Abstract

In the absence of HIV-1 Vif protein, the host antiviral deaminase APOBEC3G (A3G) restricts the production of infectious HIV-1 by deamination of dC residues in the negative ssDNA produced by reverse transcription. The Vif protein averts the lethal threat of deamination by precluding the packaging of A3G into assembling virions by mediating proteasomal degradation of A3G. In spite of this robust Vif activity, residual A3G molecules that escape degradation and incorporate into newly assembled virions are potentially deleterious to the virus. We hypothesized that virion-associated Vif inhibits A3G enzymatic activity, and therefore prevents lethal mutagenesis of the newly synthesized viral DNA. Here we show that: (i) Vif-proficient HIV-1 particles released from H9 cells contain A3G with lower specific activity compared with Δvif virus associated A3G; (ii) Encapsidated HIV-1 Vif inhibits the deamination activity of recombinant A3G, and (iii) Purified HIV-1 Vif protein and the Vif-derived peptide Vif25-39 inhibit A3G activity in vitro at nanomolar concentrations in an uncompetitive manner. Our results manifest the potentiality of Vif to control the deamination threat in virions or in the pre-integration complexes (PICs) following entry to target cells. Hence, virion-associated Vif could serve as a last line of defense, protecting the virus against A3G anti-viral activity.

Keywords: Deaminase, peptides, enzyme kinetics, virion, innate immunity

INTRODUCTION

Apolipoprotein B mRNA-editing enzyme-catalytic polypeptide-like 3G (APOBEC3G) is a member of a cellular cytidine deaminase family encoded within a cluster of seven APOBEC3 (A3) genes, designated A3A, B, C, D-E, F, G and H, on human chromosome 22 1; 2; 3. Other members of the cytidine deaminase family include APOBEC1, an mRNA editor in gastrointestinal cells important in the metabolism of Apolipoprotein B 1, activation-induced deaminase (AID), a lymphoid-specific DNA deaminase involved in B cell maturation and antibody diversification 4; 5 and APOBEC2, whose expression is restricted to heart and skeletal muscle 6 and is important to normal muscle development and function 7; 8. A3 proteins catalyze the deamination of cytidine through a catalytic domain containing the conserved zinc-coordinating motif (H/C)XE(X)23-28CXXC 1; 9. A3G, as well as A3B and A3F, contains two zinc-coordinating motifs which contribute unequally to the biological functions of this enzyme 10; 11; 12; 13; 14; 15; 16; 17. APOBEC proteins are involved in the restriction of endogenous retro-transposition, as they inhibit the transposition of murine IAP and MusD retro-elements in HeLa cells 18; 19, Ty1 retro-elements in yeast 20 and L1-dependent retro-transposition of Alu and small hY elements in human cells 21; 22.

In the absence of Vif, A3G provides the host with intrinsic immunity against infection through lethal editing of nascent viral reverse transcripts. This A3G activity takes place inside the virion or post-entry to target cells and involves the deamination of deoxy-cytidine residues on the newly synthesized DNA minus strand during viral reverse transcription 23; 24; 25; 26. The induced dC→dU hypermutation occurs preferentially in the 5′ (T/C)CC 3′ sequence context 24; 26; 27; 28; 29; 30 and consequently transcribes into dG→dA substitutions on the DNA plus strand. The hypermutated viral DNA is either subjected to degradation due to reduced stability, inability to complete reverse transcription and integration, or further negates HIV-1 replication due to altered viral open reading frames and inappropriate translation termination codons 23; 24; 26; 27.

HIV-1 and other lentiviruses overcome the peril of deamination by precluding the packaging of A3G into assembling virions. This is mostly carried out by Vif, which mediates the proteasomal degradation of A3G through coordinative interaction with Cullin5-ElonginB-ElonginC that forms an E3 ubiquitin ligase complex 27; 31; 32; 33; 34 . Albeit the robust potential of Vif to limit A3G encapsidation, we demonstrated that purified wild-type virions produced in restrictive H9 cells contain A3G molecules with deaminase activity 35. Based on the deamination activity, we calculated that wt particles contain 12-20 fold lower than the amounts associated with Δvif viruses, averaging to 0.3-0.8 A3G molecules per wt virion. Accumulating data show that patient-derived proviral DNA sequences often contain G- to A mutations within the A3G 5′-GG-to-AG dinucleotide contexts 36; 37; 38; 39, providing indirect evidence that A3G mutates wt HIV-1 in vivo. Deletion, insertion and stop-codon mutations were identified in gene sequences of HIV-1 derived from slow progressor AIDS patients 40 and in humanized mice 41. These observations were corroborated experimentally by demonstrating that cellular deaminases are responsible for lethal and sub-lethal mutations intensively inserted into Vif-proficient and deficient HIV-1 viruses produced in cultured cells and humanized mice 41; 42; 43. Others and we therefore speculated that the encapsidated A3G may not only inactivate the viral DNA, but might also contribute to viral diversity and fitness 41; 44; 45; 46.

Vif is naturally incorporated into virions 47; 48, but the biological significance of this observation is not fully understood. Previously it was demonstrated that Vif inhibits the deaminase activity of A3G and AID in bacteria 49; 50. We were therefore interested to determine whether the encapsidated Vif plays a role in the regulation of the virion-associated A3G. Here we report that the specific activity of A3G deaminase associated with vif-proficient viruses is lower than that of the enzyme entrapped in vif-deficient particles, suggesting that Vif inhibits virion-associated A3G. Encapsidated Vif also inhibits the enzymatic activity of recombinant A3G, further supporting this notion. Purified HIV-1Vif inhibited A3G mediated deamination in vitro in an uncompetitive manner with a K’I of 8.7*10−9 M. Screening a battery of Vif-derived peptides covering the full-length Vif protein has revealed that inhibitory sequences are scattered throughout the Vif protein. However, two sequences were implicated in efficient inhibition of A3G deaminase activity, corresponding to Vif25-39 and Vif105-119. Our data show that HIV-1-encapsidated and recombinant Vif molecules directly inhibit the enzymatic activity of A3G, suggesting a complementary mechanism for A3G neutralization by Vif inside progeny virions or in the pre-integration complex (PIC) formed post-entry to target cells.

RESULTS

1. Native HIV-1-associated A3G has reduced specific activity

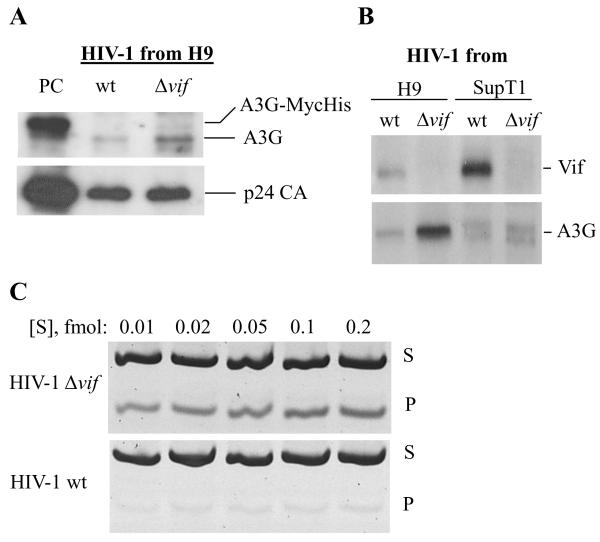

In the absence of Vif, A3G deaminates dC residues in the viral negative-strand DNA synthesized by reverse transcription post-entry to the target cell. As Vif is packaged in the virion 47; 48, we were interested to reveal whether it directly inhibits A3G enzymatic activity. Figure 1A shows that wt virions released from H9 cells contain reduced amounts of A3G molecules compared to that associated with Δvif particles. Quantification of the bands revealed that the wt particles encapsidated 5.8 times lower (approx. 17%) A3G protein than in Δvif particles (Table I). Figure 1B shows that wt particles released from H9 cells contain reduced amounts of Vif compared to particles released from the permissive Sup T1 cells, which do not express A3G.

Fig. 1. HIV-1 produced by H9 cells incorporates enzymatically active A3G protein.

A. Western blots of wild-type or HIV-1Δvif viruses produced by H9 cells. Equal amounts of viral proteins, (20 ng of p24, as measured by p24 antigen capture test) were loaded onto each slot of SDS-PAGE. Endogenous A3G and viral p24 CA proteins (upper and lower panels, respectively) were detected by using specific antibodies. Virus harvested from 293T cells transiently co-transfected with HIV-1 Δvif DNA and pcDNA3-A3G-MycHis was used as positive control (PC). B. 30 ng of p24 of HIV-1 wt and Δvif virions produced by H9 and SupT1 cells were loaded into the slots of SDS-gels. The presence of A3G and Vif proteins in those virus preparations was determined by using polyclonal anti-A3G and anti-Vif antibodies. C. Deamination of synthetic ss-deoxynucleotide substrate by virus-associated A3G. Equal amounts of HIV-1 wt and Δvif viruses (1.25 ng of p24) were added to the reactions containing increasing amounts of the substrate (ranging from 0.01 to 0.2 fmol), as indicated. S, an 80 nt-long substrate used for the deamination assay; P, a 40 nt-long product of the restriction reaction.

Table I.

A3G protein content in HIV-1wt vs HIV-1Δvif virions

| Virus | Exp. | p24 ng/slot |

A3G/slot, (OD) |

A3G(OD)/ ng of p24 |

A3G in HIV-1wt vs HIV-1Δvif, per ng p24, (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-1 wt | #1 | 58.58 | 98592 | 1683 | 21.60 |

| HIV-1 Δvif | 33.68 | 262441 | 7792 | ||

| HIV-1 wt | #2 | 58.58 | 27949 | 477 | 15.71 |

| HIV-1 Δvif | 33.68 | 102255 | 3036 | ||

| HIV-1 wt | #3 | 29.29 | 25501 | 871 | 15.04 |

| HIV-1 Δvif | 16.84 | 97458 | 5787 | ||

| HIV-1 wt | #4 | 29.29 | 6667 | 228 | 17.98 |

| HIV-1 Δvif | 16.84 | 21321 | 1266 | ||

| A3Gwtvs A3GΔ vif | 17.58 ± 2.96 | ||||

The deaminase activity associated with the wt and Vif-deficient viruses released from H9 cells correlates to the amounts of A3G molecules entrapped in the particles (Fig. 1C). These results are well correlated with our published data 35. However, calculation of the efficacy of the A3G enzymes packed in the wt and Δvif particles revealed that the deaminase activity of A3G in the wt particles is significantly lower than expected (Table II) and is only 6.42% of the deaminase activity in Δvif particles. Normalizing the virion-associated deaminase activity to A3G protein content indicates that the specific activity of wt HIV-1-associated A3G enzyme is 36.5% of the enzyme associated with the Δvif particles (6.42/17.58*100, see Tables I and II). A plausible explanation of these results is that Vif molecules associated with the HIV-1 wt particles inhibit the intrinsic deamination activity of A3G.

Table II.

Deaminase activity (DA) of A3G in HIV-1wt vs HIV-1Δvif virions Each reaction was loaded with equal amounts (1.25 ng of p24) of HIV-1wt or HIV-1Δvif purified virus.

| [S], fmol/reaction |

Deaminase activity (DA), [P]/([P]+[S]) |

DA in HIV-1wt vs HIV-1Δvif - % |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-1 wt | 0.02 | 0.0135 | 5.81 |

| HIV-1 Δvif | 0.2320 | ||

| HIV-1 wt | 0.05 | 0.0185 | 6.79 |

| HIV-1 Δvif | 0.2727 | ||

| HIV-1 wt | 0.2 | 0.0194 | 5.99 |

| HIV-1 Δvif | 0.3243 | ||

| HIV-1 wt | 0.5 | 0.0228 | 7.08 |

| HIV-1 Δvif | 0.3224 | ||

| A3Gwtvs A3GΔ vif | 6.42 ± 0.62 | ||

2. Inhibition of A3G deaminase activity by HIV-1 Vif

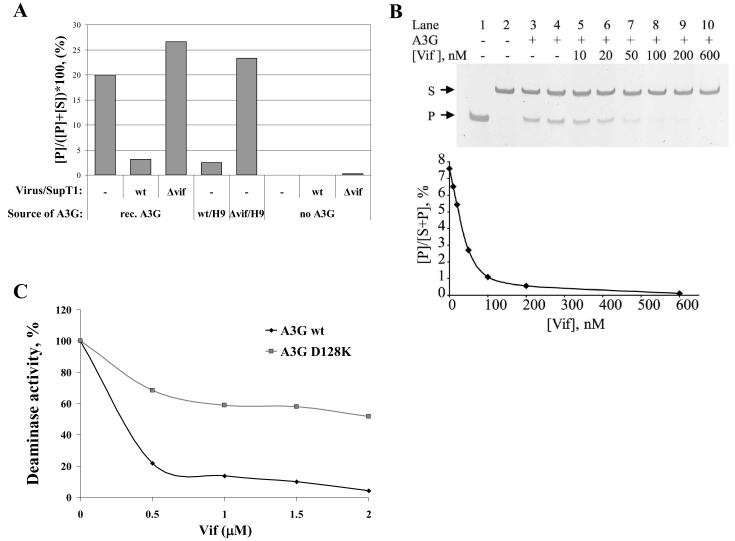

To determine whether Vif molecules associated with HIV-1 particles inhibit A3G activity, we performed exogenous reactions using purified recombinant A3G. A3G alone deaminated 20% of the dC in the oligonucleotide substrate. Adding particles released from wt HIV-1 infected Sup T1 cells, which contain Vif (see Fig. 1B) decreased A3G activity, while adding the same amount of Δvif particles to the reaction had no effect, or even slightly amplified the deaminase activity, probably because of increased concentration of proteins in the mixture (Fig. 2A). These results indicate that Vif molecules associated with HIV-1 are able to inhibit A3G activity in vitro.

Fig. 2. Inhibition of A3G activity by Vif.

A. Recombinant A3G protein (rec. A3G) (0.75 fmol) was mixed with wt HIV-1 or Δvif virus from SupT1 cells (2.5 ng of p24 per reaction). Reactions were carried out on 1 fmol of A3G oligonucleotide substrate. As negative controls, deamination reactions were loaded with viruses from SupT1 (no A3G). All reactions contained 2.5 ng of p24 (as measured by p24 CA antigen capture test). B. Purified A3G (0.35 fmol) was incubated with the ss-deoxy-oligonucleotide substrate in the presence of purified Vif for 15 min. Lane 1, positive control (dU containing oligonucleotide); Lane 2, negative control (no A3G); Lane 3, sample containing 10 μM BSA; Lane 4, sample containing the elution fraction of Ni-NTA purification from non Vif-expressing bacteria (amount equal to lane 10); Lanes 5-10, dose-dependent inhibition of A3G deamination by increasing Vif concentrations, as indicated. A graphic representation of the Vif-mediated inhibition is shown on the bottom. Values represent the average of triplicates; SD values were less than +/−0.8. C. Purified wt and D128K A3G enzymes (0.2 fmol) were incubated with purified Vif protein at indicated concentrations for 10 min at RT, followed by addition of 10 fmol ss-deoxy-oligonucleotide substrate for 30 min. The plot presents the relative deaminase activity, while 100 percent of activity was adjusted to deamination without Vif.

Next, we performed in-depth biochemical analysis of Vif-mediated inhibition of A3G enzymatic activity. To this end we expressed and purified recombinant Vif protein and examined A3G activity in the presence of Vif. The purification of recombinant His-tagged Vif from bacteria yielded an over 90% purified protein, as revealed by SDS-PAGE analysis and verified by Western blotting (not shown). Purified A3G was incubated with increasing amounts of purified Vif and the effect on A3G-mediated deamination levels of the ss-deoxyoligonucleotide substrate was measured. Figure 2B clearly shows that Vif inhibits A3G deaminase activity in a dose-dependent manner (lanes 5-10). An equal amount of an elution fraction from non Vif-expressing bacteria (lane 4) or 10 μM BSA (lane 3) used as controls did not inhibit A3G activity. The inhibitory effect exerted by Vif was observed at Vif concentrations ranging down to 10 nM.

In order to ensure that the Vif/A3G interaction is essential for efficient inhibition of A3G enzymatic activity, we compared Vif mediated dose-dependent inhibition of wt A3G and A3G D128K mutant, which is abortive for Vif binding 49; 51; 52; 53; 54. A3G D128K deaminase activity was only moderately inhibited in all Vif concentrations used (ranging from 0.5 μM to 2 μM), indicating that binding of Vif to A3G is essential for A3G inhibition (Figure 2C).

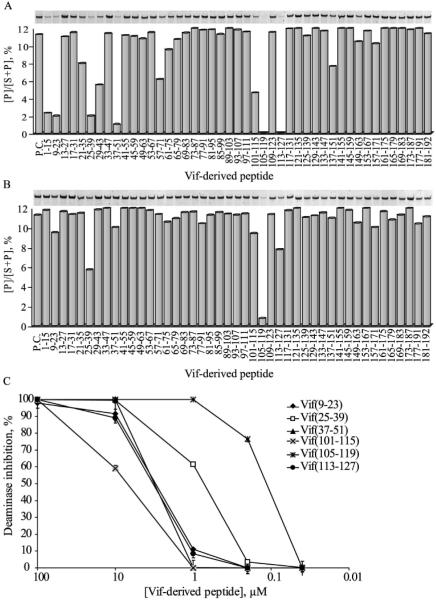

3. Identifying the Vif-derived domains which inhibit A3G deaminase

In order to identify the inhibitory domains in Vif, a battery of 15-mer 46 Vif-derived peptides (Table III) with 11aa overlaps covering the full-length protein was screened for the inhibition of A3G-mediated deamination. Peptides corresponding to sequences throughout the Vif protein exerted a vast inhibitory effect at a concentration of 100 μM (not shown). At a lower concentration of 10 μM, a distinct inhibitory pattern was observed by peptide sequences corresponding to Vif N-terminus (1-51aa) and to a central region (101-127aa), previously characterized as a novel zinc-binding domain 30; 55 (Fig. 3A). Specifically, six peptides inhibited the A3G deaminase activity at a lower concentration of 1 μM, mapping the inhibitory sequences to Vif9-23, Vif25-39 and Vif37-51 at the N-terminal region, and Vif101-115, Vif105-119 and Vif113-127 at the central region (Fig. 3B). These peptides were further analyzed for the inhibition of A3G activity at lower concentrations ranging down to 40 nM. As shown in Fig. 3C, the peptides Vif25-39 and especially Vif105-119, significantly reduced the A3G activity at 1 μM and 0.2 μM with an IC50 of approximately 0.6 μM and 0.1 μM, respectively. To exclude the possibility that the Vif-derived peptides decrease overall PCR efficiency, these experiments were verified by real-time PCR assays that showed no differential amplification rate of A3G reaction products with or without the Vif-derived peptides (data not shown).

Table III.

Vif-derived peptidesa

| NIH S.# | FROM | TO | PEPTIDE SEQUENCE | NIH S.# | FROM | TO | PEPTIDE SEQUENCE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6018 | 1 | 15 | MENRWQVMIVWQVDR | 6041 | 93 | 107 | RYSTQVDPDLADQLI |

| 6019 | 5 | 19 | WQVMIVWQVDRMRIR | 6042 | 97 | 111 | QVDPDLADQLIHLYY |

| 6020 | 9 | 23 | IVWQVDRMRIRTWKS | 6043 | 101 | 115 | DLADQLIHLYYFDCF |

| 6021 | 13 | 27 | VDRMRIRTWKSLVKH | 6044 | 105 | 119 | QLIHLYYFDCFSESA |

| 6022 | 17 | 31 | RIRTWKSLVKHHMYI | 6045 | 109 | 123 | LYYFDCFSESAIRNA |

| 6023 | 21 | 35 | WKSLVKHHMYISGKA | 6046 | 113 | 127 | DCFSESAIRNAILGH |

| 6024 | 25 | 39 | VKHHMYISGKAKGWF | 6047 | 117 | 131 | ESAIRNAILGHIVSP |

| 6025 | 29 | 43 | MYISGKAKGWFYRHH | 6048 | 121 | 135 | RNAILGHIVSPRCEY |

| 6026 | 33 | 47 | GKAKGWFYRHHYEST | 6049 | 125 | 139 | LGHIVSPRCEYQAGH |

| 6027 | 37 | 51 | GWFYRHHYESTHPRI | 6050 | 129 | 143 | VSPRCEYQAGHNKVG |

| 6028 | 41 | 55 | RHHYESTHPRISSEV | 6051 | 133 | 147 | CEYQAGHNKVGSLQY |

| 6029 | 45 | 59 | ESTHPRISSEVHIPL | 6052 | 137 | 151 | AGHNKVGSLQYLALA |

| 6030 | 49 | 63 | PRISSEVHIPLGDAR | 6053 | 141 | 155 | KVGSLQYLALAALIT |

| 6031 | 53 | 67 | SEVHIPLGDARLVIT | 6054 | 45 | 59 | QYLALAALITPKKI |

| 6032 | 57 | 71 | IPLGDARLVITTYWG | 6055 | 149 | 163 | ALAALITPKKIKPPL |

| 6033 | 61 | 75 | DARLVITTYWGLHTG | 6056 | 153 | 167 | LITPKKIKPPLPSVT |

| 6034 | 65 | 79 | VITTYWGLHTGERDW | 6057 | 157 | 171 | KKIKPPLPSVTKLTE |

| 6035 | 69 | 83 | YWGLHTGERDWHLGQ | 6058 | 161 | 175 | PPLPSVTKLTEDRWN |

| 6036 | 73 | 87 | HTGERDWHLGQGVSI | 6059 | 165 | 179 | SVTKLTEDRWNKPQK |

| 6037 | 77 | 91 | RDWHLGQGVSIEWRK | 060 | 169 | 183 | LTEDRWNKPQKTKGH |

| 6038 | 81 | 95 | LGQGVSIEWRKKRYS | 6061 | 173 | 187 | RWNKPQKTKGHRGSH |

| 6039 | 85 | 99 | VSIEWRKKRYSTQVD | 6062 | 177 | 191 | PQKTKGHRGSHTMNG |

| 6040 | 89 | 103 | WRKKRYSTQVDPDLA | 6063 | 181 | 192 | KGHRGSHTMNGH |

Fifteen-mer peptides derived from HIV-1 Vif (sequence accession: #AAZ14773) covering the full-length protein with 11aa overlaps.

Fig. 3. Inhibition of A3G deaminase activity by Vif-derived peptides.

Fifteen-mer Vif-derived peptides covering the complete Vif sequence were assessed for the inhibition of A3G. The standard deamination reaction was carried out in the presence of 10 μM (A) or 1 μM (B) of each peptide, or an RSV-derived peptide (P.C., positive control). PAGE analyses of the cleaved deamination products are shown above the charts. C. the effect of the Vif-derived peptide concentration on A3G mediated deamination. Values represent the average of triplicates; SD values were less than +/− 0.5 where not indicated.

4. Determining the mode of Vif-mediated inhibition of A3G enzyme

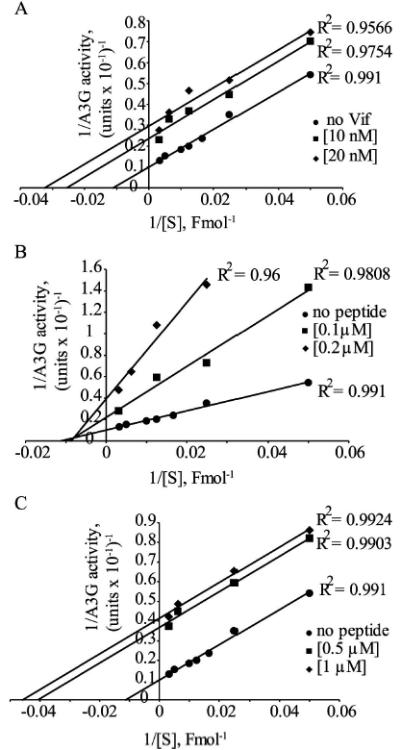

Next, we determined the mode of inhibition employed by Vif and the Vif-derived peptides corresponding to residues 25-39 and 105-119. A3G initial deamination rates were measured in the presence of 10 and 20 nM Vif (Fig. 4A), 0.1 and 0.2 μM Vif105-119 (Fig. 4B) or 0.5 and 1 μM Vif25-39 (Fig. 4C). The double-reciprocal plot of A3G inhibition by Vif and Vif25-39 reveals an uncompetitive inhibition mode, whereas Vif105-119 inhibits A3G in a mixed mode. Accordingly, the K’I values of Vif and Vif25-39 are approximately 8.7*10−9 M and 2.5*10−7 M, respectively. The K’I and KI values of Vif105-119 are approximately 9.2*10−8 M and 6.8*10−8 M, respectively.

Fig. 4. Determination of the Vif and Vif-derived peptides mode of inhibition.

Deamination of an ss-deoxyoligonucleotide as function of the substrate concentration in the presence of Vif (A) and the Vif-derived peptides Vif105-119 (B) and Vif25-39 (C) was determined and is shown by double-reciprocal (double-inverse) plot. The Vif and Vif-derived peptides concentrations used are indicated. Values represent the average of triplicates; SD values were less than +/−0.4.

DISCUSSION

Santa-Marta and colleagues 49; 50 demonstrated that HIV-1Vif inhibits A3G -mediated cytidine deamination without mediating protein degradation in bacteria. We therefore hypothesize that Vif molecules incorporated into newly assembled virions produced by restrictive cells directly inhibit the enzymatic activity of A3G during viral reverse-transcription in target cells. The present report provides evidence manifesting the potentiality of Vif as a deaminase inhibitor acting at a post entry phase in target cells.

The biological significance of Vif-activity in vivo has been implied before. Mehle and colleagues 34 reported that mutations of the conserved phosphorylation sites T96 and S144 in Vif impair viral replication without affecting the ability of these mutants to induce A3G degradation, suggesting that Vif plays additional role(s) beside inducing proteasomal degradation of A3G. Furthermore, the production of infectious HIV-1 is not dependent on the depletion of A3G from virus-producing HeLa cells 56; 57. In fact, wild-type virions produced in A3G-expressing 293T cells 43 or even in restrictive Hut78 cells 58 contain A3G protein despite Vif expression. Interaction between Vif and A3G molecules in virions was recently demonstrated by Yamashita and his co-workers 59. These findings are in agreement with our own data showing that infective HIV-1 particles produced in 293T cells expressing exogenous A3G, and in H9 cells expressing endogenous A3G, contain measurable levels of A3G 35. Other groups, however, reported undetectable levels of A3G in HIV-1 virions 32; 33; 60; 61. Finally, it was shown that reduced Vif incorporation into virions produced by chronically infected cells decreases its counteracting effects on A3G-mediated deamination 26. The reduced levels of Vif in these virions, however, are sufficient for maintaining viral infectivity 48.

Vif-proficient particles released from H9 cells contain 0.3 to 0.8 molecules of A3G per virion 35, while the exact number of virus-associated Vif molecules remains to be determined 47; 62; 63; 64. However, it could be larger than the number of A3G in the virion.

It was previously shown that virion encapsidation of a ubiquitination-resistant A3G mutant 65, Vif-binding-deficient D128K A3G 51; 52; 53; 54 or A3G fused to virion-targeting polypeptides derived from HIV-1 Vpr or Nef 66; 67, caused efficient antiviral effect despite the presence of Vif. It is plausible, however, that high stoichiometry of virion-associated A3G in these systems, which is well above the physiological levels, averted the Vif-mediated inhibition observed with endogenous A3G virion incorporation (Figure 2A).

By using a cell free system we showed that purified Vif inhibits A3G-mediated deamination of an ss-oligonucleotide substrate at sub-micromolar concentrations, with an IC50 of approximately 20 nM (Fig. 2). Moreover, Vif inhibits A3G-deamination in an uncompetitive manner (Fig. 4), suggesting that Vif affects the substrate-bound enzyme. As purified A3G and HIV-1 Vif proteins were used in these assays, we conclude that Vif directly inhibits the deamination activity mediated by A3G and no other molecules are required for this inhibition. Using an array of 15-mer synthetic Vif-derived peptides, we mapped the observed inhibition to two sequences corresponding to Vif25-39 and Vif105-119 (Fig. 3). Although large molar excess of Vif was required for A3G inhibition in vitro, it does not exclude the possibility that Vif plays a similar physiological role in virions and/or PICs at a post entry phase, because: (i) proteins purified from bacterial cells could have a much lower specific activity than proteins isolated from mammalian cells 35, and (ii) Vif is a structurally disordered protein difficult to maintain in solution 68; 69; 70. It can be argued that the observed inhibition of A3G is due to binding of Vif to the DNA substrate rather than to the enzyme 71. Our observation that Vif does not efficiently inhibit the A3G D128K deaminase activity supports the notion that the A3G/Vif interaction is essential for inhibition of A3G deamination 49. However, since Vif still inhibits 50% of the mutated A3G activity, we cannot exclude the possibility that under these conditions Vif binds the DNA substrate, or alternatively that Vif binds A3G in additional sites, inducing partial inhibition.

The most highly conserved sequences in Vif molecules of HIV-1, HIV-2 and SIVMAC are residues 21-30, 103-115 and 142-150 72. It was demonstrated that (i) deletions of these sequences reduced viral infectivity 73; (ii) substitutions of residues 38WFY40, 105QLI107, 111YF112 or C114 to Ala led to a 93%-98% reduction in the relative viral infectivity, rendering these residues indispensable for viral replication 74 ; (iii) the Vif W38A mutant produced a Δvif phenotype and T32Q mutation specifically affecting A3G-Vif interaction 75; (iv) complementation assays showed that the H108D/N and C114S mutations in Vif severely impaired Vif function without abolishing its incorporation into virions 47; 55, and (v) substitution of lysine residues for arginine showed that of the 16 lysine residues in Vif, only K22 or K26 are required for the productive infectious HIV-1 76. The Vif105-119 sequence resides within a characterized novel zinc-binding domain that encompasses the conserved sequence 108H-x5-C-x-17–18-C-x3–5-H139 30; 55; 77. This domain presumably coordinates one zinc ion by forming a symmetric loop using the four HCCH residues and is important for the interaction with Cullin5-E3 ligase. Comprised of a sequence containing the upstream HC residues of the loop, it is possible that the Vif105-119 peptide causes steric interference within A3G catalytic zinc-coordinating domains. Accordingly, it is possible that Vif uses its zinc-binding domain, or a part of it, to hinder the spatial structure of A3G catalytic domains. The Vif105-119 peptide inhibited A3G in a mixed mode, indicating that it binds either to the free or substrate-bound enzyme. On the other hand, the Vif25-39 peptide inhibited A3G deamination in an uncompetitive mode similar to the Vif protein, indicating that they bind directly to the enzyme–substrate complex. The mechanisms facilitating the inhibition of A3G-mediated deamination by Vif and its correlation to the above loss-of-function mutations, as well as the susceptibility of different N’ or C’-terminal active site A3G mutants to Vif-mediated inhibition, require further investigation.

As few as 1-2 A3G molecules incorporated into virion could be detrimental to HIV-1 infectivity 78, highlighting the importance of the putative Vif role in directly inhibiting virion-associated A3G. Importantly, this interplay between A3G mediated lethal hypermutation and the inhibitory effect of Vif during the replication of the viral genome could potently contribute to the genetic diversity of HIV-1 populations. The in vitro experiments presented here demonstrate the potentiality of Vif to control the deamination in the virion or in PICs, pointing at this Vif activity as the last line of defense. However, demonstrating this viral Vif function as crucial toward production of infectious virus would sustain the view of an A3G anti-viral mechanism that obliges its deaminase activity. Studying the existence of such a mechanism and estimating its significance to viral distribution in vivo is currently under way in our laboratory. These studies may yield new prospects for violating the suppression of A3G antiviral function by Vif.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells

Human T lymphoblastoid H9 and SupT1 cell lines, provided by the NIH AIDS Reagent Program (Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH, USA), were grown in RPMI 1640 medium (Biological Industries, Beit Haemek, Israel). The adherent 293T human embryonic kidney (HEK) cell line was kindly supplied by Dr. E. Bacharach (Tel Aviv University, Israel) and the TZM-bl cell line (contributed by Dr. John C. Kappes, Dr. Xiaoyun Wu and Tranzyme Inc.) was obtained through the NIH AIDS Reagent Program. The adherent cell lines were cultivated in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) as a sub confluent monolayer. RPMI 1640 and DMEM media were supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 U/ml streptomycin and 2 mM L-glutamine (Biological Industries, Beit Haemek, Israel).

Preparation of virus stocks

Wild type HIV-1 and HIV-1 Δvif were generated by transfection of 293T cells with pSVC21 plasmid containing full length HIV-1HXB2 or Δvif viral DNA 79; 80. Viruses were harvested 48 and 72 h post transfection and stored at − 80 °C until infection of cultured H9 and SupT1 cells.

Infection of cultured cells

Cultured human T lymphoblastoid H9 and SupT1 cells (5 × 106) were centrifuged for 5 min at 500 g, the supernatant was aspirated and cells were re-suspended in 30μl of medium containing wt or HIV-1 Δvif. Sup T1 cells were infected with wt or Vif-deficient virus at MOI 0.02, whereas H9 cells were infected with wt virus at MOI 0.02, or with Vif-deficient virus at MOI 1. Cells were infected by spinoculation at 1200 rpm for 100 min at room temperature. Following infection, cells were re-suspended in fresh RPMI medium supplied with 10% FCS, and incubated for additional 5-7 days at 37°C. Culture media were harvested daily starting at 5 d.p.i. and viruses were tittered by HIV-1 p24 antigen capture test. The harvests were further centrifuged to remove cells and cell debris (10,000 g for 10 min) and concentrated by ultracentrifuge for 1.5 h at 100,000 g through a 20% sucrose cushion. Pelleted viruses were re-suspended in small volume of phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and stored at −80°C until use.

HIV-1 titration

HIV-1 was titered by the MAGI assay, as described by Kimpton and Emerman 81.

Quantification of p24

HIV-1 p24 antigen capture assay kit (SAIC, AIDS Vaccine Program, Frederic, MD) was used to determine the amounts of p24 in the culture medium, according to the standards and instructions supplied by the manufacturers.

Expression and purification of A3G

A3G and A3G D128K containing a C-terminal His6 tag were expressed in 293T cells and purified as previously described35. Briefly, 293T cells were transfected with pcDNA-APO3G 32 or pcDNA-APO3G D128K 54. Cells (3×108) were harvested 48 h after transfection, washed three times in PBS and suspended in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 1 mM PMSF (Sigma-Aldrich), 10% (v/v) glycerol and 0.8% (v/v) NP-40), to a final concentration of 20,000 cells/μl. Following 10 min incubation in ice, cell debris and nuclei were pelleted by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 20 min. The soluble fraction was adjusted to 0.8 M NaCl and treated with 50 μg/ ml RNase A (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min at 37°C. Treated lysates were then added to 50 μl of nickel–nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) agarose beads (QIAGEN), mixed on an end-over-end shaker for 1 h at 4°C and loaded onto a standard chromatography column (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Following extensive washing with wash buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 0.3 M NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol) containing 30–50 mM imidazole, bound proteins were eluted seven times in wash buffer containing 120 mM imidazole. Protein samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE and stained with Imperial protein stain (Pierce Biotechnology). A3G concentration and purity was assessed by densitometry and scanning of stained gels, comparing band-intensity to that of a predetermined protein marker, and by a Bradford assay.

Expression and purification of Vif

The pD10-Vif-His6 plasmid 80, kindly provided by Dr. Dana Gabuzda (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA), was used to express an N-terminal His6 tagged HIV-1HXBII Vif protein in E. coli MC-1061. Vif was purified as previously described 80, with the following exceptions: after induction of Vif expression with 0.5 mM IPTG (Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 h at 37°C, bacteria were pelleted at 4,000 g for 15 min, washed with PBS and suspended in lysis buffer containing 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 8.0), 0.3 M NaCl, 25 μg/ml DNase, 1 mM PMSF (Sigma-Aldrich), 5 mM imidazole and 0.8% NP-40. Following sonication, insoluble cell debris and inclusion bodies were removed by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 20 min and the soluble fraction was subjected to Ni2+ affinity chromatography. Briefly, 4 ml of the sample corresponding to 200 ml bacterial culture were incubated with 1 ml 50% Ni-NTA slurry for 1 h at 4°C. Following extensive washing in wash buffer [50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 8.0), 0.3 M NaCl] containing 10-40 mM imidazole, Vif was eluted in the same buffer containing 110 mM imidazole. The eluted sample was dialyzed against A3G reaction buffer for 6 h at 4°C. The concentration and purity of the Vif preparation were assessed as described above for A3G.

Western blot

Transfected or infected cells were harvested, washed once in PBS, re-suspended in SDS-gel loading buffer and boiled for 10 min. Samples of 5×104 cells were analyzed by SDS - 12% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), followed by transfer of the proteins to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane. HIV-1 proteins were detected by using rabbit anti-Vif and monoclonal anti-Ca-p24 antibodies kindly provided by Dr. D. Gabuzda 73 and Dr. B. Chesebro 82, respectively. A3G protein was identified by rabbit polyclonal anti-A3G provided by Dr. J. Lingappa through the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program.

Deamination assay

Deaminase activity of purified enzyme and virion-associated A3G protein was examined as previously described 35. Briefly, A3G deamination reactions were performed in a total volume of 10 μl in 25 mM Tris, pH 7.0, and 0.01-1 fmol single-stranded (ss) deoxyoligonucleotide substrate (Integrated DNA Technologies) at 37°C. The reaction was terminated by heating to 95°C for 5 min. One μl of the reaction mixture was used for PCR amplification performed in 20 μl buffer S (Peqlab), using the following program: 1 cycle at 95°C for 3 min, followed by 30 cycles of annealing at 61°C for 30 s and denaturing at 94°C for 30 s. Aliquots of the PCR products (10 μl) were incubated with Eco147I restriction enzyme (Fermentas) for 1 h at 37°C. Completion of the restriction reaction was verified by using positive-control substrate containing CCU instead of CCC. Restriction-reaction products were loaded onto 14% gels and separated by PAGE. Gels were stained with SYBR gold nucleic acid stain (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) diluted 1:10,000 in 0.5 × Tris-Borate-EDTA buffer (TBE, pH 7.8), visualized by UV light (312 nm), captured by an Olympus C-5050 charge-coupled device (CCD) camera and analyzed by optical density (OD) scan using the TINA2.0 densitometry software (Raytest).

Assessment of A3G entrapped in virions was carried out with concentrated viruses (stocks of 3-5 pg of p24/μl) suspended in PBS containing Triton X-100 at final concentration of 0.1% (v/v) and 50 μg/ml RNase A (Sigma-Aldrich). Deamination reactions were incubated for 1 h at 37°C.

Synthetic oligonucleotides and peptides

The sequence of the 80-mer ss-deoxyoligonucleotide substrate used in the deamination assays is:

5′GGATTGGTTGGTTATTTGTTTAAGGAAGGTGGATTAAAGGCCCAATAAGGTGATGG AAGTTATGTTTGGTAGATTGATGG 3′ (A3G target site is underlined and the preferentially deaminated dC residue is bold-face-type). The positive control ss-deoxyoligonucleotide bears the same sequence, but has a dU instead of the target dC residue. The following primers were used for PCR amplification of the substrate and positive control oligonucleotides:

Forward 5′ GGATTGGTTGGTTATTTGTTTAAGGA3′;

Reverse 5′ CCATCAATCT ACCAAACATAACTTCCA 3′.

Vif-derived peptides were obtained through the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program as lyophilized powder and dissolved in water. Table 1 shows the amino acid sequences of the Vif-derived peptides.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was carried out in the Peter A. Krueger Laboratory with the generous support of Nancy and Lawrence Glick, and Pat and Marvin Weiss. We thank Dr. D. Gabuzda for providing the Vif-expressing vector and polyclonal Vif serum and Dr. K. Strebel for providing pcDNA-APO3G and pcDNA-APO3G D128K plasmids. The following reagents were obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH: HIV-1 Vif peptides from DAIDS, NIAID; anti-A3G polyclonal Abs from Dr. Jaisri Lingappa. This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant P01 GM091743, US–Israel Binational Science Foundation (BSF), and the Israel Ministry of Health. We thank Drs. Reuben S. Harris, Asaf Friedler and Akram Alian for constructive and helpful discussion and Mrs. S. Amir for editing this manuscript.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ss

single-stranded

- wt

wild type

- IC50

the half maximal inhibitory concentration

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- FCS

foetal calf serum

- MAGI

multinuclear activation of a galactosidase indicator

- d.p.i.

days post infection

- v/v

volume per volume

- PMSF

phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride

- Ni-NTA

nickel–nitrilotriacetic acid

- IPTG

isopropyl-1-β-D-galactopyranoside

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate – polyacryl amide gel electrophoresis

- PVDF

polyvinylidene fluoride

- TBE

Tris-Borate-EDTA

- OD

optical density

- nt

nucleotide

- RT

room temperature

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jarmuz A, Chester A, Bayliss J, Gisbourne J, Dunham I, Scott J, Navaratnam N. An anthropoid-specific locus of orphan C to U RNA-editing enzymes on chromosome 22. Genomics. 2002;79:285–96. doi: 10.1006/geno.2002.6718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wedekind JE, Dance GS, Sowden MP, Smith HC. Messenger RNA editing in mammals: new members of the APOBEC family seeking roles in the family business. Trends Genet. 2003;19:207–16. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(03)00054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conticello SG, Thomas CJ, Petersen-Mahrt SK, Neuberger MS. Evolution of the AID/APOBEC family of polynucleotide (deoxy)cytidine deaminases. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:367–77. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muramatsu M, Sankaranand VS, Anant S, Sugai M, Kinoshita K, Davidson NO, Honjo T. Specific expression of activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), a novel member of the RNA-editing deaminase family in germinal center B cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18470–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muramatsu M, Kinoshita K, Fagarasan S, Yamada S, Shinkai Y, Honjo T. Class switch recombination and hypermutation require activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), a potential RNA editing enzyme. Cell. 2000;102:553–63. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liao W, Hong SH, Chan BH, Rudolph FB, Clark SC, Chan L. APOBEC-2, a cardiac- and skeletal muscle-specific member of the cytidine deaminase supergene family. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;260:398–404. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Etard C, Roostalu U, Strahle U. Lack of Apobec2-related proteins causes a dystrophic muscle phenotype in zebrafish embryos. J Cell Biol. 2010;189:527–39. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200912125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sato Y, Probst HC, Tatsumi R, Ikeuchi Y, Neuberger MS, Rada C. Deficiency in APOBEC2 leads to a shift in muscle fiber type, diminished body mass, and myopathy. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:7111–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.052977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reizer J, Buskirk S, Bairoch A, Reizer A, Saier MH., Jr. A novel zinc-binding motif found in two ubiquitous deaminase families. Protein Sci. 1994;3:853–6. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560030515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iwatani Y, Takeuchi H, Strebel K, Levin JG. Biochemical activities of highly purified, catalytically active human APOBEC3G: correlation with antiviral effect. J Virol. 2006;80:5992–6002. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02680-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Langlois MA, Beale RC, Conticello SG, Neuberger MS. Mutational comparison of the single-domained APOBEC3C and double-domained APOBEC3F/G anti-retroviral cytidine deaminases provides insight into their DNA target site specificities. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:1913–23. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hache G, Liddament MT, Harris RS. The retroviral hypermutation specificity of APOBEC3F and APOBEC3G is governed by the C-terminal DNA cytosine deaminase domain. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:10920–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500382200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hakata Y, Landau NR. Reversed functional organization of mouse and human APOBEC3 cytidine deaminase domains. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:36624–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604980200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jonsson SR, Hache G, Stenglein MD, Fahrenkrug SC, Andresdottir V, Harris RS. Evolutionarily conserved and non-conserved retrovirus restriction activities of artiodactyl APOBEC3F proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:5683–94. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Navarro F, Bollman B, Chen H, Konig R, Yu Q, Chiles K, Landau NR. Complementary function of the two catalytic domains of APOBEC3G. Virology. 2005;333:374–86. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Newman EN, Holmes RK, Craig HM, Klein KC, Lingappa JR, Malim MH, Sheehy AM. Antiviral function of APOBEC3G can be dissociated from cytidine deaminase activity. Curr Biol. 2005;15:166–70. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.12.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Opi S, Takeuchi H, Kao S, Khan MA, Miyagi E, Goila-Gaur R, Iwatani Y, Levin JG, Strebel K. Monomeric APOBEC3G is catalytically active and has antiviral activity. J Virol. 2006;80:4673–82. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.10.4673-4682.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Esnault C, Heidmann O, Delebecque F, Dewannieux M, Ribet D, Hance AJ, Heidmann T, Schwartz O. APOBEC3G cytidine deaminase inhibits retrotransposition of endogenous retroviruses. Nature. 2005;433:430–3. doi: 10.1038/nature03238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Esnault C, Millet J, Schwartz O, Heidmann T. Dual inhibitory effects of APOBEC family proteins on retrotransposition of mammalian endogenous retroviruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:1522–31. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schumacher AJ, Nissley DV, Harris RS. APOBEC3G hypermutates genomic DNA and inhibits Ty1 retrotransposition in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9854–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501694102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chiu YL, Witkowska HE, Hall SC, Santiago M, Soros VB, Esnault C, Heidmann T, Greene WC. High-molecular-mass APOBEC3G complexes restrict Alu retrotransposition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:15588–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604524103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hulme AE, Bogerd HP, Cullen BR, Moran JV. Selective inhibition of Alu retrotransposition by APOBEC3G. Gene. 2007;390:199–205. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2006.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lecossier D, Bouchonnet F, Clavel F, Hance AJ. Hypermutation of HIV-1 DNA in the absence of the Vif protein. Science. 2003;300:1112. doi: 10.1126/science.1083338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mangeat B, Turelli P, Caron G, Friedli M, Perrin L, Trono D. Broad antiretroviral defence by human APOBEC3G through lethal editing of nascent reverse transcripts. Nature. 2003;424:99–103. doi: 10.1038/nature01709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mariani R, Chen D, Schrofelbauer B, Navarro F, Konig R, Bollman B, Munk C, Nymark-McMahon H, Landau NR. Species-specific exclusion of APOBEC3G from HIV-1 virions by Vif. Cell. 2003;114:21–31. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00515-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang H, Yang B, Pomerantz RJ, Zhang C, Arunachalam SC, Gao L. The cytidine deaminase CEM15 induces hypermutation in newly synthesized HIV-1 DNA. Nature. 2003;424:94–8. doi: 10.1038/nature01707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harris RS, Bishop KN, Sheehy AM, Craig HM, Petersen-Mahrt SK, Watt IN, Neuberger MS, Malim MH. DNA deamination mediates innate immunity to retroviral infection. Cell. 2003;113:803–9. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00423-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beale RC, Petersen-Mahrt SK, Watt IN, Harris RS, Rada C, Neuberger MS. Comparison of the differential context-dependence of DNA deamination by APOBEC enzymes: correlation with mutation spectra in vivo. J Mol Biol. 2004;337:585–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suspene R, Sommer P, Henry M, Ferris S, Guetard D, Pochet S, Chester A, Navaratnam N, Wain-Hobson S, Vartanian JP. APOBEC3G is a single-stranded DNA cytidine deaminase and functions independently of HIV reverse transcriptase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:2421–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luo K, Xiao Z, Ehrlich E, Yu Y, Liu B, Zheng S, Yu XF. Primate lentiviral virion infectivity factors are substrate receptors that assemble with cullin 5-E3 ligase through a HCCH motif to suppress APOBEC3G. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:11444–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502440102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Conticello SG, Harris RS, Neuberger MS. The Vif protein of HIV triggers degradation of the human antiretroviral DNA deaminase APOBEC3G. Curr Biol. 2003;13:2009–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kao S, Khan MA, Miyagi E, Plishka R, Buckler-White A, Strebel K. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vif protein reduces intracellular expression and inhibits packaging of APOBEC3G (CEM15), a cellular inhibitor of virus infectivity. J Virol. 2003;77:11398–407. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.21.11398-11407.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marin M, Rose KM, Kozak SL, Kabat D. HIV-1 Vif protein binds the editing enzyme APOBEC3G and induces its degradation. Nat Med. 2003;9:1398–403. doi: 10.1038/nm946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mehle A, Strack B, Ancuta P, Zhang C, McPike M, Gabuzda D. Vif overcomes the innate antiviral activity of APOBEC3G by promoting its degradation in the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:7792–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313093200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nowarski R, Britan-Rosich E, Shiloach T, Kotler M. Hypermutation by intersegmental transfer of APOBEC3G cytidine deaminase. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:1059–66. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Borman AM, Quillent C, Charneau P, Kean KM, Clavel F. A highly defective HIV-1 group O provirus: evidence for the role of local sequence determinants in G-->A hypermutation during negative-strand viral DNA synthesis. Virology. 1995;208:601–9. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gifford RJ, Rhee SY, Eriksson N, Liu TF, Kiuchi M, Das AK, Shafer RW. Sequence editing by Apolipoprotein B RNA-editing catalytic component [corrected] and epidemiological surveillance of transmitted HIV-1 drug resistance. Aids. 2008;22:717–25. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f5e07a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Janini M, Rogers M, Birx DR, McCutchan FE. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 DNA sequences genetically damaged by hypermutation are often abundant in patient peripheral blood mononuclear cells and may be generated during near-simultaneous infection and activation of CD4(+) T cells. J Virol. 2001;75:7973–86. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.17.7973-7986.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vartanian JP, Meyerhans A, Asjo B, Wain-Hobson S. Selection, recombination, and G----A hypermutation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genomes. J Virol. 1991;65:1779–88. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.4.1779-1788.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rangel HR, Garzaro D, Rodriguez AK, Ramirez AH, Ameli G, Del Rosario Gutierrez C, Pujol FH. Deletion, insertion and stop codon mutations in vif genes of HIV-1 infecting slow progressor patients. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2009;3:531–8. doi: 10.3855/jidc.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sato K, Izumi T, Misawa N, Kobayashi T, Yamashita Y, Ohmichi M, Ito M, Takaori-Kondo A, Koyanagi Y. Remarkable Lethal G-to-A Mutations in vif-Proficient HIV-1 Provirus by Individual APOBEC3 Proteins in Humanized Mice. J Virol. 2010;84:9546–56. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00823-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim EY, Bhattacharya T, Kunstman K, Swantek P, Koning FA, Malim MH, Wolinsky SM. Human APOBEC3G-mediated editing can promote HIV-1 sequence diversification and accelerate adaptation to selective pressure. J Virol. 2010 doi: 10.1128/JVI.01223-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sadler HA, Stenglein MD, Harris RS, Mansky LM. APOBEC3G contributes to HIV-1 variation through sublethal mutagenesis. J Virol. 2010;84:7396–404. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00056-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hultquist JF, Harris RS. Leveraging APOBEC3 proteins to alter the HIV mutation rate and combat AIDS. Future Virol. 2009;4:605. doi: 10.2217/fvl.09.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mulder LC, Harari A, Simon V. Cytidine deamination induced HIV-1 drug resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:5501–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710190105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pillai SK, Wong JK, Barbour JD. Turning up the volume on mutational pressure: is more of a good thing always better? (A case study of HIV-1 Vif and APOBEC3) Retrovirology. 2008;5:26. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-5-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Camaur D, Trono D. Characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vif particle incorporation. J Virol. 1996;70:6106–11. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.6106-6111.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kao S, Akari H, Khan MA, Dettenhofer M, Yu XF, Strebel K. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vif is efficiently packaged into virions during productive but not chronic infection. J Virol. 2003;77:1131–40. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.2.1131-1140.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Santa-Marta M, da Silva FA, Fonseca AM, Goncalves J. HIV-1 Vif can directly inhibit apolipoprotein B mRNA-editing enzyme catalytic polypeptide-like 3G-mediated cytidine deamination by using a single amino acid interaction and without protein degradation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:8765–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409309200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Santa-Marta M, da Silva F. Aires, Fonseca AM, Rato S, Goncalves J. HIV-1 Vif protein blocks the cytidine deaminase activity of B-cell specific AID in E. coli by a similar mechanism of action. Mol Immunol. 2007;44:583–90. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bogerd HP, Doehle BP, Wiegand HL, Cullen BR. A single amino acid difference in the host APOBEC3G protein controls the primate species specificity of HIV type 1 virion infectivity factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:3770–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307713101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mangeat B, Turelli P, Liao S, Trono D. A single amino acid determinant governs the species-specific sensitivity of APOBEC3G to Vif action. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:14481–3. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400060200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schrofelbauer B, Chen D, Landau NR. A single amino acid of APOBEC3G controls its species-specific interaction with virion infectivity factor (Vif) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:3927–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307132101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xu H, Svarovskaia ES, Barr R, Zhang Y, Khan MA, Strebel K, Pathak VK. A single amino acid substitution in human APOBEC3G antiretroviral enzyme confers resistance to HIV-1 virion infectivity factor-induced depletion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:5652–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400830101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mehle A, Thomas ER, Rajendran KS, Gabuzda D. A zinc-binding region in Vif binds Cul5 and determines cullin selection. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:17259–65. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602413200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kao S, Goila-Gaur R, Miyagi E, Khan MA, Opi S, Takeuchi H, Strebel K. Production of infectious virus and degradation of APOBEC3G are separable functional properties of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vif. Virology. 2007;369:329–39. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kao S, Miyagi E, Khan MA, Takeuchi H, Opi S, Goila-Gaur R, Strebel K. Production of infectious human immunodeficiency virus type 1 does not require depletion of APOBEC3G from virus-producing cells. Retrovirology. 2004;1:27. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-1-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Carr JM, Davis AJ, Coolen C, Cheney K, Burrell CJ, Li P. Vif-deficient HIV reverse transcription complexes (RTCs) are subject to structural changes and mutation of RTC-associated reverse transcription products. Virology. 2006;351:80–91. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yamashita T, Nomaguchi M, Miyake A, Uchiyama T, Adachi A. Status of APOBEC3G/F in cells and progeny virions modulated by Vif determines HIV-1 infectivity. Microbes Infect. 2010;12:166–71. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stopak K, de Noronha C, Yonemoto W, Greene WC. HIV-1 Vif blocks the antiviral activity of APOBEC3G by impairing both its translation and intracellular stability. Mol Cell. 2003;12:591–601. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00353-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yu X, Yu Y, Liu B, Luo K, Kong W, Mao P, Yu XF. Induction of APOBEC3G ubiquitination and degradation by an HIV-1 Vif-Cul5-SCF complex. Science. 2003;302:1056–60. doi: 10.1126/science.1089591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu H, Wu X, Newman M, Shaw GM, Hahn BH, Kappes JC. The Vif protein of human and simian immunodeficiency viruses is packaged into virions and associates with viral core structures. J Virol. 1995;69:7630–8. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.7630-7638.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dettenhofer M, Yu XF. Highly purified human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reveals a virtual absence of Vif in virions. J Virol. 1999;73:1460–7. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.2.1460-1467.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Simon JH, Miller DL, Fouchier RA, Malim MH. Virion incorporation of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 Vif is determined by intracellular expression level and may not be necessary for function. Virology. 1998;248:182–7. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Iwatani Y, Chan DS, Liu L, Yoshii H, Shibata J, Yamamoto N, Levin JG, Gronenborn AM, Sugiura W. HIV-1 Vif-mediated ubiquitination/degradation of APOBEC3G involves four critical lysine residues in its C-terminal domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:19539–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906652106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Green LA, Liu Y, He JJ. Inhibition of HIV-1 infection and replication by enhancing viral incorporation of innate anti-HIV-1 protein A3G: a non-pathogenic Nef mutant-based anti-HIV strategy. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:13363–72. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806631200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ao Z, Yu Z, Wang L, Zheng Y, Yao X. Vpr14-88-Apobec3G fusion protein is efficiently incorporated into Vif-positive HIV-1 particles and inhibits viral infection. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1995. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reingewertz TH, Benyamini H, Lebendiker M, Shalev DE, Friedler A. The C-terminal domain of the HIV-1 Vif protein is natively unfolded in its unbound state. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2009;22:281–7. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzp004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Reingewertz TH, Shalev DE, Friedler A. Structural disorder in the HIV-1 Vif protein and interaction-dependent gain of structure. Protein Pept Lett. 2010;17:988–98. doi: 10.2174/092986610791498876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Auclair JR, Green KM, Shandilya S, Evans JE, Somasundaran M, Schiffer CA. Mass spectrometry analysis of HIV-1 Vif reveals an increase in ordered structure upon oligomerization in regions necessary for viral infectivity. Proteins. 2007;69:270–84. doi: 10.1002/prot.21471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bernacchi S, Henriet S, Dumas P, Paillart JC, Marquet R. RNA and DNA binding properties of HIV-1 Vif protein: a fluorescence study. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:26361–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703122200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Oberste MS, Gonda MA. Conservation of amino-acid sequence motifs in lentivirus Vif proteins. Virus Genes. 1992;6:95–102. doi: 10.1007/BF01703760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Goncalves J, Jallepalli P, Gabuzda DH. Subcellular localization of the Vif protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1994;68:704–12. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.2.704-712.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Simon JH, Sheehy AM, Carpenter EA, Fouchier RA, Malim MH. Mutational analysis of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vif protein. J Virol. 1999;73:2675–81. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.2675-2681.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tian C, Yu X, Zhang W, Wang T, Xu R, Yu XF. Differential requirement for conserved tryptophans in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vif for the selective suppression of APOBEC3G and APOBEC3F. J Virol. 2006;80:3112–5. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.6.3112-3115.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Khamsri B, Fujita M, Kamada K, Piroozmand A, Yamashita T, Uchiyama T, Adachi A. Effects of lysine to arginine mutations in HIV-1 Vif on its expression and viral infectivity. Int J Mol Med. 2006;18:679–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Xiao Z, Ehrlich E, Yu Y, Luo K, Wang T, Tian C, Yu XF. Assembly of HIV-1 Vif-Cul5 E3 ubiquitin ligase through a novel zinc-binding domain-stabilized hydrophobic interface in Vif. Virology. 2006;349:290–9. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Browne EP, Allers C, Landau NR. Restriction of HIV-1 by APOBEC3G is cytidine deaminase-dependent. Virology. 2009;387:313–21. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ratner L, Haseltine W, Patarca R, Livak KJ, Starcich B, Josephs SF, Doran ER, Rafalski JA, Whitehorn EA, Baumeister K, et al. Complete nucleotide sequence of the AIDS virus, HTLV-III. Nature. 1985;313:277–84. doi: 10.1038/313277a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yang X, Goncalves J, Gabuzda D. Phosphorylation of Vif and its role in HIV-1 replication. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:10121–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.17.10121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kimpton J, Emerman M. Detection of replication-competent and pseudotyped human immunodeficiency virus with a sensitive cell line on the basis of activation of an integrated beta-galactosidase gene. J Virol. 1992;66:2232–9. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.4.2232-2239.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chesebro B, Wehrly K, Nishio J, Perryman S. Macrophage-tropic human immunodeficiency virus isolates from different patients exhibit unusual V3 envelope sequence homogeneity in comparison with T-cell-tropic isolates: definition of critical amino acids involved in cell tropism. J Virol. 1992;66:6547–54. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.11.6547-6554.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]