Abstract

The control of bovine tuberculosis and atypical mycobacterioses in cattle in developing countries is important but difficult because of the existence of wildlife reservoirs. In cattle farms in Tanzania, mycobacteria were detected in 7.3% of 645 small mammals and in cow's milk. The cattle farms were divided into “reacting” and “nonreacting” farms, based on tuberculin tests, and more mycobacteria were present in insectivores collected in reacting farms as compared to nonreacting farms. More mycobacteria were also present in insectivores as compared to rodents. All mycobacteria detected by culture and PCR in the small mammals were atypical mycobacteria. Analysis of the presence of mycobacteria in relation to the reactor status of the cattle farms does not exclude transmission between small mammals and cattle but indicates that transmission to cattle from another source of infection is more likely. However, because of the high prevalence of mycobacteria in some small mammal species, these infected animals can pose a risk to humans, especially in areas with a high HIV-prevalence as is the case in Tanzania.

1. Introduction

The genus Mycobacterium comprises more than 140 named species recognized currently [1], of which several are pathogenic; most of them are environmental mycobacteria that may cause opportunistic infections. The pathogenic species are responsible for some important diseases in humans and animals in the developed world as well as in developing countries, namely, tuberculosis (TB), leprosy, and Buruli ulcer [2]. Susceptibility to mycobacterial infections can be higher in patients with underlying conditions such as human immunodeficiency virus-acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV-AIDS), sarcoidosis, silicosis, or emphysema. With the rising number of HIV-AIDS patients in Africa, TB and in some extent other mycobacterial diseases, caused by, for example, M. avium complex, are an important cause of morbidity and mortality [3]. Mycobacterial diseases in cattle such as bovine tuberculosis (BTB), caused by Mycobacterium bovis, and atypical mycobacterioses (e.g., paratuberculosis caused by M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis) can also have serious implications on public health and on economy [4–6]. Therefore, the control of BTB and atypical mycobacterioses is important. In countries with a wildlife reservoir of M. bovis, BTB in cattle is more difficult to control. In the UK, New Zealand, the United States, and Africa, a number of animals have been found to be infected with and act as a reservoir for M. bovis, namely, the European badger (Meles meles), brushtail possums (Trichosurus vulpecula), white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) and bison (Bison bison), and the African buffalo (Syncerus caffer), respectively [7].

Not much research has been conducted on the wildlife reservoir of M. bovis in sub-Saharan Africa and research has focused mainly on the presence of M. bovis in South Africa [8–11]. In Tanzania in 2005, M. bovis was demonstrated in free-ranging wildlife, namely, in wildebeest, topi, the lesser kudu, and lions in the Serengeti national park, the Tarangire National Park, and the Ngorongoro crater in Tanzania [12]. More information is present on the prevalence of M. bovis-infection in cattle in Tanzania. This prevalence ranges between 0.2% and 14% and that of atypical mycobacterioses in cattle between 0% and 13.0% [6, 13–17].

Also, other pathogenic mycobacterial species including M. microti, M. avium, and M. marinum have been found in wild animals [18–21]. Although these mycobacteria are less virulent for humans, they do cause infections or diseases in humans, especially when humans are immunocompromized [3, 22, 23]. As such, animals could transmit mycobacteria to humans [24].

Until present, little research is performed on the reservoir status of rodents and insectivores for mycobacteria [19, 21, 25–27] although they are hosts for pathogens causing diseases in humans and livestock [28, 29] such as leptospirosis, plague, and toxoplasmosis [30]. Cattle farms can be prone to rodent infestations because of the abundant amounts of shelter, water, and food [31], thus augmenting the rate of direct or indirect contact between rodents and cattle and the risk of disease transmission. Moreover, rodents are sensitive to experimental infection with mycobacteria that can cause disease in cattle, for example, M. bovis and M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis [32, 33] and recent studies have shown that African rodents and insectivores can carry mycobacteria of the M. avium-complex [21, 26]. In developed areas (UK and New-Zealand), rodents and insectivores were found to carry M. bovis [29, 34, 35] but with a low estimated transmission risk [20, 36]. However, in Africa, other rodent and insectivore species are present and the risks of rodent-borne diseases (both for humans and cattle) are higher because of a higher contact rate between humans, cattle, and rodents.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the possibility of a rodent/insectivore reservoir for M. bovis and other mycobacteria in Tanzania, from which cattle (and humans) could be infected. We have collected small mammals in cattle farms with a known tuberculin status. The single comparative intradermal tuberculin test (SCITT) can detect cattle exposed to M. bovis as well as atypical mycobacteria [37, 38]. A positive SCITT test can thus serve as an indication for exposure to mycobacteria. By targeting the small mammal collection in cattle farms housing animals with known reactor status, we can get an indication of the transmission direction or the involvement of other source(s) of infection as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Interpretation of possible differences in prevalences of mycobacteria in small mammals in relation to the reactor status of the farm on which the small mammals were collected.

| Analysis in relation to | Possible difference in prevalence of mycobacteria in small mammals collected in reacting and nonreacting farms | Indication on transmission direction and the involvement of other source(s) of infection* |

|---|---|---|

| (1) Current reactor status | (a) No difference | Transmission between small mammals and cattle might occur, but cattle and small mammals probably have a different source of infection |

| (b) Higher prevalence in currently reacting as compared to non reacting farms | Transmission between small mammals and cattle might occur, but common source of infection more probable. | |

| (c) Higher prevalence in currently nonreacting as compared to reacting farms | Transmission between small mammals and cattle might occur, but cattle and small mammals probably have a different source of infection | |

| (2) Future reactor status | (a) No difference | Transmission from small mammals to cattle might occur, but cattle also has another source of infection |

| (b) Higher prevalence in future reacting as compared to non reacting farms | Tranmission from small mammals to cattle may occur, either directly or indirectly | |

| (c) Higher prevalence in future nonreacting as compared to reacting farms | Transmission from small mammals to cattle might occur, but cattle has another, probably more important, source of infection | |

| (3) Past reactor status | (a) No difference | Transmission from cattle to small mammals might occur, but small mammals also have another source of infection |

| (b) Higher prevalence in past reacting as compared to non reacting farms | Transmission from cattle to small mammals may occur, either directly or indirectly | |

| (c) Higher prevalence in past nonreacting as compared to reacting farms | Transmission from cattle to small mammals might occur, but small mammals have another, probably more important, source of infection |

*Another source of infection can be other wild or domestic animals, the environment, or humans.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Trapping Sites

A total of 26 cattle farms were chosen in and around Morogoro, a medium-sized city 200 km west of Dar es Salaam (37.26–37.49°E; 6.18–6.52°S). These farms can be divided into two reactor types based on the single comparative intradermal tuberculin test (SCITT) conducted in the cattle residing on the farms in 2005 and 2006 [14]. For all animals, the “current reactor status” at the moment the trapping took place was known. For the trapping period of 2005, the “future reactor status” of the farms was known (i.e., the SCITT-results of 2006). For the trapping period of 2006, the “past reactor status” of the farms was known (i.e., the SCITT-results of 2005). Other trapping sites included a grass field around the slaughterhouse in Morogoro, and a quarter in Morogoro where a high prevalence of mycobacteria in rodents and insectivores was observed in a previous study, namely, Mwembesongo [21].

The trapping took place in the wet and dry season of both 2005 and 2006.

2.2. Sample Collection

Three types of live traps were used: Sherman LFA Live Traps, Box traps, and big wire cage traps [21]. Peanut butter with maize bran and fresh maize cobs were used as bait [21].

The animals were processed in the laboratory following a standard protocol as described by Durnez et al. [21]. In brief, the animals were euthanized with chloroform, and external characteristics and measurements such as weight and head-body length were recorded. During necropsy, pieces of liver, spleen, lung, mesenteric lymph nodes, and external lesions if present were taken for detection of mycobacteria. The carcasses were kept in formalin and sent to the University of Antwerp for further identification to species level: primary identification was confirmed, and skulls were removed and cleaned to identify the animals to species level.

2.3. Pooling of Samples and Detection and Identification of Mycobacteria

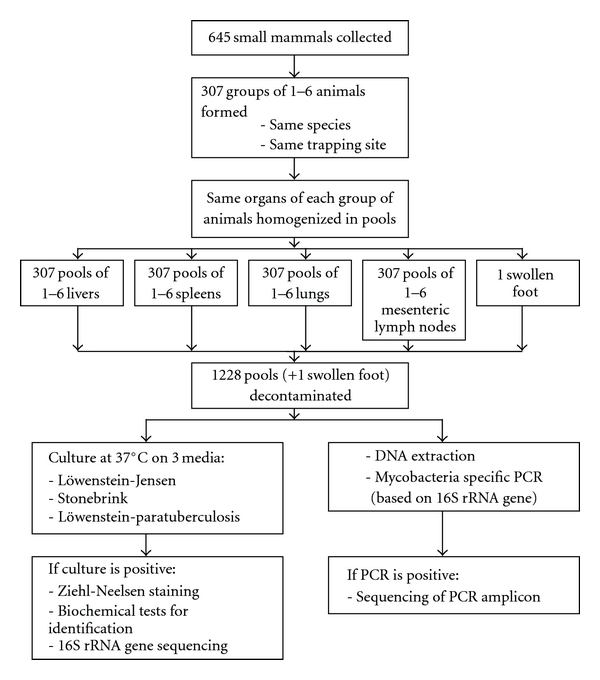

The samples were pooled in a stratified way: the same organs were pooled per one to six individuals of the same species trapped at the same trapping site. A flow chart of the pooling procedure is given in Figure 1. The number of animals in a pool depended on the trapping number per species at a trapping site (resulting in 1 to 6 animals per pool). In this way, 645 individual animals were pooled into 307 groups of individuals. For each group, the four different organ homogenates collected from each animal were pooled separately, resulting in 1228 pools to be tested. A subset of samples was used to test whether pool screening and individual screening gave comparable prevalence estimations. In this subset of samples, the pooled results and the individual results were available.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of pooling procedure.

The pools were analyzed for the presence of mycobacteria by culture and PCR as described before [21]. In short, the organs were homogenized and decontaminated to reduce overgrowth of nonmycobacterial organisms [39], before inoculating them on culture media (Löwenstein-Jensen, Stonebrink, and Löwenstein-paratuberculosis medium [40]) and performing DNA extraction (described in [41]) and PCR (described in [14]) with inhibition check.

Cultivation took place at 37 degrees C [39] for ten to twelve months.

The mycobacteria isolated on culture were checked for acid fastness using Ziehl-Neelsen staining (ZN) and identified to species-level by biochemical methods and by sequencing the 16 S rRNA gene [42].

2.4. Collection and Analysis of Milk Samples

Every trapping period, from every milking cow on the cattle farms where small mammals had been trapped, a milk sample (1 to 10 mL per cow) was collected. The milk samples were kept at −20°C and analyzed in Belgium by culture and PCR as described by Durnez et al. [14].

2.5. Data Analysis

For the results of the pooled samples, the data analysis was based on the use of likelihood ratio tests (LRTs) in the usual parametric model for pool testing. The pool screening sampling model is basically that of a Bernoulli trial with success probability θ = [1−(1−p)n], where n is the pool size and p is the infection rate in the population of interest. The random variable which is denoted by X is the result of the testing of the pool and has value 1 if the pool is positive and 0 if the pool is negative.

Thus, the probability model describing the sampling is given by the probability mass function

| (1) |

This model has a long history in the statistics literature [43–47] and is described in detail in all of these papers. The investigator collects pools of various sizes, ni, and after testing the pool knows the value of the result, denoted by xi. Thus, for any pool, given the pair (ni, xi), the only unknown quantity in the model is the value of p. The standard method for estimating p is the method of maximum likelihood [48]. This depends on the likelihood function which in this case is

| (2) |

where m is the number of pools tested. The maximum likelihood estimate (MLE) is found by maximizing L(p) as a function of p. We note that no special adjustments are required for the inequality of the pool sizes, because this is a feature which is part of the model. This sampling model is the basis for constructing any standard likelihood ratio type test. Tests for a one way or two way design are constructed by replacing p by a linear model in the factors of interest. In this case, a coding scheme analogous to cell mean coding in standard analysis of variance is convenient. Likelihood ratio test methods are a standard technique in statistics. Details of the actual implementation of such tests in this case are computationally complex and requires extensive mathematics but would add nothing to the subject matter of this paper. The calculations were done using a custom FORTRAN program running under MS Windows developed by one of the authors (C. R. Katholi). The core of the estimation is the optimization software used, in this case the program NLPQLP [49–51].

A kappa-test (using SPSS 16.0) was used to compare the results of the individual versus pooled samples analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Trapping Results

The number of animals trapped in this study are listed per species in Table 2.

Table 2.

Rodents and insectivores trapped in and around Morogoro and the prevalence of mycobacteria in the different animal species.

| Animal species | Total number of animals trappeda | Number of groups analyzed for mycobacteria | Number of groups positive for mycobacteria | Estimated mycobacterial prevalence (95% confidence interval) | 95% confidence intervals for zeroestimates of M. bovis and M. avium subsp. Paratuberculosis prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rodents | |||||

| Rattus rattus (Linnaeus, 1758) | 268 (216/1/51) | 94 | 7 | 2.8% (1.0–5.7%) | 0–0.71% |

| Mastomys natalensis (Smith, 1834) | 165 (142/23/0) | 91 | 12 | 7.5% (3.7–13.1%) | 0–1.15% |

| Cricetomys gambianus Waterhouse, 1840 | 36 (12/2/22) | 32 | 8 | 23.9% (10.3–42.7%) | 0–5.19% |

| Mus spp. | 29 (2/1/26) | 22 | 0 | 0% (0–6.4%) | 0–6.4% |

| Grammomys surdaster Mathey, 1971 | 3 (3/0/0) | 3 | 0 | 0% (0–47.3%) | 0–47.3% |

| Gerbilliscus vicina (Matschie 1911) | 2 (0/2/0) | 2 | 0 | 0% (0-61.7%) | 0-61.7% |

| Squirrel (not identified) | 1 (1/0/0) | 1 | 0 | 0% (0–85.3%) | 0–85.3% |

| Insectivores | |||||

| Crocidura hirta Peters, 1852 | 137 (127/9/1) | 58 | 15 | 12.5% (6.8–20.4%) | 0–3.3% |

| Atelerix albiventris Wagner, 1841 | 4 (1/3/0) | 4 | 2 | 50% (7.7–92.3%) | 0–38.1% |

a(on cattle farms/around slaughterhouse/in Mwembesongo).

3.2. Mycobacterial Results

3.2.1. Comparison of Pool Prevalence Estimation versus Individual Prevalence Estimation

For culture and PCR, the respective Kappa-values, comparing the results of the pooled samples and the individual samples, were 0.691 and 0.876, showing a high concordance. For culture, the estimated prevalence with pool prevalence estimation was 6.8% (95% CI: 2.8%–13.3%), while with individual tests the prevalence was estimated to be 7.6% (95% CI: 3.5%–14.0%). For PCR, these estimated prevalences were respectively 3.3% (95% CI: 0.8%–8.2%) and 3.8% (95% CI: 1.2%–8.8%).

3.2.2. Mycobacteria Detected in Rodents and Insectivores

The number of positive groups for mycobacteria and the estimated prevalence are listed in Table 2, the identification of the mycobacteria in Table 3. A total of 44 groups out of 307 tested positive for mycobacteria in culture or PCR, which makes a total estimated prevalence of 7.3%. The estimated prevalence of mycobacteria in C. gambianus was higher than in M. natalensis (P = .011) and in R. rattus (P < .001), while no significant difference was observed with C. hirta (P = .123). C. hirta also carried more mycobacteria than R. rattus (P < .001), while no difference was observed with M. natalensis (P = .164). M. natalensis carried significantly more mycobacteria than R. rattus (P = .028).

Table 3.

Mycobacteria detected in rodent and insectivores in and around Morogoro, Tanzania.

| Mycobacteriaa | Small mammal species | Detected by PCR or culture |

|---|---|---|

| Human risk group 1c | ||

| M. duvalii*** | C. gambianus | Culture |

| M. gordonae | A. albiventris | PCR |

| M. gordonae-like | C. gambianus | PCR |

| M. gordonae-like** | C. hirta | Culture |

| M. gordonae-like | C. hirta | PCR |

| M. gordonae-like | M. natalensis | PCR |

| M. moriokaense* | R. rattus | Culture |

| M. mucogenicum | M. natalensis | PCR |

| M. nonchromogenicum | C. hirta | Culture |

| M. nonchromogenicum* b | R. rattus | Culture |

| M. nonchromogenicum-like | M. natalensis | Culture |

| M. nonchromogenicum-like | R. rattus | PCR |

| M. sphagni-like | R. rattus | PCR |

| M. terrae | C. hirta | Culture |

| M. terrae*** | C. gambianus | Culture |

| M. terrae | R. rattus | Culture |

| Human risk group 2c | ||

| M. chelonae var. niacinogenes | M. natalensis | PCR and culture |

| M. genavense-like | C. hirta | PCR |

| M. intracellulare*** | C. gambianus | Culture |

| M. intracellulare | C. hirta | Culture |

| M. intracellulare | C. hirta | PCR and culture |

| M. intracellulare | C. hirta | Culture |

| M. intracellulare | M. natalensis | PCR and culture |

| M. intracellulare-like | C. gambianus | Culture |

| M. intracellulare-like | C. gambianus | Culture |

| M. intracellulare-like | C. hirta | Culture |

| M. scrofulaceum-like | C. gambianus | Culture |

| M. szulgai | M. natalensis | PCR |

| MAIS | C. gambianus | PCR and culture |

| MAIS | C. gambianus | Culture |

| MAIS | C. hirta | PCR and culture |

| Recently described species, not yet classifiedc | ||

| M. alsiensis | M. natalensis | PCR and culture |

| M. chimaera | C. hirta | Culture |

| M. chimaera-like | C. hirta | Culture |

| M. colombiense | C. hirta | PCR and culture |

| M. frederiksbergense-like | M. natalensis | PCR |

| M. goodii* b | R. rattus | Culture |

| M. immunogenum | R. rattus | PCR |

| M. septicum | A. albiventris | PCR |

| M. septicum | M. natalensis | PCR |

| M. septicum | M. natalensis | PCR |

a *, ** and *** point out mycobacteria detected in the same group of animals but in different organs.

bThese mycobacteria were first detected in 2005 in R. rattus trapped on a farm and were later detected in 2006 in the milk of cattle residing on the same farm (see Table 6).

cThe classification in human risk groups is based on the clinical point of view in which human risk group 1 contain species that never or with extreme rarity cause disease. Human risk group 2 are species that normally live freely in the environment but also cause opportunistic infections in humans. Human risk group 3 are the obligate pathogens (M. tuberculosis complex and M. leprae) [52].

When testing for a difference between organs, the liver was found to be the least infested with mycobacteria, while the lung was most prone to contain mycobacteria (Page's test statistic L = 115.5; α < 0.01). The positivity of mycobacteria in the different organs per animals species is given in Table 4.

Table 4.

Positivity of mycobacteria (in %) in different organs for all animals and for the main animal species collected.

| Liver | Spleen | Lung | Mesenteric lymph nodes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All animals | 1.6 (0.8–2.7) | 2.1 (1.1–3.4) | 3.2 (2.0–4.8) | 1.9 (1.0–3.2) |

| C. gambianus | 5.9 (1.0–17.4) | 5.9 (9.0–17.4) | 8.9 (2.2–21.8) | 8.3 (2.0–20.4) |

| C. hirta | 2.2 (0.6–5.7) | 5.5 (2.4–10.5) | 5.3 (2.3–10.1) | 3.9 (1.4–8.3) |

| M. natalensis | 1.2 (0.2–3.7) | 1.2 (1.2–3.7) | 3.7 (1.5–7.4) | 3.7 (1.5–7.4) |

| R. rattus | 0.38 (0.020–1.7) | 0.38 (0.020–1.7) | 1.6 (0.48–3.6) | 0.76 (0.13–2.3) |

Page's test for order tests the following hypothesis:

H0: liver = spleen = lymph = lung; Ha: liver < spleen < lymph < lung.

Test statistic L = 115,5; α < 0.01.

A total of 33 groups out of 233 groups of animals trapped on cattle farms tested positive for mycobacteria, with an estimated prevalence of 7.0%. Since we were interested in the relation between the SCITT reactor status of the farm (current, past, or future) and the mycobacterial presence in rodents and insectivores, the analyses were performed for the current, past, and future reactor status of the farms, when enough data were available. Results are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Prevalence of mycobacteria in rodents and insectivores trapped on cattle farms, around the slaughterhouse and in Mwembesongo. RR: positive tuberculin reactor status; NR: negative tuberculin reactor status. The P values given are significance values for the difference between RR and NR farms.

| Cattle farms | SH | MS | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current reactor status | Past reactor status | Future reactor status | |||||||||

| RR | NR | P | RR | NR | p | RR | |||||

| Total | 8.8% | 2.9% | .014* | 4.1% | 8.9% | .495 | 8.3% | ||||

| Rodents | 6.2% | 3.1% | .216 | 2.6% | 0.0% | .438 | 9.1% | ||||

| C. gambianus | 12.5% | 0.0% | .448 | na | na | na | na | ||||

| M. natalensis | 9.7% | 0.0% | .062 | 4.0% | 0.0% | .673 | 10.4% | ||||

| R. rattus | 3.0% | 4.4% | .644 | 1.1% | 0.0% | .497 | 7.3% | ||||

| Insectivores | 18.2% | 2.4% | .009* | 9.8% | 61.0% | .019* | 9.4% | ||||

| C. hirta | 18.2% | 2.5% | .010* | 10.0% | 61.0% | .019* | 9.4% | ||||

*The difference is statistically significant at P < .05.

na: not applicable because of insufficient or no data.

SH: Slaughterhouse.

MS: Mwembesongo.

Additionally, two-way ANOVA analyses revealed no effect of season (dry or wet) on the prevalence of mycobacteria in rodents and insectivores in RR and NR farms (data not shown). One-way ANOVA analyses showed that there was no difference in the prevalence of mycobacteria in farms that changed reactor status (NR to RR or RR to NR) during the study as compared to farms of which the reactor status remained the same (NR or RR) (data not shown).

The prevalence of mycobacteria in rodents and insectivores trapped around the slaughterhouse and in Mwembesongo is listed in Table 5. No significant difference was found in the prevalence between rodents and insectivores trapped on these sites. When comparing the prevalence of mycobacteria in the animals trapped around the slaughterhouse and trapped in the NR and RR farms (current reactor status), a significant difference was observed (P = .001) with a significant interaction in the two-way ANOVA (P = .04). For insectivores, a significantly higher prevalence was observed in slaughterhouse as compared to NR farms (P = .007), while no difference was observed with RR farms (P = .280). No difference was observed for the past or future reactor status of the farms. Also, no difference was observed between the prevalence of mycobacteria in rodents trapped in Mwembesongo and in the NR or RR farms.

Out of 226 milk samples collected on the same farms where animals had been trapped, 6 (2.7%) were positive for mycobacteria by culture and 12 (5.3%) by PCR. The identifications of the mycobacteria are listed in Table 6.

Table 6.

Mycobacteria detected in cow milk on the cattle farms.

| Mycobacteria | Detected by PCR or culture |

|---|---|

| Human risk group 1b | |

| M. neoaurum | PCR |

| M. nonchromogenicum | Culture |

| M. nonchromogenicum a | Culture |

| M. gordonae | PCR |

| Human risk group 2b | |

| M. asiaticum | Culture |

| M. szulgai-like | Culture |

| Recently described species, not yet classified b |

|

| M. engbaekii | Culture |

| M. goodii a | PCR |

| M. lacticola | PCR |

| M. septicum | PCR |

aThese mycobacteria were first detected in 2005 in R. rattus trapped on a farm and were later detected in 2006 in the milk of cattle residing on the same farm (see Table 3).

bThe classification in human risk groups is based on the clinical point of view in which human risk group 1 contain species that never or with extreme rarity cause disease. Human risk group 2 are species that normally live freely in the environment but also cause opportunistic infections in humans. Human risk group 3 are the obligate pathogens (M. tuberculosis complex and M. leprae) [52].

4. Discussion

This study is the first to investigate mycobacteria present in rodents and insectivores collected on the farms in relation to the tuberculin reactor status of the cattle residing on these farms. The rationale for this study was that pathogens that infect more than one host species, as is the case for many pathogenic mycobacteria, are likely to be encountered in several host populations, some of which may constitute infection reservoirs [53]. However, this means that the presence of infection in a wild animal population does not prove that the animal species is a reservoir of the infectious agent [4]. To get more information on the possible reservoir status of a certain host, the data of the presence of infection in that host should, therefore, be analysed in relation to data of infections in the target population. In this respect, it is important to acknowledge the existence of different host types; that is, a maintenance host, in which infection can persist by intraspecies transmission alone, and a spillover host, in which infection will not persist indefinitely unless there is reinfection from another species. Both maintenance and spillover hosts may transmit infection to other species, but this difference is important when control of a host species is considered [4].

In general, rodents and insectivores can come into contact with mycobacteria through the environment by feeding, contact with soil, and contact with the feces of wild and domestic animals or humans. These mycobacteria can pass through the stomach of these animals without being digested, since they are resistant to acid. Pathogenic and opportunistic mycobacteria can pass through the stomach and can survive in tissues and organs. In this way, they can be spread over long distances with the migration of these animals [27] and even if they are not part of the maintenance reservoir, they can play a role as transport host.

4.1. No Evidence for Rodents and Insectivores as Reservoir Hosts for M. bovis or M. avium Subsp. Paratuberculosis

In previous studies in the UK and New Zealand, the prevalences of M. bovis in rodents and insectivores ranged from 0.4 to 2.8% and from 1.2 to 5%, respectively [20, 29, 34, 35, 54]. M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis was also found previously in rodents and insectivores in the Czech Republic and Greece at prevalences ranging from 1.3%, to 5.9% and from 1.7% to 2.6%, respectively [55, 56].

In the present study, rodents and insectivores were collected on cattle farms, some of which housed cattle infected with M. bovis and/or atypical mycobacterioses [14]. Although we have not detected M. bovis or M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis in the small mammals trapped on the cattle farms in Morogoro, African rodents or insectivores could still be a reservoir for these mycobacteria. As it has been the case in previous studies [20], for some species, not enough animals were trapped to definitely conclude that they do not carry M. bovis or M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis, as shown by the wide confidence intervals of the zero estimates for some species in Table 2. Moreover, although we have used different types and sizes of traps, some species of rodents and insectivores will not be caught in these traps because of their size. For example, most of the shrews species are too small to trigger the traps used in this study. Therefore, we could have missed some crucial species.

For the two species trapped in significant numbers, namely, R. rattus and M. natalensis, the confidence intervals show that they do not play a significant role as carriers of M. bovis or M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis in the studied area. A closely related species of R. rattus, R. norvegicus, is experimentally not sensitive to infection with M. bovis [32] although it has been found to carry M. bovis in the UK [34, 35] but at low prevalences (1.2–2.2%).

4.2. Rodents and Insectivores as Hosts for Other Mycobacteria

Tuberculin tests in cattle have revealed a high prevalence of atypical mycobacterioses in Tanzanian cattle [14]. Atypical mycobacteria, such as M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis, can also have an effect on the cattle farm production [5], providing an economic incentive to prevent them in cattle. Therefore, all rodent and insectivore samples collected in the present study were also analyzed for the presence of atypical mycobacteria.

Analysis of the prevalences of mycobacteria in rodents and insectivores in relation to the reactor status of the farm on which the small mammals were collected gave us an indication on whether transmission between small mammals and cattle would be possible, or if another source of infection would have to be involved.

4.2.1. Rodents

For M. natalensis there was no difference in the prevalence of mycobacteria between the different farm types for the present, future, and past reactor status. Another source of infection should thus be available for cattle and M. natalensis to become infected with mycobacteria. This other source could be another wild or domestic animal, the environment, or humans.

Some of the isolated mycobacteria, namely, M. chelonae, M. intracellulare, and M. szulgai, are known pathogens to humans, causing pulmonary disease, soft skin, or disseminated infections in immunocompetent (M. intracellulare), immunocompromized, or predisposed patients (M. chelonae and M. szulgai) [52]. Their impact on the health of cattle or on their milk production is not clear, however, although they have been isolated from cattle in several studies [14, 57, 58]. Most of the mycobacteria detected in M. natalensis were detected in the lung or mesenteric lymph nodes, so they may potentially be excreted by the animals through feces or respiratory secretions. In the present study, no fecal specimens were examined, but we have shown in Benin that 15.5% of small mammal's feces contain mycobacteria [26].

For R. rattus, the detection rate of mycobacteria is low (2.8%), with no mycobacteria belonging to human risk group 2 (Table 3) and, similarly to M. natalensis, no difference between farm types. However, interestingly, M. nonchromogenicum and M. goodii were first detected in 2005 in R. rattus trapped on a farm and were later detected in 2006 in the milk of cattle residing on the same farm (Tables 3 and 6). This could mean that R. rattus excretes these mycobacteria, for example, as a transport host, that these mycobacteria are conserved very well in the environment or that these mycobacteria are maintained in another domestic or wildlife host, from which cattle and R. rattus can pick up the mycobacteria as spill-over hosts. For M. nonchromogenicum, the source of infection is probably the environment [52]. The status and natural reservoir of M. goodii, however, is not yet clear, but it causes infections in both humans [59] and wildlife [60].

In accordance with a previous study [21], the highest prevalence of mycobacteria was found in C. gambianus (23.9%) as compared to the other rodents, with M. intracellulare and related mycobacteria as main mycobacteria found in this species. The difference in prevalence of mycobacteria in this animal species between reacting and nonreacting farms was not significant, possibly because of the low number of C. gambianus trapped in these cattle farms (n = 12). The elevated prevalence may indicate a potential risk to humans, since most of the infected animals were trapped in or near human dwellings in Mwembesongo.

The large difference in prevalences between the different rodent species might be due to different behavior, habitat, and food preference. Table 7 summarizes the habitat and food preference of the main animal species trapped in this study. Although their habitat ranges differ, they were all collected in the same environment around cattle farms and human dwellings. M. natalensis, R. rattus, and C. gambianus are all omnivorous and will eat whatever they will find in a human-created environment. The main difference is that C. gambianus use their cheek pouches to carry food and bedding material and that they regularly perform coprophagy [61]; in that way, they can have more frequent encounters with mycobacteria.

Table 7.

Habitat and food preference of the main animals species collected according to Nowak [61].

| Animal species | Habitat | Food preference |

|---|---|---|

| C. gambianus | Forests, and villages | Vegetables, insects, crabs, snails, palm fruits, and palm kernels Regular coprophagy They use their cheek pouches to carry food and store large amounts of food in their shelters |

| C. hirta | Damp and dry forests, grasslands Cultivated areas Occasionally human settlements and buildings |

Invertebrates Bodies of freshly killed animals (including frogs, toads and lizards) Regular coprophagy |

| M. natalensis | Savannah Cultivated and abandoned fields Buildings and villages |

Mainly grass and other seeds, insects when available Everything that people eat when available |

| R. rattus | Cities, villages Cultivated fields some natural habitats |

Variety of plants and animal matter: seeds, grains, nuts, vegetables, fruits Everything that people eat |

4.2.2. Insectivores

A difference in prevalence of mycobacteria between rodents and insectivores was also observed similar to a previous study [21]. This difference was only observed in reacting farms and not in nonreacting farms. Insectivores probably pick up mycobacteria from the environment through their scavenging behaviour [27]. Their coprophagy and feeding on freshly killed animals (Table 7) are possible explanations for the elevated prevalence. A difference was also found in the mycobacterial prevalences in these animals between reacting and nonreacting farms: For the current reactor status, a higher prevalence was observed in the reacting as compared to the nonreacting farms, which is an argument for a common source of infection for insectivores and cattle. For the past reactor status, a higher prevalence was observed in the nonreacting as compared to the reacting farms, also indicating that cattle are probably not the source of infection for insectivores.

Most of the mycobacteria found in the insectivore C. hirta were potentially pathogenic for humans (Table 3), most of which were part of the M. avium-complex (M. intracellulare, M. chimaera, and M. colombiense) [52].

The other insectivores collected in this study, the hedgehogs, are also known carriers of pathogenic mycobacteria [29, 62, 63] although only European hedgehogs have been studied in this context. In the present study, 2 out of 4 hedgehogs (A. albiventris) carried mycobacteria, but those mycobacteria are probably not pathogenic.

4.2.3. Organs

In general, the lung was the most prone to contain mycobacteria, followed by the mesenteric lymph nodes, the spleen, and the liver. This is consistent with transmission of mycobacteria through aerosols and through digestion. In two cases, mycobacteria were cultured from lesions: M. terrae from a swollen foot of R. rattus and a mycobacterium related to M. intracellulare from a swollen lymph node of C. gambianus. In the other animals presenting mycobacteria, no macroscopic pathomorphological lesions were observed and for most of the isolates only one colony was observed in culture, suggesting colonization rather than infection.

As mycobacteria were found in all four organs, and considering what is currently known about transmission of diseases by rodents and of diseases in general [64], several ways of transmission of mycobacteria are possible: through direct contact with rodent excreta, through ingestion of food or water contaminated with rodent excreta, through ingestion of the animal itself, through inhaling aerosolized rodent excreta, through rodent bites, or through ectoparasites.

4.3. Pool Screening Approach

The study used the pooled screening approach to save time and resources when analyzing the specimens. We have shown that although there is a slight underestimation of the prevalence when pool screening is used for mycobacterial detection, the 95% confidence intervals are as wide as with individual screening. This has been previously reported by Vansteelandt et al. [65] for viral detection. As the pooling was done in a stratified way, per habitat, per organ and per species, there was no loss of information since several hypotheses could still be tested. If pooling would have been done in a different way, for example, pooling all organs from the same animal as has been done by some researchers [20, 66], we would have lost information, about the site of infection or colonization. Therefore, we strongly recommend the stratified pool screening method in mycobacterial reservoir research.

4.4. PCR versus Culture for Detection of Mycobacteria

For only seven pools, PCR and culture results were consistent. This probably is due to a difference in sensitivity of the methods [67]: for detection of M. tuberculosis in clinical samples, PCR is less sensitive than culture [68]. This is also true for mycobacteria in general. Although a specific 16S rDNA PCR is very useful to detect mycobacteria in different samples, it is not as sensitive as culture, because of the fact that its target only occurs once or twice in the mycobacterial chromosome [69]. Indeed, five of the eight pools from which more than one colony grew in culture, were also positive for PCR (see Supplementary Table S1 that could be found at doi: 10.4061/2011/495074).

A second reason for the inconsistency is the fact that the methods target other mycobacteria; for example, not all mycobacteria grow at the temperature in which the inoculated media are kept [52], while PCR targets also the DNA of dead mycobacteria (killed either by the immune system of the animal, during the transport or storage, or during the decontamination) [70]. This inconsistency has been shown and discussed in previous studies as well [21, 26].

4.5. Risk of Transmission of Mycobacteria from Small Mammals to Humans

Little is known about the prevalence of atypical mycobacterioses in the human population in Tanzania. However, Kazwala et al. [71] reported that 16% of the mycobacterial isolates from extrapulmonary human samples in Tanzania were M. bovis and 13.6% were atypical mycobacteria, whereas Mfinanga et al. [72] demonstrated that 10.8% of mycobacterial isolates from extrapulmonary human samples were M. bovis and 47.7% were atypical mycobacteria. This shows that although few data are available, human cases of both BTB and atypical mycobacterial disease are present in Tanzania. Recently, three additional cases of invasive atypical mycobacterial disease in HIV-positive patients in Tanzania were described caused by M. sherrisii and M. avium-complex [73]. At ITM, we have records of M. intracellulare, M. terrae, M. arupense, M. colombiense, and M. kumamotonense isolated from clinical samples in Tanzania although the clinical significance of these mycobacterial isolates is not known. Of the mycobacteria isolated in humans, M. intracellulare, M. colombiense, and M. terrae were detected in small mammals in the present study. In a previous study in the same region in Tanzania, we detected also M. intracellulare and M. arupense [21]. Although the HIV prevalence has been decreasing slowly in Tanzania, it still reached 6.2% and 6% in 2005 and 2006, respectively [74]. In 2009, the HIV prevalence has decreased to 5.6%, but this still means that a substantial proportion of the Tanzanian population is more sensitive to infections with these atypical mycobacteria. All rodents and insectivores in the present study were collected in close proximity to human dwellings, which means that infected animals could pose a risk to humans with a lowered immune system.

5. Conclusion

The present study is the first to investigate the presence of mycobacteria in rodents and insectivores in relation to the reactor status of the cattle farms on which they were collected. Analysis of the presence of mycobacteria in relation to the reactor status of the cattle farms does not exclude transmission between small mammals and cattle but indicates that transmission to cattle from another source of infection is more likely. However, because of the high prevalence of potentially pathogenic mycobacteria in some small mammal species, namely, in C. gambianus and C. hirta, the infected animals can pose a risk to humans, especially in areas with a high HIV-prevalence as is the case in Tanzania.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table S1: Additional information on mycobacteria detected in rodents and insectivores in and around Morogoro, Tanzania: animal species, trapping site, reactor status, organ, and number of colonies detected.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a Ph.D. grant of the Flemish Interuniversity Council, the Directorate General for Development Cooperation (Brussels, Belgium), the Damien Foundation, and the European Union (Ratzooman Project, INCO-Dev ICA-CT-2002-10056). The authors thank Krista Fissette, Pim De Rijk, and Nele Boeykens for their excellent technical assistance and the staff of SUA Pest Management Centre and the SUA Department of Veterinary Medicine and Public Health for their support during the field work.

References

- 1.Euzéby JP. List of Prokaryotic names with standing in nomenclature— Genus Mycobacterium. 2009.

- 2.Tortoli E. The new mycobacteria: an update. FEMS Immunology and Medical Microbiology. 2006;48(2):159–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2006.00123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collins FM. Mycobacterial disease, immunosuppression, and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 1989;2(4):360–377. doi: 10.1128/cmr.2.4.360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corner LA. The role of wild animal populations in the epidemiology of tuberculosis in domestic animals: how to assess the risk. Veterinary Microbiology. 2006;112(2–4):303–312. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2005.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hendrick SH, Kelton DF, Leslie KE, Lissemore KD, Archambault M, Duffield TF. Effect of paratuberculosis on culling, milk production, and milk quality in dairy herds. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2005;227(8):1302–1308. doi: 10.2460/javma.2005.227.1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kazwala RR. Molecular epidemiology of bovine tuberculosis in Tanzania. University of Edinburgh; 1996. Ph.D. thesis. [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Lisle GW, Mackintosh CG, Bengis RG. Mycobacterium bovis in free-living and captive wildlife, including farmed deer. Revue Scientifique et Technique. 2001;20(1):86–111. doi: 10.20506/rst.20.1.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bengis RG, Kriek NP, Keet DF, Raath JP, de Vos V, Huchzermeyer HF. An outbreak of bovine tuberculosis in a free-living African buffalo (Syncerus caffer-Sparrman) population in the Kruger National Park: a preliminary report. Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research. 1996;63(1):15–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drewe JA, Foote AK, Sutcliffe RL, Pearce GP. Pathology of Mycobacterium bovis infection in wild meerkats (Suricata suricatta) Journal of Comparative Pathology. 2009;140(1):12–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keet DF, Kriek NP, Penrith ML, Michel A, Huchzermeyer H. Tuberculosis in buffaloes (Synecrus caffer) in the Kruger National Park: spread of the diseases to other species. Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research. 1996;63(3):239–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirberger RM, Keet DF, Wagner WM. Radiologic abnormalities of the appendicular skeleton of the lion (Panthera leo): incidental findings and Mycobacterium bovis-induced changes. Veterinary Radiology and Ultrasound. 2006;47(2):145–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.2006.00121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cleaveland S, Mlengeya T, Kazwala RR, et al. Tuberculosis in Tanzanian wildlife. Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 2005;41(2):446–453. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-41.2.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cleaveland S, Shaw DJ, Mfinanga SG, et al. Mycobacterium bovis in rural Tanzania: risk factors for infection in human and cattle populations. Tuberculosis. 2007;87(1):30–43. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Durnez L, Sadiki H, Katakweba A, et al. The prevalence of Mycobacterium bovis-infection and atypical mycobacterioses in cattle in and around Morogoro, Tanzania. Tropical Animal Health and Production. 2009;41(8):1653–1659. doi: 10.1007/s11250-009-9361-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiwa SF, Kazwala RR, Aboud AA, Kalaye WJ. Bovine tuberculosis in the Lake Victoria zone of Tanzania and its possible consequences for human health in the HIV/AIDS era. Veterinary Research Communications. 1997;21(8):533–539. doi: 10.1023/a:1005900929479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mdegela RH, Kusiluka LJ, Kapaga AM, et al. Prevalence and determinants of mastitis and milk-borne zoonoses in smallholder dairy farming sector in Kibaha and Morogoro districts in Eastern Tanzania. Journal of Veterinary Medicine Series B. 2004;51(3):123–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0450.2004.00735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shirima GM, Kazwala RR, Kambarage DM. Prevalence of bovine tuberculosis in cattle in different farming systems in the eastern zone of Tanzania. Preventive Veterinary Medicine. 2003;57(3):167–172. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5877(02)00214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bercovier H, Vincent V. Mycobacterial infections in domestic and wild animals due to Mycobacterium marinum, M. fortuitum, M. chelonae, M. porcinum, M. farcinogenes, M. smegmatis, M. scrofulaceum, M. xenopi, M. kansasii, M. simiae and M. genavense. Revue Scientifique et Technique. 2001;20(1):265–290. doi: 10.20506/rst.20.1.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cavanagh R, Begon M, Bennett M, et al. Mycobacterium microti infection (vole tuberculosis) in wild rodent populations. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2002;40(9):3281–3285. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.9.3281-3285.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Delahay RJ, Smith GC, Barlow AM, et al. Bovine tuberculosis infection in wild mammals in the South-West region of England: a survey of prevalence and a semi-quantitative assessment of the relative risks to cattle. Veterinary Journal. 2007;173(2):287–301. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2005.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Durnez L, Eddyani M, Mgode GF, et al. First detection of mycobacteria in African rodents and insectivores, using stratified pool screening. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2008;74(3):768–773. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01193-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ayele WY, Neill SD, Zinsstag J, Weiss MG, Pavlik I. Bovine tuberculosis: an old disease but a new threat to Africa. International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2004;8(8):924–937. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Foudraine NA, van Soolingen D, Noordhoek GT, Reiss P. Pulmonary tuberculosis due to Mycobacterium microti in a human immunodeficiency virus-infected patient. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 1998;27(6):1543–1544. doi: 10.1086/517747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Biet F, Boschiroli ML, Thorel MF, Guilloteau LA. Zoonotic aspects of Mycobacterium bovis and Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex (MAC) Veterinary Research. 2005;36(3):411–436. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2005001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cavanagh RD, Lambin X, Ergon T, et al. Disease dynamics in cyclic populations of field voles (Microtus agrestis): cowpox virus and vole tuberculosis (Mycobacterium microti) Proceedings of the Royal Society—Biological Sciences. 2004;271(1541):859–867. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2003.2667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Durnez L, Suykerbuyk P, Nicolas V, et al. Terrestrial small mammals as reservoirs of Mycobacterium ulcerans in benin. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2010;76(13):4574–4577. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00199-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fischer O, Mátlová L, Bartl J, Dvorská L, Melichárek I, Pavlík I. Findings of mycobacteria in insectivores and small rodents. Folia Microbiologica. 2000;45(2):147–152. doi: 10.1007/BF02817414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gratz NG. Rodents and human disease: a global appreciation. In: Prakash I, editor. Rodent Pest Management. Boca Raton, Fla, USA: CRC Press; 1988. pp. 101–169. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lugton IW, Johnstone AC, Morris RS. Mycobacterium bovis infection in New Zealand hedgehogs (Erinaceus europaeus) New Zealand Veterinary Journal. 1995;43:342–345. doi: 10.1080/00480169./1995.35917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gratz NG. The burden of rodent-borne diseases in Africa south of the Sahara. Belgian Journal of Zoology. 1997;127:71–84. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meerburg BG. Zoonotic risks of rodents in livestock production. University of Amsterdam; 2006. Ph.D. thesis. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clarke KA, Fitzgerald SD, Zwick LS, et al. Experimental inoculation of meadow voles (Microtus pennsylvanicus), house mice (Mus musculus), and Norway rats (Rattus norvegicus) with Mycobacterium bovis. Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 2007;43(3):353–365. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-43.3.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Collins P, Matthews PR, McDiarmid A, Brown A. The pathogenicity of Mycobacterium avium and related mycobacteria for experimental animals. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 1983;16(1):27–35. doi: 10.1099/00222615-16-1-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bosworth TJ. Further observations on the wild rat as a carrier of Brucella abortus. Journal of Comparative Pathology and Therapeutics. 1940;53:42–49. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Little TW, Swan C, Thompson HV, Wilesmith JW. Bovine tuberculosis in domestic and wild mammals in an area of Dorset. III. The prevalence of tuberculosis in mammals other than badgers and cattle. Journal of Hygiene. 1982;89(2):225–234. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400070753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Delahay RJ, De Leeuw AN, Barlow AM, Clifton-Hadley RS, Cheeseman CL. The status of Mycobacterium bovis infection in UK wild mammals: a review. Veterinary Journal. 2002;164(2):90–105. doi: 10.1053/tvjl.2001.0667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hope JC, Thom ML, Villarreal-Ramos B, Vordermeier HM, Hewinson RG, Howard CJ. Exposure to Mycobacterium avium induces low-level protection from Mycobacterium bovis infection but compromises diagnosis of disease in cattle. Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 2005;141(3):432–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02882.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thoen CO, Ebel ED. Diagnostic tests for bovine tuberculosis. In: Thoen CO, Steele JH, Gilsdorf MJ, editors. Mycobacterium Bovis. Ames, Iowa, USA: Blackwell; 2006. pp. 49–53. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rieder HL, Chonde TM, Myking H, et al. The Public Health Service National Tuberculosis Reference Laboratory and the National Laboratory Network. Paris, France: International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Portaels F, De Muynck A, Sylla MP. Selective isolation of mycobacteria from soil: a statistical analysis approach. Journal of General Microbiology. 1988;134(3):849–855. doi: 10.1099/00221287-134-3-849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mangiapan G, Vokurka M, Schouls L, et al. Sequence capture-PCR improves detection of mycobacterial DNA in clinical specimens. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1996;34(5):1209–1215. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.5.1209-1215.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Levy-Frebault VV, Portaels F. Proposed minimal standards for the genus Mycobacterium and for description of new slowly growing Mycobacterium species. International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology. 1992;42(2):315–323. doi: 10.1099/00207713-42-2-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barker JT. Statistical estimators of infection potential based on PCR pool screening with unequal pool sizes. Birmingham, UK: University of Alabama; 2000. Ph.D. thesis. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chiang CL, Reeves WC. Statistical estimation of virus infection rates in mosquito vector populations. American Journal of Hygiene. 1962;75:377–391. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dorfman R. The detection of defective members in large populations. Annals of Mathematical Statistics. 1943:436–440. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Katholi CR, Toe L, Merriweather A, Unnasch TR. Determining the prevalence of Onchocerca volvulus infection in vector populations by polymerase chain reaction screening of pools of black flies. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1995;172(5):1414–1417. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.5.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Katholi CR, Unnasch TR. Important experimental parameters for determining infection rates in arthropod vectors using pool screening approaches. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2006;74(5):779–785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Casella. Statistical Inference. Pacific Grove, Calif, USA: Duxbury; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dai YH, Schittkowski K. A sequential quadratic programming algorithm with non-monotone line search. Pacific Journal of Optimization. 2008;4:335–351. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schittkowski K. NLPQL: a fortran subroutine solving constrained nonlinear programming problems. Annals of Operations Research. 1986;5:485–500. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schittkowski K. Department of Computer Science, University of Bayreuth; 2006. NLPQLP: a fortran implementation of a sequential quadratic programming algorithm with distributed and non-monotone line search—user's guide, version 2.2. Tech. Rep. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Leão SC, Martin A, Mejia GI, et al. Practical handbook for the phenotypic and genotypic identification of mycobacteria. With the financial support of INCO, DEV and CA, 2004.

- 53.Haydon DT, Cleaveland S, Taylor LH, Laurenson MK. Identifying reservoirs of infection: a conceptual and practical challenge. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2002;8(12):1468–1473. doi: 10.3201/eid0812.010317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Delahay RJ, Cheeseman CL, Clifton-Hadley RS. Wildlife disease reservoirs: the epidemiology of Mycobacterium bovis infection in the European badger (Meles meles) and other British mammals. Tuberculosis. 2001;81:43–49. doi: 10.1054/tube.2000.0266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Florou M, Leontides L, Kostoulas P, et al. Isolation of Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis from non-ruminant wildlife living in the sheds and on the pastures of Greek sheep and goats. Epidemiology and Infection. 2008;136(5):644–652. doi: 10.1017/S095026880700893X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kopecna M, Trcka I, Lamka J, et al. The wildlife hosts of Mycobacterium avium subsp paratuberculosis in the Czech Republic during the years 2002–2007. Veterinarni Medicina. 2008;53(8):420–426. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dvorska L, Matlova L, Bartos M, et al. Study of Mycobacterium avium complex strains isolated from cattle in the Czech Republic between 1996 and 2000. Veterinary Microbiology. 2004;99(3-4):239–250. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thorel MF, Huchzermeyer HF, Michel AL. Mycobacterium avium and Mycobacterium intracellulare infection in mammals. Revue Scientifique et Technique. 2001;20(1):204–218. doi: 10.20506/rst.20.1.1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Katoch VM. Infections due to non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) Indian Journal of Medical Research. 2004;120(4):290–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.van Helden PD, Gey van Pittius NC, Warren RM, et al. Pulmonary infection due to Mycobacterium goodii in a spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta) from South Africa. Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 2008;44(1):151–154. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-44.1.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nowak RM. Walker's Mammals of the World. 6th edition. 1-2. Baltimore, Md, USA: The John Hopkins University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tappe JP, Weitzman I, Liu S, Dolensek EP, Karp D. Systemic Mycobacterium marinum infection in a European hedgehog. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 1983;183(11):1280–1281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Windsor RS, Durrant DS, Burn KJ. Avian tuberculosis in pigs: Mycobacterium intracellulare infection in a breeding herd. Veterinary Record. 1984;114(20):497–500. doi: 10.1136/vr.114.20.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shakespeare M. Zoonoses. London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vansteelandt S, Goetghebeur E, Verstraeten T. Regression models for disease prevalence with diagnostic tests on pools of serum samples. Biometrics. 2000;56(4):1126–1133. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.01126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.de Lisle GW, Yates GF, Caley P, Corboy RJ. Surveillance of wildlife for Mycobacterium bovis infection using culture of pooled tissue samples from ferrets (Mustela furo) New Zealand Veterinary Journal. 2005;53(1):14–18. doi: 10.1080/00480169.2005.36463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pfaller MA. Application of new technology to the detection, identification, and antimicrobial susceptibility testing of mycobacteria. American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 1994;101(3):329–337. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/101.3.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ling DI, Flores LL, Riley LW, Pai M. Commercial nucleic-acid amplification tests for diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis in respiratory specimens: meta-analysils and meta-regression. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001536. Article ID e1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fogel GB, Collins CR, Li J, Brunk CF. Prokaryotic genome size and SSU rDNA copy number: estimation of microbial relative abundance from a mixed population. Microbial Ecology. 1999;38(2):93–113. doi: 10.1007/s002489900162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fukushima R, Kawakami S, Iinuma H, Okinaga K. Molecular diagnosis of infectious disease. Nippon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 2003;104(7):518–522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kazwala RR, Daborn CJ, Sharp JM, Kambarage DM, Jiwa SF, Mbembati NA. Isolation of Mycobacterium bovis from human cases of cervical adenitis in Tanzania: a cause for concern? International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2001;5(1):87–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mfinanga SG, Morkve O, Kazwala RR, et al. Mycobacterial adenitis: role of Mycobacterium bovis, non-tuberculous mycobacteria, HIV infection, and risk factors in Arusha, Tanzania. East African Medical Journal. 2004;81(4):171–178. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v81i4.9150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Crump JA, van Ingen J, Morrissey AB, et al. Invasive disease caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria, Tanzania. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2009;15(1):53–55. doi: 10.3201/eid1501.081093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.WHO. Global Health Observatory Database, 2011.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table S1: Additional information on mycobacteria detected in rodents and insectivores in and around Morogoro, Tanzania: animal species, trapping site, reactor status, organ, and number of colonies detected.