Abstract

We investigated the roles of gap junction communication and oxidative stress in modulating potentially lethal damage repair in human fibroblast cultures exposed to doses of α particles or γ rays that targeted all cells in the cultures. As expected, α particles were more effective than γ rays at inducing cell killing; further, holding γ-irradiated cells in the confluent state for several hours after irradiation promoted increased survival and decreased chromosomal damage. However, maintaining α-particle-irradiated cells in the confluent state for various times prior to subculture resulted in increased rather than decreased lethality and was associated with persistent DNA damage and increased protein oxidation and lipid peroxidation. Inhibiting gap junction communication with 18-α-glycyrrhetinic acid or by knockdown of connexin43, a constitutive protein of junctional channels in these cells, protected against the toxic effects in α-particle-irradiated cell cultures during confluent holding. Upregulation of antioxidant defense by ectopic overexpression of glutathione peroxidase protected against cell killing by α particles when cells were analyzed shortly after exposure. However, it did not attenuate the decrease in survival during confluent holding. Together, these findings indicate that the damaging effect of α particles results in oxidative stress, and the toxic effects in the hours after irradiation are amplified by intercellular communication, but the communicated molecule(s) is unlikely to be a substrate of glutathione peroxidase.

INTRODUCTION

It has been over four decades since it was shown in cultured human cells that radiation-induced lethal damage can be attenuated by appropriate postirradiation conditions (1). Holding X-irradiated cells in the confluent, density-inhibited state for several hours after irradiation significantly enhanced their survival (2). It has been proposed that the protective effect is due to the repair of potentially lethal damage (PLD) (3). Radiation-induced PLD repair was correlated with a loss of chromosomal aberrations, sister chromatid exchanges, and a decrease in giant cell formation (4-6). Significantly, PLD was observed in vivo in solid tumor cells after X irradiation (7). Although DNA repair has been implicated in the cellular processes leading to PLD repair (8-11), the exact mechanism(s) remains unclear.

Most PLD repair studies have been performed in mammalian cells exposed to X or γ rays (12); fewer studies investigated this phenomenon in cells exposed to high-linear energy transfer (LET) radiations (13-15). The studies generally revealed lack of increased survival when cultured cells were held in quiescence for various times at 37°C after exposure to α particles or energetic heavy ions (14, 16). High-LET radiations induce complex DNA damage and are capable of more efficient cell killing than low-LET X and γ rays (17, 18). Although high-LET radiation-induced DNA damage can be repaired, albeit with slower kinetics than DNA damage induced by low-LET radiation (19, 20), such repair does not promote increased survival during the postirradiation incubation period (13).

In recent studies, we have observed that incubation of α-particle-irradiated normal human cells at 37°C for various times prior to subculture results in decreased clonogenic survival rather than a mere lack of effect (21). A similar decrease in survival during postirradiation incubation can also be noted in results previously obtained by Raju et al. (14). These data suggest that mechanisms other than DNA repair, or that can adversely affect DNA repair, may contribute to the observed effect.

Twenty years ago, Trosko and colleagues proposed that the modulation of intercellular communication plays a major role in the response to ionizing radiation (22, 23). Furthermore, they postulated that redox-modulated events and intercellular communication act in concert to modulate radiation-induced changes in signal transduction (24). Consistent with these concepts, there has been substantial evidence from studies of cell cultures exposed to low fluences of α particles for the involvement of gap junction communication and oxidative metabolism in the propagation of stressful effects from irradiated to neighboring nonirradiated bystander cells [reviewed in refs. (25, 26)]. Here we extend these studies and examine the involvement of these mechanisms in the propagation of stressful effects among irradiated cells, which leads to enhanced toxicity in confluent cell cultures exposed to doses of α particles in which every cell in the population is irradiated.

Gap junctions are dynamic structures that are critical for diverse physiological functions (27, 28). The intercellular channels that comprise gap junctions are formed by connexin proteins, and each of the ~20 isoforms of connexin forms channels with distinct permeability properties (27). By allowing direct intercellular transfer of ions and low-molecular-weight molecules, gap junctions provide a powerful pathway for molecular signaling between cells. Though the properties of channels formed by each isoform differ, in general, connexin pores are considered to allow permeation of small molecules [reviewed in ref. (27)]. Significantly, exposure to low- or high-LET radiation upregulates and stabilizes connexin43, an effect that was associated with functional gap junction intercellular communication (GJIC) (29). Several lines of evidence support the concept that junctional communication and oxidative metabolism are interrelated (30). Redox-modulated transcription factors were shown to activate connexin43 expression in irradiated cells (31).

There is a strong connection between generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and damage that follows radiation exposure. Though a burst of excess ROS is initially produced at the time of irradiation and is believed to persist for only microseconds or less (32), radiation-induced cellular oxidative stress may be prolonged due to persistent effects on oxidative metabolism (33). Exposure to ionizing radiation may affect mitochondrial and membrane oxidases (34-36), leading to excess ROS production, and may also disrupt antioxidant activity. In this report, the involvement of oxidative stress and junctional communication in enhancing toxicity in α-particle-irradiated human cells is investigated by direct approaches whereby gap junction communication is downregulated by knockdown of connexin43, a major constitutive protein of junctional channels in skin cells, and antioxidant potential is increased by ectopic overexpression of glutathione peroxidase.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture

AG1522 normal human skin fibroblasts were obtained from the Genetics Cell Repository at the Coriell Institute for Medical Research (Camden, NJ). Stock cultures were routinely maintained in a 37°C humidified incubator in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air, and cells in passage 10 to 13 were used in experiments. Cells destined for γ irradiation were seeded in 25-cm2 polystyrene flasks, and cells for α-particle irradiation were grown in stainless steel dishes (36 mm internal diameter) with 1.5-μm-thick replaceable polyethylene terephthalate (PET) foil bottoms at a seeding density of ~1.2 × 105 cells/dish. The cells were subsequently fed on days 5, 7 and 9 with Eagle’s minimal essential medium supplemented with 12.5% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Experiments were started 48 h after the last feeding in confluent cultures where 95–98% of the cells were in G0/G1 as determined by autoradiographic measurements of [3H]thymidine uptake or flow cytometry. Synchronization of cells in G0/G1 by confluent, density inhibition of growth eliminates complications in interpreting the survival results, because radiation sensitivity changes at different phase of the cell cycle (37). This protocol also maximizes interactions among the cells.

Culturing AG1522 cells that were loaded with Calcein AM together with nonloaded cells on either PET or polystyrene showed that cells grown on these substrates communicate with each other via gap junctions, as was verified by the transfer of calcein dye from the loaded to the unloaded cells and the prevention of the transfer when the cells were incubated with gap junction inhibitors (data not shown).

Irradiations

Cells were exposed to γ rays [LET ~0.9 keV/μm (38)] from a 137Cs source (J. L. Shepherd Mark I, San Fernando, CA) at a dose rate of 1.3 Gy/min. For irradiation with α particles, cells were exposed at 37°C in a 95% air/5% CO2 atmosphere to a 0.0002 Ci241Amcollimated source housed in a helium-filled Plexiglas box at a dose rate of 2 cGy/min. Irradiation was carried out from below, through the PET base, with α particles with an average energy of 3.2 MeV [LET ~122 keV/μm (39)] at contact with the cells. The source was fitted with a photographic shutter to allow accurate delivery of the specific radiation dose (40). In all cases, control cells were handled in parallel with cells destined for irradiation but were sham-irradiated.

The absorbed dose received by a single α-particle traversal through the cell nucleus [mean nuclear thickness: 1.2 μm (41)] and the percentage of cells traversed can be calculated using the terminology and methods given by Charlton and Sephton (42). Briefly, the dose per traversal to the thin disk-shaped nucleus of the AG1522 cell is d = (0.16)(LET)/A, where A is the cross-sectional area of the cell nucleus. The units for d, LET and A are Gy, keV/μm and μm2, respectively. Considering that the LET of a 3.2 MeV α particle is 122 keV/μm and the mean nuclear area of an AG1522 cell is 144 μm2 (41), the absorbed dose from an α-particle traversal would be 13.5 cGy. Alternatively, a value of ~17.9 cGy may also be derived for the absorbed dose from a particle traversal using a straightforward calculation involving the nuclear mass (~173 pg, assuming a nuclear density of 1 g/cm3) and the energy deposited during the particle traversal [~193 keV, assuming a range over which the particle stops of 19.9 μm (35) and a continuous slowing down of the particle].

The fraction of cells f receiving exactly i traversals was calculated according to the equation f = (D/d)i exp(−D/d)/(i!), where D is the mean dose to the cell population and d is the dose to an AG1522 cell from an α-particle traversal (42). Thus, in a confluent AG1522 cell culture exposed to mean doses of 10, 50 or 80 cGy from 3.2 MeV α particles, 50, 86 and 99% of the cells, respectively, would be traversed through the nucleus by an average of one or more particle tracks.

Cell Survival

To measure PLD repair, survival curves were generated with AG1522 cells exposed to γ rays or α particles by a standard colony formation assay. Confluent cell cultures were trypsinized within 5–10 min after irradiation or after various incubation periods at 37°C. The cells were suspended in growth medium, counted, diluted and seeded in 100-mm dishes at numbers estimated to give about 150 to 200 clonogenic cells per dish. Four replicates were done for each experimental point, and the experiments were repeated two to five times. After incubation for 12 to 14 days, the plates were rinsed with PBS, fixed in ethanol, and stained with crystal violet, and colonies consisting of 50 cells or more were scored under low magnification with an Olympus dissecting microscope. Survival values were corrected for the plating efficiency, which ranged from 20 to 30%.

Micronucleus Formation

The frequency of micronucleus formation was measured by the cytokinesis block technique (43). After treatments, confluent cells were subcultured, and ~3 × 104 cells were seeded in chamber flaskettes (Nalgene Nunc, Rochester, NY) in the presence of 2 μg/ml cytochalasin B (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and incubated at 37°C. After 72 h, the cells were rinsed in PBS, fixed in ethanol, stained with Hoechst 33342 solution (1 μg/ml PBS), and viewed under a fluorescence microscope. At least 1000 cells/treatment were examined, and only micronuclei in binucleated cells were considered for analysis. At the concentration used, cytochalasin B was not toxic to AG1522 cells.

Western Blot Analyses

After treatments, the cells were harvested by trypsinization, pelleted, rinsed in PBS, repelleted and lysed in chilled radioimmune precipitation assay (RIPA) buffer [50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaF, 5 mM EDTA, 1% NP40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS] supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma) and sodium orthovanadate (1 mM). The extracted proteins were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and submitted to immunoblotting. Anti-phospho-TP53 (serine 15) (no. 9284) from Cell Signaling (Boston, MA), anti-p21Waf1 (no. 05-345) and anti-4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) (no. AB5605) from Millipore (Billerica, MA) and anti-Connexin43 (no. c6219) from Sigma were used in the analyses. Secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase and the enhanced chemiluminescence systems from GE Healthcare (Piscataway, NJ) were used for protein detection. Luminescence was determined by exposure to X-ray film, and densitometry analysis was performed with an Epson scanner and National Institutes of Health Image J software (NIH Research Services Branch, Bethesda, MD). Staining of the nitrocellulose membranes with Ponceau S Red (Sigma) or reaction of goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (sc 2030, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) with a protein of ~30 kDa was used to verify equal loading of samples (loading control).

Inhibition of Gap Junction Communication

18-α-Glycyrrhetinic acid (AGA) (Sigma), a reversible inhibitor of gap junction communication, was dissolved in DMSO and added to cell cultures at a concentration of 50 μM at 30 min prior to irradiation. The cells were incubated in the presence of the drug until they were harvested 1, 3 or 5 h later. Under this protocol, AGA did not alter the plating efficiency of unirradiated cells but did inhibit cell coupling. Control cell cultures were incubated with the dissolving vehicle.

GJA1 Small Interfering RNA Silencing

A pool of four siRNAs capable of targeting gja1 mRNA that codes for connexin43 (Cx43) was from Thermo Scientific Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO) (ON-TARGETplus SMARTpool siRNA J-011042-05, J-011042-06, J-011042-07 and J-011042-08). Scrambled siRNA Duplex was included as control. Briefly, 105 cells suspended in 75 μl electroporation buffer were transfected with Cx43-siRNA at a concentration of 50 pM by electroporation in 0.1-cm electrode gap cuvettes using a Gene Pulser Xcell™ system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The cells received two 900-V pulses of 0.07-ms duration with 5-s intervals between the pulses. A total of 0.5 × 106 cells per experiment were transfected. After transfection, the cells were diluted in growth medium and treatments were performed 72 h later when the cells were confluent, and the level of connexin43 was decreased by 85.3 ± 1.5% as verified by Western blot analyses.

Vectors and Cell Transduction with Glutathione Peroxidase

Replication-defective recombinant adenovirus type 5 with the E1 region substituted with the human genes encoding glutathione peroxidase (AdGPX) was obtained from ViraQuest (North Liberty, IA). The infectious units of the adenovirus were typically at 1 × 1010PFU/ml. At the time of infection, the growth medium was replaced with serum-free fresh medium, adenovirus was added to a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100, and cells were incubated for 24 h. They were then fed fresh medium and were used for experiments 24 h later. Total glutathione peroxidase activity was measured by the spectrophotometric method of Lawrence and Burk (44) using cumene hydroperoxide as the substrate. Typically, GPX activity was increased by about threefold in AG1522 cells transduced with AdGPX. Cells transduced with empty vector served as control.

Protein Oxidation

Protein carbonyl levels, an index of protein oxidation (45), were determined by immunoblotting using the oxyblot assay kit from Millipore (Temecula, CA). Briefly, samples containing 20 μg protein extracted from whole cell lysates were derivatized with 2,4-dini-trophenylhydrazine (DNPH) to the corresponding 2,4-dinitrophenyl-hydrazone (DNP). DNPH-derivatized protein samples were separated by SDS-PAGE, blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes, reacted with anti-dinitrophenylhydrazone antibody, and visualized by standard immune techniques.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical significance in measurements of the fraction of micronucleated cells was determined using χ2 analysis. Statistical analyses of clonogenic survival measurements were carried out using Student’s t test. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Experiments were repeated two to five times, and standard errors of the means are indicated on the figures when they are greater than the size of the points. Unless otherwise indicated, the data shown are from pooled experiments.

RESULTS

Potentially Lethal Damage Repair in γ- and α-Particle-Irradiated Human Cells and its Correlation with Induced DNA Damage and Prolonged Oxidative Stress

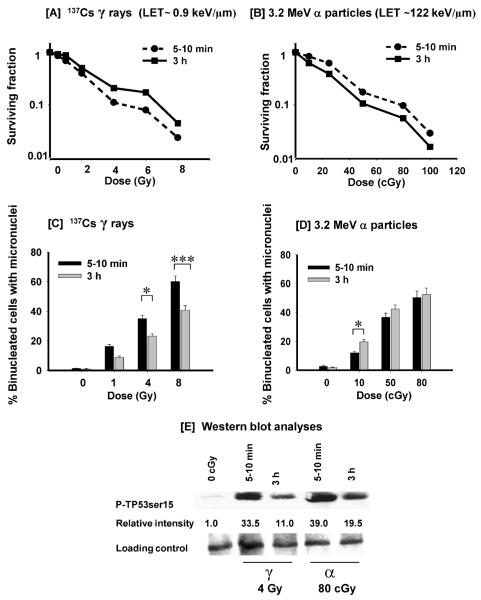

Most studies of PLD repair after α-particle irradiation have been performed in rodent or transformed human cells. Here we used AG1522 human diploid fibroblasts in the confluent state to maximize cell-cell interactions and compared, in parallel studies, the extent of PLD repair in these cells after exposure to graded doses from 3.2 MeV α particles (LET ~122 keV/μm) or 137Cs γ rays (LET ~0.9 keV/μm). The cells were trypsinized to examine clonogenic survival within 5–10 min after exposure or after a 3-h incubation at 37°C. As expected, the data in Fig. 1A and B show that α particles are more effective per unit dose than γ rays at inducing cell killing. Whereas a dose of 80 cGy from α particles reduced survival to 10% when cells were assayed shortly after exposure, a dose of 4 Gy from γ rays yielded the same effect, showing that the relative biological effectiveness (RBE) of α particles compared to γ rays under those conditions is ~5, which is consistent with previous findings (40, 46). When γ-irradiated cells were assayed for clonogenic survival after 3 h incubation, a significant increase in survival was observed at all the doses tested, indicating the occurrence of PLD repair (Fig. 1A). In contrast, a decrease rather than an increase in survival was observed in parallel experiments when cells were held in confluence for 3 h after α-particle irradiation (Fig. 1B). The results therefore show that during the incubation period, radiation-induced toxic effects were enhanced rather than attenuated. Relative to γ rays, the RBE of α particles, calculated at the 10% survival level, was ~12.5 when cells were assayed for survival 3 h after irradiation.

FIG. 1.

Potentially lethal damage repair in confluent AG1522 cells exposed to 137Cs γ rays or 3.2 MeV α particles. Panel A: Clonogenic survival of AG1522 cells exposed to increasing doses of γ rays and assayed for survival within 5–10 min (●) or 3 h (■) after exposure. Panel B: Clonogenic survival of AG1522 cells exposed to increasing doses of α particles and assayed for survival within 5–10 min (●) or 3 h (■) after exposure. Panel C: Fraction of micronucleated cells in control or γ-irradiated cultures held in confluence for various times after exposure. Panel D: Fraction of micronucleated cells in control or α-particle-irradiated cultures held in confluence for various times after exposure. Panel E: Western blot analyses of the phosphorylation of serine 15 in TP53 in γ- and α-particle-irradiated cells held in confluence for 3 h at 37°C after exposure to 4 Gy from γ rays or 80 cGy from α particles. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.0002.

Similar to clonogenic survival (Fig. 1A and B), when AG1522 cell populations were γ-irradiated (1, 4 or 8 Gy) and held in confluence for 3 h prior to subculture to assay for DNA damage in the form of micronuclei, a significant decrease (P < 0.05) in the fraction of micronucleated cells was observed when compared to cell populations that were subcultured shortly after exposure (Fig. 1C). In contrast, after α-particle irradiation (10, 50 or 80 cGy), relative to cell cultures assayed shortly after exposure, there was a slight increase rather than a decrease in the fraction of micronucleated cells when cell cultures were held in confluence for 3 h (Fig. 1D), consistent with previous findings (13). The greatest increase (P < 0.05) occurred after exposure to the low mean dose of 10 cGy at which only 50% of cells in the exposed culture are traversed by a particle track.

We also examined, by Western blot analyses, the phosphorylation of serine 15 in TP53, a marker of DNA damage (47), in irradiated cells that were harvested within 5–10 min or 3 h after exposure. Whereas the P-TP53 (serine 15) level was decreased by threefold after a 3-h incubation of cells exposed to 4 Gy from γ rays, it was decreased by twofold in cells exposed to an isosurvival dose of 80 cGy from α particles (Fig. 1E). Relative to γ-irradiated cells, these data indicate a greater level of persistent DNA damage in α-particle-irradiated cells held in confluence for 3 h; this damage may be expressed in forms other than micronuclei.

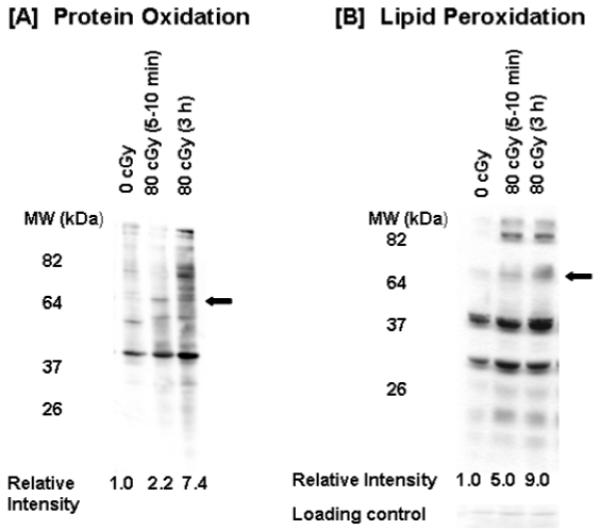

Consistent with the enhanced toxicity expressed during the 3-h incubation period after α-particle irradiation (Fig. 1B and D), an increase in protein carbonylation and lipid peroxidation was also observed (Fig. 2). This increase reflects enhanced oxidative stress that likely results from excess ROS generation caused by perturbed oxidative metabolism. The representative data in Fig. 2 show two- to threefold increases in carbonylation and 4-hydroxynonenal (HNE) modification in certain proteins in α-particle-irradiated cells during confluent holding.

FIG. 2.

Oxidative stress in α-particle-irradiated AG1522 cells. Confluent cells were exposed to 0 or 80 cGy; protein oxidation, detected by quantifying carbonylation in modified proteins (panel A), and lipid peroxidation, measured through detection of 4-hydroxynonenal adducts (panel B), were examined by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting in cells held in confluence at 37°C for 5–10 min or 3 h after exposure. Relative intensity refers to relative changes in oxidation and 4-HNE adduct accumulation in proteins highlighted with an arrow.

Role of GJIC in Propagation of Stressful Effects Among α-Particle-Irradiated Cells

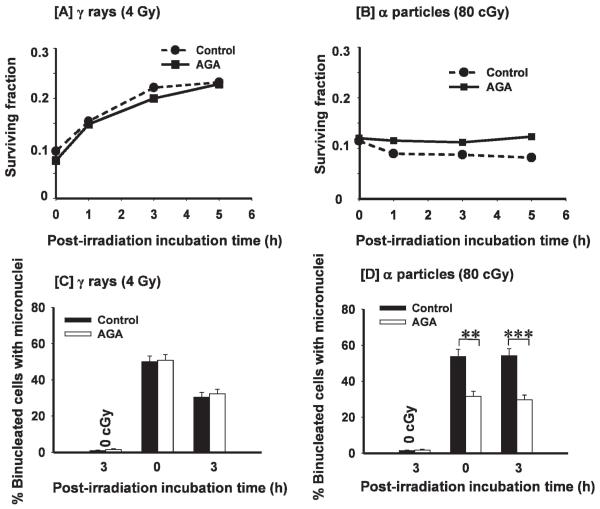

To gain insight into the mechanism(s) underlying the enhanced toxicity during the incubation period after α-particle irradiation (Fig. 1B), we investigated whether intercellular communication among irradiated cells is involved in the observed enhancement in lethal effects. To this end, confluent AG1522 cells were exposed to 80 cGy from α particles in the presence or absence of the gap junction inhibitor AGA. Parallel cultures were exposed to 4 Gy from γ rays, which results in an isosurvival level, and treated similarly with AGA. The drug (50 μM) was added 30 min prior to irradiation and remained until the cells were harvested for the clonogenic survival assay either shortly (5–10 min) after exposure or after 1- to 5-h incubation periods. At 50 μM, in AG1522 cells, AGA effectively inhibited the transfer through gap junctions of Calcein in coculture studies (data not shown) or Lucifer Yellow (48) as verified by the scrape-loading and dye transfer assay (49); it resulted in no or slight toxicity. Whereas treatment with AGA did not significantly affect the survival of γ-irradiated cells during the postexposure incubation periods, it prevented the decrease in survival that is observed in control α-particle-irradiated cells (Fig. 3A and B). In the presence of AGA, survival of α-particle-irradiated cells held in confluence for 1, 3 or 5 h prior to subculture was similar to survival of cells assayed shortly after irradiation.

FIG. 3.

Role of gap junction intercellular communication in the propagation of stressful effects among α-particle-irradiated confluent cells: Effects of the gap junction inhibitor 18-α-glycyrrhetinic acid (AGA). Panel A: Clonogenic survival of AG1522 cells exposed to 0 or 4 Gy from γ rays in the presence (■) or absence (●) of AGA. The irradiated cell populations were subcultured to assay for survival within 5–10 min or after various holding periods at 37°C. Panel B: Clonogenic survival of AG1522 cells exposed to 0 or 80 cGy from α particles in the presence (■) or absence (●) of AGA. The exposed confluent cell populations were subcultured to assay for survival within 5–10 min or after various holding periods at 37°C. Panels C and D: Fraction of micronucleated cells in control or γ-irradiated cultures (panel C) and in control or α-particle-irradiated cultures (panel D) treated as in panels A and B, respectively. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.0003.

Consistent with the above finding, the fraction of micronucleated cells was decreased in confluent cultures exposed in the presence of AGA to 80 cGy from α particles and held in quiescence in the presence of the drug for up to 3 h (P < 0.01) (Fig. 3D). In contrast, AGA did not alter micronucleus formation in γ-irradiated cells that were assayed shortly or 3 h after irradiation. Together, the data in Fig. 3 support the involvement of GJIC in the propagation, specifically among α-particle-irradiated cells, of induced stressful events. They suggest that molecules with differential effects, or different amounts of the same molecule(s), may be propagated via gap junctions among cells exposed to γ rays or to α particles, respectively.

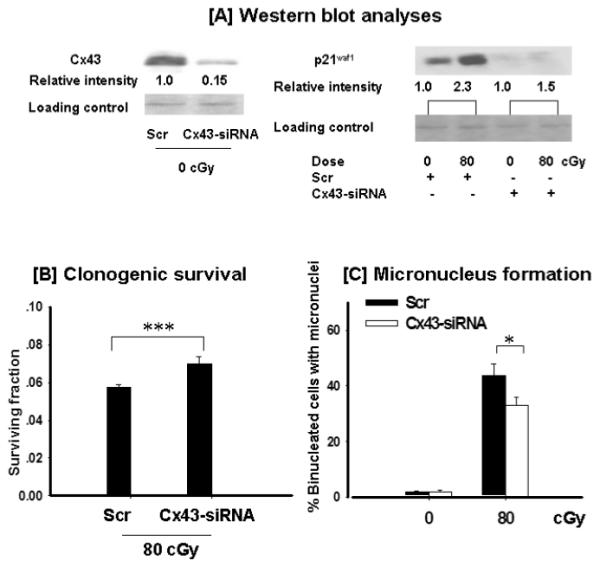

To investigate the role of GJIC in the propagation of stress among α-particle-irradiated cells more directly, we used AG1522 cells in which the expression of connexin43 was decreased by siRNA. Compared to scrambled siRNA-treated cells (Scr), transfection with connexin43 siRNA (Cx43-siRNA) reduced the level of the protein by ~85% (Fig. 4A) 72 h after transfection, a time when the experiments were performed and the cells were confluent. The morphology, cloning efficiency and colony size distribution of Scr and Cx43-siRNA-transfected AG1522 unirradiated cells were similar (data not shown). However, upon exposure to 80 cGy from α particles, the induction of p21Waf1, a downstream effector of the DNA damage and stress responsive protein p53 (50), was attenuated in Cx43-siRNA-irradiated cells (1.5-fold compared to 2.3-fold increase in Scr cells) (Fig. 4A), suggesting reduced overall stress in the exposed cells. Compared to Scr cells, incubation at 37°C for 3 h postexposure to 80 cGy resulted in a ~22% increase (P < 0.0001) in clonogenic survival in cells from cultures treated with Cx43-siRNA (Fig. 4B), which correlated with a decrease (P < 0.03) in the fraction of micronucleated cells (Fig. 4C) and downregulation of p21waf1 (Fig. 4A). These data strongly support the involvement of connexin43-mediated intercellular communication in the propagation of stressful effects among α-particle-irradiated cells.

FIG. 4.

The effect of connexin43 knockdown in the propagation of stressful effects among α-particle-irradiated cells. AG1522 fibroblasts were transfected with scrambled siRNA (Scr) or connexin43-siRNA (Cx43-siRNA) and were exposed to 80 cGy from α particles in the confluent state and harvested for analyses after 3 h incubation at 37°C. Panel A: Western blot analyses of connexin43 (Cx43) and p21waf1 (CDKN1A) expression (the relative intensity was normalized against the respective loading control). Panel B: Clonogenic survival. Panel C: Micronucleus formation. *P < 0.03; ***P < 0.0001.

Oxidative Metabolism and the Collective Response of Normal Human Cells to α-Particle Irradiation

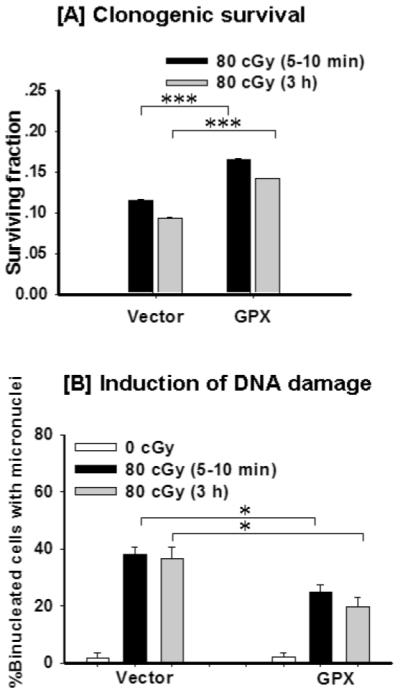

Several studies have shown that oxidative metabolism participates in the short- and long-term effects of ionizing radiation (33, 51). Notably, it mediates the propagation of stressful effects from α-particle-irradiated to neighboring bystander cells (52, 53). Here we investigated whether it also mediates the propagation of stress among irradiated cells that incur major oxidative stress from α-particle traversal (32). To this end, we measured clonogenic survival and micronucleus formation in high-dose-irradiated confluent AG1522 cells where glutathione peroxidase (GPX) had been ectopically overexpressed and in their respective controls. The GPX enzyme converts hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), a product of dismutation of superoxide radicals by the superoxide dismutases, to water (54). Though a burst of excess ROS is initially produced at the time of irradiation and is believed to persist for only microseconds or less (33), radiation-induced oxidative stress on cells may be prolonged due to persistent long-term effects on oxidative metabolism. To assess the role of metabolically generated ROS in the cellular response to radiation, we harvested cells for analyses after 3 h incubation after irradiation, a time during which propagation of signaling molecules leading to greater toxicity among irradiated cells occurs, and compared the results with effects measured within 5–10 min after exposure.

Similar to the decrease in survival observed in control cells exposed to α particles and held in confluence for 3 h (Fig. 1B), the data in Fig. 5A show that exposure to 80 cGy followed by 3 h incubation of cells transduced with empty vector also results in reduced survival when compared to cells assayed within minutes after irradiation. Cells transduced with a vector expressing GPX were more radioresistant (P < 0.0005) than empty vector-transduced cells that were assayed within minutes after irradiation, indicating that oxidizing species contribute to the lethal effects of α-particle irradiation. However, unlike the inhibition of connexin43-mediated GJIC, overexpression of GPX did not attenuate the decrease in clonogenic survival that occurred in control cells during the postirradiation incubation period (Fig. 5A). These data therefore suggest that the molecule(s) communicated among high-dose-irradiated cells enhance toxicity in these cells (Fig. 2) but themselves may not be the oxidizing species that GPX acts upon. Alternatively, the oxidative stress induced by 80 cGy from α particles may saturate antioxidant defenses, as most cells in the exposed cultures would be traversed on average by ~6 particles. The specific energy deposited in the directly hit area is expected to be very large (55) and would result in an absorbed dose of ~13 to 18 cGy per particle traversal in an AG1522 cell (42), which would cause massive oxidative ionization events that the overexpressed GPX could not entirely ameliorate. Thus residual long-lived and long-range reactive species (56, 57) may still be able to diffuse through junctional channels to enhance cell death.

FIG. 5.

The role of oxidative metabolism in the propagation of α-particle-induced stressful effects. AG1522 cells were transduced with glutathione peroxidase (GPX) or empty adenovirus vector and exposed to 0 or 80 cGy from α particles followed by 5–10 min or 3 h incubation at 37°C. Panel A: Clonogenic survival. Panel B: Micronucleus formation. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.0005.

The data in Fig. 5B (average of four experiments) describe the effect of overexpressed GPX on micronucelus formation in α-particle-irradiated cells held in confluence for 5–10 min or 3 h prior to subculture. They show that the decrease in survival observed during confluent holding of empty vector-transduced cells exposed to 80 cGy (Fig. 5A) does not correlate with an increase in micronucleus formation, which is similar to the data presented in Fig. 1D. In AdGPX-transduced cells, the frequency of micronucleated cells in cultures exposed to 80 cGy and assayed shortly after irradiation was significantly lower than that in empty vector-transduced cells exposed to the same dose of radiation, indicating radioprotection. Confluent holding of these cells for 3 h after irradiation resulted in a slight decrease in micronucleus formation.

DISCUSSION

Characterizing biological effects in cells exposed to different types of ionizing radiation and understanding the underlying mechanisms is relevant not only to issues in radiotherapy and radiation protection but also to basic knowledge of the cellular responses to stress, particularly oxidizing and clastogenic stresses. Extensive data have shown that the deposition of radiation energy into cells can cause damage to all cellular macromolecules and, depending on dose, could result in serious injury to the traversed cells (58). However, cells employ various strategies for detecting damage and repairing it (59). Holding cells in the confluent density-inhibited state after irradiation or maintaining them in growth factor-depleted medium was shown to influence the fraction of cells that survive the irradiation because of the repair of PLD (2, 3). Although PLD repair has been studied extensively for decades, the molecular and biochemical events mediating its expression remain incompletely understood, particularly for cells exposed to high-LET radiations. Such studies would have important implications for radiotherapy, because α particles and high-charge/high-energy particles, another type of high-LET radiation, are being used increasingly in cancer treatment (60, 61). Understanding the biological effects that occur shortly or a few hours after exposure to such particles may help potentiate their therapeutic efficacy and clarify the associated risks to irradiated, or bystander, normal tissues adjacent to the tumor target. Furthermore, the results of this study, although for high doses of radiation, are pertinent to our understanding of signaling events mediating low-dose effects that are relevant in radiation protection, because humans may be exposed to significant doses of α particles or high-charge and high-energy particles during specialized activities such as mining and or prolonged space travel, respectively.

Using human fibroblasts exposed to γ rays, a low-LET radiation, or α particles, a high-LET radiation, we have shown that holding α-particle-exposed cells in the confluent state for several hours after irradiation results in decreased viability (Fig. 1B) rather than the increased cell viability that occurs in γ-irradiated cells (Fig. 1A). After 3 h of confluent holding, α-particle irradiation was over 12 times more effective than γ irradiation at inducing cell killing (Fig. 1); in contrast, when survival is measured shortly after irradiation, an RBE of 5 is deduced at the 10% survival level. Significantly, our data indicate that gap junction communication mediates the propagation of events that lead to the increased toxic effects seen with α-particle radiation. Treatment of cells with a gap junction inhibitor (Fig. 3B) attenuated the enhanced lethal effect: When cells were irradiated and held in confluence in the presence of 18-α-glycyrrhetinic acid, a sparing of the enhanced toxicity was observed, and survival was similar to that measured shortly after irradiation (Fig. 3B). However, clonogenic survival was not increased as it was in γ-irradiated cells that were held in confluence after irradiation. The sparing effect was associated with a decrease in micronucleus formation (Fig. 3D). The decrease in the fraction of micronucleated cells was observed in cell populations that were subcultured for the assay shortly after exposure, suggesting that the gap junction-mediated propagation of events leading to increased lethality in α-particle-irradiated cell cultures occurs rapidly after exposure. In contrast, treatment of γ-irradiated cells with AGA did not result in a remarkable effect.

Because chemical inhibitors may not be necessarily specific in their effect, we investigated the role of GJIC in the propagation of lethal effects among α-particle-irradiated cells more directly. When cells transfected with Cx43-siRNA were exposed to an 80-cGy lethal dose of α particles and held in confluence for 3 h, clonogenic survival was increased (22 ± 1%, P < 0.0001) when compared with scrambled siRNA-transfected cells (Fig. 4B) and was associated with a decrease in micronucleus formation (Fig. 4C). It is likely that the signaling molecules propagated through gap junctions act to induce lethality in cells in the exposed population that are traversed by a small number of tracks that fail to kill the cell when survival is measured shortly after irradiation. The deposition of energy from particulate radiation is known to occur in a nonuniform pattern [reviewed in ref. (62)], and in AG1522 fibroblast cultures exposed to 80 cGy, ~1.6, 4.8, 9.5 and 14% of the cells would be traversed on average by 1, 2, 3 or 4 particle tracks, respectively (42). The communicated molecules may have induced processes that led to greater killing in these cells. In this context, it would be of interest to know how many α-particle traversals would kill an AG1522 cell. Together, our data are consistent with those of Jensen and Glazer (63) that showed greater cell killing by cisplatin in high-density cell cultures of gap junction-proficient cells. They extend our previous findings and those of others showing that GJIC is an important mechanism that mediates the propagation of stressful effects from irradiated to nonirradiated cells in low-fluence α-particle-irradiated cultures (64-66). Relative to cells assayed shortly after irradiation, the data in Fig. 1D show that a significant increase in micronucleus formation after a 3-h holding period occurred in cells from cultures exposed to an α-particle dose of 10 cGy in which 50% of the cells in the exposed population are bystanders.

The propagation of toxic effects among high-dose α-particle-irradiated cells would be of significance in radioimmunotherapy with antibodies conjugated to α-particle emitters (67). Although loss of GJIC is widely regarded to correlate with tumorigenic phenotypes, there are exceptions. Specifically, substantial evidence indicates that increased levels of connexin expression and of GJIC are correlated with invasiveness, extravasation and metastasis in a variety of cancer cells. It has also been noted that primary tumors that are initially GJIC impaired become GJIC competent at the metastatic stage (68, 69). Thus, in those situations in which tumors are treated by radioimmunotherapy with α-particle emitters, GJIC may potentiate killing of both targeted and nontargeted cells in the tumor. Although the potentiating effect on cell killing observed in this study is small (Fig. 1B), the cumulative effect in therapeutic regimens involving repeated administration of α-particle emitters would become significant. For tumor cells with reduced GJIC, development of drugs and methods that recover or increase GJIC may provide a new and potent way to enhance treatment of these tumors with high-LET radiations. Thus enhancement of GJIC by chemotherapeutic agents in tumor cells, coupled with radiotherapy using α particles, and the associated transmission of toxic compounds between cells in the irradiated tumor would offer a therapeutic gain. By corollary, transmission of toxic effects from irradiated to neighboring normal bystander cells would pose a health risk if affected normal bystander cells undergo genetic changes but yet survive and become prone to neoplastic transformation.

In addition to the role of GJIC in enhancing the toxic effects of high-fluence α particles, we investigated whether the increase in oxidative stress detected 3 h after irradiation (Fig. 2) contributes to the observed increase in cell killing (Fig. 1B). To this end, we measured clonogenic survival in α-particle-irradiated cells in which the antioxidant GPX was ectopically overexpressed. Similar to the enhanced toxicity described in Fig. 1B, holding empty vector-transduced cells in the confluent state for 3 h after exposure to a mean dose of 80 cGy resulted in a significant decrease in survival (Fig. 5A). Ectopic overexpression of GPX significantly attenuated cell killing measured shortly after irradiation, indicating that oxidative stress contributes to cell killing in α-particle-irradiated cells. It is of interest to note that the yield of H2O2 in irradiated cells is thought to increase with increasing LET (70). Thus, by more efficiently scavenging H2O2 in α-particle-irradiated cells, overexpressed GPX would protect against chemical changes to cellular macromolecules caused by H2O2 or by hydroxyl and superoxide radicals that result from its dissociation by the Haber-Weiss reaction (71). However, holding GPX-transduced cells for 3 h after α-particle irradiation did not increase survival or decrease micronucleus formation over what was observed when cells were assayed shortly after irradiation (Fig. 4A and B). The latter results suggest that death-inducing or clastogenic factors other than or in addition to oxidizing species may be directly communicated through gap junctions to enhance killing of irradiated cells that would otherwise survive. Signaling events that lead to activation of nucleases may be involved.

Although the increase in lipid peroxidation and protein carbonylation observed in our studies during confluent holding of α-particle-irradiated cells (Fig. 2) may be caused by excess ROS generated from an effect of the radiation on oxidative metabolism, ROS generated at the time of irradiation may have contributed to the effect. Whereas ~60 ROS per nanogram of tissue were estimated to be generated from a hit caused by 137Cs γ rays (67, 68) (i.e., ~10.4 ROS per cell nucleus, using a nuclear mass of ~173 pg, thus corresponding to a yield of about 1 ROS/100 eV), we estimate that over 2000 ROS are generated from an α-particle traversal, corresponding to a concentration of ~19 nM ROS in the nucleus. Such a concentration can obviously cause extensive oxidative damage. The data in Fig. 2 show an increase in 4-HNE adducts in proteins occurring within minutes after irradiation. Regardless, the net result is enhancement of cell killing that may be due to an effect of protein carbonylation and lipid peroxidation on organelle structure and function (e.g. plasma membrane) (72) as well as DNA repair proteins and their accessories (73). Oxidative damage to proteins may render them prone to segregation and degradation. It is noteworthy that carbonylation is unrepairable (74).

CONCLUSIONS

This study highlights the importance of radiation quality in the propagation of stressful effects among irradiated confluent cells. It illustrates the advantages of using high-LET radiotherapy in cancer treatment whenever appropriate. Enhancement of cell death by GJIC contributes significantly to the high RBE of α particles. Identifying the propagated factors that promote the death of irradiated cells would have obvious translational applications and would increase our understanding of radiation-induced signaling pathways. In addition, this study shows the importance of modifying biological factors and of the time after irradiation at which the effect of dose and LET in the biological responses to ionizing radiation is evaluated. The latter parameters may greatly affect the biological effectiveness of a test radiation relative to γ rays.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. James E. Trosko for his insightful suggestions and stimulating discussions and Drs. Roger W. Howell, Manuela Buonanno, Jie Zhang and Géraldine Gonon for their valuable input in the course of the experiments. Grant NNJ06HD91G from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and grant CA049062 from the National Institute of Health supported this research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Phillips RA, Tolmach LJ. Repair of potentially lethal damage in x-irradiated HeLa cells. Radiat. Res. 1966;29:413–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Little JB. Repair of sub-lethal and potentially lethal radiation damage in plateau phase cultures of human cells. Nature. 1969;224:804–806. doi: 10.1038/224804a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Little JB. Factors influencing the repair of potentially lethal radiation damage in growth-inhibited human cells. Radiat. Res. 1973;56:320–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dewey WC, Miller HH, Leeper DB. Chromosomal aberrations and mortality of x-irradiated mammalian cells: emphasis on repair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1971;68:667–671. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.3.667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hetzel FW, Kolodny GM. Radiation-induced giant cell formation: the influence of conditions which enhance repair of potentially lethal damage. Radiat. Res. 1976;68:490–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakatsugawa S, Ishizaki K, Sugahara T. The reduction in frequency of X-ray-induced sister chromatid exchanges in cultured mammalian cells during post-irradiation incubation in Hanks’ balanced salt solution. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. Relat. Stud. Phys. Chem. Med. 1978;34:489–492. doi: 10.1080/09553007814551161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hahn GM, Rockwell S, Kallman RF, Gordon LF, Frindel E. Repair of potentially lethal damage in vivo in solid tumor cells after x-irradiation. Cancer Res. 1974;34:351–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iliakis G. Effects of beta-arabinofuranosyladenine on the growth and repair of potentially lethal damage in Ehrlich ascites tumor cells. Radiat. Res. 1980;83:537–552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cornforth MN, Bedford JS. A quantitative comparison of potentially lethal damage repair and the rejoining of interphase chromosome breaks in low passage normal human fibroblasts. Radiat. Res. 1987;111:385–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iliakis G, Pantelias GE, Seaner R. Effect of arabinofuranosyladenine on radiation-induced chromosome damage in plateau-phase CHO cells measured by premature chromosome condensation: implications for repair and fixation of alpha-PLD. Radiat. Res. 1988;114:361–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raaphorst GP, Azzam EI, Feeley M, Sargent MD. Inhibitors of repair of potentially lethal damage and DNA polymerases also influence the recovery of potentially neoplastic transforming damage in C3H10T1/2 cells. Radiat. Res. 1990;123:49–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iliakis G. Radiation-induced potentially lethal damage: DNA lesions susceptible to fixation. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. Relat. Stud. Phys. Chem. Med. 1988;53:541–584. doi: 10.1080/09553008814550901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagasawa H, Robertson J, Little JB. Induction of chromosomal aberrations and sister chromatid exchanges by alpha particles in density-inhibited cultures of mouse 10T1/2 and 3T3 cells. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 1990;57:35–44. doi: 10.1080/09553009014550321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raju MR, Frank JP, Bain E, Trujillo TT, Tobey RA. Repair of potentially lethal damage in Chinese hamster cells after X and alpha irradiation. Radiat. Res. 1977;71:614–621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bertsche U, Iliakis G. Modifications in repair and expression of potentially lethal damage (alpha-PLD) as measured by delayed plating or treatment with beta-araA in plateau-phase Ehrlich ascites tumor cells after exposure to charged particles of various specific energies. Radiat. Res. 1987;111:26–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blakely EA, Chang PY, Lommel L. Cell-cycle-dependent recovery from heavy-ion damage in G1-phase cells. Radiat. Res. Suppl. 1985;8:S145–S157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barendsen GW. Impairment of the proliferative capacity of human cells in cultures by a particles of differing linear energy transfer. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 1964;8:453–466. doi: 10.1080/09553006414550561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goodhead DT. Initial events in the cellular effects of ionizing radiations: clustered damage in DNA. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 1994;65:7–17. doi: 10.1080/09553009414550021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blocher D. DNA double-strand break repair determines the RBE of alpha-particles. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 1988;54:761–771. doi: 10.1080/09553008814552201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hodgkins PS, O’Neill P, Stevens D, Fairman MP. The severity of alpha-particle-induced DNA damage is revealed by exposure to cell-free extracts. Radiat. Res. 1996;146:660–667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Azzam EI, de Toledo SM, Waker AJ, Little JB. High and low fluences of alpha-particles induce a G1 checkpoint in human diploid fibroblasts. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2623–2631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trosko JE. Possible role of intercellular communication in the modulation of the biological response to radiation. Yokohama Med. Bull. 1991;42:151–165. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trosko JE, Chang CC, Madhukar BV. Modulation of intercellular communication during radiation and chemical carcinogenesis. Radiat. Res. 1990;123:241–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trosko JE, Inoue T. Oxidative stress, signal transduction, and intercellular communication in radiation carcinogenesis. Stem Cells. 1997;15(Suppl. 2):59–67. doi: 10.1002/stem.5530150710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Azzam EI, de Toledo SM, Little JB. Oxidative metabolism, gap junctions and the ionizing radiation-induced bystander effect. Oncogene. 2003;22:7050–7057. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hei TK, Zhou H, Ivanov VN, Hong M, Lieberman HB, Brenner DJ, Amundson SA, Geard CR. Mechanism of radiation-induced bystander effects: a unifying model. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2008;60:943–950. doi: 10.1211/jpp.60.8.0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harris AL. Emerging issues of connexin channels: biophysics fills the gap. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2001;34:325–472. doi: 10.1017/s0033583501003705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mehta PP. Introduction: a tribute to cell-to-cell channels. J. Membr. Biol. 2007;217:5–12. doi: 10.1007/s00232-007-9068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Azzam EI, de Toledo SM, Little JB. Expression of CONNEXIN43 is highly sensitive to ionizing radiation and environmental stresses. Cancer Res. 2003;63:7128–7135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Upham BL, Trosko JE. Oxidative-dependent integration of signal transduction with intercellular gap junctional communication in the control of gene expression. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2009;11:297–307. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glover D, Little JB, Lavin MF, Gueven N. Low dose ionizing radiation-induced activation of connexin 43 expression. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2003;79:955–964. doi: 10.1080/09553000310001632895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muroya Y, Plante I, Azzam EI, Meesungnoen J, Katsumura Y, Jay-Gerin JP. High-LET ion radiolysis of water: visualization of the formation and evolution of ion tracks and relevance to the radiation-induced bystander effect. Radiat. Res. 2006;165:485–491. doi: 10.1667/rr3540.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spitz DR, Azzam EI, Li JJ, Gius D. Metabolic oxidation/reduction reactions and cellular responses to ionizing radiation: a unifying concept in stress response biology. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2004;23:311–322. doi: 10.1023/B:CANC.0000031769.14728.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burdon RH, Gill V. Cellularly generated active oxygen species and HeLa cell proliferation. Free Radic. Res. Commun. 1993;19:203–213. doi: 10.3109/10715769309111603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Finkel T, Holbrook NJ. Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of ageing. Nature. 2000;408:239–247. doi: 10.1038/35041687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kamata H, Hirata H. Redox regulation of cellular signalling. Cell Signal. 1999;11:1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(98)00037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Terasima R, Tolmach LJ. X-ray sensitivity and DNA synthesis in synchronous populations of HeLa cells. Science. 1963;140:490–492. doi: 10.1126/science.140.3566.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meesungnoen J, Benrahmoune M, Filali-Mouhim A, Mankhetkorn S, Jay-Gerin JP. Monte Carlo calculation of the primary radical and molecular yields of liquid water radiolysis in the linear energy transfer range 0.3–6.5 keV/μm: application to 137Cs gamma rays. Radiat. Res. 2001;155:269–278. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2001)155[0269:mccotp]2.0.co;2. Erratum, Radiat. Res. 155, 873 (2001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Watt DE. Quantities for Dosimetry of Ionizing Radiations in Liquid Water. Taylor & Francis; London: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Neti PV, de Toledo SM, Perumal V, Azzam EI, Howell RW. A multi-port low-fluence alpha-particle irradiator: fabrication, testing and benchmark radiobiological studies. Radiat. Res. 2004;161:732–738. doi: 10.1667/rr3181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raju MR, Eisen Y, Carpenter S, Inkret WC. Radiobiology of a particles. III. Cell inactivation by α-particle traversals of the cell nucleus. Radiat. Res. 1991;128:204–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Charlton DE, Sephton R. A relationship between microdosimetric spectra and cell survival for high-LET irradiation. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 1991;59:447–457. doi: 10.1080/09553009114550401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fenech M, Morley AA. Measurement of micronuclei in lymphocytes. Mutat. Res. 1985;147:29–36. doi: 10.1016/0165-1161(85)90015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lawrence RA, Burk RF. Glutathione peroxidase activity in selenium-deficient rat liver. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1976;71:952–958. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(76)90747-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dalle-Donne I, Giustarini D, Colombo R, Rossi R, Milzani A. Protein carbonylation in human diseases. Trends Mol. Med. 2003;9:169–176. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(03)00031-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Raju MR, Eisen Y, Carpenter S, Jarrett K, Harvey WF. Radiobiology of alpha particles. IV. Cell inactivation by alpha particles of energies 0.4–3.5 MeV. Radiat. Res. 1993;133:289–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Banin S, Moyal L, Shieh S, Taya Y, Anderson CW, Chessa L, Smorodinsky NI, Prives C, Reiss Y, Ziv Y. Enhanced phosphorylation of p53 by ATM in response to DNA damage. Science. 1998;281:1674–1677. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5383.1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gaillard S, Pusset D, de Toledo SM, Fromm M, Azzam EI. Propagation distance of the alpha-particle-induced bystander effect: the role of nuclear traversal and gap junction communication. Radiat. Res. 2009;171:513–520. doi: 10.1667/RR1658.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.El-Fouly MH, Trosko JE, Chang CC. Scrape-loading and dye transfer: A rapid and simple technique to study gap junctional intercellular communication. Exp. Cell Res. 1987;168:422–430. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(87)90014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.el-Deiry WS, Tokino T, Velculescu VE, Levy DB, Parsons R, Trent JM, Lin D, Mercer WE, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. WAF1, a potential mediator of p53 tumor suppression. Cell. 1993;75:817–825. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90500-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pandey BN, Gordon DA, Pain D, Azzam EI. Normal human fibroblasts exposed to high or low dose ionizing radiation: Differential effects on mitochondrial protein import and membrane potential. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2006;8:1253–1261. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Azzam EI, de Toledo SM, Spitz DR, Little JB. Oxidative metabolism modulates signal transduction and micronucleus formation in bystander cells from alpha-particle-irradiated normal human fibroblast cultures. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5436–5442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Narayanan PK, Goodwin EH, Lehnert BE. Alpha particles initiate biological production of superoxide anions and hydrogen peroxide in human cells. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3963–3971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Halliwell B, Gutteridge JMC. Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine. Clarendon Press; Oxford: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cucinotta FA, Nikjoo H, Goodhead DT. Model for radial dependence of frequency distributions for energy imparted in nanometer volumes from HZE particles. Radiat. Res. 2000;153:459–468. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2000)153[0459:mfrdof]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Koyama S, Kodama S, Suzuki K, Matsumoto T, Miyazaki T, Watanabe M. Radiation-induced long-lived radicals which cause mutation and transformation. Mutat. Res. 1998;421:45–54. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(98)00153-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Waldren CA, Vannais DB, Ueno AM. A role for long-lived radicals (LLR) in radiation-induced mutation and persistent chromosomal instability: counteraction by ascorbate and RibCys but not DMSO. Mutat. Res. 2004;551:255–265. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Little JB. Radiation carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:394–404. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.3.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Harper JW, Elledge SJ. The DNA damage response: ten years after. Mol. Cell. 2007;28:739–745. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Couturier O, Supiot S, Degraef-Mougin M, Faivre-Chauvet A, Carlier T, Chatal JF, Davodeau F, Cherel M. Cancer radioimmunotherapy with alpha-emitting nuclides. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 2005;32:601–614. doi: 10.1007/s00259-005-1803-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kitagawa A, Fujita T, Muramatsu M, Biri S, Drentje AG. Review on heavy ion radiotherapy facilities and related ion sources. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2010;81:02B909. doi: 10.1063/1.3268510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nelson GA. Fundamental space radiobiology. Gravit. Space Biol. Bull. 2003;16:29–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jensen R, Glazer PM. Cell-interdependent cisplatin killing by Ku/DNA-dependent protein kinase signaling transduced through gap junctions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:6134–6139. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400051101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Azzam EI, de Toledo SM, Gooding T, Little JB. Intercellular communication is involved in the bystander regulation of gene expression in human cells exposed to very low fluences of alpha particles. Radiat. Res. 1998;150:497–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Azzam EI, de Toledo SM, Little JB. Direct evidence for the participation of gap-junction mediated intercellular communication in the transmission of damage signals from alpha-particle irradiated to non-irradiated cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:473–478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011417098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhou H, Randers-Pehrson G, Waldren CA, Vannais D, Hall EJ, Hei TK. Induction of a bystander mutagenic effect of alpha particles in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:2099–2104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.030420797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zalutsky MR, Reardon DA, Pozzi OR, Vaidyanathan G, Bigner DD. Targeted alpha-particle radiotherapy with 211At-labeled monoclonal antibodies. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2007;34:779–785. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cronier L, Crespin S, Strale PO, Defamie N, Mesnil M. Gap junctions and cancer: new functions for an old story. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2009;11:323–338. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mesnil M, Crespin S, Avanzo JL, Zaidan-Dagli ML. Defective gap junctional intercellular communication in the carcinogenic process. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2005;1719:125–145. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Meesungnoen J, Jay-Gerin JP, Filali-Mouhim A, Mankhetkorn S. Monte Carlo calculation of the primary yields of H2O2 in the 1H+, 2H+, 4He2+, 7Li3+, and 12C6+ radiolysis of liquid water at 25 and 300°C. Can. J. Chem. 2002;80:68–75. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Halliwell B, Gutteridge JMC. Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dainiak N, Tan BJ. Utility of biological membranes as indicators for radiation exposure: alterations in membrane structure and function over time. Stem Cells. 1995;13(Suppl. 1):142–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bravard A, Vacher M, Moritz E, Vaslin L, Hall J, Epe B, Radicella JP. Oxidation status of human OGG1-S326C polymorphic variant determines cellular DNA repair capacity. Cancer Res. 2009;69:3642–3649. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nystrom T. Role of oxidative carbonylation in protein quality control and senescence. EMBO J. 2005;24:1311–1317. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]