Abstract

The Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) is an enveloped virus, constituted by 2 monomeric RNA molecules which encode for 15 proteins. Among these, are the structural proteins that are translated as the Gag polyprotein. In order to become infectious, HIV must undergo a maturation process mediated by the proteolytic cleavage of Gag to give rise to the isolated structural proteins matrix (MA), capsid (CA), nucleocapsid (NC) as well as p6 and the spacer peptides SP1 and SP2. Upon maturation, the N-terminal 13 residues from CA fold into a β-hairpin, which is stabilized mainly by a salt bridge between Pro1 and Asp51. Previous reports have shown that non-formation of the salt bridge, which potentially disrupts proper β-hairpin arrangement, generates non-infectious virus or aberrant cores. To date, however, there is no consensus on the role of the β-hairpin. In order to shed light in this subject, we have generated mutations in the hairpin region to examine what features would be crucial for the β-hairpin’s role in retroviral mature core formation. These features include the importance of the proline at the N-terminus, the amino acid sequence, and the physical structure of the β-hairpin itself. The presented experiments provide biochemical evidence that β-hairpin formation plays an important role in regard to CA protein conformation required to support proper mature core arrangement. Hydrogen/deuterium exchange and in vitro assembly reactions illustrated the importance of the β-hairpin structure, its dynamics, and its influence on the orientation of helix 1 for the assembly of the mature CA lattice.

Keywords: retroviral assembly, HIV-1 capsid protein, β-hairpin formation, in vitro assembly of HIV capsid, hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry

Introduction

Human Immunodeficiency Virus type 1 (HIV-1) enveloped viral particles bud from infected cells as immature virions composed of approximately 5000 radially arranged copies of the 55 kDa gag polyprotein.1 The gag polyprotein is composed of six distinct domains with matrix (MA) at the N-terminus followed by capsid (CA), spacer peptide 1 (SP1), nucleocapsid (NC), spacer peptide 2 (SP2), and p6 at the C-terminus. The N-terminus of gag is myristoylated and is anchored to the viral envelope of budding virions with the C-terminus of gag positioned towards the center of the particle (Figure 1b). While the MA and NC domains do not display any organized quaternary structure in the immature virion, tomographic reconstructions suggest that the CA forms a discontinuous, broken hexameric lattice.2,3

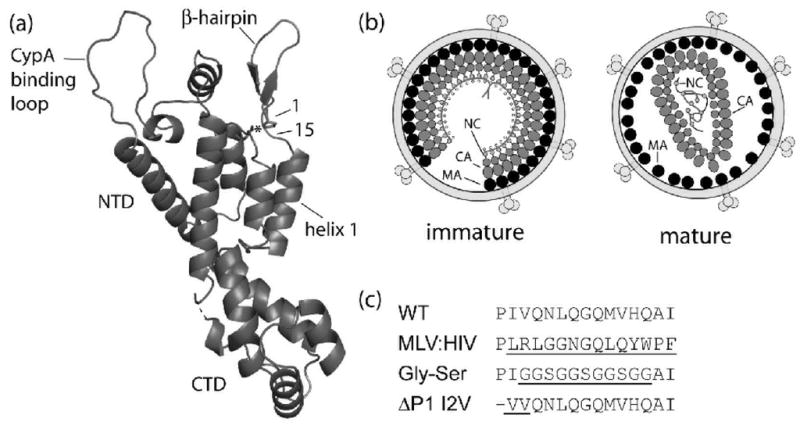

Figure 1.

Schematics of HIV-1 capsid protein (CA), virions and inserted hairpin mutations. (a) Cartoon representation of the mature HIV-1 CA protein monomer. Substituions generated for this work are confined between amino acid numbers 1 through 15; Pro1 and Asp51 are shown in stick form with an asterisk to denote the Pro1-Asp51 hydrogen bond. The relative location of the two structural domains (NTD and CTD), the β-hairpin, and the CypA binding loop are also depicted. (b) Cartoons of immature and mature HIV-1 virions showing the Gag polyprotein arranged radially in immature virions with the MA attached to the interior of the viral membrane with CA and NC extended towards the center of the virion. Following maturation, MA remains attached to the viral membrane while CA has collapsed to form the condensed, conical core encapsidating the viral RNA-NC complex. (c) Amino acid substitutions in the β-hairpin region of HIV capsid protein and their abbreviations with mutated regions underlined including wild-type (WT) CA protein sequence, grafted MLV β-hairpin (MLV:HIV), Glycine-Serine (Gly-Ser) replacement of the β-hairpin, and the deletion of the N-terminal proline, with substitution of the isoleucine to a valine, a conserved substitution among other HIV strains, at position 2 (ΔP1 I2V). (Panels a and b adapted from Ganser-Pornillos, et al.41)

To become infectious, HIV virions must undergo a maturation process following budding. This process is mediated by the viral protease and results in a pronounced morphological change in the virion, as ~2,500 CA monomers rearrange into a conical, centralized core. The viral protease cleaves the gag polyprotein into the individual structural and spacer domains described above. The separation of the C-terminus of CA from SP1 is believed to free it from a postulated SP1 α-helical bundle. This then allows the rearrangement of the C-terminal domain (CTD) of CA into its mature position to form an intrahexamer, intermolecular interaction with an adjacent N-terminal domain (NTD).4–6 While the N-terminal 13 residues of CA are extended in the immature form and during maturation, these residues refold into a β-hairpin following the completion of Gag processing.7–10 The resulting infectious HIV-1 capsids are organized as fullerene cones based on a hexameric lattice encapsidating the NC-RNA complex (Figure 1b).1,11–14

The β-hairpin structure is maintained by a salt bridge between the N-terminal proline residue 1 and the aspartate at position 51 and further strengthened by a hydrogen bonding network around and within the hairpin (Figure 1a).6,10,15 Mutational analyses suggest that the salt bridge is essential for proper core assembly and viral infectivity.9,16–18 Recent high resolution crystal structures of the hexameric lattice show no evidence for any intersubunit interactions that include the β-hairpin.6 Although it appears that the formation of the N-terminal β-hairpin is central to maturation, the molecular basis for this requirement remains unclear.

To address the role the salt bridge, the amino acid sequence, and the β-hairpin structure play in mature core formation, we generated several substitutions in the β-hairpin region of HIV-1 capsid protein. The mutants examined included a deletion of the N-terminal proline to preclude the salt bridge formation, introduction of a flexible glycine-serine linker in lieu of wild-type residues 3–13 and the grafting of the MLV hairpin sequence (residues 2–15) onto the HIV-1 capsid protein sequence (Figure 1c). In vitro assembly reactions, hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry and in vivo studies were able to shed light on the role of the hairpin structure on retroviral assembly. Through these experiments, we show that mutations that inhibit or strain β-hairpin formation prevent in vitro assembly while the insertion of the MLV β-hairpin sequence enhanced assembly. Additionally, the MLV β-hairpin was found to stabilize the CA assembly and modulate the orientation/stability of helix 1 in CA monomers, both of which may strengthen and/or facilitate the formation of the mature CA lattice. We also propose that the β-hairpin modulates the orientation of helix 1, which is integral to the assembly of the hexameric lattice.

Results

CA protein secondary structure and stability of β-hairpin mutants

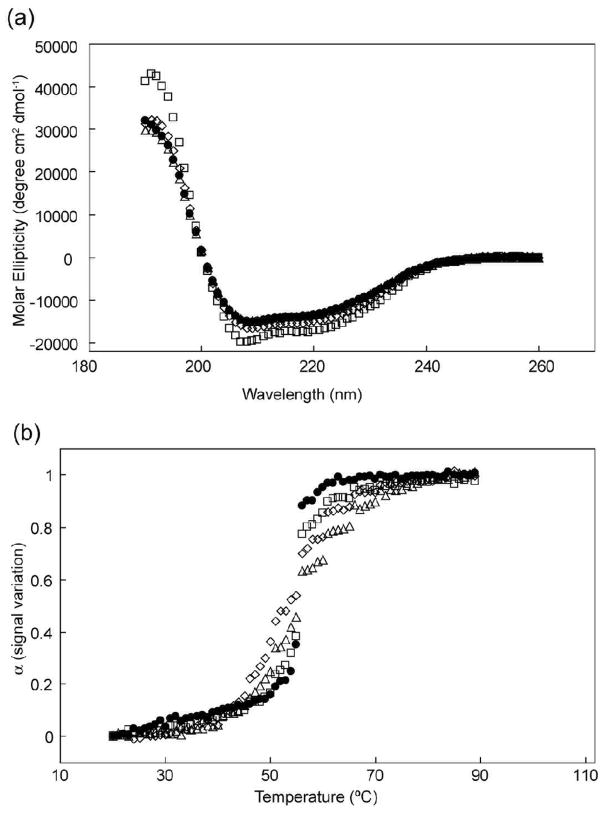

Amino acid substitutions (Figure 1c) were generated in the hairpin region of the HIV CA protein to investigate the role of the N-terminal β-hairpin on mature core formation. These mutations included the deletion of the N-terminal proline to abolish the formation of the Pro1-Asp51 salt bridge, insertion of a glycine-serine loop in positions 3–13 (GGSGGSGGSGG) to increase the flexibility of the β-hairpin region, and replacement of the WT β-hairpin sequence with that from MLV, a structurally similar virus. In the case of the Pro1 deletion, an additional mutation (I2V) was inserted in order to result in the trimming of the initiating methionine. The extent of conformational disturbances induced by these mutations on CA monomer secondary structure and stability was monitored by circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy. Compared to wild type, the hairpin mutations did not dramatically alter the secondary structure indicating that the proteins maintained the predominantly helical content associated with HIV-1 CA (Figure 2). All four proteins also displayed similar melting temperatures, of approximately 55 °C, suggesting similar thermal stability across the mutants (Figure 2b). However, small variations in the melting curves of the CA proteins indicate that subtle structural variations are likely present. ΔPro1 I2V and Gly-Ser showed less cooperative unfolding in the melting experiments compared to wild type. This suggests that deletion of the N-terminal proline or the substitution of the β-hairpin with a flexible loop disrupted the formation of the β-hairpin.

Figure 2.

Secondary structure analysis and melting curves of capsid protein mutants. (a) Circular Dichroism spectra of (●) WT, (△) ΔP1 I2V, (◇) Gly-Ser and (□) MLV:HIV. (b) Melting curves of (●) WT, Tm=55.2 °C, (△) ΔP1 I2V, Tm=55.1 °C, (◇) Gly-Ser, Tm=52.8 °C, and (□) MLV:HIV, Tm=54.8 °C.

Introduction of mutations in the hairpin region of HIV capsid protein alters assembly

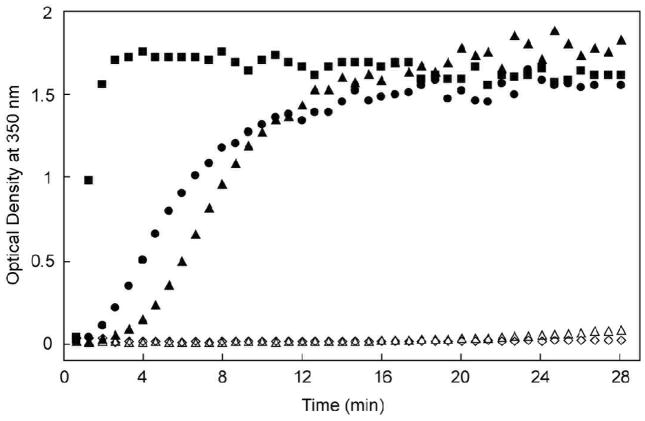

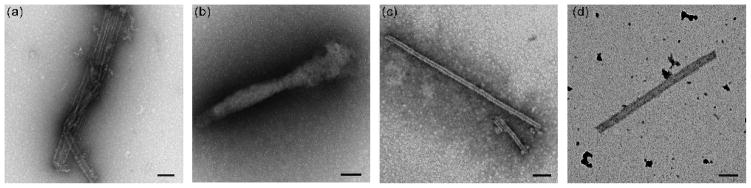

The in vitro assembly of WT CA protein can be triggered by the addition of NaCl9,12,14,19–23 and the kinetics of this assembly process may be monitored by an associated time-dependent increase in turbidity.23,24 This approach was employed to investigate the assembly activity of the HIV-1 CA hairpin mutants. Invariably, each mutation altered the observed assembly dynamics. Deletion of the N-terminal proline (ΔPro1 I2V) inhibited assembly, requiring an increase in protein concentration in order to observe an increase in turbidity (80 μM vs. 32 μM for WT), while the substitution of the β-hairpin structure with a flexible glycine-serine loop prevented assembly even at elevated concentrations (162 μM, Figure 3). In marked contrast, grafting the MLV hairpin sequence to the HIV CA protein significantly enhanced the rate of assembly compared to WT. The assembled structures of WT CA, ΔPro1 I2V and MLV:HIV were visualized by electron microscopy (Figure 4a–c). Both WT and the MLV:HIV fusion construct showed predominantly ordered tubular structures, with diameters ranging from 30 to 50 nm (Figure 4a, c). Deletion of the N-terminal proline resulted in the formation of amorphous aggregates at increased protein concentrations (Figure 4b). The Gly-Ser mutant is assembly deficient; no conditions were found where the mutant would assemble into WT-like tubes. As the Gly-Ser mutant retains the WT hairpin length and Pro1, these results suggest that the proline at N-terminus of CA is necessary, but not sufficient to support proper mature lattice formation.

Figure 3.

Assembly reactions of wild-type and β-hairpin variants. Samples were analyzed at the noted protein concentrations: (●) WT, 32 μM, (■) MLV:HIV, 32 μM, (△) ΔPro1 I2V, 40 μM, (▲) ΔPro1 I2V, 80 μM, (◇) Gly-Ser, 162 μM.

Figure 4.

Electron micrographs of the products of selected assembly reactions. (a) WT capsid protein, (b) ΔP1 I2V, (c) MLV:HIV, (d) MLV:HIV and WT mixed assembly. WT was assembled at 400 μM in the presence of 1 M NaCl. ΔP1 I2V (80μM) and MLV:HIV (32 μM) samples were assembled in the presence of 1.95 M NaCl. For the mixed assembly, 14 μM MLV:HIV and 14 μM WT were co-assembled in 1.95 M NaCl. Grids were stained with 1% uranyl acetate. Scale bars = 100 nm.

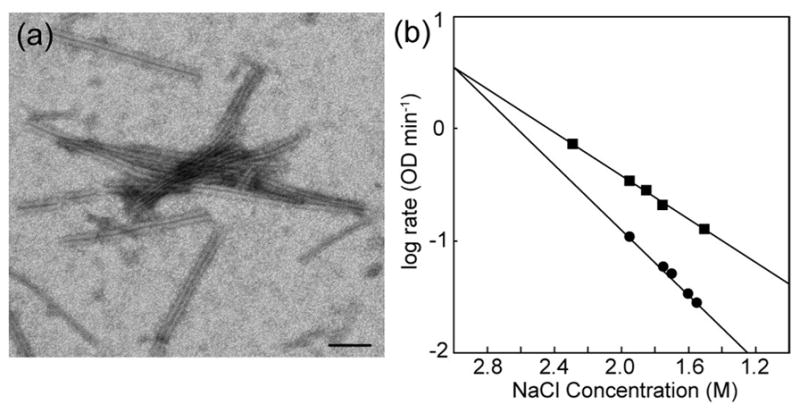

In vitro assembly reactions of HIV CA display a lag phase followed by a sigmoidal increase in rate, characteristic of a nucleation-limited reaction. The MLV:HIV CA fusion protein displayed an enhanced rate of assembly as compared to WT, with significant shortening of the lag phase (40 seconds vs. 60 second for WT) at a protein concentration of 32 μM, which suggests that the nucleation step in the fusion construct is likely more efficient (Figure 3). Upon purification of the MLV:HIV fusion construct, approximately half of the protein was found to precipitate in phosphate buffer in the absence of NaCl. Examination of the precipitate by electron microscopy revealed tubular structures, identical to those resulting from assembly reactions at lower protein concentrations in the presence of NaCl (Figure 5a). Based on the studies from Douglas et al., the addition of sodium chloride is necessary to shield the N-terminal charges and thus prevent charge-charge repulsion that would otherwise inhibit CA in vitro assembly.24 We therefore carried out assembly reactions of both the MLV:HIV fusion construct and WT CA in different NaCl concentrations. When the log of the rate of assembly is plotted versus NaCl concentration for WT and fusion protein, the slopes of the linear fits are not parallel, suggesting different shielding needs (Figure 5b). The rates of assembly for the two proteins do, however, converge at high salt concentration where shielding is most effective, suggesting the difference in assembly rate is due to electrostatic interactions.24,25

Figure 5.

Dependence of WT HIV and MLV:HIV assembly on NaCl. (a) A representative micrograph of MLV:HIV assembly in the absence of NaCl. Scale bar = 100 nm. (b) Assembly reactions were performed for HIV WT CA (●) or MLV:HIV CA (■) in different salt concentrations, ranging from 1.5 to 2.3 M NaCl. The rate of assembly of each reaction was determined by fitting the log phase of the assembly. Resulting values showed a varied reliance on salt between the proteins.

While the structures formed upon polymerization of WT and MLV:HIV CA appear to be morphologically similar in nature, we could not discount the possibility that the hairpin graft affected the protein-protein interaction interfaces necessary for assembly of the WT tubes. To assay for such a variation, WT and MLV:HIV were co-assembled in vitro. Nucleation-limited reactions display a non-linear dependence of the rate on protein concentration. For example, doubling the concentration of wild type CA results in a roughly ten-fold increase in the rate of in vitro assembly. If WT and the MLV:HIV fusion proteins are incapable of co-assembly and equimolar amounts are mixed, the assembly rate would be expected to correspond to the sum of the contributions from the individual proteins. On the other hand, if the proteins are able to co-assemble, the rate of assembly would increase to a rate approximately equal to the sum of their respective concentrations. Assembly reactions of either the WT or the MLV:HIV fusion protein alone at 14 μM displayed little assembly whereas a mixture containing 14 μM of each protein displayed significant assembly (Figure 6a). This result strongly suggests that the two proteins are capable of interacting during the rate limiting step of polymerization, as no assembly would otherwise be observed if they did not interact. Furthermore, the rate of assembly of the equimolar mixture of both proteins is intermediate between that observed for the wild type protein and MLV:HIV fusion proteins at 28 μM, suggesting that each species retains its intrinsic assembly properties in the mixed assembly reaction. Electron microscopic images of the products from the mixed assembly reactions demonstrated that tubes similar to those produced with only WT CA or the MLV:HIV fusion are formed (Figure 4d). This indicates that the product of assembly is very similar whether WT CA, MLV:HIV, or mixtures of the two proteins are used in the assembly reaction.

Figure 6.

Co-assembly of wild-type and MLV:HIV capsid protein and ESI-MS analysis of co-assembly products. (a) Assembly reactions of (●) WT CA at 28 μM, (○) WT CA at 14 μM, (■) MLV:HIV at 28 μM, (□) MLV:HIV at 14 μM, and (✕) mixed assembly of MLV:HIV and WT CA, both at 14 μM. All assemblies were performed in 1.95 M NaCl. (b) The charge state distribution (charges labeled) from the mass spectrum of the MLV:HIV and WT CA co-assembly reaction products shows equivalent distribution of the WT CA and MLV:HIV fusion proteins. The inset shows the observed m/z for the 27+ charge state where m/z 949.20 corresponds to [WT CA]27+ and m/z 951.94 corresponds to [MLV:HIV]27+.

To verify that both WT CA and MLV:HIV fusion proteins were incorporated into the products of the co-assembly, the tubes were pelleted, separated from the supernatant and analyzed by electrospray time-of-flight mass spectrometry (ESI-TOF MS). In the mass spectrum, a doublet was observed in the charge state envelope with signals corresponding to each protein being present at approximately a 1:1 ratio (Figure 6b). While not strictly quantitative, the ionization efficiency of both WT CA and MLV:HIV CA proteins are expected to be very similar owing to the high sequence similarity between the two forms. Therefore, the mass spectrum may provide a rough measure of the relative extent of incorporation of each protein in the assembled tubes. Deconvolution of the charge state distributions yielded masses corresponding to both the calculated masses of WT and MLV:HIV CA. Although not purely quantitative, this data indicates that both the WT and MLV:HIV fusion proteins are assembled into tubes at roughly equal efficiencies under mixed assembly conditions.

As heteropolymers of WT and MLV:HIV fusion proteins may be formed under typical assembly conditions, specific inter- and intramolecular interactions crucial to assembly are not likely to involve the β-hairpin. This suggests that the increased assembly kinetics observed for the MLV:HIV fusion protein is a result of structural modulation beyond the β-hairpin region.

H/D exchange Mass Spectrometry (HDX MS) identifies regions of structural/stability variation

While the β-hairpin does not appear to be involved in any intermolecular interactions in the mature CA lattice,6 allosteric effects may be induced by the substitution of the β-hairpin. In order to investigate the effect of replacing the β-hairpin of HIV-1 CA with that from MLV, both monomers and assemblies of the WT and MLV:HIV fusion constructs were examined by Hydrogen/Deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX MS). The use of HDX MS allows for the interrogation of protein dynamics and structural interactions both in the β-hairpin region and elsewhere within the protein, either or both of which may be modulated by the replacement of the β-hairpin.

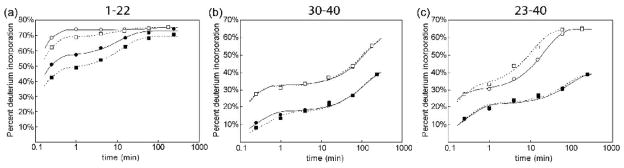

The exchange plots for a peptide which comprises residues 1–22 of the CA proteins contains both the β-hairpin and the N-terminal portion of helix 1 are shown in Figure 7a. While notable protection is observed upon assembly, this is likely due to the strong intermolecular interactions formed within helix 1 and is in line with previously published HDX studies of the HIV-1 CA lattice.7,20 The variations in exchange patterns between the WT CA and MLV:HIV fusion protein in both the monomer (open symbols) and assembled states (solid symbols) suggest the presence of structural or dynamic variations between the two proteins. In the case of the monomers, we interpret this subtle, but statistically significant variation to indicate an increase in the stability of the β-hairpin in the MLV:HIV fusion protein.

Figure 7.

HDX peptide profiles for WT and MLV:HIV analyzed by mass spectrometry. HD exchange plots for peptides covering the N-terminal 40 amino acids of monomeric (open symbols) and assembled (closed symbols) MLV:HIV (□, ■) and WT CA (○, ●). (a) The exchange plot for residues 1–22 show a decrease in exchange for MLV:HIV in both monomeric and assembled forms while (b) the peptide containing amino acids 30–40 show no variation between the proteins. The increased protection in the assembled states is due to intermolecular interactions of helix 2 in the assembled lattice. (c) The 23–40 peptide shows different exchange patterns between monomeric and assembled capsid proteins, which can be explained by a change in the orientation of helix 1 in the monomeric form but not in the assembled state.

In the case of the assembled proteins, the difference in exchange patterns is larger than that of the monomers. At late times the increased exchange protection in the mutant relative to the wild type suggests an increased stabilization from intermolecular interaction for the mutant protein. Examination of the B-MLV26 and N-MLV15 CA hexameric crystal structure indicate possible intermolecular interactions between β-hairpins of adjacent subunits. These interactions are not present in the WT HIV-1 CA hexamer crystal structure.6 The protection observed for the 1–22 peptide on the assembled MLV:HIV fusion protein lattice versus WT is consistent with the presence of an intermolecular interaction similar to that found in the B- and N-MLV structures. Such intermolecular interactions would be expected to increase the protection in the MLV:HIV fusion assembly slightly and, if the interactions are highly stable, show increased protection at long time periods of exchange. In nearly all other detected peptides, no significant variations were observed between WT CA and the MLV:HIV fusion samples. Several peptides showed increased protection upon assembly (such as CA 30–40 shown in Figure 7b) consistent with previously reported results from WT CA in vitro assemblies20 and HIV mature viral like particles.7

In the unassembled form, the peptide that covered the C-terminal portion of helix 1 and part of helix 2 (CA 23–40), exchanged more rapidly in the WT protein than in the fusion protein. This difference was not evident in the assembled samples (Figure 7c). As no statistically significant variation in exchange between fusion and WT proteins was observed for the overlapping peptide spanning CA residues 30–40, the difference in protection in CA 23–40 is confined to residues 23–29. The variation in exchange between the monomeric proteins suggest that the identity of the β-hairpin affects the orientation of helix 1 prior to assembly. However, the identical exchange patterns in the assembled proteins suggest that the orientation of helix 1 is not mediated by the β-hairpin following assembly. As the variation in the exchange pattern is only observed for CA 23–29 in the monomers and not in the assembled lattice, it appears that the MLV β-hairpin has the ability to modulate the orientation or stability of helix 1 compared to the WT β-hairpin.

Fusion construct only marginally reduces virus infectivity

The consequence of changes to the viral core stability induced by the MLV mutation would be expected to be reflected in viral infectivity, as variations in core stability have been shown to affect infectivity.27 To test this, the MLV β-hairpin region was introduced into the pNL4-3 proviral DNA. Human kidney 293T cells were transfected with either WT or MLV:HIV proviral DNAs to produce infectious virions which were purified as described in Material and Methods. The presence of mature virions was confirmed by Western Blot (data not shown). The MLV:HIV fusion virus had a 10-fold decrease in viral yield compared to WT and a 6-fold reduction in infectivity. While the MLV:HIV fusion virus resulted in some deficiencies in both viral yield and infectivity, the production of viral particles shows that some level of conformational plasticity is accepted by the capsid protein, allowing for the formation of mature, infectious particles following the replacement of the β-hairpin.

Discussion

Retroviral capsid proteins are capable of assembling into mature cores in the absence of cellular factors9,12–14,18–24,28 and much previous work has gone into understanding the structural basis of this capability. One core structural determinant of mature CA proteins has been identified as the N-terminal β-hairpin.9,15,18,29 In HIV-1, M-PMV, RSV, HTLV and MLV, this β-hairpin is stabilized by the formation of a salt bridge between an N-terminal proline and an aspartate located in helix 3.6,8,9,15,16,30,31 Modifications and N-terminal extensions of CA that block β-hairpin formation results in the production of spherical, immature-like particles.18,32 Mutations to the N-terminal proline’s proton-accepting partner (aspartate) to alanine, asparagine, glutamine, or glutamate produce similar defects in regard to maturation, morphology and infectivity.9,16,29,33,34 While these experiments highlight the importance of β-hairpin formation in the production of mature, infectious virions, structural studies of the mature HIV-1 CA lattice show no evidence for the presence of any intermolecular interactions involving the β-hairpin6 or any significant alteration to subunit structure.9 By deleting the N-terminal proline, replacing the WT β-hairpin with a flexible Gly-Ser loop, and grafting the β-hairpin from MLV, we have been able to examine the structural/dynamic implications of the β-hairpin and its components on HIV-1 CA.

In this work, we showed that deletion of the N-terminal proline in HIV-1 CA resulted in aberrant in vitro assembled structures, in good agreement with previous data and that the presence of an N-terminal proline alone is not sufficient to support assembly of the mature capsid lattices; whether the proline in the Gly-Ser mutant forms the salt bridge is unknown. A plausible explanation is that the deletion of the proline, which abrogates the formation of the salt bridge, results in a more random conformation of the N-terminal hairpin residues, as suggested by NMR experiments9 and that this, in turn, interferes with assembly of the mature lattice. It has been suggested that formation of the hairpin may destabilize immature interactions and serve as a trigger/scaffold for proper capsid protein rearrangement of the N-terminal domain.10,35 While this is at odds with the observation that, despite cleavage of MA and CA, β-hairpin formation does not occur until the final cleavage CA-SP1 event has occurred,7 it does not preclude a contributing role for the hairpin residues in destabilizing the immature form. Further support for the notion that flexibility in the hairpin residues can help disrupt mature lattice formation is found in the fact that while the Gly-Ser mutant was incapable of assembly despite being properly folded and having a stability similar to wild type CA, Gross et al18 showed that deletion of the first 13 residues of HIV capsid protein (CAΔ13) allows for the formation of tubular structures in vitro, even in the absence of the salt bridge. A unifying explanation for these observations could be that these 13 flexible residues, if present, must be folded to prevent steric clashes.

While the Gly-Ser and ΔPro1 I2V mutants inhibited or largely abolished assembly, grafting the β-hairpin from a structurally similar virus, MLV, to HIV-1 CA enhanced in vitro assembly rates and reduced the level of salt needed to allow assembly. Placing the MLV hairpin into the pNL4-3 proviral DNA generated a mild, 6-fold decrease in infectivity which is similar to reported reductions in infectivity from hairpin mutations Q4A, Q7/Q9A and Q13A.27,36 The ability to form mixed assemblies of the MLV:HIV fusion protein and WT CA, combined with the maintenance of a level infectivity, suggest that the feature(s) that make the fusion construct more amenable to assembly are not dramatically different from that of the WT CA.

The application of HDX MS to monomers and assemblies of WT HIV-1 CA and the MLV:HIV highlight several intriguing variations in protein structure and dynamics. The vast majority of the exchange patterns from detected peptides did not vary between WT and the MLV:HIV fusion proteins although notable variations were observed for the β-hairpin and helix 1. These variations provide explanations for the differing in vitro assembly and infectivity characteristics of the WT and MLV:HIV fusion constructs.

While no variation in the exchange plots were observed for the peptide CA 23–40 between the WT CA and MLV:HIV fusion in the assembled lattices, the dynamics of exchange were varied in the monomers with WT CA being slightly more protected through the intermediate time points of exchange. As an overlapping peptide (CA 30–40) does not change between these two proteins, the difference in protection may be mapped to residues 23–29 and thus, helix 1. The variation in the exchange dynamics indicates that the MLV:HIV fusion hairpin modulates the orientation or dynamics of helix 1 in the monomeric proteins. This alteration of the local environment of helix 1, which forms intermolecular interactions along the six fold axis of symmetry in hexamers, provides a mechanism for the increased assembly dynamics observed for the MLV:HIV fusion construct. In this regard, the orientation of helix 1 in the MLV:HIV fusion appears to be more amenable to assembly. This interpretation is consistent with results from HDX MS experiments of virions where a slight difference in packing of helix 1 was observed in immature and mature virions. Helix 1 was notably destabilized during maturation, suggesting a presence of a transition state between the immature and mature lattices.7 Additionally, the β-hairpin was found to form only following complete gag processing and was postulated to serve as a locking mechanism to stabilize CA in the mature lattice. The increased exchange in the MLV:HIV fusion monomers suggests that helix 1 is either more solvent exposed or slightly less stable than for WT monomers, either of which may aid in nucleating assembly. A comparison between crystal structures of the mature NTD with or without the β-hairpin showed a displacement of helix 1 of ~0.7 Å between the two forms.35 As mixed assemblies of the MLV:HIV fusion and WT CA were able to form and no change in H1 exchange was observed in the assembled state, we can assume that the structural variations in helix 1 observed in the monomeric form are abolished in the assembled hexameric lattice, likely as a result of the numerous intermolecular interactions present in the lattice.6

The peptide that contains the N-terminal β-hairpin in the MLV:HIV fusion protein is notably more protected than WT in both the monomer and assembled forms. In the monomer, the variation is indicative of the formation of a more stable β-hairpin than that of WT. As the peptides exchange to the same extent after ~15 minutes, no large scale structural variations are present in the monomers. The CA 1–22 peptide in the MLV:HIV fusion was also more protected than WT in the assembled form. The increased protection, however, extended to long periods of exchange, suggesting the formation of a stable interaction beyond those present in WT. Close examination of the published B-MLV26 and N-MLV15 hexameric crystal structures suggest the possible presence of an intermolecular interaction involving β-hairpins from adjacent subunits. In the B-MLV structure,26 a hydrogen-bonding interaction is likely present between Arg3 and Tyr12 and is consistent with the reduction of the MLV:HIV assembly’s dependence on salt as Arg3 is expected to be charged at the pH values used in these studies. As variations in core stability have been shown to affect infectivity,27 the additional intermolecular interaction, thus stabilizing the lattice, would be expected to change the infectivity of the virions containing the MLV:HIV CA fusion protein from virions relative to WT CA, as we have observed.

Our results clarify the importance and role of the N-terminal β-hairpin in regard to the HIV-1 mature CA lattice. The β-hairpin appears to provide stability for an otherwise unstructured region that arises during gag processing enroute to the production of mature components. This region also likely modulates and strains the orientation and/or dynamics of helix 1 during viral maturation prior to the formation of the mature β-hairpin. Together our results indicate not only that the N-terminal β-hairpin affects the orientation and assembly dynamics of CA, but also provides evidence that the β-hairpin stabilizes the orientation of CA in the mature lattice while allowing for dynamic motions of helix 1 during maturation in vivo as the CA enables the formation of a lattice that is morphologically distinct from the immature lattice.

Material and Methods

Plasmid mutagenesis

According to the prediction of the web-based program TermiNator,37 deletion of proline 1 followed by an isoleucine would not result in the N-terminal trimming of the initiating Met during heterologous protein expression in E. coli. To circumvent this matter, we introduced an HIV-subtype conserved substitution, I2V along with the N-terminal proline deletion to obtain proper cleavage of methionine. Mass spectrometry showed that ~70% of the expressed protein was properly processed, resulting in valine as the first amino acid of the ΔP1 I2V protein. A glycine-serine loop mutation was prepared by replacing amino acids 3–13 with the repetitive sequence GGSGGSGGSGG. Both ΔP1 I2V and Gly-Ser substitutions were introduced into the wild-type pNL4-3 HIV-1 CA sequence on a pET17b vector with the QuickChange Mutagenesis protocol (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA).

The MLV:HIV fusion CA protein was generated through PCR amplification to create a fragment containing both NdeI and BamHI restriction sites. The NdeI and BamHI restriction enzyme sites were then used to move the MLV β-hairpin encoding fragment into the pNL4-3/pET17b CA vector. All mutagenesis insertions were confirmed by DNA sequencing (Heflin Center, University of Alabama at Birmingham).

The MLV:HIV fusion virus was prepared with the proviral pNL4-3 plasmid as a template and 35 rounds of exponential PCR amplification. Primers for PCR amplification were generated to complement either the capsid protein (forward primer) or the matrix protein (reverse primer). These primers also contained a non-complimentary sequence that corresponded to the MLV hairpin sequence. Introduction of the mutation was confirmed by DNA sequencing Heflin Center (University of Alabama at Birmingham).

Protein expression and purification

Proteins were expressed and purified as previously described.23 Briefly, E. coli BL21 cells containing plasmids encoding for WT HIV CA protein or the various β-hairpin CA mutants were grown to an O.D. of 0.6–0.8 and induced with 0.4 mM IPTG for 4 hours. Cells were harvested and the pellets frozen at −80 °C overnight. Pellets were then resuspended in 50 mM Tris, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, pH 8.4 with 0.01% (w/v) lysozyme, 1 mM PMSF, 1 μg/mL DNase and RNase. Cells were lysed by freeze-thaw cycles in a dry ice-ethanol bath alternating with a water bath set at 37 °C. Cellular debris was pelleted by centrifugation and the protein of interest was precipitated on ice with 20% ammonium sulfate for 1 hour. The precipitate was recovered by centrifugation at 20,000 ×g and the pellet was resuspended at 4 °C in 50 mM Tris, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, pH 8.4. The soluble material was dialyzed against 25 mM Tris, pH 8.4 and centrifuged to separate insoluble matter. The supernatant was loaded in a Q-Sepharose (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) and the protein eluted with a linear NaCl gradient from 0–500 mM. Purified protein fractions were pooled and dialyzed against 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 8.0 and stored at −80 °C until needed.

Circular Dichroism

Protein samples were analyzed by circular dichroism using an AVIV model 620S (Aviv Biomedical, Lakewood, NJ). Spectra were obtained at wavelengths from 190 to 260 nm in a temperature controlled unit at 20 °C with a 0.1 cm pathlength cuvette. Proteins were diluted in sodium phosphate buffer, pH 8.0 to a final concentration of 5 μM. All spectra were averaged over five independent measurements. Protein CD signals were converted to molar ellipticity, [θ], by the formula:

Where θ is the CD signal in millidegrees, Mr is the protein molecular weight, c is the protein concentration in mg/mL and l is the pathlength in cm. Melting curves were obtained using the same protein conditions across temperatures ranging from 20–90 °C with an incubation at each temperature of 30 seconds.

In vitro assembly and data analysis

Assembly reactions were triggered by the rapid dilution of 50 mM sodium phosphate, 4 M NaCl, pH 8.0 to a protein solution to reach the desired NaCl concentration for assembly. Protein polymerization was followed by an increase in turbidity over time, monitored on a Beckman DU640 spectrometer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA) at 350 nm every 20 or 30 seconds for up to 1 hour. The elapsed time between the addition of NaCl and the first optical density measurement was approximately 20 seconds. The log phase of each reaction was fit to a linear equation using Sigma Plot (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA) to examine the assembly kinetics of each reaction.

Electron Microscopy

Products of the assembly reactions were blotted on copper or nickel formvar-coated grids for 2 minutes and negatively stained with 1% uranyl acetate. Grids were observed using a Titan transmission electron microscope (FEI, Hillsboro, OR) operating with an accelerating voltage of 60 or 80 kV.

Hydrogen/Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry (HDX MS)

Monomers of the HIV-1 WT CA and MLV:HIV fusion construct were prepared for HDX MS in 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 8.0. To examine the products of assembly, HIV-1 WT CA or MLV:HIV fusion proteins were allowed to assemble for 1 hour at room temperature and then purified from monomers by centrifugation. Hydrogen-deuterium exchange was initiated by diluting ~2 μg of sample tenfold into deuterated 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pD ~7.6 with or without 2 M NaCl. Samples were exchanged for up to 48 hours and, after selected periods of time, the exchange reaction was quenched by the addition of formic acid and guanidine hydrochloride to 1% and 1.5 M final concentration respectively. Samples were then either frozen immediately (monomers) or digested with pepsin for 1 minute prior to rapid freezing (assemblies) in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. Immediately prior to analysis, samples were quickly thawed and, in the case of the monomers, digested with 1 mg/mL pepsin for 1 min. Samples were injected onto a C4 trap (Microm BioResources, Inc, Auburn, CA), rapidly eluted by a 5–95% acetonitrile gradient, and detected with a hybrid ion trap-FT ICR mass spectrometer (LTQ-FT, Thermo Finnigan, Waltham, MA). Exchanged peptides were identified via exact mass measurements with the FT-ICR MS in exchange experiments and are based on peptide identifications determined in parallel experiments of unexchanged proteins by MS/MS sequencing.

The extent of deuterium incorporation at each time point was determined by calculating the centroid of the isotopic distribution of each peptide using the HD Desktop software package38 and comparing these values to those from non-exchanged samples. Exchange plots were represented as the number of deuterons incorporated versus time. These plots were then fit to a sum of exponentials derived from the exchange rate expression:39

where D is the observed number of deuterons incorporated at time t and N is the total number of protons which exchanged within the time domains of the experiment. A and B correspond to the number of exchangeable sites that are observed to exchange with a rate constant k1 >1.0 min−1 and k2 <1.0 min−1 respectively. The regression values for A and B and the associated standard error calculated from the fits were used to calculate a p-value via a two-tailed t-test in order to strengthen the determination of variance as observed in the exchange profiles for individual peptides across the constructs.

Virus production

Human kidney 293T cells were transfected with wild type or MLV:HIV pNL4-3 proviral DNAs using a ratio of Fugene:DNA (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) of 3:1 or 6:1 for 72 h at 37 °C in a 5% carbon dioxide atmosphere. Supernatants containing the virus progeny was aspirated, cellular debris was separated by centrifugation and the virus-containing supernatant was stored at −80 °C until needed. To examine viral infectivity, JC53.bl reporter cells were infected with either HIV-1 WT or MLV:HIV and infectivity was measured as previously described.40 Infectivity was also measured using a p24 antigen ELISA kit as described by the manufacturer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA). Virus samples were further purified for Western blotting by centrifuging the semi-purified virus stocks through a 20% sucrose cushion at 64,000×g for 2 hours. Pellets were ressuspended in STE buffer at 4 °C overnight.

Western Blotting of infectious particles

HIV-1 WT and MLV:HIV viruses were inactivated by the addition of 10x Laemmli buffer and boiled for 5 minutes prior to separation with a 12.5% SDS-PAGE gel. Separated proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane using a wet system for 2 hours at 100 V at 4 °C. Following transfer, the membrane was blocked for 1 hour with 4% non-fat milk diluted in PBS (GIBCO, Carlsbad, CA), and blotted with either anti-HIV-2 1343 (rabbit, with cross-reactivity to gag and its processing products) or anti-CA ARF (goat, anti-HIV-1 gag) overnight at 4 °C, under gentle shaking. Excess antibody was removed by washing the membrane with PBS/milk and then incubated with anti-rabbit-IgG-HRP or anti-goat-IgG-HRP (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL) for 1 hour. Chemiluminescence was detected by incubating the blotted membrane with ECL (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) for 2 minutes and exposing the membrane to film.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Cynthia Rodenburg for cloning assistance, Dr. Carolyn Teschke for critical review of the data and Dr. Matthew Renfrow for technical support of the UAB Biomedical FT-ICR MS laboratory. This work was supported by NIH grant R01AI044626 to PEP and fellowship support to EM (F32GM087994).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Briggs JA, Simon MN, Gross I, Krausslich HG, Fuller SD, Vogt VM, Johnson MC. The stoichiometry of Gag protein in HIV-1. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:672–5. doi: 10.1038/nsmb785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Briggs JA, Riches JD, Glass B, Bartonova V, Zanetti G, Krausslich HG. Structure and assembly of immature HIV. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:11090–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903535106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright ER, Schooler JB, Ding HJ, Kieffer C, Fillmore C, Sundquist WI, Jensen GJ. Electron cryotomography of immature HIV-1 virions reveals the structure of the CA and SP1 Gag shells. EMBO J. 2007;26:2218–26. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lanman J, Lam TT, Emmett MR, Marshall AG, Sakalian M, Prevelige PE., Jr Key interactions in HIV-1 maturation identified by hydrogen-deuterium exchange. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:676–7. doi: 10.1038/nsmb790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ganser-Pornillos BK, Cheng A, Yeager M. Structure of full-length HIV-1 CA: a model for the mature capsid lattice. Cell. 2007;131:70–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pornillos O, Ganser-Pornillos BK, Kelly BN, Hua Y, Whitby FG, Stout CD, Sundquist WI, Hill CP, Yeager M. X-ray structures of the hexameric building block of the HIV capsid. Cell. 2009;137:1282–92. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Monroe EB, Kang S, Kyere SK, Li R, Prevelige PE., Jr Hydrogen/deuterium exchange analysis of HIV-1 capsid assembly and maturation. Structure. 2010;18:1483–91. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gitti RK, Lee BM, Walker J, Summers MF, Yoo S, Sundquist WI. Structure of the amino-terminal core domain of the HIV-1 capsid protein. Science. 1996;273:231–5. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5272.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.von Schwedler UK, Stemmler TL, Klishko VY, Li S, Albertine KH, Davis DR, Sundquist WI. Proteolytic refolding of the HIV-1 capsid protein amino-terminus facilitates viral core assembly. EMBO J. 1998;17:1555–68. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.6.1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang C, Ndassa Y, Summers MF. Structure of the N-terminal 283–residue fragment of the immature HIV-1 Gag polyprotein. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9:537–43. doi: 10.1038/nsb806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freed EO. HIV-1 gag proteins: diverse functions in the virus life cycle. Virology. 1998;251:1–15. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li S, Hill CP, Sundquist WI, Finch JT. Image reconstructions of helical assemblies of the HIV-1 CA protein. Nature. 2000;407:409–13. doi: 10.1038/35030177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ganser BK, Li S, Klishko VY, Finch JT, Sundquist WI. Assembly and analysis of conical models for the HIV-1 core. Science. 1999;283:80–3. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5398.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ganser-Pornillos BK, von Schwedler UK, Stray KM, Aiken C, Sundquist WI. Assembly properties of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 CA protein. J Virol. 2004;78:2545–52. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.5.2545-2552.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mortuza GB, Haire LF, Stevens A, Smerdon SJ, Stoye JP, Taylor IA. High-resolution structure of a retroviral capsid hexameric amino-terminal domain. Nature. 2004;431:481–5. doi: 10.1038/nature02915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abdurahman S, Youssefi M, Hoglund S, Vahlne A. Characterization of the invariable residue 51 mutations of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capsid protein on in vitro CA assembly and infectivity. Retrovirology. 2007;4:69. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-4-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fitzon T, Leschonsky B, Bieler K, Paulus C, Schroder J, Wolf H, Wagner R. Proline residues in the HIV-1 NH2-terminal capsid domain: structure determinants for proper core assembly and subsequent steps of early replication. Virology. 2000;268:294–307. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gross I, Hohenberg H, Huckhagel C, Krausslich HG. N-Terminal extension of human immunodeficiency virus capsid protein converts the in vitro assembly phenotype from tubular to spherical particles. J Virol. 1998;72:4798–810. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.4798-4810.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gross I, Hohenberg H, Krausslich HG. In vitro assembly properties of purified bacterially expressed capsid proteins of human immunodeficiency virus. Eur J Biochem. 1997;249:592–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.t01-1-00592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lanman J, Lam TT, Barnes S, Sakalian M, Emmett MR, Marshall AG, Prevelige PE., Jr Identification of novel interactions in HIV-1 capsid protein assembly by high-resolution mass spectrometry. J Mol Biol. 2003;325:759–72. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01245-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campbell S, Vogt VM. Self-assembly in vitro of purified CA-NC proteins from Rous sarcoma virus and human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1995;69:6487–97. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.10.6487-6497.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ehrlich LS, Agresta BE, Carter CA. Assembly of recombinant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capsid protein in vitro. J Virol. 1992;66:4874–83. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.8.4874-4883.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lanman J, Sexton J, Sakalian M, Prevelige PE., Jr Kinetic analysis of the role of intersubunit interactions in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capsid protein assembly in vitro. J Virol. 2002;76:6900–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.14.6900-6908.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Douglas CC, Thomas D, Lanman J, Prevelige PE., Jr Investigation of N-terminal domain charged residues on the assembly and stability of HIV-1 CA. Biochemistry. 2004;43:10435–41. doi: 10.1021/bi049359g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schreiber G, Fersht AR. Rapid, electrostatically assisted association of proteins. Nat Struct Biol. 1996;3:427–31. doi: 10.1038/nsb0596-427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mortuza GB, Dodding MP, Goldstone DC, Haire LF, Stoye JP, Taylor IA. Structure of B-MLV capsid amino-terminal domain reveals key features of viral tropism, gag assembly and core formation. J Mol Biol. 2008;376:1493–508. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Forshey BM, von Schwedler U, Sundquist WI, Aiken C. Formation of a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 core of optimal stability is crucial for viral replication. J Virol. 2002;76:5667–77. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.11.5667-5677.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campbell S, Rein A. In vitro assembly properties of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag protein lacking the p6 domain. J Virol. 1999;73:2270–9. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.2270-2279.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Macek P, Chmelik J, Krizova I, Kaderavek P, Padrta P, Zidek L, Wildova M, Hadravova R, Chaloupkova R, Pichova I, Ruml T, Rumlova M, Sklenar V. NMR structure of the N-terminal domain of capsid protein from the mason-pfizer monkey virus. J Mol Biol. 2009;392:100–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cornilescu CC, Bouamr F, Carter C, Tjandra N. Backbone (15)N relaxation analysis of the N-terminal domain of the HTLV-I capsid protein and comparison with the capsid protein of HIV-1. Protein Sci. 2003;12:973–81. doi: 10.1110/ps.0235903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cornilescu CC, Bouamr F, Yao X, Carter C, Tjandra N. Structural analysis of the N-terminal domain of the human T-cell leukemia virus capsid protein. J Mol Biol. 2001;306:783–97. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nandhagopal N, Simpson AA, Johnson MC, Francisco AB, Schatz GW, Rossmann MG, Vogt VM. Dimeric rous sarcoma virus capsid protein structure relevant to immature Gag assembly. J Mol Biol. 2004;335:275–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leschonsky B, Ludwig C, Bieler K, Wagner R. Capsid stability and replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 are influenced critically by charge and size of Gag residue 183. J Gen Virol. 2007;88:207–16. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81894-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wildova M, Hadravova R, Stokrova J, Krizova I, Ruml T, Hunter E, Pichova I, Rumlova M. The effect of point mutations within the N-terminal domain of Mason-Pfizer monkey virus capsid protein on virus core assembly and infectivity. Virology. 2008;380:157–63. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kelly BN, Howard BR, Wang H, Robinson H, Sundquist WI, Hill CP. Implications for viral capsid assembly from crystal structures of HIV-1 Gag(1–278) and CA(N)(133–278) Biochemistry. 2006;45:11257–66. doi: 10.1021/bi060927x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.von Schwedler UK, Stray KM, Garrus JE, Sundquist WI. Functional surfaces of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capsid protein. J Virol. 2003;77:5439–50. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.9.5439-5450.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frottin F, Martinez A, Peynot P, Mitra S, Holz RC, Giglione C, Meinnel T. The proteomics of N-terminal methionine cleavage. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:2336–49. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600225-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pascal BD, Chalmers MJ, Busby SA, Griffin PR. HD desktop: an integrated platform for the analysis and visualization of H/D exchange data. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2009;20:601–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2008.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Englander SW, Kallenbach NR. Hydrogen exchange and structural dynamics of proteins and nucleic acids. Q Rev Biophys. 1983;16:521–655. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500005217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wei X, Decker JM, Liu H, Zhang Z, Arani RB, Kilby JM, Saag MS, Wu X, Shaw GM, Kappes JC. Emergence of resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in patients receiving fusion inhibitor (T-20) monotherapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:1896–905. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.6.1896-1905.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ganser-Pornillos BK, Yeager M, Sundquist WI. The structural biology of HIV assembly. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2008;18:203–17. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]