Abstract

Multiple pathways converge to result in the overexpression of Th17 cells in the absence of either vitamin D or the vitamin D receptor (VDR). CD4+ T cells from VDR knockout (KO) mice have a more activated phenotype than their wild-type (WT) counterparts and readily develop into Th17 cells under a variety of in vitro conditions. Vitamin D-deficient CD4+ T cells also overproduced IL-17 in vitro and 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3 inhibited the development of Th17 cells in CD4+ T-cell cultures. Conversely, the induction of inducible (i) Tregs was lower in VDR KO CD4+ T cells than WT and the VDR KO iTregs were refractory to IL-6 inhibition. Host-specific effects of the VDR were evident on in vivo development of naive T cells. Development of naive WT CD4+ T cells in the VDR KO host resulted in the overexpression of IL-17 and more severe experimental inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). The increased expression of Th17 cells in the VDR KO mice was associated with a reduction in tolerogenic CD103+ dendritic cells. The data collectively demonstrate that Th17 and iTreg cells are direct and indirect targets of vitamin D. The increased propensity for development of Th17 cells in the VDR KO host results in more severe IBD.

Keywords: inducible T reg, inflammatory bowel disease, Th17 cells, vitamin D receptor

Introduction

In the healthy intestine, there is a balance between protective effector T-cell responses to opportunistic infection and tolerogenic T-cell responses to harmless commensal flora. When the balance is disrupted, chronic intestinal inflammation can occur and results in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (1). Th1 and/or Th17 T cells are pro-inflammatory and are associated with increased severity of inflammation in experimental IBD (2). Several regulatory T cells have been shown to prevent inflammation, including naturally occurring Foxp3+CD4 regulatory T cells (Treg) and CD8αα T cells (3, 4). Tolerogenic CD103+ dendritic cells (DCs) present in the mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN) inhibit Th1/Th17 T-cell differentiation and drive the development of Tregs (5). Maintaining a balance in these T-cell responses is critical for gastrointestinal homeostasis.

Control of inflammation in the gut relies on the balance between the Th17 cells and inducible regulatory T (iTreg) cells. Interestingly, these two cells develop in response to transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGF-β1) and therefore, Th17 and iTreg are considered to function in part by direct inhibition of each other (6). TGF-β1 addition to CD4 cultures in vitro induces expression of the transcription factor Foxp3 and production of IL-10 (7). Th17 cells develop in the presence of TGF-β1 and IL-6 by suppressing Foxp3 induction and up-regulating two other Th17 transcription factors retionid-related orphan receptor (ROR)γt and RORα (8–10). In vivo, an increase in Th17 cells in the gut is associated with a reciprocal decrease in Treg cells and vice versa (6, 11). It has therefore been suggested that Treg and Th17 cells may represent alternative cell fates of the same precursors.

Vitamin D and the vitamin D receptor (VDR) are critical for the maintenance of gastrointestinal homeostasis. Vitamin D is an important regulator of the immune system and deficiency has been linked to increased susceptibility to IBD (12, 13). Vitamin D-deficient or VDR knockout (KO) mice are susceptible to several different models of IBD (12, 14). Treating mice with the active form of vitamin D, 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25D3), suppresses IBD (15). The increased susceptibility of VDR KO mice to IBD is a result in part to reduced numbers of invariant NKT cells as well as CD8αα T cells in the gut (12, 14, 16). Naturally occurring VDR KO Tregs are present in normal numbers and suppress as well as wild-type (WT) Tregs both in vitro and in vivo (14). 1,25D3 treatments in vitro and in vivo have been shown to increase the numbers of Foxp3+ Treg cells (17). Recently, several groups have shown that 1,25D3 addition in vitro inhibits IL-17 production (18, 19). In addition, the beneficial effects of 1,25D3 in experimental uveitus have been ascribed to reduced production of IL-17 (20).

VDR KO CD4 T cells are more pathogenic than their WT counterparts (12). In addition, VDR KO CD4 T cells produced more IFN-γ and proliferated more in a mixed lymphocyte reaction (12). Here, we determined the cause of the increased pathogenicity of VDR KO CD4 T cells (12). Specifically, the role of the VDR and vitamin D in the induction of Th17 cells both in vitro and in vivo was determined. There was an increased in vitro Th17 differentiation of VDR KO or vitamin D-deficient CD4 T cells and the addition of 1,25D3 to CD4 T-cell cultures inhibited Th17-cell development. The increased differentiation of VDR KO T cells into Th17 cells also occurred under Treg-inducing conditions. Using only naive T cells in the cultures eliminated the effects for the VDR on Th17 development and suggested that overproduction of IL-17 by CD4+ T cells from VDR KO mice may be T cell extrinsic. Supporting a T-cell extrinsic effect of the VDR on Th17 cells, development of WT Th17 cells was increased in the VDR KO host and resulted in a fulminating form of IBD. T cells as well as DCs and host antigen-presenting cells require expression of the VDR to control the number of Th17 cells that develop. In the absence of the VDR, T cells preferentially develop into Th17 cells and experimental IBD is more severe.

Methods

Mice

Age- and sex-matched VDR KO, Cyp27B1 KO, Rag KO, DKO and WT C57BL/6 mice were produced at the Pennsylvania State University (University Park, PA, USA). Cyp27B1 is the enzyme that converts 25(OH)D3 to 1,25D3 and therefore, Cyp27B1 KO mice are 1,25D3 deficient. For vitamin D-deficient mice, breeders were fed synthetic diets that do not contain vitamin D as described previously (15). Cyp27B1 KO mice were a kind gift from Dr Hector DeLuca (University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, USA). Experimental procedures received approval from the Office of Research Protection Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Pennsylvania State University.

T-cell isolation and culture

CD4+ T cells were purified by mouse CD4 cell recovery column kit (Cedarlane Laboratories Ltd, Burlington, NC, USA). The purity of CD4+ T cells was >90%. For some experiments, CD4+CD25−CD62L+CD44low cells or CD4+ CD45RBhigh cells were sorted using a Cytopeia Influx cell sorter (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA, USA). CD4+ T cells and naive CD4+ CD25−CD62L+CD44low T cells were cultured in RPMI 1640. Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS (Thermo-Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA), 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U ml−1 penicillin and 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin and 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Purified CD4+ T cells (2 × 106) or whole splenocytes (2 × 106) were stimulated with 5 μg ml−1 of anti-CD3 (2C11) and 5 μg ml−1 anti-CD28 (BD Pharmingen). In addition to CD3 and CD28 stimulation, some of the cultures contained different combinations of cytokines and neutralizing antibodies. Th0 cultures contained 10 μg ml−1 of anti-IL-4 and 1 μg ml−1 of anti-IFN- γ but not added cytokines; iTreg cultures contained 5 ng ml−1 of TGF-β1, 10 μg ml−1 of anti-IL-4 and 1 μg ml−1 of anti-IFN- γ; Th17 cultures contained 10 ng ml−1 of IL-6, 5 ng ml−1 of TGF-β1, 10 μg ml−1 of anti-IL-4 and 1 μg ml−1 of anti-IFN-γ; additional Th17 cultures contained 100 ng ml−1 of IL-21, 5 ng ml−1 of TGF-β1, 10 μg ml−1 of anti-IL-4, 1 μg ml−1 of anti-IFN-γ and 10 μg ml−1 anti-IL-12; additional Th17 cultures contained 100 ng ml−1 of IL-1α, 20 ng ml−1 IL-6, 10 μg ml−1 of anti-IL-4, 1 μg ml−1 of anti-IFN-γ and 10 μg ml−1 anti-IL-12. Cytokines were purchased from (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA) except that TGF-B1 was from (R&D, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Antibodies were from BD Pharmingen. For some cultures, 100 nM of 1,25D3 dissolved in ethanol or the equivalent amount of ethanol was added to in vitro cultures.

Bone marrow transplantation and CD45RBhigh transfer

Donor bone marrow (BM) cells were isolated and transferred into sub-lethally irradiated CD45-mismatched recipients. Mice were allowed 6 weeks to recover and reconstitution of BM was evaluated in the blood by flow cytometry and staining for donor CD45 expression. Splenocytes from transplant recipients were isolated and stained for FITC anti-CD45.1 or CD45.2, PE anti-CD45RB and PE-Cy5 anti-CD4 (BD Bioscience). Cells were sorted for donor CD45 and CD4 and then selected as CD45RBhigh. CD4+ CD45RBhigh T cells (4.0 × 105) were injected into each Rag KO or Rag/VDR DKO mouse. The recipients were monitored for weight loss weekly. Mice were sacrificed before losing 20% of their starting body weight (BW).

IBD severity

Colitis development was monitored by weight curves, observation of stool consistency, histopathology scores, anal bleeding, rectal prolapse and death. The small intestine (SI) and colon were removed and the tissue was fixed in formalin and sent to the Pennsylvania State University Animal Diagnostic Laboratories for sectioning and staining with hematoxylin and eosin. Sections were scored blindly and exactly as described previously (12) by two observers on a scale of 0–4 for inflammation and 0–4 for epithelial thickening and the scores were added to give a range of 0–8. At least three serial sections of the colon were observed and scored per animal.

Isolation of intraepithelial lymphocytes

The SI was removed and flushed with HBSS (Sigma–Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) containing 5% FCS and the Peyer’s patches were removed. The intestine was cut into 0.5-cm pieces. The pieces were incubated twice in media containing 0.15 μg ml−1 dithiothreitol (Sigma–Aldrich) and stirred at 37°C for 20 min. Supernatants were collected and the intraepithelial lymphocytes (IEL) were collected at the interface of 40/80% Percoll gradients (Sigma–Aldrich).

Intracellular staining and flow cytometry

Splenocytes and IEL were stained with conjugated antibodies: ECD anti-CD4 (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL, USA), PE anti-CD8β or PE anti-CD62L, FITC anti-CD25, PE-Cy5 anti-TCRβ and PE-Cy7 anti-CD8α and appropriate isotype controls (BD Bioscience). To characterize DCs, single-cell suspensions were stained with FITC anti-CD11b, PE anti-CD103, PE-Cy5 anti-CD8 and PE-Cy7 anti-CD11c or isotype control (BD Bioscience). To eliminate lymphocytes, the high forward scatter/side scatter dot plots were first gated on to determine DCs frequency. For intracellular staining, cells were stimulated for 12 h with phorbol myristate acetate (0.1 μg), ionomycin (0.5 μg) and brefeldin A (10 μg) (all reagents from Sigma–Aldrich) for the final 6 h. Surface markers were stained and the cells were fixed, permeabilized and stained with FITC-labeled anti-IFNγ clone B27, PE-labeled anti-IL-17A (TC11) and Alex488 labeled-Foxp3 (BD Bioscience). Flow cytometry analyses were performed on a FC500 bench top cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). Data were evaluated with WinMDI 2.9 software (Scripps Institute, La Jolla, CA, USA). Supernatants from 72-h cultures were analyzed for the production of IL-10 and IL-17 by ELISAs (BD Bioscience).

Reverse transcription–Quantitative PCR

Total RNA was prepared from differentiated T cells 72 h after stimulation RNeasy Mini kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA, USA). cDNA was synthesized with the Taqman Reverse kit (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Quantitative reverse transcription–PCR was performed on a 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR instrument (Applied Biosystems) with TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) for IL-17A, IL-17F, IL-21 and IL-22 (Applied Biosystems). The data in differentiated CD4+ T cells were expressed relative to naive CD4+ T cells. The data were expressed as 2−ΔΔCT with the ABI 7500 SDS 1.3.1 software.

Statistics

Bar graphs are represented as mean ± SEM. A two-way mixed methods analysis of variance was performed or in some cases, a two-tailed unpaired t-test using Prism 5.0 statistical software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). P-values of ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Increased production of IL-17 in the absence of the VDR

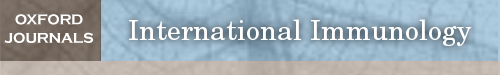

In order to determine the effects of VDR expression on Th17-cell development, cultures of CD4+ T cells were done in the presence of iTreg-inducing TGF-β1 or Th17-inducing TGF-β1 and IL-6. TGF-β1 induces iTreg cells when added alone to CD4+ T cells (21). Addition of IL-6 plus TGF-β1 to CD4+ T cells inhibits iTregs and up-regulates Th17 cells (22). Th0 cultures showed that there was a very low frequency of IL-17-secreting T cells in either WT or VDR KO mice (Supplementary Figure S1 is available at International Immunology Online). The addition of TGF-β1 and IL-6 to the cultures induced IL-17 production (Th17) in both WT and VDR KO T cells (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Figure S1 is available at International Immunology Online). VDR KO T cells contained twice as many IL-17-producing cells than WT (VDR KO: 35 ± 4% IL-17 secreting versus WT: 20 ± 2% IL-17 secreting, Fig. 1A and Supplementary Figure S2, available at International Immunology Online). The percentage of IFN-γ-producing cells was similar in Th17 cultures from WT and VDR KO mice (Supplementary Figure S1 is available at International Immunology Online). Very few cells produced both IFN-γ and IL-17 in the WT or VDR KO Th17 cultures (Supplementary Figure S1 is available at International Immunology Online). The percentage of IL-17-secreting T cells in VDR KO CD4+ cells cultured with TGF-β1 only (Treg) was also twice that of the WT cells (VDR KO: 14 ± 2% IL-17 secreting versus WT: 6 ± 2% IL-17 secreting, Fig. 1A and Supplementary Figure S2, available at International Immunology Online). Total IL-17 secretion in the Th17 cultures was significantly higher from VDR KO cells than WT cells (Fig. 1B). Additional cytokines produced by Th17 cells, including mRNA for IL-17F and IL-21, were higher from VDR KO than WT Th17 cultures (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Overproduction of IL-17 in VDR KO T cells. CD4 T cells from WT and VDR KO mice were cultured to induce IL-17 production. Treg cultures included TGF-β1 and Th17 cultures contained IL-6 and TGF-β1. (A) Dot plot showing IL-17-positive CD4+ T cells. Data shown are one representative of six experiments. Numbers indicate percentage of IL-17-producing cells. (B) IL-17A secretion in Th17 cultures of WT and VDR KO T cells. Values are the mean of three individual experiments ± SEM. VDR KO cultures contained significantly more IL-17 than WT. (C) mRNA expression of IL-17F, IL-21, IL-22 and IL23R in Th17 cultured CD4+ T cells. Values are the mean of three experiments ± SEM. *VDR KO cells values were significantly higher than WT, P < 0.05. (D) Th17 induction by TGF-β1 plus IL-21 or IL-6 plus IL-1α. Numbers indicate percentage of IFN-γ- or IL-17-secreting cells in the cultures. Data shown are one representative of two experiments.

There are other combinations of cytokines that will induce Th17 cells (23). To rule out a problem with either the TGF-β1 or the IL-6 pathway in the VDR KO cells, Th17 cells were induced using alternate cytokine pathways. IFN-γ secretion was similar in WT and VDR KO cultures that included TGF-β1/IL-21 or IL-6/IL-1α (Fig. 1D). VDR KO cells overproduced IL-17-secreting cells in cultures that included either TGF-β1/IL-21 or IL-6/IL-1α (Fig. 1D).

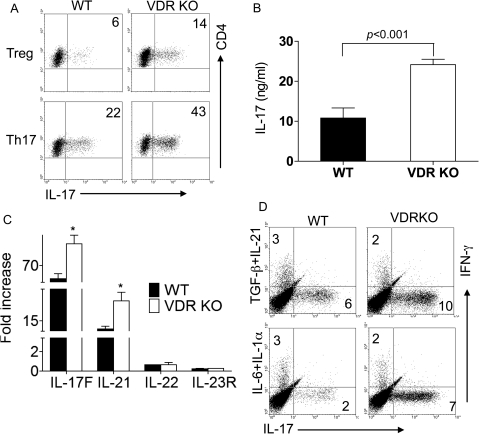

VDR KO CD4+ iTregs are refractory to IL-6

The frequency of naturally occurring Tregs that express FoxP3 in T cells was similar in VDR KO and WT mice (14). Here, we determined the ability of T cells to develop into iTreg when TGF-β1 is added to activated T cells. Th0 cultures contained few FoxP3-expressing T cells in both the WT and the VDR KO CD4+ T cells (Fig. 2A and B). As expected, WT CD4+ T cells were induced to express FoxP3 following culture with TGF-β1 (Fig. 2A and B). Addition of IL-6 inhibited FoxP3 expression in WT CD4+ T cells almost to the level expressed in Th0 cultures (from 42 to 7%, Fig. 2B). Half as many FoxP3+ Treg cells were induced in VDR KO T cells cultured with TGF-β1 as WT T cells (22 versus 42%, Fig. 2B). Unlike WT T cells, addition of IL-6 with TGF-β1 to VDR KO T cells failed to inhibit FoxP3+ expression (Fig. 2A and B). The Treg production of IL-10 followed FoxP3 expression (Fig. 2C). VDR KO Treg cultures produced slightly (not significant) less IL-10 than WT (Fig. 2C), while VDR KO Th17 cultures produced more IL-10 than WT (Fig. 2C). There were no cells that expressed both FoxP3 and IL-17 even in the VDR KO cultures (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Fewer iTreg cells that are refractory to IL-6 inhibition in the absence of the VDR. (A) Expression of FoxP3 in CD4+ T cells cultured in Th0, Th17 and Treg conditions. Values are the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. (B) Representative dot plots for the data shown in A. (C) IL-10 production by WT and VDR KO CD4+ T cells cultured in Th0, Th17 and Treg conditions. Data shown are the mean ± SEM of three individual experiments. VDR KO values were significantly different than WT in the Th17 cultures. The values between WT Treg and WT Th17 were significantly different for both FoxP3 and IL-10. The values between VDR KO T reg and VDR KO Th17 were significantly different for IL-10.

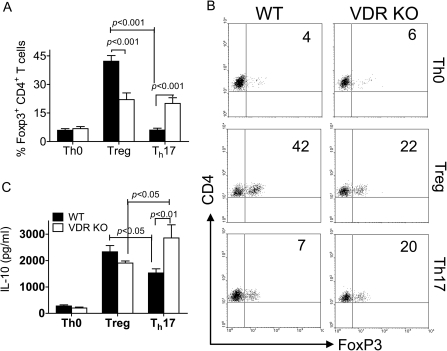

1,25D3 inhibits IL-17

WT CD4+ T cells were treated with 1,25D3 in the presence of different polarizing cytokines. Addition of 1,25D3 to WT T-cell cultures significantly inhibited Th17 differentiation under Treg and Th17 conditions (Fig. 3A and Supplementary Figure S2 is available at International Immunology Online). The percentage of Th17-producing cells decreased in the presence of 1,25D3 from 11 to 7% under Treg condition and 14–7% under Th17-cell culture conditions (Fig. 3A and Supplementary Figure S2B is available at International Immunology Online). 1,25D3-deficient T cells stimulated under Treg conditions had the same very low frequency of IL-17-secreting cells as WT cultures (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Figure S2C is available at International Immunology Online). Under Th17 conditions, the 1,25D3-deficient T cells overproduced IL-17 compared with WT cells (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Figure S2C is available at International Immunology Online). Vitamin D-deficient T cells overproduced IL-17-secreting cells under Treg and Th17 conditions (Fig. 3C and Supplementary Figure S2D is available at International Immunology Online). The magnitude of the increase of IL-17 between 1,25D3 deficient and WT (1.5-fold increase) and vitamin D deficient and WT (2.6-fold increase) was greater in the complete absence of all vitamin D metabolites (vitamin D deficient, Fig. 3C and Supplementary Figure S2 is available at International Immunology Online).

Fig. 3.

Vitamin D or 1,25D3 deficiency induces and 1,25D3 treatment inhibits Th17 cells. Representative dot plots of the CD4+/IL-17-secreting T cells from different in vitro and in vivo 1,25D3 and vitamin D treatments. (A) WT CD4+ T cells were induced to become Treg or Th17 cells in the presence and absence of 25 nM 1,25D3. (B) WT and 1,25D3-deficient CD4+ T cells were induced to become Treg or Th17 cells. (C) Vitamin D sufficient and vitamin D-deficient mice were used as a source of CD4+ T cells for Treg and Th17 cultures, respectively. Data shown are one representative of three experiments. Supplementary Figure S2, available at International Immunology Online, shows the mean ± SEM values.

Decreased naive CD4+ T cells in VDR KO mice

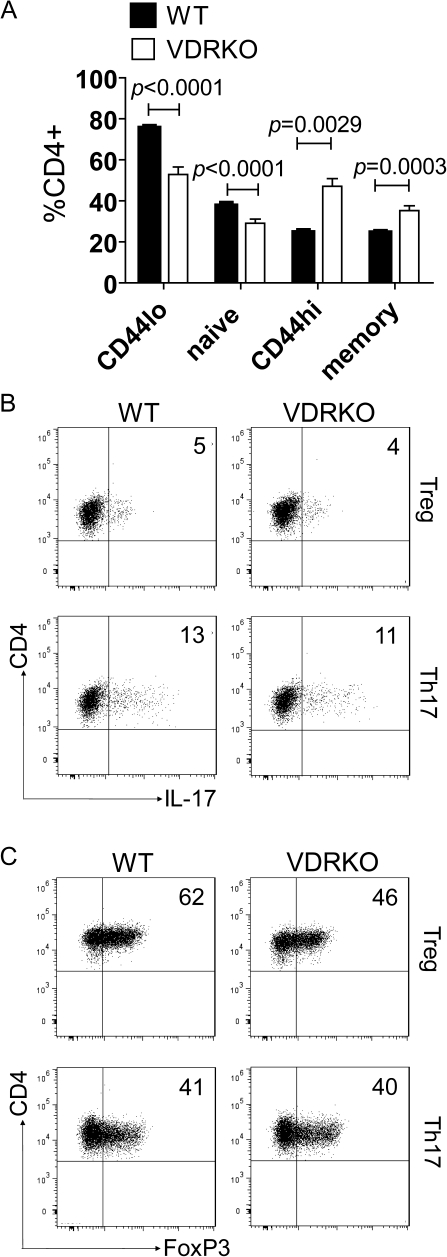

WT and VDR KO CD4+ T cells were stained to determine the prevalence of memory and naive T cells using several different combinations of markers. Significantly, more CD44high T cells (memory/activated) and less CD44low T cells (naive) were present in the CD4 population from VDR KO than WT mice (Fig. 4A). Using additional markers for naive cells that eliminated the activated (CD25+) cells (gating on the CD25−/CD4+ cells and staining for CD62L and CD44) to identify the naive (CD25−/CD62L+/CD44low) and memory (CD25−/CD62L−/CD44high) cells reduced the total numbers of naive cells in both WT and VDR KO mice. Still the VDR KO CD4 cells contained fewer naive T cells than the WT CD4 cells (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

VDR KO mice have significantly fewer naive CD4+ T cells. (A) Bar graphs showing the percentages of naive and memory CD4+ T cells in WT and VDR KO mice. Naive cells were either CD44low (CD44lo) or CD25−/CD62L+/CD44low (naive); memory cells were either CD44high (CD44hi) or CD25−/CD62L−/CD44high (memory). Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 9 for WT and n = 8 for VDR KO). Representative dot plots from one representative experiment of three showing the percentages of (B) IL-17 and (C) FoxP3+ cells from naive CD4+ T cells cultured in either Th17 or Treg conditions. Numbers indicate percentages of IL-17- or FoxP3-positive cells.

Naive T cells (CD4+/CD25−/CD62L+CD44low) were sorted from VDR KO and WT mice and cultured using Th17 and iTreg conditions. The frequency of IL-17-producing cells from VDR KO and WT naive Th17 or iTreg cultures was not different (Fig. 4B). The frequency of FoxP3 staining cells was also measured from the VDR KO and WT naive Th17 and naive iTreg cultures (Fig. 4C). Equal frequencies of FoxP3+ T cells were produced in the naive Th17 cultures from VDR KO and WT mice and fewer FoxP3+ cells were produced in the naive iTreg cultures from VDR KO than WT mice (Fig. 4C). The IL-17 secretion frequencies using naive T cells were unchanged by VDR deficiency (Fig. 4B and C), while there were increased frequencies of IL-17 secretion in VDR KO mice when all CD4+ T cells were used (Fig. 1). Conversely, the decreased frequency of FoxP3 iTreg cultures of VDR KO mice occurs whether naive or bulk CD4+ T cells were used in the cultures (Figs. 2 and 4). The result suggests that the increased representation of Th17 cells in the CD4 bulk cultures from VDR KO mice is likely a result of the increased representation of memory and activated T cells and not a T-cell intrinsic effect of the VDR on IL-17 development of naive T cells. Conversely, for FoxP3+, the VDR must be important for naive T-cell development along the iTreg pathway.

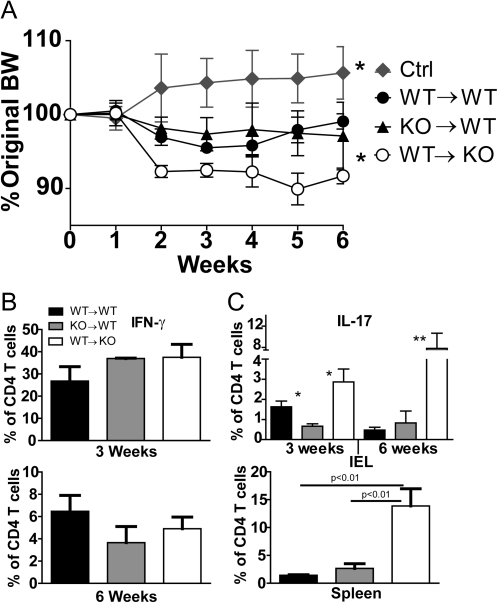

Host effects on the development of Th17 cells

Reciprocal BM chimeras were done to determine the effect of VDR on maturation in vivo and ability to induce IBD when transferred. Donor BM was identified by a difference at the CD45 locus and the following donor–recipient combinations: WT–WT, WT–VDR KO and VDR KO–WT. T cells of donor origin were sorted from the chimeras, stained for CD45RBhigh expression and injected into Rag KO recipients. Beginning at 2 weeks, Rag KO recipients of WT–VDR KO cells weighed less than recipients of the WT–WT or VDR KO–WT cells (Fig. 5A). Throughout the experiment, the recipients of WT–VDR KO cells weighed less than either the VDR KO–WT or the WT–WT recipients (Fig. 5A). The recipients of VDR KO–WT or WT–WT naive cells weighed significantly less than uninjected control (Ctrl) Rag KO mice indicating that all the Rag KO recipients that received naive T cells did develop symptoms of experimental IBD (Fig. 5A). Histological evaluation of the colons also indicated that colitis was developing in recipients of naive T cells (WT–WT score 6.0 ± 0.5, VDR KO–WT score 5.0 ± 0.7, WT–VDR KO score 4.5 ± 1.0) but not the uninjected Rag KO control mice (score 0.7 ± 0.5). There was not a significant difference between the histological severity of the colitis in the Rag KO recipients of WT–WT, WT–VDR KO and VDR KO–WT T cells. To look at the kinetics of the immune response in the Rag KO recipients, a second experiment was terminated at 3 weeks post-transfer. IFN-γ-producing cells were more numerous at 3 weeks post-transfer than at 6 weeks in the IEL of recipient mice (Fig. 5B). The percentage of IFN-γ-secreting cells was similar in Rag KO recipients of all three cell types (Fig. 5B). The percentage of cells producing IL-17 was higher after 6 weeks than 3 weeks post-transfer (Fig. 5C). Significantly, more IL-17-secreting cells were recovered from Rag KO recipients of WT–VDR KO than either the WT–WT or the VDR KO–WT recipients (Fig. 5C) and the increased presence of IL-17-secreting cells corresponded with the more rapid development of weight loss in these mice (Fig. 5A). IL-17-secreting cells were higher in WT–WT than VDR KO–WT recipients at 3 weeks but not 6 weeks post-transfer (Fig. 5C). There were also increased IL-17-producing cells in the spleen of WT–VDR KO recipients at 6 weeks (Fig. 5C). The data suggest that expression of the VDR in the host is an important factor that results in a more rapid initiation of Th17 development in vivo.

Fig. 5.

WT T cells that develop in a VDR KO host induce more rapid IL-17 secretion and weight loss. CD4/CD45RBhigh T cells of donor origin were isolated from VDR KO and WT BM chimeras. The donor-derived CD4/CD45RBhigh T cells were injected into Rag KO recipients. Groups were uninjected control Rag KO (Ctrl), and the following donor → host pairs: WT–WT, VDR KO–WT (KO–WT) and WT–VDR KO (WT–KO). (A) The percent change in BW over time is plotted ± SEM for each group of Rag KO recipients. (B) CD4 T cells were evaluated for IFN-γ production and (C) IL-17 production in either the IEL or the spleen of the Rag KO recipients. Data are mean ± SEM with n = 4 for each group. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01.

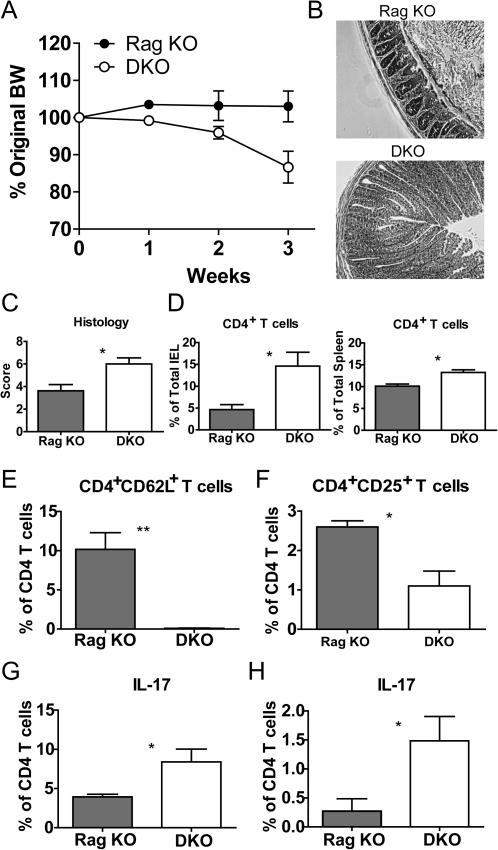

More severe IBD in VDR-deficient hosts

To investigate the role of the VDR in the host during intestinal inflammation, naive WT CD4 T cells were transferred to Rag KO and VDR/Rag double (D) KO mice. DKO recipients began losing weight early and a significant difference was observed by 1 week post-transfer (Fig. 6A). Some of the DKO recipients had lost >20% of their BW by 3 week post-transfer and therefore, all the mice in both groups were sacrificed and analyzed at 3 weeks (Fig. 6A). In keeping with our previous experience, Rag KO recipients had not lost weight by 3 weeks post-transfer and did not show outward signs of IBD (Fig. 6A). There was some inflammation visible in histopathology sections from the Rag KO recipients of naive T cells but the colonic sections of the DKO recipients showed significantly more hyperplasia and inflammation (Fig. 6B). Quantification of the severity of the inflammation showed that histopathology scores in the DKO recipients were significantly higher than in Rag KO recipients of naive T cells (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

VDR expression in non-lymphoid tissues suppresses the development of naive T cells into Th17 cells. WT CD4/CD45RBhigh T cells were transferred to Rag KO and VDR/Rag double (D) KO recipients. (A) The percent change in BW over time is plotted ± SEM for each group, n = 4. The experiment was terminated at 3 week when several of the DKO recipients had lost 20% of their BW. (B) Representative colonic sections of Rag KO (histopathology score of section shown = 3.0) and DKO (histopathology score of section shown = 8.0) recipients sacrificed 3 weeks post-transfer. Scores provided here reflect the score of the sections shown. (C) Histopathology scores for the Rag KO and DKO recipients of naive T cells, n = 4 per group, mean ± SEM. At 3 weeks post-transfer, the composition of the IEL and spleen was evaluated by flow cytometry. (D) CD4+ T cells in the IEL and spleen. (E) CD4/CD62L staining and (F) CD4/CD25 staining of the IEL. (G) The percentage of IL-17 secreting T cells in the IEL and (H) spleen. Values are mean ± SEM and represent two experiments, n = 4 mice per group. Values in the DKO recipient are significantly different than the Rag KO recipient, *P < 0.05.

Increased Th17 response in the absence of the VDR

The IEL and spleen from the DKO and Rag KO recipients of naive T cells were analyzed for the numbers of CD4+ T cells that were present in various tissues at 3 weeks post-transfer (Fig. 6D). The DKO mice had significantly more T cells in the IEL and spleen than Rag KO recipients (Fig. 6D). In addition, to having more CD4+ T cells in the VDR KO host, fewer of the CD4 T cells maintained a naive phenotype as determined by the expression of CD62L (Fig. 6E). There were also more CD4/CD25+ T cells in the Rag KO than the DKO recipient’s IEL (Fig. 6F). The percentage of IFN-γ-secreting CD4+ T cells was not different in Rag KO and DKO recipients (data not shown). Instead, IL-17-producing cells were higher in the IEL and spleen of DKO mice than Rag KO (Fig. 6G and H). The increased presence of IL-17-secreting cells in the gut and periphery of the VDR KO recipient mice suggests that expression of the VDR on accessory cells controls the rate at which Th17 cells develop.

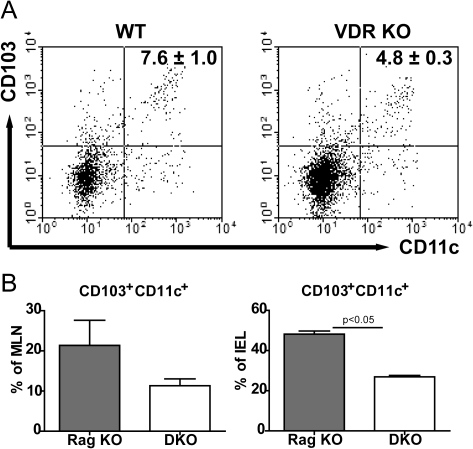

VDR deficiency leads to decreased tolerogenic DCs in the absence of inflammation

To determine if the number of tolerogenic DCs were affected by expression of the VDR, flow cytometric analysis was done for DCs that express CD103 in WT and VDR KO mice that did not have any inflammation. The frequency of total DC populations was not different in WT and VDR KO mice (CD11c+ staining). However, the frequency of tolerogenic CD103+ CD11c+ DCs in VDR KO MLN was significantly lower as compared with WT (Fig. 7A). Because the Rag KO and DKO mice are lymphopenic, they have a larger percentage of total DCs than mice that have T and B cells (Fig. 7A and B). Like the VDR KO mice, DKO mice had decreased frequencies of CD103+CD11c+ DCs in both the MLN and the IEL compared with the VDR-expressing Rag KO mice when analyzed prior to induction of IBD (Fig. 7B). Decreased numbers of DCs that express the tolerogenic phenotype are present in VDR-deficient mice.

Fig. 7.

Decreased tolerogenic DCs in the absence of the VDR. (A) A representative dot plot of the CD103- and CD11c-positive cells in the MLN of WT and VDR KO mice is shown. Values are the mean CD103+/CD11c+ cell frequencies of four mice per group ± SEM. (B) The frequency of CD103+CD11c+ DCs in the MLN and IEL of Rag KO and DKO mice. Values are mean ± SEM and represent two experiments, n = 4 mice per group.

Discussion

In the absence of the VDR or vitamin D, CD4+ T cells made more IL-17. The overproduction of IL-17 was a universal response to multiple IL-17-inducing cytokines. Universal overproduction of IL-17 in response to different cytokine milieus suggests that the VDR affects signals downstream of the different cytokine pathways. Interestingly, the effect was not on the development of new Th17 cells from naive T cells. Instead, the VDR KO T cells had more activated and memory T cells that showed an increased propensity to secrete IL-17 when activated and cultured with either TGF-β1 or TGF-β1 and IL-6. Conversely, 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment inhibited IL-17 production. Vitamin D and the VDR are negative regulators of Th17 cells and direct inhibitors of IL-17 production.

TGF-β1 induced fewer iTreg in VDR KO CD4+ T cells than WT. The decreased expression of FoxP3 was not associated with a significant reduction in IL-10 production from Treg VDR KO T-cell cultures. Surprisingly, IL-6 failed to change the percentage of FoxP3+ T cells in either the bulk CD4 or the naive CD4 VDR KO cultures (Th17, Figs. 2 and 4). This failure to suppress FoxP3 did not interfere with the induction of IL-17-secreting cells in vitro since the VDR KO T cells (naive and bulk) cultured with TGF-β1 and IL-6 had the highest frequency of IL-17-producing T cells (Figs. 1 and 4). The VDR KO Th17 cultures also had the highest amount of IL-10 (Fig. 2). This may seem to be a paradoxical result with the potential in vivo to have higher IL-10 and IL-17 being produced by VDR KO CD4+ T cells. Th17 development is favored in the VDR KO T cells cultured under multiple conditions (IL-6 + IL1α, TGF-β1 + IL-21, TGF-β1, TGF-β1 + IL-6), while IL-10 production was only increased in VDR KO T cells cultured with TGF-β1 and IL-6. It would therefore seem that VDR KO CD4+ T cells more readily develop into Th17 than IL-10-secreting T cells. In vivo development of the T cells would be affected by the levels of different cytokines as well as the types of antigen-presenting cells available during the development of either the Th17 or the IL-10-secreting T cells.

The data show a defect in the induction of iTreg by TGF-β1 in the absence of the VDR. The FoxP3 promoter is regulated by several transcription factors including NFAT, cRel, Creb and STAT5 to FoxP3 promoter (24–26). The VDR has been shown to interact with NFAT and cRel to regulate transcription (27,28). Without the interaction with the VDR, FoxP3 induction may be less efficient. In addition, the expression of FoxP3 is not stable and is affected by the environment. The vitamin A metabolite, retinoic acid (RA), promotes iTreg induction by inducing FoxP3 and promoting TGF-β1 signaling (29). RA induces histone acetylation of the FoxP3 promoter (29). VDR and the vitamin A receptor both accomplish their biological function through a shared heterodimeric partner, the retinoid X receptor. Interactions between vitamin A and vitamin D are well established and there are reports of both cooperation and antogonism (30,31). In this case, the effect of the VDR and vitamin D mirror the effect of vitamin A suggesting that perhaps there is cooperation by vitamin A and D in the induction of iTreg. 1,25D3 has been shown to induce FoxP3 expression in vitro (17). Our data further support a role for expression of the VDR in the non-lymphoid compartment as an indirect way to regulate Th17 cells in vivo. One factor might be the bacterial microflora in the lumen of the intestine that induces development of Th17 cells. Intestinal Th17 cells are absent in germ-free mice (32). Segmented filamentous bacteria are critical for inducing Th17 cells (33). Development of WT CD4+ T cells in the VDR KO host resulted in more IL-17-producing cells suggesting that expression of the VDR in the host is required for normal Th17-cell development. 1,25D3 induces the expression of antibacterial peptides (34). In vivo, one possibility is that vitamin D and the VDR regulate the expression of anti-bacterial peptides that in turn affect the composition of the microbiota between WT and VDR KO mice and the result is more Th17 cells.

Other possible non-lymphoid factors that shape Th17 development are DC subsets. Several subsets of DCs have been described to either increase or decrease the numbers of Th17 cells in the gut (35). Vitamin D agonists have been shown to regulate DC function and to induce tolerogenic DCs in vitro and in vivo (36–38). Tolerogenic DCs have been suggested to provide RA and that shifts the iTreg/Th17 axis in favor of tolerance. Data from humans and mouse models of IBD suggest pathogenic DCs that are CD103− play a role in the pathogenesis of the disease by inducing Th17 cell (35). Conversely, tolerogenic CD103+ DCs have been shown to play an important role in driving the development of Foxp3+ Treg suppressing the development of inflammatory Th17 cells (39). Fewer tolerogenic DCs are present in the gut and MLN of VDR KO mice. Future experiments will determine the role of vitamin D in the development of tolerongenic DCs.

Vitamin D and the VDR are critical regulators of the Th17/iTreg axis. Multiple steps in the development of these T-cell responses require vitamin D. Expression of the VDR is critical for induction of iTreg and suppression of Th17 cells. In the absence of the VDR, Th17 cells are overproduced at the expense of iTreg. In vivo, expression of the VDR is critical for the development of tolerogenic DCs that indirectly affect the numbers of Th17 cells. Other indirect regulators of the Th17/iTreg axis might include the microbial flora, levels of RA or regulation of the vitamin A pathway by vitamin D. A convergence of pathways leads to higher amounts of Th17 cells, fewer iTreg and more severe symptoms of IBD in the absence of the VDR.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at International Immunology Online.

Funding

National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (DK070781); National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine and the Office of Dietary Supplements (AT005378).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Hector DeLuca for the Cyp27B1 KO mice and the members of the Center for Molecular Immunology and Infectious Diseases for lively discussion. Mingcan Xia and Jing Chen for technical assistance.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no financial or commercial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Podolsky DK. Inflammatory bowel disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002;347:417. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yen D, Cheung J, Scheerens H, et al. IL-23 is essential for T cell-mediated colitis and promotes inflammation via IL-17 and IL-6. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116:1310. doi: 10.1172/JCI21404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poussier P, Ning T, Banerjee D, Julius M. A unique subset of self-specific intraintestinal T cells maintains gut integrity. J. Exp. Med. 2002;195:1491. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vignali DA, Collison LW, Workman CJ. How regulatory T cells work. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008;8:523. doi: 10.1038/nri2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coombes JL, Siddiqui KR, Arancibia-Carcamo CV, et al. A functionally specialized population of mucosal CD103+ DCs induces Foxp3+ regulatory T cells via a TGF-beta and retinoic acid-dependent mechanism. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:1757. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Littman D, Rudensky AY. Th17 and regulatory T cells in mediating and restraining inflammation. Cell. 2010;140:845. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen W, Jin W, Hardegen N, et al. Conversion of peripheral CD4+CD25- naive T cells to CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells by TGF-beta induction of transcription factor Foxp3. J. Exp. Med. 2003;198:1875. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang L, Anderson DE, Baecher-Allan C, et al. IL-21 and TGF-beta are required for differentiation of human T(H)17 cells. Nature. 2008;454:350. doi: 10.1038/nature07021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ivanov II, McKenzie BS, Zhou L, et al. The orphan nuclear receptor RORgammat directs the differentiation program of proinflammatory IL-17+ T helper cells. Cell. 2006;126:1121. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang F, Meng G, Strober W. Interactions among the transcription factors Runx1, RORgammat and Foxp3 regulate the differentiation of interleukin 17-producing T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2008;9:1297. doi: 10.1038/ni.1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ivanov II, Frutos Rde L, Manel N, et al. Specific microbiota direct the differentiation of IL-17-producing T-helper cells in the mucosa of the small intestine. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;4:337. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Froicu M, Weaver V, Wynn TA, McDowell MA, Welsh JE, Cantorna MT. A crucial role for the vitamin D receptor in experimental inflammatory bowel diseases. Mol. Endocrinol. 2003;17:2386. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cantorna MT. Vitamin D and its role in immunology: multiple sclerosis, and inflammatory bowel disease. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2006;92:60. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2006.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu S, Bruce D, Froicu M, Weaver V, Cantorna MT. Failure of T cell homing, reduced CD4/CD8alphaalpha intraepithelial lymphocytes, and inflammation in the gut of vitamin D receptor KO mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:20834. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808700106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cantorna MT, Munsick C, Bemiss C, Mahon BD. 1,25-Dihydroxycholecalciferol prevents and ameliorates symptoms of experimental murine inflammatory bowel disease. J. Nutr. 2000;130:2648. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.11.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu S, Cantorna MT. The vitamin D receptor is required for iNKT cell development. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:5207. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711558105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daniel C, Sartory NA, Zahn N, Radeke HH, Stein JM. Immune modulatory treatment of trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid colitis with calcitriol is associated with a change of a T helper (Th) 1/Th17 to a Th2 and regulatory T cell profile. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2008;324:23. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.127209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang SH, Chung Y, Dong C. Vitamin D suppresses Th17 cytokine production by inducing C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) expression. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:38751. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C110.185777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colin EM, Asmawidjaja PS, van Hamburg JP, et al. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 modulates Th17 polarization and interleukin-22 expression by memory T cells from patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:132. doi: 10.1002/art.25043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang J, Zhou R, Luger D, et al. Calcitriol suppresses antiretinal autoimmunity through inhibitory effects on the Th17 effector response. J. Immunol. 2009;182:4624. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0801543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Veldhoen M, Hocking RJ, Atkins CJ, Locksley RM, Stockinger B. TGFbeta in the context of an inflammatory cytokine milieu supports de novo differentiation of IL-17-producing T cells. Immunity. 2006;24:179. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou L, Lopes JE, Chong MM, et al. TGF-beta-induced Foxp3 inhibits T(H)17 cell differentiation by antagonizing RORgammat function. Nature. 2008;453:236. doi: 10.1038/nature06878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Korn T, Bettelli E, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. IL-17 and Th17 cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2009;27:485. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim H, Leonard WJ. CREB/ATF-dependent T cell receptor-induced FoxP3 gene expression: a role for DNA methylation. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:1543. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Long M, Park SG, Strickland I, Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Nuclear factor-kappaB modulates regulatory T cell development by directly regulating expression of Foxp3 transcription factor. Immunity. 2009;31:921. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng Y, Josefowicz S, Chaudhry A, Peng XP, Forbush K, Rudensky AY. Role of conserved non-coding DNA elements in the Foxp3 gene in regulatory T-cell fate. Nature. 2010;463:808. doi: 10.1038/nature08750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alroy I, Towers TL, Freedman LP. Transcriptional repression of the interleukin-2 gene by vitamin D3: direct inhibition of NFATp/AP-1 complex formation by a nuclear hormone receptor. Mol. Cell Biol. 1995;15:5789. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.10.5789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lyakh LA, Sanford M, Chekol S, Young HA, Roberts AB. TGF-beta and vitamin D3 utilize distinct pathways to suppress IL-12 production and modulate rapid differentiation of human monocytes into CD83+ dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 2005;174:2061. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.4.2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim CH. Regulation of FoxP3 regulatory T cells and Th17 cells by retinoids. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2008;2008:416910. doi: 10.1155/2008/416910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rohde CM, DeLuca HF. All-trans retinoic acid antagonizes the action of calciferol and its active metabolite, 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol, in rats. J. Nutr. 2005;135:1647. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.7.1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Defacque H, Sevilla C, Piquemal D, Rochette-Egly C, Marti J, Commes T. Potentiation of VD-induced monocytic leukemia cell differentiation by retinoids involves both RAR and RXR signaling pathways. Leukemia. 1997;11:221. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2400568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Niess JH, Leithauser F, Adler G, Reimann J. Commensal gut flora drives the expansion of proinflammatory CD4 T cells in the colonic lamina propria under normal and inflammatory conditions. J. Immunol. 2008;180:559. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.1.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ivanov II, Atarashi K, Manel N, et al. Induction of intestinal Th17 cells by segmented filamentous bacteria. Cell. 2009;139:485. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu PT, Stenger S, Li H, et al. Toll-like receptor triggering of a vitamin D-mediated human antimicrobial response. Science. 2006;311:1770. doi: 10.1126/science.1123933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rescigno M, Di Sabatino A. Dendritic cells in intestinal homeostasis and disease. J. Clin. Invest. 2009;119:2441. doi: 10.1172/JCI39134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adorini L, Penna G. Dendritic cell tolerogenicity: a key mechanism in immunomodulation by vitamin D receptor agonists. Hum. Immunol. 2009;70:345. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2009.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adorini L, Penna G, Giarratana N, Uskokovic M. Tolerogenic dendritic cells induced by vitamin D receptor ligands enhance regulatory T cells inhibiting allograft rejection and autoimmune diseases. J. Cell. Biochem. 2003;88:227. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Griffin MD, Lutz W, Phan VA, Bachman LA, McKean DJ, Kumar R. Dendritic cell modulation by 1alpha,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3 and its analogs: a vitamin D receptor-dependent pathway that promotes a persistent state of immaturity in vitro and in vivo. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:6800. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121172198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Siddiqui KR, Laffont S, Powrie F. E-cadherin marks a subset of inflammatory dendritic cells that promote T cell-mediated colitis. Immunity. 2010;32:557. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.