Abstract

The amount of light absorbed and scattered by neocortical tissue is altered by neuronal activity. Imaging of intrinsic optical signals (ImIOS), a technique for mapping these activity-evoked optical changes with an imaging detector, has the potential to be useful for both clinical and experimental investigations of the human neocortex. However, its usefulness for human studies is currently limited because intraoperatively acquired ImIOS data is noisy. To improve the reliability and usefulness of ImIOS for human studies, it is desirable to find appropriate methods for the removal of noise artifacts and its statistical analysis. Here we develop a Bayesian, dynamic linear modeling approach that appears to address these problems. A dynamic linear model (DLM) was constructed that included cyclic components to model the heartbeat and respiration artifacts, and a local linear component to model the activity-evoked response. The robustness of the model was tested on a set of ImIOS data acquired from the exposed cortices of six human subjects illuminated with either 535 nm or 660 nm light. The DLM adequately reduced noise artifacts in these data while reliably preserving their activity-evoked optical responses. To demonstrate how these methods might be used for intraoperative neurosurgical mapping, optical data acquired from a single human subject during direct electrical stimulation of the cortex were quantitatively analyzed. This example showed that the DLM can be used to provide quantitative information about human ImIOS data that is not available through qualitative analysis alone.

1. Introduction

The amount of light absorbed and scattered by brain tissue changes in response to neuronal activity (Cohen, 1973; Grinvald et al., 1988; Hochman, 1997). Such activity-evoked optical responses are often called “intrinsic optical signals” (IOS) since they arise from changes in the optical properties of the tissue itself, and do not require the application of dyes. Imaging of intrinsic optical signals (ImIOS) refers to any technique that involves illuminating neuronal tissue with light at various wavelengths, and acquiring sequences of images to map the spatial and temporal changes in its IOS. IOS recorded from the surface of the intact neocortex are thought to be predominantly due to two types of hemodynamic events: i) changes in blood volume, mediated by activity-evoked dilation of the pial arterioles near firing neurons, and ii) changes in the oxygen content of blood within the venous network associated with active cortical regions (Haglund and Hochman, 2007; Malonek and Grinvald, 1996; Zhao et al., 2007). Since ImIOS is capable of quantifying the optical changes occurring within distinct microvascular compartments and tissue regions, it is well suited for studying hemodynamics on the exposed cortical surface of human subjects during neurosurgical procedures.

Current interest in refining the intraoperative ImIOS technique is motivated by at least two reasons. First, this technique provides a means for addressing basic scientific questions regarding the physiology of cerebral hemodynamics associated with normal and epileptic activity in the human brain. Second, optical imaging has the potential to be a practical clinical tool for localizing functional and epileptic cortical regions in the operating room, providing guidance for the resection of tissue during neurosurgical procedures (Haglund and Hochman, 2004). A major hindrance in using ImIOS for these purposes is that intraoperatively acquired optical data is typically contaminated with large noise artifacts from respiration, heartbeat, and other sources (Figure 1). It is therefore desirable to develop practical techniques for analyzing human ImIOS data that address two issues: i) the removal of unwanted artifacts from the underlying optical changes of interest with some estimate of the uncertainty associated with the results, and ii) to provide a framework for statistical analysis of the optical data.

Figure 1. Characteristics of Optical Imaging Data at 535 nm and 660 nm.

A pseudo-colored map of the electrical stimulation-evoked optical changes over the cortical surface at 535 nm (panel A) shows that the largest changes occur in the tissue surrounding the stimulating electrodes (“S”, panel B). Visual comparison of the optical changes in panel A to the positions of the larger vessels identifiable in panel B shows that the activity-evoked optical changes at 535 nm are absent from such vessels. The largest optical changes at this wavelength are negative-going, showing a decrease in light absorption when compared to pre-stimulus conditions. In contrast to the changes at 535 nm, the largest optical changes at 660 nm (panel C) are restricted to one or more of the larger veins and are positive-going. Optical imaging data is analyzed by selecting at least nine regions of interest, each one consisting of approximately 5000 pixels, covering an area of 20 mm2.

Regions are selected over tissue areas from which larger vessels were absent (blue circles, panel B), or from segments overlying larger veins in which activity-evoked signals are observed to occur at 660 nm (red overlays, panel B). Time series of these optical data (blue and red plots, panels D and E) are generated by calculating the percent change (relative to a control image) of the average of the pixel values within each region for every image in an experimental trial. ECoG recordings (green traces, panels D and E) from surface electrodes (marked “R” in panel B) were simultaneously acquired with the optical data so that the timing of the electrical stimulus relative to the changes in the optical signal could be accurately determined from the stimulus-artifact, and to monitor for the presence of afterdischarges and spontaneous activity. Time series for regions from which the largest activity-evoked optical changes were elicited at 535 nm (Region 1; blue traces) and at 660 nm (Region 9; red traces) are shown in panels D and E. These plots show patterns of noise occurring at both wavelengths that include larger spikes with a period of approximately 5s due to respiration, along with smaller spikes with a period of 0.8 s due to heartbeat. The inset in the bottom left of panel D shows a smaller section of the 535 nm optical signal plotted at a slower time course and larger scale. Note that the amplitude and duration of each respiration and heartbeat artifact can vary between cycles. The optical response of Region 9 overlying the vein at 660 nm shown in panel E (red trace) is more complicated than the 535 responses of the tissue shown in panel D, with the shape of the initial response and the magnitude of the later fluctuations about the baseline difficult to accurately discern in the presence of the respiration and heartbeat artifacts.

A number of quantitative methods have been described for the analysis of optical data acquired under laboratory conditions from various animal species (Bathellier et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2007; Gabbay et al., 2000; Grinvald et al., 1988; Haglund and Hochman, 2007; Myers et al., 2007; Schiessl et al., 2000, 2008). However, it is not known how comparable the signal and noise characteristics of these animal data are to those of human data acquired in the operating room, and methods developed for the analysis of animal data may not work well for human data. For example, the noise artifacts in primate data acquired in our laboratory can be filtered using standard techniques that would not be adequate for denoising our human data (see Figure 6). A number of human intraoperative ImIOS studies have also applied various analysis methods (see, for example, (Cannestra et al., 2001; Haglund et al., 1992; Haglund and Hochman, 2004; Sato et al., 2002, 2005; Schwartz et al., 2004)). However, there has not yet been an effort aimed at developing a statistical model that accounts for the various noise artifacts and optical responses that are typical of intraoperatively acquired human data, and testing the robustness of such a model on a number of different data sets. We take these first steps here by developing a Bayesian, dynamic linear model for the analysis of human ImIOS data (Petris et al., 2009; West and Harrison, 1989), and verifying its robustness on data sets derived from multiple replicates and cortical regions from multiple subjects.

Figure 6. Primate and Human Signals for Testing Accuracy of Model 2.

Primate optical data showing a response to an electrical stimulus was combined with human data containing respiration and heartbeat artifacts (and no activity-evoked response) to test the accuracy of Model 2. Heartbeat artifacts can be removed from primate data using a running-mean filter of window-length 7 (covering about 1s of the time series at the frequency in which these data were acquired), without significantly altering any changes occurring at a lesser frequency in the raw data. The trace showing the largest optical response in the top panel illustrates this processing. The raw data is plotted as a black trace in which the high-frequency heartbeat artifact can be seen. The mean-filtered time series derived from the raw data is plotted as an overlying red trace. Four other similarly smoothed time series acquired from the primate are shown, chosen from regions at various distances from the stimulating electrode so that a variety of responses with different magnitudes and durations could be tested. Each of these time series was acquired with the application of four seconds of electrical stimulation to the cortex beginning at t = 20s. The noisy human data to be combined with each of the traces in the top panel is shown in the bottom panel (black trace). The estimated level component of this noisy trace given by Model 2 is overlaid as a red trace (thick line) with its 90% CIs (thinner lines), showing that only small fluctuations around the baseline are present in its linear trend.

Dynamic linear models (DLMs) are commonly used for the analysis of time series data where it is desirable to have a model with time-varying parameters (Aguilar et al., 1999; West and Harrison, 1989; West et al., 1999). Each of the various time-evolving components that may contribute to a time series can be directly represented in a DLM as sub-models. This seems to be a natural approach for dealing with intraoperatively acquired optical data. It is clear that raw ImIOS data has contributions from heartbeat and respiration cycles whose waveforms vary in time (i.e. their shapes and durations can vary from cycle to cycle), with an underlying smooth trend in which transient changes occur in response to neuronal activity (see Figure 1). One can build a DLM with each of these components explicitly represented that can then be used to estimate their time-varying parameters and variances, and that provides a useful framework for making statistical inferences about the optical data. Our goal here is to construct a DLM that accurately estimates each distinct component that appears to be present in the raw data so that the component of primary interest, the underlying local linear trend that contains information about the activity-evoked optical responses, can be reliably estimated with a credible interval (CI) as a measure of the associated uncertainty.

The work presented here is a methods study, focused on developing a specific statistical model, and demonstrating its use for analyzing ImIOS data. Rather than stating the final form of a useful DLM and beginning our study from that point, the development of the model is done in two steps. First, a simple DLM (Model 1) is developed and its results for two time series are analyzed. Second, a more complicated model (Model 2) is developed to address the shortcomings of the first model, and an analysis is provided comparing these two DLMs. This is done to demonstrate how DLMs of optical imaging data can be modified and compared. Although the specific DLM that we find to be useful for modeling our data might not be suitable for modeling all optical imaging data, our general modeling strategy can serve as a guide for modifying the DLM developed here to be better suited for other data sets. Data acquired at 535 nm is used to test our model, since some evidence suggests this wavelength is specific for detecting changes in the dilating pial arterioles near firing neurons, and hence may be more accurate than other wavelengths for localizing neuronal activity (Haglund and Hochman, 2004). We also describe some limited testing of our model on ImIOS data acquired 660 nm, a wavelength thought to be specific for detecting oxygenation changes localized to the venous network (Haglund and Hochman, 2004, 2007; Malonek and Grinvald, 1996) (also, see Figure 1).

2. Material and methods

2.1. Human Subjects and Intraoperative Maintenance

Intraoperative optical imaging data were acquired from the exposed cortices of six adult subjects (2 males, 4 females) who were undergoing surgical treatment for medically intractable epilepsy. All patients had given informed consent to participate in these studies that followed a protocol approved by the Duke University Health System Institutional Review Board (Pro00013993). Patients remained on their preoperative AEDs at the time that optical imaging data was acquired. Data was acquired while the patients were either awake, or anesthetized with inhalational isoflurane (0.2 MAC) and intravenous remifentanil and propofol. Propofol was administered up until 10 min prior to the recording session at which point propofol administration was stopped and not re-administered until the recording session had ended. Additionally, a local field block was administered consisting of 1.0% lidocaine with 1:200,000 epinephrine and 0.25% marcaine with 1:200,000 epinephrine mixed 1:1. The lidocaine/marcaine/epinephrine solution (9 ml) was mixed with a NaHCO3 solution (1 ml) for the field block. ital signs were monitored so that variables, such as blood pressure, blood oxygen saturation, and arterial CO2 (PaCO2 = 35–39 mmHg) and PO2 were as close as possible between experiments.

2.2. Electrocorticography (ECoG) recording

EEG activity recorded by EEG electrodes placed directly on the cortical surface was continuously monitored throughout the studies. The electrode array (Ad-Tech Medical Instrument, WI) was recorded on paper by an analog EEG machine equipped with signal amplifiers and noise filters (Grass, RI); the EEG recordings from some studies were passed to an A/D converter (Digidata 1440a, Molecular Devices, CA) and recorded as a digital signal on a PC desktop computer for further offline anlysis. ECoG recordings were acquired from at least seven electrodes in an array covering a 5 × 5 cm2 area of the cortical surface from which optical imaging data was acquired. An eighth input to the amplifier received pulses from the camera used for optical imaging experiments so that the timing of each image acquisition could be precisely matched to the electrophysiological activity and stimulation artifacts. A silver-ball reference electrode was placed on the contralateral mastoid process. For EEG data that was digitized, all eight channels were digitized at 14-bit resolution at 1000–5000 samples/s per channel.

2.3. Electrical stimulation of cortex

A bipolar stimulating electrode (5 mm inter-electrode distance), powered by a constant-current source (Ojemann Cortical Stimulator, Integra Life Sciences), was placed on the neocortex and used for all stimulation studies. The minimal stimulation current (4 s at 60 Hz, 1-ms biphasic pulse) required to elicit at least 5 s of afterdischarge activity was determined at the start of each study. One EEG recording electrode was placed directly between the stimulating electrodes for detecting the presence of afterdischarge activity. Only non-essential cortical areas that had first been identified for surgical resection were electrically stimulated.

2.4. Optical imaging

The intraoperative optical imaging technique used in these studies was similar to what has previously been reported (Haglund et al., 1992). A 4 × 4-cm glass plate was gently placed on the cortical surface to reduce movement artifacts from respiration and heartbeat, and to prevent reflectance changes caused by evaporation of moisture from the cortical surface. A microscope (Leica MZ15A Zoom Stereo Fluorescence Microscope) was attached to a steel post mounted on the operating table. The cortex was uniformly illuminated by passing light through a dedicated beam path on the microscope. Light was provided by a 100W highly-regulated xenon source (“The Nobska”, Opti-Quip Inc., NY) and was passed through 535nm or 660 nm optical filters (+/−10nm for each filter). The optical filters were held by a computer-controlled filter-wheel (MAC5000, Ludl Electronics, NY) so that optical wavelengths could be switched during the experiment. Images were acquired by a 14-bit, cooled, digital camera (Versarray XP:512B, Roper Scientific Inc, NJ) fitted with a 512×512 CCD chip having with a 24×24 micron pixel size. Sequences of images were integrated over 200-ms intervals and stored on hard disk for off-line analysis. During each stimulation trial, 400–600 images were acquired.

To visually demonstrate the spread of stimulation-evoked optical changes over the cortex, “difference images” were generated by subtracting a randomly chosen pre-stimulation image (i.e. control image), acquired during a 10 s interval prior to stimulation, from all of the images in its associated series. Each difference image thus represented the absolute change in the optical signal from the chosen control image. The difference images were then divided by the control image to provide a map of percentage change. To make small changes more apparent, the images were pseudo-colored with a “spectrum” lookup table. For qualitative analysis of the optical images, high-frequency noise was removed by applying a Gaussian low-pass filter to the images to improve appearance; such processing was not observed to significantly affect the spatial features of the optical maps as compared with the raw, unprocessed images.

For quantitative analysis with DLMs, time series were extracted from the raw sequences of optical images as described in Section 3.1, after the images were registered to reduce motion artifacts. The image registration algorithm consisted of spatially translating each image in a series, 1 pixel at a time, in all directions (up, down, left, and right), and choosing the translate that minimized the variance of the difference between the translated image and the image acquired immediately prior to the onset of stimulation, or to the image acquired at t = 10 s for series in which no stimulus was applied.

2.5. Primate optical imaging

Several of the optical time series used for the analysis presented in Figures 6 and 7 were obtained from anesthetized primates (n = 2). The details of the treatment and preparation of primates for optical imaging studies have been previously described (Haglund et al., 1993). Macaque monkeys (Macaca nemestrina) were used, with their care and treatment conforming to a protocol approved by Duke’s Institutional Animal Care & Use Committee. To allow for imaging and electrophysiological recordings from the neocortex, a 25mm craniectomy over hand motor cortex was performed and a specially designed 25 mm threaded stainless steel chamber was mounted to the cranium to provide an “optical window.” For electrical stimulation of the cortex, a bipolar stimulating electrode (5 mm inter-electrode distance) powered by an Ojemann Cortical Stimulator was placed on the neocortical surface. The cortical stimulator, optical imaging equipment and data analysis methods used to generate the primate data presented here were identical to what was used for human subjects, described above.

Figure 7. Accuracy of Model 2 in Recovering Activity-evoked Optical Responses.

The noisy human data containing heartbeat and respiration artifacts were combined with each of the five primate noise-free time series from the previous figure. The estimated level components given by Model 2 for each of these combined time series were then plotted in panels 1–5. Each panel shows the estimated levels and their 90% CI (black traces), with the original ‘true data’ overlaid (red trace), for each of the combined series. The plots in each panel are drawn at different scales determined by the minimum and maximum values of the individual time series. The primate data for panel 5 contains a small ‘wiggle’ during its peak response that is lost in the estimated level component. To understand the reason for this loss of accuracy, the combined [human noisy + primate] time series (black trace) is compared to the true signal (red trace) and the estimated level component (blue trace) in panel 6. It is apparent that the wiggle in the true data coincidentally is of a similar shape as the respiration cycles.

2.6. Modeling Software

The R language and statistical computing environment was used for all statistical analysis, implementation of models, and the generation of plots used in the figures. R is a free, open source software package (http://www.r-project.org/). The dynamic linear models were implemented using the freely available dlm package written for R by G. Petris (http://cran.r project.org/web/packages/dlm/index.html) that is described in detail by its documentation and in a recently published book (Petris et al., 2009).

3. Results

3.1. Modeling Strategy

The raw optical data studied here consists of series of digitized video images acquired from cortical surfaces that were illuminated with either 535 nm or 660 nm light. Each image-series is comprised of a sequence of several hundred images that were acquired continuously over a 1–3 minute interval, typically at a rate of 5 images/second, with integration times of 200 ms/image. The first 10–20 seconds of each image-series represents a ‘control’ period prior to the application of a stimulus. A stimulus, such as 4 seconds of electrical stimulation or 10 seconds of tongue sensory-motor activation, was then used to elicit cortical activity, followed by a recovery period of 1–2 minutes. A set of nine regions of interest (ROIs) was selected for each image-series, each ROI covering a cortical area of approximately 25 mm2 (approximately 2000 pixels). The ROIs were selected to be in approximately the same locations relative to the stimulating-electrodes between different subjects, with seven ROIs chosen to overlie tissue regions that were free of large vessels and two ROIs overlying blood vessels that underwent the largest optical changes at 660 nm, as determined by visual examination of the pseudocolored difference-images acquired while imaging with 660 nm light (Figure 1; top). Time series corresponding to each of the ROIs were then generated by calculating the average pixel value within each ROI for every image within an image-series. Because of the variations in the illumination profile across the field of view, time series for each region were normalized by calculating their average values during the control period, and subtracting then dividing the value at each time point of the time series by this average value and multiplying by 100. The value at each time point in a time series then represents the average percent change in the optical signal within a ROI with respect to a baseline that has an average value of zero during the control period (Figure 1, bottom). All subsequent analyses and modeling were performed on the normalized time series. Thus we work with data of the form:

The main features of the time series that can be observed from plots with a slower time scale (Figure 1, bottom), and that we wish to incorporate into our model are:

A higher frequency cyclic component due to heartbeat that has a period of 2–4 time points.

A slower cyclic component due to respiration that typically has a period of 15–25 time points.

Dips or rises in some regions that represent the responses, or the activity-dependent changes in the optical signal.

Different variability in different regions

Our modeling goals are to identify the optical changes occurring within regions that are due to changes in neuronal activity and to determine the characteristics of those changes. To accomplish this, our model will be required to account for the cyclic components attributed to heartbeat and respiration, and for the other features that are extraneous to the response. Our approach will be to construct a model along the lines of

| (1) |

where st is a smooth local fit meant to capture the response, ht is for heartbeat, rt is for respiration, other termst is for other terms that may need to be added (other termst are not needed in this paper but are needed, for example, for patients whose data have an additional quasi-cyclic component, as described in the Discussion section 4.1.), and υt is an error term. Each of these terms is to be modeled separately for each region. The class of state-space models, or dynamic linear models (DLMs) is well suited for this purpose. A brief sketch is provided here of the ideas that will be used in what follows, but complete descriptions of DLMs can be found in the literature (Petris et al., 2009; West and Harrison, 1989).

DLMs are used for modeling systems that evolve over time. At time t, the system is represented by a vector of parameters θt = (θ1,t, …, θn,t)t called the state of the system. A DLM has a state or evolution equation that describes how θt+1 depends on θt and an observation equation that describes how the observation at time t depends on θt. Complicated systems, such as ours, can be modeled by combining simpler DLMs for the individual components st, ht, and rt.

We model st as locally linear. At each time t ∈ {0, 1, …, T}, the state of the system is represented by its level and slope, so that is the state vector. The state equation is

| (2) |

where the w’s (representing random noise) are mean-zero Gaussian errors. The presence of noise means that the slope can change over time. Only levelt, not slopet, contributes to what we observe at time t. Thus the observation equation is

| (3) |

The linear model part of the name DLM arises because the left-hand and right-hand parts of Equations (2) and (3) have the form Y = Xβ + ε where, in Equation (2) for example, Y = (levelt+1, slopet+1)t, , β = (levelt, slopet)t, and ε = (0,wslope,t+1)t. (There is no error term in Eq. (3) because it will be absorbed by υt in Eq (1).) The dynamic part of the name arises because β = (levelt, slopet)t changes over time.

We model the quasi-cyclic components ht and rt with trigonometric DLMs. An exactly sinusoidal function can be thought of as a point moving around a circle; its location at time t is given by (b cos αt, b sin αt) where b is its distance from the origin and αt is its angle. If its period is p, then in one time-step it changes its angle by δ = 2π/p and its location at t + 1 is

Our DLMs for ht and rt adopt the previous equation plus additive noise. Thus, for heartbeat, the state vector is . The state equation is

| (4) |

where the w’s are mean-zero, Gaussian errors. The presence of noise means that need not equal and that need not equal . Thus the model can accommodate functions that are not exactly sinusoidal and whose period and amplitude change over time. The observation equation is

A similar DLM is adopted for respiration, but with superscript r.

Combining the individual DLMs for st, ht, and rt (still omitting subscripts for regions) represents Eq. (1) as a DLM with a six-dimensional θt whose state and observation equations are given by

| (5) |

Throughout, we perform Bayesian analysis of the DLM in Eq. (5), with the following prior distributions for values at time t = 0 and for errors.

(A brief investigation, not reported here, showed that our posterior distributions are not highly sensitive to the choice of prior.) In DLM analysis, the posterior distributions of the state variables {θt} can be computed exactly, conditional on V, Ws, Wh, and Wr. But for the joint posterior distribution of all parameters we use Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC), for which many good references are available, including (Besag et al., 1995; Liu, 2003; Robert and Casella, 2004).

3.2. First Application

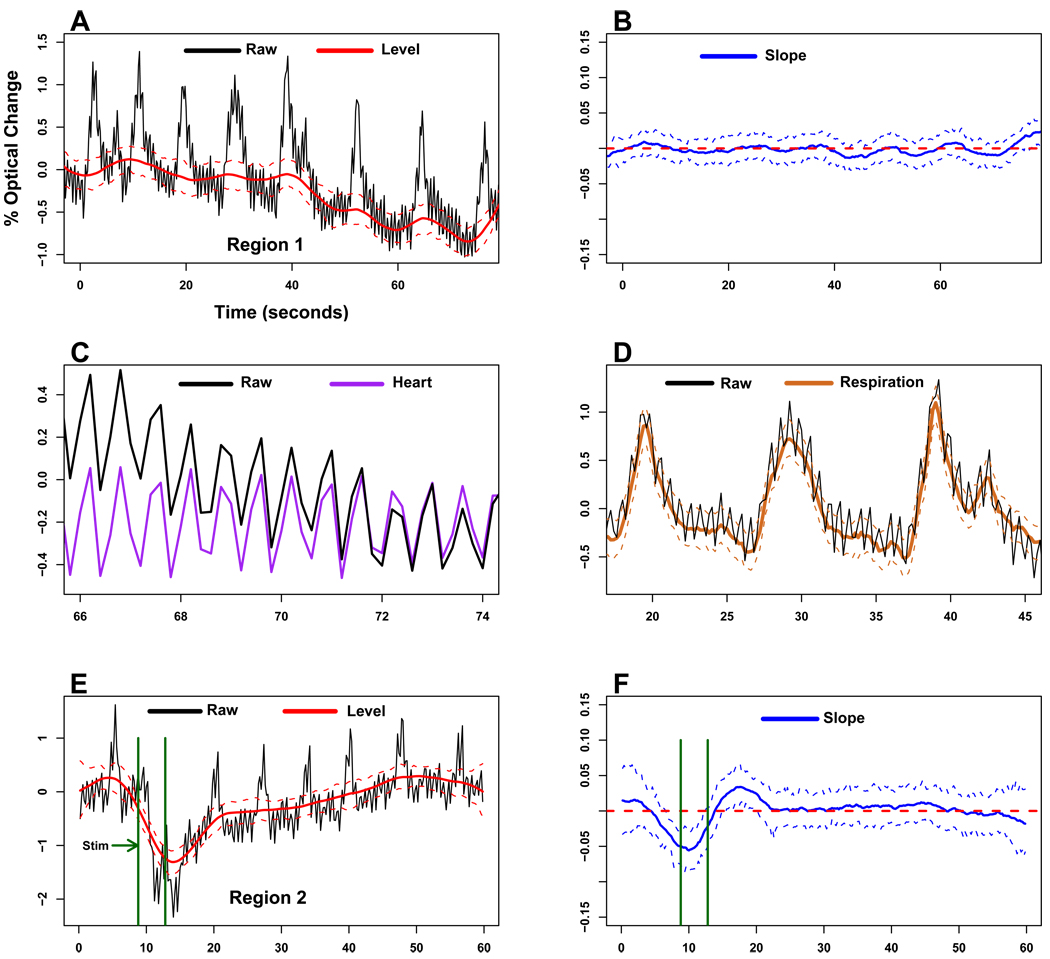

We begin by studying the results of this model, Model 1, applied separately to each of a small number of representative time series acquired with 535 nm light, with the hope that the model will be generally applicable. Two such representative time series, Region 1 and Region 2, are shown in Figure 2 (for all panels in Figures 2 and 3, raw data is plotted using solid black lines, estimated components with solid colored lines, and the CIs for the estimated components as dashed lines). Region 1 (Figure 2, panel A) is a time series in which no stimulus was given, and Region 2 (Figure 2, panel E) is one which shows a small response of approximately 1–2% to an electrical stimulus.

Figure 2. Results of Model 1.

The accuracy of the first DLM, Model 1, is assessed here by examining how well its estimated level, heartbeat, and respiration components match those of the real optical data. For this purpose, two time series of 530 nm optical data were chosen for analysis: Region 1 (panel A, black trace), from a control-experiment in which no electrical stimulus was given, and Region 2 (panel E, black trace), in which a small optical response (< 2%) appeared to be elicited by the stimulation that was applied from t = 8.8s to t = 12.8s (green vertical bars, panels E and F). Since no stimulus was applied to Region 1, the estimated level (linear trend) would be expected to be relatively flat, with perhaps some drift around the baseline value. However, the estimated level component for Region 1 (panel A, solid red line with 90% CIs shown as dotted red lines) appears to closely follow the respiration cycles. The estimated slope (i.e. rate of change, or derivative) of the level component for Region 1 (panel B, solid blue trace with 90% CIs plotted as dotted lines; dashed red line indicates where the slope is unchanging) confirms that significant changes are occurring with the estimated level component that coincide with the rising and falling of each respiration cycle. To study the accuracy of Model 1’s estimation of the heartbeat, the estimated heartbeat component and the raw data are plotted together at a slower time course and magnified scale (panel C; purple trace is the estimated heartbeat, black trace is raw data; CIs not shown for clarity). A similar plot comparing the model-estimated respiration component to the raw data is shown in panel D (solid brown trace is estimated respiration with 90% CIs shown as dotted lines, black trace is raw data). The respiration artifacts in the estimated level component and slope for Region 2 (panels E, F) similarly suggest that Model 1 does not accurately estimate the respiration component. The changes in the optical response elicited by the stimulus are not obviously distinguishable from the respiration artifacts in the slope (panel F).

Figure 3. Results of Model 2.

Model 2 was constructed by modifying Model 1 to included an additional harmonic for the respiration component, while keeping all other details of Model 1 unchanged. The same time series that were analyzed in Figure 2 with Model 1 are again analyzed here with Model 2 (raw data plotted in panels A and E as black traces). The estimated level curves (panels A and E, solid red traces; 90% CIs indicated by dotted lines) have greatly reduced heartbeat and respiration artifacts. The estimated slope for Region 1 which was acquired during control conditions in which there was no electrical stimulation is relatively flat with small fluctuations around baseline (panel B; solid blue trace; 90% CIs indicated by dotted lines; red dashed line indicates where the slope is unchanging). Comparison of the estimated respiration component (panel D; brown trace) to the raw data (panel D; black trace) shows that Model 2 appears to accurately capture the complex shapes of the varying respiration cycles. The small optical response elicited by electrical stimulation in Region 2 is now evident (panel E, red traces), and its corresponding slope (panel F, blue traces; dashed red line indicates where the slope is unchanging) now shows a clear deviation from the baseline during the onset and recovery of the optical response to the stimulus.

The level component estimated by the DLM (Figure 2, panel A, red traces) closely follows the shapes of the respiration cycles within the raw data (black trace). This demonstrates that Model 1 does not accurately separate the cyclic respiratory components from the linearly varying level component. The estimated slope (Figure 2, panel B, blue traces; red dashed line indicates where the slope is zero) also shows periodic changes due to respiration. The estimated heart component (Figure 2, panel C, purple trace; CIs not drawn for clarity) appears to accurately model the characteristics of the true heartbeat present in the raw data (Figure 2, panel C, black trace). The estimated respiration component (Figure 2, panel D, brown traces) appears to be a simple sinusoid that does not well model the more complex shaped respiratory cycles. The second time series, Region 2, (Figure 2, panel E) was acquired from the same patient with 4 seconds of cortical stimulation, from t = 8.8s to t = 12.8s (green vertical lines show the time interval during which the stimulus was applied). Similar to Region 1, the Region 2 level component (Figure 2, panel E, solid red traces) closely follows the respiratory cycles present in the raw data. The stimulation-evoked changes for this region are not obviously discernible in the estimated slope for this region (Figure 2, panel F, blue traces).

The results shown in Figure 2 indicate that Model 1 sufficiently accounts for the heartbeat artifact, but does not adequately model the respiratory and locally linear components. Additionally, the estimated respiration component has the appearance of a simple sine wave. This suggests that Model 1 might be improved upon by including a more flexible family of shapes for rt, the respiration component. To that end, we construct a slightly more complicated model, Model 2, that includes two harmonics for the respiration component. Such terms are included in a DLM by four parameters at each time t:

with state and observation equations given by

| (6) |

where the w’s are mean-zero Gaussian errors. Our second model, Model 2, is the same as Model 1 except that rt follows Eq (6) rather than Equation (4). Model 2 has, at each time t, eight parameters: two parameters for st, two for ht, and four for rt.

Figure 3 shows the results of the analysis of Regions 1 and 2 with Model 2. The level for Region 1 (Figure 3; panel A, red traces) now appears to follow the drift around baseline and has greatly reduced respiration artifacts in comparison to Model 1. Its slope (Figure 3, panel B, blue traces; red dashed line indicates where the slope is unchanging) shows little variation, as it should since there was no stimulation-evoked activity occurring during this trial. The estimated respiration component (Figure 3, panel D, brown traces) now appears to accurately follow the shapes of the respiratory cycles within the raw data (Figure 3, panel D, black trace). The level for Region 2 (Figure 3; panel E, red traces) clearly shows a response that is correlated in time to the onset and cessation of the stimulus (green vertical lines), and its slope (Figure 3, panel F, blue traces) shows a significant change associated with the stimulus that is clearly identifiable. These results suggest that Model 2 may be an appropriate DLM to use for analysis of these data, capable of greatly reducing the heartbeat and respiration artifacts while preserving relatively small stimulation-evoked responses in the optical signal.

3.3. Fourier Analysis of the Results Given by Model 1 and Model 2

Further insight into our modeling approach and the differences between Model 1 and Model 2 can be gained with Fourier analysis (Figure 4). The top panel of Figure 4 shows overlaid plots of the raw data (black trace), the level component estimated by Model 1 (red trace) and the level component estimated by Model 2 (blue trace) for Region 2. The periodgrams for each of these traces are plotted in the second panel with corresponding colors. Examination of the traces in the top panel show that the level component approximated by Model 1 is similar to the raw data, with the respiration artifacts mostly intact but with the heartbeat artifacts greatly reduced. The periodogram for the raw data (lower panel, black trace) shows a spike localized around 1.47 Hz corresponding to the frequency of the heartbeat, marked with an asterisk. The periodogram for the Model 1 data is similar to that for the raw data at low frequencies, but also shows a small reduction in the energy across the higher frequencies and the elimination of the spike corresponding to heartbeat. Examination of the traces for the raw data and the level component from Model 1 show that the respiration cycle repeats itself approximately 8 times during the 60s trace (~0.13 Hz), however there is no concentrated spike at this frequency corresponding to respiration in their periodograms. Indeed, the periodogram for the Model 2 level shows a significant reduction in energy across the entire spectrum, suggesting that although each respiration cycle occurs periodically in time, its waveform is not localized in the frequency domain, and hence can not be well described as a linear combination of a small number of sine waves. Further, the spectral components of the respiration waveforms possibly overlaps with those of the stimulation-evoked response; removal of the respiration artifact significantly reduces energy at all lower frequencies, where the spectral components for the response are presumably located. These observations suggest a possible reason as to why Fourier filtering has not proven to be an adequate approach for filtering noise in these types of data: the complex shapes of the respiration cycles are not well localized in the frequency domain, where their Fourier components possibly overlap with those of the activity-evoked response.

Figure 4. Fourier Analysis of the Linear Trends Estimated by Models 1 and 2.

To further understand the differences in the results given by the two DLMs, periodograms of their estimated level plots and of the raw data were compared. Panel A shows superimposed plots of the raw data (black trace) and level components given by Model 1 (red trace) and Model 2 (blue trace) for Region 2 (see Figures 2 and 3, panel E). The level estimated by Model 1 appears to be an accurate representation of the raw data, but with a complete filtering of the heartbeat cycles, leaving the respiration cycles unaltered to visual inspection. The level estimated by Model 2 appears to be a complete filtering of both the heartbeat and respiration cycles, while maintaining the stimulation-evoked optical response. The periodograms for each of the traces in panel A are shown below in panel B using the same colors for the corresponding traces. The periodogram for the raw data shows a large peak at the heartbeat frequency, marked by an asterisk in the black trace, that is absent in the level curve estimated by Model 1.

To explore this issue further, we attempted to construct a Fourier-based notch-filter for several different time series using the MATLAB Filter Design & Analysis toolbox. This software provides an interactive interface for quickly viewing the results obtained by modifying the filter parameters. Since there are no obvious bands in the frequency domain corresponding to the respiration artifact and the optical response, a band for the filter was chosen by trial-and-error. In this way, it was possible to eventually construct a filter that worked reasonably well at removing most of the respiration artifact while maintaining much of the functional response. However, careful fine-tuning of the filter parameters were required to avoid elimination of the response along with the respiration artifact. The trial-and-error method for selecting the optimal bands for the notch-filter had to be reapplied for each different time series, since the shapes of the respiration artifacts varied between time series. Based on this experience, we conclude that a Fourier-based filtering approach is possible using a carefully designed notch-filter, but it is a time-consuming and ad hoc process to determine the filter parameters that work well for any given time series. In contrast, for the DLM, we were able to determine the heartbeat and respiration periods quickly, and the determination did not have to be repeated for each time series. Presumably, although both the functional response and the respiration artifact are not localized in the frequency domain, their overlap must be sufficiently small so that it is possible to separate them with a finely tuned notch-filter.

3.4. Residual Analysis of Model 2

The appropriateness of Model 2 was further investigated by examining its forecast residuals, ρ2,t = y2,t−𝔼[y2,t|y2,1, …, y2,t−1], for Region 2. If the DLM adequately models these data, its forecast residuals should be Gaussian and not show temporal correlation. The raw residuals plotted against time (Figure 5, panel A) do not reveal any obvious time varying structure. The few outliers do not correlate in time to any features of the slope or level (for reference, see Figure 3, panels E and F). The plot of the standardized residuals (Figure 5, panel B) provides evidence for their Normality, since most values fall within the interval [−2, +2]. Further evidence for their Normality is provided by the QQ-plot (Figure 5, panel C). The Q-Q plot is a standard diagnostic test for Normality where one checks to see if most of the data falls near the diagonal line, as they appear to do so for these data. Further quantitative testing for Normality was done by applying a Kolmogorov-Smirnov to these data, giving a p-value > 0.99. The autocorrelogram (Figure 5, panel D) was also plotted to check for serial correlation amongst the residuals. Falling outside of the horizontal lines (95% confidence intervals) is equivalent to failing a formal hypothesis test. The autocorrelogram shows no significant correlation except at lag 5.

Figure 5. Analysis of Residuals from Model 2.

The residuals given by the estimate of Model 2 for Region 2 are analyzed here. The raw residuals are shown in panel A with vertical dashed lines showing the interval over which the cortex was stimulated. The standardized residuals shown in panel B provides evidence that their distribution is Normal since approximately 95% lie between +/− 2. The Normal Q-Q plot in panel C provides further evidence that the residuals are normally distributed. The autocorrelation plot of the residuals shown in panel D (horizontal dashed lines show 95% confidence intervals) shows little significant autocorrelation. Normal Q-Q plots (not shown) for the residuals given by Model 2 were generated for 18 other regions selected from the 6 subjects studied here, all showing reasonable agreement with Normality.

3.5. Investigation of the Accuracy of Model 2

One way to test of the accuracy of our model would be to combine two types of time series acquired from human subjects: 1) time series that are contaminated with respiration and heartbeat artifact but are free of activity-evoked optical responses, and 2) time series that are free of respiration and heartbeat artifacts, and contain identifiable activity-evoked optical responses. These two types of time series could be combined, and then the changes in the model-estimated level components of these combined series could be compared to the true optical changes as a measure of the model’s accuracy. Time series from human subjects that are contaminated with noise and free of activity-evoked optical responses are readily available. However, time series that contain activity-evoked optical responses, but are entirely free of respiration and heartbeat artifact, are not available since all intraoperatively acquired data from our human subjects are noisy. Since noise-free human data is unavailable, we instead use relatively noise-free time series acquired from primates. Activity-evoked optical changes of the primate cortex were elicited through the identical stimulation protocol, and acquired using the same experimental equipment, as was used in all human experiments. These relatively noise-free primate data containing known optical responses can be combined with noise acquired from human subjects, and the combined time series can be used to test the accuracy of Model 2 in the way described above. Primate ImIOS data, as acquired in our laboratory, has the advantage of being nearly free from respiration artifact (Haglund and Hochman, 2007). Since the density and organization of the pial arteriole network and the thickness of the cortex are similar between primates and humans (Mchedlishvili and Kuridze, 1984; Striedter, 2005), it may be reasonable to assume that activity-evoked optical responses from the cortices of primates and humans have similar characteristics (to our knowledge, differences in the activity-evoked, cortical hemodynamic responses between humans and primates have never been reported).

Figure 6 shows the primate and human data that were used to construct test-signals. The top panel shows plots of five time series acquired from the primate, with the activity-evoked optical response in each time series being of a different shape and amplitude. These primate data represent times series with known optical responses. Primate ImIOS data typically is contaminated with a high frequency artifact from heartbeat that can be smoothed without altering the other features of the data. The heartbeat artifacts in these data were smoothed using a running-mean filter with a small window size (covering 7 data points); other changes and wiggles within the time series are of a larger scale and were found (by visual inspection) to be unaffected by this filtering. One example of unfiltered primate data is shown in Figure 6, where the raw signal (black trace) is superimposed over its corresponding smoothed signal (red trace) of the time series showing the largest optical response. The noise signal acquired from a human subject, to be added to each of the primate-derived true signals, is shown in the bottom panel of Figure 6. Five test-signals were generated by combining the human noise with each of the smoothed primate signals, and Model 2 was then used to estimate their level components, with the results of this analysis shown in Figure 7.

The first 5 panels of Figure 7 show the estimated level components and their 90% CIs (black traces), superimposed over their corresponding primate signals (red traces) that represent the known optical responses. One panel is dedicated to each of the 5 time series. Each of the plots of the known responses lies entirely within the 90% CIs of its level curve estimated from their corresponding test-series, with the exception of one small portion of the plot shown in panel 5. The true signal for that plot shows a wiggly portion near the point of the maximum response (minimum of the time series, near t = 35) that lies outside of the level CIs. Furthermore, the level component for this series smoothly interpolates the portion of the true response that has the wiggly feature. In order to better understand the reason for the decreased accuracy of Model 2 in this single instance, the set of plots from panel 5 are redrawn in panel 6, this time with its corresponding test series (black trace) superimposed over the true series (red trace) and estimated level (blue trace). It is apparent that the wiggly portion of the true data happens to coincide very closely with the shape and occurrence in time of a respiration artifact. To test whether the temporal coincidence of the respiration cycle with the small wiggle in the true signal could explain the loss of accuracy, the above analysis was again performed (not shown here) with the noise data phase-shifted so that the respiration cycle and the wiggle did not overlap. However, there was no improvement in accuracy, and so temporal coincidence appears to not play a role. It may be then that the loss of accuracy is due to the similarity between the shapes of the respiration cycle and the wiggle in in the true signal. Although this issue is not further explored here, it does identify a potential pitfall of our DLM model that may be important to bear in mind: true changes in the optical response that are of similar amplitude and shape to a modeled component representing an artifact may not be identifiable as responses in the DLM-estimated level curve.

3.6. Analysis of Data From Six Subjects with Model 2

As a final investigation into the applicability of Model 2 for the analysis of human ImIOS data, its results were examined for time series selected from six different subjects, at both 535 and 660 nm wavelengths. In four subjects, the cortex was activated with electrical stimulation (4 seconds; 60 Hz) (Figure 8, panels A, B, C, and D), while in two subjects (Figure 8, panels E and F) the cortex was activated with a tongue sensory-motor task (10 seconds of wiggling tongue against palate). The purpose of this analysis was to check whether the level curves estimated by Model 2 reduced the unwanted artifacts while preserving activity-evoked responses across a set of time series with different noise and response characteristics. In panels B through F, four time series were selected for analysis from each subject, with two of the time series being data acquired at 535 nm, and two at 660 nm. For each wavelength, one of the time series was chosen from a cortical region showing the largest optical response to the stimulus among all regions, and the other from a region showing the smallest response. The four time series for each of the six subjects were plotted in each panel of Figure 8 in the following order, from bottom to top: i) the region showing the largest optical change at 535 nm (first trace from bottom, purple), ii) the region showing smallest optical change at 535 nm (second trace from the bottom, purple), iii) the region showing the largest optical change at 660 nm (the third trace from the bottom, red), and iv) the region showing the smallest optical change at 660 nm (fourth trace from the bottom, red). The level curves estimated by Model 2 appear to greatly reduce or entirely eliminate the respiration and heartbeat artifacts while preserving the activity-evoked response in all time series. Dotted vertical lines indicate the time during which the cortex was stimulated or the patient engaged in the behavioral task. One apparent inadequacy of this model is in its inability to accurately capture the initial change in the response, where the estimated level component undergoes a change that is smoother than how it appears to actually occur in the raw data. This is most clearly apparent in the bottom purple time series in Figure 8; panel F, where the estimated level appears to start changing smoothly at a time slightly prior to the true response in the raw data. However, the magnitudes and shapes of the model-estimated level components appear to accurately match the optical responses in the raw data at all times following the onset of the response.

Figure 8. DLM Analysis of Optical Responses From Six Subjects at 535nm and 660nm.

To further examine the applicability of the DLM analysis, we examined the estimated level components of time series acquired from six different subjects, at both 535 and 660 nm light. The bottom trace in panel A shows the optical response acquired at 535nm (level component, purple trace; raw data, black trace), the middle trace shows the optical response at 660nm (level component, purple trace; raw data, black trace) and the top trace shows the ECoG activity (blue trace) recorded during the acquisition of the 535 nm data. Vertical dotted lines show the interval during which the stimulus was applied to the cortex. Panels B through F show two pairs of time series for the raw data (black traces) with the overlaid level components for 535 nm (purple traces) and 660 nm (red traces). In order from bottom to top, the traces in each panel are from: i) The region showing the largest optical response to a given stimulus at 535 nm, ii) the smallest responding region at 535 nm, iii) the largest responding region at 660 nm, and iv) the smallest responding region at 660 nm. The optical responses in panels A–D were each elicited by four seconds of electrical simulation applied to the cortex, and those in panels E and F are functionally-evoked responses from regions overlying tongue motor-sensory cortex elicited by sensory activation. The pair of vertical dotted lines in each panel indicate the time during which the cortex was activated either by electrical stimulation or a tongue motor-sensory task.

3.7. Inferential Analysis Using Model 2

Next, using ImIOS data acquired from a single subject, it will be demonstrated how Model 2 can be used for quantitative analysis (Figure 9). Practical neurosurgical applications of optical mapping will require the ability to quantitatively distinguish differences in the optical responses of various cortical sites, to stimulation with electrical currents of varying magnitudes, in the individual patient being mapped. As a demonstration of the use of Model 2 for this purpose, we analyzed 535 nm optical data acquired from a single subject whose cortex was stimulated four times at three different stimulation currents (4mA, 8mA, and 14mA). ImIOS data was acquired during each of the 24 stimulation trials. Two of the stimulation trials at each current occurred while the patient was awake, and two after the patient was anesthetized. Thus data was acquired at three different simulation currents, where each current was delivered under under two different conditions (awake vs. anesthetized). Simultaneously acquired ECoG data confirmed that afterdischarge activity was not elicited during any of the stimulation trials (data not shown).

Figure 9. Inferential Analysis of Optical Responses during Awake and Anesthetized States.

The optical responses shown here were acquired from the cortex of a single subject during four stimulation-trials at each current of 4mA, 8mA, and 14 mA (for a total of twelve stimulation-trials). Two stimulations at each current were administered while the patient was awake, and two at each current while the patient was anesthetized.

Top Left Panel: Optical imaging data has typically been represented qualitatively as pseudo-colored images, in which colors are assigned to pixels in some way so that different magnitudes of response can be visually distinguished. Shown in the upper left panel is a gray-scale image (left) and its pseudo-colored image (right) representing the largest optical response that was elicited by four seconds of 8 mA stimulation. The colors were assigned according to a ‘spectrum’ coloring scheme in which red is assigned to those pixels showing the largest magnitude changes (~−12% in this image) and dark blue to those pixels undergoing small changes close to 0%. Two regions were selected for further analysis; Region-1 near the stimulating electrode (labeled “Stim”) around which the largest optical response was elicited, and Region 2 at a position 2 cm away from the stimulating electrode and on a different gyrus than Region 1.

Right panels: The optical responses of the two regions to four seconds of stimulation current (blue traces) and during a control period when no stimulus was applied (black trace at the top near 0% in each plot) are plotted with their 90% CIs (red traces). Only one of the four level curves (estimated by Model 2) obtained at each of the stimulating currents is plotted for Region-1 (top) and Region-2 (bottom).

Bottom left panel: The peak optical responses were estimated by using Model 2 to generate the posterior distributions for the peak response in the level component, and at each region (Region 1, red; Region 2, blue), for each of the twenty-four stimulation time series. That is, twelve stimulation trials were carried out for each region, with two stimulations at each of the three currents for both awake and anesthetized conditions.

Two regions are chosen to be analyzed: Region 1, which was located on a gyrus immediately adjacent to the stimulating electrode in which the largest optical responses at 535 nm were elicited, and Region 2, which was located on the gyrus most distal to Region 1 (Figure 9, top left panel). A quantitative analysis was applied to study four issues: i) the similarity of activity-evoked optical responses from trial to trial when the identical stimulus is applied multiple times to the same cortex, ii) the ability to detect differences in the optical responses elicited by different stimulation currents, iii) differences in the optical responses between the two regions that varied in their distances from the stimulating electrode, and iv) the effects of anesthesia on the optical responses. The optical responses of the two regions to four seconds of stimulation current (Region 1, top right panel; Region 2, bottom right panel, blue traces) and during a control period when no stimulus was applied (black traces at the top near 0% in each plot) are plotted with their 90% CIs (red traces). For clarity, only one of the four level curves, estimated by Model 2, obtained at each of the stimulation currents is plotted for each of these regions.

The plots shown in the right panels quantify the relationship between the optical response and the magnitude of the stimulation current at two different positions relative to the stimulating electrode. Note that 4 mA stimulation current did not elicit any response that was distinguishable from baseline variation in Region 2. These plots illustrate how the optical responses vary according to the amplitude of the stimulation current and the distance to the stimulating electrode. The peak optical responses during each stimulation trial (i.e. the largest optical response that was observed for a region during a single stimulation trial, corresponding to the lowest points in the plots shown in the right hand panels) and their 95% CIs (not shown) were estimated from the MCMC simulations of Model 2 which were used to calculate the posterior distributions for the peak response in the level component at each region, for each of the twenty-four stimulation time series (i.e. twelve stimulation trials for each region, with two stimulations at each of the three currents for both awake and anesthetized conditions) (Figure 9, bottom left panel). All of the individual peak responses acquired when the patient was awake and anesthetized are plotted (Region 1 responses in red; Region 2 responses in blue; awake responses with X’s; anesthetized responses with dots). It is apparent that the peak responses for repeated stimulation trials at the same current fall within a narrow range of approximately +/− 1% from the mean. These results suggest that, in this subject, there were either small or no significant differences in the optical responses between awake and an anesthetized conditions. Furthermore, the four responses at each of the three stimulation currents show a relatively high degree of repeatability of the trial-to-trial responses to identical stimuli, at least as assessed by studying the peak responses in this one patient.

4. Discussion

4.1. Model Development

The purpose of this study was to construct a useful statistical model for removing noise and analyzing intraoperatively acquired optical imaging data from the exposed human cortex. Although many different approaches might work well, we chose dynamic linear modeling. It is apparent by inspection of our raw data that our time series appear to have two quasi-cyclic components corresponding to respiration and heartbeat, and a slowly varying functional response. The DLM provides a straightforward framework for representing each of these physiologically meaningful components. The model can then be easily modified to accommodate additional noise artifacts, for example, simply by adding additional components. We began by first constructing a DLM with single components for each of the local linear trend, heartbeat, and respiration cycles, and found that it was not adequate for modeling the complex varying shapes of the respiration cycles (Model 1). Adding a second harmonic to the respiration component yielded a DLM (Model 2) that seemed to address the inadequacies of the simpler Model 1. This final DLM seems to be broadly applicable in the sense that it was shown to be capable of greatly reducing the respiration and heartbeat artifacts while preserving the activity-evoked optical response in data that was acquired at both 535 nm and 660 nm from six human subjects, for cortical activity that was elicited by either electrical stimulation or functional (tongue motor-sensory) activation. When known optical responses from the primate cortex were combined with respiration and heartbeat artifacts acquired from the human cortex, the level component estimated by the DLM was found to accurately recover the original optical responses in most of the tested time series. It was found that there was a small loss in accuracy for separating the respiration artifacts from the local linear component in the case when the optical response had features that were of a similar shape as a respiration cycle (Figure 7, panels 5 and 6). The DLM was also found to be less accurate in modeling the initial onsets of some of the optical responses (Figure 8). In those cases, the level component tended to start changing prior to, and changed more smoothly than, the actual changes apparent in the raw data This suggests that the DLM developed here would be inadequate for accurately estimating onset-times of rapidly changing responses. Only a limited number of data sets were studied here, and a better understanding of the scope of applicability and further limitations of our modeling approach will be arrived at through further experience gained from analyzing larger numbers of optical imaging experiments. However, the results presented here are encouraging in that there was no special reason for choosing the data sets that were studied, and the time series from the six subjects analyzed presumably represent typical optical imaging data.

Several alternative modeling approaches or modifications to the one described here were pursued but found to be less adequate. One approach studied was a Fourier analysis followed by band-pass filtering to remove the cyclic components. Although the respiration cycles are periodic, they are not well localized in the frequency domain, and possibly share frequency components with the optical response (Figure 4). These features might explain why it seems difficult to find Fourier-based filtering techniques capable of greatly reducing the respiration artifact while preserving the features of the optical response. Here, with the exception of the periods of ht and rt that were estimated off-line, we chose a Bayesian, DLM approach to modeling. We had also attempted a DLM analysis that decomposed the signal into constituent parts without using a priori knowledge of the existence of heartbeat and respiration (see (Aguilar et al., 1999; West and Harrison, 1989)) but this did not work as well. We estimated the periods of ht and rt off-line because their mixing in MCMC chains tends to be poorer than for other parameters and incorporating uncertainty about them is not critical since DLM models for cyclic components can adjust for inexact specification of the period. We had also explored the use of maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) instead of MCMC for the estimation of the variances in Model 2. MLE has the advantage of requiring dramatically less computational time than MCMC approaches. However, we found that for some time series, the numerical algorithm for computing the MLE was sensitive to starting conditions and could not always be made to converge.

As described in the Introduction, we provided details describing how we improved upon the inadequacies of a first model (Model 1) as an illustration for how one might modify our final model (Model 2) in ways that might be more suitable for the analysis of other types of time series derived from optical data. Infrequently, optical data acquired from human subjects appear to have another quasi-cyclic component that is slower than the respiration component, and that may have similarities to the ’0.1 Hz oscillations’ found in some animal models (Mayhew et al., 1996). Although not presented here, we had studied several time series containing this additional type of artifact, and found that they could be adequately analyzed by adding an additional cyclic component with two harmonics to our Model 2 DLM (i.e. the ’other components’ in Eq 1). The procedure for modifying Model 2 to handle data with this additional artifact is similar to the procedure described here, by adding an additional cyclic component to Model 2 of the form given by Equation 6.

The work described here has similarities to another previously described modeling approach (Myers et al., 2007). That study developed a DLM for the analysis of optical imaging data acquired from the visual cortex of a cat. In contrast to our approach of estimating the respiration and heartbeat components from the data, that study directly incorporated auxiliary physiological information (recordings of systemic blood pressure acquired simultaneously with the optical images) and did not attempt to model respiration explicitly. Since such auxiliary data are available during intraoperative procedures, they could also be incorporated into modified versions of our model in a similar manner. However incorporating such auxiliary physiological data, other than for the purpose of providing frequency information about respiration and heart beat artifacts, may be less useful for modeling data acquired from larger animals such as monkeys and humans, than it is for data acquired from smaller animals such as cats. It has been our experience from primate studies that the shapes of the respiration cycles that are apparent in blood pressure recordings bear little resemblance to the artifacts in the optical signals recorded from cortex. Indeed, an important characteristic of our data recorded from human subjects is that the shapes of the respiration artifacts in the optical data can vary greatly between different cortical regions from the same subject (see Figure 8). Another important difference between our respective approaches, is that the model used in the Myers et al. study incorporated information about the times at which the cortex was stimulated directly into their model. Information about the timing of stimuli could also be incorporated into a modified version of our model for those situations where such information is available. However, one clinically important application motivating our development of a model that does not require this information is for the analysis of data containing optical responses to spontaneously occurring epileptic activity.

4.2. Applicability of the DLM approach to other functional brain imaging modalities

Details specific to the optical imaging technique itself played no direct role in the development of our statistical modeling. Our modeling choices were motivated by consideration of the features in raw optical imaging data. We began by identifying a set of characterizing features that were typical of time series derived from sequences of optical images (see Section 3.1), and constructed the simplest DLM (Model 1) that we thought might account for those features. We next identified the inadequacies of that model through empirical investigation using real data, and modified it accordingly to arrive at the final model (Model 2) that was found to work well for all of our optical imaging data sets. The key features of our data that were incorporated into our model were quasi-cyclic contributions for heartbeat and respiration, and a slowly varying linear component for the functional response. It might be expected then, that the methods developed here may also work well for data acquired by other neuroimaging modalities when those other data can also be accurately modeled by a small number of quasi-cyclic components combined with a time-varying functional response similar to the one observed in optical imaging data. In view of these considerations, the DLM developed here may not be useful for modeling functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) data, at least not without significant modification. This is because fMRI data has a more complex structure than the optical imaging data studied here (Birn et al., 2006; Oikonomou et al., 2010). The greater complexity of fMRI data is in part due to the slower sampling rates not being sufficient to accurately sample the heartbeat and respiration cycles, causing the contributions from those artifacts to be aliased across a range of lower frequencies. Thus the noise contributions from physiological sources are not represented in fMRI data as two individually identifiable quasi-cyclic components as they are in our optical imaging data(Triantafyllou et al., 2005). As well, the physiological noise and functional responses in fMRI data is thought to be best modeled as multiplicatively interacting components, rather than additively as required by our modeling approach. (Diedrichsen and Shadmehr, 2005).

4.3. Computational Issues and Feasibility for Intraoperative Mapping

The following quantities are unknown in our DLM models and have to be inferred from data: periods of the heartbeat and respiration components; variances V, Ws, Wh, and Wr; and (θ1, …, θt).

Estimation of periods

We find that estimating periods by counting the number of heart and respiration cycles in a fixed interval of time is easy and, because the allow the model to adjust for inaccuracies and dynamic changes, adequate for our purpose. In contrast, including periods among the parameters whose posterior distribution is explored by MCMC can cause convergence problems. Therefore, we adopt and recommend the easy approach for estimation of periods.

Estimation of variances

We have also explored different approaches for estimating the variances V, Ws, Wh, and Wr. Throughout this manuscript, we report analyses in which these variances are included among the parameters explored by MCMC. In our experience, the approach works well and our MCMC chains appear to converge easily. However, MCMC can be computationally time-consuming. The computations for this work were done by running R code on a Win7 64-bit PC with two Quad-Core Intel Xeon W5580 3.2 GHz processors. The average processor time required to run the MCMC for 9 randomly selected time series, each of length 300 time points, was 1043s +/− 18s, or about 18 minutes. When 8 separate instances of R were simultaneously running the MCMC for these same 9 time series (to test the advantage of utilizing the multiple processor cores available on this computer), the average processor time was 1152s +/− 84s, or about 19 minutes. We also tested the running time on 10 different time series varying in length from 300 to 1016 time points, and found the average processing time increased linearly, requiring on average 3.5s +/− 0.5s per time point regardless of the length of the time series. In view of these results, we consider the DLM method to be feasible for use in the operating room if the optical imaging technique proves to improve patient outcome or can eliminate aspects of the costly and time-consuming pre-surgical ECoG mapping procedure that is currently common practice.

An alternative algorithm is to estimate the variances by maximum likelihood, is to treat these variances as known, and calculate the posterior distribution of (θ1, …, θt) conditional on them. Since the conditional posterior distribution of (θ1, …, θt) can be calculated quickly by algorithms such as the Kalman filter, this approach is faster. One difficulty with this approach is that the maximum likelihood estimates of V, Ws, Wh, and Wr must be found numerically. It is well-known that numerical optimizers can fail by getting trapped in local maxima, saddle points, or flat spots. In our experience, the numerical optimizer we mostly used - the optim() function in R - works well for most data sets. And it can often be recognized when it fails because the plots of the smooth, heart, and respiration components do not look sensible. So for most regions, most of the time, this approach would work well. When the optimizer fails, possible remedies include running the optimizer from several different starting points, choosing clever starting points, and using stochastic algorithms such as simulated annealing. However, these approaches require more computational time.

Scalability

The computational cost of our approach is dominated by the MCMC algorithm, and is proportional to the number of regions being analyzed. However, we found only a small increase in processor time when running our model on 8 time series simultaneously on a computer with 2 quad-core processors. The computational cost is linear in the length of the time series (found to be about 3.5s per time point on our computer). The calculations for a DLM require inverting matrices whose size is the number of parameters inθ. Matrix inversion is known to have a complexity of approximately O(n3). Thus models that are made more complicated by the addition of more parameters in the state vector would require longer running times.

4.4. Inferential Analysis of the Optical Responses

As a demonstration of how the DLM can be used for the statistical analysis of optical data, the posterior distributions for the peak optical responses (acquired at 535 nm) to electrical stimulation were calculated for a set of time series from which the mean responses and their CIs were estimated. We studied data from a single subject whose cortex was stimulated multiple times at three different stimulation currents under both awake and anesthetized conditions (Figure 9). Our purpose for this example was to demonstrate how the model can be used to quantify the responses at different cortical regions to different types of stimuli in an individual cortex, which is how this model might by used in practical neurosurgical applications. In this subject, it was found that anesthetic (propofol) did not significantly effect the peak optical responses in either the areas immediately adjacent to the stimulating electrode or its spread to areas several centimeters away from the stimulating electrode. It was also found that there was relatively little trial-to-trial variation in the peak optical responses to identical stimuli. Future work will involve testing whether quantification of the optical responses of cortical tissue using the techniques described here can be used for the intraoperative localization of epileptogenic regions.

Research Highlights.

-

-

A Bayesian dynamic linear model was found useful for analyzing human optical imaging data;

-

-

The model removed heartbeat and respiration artifact while preserving activity-evoked responses.

-

-

Robustness of the model was verified on data acquired from six subjects, acquired at two wavelengths (535 nm; 660 nm).

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source

This work was funded by an NIH grant NS065181 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders (NINDS). NINDS had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aguilar O, Huerta G, Prado R, West M. Bayesian inference on latent structure in time series. In: Bernardo JM, Berger JO, Dawid AP, Smith AFM, editors. Bayesian Statistics 6: Proceedings of the Sixth Valencia International Meeting; Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1999. pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Bathellier B, Van De Ville D, Blu T, Unser M, Carleton A. Wavelet-based multi-resolution statistics for optical imaging signals: application to automated detection of odour activated glomeruli in the mouse olfactory bulb. NeuroImage. 2007;34:1020–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besag J, Green P, Higdon D, Mengersen K. Bayesian computation and stochastic systems. Statist Sci. 1995;10:3–36. [Google Scholar]

- Birn RM, Diamond JB, Smith MA, Bandettini PA. Separating respiratory-variation-related fluctuations from neuronal-activity-related fluctuations in fmri. Neuroimage. 2006;31:1536–1548. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannestra AF, Pouratian N, Bookheimer SY, Martin NA, Beckerand DP, Toga AW. Temporal spatial differences observed by functional mri and human intraoperative optical imaging. Cereb Cortex. 2001;11:773–782. doi: 10.1093/cercor/11.8.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SC, Wong YT, Hallum LE, Dommel NB, Cloherty SL, Morley JW, Suaning GJ, Lovell NH. Optical imaging of electrically evoked visual signals in cats: Ii. ica ”harmonic filtering” noise reduction; Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society: 29th Annual International Conference of the IEEE; 2007. pp. 3380–3383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen LB. Changes in neuron structure during action potential propagation and synaptic transmission. Physiol Rev. 1973;53:373–418. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1973.53.2.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diedrichsen J, Shadmehr R. Detecting and adjusting for artifacts in fmri time series data. Neuroimage. 2005;27:624–634. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.04.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbay M, Brennan C, Kaplan E, Sirovich L. A principal components-based method for the detection of neuronal activity maps: application to optical imaging. NeuroImage. 2000;11:313–325. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinvald A, Frostig RD, Lieke E, Hildesheim R. Optical imaging of neuronal activity. Physiol Rev. 1988;68:1285–1366. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1988.68.4.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]