Abstract

TRIM32, which belongs to the tripartite motif (TRIM) protein family, has the RING finger, B-box, and coiled-coil domain structures common to this protein family, along with an additional NHL domain at the C terminus. TRIM32 reportedly functions as an E3 ligase for actin, a protein inhibitor of activated STAT y (PIASy), dysbindin, and c-Myc, and it has been associated with diseases such as muscular dystrophy and epithelial carcinogenesis. Here, we identify a new substrate of TRIM32 and propose a mechanism through which TRIM32 might regulate apoptosis. Our overexpression and knockdown experiments demonstrate that TRIM32 sensitizes cells to TNFα-induced apoptosis. The RING domain is necessary for this pro-apoptotic function of TRM32 as well as being responsible for its E3 ligase activity. TRIM32 colocalizes and directly interacts with X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis (XIAP), a well known cancer therapeutic target, through its coiled-coil and NHL domains. TRIM32 overexpression enhances XIAP ubiquitination and subsequent proteasome-mediated degradation, whereas TRIM32 knockdown has the opposite effect, indicating that XIAP is a substrate of TRIM32. In vitro reconstitution assay reveals that XIAP is directly ubiquitinated by TRIM32. Our novel results collectively suggest that TRIM32 sensitizes TNFα-induced apoptosis by antagonizing XIAP, an anti-apoptotic downstream effector of TNFα signaling. This function may be associated with TRIM32-mediated tumor suppressive mechanism.

Keywords: Apoptosis, E3 Ubiquitin Ligase, Proteasome, Protein-Protein Interactions, Ubiquitination, TRIM, XIAP

Introduction

TRIM32/HT2A is a member of the tripartite motif (TRIM)5 protein family. To date, 72 TRIM-encoding genes have been identified in the human genome, all sharing the same overall arrangement of RING, B-box, and coiled-coil domains. Their main divergences are in the number of B-boxes and the natures of their C-terminal domains, with most TRIMs possessing one or two additional C-terminal domains, such as B30.2-like/RFP/SPRY, NHL, ARF, PHD, and BROMO domains (1). TRIM32 has one B-box and six repeats of the NHL motif (2).

Several TRIM genes have been associated with disease. For example, mutations in TRIM18/MID1, TRIM20/PYRIN, and TRIM37/MUL have been associated with X-linked Optiz G/BBB syndrome (3), familial Mediterranean fever (4), and mulibrey nanism (5), respectively. Mutations in TRIM32 were recently linked to limb girdle muscular dystrophy type 2H and sarcotubular myopathy, both of which may be caused by the same mutation (D487N) at the third NHL repeat (6). Three additional mutations in the first (R394H), fourth (T520fsX13), and fifth (D588del) NHL repeats of TRIM32 have also been found to cause limb girdle muscular dystrophy type 2H (7). Several TRIM genes have been associated with tumorigenesis; for example, TRIM19/PML (8), TRIM24/TIF1α (9, 10), TRIM25/EFP (11), and TRIM27/RFP (12) have been linked to tumor initiation and progression, and the level of TRIM32 mRNA was found to be up-regulated in epidermal cancers (13). However, the precise biological functions of the majority of TRIM family members have not yet been characterized.

The RING domain is a characteristic signature of many E3 ubiquitin ligases (14). Ubiquitination is a versatile post-translational modification mechanism that eukaryotic cells use mainly to control protein levels through proteasome-mediated proteolysis. The large number and variety of proteins regulated by ubiquitination demand that the process be highly specific; this specificity is governed by the E3 ligases, which comprise a large (and growing) protein family. Many TRIMs have been described as having E3 ligase activity, and the precise substrates of some (but not all) have been identified (15). TRIM2/NARF binds to and ubiquitinates neurofilament light subunit NF-L (16). TRIM11 binds to and regulates the levels of the neuroprotective 24-residue peptide, humanin, and the neurogenic transcription factor, Pax6 (17, 18). TRIM13/LEU5 binds to and degrades CD3-δ (19). TRIM18/MID1 degrades the catalytic subunit of protein phosphatase 2A by binding its α4 regulatory subunit (20). TRIM21/Ro52 interacts with and ubiquitinates immunoglobulin G1 (21). TRIM22 interacts with and ubiquitinates encephalomyocarditis virus 3C protease (22). TRIM25/EFP binds to and ubiquitinates 14-3-3σ, a negative cell cycle regulator (23), and retinoic acid inducible gene I (RIG-I), a cytosolic viral RNA receptor (24). TRIM32 has multiple substrates including actin, protein inhibitor of activated STAT y (PIASy), dysbindin and c-Myc (25–28). TRIM41/RINCK binds to and degrades protein kinase C (29). Finally, TRIM63/MURF1 mediates cardiac troponin I ubiquitination (30). The substrates for the other TRIMs have not yet been fully identified.

A relative decrease in the amount of anti-apoptotic molecules results in cell death. Anti-apoptotic proteins, such as the inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (IAPs), FLICE-inhibitory protein (FLIP), and Bcl-2, may be targeted by proteasomes (31). Among IAPs, X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) is often overexpressed in malignant cells, where it inhibits apoptosis triggered by multiple stimuli (e.g. the mitochondrial, death receptor, and endoplasmic reticulum-mediated pathways of caspase activation) and is associated with poor clinical outcome in certain patients (32). XIAP has been considered a promising target for anti-cancer therapeutics as its degradation is necessary for rapid initiation of the death pathway (33). However, no specific E3 ligase activity (except the autoubiquitination of IAPs) has previously been identified as governing XIAP ubiquitination.

Here, we show for the first time that TRIM32 has specific E3 ligase activity against XIAP and further investigate the role of TRIM32 in tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα)-induced apoptosis. We demonstrate that TRIM32 interacts directly with and down-regulates XIAP through its RING domain-dependent E3 ligase activity.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmid Construction

The full-length human TRIM32 cDNA (IMAGE clone H2906024) was used as a template for PCR-mediated generation of expression constructs. The cDNA fragments encoding the RING finger (amino acids 1–96), B-box (amino acids 97–135), coiled-coil (amino acids 136–254), NHL domain (amino acids 255–653), Tat-interacting domain (amino acids 526–653), RING finger-B-box-coiled-coil domain (amino acids 1–254), and full-length TRIM32 (amino acids 1–653) were PCR-amplified and subcloned into the pFLAG-CMV-2 (Sigma), C-terminally HA-tagged pcDNA3 (Invitrogen), or pEBG vectors for mammalian cell transfection experiments. The full-length human TRIM32 cDNA was also subcloned into the pET30b (Novagen) vector for the production of recombinant proteins in Escherichia coli. The TRIM32 mutants were generated by deletions of RING finger, B-box, or coiled-coil domain using the QuikChange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene), according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Full-length XIAP was cloned into pFLAG-CMV-2, pEGFP-C2 (Clontech), and pET28a (Novagen). The truncated mutants of XIAP encoding amino acids 123–497 (ΔBIR1), 1–123 and 261–497 (ΔBIR2), and 352–497 (ΔBIR123) were generated by PCR with the full-length XIAP as template and cloned into pFLAG-CMV-2 vector. The ΔBIR3 (amino acids 1–263 and 330–497) and ΔRING (amino acids 1–448 and 485–497) mutants of XIAP were generated by using the QuikChange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) with pFLAG-CMV-2 vector encoding full-length XIAP as template. All cDNAs were confirmed by direct sequencing.

Generation of Anti-TRIM32 Antibodies

Recombinant His6-tagged TRIM32 was prepared using Ni2+ affinity purification procedures (Novagen). Mouse and rabbit polyclonal antibodies were obtained by immunizing mice and rabbits with purified TRIM32 proteins. The TRIM32 antibodies specifically recognize recombinant and native TRIM32.

Generation of Stably Overexpressing Cell Lines

To establish a cell line stably overexpressing full-length human TRIM32, we used the pMSCVpuro vector (Clontech). Retroviral stocks were produced according to the manufacturer's instructions (Clontech). Briefly, GP-293 packaging cells were plated in 100-mm dishes and cotransfected with pVSV-G (Clontech) and the recombinant retroviral vector (pMSCVpuro or pMSCVpuroTRIM32) using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen). After transfection, the cells were incubated at 32 °C to increase the viral titer. Forty-eight hours later, supernatants containing the retroviral particles were collected, filtered through 0.45-μm filters, and used to infect target cells in the presence of 4 μg/ml Polybrene (Sigma). Infected cells were thereafter selected through incubation with 1 μg/ml puromycin (Sigma).

Generation of the Knockdown Cell Line

For the down-regulation of TRIM32 expression, shRNAs were designed using the BLOCK-iTTM RNAi designer (Invitrogen). The selected sense sequences were 5′-GGTGGAAAGCTTTGGTGTTTC-3′ (shTRIM32 1467–1488). Complementary oligonucleotides consisting of sense, hairpin loop, and antisense sequences were annealed and ligated into the pLenti/H1/TO shRNA expression vector (Invitrogen). The lentivirus and stably transfected cells were generated according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). Briefly, HEK293T cells were plated in 100-mm dishes and cotransfected with pLP1, pLP2, pVSV-G (Invitrogen), and recombinant retroviral (pLenti/H1/TOpuro or pLenti/H1/TOsh1467) vectors using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen). Forty-eight hours after transfection, supernatants containing the lentiviral particles were collected and used to infect target cells in the presence of 4 μg/ml Polybrene. Infected cells were selected by incubation with 1 μg/ml puromycin.

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblotting

HEK293, HEK293T, and HeLa cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen) in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C. Cells were transfected by the calcium phosphate precipitation method or Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) method. At the indicated times after transfection, cells were harvested and lysed in a lysis buffer containing 20 mm HEPES (pH 7.2), 50 mm NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, 0.1 mm Na3VO4, 1 mm NaF, 1 mm 4-(2-aminoethyl)-benzenesulfonyl fluoride hydrochloride, 2 mg/ml leupeptin, and 5 mg/ml aprotinin. The lysates were incubated with FLAG-agarose beads (Sigma) or HA-agarose beads (Sigma) for 12 h at 4 °C, washed three times with lysis buffer, resuspended in SDS-PAGE sample buffer, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Schleicher & Schuell). For immunoprecipitation of endogenous proteins, cell lysates were incubated with mouse polyclonal anti-XIAP antiserum or control mouse preimmune serum at 4 °C for 12 h. Protein A/G-Sepharose beads (Amersham Biosciences) were added to the reaction for another 4 h of incubation, washed with lysis buffer, resuspended in SDS-PAGE sample buffer, and subjected to SDS-PAGE. After being blocked with 5% skim milk in Tris-buffered saline (20 mm Tris, pH 7.4, and 150 mm NaCl) containing 0.05% Tween 20, the membranes were probed with a mouse or rabbit anti-human TRIM32 antiserum, anti-FLAG (Sigma), anti-β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-HA (Sigma), anti-cleaved caspase-3 (Cell Signaling Technology), anti-ubiquitin (Calbiochem), anti-green fluorescent protein (GFP) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-glutathione S-transferase (GST) (Amersham Biosciences), anti-cIAP-1 (Cell Signaling Technology), anti-cIAP-2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-Bcl-xL (BD Pharmingen), anti-Bcl-2 (BD Pharmingen), anti-FLIP (Cell Signaling Technology), anti-Mcl 1 (Cell Signaling Technology), or anti-XIAP (Cell Signaling Technology). Blots were washed three times with Tris-buffered saline containing Tween 20 and incubated with peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse, anti-goat, or anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G antibodies. The results were visualized through the use of a chemiluminescence detection system (Pierce).

Caspase Assay

The caspase-3 activity of cell extracts (∼106 cells) was determined using the synthetic substrate, acetyl-Asp-Glu-Val-Asp-7-amino-4-methyl coumarin (DEVD-AMC; Peptron), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The AMC fluorescence released by active caspase-3 was measured at an excitation wavelength of 360 nm and an emission wavelength of 460 nm. The results are expressed as -fold increase in the caspase activity of sample cells as compared with that from control vector-transfected cells.

Cell Death Assays

Annexin V, a specific reagent for phosphatidylserine, was used to stain the apoptotic cells. HEK293T cells were cultured on coverslips for 36 h, treated with 100 ng/ml TNFα, incubated for another 12 h, washed with PBS, and subsequently washed with a buffer (10 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 140 mm NaCl, and 2.5 mm CaCl2). The samples were then stained with annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC; BD Pharmingen) diluted 1:40 in the same buffer for 15 min at room temperature, and washed with PBS. After fixation with 3.7% paraformaldehyde, the cells were observed under a fluorescence microscope. For assessment of nuclear fragmentation, Lipofectamine was used to transfect HeLa cells with the indicated constructs. The cells were incubated for 24 h and then treated with 50 ng/ml TNFα and 100 ng/ml cycloheximide. After 12 h, cells were fixed, permeabilized, stained with Hoechst dye (Sigma), and then observed under a fluorescence microscope. Cell viability was assessed as the ability to metabolize 1-(4,5-demethyldiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT).

In Vitro Ubiquitin Ligation Assay

Recombinant human E1 and E2 enzymes were prepared as described previously (34), as was phosphorylated ubiquitin (35). A recombinant ubiquitin that could be phosphorylated by the cAMP-dependent protein kinase was constructed by inserting the nucleotide sequence encoding the kinase recognition motif, LRRASV (36), in front of the second codon of the human ubiquitin sequence. The recombinant ubiquitin was Ni2+ affinity-purified and then phosphorylated by cAMP-dependent protein kinase (1 unit to 7 μg of substrate) in a buffer containing 20 mm Tris (pH 7.4), 12 mm MgCl2, 2 mm NaF, 50 mm NaCl, 25 μm ATP, 5 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP, and 0.1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin. The autoubiquitination reaction mixtures (30 μl) contained 50 mm Tris (pH 7.4), 5 mm MgCl2, 2 mm NaF, 10 nm okadaic acid, 2 mm ATP, 0.6 mm DTT, 5 μg of 32P-labeled ubiquitin, E1 enzyme (2 pmol), E2 enzyme (UbcH5A, UbcH5B, UbcH5C, or hCdc34; 10 pmol), and the purified His6-tagged TRIM32 protein (3 or 10 pmol). The mixtures were incubated at 37 °C for 60 min, the reaction was terminated with SDS sample buffer, and the samples were boiled for 3 min prior to SDS-PAGE. The polyubiquitin chains were analyzed by autoradiography. The target ubiquitination assay was carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions (Enzo Life Sciences) with a minor modification using GST-fused XIAP protein prepared from E. coli as a substrate. Purified GST-XIAP (100 nm) and His6-tagged TRIM32 protein (full-length or RING deletion mutant, 50 nm) were incubated in a reaction buffer including 50 mm Tris-HCl, 1 mm DTT, 5 mm MgCl2, 5 mm ATP, and 2.5 μm biotinylated ubiquitin at 30 °C for 1 h. After the addition of E1 (100 nm) and E2 (UbcH6, 2.5 μm) enzymes, the reaction mixtures were incubated at 37 °C for another 2 h. The reaction was terminated by adding SDS sample buffer, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and analyzed by immunoblotting.

RESULTS

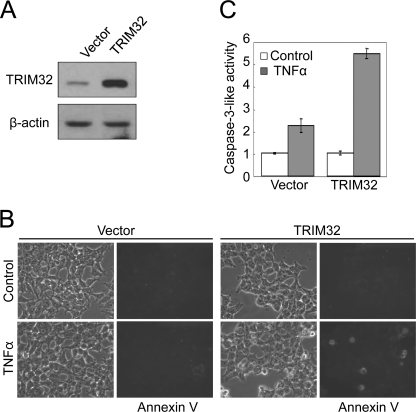

TRIM32 Overexpression Sensitizes TNFα-induced Apoptosis

Given that many TRIM proteins (e.g. TRIM11, TRIM19, TRIM27, TRIM35, TRIM39, and TRIM69) play roles in apoptosis (18, 37–41), we examined the effect of TRIM32 overexpression on apoptosis. We generated an HEK293T cell line that stably overexpressed TRIM32 proteins at an ∼5-fold higher level than that seen in the vector control (Fig. 1A). TRIM32 overexpression alone did not appear to induce significant morphological changes (Fig. 1B, upper right panel). Within 12 h after treatment with TNFα, however, overexpressing cells became round, displayed membrane ruffling, and initiated detachment from the dish (all characteristics suggestive of apoptosis), whereas the control cell line stably harboring the empty plasmid was relatively unaffected by TNFα treatment (Fig. 1B, lower panels). Following TNFα treatment, TRIM32-overexpressing cells also showed markedly more annexin V-positive cells (Fig. 1B, lower right panel) and elevated caspase-3 activity (Fig. 1C) as compared with control cells, indicating increased apoptosis in the TRIM32-overexpressing cells. We thus conclude that TRIM32 expression sensitizes cells to TNFα-induced apoptosis. It has been well known that simultaneous activation of NFκB by TNFα induces the expression of anti-apoptotic genes (e.g. IAPs, FLIP, and Bcl-2) that inhibit the pro-apoptotic signaling activated by TNFα (42–46). Thus, the de novo protein synthesis inhibitor, cycloheximide, is often used in combination with TNFα to induce apoptosis. Based on our results, we speculated that TRIM32 may facilitate TNFα-induced apoptotic signaling by down-regulating the anti-apoptotic pathway.

FIGURE 1.

TRIM32 sensitizes cells to TNFα-induced apoptosis. HEK293T cells stably transfected with a TRIM32-expressing plasmid or control vector were selected in the presence of 1 μg/ml puromycin. A, cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting with an affinity-purified anti-TRIM32 antibody. β-Actin was assessed as a loading control. B, cells were treated with 50 ng/ml TNFα for 6 h, stained with annexin V-FITC, and observed under a fluorescence microscope. C, caspase-3 activity was detected with a fluorometric assay, using DEVD-AMC as a substrate. Data are expressed as the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments.

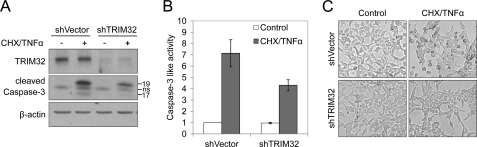

Down-regulation of TRIM32 Causes Resistance to TNFα-induced Apoptosis

To confirm the role of TRIM32 in TNFα-induced apoptosis, we down-regulated TRIM32 expression by RNA interference-mediated silencing using short hairpin RNA (shRNA) and examined caspase activity and cell morphology following treatment with TNFα and cycloheximide. Cells transfected with the TRIM32 shRNA construct showed ∼70% lower TRIM32 expression levels as compared with vector-treated controls (Fig. 2A, upper panel). This TRIM32 knockdown reduced the level of TNFα-induced caspase-3 activation, as assessed by a caspase-3 autocleavage assay (Fig. 2A, middle panel) and a DEVD-AMC cleavage assay (Fig. 2B), and decreased the extent of apoptotic morphology (Fig. 2C). Collectively, these findings suggest that TRIM32 is linked with TNFα-induced apoptotic signaling.

FIGURE 2.

TRIM32 knockdown makes cells resistant to TNFα-induced apoptosis. HEK293T cells were infected with lentiviral constructs for expressing TRIM32 shRNA or control shRNA, and the infected cells were pooled after 1 μg/ml puromycin selection. The cells were then treated with 50 ng/ml TNFα and 100 ng/ml cycloheximide (CHX) for 12 h. A, cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting with an anti-TRIM32 antibody to detect TRIM32 expression levels and with an anti-cleaved caspase-3 antibody to detect caspase-3 activity. ns, nonspecific. B, caspase-3 activity was also detected with a fluorometric assay Data are expressed as the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments. C, cell morphologies were observed under a microscope.

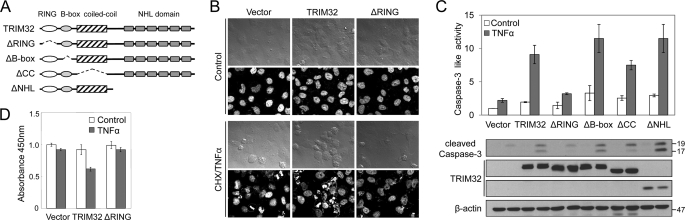

TRIM32 Sensitizes Cells to Apoptosis via Its RING Finger Domain

To investigate which region of TRIM32 is required for its effect on TNFα-induced apoptosis, we constructed a series of TRIM32 deletion mutants (Fig. 3A). Transient transfection of vectors expressing full-length TRIM32 into HeLa cells followed by treatment with TNFα and cycloheximide for 12 h exacerbates representative apoptotic features, such as nuclear fragmentation (Fig. 3B). Transfection of vectors encoding RING finger-deleted TRIM32 did not affect this nuclear fragmentation (Fig. 3B), whereas transient transfection of vectors encoding B-box- or coiled-coil-deleted proteins had the same effect as transfection of full-length TRIM32 (data not shown). When these TRIM32 deletions were tested for their abilities to activate caspase-3 in HEK293 cells, as assessed by a caspase-3 autocleavage assay and a DEVD-AMC cleavage assay (Fig. 3C), we found that deletion of the RING finger consistently abolished the TRIM32-associated caspase-3 activation, whereas the other deletions had insignificant effects. In addition, cell viability measurement using an MTT assay confirmed that TRIM32 sensitizes cells to TNFα-induced apoptosis in a RING finger-dependent manner (Fig. 3D).

FIGURE 3.

TRIM32 regulates TNFα-induced apoptosis through its RING domain. A, schematic representation of full-length TRIM32 and the TRIM32 deletions (ΔRING, ΔB-box, ΔCC, ΔNHL) used to determine the domain responsible for sensitizing cells to TNFα-induced apoptosis. B, HeLa cells were transiently transfected with vectors encoding full-length or RING finger-deleted TRIM32. After 24 h, cells were treated with 50 ng/ml TNFα and 100 ng/ml cycloheximide (CHX) for 12 h. Cell morphology was observed under a microscope (upper panels), and nuclear morphology was examined by Hoechst staining (lower panels). C, HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with vectors encoding full-length and deleted TRIM32. After 24 h, cells were treated with 100 ng/ml TNFα for 12 h. The caspase-3 activities of cell lysates were analyzed by detecting DEVD-AMC hydrolysis and proteolytic cleavage of caspase-3. Data are expressed as the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments. Expression of the various TRIM32 proteins was confirmed by immunoblotting with an anti-HA antibody and normalized with an anti-β-actin antibody on the same blot. D, HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with vectors encoding full-length and RING-deleted TRIM32. After 24 h, cells were treated with 100 ng/ml TNFα for 12 h. Cell viability was measured by the MTT assay. Data are expressed as the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments.

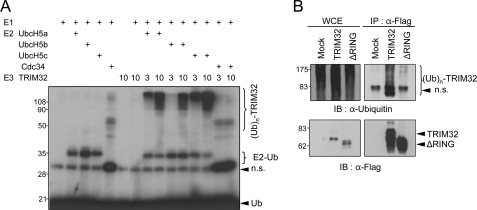

TRIM32 Has RING Finger-dependent Ubiquitin Ligase Activity

TRIM32 has been considered as an E3 ubiquitin ligase due to the presence of the RING finger domain in its structure. In the present study, we performed an in vitro ubiquitination assay with purified recombinant TRIM32 protein. In agreement with a previous report (25), recombinant TRIM32 displayed autoubiquitination in the absence of substrate and in the presence of ATP, ubiquitin, the E1 enzyme, and E2 enzymes such as UbcH6 (see below), UbcH5a, and UbcH5c, but not Cdc34 (Fig. 4A). We found that UbcH5b also functioned as an E2 for TRIM32, although to a lesser extent than UbcH5a or UbcH5c under our experimental conditions (Fig. 4A, lanes 10 and 11). To test the in vivo relevance of the E3 ligase activity of TRIM32, we transfected HEK293 cells with vectors encoding full-length or RING finger-deleted TRIM32 and analyzed the autoubiquitination of TRIM32. Ubiquitin-conjugated high molecular mass TRIM32 complexes accumulated in lysates from cells transfected with vectors encoding full-length TRIM32, but not in lysates from cells expressing the RING finger deletion mutant (Fig. 4B, right panel) or the RING finger point mutant (C23A, data not shown). These findings indicate that TRIM32 has RING finger-dependent E3 ubiquitin ligase activity.

FIGURE 4.

TRIM32 has RING finger-dependent ubiquitin (Ub) ligase activity. A, in vitro autoubiquitination assay of recombinant TRIM32. Purified recombinant TRIM32 protein was incubated together with E1 and an E2 (UbcH5A, UbcH5B, UbcH5C, or Cdc34), along with 32P-labeled ubiquitin and ATP. The results were visualized using autoradiography. n.s., nonspecific. B, intracellular autoubiquitination of TRIM32. Vectors encoding FLAG-tagged full-length TRIM32 or the RING-deleted TRIM32 were transiently transfected into HEK293 cells. After 30 h, cells were lysed and immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG-agarose. Immunoprecipitates (IP) and whole cell extracts (WCE) were analyzed by immunoblotting (IB) with anti-ubiquitin and anti-FLAG antibodies.

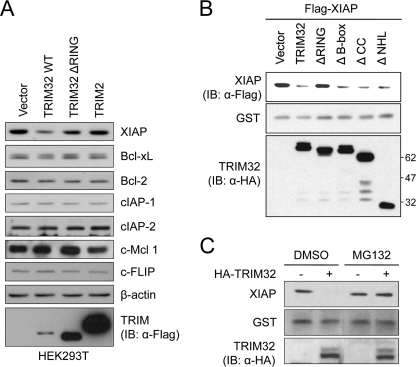

TRIM32 Expression Down-regulates XIAP in a Proteasome-dependent Manner

Based on the above results, we speculated that TRIM32 may ubiquitinate an anti-apoptotic protein, targeting it for degradation and thereby facilitating TNFα-induced apoptosis. To examine this hypothesis further, we examined whether TRIM32 expression could down-regulate the expression levels of the major known anti-apoptotic proteins, including NFκB and its downstream effectors, such as members of the Bcl-2 family, the IAP family, and FLIP (47). Determination of the endogenous protein level of Bcl-xL, Bcl-2, cellular IAP-1 (cIAP-1), cellular IAP-2 (cIAP-2), Mcl 1, FLIP, and XIAP revealed that transient transfection of vectors encoding TRIM32 decreased the cellular level of endogenous XIAP, but did not affect the levels of Bcl-xL, Bcl-2, cIAP-1, cIAP-2, Mcl 1, or FLIP in HEK293T (Fig. 5A). Consistently, TRIM32 overexpression specifically decreased XIAP level in C2C12 murine myoblast cells (supplemental Fig. S1).

FIGURE 5.

TRIM32 induces degradation of XIAP in a RING finger-dependent manner. A, vectors encoding FLAG-tagged full-length TRIM32, RING-deleted TRIM32, or TRIM2 were transiently transfected into HEK293T. After 36 h, cells were treated with 50 ng/ml TNFα and 100 ng/ml cycloheximide for 12 h. The amounts of endogenous XIAP, cIAP-1, cIAP-2, Bcl-xL, Bcl-2, c-Mcl 1, and c-FLIP proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting (IB) with their specific antibodies. β-Actin was monitored as a loading control. B, vectors encoding HA-tagged full-length or the various deleted TRIM32 were transiently cotransfected into HEK293 cells along with vectors encoding FLAG-tagged XIAP and pEBG (GST control). XIAP levels were determined by immunoblotting with an anti-FLAG antibody, and the results were normalized to those obtained with an anti-GST antibody. The expression levels of the TRIM32 constructs were detected by immunoblotting with an anti-HA antibody. C, HeLa cells were transiently transfected with the vector encoding HA-tagged TRIM32 or the control vector. After 24 h, cells were incubated with or without 10 μm MG132 for 4 h. Cell extracts were prepared and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-XIAP and anti-HA antibodies, and the results were normalized to those from an anti-GST antibody.

To localize the region of TRIM32 required for XIAP down-regulation, we cotransfected HEK293 cells with various TRIM32 deletion constructs and FLAG-tagged XIAP and then determined the cellular levels of XIAP (Fig. 5B). TRIM32 overexpression decreased the levels of ectopically expressed XIAP. Although deletion of B-box or coiled-coil domain from TRIM32 did not block this XIAP down-regulation, the RING finger deletion mutant failed to down-regulate XIAP, indicating that XIAP regulation by TRIM32 is RING finger-dependent (Fig. 5B). To examine whether this regulation is specific for TRIM32, we performed parallel experiments using another TRIM family member, TRIM2, which shares exactly same domains with TRIM32. TRIM2 expression did not affect XIAP levels (Fig. 5A). We thus suggest that TRIM32 specifically controls XIAP protein levels through its E3 ligase activity.

To examine whether the down-regulation of XIAP by TRIM32 is proteasome-mediated, we determined endogenous XIAP levels in the absence or presence of MG132, an inhibitor of the 26 S proteasome. Treatment of cells with 10 μm MG132 blocked the TRIM32-induced reduction in XIAP levels (Fig. 5C). These results, together with those shown in Fig. 4, suggest that TRIM32 promotes proteasome-dependent degradation of XIAP via its E3 ligase activity.

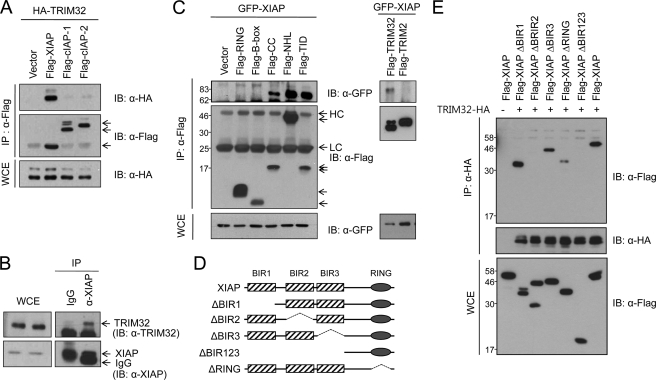

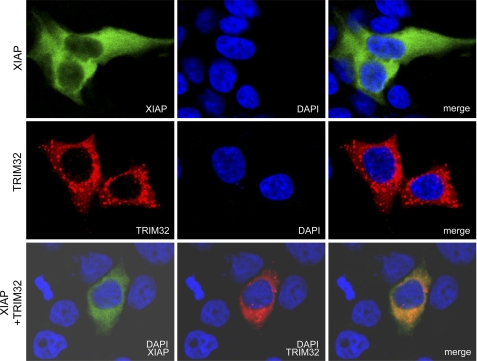

TRIM32 Interacts with XIAP

Several TRIM family members have been shown to bind to their relevant substrates. To determine whether TRIM32 interacts directly with XIAP, we cotransfected HEK293T cells with HA-tagged TRIM32 and FLAG-tagged IAPs (XIAP or the control IAPs, cIAP-1 or cIAP-2), recovered the immunoprecipitates, and analyzed them by immunoblotting. TRIM32 was consistently detected in immunoblots of FLAG-XIAP immunoprecipitates but not in FLAG-cIAP-1 or FLAG-cIAP-2 immunoprecipitates (Fig. 6A). To test for an endogenous interaction, we immunoprecipitated HEK293T cell lysates with an anti-XIAP antibody and used an anti-TRIM32 antibody for immunoblotting. Specific coprecipitation of endogenous TRIM32 was detected with the anti-XIAP antibody but not with control preimmune serum (Fig. 6B). To define the XIAP binding domain in TRIM32, we used a series of FLAG-tagged TRIM32 domain constructs and analyzed their binding to GFP-XIAP by immunoprecipitation (Fig. 6C). Neither the RING finger domain (amino acids 1–96) nor the B-box domain (amino acids 97–135) of TRIM32 could bind to XIAP. However, both the coiled-coil domain (amino acids 136–254) and the NHL domain (amino acids 255–653; or more precisely, the fourth to sixth NHL repeats; Tat-interacting domain, amino acids 526–653) of TRIM32 were able to interact with XIAP. In contrast, TRIM2 could not bind to XIAP, indicating the specificity of the TRIM32-XIAP interaction (Fig. 6C, right panel). To define the TRIM32 binding domain within XIAP, we prepared a series of XIAP truncation mutants and analyzed their binding to TRIM32 by immunoprecipitation (Fig. 6, D and E). XIAP mutants without the BIR2 domain, such as FLAG-XIAP ΔBIR2 and FLAG-XIAP ΔBIR123, could not bind to TRIM32. However, ΔBIR1, ΔBIR3, and ΔRING XIAP mutants retained the ability to bind to TRIM32. Together, the results indicate that the BIR2 domain of XIAP and both the coiled-coil and the NHL domains of TRIM32 are critical for interaction between these two proteins. We next examined the localization of TRIM32 and XIAP in HEK293T cells coexpressing HA-tagged TRIM32 and FLAG-tagged XIAP. The immunostaining patterns of the two proteins were superimposed, suggesting that the proteins colocalize (Fig. 7).

FIGURE 6.

TRIM32 interacts with XIAP. A, vectors encoding HA-tagged TRIM32 and FLAG-tagged XIAP, cIAP-1, or cIAP-2 were transiently transfected into HEK293 cells. After 30 h, cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with mouse anti-FLAG-agarose beads and analyzed by immunoblotting (IB) with rabbit anti-HA and anti-FLAG antibodies. WCE, whole cell extracts. B, HEK293T cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with a mouse anti-XIAP antibody or mouse preimmune serum and analyzed by immunoblotting with a rabbit anti-TRIM32 antibody. C, vectors encoding GFP-tagged XIAP and a FLAG-tagged TRIM32 domain (RING, B-box, coiled-coil, NHL, or Tat-interacting domain (TID)), full-length TRIM32, or TRIM2 were transiently transfected into HEK293 cells. After 30 h, cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with mouse anti-FLAG-agarose beads and analyzed by immunoblotting with a rabbit anti-GFP antibody. HC, immunoglobulin heavy chain; LC, immunoglobulin light chain. D, schematic representation of full-length XIAP and the truncated mutants (ΔBIR1, ΔBIR2, ΔBIR3, ΔRING, and ΔBIR123) used to determine the domain responsible for binding to TRIM32. E, vectors encoding HA-tagged TRIM32 and FLAG-tagged XIAP variants were transiently transfected into HEK293T cells. The cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA-agarose beads and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-FLAG antibody.

FIGURE 7.

Colocalization of TRIM32 and XIAP. Vectors encoding FLAG-tagged XIAP and HA-tagged TRIM32 were transiently cotransfected into HEK293 cells. After 24 h, cells were immunostained with mouse anti-FLAG and rabbit anti-HA antibodies, reacted with FITC-labeled anti-mouse IgG and TRITC-labeled anti-rabbit IgG, and finally counterstained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI).

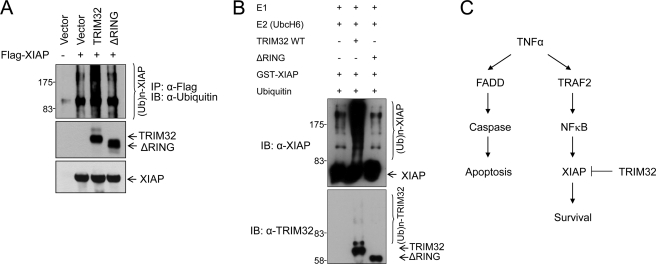

TRIM32 Ubiquitinates XIAP

Our findings that TRIM32 has E3 ubiquitin ligase activity (Fig. 4), XIAP levels are decreased in TRIM32-overexpressing cells (Fig. 5), and TRIM32 specifically interacts with XIAP (Figs. 6 and 7) suggest that XIAP might be a substrate for TRIM32 E3 ligase activity. To examine this possibility in more detail, we tested the polyubiquitination of XIAP in vivo and in vitro. We found that ubiquitin-conjugated high molecular mass XIAP complexes accumulated in HEK293 cells expressing full-length TRIM32 but much less in those expressing the RING finger deletion mutant (Fig. 8A). Weak accumulation of a high molecular mass XIAP complex in cells expressing XIAP alone or with mutant TRIM32 is likely caused by self-ubiquitination of XIAP (48). To test whether XIAP is directly ubiquitinated by TRIM32, an in vitro ubiquitination assay was performed with purified proteins (Fig. 8B). Recombinant TRIM32 displayed ubiquitination activity against recombinant XIAP in the presence of ATP, ubiquitin, E1, and E2 (UbcH6), whereas the RING finger deletion mutant did not. These results together indicate that TRIM32 ubiquitinates XIAP through its RING finger-dependent E3 ligase activity. Based on our findings that TRIM32 sensitizes cells to TNFα-induced apoptosis in a RING finger-dependent manner, TRIM32 has RING finger-dependent E3 ligase activity, and TRIM32 promotes proteasome-dependent degradation of XIAP via direct binding and ubiquitination, we propose that TRIM32 sensitizes TNFα-induced apoptosis by inhibiting an anti-apoptotic pathway via its RING finger-dependent E3 ubiquitin ligase activity against XIAP (Fig. 8C).

FIGURE 8.

TRIM32 ubiquitinates XIAP. A, vectors encoding FLAG-tagged XIAP and HA-tagged full-length or RING-deleted TRIM32 were transiently transfected into HEK293 cells. Cells were treated with MG132 for 4 h prior to preparing cell extracts. At 30 h after transfection, cell lysates were prepared and immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG-agarose. Ubiquitination of XIAP was confirmed using an anti-ubiquitin antibody. IP, immunoprecipitate; IB, immunoblot. B, purified recombinant GST-XIAP was first incubated with full-length or RING-deleted TRIM32 in the presences of ATP and biotinylated ubiquitin (Ub) for 1 h at 30 °C, and then E1 and E2 (UbcH6) were added. The mixture was incubated for an additional 2 h at 37 °C and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-XIAP and anti-TRIM32 antibodies. C, schematic representation of our proposed model for TRIM32-induced enhancement of TNFα-induced apoptosis, in which TRIM32 inhibits an anti-apoptotic pathway by degrading XIAP with its E3 ligase activity, thereby sensitizing the pro-apoptotic pathway.

DISCUSSION

Here, we show that TRIM32 ubiquitinates XIAP and targets it for proteasomal degradation. Proteasome-mediated degradation of IAPs may be an important regulatory step through which cells that have received an apoptotic signal actually progress to cell death. A previous report found that cIAP and XIAP were selectively lost in glucocorticoid- and etoposide-treated thymocytes prior to cell death (49). Furthermore, the protein levels of XIAP were shown to decrease during cisplatin-induced apoptosis of ovarian surface epithelial cancer cell lines (50). IAPs have been shown to catalyze their own ubiquitination, suggesting that their abundance may be actively self-regulated (49). However, RING-less XIAP is not completely resistant to proteasome-mediated degradation, prompting researchers to speculate that this protein can also serve as a target for other E3 ligases (49). A recent report showed that the RING domain of cIAP-1 allows it to bind directly to the RING domain of XIAP, triggering ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of XIAP, thereby revealing a mechanism for regulating the abundance of IAPs (51). This cross control of IAPs might explain why cIAP protein levels are elevated in XIAP-null mice and why XIAP-null mice have a normal phenotype (52). Three negative regulators of XIAP have been identified to date: XIAP-associated factor (XAF1), Smac/direct IAP-binding protein with low pI (DIABLO), and Omi/HtrA2, a serine protease. XAF1 redistributes XIAP from the cytoplasm to the nucleus, resulting in the inactivation of XIAP (53). Smac/DIABLO is released from mitochondria and inhibits XIAP by stoichiometric binding, increasing the availability of caspase-9 to activate the effector caspases (54, 55). Omi/HtrA2 is also released from mitochondria; it catalytically cleaves and thereby irreversibly inactivates IAPs (56, 57). In addition to these known regulators, we herein identify TRIM32 as a novel negative regulator that catalyzes the ubiquitination of XIAP. We observed that TRIM32 bound to and directly catalyzed XIAP ubiquitination in a RING finger-dependent manner. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that TRIM32 may cause indirect ubiquitination of XIAP under certain circumstances. Two possible scenarios may be envisaged. First, TRIM32 may stimulate the XIAP E3 ligase activity that is directed against XIAP itself. Second, TRIM32 may alter an auxiliary factor that in turn stimulates ubiquitination of XIAP.

TNFα, a cytokine known to trigger death receptor-mediated apoptosis, simultaneously induces both the caspase-dependent pro-apoptotic pathway and the NFκB-mediated anti-apoptotic pathway (58) (Fig. 8C). Specific inhibition of this anti-apoptotic pathway, for example by down-regulation of NFκB or one of its downstream effectors (e.g. XIAP, FLIP, or Bcl-xL), may facilitate the pro-apoptotic pathway of TNFα signaling (47). Here, we propose that TRIM32 sensitizes TNFα-induced apoptosis by inhibiting an anti-apoptotic pathway via direct ubiquitination of XIAP. As XIAP is known to block the actions of caspases involved in apoptosis induced by either the extrinsic or the intrinsic pathways, we further tested whether TRIM32 sensitized apoptosis induced by pro-apoptotic agents other than TNFα, an extrinsic signal transducer (59). As shown in supplemental Fig. S2, TRIM32 expression also exacerbated apoptosis induced by etoposide and staurosporine, both of which trigger the intrinsic pathway. This suggests that TRIM32 may act as a general sensitizer of various pro-apoptotic signals triggering either the intrinsic or the extrinsic pathway.

As an E3 ubiquitin ligase, TRIM32 has multiple physiological substrates and is likely to be involved in a variety of physiological functions. Actin, protein inhibitor of activated STAT y (PIASy), Abl interactor 2, and dysbindin have all been identified as TRIM32 substrates, degradation of which is involved in myogenesis and epithelial carcinogenesis, possibly in a cell type-specific manner (25–27, 60). Recently, targeted degradation of c-Myc by TRIM32 was shown to induce neuronal differentiation and to inhibit proliferation of neural progenitor cells (28). Mutations of Drosophila TRIM32 orthologs, Brat and Mei-P26, develop tumors in flies (61). However, redundancy with other tumor suppressors that prevents overproliferation could provide an explanation for the lack of tumor promotion when TRIM32 was mutated in vertebrates (28). Here, we report a new TRIM32 substrate: XIAP. XIAP is frequently overexpressed in malignant tissues and is thus regarded as a potential cancer therapeutic target (32, 33). We demonstrate that TRIM32 interacts with and ubiquitinates XIAP in a RING finger-dependent manner and thus sensitizes TNFα-induced apoptosis. Therefore, we suggest that TRIM32 should perhaps be considered a novel tumor-suppressive agent.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jong-Bok Yoon for providing cIAP-1, cIAP-2, and XIAP cDNA, Dong Uk Kim, Young Chul Choi, Eun Hee Kim, and So Hee Dho for helpful discussions, and Seon-Young Kim for database analysis.

This work was supported by grants from the Korea Research Council of Fundamental Science and Technology (KRCF) and the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea (Grants 20110002141 and 2010-0014635) (to K. S. K.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1 and S2.

- TRIM

- tripartite motif

- IAP

- inhibitor of apoptosis

- XIAP

- X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis

- cIAP

- cellular

- AMC

- 7-amino-4-methyl coumarin

- MTT

- 1-(4,5-demethyldiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- FLIP

- FLICE-inhibitory protein

- FLICE

- FADD-like IL-1β-converting enzyme

- FADD

- Fas-associated death domain

- TRITC

- tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate.

REFERENCES

- 1. Reymond A., Meroni G., Fantozzi A., Merla G., Cairo S., Luzi L., Riganelli D., Zanaria E., Messali S., Cainarca S., Guffanti A., Minucci S., Pelicci P. G., Ballabio A. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 2140–2151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Slack F. J., Ruvkun G. (1998) Trends Biochem. Sci. 23, 474–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dal Zotto L., Quaderi N. A., Elliott R., Lingerfelter P. A., Carrel L., Valsecchi V., Montini E., Yen C. H., Chapman V., Kalcheva I., Arrigo G., Zuffardi O., Thomas S., Willard H. F., Ballabio A., Disteche C. M., Rugarli E. I. (1998) Hum. Mol. Genet. 7, 489–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bernot A., da Silva C., Petit J. L., Cruaud C., Caloustian C., Castet V., Ahmed-Arab M., Dross C., Dupont M., Cattan D., Smaoui N., Dodé C., Pêcheux C., Nédelec B., Medaxian J., Rozenbaum M., Rosner I., Delpech M., Grateau G., Demaille J., Weissenbach J., Touitou I. (1998) Hum. Mol. Genet. 7, 1317–1325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Avela K., Lipsanen-Nyman M., Idänheimo N., Seemanová E., Rosengren S., Mäkelä T. P., Perheentupa J., Chapelle A. D., Lehesjoki A. E. (2000) Nat. Genet. 25, 298–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Frosk P., Weiler T., Nylen E., Sudha T., Greenberg C. R., Morgan K., Fujiwara T. M., Wrogemann K. (2002) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 70, 663–672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Saccone V., Palmieri M., Passamano L., Piluso G., Meroni G., Politano L., Nigro V. (2008) Hum. Mutat 29, 240–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. de Thé H., Lavau C., Marchio A., Chomienne C., Degos L., Dejean A. (1991) Cell 66, 675–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Allton K., Jain A. K., Herz H. M., Tsai W. W., Jung S. Y., Qin J., Bergmann A., Johnson R. L., Barton M. C. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 11612–11616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Khetchoumian K., Teletin M., Tisserand J., Mark M., Herquel B., Ignat M., Zucman-Rossi J., Cammas F., Lerouge T., Thibault C., Metzger D., Chambon P., Losson R. (2007) Nat. Genet. 39, 1500–1506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ikeda K., Orimo A., Higashi Y., Muramatsu M., Inoue S. (2000) FEBS Lett. 472, 9–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hasegawa N., Iwashita T., Asai N., Murakami H., Iwata Y., Isomura T., Goto H., Hayakawa T., Takahashi M. (1996) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 225, 627–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Horn E. J., Albor A., Liu Y., El-Hizawi S., Vanderbeek G. E., Babcock M., Bowden G. T., Hennings H., Lozano G., Weinberg W. C., Kulesz-Martin M. (2004) Carcinogenesis 25, 157–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Joazeiro C. A., Weissman A. M. (2000) Cell 102, 549–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Meroni G., Diez-Roux G. (2005) Bioessays 27, 1147–1157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Balastik M., Ferraguti F., Pires-da Silva A., Lee T. H., Alvarez-Bolado G., Lu K. P., Gruss P. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 12016–12021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Niikura T., Hashimoto Y., Tajima H., Ishizaka M., Yamagishi Y., Kawasumi M., Nawa M., Terashita K., Aiso S., Nishimoto I. (2003) Eur. J. Neurosci. 17, 1150–1158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tuoc T. C., Stoykova A. (2008) Genes Dev. 22, 1972–1986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lerner M., Corcoran M., Cepeda D., Nielsen M. L., Zubarev R., Pontén F., Uhlén M., Hober S., Grandér D., Sangfelt O. (2007) Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 1670–1682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Trockenbacher A., Suckow V., Foerster J., Winter J., Krauss S., Ropers H. H., Schneider R., Schweiger S. (2001) Nat. Genet. 29, 287–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Takahata M., Bohgaki M., Tsukiyama T., Kondo T., Asaka M., Hatakeyama S. (2008) Mol. Immunol. 45, 2045–2054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Eldin P., Papon L., Oteiza A., Brocchi E., Lawson T. G., Mechti N. (2009) J. Gen Virol 90, 536–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Urano T., Saito T., Tsukui T., Fujita M., Hosoi T., Muramatsu M., Ouchi Y., Inoue S. (2002) Nature 417, 871–875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gack M. U., Shin Y. C., Joo C. H., Urano T., Liang C., Sun L., Takeuchi O., Akira S., Chen Z., Inoue S., Jung J. U. (2007) Nature 446, 916–920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kudryashova E., Kudryashov D., Kramerova I., Spencer M. J. (2005) J. Mol. Biol. 354, 413–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Albor A., El-Hizawi S., Horn E. J., Laederich M., Frosk P., Wrogemann K., Kulesz-Martin M. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 25850–25866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Locke M., Tinsley C. L., Benson M. A., Blake D. J. (2009) Hum. Mol. Genet. 18, 2344–2358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schwamborn J. C., Berezikov E., Knoblich J. A. (2009) Cell 136, 913–925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chen D., Gould C., Garza R., Gao T., Hampton R. Y., Newton A. C. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 33776–33787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bodine S. C., Latres E., Baumhueter S., Lai V. K., Nunez L., Clarke B. A., Poueymirou W. T., Panaro F. J., Na E., Dharmarajan K., Pan Z. Q., Valenzuela D. M., DeChiara T. M., Stitt T. N., Yancopoulos G. D., Glass D. J. (2001) Science 294, 1704–1708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhang H. G., Wang J., Yang X., Hsu H. C., Mountz J. D. (2004) Oncogene 23, 2009–2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schimmer A. D., Dalili S., Batey R. A., Riedl S. J. (2006) Cell Death Differ. 13, 179–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vucic D., Fairbrother W. J. (2007) Clin. Cancer Res. 13, 5995–6000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kim J. H., Kim J., Kim D. H., Ryu G. H., Bae S. H., Seo Y. S. (2004) Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 2287–2297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tan P., Fuchs S. Y., Chen A., Wu K., Gomez C., Ronai Z., Pan Z. Q. (1999) Mol. Cell 3, 527–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zetterqvist O., Ragnarsson U., Humble E., Berglund L., Engström L. (1976) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 70, 696–703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Quignon F., De Bels F., Koken M., Feunteun J., Ameisen J. C., de Thé H. (1998) Nat. Genet. 20, 259–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dho S. H., Kwon K. S. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 31902–31908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kimura F., Suzu S., Nakamura Y., Nakata Y., Yamada M., Kuwada N., Matsumura T., Yamashita T., Ikeda T., Sato K., Motoyoshi K. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 25046–25054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lee S. S., Fu N. Y., Sukumaran S. K., Wan K. F., Wan Q., Yu V. C. (2009) Exp. Cell Res. 315, 1313–1325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Shyu H. W., Hsu S. H., Hsieh-Li H. M., Li H. (2003) Exp. Cell Res. 287, 301–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chu Z. L., McKinsey T. A., Liu L., Gentry J. J., Malim M. H., Ballard D. W. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 10057–10062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Stehlik C., de Martin R., Kumabashiri I., Schmid J. A., Binder B. R., Lipp J. (1998) J. Exp. Med. 188, 211–216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wang C. Y., Mayo M. W., Korneluk R. G., Goeddel D. V., Baldwin A. S., Jr. (1998) Science 281, 1680–1683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Micheau O., Lens S., Gaide O., Alevizopoulos K., Tschopp J. (2001) Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 5299–5305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Catz S. D., Johnson J. L. (2001) Oncogene 20, 7342–7351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dempsey P. W., Doyle S. E., He J. Q., Cheng G. (2003) Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 14, 193–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yang Q. H., Du C. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 16963–16970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yang Y., Fang S., Jensen J. P., Weissman A. M., Ashwell J. D. (2000) Science 288, 874–877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Li J., Feng Q., Kim J. M., Schneiderman D., Liston P., Li M., Vanderhyden B., Faught W., Fung M. F., Senterman M., Korneluk R. G., Tsang B. K. (2001) Endocrinology 142, 370–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Silke J., Kratina T., Chu D., Ekert P. G., Day C. L., Pakusch M., Huang D. C., Vaux D. L. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 16182–16187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Harlin H., Reffey S. B., Duckett C. S., Lindsten T., Thompson C. B. (2001) Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 3604–3608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Liston P., Fong W. G., Kelly N. L., Toji S., Miyazaki T., Conte D., Tamai K., Craig C. G., McBurney M. W., Korneluk R. G. (2001) Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 128–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Du C., Fang M., Li Y., Li L., Wang X. (2000) Cell 102, 33–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Verhagen A. M., Ekert P. G., Pakusch M., Silke J., Connolly L. M., Reid G. E., Moritz R. L., Simpson R. J., Vaux D. L. (2000) Cell 102, 43–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Suzuki Y., Imai Y., Nakayama H., Takahashi K., Takio K., Takahashi R. (2001) Mol. Cell 8, 613–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Yang Q. H., Church-Hajduk R., Ren J., Newton M. L., Du C. (2003) Genes Dev. 17, 1487–1496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Baud V., Karin M. (2001) Trends Cell Biol. 11, 372–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Deveraux Q. L., Takahashi R., Salvesen G. S., Reed J. C. (1997) Nature 388, 300–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kano S., Miyajima N., Fukuda S., Hatakeyama S. (2008) Cancer Res. 68, 5572–5580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Frank D. J., Edgar B. A., Roth M. B. (2002) Development 129, 399–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.