Abstract

The essential role of human dual oxidase 2 (hDUOX2) in thyroid hormone biosynthesis defines this member of the NOX/DUOX family, whose absence due to mutation has been directly related to disease, specifically hypothyroidism. Both human DUOX isoforms, hDUOX1 and hDUOX2, are expressed in thyroid tissue; however, hDUOX1 cannot compensate for inactivation of hDUOX2, suggesting that each enzyme is differentially regulated and/or functions in a unique manner. In efforts to uncover relevant structural and functional differences we have expressed and purified the peroxidase domain of hDUOX21–599 for direct comparison with the previously studied hDUOX11–593. As was shown for hDUOX1, the truncated hDUOX2 domain purifies without a bound heme cofactor and displays no peroxidase activity. However, hDUOX21–599 displays greater stability than hDUOX11–593. Surprisingly, upon titration with heme, both isoforms bind heme with a low micromolar affinity, demonstrating that they retain a heme binding site. A conformational difference in the full-length protein and/or a protein-protein interaction may be required to increase the heme binding affinity.

INTRODUCTION

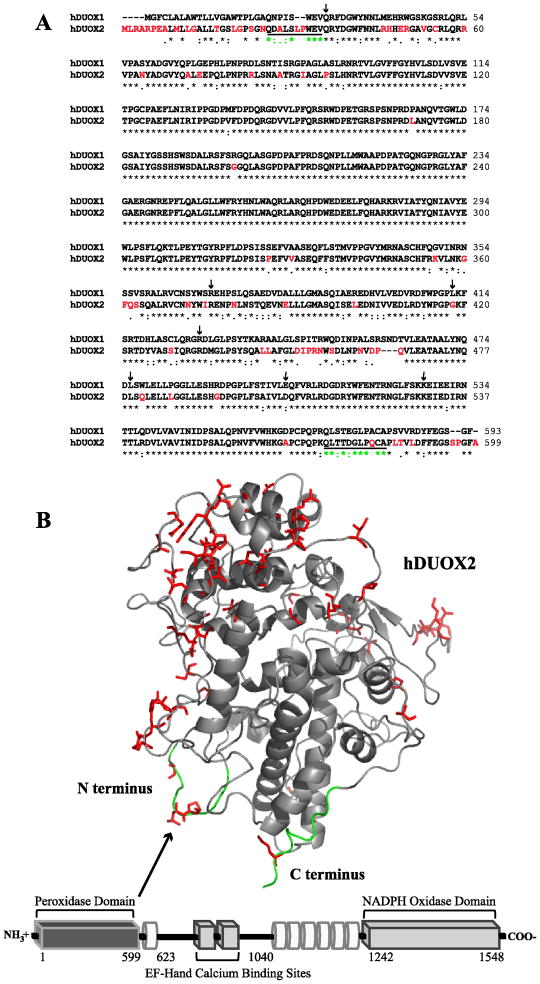

Since its identification as a novel class of proteins capable of producing reactive oxygen species (ROS) in non-phagocytic cells, the human NADPH oxidase (NOX/dual oxidase (DUOX)) family has expanded to include seven enzymes. The two human dual oxidase isoforms, hDUOX1 and hDUOX2, were first discovered in the thyroid gland, where they are strongly expressed [1, 2]. The genes for hDUOX1 and 2 are located on chromosome 15, arranged head to head and separated by a 16 kb region [3]. The human duox2 gene spans 21.5 kb, contains 34 exons, and results in a 1548 amino acid protein. Structurally, both isoforms share a conserved motif, consisting of a defining N-terminal peroxidase-like domain (~43% homologous to thyroid peroxidase (TPO)), 2 calcium binding regions, 6 transmembrane domains and an NADPH oxidase domain (Figure 1). Consistent with this motif, calcium has been shown to regulate the production of H2O2 by DUOX2 [4]. The glycosylation of both hDUOX proteins is extensive, with at least five putative sites for N-glycosylation found in the peroxidase domain of each isoform (Table 1). This modification is critical to achieving active cell surface expression, as only fully glycosylated DUOX proteins are transported to the plasma membrane [5]. Overall, the two full-length isoforms share 83% sequence similarity; the N-terminal peroxidase regions alone exhibit 80% amino acid identity (Figure 1) [2].

Figure 1.

Sequence and structural features of hDUOX2. (A) Sequence alignment of the peroxidase domains of hDUOX1 and 2 (hDUOX11–593 and hDUOX21–599). Amino acids which differ significantly (1dot or no symbol designation) between the two proteins have been highlighted in red, corresponding with the model structure of hDUOX21–599. Residues defined as the N and C termini of the hDUOX2 model structure are underlined. Amino acids subject to disease related mutations in hDUOX2 are highlighted by arrows (Q36H, R376W, G418fsX482, R434X, L479SfsX2, D506N, K530X). (B) Bottom: Schematic view of the domain structure of hDUOX2. Each DUOX protein contains an N-terminal extracellular “peroxidase” domain (dark gray rectangle), putative TM domains (white tubes) which bind two heme molecules, and cytosolic EF-hand and NADPH oxidase domains (light gray rectangle). hDUOX2 was truncated to generate a soluble expression construct limited to the peroxidase domain, as highlighted by the model structure (Top). Residues of greatest amino acid difference between hDUOX isoforms are highlighted in red and shown as sticks; the N and C termini of the hDUOX21–599 model structure are highlighted in green.

Table 1. DUOX Peroxidase Domain Characteristics.

For isolated DUOX proteins, pI values were estimated using the ExPASy Proteomics Server (ProtParam), and sites of glycosylation were predicted by NetNGlyc 1.0 Server. CeDUOX11–589 was purified previously [21, 40]. Soret maxima absorptions are reported for room temperature measurements at pH 7.0; ND, not detectable upon isolation. Soret values in parentheses denote maxima achieved from titration with heme co-factor. Proteins in bold face are those under investigation in this manuscript.

| Protein | Size (kDa) | # of Tryptophans | pI value | Predicted Glycosylation Sites | Soret Maxima |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hDUOX11–593 | 67.8 | 19 | 6.0 | N94, N342, N354, N461, N534 | ND (415 nm) |

| hDUOX21–599 | 68.3 | 15 | 5.7 | N100, N348, N382, N455, N537 | ND (414 nm) |

| CeDUOX11–589 | 68.3 | 11 | 5.9 | N66, N305, N567, N586 | 408 nm |

For years, recombinant expression of the DUOX proteins remained unobtainable, suggesting that crucial, unidentified factors and/or proteins necessary for proper maturation remained unknown. Recently, several DUOX interacting proteins have been identified that aid in protein maturation, regulate activity, and discriminate between isoforms. Recombinant expression was made possible by the discovery of two maturation factors (DUOXA1 and DUOXA2) required for exit of the DUOX proteins from the ER and for the formation of complexes at the cell membrane. Each DUOX isoform has a specific, correspondingly numbered maturation factor and mismatched interactions result in diminished ROS production [6]. A novel inhibitory protein, NOXA1, was discovered through its homology to a known NOX2 interacting protein, p67phox. Its stable, direct interaction with the C-terminus of an inactive, “resting state” DUOX1 protein was shown by immunoprecipitation experiments. Dissociation of the NOXA1/DUOX1 complex, which activates H2O2 generation by DUOX, was found to be calcium-dependent [7]. EFP-1, a thioredoxin-related protein, was also found to be a DUOX interaction partner by a yeast two hybrid screen. EFP-1 was shown to interact with the EF-hand calcium binding domains of hDUOXs in an unexpected, calcium independent manner [8]. Most recently, exploration of differential regulation has established that the promoter region for hDUOX2 differs prominently from that of hDUOX1 [3]. Furthermore, studies of the phosphorylation signaling mediated by protein kinase A (PKA) and protein kinase C (PKC) have defined separate activation mechanisms for the two DUOX isoforms in human thyroid cell culture. hDUOX1 ROS production is modulated by forskolin and calcium, whereas hDUOX2 is stimulated by PMA [9]. This difference may be related to the differential activities of the two DUOX isoforms in thyroid hormone biosynthesis and the inability of hDUOX1 to rescue a hypothyroid phenotype resulting from mutation of hDUOX2.

In the thyroid gland, the DUOX proteins produce the H2O2 utilized by TPO for hormone biosynthesis. Immunostaining shows that DUOX proteins co-localize in the apical poles of thyroid cells with mammalian TPO. Based on mRNA levels, hDUOX2 is 2 to 5 times more abundant in the thyroid than hDUOX1 [3], but the protein expression levels of hDUOX2 are only ~1.5 times greater than those of hDUOX1. Normal thyroid tissue, as well as adenoma and carcinoma forms, express the DUOX genes in parallel, implying that their expression is controlled by similar mechanisms [10]. An essential role of ROS production by hDUOX2 in thyroid hormone biosynthesis was clearly established by the identification of patients suffering from hypothyroidism due to mutations in hDUOX2. A patient with severe hypothyroidism was found to be homozygous (biallelic) for a premature stop codon in duox2 (C1300T) resulting in a protein lacking all functional domains for H2O2 generation. Several monoallelic mutations on the duox2 gene, including C2056T, were found to result in a partial iodide-organification defect phenotype, also most likely due to expression of a truncated form of hDUOX2 (amino acids 1–685) [11, 12]. The importance of the peroxidase region has been highlighted through identification of several mutations within it known to cause hypothyroidism, including non-sense mutations at R434 and K530 (stop codon insertions), G418 (frame shift resulting in a stop codon) and L479 (deletion-insertion leading to a frame shift/stop codon) as well as missense mutations (Q36H, R376W, and D506N; Figure 1A) [11, 13, 14]. Interestingly, hDUOX2-deficient hypothyroidism was the first known disease clearly linked to the absence of a specific NOX/DUOX enzyme. In contrast, the role of hDUOX1 remains elusive and a key question continues to be its inability to compensate for defects in hDUOX2.

In addition to its expression in the thyroid gland, hDUOX2 is prominently found in the digestive tract, salivary gland and rectum [15–17]. hDUOX2 expression levels were also noted by EST and SAGE libraries to be significant in the stomach, pancreas and prostate [18]. Several studies report tissue-specific co-expression of DUOX with one or more of the mammalian peroxidases [15, 18, 19]. Because lactoperoxidase (LPO) is co-expressed in the salivary gland and rectum, hDUOX2 may provide the H2O2 for LPO catalyzed reactions at these mucosal surfaces [15]. This is consistent with the possibility that the N-terminal peroxidase domain is a site for mammalian peroxidase binding rather than having a catalytic function. In a contrasting study, cytokine interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) was found to induce heme peroxidase activity, specifically H2O2 generation and tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) turnover, that paralleled hDUOX2 expression in human airway epithelial cells [20]. This activity, which was inhibited by the heme peroxidase inhibitor sodium azide, provides evidence that hDUOX2, despite the absence of some of the residues that normally interact with the heme, may nevertheless bind this co-factor and possess its own peroxidase activity. Here we continue our investigation of the N-terminal peroxidase domain of the DUOX proteins, with a focus on hDUOX2. Expression of the hDUOX2 “peroxidase” domain shows that it is generally similar to the previously studied hDUOX1 isoform, including the fact that heme does not co-purify with the protein [21]. Although circular dichroism (CD) reveals an overall similar α-helical structure for the two isoforms, differences in the stabilities of the two proteins are demonstrated by Trp fluorescence and detailed CD studies. Most importantly, spectroscopic monitoring of the titration of hDUOX1 and hDUOX2 with heme reveals that both proteins can specifically bind heme, albeit with a low micromolar affinity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials, facilities and general instrumentation

Sf9 cells (Invitrogen) were grown in ExCell 420™ medium (SAFC Biosciences) supplemented with glutamine (2.7 g/L). High Five™ (H5) cells were grown in Express Five™ medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with glutamine (2.7 g/L) and 10% fetal bovine serum. Both cell lines were kept in suspension at 27 ºC (100 rpm) and maintained at densities between 0.5 × 106 and 2 × 106 cells/mL. H2O2 (30% w/w) and ABTS (2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoleline-6-sulfonic acid)) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. T4 DNA ligase and restriction endonucleases were obtained from New England Biolabs. DNA sequencing was performed by Elim Biopharmaceuticals; the entire gene insert was completely sequenced for each plasmid construct. For protein identification, the mass spectra from trypsin digestion were obtained on a QSTAR Elite mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems/MDS Sciex; see Supplemental Data, Figure S1). Spectrophotometric measurements were performed on a Cary 50 Bio UV-vis spectrophotometer (Varian). For experiments utilizing H2O2, concentrations were determined spectrophotometrically at 240 nm by using the molar extinction coefficient ε = 43.6 M−1 cm−1 [22]. All experiments were performed at room temperature unless otherwise stated.

Sequence alignment and structure prediction

The hDUOX2 protein was truncated using the TMHMM transmembrane helix algorithm (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM/) to identify the primary sequence that composes the N-terminal peroxidase domain (residues 1–599); the peroxidase domain of hDUOX1 was previously identified as residues 1–593 [21, 23]. Both truncated hDUOX sequences were submitted for alignment generation to Clustal W (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/clustalw2/index.html) [24]. A structural model of hDUOX21–599 was built by sequence submission to the SWISS-MODEL program server (http://www.swissmodel.expasy.org/) for automatic modeling; the model, with bovine LPO (PDB: 3BXI) as the template, encompasses residues 26–583 and was visualized with the software Pymol [25].

Plasmid constructs

Expression and purification of the gene encoding the peroxidase domain of hDUOX2 was modeled on our previous successful work with hDUOX11–593. Briefly, hduox2 (1–599) was synthesized by GeneArt Inc., introducing restriction sites BamHI and EcoRI at the 5′ and 3′ ends of the gene respectively; a C-terminal 6His tag was also inserted to aid purification. The duox21–599 gene was subcloned from the GeneArt vector and ligated into pAcGP67-b baculovirus expression vector (named pJLM025) providing a C-terminal 6His tagged construct for protein expression. The insert was sequenced in its entirety prior to protein expression. The peroxidase domain construct for hDUOX1 (residues 1–593) was previously described [21].

Expression and purification of hDUOX peroxidase domain constructs

hDUOX11–593 and hDUOX21–599 were expressed and purified according to the previously reported procedure [21]. Each purified protein was stored at −20 °C and all stock concentrations were determined in triplicate by Bradford assay [26].

Evaluation of hDUOX21–599 secondary structure

Tryptophan (Trp) fluorescence emission spectra for hDUOX11–593 and hDUOX21–599 were collected at a concentration of 750 nM using a Fluorolog 3 Spectrofluorometer (Horiba Jobin Yvon), with excitation at 292 nm and emission monitored between 315 and 450 nm using 2.5 nm excitation and emission slits. Citrate phosphate buffer was used to collect spectra within a pH range of 4.0 to 9.0. Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy of hDUOX21–599 was done in comparison to hDUOX11–593; far-UV CD spectra were collected on a JASCO J-715 spectropolarimeter using a cuvette path length of 1.0 mm and spectral collection in the range of 195–250 nm at 20 °C. All CD experiments were conducted in 10 mM phosphate buffer, at pH 4.0, 7.0 and pH 9.0, at a protein concentration of 4 μM. Raw ellipticity data was converted to mean residue ellipticity before plotting.

ABTS activity assay comparison of hDUOX1 and hDUOX2 peroxidase domains

Peroxidase activity was measured using 500 nM ABTS incubated with 500 nM hDUOX11–593 or hDUOX21–599 in 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, or citrate-phosphate buffer, pH 4.0 (each buffer was treated with chelex-100 resin). The reactions were initiated by the addition of H2O2 (50 μM). Each reaction was monitored by recording the absorbance intensity at 414 nm as a function of time.

Superoxide dismutase activity assay(s)

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity was measured as a percentage inhibition of the rate of the enzyme (SOD, hDUOX11–593 or hDUOX21–599) with the substrate WST-1 (a water soluble tetrazolium dye) and xanthine oxidase using an SOD Assay Kit (Fluka, 19160) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Each endpoint assay was monitored by absorbance at 450 nm (the absorbance wavelength for the colored product of the WST-1 reaction with superoxide) after 20 min of reaction time at 37 °C. All enzyme stocks were made in 50 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.0, 5% glycerol or 50 mM citric acid buffer, pH 4.0, 5% glycerol; each assay was performed in triplicate.

Heme titration of hDUOX11–593 and hDUOX21–599

A 250 μM solution of monomeric heme was made by dissolving 1.63 mg hemin in 200 μL 0.1 N NaOH, then diluting this solution out to 10 mL with 100 mM potassium phosphate, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% TritonX-100 and 0.1% Cholate, pH 7.4. Each enzyme was titrated in a dual cuvette system to cancel out free heme absorbance at a concentration of 4 μM in 100 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, at room temperature. Difference absorbance spectra were scanned from 300 to 600 nm upon heme addition after 2 minutes incubation time over concentrations of 500 nM to 8 μM. Titration curves were derived by plotting absorbance values at 415nm (hDUOX21–599) or 414 nm (hDUOX11–593) versus heme concentration. Each heme binding curve was fit to the Michaelis Menten equation (non-linear regression analysis) to determine a dissociation constant or Kd, assuming 1:1 binding. Curve fitting was achieved utilizing Kaleidagraph software (Synergy).

RESULTS

Modeling and solubilization of the hDUOX2 peroxidase domain (hDUOX21–599)

Sequence based comparisons indicate that both hDUOX1 and hDUOX2 have a characteristic N-terminal extracellular domain homologous to the mammalian peroxidases. Our earlier characterization of the hDUOX1 “peroxidase” domain, encompassing the first 593 amino acids, showed that the protein purifies without a heme bound to the protein and with no peroxidase or superoxide dismutase activity [21]. This result is consistent with the fact that by sequence alignments both isoforms lack several of the residues that in mammalian peroxidases are involved in heme binding and catalysis. However, deficiencies in hDUOX2 physiological activity and/or localization are directly associated with mutations in its N-terminal domain [11–14, 27–30] (Figure 1A). Several of these mutations are not rescued by expression of hDUOX1, resulting in hypothyroidism and suggesting that the peroxidase domain of hDUOX2 differs significantly from that of hDUOX1 in activity, stability, or heme binding ability. To explore these differences, we have expressed the soluble N-terminal domain of hDUOX2.

The TMHMM transmembrane helix algorithm predicted the size of the outer cellular region of the two hDUOX isoforms to be approximately the same (Table 1), while sequence alignments indicated ~80% identity between the two domains (Figure 1A). A model was generated of the hDUOX2 truncated protein based on structural similarity to the mammalian peroxidase LPO in order to identify the primary regions of hDUOX1 and hDUOX2 that differ in amino acid sequence. The greatest region of amino acid variation, as shown by highlighted residues on the exposed face of the extracellular domain (Figure 1B), suggest that the amino acid differences may facilitate specific protein-protein interactions. This hypothesis is consistent with the specificity for separate maturation factors of the two isoforms and possibly with ROS delivery to different mammalian peroxidases [6, 15, 19, 30].

The N-terminal peroxidase domain of hDUOX2 (hDUOX21–599) was stably overexpressed in a baculovirus system as a C-terminal 6His tagged construct utilizing the same strategy as was employed earlier for hDUOX11–593. LCMS-MS confirmed the identity of the purified hDUOX2 N-terminal domain (Figure S1). Truncated hDUOX21–599, like hDUOX11–593, eluted from the affinity column with ~100 mM imidazole, suggesting similar fold/accessibility of their 6His tags [21]. The yield of hDUOX21–599, again like that of hDUOX11–593, was reproducible at a level of approximately 0.7 mg/L. As found earlier for hDUOX11–593, the UV-vis spectrum (Figure S2) demonstrated that heme was not associated with the purified hDUOX21–599 domain.

Structural stability of the hDUOX proteins

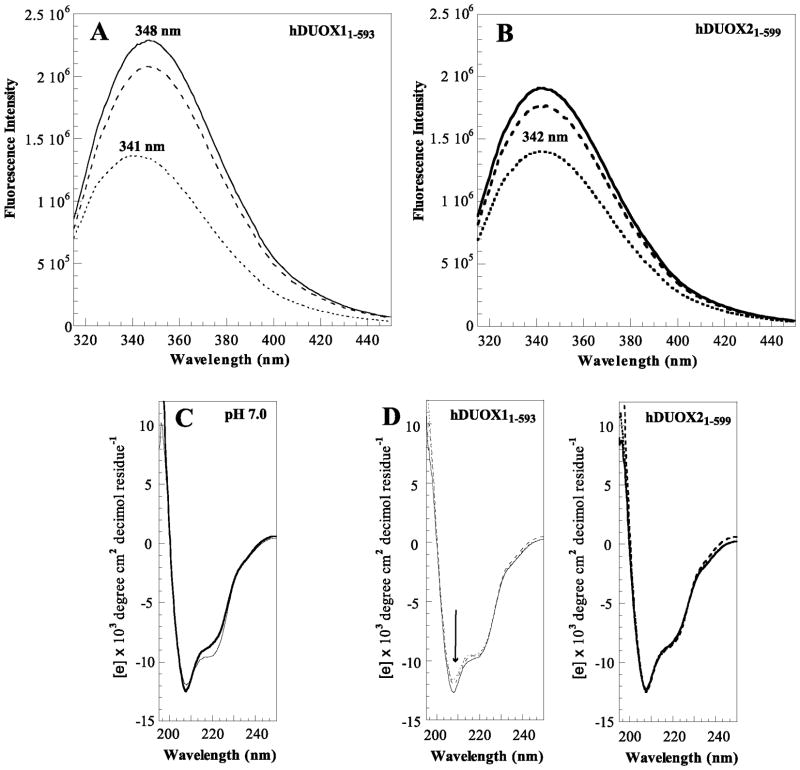

The enzymatic activities of the hDUOX isoforms have been largely investigated by analyses of in vivo expression levels, cellular localization, and regulation [3, 9, 15, 31, 32], as in vitro comparisons were not feasible. The availability of the purified domains has made it possible to investigate the differential stabilities of hDUOX11–593 and hDUOX21–599 by tryptophan (Trp) fluorescence and CD studies. Initial Trp fluorescence emission spectra, collected for each isoform by excitation at 292 nm in citrate phosphate buffer pH 7.0, exhibited broad emission bands with λmax at 348 nm (as previously reported) and 342 nm, respectively (Figure 2A). The relative intensities of these fluorescence spectra reflect the number of Trp residues in each DUOX isoform (hDUOX11–593: 19 Trp; hDUOX21–599: 15 Trp, Table 1). However the difference in the maximal emission wavelength in the absence of any heme binding suggests a subtle shift in secondary or tertiary structure. To further explore the effect of the environment upon stability, fluorescence spectra were collected over pH values that ranged from 4.0 to 9.0 (Figure 2A, 2B and S3). At pH 4.0, both proteins display the same approximate λmax of 341–342 nm, a wavelength indicative of a tightly folded protein structure. The shift in wavelength maxima from pH 4.0 to pH 7.0 for hDUOX11–593 suggests that this protein construct is less stable than hDUOX21–599 under increasingly basic conditions. Although neither wavelength maximum shifts from pH 7.0 to pH 9.0, the Trp fluorescence intensity of hDUOX11–593 continues to increase significantly; an effect not observed with hDUOX21–599. Overall, this data suggests that hDUOX21–599 is a more rigid protein than hDUOX11–593.

Figure 2.

hDUOX21–599 secondary structure. Tryptophan fluorescence emission spectra for (A) hDUOX11–593 (thin line) and (B) hDUOX21–599 (bold line), collected at a concentration of 750 nM at pH 4.0 (dotted line), pH 7.0 (dashed line), and pH 9.0 (solid line). (C) Circular dichroism (CD) spectra of hDUOX11–593 (thin line) and hDUOX21–599 (bold line) are compared at pH 7.0; (D) The CD spectra of hDUOX11–593 (left) and hDUOX21–599 (right) at pH 4.0, 7.0 and 9.0 are overlaid. All far-UV CD spectra were collected on a JASCO J-715 spectropolarimeter using a cuvette path length of 1.0 mm at 20 ºC, 4 μM. All CD experiments were conducted in 10 mM phosphate buffer; raw ellipticity data was converted to mean residue ellipticity before plotting.

Circular dichroism (CD) measurements were performed on hDUOX21–599 to confirm that it is properly folded and to compare it with hDUOX11–593. The far-UV spectra (195–250 nm) of both proteins, with prominent troughs at 208 nm and ~220 nm, support an α-helical structure characteristic of the mammalian peroxidases (Figure 2C and 2D) [33–35]. CD spectra for hDUOX21–599 demonstrate no significant differences at pH values of 4.0, 7.0 and 9.0, consistent with the stability of the Trp fluorescence wavelength over the same range of pH values. hDUOX11–593, however, demonstrates differences within the trough at 408 nm, suggesting that the α-helical structure is modified while retaining significant tertiary structure.

Activity analysis of hDUOX21–599

To compare the activities of hDUOX21–599 to those previously reported for hDUOX11–593, peroxidase activity was evaluated by the ABTS assay. No absorbance changes were observed upon enzymatic incubation of the proteins with ABTS and H2O2 even though both proteins were assayed at pH 4.0 and 7.0 (data not shown).

To determine if hDUOX21–599 had SOD activity, as has sometimes been proposed, SOD activity was evaluated by inhibition assays utilizing the substrate WST-1 [36]. Superoxide dismutase from bovine erythrocytes (Sigma-Aldrich) and hDUOX11–593 were assayed as controls. All enzyme stocks were initially diluted into HEPES buffer at pH 7.0 or citric acid buffer at pH 4.0 prior to the assay. As previously reported, optimal SOD reactivity occurs at pH 7.8, but our control SOD activity decreased only modestly at pH 4.0, remaining at or above 90% of the maximum under all conditions [37]. Neither DUOX isoforms displayed significant SOD activity at a 1 μM concentration regardless of the buffer pH (Figure S4). DUOX SOD assays were also attempted in the presence of heme, lipids (DLPC, DLPS) and calcium (100 μM), with insignificant effect on the observed activity (data not shown). The lack of peroxidase or SOD activity by both hDUOX domains suggests that they have as yet unidentified functions or are lacking components required for proper function.

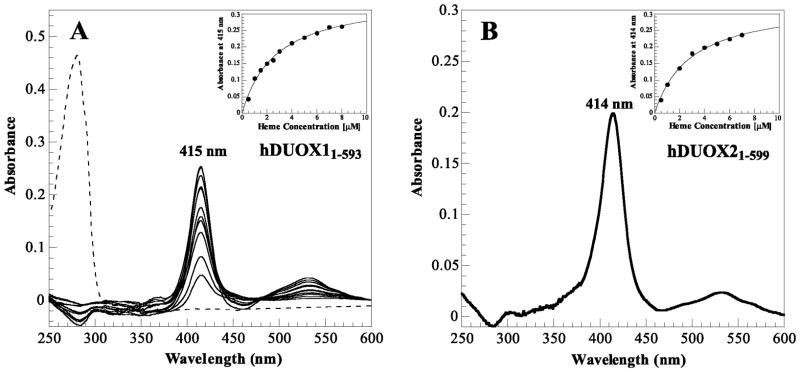

Heme binding to hDUOX11–593 and hDUOX21–599

Neither hDUOX “peroxidase” domain co-purifies with heme bound to the protein. Nevertheless, the potential exists for the binding of heme even in the absence of external factors, such as a protein-protein interaction, that might facilitate tight heme binding. To determine if heme can bind to either of the hDUOX isoforms, we titrated heme into two cuvettes with identical solutions, except that one contained the protein under study and the other buffer alone. As shown in Figure 3, a binding spectrum was observed with a Soret maximum at 415 nm for hDUOX11–593 and 414 nm for hDUOX21–599, both with broad visible peaks noted around 535 and 565 nm (Figure 3). To determine the heme binding constants, a solution of each enzyme at a fixed concentration (4 μM) was titrated with increasing amounts of heme, the difference absorbance spectra were collected, and the absorbance increase at each Soret maximum was plotted against the heme concentration (Figure 3, insets). The resulting titration curves were fitted to an equation for 1:1 binding and the resulting Kd values for hDUOX11–593 and hDUOX21–599 were 2.7 ± 0.1 and 2.4 ± 0.4 μM, respectively. Previously, pyridine hemochromogen analysis was used to establish CeDUOX11–589 heme binding at ~50% with a 408/280-nm ratio of 0.55. Based on this inexact estimation, heme binding of hDUOX11–593 and hDUOX21–599 (utilizing the ratio of the Soret maxima achieved at 7 μM heme addition vs. initial protein absorbance) was determined for both human proteins to also be ~50%. Control experiments were performed to ensure the specificity of the heme binding interaction. Extensive dialysis to remove all traces of imidazole from the purified domains produced no change in the heme binding spectra, ruling out a contribution of imidazole to the observed effect. Heme titration of a protein that does not have a heme binding site, but has a similarly exposed C-terminal 6His tag (based on elution under similar conditions from a nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose affinity column) resulted in a broad, low intensity peak centered at 422 nm (data not shown). This result confirmed that the 6His affinity tag was not responsible for the peak observed in the heme titration. Titration of the buffer alone produced no difference spectrum, establishing that our spectroscopic conditions were properly filtering out the absorbance of free heme. Finally, site specific mutagenesis based on sequence alignments that introduced the distal histidine and a glutamate residue normally involved in covalent binding of the heme in mammalian peroxidases (R241E and S331H) gave proteins that still did not co-purify with a heme group. Furthermore, these two hDUOX11–593 mutants did not exhibit a shift in the heme absorbance maximum upon titration with heme, in contrast to what is observed with many hemoproteins [38, 39].

Figure 3.

Heme titration reveals interaction with DUOX peroxidase domains. (A) Absorbance peaks from titration of hDUOX11–593 (4 μM) with heme (500 nM to 8 μM) in comparison to the background corrected protein absorbance prior to titration (dashed line); absorbance maxima at 415 nm. Inset: Titration curve for hDUOX11–593 over the heme concentrations investigated for the plotted absorbance peaks. (B) Significant peak resultant from titration of 4 μM hDUOX21–599 with 4 μM heme; absorbance maximum at 414 nm. Inset: Titration curve for hDUOX21–599 over heme concentrations ranging from 500 nm to 7 μM.

DISCUSSION

Humans express two DUOX enzymes, hDUOX1 and hDUOX2, for production of ROS in a wide variety of tissues. Studies of the catalytic mechanisms and structures of these enzymes have been hindered by their membrane association and the requirement of additional factors for their recombinant expression. Expression, solubilization, and purification of the isolated “peroxidase” domains has enabled in vitro investigations of the structure, co-factor interactions, and activity of these regions. We previously investigated the “peroxidase” domain of hDUOX1, which does not co-purify with heme, and that of C. elegans, which does [21, 40]. Here we report expression and purification of the DUOX2 “peroxidase” domain in a baculovirus system and show that this hDUOX21–599 protein, like hDUOX11–593, but unlike the C. elegans domain (CeDUOX11–589), does not co-purify with a heme group. Sequence alignments indicate that the two hDUOX domains conserve fewer of the critical residues typically found in mammalian peroxidase than does the C. elegans ortholog. Specifically they lack the proximal and distal histidines, as well as the glutamate and aspartic acid residues involved in covalent heme binding. One of the latter is present in the C. elegans domain and this presumably accounts for the fact that the heme in that protein is covalently bound.

Initial CD analysis demonstrated a characteristic α-helical fold for hDUOX21–599 reminiscent of that for both hDUOX11–593 and the mammalian peroxidases [33–35, 41, 42]. However, a tryptophan fluorescence spectrum obtained at pH 7.0 with excitation at 292 nm revealed a broad emission band with a λmax at 342 nm, significantly different from that for hDUOX11–593 at 348 nm. This wavelength is closer to the tryptophan fluorescence λmax for CeDUOX11–589 at 341 nm under the same experimental conditions. The lower Trp wavelength for hDUOX21–599, with similar tryptophan distribution throughout the protein as hDUOX11–593, suggests that it has a more tightly folded structure. To further explore this finding, Trp fluorescence spectra were collected over a range of pH values from pH 4.0 to 9.0. Interestingly, hDUOX11–593 displayed a lower λmax value (341 nm) at pH 4.0 that increased with increasing pH, reaching a value of 348 nm around pH 6.0 and remaining at this wavelength up to pH 9.0. In contrast, hDUOX21–599 showed little change in wavelength over the entire pH range, a finding consistent with a higher structural stability. A structural adjustment of hDUOX11–593 at higher pH values may be responsible for the observed shift in wavelength maximum. This shift may involve the outer residues displaying the greatest sequence variation between the two isoforms. To explore the structural perturbation further, far-UV spectra were collected at pHs 4.0, 7.0 and 9.0 for each hDUOX domain; hDUOX21–599 once again exhibits no change, whereas the hDUOX11–593 spectra reflect a small change in helical orientation. The subtleness of this spectral difference may reflect, in part, the higher protein concentration required for CD versus Trp fluorescence analyses, which introduces a higher concentration of glycerol due to the enzyme storage conditions. Clearly, while sharing high sequence identity, the DUOX isoforms have differential stability thresholds that may contribute, along with differences in regulation, expression levels, and localization, to their differential activity profiles in vivo.

The preeminent question concerning the hDUOX peroxidase domains is whether they are able to bind heme. As already noted, we previously demonstrated that the C. elegans CeDUOX11–589 domain bound heme covalently, whereas hDUOX11–593 did not co-purify with a heme group and had no peroxidase or SOD activity [21]. However, the inability of hDUOX1 to compensate for loss of hDUOX2 in vivo suggested that hDUOX2 might differ from hDUOX1 in its heme binding potential. Here we show that hDUOX21–599 also does not co-purify with a heme co-factor. However, titrations of both hDUOX11–593 and hDUOX21–599 at physiological pH with heme gives rise to prominent, heme concentration-dependent Soret peaks centered at 415 nm (hDUOX11–593) and 414 nm (hDUOX21–599). These maxima are consistent with the Soret maxima for mammalian LPO, TPO, and eosinophil peroxidase [43–45]. Heme dissociation constants for both proteins of ~ 2.5 μM indicate that the heme is not strongly bound. Efforts to improve the heme binding affinity by introducing a distal histidine and/or glutamate residue did not yield proteins that co-purified with heme or that exhibited a Soret band shifted from that of the wild-type when titrated with heme. ABTS activity assays carried out with each hDUOX isoform in the presence of heme gave an activity comparable to that of heme alone. However, we have shown that the peroxidase activity of the C. elegans peroxidase domain is weak but critical, as membrane blistering due to failure to properly cross-link tyrosines in its outer cuticle is observed when its low peroxidase activity is diminished by mutagenesis.

In conclusion, heterologous expression of the peroxidase domain of hDUOX2 has allowed the first direct in vitro comparison of the “peroxidase” domains of the human DUOX isoforms. The results provide clear evidence that the hDUOX proteins have a heme binding site, although they bind heme with weak affinity. This suggests the possibility that a conformational difference in the structure of the “peroxidase” domain in the intact, full-length protein, or interaction with a partner such as DUOXA2, may improve the affinity of the heme binding site and thus promote a catalytic heme activity.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Human Duox1 cannot substitute for Duox2 in thyroid hormone synthesis.

Duox2. like Duox1, yields a protein that does not co-purify with heme.

Duox2 peroxidase-like domain is more structurally stable than that of Duox1.

Heme titrations show both Duox peroxidase-like domains bind heme weakly.

Tighter heme binding may require interaction with a protein partner such as DuoxA2.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the UCSF mass spectrometry facility (supported by NIH grant NCRR P41RR001614) and David Maltby for the LCMS-MS data analysis of trypsin digested hDUOX2 protein samples. Thanks are also extended to the Shoichet lab for the use of their JASCO J-715 spectropolarimeter. This work was partially supported by NIH grant DK30297.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ROS

superoxide + H2O2

- NOX

NADPH oxidase

- DUOX

dual oxidase

- TPO

thyroid peroxidase

- LPO

lactoperoxidase

- CD

circular dichroism

- ABTS

2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoleline-6-sulfonic acid

- Trp

tryptophan

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Dupuy C, Ohayon R, Valent A, Noel-Hudson MS, Deme D, Virion A. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:37265–37269. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.52.37265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Deken X, Wang D, Many MC, Costagliola S, Libert F, Vassart G, Dumont JE, Miot F. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:23227–23233. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000916200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pachucki J, Wang D, Christophe D, Miot F. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2004;214:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2003.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ameziane-El-Hassani R, Morand S, Boucher JL, Frapart YM, Apostolou D, Agnandji D, Gnidehou S, Ohayon R, Noel-Hudson MS, Francon J, Lalaoui K, Virion A, Dupuy C. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:30046–30054. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500516200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Deken X, Wang D, Dumont JE, Miot F. Exp Cell Res. 2002;273:187–196. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morand S, Ueyama T, Tsujibe S, Saito N, Korzeniowska A, Leto TL. FASEB J. 2008 doi: 10.1096/fj.08-120006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pacquelet S, Lehmann M, Luxen S, Regazzoni K, Frausto M, Noack D, Knaus UG. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:24649–24658. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709108200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang D, De Deken X, Milenkovic M, Song Y, Pirson I, Dumont JE, Miot F. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:3096–3103. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407709200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rigutto S, Hoste C, Grasberger H, Milenkovic M, Communi D, Dumont JE, Corvilain B, Miot F, De Deken X. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:6725–6734. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806893200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caillou B, Dupuy C, Lacroix L, Nocera M, Talbot M, Ohayon R, Deme D, Bidart JM, Schlumberger M, Virion A. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:3351–3358. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.7.7646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moreno JC, Bikker H, Kempers MJ, van Trotsenburg AS, Baas F, de Vijlder JJ, Vulsma T, Ris-Stalpers C. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:95–102. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morand S, Agnandji D, Noel-Hudson MS, Nicolas V, Buisson S, Macon-Lemaitre L, Gnidehou S, Kaniewski J, Ohayon R, Virion A, Dupuy C. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:30244–30251. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405406200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vigone MC, Fugazzola L, Zamproni I, Passoni A, Di Candia S, Chiumello G, Persani L, Weber G. Hum Mutat. 2005;26:395. doi: 10.1002/humu.9372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maruo Y, Takahashi H, Soeda I, Nishikura N, Matsui K, Ota Y, Mimura Y, Mori A, Sato H, Takeuchi Y. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:4261–4267. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geiszt M, Witta J, Baffi J, Lekstrom K, Leto TL. FASEB J. 2003;17:1502–1504. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1104fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dupuy C, Pomerance M, Ohayon R, Noel-Hudson MS, Deme D, Chaaraoui M, Francon J, Virion A. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;277:287–292. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.El Hassani RA, Benfares N, Caillou B, Talbot M, Sabourin JC, Belotte V, Morand S, Gnidehou S, Agnandji D, Ohayon R, Kaniewski J, Noel-Hudson MS, Bidart JM, Schlumberger M, Virion A, Dupuy C. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288:G933–942. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00198.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ris-Stalpers C. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:1563–1572. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Song Y, Ruf J, Lothaire P, Dequanter D, Andry G, Willemse E, Dumont JE, Van Sande J, De Deken X. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:375–382. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harper RW, Xu C, McManus M, Heidersbach A, Eiserich JP. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:5150–5154. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meitzler JL, Ortiz de Montellano PR. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:18634–18643. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.013581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hildebrandt AG, Roots I, Tjoe M, Heinemeyer G. Methods Enzymol. 1978;52:342–350. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(78)52037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer EL. J Mol Biol. 2001;305:567–580. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arnold K, Bordoli L, Kopp J, Schwede T. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:195–201. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bradford MM. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1006/abio.1976.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Varela V, Rivolta CM, Esperante SA, Gruneiro-Papendieck L, Chiesa A, Targovnik HM. Clin Chem. 2006;52:182–191. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.058321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pfarr N, Korsch E, Kaspers S, Herbst A, Stach A, Zimmer C, Pohlenz J. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2006;65:810–815. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2006.02672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohye H, Sugawara M. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2010;235:424–433. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2009.009241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fortunato RS, Lima de Souza EC, Ameziane-el Hassani R, Boufraqech M, Weyemi U, Talbot M, Lagente-Chevallier O, de Carvalho DP, Bidart JM, Schlumberger M, Dupuy C. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:5403–5411. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Edens WA, Sharling L, Cheng G, Shapira R, Kinkade JM, Lee T, Edens HA, Tang X, Sullards C, Flaherty DB, Benian GM, Lambeth JD. J Cell Biol. 2001;154:879–891. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200103132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lambeth JD, Kawahara T, Diebold B. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43:319–331. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Banga JP, Mahadevan D, Barton GJ, Sutton BJ, Saldanha JW, Odell E, McGregor AM. FEBS Lett. 1990;266:133–141. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81524-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tanaka T, Sato S, Kumura H, Shimazaki K. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2003;67:2254–2261. doi: 10.1271/bbb.67.2254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boscolo B, Leal SS, Ghibaudi EM, Gomes CM. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1774:1164–1172. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peskin AV, Winterbourn CC. Clin Chim Acta. 2000;293:157–166. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(99)00246-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keele BB, Jr, McCord JM, Fridovich I. J Biol Chem. 1971;246:2875–2880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang WH, Lu JX, Yao P, Xie Y, Huang ZX. Protein Eng. 2003;16:1047–1054. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzg134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Franzen S, Belyea J, Gilvey LB, Davis MF, Chaudhary CE, Sit TL, Lommel SA. Biochemistry. 2006;45:9085–9094. doi: 10.1021/bi060020z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meitzler JL, Brandman R, Ortiz de Montellano PR. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:40991–41000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.170902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Olsen RL, Syse K, Little C, Christensen TB. Biochem J. 1985;229:779–784. doi: 10.1042/bj2290779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carpena X, Vidossich P, Schroettner K, Calisto BM, Banerjee S, Stampler J, Soudi M, Furtmuller PG, Rovira C, Fita I, Obinger C. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:25929–25937. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.002154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ohtaki S, Nakagawa H, Nakamura S, Nakamura M, Yamazaki I. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:441–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Furtmuller PG, Burner U, Regelsberger G, Obinger C. Biochemistry. 2000;39:15578–15584. doi: 10.1021/bi0020271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zederbauer M, Furtmuller PG, Brogioni S, Jakopitsch C, Smulevich G, Obinger C. Nat Prod Rep. 2007;24:571–584. doi: 10.1039/b604178g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.