Short abstract

Inflexible use of evidence hierarchies confuses practitioners and irritates researchers. So how can we improve the way we assess research?

The widespread use of hierarchies of evidence that grade research studies according to their quality has helped to raise awareness that some forms of evidence are more trustworthy than others. This is clearly desirable. However, the simplifications involved in creating and applying hierarchies have also led to misconceptions and abuses. In particular, criteria designed to guide inferences about the main effects of treatment have been uncritically applied to questions about aetiology, diagnosis, prognosis, or adverse effects. So should we assess evidence the way Michelin guides assess hotels and restaurants? We believe five issues should be considered in any revision or alternative approach to helping practitioners to find reliable answers to important clinical questions.

Different types of question require different types of evidence

Ever since two American social scientists introduced the concept in the early 1960s,1 hierarchies have been used almost exclusively to determine the effects of interventions. This initial focus was appropriate but has also engendered confusion. Although interventions are central to clinical decision making, practice relies on answers to a wide variety of types of clinical questions, not just the effect of interventions.2 Other hierarchies might be necessary to answer questions about aetiology, diagnosis, disease frequency, prognosis, and adverse effects.3 Thus, although a systematic review of randomised trials would be appropriate for answering questions about the main effects of a treatment, it would be ludicrous to attempt to use it to ascertain the relative accuracy of computerised versus human reading of cervical smears, the natural course of prion diseases in humans, the effect of carriership of a mutation on the risk of venous thrombosis, or the rate of vaginal adenocarcinoma in the daughters of pregnant women given diethylstilboesterol.4

Figure 1.

To answer their everyday questions, practitioners need to understand the “indications and contraindications” for different types of research evidence.5 Randomised trials can give good estimates of treatment effects but poor estimates of overall prognosis; comprehensive non-randomised inception cohort studies with prolonged follow up, however, might provide the reverse.

Systematic reviews of research are always preferred

With rare exceptions, no study, whatever the type, should be interpreted in isolation. Systematic reviews are required of the best available type of study for answering the clinical question posed.6 A systematic review does not necessarily involve quantitative pooling in a meta-analysis.

Although case reports are a less than perfect source of evidence, they are important in alerting us to potential rare harms or benefits of an effective treatment.7 Standardised reporting is certainly needed,8 but too few people know about a study showing that more than half of suspected adverse drug reactions were confirmed by subsequent, more detailed research.9 For reliable evidence on rare harms, therefore, we need a systematic review of case reports rather than a haphazard selection of them.10 Qualitative studies can also be incorporated in reviews—for example, the systematic compilation of the reasons for non-compliance with hip protectors derived from qualitative research.11

Level alone should not be used to grade evidence

The first substantial use of a hierarchy of evidence to grade health research was by the Canadian Task Force on the Preventive Health Examination.12 Although such systems are preferable to ignoring research evidence or failing to provide justification for selecting particular research reports to support recommendations, they have three big disadvantages. Firstly, the definitions of the levels vary within hierarchies so that level 2 will mean different things to different readers. Secondly, novel or hybrid research designs are not accommodated in these hierarchies—for example, reanalysis of individual data from several studies or case crossover studies within cohorts. Thirdly, and perhaps most importantly, hierarchies can lead to anomalous rankings. For example, a statement about one intervention may be graded level 1 on the basis of a systematic review of a few, small, poor quality randomised trials, whereas a statement about an alternative intervention may be graded level 2 on the basis of one large, well conducted, multicentre, randomised trial.

This ranking problem arises because of the objective of collapsing the multiple dimensions of quality (design, conduct, size, relevance, etc) into a single grade. For example, randomisation is a key methodological feature in research into interventions,13 but reducing the quality of evidence to a single level reflecting proper randomisation ignores other important dimensions of randomised clinical trials. These might include:

Other design elements, such as the validity of measurements and blinding of outcome assessments

Quality of the conduct of the study, such as loss to follow up and success of blinding

Absolute and relative size of any effects seen

Confidence intervals around the point estimates of effects.

None of the current hierarchies of evidence includes all these dimensions, and recent methodological research suggests that it may be difficult for them to do so.14 Moreover, some dimensions are more important for some clinical problems and outcomes than for others, which necessitates a tailored approach to appraising evidence.15 Thus, for important recommendations, it may be preferable to present a brief summary of the central evidence (such as “double-blind randomised controlled trials with a high degree of follow up over three years showed that...”), coupled with a brief appraisal of why particular quality dimensions are important. This broader approach to the assessment of evidence applies not only to randomised trials but also to observational studies. In the final recommendations, there will also be a role for other types of scientific evidence—for example, on aetiological and pathophysiological mechanisms—because concordance between theoretical models and the results of empirical investigations will increase confidence in the causal inferences.16,17

What to do when systematic reviews are not available

Although hierarchies can be misleading as a grading system, they can help practitioners find the best relevant evidence among a plethora of studies of diverse quality. For example, to answer a therapeutic question, the hierarchy would suggest first looking for a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. However, only a fraction of the hundreds of thousands of reports of randomised trials have been considered for possible inclusion in systematic reviews.18 So when there is no existing review, a busy clinician might next try to identify the best of several randomised trials. If the search fails to identify any randomised trials, non-randomised cohort studies might be informative. For non-therapeutic questions, however, search strategies should accommodate the need for observational designs that answer questions about aetiology, prognosis, or adverse effects.19 Whatever evidence is found, this should be clearly described rather than simply assigned to a level. Such considerations have led the authors of the BMJ's Clinical Evidence to use a hierarchy for finding evidence but to forgo grading evidence into levels. Instead, they make explicit the type of evidence on which their conclusions are based.

Balanced assessments should draw on a variety of types of research

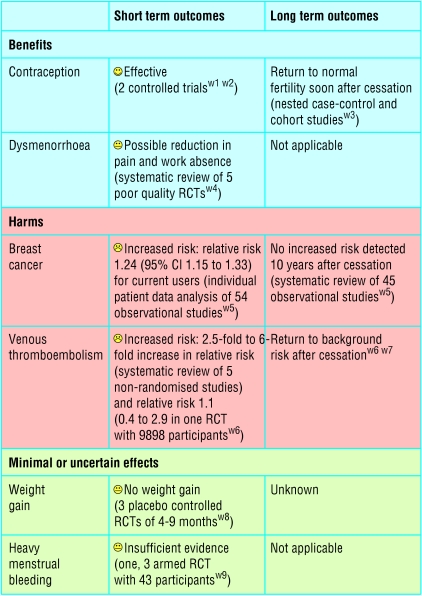

For interventions, the best available evidence for each outcome of potential importance to patients is needed.20 Often this will require systematic reviews of several different types of study. As an example, consider a woman interested in oral contraceptives. Evidence is available from controlled trials showing their contraceptive effectiveness. Although contraception is the main intended beneficial effect, some women will also be interested in the effects of oral contraceptives on acne or dysmenorrhoea. These may have been assessed in short term randomised controlled trials comparing different contraceptives. Any beneficial intended effect needs to be weighed against possible harms, such as increases in thromboembolism and breast cancer. The best evidence for such potential harms is likely to come from non-randomised cohort studies or case-control studies. For example, fears about negative consequences on fertility after long term use of oral contraceptives were allayed by such non-randomised studies. The figure gives an example of how all this information might be amalgamated into a balance sheet.21,22

Figure 2.

Example of possible evidence table for short and long term effects of oral contraceptives. (Absolute effects will vary with age and other risk factors such as smoking and blood pressure. RCT = randomised controlled trial)

Sometimes, rare, dramatic adverse effects detected with case reports or case control studies prompt further investigation and follow up of existing randomised cohorts to detect related but less severe adverse effects. For example, the case reports and case-control studies showing that intrauterine exposure to diethylstilboestrol could cause vaginal adenocarcinoma led to further investigation and follow up of the mothers and children (male as well as female) who had participated in the relevant randomised trials. These investigations showed several less serious but more frequent adverse effects of diethylstilboestrol that would have otherwise been difficult to detect.4

Conclusions

Given the flaws in evidence hierarchies that we have described, how should we proceed? We suggest that there are two broad options: firstly, to extend, improve, and standardise current evidence hierarchies22; and, secondly, to abolish the notion of evidence hierarchies and levels of evidence, and concentrate instead on teaching practitioners general principles of research so that they can use these principles to appraise the quality and relevance of particular studies.5

We have been unable to reach a consensus on which of these approaches is likely to serve the current needs of practitioners more effectively. Practitioners who seek immediate answers cannot embark on a systematic review every time a new question arises in their practice. Clinical guidelines are increasingly prepared professionally—for example, by organisations of general practitioners and of specialist physicians or the NHS National Institute for Clinical Excellence—and this work draws on the results of systematic reviews of research evidence. Such organisations might find it useful to reconsider their approach to evidence and broaden the type of problems that they examine, especially when they need to balance risks and benefits. Most importantly, however, the practitioners who use their products should understand the approach used and be able to judge easily whether a review or a guideline has been prepared reliably.

Evidence hierarchies with the randomised trial at the apex have been pivotal in the ascendancy of numerical reasoning in medicine over the past quarter century.17 Now that this principle is widely appreciated, however, we believe that it is time to broaden the scope by which evidence is assessed, so that the principles of other types of research, addressing questions on aetiology, diagnosis, prognosis, and unexpected effects of treatment, will become equally widely understood. Indeed, maybe we do have something to learn from Michelin guides: they have separate grading systems for hotels and restaurants, provide the details of the several quality dimensions behind each star rating, and add a qualitative commentary (www.viamichelin.com).

Summary points

Different types of research are needed to answer different types of clinical questions

Irrespective of the type of research, systematic reviews are necessary

Adequate grading of quality of evidence goes beyond the categorisation of research design

Risk-benefit assessments should draw on a variety of types of research

Clinicians need efficient search strategies for identifying reliable clinical research

Supplementary Material

References w1-w9 are available on bmj.com

References w1-w9 are available on bmj.com

We thank Andy Oxman and Mike Rawlins for helpful suggestions.

Contributors and sources: As a general practitioner, PG uses the his own and others' evidence assessments, and as a teacher of evidence based medicine helps others find and appraise research. JV is an internist and epidemiologist by training; he has extensively collaborated in clinical research, which made him strongly aware of the diverse types of evidence that clinicians use and need. IC's interest in these issues arose from witnessing the harm done to patients from eminence based medicine.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Campbell DT, Stanley JC. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research. Chicago, IL: Rand McNally College, 1963.

- 2.Sackett DL, Wennberg JE. Choosing the best research design for each question. BMJ 1997;315: 1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guyatt GH, Haynes RB, Jaeschke RZ, Cook DJ, Green L, Naylor CD, et al. Users' guides to the medical literature: XXV. Evidence-based medicine: principles for applying the users' guides to patient care. JAMA 2000;284: 1290-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grant A, Chalmers I. Some research strategies for investigating aetiology and assessing the effects of clinical practice. In: Macdonald RR, ed. Scientific basis of obstetrics and gynaecology. 3rd ed. London: Churchill Livingstone, 1985: 49-84.

- 5.Vandenbroucke JP. Observational research and evidence-based medicine: What should we teach young physicians? J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51: 467-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. Levels of evidence. www.cebm.net/levels_of_evidence.asp (accessed 13 Nov 2003).

- 7.Vandenbroucke JP. In defense of case reports and case series. Ann Intern Med 2001;134: 330-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aronson JK. Anecdotes as evidence. BMJ 2003;326: 1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Venning GR. Validity of anecdotal reports of suspected adverse drug reactions: the problem of false alarms. BMJ 1982;284: 249-254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jenicek M. Clinical case reporting in evidence-based medicine. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1999.

- 11.Van Schoor NM, Deville WL, Bouter LM, Lips P. Acceptance and compliance with external hip protectors: a systematic review of the literature. Osteoporos Int 2002;13: 917-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination. The periodic health examination. CMAJ 1979;121: 1193-254. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kunz R, Vist G, Oxman AD. Randomisation to protect against selection bias in healthcare trials (Cochrane methodology review). In: Cochrane Library. Issue 2. Oxford: Update Software, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Juni P, Witschi A, Bloch R, Egger M. The hazards of scoring the quality of clinical trials for meta-analysis. JAMA 1999;282: 1054-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sterne JA, Juni P, Schulz KF, Altman DG, Bartlett C, Egger M. Statistical methods for assessing the influence of study characteristics on treatment effects in “meta-epidemiological” research. Stat Med 2002;21: 1513-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hill AB. The environment and disease: association or causation? Proc R Soc Med 1965;58: 295-300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vandenbroucke JP, de Craen AJ. Alternative medicine: a “mirror image” for scientific reasoning in conventional medicine. Ann Intern Med 2001;135: 507-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mallett S, Clarke M. How many Cochrane reviews are needed to cover existing evidence on the effects of health care interventions. ACP J Club 2003;139: A11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosendaal FR. Bridging case-control studies and randomized trials. Curr Control Trials Cardiovasc Med 2001;2: 109-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glasziou PP, Irwig LI, An evidence based approach to individualising treatment. BMJ 1995;311: 1356-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skegg DCG. Oral contraception and health. BMJ 1999;318: 69-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schünemann HJ, Best D, Vist G, Oxman AD, for the GRADE Working Group. Letters, numbers, symbols and words: how to communicate grades of evidence and recommendations. CMAJ 2003;169: 677-80 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.