Abstract

Rhinosporidiosis is a chronic inflammatory disease common in India and Sri Lanka. Its manifestations are mostly nasal, though extranasal ones in head and neck region are not rare. Occasionally these presentations lead to diagnostic dilemma. Here we present some cases with its associated confusions if any. In this study thirty five patients were included. Extranasal manifestations were noted in nine cases. Two patients attended with laryngopharyngeal and one with lacrimal sac presentation–subsequent nasal endoscopic examination revealed presence of nasal masses, too. Other six cases presented with polypoidal mass hanging from nasopharynx into oropharynx. One of them was confused with nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Two laryngopharyngeal masses were removed successfully with rigid laryngoscope followed by cauterisation of the base. The solitary lacrimal sac mass was excised by external approach combined with nasal endoscope guided excision of nasal mass. The other six cases with nasopharyngeal attachment were subjected to nasal endoscope guided removal. In all these cases, the base of the lesions was cauterised. The experience about the various manifestations and diagnostic problems is discussed here.

Keywords: Rhinosporidiosis, Extranasal manifestations, Laryangopharyngeal, Lacrimal sac

Introduction

Rhinosporidiosis is a chronic, granulomatous disease process caused by fungus-like organism known as Rhinosporidium seeberi. It is yet an unclassified fungus [1]. Rhinosporidiosis is characterised by reddish polypoidal mass which are hyperplastic and friable and sometimes it may be sessile. The disease mostly affects nasal cavity mainly involving anterior part of nasal septum, vestibule and also nasopharynx, but extranasal involvement, particularly in the lower aerodigestive tract including the tracheobronchial tree is rare.

The organism has an affinity for the mucous membrane of the nose and nasopharynx. It thrives in hot tropical climates of the endemic zones i.e. South India and Sri Lanka [2]. Apart from nasal cavity the other sites of involvement are lips, palate, uvula, conjunctiva, larynx, trachea, penis, vagina and even the bone [3, 4]. The diagnosis is usually delayed and difficult when extranasal sites are involved. Occupational and personal history are helpful in achieving diagnosis and histopathological examination is also necessary.

Materials and Methods

Patients were selected from the Otolaryngology clinic of our institution for the period of 2 years (Sept 2005–Aug 2007). During this period thirty five patients were diagnosed having Rhinosporidiosis involving different sites of head and neck region. After initial clinical examination, the patients were subjected to routine laboratory investigations for operative fitness and CT Scan of the relevant area of involvement in cases of atypical extranasal presentation Table 1.

Table 1.

Showing distribution of clinical presentations

| Type of presentation | Number |

|---|---|

| 1. Only nasal presentation | 26 |

| 2. Laryngopharyngeal presentation | 2 |

| 3. Lacrimal sac presentation | 1 |

| 4. Oropharyngeal presentation | 6 |

In the two cases having laryngopharyngeal presentation, the nose and nasopharynx were found to be free. There were multiple small lesions involving posterior pharyngeal wall. The masses were removed meticulously and their stalks were electrocauterised with bipolar system. Tracheostomies with cuffed tubes were done in both the cases to prevent dissemination in lower respiratory tract.

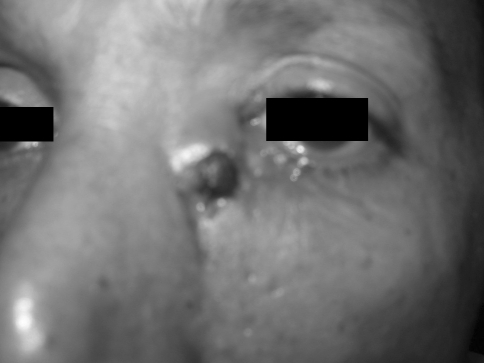

The patient presenting Rhinosporidiosis of the lacrimal sac was found to have typical lesion just below the inner canthus of left eye (Fig. 1). On anterior rhinoscopy, the vestibule was clear but subsequent nasal endoscopy revealed a small lesion in the posterior part of left inferior meatus. The patient had a previous history of excision of similar mass from same side of nose about 3 years ago but no documents were available. The patient was operated by a combined approach-external for the lacrimal sac and internal for the nasal mass by nasal endoscopy.

Fig. 1.

Rhinosporidiosis of lacrimal sac

In the present study maximum number of atypical oropharyngeal presentation i.e. 6 (six) were polypoidal lesions also involving the nasopharynx, which were, at times difficult to differentiate clinically from antrochanal polyp (Fig. 2). One of the cases posed a greater diagnostic dilemma due to his age i.e. 20 years; it had to be differentiated from juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma.

Fig. 2.

Huge polypoidal Rhinosporidiosis seen through the oropharynx

The cases were operated with wide resection (if necessary under endoscopic guidance), with compulsory cauterisation of base.

Results

One of the two- laryngopharyngeal presentations had a recurrence, 8 months after removal and it was operated again. There was no recurrence up to 6 months of follow-up period. The other patient did not have recurrence during follow up period of 1 year. The case of lacrimal sac involvement was followed up for last 1 year no recurrence has been noted. The rest six cases having polypoidal presentation did not show recurrence, except one showed recurrence in much anterior site compared to previous one. Nasopharynx was not involved in that case. This was operated subsequently.

Discussion

The first case of Rhinosporidiosis was reported by Malbran in 1892 and was published by Seeber in 1900, who thought that they are protozoan spores [5], that’s why it was named as Rhinosporidium seeberi. But in 1923, Ashworth [6] described the fungus life cycle. In 1992, Ahluwalia discarded of its fungal etiology [7] and renamed the structures as nodular bodies.

Rhinosporidiosis is four times more common in males with usual age of presentation between 10 and 40 years [3]. Infection of nose and nasopharynx is observed in 85% of persons with rhinosporidiosis. Other sites involved are eye (9%), penile urethra, external ear and bones [3].

Macroscopically, the typical lesion of Rhinosporidiosis is fleshy, vascular, polypoidal and granulomatous, studded with grayish white dots, present on surface of lesion [8]. On histopathology, large round chitinous structure filled with endospores are seen [9]. Within 10 days, a sporangium is formed from this endospore through an intermediate trophozoite stage. The organism can be observed by staining the smears with routine hematoxylin and eosin stain.

The most effective treatment is wide excision with a cutting diathermy and cauterization of the base of lesion. Previously antifungal agents were also used but were ineffective [10].

The principal site of infection is usually the nasal cavity; where it manifests by a bleeding polyp, while six cases presented to us with a mass in oropharynx with little difficulty in swallowing. Endoscopic visualization revealed the attachment of mass at posterior end of the septum and nasopharynx.

In four cases the visible mass of oropharyngeal presentations did not present the typical appearance of Rhinosporidiosis. These cases created confusion in our observation. In one of these cases, the male patient was 20 years old and the appearance of the mass was fleshy, polypoidal and the surface was not granular like Rhinosporidiosis (Fig. 3). Considering all these factors, our clinical diagnosis was nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. But the possibility of Rhinosporidiosis was in our mind. Even after the CT Scan we were not sure about the diagnosis. So after the endoscopic removal of mass the base was cauterised. The histopathology report came in favour of Rhinosporidiosis.

Fig. 3.

Oropharyngeal mass causes clinical dilemma with nasopharyngeal angiofibroma

The patient who came with lacrimal sac presentation had previous history of removal of same type of mass from same side of nose. But no document was available. Subsequent endoscopic examination of nose revealed a small granulomatous mass in left inferior meatus. Probably he was previously operated for Rhinosporidiosis and some spores were disseminated in lacrimal sac through nasolacrimal duct during handling, and most likely it was the cause of secondary presentation.

Treatment of rhinosporidiosis is a problem. Diathermy excision is considered to be the treatment of choice [11]. As the lesion is very vascular, we considered a biopsy or excision rather dangerous. The clinical presence of single lesion in nasal cavity and multiple lesions in the other parts of respiratory tract were proof enough of the diagnosis. In our two-laryngopharyngeal cases we were able to remove the masses entirely with cauterisation of the base.

Diathermy excision is an acceptable treatment modality in cases of nose and nasopharyngeal presentations. But when there is involvement of the tracheobronchial tree a more radical approach may be considered. Now as LASER is available at some centres, the choice of treatment may be cauterisation with LASER through a bronchoscope. However, LASER is still not freely available in India and Sri Lanka where Rhinosporidiosis is endemic [12].

In one case of the present series, where there was laryngeal involvement, recurrence was noted. The available literature suggests that in that case, it would have been appropriate to go for LASER surgery but the Institute did not have such a facility unfortunately.

Conclusion

Atypical presentation of rhinosporidiosis in head and neck region is rare. Very often, this atypical presentation causes dilemma in diagnosis and creates confusion. Till now surgical excision and cauterisation of the base remains the mainstay of treatment.

References

- 1.Emmons CD, Binford CH, Utz JP, Kwon-Chung KJ. Medical mycology. 3. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger; 1977. pp. 464–470. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khoo JJ, Kumar KS. Rhinosporidiosis presenting as recurrent nasal polyps. Med J Malays. 2003;58:282–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Franca GV, Jr, Gomes CC, Sakano E, Altermani Am, Shimizu Lt. Nasal rhinosporidiosis in children. J Pedatr (Rio J) 1994;70:299–301. doi: 10.2223/jped.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Makannavar JH, Chavan SS. Rhinosporidiosis: a clinicopthological study of 34 cases. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2001;44:17–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seeber GR (1900) Un nuevo esporozoaris parasito del hombre dos casos encontrados en polipos nasales. Thesis University Nac, de Buenos Aires, p 620

- 6.Ashworth JH. On Rhinosporidium seeberi with special reference to its sporulation and affinities. Trans Roy Soc Edinburgh. 1923;53:301–342. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahluwalia KB. New interpretations in rhinosporidiosis: enigmatic disease of last nine decades. J Submicroscop Cytol Pathol. 1992;24:109–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sood N, Rao SN. Rhinosporidium granuloma of the conjuctiva. J Pediatr Ophthalmol. 1969;6:142–144. doi: 10.1136/bjo.51.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuriakose ET. Oculosporidiosis, rhinosporidiosis of the eye. Brit J Ophthalmol. 1963;47:346–350. doi: 10.1136/bjo.47.6.346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Job A, Venkateswaran S, Mathan M. Medical therapy of rhinosporidiosis with dapsone. J Laryngol Otol. 1999;107:809–812. doi: 10.1017/s002221510012448x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khan AA, Khaleque KA, Huda MN. Rhinosporidiosis of the nose. J Laryngol Otol. 1969;83:461–473. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100070560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haacke NP, Mugliston TAH. Rhinosporidiosis. J Laryngol Otol. 1982;96:743–750. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100093075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]