Abstract

Purpose

To determine dose-limiting toxicities, maximum-tolerated dose (MTD), pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of weekly intravenous temsirolimus, a mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway inhibitor, in pediatric patients with recurrent or refractory solid tumors.

Patients and Methods

Cohorts of three to six patients 1 to 21 years of age with recurrent or refractory solid tumors were treated with a 1-hour intravenous infusion of temsirolimus weekly for 3 weeks per course at one of four dose levels: 10, 25, 75, or 150 mg/m2. During the first two courses, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic evaluations (phosphorylation of S6, AKT, and 4EBP1 in peripheral-blood mononuclear cells) were performed.

Results

Dose-limiting toxicity (grade 3 anorexia) occurred in one of 18 evaluable patients at the 150 mg/m2 level, which was determined to be tolerable, and an MTD was not identified. In 13 patients evaluable for response after two courses of therapy, one had complete response (CR; neuroblastoma) and five had stable disease (SD). Four patients (three SDs + one CR) remained on treatment for more than 4 months. The sum of temsirolimus and sirolimus areas under the concentration-time curve was comparable to values in adults. AKT and 4EBP1 phosphorylation were inhibited at all dose levels, particularly after two courses.

Conclusion

Weekly intravenous temsirolimus is well tolerated in children with recurrent solid tumors, demonstrates antitumor activity, has pharmacokinetics similar to those in adults, and inhibits the mTOR signaling pathway in peripheral-blood mononuclear cells. Further studies are needed to define the optimal dose for use in combination with other antineoplastic agents in pediatric patients.

INTRODUCTION

Many human cancers are characterized by activation of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) protein, a serine threonine kinase involved in cell cycle regulation, angiogenesis, and apoptosis.1–3 The mTOR protein participates in two multiprotein complexes: mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1), which regulates growth via translational regulator p70S6 kinase and initiation factor 4E-BP1,4,5 and mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2), which influences cell survival via phosphorylation of AKTSer473.6

Temsirolimus is a potent and highly specific inhibitor of mTOR, as evidenced by its inhibition of phosphorylation of p70S6 kinase and 4E-BP1 in both in vitro and in vivo tumor model systems.7,8 It has antitumor activity in many human cancers, including various carcinomas (renal cell,9 breast,10 lung,11 pancreatic,12 prostate,13 and colon7) and hematologic malignancies14 (mantle-cell lymphoma,15 acute lymphocytic leukemia,16 and multiple myeloma17). Temsirolimus was the first mTOR inhibitor approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for use in oncology, where it is approved for the treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma.18 In adults, temsirolimus is well tolerated at intravenous doses ranging from 7.5 to 220 mg/m2 weekly,19 with rash and stomatitis being the most common associated toxicities. Pharmacokinetic analyses demonstrated that levels of temsirolimus achieved in the blood exceeded the concentrations required for inhibition of mTOR and tumor cell growth in vitro. Inhibition of mTOR activity has also been demonstrated in adults treated with temsirolimus by measurement of pS6 kinase in peripheral blood mononuclear cells.20 These observations led to dose selection for further studies in adults based not on the standard definition for maximum-tolerated dose (MTD), but on the dose required for biologic activity.

Several mTOR inhibitors have demonstrated significant antitumor activity in both in vivo and in vitro pediatric solid tumor models, including rhabdomyosarcoma, gliomas, and neuroblastoma,7,21–25 but no clinical trials of temsirolimus in pediatric patients have been reported. This phase I/II study was conducted in two parts and was designed to evaluate the safety and activity of intravenous temsirolimus in children with cancer. The phase I component was an ascending-dose safety study in pediatric patients with advanced solid tumors, and the results are reported herein. The phase II component was a preliminary evaluation of antitumor activity in pediatric patients with neuroblastoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, and high-grade glioma, and results are reported separately.26

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

Eligible patients were male or female patients 1 to 21 years of age. Eligibility and exclusion criteria are summarized in Table 1. Patients or their legal guardians provided written informed consent before study participation.

Table 1.

Protocol Eligibility Criteria

| Inclusion criteria |

| Age 1 to 21 years |

| Solid tumor recurrent or refractory to standard therapy or for which no standard treatment is available |

| Evaluable disease |

| ≥ 3 months since autologous or allogeneic bone marrow or stem-cell transplantation |

| ≥ 2 weeks since local radiotherapy |

| ≥ 3 months since craniospinal radiotherapy |

| ≥ 6 months since radiotherapy to whole abdomen or pelvis, whole lungs, > 25% of bone marrow reserve |

| ≥ 6 months since total-body irradiation |

| ≥ 3 weeks since chemotherapy (≥ 6 weeks for nitrosoureas) |

| ≥ 3 weeks since immunotherapy |

| ≥ 3 weeks since any prior investigational therapy (defined as treatment not approved for any indication) |

| ≥ 7 days since growth factors |

| Lansky (age 1 to 10 years) or Karnofsky (age 11 to 21 years) performance status ≥ 60% |

| Absolute neutrophil count ≥ 1,000/μL |

| Platelet count ≥ 75,000/μL (≥ 50,000/μL for patients with bone marrow involvement by tumor) |

| Hemoglobin ≥ 8 g/dL (red blood cell transfusion permitted if bone marrow involved by tumor) |

| Creatinine clearance (estimated by the Schwartz formula) ≥ lower limit for age or serum creatinine ≤ 2× normal for age |

| Bilirubin ≤ 1.5× institutional ULN |

| AST and ALT ≤ 3× institutional ULN |

| Life expectancy ≥ 2 months |

| Among patients of childbearing potential or with partners of childbearing potential, willingness to use a reliable birth control method during the study and for 12 weeks after its completion |

| Exclusion criteria |

| Known hepatitis B, hepatitis C, or HIV infection |

| Active infection or serious intercurrent illness |

| Pulmonary hypertension or pneumonitis |

| Any other major illness that, in the investigator's judgment, would substantially increase the risk associated with the patient's participation in the study |

| Concomitant therapy with any other investigational agent |

| Receiving enzyme-inducing anticonvulsants |

| Major surgery within 6 weeks before study entry |

| Pregnancy or lactation |

| Known hypersensitivity to any components in the temsirolimus infusion |

| Medical reasons for being unable to receive protocol-required premedication |

| Unwillingness or inability to comply with protocol guidelines |

Abbreviation: ULN, upper limit of normal.

Study Design

The institutional review boards of the three participating institutions approved the study protocol. This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice Guidelines.

Temsirolimus was supplied by Wyeth Pharmaceuticals (Philadelphia, PA) and was administered intravenously over 60 minutes once weekly (one course = 21 days). Premedication with intravenous diphenhydramine 1 mg/kg was given 30 minutes before the start of each temsirolimus infusion. The starting temsirolimus dose was 10 mg/m2, with escalation planned to 25, 75, and 150 mg/m2 based on experience in adult subjects receiving doses ranging from 7.5 to 220 mg/m2.19 A minimum of three patients assessable for toxicity were to be treated at each dose level. If a dose-limiting toxicity (DLT) was not observed among the first three assessable patients treated at a given dose level, then the dose was escalated. If one of three patients experienced a DLT, then an additional three patients were treated at that dose level. In the absence of further DLTs, the dose was escalated. The MTD was defined as the dose level immediately below that at which two more patients experienced DLTs during the first course of treatment. Six assessable patients were to be treated at the MTD. There was no intra-patient dose escalation. Patients who experienced a DLT could continue treatment at the next lower dose level after resolution of toxicity; a further DLT prompted removal from the study. Those without DLTs could continue therapy until disease progression occurred.

Toxicity was graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 3.0. Only toxicity during the first course of treatment was used to determine the MTD. Grade 4 thrombocytopenia or neutropenia of more than 7 days in duration was classified as a hematologic DLT. Nonhematologic DLTs included all grade 3 or 4 nonhematologic toxicities, except for asymptomatic grade 3 electrolytes, grade 3 nausea/vomiting/diarrhea responsive to medical therapy, grade 3 AST or ALT with recovery to grade 1 before the next course, and serum triglycerides less than 1,500 mg/dL with recovery to baseline before the next course. Delay in treatment for more than 2 weeks because of an unresolved temsirolimus-related toxicity was also considered dose limiting.

Pretreatment evaluations included a medical history, physical examination, performance status assessment, echocardiogram, complete blood count with differential (CBC), coagulation profile, serum electrolytes, renal and liver function tests, cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein, high-density lipoprotein, triglycerides, and urinalysis. During treatment, patients were seen weekly for a physical examination, performance status assessment, and CBC; serum chemistries and liver function tests were obtained every 2 weeks. The protocol cautioned against using CYP3A4 inducers or inhibitors and drugs that are CYP2D6 substrates due to potential pharmacokinetic interactions.

Disease evaluations were performed at baseline and after every two courses thereafter. Tumor response was evaluated using the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST),27 excepting patients with neuroblastoma who were evaluated by the International Neuroblastoma Response Criteria.28 To be assigned a status of complete response, very good partial response, or partial response, the response must have been confirmed by repeated evaluation ≥ 4 weeks after the initial assessment.

Pharmacokinetic Studies

Pharmacokinetic studies to measure temsirolimus and sirolimus levels were required during the first two courses. Whole-blood samples (2 mL) were collected in an EDTA-treated tube before temsirolimus administration and at 1, 2, 6, 24, and 168 hours after administration. During course 2, samples were also obtained at 72 and 96 hours after drug administration. Samples were mixed, transferred into a separate polypropylene tube, and stored at −70°C until shipped for processing. Temsirolimus and sirolimus were simultaneously measured using a validated liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry method with an internal standard. Mean intra-day and inter-day variability of temsirolimus and sirolimus quality control samples was 15.1% or less in both the low-range and high-range assays.

Pharmacokinetic parameters, including peak observed concentration (Cmax), time to Cmax (tmax), area under the concentration-time curve to the last measurable time point (AUCT) and to infinity (AUC), half-life (t), clearance (CL), steady-state volume of distribution (Vdss), sum of temsirolimus plus sirolimus AUCs (AUCsum), and ratio of sirolimus-to-temsirolimus AUCs (AUCratio), were derived from the concentration-time profiles using a noncompartmental analysis method. For sirolimus, values of CL and Vdss were reported as apparent measures and were normalized by the unknown fraction of dose metabolized (fm).

Pharmacodynamic Studies

Required pharmacodynamic studies were performed using whole-blood (5 mL) specimens obtained before administration of temsirolimus and at 1, 2, 8, 24, and 168 hours (course 1) and at 1, 24, 72, 96, 168 hours, and days 16 through 21 (course 2) after treatment. CPT tubes (Becton-Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) were used for one-step blood collection and separation of peripheral-blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). Total protein was then extracted from each PBMC pellet and stored at −80°C until analyzed. Levels of pS6Ser235/236, pAKTSer473 and p4EBP1Thr37/46 expression in PBMC isolates at each time point were determined using standard Western blotting techniques.29 The levels of detected phosphoproteins were recorded relative to the corresponding total protein concentration in each sample. Actin was used as a loading and transfer control in each Western blot analysis.

RESULTS

Nineteen patients were enrolled onto the study. Table 2 shows the characteristics of these patients, who were treated on four dose levels: 10 mg/m2 (n = 4), 25 mg/m2 (n = 5), 75 mg/m2 (n = 3), and 150 mg/m2 (n = 7). At all dose levels, the median number of temsirolimus doses per patient was six (range, two to 79 doses). The median relative dose-intensity (mg/m2/wk administered divided by mg/m2/wk expected) ranged from 0.96 to 1.00 for each of the four dose levels studied.

Table 2.

Baseline Patient Characteristics

| Characteristic | Patients (N = 19) |

|

|---|---|---|

| No. | % | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 11 | 58 |

| Female | 8 | 42 |

| Age, years | ||

| Median | 11 | |

| Range | 4-21 | |

| Race | ||

| White | 13 | 68 |

| Black | 3 | 16 |

| Other | 3 | 16 |

| Ethnic origin | ||

| Non-Hispanic and non-Latino | 16 | 84 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 3 | 16 |

| Body-surface area, m2 | ||

| Median | 1.38 | |

| Range | 0.65-2.00 | |

| Performance status* | ||

| 100 | 5 | |

| 90 | 9 | |

| 80 | 1 | |

| 70 | 1 | |

| 60 | 2 | |

| Missing† | 1 | |

| Disease type | ||

| Solid tumors | 11 | |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | 3 | |

| Osteosarcoma | 3 | |

| Neuroblastoma | 2 | |

| Wilms tumor | 1 | |

| Germ cell tumor | 1 | |

| Adrenocortical carcinoma | 1 | |

| Brain tumors | 8 | |

| Medulloblastoma | 2 | |

| Ependymoma | 2 | |

| Primitive neuroectodermal tumor | 1 | |

| Atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor | 1 | |

| Glioblastoma multiforme | 1 | |

| Pontine glioma | 1 | |

| No. of prior chemotherapy regimens | ||

| 1 | 2 | |

| 2 | 3 | |

| 3 | 7 | |

| > 3 | 7 | |

| Prior radiotherapy | ||

| Yes | 13 | |

| No | 6 | |

Lansky performance status for patients 1 through 10 years of age; Karnofsky performance status for patients 11 through 21 years of age.

Although missing in the clinical database, confirmed locally by the investigator as 100%.

Regimen Toxicity

Table 3 shows the DLTs observed at each dose level during the first course of treatment. Eighteen of the 19 patients received the first three doses of temsirolimus and were therefore fully assessable for DLTs. The remaining patient (at 25 mg/m2) discontinued therapy on day 15 of course 1 before the third dose of temsirolimus as a result of disease progression. One protocol-defined DLT was observed in a patient treated at the 150 mg/m2 dose level: grade 3 anorexia. A grade 3 prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time was also observed. However, this patient had a preexisting grade 3 prolonged activated partial thromboplastin of uncertain etiology at study entry that was asymptomatic and not associated with any clinical consequences; therefore, it was ultimately judged not to meet the criteria for a DLT. Thus the 150-mg/m2 dose level was determined to be tolerable.

Table 3.

Dose-Escalation Results and Experience

| Cohort | Dose (mg/m2) | No. of Patients | No. of Patients With DLTs (course 1) | Other Clinically Significant Safety Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10 | 4 | 0 | — |

| 2 | 25 | 5 | 0 | — |

| 3 | 75 | 3 | 0 | — |

| 4 | 150 | 7 | 1 (grade 3 anorexia) | 1 patient with grade 3 aPTT prolonged; 1 patient with grade 4 thrombocytopenia lasting 6 days; 1 patient with grade 2 vomiting lasting 3 days |

Abbreviations: aPTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; DLT, dose-limiting toxicity.

At least one toxicity potentially attributable to temsirolimus occurred in each of the patients enrolled on the study at some time during their treatment (Table 4). The most common treatment-related adverse events were anemia, leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia (10 patients, 53% each); neutropenia (nine patients, 47%); and anorexia and hyperlipidemia (eight patients, 42% each). Nine patients (47%), four of whom were in the 150 mg/m2 cohort, experienced grade 3 or 4 treatment-related adverse events. Grade 3 and 4 toxicities potentially related to temsirolimus therapy were uncommon after course 1. Among 16 patients who began course 2, no patient discontinued temsirolimus therapy as a result of intolerable toxicity. One patient in the 25-mg/m2 cohort had one dose reduction, and one patient in the 150-mg/m2 cohort required one dose reduction.

Table 4.

Toxicities Possibly or Probably Related to Treatment in Any Course (all grades* that occurred in ≥ 25% of patients)

| Adverse Event† | Temsirolimus Dose (mg/m2) |

|||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 (n = 4) |

25 (n = 5) |

75 (n = 3) |

150 (n = 7) |

All Patients (n = 19) |

||||||||||||||||

| All Grades |

Grade 3-4 |

All Grades |

Grade 3-4 |

All Grades |

Grade 3-4 |

All Grades |

Grade 3-4 |

All Grades |

Grade 3-4 |

|||||||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Any | 4 | 100 | 1 | 25 | 5 | 100 | 2 | 40 | 3 | 100 | 2 | 67 | 7 | 100 | 4 | 57 | 19 | 100 | 9 | 47 |

| Anemia | 2 | 50 | 1 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 67 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 86 | 1 | 14 | 10 | 53 | 2 | 11 |

| Leukopenia | 1 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 20 | 1 | 20 | 3 | 100 | 1 | 33 | 5 | 71 | 1 | 14 | 10 | 53 | 3 | 16 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 1 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 57 | 2 | 29 | 10 | 53 | 2 | 11 |

| Neutropenia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 40 | 2 | 40 | 3 | 100 | 2 | 67 | 4 | 57 | 1 | 14 | 9 | 47 | 5 | 26 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 60 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 67 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 29 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 42 | 0 | 0 |

| Anorexia | 1 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 33 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 86 | 1 | 14 | 8 | 42 | 1 | 5 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 33 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 57 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 37 | 0 | 0 |

| Hypokalemia | 1 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 67 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 43 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 37 | 0 | 0 |

| Hypoproteinemia | 2 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 33 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 57 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 37 | 0 | 0 |

| AST increased | 2 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 33 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 29 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 37 | 0 | 0 |

| Vomiting | 1 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 33 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 57 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 37 | 0 | 0 |

| Mucositis | 1 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 33 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 43 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 32 | 0 | 0 |

| Rash | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 33 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 57 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 32 | 0 | 0 |

| Hyperglycemia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 60 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 29 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 26 | 0 | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 1 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 33 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 29 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 26 | 0 | 0 |

| Nausea | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 67 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 29 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 26 | 0 | 0 |

| Asthenia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 57 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 26 | 0 | 0 |

Grades are according to National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 3.0.

Each adverse event was counted once (any course, highest grade) for each patient.

Tumor Responses

Thirteen of the 19 patients completed at least two courses of therapy and were evaluable for tumor response: complete response (CR; n = 1), stable disease (SD; n = 5), and progressive disease (n = 7). The CR occurred in a child with multiply recurrent neuroblastoma involving the left axilla and xiphoid process (both sites identified by metaiodobenzylguanidine scan) who received treatment at the first dose level, 10 mg/m2. Preceding therapy included all known active agents in neuroblastoma, two autologous stem-cell transplants, and other investigational agents. A CR was noted after course 4 and was maintained for four additional courses, at which time new distant metastases were identified (total time on therapy, 253 days). Three patients with SD remained on treatment for more than 4 months: ependymoma (569 days on therapy), germ cell tumor (177 days on therapy), and adrenocortical carcinoma (133 days on therapy).

Of the six patients who did not complete two courses of therapy, two had SD, two had progressive disease, and two were not evaluated for response. One patient discontinued owing to an adverse event (grade 3 thrombocytopenia), one because of symptomatic deterioration, two to pursue other therapy, and two because of disease progression.

Pharmacokinetics

Pharmacokinetic data were available from all 19 patients (Table 5). Drug concentrations seemed to decline in a polyexponential fashion. Cmax, AUC, CL, and AUCsum increased with dose. In course 1 after the first dose, median Cmax ranged from 316 ng/mL (10 mg/m2 dose) to 2,800 ng/mL (150 mg/m2 dose) and was observed at the end of the infusion. One patient who received the 150-mg/m2 dose exhibited an unusually high Cmax value (50,400 ng/mL) and experienced grade 4 thrombocytopenia. This measure was limited to parent drug only, did not reflect in commensurately high values at later time points, and did not seem to explain the platelet attenuation observed in this patient. Otherwise, variabilities in Cmax were moderate (coefficient of variation ≤ 43% for all treatment groups) and no other correlations were noted between pharmacokinetic parameters and toxicity. The AUC and CL varied more than Cmax, presumably because of the paucity of measures between the 96- and 168-hour time points and the multicompartmental nature of the profiles. Cmax and AUC values did not differ significantly between courses 1 and 2 (data not shown). Median t ranged from 10.8 to 24.0 hours and tended to increase with increasing dose.

Table 5.

Summary of Course 1 Temsirolimus Pharmacokinetic Findings

| Agent | Dose Level (mg/m2) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 (n = 4) |

25 (n = 5) |

75 (n = 3) |

150 (n = 7) |

|||||

| Median | Range | Median | Range | Median | Range | Median | Range | |

| Temsirolimus | ||||||||

| Cmax, ng/mL | 316 | 190–407 | 448 | 353–726 | 442 | 369–630 | 2,800 | 1,200–50,400 |

| tmax, h | 1.0 | 0.9–1.3 | 1.1 | 1.0–1.2 | 1.4 | 1.08–1.5 | 1.0 | 1.0–1.6 |

| t, h | 10.8 | 9.9–11.1 | 16.2 | 9.9–23.1 | 24 | 24–24 | 21.4 | 4.8–29.5 |

| AUC, h · ng/mL | 1,670 | 1,290–3,360 | 3,570 | 2,070–9,330 | 2,810 | 2,810–2,810 | 5,190 | 3,220–38,300 |

| CL, L/h | 5.8 | 4.1–12.4 | 8.9 | 4.3–19.4 | 38.1 | 38.1–38.1 | 47.7 | 3–93.1 |

| Vdss, L | 77.7 | 51.1–134 | 194 | 133–233 | 783 | 783–783 | 255 | 8.4–1,530 |

| Sirolimus | ||||||||

| Cmax, ng/mL | 52.4 | 29.6–66.4 | 45.1 | 35.2–114 | 104 | 69.4–152 | 247 | 106–451 |

| tmax, h | 2.0 | 1.0–2.2 | 6.0 | 1.0–25.3 | 6.3 | 5.3–6.5 | 2 | 1–5.5 |

| t, h | 43.7 | 40.6–60.2 | 43.9 | 38.1–49.7 | 42.0 | 39.2–44.4 | 36.6 | 31.6–58.4 |

| AUC, h · ng/mL | 2,560 | 1,840–4,900 | 4,520 | 3,050–5,990 | 7,670 | 3,900–10,700 | 8,660 | 7,220–15,900 |

| CL/fm, L/h | 3.9 | 3.4–6.6 | 9.9 | 6.7–13.1 | 14 | 10.6–17.5 | 18.9 | 12–34 |

| Vdss/fm, L | 290 | 198–432 | 683 | 377–990 | 665 | 146–924 | 994 | 595–2,880 |

| AUCsum, ng Eq · h/mL | 4,955 | 3,670–6,270 | 10,218 | 5,120–15,315 | 10,480 | 10,480–10,480 | 14,898 | 12,031–19,492 |

| AUCratio | 1.4 | 0.8–3.6 | 1.1 | 0.6–1.5 | 2.7 | 2.7–2.7 | 2.7 | 1.2–4.4 |

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the concentration-time curve; AUCratio, ratio of sirolimus-to-temsirolimus AUCs; AUCsum, algebraic sum of temsirolimus plus sirolimus AUCs, uncorrected for difference in molecular weight; CL, clearance; Cmax, maximum concentration; fm, unknown fraction metabolized; tmax, time to Cmax; t, half-life; Vdss, steady-state volume of distribution.

The sirolimus metabolite was rapidly formed, with a median tmax ranging from 2.0 to 6.3 hours. Sirolimus AUC and AUCsum increased less than proportionally with dose. Exposure did not vary substantially between courses 1 and 2. The median t ranged from 36.6 to 43.9 hours.

Pharmacodynamics

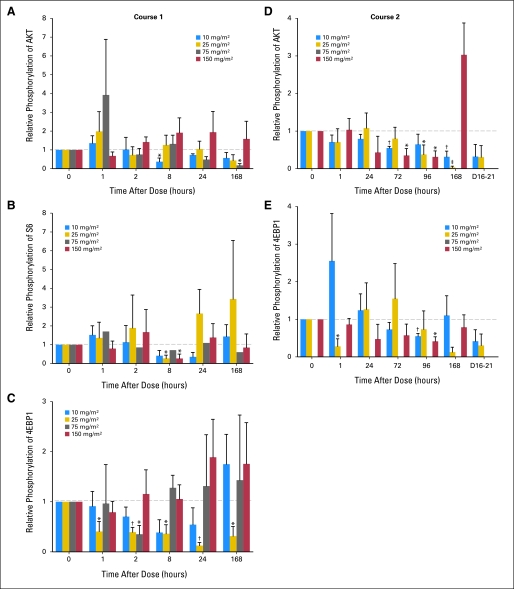

In total, 186 PBMC samples adequate for Western blot analysis were obtained from 17 patients. These included four patients treated with 10 mg/m2 of temsirolimus, four with 25 mg/m2, three with 75 mg/m2, and six with 150 mg/m2. Marked inter-patient variability was observed in PBMC content of phosphorylated (p) AKT, pS6, and 4EBP1 at all dose levels during course 1; however, reductions in all three phospho-proteins were detectable from 2 hours after temsirolimus dosing (Fig 1). Decreases in pAKT, pS6, and p4EBP1 were most notable at 168, 8, and 2 hours postdose, respectively, although numbers were too small to determine whether these represented true peaks in measured biologic response. An apparent late paradoxical increase in all three phospho-proteins was seen in the PBMC isolated from patients treated with 150 mg/m2, although this did not reach significance. Adequate material was available from course 2 PBMC for Western blotting of pAKT and p4EBP1 only. These data revealed a more profound and consistent inhibition of protein phosphorylation.

Fig 1.

Relative phosphorylation of key signal proteins in the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway in peripheral-blood mononuclear cells of trial patients. Total level of each phosphorylated protein was normalized to the total level of the corresponding total protein by Western blot analysis. Each graph reports the level of normalized phosphorylated protein relative to time 0 postdose. Graphs report results for (A) Akt, (B) S6, and (C) 4EBP1 during course 1, and (D) AKT and (E) 4EBP1 during course 2. *P < .05. †P < .005. ‡P < .0005 relative to time 0.

Despite the fact that Cmax and AUC increased with increasing dose administered, there was no evidence of a relationship between either the temsirolimus dose administered or the Cmax or AUC achieved and relative phosphorylation of AKT, p70S6, or 4EBP1. Similarly, there was no evidence that patients who experienced a complete tumor response or prolonged SD received higher temsirolimus doses, achieved higher Cmax or AUC values, or had lower relative phosphorylation of AKT, p70S6, or 4EBP1 than did the other patients.

DISCUSSION

This phase I study of intravenous temsirolimus demonstrated that the highest dose level tested, 150 mg/m2, was tolerable in pediatric patients with recurrent and refractory solid tumors. At this dose level, one patient experienced dose-limiting anorexia. Otherwise, toxicities were mild and grade 3 and 4 toxicities were virtually all hematologic. The most common nonhematologic toxicities were anorexia and hyperlipidemia. Drug-related pneumonitis, which has been observed in adult patients treated with temsirolimus,30 was not observed in this study. As expected from the mild toxicity profile, the median delivered dose-intensity exceeded 95% for all dose levels tested. The toxicity of temsirolimus was similar to that observed in adult clinical trials and in a pediatric trial of another mTOR inhibitor, everolimus.19,29–34 Among the 13 patients evaluable for tumor response after six weekly doses of temsirolimus, one patient with neuroblastoma had a CR that was sustained for an additional 12 weeks and five patients had SD, three of whom remained on study for at least 4 months. These findings suggest that temsirolimus may have a role in the treatment of pediatric solid tumors, although further studies are needed to more precisely assess its spectrum and degree of activity.

We observed that temsirolimus AUCsum in pediatric patients is comparable to respective values in adults for similar bracketed doses.19 The greater exposure to parent drug in pediatric patients was balanced by a shorter half-life of the sirolimus metabolite (median t of 36.6 to 43.9 hours) and lower AUCs in pediatric patients compared with a t of 60.8 hours and commensurate higher sirolimus AUC in adult patients with solid tumors. Interestingly, the only patient in our study who developed grade 4 thrombocytopenia had an unusually hightemsirolimus Cmax value; however, surrounding concentration measures for temsirolimus or sirolimus for this subject do not support a causal relationship. Previously, severity of thrombocytopenia was positively correlated with temsirolimus Cmax values in adults treated once-daily for 5 days every 2 weeks.33

In this study, we show that temsirolimus can significantly inhibit phosphorylation of AKT and 4EBP1 in PBMCs. Notably, inhibition was observed at doses as low as 10 mg/m2, and there did not appear to be a relationship between the temsirolimus dose administered and inhibition of AKT/4EBP1 phosphorylation, nor between temsirolimus serum levels achieved and inhibition of AKT/4EBP1 phosphorylation. These findings are consistent with those of a study in adults that documented mTOR downstream target inhibition after fixed doses as low as 25 mg and found no relationship between the administered dose of temsirolimus and the degree of inhibition.18 In our study, pediatric patients who experienced a favorable tumor response (CR or prolonged SD) did not have lower relative phosphorylation of AKT, pS6, or 4EBP1 in their PBMCs. It is unclear whether this is because even mild inhibition of the mTOR pathway is sufficient in sensitive tumors to elicit a response or because the small number of patients included in this study prevented a clear association to be drawn between mTOR pathway inhibition in nonmalignant cells and tumor response. However, a lack of relationship between mTOR pathway protein inhibition and tumor response has also been documented in adult patients with glioblastoma multiforme.31 Further studies evaluating the relationship between administered dose and biologic effect are needed to confirm the preliminary findings in this study.

To summarize, temsirolimus seems to be a good candidate for further development in pediatric oncology as a result of its favorable safety profile and preclinical and clinical evidence of its activity in pediatric solid tumors.7,25,35,36 Dose selection for future trials is challenging because there is not a clear relationship between either dose administered or serum levels achieved and the degree of inhibition of mTOR downstream pathway proteins in surrogate tissues, nor is there a clear relationship between mTOR pathway inhibition and tumor response. Further studies are needed to clarify these issues. Preclinical data and findings from the phase I component of this study led to the phase II component evaluating temsirolimus in pediatric neuroblastoma,36 rhabdomyosarcoma,7,25,37 and high-grade glioma,32,35 the results of which are presented separately. Future pediatric studies should explore combining temsirolimus with standard chemotherapy regimens14 and with other novel agents that target mTOR-related pathways, such as insulin-like growth factor–1 receptor antibodies and epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors.21,38–41

Acknowledgment

We thank all of the patients and their families, research nurses and clinical personnel, study coordinators, and operations staff who participated in this study. We also thank Peter Houghton, PhD, of Nationwide Children's Research Institute for his contributions to the study design; Becker Hewes, Brooke Esteves, and Lisa Speicher of Wyeth for their technical and administrative assistance; and Inga Luckett and Radhika Thiruvenkatam of the St Jude Children's Research Hospital Molecular Clinical Trials Core for their technical assistance. We also thank Christine Blood, PhD, of Peloton Advantage for medical writing assistance and Revathi Ananthakrishnan, PhD, of inVentiv Clinical Solutions, Cambridge, MA, for statistcal analyses, which were funded by Pfizer.

Footnotes

Supported in part by Wyeth Research (which was acquired by Pfizer in October 2009) through grants to S.L.S., S.A.G., T.A.V., V.M.S., and R.J.G.; by Solid Tumor Program Project Grant No. CA23099 to S.L.S., V.M.S., and R.J.G.; by Cancer Center Support CORE Grant No. P30 CA 21765 from the National Cancer Institute to S.L.S., V.M.S., and R.J.G.; and by funding from the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities to S.L.S., V.M.S., and R.J.G. No author received an honorarium or other form of financial support related to the development of this manuscript.

Presented in part at the Pediatric Academic Societies Annual Meeting, May 5-8, 2007, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

Clinical trial information can be found for the following: NCT00106353.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Although all authors completed the disclosure declaration, the following author(s) indicated a financial or other interest that is relevant to the subject matter under consideration in this article. Certain relationships marked with a “U” are those for which no compensation was received; those relationships marked with a “C” were compensated. For a detailed description of the disclosure categories, or for more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to the Author Disclosure Declaration and the Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest section in Information for Contributors.

Employment or Leadership Position: Jill Clancy, inVentiv Clinical Solutions (C); Anna Berkenblit, Wyeth/Pfizer (C); Mizue Krygowski, Wyeth/Pfizer (C); Joseph P. Boni, Wyeth/Pfizer (C) Consultant or Advisory Role: David J. Greenblatt, Pfizer (C); Revathi Ananthakrishnan, inVentiv Clinical Solutions (C) Stock Ownership: Anna Berkenblit, Pfizer; Mizue Krygowski, Pfizer; Joseph P. Boni, Pfizer Honoraria: None Research Funding: None Expert Testimony: None Other Remuneration: None

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Sheri L. Spunt, Stephan A. Grupp, Terry A. Vik, Victor M. Santana, Joseph P. Boni, Richard J. Gilbertson

Provision of study materials or patients: Sheri L. Spunt, Victor M. Santana

Collection and assembly of data: Sheri L. Spunt, Stephan A. Grupp, Terry A. Vik, Anna Berkenblit, Richard J. Gilbertson

Data analysis and interpretation: Sheri L. Spunt, Stephan A. Grupp, Terry A. Vik, David J. Greenblatt, Jill Clancy, Anna Berkenblit, Mizue Krygowski, Revathi Ananthakrishnan, Joseph P. Boni, Richard J. Gilbertson

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

REFERENCES

- 1.Bjornsti MA, Houghton PJ. The TOR pathway: A target for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:335–348. doi: 10.1038/nrc1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dancey JE. Therapeutic targets: MTOR and related pathways. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5:1065–1073. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.9.3175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meric-Bernstam F, Gonzalez-Angulo AM. Targeting the mTOR signaling network for cancer therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2278–2287. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.0766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aoki M, Blazek E, Vogt PK. A role of the kinase mTOR in cellular transformation induced by the oncoproteins P3k and Akt. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:136–141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011528498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hara K, Yonezawa K, Kozlowski MT, et al. Regulation of eIF-4E BP1 phosphorylation by mTOR. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:26457–26463. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.42.26457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sarbassov DD, Guertin DA, Ali SM, et al. Phosphorylation and regulation of Akt/PKB by the rictor-mTOR complex. Science. 2005;307:1098–1101. doi: 10.1126/science.1106148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dudkin L, Dilling MB, Cheshire PJ, et al. Biochemical correlates of mTOR inhibition by the rapamycin ester CCI-779 and tumor growth inhibition. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:1758–1764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Podsypanina K, Lee RT, Politis C, et al. An inhibitor of mTOR reduces neoplasia and normalizes p70/S6 kinase activity in Pten+/- mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:10320–10325. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171060098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas GV, Tran C, Mellinghoff IK, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor determines sensitivity to inhibitors of mTOR in kidney cancer. Nat Med. 2006;12:122–127. doi: 10.1038/nm1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu K, Toral-Barza L, Discafani C, et al. MTOR, a novel target in breast cancer: The effect of CCI-779, an mTOR inhibitor, in preclinical models of breast cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2001;8:249–258. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0080249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu C, Wangpaichitr M, Feun L, et al. Overcoming cisplatin resistance by mTOR inhibitor in lung cancer. Mol Cancer. 2005;4:25. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-4-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asano T, Yao Y, Zhu J, et al. The rapamycin analog CCI-779 is a potent inhibitor of pancreatic cancer cell proliferation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;331:295–302. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu L, Birle DC, Tannock IF. Effects of the mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor CCI-779 used alone or with chemotherapy on human prostate cancer cells and xenografts. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2825–2831. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teachey DT, Grupp SA, Brown VI. Mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors and their potential role in therapy in leukaemia and other haematological malignancies. Br J Haematol. 2009;145:569–580. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07657.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yazbeck VY, Buglio D, Georgakis GV, et al. Temsirolimus downregulates p21 without altering cyclin D1 expression and induces autophagy and synergizes with vorinostat in mantle cell lymphoma. Exp Hematol. 2008;36:443–450. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teachey DT, Obzut DA, Cooperman J, et al. The mTOR inhibitor CCI-779 induces apoptosis and inhibits growth in preclinical models of primary adult human ALL. Blood. 2006;107:1149–1155. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi Y, Gera J, Hu L, et al. Enhanced sensitivity of multiple myeloma cells containing PTEN mutations to CCI-779. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5027–5034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hudes G, Carducci M, Tomczak P, et al. Temsirolimus, interferon alfa, or both for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2271–2281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raymond E, Alexandre J, Faivre S, et al. Safety and pharmacokinetics of escalated doses of weekly intravenous infusion of CCI-779, a novel mTOR inhibitor, in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2336–2347. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peralba JM, DeGraffenried L, Friedrichs W, et al. Pharmacodynamic evaluation of CCI-779, an inhibitor of mTOR, in cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:2887–2892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coulter DW, Blatt J, D'Ercole AJ, et al. IGF-I receptor inhibition combined with rapamycin or temsirolimus inhibits neuroblastoma cell growth. Anticancer Res. 2008;28:1509–1516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dilling MB, Dias P, Shapiro DN, et al. Rapamycin selectively inhibits the growth of childhood rhabdomyosarcoma cells through inhibition of signaling via the type I insulin-like growth factor receptor. Cancer Res. 1994;54:903–907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geoerger B, Kerr K, Tang CB, et al. Antitumor activity of the rapamycin analog CCI-779 in human primitive neuroectodermal tumor/medulloblastoma models as single agent and in combination chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1527–1532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hosoi H, Dilling MB, Liu LN, et al. Studies on the mechanism of resistance to rapamycin in human cancer cells. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;54:815–824. doi: 10.1124/mol.54.5.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wan X, Shen N, Mendoza A, et al. CCI-779 inhibits rhabdomyosarcoma xenograft growth by an antiangiogenic mechanism linked to the targeting of mTOR/Hif-1alpha/VEGF signaling. Neoplasia. 2006;8:394–401. doi: 10.1593/neo.05820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geoerger B, Kieran MW, Grupp S, et al. Phase 2 study of temsirolimus in children with high-grade glioma, neurosarcoma, and rhabdomyosarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(suppl):688s. abstr 9541. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brodeur GM, Pritchard J, Berthold F, et al. Revisions of the international criteria for neuroblastoma diagnosis, staging, and response to treatment. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:1466–1477. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.8.1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fouladi M, Laningham F, Wu J, et al. Phase I study of everolimus in pediatric patients with refractory solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4806–4812. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.4017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Atkins MB, Hidalgo M, Stadler WM, et al. Randomized phase II study of multiple dose levels of CCI-779, a novel mammalian target of rapamycin kinase inhibitor, in patients with advanced refractory renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:909–918. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chan S, Scheulen ME, Johnston S, et al. Phase II study of temsirolimus (CCI-779), a novel inhibitor of mTOR, in heavily pretreated patients with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5314–5322. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.66.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Galanis E, Buckner JC, Maurer MJ, et al. Phase II trial of temsirolimus (CCI-779) in recurrent glioblastoma multiforme: A North Central Cancer Treatment Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5294–5304. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.23.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hidalgo M, Buckner JC, Erlichman C, et al. A phase I and pharmacokinetic study of temsirolimus (CCI-779) administered intravenously daily for 5 days every 2 weeks to patients with advanced cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:5755–5763. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Witzig TE, Geyer SM, Ghobrial I, et al. Phase II trial of single-agent temsirolimus (CCI-779) for relapsed mantle cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5347–5356. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.13.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hu X, Pandolfi PP, Li Y, et al. MTOR promotes survival and astrocytic characteristics induced by Pten/AKT signaling in glioblastoma. Neoplasia. 2005;7:356–368. doi: 10.1593/neo.04595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Misawa A, Hosoi H, Tsuchiya K, et al. Rapamycin inhibits proliferation of human neuroblastoma cells without suppression of MycN. Int J Cancer. 2003;104:233–237. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hosoi H, Dilling MB, Shikata T, et al. Rapamycin causes poorly reversible inhibition of mTOR and induces p53-independent apoptosis in human rhabdomyosarcoma cells. Cancer Res. 1999;59:886–894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cao L, Yu Y, Darko I, et al. Addiction to elevated insulin-like growth factor I receptor and initial modulation of the AKT pathway define the responsiveness of rhabdomyosarcoma to the targeting antibody. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8039–8048. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Doherty L, Gigas DC, Kesari S, et al. Pilot study of the combination of EGFR and mTOR inhibitors in recurrent malignant gliomas. Neurology. 2006;67:156–158. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000223844.77636.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gallicchio MA, van Sinderen M, Bach LA. Insulin-like growth factor binding protein-6 and CCI-779, an ester analogue of rapamycin, additively inhibit rhabdomyosarcoma growth. Horm Metab Res. 2003;35:822–827. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-814153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kurmasheva RT, Dudkin L, Billups C, et al. The insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor-targeting antibody, CP-751,871, suppresses tumor-derived VEGF and synergizes with rapamycin in models of childhood sarcoma. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7662–7671. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]