Non-technical summary

Two mechanisms control brain blood flow by changing blood vessel diameter: autoregulation maintains flow in the face of perfusion pressure changes, and brain metabolism adjusts flow to meet metabolic requirements. Brain blood vessel reactivity to CO2 and O2 is an important component of the latter. We used a specialised rebreathing technique to change CO2 over a wide range at constant O2, estimating brain blood flow responses from measurements of middle cerebral artery flow velocity. We found that below a threshold CO2, blood pressure was unchanged, but blood flow increased in response to CO2. This response had a sigmoidal shape, centred at a CO2 close to resting. Above the threshold, both blood flow and pressure increased with CO2. We concluded that this method measures the brain blood flow reactivity to CO2 without the confounding influence of blood pressure changes. The results obtained contribute to our understanding of brain blood flow regulation.

Abstract

Abstract

Carbon dioxide (CO2) increases cerebral blood flow and arterial blood pressure. Cerebral blood flow increases not only due to the vasodilating effect of CO2 but also because of the increased perfusion pressure after autoregulation is exhausted. Our objective was to measure the responses of both middle cerebral artery velocity (MCAv) and mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) to CO2 in human subjects using Duffin-type isoxic rebreathing tests. Comparisons of isoxic hyperoxic with isoxic hypoxic tests enabled the effect of oxygen tension to be determined. During rebreathing the MCAv response to CO2 was sigmoidal below a discernible threshold CO2 tension, increasing from a hypocapnic minimum to a hypercapnic maximum. In most subjects this threshold corresponded with the CO2 tension at which MAP began to increase. Above this threshold both MCAv and MAP increased linearly with CO2 tension. The sigmoidal MCAv response was centred at a CO2 tension close to normal resting values (overall mean 36 mmHg). While hypoxia increased the hypercapnic maximum percentage increase in MCAv with CO2 (overall means from 76.5 to 108%) it did not affect other sigmoid parameters. Hypoxia also did not alter the supra-threshold MCAv and MAP responses to CO2 (overall mean slopes 5.5% mmHg-1 and 2.1 mmHg mmHg−1, respectively), but did reduce the threshold (overall means from 51.5 to 46.8 mmHg). We concluded that in the MCAv response range below the threshold for the increase of MAP with CO2, the MCAv measurement reflects vascular reactivity to CO2 alone at a constant MAP.

Introduction

The control of the cerebral perfusion is closely linked to the regulation of the intracranial volume, which includes the arterial cerebrovascular bed, the large cerebral veins, and the cerebrospinal fluid. According to Poiseuille’ law, cerebral blood flow is determined by the cerebral perfusion pressure (arterial–intracranial) and the cerebrovascular resistance (see Edvinsson & Krause, 2002 for a review). The cerebral vascular bed exhibits flow autoregulation with respect to changes in perfusion pressure, altering the vascular resistance to regulate blood flow in the face of changes in systemic blood pressure (Panerai, 1998). Autoregulation has two components: a dynamic regulation that occurs over a few seconds and a static regulation that copes with gradual changes in perfusion pressure over time. Recently Lucas et al. (2010) examined static autoregulation and showed that when carbon dioxide (CO2) tensions are held constant at resting values, cerebral blood flow increases with systemic blood pressure. Cerebral vessels also respond to vasoactive agents such as nitric oxide and prostaglandins (Peebles et al. 2008) whose release may be mediated by velocity induced increases in shear stress.

In addition, cerebrovascular resistance is also affected by CO2 and oxygen (O2) such that vasodilation occurs at the arterioles and precapillary sphincters in response to hypercapnia (Ainslie & Duffin, 2009) and hypoxia (Ainslie & Ogoh, 2009). This sensitivity functions to assist the maintenance of central [H+], and therefore affects the respiratory central chemoreceptor stimulus (Ainslie & Duffin, 2009). The mechanism by which CO2 affects cerebrovascular resistance vessels is not fully understood. Increased CO2 leads to increased [H+], which activates voltage gated K+ channels. The resulting hyperpolarization of endothelial cells reduces intracellular calcium, which leads to vascular relaxation and hence vasodilatation (Kitazono et al. 1995; Nelson & Quayle, 1995).

Complicating the interaction of these factors is the fact that autoregulation becomes ineffective in hypercapnia (Czosnyka et al. 1993). Within the autoregulatory range the effect of CO2 during rest is currently estimated to be a 2–3% decrease in cerebral blood flow per mmHg decrease in the arterial partial pressure of CO2 ( ), limited by vasoconstriction capacity at about 10–15 mmHg. By contrast, cerebral blood flow increases by 3–4% per mmHg increase of

), limited by vasoconstriction capacity at about 10–15 mmHg. By contrast, cerebral blood flow increases by 3–4% per mmHg increase of  , reaching its highest level when

, reaching its highest level when  is elevated by 10–20 mmHg above normal resting value (Brugniaux et al. 2007).

is elevated by 10–20 mmHg above normal resting value (Brugniaux et al. 2007).

These experiments were part of a series investigating the cerebrovascular and ventilatory responses to CO2 using both steady state and rebreathing methods of assessment. This report details the rebreathing experiments. Our goal was to develop an analysis of the cerebral blood flow responses that not only accounted for the effects of CO2 and hypoxia on cerebrovscular resistance but also accounted for the effects of perfusion pressure.

Several assumptions formed the basis of this analysis, and these are elaborated in the Results section. First, we assumed that changes in cerebral blood flow with CO2 and hypoxia were uniquely attributable to their effects on cerebrovascular resistance if systemic blood pressure did not change with CO2 or hypoxia. Second, we assumed that within this range the changes in cerebral blood flow due to alterations in cerebrovascular resistance were dependent on changes in resistance vessel diameter. Consequently a maximum and minimum vasodilation exists and this control of cerebral blood flow would be limited in range. As a result of this reasoning we adopted a sigmoidal relation between cerebral blood flow and  from hypocapnia to hypercapnia as others have suggested (Ursino & Lodi, 1998; Claassen et al. 2007). We hypothesised that above the maximum vasodilation limit, cerebral blood flow is dependent on perfusion pressure. Finally we used the measurement of middle cerebral artery flow velocity to estimate cerebral blood flow as is commonly done (e.g. Dahl et al. 1992).

from hypocapnia to hypercapnia as others have suggested (Ursino & Lodi, 1998; Claassen et al. 2007). We hypothesised that above the maximum vasodilation limit, cerebral blood flow is dependent on perfusion pressure. Finally we used the measurement of middle cerebral artery flow velocity to estimate cerebral blood flow as is commonly done (e.g. Dahl et al. 1992).

We tested our assumptions and hypothesis by implementing steadily progressive increases in end-tidal  (

( ), from hypocapnia to hypercapnia, via isoxic hyperoxic and hypoxic Duffin-type rebreathing tests, monitoring ventilation and middle cerebral artery velocity (MCAv) as the surrogate for brain blood flow. During rebreathing, MCAv increased in a sigmoidal fashion with

), from hypocapnia to hypercapnia, via isoxic hyperoxic and hypoxic Duffin-type rebreathing tests, monitoring ventilation and middle cerebral artery velocity (MCAv) as the surrogate for brain blood flow. During rebreathing, MCAv increased in a sigmoidal fashion with  , from a hypocapnic minimum to a hypercapnic maximum with little change in perfusion pressure. The sigmoid response was centred at a

, from a hypocapnic minimum to a hypercapnic maximum with little change in perfusion pressure. The sigmoid response was centred at a  close to normal resting tensions. Hypoxia increased the hypercapnic plateau maximum but did not affect other parameters of the sigmoidal response. Above the hypercapnic plateau maximum there was a threshold

close to normal resting tensions. Hypoxia increased the hypercapnic plateau maximum but did not affect other parameters of the sigmoidal response. Above the hypercapnic plateau maximum there was a threshold  above which both blood pressure and cerebral blood flow increased in proportion to

above which both blood pressure and cerebral blood flow increased in proportion to  ; hypoxia did not alter these supra-threshold responses but did reduce the threshold.

; hypoxia did not alter these supra-threshold responses but did reduce the threshold.

Methods

Subjects and ethical approval

These studies conformed to the standards set by the latest revision of the Declaration of Helsinki. After approval from the Research Ethics Board of the Toronto General Hospital (University Health Network) and written informed consent 16 (9 m) healthy non-smoking subjects of mean (SD) age 27 (5.8) years were recruited for the study. Their mean (SD) heights, weights and BMI were 1.73 (0.09) m, 63.9 (9.9) kg and 21.5 (2.2). Subjects were instructed not to use alcohol, or caffeine, or over-the-counter drugs, or engage in unusual heavy physical activity for at least 12 h before each testing day.

Apparatus

During testing subjects were seated on a comfortable chair in a quiet room and fitted with a face mask. The face mask was connected to a three-way, manually operated valve via a mass flow sensor (AWM720P1 Airflow, Honeywell; Freeport, IL, USA). One way of the three-way valve was left open to room air and the other to a 2 m length of rebreathing tubing. This rebreathing tubing was supplied with gas from a programmable gas mixing system (RespirAct™; Thornhill Research Inc., Toronto, Canada) at the three-way valve and left open to room air at its distal end. This set-up allowed us to quickly and easily switch the subject between breathing room air and mixed gas. Middle cerebral artery flow velocity (MCAv) was measured using bilateral trans-cranial 2 MHz pulsed Doppler (ST3 Transcranial Doppler; Spencer Technologies, Seattle, WA, USA) sampled at 125 Hz. Other measures were arterial blood pressure determined by finger plethysmography (Nexfin; BMYE, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) sampled at 200 Hz, and  and end-tidal partial pressures of O2 (

and end-tidal partial pressures of O2 ( ) (RespirAct™, Thornhill Research Inc.) sampled at 20 Hz. Each of these instruments saved a digital record for later analysis.

) (RespirAct™, Thornhill Research Inc.) sampled at 20 Hz. Each of these instruments saved a digital record for later analysis.

Protocol

We measured the cerebrovascular response to increasing CO2 at hyperoxic and hypoxic isoxic tensions using the Duffin rebreathing method (Duffin et al. 2000; Jensen et al. 2010). Each test consisted of three phases: a baseline phase where the subjects breathed room air at rest; a hyperventilation phase where the subjects hyperventilated to a target  between 20 and 25 mmHg for 5 min; followed immediately by dynamic rebreathing. After the last breath of the hyperventilation phase the subject exhaled completely and was then switched to the rebreathing tubing, taking three deep breaths before relaxing. Dynamic rebreathing was implemented by programming the gas mixing device to supply a flow of gas with a

between 20 and 25 mmHg for 5 min; followed immediately by dynamic rebreathing. After the last breath of the hyperventilation phase the subject exhaled completely and was then switched to the rebreathing tubing, taking three deep breaths before relaxing. Dynamic rebreathing was implemented by programming the gas mixing device to supply a flow of gas with a  equal to the

equal to the  of the previous breath and O2 sufficient to maintain an isoxic

of the previous breath and O2 sufficient to maintain an isoxic  at either 150 mmHg (hyperoxic test) or 50 mmHg (hypoxic test). The hyperoxic and hypoxic rebreathing tests were separated by at least 10 min of rest and their order was randomised by a blind choice of cards.

at either 150 mmHg (hyperoxic test) or 50 mmHg (hypoxic test). The hyperoxic and hypoxic rebreathing tests were separated by at least 10 min of rest and their order was randomised by a blind choice of cards.

Data analysis

For each test, beat-by-beat values of MCAv and mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) were calculated. Then these beat-by-beat measures, and  and

and  measures were time aligned, and breath-by-breath values were calculated for MAP and MCAv. MCAv was then converted to a percentage change from the mean minimum value observed during the hyperventilation phase. MAP and MCAv as percentage change were plotted vs.

measures were time aligned, and breath-by-breath values were calculated for MAP and MCAv. MCAv was then converted to a percentage change from the mean minimum value observed during the hyperventilation phase. MAP and MCAv as percentage change were plotted vs.  for each test. To fit the MCAv response to

for each test. To fit the MCAv response to  we used the following assumptions. First, that hyperventilation of room air lowered

we used the following assumptions. First, that hyperventilation of room air lowered  sufficiently to produce a maximum CO2-modulated vasoconstriction such that vessel diameter could decrease no further. Second, that as

sufficiently to produce a maximum CO2-modulated vasoconstriction such that vessel diameter could decrease no further. Second, that as  increased from a hypocapnic value during hyperventilation to increasingly hypercapnic values during rebreathing, vasodilatation reached a maximum; the shape of this relationship was assumed to be sigmoidal (Claassen et al. 2007). Third, as hypercapnia increased further during rebreathing maximal vasodilatation had occurred, maintained by hypercapnia, and therefore cerebral blood flow was determined by perfusion pressure.The MAP response to

increased from a hypocapnic value during hyperventilation to increasingly hypercapnic values during rebreathing, vasodilatation reached a maximum; the shape of this relationship was assumed to be sigmoidal (Claassen et al. 2007). Third, as hypercapnia increased further during rebreathing maximal vasodilatation had occurred, maintained by hypercapnia, and therefore cerebral blood flow was determined by perfusion pressure.The MAP response to  was fitted with a straight line above a

was fitted with a straight line above a  threshold (TMAP) using linear regression. The MCAv response to

threshold (TMAP) using linear regression. The MCAv response to  was divided into two portions above and below a

was divided into two portions above and below a  threshold (TMCAv). The portion below TMCAv was fitted with a sigmoid curve, minimizing the sum of squares for non-linear regression (Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm), whose equation is:

threshold (TMCAv). The portion below TMCAv was fitted with a sigmoid curve, minimizing the sum of squares for non-linear regression (Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm), whose equation is:

where MCAv is the dependent variable as a percentage,  is the independent variable in mmHg, a is the minimum MCAv% determined from the mean MCAv% of the hypocapnic (hyperventilation) region (approximately zero), b is the maximum MCAv% value, c is the mid point value of MCAv%, and d is the range of the linear portion of the sigmoid (an inverse reflection of the slope of the linear portion). Above TMCAv the MCAv response to

is the independent variable in mmHg, a is the minimum MCAv% determined from the mean MCAv% of the hypocapnic (hyperventilation) region (approximately zero), b is the maximum MCAv% value, c is the mid point value of MCAv%, and d is the range of the linear portion of the sigmoid (an inverse reflection of the slope of the linear portion). Above TMCAv the MCAv response to  was fitted with a straight line based on linear regression. A linear MCAv response to MAP was derived from the supra-threshold fits of MAP vs.

was fitted with a straight line based on linear regression. A linear MCAv response to MAP was derived from the supra-threshold fits of MAP vs.  and MCAv vs.

and MCAv vs.  .

.

The alignment and fitting processes were assisted by specially written graphical analysis programs (LabVIEW; National Instruments; Austin, TX, USA). The fitting program provided a coefficient of determination measure of the sigmoid and linear fits to assist the choice of TMCAv and TMAP thresholds, which were chosen by eye so as to minimise it. The fitting parameters generated by the response analysis were examined for their differences between left and right MCAv responses and between hyperoxic and hypoxic rebreathing tests using a two-way repeated measures analysis of variance (rmANOVA) (SigmaStat; Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA, USA).

Results

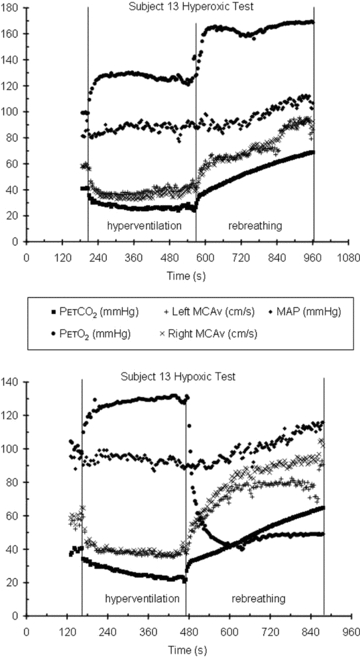

All subjects completed both hyperoxic and hypoxic rebreathing tests. However, for six subjects (5 m) the MCAv record was obtained on their dominant side only, due to technical difficulties. Figure 1 shows typical results from rebreathing tests in a subject. During hyperventilation,  declined to a mean (SD) for all tests of 25.0 (4.0) mmHg as did MCAv, and

declined to a mean (SD) for all tests of 25.0 (4.0) mmHg as did MCAv, and  rose to a mean (SD) for all tests of 130 (4.5) mmHg, with little change in MAP (mean (SD) for all tests of 86.1 (11.4) mmHg) from rest (mean (SD) for all tests of 88.2 (8.8) mmHg). MCAv declined to a minimum value, and did not decrease further despite the continuing decrease of

rose to a mean (SD) for all tests of 130 (4.5) mmHg, with little change in MAP (mean (SD) for all tests of 86.1 (11.4) mmHg) from rest (mean (SD) for all tests of 88.2 (8.8) mmHg). MCAv declined to a minimum value, and did not decrease further despite the continuing decrease of  . As the rebreathing test began,

. As the rebreathing test began,  increased rapidly during the equilibration period, and then slowly and linearly with time. MCAv also increased rapidly at the start of rebreathing, but then remained relatively constant until

increased rapidly during the equilibration period, and then slowly and linearly with time. MCAv also increased rapidly at the start of rebreathing, but then remained relatively constant until  exceeded a threshold TMCAv, after which MCAv increased linearly with time. Blood pressure changed little at the start of rebreathing in most subjects, and only increased as

exceeded a threshold TMCAv, after which MCAv increased linearly with time. Blood pressure changed little at the start of rebreathing in most subjects, and only increased as  rose above a threshold value, TMAP.

rose above a threshold value, TMAP.

Figure 1. Hyperoxic and hypoxic rebreathing tests for subject 13.

In the hyperoxic test thresholds TMAP and TMCAv are easily discerned. In the hypoxic test, although  continues to decrease during hyperventilation, MCAv reaches a minimum.

continues to decrease during hyperventilation, MCAv reaches a minimum.

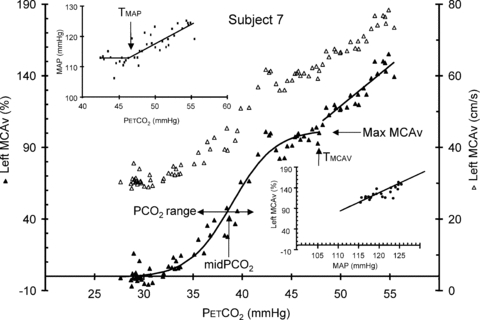

Figure 2 shows an example of fitting the MCAv response to  . The mean MCAv during the hyperventilation phase was taken as the minimum value of 0%, and all MCAv values were converted to %. As the inset plot of MAP vs.

. The mean MCAv during the hyperventilation phase was taken as the minimum value of 0%, and all MCAv values were converted to %. As the inset plot of MAP vs.  shows, MAP only increased with

shows, MAP only increased with  above a threshold, TMAP; the increase with

above a threshold, TMAP; the increase with  above this threshold was fitted with a straight line. A sigmoid model was used to fit the MCAv data between the lowest

above this threshold was fitted with a straight line. A sigmoid model was used to fit the MCAv data between the lowest  and the threshold

and the threshold  , TMCAv, where MCAv begins to increase further with

, TMCAv, where MCAv begins to increase further with  . The MCAv increase with

. The MCAv increase with  above TMCAv was also fitted with a straight line. The relation between MCAv and MAP was assumed to be linear and derived from the super-threshold lines fitted to the MCAv vs.

above TMCAv was also fitted with a straight line. The relation between MCAv and MAP was assumed to be linear and derived from the super-threshold lines fitted to the MCAv vs.  and MAP vs.

and MAP vs.  plots.

plots.

Figure 2. Hyperoxic test for subject 7.

The conversion of MCAv from cm s−1 (open triangles, right axis) to % change (filled triangles, left axis) was based on the mean minimum MCAv during hyperventilation. The sigmoid parameters for the fit to the % MCAv response are indicated, as is the threshold TMCAv at which MCAv begins to increase linearly with  . The upper inset shows the MAP vs.

. The upper inset shows the MAP vs.  response and the linear fit above the TMAP threshold. The lower inset shows the MCAv vs. MAP response and the linear fit derived from the supra-thresholds linear MAP and MCAv responses to

response and the linear fit above the TMAP threshold. The lower inset shows the MCAv vs. MAP response and the linear fit derived from the supra-thresholds linear MAP and MCAv responses to  .

.

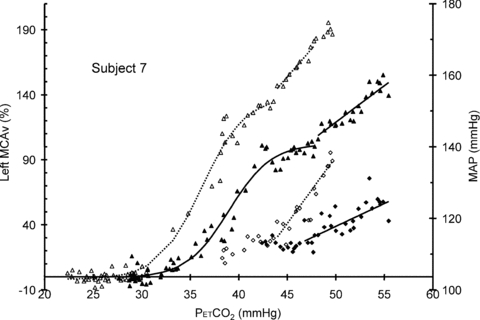

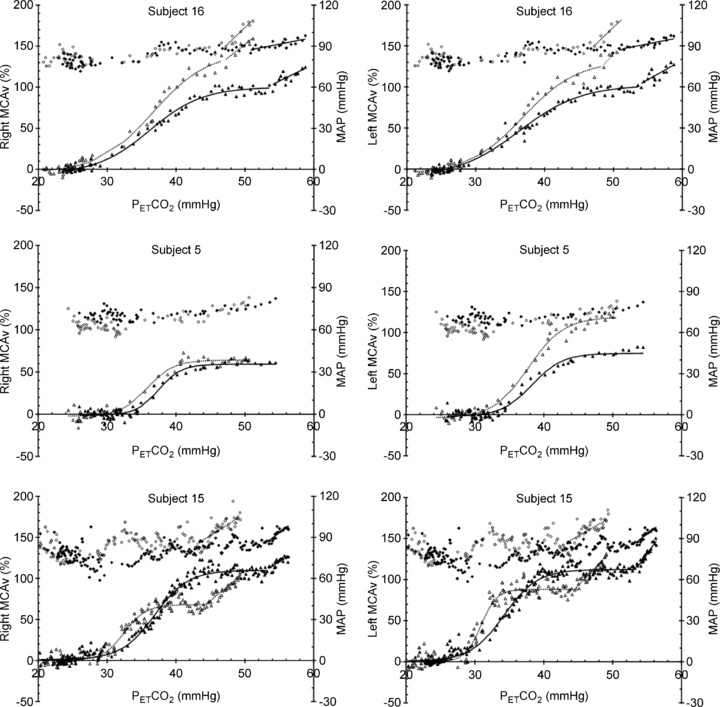

Figure 3 shows an example of both hyperoxic and hypoxic rebreathing test responses and the fits that resulted. The plateau maximum MCAv increased with hypoxia and TMAP and TMCAv thresholds decreased. In this subject the slopes of the linear responses also increased with hypoxia. Figure 4 shows example responses that illustrate the variability between subjects. While most responses resembled those of subject 16, in some responses TMAP and TMCAv thresholds were not discernible (see Table 1 for the numbers). In 6 of the 10 subjects, where both left and right responses were measured, the responses were similar but in four subjects the left and right responses differed markedly, as subject 5's responses in Fig. 4 show. Finally subjects 4, 6, 11 and 15 had MCAv responses in hypoxia that were not greater than their hyperoxic responses as subject 15 in Fig. 4 exhibits.

Figure 3.

Hyperoxic (filled) and hypoxic (open) rebreathing test MCAv (triangles) and MAP (diamonds) responses for subject 7 showing the sigmoidal and linear fits to the hyperoxic and hypoxic responses (continuous and dotted lines, respectively)

Figure 4.

Examples of the MCAv and MAP responses during rebreathing tests illustrating the variety of responses observed

Table 1.

Fit parameters

| Hyperoxic | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right | Left | |||||

| Parameters | n | Mean (SD) | CV% | n | Mean (SD) | CV% |

| MaxMCAv% (all) | 16 | 80 (25.3) | 31.6 | 10 | 78.9 (23.8) | 30.1 |

| MaxMCAv% (exclude 4, 6, 11, 15) | 12 | 78.5 (24) | 30.6 | 8 | 73.7 (23.1) | 31.4 |

Mid  (mmHg) (mmHg) |

16 | 36.8 (2.8) | 7.6 | 10 | 35.6 (2.6) | 7.2 |

range (mmHg) range (mmHg) |

16 | 3 (1.6) | 54.1 | 10 | 2.9 (1.5) | 53.1 |

| Sigmoid Slope (MCAv% mmHg-1) | 16 | 7.8 (0.5) | 20.9 | 10 | 8.1 (1.1) | 13.6 |

TMAP (mmHg) (mmHg) |

10 | 49.1 (4.1) | 8.4 | |||

MAP vs.  slope (mmHg mmHg−1) slope (mmHg mmHg−1) |

10 | 1.6 (1) | 60.1 | |||

TMCAv (mmHg) (mmHg) |

10 | 51.7 (2.8) | 5.4 | 9 | 51.6 (4.3) | 8.3 |

| MCAv vs. MAP slope (MCAv% mmHg−1) | 8 | 2.9 (0.4) | 12.6 | 7 | 3.9 (0.3) | 8.1 |

| Hypoxic | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right | Left | |||||

| n | Mean (SD) | CV% | n | Mean (SD) | CV% | |

| MaxMCAv% (all) | 15 | 101 (26.4) | 26.1 | 10 | 101.7 (27.4) | 27 |

| MaxMCAv% (exclude 4, 6, 11, 15) | 12 | 107.5 (25.4) | 23.6 | 8 | 108.9 (25) | 22.9 |

Mid  (mmHg) (mmHg) |

15 | 36 (3.2) | 8.9 | 10 | 35 (3.5) | 10 |

range (mmHg) range (mmHg) |

16 | 4.8 (9.4) | 195.4 | 10 | 2.4 (0.6) | 25.7 |

| Sigmoid slope (MCAv% mmHg-1) | 16 | 11 (0.9) | 7.4 | 10 | 10.9 (1.1) | 10.1 |

TMAP (mmHg) (mmHg) |

9 | 44.4 (3.3) | 7.5 | |||

MAP vs.  slope (mmHg mmHg−1) slope (mmHg mmHg−1) |

9 | 2.6 (1.5) | 56.6 | |||

TMCAv (mmHg) (mmHg) |

9 | 45.4 (2.4) | 5.2 | 8 | 47.4 (6.9) | 14.5 |

| MCAv vs. MAP slope (MCAv% mmHg−1) | 9 | 2.5 (0.4) | 16.7 | 4 | 2.6 (0.5) | 20.5 |

Table 1 lists the fit parameters for the MCAv and MAP responses to  , and Table 2 lists the results of the two-way rmANOVA tests for left-right and hypoxic-hyperoxic differences. For 12 of the 16 subjects (excluding subjects 4, 6, 11, 15), the plateau maximum sigmoid parameter MaxMCAv% was increased in hypoxia (P < 0.001). The sigmoid slope at MidMCAv

, and Table 2 lists the results of the two-way rmANOVA tests for left-right and hypoxic-hyperoxic differences. For 12 of the 16 subjects (excluding subjects 4, 6, 11, 15), the plateau maximum sigmoid parameter MaxMCAv% was increased in hypoxia (P < 0.001). The sigmoid slope at MidMCAv  was increased in hypoxia (P = 0.004) and the threshold TMCAv was decreased in hypoxia (P = 0.006). Although TMAP decreased in hypoxia it was not significant. A Pearson product moment analysis showed that TMAP was similar to TMCAv (P = 0.00286) with an r2 value of 0.57.

was increased in hypoxia (P = 0.004) and the threshold TMCAv was decreased in hypoxia (P = 0.006). Although TMAP decreased in hypoxia it was not significant. A Pearson product moment analysis showed that TMAP was similar to TMCAv (P = 0.00286) with an r2 value of 0.57.

Table 2.

Results of two-way rmANOVA testing for differences between right and left MCAv measurements and between hyperoxic and hypoxic rebreathing tests

| Parameters | Hyperoxic vs. Hypoxic | Right vs. Left |

|---|---|---|

| MaxMCAv% (all) | P = 0.078 | P = 0.726 |

| MaxMCAv% (exclude 4, 6, 11, 15) | P =<0.001 | P = 0.543 |

Mid  (mmHg) (mmHg) |

P = 0.526 | P = 0.275 |

range (mmHg) range (mmHg) |

P = 0.439 | P = 0.974 |

TMAP (mmHg) (mmHg) |

P = 0.057 | |

| Sigmoid slope (% mmHg-1) | P = 0.004 | P = 0.286 |

MAP vs.  slope (mmHg mmHg−1) slope (mmHg mmHg−1) |

P = 0.184 | |

TMCAv (mmHg) (mmHg) |

P = 0.006 | P = 0.545 |

| MCAv vs. MAP slope (MCAv% mmHg−1) | P = 0.143 | P = 0.117 |

Discussion

These experiments were originally designed to determine the cerebrovascular response to Duffin-type rebreathing tests by measuring MCAv and MAP. However, the somewhat unexpected result showed that this methodology was capable of measuring the MCAv response to CO2 at resting MAP. This measurement therefore complements that of Lucas et al. (2010) who measured the MCAv response to MAP at resting  .

.

We adopted a sigmoidal model for our MCAv rebreathing response analysis that included the hyperventilation phase, as did Claassen et al. (2007). However, we also included a linear response above the sigmoidal response; the latter investigators did not observe this linear increase in MCAv above a threshold. This study is also the first to take note of a break point or threshold in the MAP response to  during rebreathing. Furthermore we linked this

during rebreathing. Furthermore we linked this  threshold for the acceleration of the increase in MAP with

threshold for the acceleration of the increase in MAP with  to the

to the  threshold of the linear increase in MCAv above the sigmoidal response (TMAP=TMCAv).

threshold of the linear increase in MCAv above the sigmoidal response (TMAP=TMCAv).

The first question that we addressed was: does the MCAv during the hyperventilation phase represent a minimum?Figure 1 shows that as  decreases during hyperventilation MCAv follows to what we assumed was a minimum that does not decrease further with further decreases in

decreases during hyperventilation MCAv follows to what we assumed was a minimum that does not decrease further with further decreases in  . We suggest this assumption is correct, because it is supported by our observations, although the

. We suggest this assumption is correct, because it is supported by our observations, although the  at which the minimum MCAv occurs (mean (SD) = 28.1 (3.4) mmHg is higher than the 10–15 mmHg quoted by Brugniaux et al. (2007). The minimum values of MCAv used for the percentage change calculations did not differ significantly between left and right measures (rmANOVA P = 0.800) or between hyperoxic and hypoxic rebreathing tests (P = 0.655). In the latter case a difference would not be expected in terms of

at which the minimum MCAv occurs (mean (SD) = 28.1 (3.4) mmHg is higher than the 10–15 mmHg quoted by Brugniaux et al. (2007). The minimum values of MCAv used for the percentage change calculations did not differ significantly between left and right measures (rmANOVA P = 0.800) or between hyperoxic and hypoxic rebreathing tests (P = 0.655). In the latter case a difference would not be expected in terms of  and

and  since room air was hyperventilated for both tests, showing that the effectiveness of the hyperventilation did not differ between tests. We propose that the hyperventilation minimum is a more reliable reference standard for the percentage change in MCAv than resting MCAv values which only reflect the instantaneous vascular tone.

since room air was hyperventilated for both tests, showing that the effectiveness of the hyperventilation did not differ between tests. We propose that the hyperventilation minimum is a more reliable reference standard for the percentage change in MCAv than resting MCAv values which only reflect the instantaneous vascular tone.

We adopted a sigmoid curve to fit the MCAv response to CO2 as did Claassen et al. (2007) based on the following considerations. First, MCAv responds rapidly to changes in arterial  rather than to changes in tissue

rather than to changes in tissue  (see Ainslie & Duffin, 2009 for a review); as a result the changes in

(see Ainslie & Duffin, 2009 for a review); as a result the changes in  during a rebreathing test will induce corresponding changes in cerebrovascular resistance so that a plot of MCAv vs.

during a rebreathing test will induce corresponding changes in cerebrovascular resistance so that a plot of MCAv vs.  will reflect the shape of the response. Second, with cerebrovascular resistance a function of vessel diameter, mechanical considerations dictate a maximum and minimum diameter. Third, with cerebral vessel diameter a function of

will reflect the shape of the response. Second, with cerebrovascular resistance a function of vessel diameter, mechanical considerations dictate a maximum and minimum diameter. Third, with cerebral vessel diameter a function of  , hypocapnic hyperoxia produces a minimum MCAv as discussed in the previous paragraph; this value can be assumed to represent the minimum vessel diameter and maximum cerebrovascular resistance. Fourth, just as MCAv reached a minimum without decreasing further with decreasing

, hypocapnic hyperoxia produces a minimum MCAv as discussed in the previous paragraph; this value can be assumed to represent the minimum vessel diameter and maximum cerebrovascular resistance. Fourth, just as MCAv reached a minimum without decreasing further with decreasing  , we also observed MCAv remaining at a constant value as

, we also observed MCAv remaining at a constant value as  increased during rebreathing until a threshold

increased during rebreathing until a threshold  was reached; when there was a discernable increase in MAP, the increase in MCAv corresponded to it. For examples see subject 7 in Fig. 2 and subjects 15 and 16 in Fig. 4. Indeed, TMAP and TMCAv were significantly correlated (Pearson product moment correlation P = 0.00286) with an r2 value of 0.57. Finally we note that the mean (SD) r2 value for all sigmoid fits was 0.9 (0.1).

was reached; when there was a discernable increase in MAP, the increase in MCAv corresponded to it. For examples see subject 7 in Fig. 2 and subjects 15 and 16 in Fig. 4. Indeed, TMAP and TMCAv were significantly correlated (Pearson product moment correlation P = 0.00286) with an r2 value of 0.57. Finally we note that the mean (SD) r2 value for all sigmoid fits was 0.9 (0.1).

If the sigmoid MCAv response to CO2 correctly describes the regulation of cerebral blood flow by CO2 alone via changes in the diameter of the cerebral resistance vessels, then the mid point  not only shows the

not only shows the  at which vessel responsiveness is at a maximum but also the

at which vessel responsiveness is at a maximum but also the  at which vessel diameter is at its midpoint. It is of interest that this midpoint

at which vessel diameter is at its midpoint. It is of interest that this midpoint  is close to the resting

is close to the resting  (overall mean midpoint

(overall mean midpoint  (SD) = 36 (2.8) mmHg) because this provides the maximum cerebrovascular responsiveness at normocapnia. We suggest that since the greatest variation in MCAv with

(SD) = 36 (2.8) mmHg) because this provides the maximum cerebrovascular responsiveness at normocapnia. We suggest that since the greatest variation in MCAv with  occurs at resting

occurs at resting  , using it for normalising is inappropriate. Hypoxia increased the maximum percentage increase in MCAv significantly in the majority of subjects; only four subjects showed either no increase with hypoxia or a decrease (see subject 15 in Fig. 4). The slope of the sigmoid curve at the MidMCAv

, using it for normalising is inappropriate. Hypoxia increased the maximum percentage increase in MCAv significantly in the majority of subjects; only four subjects showed either no increase with hypoxia or a decrease (see subject 15 in Fig. 4). The slope of the sigmoid curve at the MidMCAv  is a measure of the maximum CO2 responsiveness of the vasculature and it increased in hypoxia. Hypoxia and CO2 do not interact multiplicatively but additively in controlling MCAv (Ainslie & Poulin, 2004). A significant increase in the sigmoid slope with hypoxia appears to contradict this previous finding, but we suggest that the increased sigmoid slope is an artefact of the method because the hyperventilation portion of the hypoxic test was hyperoxic rather than hypoxic. We avoided hypoxic hyperventilation because of the possibility of cerebral hypoxia.

is a measure of the maximum CO2 responsiveness of the vasculature and it increased in hypoxia. Hypoxia and CO2 do not interact multiplicatively but additively in controlling MCAv (Ainslie & Poulin, 2004). A significant increase in the sigmoid slope with hypoxia appears to contradict this previous finding, but we suggest that the increased sigmoid slope is an artefact of the method because the hyperventilation portion of the hypoxic test was hyperoxic rather than hypoxic. We avoided hypoxic hyperventilation because of the possibility of cerebral hypoxia.

Figures 2 and 4 demonstrate that the MAP response to  is characterised by a threshold

is characterised by a threshold  , TMAP, which marks a break point where MAP increases markedly with

, TMAP, which marks a break point where MAP increases markedly with  , and in most subjects TMAP was also the threshold

, and in most subjects TMAP was also the threshold  at which MCAv increases markedly, TMCAv. Indeed TMAP and TMCAv were significantly correlated (Pearson product moment P = 0.00286). Combined with the observation that a plateau in the MCAv response to

at which MCAv increases markedly, TMCAv. Indeed TMAP and TMCAv were significantly correlated (Pearson product moment P = 0.00286). Combined with the observation that a plateau in the MCAv response to  was attained below this threshold, we interpret this finding as showing that the MCAv response above this threshold is not related to CO2-induced cerebrovascular vasodilation but to the increase in cerebral blood flow produced by the increase in MAP because autoregulation is exhausted (Panerai et al. 1999). From these supra-threshold relations we derived a relationship for the MCAv response to MAP and calculated the sensitivity. We therefore suggest that cerebral blood flow increases with MAP at a mean (SD) rate of about 3.3 (1.2)% per mmHg rise in MAP when autoregulation is exceeded during hypercapnia. Lucas et al. (2010) found a value of 0.82% mmHg-1 at resting

was attained below this threshold, we interpret this finding as showing that the MCAv response above this threshold is not related to CO2-induced cerebrovascular vasodilation but to the increase in cerebral blood flow produced by the increase in MAP because autoregulation is exhausted (Panerai et al. 1999). From these supra-threshold relations we derived a relationship for the MCAv response to MAP and calculated the sensitivity. We therefore suggest that cerebral blood flow increases with MAP at a mean (SD) rate of about 3.3 (1.2)% per mmHg rise in MAP when autoregulation is exceeded during hypercapnia. Lucas et al. (2010) found a value of 0.82% mmHg-1 at resting  when autoregulation is present demonstrating its effectiveness.

when autoregulation is present demonstrating its effectiveness.

With respect to the relation between MCAv and  , below TMCAv the mean (SD) sigmoid slope maximum in hyperoxia was 7.9 (2.7)% per mmHg rise in

, below TMCAv the mean (SD) sigmoid slope maximum in hyperoxia was 7.9 (2.7)% per mmHg rise in  . Above TMCAv we found a mean (SD) slope of 5.7 (4.1)% per mmHg rise in

. Above TMCAv we found a mean (SD) slope of 5.7 (4.1)% per mmHg rise in  . Both these values are higher than previous estimates of cerebrovascular responsiveness to CO2 that used the Duffin-type rebreathing technique; Vovk et al. (2002) who found a hypercapnic slope of 2.8% mmHg-1 and Pandit et al. (2007) who found a slope of 2.7% mmHg-1). These previous estimates included only the rebreathing portion of the test and so included the plateau portion of the response to CO2 as well as the response to MAP. In addition, our slopes will be increased because we calculated the percentage change from the hypocapnic portion of the rebreathing test rather than from resting CO2 tensions.

. Both these values are higher than previous estimates of cerebrovascular responsiveness to CO2 that used the Duffin-type rebreathing technique; Vovk et al. (2002) who found a hypercapnic slope of 2.8% mmHg-1 and Pandit et al. (2007) who found a slope of 2.7% mmHg-1). These previous estimates included only the rebreathing portion of the test and so included the plateau portion of the response to CO2 as well as the response to MAP. In addition, our slopes will be increased because we calculated the percentage change from the hypocapnic portion of the rebreathing test rather than from resting CO2 tensions.

The MCAv and MAP responses we observed are discernible in several previous studies employing rebreathing but not others. However, these features were interpreted differently. Our linking of the  threshold for the acceleration of the increase in MAP with

threshold for the acceleration of the increase in MAP with  to the

to the  threshold of the linear increase in MCAv above the sigmoidal response (TMAP=TMCAv) is novel and bears discussion as follows.

threshold of the linear increase in MCAv above the sigmoidal response (TMAP=TMCAv) is novel and bears discussion as follows.

First we point out that this study is not the first to observe a break point in the MCAv response to CO2; Vovk et al. (2002), Pandit et al. (2007) and Fan et al. (2010) all show rebreathing responses with this feature. Vovk et al. (2002) interpreted the break point as an abrupt vasodilation as hypocapnic vasoconstriction is relieved. Pandit et al. (2007) averaged the response and thereby obscured this break point, and Fan et al. (2010) also disregarded the break point. These investigators therefore adopted a linear MCAv response model for the rebreathing phase of the test; they excluded the hyperventilation phase of rebreathing from the analysis. We adopted a sigmoidal model for our MCAv response analysis, including the hyperventilation phase, as did (Claassen et al. 2007), but additionally we included a linear response above the sigmoidal response; the latter investigators did not observe this linear increase in MCAv above a threshold.

This study is the first to take note of a break point or threshold in the MAP response to  during rebreathing. Although Fan et al. (2010) measured MAP it was not related to cerebral blood flow measurements during rebreathing. Vovk et al. (2002) measured the MAP rebreathing response, but although their observations show a break point in the response as we found, they did not relate the increase in cerebral blood flow to this increase in MAP. By contrast, Claassen et al. (2007) observed that MAP increased linearly with

during rebreathing. Although Fan et al. (2010) measured MAP it was not related to cerebral blood flow measurements during rebreathing. Vovk et al. (2002) measured the MAP rebreathing response, but although their observations show a break point in the response as we found, they did not relate the increase in cerebral blood flow to this increase in MAP. By contrast, Claassen et al. (2007) observed that MAP increased linearly with  during their rebreathing experiments until a plateau was reached, whereas we found a steady MAP until a threshold

during their rebreathing experiments until a plateau was reached, whereas we found a steady MAP until a threshold  was exceeded, following which MAP increased linearly with

was exceeded, following which MAP increased linearly with  ; our observations are similar to those of Vovk et al. (2002) in that respect.

; our observations are similar to those of Vovk et al. (2002) in that respect.

Our observations of MAP changes during rebreathing differ somewhat from those of Shoemaker et al. (2002) who observed sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA) and cardiovascular parameters during hypoxic and hyperoxic rebreathing tests. While they did not discern a threshold for the MAP response they did find thresholds for MSNA, cardiac output and the ratio of cardiac output/MAP; MSNA began to increase between 55 and 60 mmHg during hyperoxic rebreathing and between 45 and 50 mmHg during hypoxic rebreathing. These thresholds for MSNA are comparable to the mean (SD) TMCAv thresholds we found at 51.7 (2.8) and 45.4 (2.4) mmHg (hyperoxic vs. hypoxic) and the TMAP thresholds at 49.1 (4.1) and 44.4 (3.3) mmHg (hyperoxic vs. hypoxic). Shoemaker et al. (2002) noted, as we did, that hypoxia significantly lowered these thresholds.

All of these previous studies with the exception of that by Claassen et al. (2007) used a Duffin-type rebreathing test protocol where rebreathing is preceded by 5 min of slow deep breathing hyperventilation. By contrast, Claassen et al. (2007) preceded their rebreathing with only 15 s of rapid deep breathing. We suggest that the difference in our findings relates to the difference in the hyperventilation period preceding rebreathing. After 5 min of hyperventilation,  is decreased in all tissues including the brain so that rebreathing equilibration equalises arterial and tissue

is decreased in all tissues including the brain so that rebreathing equilibration equalises arterial and tissue  ; they then rise together during rebreathing. With only a short hyperventilation, brain tissue is not substantially reduced and consequently central chemoreceptors will be at a higher

; they then rise together during rebreathing. With only a short hyperventilation, brain tissue is not substantially reduced and consequently central chemoreceptors will be at a higher  during rebreathing.

during rebreathing.

We therefore suggest that the different hyperventilation protocols account for the differences in the sigmoid response parameters between our study and that of Claassen et al. (2007). Our mean (SD; CV) maxMCAv during the hyperoxic test was 80 (25; 32)% compared to their mean (SD; CV) ‘a’ parameter of 149 (34; 17)% and our mean (SD; CV) midMCAv  was 36 (3; 9) mmHg (for all tests) compared to their 47 (2; 6) mmHg. However, the mean (SD) sigmoid slope we measured in hyperoxia was 7.9 (2.7)% mmHg-1 (for all tests), similar to their 8 (2)% mmHg-1. The coefficients of variation were larger in our study and indicate a greater variability among our subjects’ responses. Further, Claassen et al. (2007) studied the response during normoxia, whereas we obtained responses during hyperoxia and hypoxia.

was 36 (3; 9) mmHg (for all tests) compared to their 47 (2; 6) mmHg. However, the mean (SD) sigmoid slope we measured in hyperoxia was 7.9 (2.7)% mmHg-1 (for all tests), similar to their 8 (2)% mmHg-1. The coefficients of variation were larger in our study and indicate a greater variability among our subjects’ responses. Further, Claassen et al. (2007) studied the response during normoxia, whereas we obtained responses during hyperoxia and hypoxia.

Finally, we remind the reader that some caveats must be considered when interpreting the responses we observed. As raised previously in the Introduction, we note that the measurement of middle cerebral artery flow velocity is only an estimate of cerebral blood flow (e.g. Dahl et al. 1992); nevertheless, previous research (see the review by Ainslie & Duffin, 2009) indicates that it is a reliable and valid index of cerebral blood flow. The measurement does assume no change in vessel diameter, however, which may not hold at very high CO2 tensions (Valdueza et al. 1999). Thus, our assumption of increasing MCAv with MAP alone above a certain threshold may not be correct and an alternative explanation is that vessel diameter also increases. However, the sigmoidal nature of the responses suggests that further increases in vessel diameter are unlikely. There is a time delay between  changes measured at the mouth and the resulting MCAv changes of about 7 s for hypercapnic changes (Poulin et al. 1996). Since this delay is little greater than the breath period we assumed that our breath-by-breath measures were synchronous. Finally, we point out that these tests were done on healthy subjects where end-tidal tensions are likely to be a good estimate of arterial tensions. However, the same may not be true in patients with lung disease, and using end-tidal values to estimate arterial values may not be appropriate.

changes measured at the mouth and the resulting MCAv changes of about 7 s for hypercapnic changes (Poulin et al. 1996). Since this delay is little greater than the breath period we assumed that our breath-by-breath measures were synchronous. Finally, we point out that these tests were done on healthy subjects where end-tidal tensions are likely to be a good estimate of arterial tensions. However, the same may not be true in patients with lung disease, and using end-tidal values to estimate arterial values may not be appropriate.

We conclude this discussion with the following observations. If the arguments and interpretations we have presented are accepted, then it must be concluded that the measurement of cerebrovascular reactivity to CO2 requires the concurrent measurement of MAP and maintenance of isoxia. Further, only in the MCAv response range below the threshold for the increase of MAP with CO2 does the MCAv measurement reflect vascular reactivity to CO2 alone. In the hypercapnic range, when CO2 has fully dilated the cerebral blood vessels, as shown by the plateau in MCAv, and when TMAP and TMCAv thresholds are exceeded, blood flow increases due to the increase in MAP alone. These experiments therefore demonstrate that Duffin-type rebreathing tests, when analysed as described, provide an estimate of the cerebrovascular response to CO2 at a constant blood pressure, as well as an estimate of the cerebrovascular passive response to MAP. This test will therefore allow researchers to tease out the relative contribution of MAP and CO2 reactivity to cerebral blood flow, which normally operate concurrently.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Thornhill Research Inc.

Author contributions

All authors were involved in the conception and design of these experiments. They were conducted at the Toronto General Hospital, University Health Network. A.B.-C. with the assistance of J.D. collected and analysed the data. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the data, drafting of the article, and its revision. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Declaration of Interest: J.F. is Chief Scientist and J.D. is Senior Scientist at Thornhill Research Inc. (TRI), a spin-off company from the University Health Network that developed the RespirAct™. RespirAct™ is currently a non-commercial research tool made available for this research by TRI.

References

- Ainslie PN, Poulin MJ. Ventilatory, cerebrovascular, and cardiovascular interactions in acute hypoxia: regulation by carbon dioxide. J Appl Physiol. 2004;97:149–159. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01385.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainslie PN, Duffin J. Integration of cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity and chemoreflex control of breathing: mechanisms of regulation, measurement, and interpretation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;296:R1473–R1495. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.91008.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainslie PN, Ogoh S. Regulation of cerebral blood flow during chronic hypoxia: a matter of balance. Exp Physiol. 2009;95:251–262. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2008.045575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugniaux JV, Hodges ANH, Hanly PJ, Poulin MJ. Cerebrovascular responses to altitude. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2007;158:212–223. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claassen JA, Zhang R, Fu Q, Witkowski S, Levine BD. Transcranial Doppler estimation of cerebral blood flow and cerebrovascular conductance during modified rebreathing. J Appl Physiol. 2007;102:870–877. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00906.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czosnyka M, Harris NG, Pickard JD, Piechnik S. CO2 cerebrovascular reactivity as a function of perfusion pressure–a modelling study. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1993;121:159–165. doi: 10.1007/BF01809269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl A, Lindegaard KF, Russell D, Nyberg-Hansen R, Rootwelt K, Sorteberg W, Nornes H. A comparison of transcranial Doppler and cerebral blood flow studies to assess cerebral vasoreactivity. Stroke. 1992;23:15–19. doi: 10.1161/01.str.23.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edvinsson L, Krause DN. Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. Philadelphia, PA, USA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Duffin J, Mohan RM, Vasiliou P, Stephenson R, Mahamed S. A model of the chemoreflex control of breathing in humans: model parameters measurement. Respir Physiol. 2000;120:13–26. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(00)00095-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan J-L, Burgess KR, Basnyat R, Thomas KN, Peebles KC, Lucas SJE, Lucas RAI, Donnelly J, Cotter JD, Ainslie PN. Influence of high altitude on cerebrovascular and ventilatory responsiveness to CO2. J Physiol. 2010;588:539–549. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.184051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen D, Mask G, Tschakovsky ME. Variability of the ventilatory response to Duffin's modified hyperoxic and hypoxic rebreathing procedure in healthy awake humans. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2010;170:185–197. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitazono T, Faraci FM, Taguchi H, Heistad DD. Role of potassium channels in cerebral blood vessels. Stroke. 1995;26:1713–1723. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.9.1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas SJ, Tzeng YC, Galvin SD, Thomas KN, Ogoh S, Ainslie PN. Influence of changes in blood pressure on cerebral perfusion and oxygenation. Hypertension. 2010;55:698–705. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.146290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MT, Quayle JM. Physiological roles and properties of potassium channels in arterial smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1995;268:C799–822. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.268.4.C799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandit JJ, Mohan RM, Paterson ND, Poulin MJ. Cerebral blood flow sensitivities to CO2 measured with steady-state and modified rebreathing methods. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2007;159:34–44. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panerai RB. Assessment of cerebral pressure autoregulation in humans – a review of measurement methods. Physiol Meas. 1998;19:305–338. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/19/3/001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panerai RB, Deverson ST, Mahony P, Hayes P, Evans DH. Effects of CO2 on dynamic cerebral autoregulation measurement. Physiol Meas. 1999;20:265–275. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/20/3/304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peebles KC, Richards AM, Celi L, McGrattan K, Murrell CJ, Ainslie PN. Human cerebral arteriovenous vasoactive exchange during alterations in arterial blood gases. J Appl Physiol. 2008;105:1060–1068. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90613.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulin MJ, Liang PJ, Robbins PA. Dynamics of the cerebral blood flow response to step changes in end- tidal PCO2 and PO2 in humans. J Appl Physiol. 1996;81:1084–1095. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.3.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker J, Vovk A, Cunningham D. Peripheral chemoreceptor contributions to sympathetic and cardiovascular responses during hypercapnia. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2002;80:1136–1144. doi: 10.1139/y02-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ursino M, Lodi CA. Interaction among autoregulation, CO2 reactivity, and intracranial pressure: a mathematical model. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1998;274:H1715–H1728. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.5.H1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdueza JM, Draganski B, Hoffmann O, Dirnagl U, Einhaupl KM. Analysis of CO2 vasomotor reactivity and vessel diameter changes by simultaneous venous and arterial Doppler recordings. Stroke. 1999;30:81–86. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vovk A, Cunningham DA, Kowalchuk JM, Paterson DH, Duffin J. Cerebral blood flow responses to changes in oxygen and carbon dioxide in humans. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2002;80:819–827. doi: 10.1139/y02-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]