Abstract

The 26 S proteasome possesses two distinct deubiquitinating activities. The ubiquitin (Ub) chain amputation activity removes the entire polyUb chain from the substrates. The Ub chain trimming activity progressively cleaves a polyUb chain from the distal end. The Ub chain amputation activity mediates degradation-coupled deubiquitination. The Ub chain trimming activity can play a supportive or an inhibitory role in degradation, likely depending on features of the substrates. How Ub chain trimming assists degradation is not clear. We find that inhibition of the chain trimming activity of the 26 S proteasome with Ub aldehyde significantly inhibits degradation of Ub4 (Lys-48)-UbcH10 and causes accumulation of free Ub4 (generated from chain amputation) that can be retained on the proteasome. Also, a non-trimmable Lys-48-mimic Ub4 efficiently targets UbcH10 to the 26 S proteasome, but it cannot support efficient degradation of UbcH10 compared with regular Lys-48 Ub4. These results indicate that polyUb chain trimming promotes proteasomal degradation of Lys-48-linked substrates. Mechanistically, we propose that Ub chain trimming cleaves the proteasome-bound Lys-48-linked polyUb chains, which vacates the Ub binding sites of the 26 S proteasome, thus allowing continuous substrate loading.

Keywords: Deubiquitination, Proteasome, Protein Degradation, Ubiquitin, Ubiquitination

Introduction

The Ub-proteasome4 pathway plays essential roles in regulating almost every cellular event, including gene transcription, signal transduction, and DNA repair (1, 2). Ub is a 76-amino acid protein that can be covalently conjugated onto proteins, mostly on lysine residues, as a monomer or a polyUb chain. Protein ubiquitination is carried out by a cascade of enzymatic reactions, including a Ub-activating enzyme E1, a Ub-conjugating enzyme E2, and a Ub ligase E3. The 26 S proteasome is a ∼2.5-MDa-large complex comprised of the 19 S regulatory complex (called PA700 in mammals) and the 20 S proteasome. PA700 has at least 19 subunits that have multiple activities, including gate opening of the 20 S proteasome, recruiting substrates to the proteasome, and processing substrates ready for degradation. The six AAA ATPase subunits of the PA700 form a ring abutting on either or both ends of the 20 S proteasome to form the 26 S proteasome (3).

Interestingly, Ub is recycled during proteolysis, which is spared from the 26 S proteasome by the proteasome-residing deubiquitinating enzymes. The mammalian 26 S proteasome possesses two distinct deubiquitinating activities: the S13/Rpn11 subunit catalyzes chain amputation activity which cleaves the entire polyUb chain directly from the substrates (4). S13/Rpn11 is a Zn2+-dependent metalloprotease (4, 5). Its deubiquitinating activity is activated when assembled into the 26 S proteasome, and it is highly conserved in all eukaryotic proteasomes. It was found that the polyUb chain amputation activity is necessary to mediate degradation-coupled deubiquitination (4, 5), likely by clearing the steric restriction of polyUb chains that otherwise could impede the substrate to enter the narrow substrate delivery channel of the 26 S proteasome. Moreover, when coupled with degradation, chain amputation is ATP hydrolysis-dependent. In addition to the chain amputation activity, the 26 S proteasome has a polyUb chain trimming activity, which progressively shortens a polyUb chain from the distal site (6, 7). Uch37 and Usp14 are the two deubiquitinating enzymes that have chain trimming activity in mammalian 26 S proteasomes (6, 7). The mechanisms by which they perform Ub chain trimming are not fully understood. The chain trimming enzymes are not well conserved among eukaryotes, as budding yeast lacks a homologue of Uch37 but has a Usp14 homologue, Ubp6 (8, 9). Also, Usp14/Ubp6 is a proteasome-associating enzyme. Its residence on the 26 S proteasome is highly salt concentration-sensitive (9, 10). Currently, the Ub chain trimming was found to have double-edged effects on degradation. It was originally suggested that the chain trimming activity serves as a safeguard to rescue poorly ubiquitinated proteins from the proteasome by editing the conjugates (6). We recently found that Lys-63 polyUb chains are highly susceptible to chain trimming, which renders Lys-63-linked polyUb conjugates to be rapidly deubiquitinated by the 26 S proteasome without efficient degradation (11). Thus, Ub chain trimming could rescue Lys-63-linked substrates from proteasomal degradation. Consistent with this, Ubp6 and Usp14 were recently found to play a negative role in mediating proteolysis (12). On the other hand, Ub chain trimming was also found to play a positive role in mediating degradation. In yeast cells, depletion of Ubp6 impairs degradation of some proteasomal substrates, including Ub-Pro-β-galactosidase (9). In mammalian cells, RNAi-mediated knockdown of Uch37, Usp14, Adrm1 (the Uch37 activator (13–15)), or their combinations were found to impair proteasomal degradation in cells, at least for those examined substrates (10, 13, 16). Moreover, inhibition of the chain trimming activity abolishes efficient degradation of some Lys-48-linked polyubiquitinated proteins in in vitro reconstituted degradation assays (17). The discrepancies in these studies might reflect the versatility of the chain trimming activity in mediating protein degradation in the context of specific features of the substrates, such as different Ub chain linkages and substrate stabilities (see “Discussion”).

PolyUb chains can be linked through the internal Lys-6, Lys-11, Lys-27, Lys-29, Lys-33, Lys-48, or Lys-63, or through the α-amino group. Recent proteomic studies showed that all lysine-orientated polyUb linkages except Lys-63 could serve as proteolytic signals (11, 18). Lys-48-linked polyUb chains are one of the primary linkages that target proteins for proteolysis. Previous studies have shown that the chain trimming activity supports degradation of Lys-48-linked substrates (17, 18). However, the underlying mechanism is not clear. One hypothesis for explaining how the chain trimming activity can support degradation is that chain trimming cleaves polyUb chains into short forms that have low proteasomal binding affinity, by which it may vacate the Ub binding sites of the proteasome for the next round of substrate loading. In this study, we performed biochemical experiments using an in vitro reconstitution system to test this hypothesis.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

Antibodies were purchased against the following proteins: UbcH10 (Boston Biochem), Ub (P4D1), Myc (9E10), and Cdc27 (AF3.1) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Rabbit antibody against the s7 subunit of the proteasome was a gift from Dr. G. N. DeMartino (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center). Ubal (Enzo Life) was prepared in a small volume of 20 mm Tris (pH 7.6) with 3 m urea to break possible aggregates and then diluted with 20 mm Tris (pH 7.6) to a final concentration of 100 μm Ubal with 0.5 m urea and stored at −80 °C.

Synthesis of PolyUb Chains

Lys-48 Ub4 was synthesized according to a previously reported method using yeast Ub variants (19). For synthesis of chemically cross-linked non-trimmable (NT) Ub4, we used E225K to catalyze the ligation of NT Lys-48Ub2 and Gly-76Ub2. NT Lys-48Ub2 was synthesized according to a method established in Dr. Wilkinson's group with minor changes (20, 21). Briefly, 100 mg of UbG76C (which donates Lys-48 for NT Ub4 synthesis) was reacted with 1.2× molar amounts of 1,3-dichloroacetone on ice for 30 min. Then 100 mg of UbK48C,Asp-77 was added for another 1-h incubation. 50 mm 2-Mercaptoethanol (βME) was then added into the reaction mixture to inactivate 1,3-dichloroacetone and break disulfide bonds. After a 30-min incubation, the reaction mixtures were then acidified to pH 5.2 using 2N acetic acid. The mixtures contained unreacted Ub monomers and three Ub2 forms (UbG76C-UbG76C, UbG76C-UbK48C,Asp-77, and UbK48C,Asp-77-UbK48C,Asp-77) by inter- or intra-Ub cross-linking. On the basis of their charge differences under acidic pH, these Ub2 were separated by an 8-ml SP-Sepharose column on an FPLC system using 0–300 mm NaCl gradient in 20 mm ammonium acetate (pH 5.2). UbG76C-UbK48C,Asp-77 (denoted as Lys-48Ub2) was eluted in the middle peak of the Ub2 fractions. Fractions containing pure Lys-48Ub2 were pooled and dialyzed against 20 mm NH4HCO3 and then lyophilized. Mass spectroscopic analysis confirmed that the pooled fractions predominantly contained Lys-48Ub2 with small amounts of monoUb. A similar method was used to synthesize NT Gly-76Ub2 (UbK48C-UbK48R,G76C) using the UbK48C and UbK48R,G76C variants, in which UbK48C donates the C-terminal Gly-76 for NT Ub4 synthesis. For NT Ub4 synthesis, the reaction contained 100 nm human E1, 20 μm GST-E225K, 2 mg/ml Lys-48Ub2, 2 mg/ml Gly-76Ub2 in 50 mm Tris (pH 8.0), 5 mm MgCl2, 4 mm ATP, and 1 mm βME. After overnight incubation at 30 °C, E1 and GST-E225K were bound to 1 ml Q-Sepharose resin. The Q-Sepharose resin was then removed by a 10-ml open column, and NT Ub4 was present in the flowthrough. 20 μg/ml YUH1 was then added into the flowthrough for 1-h incubation at 37 °C to remove the Asp-77 residue in the NT Ub4, which activates the only available Gly-76 residue in the NT Ub4 and enables it to be conjugated to substrates. YUH1 was then removed by 0.5 ml of Q-Sepharose resin. NT Ub4 in the unbound fraction was further purified on an 8-ml SP column at pH 5.2 using a gradient from 0–380 mm NaCl. All purified polyUb chains were dialyzed into 20 mm NH4HCO3 and lyophilized. If necessary, redissolved polyUb chains were further purified by a Superdex 75 gel filtration column (120 ml) on an FPLC system. The purity of the final Lys-48 Ub4 or NT Ub4 was > 85%, as judged by Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE.

Proteasomal Degradation Assay

The bovine 26 S proteasome and PA700 were purified according to previously established methods (17, 22). Conjugation of Ub4 onto UbcH10 and myc-cyclin B11-102, as well as in vitro proteasomal degradation, were performed according to our published methods (11, 17).

Size-exclusion Spin Column Assay

13.5 nm doubly capped 26 S proteasome was preincubated with 2.5 μm Ubal and 5 mm 1,10-phenanthroline for 10 min at 30 °C in proteasomal degradation buffer as indicated above. 80 nm K48 Ub4 or NT Ub4 was then mixed with the preinhibited proteasomes and incubated for 2 min at room temperature. 60 μl of mixtures or Ub4 alone was loaded into Micro Bio-Spin P-30 chromatography columns (Bio-Rad) and centrifuged according to the manufacturer's instructions. The flowthrough was eluted directly into a 1.5-ml microtube with 20 μl of 5× SDS sample buffer. 30 μl of samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE for immunoblotting assays. To determine the interaction between the 26 S proteasome (13.5 nm) and Ub4 (Lys-48 or NT)-UbcH10 (100 nm), we used homemade Sephadex G-100 spin columns (exclusion limit is 80 kDa). After centrifugation, all resulting mixtures (75 μl) were concentrated to ∼30 μl by heating and then loaded for separation by SDS-PAGE for immunoblotting of UbcH10.

RESULTS

Inhibition of the Chain Trimming Activity Causes Inefficient Degradation and Accumulation of Free PolyUb Chains

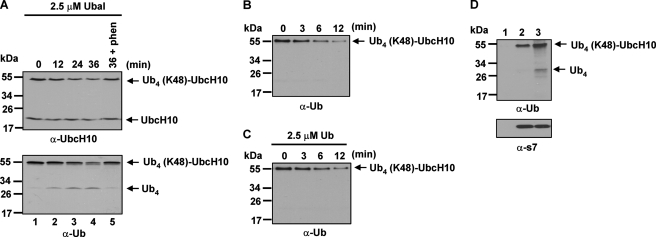

We have previously established an in vitro system to assess proteasomal degradation using purified bovine 26 S proteasomes and synthesized Ub4 (Lys-48)-UbcH10 as the substrate (17). This valuable reconstitution system has been utilized for elucidating the roles of ATP hydrolysis (17), substrate recognition (23), and deubiquitination (11) in proteolysis. We previously found that degradation of Ub4 (Lys-48)-UbcH10 by purified bovine 26 S proteasomes was significantly blocked by deubiquitinase inhibitors: Ubal (inhibiting the chain trimming activity) or 1,10-phenanthroline (inhibiting the chain amputation activity) (17). Ubal and 1,10-phenanthroline inhibit thio-proteases and the Rpn11 metalloprotease in the 26 S proteasome, respectively. Here, we further explored the inhibitory effect of Ubal on proteasomal degradation. As shown in Fig. 1, A and B, degradation of Ub4 (Lys-48)-UbcH10 occurred at a much slower rate when Ubal was added in the reaction mixtures. This inhibitory effect is likely not caused by blocking the substrate binding to the 26 S proteasome because we have shown that neither Ubal nor 1,10-phenanthroline prevents Ub4 (Lys-48)-UbcH10 binding the 26 S proteasome (11). Interestingly, immunoblotting of Ub showed that accumulation of Ub4 was obvious in reactions with Ubal (Fig. 1A, lower panel). In contrast, no free Ub4 was detected in reactions without Ubal treatment (Fig. 1B), in which the substrate was more rapidly degraded despite the 26 S proteasome concentration being only one half of that added in the reaction A. Not surprisingly, slow degradation of Lys-48 Ub4-UbcH10 in the presence of Ubal was further blocked when the chain amputation activity was inhibited by 1,10-phenanthroline (Fig. 1A, lane 5). These results indicate that the slow degradation of Ub4 (Lys-48)-UbcH10 in the presence of Ubal is mediated by the chain amputation activity. Of note, a portion of Ub4 chain could be degraded together with UbcH10 when the chain trimming activity was inhibited by Ubal because impairment of the chain trimming activity has been previously shown to cause Ub degradation (9).

FIGURE 1.

Inhibition of the chain trimming activity abolishes efficient proteasomal degradation and causes accumulation of free polyUb chain. A, Ubal treatment inhibits proteasomal degradation of Ub4 (Lys-48)-UbcH10 and causes accumulation of Ub4. Reactions contained 28 nm 26 S proteasomes and 100 nm Ub4 (Lys-48)-UbcH10. The 26 S proteasome was preincubated with 2.5 μm Ubal prior to being used for the assay. The proteasome was preincubated with 2.5 μm Ubal plus 5 mm 1, 10-phenanthroline (phen) prior to the supplementation of Ub4 (Lys-48)-UbcH10. B, efficient degradation of Ub4 (Lys-48)-UbcH10 does not cause accumulation of free Ub chains. Reactions contained 13.5 nm 26 S proteasomes and 100 nm Ub4 (Lys-48)-UbcH10. C, monoUb does not inhibit proteasomal degradation of Ub4 (Lys-48)-UbcH10. The reactions are analogous to that in B, except that the proteasome was preincubated with 2.5 μm Ub for 5 min prior to the supplementation of the substrate. D, Ub4 generated from Ubal-treated degradation reactions binds the 26 S proteasome together with the substrate. Ub4 + Ub4 (Lys-48)-UbcH10 (lane 1), mixtures of the 12-min reaction in B (lane 2), or mixtures of the 36-min reaction in A (lane 3) were applied for the size-exclusion spin column assay using Sephadex G-100 resin as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The flowthrough was immunoblotted with an anti-Ub or an anti-s7 (a proteasome subunit) antibody.

We next sought to determine whether the degradation inhibitory effect of Ubal is attributed to the Ub moiety, which could bind to the 26 S proteasome subunit Adrm1 (24–26). We performed the degradation assay by addition of monoUb. Compared with the reaction shown in Fig. 1B, the presence of monoUb had no effect on degradation of Ub4 (Lys-48)-UbcH10 (C). This result suggests that the degradation inhibitory effect of Ubal is likely due to inhibition of the chain trimming activity. Next, we attempted to identify deubiquitinating enzymes of the 26 S proteasome that can be modified with Ubal. We used HA-tagged Ub vinyl sulfone to covalently modify the catalytic cysteine residue of the potential deubiquitinating enzymes. After incubating HA-Ub-vinyl sulfone with the 26 S proteasome, proteins were denatured with 6 m urea and resolved in SDS-PAGE. Two subunits with molecular weights corresponding to Uch37 and Usp14 were predominately modified with HA-Ub-vinyl sulfone, as revealed by immunoblotting of HA (supplemental Fig. S1A). Modification of Uch37 and Usp14 were further verified by immunoblotting with an anti-Uch37 or anti-Usp14 antibody (supplemental Fig. S1, B and C). Therefore, Ubal modifies both chain trimming enzymes of the 26 S proteasome.

Ubal Treatment Causes Free Ub Chains Generated from Chain Amputation to be Retained on the 26 S Proteasome

S5a and Adrm1 are the primary Ub receptors of the 26 S proteasome (24, 25, 27, 28). S5a binds polyUb chains with high affinity, whereas Adrm1 binds both monoUb and polyUb chains (24). Interestingly, efficient degradation of UbcH10 requires both a polyUb chain modification and its N-terminal unstructured region to bind the 26 S proteasome (23). One possible interpretation for the requirement of two binding elements is that the high binding affinity of a polyUb chain targets the substrate to the 26 S proteasome, whereas a weaker interaction between an unstructured region in the substrate and the proteasome, presumably on the ATPase subunit(s), engages the substrate to the ATPase ring for unfolding and translocation. Apparently, blocking substrate binding can inhibit proteasomal degradation, which likely accounts for the degradation inhibitory effect of free polyUb chains (29, 30). If the free Ub4 accumulated in degradation reactions containing Ubal is retained on the 26 S proteasome, it could inhibit degradation. To test this, we employed size-exclusion spin column assays to examine whether free Ub4 generated in degradation reactions with Ubal treatment binds the 26 S proteasome. As shown in Fig. 1D (lane 1), Ub4 and Ub4 (Lys-48)-UbcH10 alone were absent in the flowthrough after passing through a Sephadex G-100 (80 kDa exclusion limit) spin column, indicating that they were trapped in the resin. When degradation mixtures from a 12-min reaction without Ubal treatment (Fig. 1D, lane 2) or from a 36-min reaction with Ubal treatment (lane 3) were applied to the spin column assay, Ub4 (Lys-48)-UbcH10 was detected in the flowthrough, indicating that it binds the 26 S proteasome. Moreover, free Ub4 was found to coelute with the 26 S proteasome together with the substrate in the reaction with Ubal treatment (Fig. 1D, lane 3). Thus, when Ub chain trimming is inhibited, free polyUb chain generated from chain amputation can remain on the 26 S proteasome.

Synthesis of a Lys-48-mimic Ub4 That Is Resistant to Chain Trimming by the 26 S Proteasome

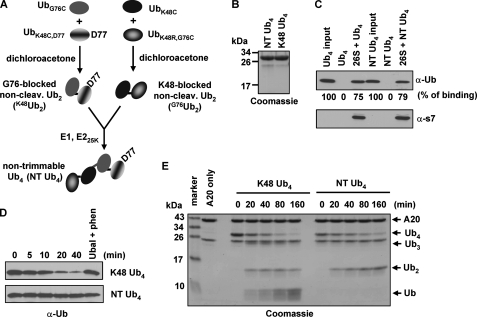

If timely recycling of the Ub binding sites of the 26 S proteasome is necessary to promote degradation of Lys-48-linked polyUb conjugates, we would predict that a Lys-48-mimic polyUb chain resistant to chain trimming would inhibit protein degradation. To test this, we synthesized a Lys-48-mimic Ub4 in which both the proximal and the distal Lys-48-Gly-76 linkages in each Ub2 moiety were chemically cross-linked using cysteine mutants (Fig. 2A), according to a previously established method (20, 21). Ub4 was then formed by enzymatically conjugating the two cross-linked Ub2 chains with an authentic Lys-48-linked isopeptide bond (Fig. 2, A and B). Of note, the linkages in the cross-linked Ub dimers are one atom longer than the authentic Lys-48-linked isopeptide. Other than that, the polarity of the linkage is largely maintained (20). With the purified Lys-48-mimic Ub4, we first examined if it binds the 26 S proteasome. As shown in Fig. 2C, the size exclusion spin column assay revealed that similar amounts of Lys-48 Ub4 and chemically cross-linked Ub4 were detected in the flowthrough with the 26 S proteasome after centrifugation, indicating that they have comparable binding to the 26 S proteasome. Thus, the chemically cross-linked bonds do not interfere with proteasomal binding. Next, we examined if the chemically cross-linked proximal and distal bonds in this Ub4 are resistant to proteasome-mediated deubiquitination. As assayed with immunoblotting and Coomassie-staining, cross-linked Ub4 was resistant to deubiquitination by purified 26 S proteasomes even in a four-hour incubation (Fig. 2D and supplemental Fig. S2). In contrast, regular Lys-48 Ub4 was rapidly deubiquitinated (Fig. 2D). Thereafter, we referred the cross-linked Ub4 as non-trimmable (NT) Ub4.

FIGURE 2.

Synthesis of NT Ub4 mimicking the regular Lys-48-linked counterpart. A, scheme of synthesis of NT Lys-48-mimic Ub4 (see “Experimental Procedures”). B, Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE of 6 μg of purified regular Lys-48 Ub4 or NT Ub4. C, NT Ub4 efficiently binds purified 26 S proteasome, comparable with Lys-48 Ub4, as examined with the size-exclusion spin column assay. D, NT Ub4 is resistant to the 26 S proteasome-mediated deubiquitination. Deubiquitination reactions contained 13.5 nm purified 26 S proteasomes and 400 nm Lys-48 Ub4 or NT Ub4. E, the authentic isopeptide bond in the middle of NT Ub4 is accessible to the OTU domain of A20. 120 μl of master reaction containing 1 μm A20 (1–365) and 12 μg of Lys-48-linked Ub4 or NT Ub4 was incubated at 30 °C. 20-μl reaction mixtures were withdrawn at each designated time point. The ∼26-kDa band in A20 (1–365) is GST generated from cleavage of GST-A20 (1–365) with thrombin.

It is interesting that the authentic isopeptide bond in NT Ub4 is quite resistant to proteasomal cleavage. We then asked if this bond is accessible to other deubiquitinating enzymes. A20 contains both an E3 Ub ligase domain and an OTU domain that catalyzes deubiquitination (31). The OTU domain of A20 can deubiquitinate Lys-48-linked polyUb chains (32). Incubation of the recombinant OTU domain of A20 with regular Lys-48 Ub4 or NT Ub4 resulted in deubiquitination (Fig. 2E). A20-mediated deubiquitination of NT Ub4 only generated Ub2. In contrast, deubiquitination of regular Lys-48 Ub4 produced Ub3, Ub2, and Ub (Fig. 2E). Together, these results indicate that, compared with regular Lys-48 Ub4, NT Ub4 binds the 26 S proteasome efficiently. However, the chemically cross-linked distal and proximal linkages block the proteasome-mediated progressive chain trimming.

NT Ub4 Is More Potent Than Regular Lys-48 Ub4 in Inhibition of Proteasomal Degradation

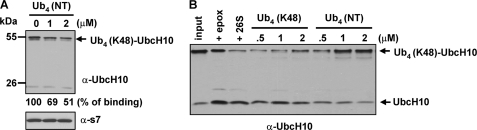

NT Ub4 binds the 26 S proteasome but it is not deubiquitinated into short forms as seen with regular Lys-48 Ub4. Accordingly, we expect NT Ub4 to be a potent competitor for substrate binding and to inhibit proteasomal degradation more efficiently than regular Lys-48 Ub4. To test this, we first examined if NT Ub4 can compete with a substrate for binding to the 26 S proteasome. We performed the spin column assay to monitor the interaction between Ub4 (Lys-48)-UbcH10 and the 26 S proteasome in the absence or in the presence of NT Ub4. In this assay, the 26 S proteasome was inhibited with Ubal and 1,10-phenanthroline to block deubiquitination. As shown in Fig. 3A, we indeed found that free NT Ub4 impaired Ub4 (Lys-48)-UbcH10 binding to the 26 S proteasome. Next, we examined whether NT Ub4 is a more potent inhibitor of proteasomal degradation than regular Lys-48 Ub4. In these assays, different concentrations of Lys-48 Ub4 or NT Ub4 were preincubated with the 26 S proteasome, Ub4 (Lys-48)-UbcH10 was then supplemented to initiate degradation. We found that regular Lys-48 Ub4 started to have a mild degradation inhibitory effect at 2 μm, similar to the inhibitory effect of 0.5 μm NT Ub4. On the other hand, 1 μm NT Ub4 was able to significantly inhibit Ub4 (Lys-48)-UbcH10 degradation (Fig. 3B). Thus, NT Ub4 is a more potent inhibitor of proteasomal degradation than regular Lys-48 Ub4.

FIGURE 3.

NT Ub4 inhibits proteasomal binding and degradation of Ub4 (Lys-48)-UbcH10. A, NT Ub4 inhibits proteasomal binding of Ub4 (Lys-48)-UbcH10. Substrate binding was assayed with the size-exclusion spin column assay. Reactions contained 13.5 nm 26 S proteasome, 100 nm Ub4 (Lys-48)-UbcH10, and different concentrations of NT Ub4 as indicated. The 26 S proteasome was pretreated with 2.5 μm Ubal plus 5 mm 1,10-phenanthroline to block its deubiquitinating activities. Bound Ub4 (NT)-UbcH10 was densitometrically quantified, and bound fractions are listed under the blot. The reaction without NT Ub4 is referenced as 100% of binding. B, NT Ub4 is more potent than regular Lys-48 Ub4 to inhibit proteasomal degradation of Ub4 (Lys-48)-UbcH10. The degradation reactions were analogous to Fig. 1B, except that various concentrations of Ub4 were preincubated with the 26 S proteasome for 5 min prior to the supplementation of Lys-48 Ub4-UbcH10.

NT Ub4 Cannot Target Proteins for Efficient Degradation Compared with Regular Lys-48 Ub4

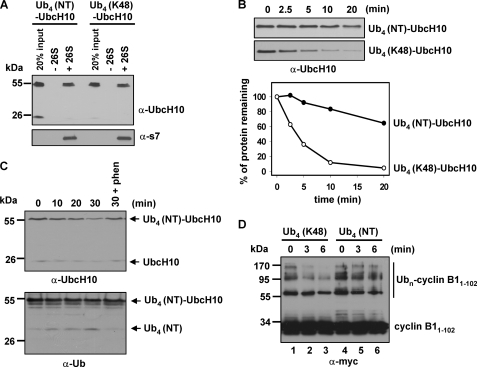

Next, we examined whether NT Ub4 is a competent proteolytic signal. We chose UbcH10 as the substrate to compare its degradation when conjugated with either a regular Lys-48 Ub4 or a NT Ub4. NT Ub4 was conjugated onto UbcH10 using the APC/C E3 complex immunoprecipitated from Xenopus egg extracts, similar to the method for generation of Ub4 (Lys-48)-UbcH10 (11, 17). In the spin column binding assay, we found that both Ub4 (Lys-48)- and Ub4 (NT)-UbcH10 bound the 26 S proteasome equally well (Fig. 4A), indicating that NT Ub4 efficiently targets UbcH10 to the 26 S proteasome. Strikingly, NT Ub4 was unable to promote efficient degradation of UbcH10 compared with regular Lys-48 Ub4 (Fig. 4, B and C). Similar to the inefficient degradation of Ub4 (Lys-48)-UbcH10 in the presence of Ubal (Fig. 1A), Ub4 (NT)-UbcH10 could be slowly degraded, and the degradation was significantly blocked when the chain amputation activity was inhibited with 1,10-phenanthroline (Fig. 4C, last lane). Moreover, NT Ub4 accumulated during the inefficient degradation as revealed by immunoblotting of Ub (Fig. 4C, lower panel). Thus, in targeting UbcH10 for degradation, NT Ub4 has a similar effect as the chain trimming enzyme inhibitor Ubal. In both cases UbcH10 was inefficiently degraded, and free Ub chain accumulated in reactions.

FIGURE 4.

NT Ub4 efficiently targets substrates to the 26 S proteasome but cannot promote efficient degradation compared with regular Lys-48 Ub4. A, both Ub4 (Lys-48)-UbcH10 and Ub4 (NT)-UbcH10 efficiently bind the 26 S proteasome, as determined by the size-exclusion spin column assay. B, NT Ub4 is unable to support efficient UbcH10 degradation compared with regular Lys-48 Ub4. The degradation reactions were analogous to those in Fig. 1B. Degradation of Ub4 (NT)-UbcH10 or Ub4 (Lys-48)-UbcH10 was assayed with immunoblotting of UbcH10 (upper panel) and quantified by densitometry (lower panel). C, Ub4 (NT)-UbcH10 was slowly degraded by the 26 S proteasome and accompanied with accumulation of free NT Ub4. Degradation reactions were analogous to those in Fig. 1A. D, NT Ub4 is less efficient than regular Lys-48 Ub4 to target cyclin B11–102 for proteasomal degradation. Degradation reactions contained 2.3 nm 26 S proteasome and 60 nm ubiquitinated cyclin B11–102.

Next, we aimed to compare the ability of NT Ub4 and regular Lys-48 Ub4 to target degradation of an unstructured protein, myc-cyclin B11–102. We have shown previously that this N-terminal fragment of cyclin B1 is unstructured and that it can be degraded by purified 26 S proteasome without ubiquitination (17). However, ubiquitinated cyclin B11–102 is degraded faster than the nonubiquitinated form, and its degradation requires ATP hydrolysis (17). To obtain ubiquitinated cyclin B11–102, regular Lys-48 Ub4 or NT Ub4 was incubated with His6-tagged cyclin B11–102 in a reaction containing E1, UbcH10, and immunoprecipitated Xenopus APC/C E3 ligase. After the reaction, cyclin B11–102 was purified from the reaction mixtures with nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid resin. As determined with immunoblotting, multiple regular or NT Ub4 chains were conjugated on cyclin B11–102 (Fig. 4D, lanes 1 and 4), likely because cyclin B1 can be ubiquitinated on multiple lysine residues in its N-terminal region (33). The proteasomal degradation assay demonstrated that NT Ub4-conjugated cyclin B11–102 was degraded much slower than that conjugated with regular Lys-48 Ub4. Thus, the NT Lys-48-mimic Ub4 is less efficient than regular Lys-48 Ub4 for targeting degradation of both folded and unstructured proteins.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that inhibition of the polyUb chain trimming activity of the 26 S proteasome with Ubal significantly impaired degradation of Ub4 (K48)-UbcH10; concomitantly free Ub4 was accumulated. Similarly, a NT K48-mimic, which binds the 26 S proteasome efficiently, was unable to target proteins for efficient proteasomal degradation compared with regular K48 Ub4. Also, free NT Ub4 accumulated during inefficient degradation of Ub4 (NT)-UbcH10. Thus, a similar degradation inhibitory effect was observed when the chain trimming activity of the 26 S proteasome was either inhibited with Ubal or disabled with a NT Lys-48-mimic chain. These in vitro results indicate that active chain trimming is necessary to promote proteasomal degradation of some, if not all, proteins conjugated with Lys-48-linked polyUb chain(s). Consistent with our results, inducible nitric oxide synthase and IκB-α were recently found as physiological substrates of Uch37-mediated proteasomal degradation (16), in which IκB-α is known to be modified with Lys-48-linked polyUb chains by the SCFβTrCP E3 ligase for proteasomal degradation during NFκB activation (34).

A critical parameter for efficient degradation is that all activities of the 26 S proteasome, including substrate deubiquitination, unfolding, translocation, and ATP hydrolysis, occur in a coordinated and timed manner. To transduce the deubiquitination signal, chain amputation and chain trimming might function distinctly. It has been shown that the S13 subunit is necessary to maintain the structural integrity of the 26 S proteasome (4). Interestingly, although the S13/Rpn11 subunit is not one of the ATPase subunits of the 26 S proteasome, degradation-coupled chain amputation requires ATP hydrolysis (4, 5) regardless of whether the conjugated substrates are folded or unstructured proteins (17). Presumably, chain amputation is activated when coupled degradation is on. During degradation, chain amputation would not only clear the steric restriction of a polyUb chain to facilitate substrate translocation but also prevent unfolding of the stably folded Ub to save energy. In contrast, chain trimming is likely an always “on” process that occurs as soon as the substrates are loaded onto the 26 S proteasome. It is reasonable to speculate that polyUb chain trimming must maintain appropriate rates to promote degradation. For instance, chain trimming that is too rapid could result in the loss of substrate binding affinity to the 26 S proteasome prior to being unfolded for degradation, whereas chain trimming that is too slow could clog the proteasome. In serving a role to promote degradation, we propose that chain trimming, at least in degradation of some Lys-48-linked polyUb conjugates, timely recycles the Ub binding sites of the 26 S proteasome by trimming the bound polyUb chains into short chains to reduce their proteasomal binding affinity, which prevents clogging the 26 S proteasome and allows continuous substrate loading.

The chain trimming activity has also been found to inhibit degradation, especially for some substrates linked with Lys-63 polyUb chains (11, 12). In cells, Lys-63 polyUb chains play important nonproteolytic roles in regulating kinase activation, protein translation, protein trafficking, and lysosomal degradation (35). Despite the finding that Lys-63 polyUb chains can target degradation of some proteins in vitro (36, 37), recent proteomics studies suggested that Lys-63 polyUb chains are likely not a major proteolytic signal, as their cellular abundances do not increase in response to a short time of proteasome inhibition, whereas the abundances of all other linkages, including Lys-6, Lys-11, Lys-27, Lys-29, Lys-33, and Lys-48, increase promptly (11, 18). We recently provided mechanistic insights on why Lys-63 polyUb chains cannot target most proteins for efficient degradation (11). First, Lys-63 polyUb chains form complexes with Lys-63 polyUb-binding proteins when performing nonproteolytic function in cells. Such complex formation can block binding of Lys-63 polyUb chains to the 26 S proteasome. Second, when targeting to the 26 S proteasome, Lys-63 polyUb chains are rapidly trimmed by the 26 S proteasome compared with that of deubiquitinating Lys-48 polyUb chains. Such rapid chain trimming could rescue the substrates from degradation. In this regard, the chain trimming activity could play a negative role on degradation of some Lys-63-linked conjugates (11, 12). Not surprisingly, inhibition of the chain trimming activity could promote degradation of Lys-63-linked substrates (6, 11, 12, 38). Therefore, depending on the features of conjugated polyUb chains and the substrates themselves, the Ub chain trimming activity could have either a promoting or an inhibitory effect on degradation, which explains different findings about the role of Ub chain trimming in proteolysis (6, 9–13, 16, 17, 38). The mammalian 26 S proteasomes have two Ub chain-trimming enzymes, Uch37 and Usp14, and it remains to be investigated whether these two enzymes have different Ub-linkage specificities and whether they cooperate to regulate polyUb chain trimming.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank J. D. Maller, G. N. DeMartino, A. Ma, and H. T. Yu for providing valuable reagents.

This work was supported in part by grants from the American Heart Association and the American Cancer Society (to C. W. L.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1 and S2.

- Ub

- ubiquitin

- NT

- non-trimmable

- Ubal

- ubiquitin aldehyde.

REFERENCES

- 1. Glickman M. H., Ciechanover A. (2002) Physiol. Rev. 82, 373–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Finley D. (2009) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78, 477–513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tomko R. J., Jr., Funakoshi M., Schneider K., Wang J., Hochstrasser M. (2010) Mol. Cell 38, 393–403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yao T., Cohen R. E. (2002) Nature 419, 403–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Verma R., Aravind L., Oania R., McDonald W. H., Yates J. R., 3rd, Koonin E. V., Deshaies R. J. (2002) Science 298, 611–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lam Y. A., Xu W., DeMartino G. N., Cohen R. E. (1997) Nature 385, 737–740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hu M., Li P., Song L., Jeffrey P. D., Chenova T. A., Wilkinson K. D., Cohen R. E., Shi Y. (2005) EMBO J. 24, 3747–3756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Park K. C., Woo S. K., Yoo Y. J., Wyndham A. M., Baker R. T., Chung C. H. (1997) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 347, 78–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Leggett D. S., Hanna J., Borodovsky A., Crosas B., Schmidt M., Baker R. T., Walz T., Ploegh H., Finley D. (2002) Mol. Cell 10, 495–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Koulich E., Li X., DeMartino G. N. (2008) Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 1072–1082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jacobson A. D., Zhang N. Y., Xu P., Han K. J., Noone S., Peng J., Liu C. W. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 35485–35494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lee B. H., Lee M. J., Park S., Oh D. C., Elsasser S., Chen P. C., Gartner C., Dimova N., Hanna J., Gygi S. P., Wilson S. M., King R. W., Finley D. (2010) Nature 467, 179–184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Qiu X. B., Ouyang S. Y., Li C. J., Miao S., Wang L., Goldberg A. L. (2006) EMBO J. 25, 5742–5753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yao T., Song L., Xu W., DeMartino G. N., Florens L., Swanson S. K., Washburn M. P., Conaway R. C., Conaway J. W., Cohen R. E. (2006) Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 994–1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hamazaki J., Iemura S., Natsume T., Yashiroda H., Tanaka K., Murata S. (2006) EMBO J. 25, 4524–4536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mazumdar T., Gorgun F. M., Sha Y., Tyryshkin A., Zeng S., Hartmann-Petersen R., Jørgensen J. P., Hendil K. B., Eissa N. T. (2010) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 13854–13859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liu C. W., Li X., Thompson D., Wooding K., Chang T. L., Tang Z., Yu H., Thomas P. J., DeMartino G. N. (2006) Mol. Cell 24, 39–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Xu P., Duong D. M., Seyfried N. T., Cheng D., Xie Y., Robert J., Rush J., Hochstrasser M., Finley D., Peng J. (2009) Cell 137, 133–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Raasi S., Pickart C. M. (2005) Methods Mol. Biol. 301, 47–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yin L., Krantz B., Russell N. S., Deshpande S., Wilkinson K. D. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 10001–10010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Russell N. S., Wilkinson K. D. (2004) Biochemistry 43, 4844–4854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chu-Ping M., Vu J. H., Proske R. J., Slaughter C. A., DeMartino G. N. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 3539–3547 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhao M., Zhang N. Y., Zurawel A., Hansen K. C., Liu C. W. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 4771–4780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Husnjak K., Elsasser S., Zhang N., Chen X., Randles L., Shi Y., Hofmann K., Walters K. J., Finley D., Dikic I. (2008) Nature 453, 481–488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schreiner P., Chen X., Husnjak K., Randles L., Zhang N., Elsasser S., Finley D., Dikic I., Walters K. J., Groll M. (2008) Nature 453, 548–552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen X., Lee B. H., Finley D., Walters K. J. (2010) Mol. Cell 38, 404–415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Young P., Deveraux Q., Beal R. E., Pickart C. M., Rechsteiner M. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 5461–5467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhang N., Wang Q., Ehlinger A., Randles L., Lary J. W., Kang Y., Haririnia A., Storaska A. J., Cole J. L., Fushman D., Walters K. J. (2009) Mol. Cell 35, 280–290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Thrower J. S., Hoffman L., Rechsteiner M., Pickart C. M. (2000) EMBO J. 19, 94–102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Piotrowski J., Beal R., Hoffman L., Wilkinson K. D., Cohen R. E., Pickart C. M. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 23712–23721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wertz I. E., O'Rourke K. M., Zhou H., Eby M., Aravind L., Seshagiri S., Wu P., Wiesmann C., Baker R., Boone D. L., Ma A., Koonin E. V., Dixit V. M. (2004) Nature 430, 694–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Komander D., Reyes-Turcu F., Licchesi J. D., Odenwaelder P., Wilkinson K. D., Barford D. (2009) EMBO Rep. 10, 466–473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kirkpatrick D. S., Hathaway N. A., Hanna J., Elsasser S., Rush J., Finley D., King R. W., Gygi S. P. (2006) Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 700–710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Skaug B., Jiang X., Chen Z. J. (2009) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78, 769–796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chen Z. J., Sun L. J. (2009) Mol. Cell 33, 275–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Saeki Y., Kudo T., Sone T., Kikuchi Y., Yokosawa H., Toh-e A., Tanaka K. (2009) EMBO J. 28, 359–371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kim H. T., Kim K. P., Lledias F., Kisselev A. F., Scaglione K. M., Skowyra D., Gygi S. P., Goldberg A. L. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 17375–17386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hanna J., Hathaway N. A., Tone Y., Crosas B., Elsasser S., Kirkpatrick D. S., Leggett D. S., Gygi S. P., King R. W., Finley D. (2006) Cell 127, 99–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.