Abstract

Two studies show that different culturally based concepts of interpersonal power have distinct implications for information processing. People with a vertical individualist (VI) cultural orientation view power in personalized terms (power is for gaining status over and recognition by others), whereas people with a horizontal collectivist (HC) cultural orientation view power in socialized terms (power is for benefitting and helping others). The distinct goals associated with these power concepts are served by different mindsets, such as stereotyping others versus learning the individuating needs of others. Therefore, for high-VI individuals, making personalized power salient increases stereotyping in processing product information. That is, they recognize better information that is congruent with their prior product expectations, relative to their recognition of incongruent information. In contrast, for high-HC people, making socialized power salient increases individuating processes, characterized by better memory for incongruent information.

Keywords: Power, Cultural Values, Mindsets, Information-Processing

Interpersonal power is a central aspect of social interactions and an increasing focus of research attention (Guinote & Vescio, 2010). Often defined as the ability to influence others or control others’ outcomes (Fiske, 1993), power affects one’s propensity to take action and one’s perceptions of other people (Fiske, 1993)1. Research suggests that having power over others triggers cognitive processes that facilitate the fulfillment of one’s salient goals (e.g., Brinol, Petty, Valle, Rucker, & Becerra, 2007; Guinote, 2007b; Rucker, Dubois, & Galinsky, 2010; Rucker & Galinsky, 2009) and, in turn, maintain one’s powerful status (Fiske, 1993). This inward focus triggered by power is aligned with the widespread perceptions that powerful people are insensitive to the needs of others and behave selfishly in the pursuit of their personal goals (Galinsky, Magee, Inesi, & Gruenfeld, 2006; Gruenfeld, Inesi, Magee, & Galinsky, 2008; Kipnis, 1976). Indeed, a substantial body of research shows that power-holders often judge other people by means of intuitive, stereotyping processes aimed at confirming their prior expectations about others (Fiske, 1993, 2001; Goodwin, Operario, & Fiske, 1998; Overbeck, 2010).

However, recent findings also show that power-holders sometimes devote effort to individuating and making sense of others (Goodwin, Gubin, Fiske, & Yzerbyt, 2000; Overbeck & Park, 2001; A. M. Russell & Fiske, 2010). In an attempt to reconcile these seemingly contradictory findings, attention has recently focused on the situated and multi-faceted nature of interpersonal power (Overbeck, 2010) and on the meanings of power called out by the situation (Lammers, Stoker, & Stapel, 2009). Power allows individuals to attain desired outcomes more easily, and because these desired outcomes might vary with the situation, power-holders can flexibly muster cognitive resources for meeting situated needs (Guinote, 2007a, 2007b, 2010). In addition, different meanings of power called out by the situation (e.g., personal vs. relational power, Lammers et al., 2009; Overbeck, 2010; Van Dijke & Poppe, 2006) can also affect the likelihood of judging others based on stereotypes. Thus, recent research suggests that the effect of power on stereotyping versus individuating depends on the conceptualization of power that is triggered by the situation (Lammers et al., 2009; Overbeck & Park, 2001).

Building upon these recent developments, we focus on the role of cultural factors as key moderators of the effects of power on stereotyping and individuating mindsets. Power is instrumental for achieving culturally nurtured goals (B. Russell, 1938). Because those goals differ by cultural values, views of power as a tool for achieving culturally specific goals should differ as well. Indeed, recent research shows that the meanings and goals associated with power are culturally patterned (Torelli & Shavitt, 2010). It stands to reason that cognitive processes, or mindsets, that may be instrumental for culturally nurtured power goals should be culturally patterned as well. To the extent that people are routinely exposed to culturally meaningful power situations in which those mindsets are instrumental, they may be easily primed and applied to the task at hand (Oyserman, Sorensen, Reber, & Chen, 2009).

Two studies examine the cognitive processes triggered by distinct interpersonal power concepts when interpreting information about objects (e.g., brands). By examining for the first time the effects of power on information processing for nonsocial targets, we establish the role of processing mindsets in these effects. Our studies show that, when power is salient, one’s cultural orientation determines which cognitive mindsets – stereotyping or individuating – guide information processing.

Information Processing Triggered by Power

How does power influence information processing? Research has established that people with power often engage in an inward-focused processing style characterized by attention to the self’s internal attitudes and desires, with little consideration for the views and needs of others. For instance, Briñol, Petty, Valle, and colleagues (Brinol et al., 2007) show that priming power (by providing control over the evaluation of a subordinate in a role-playing task) prior to processing a message about a topic enhances the tendency to try to validate one’s initial views on the topic, which results in reduced information processing. Similarly, Rucker and Galinsky (2009) find that recalling an event in which one had power over others (vs. one in which others had power over oneself), creates an internal focus in processing product information. This produces an emphasis on the utility that a product offers the self. High-power participants are also less likely to incorporate others’ perspectives into their judgments, and are less focused on the emotions and views of others than participants who are not primed with power (Galinsky et al., 2006). Fiske and colleagues (Fiske, 1993, 2001; Goodwin et al., 2000) further demonstrate the inward focus of powerful individuals who use their own stereotypes when evaluating less-powerful others. When feeling powerful, people attend more to information congruent with their prior expectations about others (i.e., category-based information), and attend less to incongruent information (i.e., category-inconsistent information). These cognitive processes, or mindsets, foster the maintenance of stereotypes about others. Fiske (1993) argued that confirming prior expectations about less-powerful others facilitates defending one’s powerful status by reasserting control.

Although the evidence that power triggers such self-centered or stereotyping processes is robust and clear-cut, another set of evidence has recently emerged showing that power-holders sometimes invest effort in individuating and understanding others (Goodwin et al., 2000; Lammers et al., 2009; Overbeck & Park, 2001; A. M. Russell & Fiske, 2010). Increased responsiveness to situational demands may be responsible for the more individuated perceptions of power-holders uncovered in this research (Guinote, 2007a, 2007b, 2010). Thus, although power-holders might stereotype others by default (i.e., when stereotypes are readily available), they can also readily muster cognitive processes that individuate others when the situation calls for a more accurate perception of these others (Guinote, 2010; Overbeck & Park, 2001). For instance, power-holders who have been induced to feel responsible for others evaluate less-powerful others by attending carefully to information that is incongruent with their prior expectations about the target (i.e., individuating processes, Goodwin et al., 2000), presumably because such cognitive processes facilitate forming an accurate impression instrumental for helping the other person. Similarly, Overbeck and Park (2001) report that power-holders (vs. powerless individuals) in an other-centered interaction remember better the characteristics and actions of individual targets (i.e., individuation), presumably because the other-centered nature of the task induces power-holders to feel a sense of responsibility toward the target.

The way one conceptualizes power can also affect the extent to which power leads to stereotyping of others. Lammers, Stoker and Stapel (2009) showed that, in the presence of ambiguous information about a person or when no information is presented, power interpreted as the ability to get what one wants independently of others (i.e., one’s own agentic capacity, Overbeck, 2010) increases the likelihood of stereotyping people. In contrast, power interpreted as responsibility over others reduces stereotyping (Lammers et al., 2009). It is understandable that power-holders who hold an agentic, nonrelational concept of power will stereotype because there is little reason to put effort into processing information about others. However, this does not mean that every type of relational power will reduce stereotyping. As reviewed earlier, having power over others can induce inwardly focused processes associated with increased stereotyping (e.g., Brinol et al., 2007; Galinsky et al., 2006; Gruenfeld et al., 2008; Rucker & Galinsky, 2009).

We propose that different conceptualizations of relational power called out by the situation can determine whether stereotyping is more or less likely to occur. Specifically, because power concepts and goals are culturally patterned (Torelli & Shavitt, 2010), it stands to reason that information processing mindsets triggered by power should be culturally patterned as well. We turn to this issue next.

Culture and Processing Mindsets

Some cultural values foster a view of interpersonal power as something to be used for advancing one’s personal agenda, obtaining praise and admiration from others, and hence maintaining and promoting one’s powerful status in the eyes of others – this is a personalized power concept. Other cultural values foster a view of power as something to be used for helping and benefitting others – this is a socialized power concept (McClelland, 1973; Winter, 1973).

Vertical (V) and horizontal (H) cultural orientations have been linked to these distinct power concepts. V/H forms of individualism and collectivism were originally delineated by Triandis and colleagues (Singelis, Triandis, Bhawuk, & Gelfand, 1995; Triandis, 1995; Triandis, Chen, & Chan, 1998; Triandis & Gelfand, 1998) to describe the nature and importance of hierarchy in interpersonal relations. Vertical individualism (VI) is associated with concerns about achieving status in individual competitions with others (as captured by scale items such as, "winning is everything," Singelis et al., 1995; Triandis & Gelfand, 1998), and people high in VI (versus HI) orientation give more importance to displays of success and status (Nelson & Shavitt, 2002). Thus, Torelli and Shavitt (2010) have demonstrated that vertical (and not horizontal) individualism is associated with a personalized concept of power. In contrast, people high in horizontal collectivism (HC) emphasize nurturing and interdependent relationships with others (as captured by scale items such as "I feel good when I cooperate with others," Singelis et al., 1995; Triandis & Gelfand, 1998). They endorse benevolence values and reject power values of control or dominance over people and resources (Oishi, Schimmack, Diener, & Suh, 1998). This emphasis on cooperating with and helping others, as opposed to being submissive toward or wanting to dominate others, is characteristic of individuals with a socialized power concept (Frieze & Boneva, 2001; McClelland, 1973). Indeed, horizontal (and not vertical) collectivism is associated with a socialized power concept (Shavitt, Torelli, & Wong, 2009; Torelli & Shavitt, 2010).

The links between a VI orientation and personalized power, and an HC orientation and socialized power, have been observed across samples of participants from several national cultures and ethnic groups (Torelli & Shavitt, 2010). These power concepts were reflected in a number of explicit and implicit responses. For instance, people high vs. low in VI (HC) orientation recalled more vividly those experiences in which they had the power to impress (help) others, exhibited behavioral intentions to pursue personalized (socialized) power objectives, and showed higher tendencies to use power in an exploitative (benevolent) way.

Because culturally nurtured concepts of power affect the goals that are likely to be triggered by power (i.e., goals of enhancing status versus helping others), cognitive processes that are instrumental to these goals should also be culturally patterned. We propose that the stereotyping mindset shown in past research to be exhibited by the powerful (e.g., Fiske, 1993, 2001) is more relevant for people high (versus low) in VI. Such a stereotyping mindset is instrumental for defending one’s powerful status by reasserting control (Fiske, 1993). Because high-VI (versus low-VI) people are more likely to view power in such terms, contexts that make personalized power salient should more readily elicit stereotyping processes. Specifically, for high-VI (vs. low-VI) individuals, priming personalized power should result in more attention to information that is consistent with their stereotypes, and less attention to information that is inconsistent with these stereotypes.

However, a stereotyping mindset is not instrumental for benefitting and helping others. People high in HC, who tend to have a socialized power concept, may therefore not be predisposed to stereotype when this type of power is salient. Power-holders who focus on the needs of others are more inclined to attend to individuating information (Overbeck & Park, 2001; A. M. Russell & Fiske, 2010). As described earlier, power-holders who have been induced to feel responsible for others evaluate less-powerful others by attending carefully to information that is incongruent with their prior expectations about the target (i.e., individuating processes, Goodwin et al., 2000), presumably because such cognitive processes facilitate forming an accurate impression instrumental for helping the other person. Thus, we predict that for high-HC (vs. low-HC) individuals, priming socialized power should result in more attention to information that is incongruent with their stereotypes about a target.

The Routinizing of Cultural Mindsets

Because cultural factors influence the types of situations to which people are routinely exposed, cultural mindsets emerge as successful ways to address these routine situations. These cultural mindsets become chronically accessible and can be easily primed and used for the task at hand (Oyserman et al., 2009). For people high in VI (HC) orientation, frequent and consistent experience using stereotyping (individuating) processes in response to personalized (socialized) power situations should lead these processes to become routinized and readily triggered by environmental stimuli (Bargh, 1984; Bargh, Bond, Lombardi, & Tota, 1986). As a result, we argue that the salience of power can trigger culturally patterned processing mindsets. Furthermore, these mindsets should be activated even when processing information that is not directly relevant to power goals. Thus, although past research on power has studied processing styles in the context of perceptions about social targets (e.g., subordinates or low-power others, Fiske, 1993, 2001; Goodwin et al., 2000), we examined information processing about non-social targets; specifically, products and brands.

This extension to non-social targets both broadens the substantive implications of our findings and helps to establish the processes responsible for them. Prior research has shown that stereotyped processing decreases when power-holders feel responsibility toward others (Goodwin et al., 2000; Lammers et al., 2009; Overbeck & Park, 2001). However, it is difficult to rule out the role of impression management in such results. Presumably, stereotyping of other persons is socially undesirable, and interdependent, other-focused thinking is known to activate impression motivation (e.g., Lalwani & Shavitt, 2009). Showing that similar patterns emerge when processing information for brands increases confidence that the hypothesized effects emerge from mindset activation and not from a desire to create a good impression.

Two experiments provided evidence that making personalized power salient triggers a stereotyping mindset among vertical individualists. That is, they recognize better product information that is congruent (vs. incongruent) with their prior expectations. In contrast, making socialized power salient triggers an individuating mindset among horizontal collectivists, improving their memory for incongruent product information. Existing evidence linking VI and HC to power concepts comes from participants from numerous cultural groups (Torelli & Shavitt, 2010). Thus, the present focus was on how cultural orientation in U.S. participants moderates the information-processing mindsets triggered by power (see Chiu & Hong, 2006; Lalwani, Shavitt, & Johnson, 2006; Lalwani, Shrum, & Chiu, 2009, for a similar approach).

Experiment 1

Experiment 1 used two samples to assess stereotyping and individuating processing as a function of cultural orientation and power prime (personalized vs. socialized). In sample 1, we used fictitious products as stimuli and a recognition task as the dependent variable. In sample 2, we used a real brand as the stimulus and a free recall task as the dependent variable.

Method

Participants and Procedure – Sample 1

We primed 257 student participants (60% Caucasians, 27% Asians or Asian Americans and 7% Hispanics, with an average age of 20.7 years) with either personalized or socialized power concepts by randomly assigning them to read initial information about one of two products. In one condition (personalized power), participants read about an investment advisory product (“Interbank”) described in terms of three status-enhancing features intended to prime personalized power (e.g., “a member of the most powerful financial group”). In the other condition (socialized power), participants read about a dog food (“Doggy One”) described in terms of three nurturing features intended to prime socialized power (e.g., “Doggy One ® dog food has been designed for a tasty treat that is sure to make your dog’s face light up with excitement”)2. Next, participants were presented with two additional pieces of information that were congruent with the initial description of the product (e.g., “financial experts graduated from the top-tier universities in the country,” or “carefully designed by pet lovers like you who know how much you care for the well being of your dog”) and two that were incongruent (e.g., “financial specialists would call customers on their birthdays,” or “the [pet food] company influences distributors to stop carrying competitors’ products”)3. Participants then answered some general questions regarding what they thought about the product. After a 20-min filler task, they were presented with a surprise recognition task for the additional congruent and incongruent product information and indicated on a 9-point scale the degree to which they remembered seeing each piece of information (1 = “I am sure I did not see this information,” 9 = “I definitely remember seeing this information”). Finally, participants completed Triandis and Gelfand’s (1998) scale for measuring VI and HC,4 answered demographic questions, and were debriefed and dismissed.

Participants and Procedure – Sample 2

A second sample partially replicated the first one, examining only the effect of priming socialized power on individuated processing. We primed 97 student participants (88% Caucasians, 7% Asians or Asian Americans and 4% Hispanics, with an average age of 20.9 years) with socialized power by having them read a story containing socialized power themes (see Winter, 1973, for a similar procedure) prior to presenting information about a real brand (BMW). The story concerned the socially responsible activities of Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie, chosen because participants were very familiar with their prosocial work5. After writing down their thoughts about the story, participants were presented with an unrelated study about product opinions that included information about BMW in the form of “users’ opinions and comments from car enthusiasts.” Participants were asked to read the information in order to answer some questions. The information was presented in a table and included five items congruent with BMW’s luxurious and high-status image (e.g., “My new BMW is a lot better than my Porsche. I can see why my neighbor also wants to get one”), and two items incongruent with BMW’s image (e.g., “As a co-sponsor of the recent National Conference of Charities held in Chicago, BMW strengthened its view of a world with more social justice and equality”)6. After answering some general questions about BMW (e.g., familiarity and brand perceptions) and completing filler tasks for 20 min., participants were presented with a surprise recall task in which they were asked to list three things they remembered reading about BMW. Finally, participants completed the same cultural orientation scale used in sample 1, answered demographic questions, and were debriefed and dismissed.

Results

Stereotyping and Individuating Indices - Sample 1

In line with past research, stereotyping and individuating were assessed using a recognition task for both the congruent and the incongruent information (see Cohen, 1981; Overbeck & Park, 2001). For each participant, we first computed separate mean recognition scores for the two congruent and the two incongruent information items. A stereotyping index was computed by dividing the average congruent recognition score by the sum of the score for congruent plus incongruent information (see Overbeck & Park, 2001, for a similar procedure). An individuating index was computed by averaging the recognition scores for the two incongruent pieces of information (see Goodwin et al., 2000; Overbeck & Park, 2001). Note that we did not measure individuation as the lack of stereotyping or vice versa, as stereotyping and individuating are not considered as mutually exclusive processes (see Oakes, Haslam, & Turner, 1994, for a discussion; see also Overbeck & Park, 2001).

Predictors of the stereotyping index

We computed a regression equation with the arcsine transformed stereotyping index as dependent variable and a dummy variable for the type of power prime (0 = personalized power, 1 = socialized power), the means of the VI and HC subscales (mean-centered, α = .75 and .70, respectively), and the interactions between the type of power prime and the means of the VI and HC subscales as predictors. Results yielded a significant coefficient for the type of power prime, β = -.28, t(250) = −4.63, p < .001, explained by the higher stereotyping index in the personalized power condition (M = .59) compared to the socialized power condition (M = .52). More importantly, the coefficient of the mean VI orientation was also significant, β = .28, t(250) = 3.61, p < .001, and that of the VI × type of power prime interaction was marginally significant, β = -.13, t(250) = −1.64, p = .10. No other coefficients reached significance (p’s > .6). To further interpret the latter effects, we conducted a simple slope analysis (Preacher, Curran, & Bauer, 2006). Consistent with our predictions, high- VI (vs. low-VI) participants primed with personalized power engaged in more stereotyping about the products, M = .63 and .56 respectively, t(250) = 3.61, p < .001 (see figure 1). In contrast, for those primed with socialized power, there were no differences in stereotyping between high-VI and low-VI participants M = .53 and .51 respectively, p > .4. As expected, there were also no differences in stereotyping between participants high (vs. low) in HC in both priming conditions (p > .4).

Figure 1.

Stereotyping Index as a Function of Power Prime and VI- or HC-Score (Centered) – Experiment 1 (Sample 1)

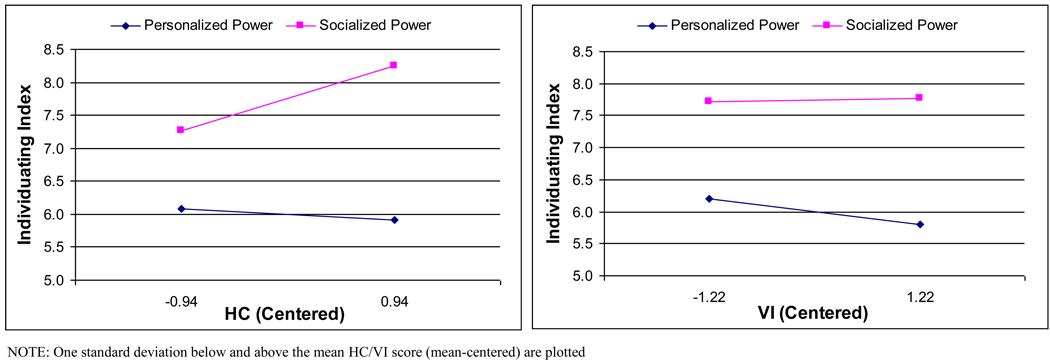

Predictors of the individuating index

A regression equation with the individuating index as dependent variable and the same predictors used in the previous analysis yielded a significant coefficient for the type of power prime, β = .43, t(250) = 7.49, p < .001, explained by the higher individuating index in the socialized power condition (M = 7.67) compared to the personalized power condition (M = 6.00). More importantly, the coefficient of the HC × power prime interaction was also significant, β = .19, t(250) = 2.43, p < .025. No other coefficients reached significance (p’s > .2). As predicted (see figure 2), high-HC (vs. low-HC) participants primed with socialized power individuated more, M = 8.23 and 7.26 respectively, t(250) = 2.87, 15 p < .005. In contrast, for those primed with personalized power, there were no differences in individuating between high-HC and low-HC participants, M = 5.92 and 6.07 respectively, p > .6. This was also the case for participants high (vs. low) in VI in both conditions (p > .2).

Figure 2.

Individuating Index as a Function of Power Prime And HC- or VI-Score (Centered) – Experiment 1 (Sample 1)

Individuating Index – Sample 2

The three things about BMW that participants recalled were coded by two raters as to whether they referred to the incongruent information given. The total number of incongruent items recalled was used as a measure of individuating. A regression equation with this individuating index as the dependent variable and the means of the VI and HC subscales (mean-centered, α = .72 and .70, respectively), and the level of familiarity with BMW as predictors, yielded a significant coefficient for HC, β = .24, t(93) = 2.37, p < .025. No other coefficients were significant (p’s > .7). As predicted, high (vs. low) in HC participants primed with socialized power individuated more – that is, they had better recall for information incongruent with BMW’s image.

Discussion

Results from this experiment suggest that cultural factors moderate how power impacts information processing. When the power concept associated with a given cultural orientation was made salient, it triggered distinct cognitive processes. When personalized power was salient, vertical individualism predicted greater stereotyping. That is, vertical individualists recognized better the information congruent with their initial description of the status product, relative to their recognition of incongruent information. In contrast, when socialized power was salient, horizontal collectivism predicted more individuated processing, as evidenced by better recognition of information incongruent with the initial description of the nurturing product.

Sample 2 generalized the effects of the socialized power prime on individuated processing across product types (i.e., the nurturing dog food as well as the status-oriented BMW brand) and across memory measures (recognition as well as free recall). When socialized power was salient, horizontal collectivism predicted more individuated processing, as reflected by better recall of information incongruent with BMW’s image. Moreover, the use of a familiar product in sample 2 supported the notion that priming socialized power enhanced horizontal collectivists’ recall of information that mismatched their prior beliefs or stereotypes about the brand.

Although the findings in both samples of experiment 1 support our hypotheses, one limitation is that the information content that people read was itself relevant to personalized or socialized power goals (describing the brand’s status or prosocial attributes). However, our hypotheses imply the automatic activation of mindsets that serve these power goals and should extend to any stereotype congruent or incongruent information. Therefore, experiment 2 was designed to generalize the findings to the processing of information unrelated to status or prosocial attributes. To further extend generalizability, the study employed new ways of activating personalized and socialized power concepts, using word-completion primes. In addition, we added a control condition in which power was not primed. This allowed us to isolate the separate effects of personalized and socialized power primes on information processing by contrasting against a no-prime condition.

Experiment 2

Method

Participants and Procedure

One-hundred and thirty-six undergraduate students (73% Caucasians, 20% Asians or Asian Americans and 2% Hispanics, with an average age of 20.8 years) were randomly assigned to one of three power prime conditions: personalized, socialized, or no prime (control). Power was primed using a 16-item word-fragment completion task (see Bargh, Raymond, Pryor, & Strack, 1995), in which 6 of the items contained the critical power words. In the personalized power condition these words were “power, wealth, authority, ambitious, president, and boss” (in list positions 2, 4, 7, 11, 13, and 14). In the socialized power condition the words were “power, helpful, responsible, caring, sympathetic, and loyal” (in the same list positions)7. The remaining 10 items were neutral words (“pencil”) as were all the words in the control condition. After completing this task, participants read information regarding a well-established brand, McDonald’s Restaurants. The information included opinions about McDonald’s restaurants ostensibly “collected from participants from previous experimental sessions.” The information was unrelated to personalized or socialized power (see footnote 1 for pretest information), and each piece of information included an attribute and a related comment about McDonald’s. The information was presented in a table and included five attributes/comments congruent with the McDonald’s stereotype of unhealthiness and convenience (“convenience, greasy, unhealthy, flavorful, and fast”) and three incongruent attributes/comments (“healthy, cozy, and delicate,” from a pretest—see footnote 1). After writing their thoughts about the information they just read and completing other tasks for 20 min., including writing a short review of McDonald’s, participants received a surprise recognition task for the attributes and comments and indicated, on the same 9-point scale used in experiment 1, the degree to which they remembered seeing each of them. Finally, participants completed the cultural orientation scale used in experiment 1, answered demographic questions, and were debriefed and dismissed.

Results

Stereotyping and Individuating Indices

The study employed the same stereotyping and individuating indices from the recognition task in experiment 1 (sample 1). We averaged the recognition of incongruent attributes with that of incongruent comments, as well as the recognition of congruent attributes and comments, before computing the indices.

Predictors of the Stereotyping Index

A regression equation with the arcsine transformed stereotyping index as dependent variable and dummy variables for the personalized (0 = otherwise, 1 = personalized) and socialized (0 = otherwise, 1 = socialized) power prime conditions, means of the VI and HC subscales (mean-centered, α = .79 and .72, respectively) and interactions between the power prime dummy variables and means of the VI and HC subscales as predictors (a total of 8 predictors) yielded a significant coefficient for the VI × personalized power interaction, β = .27, t(128) = 2.19, p < .05. No other coefficients were significant (p’s ≥ .10). As predicted, a simple slope analysis indicated that when primed with personalized power, high-VI (vs. low-VI) participants stereotyped more, M = .62 and .55 respectively, t(138) = 2.71, p < .01 (see figure 3). That is, personalized power salience increased their relative recognition for attributes congruent with the McDonald’s stereotype. In contrast, as expected, there were no differences in stereotyping between participants high and low in VI in the control (M = .55 and .56 respectively, p > .7) and socialized power conditions (M = .58 and .57, p > .5). This was also the case for participants high vs. low in HC in all conditions (p > .4).

Figure 3.

Stereotyping Index as a Function of Power Prime and VI- or HC-Score (Centered) – Experiment 2

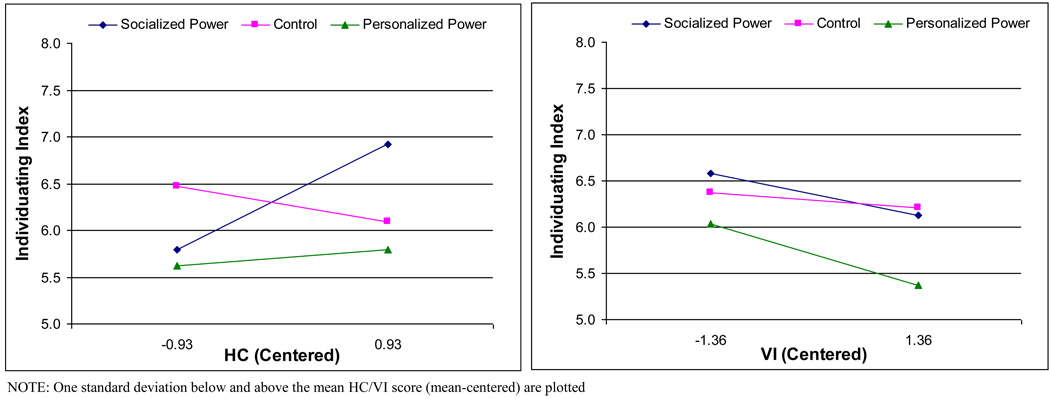

Predictors of the Individuating Index

A regression equation with the individuating index as dependent variable and the same predictors used in the previous analysis yielded a significant coefficient for the HC X socialized power interaction, β = .31, t(128) = 2.16, p < .05. No other coefficients were significant (p’s ≥ .10). As expected, when primed with socialized power, high- (vs. low-) HC participants recognized better the information incongruent with the McDonald’s stereotype, M = 6.92 and 5.79 respectively, t(128) = 2.67, p < .01 (see figure 4). That is, socialized power salience increased their individuated processing of the McDonald’s brand. In contrast, as expected, there were no differences in individuating between high- and low-HC participants in the control (M = 6.09 and 6.47 respectively, p > .5) and personalized power conditions (M = 5.80 and 5.62 respectively, p > .7). This was also the case for participants high (vs. low) in VI in all conditions (p > .2).

Figure 4.

Individuating Index as a Function of Power Prime And HC- or VI-Score (Centered) – Experiment 2

Discussion

Overall, these findings provide additional evidence for the cultural patterning of information processing triggered by power. Participants high (vs. low) in a VI orientation primed with personalized power stereotyped more. That is, they recognized better the information congruent with the McDonald’s stereotype of unhealthiness and convenience relative to their recognition of the incongruent information. In contrast, participants high (vs. low) in HC orientation primed with socialized power individuated more. That is, they were more likely to recognize information incongruent with the McDonald’s stereotype.

Experiment 2 allowed us to compare the stereotyping (individuating) tendencies of high-VI (-HC) participants primed with personalized (socialized) power against a control group not primed with power. For high-VI participants, those primed with personalized power stereotyped more than did those in the control condition (t(128) = 3.47, p < .001). In contrast, for low-VI participants, as expected, there was no difference in stereotyping between the personalized power and control conditions (t < .4, ns). Individuating was also contingent on the interplay between cultural value orientation and power prime. For high-HC participants, those primed with socialized power individuated more than did those in the control condition (t(128) = 1.89, p = .06). In contrast, low-HC participants, as expected, did not individuate more in the socialized power versus control conditions (t < 1.4, ns).

General Discussion

Interpersonal power is a pervasive and important psychological state. The present studies suggest that the way in which power impacts information processing depends on cultural factors. For those with a vertical individualistic cultural orientation, characterized by concerns about achieving status and recognition from others through competition, priming personalized power increases the tendency to stereotype in processing product information. Thus, they exhibit better recognition of information congruent with their prior product expectations, relative to their recognition of incongruent information. This is presumably because a stereotyping mindset is instrumental for defending one’s powerful status over others by asserting control (Fiske, 1993), a goal that would be important to high-VI people who tend to view power in such personalized terms (Torelli & Shavitt, 2010). In contrast, for those with a horizontal collectivistic cultural orientation, characterized by an emphasis on sociable and benevolent relations with others, priming socialized power increases the tendency to individuate. Thus, they exhibit better recognition and recall of product information that is incongruent with expectations. This is presumably because an individuating mindset enables the formation of accurate impressions of others that are instrumental for meeting their needs (Goodwin et al., 2000; Lammers et al., 2009; A. M. Russell & Fiske, 2010), a goal that would be important to high-HC people who tend to view power in such socialized terms.

These effects were shown using different power primes and a variety of dependent variables to capture their effects. They emerged across a diverse set of products (e.g., financial services, dog food, cars and restaurants), and a variety of brands, including well-known brands (McDonald’s, BMW) and fictitious ones, thus attesting to the generalizability of these effects.

Results here extend past findings on the effects of power on information processing in a number of ways. First, building upon the notion that power is situated and multi-faceted (Guinote, 2007a, 2007b, 2010; Lammers et al., 2009; Van Dijke & Poppe, 2006), we show for the first time cultural patterns in the cognitive processes triggered by interpersonal power. Such effects on general judgment processes are important to examine (Wyer et al., 1991). The results suggest that the stereotyping tendencies of power-holders frequently reported in past research (Fiske, 1993, 2001; Goodwin et al., 1998) will be observed among people with a vertical individualistic cultural orientation, but may not emerge for others. Moreover, previous findings regarding the individuating processing tendencies of power-holders induced to feel responsible for others (e.g., Goodwin et al., 2000) would be likely to emerge for people who have a horizontal collectivistic cultural orientation, but may not emerge for others.

Second, we show that the impact of culturally nurtured power concepts on information processing extends to non-social targets. Previous research on power and information processing has studied the processing of information about persons and groups, including those relevant to one’s power goals. This makes it difficult to rule out the role of impression management on some of the reported effects. Presumably, stereotyping of other persons is socially undesirable (Dovidio & Gaertner, 1991), and interdependent, other-focused thinking is known to activate a desire to create a good impression (Lalwani & Shavitt, 2009). Thus, past research documenting less person stereotyping when power is interpreted as responsibility over other people (e.g., Lammers et al., 2009), or more individuating in other-centered situations (e.g., Overbeck & Park, 2001), could be due to a desire to avoid presenting the self as being prejudiced (Breckler & Greenwald, 1986). We show for the first time that stereotyping and individuating are also activated as mindsets applied to products and brands, where social desirability concerns presumably are not relevant. We propose that the frequent experience activating stereotyping or individuating processes in response to culturally meaningful personalized or socialized power situations gives rise to the routinizing of these processes, making them readily triggered by congruent power cues (Bargh, 1984; Bargh et al., 1986; Oyserman et al., 2009). Thus, for instance, priming socialized power elicited individuated processing of brand and product information even though this information was not directly relevant to power goals of helping others.

Third, we revisit past findings about the stereotyping tendencies of power-holders and show that these tendencies are moderated by people’s cultural orientation. We show for the first time that people high (vs. low) in vertical individualism stereotype more upon being primed with an interpersonal concept of power (power as gaining status and recognition from others – i.e., personalized power). Personalized power was primed via processing of status-enhancement cues in products (experiment 1) and of interpersonal-power words associated with status (e.g., wealth, ambitious, authority, president, boss –experiment 2– which predominantly represent interpersonal-power stimuli, see Lammers et al., 2009). Thus, extending past findings showing that power is associated with stereotyping tendencies when power is defined as independence from others (i.e., a notion of power as agentic capacity, Lammers et al., 2009), our results show that these stereotyping tendencies also can be triggered as a function of the salience of interpersonal power (gaining status over others).

Finally, our results for cultural orientation are in line with a growing body of work highlighting the situation-specificity of power effects (Guinote, 2008, 2010; Slabu & Guinote, 2010). We show that people’s culturally nurtured conceptualizations of power determine which power-related situations trigger a given processing mindset. High-VI (vs. low-VI) individuals with a personalized view of power stereotype more when the situation makes salient personalized power affordances, whereas these effects are absent among individuals high (vs. low) in HC as well as in situations that make salient socialized power affordances. In contrast, High-HC (vs. low-HC) individuals with a socialized view of power individuate more when the situation makes salient socialized power affordances, whereas these effects are absent among individuals high (vs. low) in VI as well as in situations that make salient personalized power affordances.

A few limitations of this research should be noted. Because we used familiar brands as targets (experiment 1 – sample 2 – and experiment 2), we presented participants with more stereotypical than non-stereotypical “consumer opinions,” as this reflects what one would expect emerging from a real sample of consumers. Although this allowed us to study processing of brand information as it is likely to be encountered in reality, this procedure departed from past studies that present participants with a balanced set of congruent and incongruent items, generally about unfamiliar targets (e.g., a fictitious person). Because participants shown a familiar versus unfamiliar target presumably could more easily allocate their cognitive resources to the task at hand (Peracchio & Tybout, 1996), an unrealistic proportion of incongruent consumer opinions may appear suspicious and could lead to unintended negative inferences (Cacioppo & Petty, 1979; Meyers-Levy & Peracchio, 1995). Presenting more stereotypical than non-stereotypical consumer opinions minimizes this possibility. However, it does not enable us to rule out the possibility that increased recall of the incongruent information is actually due to its infrequency. Still, we believe this is not a plausible interpretation of our findings because it cannot account for the results of experiment 1 (sample 1) in which participants were presented with a balanced number of congruent and incongruent pieces of information.

Another limitation of these studies is their reliance on measured cultural orientations from U.S. participants. Although we sampled participants from varied ethnic backgrounds, we did not find differences as a function of ethnicity (e.g., between East Asians or Hispanics and Anglo Whites) in any of the information processing measures or in VI and HC scores. This is consistent with some previous findings (Benet-Martinez & Karakitapoglu-Aygun, 2003; see Oyserman, Coon, & Kemmelmeier, 2002 for a review) and may be attributed to the fact that East Asian and Hispanic participants completed the questionnaires in English (Trafimow, Silverman, Fan, & Law, 1997) as well as to the small sample size of non-White participants (27% across studies). Providing convergence for the role of culture via comparisons across varied cultural groups would be desirable. Indeed, recent research (Torelli & Shavitt, 2010) has shown that members of ethnic and national groups that tend to be high in VI (e.g., European-Americans, Canadians) tend to view power in personalized terms, whereas members of ethnic and national groups that tend to be high in HC (e.g., Hispanic-Americans, Brazilians), tend to view power in socialized terms. Therefore, there is reason to expect that the stereotyping mindsets we observed in the present studies would be especially likely to emerge for European-American or North American participants primed with personalized power. Moreover, one would expect that the individuating mindsets observed here would be especially likely to emerge for Hispanic or Latin- American participants primed with socialized power.

Indeed, previous findings with U.S. participants, who tend to have a VI orientation (Triandis & Gelfand, 1998), have shown that power-holders primed with concepts consistent with personalized power tend to process information in a way that confirms their prior expectations (Fiske, 1993, 2001; Goodwin et al., 1998). The present results suggest the possibility that these findings may be limited to individuals or cultural groups with a VI orientation. Future research could examine whether, for instance, Hispanic or Latin-American participants would show these effects.

Our findings also contribute to the recent view of culture as situated cognition (Oyserman et al., 2009) by uncovering the cultural patterning of processing mindsets likely to be triggered by power. Among individuals high in VI orientation, stereotyping mindsets are easily triggered by situations that call out a personalized view of power. In contrast, these individuals do not seem to activate an individuating mindset with the same ease when primed with socialized power. To the extent that a personalized, and not a socialized, view of power is widely shared in a vertical individualist society (such as those in the U.S. and Great Britain, Triandis & Gelfand, 1998), one would expect a general tendency to use stereotyping processes in situations that make personalized power salient. Indeed, being seen engaging in stereotyping could further reinforce one’s powerful position in the eyes of others (Magee, 2009). In contrast, for individuals in vertical individualist societies, individuation should be a more situated effect. This seems to fit the findings in this and past research relying primarily on North American or British samples (e.g., Guinote, 2010).

However, our findings suggest that differences in the nature of culturally nurtured power concepts further moderate these effects. Individuals high in HC orientation do not easily activate a stereotyping mindset upon being primed with personalized power. Instead, these individuals can easily individuate when facing psychologically meaningful situations in which socialized power is salient. To the extent that a socialized, and not a personalized, view of power is widely shared in a society, one might expect a general tendency to individuate in situations that make socialized power salient. In these cultural contexts, stereotyping might be a more situated effect. This suggests that processing mindsets that are tuned to culturally patterned views of power may not be as flexible as mindsets tuned to other cultural syndromes, such as individualism and collectivism (e.g., separating and connecting mindsets, Oyserman et al., 2009). Future research could address further the malleability of culturally patterned processing mindsets linked to power.

Acknowledgements

This article is based in part on a doctoral dissertation completed by Carlos J. Torelli under the direction of Sharon Shavitt and submitted to the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Portions of this research were presented at the 2007 North American Conference of the Association for Consumer Research. This research was supported by grants to Carlos J. Torelli from the Irwin Foundation, the FMC Technologies Inc. Educational Fund (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign), the Sheth Foundation, and the Carlson School of Management (University of Minnesota). Preparation of this article was also supported by Grant 1R01HD053636-01A1 from the National Institutes of Health and Grant 0648539 from the National Science Foundation to Sharon Shavitt and Grant 63842 from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to Sharon Shavitt and Carlos J. Torelli. We are grateful to Patrick Vargas, Madhu Viswanathan, and Tiffany White for their valuable comments.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Unless otherwise noted, we use the terms power and interpersonal (or relational) power interchangeably to refer to the inherently relational nature of social power (Guinote & Vescio, 2010). This should be distinguished from a non-relational form of power that reflects one’s own agentic capacity to act independently of others, sometimes referred to as personal power (Lammers et al., 2009; Overbeck, 2010). Rather than adopt this personal/social terminology, we focus on the previously established distinction between socialized power (power for helping and benefitting others) and personalized power (power for obtaining status and admiration from others) (McClelland, 1973; Torelli & Shavitt, 2010; Winter, 1973), both of which are inherently relational.

This priming technique is based on the notion that objects, brands and commercial messages can activate their associated abstract concepts and goals (Chartrand, Huber, Shiv, & Tanner, 2008; Fitzsimons et al., 2008; Rucker et al., 2010; Shavitt, 1990, 1992). We assessed the validity of this assumption in a separate pretest (N = 43). Upon reading each product description participants rated, on 7-point scales, their feelings of personalized power (“promoting one's powerful status in the eyes of others”, “gaining status over others”), socialized power (“caring for the well being of others”, “helping others”), and non-relational power (“being independent from others”, “freedom”). The personalized power message was successful at distinctively activating personalized power (MPersonalized Power = 5.40, significantly greater than MSocialized Power = 3.64 and MAgentic Capacity = 3.74, p’s < .001), whereas the socialized power message distinctively primed socialized power (MSocialized Power = 5.29, significantly greater than MPersonalized Power = 2.37 and MAgentic Capacity = 2.65, p’s < .001).

The congruent/incongruent nature of the additional information in this and subsequent experiments was assessed in three separate pretests (N1 = 56, N2 = 50 and N3 = 113) with participants who did not take part in the main studies. These participants rated each piece of information, on a 7-point scale, for how congruent/incongruent it was with the impression they had from reading the initial description of the products, or from their knowledge about the target brand. Participants perceived the congruent (relative to the incongruent) information to be more congruent with the initial description of the products, or with the target brand’s image, MCongruent = 4.70 – 6.10 and MIncongruent = 1.87 – 3.30, p’s < .001.

Our predictions were based on research on the distinctive power representations of high-VI and HC individuals (Torelli & Shavitt, 2010), but we also measured the other two cultural orientations identified by Triandis and Gelfand (1998), horizontal individualism and vertical collectivism. We assessed the structural properties of the full scale; it was sound across all studies. In each of the subsequent studies, we conducted analyses adding the non-theoretically relevant cultural value orientations to the models. Because as expected we did not find any effects of these cultural value orientations, and adding them to the models did not change any of the effects reported here, we do not discuss them further.

We assessed the validity of this manipulation in a separate pretest (N = 41) with participants who did not take part in the main study. Upon reading the Pitt-Jolie story, these participants rated, on 7-point scales, their feelings of personalized, socialized, and non-relational power on the same items used to assess the validity of the manipulation used in sample 1. The story distinctively primed socialized power (MSocialized Power = 6.42, significantly greater than MPersonalized Power = 4.26 and MAgentic Capacity = 4.01, p’s < .001).

Because we used familiar brands as targets and presented participants with brand information ostensibly based on consumer opinions, we showed the congruent and incongruent consumer opinions in a proportion that reflects what one would expect emerging from a real sample of consumers (i.e., more stereotypical than non-stereotypical comments) in an attempt to maintain the ecological validity of the stimuli. This departed from past studies that present participants with a balanced set of congruent and incongruent items about an unfamiliar target (i.e., a fictitious person). We elaborate further on the implications in the General Discussion.

These words emerged from a separate pretest (N = 191) in which similar participants rated these words, on a 7-point scale, as distinctively descriptive of a socialized (vs. a personalized) power concept (MSocialized = 6.37 and MPersonalized = 3.12, p < .001). In this pretest, participants also rated the words in the personalized power condition as distinctively descriptive of a personalized (vs. a socialized) power concept (MPersonalized = 6.29 and MSocialized = 3.80, p < .001).

References

- Bargh JA. Automatic and conscious processing of social information. In: Wyer RSJ, Srull TK, editors. Handbook of social cognition. Vol. 3. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1984. pp. 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Bargh JA, Bond RN, Lombardi WJ, Tota ME. The additive nature of chronic and temporary sources of construct accessibility. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1986;50(5):869–878. [Google Scholar]

- Bargh JA, Raymond P, Pryor JB, Strack F. Attractiveness of the underling: An automatic power … sex association and its consequences for sexual harassment and aggression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;68(5):768–781. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.68.5.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benet-Martinez V, Karakitapoglu-Aygun Z. The interplay of cultural syndromes and personality in predicting life satisfaction: Comparing Asian Americans and European Americans. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2003;34(1):38–60. [Google Scholar]

- Breckler SJ, Greenwald AG. Motivational facets of the self. In: Sorrentino RM, Higgins TE, editors. Handbook of motivation and cognition: Foundations of social behavior. New York: Guilford Press; 1986. (pp. x, 610) [Google Scholar]

- Brinol P, Petty RE, Valle C, Rucker DD, Becerra A. The effects of message recipients' power before and after persuasion: A self-validation analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;93(6):1040–1053. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.6.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Petty RE. Effects of message repetition and position on cognitive response, recall, and persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1979;37(1):97–109. [Google Scholar]

- Chartrand TL, Fitzsimons GM, Fitzsimons GJ. Automatic effects of anthropomorphized objects on behavior. Social Cognition. 2008;26(2):198–209. [Google Scholar]

- Chartrand TL, Huber J, Shiv B, Tanner RJ. Nonconscious Goals and Consumer Choice. Journal of Consumer Research. 2008;35(2):189–201. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu C-Y, Hong Y-Y. Social Psychology of Culture. New York: Psychology Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen CE. Person categories and social perception: Testing some boundaries of the processing effect of prior knowledge. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1981;40(3):441–452. [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio JF, Gaertner SL. Changes in the expression and assessment of racial prejudice. In: Knopke HJ, Norrell RJ, Rogers RW, editors. Opening doors: Perspectives on race relations in contemporary America. Alabama: The University of Alabama Press; 1991. (pp. xviii, 234) [Google Scholar]

- Fiske ST. Controlling other people: The impact of power on stereotyping. American Psychologist. 1993;48(6):621–628. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.6.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiske ST. Effects of power on bias: Power explains and maintains individual, group, and societal disparities. In: Lee-Chai AY, Bargh JA, editors. The use and abuse of power: Multiple perspectives on the causes of corruption. NY: Psychology Press; 2001. pp. 181–193. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzsimons GM, Chartrand TL, Fitzsimons GJ. Automatic Effects of Brand Exposure on Motivated Behavior: How Apple Makes You "Think Different". Journal of Consumer Research. 2008;35(1):21–35. [Google Scholar]

- Frieze IH, Boneva BS. Power motivation and motivation to help others. In: Lee-Chai AY, Bargh JA, editors. The use and abuse of power: Multiple perspectives on the causes of corruption. NY: Psychology Press; 2001. pp. 75–89. [Google Scholar]

- Galinsky AD, Magee JC, Inesi M, Gruenfeld DH. Power and Perspectives Not Taken. Psychological Science. 2006;17(12):1068–1074. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin SA, Gubin A, Fiske ST, Yzerbyt VY. Power can bias impression processes: Stereotyping subordinates by default and by design. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations. 2000;3(3):227–256. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin SA, Operario D, Fiske ST. Situational power and interpersonal dominance facilitate bias and inequality. Journal of Social Issues. 1998;54(4):677–698. [Google Scholar]

- Gruenfeld DH, Inesi M, Magee JC, Galinsky AD. Power and the objectification of social targets. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;95(1):111–127. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.95.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guinote A. Behaviour variability and the Situated Focus Theory of Power. European Review of Social Psychology. 2007a;18:256–295. [Google Scholar]

- Guinote A. Power affects basic cognition: Increased attentional inhibition and flexibility. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2007b;Vol.43(5):685–697. [Google Scholar]

- Guinote A. Power and affordances: When the situation has more power over powerful than powerless individuals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;95(2):237–252. doi: 10.1037/a0012518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guinote A. The situated focus theory of power. In: Guinote A, Vescio TK, editors. The social psychology of power. New York: Guilford Press; 2010. pp. 141–173. [Google Scholar]

- Guinote A, Vescio TK. Power in social psychology. In: Guinote A, Vescio TK, editors. The social psychology of power. New York: Guilford Press; 2010. pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Kipnis D. The powerholders. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Lalwani AK, Shavitt S. The "me" I claim to be: Cultural self-construal elicits self-presentational goal pursuit. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;97(1):88–102. doi: 10.1037/a0014100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalwani AK, Shavitt S, Johnson T. What is the relation between cultural orientation and socially desirable responding? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;90(1):165–178. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalwani AK, Shrum LJ, Chiu C-Y. Motivated Response styles: The role of cultural values, regulatory focus, and self-consciousness in socially desirable responding. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009 doi: 10.1037/a0014622. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammers J, Stoker JI, Stapel DA. Differentiating social and personal power: Opposite effects on stereotyping, but parallel effects on behavioral approach tendencies. Psychological Science. 2009;20(12):1543–1549. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magee JC. Seeing power in action: The roles of deliberation, implementation, and action in inferences of power. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2009;45(1):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- McClelland DC. The two faces of power. In: McClelland DC, Steele RS, editors. Human Motivation: A Book of Readings. Morristown, NJ: General Learning Press; 1973. pp. 300–316. [Google Scholar]

- Meyers-Levy J, Peracchio LA. Moderators of the impact of self-reference on persuasion. Journal of Consumer Research. 1995;22(4):408–423. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MR, Shavitt S. Horizontal and vertical individualism and achievement values: A multimethod examination of Denmark and the United States. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2002;33(5):439–458. [Google Scholar]

- Oakes PJ, Haslam S, Turner JC. Stereotyping and social reality. MA, US: Blackwell Publishing; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Oishi S, Schimmack U, Diener E, Suh EM. The measurement of values and individualism-collectivism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1998;24(11):1177–1189. [Google Scholar]

- Overbeck JR. Concepts and historical perspectives on power. In: Guinote A, Vescio TK, editors. The social psychology of power. New York: Guilford Press; 2010. pp. 19–45. [Google Scholar]

- Overbeck JR, Park B. When power does not corrupt: Superior individuation processes among powerful perceivers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;81(4):549–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman D, Coon HM, Kemmelmeier M. Rethinking individualism and collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128(1):3–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman D, Sorensen N, Reber R, Chen SX. Connecting and separating mindsets: Culture as situated cognition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;97(2):217–235. doi: 10.1037/a0015850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peracchio LA, Tybout AM. The moderating role of prior knowledge in schema-based product evaluation. Journal of Consumer Research. 1996;23(3):177–192. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interaction effects in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31:437–448. [Google Scholar]

- Rucker DD, Dubois D, Galinsky AD. Generous Paupers and Stingy Princes: Power Drives Consumer Spending on Self versus Others. Journal of Consumer Research. 2010 DOI: 10.1086/657162, Published online Oct 1, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rucker DD, Galinsky AD. Conspicuous consumption versus utilitarian ideals: How different levels of power shape consumer behavior. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2009;45(3):549–555. [Google Scholar]

- Russell AM, Fiske ST. Power and Social Perception. In: Guinote A, Vescio TK, editors. The Social Psychology of Power. New York: The Guilford Press; 2010. pp. 231–250. [Google Scholar]

- Russell B. Power: A new social analysis. London: Routledge Classics; 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Shavitt S. The role of attitude objects in attitude functions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1990;26(2):124–148. [Google Scholar]

- Shavitt S. Evidence for Predicting the Effectiveness of Value-Expressive Versus Utilitarian Appeals: A Reply to Johar and Sirgy. Journal of Advertising. 1992;21(2):47–51. [Google Scholar]

- Shavitt S, Torelli CJ, Wong J. Identity-based motivation: Constraints and opportunities in consumer research. Journal of Consumer Psychology. 2009 Mar;19:261–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jcps.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singelis TM, Triandis HC, Bhawuk D, Gelfand MJ. Horizontal and vertical dimensions of individualism and collectivism: A theoretical and measurement refinement. Cross-Cultural Research: The Journal of Comparative Social Science. 1995;29(3):240–275. [Google Scholar]

- Slabu L, Guinote A. Getting what you want: Power increases the accessibility of active goals. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2010;46(2):344–349. [Google Scholar]

- Torelli CJ, Shavitt S. Culture and Concepts of Power. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2010;99(4):703–723. doi: 10.1037/a0019973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trafimow D, Silverman ES, Fan RM-T, Law JSF. The effects of language and priming on the relative accessibility of the private self and the collective self. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1997;28(1):107–123. [Google Scholar]

- Triandis HC. Individualism & collectivism. CO: Westview Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Triandis HC, Chen XP, Chan DK. Scenarios for the measurement of collectivism and individualism. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1998;29(2):275–289. [Google Scholar]

- Triandis HC, Gelfand MJ. Converging measurement of horizontal and vertical individualism and collectivism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74(1):118–128. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijke M, Poppe M. Striving for personal power as a basis for social power dynamics. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2006;36(4):537–556. [Google Scholar]

- Winter DG. The Power Motive. New York, NY, US: Free Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Wyer RS, Budesheim TL, Shavitt S, Riggle ED, Melton R, Kuklinski JH. Image, issues, and ideology: The processing of information about political candidates. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61(4):533–545. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.4.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]