Abstract

Cocaine relapse can occur when cocaine-associated environmental cues induce craving. Conditioned place preference (CPP) is a behavioral paradigm modeling the association between cocaine exposure and environmental cues. The amygdala is involved in cocaine-cue associations with the basolateral amygdala (BLA) and central amygdala (CeA) acting differentially in cue-induced relapse. Activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors induces synaptic plasticity, the mechanism of which is thought to underlie learning, memory and drug-cue associations. The goal of this study was to examine the neural alterations in responses to group I mGluR agonists in the BLA to lateral capsula of CeA (BLA-CeLc) pathway in slices from rats exposed to cocaine-CPP conditioning and withdrawn for 14 days. MGluR1 but not mGluR5 agonist induced long-term potentiation (mGluR1-LTP) in the BLA-CeLc pathway was reduced in rats withdrawal from cocaine for 2 days and 14 days, and exhibited an altered concentration response to picrotoxin. Cocaine withdrawal also reduced GABAergic synaptic inhibition in CeLc neurons. Blocking cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1) reduced mGluR1-LTP in saline-treated but not cocaine-withdrawn group. Response to CB1 but not CB2 agonist was altered after cocaine. Additionally, increasing endocannabinoid levels abolished mGluR1-LTP in saline but not cocaine-withdrawn group. However, CB1 and CB2 protein levels were increased in the amygdala of cocaine-withdrawn rats while mGluR1 and mGluR5 remained unchanged. These data suggested that the mechanisms underlying the diminished mGluR1-LTP in cocaine-withdrawn rats involve an altered GABAergic synaptic inhibition mediated by modulation of downstream endocannabinoid signaling. These changes may ultimately result in potentiated responses to environmental cues which would bias behavior toward drug-seeking.

Keywords: cocaine CPP, mGluR1-LTP, GABA inhibition, endocannabinoid, synaptic transmission

INTRODUCTION

Relapse vulnerability is related to long-term adaptations in the brain that bias the individual’s behavior towards addiction (Nestler, 2001). Drug relapse can occur because drug-associated cues trigger craving (Shaham & Hope, 2005). Determining the neural mechanisms underlying drug-associated cues is critical for the development of effective treatments that reduce relapse vulnerability in cocaine addiction. Cocaine conditioned place preference (CPP) is a behavioral paradigm that models the association between drug exposure and environmental cues (Bardo et al., 1995).

The amygdala is important in the formation of stimulus-reward associations and in the processing of conditioned cue associational information. Lesions of amygdala subregions can completely block cocaine-induced CPP (Brown & Fibiger, 1993; Meil & See, 1997). Brain imaging studies show that the amygdala is activated in the presence of cocaine-related stimuli (Childress et al., 1999) and incubation of cocaine craving is mediated by time-dependent increases in signaling in the central amygdala (CeA) in response to cocaine cues (Lu et al., 2005). However, the underlying mechanisms are poorly understood.

Glutamate transmission plays a key role in both synaptic plasticity and cocaine addiction. Glutamate activates group I metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) which are composed of mGluR1 and mGluR5 subtypes. Group I mGluR agonist, (RS)-3,4-dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG) can induce long-term depression (DHPG-LTD) or long-term potentiation (DHPG-LTP) in different neurons from different brain regions (Volk et al., 2006; Manahan-Vaughan & Reymann, 1997). Both mGluR1 and mGluR5 antagonists are required to prevent induction of DHPG-LTD or DHPG-LTP (Le Vasseur et al., 2008).

Several studies provide evidence that DHPG responses are influenced by cocaine. After multiple exposures to cocaine, mGluR5-mediated LTD in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) is reduced but mGluR5 proteins are unchanged (Grueter et al., 2006). In contrast, a single cocaine exposure is correlated with a reduction in surface expression of mGluR5 in the nucleus accumbens (NAcc) (Fourgeaud et al., 2004), an effect that persisted three weeks after a seven-day cocaine administration (Swanson et al., 2001). Thus, differences in mGluR5 expression may reflect neuroadaptive changes in glutamatergic transmission after both acute and repeated cocaine administration. Group I mGluR activation also triggers release of endogenous endocannabinoids (eCBs) and a role for eCBs in mGluR-induced LTD has been demonstrated in numerous studies (Robbe et al., 2002; Chevaleyre & Castillo, 2003; Azad et al., 2004). Moreover, one dose of cocaine was shown to abolish eCB-induced LTD in the NAcc (Fourgeaud et al., 2004).

Cannabinoid signaling via CB1 is associated with modulation of γ-amino butyric acid (GABA) transmission. High levels of CB1 have been reported in BLA interneurons (Katona et al., 2001), and CB1 activation reduces evoked excitatory postsynaptic responses in the BLA (Domenici et al., 2006). The CeA contains a large number of GABAergic neurons (Sun & Cassell, 1993), which allows the CeA to function as a “gate” that modulates the incoming signals from BLA and conveys cue associations to other brain structures that control conditioned-cue behaviors (Ehrlich et al., 2009).

The aim of this study was to test the hypothesis that group I mGluRs are involved in the synaptic changes associated with cocaine-conditioned cues by GABAergic inhibition-dependent mechanisms in the BLA-CeLc pathway.

METHODS

Subjects

All animal procedures were carried out in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals as adopted and promulgated by the National Institutes of Health and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at UTMB and at Columbia University. Male Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan Inc, Houston, TX) were used as subjects. The animal ages ranged from 30–35 days for the 48 hours withdrawal paradigm to 44–49 days for the 14 days withdrawal paradigm. The rats were allowed to acclimate for 4 days in the institutional animal housing facility at constant temperature (21–23 °C) and humidity (45–50%) on a 12-h light-dark cycle (light 07:00–19:00) after arrival.

Conditioned place preference apparatus

Four acrylic animal chambers (16” × 16” × 12”) were contained inside of sound and light attenuating environmental control boxes (Accuscan Instruments, Inc, Columbus, OH). The chamber was subdivided into two distinct compartments, one with white floors and walls associated with a textured floorboard (raised Plexiglas bars), the other with black floors and walls on a smooth floorboard. The light intensity in the chambers was 320 lumens. On baseline and testing days, the animal was placed in a removable animal holding chamber (6” × 3” × 6”) that was inserted centrally between the black and the white compartment, and then raised, to allow the animal to freely roam both sides. Activity and time spent on each side were measured using the VersaMax activity monitor system (Accuscan Instruments, Inc, Columbus, OH). On conditioning days, a central removable 12” acrylic single pane wall was inserted to restrict the animal to one compartment.

Behavioral procedures

Each CPP experiment consisted of three phases: baseline, conditioning, and testing. For baseline measurements, twenty four hours prior to the first injection, one animal per chamber was allowed to freely roam both sides of the activity box for thirty minutes to test for the animal’s preference for one side over the other (i.e., a biased design). Animals were randomly assigned to the cocaine-treated experimental or saline-treated control animal group. Conditioning for the next five days involved receiving two injections daily separated by five hours. In the morning, both the saline and cocaine treatment groups were given saline (1 ml/kg of 0.9% saline solution, intraperitoneally, i.p.) and restricted to the preferred black compartment of the chamber for 30 minutes. In the afternoon, however, cocaine treated animals were injected with cocaine (15 mg/kg in 0.9% saline solution, i.p.) while saline treated animals were administered saline and both groups were restricted to the non-preferred white compartment for 30 minutes. During afternoon conditioning sessions two additional cues were included in the environmental control chambers: a flashing light (320 lumens, on fifteen seconds, off fifteen seconds) for five minutes and a 70 db white noise sound pulsing once per second for five minutes. On the sixth day (day 6) after the first injection (24 hrs after the last cocaine conditioning trial), all animals were tested by allowing them free access to both sides of the boxes for thirty minutes. During the test session, unlike the baseline, the light and sound cues were included. Two weeks after their last injection (day 19) another test session was performed in the presence of the sound and light cues to detect a persistence of CPP after two weeks withdrawal from repeated cocaine administration. Cocaine was not given to the rats on the CPP test days. A CPP score was calculated by subtracting the time spent on the drug paired side during baseline from the time spent on the drug paired side on the test day. Brain slices were prepared two weeks after the last injection of saline or cocaine (age 6–7 weeks) and used for electrophysiology and biochemistry studies.

Slice preparation

Coronal brain slices were prepared either 48 hours or 14 days after the injection paradigm. No anesthetics were used prior to decapitation to avoid their influence on neuronal plasticity. Initially, serial coronal slices (500µm) were bathed in oxygenated, modified ACSF solution (in mM), NaCl, (119); KCl, (3.0); NaH2PO4, (1.2); MgSO4, (1.2); CaCl2, (2.5); NaHCO3, (25); and glucose, (11.5) at room temperature (RT) for 1 hr. Slices were then transferred to a chamber where they were submerged and superfused with ACSF (1.0 ml, 2.5 ml/min) maintained at 30 ± 1°C.

Electrophysiology

Field potentials

Field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSPs) were recorded with tungsten electrodes (2–5 MΩ) in coronal brain slices cut ~ 3.3 to 3.8mm from bregma (Paxinos & Watson, 1998) which contained the lateral capsula region of the CeA (CeLc) and BLA. These fEPSPs were evoked by stimulating fibers in the BLA using 150 µs pulses of varying intensity (3–15 V) applied at 0.05 Hz through concentric electrodes (50 kΩ) while a recording electrode was positioned in the CeLc (Fig. 1B). All experiments were performed in the presence of 10 µM picrotoxin (PTX) in ACSF except where noted. Initially, fEPSP magnitude was adjusted to 30% of maximum response and baseline values recorded for 10 minutes, after which the group I specific mGluR agonist, (RS)-3,4-dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG) was superfused for 20 minutes. Other drugs were included in the ACSF 10 minutes prior to addition of DHPG to ACSF and continued throughout DHPG superfusion. Thereafter, fEPSPs evoked at a frequency of 0.05 Hz were recorded for an hour. Drug induced changes in fEPSP slopes during the experiment were calculated and normalized to baseline values.

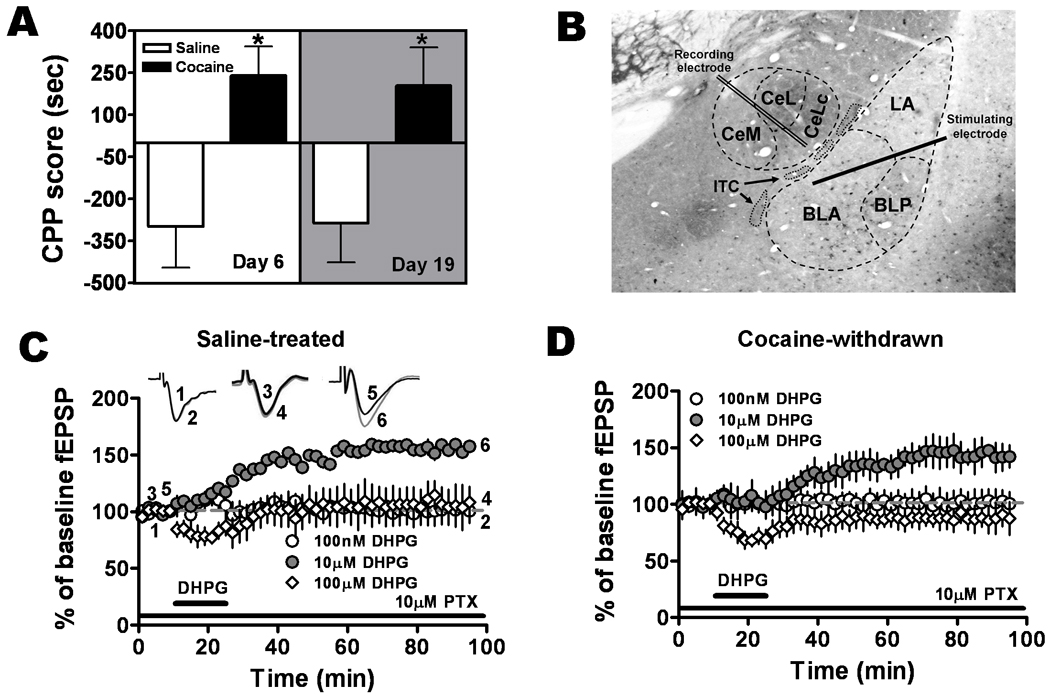

Figure 1.

DHPG 10 µM induced LTP in the BLA-CeLc pathway in amygdala slices from naïve and cocaine-withdrawn rats. A. Conditioned place preference to cocaine was observed after 24 hour and 14 day withdrawal from repeated cocaine administration. Cocaine-withdrawn rats (black bars) had significantly greater CPP scores on both day 6 and day 19 compared to saline-treated rats (white bars, twelve animals for each group, *P < 0.05). B. Illustration of recording and stimulation sites in an amygdala coronal brain slice immunolabeled for GAD67, an isoform of the GABA synthesizing enzyme glutamic acid decarboxylase. ITC, intercalated cell cluster. CeM, CeL and CeLC, medial, lateral, and laterocapsular subdivisions of the central nucleus, respectively. The stimulation electrode was positioned in the BLA whereas the recording electrode was positioned in the CeLc. C. DHPG, 10 µM (solid circles, n = 6, six animals), but not 100 nM (open circles, n = 4, four animals) or 100 µM (diamonds, n = 4, four animals) induced LTP of the fEPSP in amygdala slices from saline-treated rats. D. 10 µM but not 100nM or 100µM DHPG produced LTP in cocaine-withdrawn rats.

Whole-cell patch clamp recordings

Whole-cell recordings using the “blind” patch technique were obtained from neurons in the CeLc (Fig. 1B) as described previously (Liu et al., 2004). Briefly, patch electrodes were made from borosilicate glass capillaries using a Flaming-Brown micropipette puller (P-97; Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA). Whole-cell recordings were obtained with patch electrodes having tip resistances of 3–5 MΩ when filled with an internal solution of (in mm): K-gluconate, 122; NaCl, 5; CaCl2, 0.3; MgCl2, 2; EGTA, 1; HEPES, 10; Na2-ATP, 5; and Na3-GTP, 0.4; adjusted to pH7.2–7.3 with KOH. After tight (>2 GΩ) seals were formed and the whole-cell configuration was obtained, neurons were included in the sample if the resting membrane potential (RMP) was more negative than −60 mV and action potentials overshooting 0 mV were evoked by direct depolarizing current injections. Acceptable recordings showed only stable access resistances of < 25 MΩ. Voltage-clamp (discontinuous single-electrode voltage clamp) recordings were made using an Axoclamp-2A amplifier (Molecular Devices) with a switching frequency of 5–6 kHz (30% duty cycle), gain of 3–8 nA/mV, and time constant of 20 ms. In all experiments, series resistance was monitored throughout the experiment, and if it changed by more than 10% during a recording, the data were not included in the analysis. Data were analyzed off-line with pClamp9.2 software (Molecular Devices, USA).

Miniature IPSCs

mIPSCs of neurons in the CeLc were isolated pharmacologically with tetrodotoxin (TTX) 1 µM, DL-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (DL-APV) 50 µM, 1µM CGP 55845 and DNQX 10 µM, and were recorded at −50 mV. A fixed length of traces (5 min) was analyzed for frequency and amplitude distributions of mIPSCs using MiniAnalysis program 5.3 (Synaptosoft, Decatur, GA).

Biotinylation of Surface Receptors

Methods for biotinylation assay were essentially followed the protocol reported in Gutlerner et al (2002). 300 µm coronal slices containing the BLA and the CeA were dissected from rats withdrawn for 2 weeks from repeated injections of saline or cocaine. The slices were transferred into ice-cold modified ACSF + biotin (1 mg/ml; NHS-SS-biotin, Pierce Chemical Company, Rockford, IL) solution oxygenated with 95% O2 ± 5% CO2 and incubated for 45 minutes on ice. Slices were rinsed twice for 15 minutes each with ice-cold modified ACSF to wash away unbound biotin followed by a wash with TBS buffer (50 mM Tris-HCL, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl) for 5 minutes to quench the biotin reaction. The amygdala tissue was homogenized in RIPA buffer [25 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS and protease inhibitor cocktail tablets (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany)]. Homogenates were incubated on ice for 20 min and then centrifuged at 14,000g at 4°C for 15 minutes. Protein concentrations in supernatants were measured using the BCA protein assay (Pierce Chemical Company). Protein (10–15 µg) was removed to measure total mGluR1, mGluR5 and GAPDH (internal control for biotinylated intracellular proteins). For surface protein, 100 µg of protein are incubated with 150 µl of 50% Neutravidin agarose (Pierce Chemical Company) overnight at 4°C and bound proteins were resuspended in 60 µl of SDS sample buffer and boiled. Quantitative Western blots were performed on both total and biotinylated (surface) proteins using antibodies for mGluR1 and mGluR5 (1:500, Alomone, Jerusalem, Israel), GAPDH (1:25,000, clone 6C5 mouse monoclonal, Advanced Immunochemicals Inc., Long Beach, CA) and actin (1:10,000, clone C4 mouse monoclonal, Millipore, Billerica, MA). Approximately 3% of GAPDH was biotinylated, indicating that very little intracellular protein contaminated the 'surface' fraction.

Western Blotting

Protein samples were separated on a 10% acrylamide gel by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane overnight in a cold room. The membranes were then blocked for at least one hour at RT in LI-COR (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, Nebraska) blocking buffer and then incubated overnight in primary antibodies for CB1 receptor (1:500, L15 C-terminal antibody kindly provided by Dr. Ken Mackie) and CB2 receptor (1:500, C-terminal, Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI). After removal of the antibody, the blot was washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBST). All further steps were carried out in the dark to prevent the loss of sensitivity of the infrared dye secondary antibodies. LI-COR infrared dye secondary antibodies, goat anti-rabbit (926-32211-IRDye 800CW) and donkey anti-mouse secondary antibodies (926-32222-IRDye 680) were diluted 1:20,000 each in LI-COR blocking buffer and applied for one hour at RT. Membranes were scanned directly using the Odyssey Infrared Fluorescent Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA).

Drugs

Cocaine HCl was a gift from the National Institute of Drug Abuse. D-aminophosphonovaleric acid (APV), methanandamide, N-(piperidin-1-yl)-5-(4-iodophenyl)-1-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)-4-methyl-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxamide (AM251), 1-(2,3-dichlorobenzoyl)-5-methoxy-2-methyl-3-[2-(4-morpholinyl)ethyl]-1H-indole (GW405833), (S)-(+)-a-amino-4-carboxy-2-methylbenzeneacetic acid (LY367385), and (RS)-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine (R,S-DHPG) and 2-methyl-6-(phenylethynyl)pyridine hydrochloride (MPEP) were purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Ellisville, MO). N-5Z,8Z,11Z,14Z-eicosatetraenyl-4-hydroxybenzamide (AM1172) and (3’-(aminocarbonyl) [1,1’-biphenyl]-3-yl)-cyclohexylcarbamate (URB597) were purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). Picrotoxin (PTX) was obtained from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Statistical analysis

The data for each experiment are presented as the mean ± SEM. The significance of the difference between the groups was calculated by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's post hoc analyses or Student's t test where appropriate. P values of <0.05 were considered to represent significant differences.

For experimental analysis of CPP, the time spent on each of the two sides per box was determined for each individual rat during the 30 minutes testing period, and data reported as a CPP score, which is the mean time spent on the drug paired side on the test day minus time spent on the drug paired side during baseline. A negative CPP score indicated that a population of animals tested spent less time on the drug-paired side during the testing session than during the baseline session, suggesting that place preference did not develop. Conversely, if a population of animals spent more time on the drug-paired side than during the baseline session the score would be positive, indicating that a place preference had developed during the training period.

In LTP experiments, changes were quantified by normalizing and averaging fEPSP slopes during the last 10 minutes of the experiments relative to the 5 minutes of baseline prior to LTP induction or drug application.

For western blots, receptor band densities were quantified using the integrated intensity values determined by the Odyssey software. The level of protein changes was calculated by analyzing the ratio of the integrated intensity value of the protein specific antibody to the loading control in each lane to provide an integrated intensity ratio.

RESULTS

Conditioned place preference after five days of repeated cocaine treatment was measured on day six and persisted after two weeks of withdrawal

Following five days of conditioning training, animals were tested for CPP on day 6 and then on day 19. Cocaine-treated rats had a higher CPP score on both day 6 (240.3 ± 103.0 seconds, n=12) and on day 19 (204.4 ± 136.4 seconds, n=12) compared to saline-treated rats (day 6: −98.4 ± 146.1 seconds, n=12; day 19: −286.2 ± 141.0 seconds, n=12) (Fig. 1A). A two-way ANOVA analysis revealed a significant preference for the cocaine-paired compartment relative to the saline group (F1,44 = 15.48, P = 0.0003). In a separate set of animals, cocaine treatment was paired with the preferred black side. No significant difference in CPP score was obtained in counterbalance experiments in which cocaine was paired with the preferred side (day 19: 245.85 ± 73.67 seconds, n=19) compared to cocaine injection in the non-preferred sides (day 19: 204.4 ± 136.4 seconds, n=12, P = 0.45). Thus, a strong cocaine-associated conditioning effect was observed after five days of administration and persisted after two weeks of withdrawal.

DHPG induces a concentration dependent LTP in the BLA-CeLc pathway

To examine group I mGluR responses at the BLA-CeLc synapses, we initially investigated the effects of DHPG, an mGluR1 and mGluR5 agonist, on the magnitude of excitatory synaptic transmission by measuring the slope of fEPSPs in brain slices from saline-treated rats (Fig. 1C). At a lower concentration of 100 nM, DHPG did not produce any significant change in fEPSPs (100.3 ± 11.9% of baseline, P = 0.195, n=4). Similarly, at a higher concentration of DHPG (100 µM), no significant enhancement of fEPSPs was detected (107.4 ± 4.5% of baseline, P = 0.123, n=4), rather, a short duration of inhibitory effect was observed during DHPG application. However, at a moderate concentration of 10 µM, DHPG induced a robust LTP (155.1 ± 14.7% of baseline, P = 0.001, n=6) in the BLA-CeLc pathway. We also tested the effects of different concentrations of DHPG on the fEPSPs in slices from cocaine-withdrawn rats (Fig. 1D). Similarly, at a concentration of 10 µM, DHPG produced a stable LTP (143.34 ± 11.5% of baseline, P = 0.003, n = 5) in the presence of 10µM PTX. Comparing with the LTP in slices from saline-treated rats, there was a small but not significant decrease in the magnitude of LTP (P > 0.05). In contrast, neither 100 nM nor 100 µM of DHPG produced a significant potentiation of fEPSPs in slices from cocaine-withdrawn rats (100nM: 101.46 ± 11.6% of baseline, n = 5; 100µM: 87.74 ± 11.9% of baseline, n = 6), rather, a slight but not significant long-lasting depression of the fEPSP was observed. Therefore, the 10 µM DHPG was used in all subsequent experiments.

LTP induced by DHPG through activation of mGluR5 receptors was not different in slices from saline-treated and cocaine-withdrawn rats

To investigate the subtype specificity of mGluRs in mediating DHPG-LTP, LY367385 (100 µM), the selective mGluR1 antagonist, was applied 5 minutes before and during the application of DHPG (10 µM); this treatment paradigm effectively activated only mGluR5 receptors (Fig. 2A). LY367385 itself depressed fEPSPs. Following the onset of washout of DHPG/LY367385 the depressed fEPSPs started to recover and subsequently potentiated above the baseline level in slices from both saline (135.7 ± 10.8%, n=9, P = 0.02) and cocaine-withdrawn (128.3 ± 9.0%, n=9, P = 0.04) rats. Pretreatment with LY367385 did not prevent the expression of LTP although the magnitude of LTP in slices from saline-withdrawn group was smaller than that observed in slices from naïve animals. However, the magnitude of fEPSP potentiation by DHPG/LY367385 was not significantly different between saline- and cocaine-withdrawn groups (P > 0.05, n=9). These results suggested that mGluR5-induced LTP (mGluR5-LTP) was not altered after cocaine withdrawal.

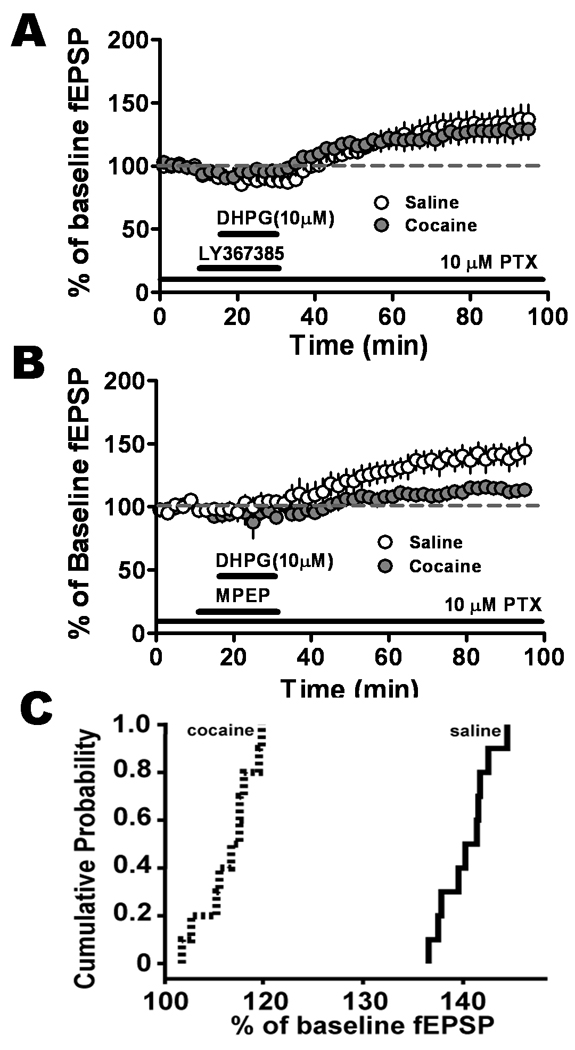

Figure 2.

DHPG 10 µM induced LTP mediated through mGluR1, not mGluR5, which was significantly different in the BLA-CeLc pathway in amygdala slices from saline-treated and cocaine-withdrawn groups. A. mGluR5-mediated LTP induced by DHPG in the presence of LY367385 100 µM, an mGluR1 antagonist, was not significantly different in the slices from saline-treated (open circles, n = 9, seven animals) and cocaine-withdrawn (solid circles, n = 9, eight animals) groups. B. In the presence of MPEP 10 µM, mGluR1-LTP was significantly reduced in slices from cocaine-withdrawn rats (solid circles, n = 8, eight animals). C. Cumulative probability distribution of normalized fEPSP values obtained from the last 10 min of recording were represented as averages in B. LTP levels associated with the cocaine-withdrawn (dotted lines) group were dramatically lower than that of saline-treated (solid line) group.

mGluR1-LTP was reduced in slices from cocaine-withdrawn rats

We next tested the effects of MPEP, a selective mGluR5 antagonist, on DHPG-LTP. DHPG-LTP was unaffected by pretreatment of slices with MPEP (10 µM) in the saline-treated group (Fig. 2B, 141.4 ± 8.9%, n=8), suggesting the presence of mGluR1-LTP. In contrast, DHPG/MPEP caused a smaller mGluR1-LTP in slices from cocaine-withdrawn rats (115.5 ± 4.5% of baseline, n=8). The difference in LTP magnitude between saline-treated and cocaine-withdrawn groups was significant (P = 0.032) indicating a change in mGluR1 responsiveness two weeks after cocaine treatment. Plots of the cumulative probability distributions of the last 10 min of fEPSP values showed that the magnitude of fEPSP changes relative to baseline was dramatically reduced in slices from cocaine-withdrawn group (Fig. 2C).

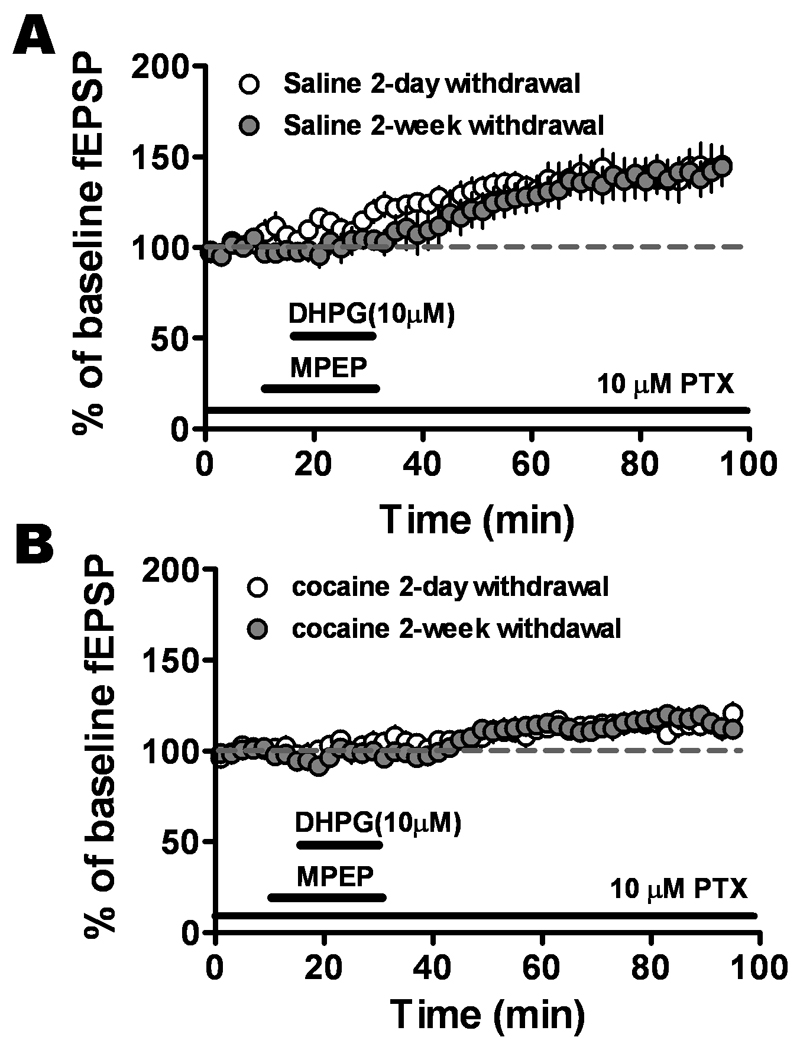

Reduction in mGluR1-LTP was not a function of cocaine withdrawal time

To investigate mGluR1-LTP after a short withdrawal from cocaine, slices were prepared from CPP trained animals 48 hours after the last injection. DHPG/MPEP induced LTP compared to baseline in slices from two day (143.1 ± 11.5% of baseline, n=6) and two weeks (141.4 ± 8.9%, n=8) of the last injection in saline-treated animals (Fig. 3A) but with no significant difference between them (P = 0.281). DHPG/MPEP induced LTP in slices from two day (115.1 ± 4.6% of baseline, n=5) and two week (115.5 ± 4.5% of baseline, n=8) withdrawn cocaine animals (Fig. 3B) showed no significant difference in LTP magnitude (P = 0.42). These data suggested that the change in mGluR1 responsiveness after cocaine treatment was due to the treatment itself and not dependent on the length of the withdrawal period.

Figure 3.

The reduced mGluR1-induced LTP in slices from cocaine-withdrawn group was not dependent on withdrawal time. A. DHPG/MPEP-induced increases in fEPSP values in slices from saline-treated rats sacrificed two days after last injection (open circles, n = 6, six animals) were equivalent to those from saline-treated rats sacrificed two weeks after the last injection (solid circles, n = 8, seven animals). B. The DHPG/MPEP induced LTP in slices from two-day cocaine-withdrawn group (open circles, n = 5, five animals) were not significantly different than those from two-week cocaine-withdrawn group (solid circles, n=8, seven animals, P > 0.05).

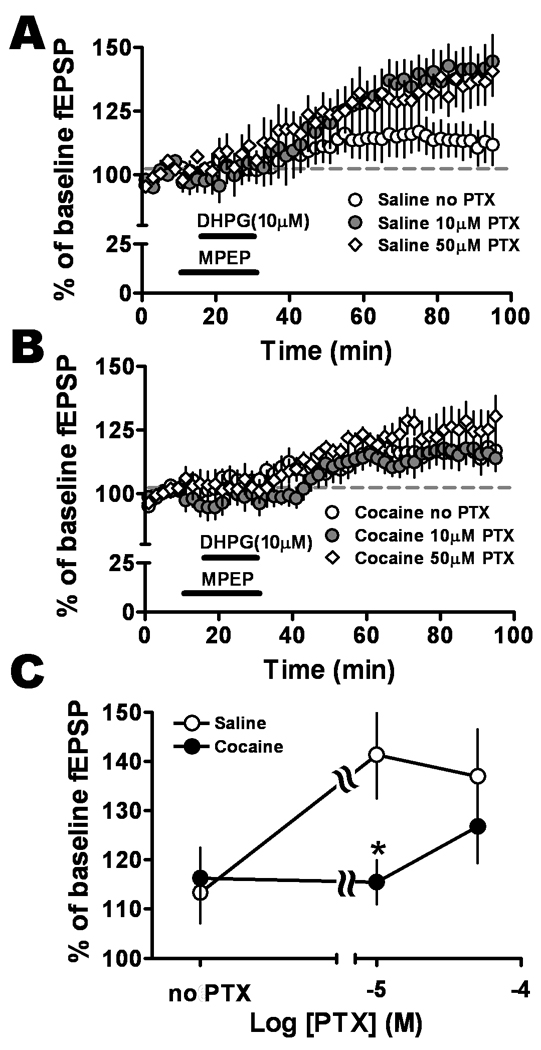

Differences in mGluR1-LTP in saline-treated and cocaine-withdrawn animals were abolished by attenuating GABAergic transmission

CeA contains a large number of GABAergic neurons (Sun & Cassell, 1993). Because of the location of our recording electrode in the CeA, it is possible that mGluR1-LTP in the BLA-CeLc pathway was partially due to modulation of GABAergic inhibition. To investigate this possibility, we applied a high concentration of a GABAA receptor antagonist, PTX (50 µM). mGluR1-LTP (136.9 ± 9.6% of baseline, n=6) at 50 µM PTX was not significantly different than that recorded at 10 µM PTX (141.4 ± 8.9%, n=8, P > 0.05) in slices from saline-treated animals (Fig. 4A). Slices from the cocaine-withdrawn group also exhibited LTP at 10 µM PTX (115.5 ± 4.5%, n=8) and although LTP magnitude increased with the higher PTX concentration, it was not significantly different than that recorded at 50 µM PTX (126.8 ± 7.4%, n=8, P = 0.21) (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Relative levels of GABA inhibition provided a switch for cocaine influence on mGluR1-LTP. Recordings were obtained in either the presence of 50 µM and 10 µM PTX applied throughout the experiment or the absence of PTX. A. Concentration-response relationship for PTX in slices from saline-treated animals showed that blocking GABA inhibition facilitated mGluR1-LTP, with 10 µM (solid circles) and 50 µM PTX (diamonds) exhibiting greater potentiation than in the absence of PTX (open circles). B. Concentration-response relationship for PTX in slices from cocaine-withdrawn animals indicated that blocking GABA inhibition with 50 µM PTX (diamonds) resulted in the largest facilitation of mGluR1-LTP compared to no PTX (open circles) or 10 µM PTX (solid circles) suggesting a role for GABA inhibition-dependent mechanisms. C. Graph of concentration-response relationship for PTX. A significant difference in mGluR1-LTP between the two animal populations was only revealed at 10 µM PTX concentration (saline-treated group, open circles; cocaine-withdrawn, solid circles, F2,44 = 3.41, *P = 0.042, two-way ANOVA).

However, mGluR1-LTP magnitude in slices from the cocaine group (50 µM PTX: 126.8 ± 7.4%, n=8) was not significantly different than that in slices from saline-treated animals (50 µM PTX: 136.9 ± 9.6%, n=6, P > 0.05, Fig. 4A and B). This result indicated that further blocking GABAergic inhibition with higher PTX concentration (50 µM) eliminated the difference in magnitude of mGluR1-LTP in the two treatment groups.

We also examined mGluR1-LTP without blockade of GABAergic inhibition. In the absence of PTX, there was no significant difference between saline-treated (113.1 ± 7.0, n=9) and cocaine-withdrawn (116.3 ± 5.6, n=11) treatment groups (P = 0.12, Fig. 4A and B); but within saline-treated group, the LTP induced in the presence of GABAergic inhibition was significantly smaller than that at 10 µM PTX (P < 0.01).

Interestingly, slices from cocaine-withdrawn animals showed no significant differences in the mGluR1-LTP in the absence and presence of PTX, suggesting that mGluR1 activation induced glutamatergic synaptic plasticity was not dependent on the level of GABAergic inhibition in the cocaine-withdrawn group.

mGluR1-LTP was independent of NMDA receptors

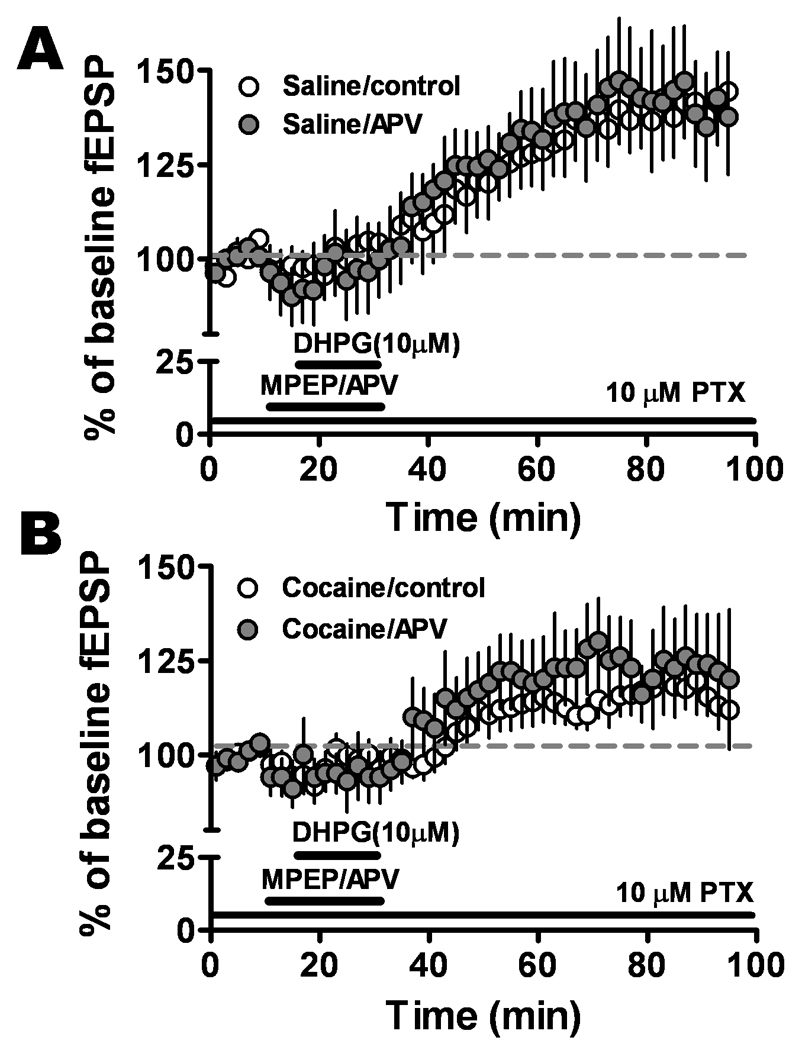

The NMDA receptor (NMDAR) is required for neuronal activity to change the strength of many synapses. We therefore examined the role of NMDA receptors in mGluR1-LTP using the specific NMDAR antagonist, APV. In the presence of APV (50 µM), mGluR1 activation also induced LTP (saline APV: 140.1 ± 13.8%, n=7 and cocaine APV: 122.7 ± 13.1; n=8), which was not significantly different from APV-untreated slices (saline: 141.4 ± 8.9%, n=8 and cocaine: 115.5 ± 4.5; n=8, P = 0.17) (Fig. 5B). These results suggested mGluR1-LTP in the BLA-CeLc pathway was NMDAR-independent; similar to that seen in the BNST by Grueter et al. (2006).

Figure 5.

mGluR1-LTP was not dependent on NMDA receptors. Pretreatment with NMDA receptor antagonist APV 50 µM did not affect the potentiation in the slices from A. saline-treated (control, open circles; APV, solid circles, n = 7, six animals) and B. cocaine-withdrawn (control, open circles; APV, solid circles, n = 8, six animals) groups.

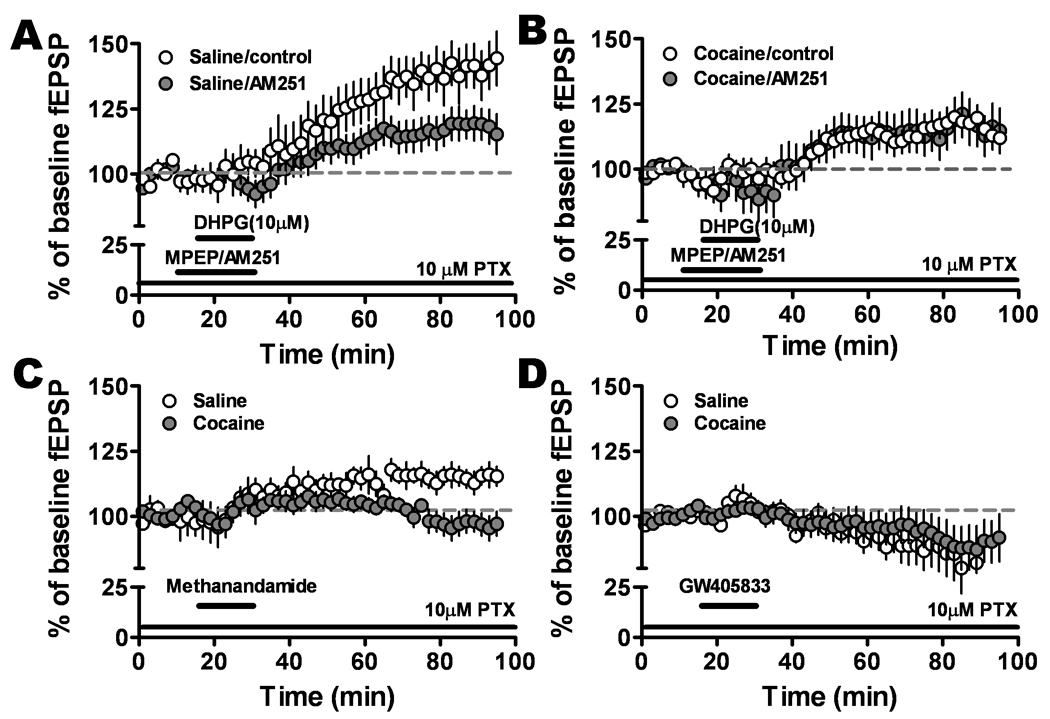

Endocannabinoids mediate the mGluR1-LTP in the BLA-CeLc pathway

Group I mGluR activation triggers the release of eCBs (Maejima et al., 2001). We examined the role of CB1 receptors in mGluR1-LTP using the specific CB1 antagonist, AM251 (1 µM). In slices from saline-treated animals, mGluR1-LTP (141.4 ± 8.9%, n=8) was reduced (114.3 ± 5.9%, n=7) significantly (P = 0.001) in the presence of AM251 (Fig. 6A). In slices from the cocaine-withdrawn group, mGluR1-LTP was not significantly different in the presence (115.6 ± 8.3%, n=8) and absence (115.5 ± 4.4%, n=8) of AM251 (P = 0.23, Fig. 6B). Additionally, there was no significant difference between AM251-treated slices from saline-treated animals and AM251-untreated slices in the cocaine-withdrawn population (P = 0.08). These data suggest that the reduction in mGluR1-LTP in the cocaine-withdrawn group may be due to loss of an eCB contribution.

Figure 6.

mGluR1-LTP was dependent on CB1 receptor activation. A and B. CB1 antagonist reduced fEPSP in slices from saline-treated (control, open circles; AM251, solid circles, n = 7, six animals), but not in the cocaine-withdrawn group (control, open circles; AM251, solid circles, n = 8, six animals). C. The selective CB1 agonist, methandamide (1 µM), induced LTP in the slices from saline-treated (open circles) but not the cocaine-withdrawn (solid circles) group. D. CB2 partial agonist, GW408633 (1 µM), inhibited fEPSP amplitude in the saline-treated (open circles) group to levels similar to that in the cocaine-withdrawn (solids circles) group.

To test whether exogenously applied cannabinoid agonists could activate CB receptors directly, the effects of selective CB1 and CB2 receptor agonists were examined. Application of a selective CB1 receptor agonist, methandamide (1 µM), elicited a small LTP in the slices from saline-treated (115.5 ± 3.8% of baseline, n=7) but not the cocaine-withdrawn group (100.0 ± 3.1%, n=5, Fig. 6C); similar results were obtained with another selective CB1 agonist, 1 µM WIN 55212-2 (saline WIN: 123.8 ± 4.4%; n=4; cocaine WIN: 107.1 ± 11.4%; n=8). While both agonists can activate CB2 receptors; their affinity for CB1 is 40 times greater than for CB2. In contrast, a potent partial agonist for the CB2 receptor, GW405833 (1 µM), reduced fEPSPs (89.7 ± 8.3%, n=6) in slices from saline-treated and cocaine-withdrawn group (80.5 ± 11%, n=6, Fig. 6D).

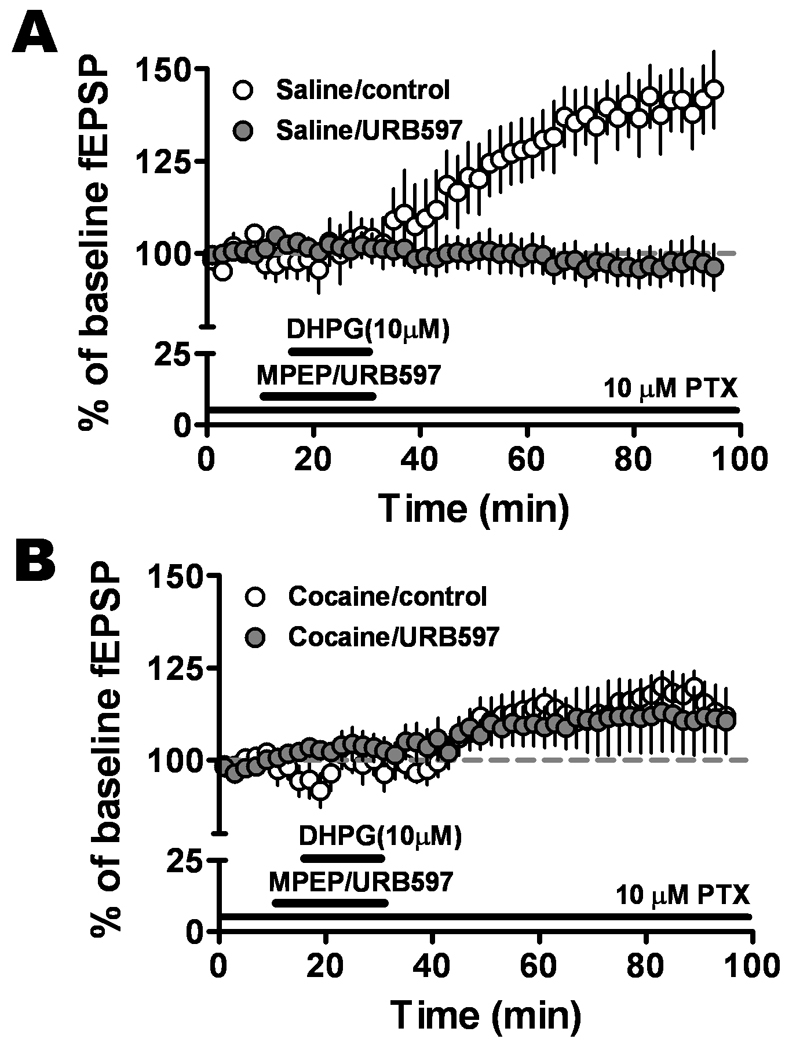

We also questioned whether raising eCBs would restore the depressed mGluR1-LTP recorded in slices from cocaine-withdrawn back to the normal level seen in saline-treated animals. We tested the effect of URB597, an inhibitor of fatty acid amide hydrolysis that enhances the actions of endogenous anandamide. URB597 (1 µM) completely blocked the mGluR1-LTP in slices from saline-treated group (saline: 140.0 ± 9.8; n=8; saline URB597: 96.7 ± 5.5; n=7, P < 0.0001, Fig. 7A) but had no effect in the cocaine-withdrawn group (cocaine: 116.6 ± 4.7, n=8; cocaine URB597:114.5 ± 9.5, n=6, P = 0.34, Fig. 7 B). These data indicated that inhibiting anandamide breakdown blocked the mGluR1-LTP in the saline-treated group, an unexpected finding, and that increasing endogenous anandamide did not reverse the depressed mGluR1-LTP caused by cocaine withdrawal.

Figure 7.

Increasing eCB concentrations in the amygdala reduced mGluR1-LTP in the saline but not in the cocaine CPP group. URB597 (1 µM), an inhibitor of anandamide hydrolysis, completely blocked the mGluR1-LTP in saline-treated (control, open circles; URB597, solid circles) group, but had no significant effect in the cocaine-withdrawn (control, open circles; URB597, solid circles) group.

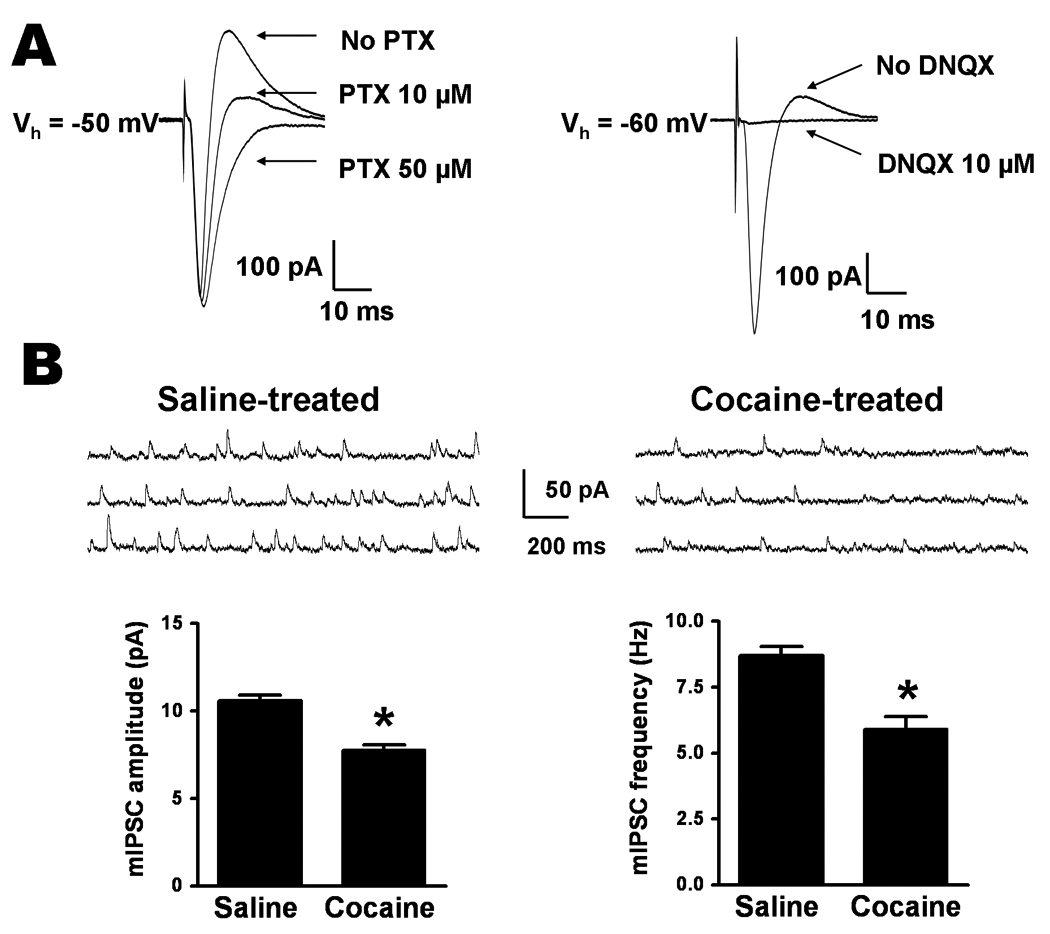

Feedforward inhibition in the BLA-CeLc pathway

The intercalated cell masses (ITCs), a population of GABAergic cell clusters, form an inhibitory interface that gates impulse traffic between the BLA and CeA (Royer et al., 1999; Millhouse, 1986). To analyze excitatory and inhibitory synaptic transmission in the BLA-CeLc pathway, we performed whole-cell patch recordings in the CeLc neurons. At holding potentials of −60 mV and −50 mV, a biphasic synaptic current was recorded in response to a stimulus in the BLA (Fig. 8A). The outward but not the inward component of synaptic current was fully blocked by superfusion with 50 µM PTX while at a lower concentration of 10 µM PTX it was only partially blocked. However, application of 10 µM DNQX completely abolished both inward and outward currents. These data suggest that the CeLC neurons receive direct glutamatergic inputs from the BLA, and indirect feedforward inhibition mediated by the glutamatergic excitation of GABAergic cells in ITC and CeA neurons.

Figure 8.

Cocaine withdrawal reduces GABAerigic inhibition in CeLc neurons. A. BLA stimulation evokes feedforward IPSCs in CeLc cells. A biphasic synaptic waveform recorded from a CeLc neuron consists of a downward EPSC and upward IPSC components. IPSC was completely blocked by 50 µM PTX but was partially reduced by 10 µM PTX (left). Superfusion of DNQX abolished both EPSC and IPSC, indicating that BLA neurons generate a feedforward IPSC in the BLA-CeLc pathway (right). B. Comparison of the mean amplitude and frequency of mIPSCs recorded in CeLc neurons from rats 2 weeks after saline or cocaine withdrawal. Top, representative recordings of mIPSCs from CeLc neurons in saline-withdrawn (left traces) and cocaine-withdrawn (right traces) rats. Bottom, analytical summary of mIPSCs showing that a significant reduction in both the amplitude and the frequency of mIPSCs in cocaine withdrawal group (*P < 0.05, n = 6, six animals for each group, t-test).

Cocaine withdrawal reduced basal spontaneous mIPSCs in the CeLc neurons

Since as aforementioned, GABAergic synaptic transmission in the BLA-CeLc pathway is through multisynaptic indirect routes, we then studied basal spontaneous mIPSCs of the CeLc neurons to evaluate possible changes in local inhibitory transmission in cocaine-withdrawn and saline-withdrawn rats. The mIPSCs were pharmacologically isolated in the presence of 1 µM TTX, 50 µM APV, 1µM CGP 55845 and 10 µM DNQX. We compared the baseline frequency and amplitude of mIPSCs in both cocaine-treated and saline-treated rats. The mean frequency of mIPSCs was significantly lower (P = 0.0007) in CeLc neurons of cocaine-withdrawn rats (5.92 ± 0.5 Hz, n = 6) than in those of saline-withdrawn rats (8.71 ± 0.3 Hz, n = 6) (Fig. 8B), suggesting a decrease in GABA release after withdrawal from repeated cocaine injection. In slices from cocaine-treated rats, the mean amplitude of mIPSCs was also significantly reduced compared to the saline-treated group (saline: 10.6 ± 0.3 pA, n = 6 vs. cocaine: 7.77 ± 0.29 pA, n = 6; P < 0.0001) (Fig. 8B), indicating a possible reduction in postsynaptic function of GABAA receptors occurred after cocaine withdrawal for 2 weeks.

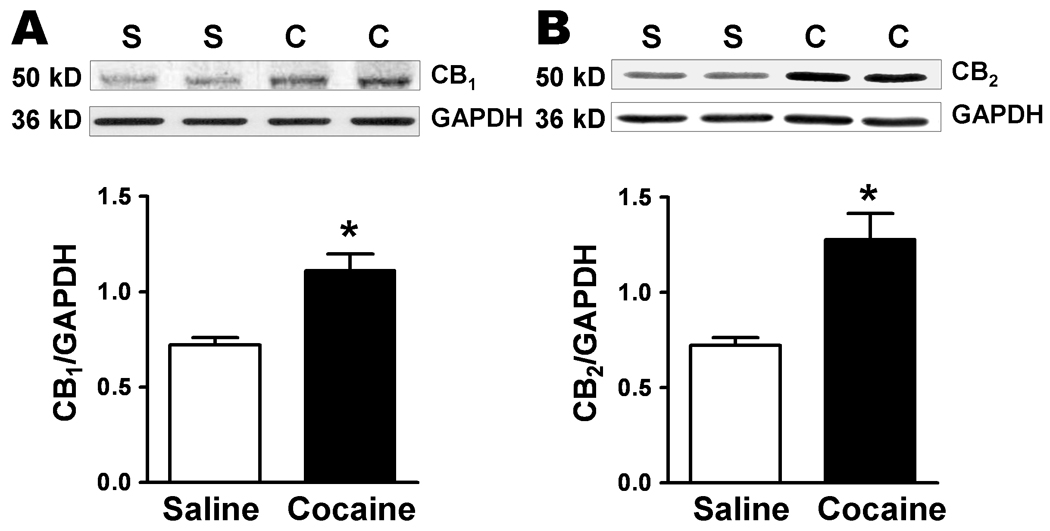

Protein levels of CB1 and CB2 receptors increased in the amygdala of the cocaine-withdrawn group while levels of mGluR1 and mGluR5 remained unchanged

We subsequently analyzed protein expression of CBs and mGluRs in the amygdala from saline- and cocaine-withdrawn animals (Fig. 9). We observed a single band at ~50 kDa for CB1 and CB2 receptor in amygdala total protein lysate. Protein levels of both receptors were significant increased in the amygdala of the cocaine-withdrawn group (CB1: 1.11 ± 0.09, n = 4; CB2: 1.28 ± 0.134, n = 4) compared to the saline-treated group (CB1: 0.72 ± 0.04, n = 4, P = 0.006; CB2: 0.72 ± 0.04, n = 4, P = 0.007).

Figure 9.

CB1 and CB2 receptor protein levels are increased in the amygdala after Cocaine CPP (saline, white bars; cocaine, black bars, *P < 0.05). Blots of amygdala protein, each lane from a saline- (S) or cocaine- (C) treated single animal, are shown above and the summary data for the different bands are graphed below. Data is expressed as ratios using GAPDH as a standard for protein loading.

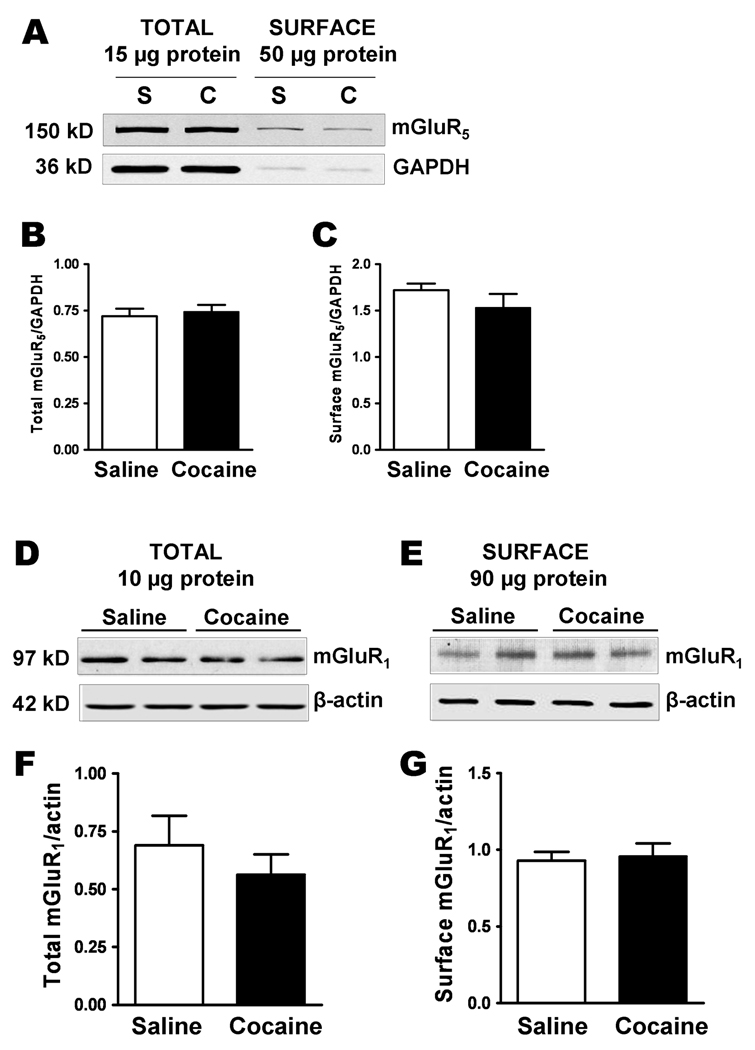

We also examined protein surface expression of mGluR1 and mGluR5 in the amygdala from the rats that had received repeated injections of either saline or cocaine followed by 2 weeks withdrawal (Fig. 10). Biotinylated surface proteins were separated from unlabled intracellular proteins by affinity purification applications. Bands were detected at 97 kDa for mGluR1, which corresponds to mGluR1β receptor (Ferraguti et. al., 1998), and at 150 kDa for mGluR5. However, we could not detect significant differences in total and surface levels of either mGluR1 or mGluR5 when comparing cocaine-treated to saline-treated animal groups (surface mGluR1: 0.93 ± 0.06 in saline vs. 0.96 ± 0.08 in cocaine, n=4, P = 0.79; total mGluR1: 0.69 ± 0.13 in saline vs. 0.56 ± 0.09 in cocaine, n=4, P = 0.44; total mGluR5: 0.72 ± 0.04 in saline vs. 0.74 ± 0.03 in cocaine, n = 3, P = 0.70; surface mGluR5: 1.72 ± 0.07 in saline vs. 1.5 ± 0.14 in cocaine, n=3, P = 0.36), indicating that the reduced mGluR1-LTP is not mediated through altering protein levels of group I mGluRs expression.

Figure 10.

Surface and total protein expression of mGluR1 and mGluR5 is unchanged after withdrawal from repeated cocaine exposure. A. A western blot of biotinylated amygdala slices from saline- (S) and cocaine- (C) treated and withdrawal rats showing the total and surface protein levels of mGluR5 and GAPDH. 50 µg protein was loaded into the ‘surface’ lanes and 15 µg protein was in the ‘total” lanes. B and C. The level of biotinylated surface protein expression was normalized to intracellular protein, GAPDH. The amount of biotinylation of GAPDH was 0.035 ± 0.03 (saline) and 0.034 ± 0.01 (cocaine) of the total protein. D and E. Western blots showing the expression levels of mGluR1 in total and surface protein of amygdala slices from saline- and cocaine-withdrawn rats. Statistical comparisons of the total and surface expression of mGluR1 are shown in graphs below F and G. Data were normalized by actin as an internal loading reference.

DISCUSSION

The main findings of this study are that in the amygdala BLA-CeLc pathway withdrawal from cocaine conditioning: 1) reduced mGluR1- but not mGluR5-mediated LTP; 2) altered the concentration-response to PTX for DHPG-induced LTP; 3) reduced local spontaneous GABAergic synaptic inhibition; 4) reduced the effects of the CB receptor antagonist and agonist; 5) masked effects of increasing eCBs and 6) changed amygdala protein levels of CB1 and CB2 but not mGluR1 and mGluR5 receptors. These data suggest that the diminished mGluR1-LTP during cocaine withdrawal involves alterations in GABAergic synaptic inhibition through CB receptor-mediated mechanisms.

mGluR1- not mGluR5-mediated LTP in the BLA-CeLc pathway was reduced after withdrawal from cocaine

Blocking DHPG-LTD in CA1 neurons requires inhibition of mGluR1 and mGluR5 (Volk et al., 2006), while only mGluR5 inhibition is required in the BNST (Grueter et al., 2006). It is likely that differences in LTP induction in different nuclei are due to variations in receptor subtypes at specific synapses. In our study, mGluR1- but not mGluR5-induced LTP at the BLA-CeLc synapse was reduced following withdrawal from chronic cocaine, indicating that mGluR1 but not mGluR5-mediated responses were altered in the BLA-CeLc pathway.

The amygdala expresses moderate levels of mGluR5 (Romano et al., 1995) and low levels of mGluR1 (Martin et al., 1992) protein. In our studies, after repeated cocaine administration, both surface and total mGluR1 and mGluR5 protein levels measured by western blotting were not different from the saline-treated group, suggesting that cocaine CPP does not alter protein levels of group I mGluRs expression. In behavioral studies, an mGluR5 antagonist does not prevent cocaine-induced CPP (Herzig & Schmidt, 2004) while behavioral sensitization to cocaine’s psychomotor activity is reduced with an mGluR1 but not mGluR5 antagonist (Dravolina et al., 2006) suggesting that the diminished mGluR1-LTP observed in the present study, may play a functional role in cocaine-induced neuroadaptations.

Additionally, a similar reduction in mGluR1-LTP was recorded in slices from animals sacrificed two days or fourteen days after their last cocaine injection suggesting that the change in mGluR1-induced LTP was not a function of cocaine withdrawal time.

Synaptic weighting contributes to reduction in mGluR1-LTP observed in the cocaine-withdrawn group

Our data showed that cocaine withdrawal shifted the dose dependent actions of PTX on DHPG-induced LTP in the BLA-CeLc pathway. The differences in mGluR1-LTP in slices from cocaine-withdrawn and saline-withdrawn groups were eliminated when the fEPSPs were recorded in either the absence of PTX or the presence of higher concentration of PTX (50 µM), indicating that the level of GABAergic inhibition is critical in tuning on and off synaptic plasticity in the amygdala. This finding suggested that the mechanism underlying the reduced mGluR1-LTP in slices from cocaine treated animals may be related to the balance of excitatory and inhibitory input in the amygdala complex.

Evidence suggests that DHPG can inhibit GABA release in various brain regions. DHPG depresses GABAergic transmission in the CA1 region (Chevaleyre & Castillo, 2003). MGluR1 but not mGluR5 antagonist blocked DHPG-induced reduction in GABAergic inhibitory currents via a presynaptic mechanism in cortico-striatal slices (Battaglia et al., 2001). In this study, we found that basal GABA inhibition was reduced in the amygdala after cocaine withdrawal, suggesting a malfunctioning synaptic modification occurred during the periods of cocaine withdrawal and cue associative learning processes. The diminished mGluR1-LTP recorded in CeLc GABAergic neurons after cocaine treatment would result in reduced GABA release onto the medial CeA output neurons which would ultimately enhance output of medial CeA to reward pathways, brainstem nuclei, or responses to cocaine cues. In our present study, the relative level of GABAergic inhibition behaves as a coincidence detector in which mGluR1-LTP in saline-treated and cocaine-withdrawn groups are not significantly different except when GABA inhibition was partially attenuated by 10 µM PTX, resulting in diminished mGluR1-LTP observed in the cocaine-withdrawn group. Early report showed that microinjections of previously ineffective dose of muscimol into the CeA decreased ethanol self-administration (Roberts et al., 1996). Therefore, the GABAergic system is likely to be altered to become more or less effective to PTX during the course of cocaine CPP and withdrawal. Furthermore, our data suggest that the relative balance between excitatory and inhibitory inputs, a form of synaptic scaling (Turrigiano, 1999), may be critical for detecting changes in mGluR1-LTP. In medial intercalated cells (ITCs), homosynaptic depression or potentiation can result in opposing heterosynaptic changes which result in conservation of total synaptic weight (Royer & Pare, 2003). Withdrawal from cocaine CPP reduced basal levels of GABAergic synaptic inhibition, leading to destabilize synaptic weighting, which becomes apparent when GABAergic inhibition is partially attenuated but not when fully present or absent. Our results are compatible with a mechanism involving malfunction in synaptic weighting of GABA inhibition, due to overall reduction in GABAergic tone indicated by decreased frequency and amplitude of mIPSCs, which in turn would contribute to cocaine-induced metaplasticity.

Furthermore, in naïve slices superfused with 10 µM PTX, DHPG at 100 nM or at 100 µM did not induce LTP or LTD. However the presence of LTP with 10 µM DHPG suggests that inhibitory synaptic tone may also influence the concentration-response relationship for DHPG. Thus, it is possible that fluctuating levels of eCB mobilization induced by the heterosynaptic nature of the BLA-CeLc pathway could contribute to the unusual DHPG-dose response relationship recorded in the naïve group and reduced mGluR1-LTP in cocaine-withdrawn group. However, LTP induced by exogenous CBs also showed deficits in the cocaine CPP group suggesting that eCB mobilization may not be involved in the mGluR1-LTP diminished in cocaine-withdrawn group but rather a malfunction of synaptic weighting due to overall reduction in GABAergic tone.

Diminished mGluR1-LTP after cocaine CPP was associated with an increase in CB receptor protein

The functional role of eCBs in cocaine addiction is ambiguous. Behaviorally, a CB1 antagonist does not block cocaine self-administration and eCBs levels in the NAcc are not altered during cocaine self-administration in rats (Caille et al., 2007), although after withdrawal CB1 receptor blockade attenuates relapse initiated by cocaine associated cues (De Vries et al., 2001). Cocaine self-administration is also unaffected in CB1 knock out mice (Martin et al., 2000) whereas other studies report cocaine self-administration is impaired in CB1 knock out mice and in wild type mice receiving CB1 antagonist (Soria et al., 2005). Conversely, CB1 agonists reduced behavioral sensitization to cocaine (Arnold et al., 1998) and the expression of CPP (Chaperon et al., 1998). Thus, studies which activate, inhibit, or remove CB1 receptors report contradictory findings on cocaine-induced behaviors.

In the present study, mGluR1-induced LTP in the saline-treated group was reduced by a CB1 antagonist indicating that eCBs normally function to enhance LTP in the BLA-CeLc pathway. Activating mGluR5 in the NAcc (Robbe et al., 2002) or mGluR1/5 together in the hippocampus (Chevaleyre & Castillo, 2003) releases eCBs. In the BLA, however, eCB-mediated LTD is heterosynaptic and required activation of mGluR1 (Azad et al., 2004) suggesting a similar effect may occur at GABAergic synapses in the CeLc.

In our study, when eCBs levels were increased by inhibition of hydrolysis or uptake, mGluR1-LTP was blocked in the saline-treated but not the cocaine-withdrawn group. In the LA and BLA, eCB formation reduces GABAergic inhibition (Katona et al., 2001), and decreasing GABAergic transmission in the LA increases excitatory transmission in the CeA (Azad et al., 2004). In the LA, CB1 agonist-induced inhibition of excitatory transmission prevails over its block of inhibitory transmission (Azad et al., 2003). In the BLA-CeLc pathway, increasing eCBs levels by blocking hydrolysis or uptake of eCBs cause inhibition of excitatory synapses, and this suggests that a threshold level of eCB concentration is needed to affect inhibition of excitatory synapses. This is consistent with findings in the hippocampus where inhibitory synapses are more sensitive to eCBs than excitatory synapses (Ohno-Shosaku et al., 2002). Importantly, since raising levels of eCBs did not reverse the cocaine-associated effects, it is unlikely that a deficit in eCB levels contributes to the diminished mGluR1-LTP in cocaine-treated group but rather a reduction in GABAergic transmission is involved.

Exogenously applied CB1 agonist induced a modest LTP in the saline-treated group. Thus it is likely that CB1 activation potentiated glutamatergic transmission through inhibition of GABAergic transmission. In contrast, the CB2 agonist reduced fEPSPs suggesting possible CB2-mediated inhibition of glutamatergic transmission.

CB1 receptors are highly expressed in the BLA but not the CeA where they are found primarily in GABA-like terminals (Katona et al., 2001; McDonald & Mascagni, 2001). A number of studies have looked at the role of eCBs and their receptors in modulation of synaptic transmission (Moreira & Lutz, 2008), where an apparent complexity in the function of this system is attributed to the specificity of their modulatory actions in different brain regions. The “set-point hypothesis” describes an equilibrium that is established by the endocannabinoid system to modulate excitatory and inhibitory responses (Moreira & Lutz, 2008). Although findings are dependent on brain area, the CB1 receptor as a modulator in cocaine behavioral effects is well established (Chaperon et al., 1998; Cossu et al., 2001; DeVries & Pert, 1998; Filip et al., 2006; Martin et al., 2000; Soria et al., 2005; Tanda et al., 2000; Xi et al., 2008). Recent studies report that neuronal CB2 receptors are also involved in drug abuse (Onaivi, 2006; Onaivi, 2008; Onaivi et al., 2008a; Onaivi et al., 2008b). In our study, CB1 and CB2 proteins are increased after two week withdrawal from cocaine CPP. As seen with psychiatric disorders (Manzanares et al., 2004), such a change in the receptor levels can alter the equilibrium of the set point and can lead to increased signaling. Our results suggested that eCB levels may be unaltered in the cocaine CPP group, but activating CB1 or CB2 receptors increased and decreased synaptic transmission, respectively, in the saline group. Thus, an increased number of CB receptors where existing eCBs bind may result in a decrease in GABAergic inhibition without requiring an increase in the eCB levels. The consequence of a decrease in GABAergic tone would therefore have indirect modulatory effects on mGluR1-LTP in the cocaine CPP group dependent on the level of GABAergic tone.

In summary, our data suggest that mGluR1-LTP was dependent on the balance of excitatory glutamatergic and inhibitory GABAergic transmission. The reduction in mGluR1-LTP observed in cocaine CPP is primarily due to a decrease in synaptic weighting of GABAergic transmission through an eCBs and CB receptor-mediated mechanism. These findings are important since the diminished mGluR-LTP in CeLc GABAergic neurons can reduce inhibitory input onto medial CeA projection neurons and ultimately result in a potentiated response to environmental cues, providing a unique scenario associated with psychostimulant addiction in the amygdala-based salience of drug effects. This enhanced response to environmental cues would in turn bias behavior toward drug-seeking.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Health Grant DA017727 to J. Liu and P. Shinnick-Gallagher, and by NRSA F32 Ruth L. Kirschstein postdoctoral grant DA023316 to B.K. We are grateful to Dr. Ken Mackie for the kind gift of the antibody against CB1 receptor. We thank Drs. Jose A. Morón and Joanne Cousins for review of the manuscript.

ABBREVIATIONS

- mGluRs

group I metabotropic glutamate receptors

- mGluR1-LTP

mGluR1-mediated long-term potentiation

- CPP

conditioned place preference

- ACSF

artificial cerebrospinal fluid

- BLA

basolateral amygdala

- CeA

central amygdala

- eCBs

endocannabinoids

- fEPSP

field excitatory post synaptic potential

- GABA

gamma amino butyric acid

- DHPG

(RS)-3,4-dihydroxyphenylglycine

- GPCR

G-protein coupled receptors

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartate

- CB1

cannabinoid receptor 1

- CB2

cannabinoid receptor 2

REFERENCES

- Arnold JC, Topple AN, Hunt GE, McGregor IS. Effects of pre-exposure and co-administration of the cannabinoid receptor agonist CP 55,940 on behavioral sensitization to cocaine. Eur.J.Pharmacol. 1998;354:9–16. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00433-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azad SC, Eder M, Marsicano G, Lutz B, Zieglgansberger W, Rammes G. Activation of the cannabinoid receptor type 1 decreases glutamatergic and GABAergic synaptic transmission in the lateral amygdala of the mouse. Learn.Mem. 2003;10:116–128. doi: 10.1101/lm.53303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azad SC, Monory K, Marsicano G, Cravatt BF, Lutz B, Zieglgansberger W, Rammes G. Circuitry for associative plasticity in the amygdala involves endocannabinoid signaling. J.Neurosci. 2004;24:9953–9961. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2134-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardo MT, Rowlett JK, Harris MJ. Conditioned place preference using opiate and stimulant drugs: a meta-analysis. Neurosci.Biobehav.Rev. 1995;19:39–51. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(94)00021-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia G, Bruno V, Pisani A, Centonze D, Catania MV, Calabresi P, Nicoletti F. Selective blockade of type-1 metabotropic glutamate receptors induces neuroprotection by enhancing GABAergic transmission. Mol.Cell Neurosci. 2001;17:1071–1083. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2001.0992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown EE, Fibiger HC. Differential effects of excitotoxic lesions of the amygdala on cocaine-induced conditioned locomotion and conditioned place preference. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1993;113:123–130. doi: 10.1007/BF02244344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caille S, Alvarez-Jaimes L, Polis I, Stouffer DG, Parsons LH. Specific alterations of extracellular endocannabinoid levels in the nucleus accumbens by ethanol, heroin, and cocaine self-administration. J.Neurosci. 2007;27:3695–3702. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4403-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaperon F, Soubrie P, Puech AJ, Thiebot MH. Involvement of central cannabinoid (CB1) receptors in the establishment of place conditioning in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1998;135:324–332. doi: 10.1007/s002130050518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevaleyre V, Castillo PE. Heterosynaptic LTD of hippocampal GABAergic synapses: a novel role of endocannabinoids in regulating excitability. Neuron. 2003;38:461–472. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00235-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childress AR, Mozley PD, McElgin W, Fitzgerald J, Reivich M, O'Brien CP. Limbic activation during cue-induced cocaine craving. Am.J.Psychiatry. 1999;156:11–18. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cossu G, Ledent C, Fattore L, Imperato A, Bohme GA, Parmentier M, Fratta W. Cannabinoid CB1 receptor knockout mice fail to self-administer morphine but not other drugs of abuse. Behav.Brain Res. 2001;118:61–65. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00311-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries TJ, Shaham Y, Homberg JR, Crombag H, Schuurman K, Dieben J, Vanderschuren LJ, Schoffelmeer AN. A cannabinoid mechanism in relapse to cocaine seeking. Nat.Med. 2001;7:1151–1154. doi: 10.1038/nm1001-1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVries AC, Pert A. Conditioned increases in anxiogenic-like behavior following exposure to contextual stimuli associated with cocaine are mediated by corticotropin-releasing factor. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1998;137:333–340. doi: 10.1007/s002130050627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domenici MR, Azad SC, Marsicano G, Schierloh A, Wotjak CT, Dodt HU, Zieglgansberger W, Lutz B, Rammes G. Cannabinoid receptor type 1 located on presynaptic terminals of principal neurons in the forebrain controls glutamatergic synaptic transmission. Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26:5794–5799. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0372-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dravolina OA, Danysz W, Bespalov AY. Effects of group I metabotropic glutamate receptor antagonists on the behavioral sensitization to motor effects of cocaine in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;187:397–404. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0440-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich I, Humeau Y, Grenier F, Ciocchi S, Herry C, Luthi A. Amygdala inhibitory circuits and the control of fear memory. Neuron. 2009;62:757–771. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filip M, Golda A, Zaniewska M, McCreary AC, Nowak E, Kolasiewicz W, Przegalinski E. Involvement of cannabinoid CB1 receptors in drug addiction: effects of rimonabant on behavioral responses induced by cocaine. Pharmacol.Rep. 2006;58:806–819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fourgeaud L, Mato S, Bouchet D, Hemar A, Worley PF, Manzoni OJ. A single in vivo exposure to cocaine abolishes endocannabinoid-mediated long-term depression in the nucleus accumbens. J.Neurosci. 2004;24:6939–6945. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0671-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraguti F, Conquet F, Corti C, Grandes P, Kuhn R, Knopfel T. Immunohistochemical localization of the mGluR1beta metabotropic glutamate receptor in the adult rodent forebrain: evidence for a differential distribution of mGluR1 splice variants. J. Comp Neurol. 1998;400:391–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutlerner JL, Penick EC, Snyder EM, Kauer JA. Novel protein kinase A-dependent long-term depression of excitatory synapses. Neuron. 2002;36:921–931. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01051-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grueter BA, Gosnell HB, Olsen CM, Schramm-Sapyta NL, Nekrasova T, Landreth GE, Winder DG. Extracellular-signal regulated kinase 1-dependent metabotropic glutamate receptor 5-induced long-term depression in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis is disrupted by cocaine administration. J.Neurosci. 2006;26:3210–3219. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0170-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzig V, Schmidt WJ. Effects of MPEP on locomotion, sensitization and conditioned reward induced by cocaine or morphine. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47:973–984. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katona I, Rancz EA, Acsady L, Ledent C, Mackie K, Hajos N, Freund TF. Distribution of CB1 cannabinoid receptors in the amygdala and their role in the control of GABAergic transmission. J.Neurosci. 2001;21:9506–9518. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-23-09506.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Vasseur M, Ran I, Lacaille JC. Selective induction of metabotropic glutamate receptor 1- and metabotropic glutamate receptor 5-dependent chemical long-term potentiation at oriens/alveus interneuron synapses of mouse hippocampus. Neuroscience. 2008;151:28–42. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.09.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Yu B, Neugebauer V, Grigoriadis DE, Rivier J, Vale WW, Shinnick-Gallagher P, Gallagher JP. Corticotropin-releasing factor and Urocortin I modulate excitatory glutamatergic synaptic transmission. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:4020–4029. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5531-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Hope BT, Dempsey J, Liu SY, Bossert JM, Shaham Y. Central amygdala ERK signaling pathway is critical to incubation of cocaine craving. Nat.Neurosci. 2005;8:212–219. doi: 10.1038/nn1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maejima T, Hashimoto K, Yoshida T, Aiba A, Kano M. Presynaptic inhibition caused by retrograde signal from metabotropic glutamate to cannabinoid receptors. Neuron. 2001;31:463–475. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00375-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manahan-Vaughan D, Reymann KG. Group 1 metabotropic glutamate receptors contribute to slow-onset potentiation in the rat CA1 region in vivo. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36:1533–1538. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00156-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzanares J, Uriguen L, Rubio G, Palomo T. Role of endocannabinoid system in mental diseases. Neurotoxicity Research. 2004;6:213–224. doi: 10.1007/BF03033223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin LJ, Blackstone CD, Huganir RL, Price DL. Cellular localization of a metabotropic glutamate receptor in rat brain. Neuron. 1992;9:259–270. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90165-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin M, Ledent C, Parmentier M, Maldonado R, Valverde O. Cocaine, but not morphine, induces conditioned place preference and sensitization to locomotor responses in CB1 knockout mice. Eur.J.Neurosci. 2000;12:4038–4046. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald AJ, Mascagni F. Localization of the CB1 type cannabinoid receptor in the rat basolateral amygdala: high concentrations in a subpopulation of cholecystokinin-containing interneurons. Neuroscience. 2001;107:641–652. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00380-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meil WM, See RE. Lesions of the basolateral amygdala abolish the ability of drug associated cues to reinstate responding during withdrawal from self-administered cocaine. Behav.Brain Res. 1997;87:139–148. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(96)02270-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millhouse OE. The intercalated cells of the amygdala. J. Comp Neurol. 1986;247:246–271. doi: 10.1002/cne.902470209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira FA, Lutz B. The endocannabinoid system: emotion, learning and addiction. Addict.Biol. 2008;13:196–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ. Neurobiology. Total recall-the memory of addiction. Science. 2001;292:2266–2267. doi: 10.1126/science.1063024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno-Shosaku T, Tsubokawa H, Mizushima I, Yoneda N, Zimmer A, Kano M. Presynaptic cannabinoid sensitivity is a major determinant of depolarization-induced retrograde suppression at hippocampal synapses. J.Neurosci. 2002;22:3864–3872. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-10-03864.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onaivi ES. Neuropsychobiological evidence for the functional presence and expression of cannabinoid CB2 receptors in the brain. Neuropsychobiology. 2006;54:231–246. doi: 10.1159/000100778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onaivi ES. An endocannabinoid hypothesis of drug reward and drug addiction. Ann.N.Y.Acad.Sci. 2008;1139:412–421. doi: 10.1196/annals.1432.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onaivi ES, Ishiguro H, Gong JP, Patel S, Meozzi PA, Myers L, Perchuk A, Mora Z, Tagliaferro PA, Gardner E, Brusco A, Akinshola BE, Hope B, Lujilde J, Inada T, Iwasaki S, Macharia D, Teasenfitz L, Arinami T, Uhl GR. Brain neuronal CB2 cannabinoid receptors in drug abuse and depression: from mice to human subjects. PLoS.ONE. 2008a;3:e1640. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onaivi ES, Ishiguro H, Gong JP, Patel S, Meozzi PA, Myers L, Perchuk A, Mora Z, Tagliaferro PA, Gardner E, Brusco A, Akinshola BE, Liu QR, Chirwa SS, Hope B, Lujilde J, Inada T, Iwasaki S, Macharia D, Teasenfitz L, Arinami T, Uhl GR. Functional expression of brain neuronal CB2 cannabinoid receptors are involved in the effects of drugs of abuse and in depression. Ann.N.Y.Acad.Sci. 2008b;1139:434–449. doi: 10.1196/annals.1432.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Robbe D, Kopf M, Remaury A, Bockaert J, Manzoni OJ. Endogenous cannabinoids mediate long-term synaptic depression in the nucleus accumbens. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2002;99:8384–8388. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122149199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AJ, Cole M, Koob GF. Intra-amygdala muscimol decreases operant ethanol self-administration in dependent rats. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1996;20:1289–1298. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano C, Sesma MA, McDonald CT, O'Malley K, van den Pol AN, Olney JW. Distribution of metabotropic glutamate receptor mGluR5 immunoreactivity in rat brain. J.Comp Neurol. 1995;355:455–469. doi: 10.1002/cne.903550310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royer S, Martina M, Pare D, Royer S, Martina M, Pare D. An inhibitory interface gates impulse traffic between the input and output stations of the amygdala. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:10575–10583. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-23-10575.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royer S, Pare D. Conservation of total synaptic weight through balanced synaptic depression and potentiation. Nature. 2003;422:518–522. doi: 10.1038/nature01530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaham Y, Hope BT. The role of neuroadaptations in relapse to drug seeking. Nat.Neurosci. 2005;8:1437–1439. doi: 10.1038/nn1105-1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soria G, Mendizabal V, Tourino C, Robledo P, Ledent C, Parmentier M, Maldonado R, Valverde O. Lack of CB1 cannabinoid receptor impairs cocaine self-administration. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:1670–1680. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun N, Cassell MD. Intrinsic GABAergic Neurons in the Rat Central Extended Amygdala. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1993;330:381–404. doi: 10.1002/cne.903300308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson CJ, Baker DA, Carson D, Worley PF, Kalivas PW. Repeated cocaine administration attenuates group I metabotropic glutamate receptor-mediated glutamate release and behavioral activation: a potential role for Homer. J.Neurosci. 2001;21:9043–9052. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-22-09043.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanda G, Munzar P, Goldberg SR. Self-administration behavior is maintained by the psychoactive ingredient of marijuana in squirrel monkeys. Nat.Neurosci. 2000;3:1073–1074. doi: 10.1038/80577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrigiano GG. Homeostatic plasticity in neuronal networks: the more things change, the more they stay the same. Trends Neurosci. 1999;22:221–227. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01341-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volk LJ, Daly CA, Huber KM. Differential roles for group 1 mGluR subtypes in induction and expression of chemically induced hippocampal long-term depression. J.Neurophysiol. 2006;95:2427–2438. doi: 10.1152/jn.00383.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi ZX, Spiller K, Pak AC, Gilbert J, Dillon C, Li X, Peng XQ, Gardner EL. Cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonists attenuate cocaine's rewarding effects: experiments with self-administration and brain-stimulation reward in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:1735–1745. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]