Abstract

We examined the impact of setting characteristics and presentation effects on engagement with stimuli in a group of 193 nursing home residents with dementia (recruited from a total of seven nursing homes). Engagement was assessed through systematic observations using the Observational Measurement of Engagement (OME), and data pertaining to setting characteristics (background noise, light, and number of persons in proximity) were recorded via the environmental portion of the Agitation Behavior Mapping Inventory (ABMI; Cohen-Mansfield, Werner, & Marx, (1989). An observational study of agitation in agitated nursing home residents. International Psychogeriatrics, 1, 153–165). Results revealed that study participants were engaged more often with moderate levels of sound and in the presence of a small group of people (from four to nine people). As to the presentation effects, multiple presentations of the same stimulus were found to be appropriate for the severely impaired as well as the moderately cognitively impaired. Moreover, modeling of the appropriate behavior significantly increased engagement, with the severely cognitively impaired residents receiving the greatest benefit from modeling. These findings have direct implications for the way in which caregivers could structure the environment in the nursing home and how they could present stimuli to residents in order to optimize engagement in persons with dementia.

Keywords: engagement, dementia, setting characteristics, nursing home, activities

Introduction

Nursing home facilities are required to provide activities for their residents, but these often occupy only relatively short periods of time during the day (Burgio et al., 1994; Cohen-Mansfield, Marx, & Werner, 1992; van Haitsma et al., 1997) and are infrequently restricted to group activities that are not appropriate for some ability levels (Buettner & Fitzsimmons, 2003; Conroy, Fincham, & Agard-Evans, 1988). Indeed, studies have found that nursing home residents with dementia spend the majority of their time engaged in no activity at all, with unstructured time accounting for two-thirds of the day or more (Burgio et al., 1994; Cohen-Mansfield et al., 1992; Lucero, Pearson, Hutchinson, Leger-Krall, & Rinalducci, 2001). Engagement is defined as motor or verbal behaviors in response to activity (Orsulic-Jeras, Judge, & Camp, 2000). It is important to find activities that are appropriate for all residents, regardless of the level of dementia, and are sufficiently engaging during periods of boredom. It has been shown that engagement in activities can have positive effects on persons with dementia, such as a marked increase in measured happiness, elevated interest and alertness, a decrease in boredom (Baker et al., 2001; Kovach & Henschel, 1996; Schreiner, Yamamoto, & Shiotani, 2005), improvement in the performance of activities of daily living (ADL; Schnelle, MacRae, Ouslander, Simmons, & Nitta, 1995) and higher quality of life (Schreiner et al., 2005). The increase in positive affect due to engagement can subsequently reduce agitation in this population (Buettner, 1999; Cohen-Mansfield & Werner, 1997). The individual pathways to engage a person with dementia need to be examined to construct a suitable schedule of activities and an optimal environment.

There is a paucity of research examining the impact of stimuli and environmental attributes on engagement of persons with dementia. Much of the relevant existing literature did not use controlled intervention trials, but the findings nonetheless suggest possible factors affecting engagement that should be researched further. One under-researched factor that may affect successful engagement in persons with dementia is the impact of aspects of the surrounding environment. However, the majority of studies examining environmental modifications focused on their effects on general behavior in persons with dementia and was not specific to engagement. Furthermore, a qualitative synthesis of research findings on the effects of environmental characteristics on persons with dementia in nursing homes reported that the majority of studies were methodologically flawed and involved small samples (Gitlin, Liebman, & Winter, 2003). These limitations are important to consider, although existing research suggests that there could be a relationship between setting characteristics and negative behaviors and engagement, and that persons with dementia may benefit from specific environmental modifications, which generally included either ambiance changing interventions or interventions affecting specific environmental attributes, such as signage, for specific objectives.

As to ambiance changing interventions, researchers found that enhancing the nursing home environment (e.g., by simulating a home or outdoor environment) resulted in higher levels of pleasure as well as a trend toward less trespassing, exit seeking, and other agitated behaviors in the altered environments, as compared with the unit’s usual décor (Cohen-Mansfield & Werner, 1998). The administration of preferred music during bathing significantly reduced hitting and total number of aggressive behaviors in persons with dementia who had a history of aggression during bathing episodes (Clark, Lipe, & Bilbrey, 1998). In a correlational study, Zeisel et al. (2003) found that privacy and personalization in bedrooms, residential character, and an ambient environment that residents can understand were associated with both reduced aggressive and agitated behavior and fewer psychological problems. In addition, common areas that vary in ambiance and exit doors that are camouflaged were associated with a reduction in depression, social withdrawal, misidentification, and hallucinations. However, this was not an interventional study, limiting the conclusions regarding the impact of the environmental attributes.

Environmental modifications that addressed one aspect of the environment included camouflaging of doors and increasing the visibility of the toilet. A wall mural painted over an exit door resulted in a significant decrease in door-testing behavior (Kincaid & Peacock, 2003). Another successful environmental modification was increasing toilet visibility in nursing homes to remind residents to use them, which had an eight-fold impact on toilet usage (Namazi & Johnson, 1991). Furthermore, the use of specially designed exterior environments (e.g., those that allowed residents greater freedom of movement) reduced incidents of aggressive behavior (Mooney & Nicell, 1992).

Environmental modifications can also be useful in compensating for functional deficits in persons with dementia. For example, nursing home residents often have impairments such as reduced vision (Mendez, Cherrier, & Meadows, 1996; Marx, Werner, Feldman, & Cohen-Mansfield, 1997) and hearing loss (Cohen-Mansfield & Taylor, 2004), which can compromise their ability to participate in activities requiring certain levels of noise and light for optimal engagement. Furthermore, Resnick, Fries, and Verbrugge (1997) reported that increased visual impairment as well as moderate-to-severe hearing impairment in nursing home residents was associated with decreasing levels of social engagement as well as time spent in nursing home activities. Sensory impairment has been found to reduce both participation in leisure activities and performance of ADL and instrumental ADL (Branch, Horowitz, & Carr, 1989; Horowitz, 1994; Marx et al., 1992). Environmental conditions are important in that they can magnify such impairments, such as a combination of reduced vision with insufficient lighting. However, Belleville, Rouleau, van der Linden, and Collette (2003) found that persons with dementia were comparable to control participants with respect to ability to resist auditory distractions. Moreover, research has found that persons with dementia recall answers better when there is some room noise versus none and when there is music playing versus other background noise (Foster & Valentine, 2001).

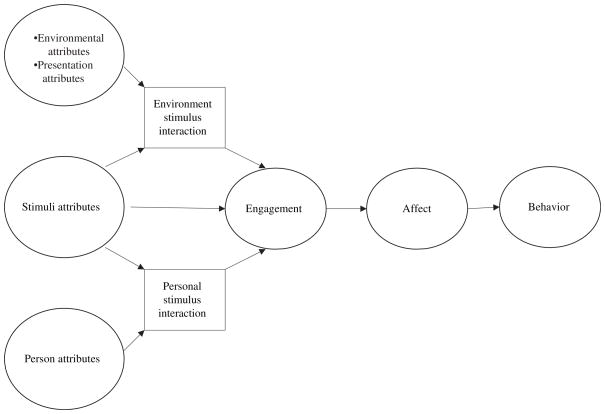

In examining the concept of engagement in persons with dementia, we have developed a theoretical framework, the Comprehensive Process Model of Engagement (Cohen-Mansfield, Dakheel-Ali, & Marx, 2009a; Figure 1), which posits that a combination of stimulus attributes, personal attributes, setting/environmental characteristics and their interactions affect engagement. Environmental attributes refer to those elements in the person’s environment that may influence his or her level of attention to the stimulus presented, including the location in which a stimulus is presented, the number of persons present, temperature, noise level, amount of light, and time of day. Such attributes may capture the degree of likely interference with the stimulus and the degree to which the setting characteristics will be conducive to focusing on the stimulus. Personal attributes are the various characteristics of the person with dementia that are likely to impact engagement with a stimulus, including cognitive function, demographic characteristics, and general activity and energy level. Stimulus attributes that may affect the level of engagement include the degree to which the stimulus has social qualities, the degree to which it is manipulative, such as in the opportunity to arrange wooden blocks, or the degree to which it emulates a work role, such as a task of folding towels or sorting envelopes.

Figure 1.

The Comprehensive Process Model of Engagement. Reprinted with permission from Cohen-Mansfield, J., Dakheel- Ali, M., & Marx, M.S. (2009a). Engagement in persons with dementia: The concept and its measurement. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 17(4), 299–307.

While this article focuses on the impact of environmental variables, other articles have demonstrated the impact of personal attributes. Studies have shown decreased involvement with activities for residents with lower cognitive functioning (Cohen-Mansfield, Marx, Regier, & Dakheel-Ali, 2009b; Kolanowski, Buettner, & Litaker, 2006) and with greater ADL impairment (Voelkl et al., 1995). Stimulus–person interaction is demonstrated in research that has shown that information on a person with dementia’s past preferences and premorbid personality can be effectively used in the design of intervention activities (Cohen-Mansfield et al., in press; Kolanowski, Buettner, Costa, & Litaker, 2001; Kolanowski & Richards, 2002).

In this article, we focus on the impact of setting and environmental characteristics on engagement. It is likely that certain stimuli may be more affected by specific setting characteristics than others. Music, for example, is more likely to be affected by setting noise and less likely to be affected by modeling, whereas the reverse is likely to occur for blocks. The focus of this article is guided by the Environmental Press Theory (Lawton, 1985), which asserts that because of diminishing resources, persons with dementia will be more dependent on environmental conditions than persons with intact cognition. Therefore, we need to determine how environmental conditions affect persons with dementia, and additionally, we would expect persons with severe dementia to be more affected than those with mild dementia. In this article, we present data pertaining to one aspect of the Comprehensive Process Model of Engagement; the environmental and presentation effects of activity stimuli, and specifically ask if stimulus modeling, order of presentation, time of day, day of presentation, and setting characteristics impact the duration and quality of engagement. Our hypotheses are presented in the following sections.

Presentation

Modeling

Evidence of the importance of modeling suggests that participants would benefit from the researchers modeling the performance of a behavior with respect to manipulation of the stimuli (Rosenthal & Bandura, 1978). However, that benefit will be more pronounced for participants with very low levels of cognitive function because, on the basis of the environmental press theory and the importance of matching stimuli to the level of cognitive functioning, it is likely that persons with relatively high levels of cognitive function should be able to use the stimuli regardless of modeling, whereas modeling may facilitate memory retrieval in persons with more advanced dementia.

Order of presentation

Participants will be more engaged following the initial presentation of a stimulus compared to the second presentation, because of the innovative quality of a first presentation. Those with higher cognitive abilities would be more likely to remember the stimuli.

Timing

Time of day

Participants will perform better in the morning when they are less fatigued. This hypothesis is based on previous findings (Burgio, Scilley, Hardin, & Hsu, 2001; Cohen-Mansfield, 2007; McCann, Gilley, Bienias, Beckett, & Evans, 2004), which identified peak agitation hours and disruptive behaviors for nursing home residents as occurring later in the day.

Presentation on the same day versus a different day

An individual’s mood and general level of function may fluctuate each day and influence the way they process information (Mienaltowski & Blanchard-Fields, 2005). Therefore, we hypothesized that the levels of engagement to different stimuli on a particular day will be more highly correlated than levels of engagement to different stimuli across different days.

Setting characteristics

Light

Because of common vision problems, participants will benefit from bright light, and their engagement will be adversely affected by dark surroundings. Additionally, data have suggested that bright light may reduce agitation in nursing home residents with dementia (Lovell, Ancoli-Israel, & Gevirtz, 1995; Lyketsos, Lindell, Baker, & Steele, 1999).

Noise

Assuming that noise will present a distraction, we hypothesized that low levels of noise would produce the highest level of engagement. Meyer et al. (1992) reported that the number of ‘frantic and/or violent’ agitated behaviors was halved following a reduction in noise level in an Alzheimer boarding home.

Number of persons in proximity

Morgan and Stewart (1998) found that privacy reduces aggression and agitation and improves sleep. Based on this finding and the assumption that other persons will provide a distraction, we hypothesized that a setting with few or no other persons in the vicinity will be most conducive to engagement with stimuli.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 193 residents of seven Maryland nursing homes. All participants had a diagnosis of dementia. Of these, 151 participants were females (78%), and age averaged 86 years (range=60–101). The majority of participants were Caucasians (81%), and most were widowed (65%). Cognitive functioning, as assessed via the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975), averaged 7.2 (SD=6.3, range=0–23). Participant ADL was obtained via the minimum data set (MDS; Morris, Fries, & Morris, 1999), averaged 3.6 (SD=1.0, range=1–5; Scale: 1 ‘independent’ to 5 ‘complete dependence’). Out of 74 participants, 38.4% had a diagnosis of depression.

Nursing facilities

Characteristics of the seven participating nursing homes are as follows: average number of beds were 223, with a range of 102–558; the average time of licensed nursing staff per resident per day was one hour and 12 min, with a range of 57 min, one hour and 40 min; the average for CNA time per resident per day was two hours and 35 min, ranging from two hours and 10 min to three hours and 16 min. In the nursing homes where consent process information was available, 370 relatives or guardians were approached. Of them 31% did not respond, 50% consented, 9% refused, 4% of residents passed away prior to participating, and 5% were excluded because they did not fit the study inclusion criteria.

Procedure

Informed consent was obtained for all study participants from their relatives or other responsible parties. Additional information on the informed consent process is available elsewhere (Cohen-Mansfield, Kerin, Pawlson, Lipson, & Holdridge, 1988). Our main criterion for inclusion was a diagnosis of dementia (derived from either the medical chart or the attending physician). The criteria for exclusion were as follows:

The resident had an accompanying diagnosis of bipolar disorder or schizophrenia.

The resident had no dexterity movement in either hand.

The resident could not be seated in a chair or wheelchair.

The resident was younger than 60 years of age.

Short-stay residents and persons receiving hospice care were not included in the study. Data pertaining to background variables were retrieved from the residents’ charts and from the minimum data set (MDS; Morris, Hawes, Murphy, & Nonemaker, 1991), and included information about gender, age, marital status, medical information (medical conditions from which the resident suffers; a list of medications taken), and performance of ADL. The MMSE, chosen for its widespread use and easiness to understand and interpret, was administered to each participant by a trained research assistant. MMSE cut points were determined by the upper and lower thirds of the sample.

Each study participant was presented with 22 predetermined different engagement stimuli over a period of three weeks (approximately four stimuli per day). A variety of stimuli were included in the study since some stimuli may be more appropriate for certain people than for others. The stimuli were chosen based on their potential for comparisons on various dimensions such as being manipulative, social, alive, task-and-work like, etc., and are examined elsewhere (Cohen-Mansfield et al., in press). The stimuli were: a life-like doll, a stuffed animal, a childish doll, an expanding sphere, music, a tetherball, a squeeze ball, a large magazine, a fabric book, a respite video, a wallet/purse, an activity pillow, stamping envelopes, coloring with markers, towels to fold, flower arrangement, building blocks, a robotic animal, a sorting task, a puzzle, a real baby, a real pet, and two individualized stimuli (personalized according to the resident’s past and present interests). In addition, a control (no stimulus) condition was included. Each stimulus was presented twice during the study (but not on the same day), once with an explanation and demonstration of how the stimulus should be used, and once without such modeling. Engagement trials took place between 9:30 am and 12:30 pm and between 2:00 and 5:30 pm, as these are the times that residents are not usually occupied with care activities at the nursing home (e.g., meals in the dining room, bathing). Individual engagement trials were separated by an inter-trial interval of at least five minutes. The order of stimulus presentation (i.e., modeling) was randomized for each participant.

Observational measurement of engagement (OME)

OME data were recorded through direct observations using specially designed software installed on a handheld computer, the PalmOne Zire 31™. Prior to initiating an engagement trial, we recorded whether or not it was necessary to transfer the resident to another place to conduct the trial, and whether or not we interrupted the participant during another activity (e.g., a group activity, watching television, sleeping or napping). Following our introduction of the engagement stimulus, we recorded whenever the participant refused the engagement stimulus (through words or actions) as well as whether or not the participant asked for additional help and/or modeling of the appropriate usage of the stimulus. We also recorded whenever another person interrupted the engagement trial (e.g., another resident, nursing staff). Specific outcome variables on the OME are described below.

Attention to the stimulus during an engagement trial was measured on this 4-point scale: (1) not attentive, (2) somewhat attentive, (3) attentive, and (4) very attentive. Level of attention observed during most of the trial and the highest attention level during the trial was recorded. Based on high correlations suggesting these capture a single construct (Cohen-Mansfield et al., 2009a), these ratings were averaged to form a single attention variable.

Attitude to the stimulus during an engagement trial was measured on a 7-point scale: (1) very negative, (2) negative, (3) somewhat negative, (4) neutral, (5) somewhat positive, (6) positive, and (7) very positive. ‘Somewhat’ indicated a lower intensity of the attribute than the full attribute. For example, a somewhat negative attitude can be a frown and removing the stimulus after some handling, whereas a fully negative attitude can be screaming at it, hitting it or throwing it to the floor, etc. We recorded attitude to the stimulus seen during most of the trial as well as the highest rating of attitude observed during the trial. Based on high correlations suggesting that these capture a single construct (Cohen-Mansfield et al., 2009a), these ratings were averaged to form a single attitude variable.

Duration referred to the amount of time that the participant was engaged with the stimulus. This measure started after presentation of the engagement stimulus and continued for a minimum of three minutes, after which the stimulus was retrieved if the participant no longer showed interest. If the participant maintained interest in the stimulus, he or she was observed until there was no further engagement with the stimulus or up to a maximum of 15 minutes. Duration was measured in seconds.

In addition, data pertaining to setting characteristics (background noise, lighting, and number of persons in proximity) were obtained via the environment portion of the Agitation Behavior Mapping Inventory (ABMI; Cohen-Mansfield et al., 1989). The ABMI was not completed when participants refused to participate. Thus, some environmental factors were not measured for refusals, i.e., number of persons around, light, and noise.

Inter-rater reliability

Inter-rater reliability of the OME was assessed by six dyads of research assistants’ ratings of the engagement measures during 48 engagement sessions with nursing home residents. The inter-rater agreement rate (for exact agreement) averaged 77% across the engagement outcome and setting variables. Intra-class correlation averaged 0.70 across the outcome and setting variables.

Analytic approach

Dependent measures were duration, attention, and attitude. When a study participant refused a stimulus, we coded duration as 0 s and scored both the attention and attitude variables as missing for that trial for the purpose of analysis. The measure of duration is thus affected by refusals, while attention and attitude do not include them. Attention and duration capture similar aspects with and without examining refusals. Attitude is only measurable in response to a stimulus that is available and therefore not refused.

For the analyses of setting variables, specific engagement stimuli were removed from statistical analysis when the frequency of any level of the setting variable deviated from the grand mean of all engagement stimuli by more than 5%. For example, we calculated that 39% of the engagement stimuli were presented when there were more than nine persons in the room (usually an activity room); however, when music was the engagement stimulus, 48% of the observations found more than nine persons in the room. Since 48% deviates from 39% by more than 5%, music was not included as one of the stimuli in which we examined the effect of number of persons in the room. In this way, we are confident that the results would be due to the number of persons in the room and not confounded by the influence of music. The 5% cut off was set as a limit to acceptable deviation from the mean so as not to confound two different factors, the stimulus factor and the environmental factor, both of which may affect engagement. While 5% is an arbitrary number, it is a common limit denoting small numbers, and also allowed us to have both a sufficient number of stimuli that did not deviate, and to limit the noise in our analysis.

For each level of each setting variable, an average level of engagement was calculated for each participant across all included engagement stimuli. In order to compare two conditions, such as engagement levels with or without modeling of an appropriate behavior to stimuli, we used paired t-tests. To compare three levels of stimuli, we used repeated measures analyses of variance.

Preliminary examination of the data pertaining to light, noise, and number of persons in the room revealed that many of our study participants did not experience all levels of each variable. For instance, only 23 of the 193 participants were observed during dark, normal and bright lighting conditions. When the available number of participants across all three conditions was limited, such as in the case of light, we used paired t-tests to compare two levels of the dimension (e.g., dark versus normal) so that we could maximize the number of participants in these analyses.

In order to examine engagement to stimuli presentation within days versus across days, we took a random sampling of nine days (with two observations per day) for each participant, and compared the length of engagement for stimuli presented on the same day to stimuli presented on a different day using Pearson correlations. For each of these random 9 days, correlations were performed for two sessions within the same day and two sessions across different days for the whole sample. In this way, we had nine correlations within the same day and nine for different days. Those correlations were transformed into z-scores and then compared using a t-test.

To examine the differential impact of presentation on persons with higher and lower cognitive functioning, we divided our sample into comparatively higher functioning study participants (highest third, 65 people or 34.6% of our sample – MMSE score of 10 or higher, mean=14.6) and comparatively lower functioning study participants (lowest third, 60 people or 31.9% of our sample – MMSE score of less than 3, mean=0.5). We performed repeated measures analyses of variance in which cognitive functioning was a between subjects factor and one of the presentation/setting characteristic variables (e.g., modeling versus no modeling) was a within subject factor. The measures of engagement were the dependent variables. Of all the analyses of variance performed, only the analysis pertaining to the order of presentation was significant. For this reason, we show the results of the ANOVA only for the order of presentation. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software.

Results

Order of presentation

Engagement duration increased significantly and participants had a significantly more positive attitude for trials that included modeling of appropriate behavior relative to those that did not (Table 1). Persons with higher levels of cognitive function had a somewhat less favorable attitude to stimuli after the second presentation as compared to the first (Table 2), whereas those with low cognitive function showed a slight improvement in attitude during the second presentation as compared to the first.

Table 1.

Engagement duration, attention, and attitude for setting characteristics.

| Modeling | Duration, mean (SD) | Attention, mean (SD) | Attitude, mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| With modeling | 153 (118.91) | 2.35 (0.66) | 4.90 (0.43) |

| Without modeling | 140 (114.02) | 2.33 (0.63) | 4.85 (0.39) |

| t-value (one-tailed) | t(192) = 3.31*** | t(189) = 0.63 | t(189) = 2.76** |

| Timing | |||

| 10:00 am–12:00 pm | 139 (118.98) | 2.27 (0.62) | 4.85 (0.40) |

| 2:00 pm–5:00 pm | 156 (126.36) | 2.36 (0.66) | 4.87 (0.39) |

| t-value (two-tailed) | t(192) = 2.66** | t(191) = 3.02** | t(191) = 0.67 |

| Light | |||

| Dark | 147 (194.00) | 2.06 (0.80) | 4.81 (0.70) |

| Normal | 193 (127.78) | 2.35 (0.60) | 4.89 (0.37) |

| Bright | 185 (266.89) | 2.08 (0.90) | 4.72 (0.51) |

| t-value dark versus normal (two-tailed) | t(73) = 2.24* | t(73) = 4.40*** | t(73) = 1.30 |

| t-value normal versus bright (two-tailed) | t(46) = 0.12 | t(46) = 2.04* | t(46) = 2.82** |

| Number of people around | |||

| Fewer than four people | 156 (135.15) | 2.26 (0.60) | 4.86 (0.41) |

| 4–9 | 164 (133.04) | 2.35 (0.67) | 4.89 (0.46) |

| More than nine people | 161 (122.52) | 2.20 (0.57) | 4.82 (0.39) |

| Repeated measures ANOVA | F(2,302) = 0.228 | F(2,300) = 5.963** | F(2,300) = 2.419 |

| Noise levela | |||

| None | 160 (195.33) | 2.11 (0.81) | 4.77 (0.53) |

| Moderate | 203 (139.97) | 2.43 (0.66) | 4.91 (0.40) |

| High | 136 (156.41) | 2.26 (0.90) | 4.79 (0.63) |

| t-value low versus moderate (two-tailed) | t(141) = 2.06* | t(141) = 4.89*** | t(141) = 2.45* |

| t-value moderate versus high (two-tailed) | t(99) = 3.17** | t(98) = 1.08 | t(98) = 1.48 |

Notes: The following rating scales were used: attention to the stimulus during an engagement trial was measured on this four-point scale: not attentive, somewhat attentive, attentive, and very attentive; attitude to the stimulus during an engagement trial was measured on a seven-point scale: very negative, negative, somewhat negative, neutral, somewhat positive, positive, and very positive.

Paired t-tests were used rather than ANOVAs because of the small number of persons experiencing all three levels of light and noise

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001.

Table 2.

Engagement duration, attention, and attitude for order of presentation for study participants with the lowest versus highest level of cognitive functioning.

| MMSE | First presentation mean (SD) | Second presentation mean (SD) | Main effect of presentation | Main effect of MMSE | Interaction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engagement duration | Lowest third | 107.74 (99.73) | 111.6 (106.77) | F(1,123) = 0.274 | F(1,123) = 8.303** | F(1,123) = 1.625 |

| Highest third | 174.09 (132.04) | 164.85 (133.05) | ||||

| Attention | Lowest third | 1.884 (0.562) | 1.953 (0.609) | F(1,120) = 0.464 | F(1,120) = 54.428*** | F(1,120) = 1.510 |

| Highest third | 2.669 (0.609) | 2.649 (0.574) | ||||

| Attitude | Lowest third | 4.649 (0.387) | 4.683 (0.404) | F(1,120) = 1.052 | F(1,120) = 29.210*** | F(1,120) = 5.348* |

| Highest third | 5.066 (0.398) | 4.977 (0.378) |

Note:

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001.

Timing

Engagement duration and attention were significantly greater in the afternoon (2–5) than in the morning hours (10–12; Table 1). In order to examine engagement to stimuli presentation across days, we took a random sampling of nine days and compared the length of engagement for stimuli presented that same day to stimuli presented on a different day. Although the mean (across the nine days, calculated through transformation to z scores) correlations for stimuli presented on the same day (r=0.213) were slightly higher than those comparing two different days (r=0.174), the difference between these correlations (transformed to z scores) did not reach significance.

Setting characteristics

Attention and engagement duration were higher when light was normal in comparison to a dark room; moreover, attention and attitude were significantly less positive when the lighting in the room was bright than when the lighting was normal (Table 1). As to noise, all indicators of engagement significantly favored a moderate level of noise over none or low-noise levels, and engagement duration was significantly longer for moderate noise when compared to high and very high levels of noise (Table 1). Attention to the engagement stimulus was significantly higher when there were four to nine people in the room versus fewer than four or greater than nine (Table 1). The impact of environmental factors on refusal was examined and there were no significant findings.

In order to clarify the aforementioned relationships, we examined the interrelationships among the setting characteristic variables. As expected, there were low but significant correlations among the variables. A dark setting was associated with few people in the room (r=0.13, p < 0.01) and with lower levels of noise (r=0.14; p < 0.01). The presence of more people in the room was associated with more noise (r=0.33, p < 0.01).

Discussion

In general, the findings support the importance of setting and presentation variables when engaging persons with dementia. These do not support, however, the idea that environmental and presentation attributes will have a stronger effect when dementia is more advanced. Modeling presentation, moderate level of noise, and a limited (four to nine) number of persons in the room optimized engagement for this population regardless of cognitive functioning. The only aspect of engagement affected by cognitive functioning was repetition, where persons with higher levels of cognitive functioning had a somewhat lower attitude to the second presentation in comparison to the first. Future research should explore whether there is interaction with type of dementia rather than the level of dementia.

As hypothesized, modeling of the appropriate response to the stimuli positively increased engagement for the nursing home residents in our study, suggesting that nursing homes should look for ways to implement modeling of activities into their care plans. Previously, Engelman, Altus, and Mathews (1999) trained nursing assistants to make personal contact with five residents with dementia at least every 15 min, to provide praise for appropriate engagement, and to offer a choice of at least two activities if the resident was not engaged, and found that the number and variety of engagement activities increased markedly from baseline to follow-up. Both the Engelman et al. (1999) study as well as the present study suggest that both staff and volunteers who are involved with residents should receive training in how to introduce and model different activities.

When examining an interaction effect with cognitive function, only presentation order had a statistically significant effect. Persons with higher cognitive ability showed a decline in attitude toward the stimulus with the second presentation of a stimulus in comparison to the first presentation, whereas this effect went in the other direction for the more cognitively impaired persons. Significant results were not found, however, with regard to engagement duration or attention. Despite an effect of presentation order, the attitudes of those with comparatively higher cognitive ability at the second presentation were still more positive than the attitudes of the very impaired. These findings taken together suggest that multiple presentations of the same stimulus are appropriate for nursing home residents with varying levels of cognitive decline. In our clinical research (Cohen-Mansfield & Werner, 1997), we have utilized the reduced habituation to stimuli in persons with cognitive impairment in response to our showing family videotapes three times in a session (each for about 10 min) on a daily basis for two weeks. In our experience, only participants with mild dementia became bored with the tapes. This lack of habituation therefore serves caregivers facilitation of engagement so that they do not have to find new stimuli each day. Future research needs to examine the impact of additional repetition (i.e., when a stimulus is repeated daily, when and for whom is it likely to be rejected).

Whereas the day of presentation did not significantly influence engagement, a surprising finding is that we were more able to engage residents after 2:00pm rather than in the morning hours. We randomized all stimuli across all days (as well as randomizing research assistants), so the finding does not appear to be the result of our protocol. It is possible that the general level of arousal is lower in the morning, which in turn affects engagement with stimuli. Clearly, time of day is a topic that deserves further research. Along these lines, the role of seasonal change on engagement may also be an interesting area of study to pursue.

As to the influence of setting characteristics, we found that normal lighting, moderate levels of sound, and being near a small number of people (from four to nine) were all positively linked with engagement. Our finding with respect to sound is consistent with previous researchers who found that persons with dementia recall answers better when there is some room noise versus none (Foster & Valentine, 2001).

The study has several limitations. We were limited in our ability to examine the role of the setting characteristics since it was not possible to manipulate these conditions to achieve comparable numbers of observations for all levels of a stimulus (e.g., normal lighting was observed more often than either dark or bright light). This in turn forced us to utilize separate t-tests to compare various levels of the same dimension. Another limitation is that we based the ratings of light and noise on the perceptions of the research assistants rather than on objective measures, which were not available for this study. Consensus among the researchers as to what constituted the various ratings guided the rating process. Future researchers may consider utilizing equipment for better capturing levels of sound and lighting, such as lux meters. A further limitation is the inter-rater reliability, which, while acceptable, is lower than we desired, adding variability and thereby decreasing the power of the results. Finally, the varying numbers of participants in different conditions required that we conduct multiple exploratory tests rather than using a multivariate analysis, thus increasing the probability of error. However, the consistencies in the descriptive statistics provided suggest that the findings are robust. Future research needs to examine environmental attributes with more objective assessments and manipulate environmental conditions in an experimental design, such as light and noise, rather than rely on the variability in the natural environment. Finally, this article focuses on environmental effects but does not describe person or stimulus effects. It should be noted that, although the focus of this study was on environmental and stimulus attributes, personal attributes of the person with dementia can play a strong role in engagement. This role is discussed in a previous article (Cohen-Mansfield et al., 2009b). Personal preferences, which represent stimulus-person interaction, are also important (Cohen-Mansfield, Marx, Thein, & Dakheel-Ali, in press).

There is a growing body of research which suggests that persons with varying degrees of cognitive impairment can accurately and reliably answer questions and report on their preferences and experiences (Feinberg & Whitlatch, 2001, 2002; Whitlatch, Feinberg, & Tucke, 2005). Several studies indicate that cognitively impaired individuals retain a sense of self, even in late stages of their illness (Kitwood, 1997; Woods, 1999), and are capable of communicating information about feelings and preferences (Feinberg & Whitlatch, 2001; Squillace, Mahoney, Loughline, Simon-Rusinowitz, & Desmond, 2002). In a qualitative study, Clare, Rowlands, Bruce, Surr, and Downs, (2008a,b) observed a retained sense of self, identity, and awareness in persons with moderate-to-severe dementia in long-term care facilities. Given these findings, caregivers should make an effort to elicit and incorporate the preferences of persons with dementia into their care and activity plans.

Future research may also examine person–environment interaction, i.e., whether a person’s preferences for certain environmental conditions affect his/her engagement under those versus other conditions. We are currently preparing a GEE analysis in which we are trying to describe the effect of multiple model components, i.e., personal, stimulus, and environmental attributes simultaneously. While that paper does provide a global picture, it misses much of the details and specifics for each part of the model. Therefore, our approach was to first examine and write up each component of the model in depth and then have a less thorough examination of the model as a whole.

The findings of this study offer an important contribution to the limited extant literature on the relationship between environmental attributes and engagement of persons with dementia, particularly because it avoids many of the flaws in the designs of existing studies on this topic (Gitlin et al., 2003). The findings have direct implications for the way in which caregivers should structure the setting and the presentation of stimuli to optimize engagement by persons with dementia, including using modeling and setting environments with moderate levels of light, noise, and number of persons. More research of this nature is needed, as engagement of nursing home residents in appropriate activities has been linked to reductions in agitation, apathy, and caregiver burden.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant AG R01 AG021497. We thank the nursing home residents, their relatives, and the nursing homes’ staff members and administration for all of their help, without which this study would not have been possible.

References

- Baker R, Bell S, Baker E, Gibson S, Holloway J, Pearce R, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the effects of multi-sensory stimulation (MSS) for people with dementia. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2001;40(Part 1):81–96. doi: 10.1348/014466501163508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belleville S, Rouleau N, Van der Linden M, Collette F. Effect of manipulation and irrelevant noise on working memory capacity of patients with Alzheimer’s dementia. Neuropsychology. 2003;17(1):69–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branch LG, Horowitz A, Carr C. The implications for everyday life of incident of self-reported visual decline among people over age 65 living in the community. The Gerontologist. 1989;29(3):359–365. doi: 10.1093/geront/29.3.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buettner L. Simple pleasures: A multilevel sensorimotor intervention for nursing home residents with dementia. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias. 1999;14(1):41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Buettner L, Fitzsimmons S. Activity calendars for older adults with dementia: What you see is not what you get. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias. 2003;18(4):215–226. doi: 10.1177/153331750301800405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgio LD, Scilley K, Hardin JM, Hsu C. Temporal patterns of disruptive vocalization in elderly nursing home residents. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2001;16(4):378–386. doi: 10.1002/gps.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgio LD, Scilley K, Hardin JM, Janosky J, Bonino P, Slater SC, et al. Studying disruptive vocalization and contextual factors in the nursing home using computer-assisted real-time observation. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 1994;49(5):230–239. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.5.p230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clare L, Rowlands J, Bruce E, Surr C, Downs M. ‘I don’t do like I used to’: A grounded theory approach to conceptualizing awareness in people with moderate to severe dementia. Social Science and Medicine. 2008a;66(11):2366–2377. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clare L, Rowlands J, Bruce E, Surr C, Downs M. The experience of living with dementia in residential care: An interpretive phenomenological analysis. The Gerontologist. 2008b;48(6):711–720. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.6.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark ME, Lipe AW, Bilbrey M. Use of music to decrease aggressive behaviors in people with dementia. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 1998;24(7):10–17. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-19980701-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Mansfield J. Temporal patterns of agitation in dementia. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2007;15(5):395–405. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000247162.59666.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Mansfield J, Dakheel-Ali M, Marx MS. Engagement in persons with dementia: The concept and its measurement. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2009a;17(4):299–307. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31818f3a52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Mansfield J, Kerin P, Pawlson LG, Lipson S, Holdridge K. Informed consent for research in the nursing home: Processes and issues. The Gerontologist. 1988;28(3):355–359. doi: 10.1093/geront/28.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Mansfield J, Marx MS, Dakheel-Ali M, Regier NG, Thein K. Can persons with dementia be engaged with stimuli? American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. doi: 10.1097/jgp.0b013e3181c531fd. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Mansfield J, Marx MS, Regier NG, Dakheel-Ali M. The impact of personal characteristics on engagement in nursing home residents with dementia. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2009b;24(7):755–763. doi: 10.1002/gps.2192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Mansfield J, Marx MS, Thein K, Dakheel-Ali M. The impact of past and present preferences on stimulus engagement in nursing home residents with dementia. Aging & Mental Health. doi: 10.1080/13607860902845574. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Mansfield J, Marx MS, Thein K, Dakheel-Ali M. The impact of stimuli on affect in persons with dementia. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05694oli. under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Mansfield J, Marx MS, Werner P. Observational data on time use and behavior problems in the nursing home. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 1992;11(1):111–121. doi: 10.1177/073346489201100109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Mansfield J, Taylor J. Hearing aid use in nursing homes. Part 1: Prevalence rates of hearing impairment and hearing aid use. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2004;5(5):283–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Mansfield J, Werner P. Management of verbally disruptive behaviors in nursing home residents. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 1997;52A(6):M369–M377. doi: 10.1093/gerona/52a.6.m369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Mansfield J, Werner P. The effects of an enhanced environment on nursing home residents who pace. The Gerontologist. 1998;38(2):199–208. doi: 10.1093/geront/38.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Mansfield J, Werner P, Marx MS. An observational study of agitation in agitated nursing home residents. International Psychogeriatrics. 1989;1:153–165. doi: 10.1017/s1041610289000165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conroy MC, Fincham F, Agard-Evans C. Can they do anything? Ten single subject studies of the engagement level of hospitalized demented patients. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1988;51(4):129–132. [Google Scholar]

- Engelman KK, Altus DE, Mathews RM. Increasing engagement in daily activities by older adults with dementia. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1999;32(1):107–110. [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg LF, Whitlatch CJ. Are persons with cognitive impairment able to make consistent choices? The Gerontologist. 2001;41(3):1–9. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.3.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg LF, Whitlatch CJ. Decision-making for persons with cognitive impairment and their family caregivers. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias. 2002;17(4):237–244. doi: 10.1177/153331750201700406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster NA, Valentine ER. The effect of auditory stimulation on autobiographical recall in dementia. Experimental Aging Research. 2001;27(3):215–218. doi: 10.1080/036107301300208664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN, Liebman J, Winter L. Are environmental interventions effective in the management of Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders? A synthesis of the evidence. Alzheimers Care Quarterly. 2003;4(2):85–107. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz A. Vision impairment and functional disability among nursing home residents. The Gerontologist. 1994;34(3):316–323. doi: 10.1093/geront/34.3.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kincaid C, Peacock JR. Effect of a wall mural on decreasing four types of door-testing behaviors. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2003;22(1):76–88. [Google Scholar]

- Kitwood T. The experience of dementia. Aging and Mental Health. 1997;1(1):13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kolanowski A, Buettner L, Costa PT, Litaker M. Capturing interests: Therapeutic recreation activities for persons with dementia. Therapeutic Recreation Journal. 2001;35(3):220–235. [Google Scholar]

- Kolanowski A, Buettner L, Litaker M, Yu F. Factors that relate to activity engagement in nursing home residents. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias. 2006;21(1):15–22. doi: 10.1177/153331750602100109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolanowski AM, Richards KC. Introverts and extroverts: Leisure activity behavior in persons with dementia. Activities, Adaptation, and Aging. 2002;26(4):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kovach CR, Henschel H. Planning activities for patients with dementia: A descriptive study of therapeutic activities on special care units. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 1996;9:33–38. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-19960901-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP. The elderly in context perspectives from environmental psychology and gerontology. Environment and Behavior. 1985;17:501–519. [Google Scholar]

- Lovell BJ, Ancoli-Israel S, Gevirtz R. The effect of bright light treatment on agitated behavior in institutionalized elderly. Psychiatry Research. 1995;57(1):7–12. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(95)02550-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucero M, Pearson R, Hutchinson S, Leger-Krall S, Rinalducci E. Products for Alzheimer’s self-stimulatory wanderers. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias. 2001;16(1):43–50. doi: 10.1177/153331750101600104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyketsos CG, Lindell VL, Baker A, Steele C. A randomized, controlled trial of bright light therapy for agitated behaviors in dementia patients residing in long-term care. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 1999;14(7):520–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx MS, Werner P, Cohen-Mansfield J, Feldman R. The relationship between low vision and performance of activities of daily living in nursing home residents. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1992;40(10):1018–1020. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb04479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx MS, Werner P, Feldman RC, Cohen-Mansfield J. Progression of eye disorders in a nursing home. Journal of Visual Impairment and Blindness. 1997;91(6):571–578. [Google Scholar]

- McCann JJ, Gilley DW, Bienias JL, Beckett LA, Evans DA. Temporal patterns of negative and positive behavior among nursing home residents with Alzheimer’s disease. Psychology and Aging. 2004;19(2):336–345. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.2.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez M, Cherrier M, Meadows R. Depth perception in Alzheimer’s disease. Perceptual Motor Skills. 1996;83:987–995. doi: 10.2466/pms.1996.83.3.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer DL, Dorbacker B, O’Rourke J, Dowling J, Jacques J, Nicholas M. Effects of a ‘quiet week’ intervention on behavior in an Alzheimer boarding home. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias. 1992;7(4):2–6. [Google Scholar]

- Mienaltowski A, Blanchard-Fields F. The differential effects of mood on age differences in the correspondence bias. Psychology and Aging. 2005;20(4):589–600. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.4.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooney P, Nicell PL. The importance of exterior environment for Alzheimer residents: Effective care and risk management. Healthcare Management Forum. 1992;5(2):23–29. doi: 10.1016/S0840-4704(10)61202-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan DG, Stewart MJ. Multiple occupancy versus private rooms on dementia care units. Environment and Behavior. 1998;30:487–504. [Google Scholar]

- Morris J, Hawes C, Murphy K, Nonemaker S. MDS Resident Assessment. Natick, MA: Eliot Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Namazi KH, Johnson BD. Environmental effects on incontinence problems in Alzheimer’s disease patients. The American Journal of Alzheimer’s Care and Related Disorders and Research. 1991;6(6):16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Orsulic-Jeras S, Judge KS, Camp CJ. Montessori-based activities for long-term care residents with advanced dementia: Effects on engagement and affect. The Gerontologist. 2000;40(1):107–111. doi: 10.1093/geront/40.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick HE, Fries BE, Verbrugge LM. Windows to their world: The effect of sensory impairments on social engagement and activity time in nursing home residents. Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 1997;52B(3):S135–S144. doi: 10.1093/geronb/52b.3.s135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal TL, Bandura A. Psychological modeling: Theory and practice. In: Garfield SL, Bergin AE, editors. Handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change: An empirical analysis. 2. New York: Wiley Press; 1978. pp. 621–658. [Google Scholar]

- Schnelle J, MacRae P, Ouslander J, Simmons SF, Nitta M. Functional incidental training, mobility performance, and incontinence care with nursing home residents. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1995;43(12):1356–1362. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb06614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiner AS, Yamamoto E, Shiotani H. Positive affect among nursing home residents with Alzheimer’s dementia: The effect of recreational activity. Aging and Mental Health. 2005;9(2):129–134. doi: 10.1080/13607860412331336841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squillace MR, Mahoney KJ, Loughlin DM, Simon-Rusinowitz L, Desmond SM. Personal assistance service choice and decision-making among persons with disabilities and surrogate representatives. Journal of Mental Health and Aging. 2002;8:225–240. [Google Scholar]

- Van Haitsma K, Lawton MP, Kleban MH, Kleban MH, Klapper J, Corn J. Methodological aspects of the study of streams of behavior in elders with dementing illness. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders. 1997;11:228–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voelkl JE, Fries BE, Galecki AT. Predictors of nursing home residents’ participation in activity programs. The Gerontologist. 1995;35(1):44–51. doi: 10.1093/geront/35.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlatch CJ, Feinberg LF, Tucke S. Accuracy and consistency of responses from persons with cognitive impairment. Dementia. 2005;4(2):171–183. [Google Scholar]

- Woods B. The person in dementia care. Generations. 1999;23(3):35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Zeisel J, Silverstein NM, Hyde J, Levkoff S, Lawton MP, Holmes W. Environmental correlates to behavioral health outcomes in Alzheimer’s special care units. The Gerontologist. 2003;43(5):697–771. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.5.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]