Abstract

Late congenital syphilis is a rare entity and its early diagnosis and treatment is essential to prevent significant morbidity. We are reporting a case of late congenital syphilis presenting with Hutchinson's triad at an age of 14 years.

Keywords: Congenital syphilis, Hutchinson's triad

INTRODUCTION

Congenital syphilis is the oldest recognized congenital infection, and continues to account for extensive global perinatal morbidity and mortality. Globally just over 2 million pregnant women test positive for syphilis each year, comprising 1.5% of all pregnancies worldwide.[1,2] This results in an estimated 692,100 to 1.53 million adverse pregnancy outcomes each year caused by syphilis.[3–6] Approximately 650,000 of these pregnancy complications result in perinatal deaths (ie, deaths occurring from 22 weeks gestation through the first 7 days of life).

Late congenital syphilis (recognized 2 or more years after birth)[7] is a very rare clinical entity. We are reporting here a case of late congenital syphilis who presented at the age of 14 years with Hutchinson's triad to emphasize that congenital syphilis still is not recognized early and antenatal screening is mandatory to prevent this serious, yet largely preventable disease.

CASE REPORT

A 14-year-old female was referred to us from the ENT department of our hospital for palatal perforation associated with regurgitation. She also had a complaint of diminished vision since 4 years and impaired hearing. There was no history or signs suggestive of sexual abuse. There was no history of STD in parents.

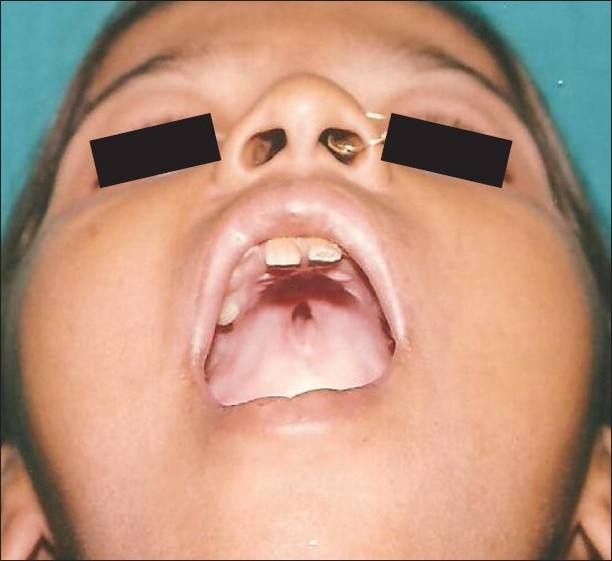

On examination, there was a perforation of about 1 cm diameter involving the hard palate. Her upper incisors were peg-shaped and widely spaced, suggestive of Hutchinson's teeth [Figure 1]. There was no lymphadenopathy. There was no apparent bony abnormality. No evidence of neurological or cardiovascular involvement. Her intelligence was apparently normal.

Figure 1.

Palatal perforation and Hutchinson's teeth

On investigating, her venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) testing was reactive at 1:64 dilutions. She was nonreactive for HIV. Slit-lamp examination revealed dot-like corneal opacities suggestive of interstitial keratitis and audiogram showed sensory neural deafness. The findings of interstitial keratitis, sensory-neural deafness and Hutchinson's teeth completed the Hutchinson's triad in this patient. X-ray of legs was normal. CBC, electrocardiogram, X-ray chest, and ultrasonography abdomen were normal. Her parents were VDRL reactive. The girl was treated with three weekly doses of Benzathine penicillin 2.4 million units intramuscularly. Her parents were also treated with same regimen. On follow-up, some healing of the perforation was observed.

DISCUSSION

Congenital syphilis, if not treated promptly and adequately, may result in significant physical sequelae in children. This case remained undiagnosed even after the presence of classical Hutchinson's triad age of 14 years. The diagnostic delay in this case led to the development of several irreversible stigmata, which could have been prevented by timely intervention.

Late congenital syphilis results primarily from chronic inflammation due to T. pallidum. This leads to many classical stigmata of syphilis-like bony prominence of forehead (Olympian brow), thickening of sternoclavicular portion of the clavicle, anterior bowing of the mild portion of tibia (saber shins), and scaphoid scapula result due to persistent or recurrent periostitis. Peg-shaped upper central permanent incisors and notched enamel (Hutchison teeth) are common. Saddle nose due to syphilitic rhinitis and a perforated nasal septum can occur. Other features of late congenital syphilis are Juvenile paresis, juvenile tabes dorsalis, aortitis, interstitial keratitis, and Clutton's joints. As many as one-fourth to one-third of patients older than 2 years have asymptomatic neurosyphilis.[8]

Sir Jonathan Hutchinson (1828–1913) from England described a triad in late congenital syphilis consisting of notched incisors, interstitial keratitis, and eighth cranial nerve deafness. All the three findings were present in this case.

The patient also had palatal perforation for which the other differentials are TB, tertiary syphilis, typhoid, diphtheria, mucormycosis, actinomycosis, lymphoma, carcinoma, melanoma, Wegener's granulomatosis, SLE, midline lethal granulomas, sarcoidosis, and cocaine abuse. Treatment of late syphilis will not reverse the tissue damage but it may result in some improvement.

Eighth cranial nerve deafness seen in congenital syphilis, is of sudden onset and usually occurs around 8–10 years of age. As per a systematic review of pediatric sensorineural hearing loss in congenital syphilis by Chau et al. it was concluded that newborns with positive syphilis serology should have hearing screening performed at birth and receive treatment with an appropriate course of penicillin therapy. Longitudinal hearing screening is recommended for all pediatric patients with congenital syphilis, as further studies documenting longitudinal audiometric data for patients previously treated either fully or partly for congenital syphilis are required.[9]

Interstitial keratitis due to congenital syphilis is commonly a late finding. Most cases of interstitial keratitis develop in patients aged 5–20 years. Congenital syphilitic interstitial keratitis is typically bilateral in 80% of cases. Uchiyama et al reported a rare case of Phthisis bulbi resulting from late congenital syphilis.[10]

CONCLUSION

Although syphilis is one of the best-known STDs, for which effective treatment has been available since the introduction of penicillin in the mid-20th century, it still remains an important global health problem. Such reports of late congenital syphilis are a tragic reflection of pitfalls in the screening programs. More emphasis must be placed on primary prevention and appropriate screening programs so that maternal and neonatal syphilis can be identified and treated early, avoiding significant future morbidity.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schmid GP, Stoner BP, Hawkes S, Broutet N. The need and plan for global elimination of congenital syphilis. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34:S5–10. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000261456.09797.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmid G, Rowley J, Samuelson J, Tun Y, Guraiib M, Mathers C, et al. London, UK: 2009. Jun-Jul. Global incidence and prevalence of four curable sexually transmitted infections (STIs): New estimates from WHO, in Proceedings of the nd Global HIV/AIDS Surveillance Meeting (ISSTDR ’09) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watson-Jones D, Changalucha J. Syphilis in pregnancy in Tanzania. I. Impact of maternal syphilis on outcome of pregnancy. J Infect Dis. 2002;186:940–7. doi: 10.1086/342952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watson-Jones D, Weiss HA, Changalucha JM, Todd J, Gumodoka B, Bulmer J, et al. Adverse birth outcomes in United Republic of Tanzania-impact and prevention of maternal risk factors. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85:9–18. doi: 10.2471/BLT.06.033258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schulz KF, Cates W, Jr, O’Mara PR. Pregnancy loss, infant death, and suffering: Legacy of syphilis and gonorrhoea in Africa. Genitourin Med. 1987;63:320–5. doi: 10.1136/sti.63.5.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization Global Burden of Disease Report, WHO; 2002. World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larsen SA, Steiner BM, Rudolph AH. Laboratory diagnosis and interpretation of tests for syphilis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:1–21. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wile U, Mundt LK. Congenital syphilis: A statistical study with special regard to sex incidence. Am J Syphilis Gonorrhea Vener Dis. 1942;26:70–83. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chau J, Atashband S, Chang E, Westerberg BD, Kozak FK. A systematic review of pediatric sensorineural hearing loss in congenital syphilis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73:787–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2009.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uchiyama K, Tsuchihara K, Horimoto T, Karasawa T, Sugiyama K. Phthisis bulbi caused by late congenital syphilis untreated until adulthood. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139:545–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.08.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]