Abstract

The availability of alternative reinforcers reduces drug taking. Escalating alternative reinforcer values have been used to initiate and maintain abstinence from drug use. A reset in reinforcer value has been added to the schedule of alternative reinforcer presentation to discourage relapse. The purpose of this preliminary study was to test the influence of escalating and escalating and resetting alternative reinforcer value on cigarette choice in the human laboratory. Fourteen daily cigarette smokers completed this experiment, which required one practice and three experimental sessions. During each experimental session, subjects made six choices between smoking a cigarette and receiving money, available under Constant, Escalating or Escalating and Resetting conditions. The total number of cigarettes chosen and puffs taken, but not the maximum consecutive number of cigarettes choices, was decreased in the Escalating condition relative to the Constant condition. The maximum number of consecutive cigarettes chosen was decreased in the Escalating and Resetting condition relative to the Constant condition. The proportion of money earned was increased in the Escalating condition relative to the Constant and Escalating and Resetting conditions. These initial findings indicate that whereas an escalating alternative reinforcer schedule reduces cigarette smoking overall, an escalating and resetting alternative reinforcer schedule may reduce repeated cigarette smoking (i.e., relapse).

Keywords: Alternative Reinforcer, Cigarette Smoking, Choice, Humans

1. INTRODUCTION

The availability of non-drug alternative reinforcers reduces drug taking. Results from non-human animal studies have demonstrated that providing alternative reinforcers (e.g., food or sweetened fluid) decreases self-administration of a number of drugs, including cocaine, heroin, phencyclidine and nicotine (Anderson et al., 2002; Carroll, 1985; Lenoir and Ahmed, 2008; LeSage, 2009; Nader and Woolverton, 1991; Negus, 2003). For example, in one study, rats were trained to self-administer nicotine (LeSage, 2009). Sucrose pellets were then made available contingent upon the rats abstaining from nicotine. Sucrose pellet availability reduced nicotine self-administration by as much as 73% relative to baseline levels.

This effect has also been demonstrated in a number of human laboratory studies with similar drugs (Bisaga et al., 2007; Comer et al., 1998; Hart et al., 2000; Higgins et al., 1994; Stoops et al., 2010). In one study, cigarette smokers were offered the opportunity to work to receive cigarette puffs or an alternative reinforcer ranging from US$0.50 to $3.00 (Bisaga et al., 2007). Increasing alternative reinforcer values decreased choice of cigarettes, with the highest values resulting in approximately 50% reductions in cigarette choice relative to the lowest value.

Not surprisingly, the use of non-drug alternative reinforcers has been adapted into clinical settings to promote abstinence from drug use. A number of studies have demonstrated that providing alternative reinforcers (e.g., cash or vouchers) contingent upon biologically verified abstinence reduces marijuana, cocaine, methamphetamine and cigarette use (e.g., Budney et al., 1991; Higgins et al., 1991; Roll et al., 2006; Stoops et al., 2009). Clinical studies have provided the non-drug alternatives contingent upon abstinence in a number of ways, including a fixed value alternative reinforcer, an escalating value of alternative reinforcer or an escalating value of alternative reinforcer with a reset in value when patients lapse or relapse to drug use (Roll and Higgins, 2000; Roll et al., 1996; Roll and Shoptaw, 2006). The results of those studies suggest that providing alternative reinforcers that escalate as patients continue to demonstrate abstinence but that reset in value upon a lapse or relapse (i.e., escalating and resetting schedule) is most effective in maintaining drug abstinence. While results of a previous laboratory-based study demonstrated that an escalating and resetting schedule of alternative reinforcer presentation reduced cigarette smoking in a 3 hour session (Dallery and Raiff, 2007), the purpose of this preliminary experiment was to compare the influence of constant (i.e., fixed), escalating or escalating and resetting values of alternative reinforcers on cigarette smoking.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Subjects

Fourteen adult smokers (nine male, five female) completed this within-subject study. Subjects ranged in age from 20 to 32 years (mean = 25). Subjects reported smoking 10 to 20 cigarettes per day (mean = 17). Other than daily cigarette smoking, subjects were in good health. An additional six subjects completed the practice session but withdrew before completing any experimental sessions. Data from those subjects are not included in the analyses.

2.2 General Procedures

The Institutional Review Board of the University of Kentucky Medical Center approved the conduct of this study and all subjects gave their sober, written informed consent prior to enrolling. Subjects enrolled as outpatients at the Laboratory of Human Behavioral Pharmacology at the University of Kentucky Medical Center for four sessions (one practice and three experimental). During the practice session, subjects completed the same tasks they would complete in experimental sessions with the exception that during the choice task they made choices between no cigarettes and no money (i.e., these options were presented on the computer screen but subjects did not earn anything upon completing the response).

On experimental session days, subjects arrived at the laboratory at approximately 0800. Baseline tobacco abstinence symptoms (a modified version of the Questionnaire of Smoking Urges-Brief [QSU-Brief; Cox et al., 2001] and the Minnesota Nicotine Withdrawal Scale [MNWS; Hughes and Hatsukami, 1998]), physiological and sobriety measures were completed between 0800 and 0900. Subjects had to provide a urine negative for all drugs other than THC and an expired breath sample negative for alcohol and with a carbon monoxide (CO) level of less than 5 ppm to participate in each experimental session. Subjects were allowed to participate if they provided a urine sample positive for THC only if they passed these baseline sobriety measures, indicating that they were not acutely intoxicated by cannabis. Video recording of the session began at 0900, when subjects made their first choice between a cigarette of their preferred brand and money, the value of which varied based on the type of session (see Experimental Session Types below). Prior to making each choice, CO, heart rate and blood pressure were measured and the QSU-Brief was completed. Choice options were presented to subjects on a computer screen and after selecting their choice, subjects had to complete 200 responses (FR 200) on a computer mouse to earn their selection. The selected option, either a cigarette or tokens labeled US$0.25 up to the chosen amount, was then provided to them. Subjects made five more choices at 45-min intervals for the next 3.75 h for a total of six choices. After making and receiving their final choice at 1245, subjects completed the MNWS and were paid for their participation, including whatever money they chose in that session, and were released. Upon release, subjects were asked to abstain from smoking long enough to meet the CO criteria to participate in the next session, but no other smoking restrictions were imposed.

2.3 Experimental Session Types

Subjects completed a total of three experimental sessions. Sessions were conducted on an identical timeline, as described in the General Procedures, and differed only in the amount of money available at each cigarette choice. There were three session types, presented in random order: 1) Constant Money Value Condition, 2) Escalating Money Value Condition and 3) Escalating and Resetting Money Value Condition. In the Constant Money Value Condition, choices were always between a cigarette and US$0.25. In the Escalating Money Value Condition, choices were between a cigarette and escalating values of money (US$0.25, 0.50, 0.75, 1.00, 1.25 and 1.50). In the Escalating and Resetting Money Value Condition, choices were also between a cigarette and escalating values of money (US$0.25, 0.50, 0.75, 1.00, 1.25 and 1.50). For this condition, however, if a subject chose a cigarette at any time, the monetary value of the next choice was reset to US$0.25. Thus, if a subject chose all cigarettes in the Escalating and Resetting condition, choices would have always been between a cigarette and US$0.25, as was the case for the Constant Condition. If a subject chose only money, choices would have been between a cigarette and US$0.25, 0.50, 0.75, 1.00, 1.25 and 1.50, as was the case for the Escalating Condition. The money values were selected based on previously published research (Bisaga et al., 2007; Stoops et al., 2011; Tidey et al., 2000). Subjects were provided with detailed instructions about the money values available at the beginning of each session. The instructions also specified that subjects could make different choices throughout the session (i.e., choices were independent of each other).

2.4 Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measures were total number of cigarette choices and maximum number of consecutive cigarette choices. Secondary outcome measures included proportion of money earned, number of consecutive money choices, total number of puffs (recorded from the video of session; see Rush et al., 2005), peak (i.e., the maximum value observed during the cigarette choice period) CO and cardiovascular effects, trough (i.e., the minimum value observed during the cigarette choice period) QSU-Brief scores and post-session MNWS score. Baseline scores on the QSU-Brief and MNWS were also analyzed to determine whether subjects differed in tobacco abstinence symptoms at the outset of session.

2.5 Data Analysis

Data were analyzed statistically for all measures using a one-factor Repeated Measures Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with Experimental Session Type (Constant, Escalating, Escalating and Resetting) as the factor (Prism 5 for Mac OSX, GraphPad Software, LaJolla, CA). Effects were considered significant for p ≤ 0.05. If a statistically significant effect was observed, Tukey's post hoc tests were used to compare all means.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Primary Outcome Measures

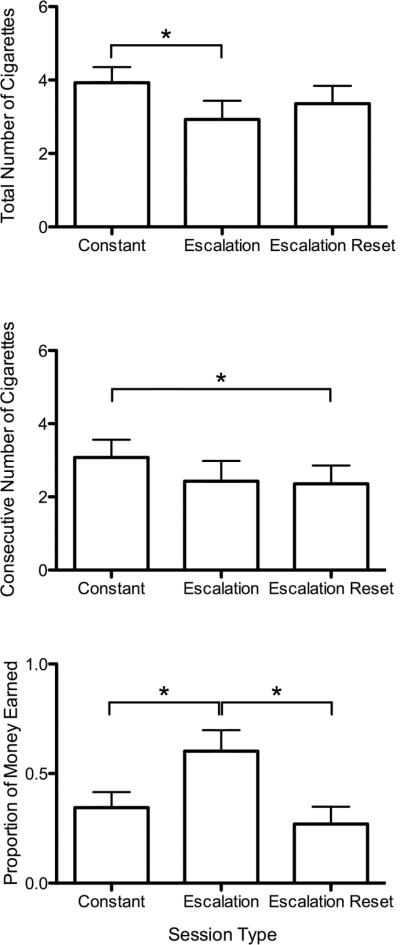

The total number of cigarette choices was significantly decreased in the Escalating condition relative to the Constant condition (F2,26 = 4.37; Figure 1). The maximum number of consecutive cigarette choices was significantly decreased in the Escalating and Resetting condition relative to the Constant condition (F2,26 = 3.76; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Effects of alternative reinforcer schedule for total number of cigarettes chosen (top panel), maximum number of consecutive cigarette choices (middle panel) and proportion of money earned (bottom panel). X-axis: Experimental session type. Brackets and asterisks indicate conditions that are significantly different from one another.

3.2 Secondary Outcome Measures

The proportion of money earned was significantly increased in the Escalating condition relative to the Constant and Escalating and Resetting conditions (F2,26 = 10.89; Figure 1). Although not analyzed statistically due to differing money amounts being available across sessions, the average total money earned under the Constant, Escalating and Escalating and Resetting conditions was US$0.52, US$3.16 and US$1.41, respectively. The total number of puffs was significantly decreased in the Escalating condition relative to the Constant condition (F2,26 = 4.85; data not shown). No other significant effects were observed on any of the secondary outcome measures, nor did subjects differ in baseline tobacco abstinence symptoms at the outset of any experimental session type (data not shown).

4. DISCUSSION

In this preliminary study, providing escalating values of alternative reinforcers decreased both total cigarette choices and total puffs relative to constant values of alternative reinforcers. Providing escalating values that reset to a low value when subjects chose a cigarette decreased consecutive cigarette choices relative to constant values. The proportion of money earned by subjects was significantly greater in the escalation condition relative to the other conditions. Importantly, there was no difference in baseline tobacco abstinence symptoms as measured by the QSU or MNWS as a function of condition, indicating that the results are not due to subjects experiencing different nicotine or tobacco deprivation effects across sessions.

Our findings are concordant with previous preclinical and clinical work suggesting that the availability of non-drug alternative reinforcers of sufficient magnitude reduces overall drug taking (e.g., Bisaga et al., 2007; Dallery and Raiff, 2007; Higgins et al., 1991; Nader and Woolverton, 1991). The present results extend those of previous human laboratory research by demonstrating that a reset contingency reduces consecutive cigarette choices. Longer-term treatment studies have demonstrated that an escalating and resetting schedule of alternative reinforcer availability is most efficacious at reducing drug use and discouraging relapse (Roll and Higgins, 2000; Roll et al., 1996; Roll and Shoptaw, 2006). It is possible that the reduction in consecutive cigarette choices observed under the escalating and resetting condition here mirrors how similar schedules work clinically (e.g., reducing repeated drug taking).

It is unclear why overall cigarette choice was not significantly decreased in the escalating and resetting condition, but this finding could be related to the reduced proportion of money earned in this condition relative to the escalating condition. The absolute money value available was the same in the escalating and escalating and resetting conditions, but subjects could choose to stop smoking close to the end of session under the escalating schedule (i.e., the last two choices) and earn more than 50% of the total available. This was not the case in the escalating and resetting condition, so subjects would have to make consecutive choices for money to increase the alternative reinforcer value available at the next choice opportunity. If subjects did not make consecutive money choices early in session, it is possible that the perceived low value of subsequent alternative reinforcers resulted in greater overall cigarette choices. These results suggest that the type of alternative reinforcer schedule in place (i.e., escalating or escalating and resetting) results in differential patterns of cigarette choice, at least under these laboratory conditions.

There are a number of limitations that should be noted. First, the total number of cigarette choices decreased by only one in the escalating condition relative to the constant condition. An equally small reduction was observed in the escalating and resetting condition on consecutive cigarette choices. Although cigarette choice was reduced by approximately 25% relative to the constant condition, the clinical significance of such reductions is not clear, particularly because expired CO levels were not different across session types. Perhaps the use of an alternative reinforcer with a higher initial value, allowing a different number of cigarette choices or having different inter-choice intervals in sessions would have resulted in a greater reduction. Higher alternative reinforcer values would have increased the magnitude of the reset in the Escalation and Resetting condition, which would likely have impacted consecutive cigarette choices to a greater degree. Second, non-treatment seeking smokers served as the study population; these results may not generalize to a treatment-seeking group. Third, there may be individual differences that contributed to the cigarette choice patterns, but such analysis of individual differences was beyond the scope of this preliminary study.

5. CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, escalating alternative reinforcer values decreased cigarette choice in a cigarette-versus-alternative reinforcer choice task. A reset contingency added to the alternative reinforcer escalation schedule reduced consecutive but not overall cigarette choice. These results are generally consistent with preclinical and clinical findings and support the utility of alternative reinforcers for reducing drug taking. Future work should refine these methods by examining the effects of higher value alternative reinforcers over a different number of choices and inter-choice intervals in treatment-seeking smokers. Future work should also seek to identify individual differences that might impact cigarette choice under this arrangement.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by National Cancer Institute grant R21 CA 124881 to WWS. Startup funds from the University of Kentucky Department of Behavioral Science to WWS also supported this project. The funding sources had no role in study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report or decision to submit this paper for publication. All authors declare no conflicts of interest relevant to this project. We thank Paul E.A. Glaser, M.D., Ph.D. and Frances P. Wagner, R.N., for their medical assistance and Amanda Bucher, Sean Durkin, Michelle Gray, Bryan Hall, Richard Heifner, Kathryn Hays, Erika Pike, Matthew Stanley and Sarah Veenema for their technical assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Anderson KG, Velkey AJ, Woolverton WL. The generalized matching law as a predictor of choice between cocaine and food in rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology (Berlin) 2002;163:319–326. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisaga A, Padilla M, Garawi F, Sullivan MA, Haney M. Effects of alternative reinforcer and craving on the choice to smoke cigarettes in the laboratory. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental. 2007;22:41–47. doi: 10.1002/hup.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ, Higgins ST, Delaney DD, Kent L, Bickel WK. Contingent reinforcement of abstinence with individuals abusing cocaine and marijuana. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1991;24:657–665. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1991.24-657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll ME. Concurrent phencyclidine and saccharin access: Presentation of an alternative reinforcer reduces drug intake. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1985;43:131–144. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1985.43-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer SD, Collins ED, Wilson ST, Donovan MR, Foltin RW, Fischman MW. Effects of an alternative reinforcer on intravenous heroin self-administration by humans. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1998;345:13–26. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01572-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox LS, Tiffany ST, Christen AG. Evaluation of the brief questionnaire of smoking urges (QSU-brief) in laboratory and clinical settings. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2001;3:7–16. doi: 10.1080/14622200020032051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallery J, Raiff BR. Delay discounting predicts cigarette smoking in a laboratory model of abstinence reinforcement. Psychopharmacology (Berlin) 2007;190:485–496. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0627-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart CL, Haney M, Foltin RW, Fischman MW. Alternative reinforcers differentially modify cocaine self-administration by humans. Behavioral Pharmacology. 2000;11:87–91. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200002000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Bickel WK, Hughes JR. Influence of an alternative reinforcer on human cocaine self-administration. Life Science. 1994;55:179–187. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(94)00878-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Delaney DD, Budney AJ, Bickel WK, Hughes JR, Foerg F, Fenwick JW. A behavioral approach to achieving initial cocaine abstinence. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1991;148:1218–1224. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.9.1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes J, Hatsukami DK. Errors in using tobacco withdrawal scale. Tobacco Control. 1998;7:92–93. doi: 10.1136/tc.7.1.92a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenoir M, Ahmed SH. Supply of a nondrug substitute reduces escalated heroin consumption. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:2272–2282. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesage MG. Toward a nonhuman model of contingency management: effects of reinforcing abstinence from nicotine self-administration in rats with an alternative nondrug reinforcer. Psychopharmacology (Berlin) 2009;203:13–22. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1362-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nader MA, Woolverton WL. Effects of increasing the magnitude of an alternative reinforcer on drug choice in a discrete-trials choice procedure. Psychopharmacology (Berlin) 1991;105:169–174. doi: 10.1007/BF02244304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negus SS. Rapid assessment of choice between cocaine and food in rhesus monkeys: Effects of environmental manipulations and treatment with d-amphetamine and flupenthixol. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:919–931. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roll JM, Higgins ST. A within-subject comparison of three different schedules of reinforcement of drug abstinence using cigarette smoking as an exemplar. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000;58:103–109. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00073-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roll JM, Higgins ST, Badger GJ. An experimental comparison of three different schedules of reinforcement of drug abstinence using cigarette smoking as an exemplar. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1996;29:495–505. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1996.29-495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roll JM, Petry NM, Stitzer ML, Brecht ML, Peirce JM, McCann MJ, Blaine J, MacDonald M, DiMaria J, Lucero L, Kellogg S. Contingency management for the treatment of methamphetamine use disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:1993–1999. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.11.1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roll JM, Shoptaw S. Contingency management: Schedule effects. Psychiatry Research. 2006;144:91–93. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush CR, Higgins ST, Vansickel AR, Stoops WW, Lile JA, Glaser PE. Methylphenidate increases cigarette smoking. Psychopharmacology (Berlin) 2005;181:781–789. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0021-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoops WW, Dallery J, Fields NM, Nuzzo PA, Schoenberg NE, Martin CA, Casey B, Wong CJ. An internet-based abstinence reinforcement smoking cessation intervention in rural smokers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;105:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoops WW, Lile JA, Rush CR. Monetary alternative reinforcers more effectively decrease intranasal cocaine choice than food alternative reinforcers. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2010;95:187–191. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoops WW, Poole MM, Vansickel AR, Hays KA, Glaser PE, Rush CR. Methylphenidate increases choice of cigarettes over money. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2011;13:29–33. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tidey JW, O'Neill SC, Higgins ST. d-Amphetamine increases choice of cigarette smoking over monetary reinforcement. Psychopharmacology (Berlin) 2000;153:85–92. doi: 10.1007/s002130000600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]