Abstract

Background

Surrogate accuracy in predicting patient treatment preferences (i.e., what patients want) has been studied extensively, but it is not known whether surrogates can predict how patients want loved ones to make end-of-life decisions on their behalf.

Objective

To evaluate the ability of family members to correctly identify the preferences of seriously-ill patients regarding family involvement in decision making.

Design

Cross-sectional survey.

Participants

Twenty-five pancreatic cancer and 27 amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) patients and their family members (52 dyads total).

Main Measures

Patients and family members completed the Decision Control Preferences (DCP) scale regarding patient preferences for family involvement in health care decisions using conscious and unconscious scenarios.

Key Results

Patient and family member agreement was 56% (29/52 dyads) for the conscious scenario (kappa 0.29) and 46% (24/52 dyads) for the unconscious scenario (kappa 0.15). Twenty-four family members identified the patient’s preference as independent in the unconscious scenario, but six of these patients actually preferred shared decision making and six preferred reliant decision making. In the conscious scenario, preference for independent decision making was associated with higher odds of patient–family agreement (AOR 5.28, 1.07–26.06). In the unconscious scenario, cancer patients had a higher odds of agreement than ALS patients (AOR 3.86; 95% CI 1.02–14.54).

Conclusion

Family members were often unable to correctly identify patient preferences for family involvement in end-of-life decision making, especially when patients desired that decisions be made using the best-interest standard. Clinicians and family members should consider explicitly eliciting patient preferences for family involvement in decision making. Additional research is still needed to identify interventions to improve family member understanding of patient preferences regarding the decision-making process itself.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11606-011-1717-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: decision making, patient preference, advance care planning, terminal care

INTRODUCTION

Clinicians frequently rely on surrogate decision makers in end-of-life decision making, particularly when patients become incapacitated.1 In these settings, surrogates are often asked to use the substituted judgment standard, which requires them to make the treatment decision that the patient would have made if he or she had decision-making capacity. However, multiple studies have shown that surrogates are frequently unable to accurately predict patients’ treatment preferences.2–10 In addition, we have found that terminally-ill patients vary considerably in the role they want their surrogates to play in the decision-making process,11,12 and that a slight majority of patients actually prefer that surrogates’ best-interest judgments guide decision making, even if the decision were to contradict a hypothetically perfect living will.13

Although previous studies have revealed that surrogates are inaccurate in predicting what decisions patients would want made at the end of life, little is known about surrogates’ ability to predict how patients would want decisions made at the end of life. There is evidence that physicians often do not address preferences related to family involvement in decision making even in the setting of intensive care unit (ICU) family meetings 14 and that families do not use pure substituted judgments when making decisions on behalf of their loved ones.15,16

It is not known, however, whether surrogate decision makers can accurately identify patient preferences regarding family involvement in decision making. Since family members make up the vast majority of surrogate decision makers, we chose to assess preferences for family involvement in decision making using patient–family member dyads. The primary objective of the study was to evaluate the ability of family members to correctly identify the preferences of seriously-ill patients regarding family involvement in decision making. As a second study objective, we also sought to explore the association between patient and family characteristics and patient–family member agreement on preferences for family involvement.

METHODS

Study Design, Subjects, and Setting

Patients diagnosed with either amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) or advanced pancreatic cancer were approached in the ALS and GI surgery clinics, respectively, at The Johns Hopkins Hospital for participation in this pilot study. These two patient groups were chosen to capture very different disease trajectories; one in which patients were likely to retain decision-making capacity close to death (ALS) and the other in which they were likely to lose decision-making capacity close to death (end stage cancer). Eligible patients had to be 18 years of age or older, English speaking, and accompanied to the clinic by a family caregiver. Patient participants were asked to identify the family member who would most likely be involved in making decisions about the patient’s health care. With the patient’s consent, family members were then approached by the investigator for participation in the study. Family members were required to be at least 18 years of age to participate. After providing written informed consent, patients’ cognitive status was assessed using the Pfeiffer /SPMSQ17 and patients with greater than five errors were excluded from further participation in the study. Family members also completed the Pfeiffer/SPMSQ if they were over the age of 80 with the same exclusion criterion. Patients and family members completed surveys about demographic information, health status, and the patient’s decision control preferences. The protocol was approved by a Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Decision Control Preference

Decision control preferences were assessed using the previously developed Patient–Family Decision Making version11 of the Decision Control Preferences (DCP) Scale.18–22 Prior to completing the scale, patients were asked to identify an important health care decision that was recently made or was about to be made. They were then asked their preference for family involvement in that decision using the DCP scale. Family members were then separately asked to identify what they thought was the patient's preference for involving family in making the decision that was specified by the patient. We chose this approach as prior research has shown that surrogates are less accurate in predicting patient preferences in response to hypothetical scenarios compared to situations involving the patient’s current health.2

The Patient–Family Decision Making version of the DCP scale consisted of captioned illustrations depicting five control preference choices for two different scenarios: the supposition that the patient was conscious and the supposition that the patient was unconscious. For the conscious scenario in which the patient has decision-making capacity, the response options range from no involvement (independent decision making by the patient), through shared patient–family decision making, to decision making that is reliant upon the family member (See online Appendix). For the unconscious scenario in which the patient lacks decision-making capacity, the response options ranged from independent decision making based on the patient's previously stated wishes (substituted judgment standard) through shared patient–family decision making (a mixture of substituted judgment and best interests standard) to decision making that was based on what the family thinks is best for the patient (best interests standard) (See online Appendix).

Patient and Family Member Characteristics

Patient and family member socio-demographic characteristics were measured by self-report, and included age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, religion, and education. The importance of religion was assessed using a three point Likert scale: very important, somewhat important, and not important. Time since diagnosis was based on patient self-report. As part of the survey, patients were also asked whether or not they had a living will or an identified durable power of attorney for health care. For ALS patients, health status was assessed using the revised ALS functional rating scale (ALSFRS).23 Cancer patients were assessed using the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Performance Status.24 Family members were asked to specify their relationship to the patient and if they had any previous experience helping a family member with decision making.

Statistical Analysis

Sample sizes greater than 30 are generally considered to provide adequate power for assessing inter-rater reliability using kappa.25 Given our small sample size, we trichotomized the five DCP responses, as previously described,11,12,26 into the following categories for both the conscious and unconscious scenarios: independent (A, B), shared (C), and reliant (D, E). We then evaluated patient–family member concordance for the conscious and unconscious scenarios by calculating Kappa scores and percent agreement.

Next, we explored the association between patient and family member characteristics and patient–family member agreement using chi-squared tests followed by univariate and multivariate logistic regression. To avoid problems with overfitting, we included no more than four independent variables in our multivariate analyses. We forced the two most relevant variables from the perspective of clinical ethics (presence of an advance directive and decision control preference) into both models, then added up to two more independent variables chosen on the basis of strength of univariate association and sufficient cell size. Based on these criteria, the model selected for the conscious scenario included adjustment for patient age, presence of advance directive, decision control preference, and family member education level. The multivariate regression model for the unconscious scenario included adjustment for type of disease (ALS vs. cancer), presence of advance directive, decision control preference, and family member education level. All data analyses were conducted using Stata Version 10.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

Fifty-two patient–family member dyads completed the DCP scale. Twenty-seven of these dyads consisted of patients with ALS and their family members while the other 25 dyads consisted of pancreatic cancer patients and their family members. Table 1 displays the characteristics of the study sample. The patient sample was 81% white, 65% male, and had a mean age of 58.6 +/− 10.1 years. Seventy-three percent of the ALS patients had an advance directive while only 32% of pancreatic cancer patients had one. The family member sample was 81% white, 65% female, and had a mean age of 55.9 +/− 11.5 years. The majority of patients and family members had at least a college education. Eighty-one percent of family members self-identified as spouses, and 71% had previous experience with helping a family member with decision making. The recent important health care decisions identified by patients fell into four categories: 1) Where to seek care (e.g., where to get surgery, whether to go to “x” hospital for treatment) (n = 20) ; 2) Treatment decisions (e.g., getting a diaphragm pacer, having surgery) (n = 23); 3) Advance care planning (e.g., whether to be DNR/DNI, stopping aggressive treatment if brain dead) (n = 4); and 4) Quality of life (e.g., taking medicine even though it makes the patient sick) (n = 5).

Table 1.

Study Sample Characteristics

| Patients | Family Members | |

|---|---|---|

| (n = 52) | (n = 52) | |

| Age – yrs | ||

| Mean (SD) | 58.6 (10.1) | 55.9 (11.5) |

| Gender (%) | ||

| Female | 34.6 | 65.4 |

| Race (%) | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 80.8 | 80.8 |

| Black | 11.5 | 9.6 |

| Hispanic | 7.7 | 5.8 |

| Other * | 0 | 3.8 |

| Education (%) | ||

| High school | 31.4 | 30.8 |

| College | 37.3 | 40.4 |

| Graduate school | 31.4 | 28.9 |

| Marital status (%) | ||

| Married | 88.5 | 92.3 |

| Divorced | 5.8 | 7.7 |

| Never married | 3.9 | 0 |

| Widowed | 1.9 | 0 |

| Religion (%) | ||

| Protestant | 47.1 | 46.2 |

| Catholic | 43.1 | 32.7 |

| Other Christian + | 9.8 | 13.5 |

| None | 0 | 7.7 |

| Importance of religion (%) | ||

| Very important | 54.9 | 63.5 |

| Somewhat important | 37.3 | 25.0 |

| Not important | 7.8 | 11.5 |

| Disease (%) | ||

| ALS | 51.9 | |

| Cancer | 48.1 | |

| Time since diagnosis (months) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 18.9 (31.5) | |

| ECOG (%) ** | ||

| 0 | 68.0 | |

| 1 | 28.0 | |

| 2 | 4.0 | |

| ALSFRS-R (%) ++ | ||

| Mean (SD) | 34.4 (7.3) | |

| Advance Directive (%) ^ | ||

| Yes | 52.9 | |

| Previous experience helping family member with decision making (%) | ||

| Yes | 71.2 | |

| Relationship to patient (%) | ||

| Spouse | 80.8 | |

| Child | 1.9 | |

| Parent | 5.8 | |

| Sibling | 5.8 | |

| Other relative | 1.9 | |

| Other | 3.9 | |

* “Other” included one multiracial and one Asian family member

+ “Other Christian” included the following responses: Christian (n = 2), Methodist (n = 2), LDS (n = 1), Wesleyan (n = 1), and Spiritualist (n = 1)

** ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. N = 25

++ ALSFRS-R, ALS Functional Rating Scale (Revised); Scale ranges from 0 (worst) to 48 (best). N = 27 for seven patients

^ Patients answered a single question about whether or not they had any of the following: an advance directive, a living will, or identification of a health care power of attorney

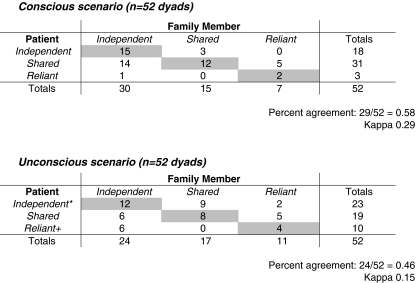

Patient and family member responses to the DCP scale for the conscious and unconscious scenarios can be seen in Table 2. On the supposition that they were conscious and had decision-making capacity, 18 patients (35%) preferred independent decision making, 31 (59%) preferred shared decision making, and 3 (6%) preferred to rely on the family to make decisions for them. Among family members, 30 (58%) thought their loved ones preferred independent decision making, 15 (29%) thought they preferred shared decision making, and 7 (13%) thought they preferred to rely on family to make decisions. Patients and their family members agreed on decision control preferences in 29/52 dyads (56%) for the conscious scenario (kappa 0.29). In the 30 cases in which the family member identified the patient’s preference as independent, 14 patients had actually identified a preference for shared decision making.

Table 2.

Patient–Family Member Agreement on the Decision Control Preferences Scale

Note: Shaded areas indicate concordance between patient and family member responses

* A preference for independent decision control refers to the substituted judgment standard in the unconscious scenario

+ A preference for reliant decision control refers to the best interests standard in the unconscious scenario

For the unconscious scenario, 23 (44%) patients preferred that decisions be based only on their wishes (substituted judgment standard), 19 (37%) preferred that decisions be based equally on patient wishes and what the family thinks is best, and 10 (19%) preferred that decisions be made based on what the family thinks is best (best interests standard). Twenty-four family members (46%) thought their loved ones preferred independent decision making (substituted judgment), 17 (33%) thought they preferred shared decision making, and 11(21%) thought they preferred to rely on family to make decisions (best interests standard). Patients and their family members agreed on decision control preferences in 24/52 dyads (46%) for the unconscious scenario (kappa 0.15). In the 24 cases in which the family member identified the patient’s preference as independent, six patients had actually identified a preference for shared decision making and six identified a preference for reliant decision making.

Table 3 displays the regression results for the association between patient and family member characteristics and odds of patient–family member agreement on decision control preferences for the conscious scenario. Compared to preference for shared decision making, patient preference for independent decision making was significantly associated with a higher odds of agreement (AOR 5.28, 1.07–26.06). There was no significant association between odds of agreement and patient age, presence of an advance directive, and family member education level in the multivariate model.

Table 3.

Odds of Patient–Family Member Agreement for the Conscious Scenario

| Univariate Model | Multivariate Model * | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Patient characteristics | ||||||

| Age | 1.07 | (1.01-1.14) | 0.03 | 1.05 | (0.98-1.13) | 0.19 |

| AD | ||||||

| No (ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Yes | 2.80 | (0.90-8.75) | 0.08 | 2.20 | (0.56-8.64) | 0.26 |

| DCP | ||||||

| Shared (ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Independent | 7.92 | (1.89-33.24) | 0.01 | 5.28 | (1.07-26.06) | 0.04 |

| Reliant | 3.17 | (0.26-38.84) | 0.37 | 4.15 | (0.22-78.38) | 0.34 |

| Family member characteristics | ||||||

| Education | ||||||

| HS (ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| College | 0.30 | (0.08-1.10) | 0.07 | 0.27 | (0.06-1.25) | 0.09 |

* Adjusted for patient age, presence of an advance directive (AD), decision control preference (DCP), and family member education level (HS = high school). Models which adjusted for family member age, gender, relationship to patient, and prior experience with decision making did not significantly alter the results presented.

^ Blacks, Hispanics, and those who identified themselves as other were grouped as “Non-white” given small numbers. Analysis of these separate groups did not significantly alter results.

The regression results for the association between patient and family member characteristics and patient–family member agreement on decision control preferences for the unconscious scenario are displayed in Table 4. There was no significant association between odds of agreement and presence of an advance directive, decision control preference, and family member education level in the multivariate model. Cancer patients had a higher odds of agreement than ALS patients (AOR 3.86; 95% CI 1.02-14.54).

Table 4.

Odds of Patient–Family Member Agreement for the Unconscious Scenario

| Univariate Model | Multivariate Model * | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Patient characteristics | ||||||

| Disease | ||||||

| ALS (ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Cancer | 3.00 | (0.97-9.30) | 0.06 | 3.86 | (1.02-14.54) | 0.05 |

| AD | ||||||

| No (ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Yes | 0.80 | (0.27-2.41) | 0.69 | 1.43 | (0.39-5.26) | 0.59 |

| DCP | ||||||

| Shared (ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Independent | 1.50 | (0.44-5.10) | 0.52 | 1.76 | (0.47-6.63) | 0.40 |

| Reliant | 0.92 | (0.19-4.36) | 0.91 | 0.73 | (0.14-3.75) | 0.71 |

| Family member characteristics | ||||||

| Education | ||||||

| HS (ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| College | 0.56 | (0.17-1.83) | 0.33 | 0.48 | (0.13-1.74) | 0.27 |

* Adjusted for presence of an advance directive (AD), type of disease (ALS vs. cancer), decision control preference (DCP), and family member education level (HS = high school). Models which adjusted for family member age, gender, relationship to patient, and prior experience with decision making did not significantly alter the results presented

^ Blacks, Hispanics, and those who identified themselves as other were grouped as “Non-white” given small numbers. Analysis of these separate groups did not significantly alter results

DISCUSSION

End-of-life decision making is an extremely complicated and poorly understood process and often places significant burden on surrogate decision makers who are asked to exercise the substituted judgment standard when patients are no longer capable of making decisions themselves.27,28 Yet given findings suggesting that some patients prefer their surrogates to have a more active role in the decision-making process,11 surrogates should be aware of patient preferences regarding the decision-making process itself. While prior literature has shown that surrogate decision makers are often unable to accurately predict what decisions patients want made at the end of life,2–10 our study suggests that surrogates may also be unable to accurately predict patient preferences regarding how they want decisions made with regard to surrogate involvement in the decision-making process.

Among a sample of seriously-ill ALS and pancreatic cancer patients, we found that family members were frequently unable to correctly identify patient preferences regarding family involvement in decision making and had an especially difficult time correctly identifying patient preferences in the unconscious scenario. In particular, family members were most likely to err by attributing to the patient a preference for substituted judgment when the patient actually preferred shared decision making or would defer to the family’s best judgment.

We did not find an association between presence of an advance directive and patient–family member agreement for either scenario. This finding echoes findings from multiple other studies which found that advance directives do not improve surrogate prediction of patient treatment preferences.6,29,30 Since most advance directives do not require patients to specify their preferences regarding the level of family involvement in decision making, our findings are not surprising but rather highlight a deficiency with the current way in which advance directives are constructed.

In the conscious scenario only, a preference for independent rather than shared decision making was associated with higher surrogate agreement. One possible explanation for this finding is that while preferences for independent decision making may be more readily expressed or recognized when patients are conscious and actually making decisions, they may not uniformly predict how patients would prefer decisions be made should they become unable to make decisions for themselves. This may be because patients value the exercise of free choice more than the precise content of their preferences.31 Our finding that there was less agreement among ALS patients and their families than among cancer patients in the unconscious scenario gives further credence to this interpretation. Since ALS patients often retain decision-making capacity long into the course of their illness, families may automatically misinterpret a pattern of independent decision making while conscious as a preference for substituted judgment when unconscious.

This study has several limitations. Despite the inclusion of two distinct terminally-ill populations with very different disease trajectories, our overall sample size for this pilot study was small and, therefore, larger studies are required to corroborate our results. In addition, we recruited participants from a single urban, academic center and our study sample had higher education levels and lacked ethnic diversity. Therefore, the generalizability of our findings to patients in other settings is limited. Next, patients completed the DCP based on the decision they had identified and it is possible that patient preferences for other aspects of end-of-life decision making may have differed from those related to this one decision and that some of the decisions selected may have been more appropriate for the conscious scenario. Nonetheless, our findings suggest that in terms of a single “real-life” decision that is deemed important by the patient, there is considerable discordance between patients and family members. Moreover, we found that family members were unable to accurately predict patient preferences as they related to a wide range of decisions including those related to treatment options, where to seek care, and advance care planning. Since previous studies suggest that surrogates are most accurate in predicting patient treatment preferences in situations involving the patient’s current health rather than in hypothetical scenarios,2 our findings of surrogate inaccuracy for decision-making preferences related to patients’ actual decisions are particularly noteworthy.

This study suggests that family members do not accurately understand the role the patient would like them to play in the decision-making process. Because family members may play a crucial role in end-of-life decision making, clinicians and family members should consider explicitly eliciting patient preferences for family involvement in decision making. Family meetings may be one venue for such discussion.32 Patients desiring to share the decision-making process with their family members should make a concerted effort to communicate this preference to their family. For example, advance directives may be modified to communicate patients’ preferences for how they want decisions to be made, rather than merely specifying their preferences for or against particular medical interventions. Another approach which merits further investigation is the modification of advance directives to include patient preferences regarding the amount of “leeway” they want their surrogates to have when making decisions,33–35 as has been done by the State of Maryland.36 Additional research is still needed to identify specific interventions to improve family member understanding of patient preferences regarding decision making at the end of life and how this might impact future decisions.

ELECTRONIC SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Decision Control Preferences Scale (DOC 729 kb)

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Christine St. Ours, Project Coordinator, and Marian Grant, Project Director, for their assistance with data collection.

Funding Source This study was funded by the National Institute for Nursing Research at the National Institutes of Health NIH, R01 NR010733.

Conflicts of Interest None disclosed.

Prior Presentations Partial data from this study were presented at the Society of General Internal Medicine’s 33rd Annual Meeting in Minneapolis, Minnesota on May 1, 2010 and at the American Society for Bioethics and Humanities Annual Meeting in San Diego, California on October 22, 2010.

References

- 1.Arnold RM, Kellum J. Moral justifications for surrogate decision making in the intensive care unit: implications and limitations. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(5 Suppl):S347–353. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000065123.23736.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shalowitz DI, Garrett-Mayer E, Wendler D. The Accuracy of Surrogate Decision Makers: A Systematic Review. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(5):493–497. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.5.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seckler AB, Meier DE, Mulvihill M, Paris BE. Substituted judgment: how accurate are proxy predictions? Ann Intern Med. 1991;115(2):92–98. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-115-2-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uhlmann RF, Pearlman RA, Cain KC. Physicians' and spouses' predictions of elderly patients' resuscitation preferences. J Gerontol. 1988;43(5):M115–121. doi: 10.1093/geronj/43.5.m115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hare J, Pratt C, Nelson C. Agreement between patients and their self-selected surrogates on difficult medical decisions. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152(5):1049–1054. doi: 10.1001/archinte.152.5.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sulmasy DP, Terry PB, Weisman CS, et al. The accuracy of substituted judgments in patients with terminal diagnoses. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128(8):621–629. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-8-199804150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sulmasy DP, Haller K, Terry PB. More talk, less paper: predicting the accuracy of substituted judgments. Am J Med. 1994;96(5):432–438. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(94)90170-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suhl J, Simons P, Reedy T, Garrick T. Myth of substituted judgment. Surrogate decision making regarding life support is unreliable. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154(1):90–96. doi: 10.1001/archinte.154.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zweibel NR, Cassel CK. Treatment choices at the end of life: a comparison of decisions by older patients and their physician-selected proxies. Gerontologist. 1989;29(5):615–621. doi: 10.1093/geront/29.5.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pruchno RA, Lemay EP, Jr, Feild L, Levinsky NG. Spouse as health care proxy for dialysis patients: whose preferences matter? Gerontologist. 2005;45(6):812–819. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.6.812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nolan M, Hughes M, Narendra D, et al. When patients lack capacity: the roles that patients with terminal diagnoses would choose for their physicians and loved ones in making medical decisions. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;30(4):342–353. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sulmasy DP, Hughes MT, Thompson RE, et al. How would terminally ill patients have others make decisions for them in the event of decisional incapacity? A longitudinal study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(12):1981–1988. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01473.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Terry PB, Vettese M, Song J, et al. End-of-life decision making: when patients and surrogates disagree. J Clin Ethics. 1999;10(4):286–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.White DB, Braddock CH, III, Bereknyei S, Curtis JR. Toward shared decision making at the end of life in intensive care units: opportunities for improvement. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(5):461–467. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.5.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vig EK, Taylor JS, Starks H, Hopley EK, Fryer-Edwards K. Beyond substituted judgment: how surrogates navigate end-of-life decision-making. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(11):1688–1693. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirschman KB, Kapo JM, Karlawish JH. Why doesn't a family member of a person with advanced dementia use a substituted judgment when making a decision for that person? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(8):659–667. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000203179.94036.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pfeiffer E. A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1975;23(10):433–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1975.tb00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Degner LF, Davison BJ, Sloan JA, Mueller B. Development of a scale to measure information needs in cancer care. J Nurs Meas. Winter. 1998;6(2):137–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Degner LF, Kristjanson LJ, Bowman D, et al. Information needs and decisional preferences in women with breast cancer. JAMA. 1997;277(18):1485–1492. doi: 10.1001/jama.277.18.1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Degner LF, Sloan JA, Venkatesh P. The Control Preferences Scale. Can J Nurs Res. Fall. 1997;29(3):21–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davison BJ, Degner LF, Morgan TR. Information and decision-making preferences of men with prostate cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1995;22(9):1401–1408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Degner LF. Preferences to participate in treatment decision making: the adult model. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 1998;15(3 Suppl 1):3–9. doi: 10.1016/S1043-4542(98)90069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cedarbaum JM, Stambler N, Malta E, et al. The ALSFRS-R: a revised ALS functional rating scale that incorporates assessments of respiratory function. BDNF ALS Study Group (Phase III) J Neurol Sci. 1999;169(1–2):13–21. doi: 10.1016/S0022-510X(99)00210-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5(6):649–655. doi: 10.1097/00000421-198212000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crewson PE. Reader agreement studies. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184(5):1391–1397. doi: 10.2214/ajr.184.5.01841391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nolan MT, Kub J, Hughes MT, et al. Family health care decision making and self-efficacy with patients with ALS at the end of life. Palliat Support Care 2008;6(03). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Tilden VP, Tolle SW, Nelson CA, Fields J. Family decision-making to withdraw life-sustaining treatments from hospitalized patients. Nurs Res. 2001;50(2):105–115. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200103000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sulmasy DP, Sood JR, Texiera K, McAuley RL, McGugins J, Ury WA. A prospective trial of a new policy eliminating signed consent for do not resuscitate orders. J Gen Intern Med. Sep 11 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Coppola KM, Ditto PH, Danks JH, Smucker WD. Accuracy of primary care and hospital-based physicians' predictions of elderly outpatients' treatment preferences with and without advance directives. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(3):431–440. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.3.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ditto PH, Danks JH, Smucker WD, et al. Advance directives as acts of communication: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(3):421–430. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.3.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Freedman B. On the rights of the voiceless. J Med Philos. 1978;3(3):196–210. doi: 10.1093/jmp/3.3.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharma RK, Dy SM. Cross-cultural communication and use of the family meeting in palliative care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. Dec 28 2010. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Hawkins NA, Ditto PH, Danks JH, Smucker WD. Micromanaging death: process preferences, values, and goals in end-of-life medical decision making. Gerontologist. 2005;45(1):107–117. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Emanuel L, Librach S. Palliative care: core skills and clinical competencies. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sudore RL, Fried TR. Redefining the "planning" in advance care planning: preparing for end-of-life decision making. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(4):256–261. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-153-4-201008170-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Md. Health-Gen. Code Ann. § 5–603 (2011)

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Decision Control Preferences Scale (DOC 729 kb)