Abstract

BACKGROUND

Standard indicators of quality of care have been developed in the United States. Limited information exists about quality of care in countries with universal health care coverage.

OBJECTIVE

To assess the quality of preventive care and care for cardiovascular risk factors in a country with universal health care coverage.

DESIGN AND PARTICIPANTS

Retrospective cohort of a random sample of 1,002 patients aged 50–80 years followed for 2 years from all Swiss university primary care settings.

MAIN MEASURES

We used indicators derived from RAND’s Quality Assessment Tools. Each indicator was scored by dividing the number of episodes when recommended care was delivered by the number of times patients were eligible for indicators. Aggregate scores were calculated by taking into account the number of eligible patients for each indicator.

KEY RESULTS

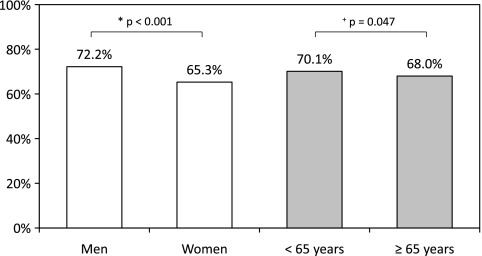

Overall, patients (44% women) received 69% of recommended preventive care, but rates differed by indicators. Indicators assessing annual blood pressure and weight measurements (both 95%) were more likely to be met than indicators assessing smoking cessation counseling (72%), breast (40%) and colon cancer screening (35%; all p < 0.001 for comparisons with blood pressure and weight measurements). Eighty-three percent of patients received the recommended care for cardiovascular risk factors, including >75% for hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes. However, foot examination was performed only in 50% of patients with diabetes. Prevention indicators were more likely to be met in men (72.2% vs 65.3% in women, p < 0.001) and patients <65 years (70.1% vs 68.0% in those ≥65 years, p = 0.047).

CONCLUSIONS

Using standardized tools, these adults received 69% of recommended preventive care and 83% of care for cardiovascular risk factors in Switzerland, a country with universal coverage. Prevention indicator rates were lower for women and the elderly, and for cancer screening. Our study helps pave the way for targeted quality improvement initiatives and broader assessment of health care in Continental Europe.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11606-011-1674-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: quality of health care, insurance coverage, primary health care, primary prevention

BACKGROUND

Standard indicators of the quality of preventive and chronic disease care have been developed and evaluated in the United States.1,2 Using RAND’s Quality Assessment (QA) Tools, a quality assessment system that spans over 30 conditions and prevention, McGlynn et al. found that US adults received 55% of recommended health care services in 12 metropolitan areas.1 In the UK, a systematic performance monitoring was introduced in 2004 coupled with financial incentives,3 the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF).

We have limited information about the quality of preventive care in Continental Europe. Most previous studies on the quality of preventive care in Europe have assessed only a few indicators of quality for many conditions,4 or one condition at a time, such as hypertension5,6 or diabetes.7,8 Thus, we have limited data on the quality of preventive care given to adults in Continental Europe, particularly using standardized tools. In Switzerland, quality of care has been assessed for only a few specific conditions.9–11

The Swiss and US health care systems differ on at least two points. In Switzerland, all patients have universal health care coverage, including adults with low income who receive social aid to cover health care costs, regardless of their age or whether they work. Patients are free to choose their primary care physician (PCP). Second, systematic performance monitoring and annual report cards on quality of care, such as the US Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS),12 and financial incentives to improve quality are not implemented in Switzerland. While this practice is not universal in the US and in Europe, limited data exist on the quality of care in a country without such quality improvement programs.

We therefore sought to assess the quality of care in Switzerland, using indicators adapted from RAND’s QA Tools.1 We focused our study on primary and secondary prevention, and thus assessed the delivery of preventive care and chronic care for cardiovascular risk factors (CVRFs) to 1,002 randomly selected adults from all Swiss university primary care settings.

METHODS

Study Design and Patients

In a retrospective cohort study, we abstracted medical charts from a random sample of patients followed by PCPs in all Swiss university primary care settings (Basel, Geneva, Lausanne and Zürich). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each site. Most of the care was provided by residents in general internal medicine at the end of their postgraduate training (n = 902, 90%), supervised by university attendings, while 100 patients (10%) were followed by university attendings. The random sample was drawn from electronic administrative data of all patients aged 50 to 80 years followed in 2005–2006. We limited our sample to this age group to have a high enough prevalence of examined indicators (e.g., CVRFs, eligibility for cancer screening or influenza immunization). A similar sample size was used in previous studies on quality of care based on chart abstraction.13,14

Among the 1,889 patients in the starting random sample identified from electronic administrative data, 54 charts could not be found, most likely because the patients left the clinical setting for another practice. Compared to included patients, these 54 patients had a similar age (63.5 years vs 64.0, p = 0.65) and proportion of women (35% vs 44%, p = 0.22). Among the 1,835 reviewed medical charts, 591 had <1 year follow-up in the primary care clinic during the review period, 125 patients had no outpatient visit to a PCP during the review period (emergency visits or nurse appointments only), and 117 were followed in a specialized clinic only. We did not include patients who were followed in the clinical setting for <1 year to have adequate time and information to assess provided preventive care. The final sample included 1,002 abstracted medical charts.

Quality Indicators

We selected 37 quality indicators from RAND’s QA Tools1,2 concerning preventive care and the care of CVRFs. This system was previously developed in the US to evaluate the quality of care delivered to adults.15 Briefly, RAND staff physicians reviewed established national guidelines and the medical literature for each condition. Chosen indicators focused on processes of care, because they represent the activities that clinicians control most directly.1 Multispecialty expert panels chose the final RAND indicators using the RAND-UCLA modified Delphi method.16

As our aim was to examine care related to primary and secondary prevention, we selected 37 indicators: 14 for preventive care (physical examination: 3; alcohol: 2; smoking cessation: 5; cancer screening: 2; influenza immunization: 2), 19 for chronic care of three major CVRFs (hypertension: 4; dyslipidemia: 2; diabetes: 13) and 4 for chronic care for cardiovascular disease (Tables 2 and 3, unabridged indicators in Appendix Table 1, available online). The definitions of hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes were adapted from a previous study17 (Appendix Table 2, available online). We did not include preventive care indicators that were not applicable to our local guidelines or PCP settings (e.g., pregnancy follow-up is very rarely performed by PCPs in Switzerland) or that involved information usually not collected in charts in Switzerland or adults aged 50–80 years, or indicators for conditions of low prevalence in our sample (e.g., asthma). Excluded quality indicators are listed at the bottom of Appendix Table 1 (available online). We included indicators on coronary artery disease, as it is the most common cause of death in Switzerland.18

Table 2.

Recommended Preventive Care

| Indicator | Preventive care | Eligible patients no. | Care provided* no. | Care provided % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical examination | ||||

| 1 | Annual blood pressure measurement | 1,002 | 952 | 95.0 (93.5–96.3) |

| 2 | Weight measurement | 1,002 | 952 | 95.0 (93.5–96.3) |

| 3 | Height measurement | 1,002 | 753 | 75.1 (72.4–77.8) |

| Aggregate score for physical examination | 88.4 (87.2–89.5) | |||

| Alcohol consumption counseling | ||||

| 4 | Asked about drinking problem | 1,002 | 671 | 67.0 (64.0–69.9) |

| 5 | Advice to decrease drinking for at-risk or binge drinkers† | 132 | 102 | 77.3 (69.2–84.1) |

| Aggregate score for alcohol consumption counseling | 68.2 (65.4–70.9) | |||

| Smoking cessation counseling | ||||

| 6 | Smoking status documented | 1,002 | 789 | 78.7 (76.1–81.2) |

| 7 | Annual advice to quit smoking | 230 | 165 | 71.7 (65.4–77.5) |

| 8 | Counseling offered to smokers attempting to quit | 77 | 52 | 67.5 (55.9–77.8) |

| 9 | Pharmacotherapy offered to smokers attempting to quit if >10 cigarettes/day | 77 | 37 | 48.1 (36.5–59.7) |

| 10 | Abstinence documented 4 weeks after smoking cessation counseling | 52 | 24 | 46.2 (32.2–60.5) |

| Aggregate score for smoking cessation counseling | 74.2 (71.9–76.4) | |||

| Cancer screening | ||||

| 11 | Screening for colon cancer (aged 50–80)‡ | 984 | 345 | 35.1 (32.1–38.1) |

| 12 | Screening for breast cancer (aged 50–70)‡ | 310 | 125 | 40.3 (34.8–46.0) |

| Aggregate score for cancer screening | 36.3 (33.7–39.0) | |||

| Influenza immunization | ||||

| 13 | Annual influenza vaccine for patients ≥65 years | 426 | 150 | 35.2 (30.7–40.0) |

| 14 | Annual influenza vaccine for immunocompromised patients <65 years§ | 276 | 81 | 29.3 (24.0–35.1) |

| Aggregate score for influenza immunization | 32.9 (29.4–36.5) | |||

| Global aggregate score for Preventive Care | 68.6 (67.6–69.7) | |||

*When care was refused by eligible patients, it was counted as provided care to measure physician-initiated health care. When care was provided less frequently than specified (i.e., once a year instead of twice a year or only once instead of annually), it was counted as unprovided care to measure physician adherence to recommendations

†At-risk drinking was defined as >14 drinks per week for men <65 years or >7 drinks per week for others. Binge drinking was defined as >4 drinks per occasion for men <65 years or >3 drinks for others

‡Patients were excluded from screening because of a prior diagnosis of colon cancer (n = 18) or breast cancer (n = 17)

§Indications for influenza immunization for <65 years: living in a nursing home, chronic cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, renal failure, diabetes, immunosuppression, hemoglobinopathy

Table 3.

Recommended Chronic Care for Cardiovascular Risk Factors

| Indicator | Chronic care for cardiovascular risk factors | Eligible patients no. | Care provided* no. | Care provided % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes | ||||

| 15 | Diabetes documented for patients <75 years | 249 | 241 | 96.8 (93.8–98.6) |

| 16 | Glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) twice a year† | 292 | 210 | 71.9 (66.4–77.0) |

| 17 | Annual eye and visual exam† | 292 | 163 | 55.8 (49.9–61.6) |

| 18 | Cholesterol tests documented | 292 | 285 | 97.6 (95.1–99.0) |

| 19 | Annual proteinuria | 292 | 190 | 65.1 (59.3–70.5) |

| 20 | Foot examination twice a year† | 292 | 147 | 50.3 (44.5–56.2) |

| 21 | Blood pressure documented | 292 | 291 | 99.7 (98.1–100.0) |

| 22 | Follow-up visits twice a year | 292 | 259 | 88.7 (84.5–92.1) |

| 23 | Glucose monitoring for diabetics taking insulin | 103 | 101 | 98.1 (93.2–99.8) |

| 24 | Dietary and exercise counseling for newly diagnosed diabetics | 58 | 57 | 98.3 (90.8–100.0) |

| 25 | Oral hypoglycemics for type 2 diabetics who have failed dietary therapy (HbA1c ≥7% after 6 months) | 75 | 67 | 89.3 (80.1–95.3) |

| 26 | Insulin offered to type 2 diabetics who have failed oral hypoglycemics (HbA1c ≥7% with two oral drugs after 6 months) | 75 | 54 | 72.0 (60.4–81.8) |

| 27 | Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker‡ offered within 3 months after noting proteinuria or microalbuminuria§ | 96 | 85 | 88.5 (80.4–94.1) |

| Aggregate score for diabetes | 79.6 (78.1–81.1) | |||

| Hypertension | ||||

| 28 | Diagnosis of hypertension when 3 separate visits with blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg | 639 | 614 | 96.1 (94.3–97.5) |

| 29 | Lifestyle modification for hypertension† | 753 | 485 | 64.4 (60.9–67.8) |

| 30 | Annual visit for hypertensive patients | 753 | 751 | 99.7 (99.0–100.0) |

| 31 | Pharmacotherapy or lifestyle modification for uncontrolled hypertension (≥140/90 mmHg over 6 months)† | 502 | 389 | 77.5 (73.6–81.1) |

| Aggregate score for hypertension | 84.6 (83.2–85.9) | |||

| Dyslipidemia | ||||

| 32 | Two cholesterol tests before start of therapy | 174 | 154 | 88.5 (82.8–92.8) |

| 33 | Cholesterol tests if heart disease and no pharmacological therapy | 138 | 134 | 97.1 (92.7–99.2) |

| Aggregate score for dyslipidemia | 92.3 (88.8–95.0) | |||

| Global aggregate score for care for cardiovascular risk factors | 82.6 (81.6–83.6) | |||

| Chronic care for cardiovascular diseases‖ | ||||

| 34 | Aspirin for coronary artery disease | 152 | 144 | 94.7 (89.9–97.7) |

| 35 | Beta-blockers after acute myocardial infarction | 60 | 49 | 81.7 (69.6–90.5) |

| 36 | Antiplatelet therapy after stroke or transient ischemic attack | 74 | 66 | 89.2 (79.8–95.2) |

| 37 | Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin-receptor blocker‡ for heart failure with ejection fraction <40% | 47 | 42 | 89.4 (76.9–96.5) |

*When care was refused by eligible patients, it was counted as provided care to measure physician-initiated health care. When care was provided less frequently than specified (i.e., once a year instead of twice a year, or only once instead of annually), it was counted as unprovided care to measure physician adherence to recommendations

†These indicators with lower inter-rater reliability (kappa <0.6) were excluded in a sensitivity analysis

‡Angiotensin-receptor blocker was added according to Joint National Committee 7th guidelines38

§Microalbuminuria was added according to American Diabetes Association guidelines39

‖When care was contraindicated, the patient was not counted as eligible, thus reducing the denominator

Chart Abstraction

A chart review was performed for data abstraction, similar to previous studies with direct abstraction from medical charts.1,13,14,19 A data abstraction form was created to assess the 37 selected indicators for chronic and preventive care derived from RAND’s QA Tools1 (Appendix Table 2, available online). Other abstracted covariates (demographics, chronic comorbid conditions) were based on a chart abstraction form from the TRIAD study19 (Translating Research into Action for Diabetes), a study about the quality of diabetes care in the US. Nine medical students were centrally trained at one site (Lausanne) for data abstraction from medical charts in each Swiss university primary care setting and then entered the data with EpiData software (version 3.1, EpiData Association, Denmark).

To assess inter-rater reliability, we repeated the chart abstraction on a random sample of patients (n = 45, to detect a statistically significant kappa20) at one site (Lausanne). Inter-rater reliability using the kappa statistic ranged from 0.66 to 1.0 for the main quality indicators, consistent with a previous study using a similar method.19 The inter-rater reliability was lower (0.35 to 0.57) for some indicators that were prone to interpretation (e.g., lifestyle modifications for hypertension) or those that required a specific recommended frequency over the 2 years (e.g., eye exam annually, foot exam and HbA1c twice a year for diabetics). As a sensitivity analysis, we tested whether the exclusion of indicators with lower inter-rater reliability (kappa <0.6) or indicators that are gender-specific (breast cancer screening) changed the global aggregate scores.

Statistical Analysis

For each selected indicator of preventive care and chronic care for CVRFs, we calculated the percentage of provided recommended care by dividing all episodes in which recommended care was delivered by the number of times patients were eligible for indicators (overall percentage method21). When care was refused by eligible patients, it was counted as provided care to measure physician-initiated care. The results were presented as percentages with 95% binomial exact confidence intervals (CI). To summarize the selected indicators, we calculated aggregate scores of quality of care among the different categories of prevention (physical examination, counseling, screening and immunization) and a global aggregate score for preventive care. All these aggregate scores were calculated by taking into account the number of eligible patients for each selected indicator. The same method of calculation was used to obtain the aggregate scores of chronic care for hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes, and a global aggregate score for chronic care for CVRFs, summarizing care for these three conditions.

We used generalized estimating equation (GEE) binomial models to compare differences in rates of recommended preventive care and to assess the association between demographic characteristics (age, gender) and the proportion of provided care. GEE models were used to account for correlation of multiple measurements for the same patient and for different numbers of eligible patients for each recommended preventive care. To account for clustering by the four sites, we treated each primary care center as a fixed effect. For all statistical analyses, Stata software (version 10.1, Stata Corp., College Station, TX) was used.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Patients

The mean age of our sample was 63.5 years with 44% women and 51% married patients (Table 1). Thirty-eight percent of patients were retired and 29% employed. During the 2-year review period, the median number of outpatient visits was 10 (range 2–63, SD 6.5). The prevalence of CVRFs was 75% for hypertension, 62% for dyslipidemia and 29% for diabetes. Twenty-three percent of the participants were current smokers, 36% had a prior cardiovascular disease, 22% a psychiatric disorder and 20% a chronic pulmonary disease.

Table 1.

Patients' Characteristics: Random Sample of 1,002 Adults Aged 50–80 Years in All Swiss University Primary Care Settings

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 63.5 (8.3) |

| Range, minimum – maximum | 50–80 |

| Women, no. (%) | 445 (44.4) |

| Civil status, no. (%) | |

| Married | 506 (51.0) |

| Divorced, separated | 233 (23.5) |

| Single | 151 (15.2) |

| Widow/-er | 103 (10.4) |

| Occupation, no. (%) | |

| Retired | 372 (37.9) |

| Employed | 285 (29.0) |

| At home or in education | 115 (11.7) |

| Social aid | 109 (11.1) |

| Unemployed or other | 101 (10.3) |

| Number of outpatient visits over 2 years | |

| Median (interquartile range) | 10 (7–15) |

| Range, minimum – maximum | 2–63 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | |

| Hypertension*, no. (%) | 753 (75.2) |

| Dyslipidemia*, no. (%) | 622 (62.1) |

| Diabetes*, no. (%) | 292 (29.1) |

| Family history of early CHD†, no. (%) | 99 (9.9) |

| Smoking status at baseline‡, no. (%) | |

| Former smokers | 177 (17.7) |

| Current smokers | 230 (23.0) |

| Comorbid conditions | |

| Cardiovascular disease§, no. (%) | 364 (36.3) |

| Chronic pulmonary disease‖, no. (%) | 201 (20.1) |

| Non-metastatic solid cancer¶, no. (%) | 133 (13.3) |

| Metastatic solid cancer, no. (%) | 16 (1.6) |

| Hematological cancer, no. (%) | 10 (1.0) |

| Dementia, no. (%) | 24 (2.4) |

| Psychiatric disorders#, no. (%) | 287 (28.6) |

*For criteria of dyslipidemia, hypertension and diabetes, see Appendix Table 2 (available online)

†Early coronary heart disease (CHD) defined as a CHD event in male relatives <55 years or in female relatives <65 years

‡Smoking status defined as: former smoker = stopped smoking ≥6 months before baseline; current smoker = smoking at baseline or stopped <6 months before baseline

§History of transient ischemic attack, cerebral vascular accident, coronary artery disease, angina, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure or peripheral vascular disease

‖Classification based on Charlson index37: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, sleep apnea syndrome, sarcoidosis, pulmonary hypertension, bronchiectases, interstitial pulmonary disease or global respiratory insufficiency

¶Includes prostate, colorectal, breast, lung, kidney, urothelial, gynecological and other types of cancer in the last 5 years

#Classification based on Charlson index37: depression, psychotic disorder and bipolar disorder

Analysis of Delivered Care

Tables 2 and 3 show the selected indicators, the aggregate scores, the number of eligible patients for each indicator and the number of patients who were provided such care. Patients received 69% of recommended preventive care, but this result differed by specific indicators. Indicators assessing annual blood pressure and weight measurements (both 95%) were more likely to be met than indicators assessing alcohol consumption counseling (77%), smoking cessation counseling (72%), breast cancer (40%) and colon cancer screening (35%; all p < 0.001 for comparisons with blood pressure and weight measurements). The level of performance according to the particular aggregate score ranged from 88% for physical examination to 33% for influenza immunization.

Eighty-three percent of patients received the recommended care for CVRFs, including >75% for hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes. However, glycosylated hemoglobin was measured at least twice a year in 72% of diabetics, and foot examination was performed twice a year in 50%. Daily aspirin was recommended to 95% of patients with coronary artery disease (n = 152). Among the 60 patients with previous myocardial infarction, beta-blockers were prescribed to 82% of patients. Eighty-nine percent of patients received antiplatelet therapy after stroke or transient ischemic attack (n = 74) and 89% of patients with heart failure (n = 47) an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or an angiotensin-receptor blocker.

In multivariate analyses adjusted for age, gender and center as a fixed effect, prevention indicators were more likely to be met in men (72.2% vs 65.3% in women, p < 0.001) and patients <65 years (70.1% vs 68.0% in those ≥65 years, p = 0.047, Fig. 1). Removing the only gender-specific indicator (i.e., breast cancer screening) from this analysis yielded similar results.

Figure 1.

Preventive care according to gender and age. Legend: Preventive care according to gender (white columns, p value adjusted for age and center as a fixed effect) and age (grey columns, p value adjusted for gender and center as a fixed effect).

Adherence rates to chronic care for CVRFs did not differ according to age and gender (both p > 0.10). Sensitivity analyses excluding two indicators for hypertension and three indicators for diabetes, with lower inter-rater reliability (see Methods), yielded a higher aggregate score for chronic care of CVRFs (93% vs 83%). Results for aggregate scores were similar between patients followed by residents and university attendings.

Comparison with Other Settings

The rates of recommended preventive care and chronic care for CVRFs in this study were compared with similar indicators from US HEDIS 2006 results,12 when available (Table 4). Overall, quality of care did not differ between the two settings for CVRFs and smoking cessation. The major differences were for influenza immunization and breast and colorectal cancer screening, which were performed far more frequently in the US than in Switzerland.

Table 4.

Comparison with Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS)*

| Indicator | Switzerland 2005–2006 | United States* 2006 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking cessation counseling | |||

| 7 | Annual advice to quit | 71.7 | 73.8 |

| 8 | Pharmacotherapy offered to smokers | 48.1 | 43.9 |

| Diabetes | |||

| 16 | HbA1c screening† | 71.9 | 87.5 |

| 17 | Annual eye exam screening | 55.8 | 54.7 |

| 18 | LDL-cholesterol screening | 97.6 | 83.4 |

| 19 | Monitoring nephropathy‡ | 65.1 | 79.7 |

| Cardiovascular disease | |||

| 35 | Beta blockers a year after heart attack | 81.7 | 72.5 |

| Cancer screening | |||

| 11 | Colorectal cancer | 35.2 | 54.5 |

| 12 | Breast cancer§ | 39.7 | 72.0 |

| Influenza immunization | |||

| 13 | All patients >65 years‖ | 35.2 | 70.3 |

| 14 | Potentially immunocompromised <65 years | 29.3 | 45.6 |

*Selection of similar indicators on 2006 data from HEDIS,12 when available

†HbA1c screening twice a year in Switzerland, but once a year in the US

‡Recommended screening for proteinuria in Switzerland, medical attention for kidney disease in the US

§HEDIS US 2005 rates were reported here as recommended screening age (50–70 years) was the same as in Switzerland, instead of 40–70 years (since 2006 in the US)

‖HEDIS US 2005 rates were reported here because such Medicare data were not available in 2006

DISCUSSION

Using standardized indicators developed in the US,1 we found that adults in university primary care settings received 69% of recommended preventive care and 83% of chronic care for CVRFs in Switzerland, a country with universal health care coverage but no systematic performance monitoring. Women and the elderly had lower receipt of recommended preventive care, and rates of cancer screening were low (<40%).

In the US, several studies have been conducted about the quality of care. McGlynn et al.1 found that US adults received about 55% of recommended care. The comparison of our results with the McGlynn study was limited because that study reported data from 1998–2000. The comparison with US HEDIS 2006 results12 yielded a mixed picture (Table 4). Interestingly, although the methods of measurement and the studied populations differed somewhat between HEDIS12 and our study, quality of care in Swiss university primary care settings was comparable to that in the US, except for lower rates of cancer screening and influenza immunization in Switzerland, even though there is no systematic performance monitoring, nor mandatory annual report cards on quality of care in Switzerland. Our study was not designed to assess the reasons for unprovided recommended care, but hypotheses are the lack of a national campaign for cancer screening, the limited information in the media about health issues in Switzerland, compared to the US, and the lack of systematic performance monitoring with regular feedback (which might improve PCP performance22). An older Swiss study23 found similarly low rates of influenza immunization (41% if age <65 years with chronic illness and 51% if >65 years), suggesting a lower acceptance of influenza immunization24 than in the US. Another study using RAND’s QA Tools showed that quality of care in the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) was higher than that in the community.14 Much of the difference was attributable to VA scoring higher in conditions subject to VA performance monitoring. The high overall level of care we found may be related to universal coverage or to the specific setting. Indeed, quality of care might have been lower if we had included community-based PCP offices outside of university primary care settings, like in the US14 or UK25,26 studies.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to document the quality of a broad range of primary and secondary preventive care indicators in Continental Europe. In the UK, the systematic performance monitoring known as QOF3 was introduced in 2004. Current published data were limited to patients with cardiovascular diseases26 or diabetes,25 which may not be applicable to the general population. In over a million patients with diabetes followed in 147 clinics, Calvert et al.25 found higher rates of HbA1c testing (89.3% vs 71.9% in our study), annual eye examination (75.0% vs 55.8%) or screening for nephropathy (74.1% vs 65.1%), but a lower rate of cholesterol testing (89.7% vs 97.6%). Other quality indicators of the prevention and management of cardiovascular diseases in primary care have been developed across nine European countries,4 but no data using this new set of indicators have been published yet. For Switzerland, no study has been published on the overall quality of preventive care, but only on specific conditions.9–11

Men received more recommended care than women. The gender differences in quality of care are consistent with studies on hypertension,27 dyslipidemia,28 diabetes care29,30 or therapy introduced after cardiovascular events.31–33 More attention should be placed on preventive care for women in Switzerland.

Patients <65 years also received more recommended care than the elderly, although the 2.1% difference was borderline statistically significant and may not be clinically meaningful. The lower rate of recommended care among older adults might be related to the higher number of indicators for which older adults became eligible or to lower attention to preventive care. Our findings of lower preventive care in the elderly are similar to those of a previous US study,2 but need to be confirmed by further research.

The higher level of quality of care for CVRFs compared to preventive care might be explained by the ease of ordering laboratory tests or prescribing new medications compared to counseling on lifestyle modifications or cancer screening. Counseling might also have been subject to more underreport than laboratory tests in medical charts.

Our study has several limitations. Our data were only abstracted from medical charts with potential underreporting. A previous study compared process-based quality scores using standardized patients, clinical vignettes and abstraction of medical charts, and found that measurement of quality of care using abstraction of medical charts was about 5% lower than using clinical vignettes and 10% lower than using standardized patients.34 As influenza immunization can be done directly by nurses in Switzerland, we validated the influenza immunization indicators with an external administrative register at one site (Lausanne) and found that 8% of patients had actually been immunized, although this information was not reported in the medical chart, a similar rate as in the previous report described above.34 Another limitation was that some indicators had a lower inter-rater reliability (see Methods). Sensitivity analyses excluding these indicators yielded a higher aggregate score for chronic care of CVRFs (93% vs 83%), which might be explained by the lower rates of provided care for these indicators with a lower kappa statistic. A third limitation was that our data were only abstracted in university primary care settings, where almost all patients received their care from residents. Aggregate scores were similar for patients followed by residents and university attendings, but the proportion of patients followed by university attendings (10%) was small for such comparisons. A previous study found a higher adherence to diabetes care guidelines by internal medicine residents compared to faculty members,35 whereas another found similar rates of performance for preventive care between residents and attendings.36 One study among Swiss community-based PCPs found similar results for diabetes care11 (as measured by face-to-face interviews of PCPs) compared to our study. However, we did not find studies directly comparing performance between community-based PCPs and university-based residents. Therefore, our data may not be generalizable to community-based PCPs. Additionally, our study included slightly fewer women in university primary care settings than the natural gender ratio of the Swiss general population (44.4% vs 50.8% of women, respectively), which might be related to the fact that many healthy Swiss women are followed only by gynecologists.

In summary, using indicators from RAND’s QA Tools, adults in university primary care settings received 69% of recommended preventive care and 83% of chronic care for CVRFs in Switzerland, a country without systematic performance monitoring but universal insurance coverage. Women and the elderly had lower receipt of recommended preventive care services, and cancer screening rates were low. Our findings suggest that, like in the US, there still is substantial room for improvement in preventive care delivered to Swiss adults, in particular for cancer screening and influenza immunization. Our study may allow better targeting of future quality initiatives in specific areas and strengthening the case for broader performance review of quality of care across Continental Europe.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

PDF 308 kb

Acknowledgements

Research funding for the collection and analysis of these data was provided by an investigator-initiated unrestricted grant from Pfizer (Switzerland), but had no role in the study design, the choice of statistical analyses, or the preparation of the manuscript. Tinh-Hai Collet’s work was partially supported by a grant from the Swiss Heart Foundation. An oral presentation of preliminary results was given at the 32nd SGIM Annual Meeting, May 2009, Miami, FL, under the title “The quality of preventive care delivered to adults in European university primary care settings.”

Potential Conflicts of Interest An investigator-initiated grant from Pfizer (Switzerland) was provided only for data collection and analysis, but had no role in the study design, the choice of statistical analyses, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Tinh-Hai Collet and Sophie Salamin contributed equally to the article.

References

- 1.McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2635–45. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa022615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asch SM, Kerr EA, Keesey J, et al. Who is at greatest risk for receiving poor-quality health care? N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1147–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa044464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roland M. Linking physicians' pay to the quality of care–a major experiment in the United kingdom. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1448–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr041294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell SM, Ludt S, Lieshout J, et al. Quality indicators for the prevention and management of cardiovascular disease in primary care in nine European countries. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2008;15:509–15. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e328302f44d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolf-Maier K, Cooper RS, Kramer H, et al. Hypertension treatment and control in five European countries, Canada, and the United States. Hypertension. 2004;43:10–7. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000103630.72812.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang YR, Alexander GC, Stafford RS. Outpatient hypertension treatment, treatment intensification, and control in Western Europe and the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:141–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.2.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eliasson B, Cederholm J, Nilsson P, Gudbjornsdottir S. The gap between guidelines and reality: Type 2 diabetes in a National Diabetes Register 1996–2003. Diabet Med. 2005;22:1420–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gorter K, Bruggen R, Stolk R, Zuithoff P, Verhoeven R, Rutten G. Overall quality of diabetes care in a defined geographic region: different sides of the same story. Br J Gen Pract. 2008;58:339–45. doi: 10.3399/bjgp08X280209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodondi N, Cornuz J, Marques-Vidal P, et al. Aspirin use for the primary prevention of coronary heart disease: a population-based study in Switzerland. Prev Med. 2008;46:137–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muntwyler J, Noseda G, Darioli R, Gruner C, Gutzwiller F, Follath F. National survey on prescription of cardiovascular drugs among outpatients with coronary artery disease in Switzerland. Swiss Med Wkly. 2003;133:88–92. doi: 10.4414/smw.2003.10119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bovier PA, Sebo P, Abetel G, George F, Stalder H. Adherence to recommended standards of diabetes care by Swiss primary care physicians. Swiss Med Wkly. 2007;137:173–81. doi: 10.4414/smw.2007.11592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.HEDIS 2007 State of Health Care Quality. 2007. (Accessed 1st December 2010, at http://www.ncqa.org/Portals/0/Publications/Resource%20Library/SOHC/SOHC_07.pdf.)

- 13.Kerr EA, Smith DM, Hogan MM, et al. Building a better quality measure: are some patients with 'poor quality' actually getting good care? Med Care. 2003;41:1173–82. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000088453.57269.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Asch SM, McGlynn EA, Hogan MM, et al. Comparison of quality of care for patients in the Veterans Health Administration and patients in a national sample. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:938–45. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-12-200412210-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGlynn EA, Kerr EA, Asch SM. New approach to assessing clinical quality of care for women: the QA Tool system. Womens Health Issues. 1999;9:184–92. doi: 10.1016/S1049-3867(99)00009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brook RH, editor. The RAND/UCLA appropriateness method. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodondi N, Peng T, Karter AJ, et al. Therapy modifications in response to poorly controlled hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:475–84. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-7-200604040-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kerr EA, Gerzoff RB, Krein SL, et al. Diabetes care quality in the Veterans Affairs Health Care System and commercial managed care: the TRIAD study. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:272–81. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-4-200408170-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sim J, Wright CC. The kappa statistic in reliability studies: use, interpretation, and sample size requirements. Phys Ther. 2005;85:257–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reeves D, Campbell SM, Adams J, Shekelle PG, Kontopantelis E, Roland MO. Combining multiple indicators of clinical quality: an evaluation of different analytic approaches. Med Care. 2007;45:489–96. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31803bb479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kerr EA, Fleming B. Making performance indicators work: experiences of US Veterans Health Administration. BMJ. 2007;335:971–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39358.498889.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bovier PA, Chamot E, Bouvier Gallacchi M, Loutan L. Importance of patients' perceptions and general practitioners' recommendations in understanding missed opportunities for immunisations in Swiss adults. Vaccine. 2001;19:4760–7. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(01)00223-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blank PR, Schwenkglenks M, Szucs TD. Vaccination coverage rates in eleven European countries during two consecutive influenza seasons. J Infect. 2009;58:446–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Calvert M, Shankar A, McManus RJ, Lester H, Freemantle N. Effect of the quality and outcomes framework on diabetes care in the United Kingdom: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2009;338:b1870. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campbell SM, Reeves D, Kontopantelis E, Sibbald B, Roland M. Effects of pay for performance on the quality of primary care in England. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:368–78. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0807651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keyhani S, Scobie JV, Hebert PL, McLaughlin MA. Gender disparities in blood pressure control and cardiovascular care in a national sample of ambulatory care visits. Hypertension. 2008;51:1149–55. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.107342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hahn KA, Strickland PA, Hamilton JL, Scott JG, Nazareth TA, Crabtree BF. Hyperlipidemia guideline adherence and association with patient gender. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2006;15:1009–13. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wexler DJ, Grant RW, Meigs JB, Nathan DM, Cagliero E. Sex disparities in treatment of cardiac risk factors in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diab Care. 2005;28:514–20. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.3.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferrara A, Mangione CM, Kim C, et al. Sex disparities in control and treatment of modifiable cardiovascular disease risk factors among patients with diabetes: Translating Research Into Action for Diabetes (TRIAD) Study. Diab Care. 2008;31:69–74. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Opotowsky AR, McWilliams JM, Cannon CP. Gender differences in aspirin use among adults with coronary heart disease in the United States. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:55–61. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0116-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cecco R, Patel U, Upshur RE. Is there a clinically significant gender bias in post-myocardial infarction pharmacological management in the older (>60) population of a primary care practice? BMC Fam Pract. 2002;3:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-3-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holroyd-Leduc JM, Kapral MK, Austin PC, Tu JV. Sex differences and similarities in the management and outcome of stroke patients. Stroke. 2000;31:1833–7. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.8.1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peabody JW, Luck J, Glassman P, Dresselhaus TR, Lee M. Comparison of vignettes, standardized patients, and chart abstraction: a prospective validation study of 3 methods for measuring quality. JAMA. 2000;283:1715–22. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.13.1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suwattee P, Lynch JC, Pendergrass ML. Quality of care for diabetic patients in a large urban public hospital. Diab Care. 2003;26:563–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.3.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dresselhaus TR, Peabody JW, Luck J, Bertenthal D. An evaluation of vignettes for predicting variation in the quality of preventive care. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:1013–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-004-0003-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–72. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.American Diabetes Association Standards of medical care in diabetes-2010. Diab Care. 2010;33(Suppl 1):S11–61. doi: 10.2337/dc10-S011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

PDF 308 kb