early example already in clinical use is the noninvasive diagnosis of cardiac allograft rejection using blood gene expression. After Horwitz et al demonstrated that clinically significant allograft rejection could be identified and tracked via monitoring of the peripheral blood transcriptome44, Deng et al identified an 11-gene PCR-based assay of peripheral blood cells that was able to distinguish biopsy-proven moderate/severe rejection with excellent sensitivity and good specificity45. Building on these results, the Invasive Monitoring Attenuation through Gene Expression (IMAGE) trial compared the routine use of endomyocardial biopsies for monitoring rejection with a more selective use of endomyocardial biopsy guided by a gene-expression profiling test called AlloMap™ 46 and noninvasive cardiac imaging. Both strategies resulted in equivalent clinical outcomes, but patients who were monitored with gene-expression profiling underwent far fewer biopsies per person-year of follow-up than did patients who were monitored with routine biopsy (0.5 vs. 3.0, P<0.001). The Personalized Risk Evaluation and Diagnosis In the Coronary Tree (PREDICT) study recently demonstrated a similar ability of the blood transcriptome to aid in the diagnosis of obstructive coronary artery disease47. Here the bar for clinical application is higher since noninvasive approaches to diagnose coronary artery disease already exist, and the added value of a transcriptomic profile must be rigorously tested against these standards48. Analogous studies are underway to develop novel proteomic and metabolomic profiles to aid in cardiovascular diagnosis and risk stratification22, 49, 50.

Cardiovascular Pharmacogenomics

Pharmacogenomics is the study of how genetic variation affects the clinical response to drugs, with the implicit assumption that pharmacogenomic insights will enhance efficacy and reduce toxicity. At this time, pharmacogenomics is most evolved in cancer therapeutics, where tumor genotyping that predicts therapeutic failure51 or increased toxicity risk52–54 has sparked development of “companion diagnostics”: focused genetic testing to define whether a particular therapy has a favorable therapeutic index55.

Emerging pharmacogenomic applications in cardiovascular treatment include examples of genetic variation affecting the likelihood of therapeutic responses and medication dosing. Recognizing that 25% of patients have a subtherapeutic antiplatelet response to clopidogrel, researchers have identified several genetic variants affecting the metabolism of clopidogrel, a prodrug, to its active metabolite. Of these, the CYP2C19 variant allele has been best linked to impaired clopidogrel metabolism, reduced platelet inhibition and a higher risk of adverse cardiovascular events following percutaneous coronary interventions56. Based on the cumulative data, the FDA has now altered clopidogrel’s prescribing information based on CYP2C19 genotype, a move that foreshadows the development of companion diagnostic testing and alternative inhibitors of ADP-mediated platelet activation that do not require metabolism by CYP2C1956. In heart failure therapeutics, pharmacodynamic studies and posthoc analyses from clinical trials indicate that polymorphisms in the β1-adrenergic receptor affect the clinical actions of beta blockers57, 58, while more limited data suggest common variants that affect therapeutic response in heart failure59 and hyperlipidemia60–62.

Warfarin provides a particularly important example of a situation where pharmacogenomic considerations may affect drug dosing. Warfarin is a widely used oral anticoagulant with several important indications and significant risks associated with either underdosing or overdosing and great patient-to-patient variability in dosing. Though many clinical and environmental factors are known to affect warfarin dosing63, several studies have identified common sequence variants in at least two genes (CYP2C9 and VKORC1) that strongly affect the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of warfarin64–66. Small clinical trials suggest that that genetically-based warfarin dosing algorithms may enhance the efficiency and safety of warfarin dosing67, 68. Based on these proof-of-concept studies, a large multicenter randomized trial entitled Clarification of Optimal Anticoagulation through Genetics (COAG, clinicaltrials.gov ID: NCT00839657) is currently testing whether genotype-guided dosing to initiate warfarin therapy will improve the percentage of time within the therapeutic INR range (PTTR).

Identifying New Therapeutic Targets

One of the most promising applications for functional genomics is the use of unbiased, genome-wide screens to provide new insights into disease mechanism and identify new, often unexpected, therapeutic targets. In an early example, Chen et al performed a transcriptomic screen in human myocardium from heart failure patients before and after treatment with ventricular assist device therapy and identified the APJ receptor as markedly regulated cardiac gene69. This spawned further research demonstrating that the natural ligand for APJ, an inotropic neurohormone called apelin, is elevated in heart failure patients, and apelin is now under investigation as a heart failure therapy70. Other opportunities arise from combining different ‘omic’ datasets to study disease mechanism, an approach often referred to as ‘integrative genomics.’ For example, by combining whole-genome genotyping with whole-genome expression profiling in a tissues of interest, DNA variants that influence gene expression (expression quantitative trait loci, or ‘eQTLs’) can be identified71. Genome-wide eQTL mapping can be combined with network modeling to investigate how inherited DNA sequence variants alter gene expression networks to cause disease. Exploiting the relatively easy availability of human adipose tissue, these approaches have already revealed unexpected insights into human metabolic disorders33, 72 and provided a means of distinguishing primary causes of disease from secondary compensatory changes73. Applying similar integrative genomic approaches in animal models, Petretto and colleagues identified genomic loci that affect left ventricular gene expression and mass36. Among these, the extracellular matrix protein osteoglycin was found to upregulated by hypertrophic stimuli in laboratory models and to exhibit a blood pressure-independent association with left ventricular mass in human subjects. These studies demonstrate how novel discovery strategies, enabled by functional genomics, can help identify promising and unexpected therapeutic targets that may ultimately be relevant to clinical cardiologists.

Future Expectations

In view of substantial public and private investment in genome science, some feel that functional genomics has been slow in producing clinical advances74,75. To some extent this controversy is not surprising; the reality of any new scientific endeavor generally falls short of the initial hype and excitement. As outlined in the previous section, however, clinical applications are already impacting the practice of cardiovascular medicine and this trend will undoubtedly continue at a steady pace. Rather than make specific predictions, which are likely to be wrong, here we comment on two trends that are will continue to shape clinical applications in the near term.

Technology-Discovery Synergy

Functional genomics is a technology-dependent field where rapid advances in technology continue to propel new insights and new insights, in turn, demand advances in technology and bioinformatics. This is well-illustrated by an ongoing transition from microarray-based technologies to whole-genome DNA and RNA sequencing, which is shaping the next wave of functional genomics. The cost of whole genome sequencing by commercial entities has fallen from $100,000,000 in 200076 to $5,000, and the $1,000 genome is now a realistic near-term prospect77. Greater application of DNA sequencing has already shown that common genetic variants (those observed in more than 5 percent of the population) account for only a small portion of DNA sequence differences between individuals. This realization has begun to shift clinical diagnostics78 and linkage studies79 toward sequencing. Vast quantities of sequence information produced by these trends present substantial analytic challenges that underscore the vital need for parallel advances in bioninformatics and decision-support interfaces43,80. There is little doubt that this specific trend towards greater reliance on sequencing, and the general dynamic of technology-discovery synergy will continue during the next decade.

The Critical Role of Electronic Medical Records

Storage and organization of vast phenotypic data in electronic medical records (EMRs) provides a powerful opportunity for functional genomics research, and this trend will likely grow. For example, linkage of EMR phenotypes to genetic data derived from biobanks is already being spearheaded by the NIH-funded Pharmacogenomics Research Network (PGRN)81 and other consortia to identify genetic factors affecting drug efficacy and toxicity. For clinicians, it seems very likely that their patients will begin to have genome sequence information incorporated into their medical records. Using this information to improve care will require advances in EMR decision support80. Just as current EMR systems flag known allergies and relevant drug-drug interactions, future EMRs may flag and inform physicians about relevant genetic variants harbored by their patients that predict drug response or toxicity. Such systems will require continuous updates in view of new research findings to maximize clinical benefit.

In summary, advances in functional genomics will be increasingly important to practicing cardiovascular specialists in the coming decade and beyond. The reality will lag behind the hype, but in the long run genome information will have a transformative impact on cardiovascular research and practice.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

Supported by NIH grants R01HL088577, R21HL092379, R01HL089847, and the Penn Cardiovascular Institute.

Acknowledgements

None

Footnotes

Disclosures

Dr. Cappola reports patents pending on use of gene expression to diagnose cardiac allograft rejection.

References

- 1.Vukmirovic OG, Tilghman SM. Exploring genome space. Nature. 2000;405:820–822. doi: 10.1038/35015690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feero WG, Guttmacher AE, Collins FS. Genomic medicine -- an updated primer. N Eng J Med. 2010;362:2001–2011. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0907175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khoury MJ. Genetics and genomics in practice: the continuum from genetic disease to genetic information in health and disease. Genet Med. 2003;5:261–268. doi: 10.1097/01.GIM.0000076977.90682.A5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacRae CA. Genetics primer for the general cardiologist. Circulation. 2011;123:467. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guttmacher AE, Collins FS. Genomic medicine--a primer. N Eng J Med. 2002;347:1512–1520. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra012240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim L, Devereux RB, Basson CT. Impact of Genetic Insights Into Mendelian Disease on Cardiovascular Clinical Practice. Circulation. 2011;123:544–550. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.914804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hardy J, Singleton A. Genomewide association studies and human disease. N Eng J Med. 2009;360:1759–1768. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0808700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Musunuru K, Strong A, Frank-Kamenetsky M, Lee NE, Ahfeldt T, Sachs KV, Li X, Li H, Kuperwasser N, Ruda VM, Pirruccello JP, Muchmore B, Prokunina-Olsson L, Hall JL, Schadt EE, Morales CR, Lund-Katz S, Phillips MC, Wong J, Cantley W, Racie T, Ejebe KG, Orho-Melander M, Melander O, Koteliansky V, Fitzgerald K, Krauss RM, Cowan CA, Kathiresan S, Rader DJ. From noncoding variant to phenotype via SORT1 at the 1p13 cholesterol locus. Nature. 2010;466:714–719. doi: 10.1038/nature09266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cappola TP, Matkovich SJ, Wang W, van Booven D, Li M, Wang X, Qu L, Sweitzer NK, Fang JC, Reilly MP, Hakonarson H, Nerbonne JM, Dorn GW. Loss-of-function DNA sequence variant in the CLCNKA chloride channel implicates the cardio-renal axis in interindividual heart failure risk variation. PNAS. 2011;108:2456–2461. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017494108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McClellan J, King MC. Genetic heterogeneity in human disease. Cell. 2010;141:210–217. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ashley EA, Butte AJ, Wheeler MT, Chen R, Klein TE, Dewey FE, Dudley JT, Ormond KE, Pavlovic A, Morgan AA, Pushkarev D, Neff NF, Hudgins L, Gong L, Hodges LM, Berlin DS, Thorn CF, Sangkuhl K, Hebert JM, Woon M, Sagreiya H, Whaley R, Knowles JW, Chou MF, Thakuria JV, Rosenbaum AM, Zaranek AW, Church GM, Greely HT, Quake SR, Altman RB. Clinical assessment incorporating a personal genome. Lancet. 2010;375:1525–1535. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60452-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bird A. Perceptions of epigenetics. Nature. 2007;447:396–398. doi: 10.1038/nature05913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ordovas JM, Smith CE. Epigenetics and cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2010;7:510–519. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2010.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Margueron Rl, Reinberg D. Chromatin structure and the inheritance of epigenetic information. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:285–296. doi: 10.1038/nrg2752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baccarelli A, Rienstra M, Benjamin EJ. Cardiovascular Epigenetics. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2010;3:567–573. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.110.958744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trivedi CM, Luo Y, Yin Z, Zhang M, Zhu W, Wang T, Floss T, Goettlicher M, Noppinger PR, Wurst W, Ferrari VA, Abrams CS, Gruber PJ, Epstein JA. Hdac2 regulates the cardiac hypertrophic response by modulating Gsk3 beta activity. Nat Med. 2007;13:324–331. doi: 10.1038/nm1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Small EM, Frost RJ, Olson EN. MicroRNAs add a new dimension to cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2010;121:1022–1032. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.889048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dorn GW. Therapeutic potential of microRNAs in heart failure. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2010;12:209–215. doi: 10.1007/s11886-010-0096-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Souza AI, Cardin S, Wait R, Chung YL, Vijayakumar M, Maguy A, Camm AJ, Nattel S. Proteomic and metabolomic analysis of atrial profibrillatory remodelling in congestive heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;49:851–863. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lewis GD, Gerszten RE. Toward metabolomic signatures of cardiovascular disease. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2010;3:119–121. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.110.954941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mayr M. Metabolomics: ready for the prime time? Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2008;1:58–65. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.108.808329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goonewardena SN, Prevette LE, Desai AA. Metabolomics and atherosclerosis. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2010;12:267–272. doi: 10.1007/s11883-010-0112-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kontush A, Chapman MJ. Lipidomics as a tool for the study of lipoprotein metabolism. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2010;2:194–201. doi: 10.1007/s11883-010-0100-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee DS, Pencina MJ, Benjamin EJ, Wang TJ, Levy D, O’Donnell CJ, Nam BH, Larson MG, D’Agostino RB, Vasan RS. Association of parental heart failure with risk of heart failure in offspring. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:138–147. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith NL, Felix JF, Morrison AC, Demissie S, Glazer NL, Loehr LR, Cupples LA, Dehghan A, Lumley T, Rosamond WD, Lieb W, Rivadeneira F, Bis JC, Folsom AR, Benjamin E, Aulchenko YS, Haritunians T, Couper D, Murabito J, Wang YA, Stricker BH, Gottdiener JS, Chang PP, Wang TJ, Rice KM, Hofman A, Heckbert SR, Fox ER, O’Donnell CJ, Uitterlinden AG, Rotter JI, Willerson JT, Levy D, van Duijn CM, Psaty BM, Witteman JC, Boerwinkle E, Vasan RS. Association of genome-wide variation with the risk of incident heart failure in adults of European and African ancestry: a prospective meta-analysis from the cohorts for heart and aging research in genomic epidemiology (CHARGE) consortium. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2010;3:256–266. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.895763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vasan RS, Glazer NL, Felix JF, Lieb W, Wild PS, Felix SB, Watzinger N, Larson MG, Smith NL, Dehghan A, Grosshennig A, Schillert A, Teumer A, Schmidt R, Kathiresan S, Lumley T, Aulchenko YS, Konig IR, Zeller T, Homuth G, Struchalin M, Aragam J, Bis JC, Rivadeneira F, Erdmann J, Schnabel RB, Dorr M, Zweiker R, Lind L, Rodeheffer RJ, Greiser KH, Levy D, Haritunians T, Deckers JW, Stritzke J, Lackner KJ, Volker U, Ingelsson E, Kullo I, Haerting J, O’Donnell CJ, Heckbert SR, Stricker BH, Ziegler A, Reffelmann T, Redfield MM, Werdan K, Mitchell GF, Rice K, Arnett DK, Hofman A, Gottdiener JS, Uitterlinden AG, Meitinger T, Blettner M, Friedrich N, Wang TJ, Psaty BM, van Duijn CM, Wichmann HE, Munzel TF, Kroemer HK, Benjamin EJ, Rotter JI, Witteman JC, Schunkert H, Schmidt H, Volzke H, Blankenberg S. Genetic variants associated with cardiac structure and function: a meta-analysis and replication of genome-wide association data. JAMA. 2009;302:168–178. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.978-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cappola TP, Li M, He J, Ky B, Gilmore J, Qu L, Keating B, Reilly M, Kim CE, Glessner J, Frackelton E, Hakonarson H, Syed F, Hindes A, Matkovich SJ, Cresci S, Dorn GW., 2nd Common variants in HSPB7 and FRMD4B associated with advanced heart failure. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2010;3:147–154. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.898395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stark K, Esslinger UB, Reinhard W, Petrov G, Winkler T, Komajda M, Isnard R, Charron P, Villard E, Cambien F, Tiret L, Aumont MC, Dubourg O, Trochu JN, Fauchier L, Degroote P, Richter A, Maisch B, Wichter T, Zollbrecht C, Grassl M, Schunkert H, Linsel-Nitschke P, Erdmann J, Baumert J, Illig T, Klopp N, Wichmann HE, Meisinger C, Koenig W, Lichtner P, Meitinger T, Schillert A, Konig IR, Hetzer R, Heid IM, Regitz-Zagrosek V, Hengstenberg C. Genetic association study identifies HSPB7 as a risk gene for idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001167. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lanktree MB, Hassell RG, Lahiry P, Hegele RA. Phenomics: Expanding the Role of Clinical Evaluation in Genomic Studies. J Investig Med. 2010;58:700–706. doi: 10.231/JIM.0b013e3181d844f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hagen JB. The origins of bioinformatics. Nat Rev Genet. 2000;1:231–236. doi: 10.1038/35042090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kanehisa M, Bork P. Bioinformatics in the post-sequence era. Nat Genet. 2003;33 (Suppl):305–310. doi: 10.1038/ng1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barabasi AL, Gulbahce N, Loscalzo J. Network medicine: a network-based approach to human disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:56–68. doi: 10.1038/nrg2918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Emilsson V, Thorleifsson G, Zhang B, Leonardson AS, Zink F, Zhu J, Carlson S, Helgason A, Walters GB, Gunnarsdottir S, Mouy M, Steinthorsdottir V, Eiriksdottir GH, Bjornsdottir G, Reynisdottir I, Gudbjartsson D, Helgadottir A, Jonasdottir A, Jonasdottir A, Styrkarsdottir U, Gretarsdottir S, Magnusson KP, Stefansson H, Fossdal R, Kristjansson K, Gislason HG, Stefansson T, Leifsson BG, Thorsteinsdottir U, Lamb JR, Gulcher JR, Reitman ML, Kong A, Schadt EE, Stefansson K. Genetics of gene expression and its effect on disease. Nature. 2008;452:423–428. doi: 10.1038/nature06758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schadt EE, Molony C, Chudin E, Hao K, Yang X, Lum PY, Kasarskis A, Zhang B, Wang S, Suver C, Zhu J, Millstein J, Sieberts S, Lamb J, GuhaThakurta D, Derry J, Storey JD, Avila-Campillo I, Kruger MJ, Johnson JM, Rohl CA, van Nas A, Mehrabian M, Drake TA, Lusis AJ, Smith RC, Guengerich FP, Strom SC, Schuetz E, Rushmore TH, Ulrich R. Mapping the genetic architecture of gene expression in human liver. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e107. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schadt EE, Zhang B, Zhu J. Advances in systems biology are enhancing our understanding of disease and moving us closer to novel disease treatments. Genetica. 2009;136:259–269. doi: 10.1007/s10709-009-9359-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Petretto E, Sarwar R, Grieve I, Lu H, Kumaran MK, Muckett PJ, Mangion J, Schroen B, Benson M, Punjabi PP, Prasad SK, Pennell DJ, Kiesewetter C, Tasheva ES, Corpuz LM, Webb MD, Conrad GW, Kurtz TW, Kren V, Fischer J, Hubner N, Pinto YM, Pravenec M, Aitman TJ, Cook SA. Integrated genomic approaches implicate osteoglycin (Ogn) in the regulation of left ventricular mass. Nat Genet. 2008;40(5):546–552. doi: 10.1038/ng.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petretto E, Bottolo L, Langley SR, Heinig M, McDermott-Roe C, Sarwar R, Pravenec M, Hubner N, Aitman TJ, Cook SA, Richardson S. New insights into the genetic control of gene expression using a Bayesian multi-tissue approach. PLoS Comput Biol. 2010;6:e1000737. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lusis AJ, Weiss JN. Cardiovascular networks: systems-based approaches to cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2010;121:157–170. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.847699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Musunuru K, Kathiresan S. Genetics of Coronary Artery Disease. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2010;11:91–108. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-082509-141637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paynter NP, Chasman DI, Paré G, Buring JE, Cook NR, Miletich JP, Ridker PM. Association Between a Literature-Based Genetic Risk Score and Cardiovascular Events in Women. JAMA. 2010;303:631–637. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ripatti S, Tikkanen E, Orho-Melander M, Havulinna AS, Silander K, Sharma A, Guiducci C, Perola M, Jula A, Sinisalo J, Lokki M-L, Nieminen MS, Melander O, Salomaa V, Peltonen L, Kathiresan S. A multilocus genetic risk score for coronary heart disease: case-control and prospective cohort analyses. Lancet. 2010;376:1393–1400. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61267-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thanassoulis G, Vasan RS. Genetic Cardiovascular Risk Prediction: Will We Get There? Circulation. 2010;122:2323–2334. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.909309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ormond KE, Wheeler MT, Hudgins L, Klein TE, Butte AJ, Altman RB, Ashley EA, Greely HT. Challenges in the clinical application of whole-genome sequencing. Lancet. 2010;375:1749–1751. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60599-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Horwitz PA, Tsai EJ, Putt ME, Gilmore JM, Lepore JJ, Parmacek MS, Kao AC, Desai SS, Goldberg LR, Brozena SC, Jessup ML, Epstein JA, Cappola TP. Detection of cardiac allograft rejection and response to immunosuppressive therapy with peripheral blood gene expression. Circulation. 2004;110:3815–3821. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000150539.72783.BF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Deng MC, Eisen HJ, Mehra MR, Billingham M, Marboe CC, Berry G, Kobashigawa J, Johnson FL, Starling RC, Murali S, Pauly DF, Baron H, Wohlgemuth JG, Woodward RN, Klingler TM, Walther D, Lal PG, Rosenberg S, Hunt S. Noninvasive discrimination of rejection in cardiac allograft recipients using gene expression profiling. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:150–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pham MX, Teuteberg JJ, Kfoury AG, Starling RC, Deng MC, Cappola TP, Kao A, Anderson AS, Cotts WG, Ewald GA, Baran DA, Bogaev RC, Elashoff B, Baron H, Yee J, Valantine HA. Gene-expression profiling for rejection surveillance after cardiac transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1890–1900. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rosenberg S, Elashoff MR, Beineke P, Daniels SE, Wingrove JA, Tingley WG, Sager PT, Sehnert AJ, Yau M, Kraus WE, Newby LK, Schwartz RS, Voros S, Ellis SG, Tahirkheli N, Waksman R, McPherson J, Lansky A, Winn ME, Schork NJ, Topol EJ. Multicenter validation of the diagnostic accuracy of a blood-based gene expression test for assessing obstructive coronary artery disease in nondiabetic patients. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:425–434. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-7-201010050-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morrow DA, Braunwald E. Future of biomarkers in acute coronary syndromes: moving toward a multimarker strategy. Circulation. 2003;108:250–252. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000078080.37974.D2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barderas MG, Laborde CM, Posada M, de la Cuesta F, Zubiri I, Vivanco F, Alvarez-Llamas G. Metabolomic profiling for identification of novel potential biomarkers in cardiovascular diseases. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011:790132. doi: 10.1155/2011/790132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alexander D, Lombardi R, Rodriguez G, Mitchell MM, Marian AJ. Metabolomic distinction and insights into the pathogenesis of human primary dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur J Clin Invest. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1365–2362.2010.02441.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goetz MP, Knox SK, Suman VJ, Rae JM, Safgren SL, Ames MM, Visscher DW, Reynolds C, Couch FJ, Lingle WL, Weinshilboum RM, Fritcher EG, Nibbe AM, Desta Z, Nguyen A, Flockhart DA, Perez EA, Ingle JN. The impact of cytochrome P450 2D6 metabolism in women receiving adjuvant tamoxifen. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;101:113–121. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9428-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Eberhard DA, Johnson BE, Amler LC, Goddard AD, Heldens SL, Herbst RS, Ince WL, Janne PA, Januario T, Johnson DH, Klein P, Miller VA, Ostland MA, Ramies DA, Sebisanovic D, Stinson JA, Zhang YR, Seshagiri S, Hillan KJ. Mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor and in KRAS are predictive and prognostic indicators in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer treated with chemotherapy alone and in combination with erlotinib. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5900–5909. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lievre A, Bachet JB, Boige V, Cayre A, Le Corre D, Buc E, Ychou M, Bouche O, Landi B, Louvet C, Andre T, Bibeau F, Diebold MD, Rougier P, Ducreux M, Tomasic G, Emile JF, Penault-Llorca F, Laurent-Puig P. KRAS mutations as an independent prognostic factor in patients with advanced colorectal cancer treated with cetuximab. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:374–379. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.5906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Di Fiore F, Blanchard F, Charbonnier F, Le Pessot F, Lamy A, Galais MP, Bastit L, Killian A, Sesboue R, Tuech JJ, Queuniet AM, Paillot B, Sabourin JC, Michot F, Michel P, Frebourg T. Clinical relevance of KRAS mutation detection in metastatic colorectal cancer treated by Cetuximab plus chemotherapy. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:1166–1169. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hoskins JM, Goldberg RM, Qu P, Ibrahim JG, McLeod HL. UGT1A1*28 genotype and irinotecan-induced neutropenia: dose matters. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1290–1295. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ellis KJ, Stouffer GA, McLeod HL, Lee CR. Clopidogrel pharmacogenomics and risk of inadequate platelet inhibition: US FDA recommendations. Pharmacogenomics. 2009;10:1799–1817. doi: 10.2217/pgs.09.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mialet Perez J, Rathz DA, Petrashevskaya NN, Hahn HS, Wagoner LE, Schwartz A, Dorn GW, Liggett SB. Beta 1-adrenergic receptor polymorphisms confer differential function and predisposition to heart failure. Nat Med. 2003;9:1300–1305. doi: 10.1038/nm930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liggett SB, Mialet-Perez J, Thaneemit-Chen S, Weber SA, Greene SM, Hodne D, Nelson B, Morrison J, Domanski MJ, Wagoner LE, Abraham WT, Anderson JL, Carlquist JF, Krause-Steinrauf HJ, Lazzeroni LC, Port JD, Lavori PW, Bristow MR. A polymorphism within a conserved beta(1)-adrenergic receptor motif alters cardiac function and beta-blocker response in human heart failure. PNAS. 2006;103:11288–11293. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509937103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McNamara DM. Emerging role of pharmacogenomics in heart failure. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2008;23:261–268. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e3282fcd662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barber MJ, Mangravite LM, Hyde CL, Chasman DI, Smith JD, McCarty CA, Li X, Wilke RA, Rieder MJ, Williams PT, Ridker PM, Chatterjee A, Rotter JI, Nickerson DA, Stephens M, Krauss RM. Genome-wide association of lipid-lowering response to statins in combined study populations. PloS One. 2010;5:e9763. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bailey KM, Romaine SP, Jackson BM, Farrin AJ, Efthymiou M, Barth JH, Copeland J, McCormack T, Whitehead A, Flather MD, Samani NJ, Nixon J, Hall AS, Balmforth AJ. Hepatic metabolism and transporter gene variants enhance response to rosuvastatin in patients with acute myocardial infarction: the GEOSTAT-1 Study. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2010;3:276–285. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.898502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hubacek JA, Adamkova V, Prusikova M, Snejdrlova M, Hirschfeldova K, Lanska V, Ceska R, Vrablik M. Impact of apolipoprotein A5 variants on statin treatment efficacy. Pharmacogenomics. 2009;10:945–950. doi: 10.2217/pgs.09.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ansell JE. Optimizing the efficacy and safety of oral anticoagulant therapy: high-quality dose management, anticoagulation clinics, and patient self-management. Semin Vasc Med. 2003;3:261–270. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-44462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Higashi MK, Veenstra DL, Kondo LM, Wittkowsky AK, Srinouanprachanh SL, Farin FM, Rettie AE. Association between CYP2C9 genetic variants and anticoagulation-related outcomes during warfarin therapy. JAMA. 2002;287:1690–1698. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.13.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rieder MJ, Reiner AP, Gage BF, Nickerson DA, Eby CS, McLeod HL, Blough DK, Thummel KE, Veenstra DL, Rettie AE. Effect of VKORC1 haplotypes on transcriptional regulation and warfarin dose. N Eng J Med. 2005;352:2285–2293. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sconce EA, Khan TI, Wynne HA, Avery P, Monkhouse L, King BP, Wood P, Kesteven P, Daly AK, Kamali F. The impact of CYP2C9 and VKORC1 genetic polymorphism and patient characteristics upon warfarin dose requirements: proposal for a new dosing regimen. Blood. 2005;106:2329–2333. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Anderson JL, Horne BD, Stevens SM, Grove AS, Barton S, Nicholas ZP, Kahn SF, May HT, Samuelson KM, Muhlestein JB, Carlquist JF. Randomized trial of genotype-guided versus standard warfarin dosing in patients initiating oral anticoagulation. Circulation. 2007;116:2563–2570. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.737312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Caraco Y, Blotnick S, Muszkat M. CYP2C9 genotype-guided warfarin prescribing enhances the efficacy and safety of anticoagulation: a prospective randomized controlled study. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;83:460–470. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen MM, Ashley EA, Deng DX, Tsalenko A, Deng A, Tabibiazar R, Ben-Dor A, Fenster B, Yang E, King JY, Fowler M, Robbins R, Johnson FL, Bruhn L, McDonagh T, Dargie H, Yakhini Z, Tsao PS, Quertermous T. Novel role for the potent endogenous inotrope apelin in human cardiac dysfunction. Circulation. 2003;108:1432–1439. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000091235.94914.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Japp AG, Cruden NL, Barnes G, van Gemeren N, Mathews J, Adamson J, Johnston NR, Denvir MA, Megson IL, Flapan AD, Newby DE. Acute cardiovascular effects of apelin in humans: potential role in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2010;121:1818–1827. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.911339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sarwar R, Cook SA. Genomic analysis of left ventricular remodeling. Circulation. 2009;120:437–444. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.797225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chen Y, Zhu J, Lum PY, Yang X, Pinto S, MacNeil DJ, Zhang C, Lamb J, Edwards S, Sieberts SK, Leonardson A, Castellini LW, Wang S, Champy MF, Zhang B, Emilsson V, Doss S, Ghazalpour A, Horvath S, Drake TA, Lusis AJ, Schadt EE. Variations in DNA elucidate molecular networks that cause disease. Nature. 2008;452:429–435. doi: 10.1038/nature06757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhu J, Wiener MC, Zhang C, Fridman A, Minch E, Lum PY, Sachs JR, Schadt EE. Increasing the power to detect causal associations by combining genotypic and expression data in segregating populations. PLoS Comput Biol. 2007;3:e69. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.The human genome at ten. Nature. 2010;464:649–650. doi: 10.1038/464649a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wade NA. A decade later, genetic map yields few new cures. The New York Times; 2010. Jun 12, p. A1. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Levy S, Sutton G, Ng PC, Feuk L, Halpern AL, Walenz BP, Axelrod N, Huang J, Kirkness EF, Denisov G, Lin Y, MacDonald JR, Pang AW, Shago M, Stockwell TB, Tsiamouri A, Bafna V, Bansal V, Kravitz SA, Busam DA, Beeson KY, McIntosh TC, Remington KA, Abril JF, Gill J, Borman J, Rogers YH, Frazier ME, Scherer SW, Strausberg RL, Venter JC. The diploid genome sequence of an individual human. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jackson L, Pyeritz RE. Molecular technologies open new clinical genetic vistas. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:65ps62. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bell CJ, Dinwiddie DL, Miller NA, Hateley SL, Ganusova EE, Mudge J, Langley RJ, Zhang L, Lee CC, Schilkey FD, Sheth V, Woodward JE, Peckham HE, Schroth GP, Kim RW, Kingsmore SF. Carrier testing for severe childhood recessive diseases by next-generation sequencing. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:65ra64. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Musunuru K, Pirruccello JP, Do R, Peloso GM, Guiducci C, Sougnez C, Garimella KV, Fisher S, Abreu J, Barry AJ, Fennell T, Banks E, Ambrogio L, Cibulskis K, Kernytsky A, Gonzalez E, Rudzicz N, Engert JC, DePristo MA, Daly MJ, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH, Altshuler D, Schonfeld G, Gabriel SB, Yue P, Kathiresan S. Exome sequencing, ANGPTL3 mutations, and familial combined hypolipidemia. N Eng J Med. 2010;363:2220–2227. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wilke RA, Xu H, Denny JC, Roden DM, Krauss RM, McCarty CA, Davis RL, Skaar T, Lamba J, Savova G. The Emerging Role of Electronic Medical Records in Pharmacogenomics. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89:379–86. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Relling MV, Klein TE. CPIC: Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium of the Pharmacogenomics Research Network. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89:387–91. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]