Abstract

There is evidence supporting a role for the -amino acid oxidase (DAO) locus in schizophrenia. This study aimed to determine the relationship of five single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within the DAO gene identified as promising schizophrenia risk genes (rs4623951, rs2111902, rs3918346, rs3741775, and rs3825251) to acoustic startle, prepulse inhibition (PPI), working memory, and personality dimensions. A highly homogeneous study entry cohort (n=530) of healthy, young male army conscripts (n=703) originating from the Greek LOGOS project (Learning On Genetics Of Schizophrenia Spectrum) underwent PPI of the acoustic startle reflex, working memory, and personality assessment. The QTPHASE from the UNPHASED package was used for the association analysis of each SNP or haplotype data, with p-values corrected for multiple testing by running 10 000 permutations of the data. The rs4623951_T-rs3741775_G and rs4623951_T-rs2111902_T diplotypes were associated with reduced PPI and worse performance in working memory tasks and a personality pattern characterized by attenuated anxiety. Median stratification analysis of the risk diplotype group (ie, those individuals homozygous for the T and G alleles (TG+)) showed reduced PPI and working memory performance only in TG+ individuals with high trait anxiety. The rs4623951_T allele, which is the DAO polymorphism most strongly associated with schizophrenia, might tag a haplotype that affects PPI, cognition, and personality traits in general population. Our findings suggest an influence of the gene in the neural substrate mediating sensorimotor gating and working memory, especially when combined with high anxiety and further validate DAO as a candidate gene for schizophrenia and spectrum disorders.

Keywords: prepulse inhibition, working memory, personality, -amino acid oxidase, schizophrenia

INTRODUCTION

Recent progress in psychiatric genetics has revealed several promising genetic susceptibility factors for schizophrenia, including -amino acid oxidase (DAO), a gene located in chromosome 12q24 (for review see Verrall et al, 2010). On the basis of association, interaction, and functional analyses, Chumakov et al (2002) were the first to suggest that the brain-expressed gene DAO exerts an influence on the susceptibility to schizophrenia. Conflicting association results have since been reported by a number of independent studies providing the usual mixture of positive (Corvin et al, 2007; Liu et al, 2004; Ohnuma et al, 2009; Schumacher et al, 2004; Wood et al, 2007) and negative (Fallin et al, 2005; Jonsson et al, 2009; Liu et al, 2006; Shinkai et al, 2007; Vilella et al, 2008; Yamada et al, 2005) findings.

This inconsistency may be partly because of the clinical and genetic heterogeneity of this disorder. One approach to overcome this issue is by applying an endophenotypic approach, which involves a quantitative, heritable, trait-related, laboratory-assessed intermediate phenotype that is identified in patients and to a lesser degree in their unaffected relatives or other high risk individuals (Gottesman and Gould, 2003). A wide range of schizophrenia endophenotypes including neuropsychological, neurophysiological, structural and functional brain abnormalities have been evaluated up to date, and their relationship with various candidate genes has been assessed. One of the most promising schizophrenia endophenotype is the prepulse inhibition (PPI) of the acoustic startle reflex.

PPI is thought to reflect sensorimotor gating, a form of central nervous system inhibition wherein irrelevant sensory information is filtered out during the early stages of processing so that attention can be focused on more salient features of the environment (Braff et al, 1978). PPI in rodents is modulated by activity in a well-defined cortico–striatopallido–pontine circuitry (Swerdlow et al, 2001), which has been confirmed with neuroimaging studies in human subjects (Campbell et al, 2007; Kumari et al, 2003, 2005a, 2007a; Postma et al, 2006). Consistent with these neuroimaging findings and the notion that sensorimotor gating is important in human cognition (Geyer et al, 1990), neuropsychological studies show that higher PPI levels predict superior executive function (Bitsios and Giakoumaki, 2005; Bitsios et al, 2006; Csomor et al, 2008; Giakoumaki et al, 2006), whereas deficient PPI is well documented in conditions with frontostriatal pathology and deficient executive function such as schizophrenia (Braff et al, 2001a; Kumari et al, 2007b; Swerdlow et al, 2006).

DAO is now of interest in psychiatry (see Verrall et al, 2010 for review) because its major substrate in the brain is -serine, a co-agonist of the N-methyl -aspartate type of ionotropic glutamate receptor (NMDAR). Deficiency of -serine signaling might contribute to NMDAR hypofunction, as there is evidence (1) for decreased -serine level in both serum and cerebrospinal fluid in schizophrenia (Bendikov et al, 2007; Hashimoto et al, 2003, 2005; Yamada et al, 2005); (2) that addition of -cycloserine to antipsychotic medication is beneficial for negative and probably cognitive symptoms (Coyle et al, 2002; Javitt, 2006; Shim et al, 2008; Tsai et al, 2006; Yang and Svensson, 2008); (3) -serine produces behavioral and neurochemical alterations consistent with these clinical effects in animal models (Andersen and Pouzet, 2004; Karasawa et al, 2008; Lipina et al, 2005; Nilsson et al, 1997; Olsen et al, 2006; Tanii et al, 1994). More specifically, exogenous DAO reduces NMDAR function in vivo and in vitro (Gustafson et al, 2007; Hama et al, 2006; Katsuki et al, 2004; Mothet et al, 2000; Ren et al, 2006; Stevens et al, 2003; Yang et al, 2005), mutant mouse strain ddY/DAO−, which lacks DAO activity shows increased cerebellar NMDAR function (Almond et al, 2006) and enhanced hippocampal NMDAR-dependent long-term potentiation (Maekawa et al, 2005), and finally, systemically administered DAO inhibitors produce effects consistent with enhanced NMDAR function. Thus, DAO has the capability to regulate the function of NMDAR through -serine breakdown and might contribute to NMDAR hypofunction in schizophrenia, or be relevant to its remediation.

Five DAO gene single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have been associated with schizophrenia and subjected to meta-analysis in the SZGene Database (http://www.schizophreniaforum.org/res/sczgene/default.asp; Allen et al, 2008). Our aim was to investigate whether these risk DAO variants were related to variations in PPI levels, performance in cognitive tasks and personality traits in the LOGOS (Learning On Genetics Of Schizophrenia Spectrum) cohort. This would provide more evidence for the role of DAO as a schizophrenia candidate gene and would further our understanding of its functional mechanisms within the human brain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Subjects were recruited from the first wave of the LOGOS study. This is a demographically and genetically highly homogeneous cohort of young male conscripts of the Greek Army with an age range 18–29 years (mean age 22.1±3), which has been described in detail previously (Roussos et al, 2010). Briefly here, following presentation of the study and written informed consent, 703 randomly selected young male conscripts were recruited between June 2008 and July 2009. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Crete, the Executive Army Bureau and the Bureau for the Protection of Personal and Sensitive Data of the Greek State. All subjects were thoroughly screened for past or current physical and mental health status by the army medical authorities, the study nurse and a trained research psychologist. Inclusion criteria were recent (last 2 months) conscript status in the camp and written informed consent. Exclusion criteria were left-handedness; personal history of head trauma, medical and neurological conditions, current use of prescribed drugs or a positive recreational drug screen; personal history of DSM-IV axis I disorders; and hearing threshold greater than 40 dB at 1 kHz.

Quantitative Trait Testing

Acoustic startle and PPI. A commercially available electromyographic (EMG) startle system (EMG SR-LAB; San Diego Instruments, San Diego, California) was used to examine the eye-blink component of the acoustic startle response from the right orbicularis oculi muscle. Pulses consisted of 40-ms, 115-dB white noise bursts, and prepulses consisted of 20-ms, 75-dB and 85-dB white noise bursts over 70-dB background noise. Recording began with 3 min of acclimation when only background noise was present. The recording period comprised 12 pulse-alone trials and 36 prepulse–pulse trials. As variation of the lead interval may tap different aspects of early information processing from preattentional (eg, 30 ms) to attentional (eg, 120 ms) stimulus processing, three lead intervals (onset to onset) were used (30, 60, and 120 ms). For each interval, there were six trials with 75 dB prepulse and six trials with 85 dB prepulse. All trials were presented in pseudorandom order with the constraint that no two identical trials occurred in succession. The intertrial interval varied between 9 and 23 s (average 15 s). The entire test session lasted ∼15 min. Only subjects with high quality startle and PPI data (no >1 (out of 6) missing trial per trial type and/or no >2 (out of 12) missing pulse-alone trials) were included for further analyses (n=445).

Neurocognitive assessment. We examined the performance in two different tasks that both recruit working memory process. We used one subtest of Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery Sahakian and Owen, 1992) namely, that spatial working memory (SWM) test, which is a non-verbal test administered with the aid of a high-resolution touch-sensitive screen (Advantech). Visual working memory was assessed with the N-Back Sequential Letter Task (Fletcher and Henson, 2001).

Personality questionnaires.All subjects were administered the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (EPQ; Eysenck et al, 1985), Cloninger's Temperament and Character Inventory (Cloninger et al, 1993), Spielberger's State-Trait Anxiety Inventory—Trait Scale (STAI-T; Spielberger, 1983), the Carver and White's Behavioral Inhibition/Behavioral Activation System (BIS/BAS) questionnaire (Carver and White, 1994), and the Schizotypal Traits Questionnaire Kelley and Coursey, 1992).

Genotyping

DNA was extracted from blood or cheek swab samples, using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The following five DAO SNPs were genotyped: rs4623951, rs2111902, rs3918346, rs3741775, and rs3825251, because they have been associated with schizophrenia in previous studies. Genotyping was performed blind to phenotype measures by K-Biosciences (Herts, United Kingdom; http://www.kbioscience.co.uk/) with a competitive allele-specific PCR system. Genotyping quality control was performed in 10% of the samples by duplicate checking (rate of concordance in duplicates >99%). Call rate was >96% for all polymorphisms.

Statistical Analysis

Comparison of the genotype groups for each SNP across demographic variables and baseline startle was performed using separate one-way analyses of variances (ANOVAs) or the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test as appropriate, based on deviation from normality. For the sake of data reduction and variables classification we submitted performance scores on all personality questionnaires to principal component analysis (PCA). Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) for five markers was checked using Haploview version 4.0 (Barrett et al, 2005). QTPHASE (http://www.mrc-bsu.cam.ac.uk/personal/frank/software/unphased/) from the UNPHASED package version 3.1.4 was used for the analysis of genotype associations (Dudbridge, 2003). QTPHASE uses a generalized linear model for quantitative traits assuming normal distribution of the trait. The trait mean given an individual's genotype data are based on an additive model of haplotypes. Haplotypes with frequencies <1% in the whole sample were excluded. We used a two-step procedure to correct for multiple testing. The p-values for the trait differences were corrected for multiple testing by running 10 000 permutations of the data. In each permutation, the quantitative scores are randomly re-assigned among subjects and the minimum p-value is compared with the minimum p-value over all the analyses in the original data. This allows for multiple testing corrections over all tests performed in a run. Next, as an additional method we set α to 0.01 level of significance. Results with a p<0.05 are shown only as ‘suggested findings' for future replication attempts. For each of those variants we performed separate mixed-model 3 × 2 × 3 (genotype by prepulse by interval) ANOVAs of %PPI and latency data and assessment of cognitive performance and personality traits using ANOVA or the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test as appropriate based on the deviation from normality. Pearson product–moment correlation coefficients were used to assess the relations between PPI and personality traits. On the basis of our sample size, we were able to detect a small to medium effect size, which for 80% power and α set to 0.01, was Cohen's d=0.33.

RESULTS

Table 1 summarizes the genotype distribution and minor allele frequency of the DAO polymorphisms in our sample. Genotype frequencies were distributed in accordance with HWE. There were no differences in demographic variables between the DAO genotypes for each SNP (Supplementary Table 1). The rs3918346, rs3741775, and rs3825251 were in strong linkage disequilibrium (Supplementary Table 2, Supplementary Figure 1).

Table 1. Genotype, Allele and MAFs of the DAO Polymorphisms.

| Marker (%) | Genotype | Allele | MAF | HWE p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs4623951 (97) | T/T 224 | T/C 219 | C/C 70 | T 667 | C 359 | 0.35 | 0.19 |

| rs2111902 (98.5) | T/T 204 | T/G 250 | G/G 67 | T 658 | G 384 | 0.37 | 0.56 |

| rs3918346 (96.2) | C/C 245 | C/T 213 | T/T 51 | C 703 | T 315 | 0.31 | 0.69 |

| rs3741775 (98.5) | T/T 180 | T/G 256 | G/G 86 | T 616 | G 428 | 0.41 | 0.82 |

| rs3825251 (98.1) | T/T 335 | T/C 166 | C/C 19 | T 836 | C 204 | 0.2 | 0.78 |

Abbreviations: DAO, -amino acid oxidase; HWE, Hardy–Weinberg expectation; MAF, minor allele frequency.

The allele distributions are consistent with HWE. The percentage in the marker column refers to call rate for each polymorphism.

Single-Marker Association Analysis

Table 2 shows the p-values of the association of DAO SNPs with startle and PPI as revealed by the QTPHASE after correction with permutation test. A pattern of association can be seen whereby the T allele of the rs4623951 variant was significantly associated with lower PPI levels at p<0.01 and p<0.05 in 85 db_60 ms and 85 db_30 ms trials, respectively. A mixed-model ANOVA of PPI with rs4623951 genotype as the grouping factor (three levels) and prepulse and interval as the within-subject factors revealed a genotype main effect at trend level (F(2, 428)=3, p=0.051, partial η2=0.016). We repeated the UNPHASED analysis and the follow up ANOVAs described above, taking baseline startle and/or smoking and/or IQ as the covariates; following this procedure the results did not change or the p-values slightly improved.

Table 2. Adjusted p-values from Permutation Test for Association of Startle and PPI for DAO Polymorphisms that Reached Significance at p<0.05.

| rs4623951 | rs2111902 | rs3918346 | rs3741775 | rs3825251 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline startle | 0.8 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.9 |

| PPI 75_30 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.8 |

| PPI 75_60 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.9 |

| PPI 75_120 | 0.23 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.7 |

| PPI 85_30 | 0.015 (−0.008) | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.4 |

| PPI 85_60 | 0.004 (−0.01) | 0.23 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.9 |

| PPI 85_120 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Pooled PPI | |||||

| PPI 30 ms | 0.13 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.8 | 0.5 |

| PPI 60 ms | 0.004 (−0.012) | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 1 |

| PPI 120 ms | 0.16 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.7 |

Abbreviations: DAO, -amino acid oxidase; PPI, prepulse inhibition.

Numbers represent the overall p-value for each single-nucleotide polymorphism after correction with permutation test. Numbers in brackets represent the estimated additive genetic value for the risk allele, relative to the protective common allele; plus or minus signs indicate increases or reductions in PPI respectively. The p-values <0.05 are in bold and italicized; p-values <0.01 are in bold. PPI data pooled across prepulse intensity are also shown for comparison.

Haplotype Analysis

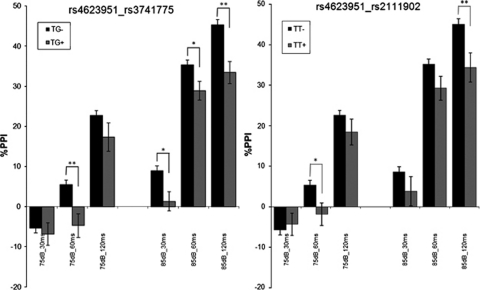

We performed association tests for the haplotype analysis using two-marker combinations (Table 3). Overall, we found that the diplotypes rs4623951_T-rs2111902_T and rs4623951_T-rs3741775_G were associated with PPI at p<0.01 in at least one trial type, and this did not change when the UNPHASED analysis was repeated with baseline startle and/or smoking and/or IQ as covariates. For rs4623951-rs2111902 and rs4623951-rs3741775 diplotypes we divided our population into risk and no-risk groups based on homozygosity for both risk SNPs. TG+ represents subjects that were homozygous for the rs4623951_T and rs3741775_G diplotype and TG− are the non-homozygous individuals. TT+ represents subjects that were homozygous for the rs4623951_T and rs2111902_T diplotype and TT− are the non-homozygous individuals. There were no differences in demographic variables between the DAO diplotypic groups (Supplementary Table 3). Following this grouping, we performed separate mixed-model ANOVAs of PPI data with diplotype as the grouping factor (risk, no-risk) and prepulse and interval as the within-subject factors. These ANOVAs revealed significant main effects of genotype (rs4623951-rs2111902: F(1, 429)=5, p=0.026, partial η2=0.013; rs4623951-rs3741775: F(1, 428)=9.8, p=0.002, partial η2=0.025), with risk (TT+ and TG+) individuals presenting with PPI reductions (Figure 1). These results did not change when covarying with baseline startle and/or smoking and/or IQ. There were no significant findings for latency data following identical analyses.

Table 3. Individual diplotype test for the DAO groups.

| Baseline startle | PPI 75_30 | PPI 75_60 | PPI 75_120 | PPI 85_30 | PPI 85_60 | PPI 85_120 | Pooled 30 ms | Pooled 60 ms | Pooled 120 ms | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs4623951, rs2111902 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.033, T-T: 0.005 (−0.012) | 0.15 | 0.2 | 0.005, C-T: 0.0006 (0.015) | 0.026, T-T: 0.01 (−0.01) | 0.4 | 0.007, T-T: 0.007 (−0.003) C-T: 0.003 (0.02) | 0.027, T-T: 0.016 (−0.01) |

| rs4623951, rs3918346 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.07 | 0.012, C-C: 0.001 (0.015) | 0.07 | 0.3 | 0.011, C-C: 0.003 (0.019) | 0.09 |

| rs4623951, rs3741775 | 0.4 | 0.036, C-G: 0.016 (0.019) | 0.0008, T-G: 0.008 (−0.013), C-G: 0.002 (0.023) | 0.036, C-G: 0.012 (0.021) | 0.006, T-G: 0.06 (−0.003), C-G: 0.002 (0.023) | 0.001, T-G: 0.02 (−0.005), C-G: 0.0009 (0.025) | 0.009, T-G: 0.04 (−0.009), C-G: 0.02 (0.017) | 0.006, C-G: 0.0009 (0.03) | 0.00006, T-G: 0.003 (−0.013), C-G: 0.0001 (0.033) | 0.005, C-G: 0.007 (0.025) |

| rs4623951, rs3825251 | 1 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.03, C-T: 0.004 (0.01) | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.03, C-T: 0.006 (0.01) | 0.6 |

| rs2111902, rs3918346 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.3 |

| rs2111902, rs3741775 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.1 |

| rs2111902, rs3825251 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.03 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.07 | 0.8 | 0.3 |

| rs3918346, rs3741775 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.7 |

| rs3918346, rs3825251 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.06 | 0.019 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.05 | 0.6 | 0.1 |

| rs3741775, rs3825251 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.7 |

Abbreviations: DAO, -amino acid oxidase; PPI, prepulse inhibition.

The number represents the overall p-value for diplotype. When the overall p-value was <0.05 we present p-value for specific alleles. The numbers in bracket represent the estimated additive genetic value between the specific diplotype and all other diplotypes pooled together. The p-values <0.05 are in bold and italicized; p-values <0.01 are in bold. PPI data pooled across prepulse intensity are also shown for comparison.

Figure 1.

Percent prepulse inhibition (%PPI) for rs4623951_rs3741775 TG− and TG+ groups (left) and rs4623951_rs2111902 TT− and TT+ groups (right). Bars represent SEM. TG+ and TT+ subjects had significantly lower PPI levels compared with the TG− and TT− individuals, respectively. A 2 × 2 × 3 (TG or TT status × prepulse × interval) mixed model ANOVA of PPI data revealed significant main effects of TG (F(1, 428)=9.8, p=0.002) and TT status (F(1, 429)=5, p=0.026) status. Identical results were revealed with PPI data pooled across prepulse intensity *p<0.05, **p<0.005.

Cognitive and Personality Variables

Table 4 shows the association of DAO rs4623951-rs3741775 and rs4623951-rs2111902 diplotype groups with our cognitive and personality phenotypic measures. Homozygosity (TG+ status) for the rs4623951_T and rs3741775_G diplotype was associated with statistically significant (p<0.001) lower number of correct responses in the three-back working memory test. In addition, TG+ individuals presented with lower anxious/negative mood as evidenced by higher EPQ extraversion (p<0.002) and lower STAI-T trait anxiety (p<0.01), TCI harm avoidance (p<0.02) and EPQ neuroticism (p<0.004).

Table 4. Comparison of Cognitive and Personality Variables for the DAO Diplotype Groups.

|

rs4623951–rs3741775 |

rs4623951–rs2111902 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TG− (n=456) | TG+ (n=68) | p-value | TT− (n=437) | TT+ (n=76) | p-value | |

| SWM (errors eight-box condition) | ||||||

| Within errors | 1.5±2.5 | 1.9±3.2 | 0.4 | 1.5±2.4 | 2.4±3.6 | 0.006 |

| Between errors | 12.3±10.5 | 12.2±10.6 | 0.9 | 12.1±10.7 | 13.8±9.6 | 0.2 |

| Strategy | 32.2±4 | 32.8±3.7 | 0.2 | 32.1±4.1 | 33.5±3.1 | 0.001 |

| N-back (correct responses) | ||||||

| Two-back | 2.5±0.8 | 2.6±0.8 | 0.7 | 2.5±0.8 | 2.4±0.8 | 0.5 |

| Three-back | 2.1±1 | 1.7±1.2 | 0.001 | 2.1±1 | 1.8±1.2 | 0.03 |

| STAI-T | ||||||

| STAI-T | 36.4±8.3 | 33.8±7.3 | 0.01 | 36.4±8.3 | 34.2±7.2 | 0.2 |

| EPQ | ||||||

| Psychoticism | 8.6±3.2 | 8.6±3.6 | 0.9 | 8.6±3.2 | 8.6±3.4 | 0.9 |

| Extraversion | 16.2±4.3 | 17.7±3.1 | 0.002 | 16.2±4.3 | 17.2±3.2 | 0.02 |

| Neuroticism | 10.4±5 | 8.6±4.3 | 0.004 | 10.2±5 | 9.6±4.8 | 0.3 |

| Lie | 10.4±4 | 10.3±4.7 | 0.9 | 10.4±4 | 10.7±4.3 | 0.6 |

Abbreviations: DAO, -amino acid oxidase; EPQ, Eysenck Personality Questionnaire; STAI-T; Spielberger's State-Trait Anxiety Inventory—Trait Scale; SWM, spatial working memory.

TG+ represents subjects homozygous for the rs4623951_T and rs3741775_G diplotype and TG− are the non-homozygous individuals. TT+ represents subjects homozygous for the rs4623951_T and rs2111902_T diplotype and TT− are the non-homozygous individuals. Numbers are group means±SD. The p-values <0.05 are in bold and italicized; p-values <0.01 are in bold. The p-values surviving correction for multiple testing (seven tests: corrected p=0.05/7=p<0.0071) are bold and underlined. Results from the TCI, Schizotypal Traits Questionnaire and Behavioral Inhibition/Behavioral Activation System did not reveal any significant associations (all p>0.1) and they are not shown.

Homozygosity for the rs4623951_T and rs2111902_T diplotype (TT+ status) was associated with statistically significant higher number of ‘within' errors in the eight-box condition (p<0.006) and poorer strategy development as evidenced by higher scores in strategy (p<0.001) in the SWM task and lower number of correct responses in the three-back working memory test (p<0.03). In addition, TT+ individuals presented with less negative mood as evidenced by higher EPQ extraversion scores (p<0.02). These results did not change after covarying for age, IQ, and smoking status.

Factor loadings from the rotated component matrix are shown in the Supplementary Table 4. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy (0.83) and Bartlett's test of sphericity (χ2=3246.1, d.f.=136, p<0.0001) indicated that the data were appropriate for factor analysis. Five factors emerged with Eigenvalues >1, suggesting a multidimensional structure, and this five-factor solution accounted for 71% of the total variance (see Supplementary Table 4). Homozygosity for the risk rs4623951_T and rs3741775_G diplotype was associated with statistically significant lower score in the anxiety factor (mean±SD: TG−, 0.04±1; TG+, −0.3±0.9; p=0.019; Cohen's d 0.33), but not in the other factors (all p>0.3). Similarly, TT+ individuals presented with lower score only in the anxiety factor (mean±SD: TT−, 0.04±1; TT+, −0.25±0.9; p=0.034; Cohen's d 0.3), but no significant differences were found in any other factor (all p>0.3). Results did not change after covarying for age, IQ, and smoking status.

Trait Anxiety, PPI and Cognition

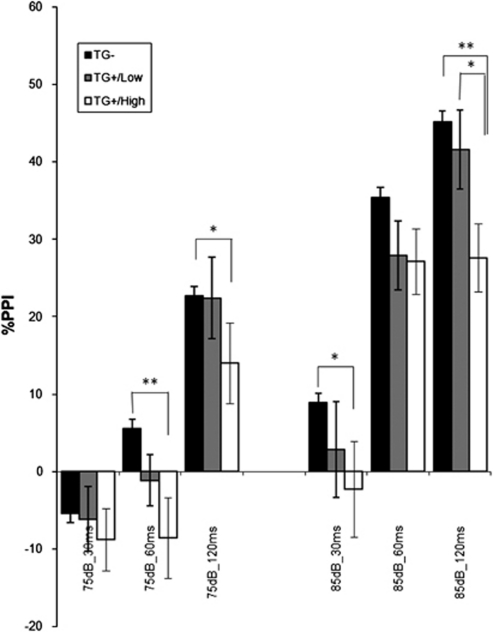

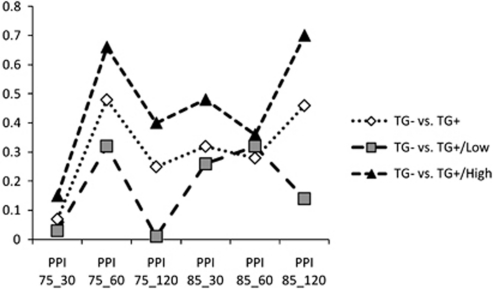

On the basis of weak association of rs4623951_T-rs2111902_T diplotype with personality (p=0.02) and the strong association of the rs4623951_T-rs3741775_G diplotype with personality traits, we further explored the association of the STAI-T trait anxiety, TCI harm avoidance and EPQ extraversion, and neuroticism with PPI trials within the TG+ and TG− groups. The only correlation within the TG+ group that passed the significance level after false discovery rate correction and α set to 0.01 was between STAI-T trait anxiety and PPI 85 db_120 ms (r=−0.334, d.f.=68; p<0.005). There were no significant correlations within the TG− group or the entire cohort or any correlations between STAI-T score and startle amplitude (all p-values >0.1). Median stratification of the TG+ group for STAI-T score, into low and high trait anxiety subgroups allowed groupwise comparison for PPI levels, with a mixed-model ANOVA with diplotype/anxiety as the grouping factor (TG−, TG+/low anxiety, TG+/high anxiety) and prepulse and interval as the within-subject factors. This analysis revealed a significant main effect of genotype (F(2, 441)=6.1, p<0.002), which was not altered when startle amplitude was taken as the covariate (F(2, 440)=6.1, p<0.003). Post hoc Bonferroni comparisons showed that PPI of the TG− group was greater than PPI of the highly anxious TG+ (p<0.003), but not the non-anxious TG+ (p>0.4) individuals (Figure 2). The three groups did not differ in terms of startle amplitude (F<1). Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 5 show the effect size (Cohen's d) among our diplotypic groups. The subgroup of TG+ subjects combined with high trait anxiety revealed the most significant PPI deficits. We applied similar analyses for working memory measures (two- and three-back, and SWM eight-box within/between error and strategy data) between the three groups (TG−, TG+/low, and TG+/high) and we found a significant effect for three-back working memory test (Kruskal–Wallis χ2=7.54, d.f.=2, p=0.023). Follow-up pairwise group comparisons revealed that the TG− individuals had significantly greater number of correct responses in three-back compared with TG+/high (Mann–Whitney test p=0.025) but not TG+/low (Mann–Whitney test p=0.081) groups.

Figure 2.

Percent prepulse inhibition (%PPI) for the TG− (n=456), the non-anxious risk TG+ (TG+/low; n=34) and the anxious risk TG+ (TG+/high; n=34) groups as revealed following median split in the TG+ trait anxiety score. Bars represent SEM. A 3 × 2 × 3 (TG status × prepulse × interval) mixed model ANOVA of PPI data revealed significant main effects of TG status (F(2, 441)=6.1, p<0.002). Post hoc Bonferroni comparisons revealed that PPI of the TG− group was greater than PPI of the high anxious TG+ only (p<0.003). *p<0.05, **p<0.005.

Figure 3.

Cohen's d effect size of the DAO diplotype groups. TG+ represents subjects homozygous for the rs4623951_T and rs3741775_G diplotype and TG− are the non-homozygous individuals. TG+/low and TG+/high groups represent subjects homozygous for the risk rs4623951_T and rs3741775_G diplotype, with low and high anxiety, respectively, following a median split of their trait anxiety score.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to examine the effect of multiple schizophrenia risk DAO genetic variants on PPI, working memory and personality traits. We provide strong evidence that two DAO diplotypes, were associated with reduced PPI and working memory performance and a personality pattern characterized by attenuated anxiety/negative mood; this pattern was confirmed when personality questionnaires were grouped according to PCA. Moreover, median stratification analysis of the risk TG+ diplotype group showed reduced PPI and working memory performance only in those TG+ individuals with high trait anxiety, with notable increases in the effect size of the PPI data (see Figure 3). It is also notable that while SNP analyses provided marginally significant results, highly significant findings were revealed after haplotype analyses. Importantly, the LOGOS cohort, is a demographically, ethnically and genetically highly homogeneous sample of healthy young males.

Both PPI and working memory are important schizophrenia endophenotypes. Given the central role of the PFC in working memory and the reported association between PPI and working memory possibly via a PFC link (Giakoumaki et al, 2008; Roussos et al, 2008b, 2009b), it is important although perhaps not too surprising that the risk DAO diplotypes affected both PPI and working memory, two functions characteristically deficient in schizophrenia. This finding confirms the role of DAO gene in the aetiopathogenesis of the disorder, and informs us on the potential routes by which these DAO variants increase risk for schizophrenia; it is indeed a possibility that the PPI and working memory attenuations seen in our risk diplotype groups (TG+ and TT+), reflect abnormalities in working memory and PPI overlapping circuitry, mediated via a DAO mechanism. It is important to emphasize that our subjects were normal functioning individuals and a ‘ceiling effect' on performance is therefore built into our study, making the positive effects even more remarkable. It has to be mentioned however, that reduced or deficient PPI is a feature of a family of conditions with frontal–striatal pathology such as Tourette and Fragile × syndromes, Huntington's disease or OCD (Geyer, 2006), whereas deficient working memory may be a common feature at least in Fragile × syndrome (Hashimoto et al, 2011) and OCD (Purcell et al, 1998). Future research therefore, should explore the involvement of these DAO diplotypes in the spectrum of these syndromes, rather than merely narrowly defined schizophrenia.

In view of the high comorbidity of anxiety to schizophrenia and spectrum disorders (Huppert and Smith, 2005; Lewandowski et al, 2006) and its implicit role in the transition from prodromal states into psychosis (Hazlett et al, 1997; Yung et al, 2003), it is surprising that the same risk diplotypes are associated with lower anxiety levels. Although this was an unexpected finding, given that our risk diplotypes are theoretically associated with higher DAO activity (see below), our results are in keeping with animal data showing that inhibition/abolishment of DAO activity, improves gating, and cognition but is anxiogenic (Almond et al, 2006; Basu et al, 2009; Labrie et al, 2009a, 2009b; Maekawa et al, 2005). Both diplotypes are highly prevalent in the general population (haplotype frequency: TG 36.2% and TT 38.2%) and it is possible that the risk for psychosis conferred, is compensated by an increase in emotional resilience against anxiety and negative mood. Similar conclusions have been reached for the COMT Val158Met (Enoch et al, 2003) and rs4818C/G polymorphisms (Roussos et al, 2010; Roussos et al, 2009b). It is important that the effect of the TG+ genetic variant on gating and working memory becomes more prominent in high anxiety individuals. Interestingly, patients with panic disorder present with a similar pattern of enduring gating deficits, ie, reduced PPI compared with controls which was more profound in patient subgroups with the highest trait (and state) anxiety (Ludewig et al, 2002). It would thus be interesting to re-examine gating in these patient samples stratified for at least the TG− and TG+ DAO variants. On the basis of these findings, we can further speculate that this risk DAO diplotype increases risk for schizophrenia and spectrum disorders when combined with other risk factors, such as genetic, epigenetic, or environmental ones that predispose to reduced resilience against stress.

As per SzGene database, the DAO SNP rs4623951 showed significant (p<0.026) association across all ethnicities, with a protective effect of the C allele (OR=0.88, 95% CI: 0.79–0.98). In a meta-analysis using only case–control data Sun et al (2008) showed that of the 75 genes that met a nominal p<0.05 overall significance, DAO was eighth in the list, with a combined OR of 1.31, p=1.1 × 10−6. Finally, Shi et al (2008) combined case–control and family-based studies and reported DAO as one of the 12 ‘top' genes. Conclusively, the three meta-analyses provide a moderate degree of support for an association between DAO and schizophrenia, specifically for rs4623951. However, neither have haplotype analyses been conducted, nor has a biological mechanism been identified. Nevertheless, DAO may be considered to be in the category of schizophrenia susceptibility genes for which there are reasonable grounds to defend, and continue to investigate its candidacy. The only previous study on the relationship between DAO and cognitive schizophrenia endophenotypes found no association of three DAO SNPs with performance on a broad range of cognitive tasks; importantly however, the rs4623951 was not analyzed in that study (Goldberg et al, 2006). Our findings strongly suggest that this allele when combined with the G and T alleles of the rs3741775 and rs2111902 variants, respectively, is an important determinant of PPI and working memory in healthy subjects. Given the increasing prominence of PPI as a strong schizophrenia endophenotype, our study encourages further exploration of these variants in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia.

The mechanism underlying any genetic association of DAO with schizophrenia remains unclear. As the associated SNPs in the DAO gene are either non-coding or synonymous, any pathophysiological functionality is likely exerted through an effect on DAO expression. In turn, the altered DAO expression could affect -serine or other DAO substrate levels as recent findings support that DAO expression and activity are increased in schizophrenia (Bendikov et al, 2007; Burnet et al, 2008; Kapoor et al, 2006; Madeira et al, 2008; Verrall et al, 2007). However, there was no genotype effect (including rs4623951) on DAO expression/activity or serum -serine levels (Burnet et al, 2008; Yamada et al, 2005). Thus, there is not yet evidence to support the proposed molecular basis for the association of DAO with schizophrenia, although these negative studies are not definitive in terms of either SNP coverage, haplotypic assessment, or sample size.

As described in the introduction, DAO has the capability to regulate the function of NMDAR through -serine breakdown and might contribute to NMDAR hypofunction in schizophrenia, or be relevant to its remediation. Complementing these data, DAO inhibition can correct NMDAR antagonist-induced deficits in PPI (Adage et al, 2008; Hashimoto et al, 2009; Horio et al, 2009). Moreover, serine racemase genetically modified mice with a ∼90% -serine depletion have impaired spatial memory (Basu et al, 2009) and reduced PPI (Labrie et al, 2009b), indirectly supporting the possibility that restoring -serine levels may be therapeutic against such deficits in schizophrenia. Importantly, ddY/DAO− mice exhibit increased anxiety (Labrie et al, 2009a), suggesting a possible anxiogenic side effect of DAO inhibition. Although the exact mechanism underlying the genetic association of DAO with schizophrenia-related endophenotypes remains unknown, based on the preclinical data and the results of the present human study we can speculate that the risk diplotypes might predict augmented expression activity of the DAO enzyme.

Because DAO activity seems to be increased in schizophrenia leading to NMDAR hypofunction, DAO inhibition is receiving attention as a potential alternative therapeutic mean (Verrall et al, 2010). It is intriguing that chlorpromazine was shown to be a DAO inhibitor in vitro >50 years ago (Yagi et al, 1956), a finding which was confirmed recently(Iwana et al, 2008) and was also extended to risperidone (Abou El-Magd et al, 2010); as clinical trials with DAO inhibitors in schizophrenia are lacking, it is unclear whether these observations are clinically relevant, however, they do provide a precedent for the potential therapeutic benefits of selective DAO inhibitors. Although findings from preclinical studies remain preliminary, they show that DAO inactivation, either in ddY/DAO− mice or after pharmacological DAO inhibition in rats and mice, produces behavioral, electrophysiological, and neurochemical effects suggestive of a pro-cognitive profile. Thus, studying the behavioral and cognitive impact of high-risk polymorphisms might provide fruitful results for applying pharmacogenomic approaches that will enhance the development of personalized treatment.

Sensorimotor-gating deficits are consistently observed in schizophrenia patients (Braff et al, 2001b; Kumari et al, 2007b; Kumari et al, 2000; Ludewig et al, 2003; Swerdlow et al, 2006), their first-degree relatives (Cadenhead et al, 2000; Kumari et al, 2005b) and individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorder (Cadenhead et al, 2000; Quednow et al, 2008a), although they are not specific (Geyer, 2006). Twin (Anokhin et al, 2003) and family (Aukes et al, 2008; Greenwood et al, 2007) studies demonstrate that PPI is heritable and a growing number of recent genetic association studies have begun to elucidate its genetic architecture (Giakoumaki et al, 2008; Hong et al, 2008; Petrovsky et al, 2010; Quednow et al, 2008b, 2009, 2010; Roussos et al, 2010; Roussos et al, 2008a, 2008b, 2009a, 2009b). Interestingly, PPI showed a simple mode of transmission which is useful for successful application in molecular genetic research, whereas other endophenotypes, such as verbal fluency and SWM, demonstrated a polygenic, multifactorial model (Aukes et al, 2008), suggesting that PPI can be a superior endophenotype for identification of genetic variants in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Conclusively, PPI has emerged as an important and validated endophenotypic marker, cross-fertilizing genetic studies of schizophrenia.

The LOGOS cohort provides a comprehensive endophenotypic assessment of schizophrenia-related intermediate phenotypes in a demographically and genetically homogeneous population of healthy, young, Greek males. This sample homogeneity coupled with high reliability of PPI recording (Abel et al, 1998; Flaten, 2002) and our stringent scoring criteria, increase multiplicatively the power of this cohort to detect genetic variants, thus obviating type I and II errors (Gottesman and Gould, 2003). Importantly, the healthy male volunteer model of studying functional mechanisms of genes is devoid of confounds which strongly impact the study and interpretation of PPI deficits in patient populations, such as gender and medication (Kumari et al, 2004; Swerdlow et al, 2006), presence of symptoms (Braff et al, 1999, 2001a) and the brain effects of psychiatric illness episodes. Last but not least, automatic sensorimotor gating as measured by the uninstructed PPI paradigm is uniquely independent of subjects' motivation, engagement, and social desirability biases. All the above taken together, increase confidence in the conclusions reached, about the functional mechanisms of the DAO gene. In the same cohort, we recently demonstrated a significant association of NRG1 SNPs with PPI (Roussos et al 2010). Because NRG1 and its erbB4 receptor control glutamatergic synapse maturation, modulation and plasticity (Li et al, 2007; Bjarnadottir et al, 2007), it is possible that genetic variants of both NRG1 and DAO gene might converge on glutamatergic hypofunction. Interestingly, both our NRG1 and the present DAO findings explain a small amount of PPI variance (∼1–3%), compared with the 10–20% of explained variance in previous studies when dopaminergic genes were examined (Roussos et al, 2008a, 2008b; Quednow et al, 2009, 2010). The reason for this may be that the effects of dopamine genes are more proximal to the PPI endophenotype, as dopaminergic neurotransmission is directly relevant to PPI physiology, potently regulating PPI within its well identified neural circuitry (Geyer et al, 2001, Swerdlow et al, 2001). Other plausible reasons include overestimation of the effects of the dopaminergic gene variants as these were studied in independent smaller (n∼100) samples compared with the much larger LOGOS cohort.

In conclusion, we provide the first phenotypic configuration in a large and demographically/genetically highly homogeneous cohort of young healthy males carrying the DAO risk alleles. Pending replication, our findings suggest an influence of the gene in the neural substrate mediating sensorimotor gating and working memory, especially when combined with high anxiety and further validate DAO as a candidate gene for the schizophrenia and spectrum disorders.

Acknowledgments

PR was supported by a ‘Manasaki Foundation' scholarship.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Neuropsychopharmacology website (http://www.nature.com/npp)

Supplementary Material

References

- Abel K, Waikar M, Pedro B, Hemsley D, Geyer M. Repeated testing of prepulse inhibition and habituation of the startle reflex: a study in healthy human controls. J Psychopharmacol. 1998;12:330–337. doi: 10.1177/026988119801200402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abou El-Magd RM, Park HK, Kawazoe T, Iwana S, Ono K, Chung SP, et al. The effect of risperidone on D-amino acid oxidase activity as a hypothesis for a novel mechanism of action in the treatment of schizophrenia. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24:1055–1067. doi: 10.1177/0269881109102644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adage T, Trillat AC, Quattropani A, Perrin D, Cavarec L, Shaw J, et al. In vitro and in vivo pharmacological profile of AS057278, a selective d-amino acid oxidase inhibitor with potential anti-psychotic properties. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;18:200–214. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen NC, Bagade S, McQueen MB, Ioannidis JP, Kavvoura FK, Khoury MJ, et al. Systematic meta-analyses and field synopsis of genetic association studies in schizophrenia: the SzGene database. Nat Genet. 2008;40:827–834. doi: 10.1038/ng.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almond SL, Fradley RL, Armstrong EJ, Heavens RB, Rutter AR, Newman RJ, et al. Behavioral and biochemical characterization of a mutant mouse strain lacking D-amino acid oxidase activity and its implications for schizophrenia. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2006;32:324–334. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen JD, Pouzet B. Spatial memory deficits induced by perinatal treatment of rats with PCP and reversal effect of D-serine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:1080–1090. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anokhin AP, Heath AC, Myers E, Ralano A, Wood S. Genetic influences on prepulse inhibition of startle reflex in humans. Neurosci Lett. 2003;353:45–48. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aukes MF, Alizadeh BZ, Sitskoorn MM, Selten JP, Sinke RJ, Kemner C, et al. Finding suitable phenotypes for genetic studies of schizophrenia: heritability and segregation analysis. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:128–136. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu AC, Tsai GE, Ma CL, Ehmsen JT, Mustafa AK, Han L, et al. Targeted disruption of serine racemase affects glutamatergic neurotransmission and behavior. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14:719–727. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendikov I, Nadri C, Amar S, Panizzutti R, De Miranda J, Wolosker H, et al. A CSF and postmortem brain study of D-serine metabolic parameters in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2007;90:41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitsios P, Giakoumaki SG. Relationship of prepulse inhibition of the startle reflex to attentional and executive mechanisms in man. Int J Psychophysiol. 2005;55:229–241. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitsios P, Giakoumaki SG, Theou K, Frangou S. Increased prepulse inhibition of the acoustic startle response is associated with better strategy formation and execution times in healthy males. Neuropsychologia. 2006;44:2494–2499. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjarnadottir M, Misner DL, Haverfield-Gross S, Bruun S, Helgason VG, Stefansson H, et al. Neuregulin1 (NRG1) signaling through Fyn modulates NMDA receptor phosphorylation: differential synaptic function in NRG1± knock-outs compared with wild-type mice. J Neurosci. 2007;27:4519–4529. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4314-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braff D, Stone C, Callaway E, Geyer M, Glick I, Bali L. Prestimulus effects on human startle reflex in normals and schizophrenics. Psychophysiology. 1978;15:339–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1978.tb01390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braff DL, Geyer MA, Light GA, Sprock J, Perry W, Cadenhead KS, et al. Impact of prepulse characteristics on the detection of sensorimotor gating deficits in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2001a;49:171–178. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(00)00139-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braff DL, Geyer MA, Swerdlow NR. Human studies of prepulse inhibition of startle: normal subjects, patient groups, and pharmacological studies. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001b;156:234–258. doi: 10.1007/s002130100810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braff DL, Swerdlow NR, Geyer MA. Symptom correlates of prepulse inhibition deficits in male schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:596–602. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.4.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnet PW, Eastwood SL, Bristow GC, Godlewska BR, Sikka P, Walker M, et al. D-amino acid oxidase activity and expression are increased in schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:658–660. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadenhead KS, Swerdlow NR, Shafer KM, Diaz M, Braff DL. Modulation of the startle response and startle laterality in relatives of schizophrenic patients and in subjects with schizotypal personality disorder: evidence of inhibitory deficits. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1660–1668. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell LE, Hughes M, Budd TW, Cooper G, Fulham WR, Karayanidis F, et al. Primary and secondary neural networks of auditory prepulse inhibition: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study of sensorimotor gating of the human acoustic startle response. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26:2327–2333. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver C, White T. Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: the BIS/BAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994;67:319–333. [Google Scholar]

- Chumakov I, Blumenfeld M, Guerassimenko O, Cavarec L, Palicio M, Abderrahim H, et al. Genetic and physiological data implicating the new human gene G72 and the gene for D-amino acid oxidase in schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:13675–13680. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182412499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger CR, Svrakic DM, Przybeck TR. A psychobiological model of temperament and character. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:975–990. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820240059008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corvin A, McGhee KA, Murphy K, Donohoe G, Nangle JM, Schwaiger S, et al. Evidence for association and epistasis at the DAOA/G30 and D-amino acid oxidase loci in an Irish schizophrenia sample. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2007;144B:949–953. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle JT, Tsai G, Goff DC. Ionotropic glutamate receptors as therapeutic targets in schizophrenia. Curr Drug Targets CNS Neurol Disord. 2002;1:183–189. doi: 10.2174/1568007024606212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csomor PA, Stadler RR, Feldon J, Yee BK, Geyer MA, Vollenweider FX. Haloperidol differentially modulates prepulse inhibition and p50 suppression in healthy humans stratified for low and high gating levels. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:497–512. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudbridge F. Pedigree disequilibrium tests for multilocus haplotypes. Genet Epidemiol. 2003;25:115–121. doi: 10.1002/gepi.10252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enoch MA, Xu K, Ferro E, Harris CR, Goldman D. Genetic origins of anxiety in women: a role for a functional catechol-O-methyltransferase polymorphism. Psychiatr Genet. 2003;13:33–41. doi: 10.1097/00041444-200303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck S, Eysenck H, Barrett P. A revised version of the psychoticism scale. Person Individ Diff. 1985;6:21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Fallin MD, Lasseter VK, Avramopoulos D, Nicodemus KK, Wolyniec PS, McGrath JA, et al. Bipolar I disorder and schizophrenia: a 440-single-nucleotide polymorphism screen of 64 candidate genes among Ashkenazi Jewish case-parent trios. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:918–936. doi: 10.1086/497703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaten MA. Test-retest reliability of the somatosensory blink reflex and its inhibition. Int J Psychophysiol. 2002;45:261–265. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8760(02)00034-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher PC, Henson RN. Frontal lobes and human memory: insights from functional neuroimaging. Brain. 2001;124:849–881. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.5.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer MA. The family of sensorimotor gating disorders: comorbidities or diagnostic overlaps. Neurotox Res. 2006;10:211–220. doi: 10.1007/BF03033358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer MA, Krebs-Thompson K, Braff DL, Swerdlow NR. Pharmacological studies of prepulse inhibition models of sensorimotor gating deficits in schizophrenia: a decade in review. Psychopharmacology. 2001;156:117–154. doi: 10.1007/s002130100811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer MA, Swerdlow NR, Mansbach RS, Braff DL. Startle response models of sensorimotor gating and habituation deficits in schizophrenia. Brain Res Bull. 1990;25:485–498. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(90)90241-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giakoumaki SG, Bitsios P, Frangou S. The level of prepulse inhibition in healthy individuals may index cortical modulation of early information processing. Brain Res. 2006;1078:168–170. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.01.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giakoumaki SG, Roussos P, Bitsios P. Improvement of prepulse inhibition and executive function by the COMT inhibitor tolcapone depends on COMT Val158Met polymorphism. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:3058–3068. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg TE, Straub RE, Callicott JH, Hariri A, Mattay VS, Bigelow L, et al. The G72/G30 gene complex and cognitive abnormalities in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2022–2032. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottesman II, Gould TD. The endophenotype concept in psychiatry: etymology and strategic intentions. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:636–645. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.4.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood TA, Braff DL, Light GA, Cadenhead KS, Calkins ME, Dobie DJ, et al. Initial heritability analyses of endophenotypic measures for schizophrenia: the consortium on the genetics of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:1242–1250. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.11.1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson EC, Stevens ER, Wolosker H, Miller RF. Endogenous D-serine contributes to NMDA-receptor-mediated light-evoked responses in the vertebrate retina. J Neurophysiol. 2007;98:122–130. doi: 10.1152/jn.00057.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hama Y, Katsuki H, Tochikawa Y, Suminaka C, Kume T, Akaike A. Contribution of endogenous glycine site NMDA agonists to excitotoxic retinal damage in vivo. Neurosci Res. 2006;56:279–285. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K, Engberg G, Shimizu E, Nordin C, Lindstrom LH, Iyo M. Reduced D-serine to total serine ratio in the cerebrospinal fluid of drug naive schizophrenic patients. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2005;29:767–769. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K, Fujita Y, Horio M, Kunitachi S, Iyo M, Ferraris D, et al. Co-administration of a D-amino acid oxidase inhibitor potentiates the efficacy of D-serine in attenuating prepulse inhibition deficits after administration of dizocilpine. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:1103–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K, Fukushima T, Shimizu E, Komatsu N, Watanabe H, Shinoda N, et al. Decreased serum levels of -serine in patients with schizophrenia: evidence in support of the N-methyl--aspartate receptor hypofunction hypothesis of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:572–576. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.6.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto RI, Backer KC, Tassone F, Hagerman RJ, Rivera SM. An fMRI study of the prefrontal activity during the performance of a working memory task in premutation carriers of the fragile × mental retardation 1 gene with and without fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome (FXTAS) J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazlett H, Dawson ME, Schell AM, Nuechterlein KH. Electrodermal activity as a prodromal sign in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;41:111–113. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(96)00351-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong LE, Wonodi I, Stine OC, Mitchell BD, Thaker GK. Evidence of missense mutations on the neuregulin 1 gene affecting function of prepulse inhibition. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horio M, Fujita Y, Ishima T, Iyo M, Ferraris D, Tsukamoto T, et al. Effects of -amino acid oxidase inhibitor on the extracellular -alanine levels and the efficacy of -alanine on dizocilpine induced prepulse inhibition deficits in mice. Open Clin Chem J. 2009;2:16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Huppert JD, Smith TE. Anxiety and schizophrenia: the interaction of subtypes of anxiety and psychotic symptoms. CNS Spectr. 2005;10:721–731. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900019714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwana S, Kawazoe T, Park HK, Tsuchiya K, Ono K, Yorita K, et al. Chlorpromazine oligomer is a potentially active substance that inhibits human -amino acid oxidase, product of a susceptibility gene for schizophrenia. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2008;23:901–911. doi: 10.1080/14756360701745478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javitt DC. Is the glycine site half saturated or half unsaturated? Effects of glutamatergic drugs in schizophrenia patients. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2006;19:151–157. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000214340.14131.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson EG, Saetre P, Vares M, Andreou D, Larsson K, Timm S, et al. DTNBP1, NRG1, DAOA, DAO and GRM3 polymorphisms and schizophrenia: an association study. Neuropsychobiology. 2009;59:142–150. doi: 10.1159/000218076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor R, Lim KS, Cheng A, Garrick T, Kapoor V. Preliminary evidence for a link between schizophrenia and NMDA-glycine site receptor ligand metabolic enzymes, d-amino acid oxidase (DAAO) and kynurenine aminotransferase-1 (KAT-1) Brain Res. 2006;1106:205–210. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.05.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karasawa J, Hashimoto K, Chaki S. -Serine and a glycine transporter inhibitor improve MK-801-induced cognitive deficits in a novel object recognition test in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2008;186:78–83. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsuki H, Nonaka M, Shirakawa H, Kume T, Akaike A. Endogenous -serine is involved in induction of neuronal death by N-methyl--aspartate and simulated ischemia in rat cerebrocortical slices. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;311:836–844. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.070912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley M, Coursey R. Factor structure of schizotypy scales. Pers Individ Diff. 1992;13:723–731. [Google Scholar]

- Kumari V, Aasen I, Sharma T. Sex differences in prepulse inhibition deficits in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2004;69:219–235. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2003.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari V, Antonova E, Geyer MA, Ffytche D, Williams SC, Sharma T. A fMRI investigation of startle gating deficits in schizophrenia patients treated with typical or atypical antipsychotics. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2007a;10:463–477. doi: 10.1017/S1461145706007139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari V, Antonova E, Zachariah E, Galea A, Aasen I, Ettinger U, et al. Structural brain correlates of prepulse inhibition of the acoustic startle response in healthy humans. Neuroimage. 2005a;26:1052–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari V, Das M, Zachariah E, Ettinger U, Sharma T. Reduced prepulse inhibition in unaffected siblings of schizophrenia patients. Psychophysiology. 2005b;42:588–594. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2005.00346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari V, Fannon D, Sumich AL, Sharma T. Startle gating in antipsychotic-naive first episode schizophrenia patients: one ear is better than two. Psychiatry Res. 2007b;151:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari V, Gray JA, Geyer MA, ffytche D, Soni W, Mitterschiffthaler MT, et al. Neural correlates of tactile prepulse inhibition: a functional MRI study in normal and schizophrenic subjects. Psychiatry Res. 2003;122:99–113. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4927(02)00123-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari V, Soni W, Mathew VM, Sharma T. Prepulse inhibition of the startle response in men with schizophrenia: effects of age of onset of illness, symptoms, and medication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:609–614. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.6.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrie V, Clapcote SJ, Roder JC. Mutant mice with reduced NMDA-NR1 glycine affinity or lack of -amino acid oxidase function exhibit altered anxiety-like behaviors. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009a;91:610–620. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrie V, Fukumura R, Rastogi A, Fick LJ, Wang W, Boutros PC, et al. Serine racemase is associated with schizophrenia susceptibility in humans and in a mouse model. Hum Mol Genet. 2009b;18:3227–3243. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowski KE, Barrantes-Vidal N, Nelson-Gray RO, Clancy C, Kepley HO, Kwapil TR. Anxiety and depression symptoms in psychometrically identified schizotypy. Schizophr Res. 2006;83:225–235. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Woo RS, Mei L, Malinow R. The neuregulin-1 receptor erbB4 controls glutamatergic synapse maturation and plasticity. Neuron. 2007;54:583–597. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipina T, Labrie V, Weiner I, Roder J. Modulators of the glycine site on NMDA receptors, -serine and ALX 5407, display similar beneficial effects to clozapine in mouse models of schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;179:54–67. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-2210-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, He G, Wang X, Chen Q, Qian X, Lin W, et al. Association of DAAO with schizophrenia in the Chinese population. Neurosci Lett. 2004;369:228–233. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.07.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YL, Fann CS, Liu CM, Chang CC, Wu JY, Hung SI, et al. No association of G72 and -amino acid oxidase genes with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2006;87:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludewig K, Geyer MA, Vollenweider FX. Deficits in prepulse inhibition and habituation in never-medicated, first-episode schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:121–128. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01925-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludewig S, Ludewig K, Geyer MA, Hell D, Vollenweider FX. Prepulse inhibition deficits in patients with panic disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2002;15:55–60. doi: 10.1002/da.10026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madeira C, Freitas ME, Vargas-Lopes C, Wolosker H, Panizzutti R. Increased brain -amino acid oxidase (DAAO) activity in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2008;101:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maekawa M, Watanabe M, Yamaguchi S, Konno R, Hori Y. Spatial learning and long-term potentiation of mutant mice lacking -amino-acid oxidase. Neurosci Res. 2005;53:34–38. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mothet JP, Parent AT, Wolosker H, Brady RO, Jr, Linden DJ, Ferris CD, et al. -Serine is an endogenous ligand for the glycine site of the N-methyl--aspartate receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:4926–4931. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.9.4926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson M, Carlsson A, Carlsson ML. Glycine and -serine decrease MK-801-induced hyperactivity in mice. J Neural Transm. 1997;104:1195–1205. doi: 10.1007/BF01294720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnuma T, Shibata N, Maeshima H, Baba H, Hatano T, Hanzawa R, et al. Association analysis of glycine- and serine-related genes in a Japanese population of patients with schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2009;33:511–518. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen CK, Kreilgaard M, Didriksen M. Positive modulation of glutamatergic receptors potentiates the suppressive effects of antipsychotics on conditioned avoidance responding in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2006;84:259–265. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrovsky N, Quednow BB, Ettinger U, Schmechtig A, Mossner R, Collier DA, et al. Sensorimotor gating is associated with CHRNA3 polymorphisms in schizophrenia and healthy volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:1429–1439. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postma P, Gray JA, Sharma T, Geyer M, Mehrotra R, Das M, et al. A behavioural and functional neuroimaging investigation into the effects of nicotine on sensorimotor gating in healthy subjects and persons with schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;184:589–599. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0307-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell R, Maruff P, Kyrios M, Pantelis C. Neuropsychological deficits in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a comparison with unipolar depression, panic disorder, and normal controls. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:415–423. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.5.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quednow BB, Frommann I, Berning J, Kuhn KU, Maier W, Wagner M. Impaired sensorimotor gating of the acoustic startle response in the prodrome of schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2008a;64:766–773. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quednow BB, Kuhn KU, Mossner R, Schwab SG, Schuhmacher A, Maier W, et al. Sensorimotor gating of schizophrenia patients is influenced by 5-HT2A receptor polymorphisms. Biol Psychiatry. 2008b;64:434–437. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quednow BB, Schmechtig A, Ettinger U, Petrovsky N, Collier DA, Vollenweider FX, et al. Sensorimotor gating depends on polymorphisms of the serotonin-2A receptor and catechol-O-methyltransferase, but not on neuregulin-1 Arg38Gln genotype: a replication study. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66:614–620. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quednow BB, Wagner M, Mossner R, Maier W, Kuhn KU. Sensorimotor gating of schizophrenia patients depends on Catechol O-methyltransferase Val158Met polymorphism. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36:341–346. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren WH, Guo JD, Cao H, Wang H, Wang PF, Sha H, et al. Is endogenous -serine in the rostral anterior cingulate cortex necessary for pain-related negative affect. J Neurochem. 2006;96:1636–1647. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roussos P, Giakoumaki S, Adamaki E, Bitsios P. The influence of schizophrenia-related neuregulin-1 polymorphisms on sensorimotor gating in healthy males. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;In:press. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roussos P, Giakoumaki SG, Bitsios P. The dopamine D(3) receptor Ser9Gly polymorphism modulates prepulse inhibition of the acoustic startle reflex. Biol Psychiatry. 2008a;64:235–240. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roussos P, Giakoumaki SG, Bitsios P. A risk PRODH haplotype affects sensorimotor gating, memory, schizotypy, and anxiety in healthy male subjects. Biol Psychiatry. 2009a;65:1063–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roussos P, Giakoumaki SG, Bitsios P. Tolcapone effects on gating, working memory, and mood interact with the synonymous catechol-O-methyltransferase rs4818c/g polymorphism. Biol Psychiatry. 2009b;66:997–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roussos P, Giakoumaki SG, Rogdaki M, Pavlakis S, Frangou S, Bitsios P. Prepulse inhibition of the startle reflex depends on the catechol O-methyltransferase Val158Met gene polymorphism. Psychol Med. 2008b;38:1651–1658. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708002912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahakian BJ, Owen AM. Computerized assessment in neuropsychiatry using CANTAB: discussion paper. J R Soc Med. 1992;85:399–402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher J, Jamra RA, Freudenberg J, Becker T, Ohlraun S, Otte AC, et al. Examination of G72 and -amino-acid oxidase as genetic risk factors for schizophrenia and bipolar affective disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9:203–207. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J, Gershon ES, Liu C. Genetic associations with schizophrenia: meta-analyses of 12 candidate genes. Schizophr Res. 2008;104:96–107. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim SS, Hammonds MD, Kee BS. Potentiation of the NMDA receptor in the treatment of schizophrenia: focused on the glycine site. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008;258:16–27. doi: 10.1007/s00406-007-0757-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinkai T, De Luca V, Hwang R, Muller DJ, Lanktree M, Zai G, et al. Association analyses of the DAOA/G30 and -amino-acid oxidase genes in schizophrenia: further evidence for a role in schizophrenia. Neuromolecular Med. 2007;9:169–177. doi: 10.1007/BF02685890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger C. Manual For The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens ER, Esguerra M, Kim PM, Newman EA, Snyder SH, Zahs KR, et al. -Serine and serine racemase are present in the vertebrate retina and contribute to the physiological activation of NMDA receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:6789–6794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1237052100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Kuo PH, Riley BP, Kendler KS, Zhao Z. Candidate genes for schizophrenia: a survey of association studies and gene ranking. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2008;147B:1173–1181. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow NR, Geyer MA, Braff DL. Neural circuit regulation of prepulse inhibition of startle in the rat: current knowledge and future challenges. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;156:194–215. doi: 10.1007/s002130100799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow NR, Light GA, Cadenhead KS, Sprock J, Hsieh MH, Braff DL. Startle gating deficits in a large cohort of patients with schizophrenia: relationship to medications, symptoms, neurocognition, and level of function. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:1325–1335. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.12.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanii Y, Nishikawa T, Hashimoto A, Takahashi K. Stereoselective antagonism by enantiomers of alanine and serine of phencyclidine-induced hyperactivity, stereotypy and ataxia in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;269:1040–1048. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai GE, Yang P, Chang YC, Chong MY. -Alanine added to antipsychotics for the treatment of schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:230–234. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verrall L, Burnet PW, Betts JF, Harrison PJ. The neurobiology of -amino acid oxidase and its involvement in schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15:122–137. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verrall L, Walker M, Rawlings N, Benzel I, Kew JN, Harrison PJ, et al. -Amino acid oxidase and serine racemase in human brain: normal distribution and altered expression in schizophrenia. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26:1657–1669. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05769.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilella E, Costas J, Sanjuan J, Guitart M, De Diego Y, Carracedo A, et al. Association of schizophrenia with DTNBP1 but not with DAO, DAOA, NRG1 and RGS4 nor their genetic interaction. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;42:278–288. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood LS, Pickering EH, Dechairo BM. Significant support for DAO as a schizophrenia susceptibility locus: examination of five genes putatively associated with schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:1195–1199. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagi K, Nagatsu T, Ozawa T. Inhibitory action of chlorpromazine on the oxidation of -amino-acid in the diencephalon part of the brain. Nature. 1956;177:891–892. doi: 10.1038/177891a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K, Ohnishi T, Hashimoto K, Ohba H, Iwayama-Shigeno Y, Toyoshima M, et al. Identification of multiple serine racemase (SRR) mRNA isoforms and genetic analyses of SRR and DAO in schizophrenia and -serine levels. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:1493–1503. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang CR, Svensson KA. Allosteric modulation of NMDA receptor via elevation of brain glycine and -serine: the therapeutic potentials for schizophrenia. Pharmacol Ther. 2008;120:317–332. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S, Qiao H, Wen L, Zhou W, Zhang Y. -Serine enhances impaired long-term potentiation in CA1 subfield of hippocampal slices from aged senescence-accelerated mouse prone/8. Neurosci Lett. 2005;379:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yung AR, Phillips LJ, Yuen HP, Francey SM, McFarlane CA, Hallgren M, et al. Psychosis prediction: 12-month follow up of a high-risk (“prodromal”) group. Schizophr Res. 2003;60:21–32. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(02)00167-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.