You cannot fight against the future. Time is on our side. The great social forces which move onwards in their might and majesty, and which the tumult of our debates does not for a moment impede or disturb - those great social forces are against you; they are marshalled on our side; and the banner which we now carry in this fight, though perhaps at some moment it may droop over our sinking heads, yet it soon again will float in the eye of heaven, and it will be borne... perhaps not to an easy, but to a certain and to a not distant victory.

W E Gladstone, 1866.

For supporters of open access publishing, these are heady times. Over the past year the campaign to make the full text of original research articles freely available via the world wide web has made rapid progress (box).

Its most tangible sign was the publication of PLoS Biology, which is favourably reviewed elsewhere in the journal (p 56).1 It's the first foray into publishing by the pressure group the Public Library of Science, which aims “to catalyze a revolution in scientific publishing by providing a compelling demonstration of the value and feasibility of open-access publication.” If its revolution succeeds “everyone who has access to a computer and an Internet connection will be a keystroke away from our living treasury of scientific and medical knowledge.”2

While PLoS Biology regards Cell, Nature, and Science as its natural competitors, PLoS Medicine, scheduled for publication this autumn, will be going head to head with general medical journals.

The Public Library of Science charges authors $1500 (£851; €1207) per accepted article to cover the costs of processing the articles (peer review and technical editing) and electronic distribution. The article is then made freely available from its own website as well as PubMed Central, the National Library of Medicine's free digital archive of journal literature in the life sciences.

This model was pioneered among medical publishers by the Journal of Clinical Investigation and BioMed Central, which publishes more than 107 online journals. While it is commonly labelled “author pays” to differentiate it from the traditional “reader pays” model of journal subscription, it's mostly the authors' funders who pick up the bill.3 In fact “readers” are also mostly academic institutions. So the same institutions may pay with open access but the beauty for them will be that they should pay less as well as achieve universal access. The “losers” will be publishers, particularly commercial publishers such as Reed Elsevier.

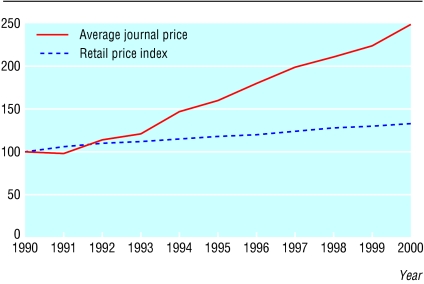

The main driver for this switch has been unsustainable developments in the publishing industry. Over recent years, journal prices have increased far faster than the underlying rate of inflation (figure). As their budgets have failed to keep up, cash strapped librarians have cut back on subscriptions. To compensate for lost profits, publishers have increased their prices even further—a death spiral that few traditional publishers seem ready to escape.

Figure 1.

Medical journal prices v inflation (retail price index) 1990-2000 (1990=100). Adapted from Table 3.2, Economic analysis of scientific research publishing

The result has been that medical research, mainly funded by governments, universities, and charitable foundations, has been available only at higher and higher costs to potential users. “Taxpayers have already paid for this research—why should they pay for it again?” was the refrain taken up by America's newspapers last summer.

This double payment makes scientific publishing a highly lucrative business, worth $7bn a year. The market leader, Reed Elsevier, makes annual profits of $290m with margins of nearly 40% on its core journal business.4,5 On the back of a detailed economic analysis,6 the United Kingdom's leading biomedical research charity, the Wellcome Trust, concluded that “the publishing of scientific research does not operate in the interests of scientists and the public, but is instead dominated by a commercial market intent on improving its market position.”

Those who contribute most of the value to the process have begun to mutiny. Last October two scientists at University of California San Francisco called for a boycott of six molecular biology journals, accusing the publisher, Reed Elsevier, of charging exorbitant fees for access. The academic senate at University of California Santa Cruz has called on tenured members to give “serious and careful consideration to cutting their ties with Elsevier,” unless Elsevier drops its prices. This would include no longer submitting papers to Elsevier journals, refusing to referee the submissions of others, and giving up editorial posts.

What has emboldened these rebels is their knowledge that the internet offers a route out of this impasse. In the paper world, each extra copy of an article or a journal comes at cost—for paper, print, binding, and postage. By comparison, on the web the distribution costs are virtually zero (for bmj.com they amount to about 0.3 pence/article). If the fixed costs of article processing could be recovered on input to the system then the output could be made available free to everyone who was interested.

For this switch to occur, funding agencies would need to become directly involved in funding the processing of research articles as well as the research activity itself.6 Large funding bodies that have done the sums estimate that picking up the costs of open access publishing (at the Public Library of Science's rate of $1500/article) would increase their research grants by only a few per cent.

Light the blue touchpaper

December 2002 The Public Library of Science receives a $9 million grant from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation for open access publishing and announces its first two open access journals

March 2003 NHS announces membership deal with BioMed Central

June 2003 Joint Information Systems Committee (a committee of UK further and higher education funding bodies) buys institutional memberships of BioMed Central for all 180 universities in the UK

June 2003 Release of Bethesda Statement on Open Access Publishing, with suggestions as to what institutions, funding agencies, libraries, publishers, and scientists could do to bring it about

June 2003 Martin Sabo introduces the Public Access to Science Act into Congress, which would exclude from copyright protection works resulting from scientific research substantially funded by the US government

September 2003 Howard Hughes Medical Institute tells grantees that the institute will cover article processing charges for open access

October 2003 Publication of a position statement by the Wellcome Trust in support of open access publishing

October 2003 Public Library of Science launches its first open access journal, PLoS Biology

October 2003 Release of Berlin Declaration on Open Access to Knowledge in the Sciences and Humanities

October 2003 Financial analysts at BNP Paribas and Citigroup Smith Barney independently conclude that the business model of open access publishing is viable and is likely to put pressure on commercial publishers

December 2003 JISC announces £150 000 funding programme to help publishers make journals freely available on the internet using open access models

December 2003 Science and Technology Committee of the House of Commons announces an inquiry into access to journals within the scientific community, with particular reference to price and availability

December 2003 World Summit on the Information Society (co-sponsored by the UN and the International Telecommunications Union) endorses open access in its declaration of principles and plan of action

From subscription rates and circulation numbers it has been calculated that the scientific community currently pays about $4500/article.7 So for one third of this cost, research articles could be made available to all, instead of to a dwindling band of subscribers.

Several large funding agencies have already realised this: the US National Institutes of Health, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and the Wellcome Trust have all agreed to cover the costs of open access publishing.8 BioMed Central has struck deals with 360 institutions in 35 countries in exchange for an institutional membership fee; article processing charges are waived for researchers from member institutions. Last year agreements were announced with the NHS and 180 British universities—thereby covering most biomedical research being done in the United Kingdom.

Other funding agencies are considering their position, and several national and international initiatives that could help them work in a coordinated way are under discussion. One suggestion has been to agree a date after which funders will expect that all research conducted with their money will need to be published as open access.

Meanwhile, other journals have begun open access experiments. This month one of Oxford University Press's flagship journals, Nucleic Acids Research, has adopted an author funded publishing model for its annual database issue, making these articles freely available online from the moment they are published. The plan is to extend the experiment to the rest of the journal. Also this month, two journals published by the Cambridge based Company of Biologists—Development and the Journal of Cell Science—publish their first articles paid for by author charges.

What is the BMJ doing? We have been an open access journal since 1998, making the full text of our original research articles (along with everything else) freely available on the BMJ's website (bmj.com). We've paid for this not by authors' charges but with profits made from advertising. Whether original research articles remain free after we introduce access controls on bmj.com next January is still under discussion. But in the meantime, we intend exploring the feasibility of an author pays model for the journal, in several stages:

Gauging perceptions and understanding within the research community of the author pays model.

Exploring authors' reactions to several different such models.

Determining whether authors would be willing to pay to publish and which model they favour.

Experiment with several different models.

Our belief is that a long term sustainable model could be a mixture of “author pays” for original research articles and “reader pays” for the rest. The business logic is that the authors add most of the value with original research articles (by undertaking and writing up the research), whereas the editors and publishers add most of the value with the material they write or commission. A business model where journals are paid for the value they add is sustainable—and also provides an incentive for them to add more value. In contrast, a model where publishers charge for value added by others (the researchers) will be found out—as Reed Elsevier is beginning to discover. Indeed, it could even be argued that some publishers subtract rather than add value—because the minimal value they add is more than undone by their Balkanising medical research, making systematic reviews, for example, difficult and expensive.

All change is resisted. Three things seem necessary for resistance to be overcome and change to happen: a “burning platform,” a vision of something better, and “next steps.” The burning platform has been present for a long time among librarians but now has spread to academics, particularly in the United States. The vision of something better arrived with the internet. The “next step” is now provided by the idea of authors paying. The result, we predict, will be the rapid achievement of the dream of open access to scientific research.

Supplementary Material

Reviews p 56

Links and references for the box can be found on bmj.com

Links and references for the box can be found on bmj.com

We are grateful for the assistance of Peter Suber and Jan Velterop in compiling the contents of the box.

TD is a member of the national advisory committee of PubMed Central and a signatory of the Bethesda Statement on Open Access Publishing. TD and RS are employed by the BMJ Publishing Group, which depends on the traditional subscription model for a substantial proportion of its revenue.

References

- 1.Turner N. PLOS Biology. BMJ 2004;328: 56. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown PO, Eisen MB, Varmus HE. Why PloS became a publisher. PLoS Biol 2003. October;1(1): e36 DOI:10.1371/journal.pbio.0000036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Delamothe T, Godlee F, Smith R. Scientific literature's open sesame? BMJ 2003;326; 945-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldsmith C, Larsen K. Reed Elsevier's net jumped on solid subscription sales. Wall Street Journal Online 21 February 2003. (accessed 22 Dec 2003).

- 5.Gooden P, Owen M, Simon S, Singlehurst L. Scientific publishing: knowledge is power. www.econ.ucsb.edu/~tedb/Journals/morganstanley.pdf (accessed 19 Dec 2003).

- 6.Economic analysis of scientific research publishing: a report commissioned by the Wellcome Trust. London: Wellcome, 2003. www.wellcome.ac.uk/scipublishing (accessed 22 Dec 2003).

- 7.Velterop J. Public funding, public knowledge, publication. Serials 2003;16:169-74. www.uksg.org/serials.asp (accessed 22 Dec 2003).

- 8.Butler D. Who will pay for open access? Nature 2003;425: 554-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.