Abstract

The aim of this work is to study the management and success rate of traumatic dacryocystitis and failed dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR) using Silicone lacrimal intubation set. A prospective study was conducted at a tertiary eye care hospital, India from February 2006 to January 2008. This study material comprised 50 patients of traumatic dacryocystitis and failed dacryocystorhinostomy. Anterior single flap external dacryocystorhinostomy with Silicon intubation was performed in all the patients. The patients were followed up at weekly intervals for 1 month and thereafter every 2 months for 1 year post operatively. Criteria determining success were based on resolution of epiphora and patency on syringing. In traumatic dacryocystitis, 21(91.3%) cases fulfilled these criteria while 23(85.2%) cases of failed DCR were successful. The overall success rate (88%) was determined with an average follow-up of 1 year. Globally, the technique was effective in 85% of cases. The results were comparable with other similar studies. This study concludes that performing a DCR in traumatic dacryocystitis and failed DCR taking into consideration the complications and chances of failure is a challenge for the surgeon. We opine that External dacryocystorhinostomy with Silicon Intubation is one of the most effective modality in dealing with such cases.

Keywords: Traumatic dacryocystitis, Failed dacryocystorhinostomy, Silicon lacrimal intubation

Introduction

In principle, dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR) is the removal of bone lying between the lacrimal sac and the nose and making an anastomosis between medial wall of the sac and nasal mucosa. Time has witnessed many modifications in the procedure as described by Adeo Toti, an ophthalmologist in 1904 almost a century ago, but the basics remain the same [1]. The success rate of external DCR has been reported up to 90% depending upon the surgeon’s experience [2]. Various other methods have also been adopted successfully such as endoscopic DCR, endonasal laser DCR, dacryocystoplasty and Radio Frequency assisted DCR [3–6]. However, the procedure of external DCR rules the roost in the management of epiphora in both the sexes of all age groups. According to Keerl et al. external DCR is better than endoscopic and endonasal laser assisted DCR [7]. Though a highly successful surgery, sometimes DCR can be a failure due to fibrous tissue growth, inappropriate size\location of bony ostium, common canalicular obstruction, sump syndrome, polyposis or an active systemic disease [8]. Injuries to head and neck region involving fracture of maxillo-facial and orbital region are very common nowadays. A large majority of these patients are left with complaints of epiphora, recurrent attacks of conjunctivitis and mucocoele after these injuries due to involvement of the lacrimal sac and/or nasolacrimal duct. External Dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR) with Silicon intubation is one of the most effective surgical procedures for such patients [9]. Iliff suggested suturing a rubber catheter into the lacrimal sac [10]. Routine use of silicon intubation as a useful adjunct to external DCR procedure was advocated by Older [11]. Till now very few studies have been carried out for the management of failed Dacryocystorhinostomies (DCRs) and traumatic dacryocystitis. So, we have taken the opportunity to do such a study and calculate the success rate. The purpose of this study is to determine the most direct approach in the management of such cases. It analyses the causes of failure of DCR and their proper surgical management. We have also tried to explain the importance of Silicon tube in failed external DCR and traumatic dacryocystititis.

Materials and Methods

This prospective study was conducted at a tertiary eye care hospital, India from February 2006 to January 2008 to study the success rate of bicanalicular Silicon intubation (23 G Lacrimal Intubation Set, J043, Pricon, India) in patients of traumatic dacryocystitis and failed DCR. We have defined failed DCRs as those cases, operated externally or endoscopically and still have been associated with complaints of epiphora, discharge, recurrent attack of conjunctivitis and traumatic dacryocystitis as disease entity in which anatomy of orbital and nasolacrimal region including canalicular trauma has been distorted due to ocular trauma which causes epiphora and discharge due to recurrent episodes of infection. Fifty patients were included in the study that underwent DCR with bicanalicular silicone intubation. All the cases were operated by a single surgeon in 24 months. This study was conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki. All patients with acute dacryocystitis, gross hypertrophy of middle turbinate, suspicion of malignancy of nose or lacrimal sac and radiation therapy for malignancy were excluded from the study.

All the patients underwent complete ophthalmic examination. Naso lacrimal system of patients was assessed by performing syringing, probing, nasal evaluation and dacryocystography. Patients were examined for canalicular, common canalicular or naso lacrimal duct (NLD) blockade. CT-scan was done in selected cases (Fig. 1). All patients were systemically evaluated and investigated to rule out any contra indication for surgery under local or general anaesthesia. A written and informed consent was taken from all the patients.

Fig. 1.

CT scan of a case of complicated dacryocystitis showing fracture of the medial wall and the floor of orbit

In case of traumatic dacryocystitis, a vertical 10 mm incision, 3 mm nasal to and centered by medial canthus was made. Fibres of orbicularis were separated bluntly to expose Medial Palpebral Ligament if present. The ligament was followed nasally to its attachment to the anterior lacrimal crest. The periostium was horizontally incised, just anterior to the anterior lacrimal crest, and then elevated using periosteal elevator from the whole lacrimal fossa reaching the posterior lacrimal crest and including the sac within it. Any bony deformity or growth if present was removed. A bony osteotomy about 15 mm in diameter was created including whole floor of lacrimal fossa. Anterior and posterior flaps were created in nasal mucosa and the lacrimal sac. After excision of posterior flaps, silicone tube was passed through both upper and lower canaliculi to reach the nasal cavity, where both its end was tied together. The anterior flap of lacrimal sac was then sutured with anterior flap of nasal mucosa with 6–0 vicryl to create a bridge and this in turn was stitched to periosteal margin over the anterior lacrimal crest.

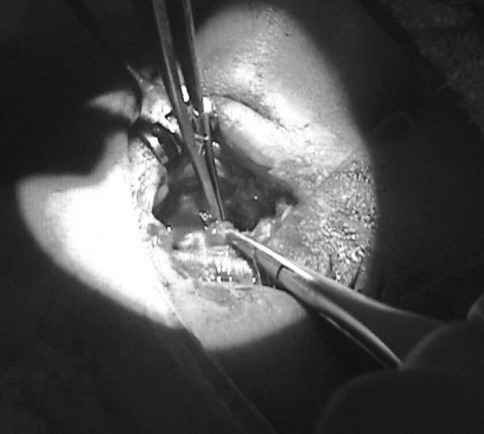

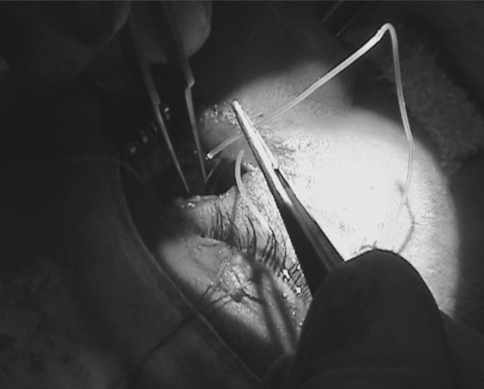

In case of failed DCR, an incision was made through the original scar. A combination of sharp and blunt dissection was used to separate the scar tissue. Probes were passed through the existing canaliculi to rule out any common canalicular obstruction. Any membranous obstruction of the common canaliculus was excised. When the probes were seen and easily felt within the canaliculi, attention was directed to defining the anterior edge of the original osteotomy. The periostium was horizontally incised and elevated from the anterior edge of the bony osteotomy reaching up to its posterior edge to expose the full bony ostium. The size and site of bony ostium was noted. Haemostasis was achieved as and when needed. The bone was removed anteriorly, and may be enlarged inferiorly and superiorly, to expose nasal mucosa. A incision was made in the newly exposed nasal mucosa to create a large flap. The interior of the osteotomy was then inspected. All intervening scar tissue was excised and healthy nasal mucosa was then anastomosed to the remaining sac (single anterior flap) (Fig. 2) after intubating the canaliculi with silicon tubes (Fig. 3). Orbicularis was repositioned with an absorbable suture, and the skin was closed with an interrupted nylon suture. Patients were given systemic Amoxicillin (250 mg), Cloxacillin (250 mg) with Lactic Acid Spores (80 × 106 cells) along with systemic anti inflammatory drugs for 5–7 days. Nasal decongestant drops of Xylometazoline 1 in 1000 and Hydrocortisone nasal drops were prescribed in the particular nostril. Antibiotic eye drops were given in the particular eye.

Fig. 2.

Showing anterior single flap being made with healthy nasal mucosa

Fig. 3.

Shows Silicon tube after being inserted into the canaliculi, is passed through the nasal mucosa

The patients were followed up at weekly intervals for 1 month and thereafter every 2 months for 1 year post operatively. Absence of epiphora and patency on syringing at the end of 1 year follow-up without the need for further surgical intervention was considered a success. Silicon tube was removed after 6 months post operatively.

Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS statistical software package (Version 11.5; SPSS, Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA). We utilized the Z test for proportions for comparing our result with the global values for the post operative success rate for traumatic dacryocystitis and failed DCR, respectively [12].

Results

Out of 50 cases selected for our study, 23 (46%) cases were of traumatic dacryocystitis and 27 (54%) cases were of failed DCR. Failed DCR were further sub-categorized into failed external DCR and failed endoscopic DCR which were 20 cases and 7 cases, respectively.

Females 35 (70%) outnumbered males [15] (30%). The male–female ratio was 3:7. Mean age of females was 39.6 years (Range 12–70 years) and mean age of males was 29 years (Range 8–55 years). Mean age of study sample was 36.4 (Range 8–70 years). Maximum number [22 (44%)] of patients were seen in the age group of 21–40 years (Table 1).

Table 1.

Age distribution of patients

| Age (years) | Male patients | Female patients | Total patients |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0–20 | 4 | 4 | 8 (16) |

| 21–40 | 8 | 14 | 22 (44) |

| 41–60 | 3 | 14 | 17 (34) |

| 61–80 | 0 | 3 | 3 (6) |

| Total patients | 15 (30) | 35 (70) | 50 |

| Mean age (years) | 29.0 ± 13.8 | 39.6 ± 16.2 | 36.4 ± 16.3 |

Value in parenthesis depicts percentage

Causes of failure in primary DCR were found during the surgery, the most common being fibrous tissue growth at bony ostium seen in 11 (40.7%) cases and least common being presence of intact lacrimal sac seen in 1 (3.7%) case of failed endoscopic DCR (Table 2).

Table 2.

Causes of failure in primary DCR

| Causes of failure | Number of cases |

|---|---|

| Fibrous tissue growth at bony ostium | 11 (40.7) |

| Collapse of the bridge between anterior flaps | 3 (11.1) |

| Sump syndrome | 4 (14.8) |

| Inappropriate size or location of bony ostium | 5 (18.5) |

| Common canaliculi obstruction | 3 (11.1) |

| Intact lacrimal sac | 1 (3.7) |

Value in parenthesis depicts percentage

The success rate was assessed on the resolution of epiphora and patency on syringing. In complicated dacryocystitis, 21 (91.3%) cases fulfilled these criteria while 23 (85.2%) cases of failed DCR were successful after silicone intubation.

The overall success rate was 88% with an average follow up of 1 year. The global results indicate an efficiency rate of 85% for the technique. For traumatic dacryocystitis and failed DCR, the global values for post-operative success rate were 90 and 83%, respectively. No statistically significant difference was found in the effectiveness of the technique when compared with its global values.

Discussion

DCR with silicone tube intubation has been accepted as a highly successful procedure in patients with history of epiphora and discharge following failed DCR. In revision cases especially when the bony ostium is of adequate size or failure is due to fibrosis at the osteotomy site can be also be managed with endoscopic DCR as an alternative to external DCR and are equally successful [13]. However, the disadvantages of endonasal DCR include the high cost of equipment and maintenance, the necessity to use general anesthesia that is preferred by most surgeons, a marked learning curve, difficulties in the treatment of other important causes of DCR failure like canalicular or common canalicular obstruction or sump syndrome [14].

Causes of failed DCR include fibrous tissue growth, inappropriate size or location of bony ostium, scarring within the osteotomy, common canalicular obstruction, sump syndrome, intervening ethmoid sinus air cells, interference of the middle turbinate, collapse of the bridge between anterior flaps and previously identified canalicular stenosis, active systemic disease, nasal polyposis and concha bullosa [15–20].

In our study, the most common cause of failed DCR was fibrous tissue growth at bony ostium (11 cases, 40.74%) and the least common cause was presence of intact lacrimal sac seen in a case of failed endoscopic DCR (1 case, 3.7%). Sump syndrome, common canalicular obstruction and collapse of bridge between anterior flaps is also an important cause of DCR failure which also needs external widening of the sac. In our study 10 (37%) cases belong to such category (Table 2). Thus the presence of a cosmetic scar should not be the only guiding principle when deciding on the most appropriate route for operation for a particular patient [14]. The main aim of the surgeon while performing external DCR in traumatic dacryocystitis and failed DCR is to bypass the lower lacrimal system and to create a large ostium utilizing the medial wall of the sac and nasal mucosa. Performing a second DCR taking into consideration the complications and chances of failure is a challenge for the surgeon because of distorted anatomy of the previously operated area, fibrosis and granulation tissue around the operated site and regenerated lacrimal sac as occurs in sump syndrome [21]. The distorted anatomy in traumatic dacryocystitis like over-riding of fronto-lacrimal suture, fibrosis, fractures of nasal bones and inflammatory reaction create difficulty in making the flaps of lacrimal sac remnant. If the bony ostium is small in a failed DCR, we have increased the size of the same ostium instead of making a new one keeping in mind that the ostium contracts after the operation [21]. The classical teaching on external DCR advises that the bony opening created at surgery be at least 15 mm in A-P diameter [22]. This teaching suggests that all bone between the medial wall of the sac and the nose should be removed leaving approximately an area of 5 mm around the internal punctum free of bone. Large osteotomy is needed to suture the full length of the sac wall to the nasal cavity and prevent canalicular obstruction due to scar formation around the internal punctum. This increases the chances of maintaining the patency of the opening [21].

Advantages of anterior flap DCR without posterior flaps include obstructing the secretions by posterior flaps [23]. Also, there are lesser number of internal openings in the drainage cavity, hence lesser chances of obstruction due to scar formation around the punctum. There are increased chances of sump syndrome with posterior flaps. Additionally, there are lesser chances of infection with only anterior flaps. Lastly, with a single anterior flap the lacrimal sac remnant integrates into the nasal wall and tears drain directly from the canaliculi into the nasal cavity.

Also, in our study, we have passed a silicone tube from the upper and lower canaliculi, ultimately going through the bony osteotomy and finally tied it in the nasal cavity. Silicone intubation is utilized in all cases of trauma because of the presumed predisposition to inflammation after trauma [24]. The tube is removed after 6 months which is sufficient for fibrosis of the tract to occur. Silicone tube in high risk cases like failed DCR or traumatic dacryocystitis is usually kept for 6 months due to severe post operative inflammation. Fibrosis may develop around the silicone tube, leading to double canal formation thus maintaining the patency of the tract.[9]. The relationship of success rate of DCR was related to silicon intubation. Advantages of silicon intubation are maintenance of patency of the tract. Fibrosis and inflammation could not obstruct the tract thus allowing adequate drainage of the secretions [25].

The success rate of our study was 88% which was in accordance with other study groups. [2, 12, 23] The global value for success rate of DCR with Silicone intubation in DCR cases with high failure rate is 85% out of which it is 90% post traumatic cases and 83% in failed DCR cases [12]. On comparing these global values with results of our study, utilizing the Z test for proportions again confirms the significance of this procedure.

Out of the 6 cases that failed in our study, 2 cases had spontaneous extrusion of silicon tube, 3 cases could not tolerate the silicone tube and it has to be removed and in 1 case there was profuse per operative bleeding. Cases where stents were not retained usually fails due to severe inflammation and refibrosis of these high risk cases. However, resurgery can prevent the failure of these cases [26]. Every surgical procedure has its advantages and disadvantages, no surgery is flawless. Complications of a particular surgery should not shy away a surgeon from doing a surgical procedure if its advantages outweigh its disadvantages.

Other procedures used in place of external DCR with silicone intubation are Endoscopic DCR, Endonasal laser assisted DCR, Endoscopic Dacryoplasty with or without Mitomycin-C. None of these methods except Endoscopic DCR seem to challenge the success rate of external DCR [16].

The technique of DCR with silicone intubation is a good option in nasolacrimal system obstructions following trauma or reobstruction when conventional techniques have a high index of failure. Bicanalicular intubation for lacrimal drainage system is a simple, inexpensive and straight forward adjunct to conventional external dacryocystorhinostomy. The procedure is strongly indicated for patients with chronic dacryocystitis who are at high risk of surgical failure [9].

References

- 1.Nofal MA. Dacryocystorhinostomy: to intubate or not to intubate? CME J Ophthalmol. 2002;6(1):3–5. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delaney YM, Khooshabeh R. External dacryocystorhinostomy for the treatment of acquired partial nasolacrimal obstruction in adults. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86(5):533–535. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.5.533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jin H-R, Yeon J-Y, Choi M-Y. Endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy: creation of a large marsupialized lacrimal sac. J Korean Med Sci. 2006;21(4):719–723. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2006.21.4.719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moore WM, Bentley CR, Olver JM. Functional and anatomic results after two types of endoscopic endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy; surgical and holmium laser. Ophthalmology. 2002;109(8):1575–1582. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(02)01114-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pak J, Mark TD (2006) Balloon-assisted dacryoplasty in adults. In: The lacrimal system: diagnosis, management, and surgery, section 3, chapter 17. Springer, Berlin, pp 189–196

- 6.Javate R, Pamintuan F. Endoscopic radiofrequency-assisted dacryocystorhinostomy with double stent: a personal. Exp Orbit. 2005;24(1):15–22. doi: 10.1080/01676830590890864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keerl R, Weber R (2004) Dacryocystorhinostomy-state of the art, indications, results. Laryngo-rhino-otologie (Laryngorhinootologie) 83(1): 40–50 (Germany) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Cohen AJ, Waldrop FC, Weinberg DA (2006) Revision dacryocystorhinostomy, chapter 25, section 3. In: The lacrimal system: diagnosis, management, and surgery. Springer, Berlin, pp 244–254

- 9.Sodhi PK, Pandey RM, Malik KP. Experience with bicanalicular intubation of the lacrimal drainage apparatus combined with conventional external dacryocystorhinostomy. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2003;31(3):187–190. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(03)00020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ilifff CE. A simplified dacryocystorhinostomy. 1954–1970. Arch Ophthalmol. 1971;85(5):586–591. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1971.00990050588011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Older J. Routine use of silicon stent in a dacryocystorhinostomy. Ophthalmic Surg. 1982;13:911–915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Junceda-Moreno J, Dos-Santos-Bernardo V, Suarez-Suarez E. Double intubation technique for the treatment of epiphora in complicated cases. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2006;81:101–106. doi: 10.4321/S0365-66912006000200010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El-Guindy A, Dorgham A, Ghoraba M. Endoscopic revision surgery for recurrent epiphora occurring after external dacryocystorhinostomy. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2000;109:425–430. doi: 10.1177/000348940010900414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharma V, Martin PA, Benger R, Kourt G, Danks JJ, Deckel Y, Hall G. Evaluation of the cosmetic significance of external dacryocystorhinostomy scars. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:359–362. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Costa MN, Marcondes AM, Sakano E, Kara-José N. Endoscopic study of the intranasal ostium in external dacryocystorhinostomy postoperative. Influence of saline solution and 5-fluorouracil. Clinics. 2007;62(1):41–46. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322007000100007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vergez A, Herbert F (1978) A propos de la dacryocystorhinostomie. Bull Soc Ophtalmol 273–276 [PubMed]

- 17.Hurwitz J. Failed dacryocystorhinostomy in Paget’s disease. Can J Ophthalmol. 1979;14:291–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weingarten R, Goodman E. Late failure of a dacryocystorhinostomy from sarcoidosis. Ophthalmic Surg. 1981;12:343–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Costa M, Sakano EO. valor da endoscopia nasal na semiologia lacrimal. Arq Brás Oftalmol. 1989;52:140. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Picó G. A modified technique of external dacryocystorhinostomy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1971;72:679–690. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(71)90001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yazici B, Yazici Z. Final nasolacrimal ostium after external dacryocystorhinostomy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121:76–80. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Welham RAN, Wulc AE. Management of unsuccessful lacrimal surgery. Br J Ophthalmol. 1987;71:152–157. doi: 10.1136/bjo.71.2.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baldeschi L, Nardi M, Hintschich CR, Koornneef L. Anterior suspended flaps; a modified approach for external dacryocystorhinostomy. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998;82:790–792. doi: 10.1136/bjo.82.7.790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Della Rocca DA, Ahmad S, Preechawi P, Schaefer SD, Della Rocca RC (2007) Nasolacrimal system injuries, chapter 9. In: Atlas of lacrimal surgery. Springer, Berlin, pp 91–104

- 25.Rosen N, Sharir M, Moverman DC, Rosner M. Dacryocystorhinostomy with silicon tubes: evaluation of 253 cases. Ophthalmic Surg. 1982;20:115–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vieira GS, Xavier ME. Results and complications of bicanalicular intubation in external dacryocystorhinostomy. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2008;71(4):529–533. doi: 10.1590/S0004-27492008000400012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]