Abstract

BACKGROUND

National guidelines endorse colonoscopy as the only colorectal cancer (CRC) screening test which prevents CRC and evaluates the entire large bowel. However, little is known regarding patient compliance with a screening program that exclusively uses colonoscopy, particularly in an underserved population. The Connecticut Department of Public Health provided funds for the total cost of colonoscopies, patient navigators and education of staff and primary care providers. With cost and provider barriers removed, we were able to examine patient related factors influencing compliance with colonoscopy in an ethnically diverse sample of underinsured adults.

OBJECTIVE

To determine what patient related factors are predictors of compliance with screening colonoscopy.

DESIGN

Cross sectional retrospective study.

PARTICIPANTS

Underinsured patients (50–64 years) visiting nine Connecticut community health centers (CHCs) were evaluated for medical eligibility for screening; eligible patients were offered a free colonoscopy.

MAIN MEASURES

Patients were deemed non-compliant if they refused, canceled or did not show for the colonoscopy. Obesity (Body Mass Index ≥ 30), educational attainment, gender, race, ethnicity, previous screening and social ties were examined as primary risk factors for compliance.

KEY RESULTS

Of 424 uninsured patients (62% female, 21% White, 26% Black, 53% Hispanic), 354 were eligible for colonoscopy. Among eligible patients, 263 (74.3%) were compliant. Obese patients were more likely than non-obese patients to be non-compliant with colonoscopy (adjusted odds ratio = 2.16; 95% Confidence interval = 1.20-3.89). A high school education was positively correlated with increased compliance social ties such as having a spouse, significant other, family or friend also increased compliance.

CONCLUSIONS

In an ethnically diverse, uninsured population, obese patients and patients with lower educational attainment were less likely to comply with free colonoscopy. These patients require special attention in colonoscopy-based CRC screening efforts.

KEY WORDS: colorectal cancer screening, obesity, colonoscopy

BACKGROUND

Colonoscopy, fecal occult blood testing (FOBT) of the stool and flexible sigmoidoscopy have been the main tools recommended for colorectal cancer CRC screening. However, in the latest American Cancer Society and American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) guidelines for CRC screening, the tests are divided into those that prevent and those that detect CRC.1,2 Colonoscopy is the only recommended test that evaluates the entire bowel and prevents CRC Given current recommendations1,2, as well as health care access barriers in lower socioeconomic groups, many public health programs have been designed to screen underserved populations for CRC using colonoscopy.3,4 The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act as well as the CDC funded efforts have added CRC screening to existing breast and cervical programs. This will make screening colonoscopy more accessible to underinsured populations.

Despite efforts to endoscopically screen these populations, little is known regarding predictors of patient compliance with colonoscopy in medically underserved populations. Barriers to screening can be practitioner based5,6 such as a lack of access to referral for endoscopic screening as well as a deficit in knowledge regarding screening.7,8 In addition, there are systems based barriers such as scheduling, financial, transportation, and language difficulties.9 Finally, there are patient related factors such as age5,6,10–12, gender6,11,13–16, race6,14, ethnicity6,11,17, health insurance6,10,11,17, marital status, education level6,11,17, co-morbid illnesses7 and lifestyle characteristics18,19, such as smoking6,10–12 and obesity.20,21

Accordingly, we examined factors that were associated with compliance with free screening colonoscopy in an ethnically diverse sample of uninsured adults. In this program, funds paid for patient navigators and education for providers and staff, removing many known system and provider barriers. Thus, compliance for colonoscopy in this program could provide information regarding patient factors. Our goal was to examine the patient related factors that could predict non-compliance with colonoscopy in an underserved population.

METHODS

Demonstration Project Description

The nine participating CHCs were located in urban settings in Connecticut. Eight of these were designated as Federally Qualified Health Centers. The Connecticut Department of Public Health supported the colonoscopy screening program in these CHCs between December 2008 and June 2009. The grant paid for the total payment of the colonoscopies as well as education of providers and staff. Education was provided through didactic sessions or conference calls. This included information regarding eligibility, scheduling procedures and preparation for endoscopic procedures. The grant paid for a medical director who educated providers and staff, screened patients and assisted in the medical care and follow up. The grant did not provide transportation or an accompanying driver.

Patient Eligibility

CHC staff evaluated patients’ eligibility which required patients to be underinsured Connecticut residents aged 50–64 years. Underinsured was defined as having no health insurance or health insurance that did not cover colonoscopy. Medically eligible patients had to be medically stable, have no lower gastrointestinal complaints, and they could not have had a colonoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy in the previous ten years. However, patients who had other CRC screening tests such as FOBT were eligible. Eligible patients were invited either by their primary care practitioner or a bilingual patient navigator for a free colonoscopy. A pre-endoscopy form included age, gender, height and weight collected by a clinical assistant, ethnicity, race, language, marital status, next of kin, educational level, family history of CRC and other cancers, previous CRC tests, smoking history, alcohol use, gastrointestinal symptoms, medical problems, systems review, and medications including those for anti-coagulation. The form recorded patients’ overall eligibility, practitioners’ recommendation for the colonoscopy, and patients’ assent or refusal for the colonoscopy and was reviewed by the medical director.

Endoscopy Scheduling

Bilingual patient navigators, paid by the grant, facilitated the process of scheduling and instructing the patients with respect to the preparation for the procedures. These navigators gave patients procedure dates and times, explained the cleansing process and provided directions to the endoscopy appointments. We used an open endoscopy model, booking patients directly without an office visit with the gastroenterologist. Participating gastroenterologists attended seminars regarding quality of colonoscopy lead by the medical director. The participating gastroenterologists promised to provide endoscopy appointments within 2 weeks of the visit with the primary practitioner. The eligibility form was confirmed by a gastroenterologist who reviewed pre-endoscopy forms. Endoscopy reports were sent back with data regarding patients who cancelled or did not show to the appointment.

Study

The Institutional Review Board of the University of Connecticut Health Center approved our study. No consent was required since we de-identified all patient data prior to conducting any analyses. This included data collected in the process of evaluating patients for medical eligibility for colonoscopy screening and findings of completed open endoscopies.

Variable Measurement and Data Analysis Procedures

Our main outcome was patient non-compliance, determined by whether they attended their colonoscopy. Patients were considered non-complaint if they: refused at the time they were offered the free colonoscopy screening; made but then canceled the screening appointment without rescheduling; or made but did not show for the appointment. The time period for assessing compliance was the 6 month period of funding during which colonoscopies were scheduled. BMI was calculated as (weight in kg) / (height in m)2 and obesity was defined as BMI ≥ 30. Although we examined BMI by four groups (< 25, ≥ 25 to < 30, ≥ 30 to < 35 and ≥ 35), our final analyses used obese vs. non-obese patients based on literature and clinical significance. Additional covariates included gender (male or female), race (white, black, Asian or other), ethnicity (Hispanic vs. non-Hispanic), education (high school or less), language spoken (English, Spanish or other), employment status (unemployed, part time or full time), next of kin (spouse/significant other, family, friend or none), smoking status (current, quit or never), alcohol use (drinks per week), aspirin use (yes or no) , medication use (yes or no), multivitamin use, location of procedure (site number), medical illnesses (yes or no for medical conditions) family history of CRC (age and relative) and past CRC screening (type of test, year performed and outcome).

We first conducted bivariate analyses using Chi square tests to determine which independent variables were associated with compliance. For predictors with more than two categories, each category was compared to all other categories combined to determine associations with compliance. Next, univariate logistic regression models tested for unadjusted predictors of compliance. We then conducted multivariate logistic regression analysis with compliance as the dependent variable, entering into the model, all covariates with p values ≤ 0.1 included in univariate logistic model tests. Correlations coefficients among predictor variables revealed a significant relationship (r = 0.95) between race and language; therefore, race and not language was initially used in the model. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals indicated the effect of each predictor and whether it met statistical significance. Tests with a p-value of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software was used to analyze all data (version 17.0).

Since studies examining compliance in CRC have observed differences between men and women21,22, we divided gender into two separate regression models to assess compliance among men and women separately. Additionally, we further examined compliance after stratifying by race/ethnicity.

RESULTS

A total of 424 patients (62% female, 53% Hispanic, 27% African American) were evaluated for medical eligibility. Of these, 70 patients were deemed medically ineligible due to being medically unstable, having gastrointestinal symptoms, or having had previous endoscopic screening. There were 354 medically eligible and uninsured patients. They were offered a free colonoscopy and 263 (74.3%) completed a colonoscopy and 91 (25.7%) were non-compliant (47(51.6%) refused, 23 (25.3%) did not show and 21(23.1%) cancelled); characteristics of those who were compliant and non-compliant are compared in Table 1. Obesity was associated with non-compliance; 46% of compliant patients were obese, while 70% of non-compliant patients were obese (p < 0.001). The compliance across four BMI groups (< 25, ≥ 25 to < 30, ≥ 30 to < 35 and ≥ 35) were 90.0%, 80.3%, 68.2% and 66.0% respectively (p = 0.02 by Chi Square). We also examined BMI as a continuous variable and found that increasing BMI was associated with an increase in non-compliance (OR = 1.05, 95% Confidence Interval: 1.–2-1.09) (p = 0.006). Having a high school education, and having a spouse or significant other, were each associated with compliance with colonoscopy screening (both p < 0.05). Older age and having had previous CRC screening approached statistical significance with respect to compliance (all p < 0.10).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients Who Were Compliant and Non-compliant with Free Colonoscopy Screening

| Compliant (Completed Screenings) | Non-Compliant (Refused/ Cancelled/no show) | p value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 263) | (n = 91) | ||

| N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Obese (BMI ≥ 30) | 117 (46) | 63 (70) | <0.001 |

| Age | 55.3 ± 4.2 | 56.2 ± 4.4 | 0.10 |

| Gender | 0.94 | ||

| Males | 100 (38) | 35 (38) | |

| Females | 163 (62) | 56 (62) | |

| High school graduate | 167 (70) | 49 (56) | 0.02 |

| Smoking status | |||

| Smoker | 42 (16) | 19 (21) | 0.27 |

| Nonsmoker | 55 (21) | 19 (21) | 0.97 |

| Past smoker | 166 (63) | 58 (52) | 0.37 |

| Race | |||

| White | 52 (20) | 19 (21) | 0.81 |

| Black | 73 (28) | 18 (20) | 0.14 |

| Other | 136 (52) | 53 (59) | 0.27 |

| English language | 119 (45) | 39 (43) | 0.67 |

| Employed FT or PT | 112 (46) | 36 (44) | 0.75 |

| Diabetic | 58 (22) | 24 (27) | 0.38 |

| Medical condition | 157 (60) | 57 (63) | 0.57 |

| Past CRC screening test | 70 (27) | 16 (18) | 0.09 |

| Family History of CRC | 19 (7) | 3 (3) | 0.19 |

| Next of Kin | |||

| Spouse/Significant other | 104 (40) | 25 (28) | 0.04 |

| Friend | 49 (19) | 16 (18) | 0.82 |

| Other family | 93 (35) | 30 (33) | 0.68 |

| No family | 17 (7) | 20 (22) | <0.001 |

| Aspirin | 75 (29) | 32 (36) | 0.21 |

| Multivitamin | 17 (7) | 3 (3) | 0.26 |

*p value based on chi square tests or (for age) independent sample t test

When compared to non-obese patients, people who were obese were less likely to have some high school education, to have past CRC screening, to be non-compliant and more likely to speak English and have diabetes. When examined across the 4 BMI groups the prevalence of high school education was 85.1%, 66.6%, 61.4% and 59.7%, respectively (p = 0.02 by Chi-Square).

Table 2 shows results of univariate and multivariate logistic regression model analyses where compliance or non-compliance was the dependent variable. Because they were associated with compliance at the bivariate level (at p < 0.10), the following predictors were included in the multivariate logistic regression model: obesity, educational level, next of kin, age, and past CRC screening. Due to differences between obese and non-obese patients, we also added language and diabetes mellitus. In addition, we added smoking, gender and employment due to their importance in compliance. After multivariate analysis, obese patients were more likely to be non-compliant with screening than non-obese patients (OR = 2.16; 95% CI = 1.20–3.89). Patients with spouses, friends, and other family were significantly (p < 0.01) more likely to attend a colonoscopy than patients without next of kin. In addition, those patients with a High School education were less likely to be non-compliant than those with less education (OR = 0.55; 95% CI = 0.–0-0.98). When we analyzed compliance by gender, we observed that obese men (OR = 2.27; 1.04–4.55) were as likely to be non-compliant as obese women (OR = 2.70; 1.–2-4.54).We specifically tested for the interaction between obesity and education with regard to non-compliance and found no significant relationship.

Table 2.

Univariate and Multivariate analyses for non Compliance with a Colonoscopy Screening

| Univariate OR | 95% CI | Multivariate OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI ≥ 30 | *2.66 | 1.54–4.24 | *2.16 | *1.20–3.89 |

| Age | 1.05 | 0.99–1.11 | 1.04 | 0.96–1.10 |

| Females | 0.98 | 0.60–1.60 | 0.88 | 0.49–1.60 |

| High school graduate | *0.55 | 0.33–0.91 | *0.55 | *0.30–0.98 |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Smoker | 1.46 | 0.77–2.79 | 2.04 | 0.95–4.41 |

| Past smoker | 1.16 | 0.63–2.16 | 1.36 | 0.68–2.69 |

| Nonsmoker as reference grp | – | ––– | ||

| Race | ||||

| Black | 0.63 | 0.34–1.16 | – | ––– |

| White | 0.94 | 0.51–1.72 | – | ––– |

| Other as reference grp | – | ––– | ||

| Employed FT or PT | 0.93 | 0.56–1.52 | 0.83 | 0.61–1.89 |

| English language | 0.90 | 0.56–1.49 | 1.03 | 0.60–1.56 |

| Diabetic | 1.10 | 0.73–2.19 | 1.05 | 0.54–1.97 |

| Past CRC screening test | 0.60 | 0.33–1.09 | 0.69 | 0.35–1.35 |

| Family History of CRC | 0.45 | 0.13–1.54 | – | ––– |

| Family History of POL | 2.50 | 0.75–8.33 | – | ––– |

| Next of Kin | ||||

| Spouse/Significant other | *0.20 | 0.09–0.45 | *0.18 | *0.07–0.48 |

| Friend | *0.28 | 0.12–0.66 | *0.23 | *0.08–0.70 |

| Other family | *0.28 | 0.13–0.59 | *0.22 | *0.08–0.59 |

| None as reference grp | 1.0 | ––– | ||

| Aspirin | 1.39 | 0.83–2.27 | – | ––– |

| Multivitamin | 0.50 | 0.14–1.72 | – | ––– |

| Site | 1.06 | 0.98–1.16 | – | ––– |

*p value < 0.05 based on logistic regression analysis

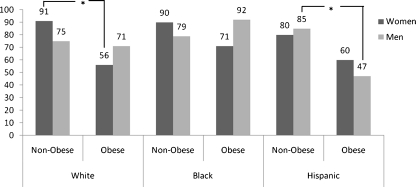

With respect to subgroup analyses by race and gender, we found that obese white women were more likely to be non-compliant with colonoscopy than their thinner counterparts. This was not observed in black or Hispanic women. With respect to men, obese Hispanic men were the least likely to be compliant when compared to their thinner counterparts. These results are shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Obese vs. non-obese patients’ compliance for a free colonoscopy screening, stratified by race/ethnicity and gender (N = 354).

DISCUSSION

In this study of uninsured adults who were offered a free screening colonoscopy, we found that obese patients (BMI ≥ 30) were less likely than non-obese patients to comply with endoscopic CRC screening. Not having a high school education and not having social ties were also associated with lower compliance for screening. In addition, we observed that obese patients had lower levels of education, were more likely to have diabetes mellitus and less likely to have received previous CRC screening such as FOBT.

Our study provides unique data regarding the compliance with CRC screening using colonoscopy. These data are important since colonoscopy is the preferred test recommend by the ACG.2 Previous studies examining compliance of obese patients were performed primarily examining FOBT, sigmoidoscopy21 with a few examining a combination including colonoscopy.22,23

Moreover, we found that, among patients who had a colonoscopy, obese patients were 4 times more likely to have an adenoma (OR = 3.62; 95% CI = 1.71–7.68). This finding supports our previous studies demonstrating obesity as a significant risk factor.24,25 Our findings also underscore the importance of screening in obese patients. While family history and age have been accepted as the important risk factors to be considered when screening for CRC, obesity may be also be an important factor.24 The most recent guidelines from the ACG have highlighted obesity as an important risk for CRC.2 Their recommendation that obese patients may need earlier screening was tempered only by the recognition that these patients may have co-morbidities that decrease the benefit from screening. Obesity is a risk factor which will be increasingly important due to the rising prevalence in the United States.26 Thus, having novel data regarding compliance with colonoscopy is important for potential new paradigms regarding CRC screening.

We observed a decrease in compliance rate among obese patients for both the genders. Rosen and colleagues observed decreased compliance among obese women but not men for any CRC test.22 Heo et al. found a decreased compliance for sigmoidoscopy among obese women but an increased compliance for obese men.21 Ferrante et al. observed a decreased rate for both genders23 for any CRC screening which included fecal occult blood test within 1 year, sigmoidoscopy within 5 years, colonoscopy within 10 years, or barium enema within 5 years. Our findings are unique since we focused only on colonoscopy as a screening method.

We did observe a difference between the races with obesity having the greatest negative impact on white women. James et al. have observed that within an African American population, higher weight was inversely correlated with CRC screening.27 Although there have been few studies specifically examining the issue of obesity, gender, ethnicity and race and compliance for CRC screening, there have been studies examining mammography. Some studies observed that the deterring effect of obesity on screening was observed in white women and not in black women.28 The authors hypothesized that this may be due to differences in body self-perception between black and white women. It has been shown that obese women may defer screening for breast or cervical cancer due to poor body image or embarrassment.29–31 We believe that given the nature of the colonoscopic exam, this factor may have played a role in our results as well.

There are many implications regarding our findings with regard to obesity and compliance. One logical conclusion might be to screen obese patients with another screening test other than colonoscopy. This may not be a panacea since other studies have observed a decrease in compliance among obese patients with other CRC screening tests such as FOBT and flexible sigmoidoscopy.21–23 Future studies will need to explore this issue.

We also observed a strong association between compliance and having a social network in the form of a spouse, significant other, friend or family. This finding has been observed in other studies involving African Americans.32 Having this type of social support is especially important with regard to CRC screening with colonoscopy due to the sedation required. Thus having someone to drive and accompany the patient is crucial.

Among the strengths of our study was the removal of known system barriers such as scheduling, preparation9 and financial barriers.8,9 Previous studies did not control for the insurance status of the patients which could represent a barrier to screening independent of obesity.21,22 The removal of systems barriers was achieved through the use of patient navigators which have been shown to increase the compliance in similar populations.33 Thus, we optimized our screening program to decrease the effect of known systems barriers for patients’ compliance. In addition, the participating gastroenterologists agreed to provide endoscopic appointments within a specified time period to increase compliance.

With regard to practitioner barriers, the grant also provided funds for educating staff and providers with regard to CRC screening thus reducing any provider related factors. All medically stable patients were advised to have a colonoscopy by their primary care practitioner, regardless of their status regarding obesity or other lifestyle factors. This is another strength of our study, since previous studies have examined CRC screening compliance based solely on reviews of medical records23 or administrative databases2,21, which did not allow direct ascertainment of whether practitioners had recommended the screening test to patients. It has been postulated that practitioners may not recommend screening for obese patients due to the high rate of co-morbid illnesses in this population22,34 or due to practitioner bias against obese people.35 To test the hypothesis that obese patients who refused may have been dissuaded by their practitioner, we examined those patients who agreed to be screened but cancelled or did not show to the scheduled appointment.. After excluding those who refused, obesity remained predictive of non-compliance (OR = 2.36; p = 0.03).

Removal of the systems and practitioner barriers allowed us to isolate patient factors. We examined many patient related factors such as socioeconomic and health-related factors known to influence CRC. The data collected included age, gender, race, ethnicity, language spoken, educational level, medical problems, family history of CRC, a history of other previous CRC screening tests, smoking status, alcohol use, and availability of next of kin. Moreover, our observations were made in an ethnically diverse group of uninsured patients, many of whom did not speak English.

The main limitation of our study was that it did not address why patients were non-compliant with screening. In addition, the retrospective use of a database may not account for confounding variables, limiting generalizability. For example, language differences between the obese and non-obese patients may have biased the outcome. Since there were more non-English patients in the non-obese group, it is possible that the bi-lingual navigator might have biased the results. Our study could not account for those patients with no transportation, accompanying driver or those who could not take time from work. In addition lack of compliance with screening may be associated with other poor lifestyle choices.29 Although we did not have data related to exercise and diet, we did examine smoking and co-morbid illnesses and found no significant effect from these factors upon the compliance with screening. The thinnest group (BMI < 25) had the highest compliance rate, perhaps related to healthier lifestyles. This group also had the most people with a high school education.

In summary, we observed that obese patients were less likely to comply with screening using colonoscopy. These pilot data may aid in generating hypotheses and developing future studies examining compliance with screening. Ensuring screening of this high risk population may drastically reduce CRC rates. Future studies should examine the reasons for this non-compliance among obese patients, with a focus on educational level and lifestyle factors.

Acknowledgements

Grant Support: The Connecticut Department of Public Health Grant #2008-0305 was awarded to the Community Health Center Association of Connecticut, Inc. which funded the demonstration project on which this study is based. The University of Connecticut was subcontracted.

Joseph C. Anderson, M.D.1,*, Richard H. Fortinsky, Ph.D.2, Alison Kleppinger, M.S.3, Amanda B. Merz-Beyus, M.P.H.4, Charles G. Huntington III, P.A., M.P.H5, Suzanne Lagarde, M.D.6

1 Department of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, University of Connecticut, Farmington, CT USA; study concept and design; acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; statistical analysis; obtained funding; technical or material support; study supervision

2 Center on Aging, University of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington, CT USA; study concept and design; acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; statistical analysis; obtained funding; technical or material support

3 Center on Aging, University of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington, CT USA; study supervision study concept and design; acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; statistical analysis; technical or material support

4 Community Health Center Association of CT, Newington, CT USA; study concept and design; acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; technical or material support; study supervision

5 Department of Community Medicine and Health Care, University of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington, CT USA; study concept and design; acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; technical or material support; study supervision

6 Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Digestive Disease, Yale University, New Haven, CT USA; study concept and design; acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; technical, or material support; study supervision.

We recognize the contributions of Charles Huntington who passed away prior to the publishing of the article. Without his tireless and enthusiastic input, the grant and the article would not have been possible.

Conflicts of Interest None disclosed.

References

- 1.Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(5):1570–95. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rex DK, Johnson DA, Anderson JC, Schoenfeld PS, Burke CA, Inadomi JM. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines for colorectal cancer screening 2008. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(3):739–50. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coughlin SS, Costanza ME, Fernandez ME, et al. CDC-funded intervention research aimed at promoting colorectal cancer screening in communities. Cancer. 2006;107(5 Suppl):1196–204. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seeff LC, DeGroff A, Tangka F, et al. Development of a federally funded demonstration colorectal cancer screening program. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008;5(2):A64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisher DA, Dougherty K, Martin C, Galanko J, Provenzale D, Sandler RS. Race and colorectal cancer screening: a population-based study in North Carolina. N C Med J. 2004;65(1):12–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ioannou GN, Chapko MK, Dominitz JA. Predictors of colorectal cancer screening participation in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(9):2082–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guerra CE, Schwartz JS, Armstrong K, Brown JS, Halbert CH, Shea JA. Barriers of and facilitators to physician recommendation of colorectal cancer screening. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(12):1681–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0396-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klabunde CN, Vernon SW, Nadel MR, Breen N, Seeff LC, Brown ML. Barriers to colorectal cancer screening: a comparison of reports from primary care physicians and average-risk adults. Med Care. 2005;43(9):939–44. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000173599.67470.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green AR, Peters-Lewis A, Percac-Lima S, et al. Barriers to screening colonoscopy for low-income Latino and white patients in an urban community health center. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(6):834–40. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0572-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carlos RC, Underwood W, 3rd, Fendrick AM, Bernstein SJ. Behavioral associations between prostate and colon cancer screening. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;200(2):216–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meissner HI, Breen N, Klabunde CN, Vernon SW. Patterns of colorectal cancer screening uptake among men and women in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(2):389–94. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheikh RA, Kapre S, Calof OM, Ward C, Raina A. Screening preferences for colorectal cancer: a patient demographic study. South Med J. 2004;97(3):224–30. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000078619.39604.3D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farraye FA, Wong M, Hurwitz S, et al. Barriers to endoscopic colorectal cancer screening: are women different from men? Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(2):341–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janz NK, Wren PA, Schottenfeld D, Guire KE. Colorectal cancer screening attitudes and behavior: a population-based study. Prev Med. 2003;37(6 Pt 1):627–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pressman A, DiMase JD. Screening colonoscopy in the underserved population. Med Health R I. 2009;92(8):283–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tessaro I, Mangone C, Parkar I, Pawar V. Knowledge, barriers, and predictors of colorectal cancer screening in an Appalachian church population. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(4):A123. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pollack LA, Blackman DK, Wilson KM, Seeff LC, Nadel MR. Colorectal cancer test use among Hispanic and non-Hispanic U.S. populations. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(2):A50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Senore C, Armaroli P, Silvani M, et al. Comparing Different Strategies for Colorectal Cancer Screening in Italy: Predictors of Patients' Participation. Am J Gastroenterol;105(1):188–198 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Coups EJ, Manne SL, Meropol NJ, Weinberg DS. Multiple behavioral risk factors for colorectal cancer and colorectal cancer screening status. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(3):510–6. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Menis M, Kozlovsky B, Langenberg P, et al. Body mass index and up-to-date colorectal cancer screening among Marylanders aged 50 years and older. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(3):A88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heo M, Allison DB, Fontaine KR. Overweight, obesity, and colorectal cancer screening: disparity between men and women. BMC Public Health. 2004;4:53. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-4-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosen AB, Schneider EC. Colorectal cancer screening disparities related to obesity and gender. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(4):332–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30339.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferrante JM, Ohman-Strickland P, Hudson SV, Hahn KA, Scott JG, Crabtree BF. Colorectal cancer screening among obese versus non-obese patients in primary care practices. Cancer Detect Prev. 2006;30(5):459–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson JC, Messina CR, Dakhllalah F, et al. Body mass index: a marker for significant colorectal neoplasia in a screening population. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41(3):285–90. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000247988.96838.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stein B, Anderson JC, Rajapakse R, Alpern Z, Messina CR, Walker G. Body Mass Index as a Predictor of Colorectal Neoplasia in an Average Risk Population. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 2010;(In Press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. JAMA. 2006;295(13):1549–55. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.James AS, Leone L, Katz ML, McNeill LH, Campbell MK. Multiple health behaviors among overweight, class I obese, and class II obese persons. Ethn Dis. 2008;18(2):157–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen SS, Signorello LB, Gammon MD, Blot WJ. Obesity and recent mammography use among black and white women in the Southern Community Cohort Study (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 2007;18(7):765–73. doi: 10.1007/s10552-007-9019-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fontaine KR, Heo M, Allison DB. Body weight and cancer screening among women. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2001;10(5):463–70. doi: 10.1089/152460901300233939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maruthur NM, Bolen S, Brancati FL, Clark JM. Obesity and mammography: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(5):665–77. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0939-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olson CL, Schumaker HD, Yawn BP. Overweight women delay medical care. Arch Fam Med. 1994;3(10):888–92. doi: 10.1001/archfami.3.10.888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kinney AY, Bloor LE, Martin C, Sandler RS. Social ties and colorectal cancer screening among Blacks and Whites in North Carolina. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(1):182–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen LA, Santos S, Jandorf L, et al. A program to enhance completion of screening colonoscopy among urban minorities. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(4):443–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khaodhiar L, McCowen KC, Blackburn GL. Obesity and its comorbid conditions. Clin Cornerstone. 1999;2(3):17–31. doi: 10.1016/S1098-3597(99)90002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Young LM, Powell B. The effects of obesity on the clinical judgments of mental health professionals. J Health Soc Behav. 1985;26(3):233–46. doi: 10.2307/2136755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]