Abstract

Ribonuclease P (RNase P) catalyzes the metal-dependent 5′ end maturation of precursor tRNAs (pre-tRNAs). In Bacteria, RNase P is composed of a catalytic RNA (PRNA) and a protein subunit (P protein) necessary for function in vivo. The P protein enhances pre-tRNA affinity, selectivity, and cleavage efficiency, as well as modulates the cation requirement for RNase P function. Bacterial P proteins share little sequence conservation although the protein structures are homologous. Here we combine site-directed mutagenesis, affinity measurements, and single turnover kinetics to demonstrate that two residues (R60 and R62) in the most highly conserved region of the P protein, the RNR motif (R60–R68 in Bacillus subtilis), stabilize PRNA complexes with both P protein (PRNA•P protein) and pre-tRNA (PRNA•P protein•pre-tRNA). Additionally, these data indicate that the RNR motif enhances a metal-stabilized conformational change in RNase P that accompanies substrate binding and is essential for efficient catalysis. Stabilization of this conformational change contributes to both the decreased metal requirement and the enhanced substrate recognition of the RNase P holoenzyme, illuminating the role of the most highly conserved region of P protein in the RNase P reaction pathway.

Keywords: RNase P, ribozyme, tRNA processing, RNA–protein interactions

INTRODUCTION

The maturation of the 5′ end of tRNAs is catalyzed by the metal-dependent ribonucleoprotein complex, ribonuclease P (RNase P). Bacterial RNase P is composed of a large (∼400 nt) catalytic RNA (PRNA) and a single protein (P protein) subunit (Fig. 1A). Although the RNA component alone is capable of catalyzing pre-tRNA cleavage in high salt in vitro, the protein is essential for catalytic activity in vivo (Hsieh et al. 2004; Evans et al. 2006; Gossringer et al. 2006; Smith et al. 2007). In vitro studies indicate that the P protein subunit contributes to numerous facets of RNase P catalysis including substrate and metal affinity and cleavage efficiency (Reich et al. 1988; Crary et al. 1998; Kurz et al. 1998; Sun et al. 2006). For example, P protein enhances kcat/Km for Bacillus subtilis RNase P–catalyzed cleavage by 2000-fold and substrate affinity by 104-fold (Kurz et al. 1998), while the homologous protein subunit of Escherichia coli RNase P increases the cleavage rate constants for some noncanonical pre-tRNA substrates by >900-fold (Sun et al. 2006). Both E. coli and B. subtilis proteins also decrease the concentration of divalent metal ions required for catalysis by RNase P (Gardiner et al. 1985; Kurz et al. 1998; Sun and Harris 2007), perhaps by stabilizing an essential metal-dependent conformational change (Hsieh et al. 2010).

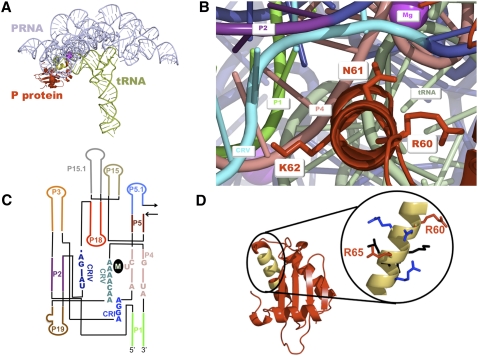

FIGURE 1.

(A) Crystal structure of T. maritima RNase P holoenzyme•tRNA complex (Reiter et al. 2010). (Blue) PRNA; (red) P protein; (green) tRNA. (Yellow) The RNR motif is highlighted on the protein; (magenta ball) the 5′ end of the mature tRNA. (B) Crystal structure of the T. maritima RNase P holoenzyme–tRNA complex (Reiter et al. 2010) with PRNA (dark blue), pre-tRNA (light blue), and P protein (red). The PRNA helices near the RNR motif that comprise the catalytic core of the enzyme are highlighted: P1 (bright green), P2 (purple), P4 (pink), CRV (cyan). The P protein RNR motif residues are displayed as sticks. K62 in the T. maritima corresponds to residue R62 in the B. subtilis holoenzyme. (C) Secondary structure diagram of the B. subtilis PRNA catalytic domain. (M) The general region where metals have been observed to bind in crystal structures of the PRNA (Kazantsev et al. 2009) and RNase P holoenzyme (Reiter et al. 2010). (D) Crystal structure of the B. subtilis RNase P protein (Stams et al. 1998) is shown on the left in red with the RNR motif highlighted in yellow. The RNR motif is enlarged and the residues are color-coded according to their level of conservation (Jovanovic et al. 2002) (red, 100% conservation; blue, 75%–88% conservation; and black, <75% conservation).

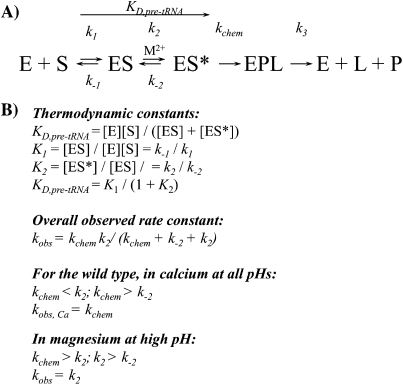

The kinetic mechanism for bacterial RNase P is presented in Scheme 1. In this mechanism, RNase P holoenzyme undergoes a two-step binding process in which substrate association (ES) is followed by a metal-stabilized conformational change (ES*) prior to substrate cleavage (Hsieh and Fierke 2009; Hsieh et al. 2010). Substrate association is rapid and nearly diffusion-controlled (Hsieh and Fierke 2009), and the cleavage of the 5′ leader (L) is essentially irreversible. For wild-type RNase P, the conformational change step is slower than cleavage at high pH and saturating magnesium (Hsieh and Fierke 2009). However, the cleavage rate constant is decreased by lowering the pH or substituting Ca(II) for Mg(II) (Smith et al. 1992) and becomes slower than the conformational change under these conditions (Scheme 1; Smith et al. 1992; Hsieh and Fierke 2009). The potential contribution of interactions between the P protein and PRNA to stabilizing this conformational change has not yet been elucidated.

SCHEME 1.

The structures of several bacterial RNase P proteins have been solved by X-ray crystallography or NMR spectroscopy (Stams et al. 1998; Spitzfaden et al. 2000; Kazantsev et al. 2003). These structures reveal that bacterial RNase P proteins share a fold and structure similar to that of the prototypical B. subtilis protein, with an overall αβββαβα topology and two RNA binding regions (central cleft and RNR motif) (Fig. 1; Stams et al. 1998; Spitzfaden et al. 2000; Kazantsev et al. 2003). The central cleft is formed by the central β-sheet and an α-helix (Stams et al. 1998). Time-resolved FRET (trFRET), affinity cleavage, cross-linking, structure variation, and crystallographic data provide evidence that the central cleft interacts with the 5′ leader of pre-tRNA to enhance substrate recruitment and discrimination (Crary et al. 1998; Kurz et al. 1998; Rueda et al. 2005; Niranjanakumari et al. 2007; Koutmou et al. 2010; Reiter et al. 2010; Sun et al. 2010). The second region of the protein identified as potentially important for RNA binding is the α-helix of an unusual left-handed βαβ crossover connection between parallel β-strands of the central cleft. The α-helix portion of this region is termed the RNR motif because the first three residues are Arg-Asn-Arg (Fig. 1B). Although bacterial RNase P proteins are required in vivo and are structurally homologous, they have strikingly little sequence similarity; only 14 residues exhibit >67% conservation (Jovanovic et al. 2002). Six of these conserved residues are located in the RNR motif (R60, N61, R62, K64, R65, and R68), making it the most highly conserved region of bacterial P proteins (Fig. 1D; Jovanovic et al. 2002).

Recently the first crystal structure of a bacterial RNase P holoenzyme (PRNA•P protein complex) was solved to ∼4 Å resolution in the presence and absence of tRNA and 5′ leader (Fig. 1A; Reiter et al. 2010). The overall architecture of the Thermotoga maritima RNase P holoenzyme structure is strikingly similar to previous low-resolution models of the B. subtilis and Bacillus stearothermophilus enzymes derived from biochemical data (Buck et al. 2005b; Niranjanakumari et al. 2007). In the crystal structure, the P protein contacts the catalytic domain of PRNA at the interface of helices P2/P3, one side of helix P15, and the conserved regions CR-IV and CR-V (Fig. 1A,C; Reiter et al. 2010). In the structure of the RNaseP•tRNA•leader complex, the leader directly contacts the protein central cleft, consistent with cross-linking, time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer, and binding studies of P protein–substrate interactions in B. subtilis and E. coli RNase P (Crary et al. 1998; Niranjanakumari et al. 1998b; Rueda et al. 2005; Sun et al. 2006; Koutmou et al. 2010). Additionally, together with biochemical evidence the recent X-ray data indicate that the RNR motif of the P protein in the RNase P•pre-tRNA complex is positioned near helices P2–P4 of PRNA and both the 5′ leader and 3′ end of pre-tRNA (Niranjanakumari et al. 2007; Reiter et al. 2010).

The apparent proximity of the highly conserved RNR motif to functionally important regions of PRNA and pre-tRNA suggests that it may play an important role in RNase P catalysis. In vivo studies of E. coli RNase P with mutations in the RNR motif indicate that these mutations moderately affect catalysis of pre-tRNATyr cleavage, and severely disrupt the maturation of p4.5S RNA, a non-pre-tRNA substrate (Gopalan et al. 1997a). Recent in vitro studies have shown that substitution of alanine for side chains in the B. subtilis RNR motif (R60–R65) decreases the affinity of RNase P for both pre-tRNAAsp and tRNAAsp (Koutmou et al. 2010). Furthermore, structure-probing studies suggest that interactions between the RNR motif and PRNA are important for stabilizing the formation of the holoenzyme for both E. coli and B. subtilis RNase P (Gopalan et al. 1997a,b; Stams et al. 1998; Niranjanakumari et al. 2007; Koutmou et al. 2010). However, the mechanism by which the RNR motif enhances catalytic activity and substrate recognition remains unclear. To investigate the role of the RNR motif in B. subtilis RNase P function, we evaluated the effects of mutations in this region on holoenzyme stability, substrate affinity, and the kinetics of pre-tRNA binding and cleavage. These data demonstrate that two positively charged residues (R60 and R62) in the RNR motif stabilize the holoenzyme complex and enhance the affinity of RNase P for pre-tRNAAsp. Furthermore, interactions between PRNA and the side chain of R60 stabilize both the initial encounter complex formed after pre-tRNA association (ES) and the subsequent metal-stabilized active conformer (ES*), while the side chain of R62 specifically enhances the ES* complex (Scheme 1). Stabilization of this conformational change contributes to both the decreased metal requirement and the enhanced substrate recognition of the RNase P holoenzyme.

RESULTS

P protein residues R60 and R62 stabilize the formation of the B. subtilis holoenzyme

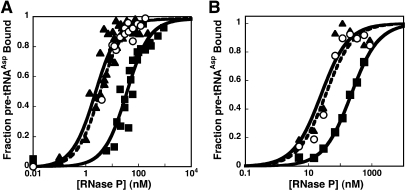

The formation and stability of the RNase P holoenzyme are vital to enzyme function in vivo. However, the precise protein•RNA interactions important for holoenzyme stability have not been evaluated. Interestingly, the RNase P protein is natively unfolded; the three-dimensional structure is stabilized by the addition of anions (Henkels et al. 2001). Both the T. maritima holoenzyme X-ray structure and cross-linking and affinity cleavage data indicate that the highly conserved RNR motif of P protein is located near the PRNA catalytic core (Fig. 1A,B; Buck et al. 2005b; Niranjanakumari et al. 2007; Reiter et al. 2010). To assess the importance of the residues in the RNR motif for holoenzyme complex stability, the affinities of PRNA for the wild-type protein and the R60A, R62A, K64A, R65A, and R68C protein mutants were measured using a previously described magnetocapture binding assay with standardized buffer conditions that stabilize the folded structure of both the PRNA and P protein components (Table 1; Day-Storms et al. 2004). Of the RNR motif residues evaluated, only the R60A and R62A protein mutations decrease the affinity of PRNA for P protein significantly (>20-fold) compared to wild type (Fig. 2A; Table 1). Therefore, the first two arginines in the RNR motif play an important role in stabilizing the RNase P holoenzyme complex.

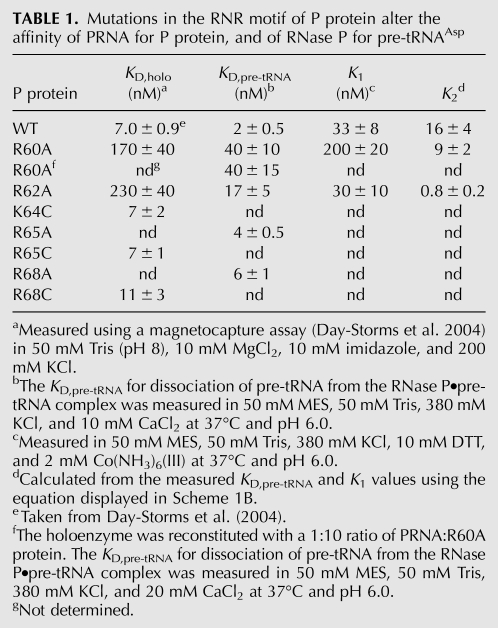

TABLE 1.

Mutations in the RNR motif of P protein alter the affinity of PRNA for P protein, and of RNase P for pre-tRNAAsp

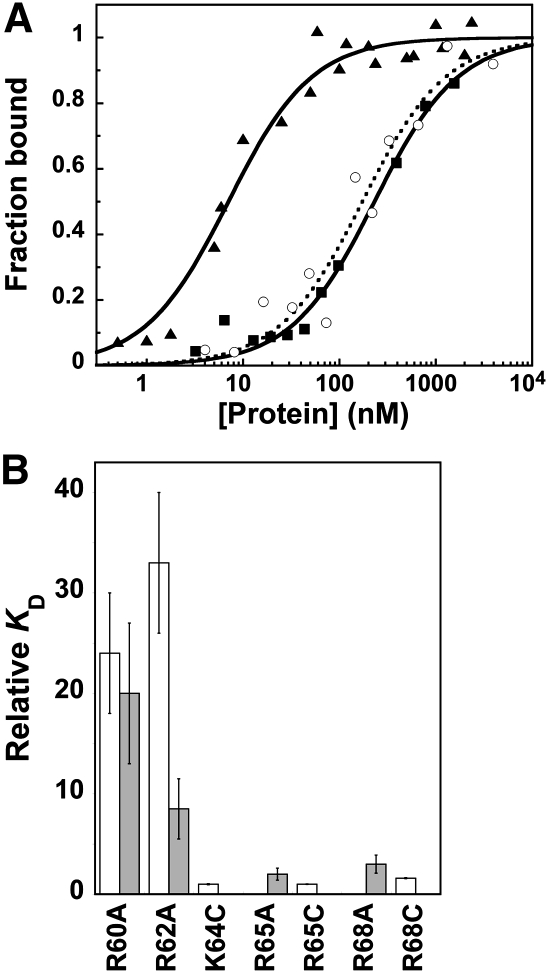

FIGURE 2.

(A) Binding of P protein to PRNA. Wild-type data are displayed in solid triangles (solid line), R60A in open circles (dashed line), and R62A in solid squares (filled line). (B) Relative affinities of PRNA for RNR P protein mutants (white bars; KD,holo,mutant/KD,holo,wild-type) and RNase P holoenzymes reconstituted with RNR motif protein mutants for pre-tRNAAsp (gray bars; KD,pre-tRNA,mutant/KD,pre-tRNA,wild-type).

RNR motif enhances the affinity of RNase P for pre-tRNA

The P protein subunit of B. subtilis RNase P enhances substrate affinity and discrimination; the RNase P holoenzyme has 104-fold greater affinity for pre-tRNA than PRNA alone at comparable solution conditions (Crary et al. 1998; Kurz et al. 1998). To determine if the RNR motif contributes to this enhanced affinity, we measured the pre-tRNA affinity (in 10 mM CaCl2) of four RNase P mutants in which alanine replaces one of the amino acids in the RNR motif (Fig. 2B; Table 1). The cleavage reaction in calcium at pH 6.0 is sufficiently slow that substrate binding can be measured with minimal cleavage of pre-tRNA (Smith and Pace 1993; Kurz et al. 1998). Due to differences in the experimental methods, the buffer conditions used to measure pre-tRNA affinity are significantly different from those used to measure the affinity of PRNA for P protein.5 To demonstrate that the holoenzyme complex is stably formed under the conditions used for measuring pre-tRNA, we established that the value of KD,pre-tRNA is not dependent on the concentration of the P protein. For example, for the R60A mutant, the KD,pre-tRNA values are identical within experimental error when the PRNA-to-P protein ratio is varied from 1:1 to 1:10. The KD,pre-tRNA values indicate that the R65A and R68A P protein mutations decrease the pre-tRNA affinity of RNase P by less than threefold at saturating calcium, suggesting that these side chains provide little energetic contribution to substrate affinity and therefore likely do not interact directly with the substrate. In contrast, the R60A and R62A P protein mutations decrease the pre-tRNA affinity of RNase P by at least eightfold (Fig. 3A; Table 1). Since KD,pre-tRNA reflects a combination of thermodynamic constants for the first two steps in the kinetic mechanism (Scheme 1), these side chains in the RNR motif stabilize the formation of the enzyme•substrate complex by enhancing the initial substrate association complex (ES), and/or the conformational change step following pre-tRNA association (ES*) (Scheme 1).

FIGURE 3.

(A) Mutations in the RNR motif of RNase P decrease the affinity of pre-tRNAAsp. RNase P-bound and free pre-tRNAAsp were separated using a gel filtration centrifuge column. RNase P was reconstituted with wild-type (triangles, solid line), R60A (squares, solid line), or R68A (circles, dotted line) P protein. The bound 32P-labeled pre-tRNAAsp (≤0.2 nM) was measured as a function of RNase P concentration in 50 mM MES, 50 mM Tris, 380 mM KCl, and 10 mM CaCl2 (pH 6.0, 37°C). The values of KD,pre-tRNA, determined from a fit of a binding isotherm to these data, are listed in Table 1. (B) Measurement of the effects of mutations on the stability of the initial RNase P•pre-tRNA (ES) complex. The affinity of wild-type (triangles, solid line), R60A (squares, solid line), and R62A (circles, dotted line) RNase P for pre-tRNA was measured as described in A except that the buffer contained 50 mM MES, 50 mM Tris, 200 mM KCl, 2 mM Co(NH3)6(III), and 10 mM DTT (pH 6.0, 37°C). Under these conditions, the ES conformer predominates. The values of K1, determined from a fit of a binding isotherm to these data, are listed in Table 1.

R60 contributes to pre-tRNA affinity in the initial ES complex

To examine whether the disruption of pre-tRNA affinity caused by the R60A and R62A mutations can be attributed primarily to effects on the stability of the initial enzyme–substrate complex (ES) or the new conformer formed following substrate binding (ES*), we assessed the thermodynamics of the formation of the ES complex, K1 (Scheme 1), for wild-type and mutant RNase P enzymes. Previous studies established that in the presence of 2 mM cobalt hexammine [Co(NH3)6(III)] and no divalent cations, the RNase P holoenzyme properly folds and binds pre-tRNA in the ES conformation (Hsieh et al. 2010). Divalent cations (i.e., calcium or magnesium) both stabilize the ES* conformer and activate catalysis (Hsieh et al. 2010). Therefore, the pre-tRNA affinity in the ES complex (K1) was measured from fluorescence titrations performed in the presence of Co(NH3)6(III) without added divalent cations (Hsieh et al. 2010). Compared to wild-type RNase P, the R60A mutation raises the value of K1 by sixfold (Fig. 3B; Table 1), suggesting that this side chain stabilizes the formation of the initial ES complex. Nevertheless, the sixfold stabilization of the ES complex does not fully account for the 20-fold decrease in pre-tRNA affinity observed in calcium buffer (Table 1). Conversely, the R62A mutation has no effect on the value of the dissociation constant K1, indicating that the R62 side chain does not stabilize the ES complex. However, this mutation causes a ninefold decrease in the value of KD,pre-tRNA (Table 1). The values of K2, the equilibrium constant for the conformational change, can be calculated from the values of KD,pre-tRNA and K1 (Scheme 1B) as: 16 ± 4 (wild-type), 9 ± 2 (R60A), and 0.8 ± 0.2 (R62A). Therefore, the side chains of R60 and R62 stabilize the formation of the ES* conformer relative to ES by ≤2-fold and 20-fold, respectively. Thus, while the side chain of R60 stabilizes both the ES and ES* complexes, the side chain of R62 specifically stabilizes the ES* complex.

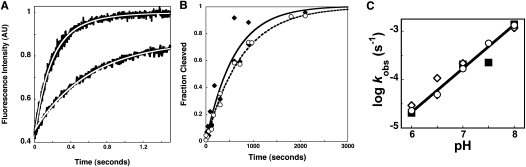

To further analyze the role of the R62 side chain on the conformational change, the kinetics for formation of the ES* conformer were measured. In this experiment, RNase P is mixed with fluorescein-labeled pre-tRNA (Fl-pre-tRNA) at saturating calcium concentrations, and the formation of ES and ES* is observed from the time-dependent changes in fluorescence. The initial pseudo-first-order binding step is rapid (kobs1 ∼ 2 sec−1), consistent with the value previously measured for the fluorescence transient upon mixing substrate with wild-type RNase P [∼1.8 sec−1 for 0.2 μM wild-type RNase P at 25°C and 10 mM Ca(II)] (Fig. 4A; Hsieh and Fierke 2009). The measured rate constants for the conformational change (k2 + k−2) in the RNase P•Fl-pre-tRNA complex formed with the wild-type and R62A P protein are 2.9 ± 0.6 sec−1 and 0.65 ± 0.07 sec−1, respectively, in 20 mM Ca(II) at pH 6 and 37°C (Fig. 4A). Using these data and the calculated value of K2, the rate constant for formation of ES* from ES (k2) is estimated at 2.6 sec−1 and 0.2 sec−1 for wild-type and R62A P protein, respectively, while the reverse rate constant (k−2 ∼ 0.3 sec−1) is virtually unchanged. Therefore, the side chain of R62, deleted in the R62A mutant, increases the rate constant for the formation of ES* from ES as well as stabilizes the ES* conformer.

FIGURE 4.

The effect of mutations in P protein on ES* formation and RNase P-catalyzed pre-tRNA cleavage in calcium. (A) Stopped-flow experiments measuring changes in the fluorescence of Fl-pre-tRNAAsp (30 nM) with a 5-nt-long 5′ leader upon mixing with wild-type (0.25 μM) or R62A RNase P (0.215 μM) in 20 mM CaCl2 (380 mM KCl, 50 mM MES, and 50 mM Tris at 37°C, pH 6). As previously described (Hsieh and Fierke 2009), the first and second phases correspond to the formation of the ES complex and ES* conformer, respectively. Equation 6 was fit to the data. (B) Time courses for cleavage of 32P-labeled pre-tRNA (≤1 nM) catalyzed by RNase P (400 nM) reconstituted with WT (diamonds, solid line) or R62A (circles, dashed line) P protein under single turnover conditions in 10 mM CaCl2 (pH 8) in buffer (50 mM MES, 50 mM Tris, 200 mM KCl at 37°C). (C) pH dependence of single turnover rate constants catalyzed by WT (circles, solid line), R60A (squares), and R62A (diamonds) RNase P in 10 mM CaCl2 (pH 6–8) and buffer.

RNR mutations do not alter the kinetics of pre-tRNA cleavage (kchem)

To evaluate whether the side chains of the RNR motif specifically stabilize the transition state for pre-tRNA cleavage (kchem), we measured the single turnover rate constant for cleavage activated by calcium ions (Fig. 4B,C). For wild-type RNase P, the observed rate constants for product formation in calcium (kobs,Ca) under single turnover conditions exhibit a roughly log-linear dependence on pH (slope = 0.8 ± 0.02), primarily reflecting the rate constant of the cleavage step (kchem), because kchem (kobs < 2.9 × 10−5 sec−1) at pH 6 is less than the value of the conformational change rate constant under these conditions (Scheme 1; Fig. 4). The single turnover rate constants for pre-tRNA cleavage catalyzed by the R60A and R62A RNase P mutants measured in 10 mM calcium are comparable to the wild-type values at pH values 5–8 with a similar log-linear pH dependence (slope = 0.77 ± 0.02 [R60A] and 0.90 ± 0.01 [R62A]) (Fig. 4C). These data indicate that the R60 and R62 side chains do not directly stabilize the transition state of the cleavage reaction catalyzed by RNase P.

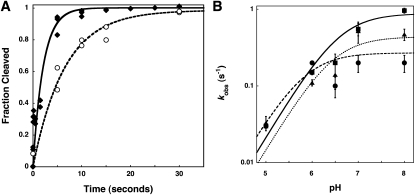

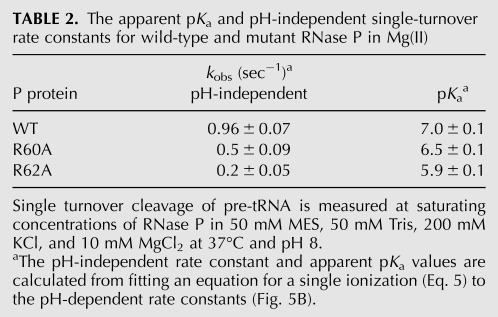

RNR motif mutations alter RNase P–catalyzed cleavage in Mg(II)

The cleavage step (kchem) catalyzed by wild-type RNase P is >10,000-fold faster in magnesium compared to calcium (Smith et al. 1992; Kurz et al. 1998). In magnesium, the rate-limiting step for cleavage under single turnover conditions depends on the pH; the pH-dependent hydrolytic step is rate-limiting at low pH (<6), while the pH-independent conformational change step becomes rate-limiting at high pH (>8) (Hsieh and Fierke 2009). To evaluate if the RNR motif alters the kinetics of the conformational change step in magnesium, the pH dependence of RNase P–catalyzed cleavage under single turnover conditions was measured for wild-type, R60A, and R62A RNase P in 10 mM MgCl2 (Fig. 5; Table 2). As previously observed, at low pH, the wild-type single turnover rate constant decreases linearly with the concentration of protons, consistent with rate-limiting cleavage; therefore, the value of kobs reflects kchem at saturating RNase P concentrations (Fig. 5B; Hsieh and Fierke 2009). At high pH, the value of kobs becomes independent of pH, and these data can be analyzed as an apparent ionization. However, this apparent pKa actually reflects a change in rate-limiting steps, and the value of the observed pKa of 6.6 ± 0.05 reflects the pH at which the apparent rate constants for these two steps are equal (Hsieh and Fierke 2009).

FIGURE 5.

Mutations in P protein affect RNase P-catalyzed cleavage of pre-tRNA in magnesium. (A) Time courses for single turnover cleavage of pre-tRNAAsp catalyzed by R60A RNase P at pH 6.0 (circles, dashed line) and pH 8.0 (diamonds, solid line) in 10 mM MgCl2 and buffer. (B) pH dependence of single turnover rate constants catalyzed by wild-type (squares, solid line), R60A (triangles, dotted line), and R62A (circles, dashed line) RNase P in 10 mM MgCl2 (pH 5–8) and buffer. The values of the pH-independent single turnover rate constant and observed pKa, determined from a fit of a single ionization to these data, are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

The apparent pKa and pH-independent single-turnover rate constants for wild-type and mutant RNase P in Mg(II)

For the R60A and R62A mutations in RNase P, the single turnover rate constant at pH 5, where hydrolysis is the rate-limiting step, is comparable to that of the wild-type enzyme. These data confirm that the RNR motif of RNase P confers little specific stabilization of the hydrolytic transition state. However, these mutations decrease the value of the pH-independent rate constant measured at high pH by twofold to fivefold where the conformational change step (k2) is rate-limiting, slightly smaller than the decrease in the rate constant for the conformational change measured in calcium. This decrease in the value of the rate constant for the conformational change (k2) for R60A and R62A is also reflected in a decrease in the value of the observed pKa for single turnover cleavage; the pKa values measured for the reactions catalyzed by the R60A and R62A mutants are lowered by as much as 1 pH unit to 6.5 ± 0.1 and 5.9 ± 0.1, respectively (Fig. 5B; Table 2). Therefore, the side chains of R62 and R60, to a lesser extent, stabilize the ES* complex and enhance the kinetics of the formation of ES* in both Mg(II) and Ca(II).

DISCUSSION

RNase P proteins, although functionally and structurally homologous, share very little sequence conservation. A comparison of RNase P protein sequences revealed that only ∼10% of the amino acids in bacterial P proteins have conserved identities (Jovanovic et al. 2002). Almost half of these residues (R60, N61, R62, K64, R65, R68 in B. subtilis) are found on a single α-helix termed the RNR motif (Fig. 1D). Two of these positions, R60 and R65, are invariant in all bacterial RNase P proteins, and a third position, R68, is conserved >80% of the time. Mutation of the RNR motif disrupts RNase P function in vivo, yet the exact structural and functional roles of the RNR motif are not well understood (Gopalan et al. 1997a; Jovanovic et al. 2002). To identify the functional importance of these conserved residues, we investigated the contributions of RNR motif residues to the kinetics and thermodynamics of B. subtilis RNase P. These data demonstrate that the RNR motif stabilizes the PRNA•protein and RNase P•pre-tRNA complexes and influences a conformational change in the enzyme prior to catalysis.

RNR motif stabilizes holoenzyme formation and substrate affinity

Photo-cross-linker or affinity cleavage reagents covalently attached to P protein at residues in the RNR motif (R60, N61, R62, K64, R65, and R68) were previously reported to cleave or cross-link to the PRNA subunit, suggesting that the RNR motif might form a portion of the RNA–protein subunit interface (Niranjanakumari et al. 2007). Structure-probing studies in B. subtilis also place R60 near (within 15 Å) helix P4 (nucleotides 48–50) and R62 near helices P3 (nucleotide 43) and P19 (nucleotides 366 and 367), regions that are located in the catalytic domain. These biochemical data agree well with the recent crystal structure of the T. maritima RNase P holoenzyme, which reveals that six RNR motif residues (N61, R62, K64, R65, L66, R68 in B. subtilis numbering) contact PRNA residues in helices P2, P3, and conserved regions (CR) I, IV, and V (Fig. 1A,C; Reiter et al. 2010). Although R60 does not directly contact PRNA in the crystal structure, it is still within 15 Å of the PRNA catalytic core, as suggested by structure-probing studies. Consistent with this, the side chains of R60 and R62 each stabilize the holoenzyme by ∼2 kcal/mol at moderate salt concentrations (Table 1). The holoenzyme crystal structure suggests that the effect of the R60A mutation on PRNA•protein complex stability, while significant, is indirect. The destabilization of the holoenzyme complex reconstituted with R60A P protein may result from alteration of the RNR motif helix structure that leads to a disruption in direct PRNA–P protein contacts with other RNR motif residues (e.g., N61, R62, K64, R65, L66, or R68).

The R60A and R62A mutations also decrease the affinity of RNase P for pre-tRNA by 1.8 and 1.3 kcal/mol,6 respectively, either via loss of a direct contact or by altering the structure of the RNase P•pre-tRNA complex, while mutations in other residues in the RNR motif decrease substrate affinity by <0.7 kcal/mol. While the effect of the R60A mutation on pre-tRNA affinity is comparable to previous data (Koutmou et al. 2010), the negligible twofold perturbation of pre-tRNA affinity by the R65A mutation in the presence of saturating 10 mM Ca(II) (Table 1) is significantly smaller than the 14-fold decrease previously observed in subsaturating concentrations of Ca(II) [2–3.5 mM Ca(II)] (Koutmou et al. 2010). Since the value of KD,pre-tRNA is cooperatively dependent on the concentration of Ca(II) (nH ∼ 5, K1/2 = 4.5 mM) (Koutmou et al. 2010), this difference in affinity is likely explained by the R65A mutation altering the affinity or cooperativity for Ca(II) (Crary et al. 1998; Koutmou et al. 2010).

The KD,pre-tRNA values measured in calcium reflect a combination of equilibria for the first two mechanistic steps shown in Scheme 1: pre-tRNA association with RNase P followed by a metal-stabilized conformational change. Previous kinetic and thermodynamic studies of RNase P in 2 mM Co(NH3)6(III) demonstrated that the holoenzyme can form stably and bind substrate, but that the subsequent conformational change is not favored under these conditions (Scheme 1; Hsieh et al. 2010). Affinity measurements in Co(NH3)6(III) suggest that the main effect of the side chain of R60 on pre-tRNA affinity is to stabilize formation of the initial E•S complex relative to E and S, K1, by 1.1 kcal/mol (Fig. 3; Table 1) with modest additional stabilization of ES*. In contrast, the R62A mutation destabilizes the formation of the ES* conformer relative to ES by 1.8 kcal/mol (Table 1), indicating that the R62 side chain has more favorable interactions in the ES* relative to the ES complex.

Structure-probing studies indicate that side chains of both R60 and R62 are in close proximity to the cleavage site and/or the 5′ leader of pre-tRNA in the RNase P•pre-tRNA complex (Buck et al. 2005b; Niranjanakumari et al. 2007), suggesting the possibility of a direct contact with the substrate rather than an indirect effect caused by disrupting the structure of RNase P. The R60A mutation also decreases the affinity of mature tRNA (Koutmou et al. 2010), suggesting that this side chain makes a contact with the tRNA moiety in the initial ES complex that is maintained in the ES* complex. Consistent with this, the T. maritima RNase P holoenzyme•tRNA structure indicates that R60 directly contacts tRNA (Reiter et al. 2010). Conversely, although R62 is located near the substrate, the crystal structure does not reveal any precise interactions between pre-tRNA and R62. There are two possible explanations for this observation: (1) The stabilization of pre-tRNA binding by R62 is indirect, either by disrupting P protein or PRNA structure; or (2) the holoenzyme•tRNA structure is not in the correct conformation for R62•pre-tRNA contacts to be observed. A recent structural model derived from time-resolved FRET (trFRET) data of the P protein•substrate interactions in the ES and ES* complexes supports the latter observation, as these data suggest that the pre-tRNA 5′ leader moves toward the R62 side chain in the ES* conformer (Hsieh et al. 2010), consistent with the stabilization of ES* by this residue. In summary, the side chains of R60 and R62 in P protein stabilize both holoenzyme formation and the active conformer of the RNase P•pre-tRNA complex.

RNR motif enhances conformational kinetics

Single turnover measurements in calcium and in magnesium at low pH demonstrate that the side chains of R60 and R62 do not alter the observed cleavage rate constants (Fig. 4C; Table 2) and therefore do not stabilize the cleavage reaction (kchem) (Scheme 1). This is not unexpected given that PRNA retains catalytic activity in high concentrations of magnesium in the absence of the P protein (Guerrier-Takada et al. 1983). However, the R60A and R62A mutations decrease the values of the single turnover rate constants in magnesium at high pH by twofold to fivefold; under these conditions, the rate constant for the formation of ES* (k2) becomes kinetically significant as the rate constant for cleavage is faster than the reverse conformational change (k3 > k−2) (Fig. 5B; Table 2). The decreased rate constant for the conformational change in the RNR motif mutants leads to a lowering of the apparent pKa in magnesium, shifting the pKa by as much as a full pH unit. Furthermore, direct measurements of the rate constant for the conformational change in Ca(II) demonstrate that the R62 side chain enhances the rate of formation of the ES* complex by as much as 10-fold. All of the data are consistent with the side chain of R62, and R60 to a lesser extent, enhancing the rate constant for the conformational change that occurs after substrate binding and prior to cleavage in the RNase P•pre-tRNA complex. Therefore, interactions with these side chains must occur in the transition state for the conformational change and be maintained in the ES* complex.

The question remains: How does this portion of the P protein stabilize the conformational change in the RNase P•pre-tRNA complex? Previous melting, binding, and folding studies of E. coli and B. subtilis RNase P suggest that bacterial proteins stabilize local PRNA structure (Buck et al. 2005a). Footprinting studies of the E. coli and B. stearothermophilus PRNAs complexed with E. coli, B. stearothermophilus, or B. subtilis protein revealed that all three bacterial proteins protect the same PRNA region, including nucleotides in helices P3 and P4 (Buck et al. 2005b). Consistent with this, affinity cleavage data indicate that the RNR motif is in close proximity to PRNA helices P2, P3, P4, and P19 (Niranjanakumari et al. 2007). Binding of P protein has also been shown to influence the conformation of E. coli and B. stearothermophilus PRNA in the regions flanking helix P4 (Buck et al. 2005a). Furthermore, the ES-to-ES* conformational change is also stabilized by an inner-sphere, divalent cation that binds to ES* with high affinity (Hsieh et al. 2010). Two metal ions associate with PRNA at helix P4 in the crystal structure of the T. maritima RNase P holoenzyme, and it is possible that one of these metals is the inner-sphere ion responsible for stabilizing the ES* conformer. R62 interacts with PRNA at helix P2 stem, where it connects to CR IV. This contact is near the site where the two metal ions are observed (Fig. 1C). Potentially, a model could be envisioned in which the R62 side chain stabilizes the ES* conformer by stabilizing local PRNA structure required for metal association. Several examples of arginines stabilizing RNA conformation are available, including arginine residues in the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) Tat and Rev proteins that stabilize conformations of HIV RNA (Tan and Frankel 1992, 1994; Hermann and Patel 2000).

Stabilization of the ES* complex by the RNR motif of P protein contributes to substrate affinity (Fig. 2; Table 1). This interaction may also contribute to substrate recognition since the conformational change is proposed to act as a proofreading step to identify cognate substrates (Hsieh et al. 2010). Thus, the work presented here reveals the discrete contributions of the RNR motif residues R60 and R62 in the RNase P function: to facilitate holoenzyme formation, enhance substrate binding, and stabilize the active conformer (ES*). In particular, the observation that the RNR motif stabilizes the active RNase P conformer provides an important rationalization for the requirement of this noncatalytic subunit in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of RNA and protein

All RNAs were transcribed from linearized plasmid digested with a restriction enzyme as templates for in vitro transcription catalyzed by T7 RNA polymerase (Milligan and Uhlenbeck 1989; Beebe and Fierke 1994). The B. subtilis P RNAs used in the magnetocapture assays and the B. subtilis pre-tRNAAsp containing a 5-nt leader (GACAU-tRNA) used in the kinetic assays were prepared using excess guanosine to form RNA transcripts containing a 5′ hydroxyl that were subsequently labeled at the 5′ terminus with 32P-γ-ATP (MP Life Technologies) catalyzed by T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs) (Ziehler et al. 2000). All RNAs were purified by electrophoresis on an 8%–12% polyacrylamide denaturing gel (Kurz et al. 1998). RNA was eluted into 10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and 500 mM NaCl. Following elution, RNA was washed with >50 volumes of 10 mM Tris and 1 mM EDTA and stored at −20°C. Before use, P RNA and pre-tRNA were denatured by heating for 3 min at 95°C and then refolded for kinetic and thermodynamic assays by adding buffer (50 mM Tris, 50 mM MES, 200–380 mM KCl at pH 6.0), and divalent metal ions (i.e., 10 mM CaCl2 or MgCl2), to the RNA and incubating for >30 min at 37°C.

The wild-type B. subtilis P protein was expressed and purified as previously described (Niranjanakumari et al. 1998a; Day-Storms et al. 2004). Single alanine point mutations were made using megaprimer PCR amplification and were cloned into either pET28b or pET8c vectors (Novagen) (Niranjanakumari et al. 1998a, 2007). The recombinant wild-type and mutant B. subtilis P proteins were expressed in BL21(DE3)pLysS E. coli containing plasmids encoding the variant P proteins grown at 37°C followed by induction by isopropylthio-β-D-galactopyranoside. The protein was purified using CM-Sepharose chromatography, and the concentration was determined by absorbance at 280 nm (ɛ260 = 5120 M−1 cm−1) (Niranjanakumari et al. 1998a).

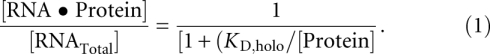

PRNA–P protein KD,holo determination by magnetocapture assay

Trace concentrations of 5′ 32P-end-labeled PRNA were denatured by heating for 3 min at 95°C and were refolded at 25°C in buffer containing 50 mM Tris (pH 8), 10 mM imidazole, 10 mM MgCl2, and 200 mM KCl. Holoenzyme complex was formed by incubating the radiolabeled P RNA with an excess of P protein (0.1 nM–2 μM) for 30 min at 25°C. Magnetic beads (10–20 μL) (QIAGEN) were added, and the solution was agitated for an hour; the PRNA•P protein complex binds to this resin, even without a His-tag on the protein subunit (Day-Storms et al. 2004). An external magnet was used to separate the magnetic beads from the bulk solution, and the bound PRNA was eluted from the beads by incubation in 100 mM EDTA, 2% (v/v) sodium dodecyl sulfate for 5 min at 95°C. The radioactivity in the supernatant (free RNA) and the eluate (bound RNA) was measured by Cerenkov scintillation counting. The fraction bound was determined by ([Protein•RNA]/[RNATotal]) = (cpmeluate − cpmbackground)/(cpmendpoint − cpmbackground), where cpmbackground is the radioactivity bound in the absence of protein and cpmendpoint is that bound at saturating concentrations of protein (Kurz et al. 1998; Day-Storms et al. 2004). Equation 1 was fit to the data using the Kaleidagraph (Synergy Software) curve-fitting program.

|

Measurement of KD,pre-tRNA for pre-tRNAAsp

PRNA and pre-tRNA were folded as described above. After PRNA was folded, a 1.1-fold molar excess of P protein was added, and the solution was incubated for an additional 30 min at 37°C in 50 mM MES, 50 mM Tris, 380 mM KCl, and 10 mM CaCl2 (pH 6.0). Control experiments with ratios of 1:5 and 1:10 PRNA to R60A and R62A P protein were performed, and the data changed less than twofold, demonstrating formation of the holoenzyme.

To measure KD,pre-tRNA, a >10-fold excess of RNase P (0 to 900 nM) was incubated for 5 min with 32P 5′ end-labeled pre-tRNAAsp in the buffer described above at 37°C. The holoenzyme–substrate mixture was loaded onto a pre-packed G-75 Sephadex column, and the unbound substrate was separated from the RNase P-bound substrate via centrifugational gel filtration (Beebe and Fierke 1994; Crary et al. 1998). The fraction of substrate bound ([ES] + [ES*]/[Stotal]) was determined using scintillation counting. A standard binding isotherm was then fit to the data to calculate dissociation constants (Eq. 2).

Fl-pre-tRNA synthesis and labeling

Substrates containing a 5′-monothiophosphate were prepared by in vitro transcription using T7 RNA polymerase in the presence of guanosine 5′ monothiophosphate (GMPS) (4 mM ATP, CTP, UTP, and GMPS; 0.8 mM GTP; 0.1 μg/μL T7 RNA polymerase; 0.1 μg/μL linearized DNA template; 28 mM MgCl2; 1 mM spermidine; 5 mM dithiothreitol; and 50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 8.0, incubated for 4 h at 37°C). Transcription reactions were terminated by addition of 30 mM EDTA, and the RNA was concentrated 10-fold and exchanged into TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.0, 1 mM EDTA) by centrifugal filtration. A 10-fold molar excess of iodoacetamidofluorescein (5-IAF) dissolved in DMSO was added to the pre-tRNA solution and incubated overnight in the dark at 4°C, and the reaction was terminated by addition of 10 mM dithiothreitol or 2-mercaptoethanol. The Fl-pre-tRNAAsp was purified by denaturing gel electrophoresis (15% polyacrylamide, 8 M urea).

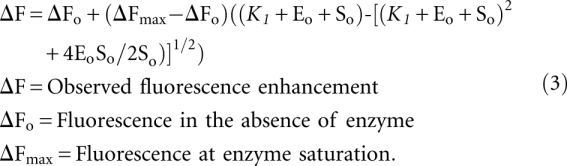

Fluorescence titration measurements of K1

RNase P holoenzyme and pre-tRNA were folded as outlined above for KD,pre-tRNA measurements, except that cobalt hexammine is substituted for calcium in the buffer [50 mM MES, 50 mM Tris, 400 mM KCl, 2 mM Co(NH3)6(III)]. Fl-pre-tRNA (20 nM) was incubated in buffer in a fluorescence cuvette for 5 min at 37°C. Fluorescein was excited at 485 nm, and fluorescent emission was collected at 535 nm. RNase P holoenzyme (0–860 nM) was titrated into the fluorescence cuvette, and the changes in fluorescence were measured. A quadratic binding isotherm, Equation 3 (Rueda et al. 2005), was fit to these data. The values measured under these conditions reflect K1 in Scheme 1.

|

Single turnover experiments

Experiments measuring single turnover cleavage were performed using excess holoenzyme concentrations ([E]/[S] ≫ 5; [E] = 0.4–2 μM; [S] ≤ 0.1 nM) with radiolabeled pre-tRNAAsp at 37°C in either 10 mM CaCl2 or MgCl2, 50 mM MES, 50 mM Tris, and ∼200 mM KCl (pH 5 to 8), with ionic strength maintained at 0.639 with KCl. All reactions were quenched with an equal volume of buffer containing 8 M urea, 100 mM EDTA, and 0.05% (w/v) each of xylene cyanol and bromophenol blue. The 5′ leader product was separated from the pre-tRNA substrate on a 20% denaturing polyacrylamide urea gel. The gels were scanned using a PhosphorImager. All kinetic data were well-described by a single exponential (Eq. 4) (Beebe and Fierke 1994). All time points <3 sec of incubation were measured on a KinTek quench-flow apparatus.

The pKa values in both magnesium and calcium were determined by plotting the single turnover rate constants (kobs) as a function of pH and fitting the following equation to the data:

Stopped-flow fluorescence assays

Stopped-flow assays were run as previously described (Hsieh and Fierke 2009) with 0.215 (R62A) or 0.25 (wild-type) μM RNase P and 50 nM 5′-fluorescein labeled pre-tRNAAsp. The reactions were performed at 37°C in a KinTek stopped-flow spectrometer in 50 mM MES, 50 mM Tris, 180 mM KCl, and 20 mM CaCl2 (at pH 6.0). Equation 6 was fit to the data where A1 and A2 are amplitude terms, k1,obs and k2,obs are rate constants, and C is the value of the starting fluorescence.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM 55387 to C.A.F. and T32 GM08353 to K.S.K.).

Footnotes

Due to the differences in the buffer concentrations, the values for KD,holo and KD,pre-tRNA listed in Table 1 are not directly comparable since both dissociation constants have a significant dependence on the concentration and identity of monovalent and divalent cations and anions (Beebe et al. 1996; Day-Storms et al. 2004; Koutmou et al. 2010).

ΔΔG = −RT ln(KMutant/KWild-type).

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.2742511.

REFERENCES

- Beebe JA, Fierke CA 1994. A kinetic mechanism for cleavage of precursor tRNA(Asp) catalyzed by the RNA component of Bacillus subtilis ribonuclease P. Biochemistry 33: 10294–10304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beebe JA, Kurz JC, Fierke CA 1996. Magnesium ions are required by Bacillus subtilis ribonuclease P RNA for both binding and cleaving precursor tRNAAsp. Biochemistry 35: 10493–10505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck AH, Dalby AB, Poole AW, Kazantsev AV, Pace NR 2005a. Protein activation of a ribozyme: the role of bacterial RNase P protein. EMBO J 24: 3360–3368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck AH, Kazantsev AV, Dalby AB, Pace NR 2005b. Structural perspective on the activation of RNase P RNA by protein. Nat Struct Mol Biol 12: 958–964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crary SM, Niranjanakumari S, Fierke CA 1998. The protein component of Bacillus subtilis ribonuclease P increases catalytic efficiency by enhancing interactions with the 5′ leader sequence of pre-tRNAAsp. Biochemistry 37: 9409–9416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day-Storms JJ, Niranjanakumari S, Fierke CA 2004. Ionic interactions between PRNA and P protein in Bacillus subtilis RNase P characterized using a magnetocapture-based assay. RNA 10: 1595–1608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans D, Marquez SM, Pace NR 2006. RNase P: interface of the RNA and protein worlds. Trends Biochem Sci 31: 333–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner KJ, Marsh TL, Pace NR 1985. Ion dependence of the Bacillus subtilis RNase P reaction. J Biol Chem 260: 5415–5419 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopalan V, Baxevanis AD, Landsman D, Altman S 1997a. Analysis of the functional role of conserved residues in the protein subunit of ribonuclease P from Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol 267: 818–829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopalan V, Golbik R, Schreiber G, Fersht AR, Altman S 1997b. Fluorescence properties of a tryptophan residue in an aromatic core of the protein subunit of ribonuclease P from Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol 267: 765–769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gossringer M, Kretschmer-Kazemi Far R, Hartmann RK 2006. Analysis of RNase P protein (rnpA) expression in Bacillus subtilis utilizing strains with suppressible rnpA expression. J Bacteriol 188: 6816–6823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrier-Takada C, Gardiner K, Marsh T, Pace N, Altman S 1983. The RNA moiety of ribonuclease P is the catalytic subunit of the enzyme. Cell 35: 849–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henkels CH, Kurz JC, Fierke CA, Oas TG 2001. Linked folding and anion binding of the Bacillus subtilis ribonuclease P protein. Biochemistry 40: 2777–2789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann T, Patel DJ 2000. RNA bulges as architectural and recognition motifs. Structure 8: R47–R54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh J, Fierke CA 2009. Conformational change in the Bacillus subtilis RNase P holoenzyme–pre-tRNA complex enhances substrate affinity and limits cleavage rate. RNA 15: 1565–1577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh J, Andrews AJ, Fierke CA 2004. Roles of protein subunits in RNA–protein complexes: Lessons from ribonuclease P. Biopolymers 73: 79–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh J, Koutmou KS, Rueda D, Koutmos M, Walter NG, Fierke CA 2010. A divalent cation stabilizes the active conformation of the B. subtilis RNase P•pre-tRNA complex: A role for an inner-sphere metal ion in RNase P. J Mol Biol 400: 38–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jovanovic M, Sanchez R, Altman S, Gopalan V 2002. Elucidation of structure–function relationships in the protein subunit of bacterial RNase P using a genetic complementation approach. Nucleic Acids Res 30: 5065–5073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazantsev AV, Krivenko AA, Harrington DJ, Carter RJ, Holbrook SR, Adams PD, Pace NR 2003. High-resolution structure of RNase P protein from Thermotoga maritima. Proc Natl Acad Sci 100: 7497–7502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazantsev AV, Krivenko AA, Pace NR 2009. Mapping metal-binding sites in the catalytic domain of bacterial RNase P RNA. RNA 15: 266–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koutmou KS, Zahler NH, Kurz JC, Campbell FE, Harris ME, Fierke CA 2010. Protein–precursor tRNA contact leads to sequence-specific recognition of 5′ leaders by bacterial ribonuclease P. J Mol Biol 396: 195–208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurz JC, Niranjanakumari S, Fierke CA 1998. Protein component of Bacillus subtilis RNase P specifically enhances the affinity for precursor-tRNAAsp. Biochemistry 37: 2393–2400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan JF, Uhlenbeck OC 1989. Determination of RNA–protein contacts using thiophosphate substitutions. Biochemistry 28: 2849–2855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niranjanakumari S, Kurz JC, Fierke CA 1998a. Expression, purification and characterization of the recombinant ribonuclease P protein component from Bacillus subtilis. Nucleic Acids Res 26: 3090–3096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niranjanakumari S, Stams T, Crary SM, Christianson DW, Fierke CA 1998b. Protein component of the ribozyme ribonuclease P alters substrate recognition by directly contacting precursor tRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci 95: 15212–15217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niranjanakumari S, Day-Storms JJ, Ahmed M, Hsieh J, Zahler NH, Venters RA, Fierke CA 2007. Probing the architecture of the B. subtilis RNase P holoenzyme active site by crosslinking and affinity cleavage. RNA 13: 512–535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich C, Olsen GJ, Pace B, Pace NR 1988. Role of the protein moiety of ribonuclease P, a ribonucleoprotein enzyme. Science 239: 178–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter NJ, Osterman A, Torres-Larios A, Swinger KK, Pan T, Mondragon A 2010. Structure of a bacterial ribonuclease P holoenzyme in complex with tRNA. Nature 468: 784–789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueda D, Hsieh J, Day-Storms JJ, Fierke CA, Walter NG 2005. The 5′ leader of precursor tRNAAsp bound to the Bacillus subtilis RNase P holoenzyme has an extended conformation. Biochemistry 44: 16130–16139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D, Pace NR 1993. Multiple magnesium ions in the ribonuclease P reaction mechanism. Biochemistry 32: 5273–5281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D, Burgin AB, Haas ES, Pace NR 1992. Influence of metal ions on the ribonuclease P reaction. Distinguishing substrate binding from catalysis. J Biol Chem 267: 2429–2436 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JK, Hsieh J, Fierke CA 2007. Importance of RNA–protein interactions in bacterial ribonuclease P structure and catalysis. Biopolymers 87: 329–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzfaden C, Nicholson N, Jones JJ, Guth S, Lehr R, Prescott CD, Hegg LA, Eggleston DS 2000. The structure of ribonuclease P protein from Staphylococcus aureus reveals a unique binding site for single-stranded RNA. J Mol Biol 295: 105–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stams T, Niranjanakumari S, Fierke CA, Christianson DW 1998. Ribonuclease P protein structure: Evolutionary origins in the translational apparatus. Science 280: 752–755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Harris ME 2007. Evidence that binding of C5 protein to P RNA enhances ribozyme catalysis by influencing active site metal ion affinity. RNA 13: 1505–1515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Campbell FE, Zahler NH, Harris ME 2006. Evidence that substrate-specific effects of C5 protein lead to uniformity in binding and catalysis by RNase P. EMBO J 25: 3998–4007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Campbell FE, Yandek LE, Harris ME 2010. Binding of C5 protein to P RNA enhances the rate constant for catalysis for P RNA processing of pre-tRNAs lacking a consensus G(+1)/C(+72) pair. J Mol Biol 395: 1019–1037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan R, Frankel AD 1992. Circular dichroism studies suggest that TAR RNA changes conformation upon specific binding of arginine or guanidine. Biochemistry 31: 10288–10294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan R, Frankel AD 1994. Costabilization of peptide and RNA structure in an HIV Rev peptide-RRE complex. Biochemistry 33: 14579–14585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziehler WA, Day JJ, Fierke CA, Engelke DR 2000. Effects of 5′ leader and 3′ trailer structures on pre-tRNA processing by nuclear RNase P. Biochemistry 39: 9909–9916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]