ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Professional interpreter use improves the quality of care for patients with limited English proficiency (LEP), but little is known about interpreter use in the hospital.

OBJECTIVE

Evaluate interpreter use for clinical encounters in the hospital.

DESIGN

Cross-sectional.

PARTICIPANTS

Hospitalized Spanish and Chinese-speaking LEP patients.

MAIN MEASURES

Patient reported use of interpreters during hospitalization.

KEY RESULTS

Among 234 patients, 57% reported that any kind of interpreter was present with the physician at admission, 60% with physicians during hospitalization, and 37% with nurses since admission. The use of professional interpreters with physicians was infrequent overall (17% at admission and 14% since admission), but even less common for encounters with nurses (4%, p < 0.0001). Use of a family member, friend or other patient as interpreter was more common with physicians (28% at admission, 23% since admission) than with nurses (18%, p = 0.008). Few patients reported that physicians spoke their language well (19% at admission, 12% since admission) and even fewer reported that nurses spoke their language well (6%, p = 0.0001). Patients were more likely to report that they either “got by” without an interpreter or were barely spoken to at all with nurses (38%) than with physicians at admission (14%) or since admission (15%, p < 0.0001).

CONCLUSIONS

Interpreter use varied by type of clinical contact, but was overall more common with physicians than with nurses. Professional interpreters were rarely used. With physicians, use of ad hoc interpreters such as family or friends was most common; with nurses, patients often reported, “getting by” without an interpreter or barely speaking at all.

KEY WORDS: language proficiency, interpreter use, non-English-speaking patients

INTRODUCTION

The use of professional interpreters improves the quality of care for patients with limited English proficiency (LEP), resulting in increased patient satisfaction, reduced disparities, and improved clinical outcomes.1–3 Title VI of the Civil Rights Act mandated access to language services for all health care organizations receiving federal funds, and at least 43 states have enacted one or more laws addressing language access in healthcare settings.4,5 In addition, hospital guidelines, including the Joint Commission standards, recommend the routine use of professional interpreters.6,7

Yet professional interpreters are often not used for patients with LEP.8,9 Resident physicians report relying frequently on ad hoc interpretation by family members, friends or clinical staff, or using their own limited second language skills.10–12 These studies suggest both inadequate access to appropriate language services and widespread underuse of professional interpreters, but do not illustrate how patterns of interpreter use may vary for different types of interactions in the hospital.13 Few studies have examined interpreter use with nurses, and interpreter use is rarely assessed from the patient’s perspective. Understanding patterns of interpreter use is critical to the design and implementation of effective interventions to improve the quality of care for patients facing language barriers in the hospital. We therefore conducted this study to examine interpreter use for clinical encounters with physicians and nurses among hospitalized Spanish- and Chinese-speaking patients with LEP.

METHODS

Design and Setting

Hospitalized Spanish- and Chinese-speaking patients with LEP were recruited as part of a larger study on hospital and discharge communication. The larger study followed patients after their hospitalizations, and included comparison data on English-speakers. The current cross-sectional analysis includes baseline data on patients with LEP only.

Patients were enrolled from the general medical and surgical wards at two urban hospitals in the San Francisco Bay Area— one public and one academic medical center. Both sites serve a diverse patient population: approximately 33% of patients at the public hospital and 18% of patients at the academic medical center speak limited English. The public hospital employees 20 staff interpreters who work in a broad range of languages, the most frequent of which is Spanish. The academic medical center employs 19 staff interpreters who work in three main languages (Chinese, Spanish, Russian). At both medical centers, staff interpreters serve extensive outpatient primary care and specialty clinics, busy emergency departments, and the inpatient hospital. Both sites are teaching hospitals and resident physicians with faculty supervision see the majority of admissions initially. The public hospital is a level II Trauma Center and has 236 inpatient beds. The academic medical center houses a children’s hospital and has 600 inpatient beds.

Initial recruitment of Spanish-speaking patients took place at the public hospital during two six-month periods between 2005 and 2007. In order to increase the diversity of our sample, in 2007–2008 we recruited Chinese-speaking (both Mandarin and Cantonese) patients at both the public hospital and the academic medical center, which has a larger Chinese population.

At both sites, Chinese- and Spanish-speaking in-person professional interpreters were available weekdays from 8 AM–5 PM throughout the recruitment period. Both hospitals also had between one and three speaker or dual-handset phones available on each medical and surgical ward. These telephones could be used to access professional interpreters 24-hours-per day, 7 days per week. In addition, the public hospital employed two nurses with the dual role of working as Spanish interpreters when they were on the medical–surgical floor.

Participant Eligibility and Recruitment

Participant eligibility criteria for the larger study on hospital and discharge communication included 1) admission to the general medical or surgical ward; 2) ≥ 18 years old; 3) Chinese-, Spanish- or English-speaking; and 4) able to pass a brief cognitive screening test, to ensure that the participant was cognitively intact in order to complete the interview14. Recruitment was conducted by bilingual research assistants who visited the hospital wards three times per week. After reviewing chart documentation of the patient’s primary language and checking with the charge or floor nurse for permission to enter the patient’s room, the research assistant approached all available Spanish- and Chinese-speaking patients for potential participation. English-speaking patients were also recruited over the same time period for the larger study, but only patients with LEP were included in this analysis. The informed consent process and baseline interview were conducted in the patient’s preferred language during his or her hospitalization, on average 3 (± 3) days after admission. Participants received $15 after the baseline interview in appreciation of their time and effort. The institutional review boards at each hospital approved all study procedures.

Measures

English proficiency was determined by asking patients how well they spoke English (‘not at all,’ ‘not well,’ ‘well’ or ‘very well’) and in what language they preferred to receive their medical care. Based on previous work15, patients who reported speaking English ‘not at all’ or ‘not well,’ and patients who reported speaking English ‘well’ but preferring to receive medical care in another language were designated as limited English proficient.

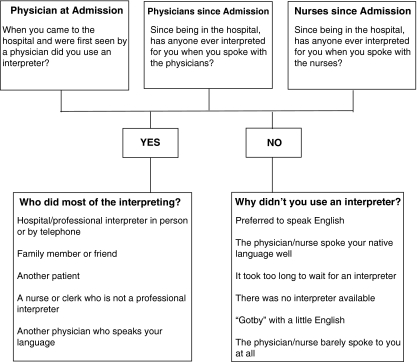

Patients were asked about their use of interpreters for three types of clinical encounters: with the physician at admission, with physicians since admission, and with nurses since admission. For each encounter, patients were reminded that an interpreter could be a family member or friend, a hospital staff member, or a professional provided by the hospital specifically to interpret. If the patient reported that any type of interpreter was present, they were prompted to indicate who did most of the interpreting for that type of clinical encounter. If the patient reported that an interpreter was not present, they were asked why they didn’t use an interpreter (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Questions and response options regarding use of interpreters for three types of clinical encounters.

In addition, patients were asked about their preferences for interpreter use with physicians (“In general, do you prefer to have someone interpret for you when you speak with a physician?”) and with nurses (“In general, do you prefer to have someone interpret for you when you speak with a nurse?”), as well as their overall access to interpreters in the hospital (“Since being in the hospital, has anybody ever asked you if you wanted or needed an interpreter?”).

Age and sex were determined by questionnaire. Education was measured by asking participants “What is the highest grade or year of school you have completed?” Co-morbidity score was measured using an adaptation of the validated Self-Administered Co-morbidity Questionnaire16, which was designed for use in clinical and health services survey research, using a count of co-morbidities with a potential range of 0-15. The hospital service (Medicine or Surgery) caring for each patient was determined from the medical record.

Data Analysis

Our goal was to examine patterns of interpreter use for the three different types of clinical encounters (with the physician at admission, with physicians since admission, and with nurses since admission). In bivariate analysis, we compared presence of an interpreter for each encounter type by patient characteristics using Pearson chi-square tests. We then compared type of interpreter present and reasons why an interpreter was not present by clinical encounter type using Rao-Scott chi-square tests to adjust for patient clusters given that patients were asked the same questions three times about three different encounter types. Finally, we used logistic regression to explore predictors of interpreter use for the three encounter types, adjusting for patient characteristics hypothesized a priori to be associated with interpreter use (age, sex, education, primary language, co-morbidity score and hospital service).

RESULTS

A total of 374 patients were recruited in the overall study between 2005 and 2008, with a collaboration rate of 71%. For this cross-sectional analysis, we included only Spanish- and Chinese-speaking patients with limited English proficiency (N = 234). Of the 234 participants, 54% were men, 22% had completed high school, and the mean age was 44 years (range 18 to 88). Participants were 85% Spanish-speaking and 15% Cantonese- or Mandarin-speaking. The mean number of co-morbidities was 1.9 (s.d. 1.7; range 0 to 8). Overall, 39% of participants were hospitalized on a medical service and 61% were hospitalized on a surgical service. Most (78%) reported that they were first seen by a physician in the Emergency Department.

The vast majority (93%) of participants reported a general preference for interpreters when speaking with physicians; most (73%) also preferred interpreters when speaking with nurses. However, only 43% of all participants reported that they had been asked if they wanted or needed an interpreter since admission. Overall, 130 (57%) of participants reported that any type of interpreter was present with the physician at admission, 137 (60%) reported that any type of interpreter was ever used with physicians since admission, and 85 (37%) reported that any type of interpreter was ever used with nurses since admission.

Table 1 shows whether an interpreter was present for each of the three clinical encounter types, by patient characteristics. With both physicians and nurses, interpreter use was more common in encounters with older patients and with Chinese-speaking patients. Interpreter use was also somewhat more common with patients with more co-morbidity. During hospitalization, use of interpreters with nurses was more common for communication with less educated patients, and with both physicians and nurses interpreter use was more common for patients on a Medical service.

Table 1.

Presence of Interpreters at Three Types of Clinical Encounters by Patient Characteristics (N = 234), at Two Hospitals in the San Francisco Bay Area, 2005–2008

| N | Interpreter present with physician at admission N (%) | P value | Interpreter present with physicians since admission N (%) | P value | Interpreter present with nurses since admission N (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.0001 | 0.03 | 0.003 | ||||

| 18-24 | 28 | 11 (39) | 16 (57) | 8 (29) | |||

| 25-49 | 128 | 61 (48) | 68 (54) | 37 (29) | |||

| 50-64 | 46 | 33 (77) | 27 (66) | 21 (49) | |||

| ≥ 65 | 32 | 25 (78) | 26 (81) | 19 (59) | |||

| Sex | 0.28 | 0.95 | 1.0 | ||||

| Men | 126 | 66 (53) | 74 (60) | 46 (37) | |||

| Women | 108 | 64 (60) | 63 (61) | 39 (37) | |||

| Education | 0.58 | 0.19 | 0.03 | ||||

| Less than High School graduate | 183 | 104 (57) | 112 (63) | 73 (40) | |||

| High School graduate or more | 51 | 26 (53) | 25 (52) | 12 (24) | |||

| Primary language | 0.002 | 0.03 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Cantonese/Mandarin | 35 | 25 (78) | 22 (69) | ||||

| Spanish | 199 | 112 (57) | 63 (32) | ||||

| Co-morbidity Score | 0.04 | 0.17 | 0.02 | ||||

| 0 | 56 | 24 (43) | 28 (51) | 13 (23) | |||

| 1 | 62 | 33 (53) | 40 (66) | 26 (41) | |||

| 2 | 38 | 23 (61) | 20 (53) | 11 (29) | |||

| 3 or more | 74 | 50 (68) | 49 (67) | 35 (47) | |||

| 104 (53) | |||||||

| Hospital Service | 0.95 | 0.004 | 0.0002 | ||||

| Medical | 90 | 50 (57) | 63 (72) | 46 (52) | |||

| Surgical/Gyn | 142 | 79 (56) | 73 (53) | 39 (28) |

Patterns of interpreter use for each clinical encounter type are shown in Table 2. The use of hospital interpreters was uncommon overall (17% with physician at admission, 14% with physicians since admission), but particularly infrequent for encounters with nurses (4%; p < 0.0001). Use of a family member, friend or other patient as interpreter was more common with physicians (28% at admission, 23% since admission) than with nurses (18%; p = 0.008). Use of a nurse, clerk or another physician as interpreter was more common with physicians since admission (23%) as compared to with physicians at admission (12%) or with nurses (14%; p = 0.0004). Few patients reported that they did not use an interpreter because physicians spoke their language well (19% at admission, 12% since admission) and even fewer reported non-use because nurses spoke their language well (6%; p = 0.0001). Patients were more likely to report that they either “got by” with a little English or were barely spoken to at all with nurses (38%) than with physicians at admission (14%) or since admission (15%; p < 0.0001).

Table 2.

Patterns of Interpreter use for Three Types of Clinical Encounters Among Patients (N = 234) at Two Hospitals in the San Francisco Bay Area, 2005-2008

| With physician at admission N (%) | With physicians since admission N (%) | With nurses since admission N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interpreter present | 130 (57) | 137 (60) | 85 (37) |

| Hospital interpreter | 37 (17) | 30 (14) | 10 (4) |

| Family member, friend or other patient | 63 (28) | 50 (23) | 42 (18) |

| Nurse, clerk or physician | 26 (12) | 52 (23) | 31 (14) |

| Interpreter not present | 100 (43) | 90 (40) | 146 (63) |

| Preferred to speak English | 10 (4) | 13 (6) | 20 (9) |

| Physician or nurse spoke your native language well | 42 (19) | 26 (12) | 14 (6) |

| Too long to wait or none available | 15 (7) | 17 (8) | 26 (11) |

| “Got by” or the physician/nurse barely spoke to you at all | 31 (14) | 34 (15) | 86 (38) |

We present multivariate results in Table 3. Older age was associated with higher odds of interpreter use with the physician at admission (OR 1.4, 95% CI 1.1-1.8; p = 0.001), but this association did not achieve significance for other encounter types. Patient primary language was not associated with interpreter use with physicians, but Chinese-speaking patients had higher odds than Spanish-speakers of interpreter use with nurses (OR 3.3, 95% CI 1.2-9.3; p = 0.02). Compared to a surgical service, hospitalization on a medical service was associated with higher odds of interpreter use for encounters with both physicians (OR 2.1, 95% CI 1.1-3.9; p = 0.02) and nurses (OR 2.6, 95% CI 1.4-4.8; p = 0.003) since admission, but not with physicians at admission.

Table 3.

Predictors of Interpreter use for Three Types of Clinical Encounters* Among Patients (N = 234) at Two Hospitals in The San Francisco Bay Area, 2005-2008

| With physician at admission | With physicians since admission | With nurses since admission | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MV Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P value | MV Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P value | MV Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age (per 10-year increase) | 1.4 (1.1-1.8) | 0.001 | 1.2 (0.9-1.4) | 0.14 | 1.2 (1.0-1.5) | 0.10 |

| Sex | 0.61 | 0.87 | 0.90 | |||

| Men | 0.9 (0.5-1.5) | 1.0 (0.5-1.7) | 1.0 (0.5-1.8) | |||

| Women | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Education | 1.0 | .30 | 0.05 | |||

| Less than High School graduate | 1.0 (0.5-2.0) | 1.4 (0.7-2.8) | 2.2 (1.0-4.9) | |||

| High School graduate or more | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Primary language | 0.44 | 0.30 | 0.02 | |||

| Cantonese/Mandarin | 1.5 (0.5-4.6) | 1.8 (0.6-5.1) | 3.3 (1.2-9.3) | |||

| Spanish | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Medical co-morbidity score (per 1-pt increase) | 1.0 (0.9-1.3) | 0.64 | 0.9 (0.8-1.1) | 0.51 | 0.9 (0.8-1.1) | 0.41 |

| Hospital Service | 0.25 | 0.02 | 0.003 | |||

| Medicine | 0.7 (0.4-1.3) | 2.1 (1.1-3.9) | 2.6 (1.4-4.8) | |||

| Surgical | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

*All odds ratios for a model adjusted for age, sex, education, primary language, medical co-morbidity score and hospital service

DISCUSSION

We report here on a unique study of patterns of interpreter use in the hospital from the patient perspective. Among hospitalized Spanish- and Chinese-speaking patients with LEP at two clinical sites, we found that interpreter use varied for clinical contacts with physicians or nurses, but was low overall. Hospital or professional interpreters were infrequently used for any type of contact, yet few patients reported that physicians or nurses spoke their native language well. With physicians, use of family, friends or staff as ad hoc interpreters was most common; in contrast, with nurses, patients often reported “getting by” without an interpreter or barely speaking at all. The low rates of reported professional interpreter use during three categories of interactions with both physicians and nurses raise concerns about quality of care for hospitalized patients with LEP.

Our findings of low rates of professional interpreter use overall mirror the results of studies conducted in the emergency department8 and outpatient settings.17 In exploring patient characteristics associated with patterns of interpreter use, we found that patients hospitalized on a medical service reported higher rates of interpreter use for encounters with physicians and nurses than patients hospitalization on a surgical service. This result suggests that different specialties may have very different patterns of communication with hospitalized patients. Further research is needed to examine this hypothesis and its implications in broader populations and settings.

The particularly low rate of interpreter use we observed in encounters with nurses is striking and has not been previously described. While interactions with nurses may be shorter and more routine than interactions with physicians, they frequently involve critical communication such as assessing a patient’s pain level or checking for medication allergies. “Getting by” without language assistance for these encounters may negatively impact the care of patients with LEP, and could have significant clinical consequences.18,19 Interestingly, patient preference for interpreter use, while slightly lower for interactions with nurses than for interactions with doctors, was high overall. Failure to use any type of interpreter for nursing encounters thus seems unlikely to represent a patient-centered decision.

Several possible explanations exist for our findings of infrequent interpreter use among nurses. It is possible that nurses are “getting by” without interpreters because they view communication as a less critical part of many of their routine interactions with patients. For example, when giving a medication or changing a patient’s dressing, a nurse may not think an interpreter is necessary. However, our finding that only 37% of patients reported ever using an interpreter when speaking with a nurse suggests that language service use is uncommon for more complex as well routine nursing interactions. It is also possible that nurses do not receive adequate training regarding how to access interpreter services, or that patients do not realize that they are entitled to an interpreter when talking with nurses. Finally, it is likely that current models of interpreter delivery present a greater challenge for nurses than for physicians. While physicians have more flexibility in their days and can schedule an in-person professional interpreter in advance, or return to see a patient at a later time when an interpreter is available, nurses are constantly moving from one task to the next and can seldom delay patient care activities to wait for language assistance.

Several recommendations stem from these findings. First, innovations are needed to improve access to professional interpreters for hospitalized patients with LEP. The acute hospital setting presents a particularly difficult access challenge due to the 24-hour nature of care, time pressures, and the brevity of many interactions. Attention should be paid to the types of hospital interactions for which remote modalities of professional interpretation—such as telephonic and video-conferencing interpretation—are adequate, and those for which an in-person professional interpreter is required. When studied at a different public hospital, video medical interpretation (VMI)—with interpreters housed at a central call center—has been shown to decrease costs per interpreted encounter and increase the volume of interpretation provided per month.20 While VMI exists in other locations at both the medical centers in our study, it has not yet been successfully integrated into an adult inpatient setting at any hospital. Further implementation of VMI and telephonic interpretation with easy access at the bedside may increase utilization by both nurses and physicians in the busy inpatient setting. Second, hospitals can assist with the appropriate allocation of available resources by setting and enforcing standards for appropriate interpreter use, as well as improving systems to identify and flag patients who speak limited English (much the way hospitals identify patients who are a fall risk). Third, patients should also be better educated about their right to a professional interpreter, as sometimes it may be only the patient who realizes that an interpreter is necessary.13 Lastly, more research is needed to better define the impact of interpreter use on errors and costs. We postulate that failure to communicate adequately with patients with LEP may contribute to medical errors during hospitalization21, as well as higher rates of re-hospitalization compared with English-speaking patients.22 While cost is clearly a barrier to achieving adequate interpreter access4, such costs may be offset by avoiding significant errors and unnecessary re-hospitalizations.

Several limitations must be considered in the interpretation of our study. First, this was a study at two sites; our findings may not generalize to other hospitals or settings. However, both sites in this study serve large numbers of patients with LEP and are located in a diverse area of the US. It is likely that patients’ experiences may be worse in settings with less linguistic diversity or resources allocated to interpreter services. Second, available patient populations and our recruitment methods resulted in all Spanish-speaking patients being enrolled at the public hospital and the majority of Chinese-speaking patients being enrolled at the academic medical center. We were therefore unable to examine or adjust for site differences, and it is possible that differences in interpreter use by language reflect unmeasured differences between the two sites. In fact, we enrolled more surgical than medical patients, possibly reflecting the fact that the public hospital site serves a relatively young population hospitalized for acute illness or trauma. Additionally, we included only Spanish- and Chinese-speaking patients (the two most common non-English languages spoken at these hospitals and in the US), and our sample was not evenly balanced between the two. It is possible that the experiences of patients who speak other, less common languages may be quite different, but seems unlikely to be better than reported here. Third, we captured data on general interaction types for both medical and surgical patients, and do not have information on the clinical content or frequency of these encounters. Specific communication needs on medical and surgical services may be quite different, and could not be examined as part of this study. And finally, interpreter use was based on patient self-report, and not directly observed, nor were interpreter records reviewed or physicians and nurses surveyed.

Overall, our findings suggest that interpreter use for hospitalized patients with LEP is inadequate. Interventions are needed to improve the interpreter use for the frequent and often brief interactions between hospitalized patients with LEP and their clinicians. Increasing access to professional interpreters, prioritizing encounter types for which interpreters should be used, educating physicians, nurses and patients about language services, and changing organizational and professional norms around communication with hospitalized patients may significantly improve the quality and safety of care provided to hospitalized patients with LEP.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grant no. 20061003 from The California Endowment and by grant no. P30-AG15272 of the Resource Centers for Minority Aging Research program funded by the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health. Dr. Schenker was supported by the General Internal Medicine Fellowship at UCSF, funded by the Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration (DHHS HRSA D55HP05165), and then by a Junior Faculty Career Development Award from the National Palliative Care Research Center. We thank Steven Gregorich for statistical advice, Gabriel Somma, Monica Lopez and Julissa Saavedra for data collection and management, and the staff and physicians at the Alameda County Medical Center for their participation.

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

References

- 1.Baker DW, Hayes R, Fortier JP. Interpreter use and satisfaction with interpersonal aspects of care for Spanish-speaking patients. Med Care. 1998;36:1461–1470. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199810000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacobs EA, Lauderdale DS, Meltzer D, Shorey JM, Levinson W, Thisted RA. Impact of interpreter services on delivery of health care to limited-English-proficient patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:468–474. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016007468.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karliner LS, Jacobs EA, Chen AH, Mutha S. Do professional interpreters improve clinical care for patients with limited English proficiency? A systematic review of the literature. Health Serv Res. 2007;42:727–754. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00629.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen A, Youdelman MK, Brooks J. The Legal Framework for Language Access in Healthcare Settings: Title VI and Beyond. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:362–367. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0366-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perkins J. Ensuring Linguistic Access in Health Care Settings: An Overview of Current Legal Rights and Responsibilities: Kaiser Commission of Medicaid and the Uninsured; 2003.

- 6.National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services in Health Care: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Minority Health; 2001.

- 7.Wilson-Stronks A, Galvez, E. Hospitals, Language and Culture: A Snapshot of the Nation. Exploring Cultural and Linguistic Services in the Nations Hospitals: A Report of Findings: The Joint Commission and The California Endowment; 2007.

- 8.Baker DW, Parker RM, Williams MV, Coates WC, Pitkin K. Use and effectiveness of interpreters in an emergency department. Jama. 1996;275:783–788. doi: 10.1001/jama.275.10.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flores G, Torres S, Holmes LJ, Salas-Lopez D, Youdelman MK, Tomany-Korman SC. Access to hospital interpreter services for limited English proficient patients in new jersey: a statewide evaluation. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2008;19:391–415. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee KC, Winickoff JP, Kim MK, et al. Resident physicians' use of professional and nonprofessional interpreters: a national survey. Jama. 2006;296:1050–1053. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.9.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diamond LC, Schenker Y, Curry L, Bradley EH, Fernandez A. Getting by: underuse of interpreters by resident physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:256–262. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0875-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burbano O'Leary SC, Federico S, Hampers LC. The truth about language barriers: one residency program's experience. Pediatrics. 2003;111:e569–e573. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.5.e569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schenker Y, Lo B, Ettinger KM, Fernandez A. Navigating language barriers under difficult circumstances. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-4-200808190-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brodaty H, Low LF, Gibson L, Burns K. What is the best dementia screening instrument for general practitioners to use? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:391–400. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000216181.20416.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karliner LS, Napoles-Springer AM, Schillinger D, Bibbins-Domingo K, Perez-Stable EJ. Identification of limited English proficient patients in clinical care. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1555–1560. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0693-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sangha O, Stucki G, Liang MH, Fossel AH, Katz JN. The Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire: a new method to assess comorbidity for clinical and health services research. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:156–163. doi: 10.1002/art.10993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuo DZ, O'Connor KG, Flores G, Minkovitz CS. Pediatricians' use of language services for families with limited English proficiency. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e920–e927. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen AL, Rivara F, Marcuse EK, McPhillips H, Davis R. Are language barriers associated with serious medical events in hospitalized pediatric patients? Pediatrics. 2005;116:575–579. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schyve P. Language differences as a barrier to quality and safety in health care: The joint commission perspective. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:360–361. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0365-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karliner LS, Mutha S. Achieving quality in health care through language access services: lessons from a California public hospital. Am J Med Qual 2010 Jan-Feb; 25:51–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Divi C, Koss RG, Schmaltz SP, Loeb JM. Language proficiency and adverse events in US hospitals: a pilot study. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:60–67. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzl069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karliner LS, Kim SE, Meltzer DO, Auerbach AD. Influence of language barriers on outcomes of hospital care for general medicine inpatients. J Hosp Med 2010 May-June; 5:276–82. [DOI] [PubMed]