Abstract

Objective

To examine the impact of implementation of the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education's (ACPE's) Standards 2007 on pharmacy students’ preparation for their first advanced pharmacy practice experience (APPE).

Design

The doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) curriculum was altered to include introductory pharmacy practice experiences (IPPE), second-year therapeutics, classroom integration of practice experiences, more biomedical sciences, an electronic portfolio system, life-long learning exercises, and additional content based on Appendix B of Standards 2007. Curricular outcomes and the assessment plan also were revised based on Standards 2007.

Assessment

To evaluate the impact of these changes to the curriculum, faculty members rated 9 behaviors of students observed during the third week of their first APPE and compared their scores with those of students who were evaluated in 2004 before the curriculum had been revised. Students completing the revised curriculum performed all 9 behaviors more often and had a better average score than students evaluated in 2004.

Conclusion

Curricular revisions implemented to address ACPE Standards 2007 were associated with positive clinical behaviors in students beginning their experiential education.

Keywords: Standards 2007, accreditation, assessment, curriculum, Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education, advanced pharmacy practice experience

INTRODUCTION

The Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education's standards were revised in 2007 based on influences within the profession, including reports from the Institute of Medicine, Center for the Advancement of Pharmaceutical Education (CAPE) outcomes 2004, Medicare Modernization Act (medication therapy management), and the Joint Commission of Pharmacy Practitioners’ vision of pharmacy practice.1 Standards 2007 focuses on practice competencies, interprofessional work, program assessment, and lifelong learning skills.1 Operationalizing these principles involves approaches such as portfolios and IPPEs. Standards 2007 requires that IPPEs make up 5% of the curriculum, which equates to approximately 300 contact hours. The Standards specifically states “The introductory pharmacy practice experiences should begin early in the curriculum, be interfaced with didactic course work that provides an introduction to the profession, and continue in a progressive manner leading to entry into the advanced pharmacy practice experiences.”1 The literature contains examples of the positive impact of select aspects (eg, IPPEs,2-11 portfolios,12-13 assessment14) of Standards 2007, but not the full effect of curricular changes in response to Standards 2007.

This study compared students’ preparedness for their first APPE after completing the first 3 years of a curriculum revised to fully address Standards 2007 with that of a group of students who completed the curriculum before the revisions were implemented.

DESIGN

The pharmacy curriculum at South Dakota State University includes 2 years of prepharmacy courses, followed by 4 years of pharmacy courses. Students can earn a bachelor of science degree in pharmaceutical sciences at the end of the second professional year.

Up until 2005, students in the program had limited experiences in several key elements of Standards 2007. To address this, the college's curricular outcomes were redesigned and approved in 2005 to include additional aspects of public health and wellness and emphasis on taking responsibility for patient's medication management.1

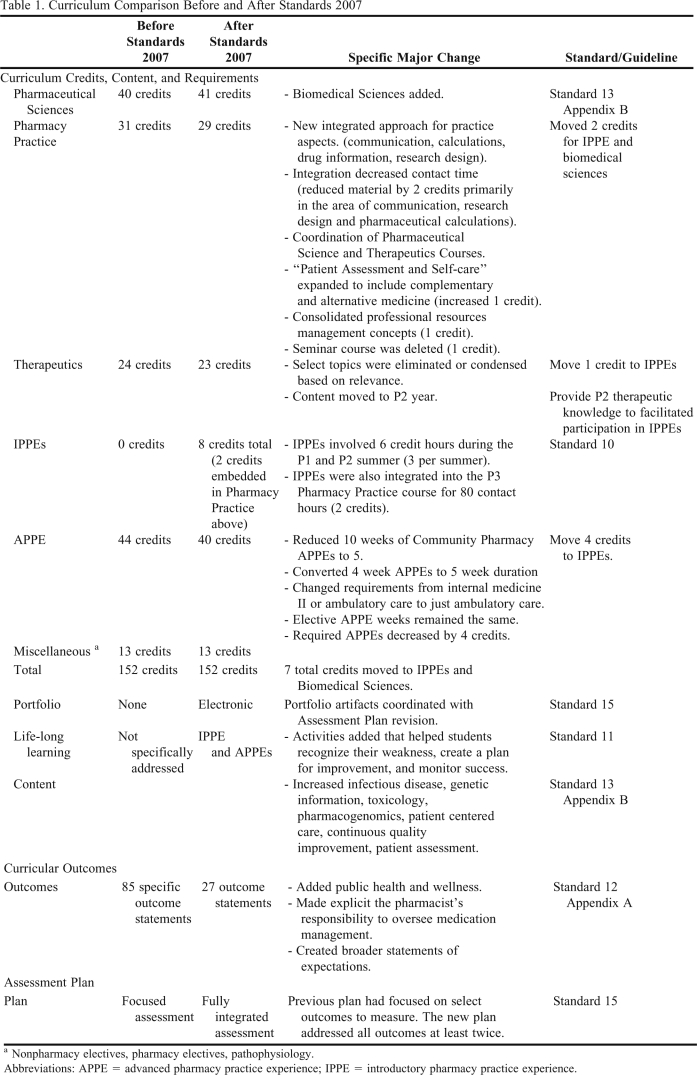

Over the next 2 years, the college worked to modify the curriculum and implement curricular changes to comply with Standards 2007. Two areas were addressed: curricular design (ie, credits, content, teaching methods) and assessment. From the standpoint of curricular design, the addition of the IPPEs marked the most significant change based on the number of hours affected. The second most significant change was movement of therapeutics lecture hours into the second year of the curriculum because all 24 credit hours had previously been in the third year. Other changes involved more integration of pharmacy practice experiences in a 6-course sequence (eg, communications, drug information, research design); an increase in pharmaceutical science credits due to the addition of biomedical sciences content; implementation of an electronic portfolio system; lifelong learning exercises in the experiential component; coordination of content between pharmaceutical science and therapeutics courses; and revision of content to include all elements in Appendix B of Standards 2007 (increased emphasis on infectious disease, genetic information, toxicology, pharmacogenomics, increased patient centered care, continuous quality improvement, and patient assessment). A comparison of the curriculum before and after implementation of Standards 2007 is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Curriculum Comparison Before and After Standards 2007

Nonpharmacy electives, pharmacy electives, pathophysiology.

Abbreviations: APPE = advanced pharmacy practice experience; IPPE = introductory pharmacy practice experience.

Standards 2007 also contains a more robust assessment standard so changes were made to address this aspect as well.1 The college's assessment plan was revised from a plan containing 10 unique evaluation tools to a plan with 12 unique evaluation tools (eg, prepare and dispense; medication management) and 26 separate evaluations (ie, some tools were used more than once). The new plan allowed for all outcomes to be measured at least twice, while the previous plan focused only on a few select outcomes of concern.

EVALUATION AND ASSESSMENT

Students in the graduating class of 2011, the first to complete the entire revised curriculum, were evaluated in 2010 by full-time faculty members at the beginning of their APPEs. The evaluation was done during the first APPE to avoid significant learning that would occur during subsequent APPEs. The evaluation was not conducted until the third week of the APPE to allow the faculty members adequate time to assess the students’ performance.

The evaluation tool completed by the faculty members contained 9 statements (2 about researching a problem, 1 about sharing knowledge, 5 about solving drug-related problems, 1 about prompting to complete the task). Statements were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = always to 5 = never. This was considered ordinal data since each response indicated a corresponding percentage of better or worse performance. For example, each decrease of 1 on the scale indicated a 20% improvement in performance (5 being “never” and 1 being “always” or 100% of the time). The tool was reviewed by a panel of faculty members to ensure that the items reflected relevant attributes and that the scale used to measure them was appropriate.

The comparator group was the graduates of 2005, who completed the curriculum prior to the implementation of Standards 2007. These students were evaluated by faculty members during the third week of their APPE experience in 2004 to determine their level of preparation.

Data were compared via descriptive statistics and a 2-tailed, unpaired t test, assuming unequal variance as appropriate for the data using Excel. Data also were evaluated using chi-square for nominal analysis (except for comparison of number of students, which was examined via Fisher's exact test). The South Dakota State University Institutional Review Board gave approval for this project.

Only students whose first APPE was precepted by a faculty member were evaluated and included in this study. This constituted 43% of the class in 2004 (25 of 58 students) and 41% of the class in 2010 (28 of 68 students). Twenty-three (89%) of 25 students whose first APPE was directed by a faculty member were evaluated in 2004 (the other 2 students’ evaluations were not completed by a faculty member). In 2010, all students whose first APPE was with a faculty member were evaluated (100%). In 2004, 13 faculty members evaluated 23 students, and in 2010, 14 faculty members evaluated 28 students. In the 2 years of the study (2004 and 2010), 19 faculty members evaluated 1 to 3 students in 1 or both years. Each faculty member typically precepted 14 students per year. In 2004, most of the evaluated students were assigned to an internal medicine APPE (52%), with the next largest percentages of students assigned to a pediatrics APPE (13%) or an ambulatory care APPE (13%). In 2010, most of the evaluated students were assigned to an internal medicine APPE (46%) with the next largest percentages of students assigned to an ambulatory care APPE (29%) or pediatrics APPE (21%). All of these APPEs had similarly high levels of routine daily interactions between the faculty and student while managing patients’ medication therapy.

As for differences in admission characteristics, the admitting class of 2001 (2004 sample) had a significantly lower mean grade point average than the admitting class of 2007 (2010 sample) (3.6 and 3.8, respectively, p < 0.001). However, there were no significant differences between the 2 groups with respect to American College Testing (ACT) scores (24.8 and 26.1, respectively, p = 0.13), age (20.9 and 21.2 years, respectively, p = 0.13), and percent of students with a previous degree (8% and 18%, respectively, p = 0.42).

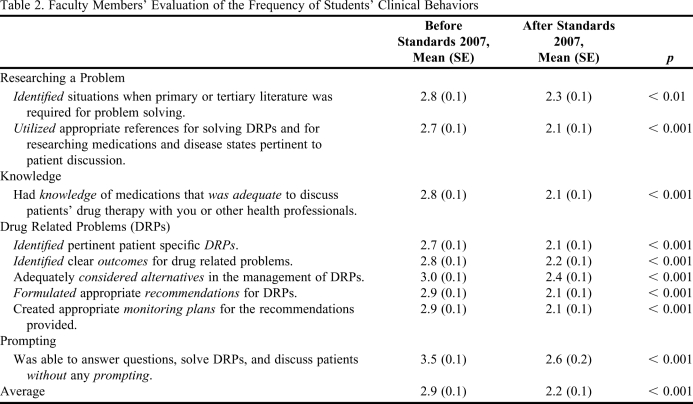

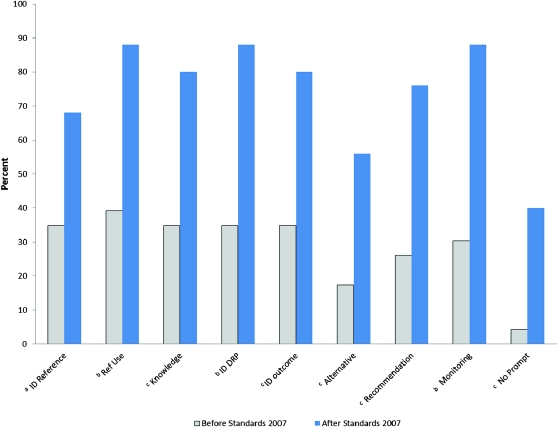

Faculty members’ average evaluation score for the 2010 group was significantly lower than the average score given to the 2004 group (2.2 vs. 2.9, p < 0.001). The differences in average scores were significant for all 9 items as shown in Table 2. The percentage of students in the 2010 group who exhibited the clinical behaviors “usually” or “always” was significantly greater than the percentage of students in the 2004 group (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Faculty Members’ Evaluation of the Frequency of Students’ Clinical Behaviors

Scores based on a Likert scale: 1 = always, 2 = usually, 3 = half the time, 4 = infrequently, 5 = never

Figure 1.

Percent of students perceived to “usually” or “always” do the behavior (a p < 0.05; b p < 0.001; c p < 0.01).

DISCUSSION

Standards 2007 is intended to foster future practitioners who can provide effective patient care in collaborative settings.1 The vision statement for 2015 provided by the Joint Commission of Pharmacy Practice states “Pharmacists will be the health care professionals responsible for providing patient care that ensures optimal medication therapy outcomes.”15 This involves students having the appropriate knowledge and skills and using these in interactions with other health care providers.1 The first APPE provided an excellent opportunity to evaluate students’ preparation to practice these types of skills after completing the first 3 years of the curriculum.

Overall, the curricular changes led to an increase in the students’ positive clinical behaviors based on the faculty members’ perceptions. In addition, students’ scores improved significantly in all 9 areas evaluated, suggesting that students in the 2010 group were more prepared to participate in APPEs after completing 3 years of training under the revised curriculum. This study did not examine whether students were more competent at the completion of the program. Perhaps students were able to achieve similar frequencies of clinical behaviors by the end of the APPEs under either curriculum. Additional studies are needed to examine this aspect.

Literature is available on the impact of select aspects of Standards 2007. For example, IPPEs have been evaluated via surveys and written assignments and noted to have a positive impact on achieving outcomes, providing patient care, and altering attitudes or behaviors (eg, confidence, professionalism).2-11 Similarly, portfolios12,13 and assessment plans14 have been evaluated. However, a longitudinal examination of the impact of curricular revisions to address accreditation standards has not been completed.

This study sought to examine the impact of a significant curricular revision and as such required 6 years between the previous curriculum and implementation of the revised curriculum. From 2004 to 2010, 3 faculty members who participated in the 2004 evaluations were no longer with the college and 3 new faculty members participated in 2010. Because of these faculty changes and first APPE assignments, only 8 of the 19 participating faculty members evaluated students in both years of the study, which may have impacted reliability. Faculty members were aware that the survey was being used to evaluate curriculum effectiveness and this may have influenced their responses. However, substantial time had elapsed between the 2 evaluations and previous ratings likely would have been forgotten. Student admission characteristics were significantly different in terms of grade point average but not in other areas (ACT scores or age). This may have influenced the students’ performance on the first APPE. Factors outside of the curriculum design changes also may have influenced the results. For example, faculty changes occurred during this timeframe and may have altered instructional effectiveness as well. Physical facilities also were different for the 2004 and 2010 groups. The 2010 students were in temporary facilities during their P2 year. Faculty members thought this would have had a negative effect on the students’ performance, but this was not the case. Because the characteristics of the baseline curriculum influenced the impact created by curricular revisions to address Standards 2007, results would vary if this study were performed at another college or school. However, this study does provide insight into the potential impact of the described curricular revisions.

CONCLUSIONS

Students’ performance in their first APPE improved after curricular changes designed to address Standards 2007 were implemented. The performance evaluation specifically addressed students’ skills/knowledge in researching a problem, providing drug information, and solving drug- related problems, and whether they required prompting. While this study did not identify specific elements responsible for the change, highlighted curricular changes included implementation of IPPEs, movement of therapeutics content into the P2 year, initiation of an electronic portfolio system, inclusion of life-long learning exercises in the experiential component, integration of material in the pharmacy practice sequence, coordination of content between pharmaceutical science courses and therapeutics, revision of content to include all elements in Appendix B of Standards 2007, outcome revision, and assessment plan redesign. These results support the importance and usefulness of Standards 2007 in facilitating improved student outcomes.

REFERENCES

- 1. American Council on Pharmacy Education Standards 2007. http://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/ACPE_Revised_PharmD_Standards_Adopted_Jan152006.pdf Accessed April 4, 2011.

- 2.Chisholm MA, DiPiro JT, Fagan SC. An innovative introductory pharmacy practice experience model. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67(1):Article 22. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crill CM, Matlock MA, Pinner NA, Self TH. Integration of first- and second-year introductory pharmacy practice experiences. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(3):Article 50. doi: 10.5688/aj730350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dennis VC. Longitudinal student self-assessment in an introductory pharmacy practice experience course. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69(1):Article 1. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mort JR, Johnson TJ, Hedge DD. Impact of an introductory pharmacy practice experience on students’ performance in an advanced practice experience. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(1):Article 11. doi: 10.5688/aj740111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turner CJ, Jarvis C, Altiere R. A patient focused and outcomes-based experiential course for first year pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2000;64:312–319. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turner CJ, Altiere R, Clark L, Dwinnell B, Barton AJ. An interdisciplinary introductory pharmacy practice experience course. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(1):Article 10. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turner CJ, Altiere R, Clark L, Maffeo C, Valdez C. Competency-based introductory pharmacy practice experiential courses. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69(2):Article 21. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turner CJ, Ellis S, Giles J, et al. An introductory pharmacy practice experience emphasizing student-administered vaccinations. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(1):Article 03. doi: 10.5688/aj710103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wuller WR, Luer MS. A sequence of introductory pharmacy practice experiences to address the new standards for experiential learning. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(4):Article 73. doi: 10.5688/aj720473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boyle CJ, Beardsley RS, Morgan JA. Rodriguez de Bittner M. Professionalism: a determining factor in experiential learning. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(2):Article 31. doi: 10.5688/aj710231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Briceland LL, Hamilton RA. Electronic reflective student portfolios to demonstrate achievement of ability-based outcomes during advanced pharmacy practice experiences. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(5):Article 79. doi: 10.5688/aj740579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Plaza CM, Draugalis JR, Slack MK, Skrepnek GH, Sauer KA. Use of reflective portfolios in health sciences education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(2):Article 34. doi: 10.5688/aj710234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farris KB, Demb A, Janke KK, Kelley K, Scott SA. Assessment to transform competency-based curricula. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(8):Article 158. doi: 10.5688/aj7308158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roche VF, Nahata MC, Wells BG, Kerr RA, Draugalis JR, Maine LL. Roadmap to 2015: Preparing competent pharmacists and pharmacy faculty for the future. Combined report of the 2005-06 Argus Commission and the Academic Affairs, Professional Affairs, and Research and Graduate Affairs Committees. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(5):Article S5. [Google Scholar]