Abstract

Palaeobiogeographic reconstructions are underpinned by phylogenies, divergence times and ancestral area reconstructions, which together yield ancestral area chronograms that provide a basis for proposing and testing hypotheses of dispersal and vicariance. Methods for area coding include multi-state coding with a single character, binary coding with multiple characters and string coding. Ancestral reconstruction methods are divided into parsimony versus Bayesian/likelihood approaches. We compared nine methods for reconstructing ancestral areas for placental mammals. Ambiguous reconstructions were a problem for all methods. Important differences resulted from coding areas based on the geographical ranges of extant species versus the geographical provenance of the oldest fossil for each lineage. Africa and South America were reconstructed as the ancestral areas for Afrotheria and Xenarthra, respectively. Most methods reconstructed Eurasia as the ancestral area for Boreoeutheria, Euarchontoglires and Laurasiatheria. The coincidence of molecular dates for the separation of Afrotheria and Xenarthra at approximately 100 Ma with the plate tectonic sundering of Africa and South America hints at the importance of vicariance in the early history of Placentalia. Dispersal has also been important including the origins of Madagascar's endemic mammal fauna. Further studies will benefit from increased taxon sampling and the application of new ancestral area reconstruction methods.

Keywords: ancestral areas, dispersal, historical biogeography, Mammalia, vicariance

1. Introduction

Class Mammalia is impressive for its taxonomic, ecological and morphological diversity [1]. A fundamental goal of mammalian palaeobiogeography is to reconstruct the underlying history of vicariant and dispersal events that have shaped this diversity. Here, we highlight the importance of phylogeny reconstruction, ancestral area reconstruction and molecular dating for producing ancestral area chronograms. We compare different approaches for reconstructing ancestral areas, and illustrate similarities and differences between these approaches using a dataset for placental mammals. We conclude with a review of selected topics in placental mammal palaeogeography that illustrates how phylogenies, ancestral area reconstructions, molecular dates and palaeographic histories have reshaped our views on mammalian historical biogeography. Finally, we identify important areas for future inquiry.

2. Phylogeny reconstruction

Phylogeny reconstruction begins with character data. Large molecular datasets have yielded robust phylogenies for many groups, thereby reducing the number of phylogenetic hypotheses that must be considered when formulating ancestral area chronograms. The inclusion of morphological data from fossils allows for taxonomically richer phylogenies, while also providing key data points that bear on the geographical provenance of a taxonomic group. In the words of Simpson [2], fossils ‘are the historical documents of animal distribution’. Fossils are also more difficult to place with confidence in a phylogenetic framework owing to missing (molecular) data, and the inability of current methods to separate homology and homoplasy with some morphological datasets [3,4].

Maximum parsimony (MP) and maximum likelihood (ML) yield a single best tree(s), whereas Bayesian methods yield a sampling of trees from posterior probability space. ML and Bayesian methods have the advantage of incorporating models of sequence evolution and yield trees with branch lengths. Some ancestral area reconstruction methods, such as those implemented in SIMMAP [5], can take advantage of trees with branch lengths, as well as multiple trees from posterior probability space.

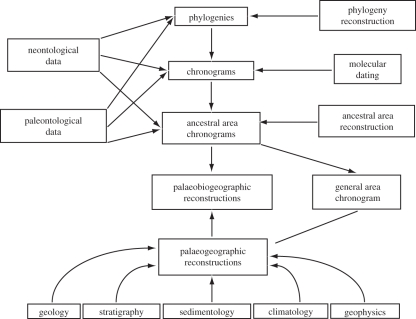

Phylogeny reconstruction is usually the first step in constructing an ancestral area chronogram, followed by the estimation of divergence times at each of the nodes. However, BEAST [6] allows for simultaneous estimation of branching relationships and divergence times. After reconstructing a phylogeny, molecular dating analyses and ancestral area reconstructions can be performed in parallel or in series, and then integrated to yield an ancestral area chronogram (figure 1).

Figure 1.

A flowchart of the approach used for incorporating different types of data, in conjunction with methods in phylogeny reconstruction, molecular dating and ancestral area reconstruction, for inferring ancestral area chronograms and palaeobiogeographic history.

3. Molecular dating analyses

Molecular clocks were introduced by Zuckerkandl & Pauling [7], but have fallen out of favour owing to the prevalence of lineage-specific rate variation. The emergence of relaxed molecular clock methods has promoted a resurgence of studies that have examined both interordinal and intraordinal divergence times in Mammalia [8–23]. Relaxed clock methods include penalized likelihood approaches [24,25], and Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo methods such as multidivtime [26], BEAST [6] and mcmctree [27]. It is useful to compare both the results of different programs and the results of the same program under different model and parameter settings [28–30].

An important difference between BEAST and multidivtime is that BEAST allows rates to vary randomly over lineages in a phylogeny, whereas multidivtime assumes autocorrelated rates. In simulation studies, BEAST performed poorly when rates were autocorrelated, whereas multidivtime performed poorly when there was uncorrelated rate variation [28]. Given these results, Battistuzzi et al. [28] recommended composite 95% credibility intervals.

Relaxed clock methods allow for multiple calibrations, including minimum and maximum constraints on individual nodes. Multidivtime only allows for ‘hard’ constraints, whereas BEAST and mcmctree provide other options including ‘soft’ constraints that permit specification of a given percentage (e.g. 95%) of the normal distribution between the minimum and maximum, with half of the remainder (e.g. 2.5%) allocated to each tail.

4. Ancestral area reconstruction

Methods for reconstructing historical biogeography include dispersalism, phylogenetic biogeography, panbiogeography, parsimony analysis of endemicity and cladistic biogeography [31]. Early reconstructions of mammalian historical biogeography were based on dispersalism and land bridges [2,32], and pre-date the general acceptance of plate tectonic theory. Subsequently, cladistic biogeography emphasized vicariance as the most important factor in diversification by discovering dichotomous area relationships (area cladograms) from taxon cladograms. In response to this paradigm, which paid little regard to dispersal and extinction, Ronquist [33] proposed dispersal–vicariance analysis (DIVA) for reconstructing patterns of historical biogeography [34]. DIVA infers ancestral areas by minimizing the number of dispersal and extinction events. Recent methods that build on Ronquist's work include Bayes-DIVA [35] and dispersal–extinction cladogenesis (DEC) [36,37].

A fundamental issue in ancestral area reconstruction is area coding. Areas are usually coded to include the entire geographical range of each species. Other options include coding the entire area of the monophyletic clade that is represented by the species, or the geographical area of the oldest fossil belonging to each lineage. An additional topic worthy of investigation is the problem of coding geographical areas for taxa from the geological past versus the present given that areas, as well as their boundaries and physical relationships to each other, can fluctuate over time. Parametric methods such as DEC, which allow for changing dispersal probabilities over time, provide a mechanism to accommodate the impact of continental fragmentation and suturing on historical biogeography.

Three general approaches are available for coding areas (box 1), whether for living species, fossils or larger monophyletic groups. The first method is single character, multi-state coding with non-overlapping character states. The second method is binary character coding with multiple characters, where each character represents the presence or absence of a taxon in a single area. In contrast to the first method, this approach allows ancestral nodes to encompass more than one area. Ancestral area reconstructions are simply the sum of the individual area reconstructions. A disadvantage of this approach is that ancestral areas may receive ‘no-state’ assignments, which imply empty ancestral areas. No-state assignments are an artefact of the character independence assumption [38]. Finally, string character coding [37] allows individual character states to include one or more geographical areas. Specifically, the geographical range of a species is coded as a string denoting its presence/absence in a set of individual areas. Ree & Smith's [37] string character coding is equivalent to Maddison & Maddison's [39] polymorphism coding.

Box 1. Methods for coding areas and analysing area-coded data matrices.

I. Area coding

1. single multi-state character coding. Individual character states are non-overlapping and correspond to a single area

disadvantages: ranges are limited to a single area (character state) unless they are coded as polymorphic

2. binary character coding with multiple characters. Each binary character corresponds to the presence/absence of a taxon in a single area

advantages: allows for the occupation of multiple areas

disadvantages: ancestral areas may receive no state assignments

3. string character coding (=polymorphism coding)

advantages: individual character states may include one or more areas

disadvantages: the number of character states becomes intractable when there are too many individual areas

II. Ancestral area reconstruction

1. monomorphic ancestral area reconstruction methods. These methods are used in conjunction with area data that have been coded as a single multi-state character

a. Fitch parsimony (e.g. MacClade)

b. stochastic mapping (e.g. SIMMAP)

advantages: stochastic mapping allows for branch lengths and multiple trees

disadvantages: methods in this category implicitly assume that different character states (areas) are homologous to each other, and attempt to find a single ancestral area (character state) at each node

2. polymorphic ancestral area reconstruction methods. These methods allow for ancestral areas that encompass more than one area, and employ either binary character data for multiple characters or string character data

a. Fitch parsimony (e.g. MacClade) with multiple, binary characters

b. stochastic mapping (e.g. SIMMAP) with multiple, binary characters

c. dispersal–vicariance (DIVA)

d. Bayes-DIVA

e. dispersal–extinction cladogenesis (DEC)

f. minimum area change (MAC) parsimony

advantages: all methods in this category allow for reconstructions that include multiple areas per node. Stochastic mapping and DEC incorporate branch lengths; stochastic mapping and Bayes-DIVA allow for multiple trees

disadvantages: methods that employ multiple binary characters can result in empty ancestral area reconstructions. Fitch parsimony, MAC parsimony and DIVA ignore branch length information. DIVA, Bayes-DIVA and DEC are biased towards ancestral reconstructions that include numerous individual areas

Ancestral reconstruction methods can be divided into parsimony versus Bayesian/likelihood approaches [40]. Only the latter takes advantage of branch lengths. Another useful distinction is between methods that reconstruct ancestral nodes as monomorphic character states versus those that allow for range expansion and contraction.

MP and ML methods employ discrete-state transition models, and reconstruct ancestral nodes as monomorphic. Monomorphic methods for character state reconstruction assume that different character states are homologous to each other, as is the case for characters that pass Patterson's [41] conjunction test, which states that two structures that are found in the same organism cannot be homologous. However, this test is nonsensical when applied to geographical areas because the presence of a species in one area does not rule out its presence in another area.

Other ancestral range reconstruction methods have the advantage of allowing for polymorphic ancestral states and thereby accommodating range expansion and contraction (box 1) [40]. Polymorphic reconstructions can be achieved using (i) monomorphic methods with multiple, binary characters, each of which codes for the presence/absence of a taxon in one area and (ii) polymorphic methods that allow ancestral nodes to include one or more areas.

Fitch parsimony and stochastic mapping can be used to reconstruct ancestral nodes for multiple binary characters, and then summed over all character reconstructions to obtain the complete set of areas for each ancestral node. One difficulty is ancestral nodes with no-state assignments. In these instances, multiple interpretations are possible, including vicariance of an ancestral area that was not included in the original analysis. If there is geological evidence for formerly contiguous areas, this information may be incorporated into ancillary characters to assist ancestral area reconstructions.

In contrast to methods that were co-opted from phylogenetics, DIVA [33] and DEC [36,37,42] were developed explicitly for historical biogeographic reconstruction. DIVA assigns no cost to widespread ancestral areas that are subdivided by vicariance, but assigns a cost to dispersal and local extinction events. DIVA ignores branch lengths. DEC uses a continuous time model for geographical range evolution, and employs string character coding to accommodate polymorphic areas. DEC permits range expansion through dispersal events and range contraction through local extinction events. DEC also allows areas of implausible distribution to be excluded, such as those that are geographically discontinuous [43]. DIVA and DEC are prone to reconstructing ancestral areas that include too many individual areas, especially towards the root of the tree. However, both programmes have options for limiting the number of ancestral areas.

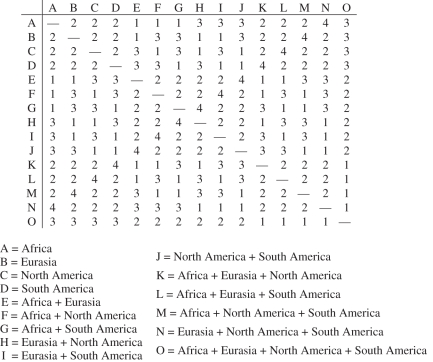

An additional approach that we introduce is minimum area change (MAC) parsimony, which uses polymorphic character coding [39] and Sankoff optimization, and can be implemented with Mesquite [44]. MAC parsimony requires a step matrix (figure 2). In contrast to DIVA, MAC parsimony assigns equal cost to all gains and losses of an area, whether through dispersal, local extinction or vicariance. An advantage of this approach is that it should be less prone than DIVA to reconstructing ancestral areas that are too broad relative to terminal taxa.

Figure 2.

Example of a step matrix for minimum area change (MAC) parsimony. MAC parsimony assigns equal cost to all gains and losses of an area. For example, a change in area from A (Africa) to G (Africa + South America) requires one step (gain South America), whereas a change from A to H (Eurasia + North America) requires three steps (Africa loss, Eurasia gain, North America gain). The step matrix is fully symmetrical.

Another recent approach that builds on earlier cladistic biogeography methods is phylogenetic analysis of comparing trees (PACT) [45–47]. Unlike earlier cladistic biogeography methods, PACT explicitly incorporates molecular dates into general area cladograms.

5. Ancestral area chronograms and palaeogeography

Ancestral area chronograms are similar to ancestral area cladograms, but additionally incorporate temporal information into their framework. Alternate approaches for reconstructing phylogeny, estimating divergence times and reconstructing ancestral areas may yield different ancestral area chronograms, each of which may be interpreted in the context of geology-based palaeogeographical hypotheses (figure 1). Ancestral area chronograms, in conjunction with geology-based palaeogeographical reconstructions, provide a framework for proposing, testing and refining palaeobiogeographic hypotheses. Ancestral area chronograms, when interpreted in the context of palaeogeographical hypothesis, yield insights into dispersal, vicariance and area extinctions, all of which are incorporated into palaeobiogeographic hypotheses (figure 1).

Ancestral area chronograms are taxon-specific, but ancestral area chronograms for multiple taxa that co-occur in the same region can yield general area chronograms. General area chronograms are similar to general area cladograms, but include temporal information that is absent from general area cladograms. The fundamental idea behind cladistic biogeography is that broad patterns, which are revealed through general area cladograms, demand comprehensive causal explanations. However, general area cladograms ignore temporal information and may result from pseudo-congruence when taxonomic groups with the same area relationships have different divergence times, and presumably different underlying causes [48]. Temporal information is critical for discriminating between groups that diversified during the same time period, and therefore may have experienced the same causal events, and groups that diversified during different time periods and require different causal explanations [48].

Just as there may be multiple ancestral area chronograms for a taxonomic group, there may also be multiple palaeogeographical hypotheses regarding the history of connections of formerly connected landmasses. For example, the ‘pan-Gondwanan’ and ‘Africa-first’ hypotheses represent alternate scenarios for the breakup of Gondwana [49]. Both hypotheses agree that the initial rift was between the African component of West Gondwana (Africa, South America) and the Indo-Madagascar component of East Gondwana, although connections between Africa and Indo-Madagascar were maintained via South America–Antarctica. Subsequent to this initial rift, the pan-Gondwanan hypothesis [50] postulates that three vicariant separations, South America from Africa, South America from Antarctica and Antarctica from Indo-Madagascar, all occurred during a narrow time window (100–90 Ma). The Africa-first hypothesis, in turn, suggests that Africa was the first Gondwanan continent to become completely separated from other Gondwanan landmasses when it separated from South America by approximately 100 Ma. Indo-Madagascar separated from Antarctica–Australia at approximately 130–110 Ma, but maintained subaerial connections with Antarctica via the Kerguelen Plateau, and possibly the Gunnerus Ridge to the west, well into the Late Cretaceous (approx. 80 Ma). The final separation was between the Antarctica Peninsula and the tip of South America in the Eocene.

Krause et al. [49] compared Cretaceous vertebrate faunas from different Gondwanan landmasses, and concluded that palaeontological data are most compatible with a modified version of the Africa-first hypothesis. Krause et al.'s [49] work also illustrates how biogeographic hypotheses based on fossils can be compared with geology-based palaeogeographical hypotheses in an arena that allows for reciprocal illumination. Thus, ancestral and general area chronograms provide a framework for evaluating competing geology-based palaeogeographical reconstructions just as geology-based palaeogeographical reconstructions provide a framework for evaluating alternate ancestral area chronograms (figure 1). Krause et al. [49] noted that there is no a priori reason to assume that geological data trump palaeontological data, or vice versa, insofar as each type of data can be used to reveal large-scale biogeographic patterns.

6. Placental phylogeny and a comparison of different ancestral area reconstruction methods

Most placental orders have first fossil occurrences and probable origins in Laurasia, but there are also orders with Gondwanan origins based on first fossil occurrences in South America (Xenarthra) or Africa (most afrotherian orders). Traditional morphological phylogenies [51,52] have suggested close relationships between Laurasian and Gondwanan orders, e.g. Edentata (Xenarthra (Gondwanan) + Pholidota (Laurasian)). By contrast, molecular phylogenies have recovered three superordinal groups, Afrotheria, Laurasiatheria and Euarchontoglires [3,53–63], that were not recovered on morphological trees. These three groups, plus Xenarthra, comprise the four major clades of placental mammals. There is also robust molecular support for Boreoeutheria (Euarchontoglires + Laurasiatheria) [60–62,64]. This overhaul of placental phylogeny, in conjunction with the results of molecular dating analyses, laid the foundation for new biogeographic hypotheses. We discuss these in §7, after first comparing the results of different ancestral area reconstruction methods in the remainder of this section.

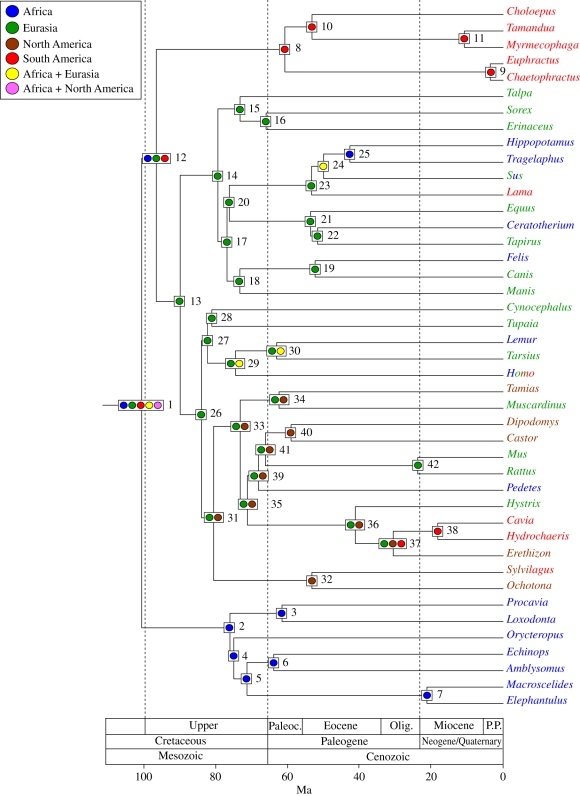

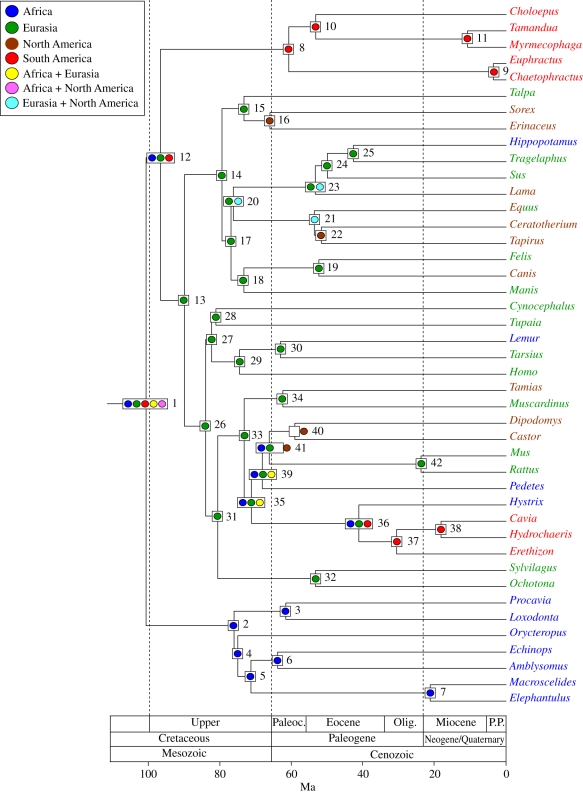

Ancestral area chronograms were reconstructed for 43 fully terrestrial placental taxa from Springer et al. [3]. Chiropterans and fully aquatic forms were excluded because of their different modes of dispersal (i.e. flight, swimming), and also because most fully aquatic taxa inhabit areas (i.e. oceans) that are not contained in the four-area scheme used in our analyses (see below). Ancestral area chronograms were reconstructed using a ML phylogram obtained with RAxML [65], molecular divergence dates estimated with BEAST [6] and ancestral areas reconstructed with a variety of methods.

Four areas (Africa, Eurasia, North America and South America) were recognized, and two methods were used to code areas for terminal taxa. First, areas were coded based on the geographical ranges of extant species. Second, areas were coded based on the geographical provenance of the oldest fossil for each lineage. The step matrix that was used in MAC parsimony analysis is shown in figure 2. Given that the number of character states that are chosen for geographical range subdivision is arbitrary, it may be instructive to compare the results of analyses with coarser (e.g. Gondwana versus Laurasia) and finer (e.g. Europe and Asia instead of Eurasia) scales for area coding, although the analyses reported here are confined to the four areas listed above.

We reconstructed ancestral areas using nine methods: (i) MAC parsimony, (ii) Fitch parsimony with multiple binary characters (FP-MBC), (iii) Fitch parsimony with a single multi-state character (FP-SMC), (iv) DIVA with no constraints on the maximum number of areas per node, (v) DIVA with a maximum of two areas per node (DIVA-2), (vi) DEC with no constraints on the maximum number of areas per node, (vii) DEC with a maximum of two areas per node (DEC-2), (viii) stochastic mapping with multiple binary characters (SM-MBC), and (ix) stochastic mapping with a single multi-state character (SM-SMC). Ancestral area chronograms (MAC parsimony) based on the geographical ranges of extant species and fossil lineages are shown in figures 3 and 4, respectively. Tables 3 and 4 summarize the results of analyses with all nine methods.

Table 1.

Fossil constraints. Minimum ages are based on the age of the oldest unequivocal fossils belonging to the clade. Maximum ages are based on the maximum of stratigraphic bounding [66], phylogenetic bracketing [67,68] and phylogenetic uncertainty. Stratigraphic bounding encompassed two successive underlying fossil-bearing deposits that did not contain any fossils from the lineage of interest, phylogenetic bracketing encompassed the age of the oldest fossils that were up to two nodes below the divergence event, and phylogenetic bracketing allowed for the possibility that taxa of uncertain phylogenetic affinities belong to the crown clade, first outgroup or second outgroup. Dates used in stratigraphic bounding are from Gradstein et al. [69]. We recognized the following chronological units in succession from youngest to oldest: Pleistocene, Pliocene, Late Miocene, Middle Miocene, Early Miocene, Late Oligocene, Early Oligocene, Late Eocene, Middle Eocene, Early Eocene, Late Palaeocene, Middle Palaeocene, Early Palaeocene, Maastrichtian and Campanian.

| node numbera | fossil constraints (Ma) |

oldest fossil for minimum | reference(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| minimum | maximum | |||

| 3 | 55.6 | 71.2 | Eritherium | [70] |

| 8 | 58.5 | 71.2 | Riostegotherium | [66,71] |

| 10 | 33.8 | 65.5 | Antarctic specimenb | [72,73] |

| 16 | 61.1 | 84.2 | Adunator | [74] |

| 19 | 37.1 | 65.8 | Hesperocyon gregarious | [75–77] |

| 21 | 55.5 | 61.1 | Hyracotherium | [78] |

| 32 | 48.4 | 61.1 | leporid tarsals | [79] |

| 34 | 48.4 | 61.1 | Eogliravus | [80] |

| 36 | 33.8 | 56 | Gaudeamus | [81,82] |

| 38 | 11.8 | 34 | Prodolichotis | [83] |

| 41 | 52.4 | 61.1 | Mattimys | [84] |

bThe Eocene Antarctic specimen is an ungual phalanx that Carlini et al. [72] identified as a megatheroid sloth. Marenssi et al. [85] revised the identification of the phalanx to include either Tardigrada (sloths) or Vermilingua (anteaters). Subsequently, Vizcaíno & Scillato-Yané [73] described a fragmentary tooth from the Eocene of Antarctica and referred this tooth to Tardigrada, but MacPhee & Reguero [86] reinterpreted this tooth fragment as Mammalia incertae sedis based on histological evidence.

Table 2.

Geographical area of extant taxa and oldest fossils used in ancestral area reconstruction.

| taxona | area of extant species | area of oldest fossilb |

|---|---|---|

| Choloepus didactylus | SA | SA; Megalonychidae; Miocene [87] |

| Tamandua tetradactyla | SA | SA; Tamandua; Pleistocene [87] |

| Myrmecophaga tridactyla | SA | SA; Neotamandua; Miocene [87,88] |

| Euphractus sexcinctus | SA | SA; Zaedyus; Pliocene [87,89] |

| Chaetophractus villosus | SA | SA; Chaetophractus; Pliocene [90] |

| Erinaceus europaeus | Eurasia | NA; Adunator; Palaeocene [74] |

| Talpa altaica | Eurasia | Eurasia; Eotalpa; Eocene [91] |

| Sorex araneus | Eurasia | NA; Domnina; Eocene [92] |

| Echinops telfairi | Africa | Africa; Widanelfarasia; Eocene [93] |

| Amblysomus hottentotus | Africa | Africa; Eochrysochloris; Oligocene [93] |

| Procavia capensis | Africa | Africa; Seggeurius; Eocene [94] |

| Loxodonta africana | Africa | Africa; Eritherium; Palaeocene [70] |

| Macroscelides proboscideus | Africa | Africa; Macroscelides; Pliocene [95] |

| Elephantulus rufescens | Africa | Africa; Elephantulus; Pliocene [95] |

| Orycteropus afer | Africa | Africa; Orycteropus; Miocene [96] |

| Tamias striatus | NA | NA; Spurimus; Eocene [97] |

| Muscardinus avellanarius | Eurasia | Eurasia; Eogliravus; Eocene [80] |

| Mus musculus | Eurasia | Eurasia; Progonomys; Miocene [74] |

| Rattus norvegicus | Eurasia | Eurasia; Karnimata; Miocene [74] |

| Pedetes capensis | Africa | Africa; Pondaungimys; Eocene [98] |

| Hystrix brachyurus | Eurasia | Africa; Gaudeamus; Eocene [81] |

| Castor canadensis | NA | NA; Mattimys; Eocene [84] |

| Dipodomys merriami | NA | NA; Proheteromys; Oligocene [99] |

| Cavia porcellus | SA | SA; Prodolichotis; Miocene [83,100] |

| Hydrochaeris hydrochaeris | SA | SA; Cardiatherium; Miocene [101] |

| Erethizon dorsatum | NA | SA; Eopululo; Eocene? [102] |

| Sylvilagus floridanus | NA; SA | Eurasia; tarsal elements; Eocene [79] |

| Ochotona princeps | NA | Eurasia; Sinolagomys; Oligocene [103,104] |

| Cynocephalus variegatus | Eurasia | Eurasia; Dermotherium; Eocene [105] |

| Tupaia minor | Eurasia | Eurasia; Eodendrogale; Eocene [106] |

| Lemur catta | Africa | Africa; Pachylemur; Quaternary [107] |

| Homo sapiens | Eurasia, NA; SA, Africa | Eurasia; Anthrasimias; Palaeocene [108] |

| Tarsius syrichta | Eurasia | Eurasia; Tarsius; Eocene [109] |

| Hippopotamus amphibius | Africa | Africa; Morotochoerus; Miocene [110] |

| Lama glama | SA | NA; Poebrodon; Eocene [111] |

| Tragelaphus eurycerus | Africa | Eurasia; Archaeomeryx; Eocene [112] |

| Sus scrofa | Eurasia, Africa | Eurasia; Eocenchoerus; Eocene [113] |

| Equus caballus | Eurasia | Eurasia, NA; Hyracotherium; Eocene [78,114,115] |

| Ceratotherium simum | Africa | NA; Hyracodontidae; Eocene [116] |

| Tapirus indicus | Eurasia | NA; Helaletes; Eocene [117] |

| Felis catus | Africa | Eurasia; Stenoplesictis; Eocene [118,119] |

| Canis familiaris | Eurasia | NA; Hesperocyon; Eocene [120] |

| Manis pentadactyla | Eurasia | Eurasia; Eomanis; Eocene [121] |

aIn cases of chimeric taxa, we used the most common species from Springer et al.'s [3] concatenated supermatrix. NA, North America; SA, South America.

bArea of the oldest stem fossil belonging to the terminal branch represented by each living taxon.

Figure 3.

Ancestral area chronogram for 43 placental taxa from Springer et al. [3] with area coding based on extant ranges for terminal taxa. RAxML was used to infer phylogenetic relationships, BEAST was used to infer divergence times, MAC parsimony was used to infer ancestral areas with the step matrix in figure 2. We employed soft constraints (nodes 3, 8, 10, 16, 19, 21, 32, 34, 36, 38, 41) that followed a normal distribution, with 95% of the normal distribution between the specified minimum and maximum constraints (table 1). Areas for extant taxa are enumerated in table 2 and are colour-coded as follows: Africa, blue; Eurasia, green; North America, brown; South America, red. Multi-coloured names denote taxa that occur in more than one area (table 2). Nodes with unambiguous ancestral area reconstructions are shown with a single coloured circle; nodes with ambiguous reconstructions are shown with two or more circles, and each coloured circle corresponds to a different reconstruction.

Figure 4.

Ancestral area chronogram for 43 placental taxa from Springer et al. [3] with area coding based on the oldest fossil for each lineage. RAxML was used to infer phylogenetic relationships, BEAST was used to infer divergence times, and MAC parsimony was used to infer ancestral areas with the step matrix in figure 2. Areas for the oldest fossil lineage are enumerated in table 2 and are colour-coded as follows: Africa, blue; Eurasia, green; North America, brown; South America, red. Nodes with unambiguous ancestral area reconstructions are shown with a single coloured circle; nodes with ambiguous reconstructions are shown with two or more circles, and each coloured circle corresponds to a different reconstruction.

Table 3.

Ancestral area reconstructions with areas coded for extant taxa. The order of coded areas in cells with character states is Africa, Eurasia, North America and South America. FP, Fitch parsimony; MBC, multiple binary characters; SMC, single multistate character; NC, no constraints on the maximum number of areas; MAC, minimum area change parsimony; DIVA, dispersal–vicariance with no constraints on the maximum number of areas; DIVA-2, dispersal–vicariance with the maximum number of areas per ancestral node set at 2; DEC, dispersal–extinction cladogenesis with no constraints on the maximum number of areas; DEC-2, dispersal–extinction cladogenesis with the maximum number of areas for each terminal taxon and ancestral range subdivision/inheritance scenario (‘split’) was set at 2, which required coding Homo as present in Africa and Eurasia only given that Homo sapiens inhabited these areas prior to inhabiting North America and South Americaa.

| clade | node no. (figure 3) | FP-MBC | FP-SMC | MAC | DIVA | DIVA-2 | DECb | DEC-2b | SM-MBC | SM-SMCc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placentalia | 1 | (01)000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1101 | 1100 | 0.90, 0.90, 0.58, 0.90 | 0.74, 0.59, 0.00, 0.15 | 0.87, 0.01, 0.00, 0.02 | 0.90, 0.08, 0.00, 0.02 |

| 0100 | 0100 | 1111 | 1001 | |||||||

| 0001 | 0001 | |||||||||

| 1100 | ||||||||||

| 1010 | ||||||||||

| Afrotheria | 2 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.93, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 |

| Paenungulata | 3 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.96, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 |

| Afroinsectiphilia | 4 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.98, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 |

| Afroinsectivora | 5 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 |

| Afrosoricida | 6 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 |

| Macroscelidea | 7 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 |

| Exafroplacentalia | 12 | 0000 | 1000 | 1000 | 0101 | 0101 | 0.12, 0.79, 0.57, 0.79 | 0.07, 0.93, 0.00, 0.23 | 0.01, 0.02, 0.00, 02 | 0.03, 0.71, 0.00, 0.26 |

| 0100 | 0100 | 1011 | ||||||||

| 0001 | 0001 | |||||||||

| Xenarthra | 8 | 0001 | 0001 | 0001 | 0001 | 0001 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.98 | 0.00, 0.16, 0.00, 0.85 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 1.00 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 1.00 |

| Dasypodidae | 9 | 0001 | 0001 | 0001 | 0001 | 0001 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 1.00 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.90 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 1.00 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 1.00 |

| Pilosa | 10 | 0001 | 0001 | 0001 | 0001 | 0001 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.99 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.93 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 1.00 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 1.00 |

| Vermilingua | 11 | 0001 | 0001 | 0001 | 0001 | 0001 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 1.00 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.99 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 1.00 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 1.00 |

| Boreoeutheria | 13 | 0(01)00 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0.12, 0.86, 0.60, 0.06 | 0.00, 0.84, 0.10, 0.00 | 0.01, 0.58, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 1.00, 0.00, 0.00 |

| 0110 | ||||||||||

| Laurasiatheria | 14 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0.00, 0.94, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.87, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.01, 0.99, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 1.00, 0.00, 0.00 |

| Eulipotyphla | 15 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0.00, 1.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.99, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 1.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 1.00, 0.00, 0.00 |

| Sorex + Erinaceus | 16 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0.00, 1.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 1.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 1.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 1.00, 0.00, 0.00 |

| Fereuungulata | 17 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0.00, 0.91, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.84, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.05, 0.85, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 1.00, 0.00, 0.00 |

| Ostentoria | 18 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0.00, 0.95, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.93, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.03, 0.95, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 1.00, 0.00, 0.00 |

| Caniformia | 19 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 1100 | 1100 | 0.56, 0.90, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.57, 0.98, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.24, 0.76, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.11, 0.89, 0.00, 0.00 |

| Euungulata | 20 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0.00, 0.89, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.81, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.22, 0.51, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.01, 0.99, 0.00, 0.00 |

| 1100 | 1100 | |||||||||

| 0101 | 0101 | |||||||||

| 1101 | ||||||||||

| Perissodactyla | 21 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0.27, 0.99, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.26, 0.97, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.03, 0.95, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.01, 0.99, 0.00, 0.00 |

| Ceratomorpha | 22 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 1100 | 1100 | 0.33, 0.94, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.26, 0.90, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.12, 0.88, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.04, 0.96, 0.00, 0.00 |

| Cetartiodactyla | 23 | 0(01)00 | 1000 | 0100 | 0101 | 0101 | 0.56, 0.64, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.63, 0.77, 0.00, 0.25 | 0.80, 0.02, 0.00, 0.01 | 0.56, 0.35, 0.00, 0.09 |

| 0100 | 1001 | 1001 | ||||||||

| 0001 | 1101 | |||||||||

| Sus + Bos + | 24 | 1(01)00 | 1000 | 1100 | 1000 | 1000 | 0.88, 0.73, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.91, 0.61, 0.00, 0.00 | 1.00, 0.02, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.97, 0.03, 0.00, 0.00 |

| Hippopotamus | 0100 | 1100 | 1100 | |||||||

| Bos + Hippopotamus | 25 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 0.99, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.97, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 |

| Euarchontoglires | 26 | 0(01)00 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0.10, 0.81, 0.61, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.94, 0.37, 0.00 | 0.01, 0.53, 0.01, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.99, 0.01, 0.00 |

| 0110 | 0110 | |||||||||

| Euarchonta | 27 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0.00, 0.78, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.98, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.03, 0.99, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.02, 0.98, 0.00, 0.00 |

| Paraprimates | 28 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0.00, 1.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 1.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 1.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 1.00, 0.00, 0.00 |

| Primates | 29 | (01)100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0.00, 0.66, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.87, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.92, 0.99, 0.02, 0.02 | 0.93, 0.07, 0.00, 0.00 |

| 1100 | ||||||||||

| Prosimii | 30 | (01)100 | 0100 | 0100 | 1100 | 1100 | 0.40, 0.86, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.27, 0.87, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.94, 0.70, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.98, 0.02, 0.00, 0.00 |

| 1100 | ||||||||||

| Glires | 31 | 0000 | 0100 | 0100 | 0010 | 0010 | 0.00, 0.40, 0.80, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.68, 0.74, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.01, 0.78, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.01, 0.99, 0.00 |

| 0010 | 0010 | 0110 | 0110 | |||||||

| Lagomorpha | 32 | 0010 | 0010 | 0010 | 0010 | 0010 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.86, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.89, 0.11 | 0.00, 0.00, 1.00, 0.17 | 0.00, 0.00, 1.00, 0.00 |

| Rodentia | 33 | 0000 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0.00, 0.48, 0.78, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.76, 0.76, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.44, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.00, 1.00, 0.00 |

| 0010 | 0010 | 0010 | 0010 | |||||||

| squirrel-related clade | 34 | 0000 | 0100 | 0100 | 0110 | 0110 | 0.00, 0.59, 0.78, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.78, 0.77, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.06, 0.46, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.11, 0.89, 0.00 |

| 0010 | 0010 | |||||||||

| mouse-related clade + | 35 | 0000 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0.00, 0.13, 0.52, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.44, 0.60, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.09, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.03, 0.97, 0.00 |

| Hystricognathi | 0010 | 0010 | 0010 | 0010 | ||||||

| Hystricognathi | 36 | 0000 | 0100 | 0100 | 0110 | 0110 | 0.00, 0.75, 0.75, 0.54 | 0.00, 0.62, 0.56, 0.18 | 0.00, 0.06, 0.02, 0.01 | 0.01, 0.34, 0.55, 0.11 |

| 0010 | 0010 | 0101 | 0101 | |||||||

| 1011 | ||||||||||

| Caviomorpha | 37 | 0000 | 0100 | 0100 | 0011 | 0011 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.82, 0.82 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.76, 0.65 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.13, 0.21 | 0.00, 0.01, 0.41, 0.58 |

| 0010 | 0010 | |||||||||

| 0001 | 0001 | |||||||||

| Cavioidea | 38 | 0001 | 0001 | 0001 | 0001 | 0001 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.97 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.91 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 1.00 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 1.00 |

| mouse-related clade | 39 | 0000 | 0100 | 0100 | 1100 | 1100 | 0.24, 0.40, 0.84, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.45, 0.66, 0.00 | 0.01, 0.00, 0.13, 0.00 | 0.05, 0.02, 0.93, 0.00 |

| 0010 | 0010 | 1010 | 1010 | |||||||

| 1110 | ||||||||||

| Castorimorpha + | 41 | 0000 | 0100 | 0100 | 0110 | 0110 | 0.00, 0.41, 0.87, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.46, 0.76, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.01, 0.69, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.02, 0.98, 0.00 |

| Muridae | 0010 | 0010 | ||||||||

| Castorimorpha | 40 | 0010 | 0010 | 0010 | 0010 | 0010 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.94, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.83, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.99, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.00, 1.00, 0.00 |

| Muridae | 42 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0.00, 0.87, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.85, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.99, 0.01, 0.00 | 0.00, 1.00, 0.00, 0.00 |

aFP, MAC, DIVA and DEC used an ML topology that was recovered by RAxML [65], but without the associated branch lengths. The RAxML analysis was performed with GTRMIXI, individual parameter estimates for each gene partition and 500 bootstrap replicates with the rapid bootstrap algorithm. Bootstrap analyses started from randomized MP starting trees, employed the fast hill-climbing algorithm and estimated free model parameters. ML analyses were run with the ‘-f a’ command, which combines bootstrap analysis with the search for the best ML tree(s) by using every fifth bootstrap tree as a starting tree to search for the ML tree(s) with the original dataset. DEC analyses were performed with the ultrametric tree shown in figure 3. Stochastic mapping analyses were performed with SIMMAP [5] using default settings, and used 3750 post-burnin trees that were sampled from a Bayesian analysis with MrBayes v. 3.1.1 [122,123]. Parameters of the Bayesian analysis included five million generations with sampling once every 1000 generations, four chains (three heated, one cold) and the same gene partitions that were used in Springer et al. [3]. The average standard deviation of split frequencies was <0.007 after completion of the five million generation chain for two independent runs.

bDEC records the likelihood and relative probability of ancestral range subdivision/inheritance scenarios (‘splits’) at internal nodes, and only shows splits that are within two log-likelihood units of the maximum for each node. Some ancestral area reconstructions contain the same ancestral areas for a given node, but have different splits. For example, the DEC-2 reconstruction for the base of Placentalia included three different splits as follows: Africa|Eurasia = 0.54; Africa|South America = 0.14; and Africa|Eurasia + Africa = 0.10. Both the first and the third splits contain Africa and Eurasia. The difference is that the first split assigns an area of Africa to the left-descendant branch and an area of Eurasia to the right-descendant branch, whereas the third split assigns an area of Africa to the left branch and an area of Africa + Eurasia to the right-descendant branch. However, both splits imply the same ancestral area (Africa + Eurasia) for the base of Placentalia. The relative probability that an ancestral area for Placentalia included Africa is the sum of all inheritance scenarios that contain Africa, i.e. 0.54 + 0.14 + 0.10 = 0.78.

cPolymorphic characters are not accommodated by SIMMAP. So for SM-SMC analyses, we arbitrarily chose a single area for taxa with multiple areas as follows: Homo (Africa, extant coding); Sus (Eurasia, extant coding); Sylvilagus (North America, extant coding); Equus (North America, extinct coding).

Table 4.

Ancestral area reconstructions with areas coded for fossil lineages. The order of coded areas in cells with character states is Africa, Eurasia, North America and South Americaa. Abbreviations as in table 3. Also see table 3 for an explanation of methodological details.

| clade | node no. (figure 4) | FP-MBC | FP-SMC | MAC | DIVA | DIVA-2 | DEC | DEC-2 | SM-MBC | SM-SMC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placentalia | 1 | (01)000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1101 | 1100 | 0.88, 0.88, 0.60, 0.88 | 0.78, 0.64, 0.00, 0.14 | 0.72, 0.01, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.86, 0.10, 0.01, 0.03 |

| 0100 | 0100 | 1111 | 1001 | |||||||

| 0001 | 0001 | |||||||||

| 1100 | ||||||||||

| 1010 | ||||||||||

| Afrotheria | 2 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.94, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 |

| Paenungulata | 3 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.97, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 |

| Afroinsectiphilia | 4 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.98, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 |

| Afroinsectivora | 5 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 |

| Afrosoricida | 6 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 |

| Macroscelidea | 7 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.99, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 1.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.00 |

| Exafroplacentalia | 12 | 0000 | 1000 | 1000 | 0101 | 0101 | 0.11, 0.84, 0.58, 0.84 | 0.07, 0.82, 0.00, 0.28 | 0.00, 0.01, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.03, 0.78, 0.01, 0.18 |

| 0100 | 0100 | 0111 | ||||||||

| 0001 | 0001 | |||||||||

| Xenarthra | 8 | 0001 | 0001 | 0001 | 0001 | 0001 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.98 | 0.00, 0.16, 0.00, 0.86 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 1.00 | 0.00, 0.01, 0.00, 0.99 |

| Dasypodidae | 9 | 0001 | 0001 | 0001 | 0001 | 0001 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 1.00 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.99 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 1.00 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 1.00 |

| Pilosa | 10 | 0001 | 0001 | 0001 | 0001 | 0001 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 1.00 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.94 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 1.00 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 1.00 |

| Vermilingua | 11 | 0001 | 0001 | 0001 | 0001 | 0001 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 1.00 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 1.00 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 1.00 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 1.00 |

| Boreoeutheria | 13 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0.00, 0.74, 0.45, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.85, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.67, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 1.00, 0.00, 0.00 |

| 0110 | ||||||||||

| Laurasiatheria | 14 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0.00, 0.88, 0.69, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.97, 0.28, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.21, 0.25, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.95, 0.05, 0.00 |

| 0010 | ||||||||||

| Eulipotyphla | 15 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0110 | 0110 | 0.00, 0.67, 0.86, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.84, 0.76, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.26, 0.65, 0.00 | 0.01, 0.37, 0.62, 0.01 |

| Sorex + Erinaceus | 16 | 0010 | 0010 | 0010 | 0010 | 0010 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.94, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.79, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.01, 0.99, 0.00 | 0.01, 0.02, 0.97, 0.01 |

| Fereuungulata | 17 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0.00, 0.81, 0.41, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.84, 0.11, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.44, 0.37, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.82, 0.18, 0.00 |

| 0010 | 0110 | |||||||||

| 0110 | ||||||||||

| Ostentoria | 18 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0.00, 0.97, 0.24, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.88, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.89, 0.08, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.94, 0.05, 0.00 |

| 0110 | ||||||||||

| Caniformia | 19 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0110 | 0110 | 0.00, 0.91, 0.70, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.85, 0.49, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.87, 0.13, 0.00 | 0.01, 0.87, 0.12, 0.01 |

| Euungulata | 20 | 01(01)0 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0.00, 0.67, 0.43, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.84, 0.22, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.07, 0.89, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.43, 0.56, 0.00 |

| 0010 | 0110 | 0010 | 0010 | |||||||

| 0110 | 0110 | |||||||||

| Perissodactyla | 21 | 0110 | 0100 | 0110 | 0010 | 0010 | 0.00, 0.53, 0.96, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.71, 0.93, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.74, 1.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.10, 0.90, 0.00 |

| 0010 | 0110 | 0110 | ||||||||

| Ceratomorpha | 22 | 0010 | 0010 | 0010 | 0010 | 0010 | 0.00, 0.00, 1.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.99, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.00, 1.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.00, 1.00, 0.00 |

| Cetartiodactyla | 23 | 01(01)0 | 0100 | 0100 | 0110 | 0110 | 0.19, 0.90, 0.79, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.86, 0.55, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.09, 0.33, 0.00 | 0.04, 0.46, 0.48, 0.01 |

| 0010 | 0110 | |||||||||

| Sus + Bos + Hippopotamus | 24 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0.24, 0.96, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.91, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.01, 0.82, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.06, 0.92, 0.01, 0.00 |

| Bos + Hippopotamus | 25 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 1100 | 1100 | 0.60, 0.92, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.35, 0.91, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.29, 0.71, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.29, 0.69, 0.01, 0.01 |

| Euarchontoglires | 26 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0.00, 0.86, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.92, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.91, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 1.00, 0.00, 0.00 |

| Euarchonta | 27 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0.00, 0.99, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.99, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 1.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 1.00, 0.00, 0.00 |

| Paraprimates | 28 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0.00, 1.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 1.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 1.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 1.00, 0.00, 0.00 |

| Primates | 29 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0.00, 0.94, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.95, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.01, 0.99, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.99, 0.00, 0.00 |

| Prosimii | 30 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 1100 | 1100 | 0.46, 0.93, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.28, 0.90, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.30, 0.70, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.30, 0.68, 0.01, 0.01 |

| Glires | 31 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0.00, 0.74, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.89, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.81, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.99, 0.01, 0.00 |

| Lagomorpha | 32 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0.00, 1.00, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.99, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.98, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.01, 0.98, 0.01, 0.00 |

| Rodentia | 33 | 0(01)00 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0.41, 0.80, 0.25, 0.00 | 0.30, 0.90, 0.09, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.03, 0.00 | 0.05, 0.23, 0.71, 0.02 |

| 1100 | 1100 | |||||||||

| 1110 | ||||||||||

| squirrel-related clade | 34 | 0(01)00 | 0100 | 0100 | 0110 | 0110 | 0.00, 0.84, 0.55, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.87, 0.30, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.03, 0.35, 0.00 | 0.02, 0.15, 0.81, 0.01 |

| mouse-related clade + | 35 | 0000 | 0100 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 0.76, 0.76, 0.32, 0.00 | 0.59, 0.69, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.01, 0.00 | 0.19, 0.04, 0.71, 0.06 |

| Hystricognathi | 1000 | 0100 | 1100 | 1100 | ||||||

| 1100 | 1110 | 0101 | ||||||||

| 0101 | ||||||||||

| 1101 | ||||||||||

| 0111 | ||||||||||

| 1111 | ||||||||||

| Hystricognathi | 36 | 0000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1001 | 1001 | 0.85, 0.00, 0.00, 0.85 | 0.65, 0.10, 0.00, 0.75 | 0.08, 0.00, 0.00, 0.26 | 0.28, 0.02, 0.03, 0.67 |

| 0100 | 0100 | |||||||||

| 0001 | 0001 | |||||||||

| Caviomorpha | 37 | 0001 | 0001 | 0001 | 0001 | 0001 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.97 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.93 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 1.00 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 1.00 |

| Cavioidea | 38 | 0001 | 0001 | 0001 | 0001 | 0001 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 1.00 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 0.99 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 1.00 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.00, 1.00 |

| mouse-related clade | 39 | 0000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1100 | 1100 | 0.78, 0.78, 0.58, 0.00 | 0.59, 0.69, 0.08, 0.00 | 0.03, 0.00, 0.06, 0.00 | 0.31, 0.04, 0.64, 0.02 |

| 0100 | 0100 | 1010 | 1010 | |||||||

| 1100 | 1110 | |||||||||

| Castorimorpha + | 41 | 0000 | 1000 | 1000 | 0110 | 0110 | 0.00, 0.73, 0.73, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.71, 0.44, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.01, 0.69, 0.00 | 0.02, 0.06, 0.92, 0.00 |

| Muridae | 0100 | 0100 | ||||||||

| 0010 | 0010 | |||||||||

| Castorimorpha | 40 | 0010 | 0010 | 0010 | 0010 | 0010 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.88, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.31, 0.89, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.00, 0.99, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.01, 0.99, 0.00 |

| Muridae | 42 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0100 | 0.00, 0.97, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.94, 0.00, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.99, 0.01, 0.00 | 0.00, 0.98, 0.01, 0.00 |

Ambiguous ancestral area reconstructions were a problem for all methods, and the number of nodes with equivocal reconstructions ranged from four (SM-SMC with extant coding) to 26 (DEC-2 with extant coding). For some methods, the number of ambiguous nodes was higher with extant coding than with fossil coding (FP-MBC, FP-SMC, MAC parsimony, DIVA, DIVA-2, DEC, DEC-2), but in other cases, this pattern was reversed (SM-MBC, SM-SMC). Ancestral areas for Placentalia, Exafroplacentalia (=Boreoeutheria + Xenarthra) and several nodes within Rodentia were reconstructed as ambiguous by nearly all methods. Other nodes were consistently reconstructed with unambiguous ancestral areas, including clades with ancestral areas in Africa (Afrotheria and its internal nodes), Eurasia (Euarchonta, Paraprimates [=Dermoptera + Scandentia], Muridae), North America (Erinaceidae + Soricidae) and South America (Xenarthra and its internal nodes, Cavioidea). Most analyses reconstructed Eurasia as the ancestral area for Boreoeutheria, Laurasiatheria and Euarchontoglires. This finding is discussed below.

The importance of fossils is illustrated by reconstructions for Lagomorpha (tables 3 and 4). All methods returned North America as the ancestral area when extant taxa were used for area coding, but identified Eurasia with fossil coding.

DIVA and DEC analyses reconstructed more nodes with multiple areas than did the other methods. Analyses with DEC reconstructed 17–20 nodes with two or more areas and four to six nodes with three or more areas. DIVA analyses resulted in 15–18 nodes with at least two areas, and five to six nodes with three or more areas. None of the other methods reconstructed ancestral nodes to include three or more areas in a single reconstruction, although three or four areas were sometimes represented by the full complement of alternate reconstructions for a given node.

FP-MBC returned nine empty nodes with extant coding, and five empty areas with fossil coding. SM-MBC with extant coding resulted in three or four empty nodes with extant coding, and four empty nodes with extinct coding (table 5).

Table 5.

Comparison of different methods for reconstructing ancestral areas. NA1, not applicable for monomorphic reconstruction methods; NA2, not applicable when the maximum number of areas is set at two; NA2, not applicable for methods that employ single multistate charactersa.

| FP-MBC | FP-SMC | MAC Parsimony | DIVA | DIVA-2 | DEC | DEC-2 | SM-MBC | SM-SMC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nodes with ambiguous | 7/5 | 12/9 | 12/8 | 12/11 | 10/7 | 23/23 | 26/23 | 16/17 | 6/14 |

| reconstructionsb | 19/20 | 17/18 | 10/12 | 4/10 | |||||

| nodes with ≥ 2 areasc | 3/3 | NA1 | 4/6 | 16/18 | 15/16 | 18/20 | 20/19 | 7/7 | NA1 |

| 17/20 | 17/17 | 4/6 | |||||||

| nodes with ≥ 3 areasd | 0/0 | NA1 | 0/0 | 6/5 | NA2 | 6/6 | NA2 | 0/0 | NA1 |

| 4/5 | 0/0 | ||||||||

| empty nodese | 9/5 | NA3 | NA3 | NA3 | NA3 | NA3 | NA3 | 3/4 | NA3 |

| 4/4 |

aNumbers before slashes are based on analyses with area coding for extant taxa, and numbers after slashes are based on analyses with area coding for the oldest fossil. See table 3 for abbreviations.

bFor FP-MBC, nodes were considered ambiguous if at least one area was reconstructed as (01). For SM-MBC and SM-SMC, nodes were considered ambiguous if the posterior probability (PP) of at least one area was 0.1 < PP < 0.9 (top line) or 0.2 < PP < 0.8 (bottom line). For DEC and DEC-2, nodes were considered ambiguous if the frequency (f) of at least one area was 0.1 < f < 0.9 (top line) or 0.2 < p < 0.8 (bottom line).

cAt least two areas in at least one of the alternate resolutions for an ancestral node. For FP-MBC, each occurrence of 1 or (01) was taken to include an ancestral area. For SM-MBC, areas were counted as present at a node if posterior probabilities were ≥0.10 (top line) or ≥0.20 (bottom line). For DEC and DEC-2, areas were counted as present at a node if frequencies were ≥0.1 (top line) or ≥0.2 (bottom line).

dAt least three areas in more than one of the alternate resolutions for an ancestral node. For FP-MBC, each occurrence of 1 or (01) was taken to include an ancestral area. For SM-MBC, areas were counted as present at a node if posterior probabilities were ≥0.10 (top line) or ≥0.20 (bottom line). For DEC and DEC-2, areas were counted as present at a node if frequencies were ≥0.1 (top line) or ≥0.2 (bottom line).

eFor FP-MBC, nodes were considered empty if all areas were reconstructed as 0. For SM-MBC, nodes were considered empty if posterior probabilities were <0.10 (top line) or <0.20 (bottom line) for all four areas.

7. Placental biogeography

Afrotheria (Afrosoricida, Hyracoidea, Macroscelidea, Proboscidea, Sirenia, Tubulidentata) was the first of the new superordinal groups to receive robust molecular support [53,55,56]. With the exception of Sirenia, all afrotherian orders have first fossil occurrences in Africa, and two orders (Macroscelidea, Afrosoricida) have evolutionary histories that are restricted to the Afro-Malagasy region. Springer et al. [53] suggested that interordinal separation of afrotherian orders commenced during a window of isolation that began in the Cretaceous, after Africa separated from South America, and lasted until the early Cenozoic when Africa docked with Europe. Consistent with this scenario, Africa was unambiguously reconstructed as the ancestral area for Afrotheria (figures 3 and 4). This hypothesis contrasts with traditional views wherein the African mammal fauna arrived from the north, including a condylarth stock that arrived in Africa from Europe in the early Cenozoic, and insectivores that arrived in the Neogene [124].

Asher et al. [125], Zack et al. [126] and Tabuce et al. [127] suggested that the geographical distributions of living afrotherians are not representative of the historical geographical distribution of this clade, and that Afrotheria is Holarctic in origin based on the placement of extinct taxa from the Palaeocene of Laurasia within or at the base of Afrotheria. However, pseudoextinction tests call into question the reliability of the placement of fossil taxa in morphological cladistic analyses [3].

The oldest xenarthran fossils are scutes from the Palaeocene of South America [71]. Living members of Xenarthra (anteaters, sloths, armadillos) are restricted to South and Central America with the exception of the nine-banded armadillo, whose ancestors dispersed to North America during the Great American Interchange [128]. Simpson [129,130] supported the view that South American xenarthrans evolved in situ during South America's isolation from other continents in the early Tertiary. All of our analyses are consistent with the hypothesis that South America was the ancestral area for Xenarthra (figures 3 and 4).

The remaining placental orders are placed in Laurasiatheria (Eulipotyphla, Chiroptera, Perissodactyla, Cetartiodactyla, Carnivora, Pholidota) and Euarchontoglires (Primates, Dermoptera, Scandentia, Rodentia, Lagomorpha). With the exception of bats, these orders have first fossil occurrences that are exclusively Laurasian. Our reconstructions provide support for Eurasia, but not North America, as the ancestral area for these clades (figures 3 and 4). These results are consistent with previous suggestions that Cretaceous zhelestids and zamlambdalestids from Asia are members of crown Placentalia [131,132]. Further, the fossil record suggests that Eutheria were dominant in Eurasia throughout the Cretaceous, but were absent from North America through much of the Late Cretaceous and only attained appreciable diversity there during the last approximately 10 Myr of the period [133,134]. Boyer et al. [135] concluded that the Indian subcontinent, Eurasia and Africa are more likely places of origin for Euarchonta than is North America. This agrees with our ancestral area reconstructions (figures 3, 4 and tables 3, 4).

Although there is robust support for the monophyly of Xenarthra, Afrotheria and Boreoeutheria, relationships among these three groups and the root of the placental tree remain contentious [10,54,60–63,136]. Murphy et al. [62] and Springer et al. [10] suggested a causal relationship between the sundering of Africa and South America, and basal cladogenesis among crown-group placental mammals given the coincidence of molecular dates for the base of placentals and the vicariant separation of Africa and South America approximately 100–120 Ma.

Asher et al. [125] analysed a combined matrix and recovered Afrotheria in a nested position within Placentalia, which contradicts the hypothesis that the plate tectonic separation of Africa and South America played a causal role in the early cladogenesis of placental mammals. However, the nested position for Afrotheria resulted from the paraphyly of Euarchontoglires, Glires and Rodentia. Rare genomic changes confirm the monophyly of Xenarthra [137], Afrotheria [138–142], Euarchontoglires [139,141,142], Laurasiatheria [139,141,142] and Boreoeutheria [139,141,142], and preclude a nested position for Afrotheria in the placental tree.

Rare genomic changes have also been used to examine the position of the placental root. Kriegs et al. [139] reported LINE insertions that are shared by Epitheria, whereas Murphy et al. [16] discovered rare genomic changes that support Atlantogenata. Nishihara et al. [142] performed genome-wide retroposon analyses and found 22, 25 and 21 LINE insertions for Exafroplacentalia, Epitheria and Atlantogenata, respectively. Based on these results, Nishihara et al. [142] concluded that Xenarthra, Afrotheria and Boreoeutheria diverged from one another nearly simultaneously. They also suggested a new palaeogeographical model for the breakup of Pangaea and Gondwana in which Africa becomes isolated from both South America and Laurasia at approximately 120 Ma, and argued that these coeval plate tectonic events provide an explanation for the simultaneous divergence of Afrotheria, Xenarthra and Boreoeutheria. However, relaxed clock dates for the base of Placentalia are closer to 100 Ma than to 120 Ma (figures 3 and 4). A second difficulty concerns the opening of the South Atlantic. Nishihara et al. [142] suggested that the Brazilian Bridge, which represented the last connection between Africa and South America, was severed at approximately 120 Mya, but other recent reconstructions suggest that the connection between the South Atlantic and Central Atlantic was not established until late Aptian/mid-Albian times (approx. 110–100 Ma) [143,144].

8. The importance of dispersal

In the context of pre-plate tectonic views of the Earth, Simpson [2] proposed three types of migration routes to describe the movement of animals: corridors, filter bridges and sweepstakes dispersal. Corridors connect two areas and are permeable to all animals; filter bridges impose selective barriers that affect some, but not all animals; and sweepstakes dispersal is required when there are strong barriers to migration such as high mountain barriers or oceans.

Simpson [2] suggested that Madagascar's living mammals were the product of sweepstakes dispersal from Africa to Madagascar. Sweepstakes dispersal hypotheses fell out of favour with the validation of plate tectonic theory and were summarily dismissed as ‘miraculous’ hypotheses with no scientific basis [145]. However, it has become apparent that some distributional patterns can only be explained by sweepstakes dispersal [146]. Observational data also provide support for long-distance vertebrate dispersal [147]. Examples of low probability sweepstakes dispersal involving mammals include the origins of the endemic mammal fauna in Madagascar, and the occurrence of caviomorph rodents and platyrrhine primates in South America.

Madagascar's strictly terrestrial extant mammal fauna includes endemic lineages from four placental orders: tenrecs (Afrosoricida), euplerids (Carnivora), nesomyines (Rodentia) and lemurs (Primates). In each lineage, Madagascar endemics comprise monophyletic assemblages with closest living relatives in Africa [148,149]. Madagascar separated from Africa approximately 165 Ma, but maintained its connection with Antarctica via the Kerguelen Plateau until as late as 80 Ma, at which time it became permanently separated from other Gondwanan landmasses. This history suggests that Madagascar's terrestrial endemic mammals are either the ancient descendants of vicariant events that occurred prior to 80 Ma, or reached Madagascar via transoceanic sweepstakes dispersal at a later time. Another possibility is that a land bridge connected Africa and Madagascar between 45 and 26 Ma [150].

Molecular divergence dates suggest that all four endemic lineages last shared a common ancestor with their African sister group in the Cenozoic [148,149,151,152]. Poux et al. [148] concluded that dispersal by lemurs, rodents and carnivorans must have occurred by transoceanic dispersal rather than land bridge dispersal based on molecular dates for the colonization of Madagascar that were outside of the land bridge window, i.e. 60–50 Ma for lemurs, 26–19 Ma for carnivorans and 24–20 Ma for rodents. However, present ocean currents allow for dispersal from Madagascar to Africa, but oppose reciprocal dispersal from Africa to Madagascar across the Mozambique Channel. If ocean currents were the same for most of the Cenozoic as they are today, they would not have facilitated west to east transoceanic dispersal across the Mozambique Channel because of the strong south–southwest flow of the Mozambique Current [153].

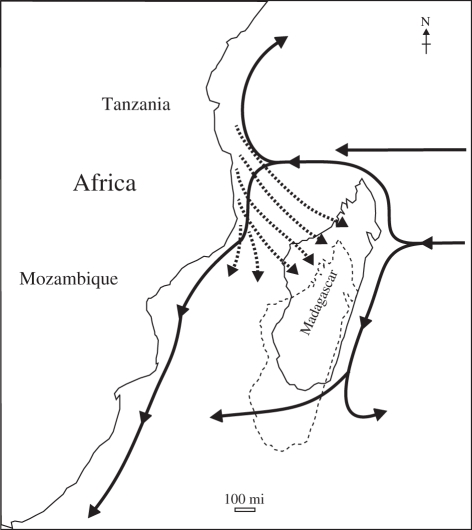

Ali & Huber [154] addressed this problem by simulating surface ocean currents in the Indian Ocean during the Eocene. They concluded that large-scale ocean current systems in the Eocene were profoundly different from modern observed circulatory patterns, and that the flow along the African coast was eastward towards Madagascar instead of southward through the Mozambique Channel (figure 5). Ali & Huber [154] further suggested that dispersal probabilities were enhanced by tropical storms that (i) generated large, floating tree islands that would have allowed for a successful oceanic voyage and (ii) accelerated transportation rates from Africa to Madagascar that would have allowed for complete crossing of the Mozambique Channel in 25–30 days.

Figure 5.

Present day surface ocean currents in the Mozambique Channel (solid arrows) are south–southwest and would not have facilitated west to east transoceanic dispersal from Africa to Madagascar [153]. By contrast, westerly surface ocean currents in the Eocene (dashed arrows) would have facilitated dispersal across the Mozambique Channel from Africa to Madagascar, especially during tropical storms [154]. The outline of Madagascar with dashed lines shows its approximate position relative to Africa during the Eocene.

The dispersal of four groups of fully terrestrial mammals from Africa to Madagascar, at a time when there was no land bridge, is a testament to the importance of rare sweepstakes events in the evolutionary history of Placentalia. Even more remarkable is the occurrence of two different groups of placental mammals, hystricognath rodents and anthropoid primates, in Africa and South America.

Hystricognathi includes Hystricidae (Old World porcupines) and Phiomorpha (e.g. cane rats, dassie rats) from the Old World, and Caviomorpha (e.g. porcupines, chinchillas) from the New World. The oldest hystricognaths are from the late Eocene Egypt, and have been dated at approximately 37 Ma [81]. Old World hystricognaths are paraphyletic, usually with phiomorphs having closer phylogenetic affinities to South American caviomorphs than to hystricids [14,155,156]. Relaxed clock dates suggest that South American caviomorphs last shared a common ancestor with phiomorphs between 45 and 36 Ma [81,155,157]. The most recent common ancestor of Caviomorpha has been dated at 45–31 Ma [81,155,157,158].

Among anthropoids, Old World catarrhines (e.g. macaques, apes) and South American platyrrhines (e.g. marmosets, capuchins, spider monkeys) are reciprocally monophyletic sister taxa. The oldest anthropoid fossils are from the Old World, although whether the most recent common ancestor of Anthropoidea is African or Asian is uncertain [108,159,160]. Poux et al. [155] dated the split between catarrhines and platyrrhines at approximately 37 Ma and the base of Platyrrhini at approximately 17 Ma.

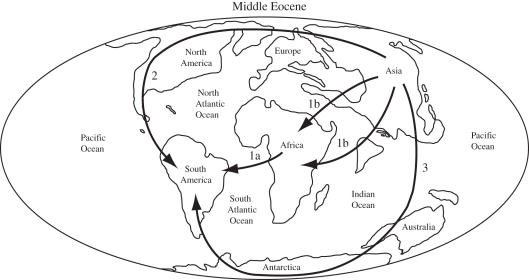

The vicariant separation of Africa and South America (110–100 Ma) is too old to explain the separation of either Phiomorpha and Caviomorpha, or Catarrhini and Platyrrhini. Similarly, Arnason et al.'s [161] hypothesis of land bridge dispersal during the Late Cretaceous–Early Palaeocene is too old for relaxed clock dates, which instead rule out the colonization of South America by Caviomorpha and Platyrrhini prior to the Eocene. Other hypotheses for the colonization of South America by caviomorphs and/or platyrrhines include: (i) trans-Atlantic dispersal from Africa to South America [162], (ii) dispersal from Asia through North America to South America [163,164], and (iii) dispersal from Asia to South America via Australia and Antarctica after two ocean crossings (figure 6) [165].

Figure 6.

Alternate hypotheses for the dispersal of platyrrhine and caviomorph ancestors, respectively, from Africa/Asia to South America. Hypothesis 1: transoceanic dispersal (1a) from Africa to South America, possibly with an earlier dispersal from Asia to Africa (1b) if origination occurred in Asia. Hypothesis 2: dispersal from Asia through North America to South America. Hypothesis 3: dispersal from Asia to South America via Australia and Antarctica after two transoceanic crossings. Middle Eocene world map based on Palaeomap Project (http://www.scotse.com/newpage9.htm).

Most workers favour transoceanic dispersal from Africa to South America for both Caviomorpha and Platyrrhini. Dispersal through Asia and North America is an intriguing possibility, but palaeontological data provide no support for migrations through North America. Similarly, dispersal from Asia to South America through Australia and Antarctica lacks palaeontological support, requires multiple transoceanic dispersals and becomes even less likely after the Eocene because of the severed connection between Antarctica and South America, and climatic deterioration in Antarctica associated with the opening of the Drake Passage. In view of phylogenetic, geological, palaeontological and molecular data, trans-Atlantic dispersal is the most likely scenario for colonization of South America by caviomorphs and platyrrhines.

9. Bat biogeography

In contrast to other mammals, bats are capable of powered flight, which has profoundly enhanced their dispersal capabilities. The occurrence of seven different families of extant bats in Madagascar, including the endemic sucker-footed bats (Family Myzopodidae), and of another family in New Zealand, the short-tailed bats (Family Mystacinidae), provides abundant evidence of the dispersal capabilities of bats [166].

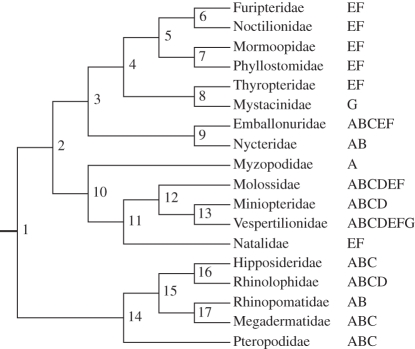

The oldest bat fossils are from the Early Eocene of North America [167,168]. Early Eocene bats are also known from Europe, Africa and Australia [167]. The prevalent view is that bats originated in Laurasia, but a minority view holds that bats originated in Gondwana [169,170]. Teeling et al. [13] reconstructed ancestral areas for bats with (i) multistate-coded data for the current global distribution of each lineage with nine different character states (Europe, Africa, Asia, Madagascar, Australia, New Zealand, North America, Central + South America and West Indies) and (ii) binary-coded data for the earliest fossil occurrence for each lineage (Laurasia versus Gondwana). Teeling et al.'s [13] results suggested North America or Laurasia as the ancestral area for bats, and Asia, Europe or Laurasia as the ancestral area for both Yinpterochiroptera and Yangochiroptera. Eick et al. [12] used DIVA [33] to estimate ancestral areas for Chiroptera and its subclades, and coded areas based on current distributions for each family. Seven areas (Africa, Asia, Australia, Europe, North America, South America and New Zealand) were recognized, and Africa was reconstructed as the ancestral area for the most recent common ancestors of Chiroptera, Yinpterochiroptera and Yangochiroptera. Lim [47] used parsimony to reconstruct ancestral areas, and also recovered Africa as the ancestral area for Yangochiroptera and its deepest nodes.

We recovered more inclusive ancestral areas for Chiroptera, Yinpterochiroptera and Yangochiroptera when we performed analyses with DIVA using the same data and settings that were reported by Eick et al. [12] (figure 7 and table 6). The reconstruction for the base of Chiroptera was equivocal and included seven different possibilities, all of which were equally parsimonious based on DIVA's criteria for minimizing dispersal and extinction (figure 7 and table 6). Each of these reconstructions included at least five areas, and four areas (Africa, Asia, North America and South America) were common to all seven reconstructions.

Figure 7.

Eick et al.'s [12] phylogeny and area coding for extant bat families. Ancestral area reconstructions based on DIVA analyses are shown in table 6 for nodes 1–17. Africa, A; Asia, B; Australia, C; Europe, D; North America, E; South America, F; New Zealand, G.

Table 6.

A comparison of ancestral area reconstructions for bats based on DIVA analyses. Eick et al. [12] coded the presence or absence of extant bat families in seven different areas and performed DIVA analyses with no constraints on the maximum number of areas. We re-analysed Eick et al.'s [12] dataset with DIVA using the same settings reported by these authors. Africa, A; Asia, B; Australia, C; Europe, D; North America, E; South America, F; New Zealand, G.

| node number (figure 7) | Eick et al. [12] | re-analysis |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | A | ABCEF, ABDEF, ABCDEF, ABEFG, ABCEFG, ABDEFG, ABCDEFG |

| 2 | A | ACEF, BCEF, ABCEF, DEF, ADEF, BDEF, ABDEF, ACDEF, BCDEF, ABCDEF, AEFG, ABEFG, ACEFG, BCEFG, ABCEFG, DEFG, ADEFG, BDEFG, ABDEFG, ACDEFG, BCDEFG, ABCDEFG |

| 3 | AE, AF | E, AE, BE, CE, ACE, BCE, ABCE, F, AF BF, CF, ACF, BCF, ABCF, CEF, ACEF, BCEF, ABCEF, AG, BG, CG, ACG, BCG, ABCG AEG, BEG, CEG, ACEG, BCEG, ABCEG, AFG, BFG, CFG, ACFG, BCFG, ABCFG, AEFG, BEFG, CEFG, ACEFG, BCEFG, ABCEFG |

| 4 | E, F | E, F, EG, FG, EFG |

| 5 | E, F | E, F |

| 6 | E, F | E, F |

| 7 | E, F | E, F |

| 8 | EG, FG, EFG | EG, FG, EFG |

| 9 | A | A, B, AC, BC, ABC, AE, BE, ABE ACE, BCE, ABCE, AF, BF, ABF, ACF, BCF, ABCF, AEF, BEF, ABEF, ACEF, BCEF |

| 10 | A | A, AC, AD, ACD, ABCD, ACE, ADE ACDE, ABCDE, ACF, ADF, ACDF, ABCDF, ACEF, ADEF, ACDEF, ABCDEF, ACDEG ABCDEG, ACDFG, ABCDFG, ACDEFG, ABCDEFG |

| 11 | AE, AF, AEF | AE, CE, DE, CDE, ACDE, BCDE ABCDE, AF, CF, DF, CDF, ACDF, BCDF, ABCDF, AEF, CEF, DEF, CDEF, ACDEF BCDEF, ABCDEF, CDEG, ACDEG, BCDEG, ABCDEG, CDFG, ACDFG, BCDFG, ABCDFG, CDEFG, ACDEFG, BCDEFG, ABCDEFG |

| 12 | A | A, C, D, CD, ACD, BCD, ABCD, CDE ACDE, BCDE, ABCDE, CDF, ACDF, BCDF, ABCDF, CDEF, ACDEF, BCDEF, ABCDEF, CDG ACDG, BCDG, ABCDG, CDEG, ACDEG, BCDEG, ABCDEG, CDFG, ACDFG, BCDFG, ABCDFG, CDEFG, ACDEFG, BCDEFG, ABCDEFG |

| 13 | A | A B C, D, AG, BG, ABG, CG, ACG BCG, ABCG, DG, ADG, BDG, ABDG, CDG, ACDG, BCDG, ABCDG, AEG, BEG, ABEG, CEG ACEG, BCEG, ABCEG, DEG, ADEG, BDEG, ABDEG, CDEG, ACDEG, BCDEG, ABCDEG, AFG, BFG, ABFG, CFG, ACFG, BCFG, ABCFG, DFG, ADFG, BDFG, ABDFG, CDFG, ACDFG BCDFG, ABCDFG, AEFG, BEFG, ABEFG, CEFG, ACEFG, BCEFG, ABCEFG, DEFG, ADEFG, BDEFG, ABDEFG, CDEFG, ACDEFG, BCDEFG, ABCDEFG |

| 14 | A | A, B, C, AC, BC, ABC |

| 15 | A | A, B, C, AC, BC |

| 16 | A | A, B, C |

| 17 | A | A, B, AC, BC, ABC |

Among the most comprehensive studies in mammalian historical biogeography are Lim's [46,47] analyses of South American bats. Ancestral reconstructions provided evidence for multiple dispersals from Africa to South America. One dispersal occurred in Noctilionoidea (Eocene, approx. 42 Ma) and another occurred in Emballonuroidea (Oligocene, approx. 30 Ma). Vespertilionoidea have a more complex history that involves numerous independent dispersals from Africa (Eocene, earliest event approx. 50 Ma), as well as from North America. Lim [46] used PACT to examine evolutionary processes that have been important in the diversification of South American emballonurids. His general area cladogram revealed a complex history with multiple vicariant, within-area and dispersal events all playing a role. Within-area speciation during the Miocene, particularly in the northern Amazon area, was the most important diversification process in this group. Lim [47] correlated Miocene speciation with contemporaneous climatic and habitat changes that occurred in the Amazon Basin. Construction of an ancestral area cladogram for all bat species will provide an unprecedented opportunity to examine the importance of transoceanic dispersal in promoting taxonomic diversity in this highly successful group of mammals.

10. Marsupial biogeography

The oldest metatherian is Sinodelphys from China [171]. Cretaceous marsupial fossils are also known from Europe [172,173] and North America [174–178]. The consensus is that metatherians originated in Asia, and subsequently dispersed to North America and Europe [173].

In contrast to the Cretaceous record of Metatheria, almost all living metatherians have geographical distributions that are entirely Gondwanan. Case et al. [179] suggested that the ancestor of living marsupials dispersed to South America in the Late Cretaceous or early Palaeocene. The South American marsupial cohort Ameridelphia, which includes Paucituberculata (shrew opossums) and Didelphimorphia (opossums), is paraphyletic at the base of Australidelphia, which includes the South American order Microbiotheria (monito del monte), and the Australasian orders Diprotodontia (e.g. wombats, kangaroos), Dasyuromorphia (e.g. quolls, numbats), Peramelemorphia (e.g. bandicoots, bilbies) and Notoryctemorphia (marsupial moles) [17,21,180–182].

Subsequent to Kirsch et al.'s [183] single-copy DNA hybridization study of marsupials, which placed South American microbiotheres within Australidelphia, marsupial biogeographers have focused on the monophyly or paraphyly of Australasian taxa. Australasian monophyly is consistent with a single dispersal from South America to Australia via Antarctica, but Australasian paraphyly requires either multiple dispersals to Australia, or dispersal to Australia followed by back dispersal to South America [183–185]. Molecular phylogenies based on concatenated nuclear gene sequences [21,182] and retroposon insertions [186] support the monophyly of Australasian marsupials, and suggest that Australasian marsupials last shared a common ancestor with microbiotheres between 65 and 58 Ma. This phylogeny is compatible with a single dispersal event from South America to Australia via Antarctica [21]. This dispersal would have been overland if it occurred prior to the complete submergence of the South Tasman Rise approximately 64 Ma [187].

In contrast, Beck et al. [181] analysed a dataset comprising living and fossil taxa, including the early Eocene genus Djarthia from Australia, and recovered a sister-group relationship between Djarthia and living australidelphians. Beck et al.'s [181] topology suggest that South American microbiotheres back-dispersed from eastern Gondwana to South America even though living Australasian marsupials comprise a monophyletic taxon. However, the decay index that associates crown Australidelphia to the exclusion of Djarthia is only one step. This result highlights the potential importance of fossils for inferring biogeographic history, and the precarious nature of conclusions based on a fragmentary fossil record.

11. Monotreme biogeography

Living monotremes include the semi-aquatic platypus (Ornithorhynchus), which occurs in Australia and Tasmania, and echidnas, which occur in Australia (Tachyglossus) and New Guinea (Zaglossus). The oldest monotreme is Teinolophos (121–112.5 Ma) of Australia. Rowe et al. [188] suggested that Teinolophos is a crown monotreme based on cladistic analyses.