Abstract

Background:

This study explored the relationship between body mass index (BMI) and weight perception, self-esteem, positive body image, food beliefs, and mental health status, along with any gender differences in weight perception, in a sample of adolescents in Spain.

Methods:

The sample comprised 85 students (53 females and 32 males, mean age 17.4 ± 5.5 years) with no psychiatric history who were recruited from a high school in Écija, Seville. Weight and height were recorded for all participants, who were then classified according to whether they perceived themselves as slightly overweight, very overweight, very underweight, slightly underweight, or about the right weight, using the question “How do you think of yourself in terms of weight?”. Finally, a series of questionnaires were administered, including the Irrational Food Beliefs Scale, Body Appreciation Scale, Self Esteem Scale, and General Health Questionnaire.

Results:

Overall, 23.5% of participants misperceived their weight. Taking into account only those with a normal BMI (percentile 5–85), there was a significant gender difference with respect to those who perceived themselves as overweight (slightly overweight and very overweight); 13.9% of females and 7.9% of males perceived themselves as overweight (χ2 = 3.957, P < 0.05). There was a significant difference for age, with participants who perceived their weight adequately being of mean age 16.34 ± 3.17 years and those who misperceived their weight being of mean age 18.50 ± 4.02 years (F = 3.112, P < 0.05).

Conclusion:

Misperception of overweight seems to be more frequent in female adolescents, and mainly among older ones. Misperception of being overweight is associated with a less positive body image, and the perception of being very underweight is associated with higher scores for general psychopathology.

Keywords: weight misperception, self-esteem, positive body image, psychological distress, food beliefs

Introduction

Despite the marked increase in overweight/obesity rates in childhood and adolescence, it seems that the stigma of being overweight has worsened in recent years.1 In Western countries, including Spain, there is a negative perception of obese people, who are perceived as excluded, shy, touchy, anxious, rejected, insecure, and passive by university students and patients with disordered eating.2 Moreover, while obese people more frequently use positive adjectives to describe themselves, other groups, including the aforementioned, tend to use adjectives with more negative connotations to describe obese people.3

Many studies have observed an association between overweight/obesity and negative psychosocial correlates and consequences. Among preadolescent girls, a positive and significant correlation between the Eating Behaviors and Body Image Test and its subscale of Body Image Dissatisfaction/Restrictive, and body mass index (BMI) has been described.4 For young adult males, a positive correlation between BMI and the Questionnaire of Influences on Body Shape Model has also been described, despite this correlation not being found in adolescent boys.5,6 A high BMI is usually associated with a higher risk for eating disorders, higher body dissatisfaction, poorer body image and quality of life,7–9 as well as with more irrational food beliefs.10

Misperception of weight status is defined as a discordance between an individual’s actual body weight and his/her perception of their weight status. This misperception has repeatedly been documented among overweight and obese adults, and it has been hypothesized that weight misperception among overweight and obese individuals may preclude adoption of healthy attitudes and behaviors, perhaps as a result of lower motivation for weight loss. Overweight and obese individuals who consider their weight to be healthy, for example, might not try to lose weight and might be less inclined to eat healthily and be physically active.11 On the other hand, some evidence indicates that weight misperception among overweight and obese individuals might be associated with healthy behaviors (eg, better quality of diet, more physical activity, and less sedentary behavior).11,12

Misperception of overweight/obesity in individuals with high BMI is a relevant but understudied area. Previous studies have suggested that misperception of overweight varies by gender, amongst other variables. It has been reported that females are more likely to perceive themselves as overweight than are males, even at the same measured BMI.13–15 Misperception of overweight/obesity among adolescents of normal weight can have negative consequences, including body dissatisfaction leading to dieting, which is a clear risk factor for disordered eating.16

With respect to psychological and psychopathological variables, few studies have focused on the relationship between perceived weight and self-esteem,17,18 or on the relationship between BMI and positive body image.19,20 The same applies to the relationship between perceived overweight and food beliefs. In general, even less research has been done on perceived weight status, that may account for the conflicting evidence for a relationship between documented overweight and its negative psychological correlates.21,22

Based on results of previous research, the aims of the current study were to explore possible gender differences with respect to weight misperception and to analyze the relationship between that misperception and other variables, such as self-esteem, body appreciation, and food beliefs among adolescents. The following hypotheses were investigated: female adolescents have a higher level of weight misperception and lower body appreciation than male adolescents; those who perceive their weight status as “very overweight” have a poorer body image; a positive body image can be predicted by BMI as well as by psychological variables, such as self-esteem; and there is a relationship between BMI, self-esteem, body appreciation, and general psychopathology.

Methods and materials

Participants

The sample comprised 85 students (53 female [62.40%] and 32 male [37.60%], of mean age 17.4 ± 5.5 years), recruited from a high school in Écija, Seville. None had any psychiatric history, according to a brief questionnaire at the time of obtaining informed consent. None showed incomprehension and/or language difficulties or refused to participate.

Instruments and measures

Perceived overweight

As in a previous study,23 respondents were classified as “perceived overweight” if they responded “slightly overweight” or “very overweight” to the question “How do you think of yourself in terms of weight?” when other possible answers were “very underweight”, “slightly underweight”, and “about the right weight”.

Body mass index

BMI was calculated as the relationship between weight (kg) and height squared (m). Weight and height were taken in individual sessions, with the participants in the standing position, barefoot, and in light garments. A stadiometer (Atlántida S13; Básculas y Balanzas Añó-Sayol, Barcelona, Spain) was used.

Irrational food beliefs scale

This instrument was developed to measure cognitive distortions and inappropriate attitudes or beliefs about food.24 The scale has shown adequate psychometric properties, having two subscales corresponding to the irrational food beliefs subscale and the rational food beliefs subscale, with a Cronbach’s coefficient α of 0.89 and 0.70, respectively. The scale consists of 57 items, 41 on the irrational beliefs subscale and 16 on the rational beliefs subscale. The Spanish version was used in the current study, which has shown adequate internal consistency (Cronbach’s α coefficient 0.78–0.88).10

Body appreciation scale

This scale19 is a 13-item instrument, comprising a single dimension and showing adequate internal consistency and construct validity, and is useful for studying the positive aspects of body image. The Spanish version was used, which has adequate internal consistency (Cronbach’s α coefficient 0.91).20

Self-esteem scale

The scale comprises 10 items scored using a Likert format (from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”); the higher the score, the higher the degree of self-esteem. The Spanish version of the instrument shows adequate internal consistency (Cronbach’s α coefficient 0.87), test-retest reliability (r = 0.72), and construct validity.25,26

General health questionnaire

We used the Spanish version of this general psychopathology screening instrument, which shows an adequate discriminative power (psychiatric case–no case) and is easily administered. The questionnaire was designed to detect the presence of psychiatric cases in community and nonpsychiatric clinical settings, and comprises four seven-item scales, ie, somatic symptoms, anxiety and insomnia, social dysfunction, and depression. Each item consists of four possible answers, which are evaluated as 0 (the first two options) or 1 (the last two options). Those evaluated with 0 points indicate absence of psychopathological problems, and those evaluated with 1 point indicate problems. By means of this scale of 0, 0, 1, 1, the results are utilized to identify psychiatric cases. A higher final score indicates greater psychopathology. The instrument has shown a sensitivity of 76.9%–84.6% and specificity of 82%–90.2%, depending on the cutoff points used. Because different cutoff points have been used, only the total score and the scores on the four subscales were considered in the present study. The General Health Questionnaire has been suggested as a tool for identifying emerging as well as chronic problems (C-GHQ), scored in the latter case on the scale of 0, 1, 1, 1. For this study, we used both the General Health Questionnaire and C-GHQ.27

Procedure

After obtaining informed consent from both the participants and their parents, the aforementioned questionnaires and scales in group sessions were completed during a week of activities on “Healthy eating habits and their disorders”, with no time limits. A psychologist, a nutritionist, and a teacher supervised the sessions, showing the participants how to complete the questionnaires and scales, and ensuring that they understood the instructions. Sessions took place in a suitable setting for responding to the task. All participants volunteered to take part in the study, and none received any compensation for completing the questionnaires and scales. Anthropometric measurements were performed by a nutritionist during individual sessions.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. To study possible gender differences in misperception of weight, we analyzed the proportion of males and females using χ2. An analysis of variance was performed to study gender differences with respect to the variables included in the study (perceived overweight, irrational food beliefs, body appreciation, self-esteem, and general psychopathology). Another analysis of variance was undertaken to study age differences in the participants who misperceived their body weight. Associations between variables were investigated using the Pearson correlation coefficient. Finally, a stepwise multiple regression analysis was used to analyze which variables might be predictive of a positive body image.

Results

Descriptive and gender differences

Participants were classified on a percentile (P) basis as underweight (P < 5), of normal weight (P 5–84.9), overweight (P 85–94.9), or obese (P > 95).28 There were no gender differences with respect to the proportion of participants who perceived their weight adequately or inadequately. Overall, 23.5% of the participants misperceived their weight. Nevertheless, taking into account only those with normal BMI (P 5–84.9), there was a significant gender difference with respect to those who perceived themselves as slightly overweight or very overweight; 13.9% of females and 7.4% of males perceived themselves as overweight (χ2 = 3.957, P < 0.05). There was a significant difference with regard to age, with a mean age of 16.34 ± 3.17 years in participants who perceived their weight adequately and a mean age of 18.50 ± 4.02 years in those who misperceived their weight (F = 3.112, P < 0.05). Participants who perceived themselves as “slightly overweight” were older than those who did not (21.36 ± 1.20 years).

Considering the different psychological variables, there was a significant difference with respect to body appreciation, with higher mean scores in males (51.57 ± 9.05) than in females (45.91 ± 9.79, F = 7.334, P < 0.01). With regard to general psychopathology, there were some significant differences between males and females, including for the anxiety-insomnia subscale (1.38 ± 1.26 and 0.63 ± 0.57, for females and males, respectively; F = 4.691, P < 0.05), and for total score on the General Health Questionnaire (mean 3.56 ± 2.55 and 1.81 ± 0.88 for females and males, respectively; F = 3.894, P < 0.05). Finally, a significant difference was found for irrational food beliefs, with a higher mean score in females than in males (46.60 ± 5.99 versus 42.16 ± 6.16, respectively; F = 4.212, P < 0.05).

Weight misperception and psychological variables

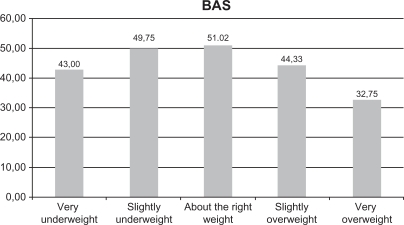

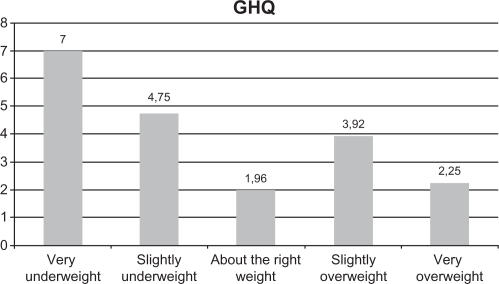

Mean score on positive body image, measured by the Body Appreciation Scale, was the lowest among participants who perceived themselves as “very overweight” (32.75 ± 10.50) and highest for those who perceived themselves as “about the right weight” (51.02 ± 8.07, F = 6.357, P < 0.01, see Figure 1). For general psychopathology, those who perceived themselves as “very underweight” had the highest mean score on the General Health Questionnaire (7.00 ± 3.63 and 3.22 ± 2.21 for those perceiving themselves as “very underweight” and the rest of the participants, respectively). The lowest score was found in those who perceived themselves as being about the right weight (F = 3.995, P < 0.01, see Figure 2). Taking BMI into account, those with a normal BMI (P 5–84.9) had the highest scores on the Irrational Food Beliefs Scale (45.24 ± 4.67 and 41.25 ± 5.68 for those with normal BMI and the rest of the participants, respectively).

Figure 1.

Mean body appreciation scale scores considering different weight perceptions. F = 6.357; P < 0.01.

Abbreviation: BAS, body appreciation scale.

Figure 2.

Mean general health questionnaire scores considering different weight perceptions. F = 3.995; P < 0.01.

Abbreviation: GHQ, General Health Questionnaire.

Association between variables

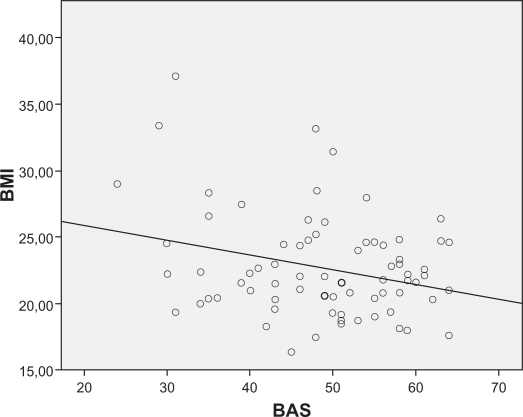

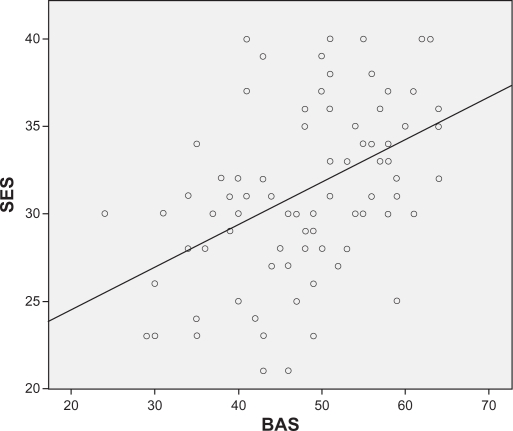

There were some significant correlations between variables, as shown in Table 1. Age was negatively correlated with body appreciation (r = −0.27, P < 0.05) and with irrational food beliefs (r = −0.31, P < 0.01). A linear regression analysis was performed to explore possible predictors of a positive body image, entering body appreciation as a dependent variable and the rest of variables as independent variables. Self-esteem (β = 0.529, t = 5.525, P < 0.001) and BMI (β = −0.273, t = −2.850, P < 0.01) predicted a positive body image. Neither age nor general psychopathology predicted scores for body image appreciation (see Figures 3 and 4).

Table 1.

Correlations between body mass index, self-esteem, general psychopathology, and body appreciation

| Body mass index | Self-esteem | General psychopathology | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body appreciation | −0.272b | 0.472a | −0.312a |

| General psychopathology | −0.057 | −0.357a | |

| Self-esteem | −0.017 |

Notes:

P < 0.01;

P < 0.05.

Figure 3.

Correlations between body mass index and body appreciation.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; BAS, body appreciation scale.

Figure 4.

Correlations between self esteem scale and body appreciation.

Abbreviations: SES, self-esteem scale; BAS, body appreciation scale.

Discussion

In contrast with a previous study23 which found that a substantial proportion of adolescents of normal weight misperceived themselves as overweight (25.1% of females and 8% of males, respectively), our proportions of females and males of normal weight who misperceived themselves as overweight were 13.9% and 7.4%, respectively. In another study, which included only females aged 18–25 years, 23% of overweight and 16% of normal-weight participants were misperceivers.29 These differences could be explained by variables related to the different social environments in which each study was performed. Nevertheless, despite these different reported proportions, it seems that females are more likely than males to misperceive themselves as overweight.11–13 In a recent study of overweight and obese adults (aged 20 years and older), 75% of participants misperceived their weight, this misperception being understood as participants reporting themselves as underweight or about the right weight.30 As a result of these findings, misperception of weight seems to be common both with regard to normal weight perception among overweight/obese people and perception of overweight/obesity among people of normal weight.

Any discrepancy between perceived weight and measured BMI enables identification of weight misperception, which can then be related to other psychological variables. With respect to age, the fact that those participants who misperceived their weight were older than those who did not is consistent with other results in our study, eg, the negative correlation between age and Body Appreciation Scale.

It seems that the older an adolescent is, the higher the tendency for misperception of body weight. The negative correlation between body appreciation and BMI suggests that body appreciation lessens as weight increases, this being consistent with the findings of other studies.20,31–33 Taking into account that a positive body image is associated with lower scores in general psychopathology and with higher scores for self-esteem, a worse body image, poor self-esteem, and more symptoms of general psychopathology could be involved in the misperception of weight. Nevertheless, this study does not confirm the finding of a previous one in which a relationship between misperceived overweight and self-esteem was reported.23 In the current study, there were no subgroups (misperceiving and not misperceiving their weight) showing significantly lower self-esteem, while other studies have found some differences taking into account race, ethnic, and cultural factors.23,34–36 A previous suggestion that self-esteem is a possible moderator of the relationship between weight and misperceived weight has not been focused on specifically in this study. The negative association between self-esteem and general psychopathology, as well as the negative association between a positive body image and general psychopathology, could represent an association between body perception, body-perception related variables, and symptoms of psychological distress, which has been described previously.37

The relevance of body image during adolescence makes it necessary to study body appreciation in relation to possible disturbances in eating habits,20 as well as the degree of misperception of body weight, which at least is related to dieting. Misperception of overweight among adolescents of normal weight can have negative consequences. It has been reported in the literature that a combination of overweight misperception and dieting can increase the risk of both obesity and restrictive eating disorders.38–40 Weight perception and its relationship with weight control practices have also been reported, with some sociocultural variations.11,21,34,41

Unhealthy eating as a consequence of misperceived overweight has also been described,21 so misperception of overweight and its relationship with psychological distress (eg, more general psychopathology, less self-esteem, less positive body image) could have clinical repercussions. On the other hand, overweight persons misperceiving themselves as being of normal weight could adopt an unhealthy diet and perpetuate obesity-promoting behaviors.23 Longitudinal studies need to be developed in the future to explore the association between weight misperception and eating habits.

Psychosocial variables associated with self-esteem, depression, suicidal behavior, eating disorders, and substance abuse have been studied.42–46 However, few studies have investigated the association between perceived overweight and self-esteem.23 There is also a dearth of published studies on the positive aspects of body image, which has been pointed out by various authors.47,48 As mentioned, more studies are necessary to explore the relationship between weight misperception and self-esteem.

Misperception of overweight and other psychosocial variables contribute to the risk for disordered eating behaviors, as we have found in a previous study.48 The relationship between weight misperception and psychological variables, in particular age, needs to be taken into account in the primary prevention of eating disorders.

Limitations

Like other studies in this field, our research was cross-sectional, so it does not allow us to explore the chronological order of the associations between weight perception and other psychological variables. The influence of these associations on the onset of disordered eating behavior needs to be studied longitudinally. We did not explore different degrees of self-esteem using cutoff points, and used only the correlation between self-esteem and other variables, as well as possible differences with regard to total scores on self-esteem. A bigger sample size and use of cutoff points could contribute to a better understanding of the relationship between self-esteem and weight misperception. Due to the fact that all participants were attending a private high school, this sample was not heterogeneous enough to enable our results to be generalized to other social settings.

Conclusion

Misperception of overweight seems to be more frequent in female adolescents than their male counterparts, and mainly occurs in older adolescents. Misperception of overweight is associated with a less positive body image, and perception of weight status as very underweight is associated with higher scores on general psychopathology. Normal BMI is associated with more rational food beliefs.

The combination of weight misperception and other psychological variables, eg, body image and self-esteem, could contribute to a high level of distress, putting adolescents at risk of disordered eating behavior. Moreover, an unhealthy diet as a result of misperceived overweight in a teenager of normal weight could contribute to the onset and perpetuation of an eating disorder. The same applies to overweight individuals who misperceive themselves as being of normal weight. Longitudinal studies are needed to explore these relationships further.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of the Eating Disorders Unit of the Behavioral Sciences Institute, as well as the support of the Professional School SAFA, Écija, Seville, in the preparation of this manuscript. We are grateful to Sabine Bergmann for her technical support.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report that there are no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Latner JD, Stunkard AJ. Getting worse: the stigmatization of obese children. Obes Res. 2003;11:452–456. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jáuregui Lobera I, López Polo IM, Montaña González MT, Morales Millán MT. Perception of obesity in university students and in patients with eating disorders. Nutr Hosp. 2008;23:226–233. Spanish. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jáuregui Lobera I, Rivas Fernández M, Montaña González MT, Morales Millán MT. The influence of stereotypes on obesity perception. Nutr Hosp. 2008;23:319–325. Spanish. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jáuregui Lobera I, Perez-Lancho C, Gomez-Capitan MJ, Duran E, Garrido O. Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the Eating Behaviours and Body Image Test for Preadolescent Girls (EBBIT) Eat Weight Disord. 2009;14:e22–e28. doi: 10.1007/BF03354624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toro J, Gila A, Castro J, Pombo C, Guete O. Body image, risk factors for eating disorders and sociocultural influences in Spanish adolescents. Eat Weight Disord. 2005;10:91–97. doi: 10.1007/BF03327530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jáuregui Lobera I, Tomillo Cid S, Santiago Fernández MJ, Bolaños Ríos P. Body shape model, physical activity and eating behaviour. Nutr Hosp. 2011;26:201–207. Spanish. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waaddegaard M, Davidsen M, Kjoller M. Comparison between risk behaviour for eating disorders and SF-36 and perceived stress among 16–29-year old Danish females. Ugeskr Laeger. 2009;171:709–712. Danish. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arroyo M, Ansotegui L, Pereira E, et al. Body composition assesment and body image perception in a group of female University students from the Basque Country. Nutr Hosp. 2008;23:366–372. Spanish. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cash TF, Jakatdar TA, Williams EF. The Body Image Quality of Life Inventory: further validation with college men and females. Body Image. 2004;1:279–287. doi: 10.1016/S1740-1445(03)00023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jáuregui Lobera I, Bolaños Ríos P. Spanish version of the irrational food beliefs scale. Nutr Hosp. 2010;25:852–859. Spanish. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duncan DT, Wolin KY, Scharoun-Lee M, Ding EL, Warner ET, Bennett GG. Does perception equal reality? weight misperception in relation to weight-related attitudes and behaviors among overweight and obese US adults. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8:20. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-8-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lynch E, Liu K, Wei GS, Spring B, Kiefe C, Greenland P. The relation between body size perception and change in body mass index over 13 years: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169:857–866. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kilpatrick M, Ohannessian C, Bartholomew JB. Adolescent weight management and perceptions: an analysis of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. J Sch Health. 1999;69:148–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1999.tb04173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pritchard ME, King SL, Czajka-Narins DM. Adolescent body mass indices and self-perception. Adolescence. 1997;32:863–880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ter Bogt TF, van Dorsselaer SA, Monshouwer K, Verdurmen JE, Engels RC, Vollebergh WA. Body mass index and body weight perception as risk factors for internalizing and externalizing problem behavior among adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Birmingham CL, Beumont P. Medical Management of Eating Disorders. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siegel JM, Yancey AK, Aneshensel CS, Schuler R. Body image, perceived pubertal timing, and adolescent mental health. J Adolesc Health. 1999;25:155–165. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00160-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xie B, Liu C, Chou CP, et al. Weight perception and psychological factors in Chinese adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2003;33:202–210. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00099-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Avalos L, Tylka TL, Wood-Barcalow N. The Body Appreciation Scale: development and psychometric evaluation. Body Image. 2005;2:285–297. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jáuregui Lobera I, Bolaños Ríos P. Spanish version of the Body Appreciation Scale (BAS) for adolescents. Span J Psychol. 2011;14:411–420. doi: 10.5209/rev_sjop.2011.v14.n1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neff LJ, Sargent RG, McKeown RE, Jackson KL, Valois RF. Black white differences in body size perceptions and weight management practices among adolescent females. J Adolesc Health. 1997;20:459–465. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(96)00273-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robinson TN, Killen JD, Litt IF, et al. Ethnicity and body dissatisfaction: are Hispanic and Asian girls at increased risk for eating disorders? J Adolesc Health. 1996;19:384–393. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(96)00087-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perrin EM, Boone-Heinonen J, Field AE, Coyne-Beasley T, Gordon-Larsen P. Perception of overweight and self-esteem during adolescence. Int J Eat Disord. 2010;43:447–454. doi: 10.1002/eat.20710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Osberg TM, Poland D, Aguayo G, MacDougall S. The Irrational Food Beliefs Scale: development and validation. Eat Behav. 2008;9:25–40. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenberg M. Society and the Adolescent Self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vázquez AJ, Jiménez R, Vázquez-Morejón R. The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale: Reliability and validity in clinical samples of Spanish population. Apuntes de Psicologia. 2004;22:247–255. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lobo A, Pérez-Echevarria MJ, Artal J. Validity of the scaled version of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28) in a Spanish population. Psychol Med. 1986;16:135–140. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700002579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ. 2000;320:1240–1243. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7244.1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rahman M, Berenson AB. Self-perception of weight and its association with weight-related behaviors in young, reproductive-aged females. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:1274–1280. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181fdfc47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marques-Vidal P, Melich-Cerveira J, Marcelino G, Paccaud F. High- and persistent- body-weight misperception levels in overweight and obese Swiss adults, 1997–2007. Int J Obes (Lond) Jan 25, 2011. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Martz DM, Sturgis ET, Gustafson SB. Development and preliminary validation of the cognitive behavioral dieting scale. Int J Eat Disord. 1996;19:297–309. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199604)19:3<297::AID-EAT9>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ohring JA, Graber JA, Brooks-Gunn J. Girls’ recurrent and concurrent body dissatisfaction: correlates and consequences over 8 years. Int J Eat Disord. 2002;31:404–415. doi: 10.1002/eat.10049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stice E, Whitenton K. Risk factors for body dissatisfaction in adolescent girls: a longitudinal investigation. Dev Psychol. 2002;38:669–678. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.5.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neumark-Sztainer D, Croll J, Story M, Hannan PJ, French SA, Perry C. Ethnic/racial differences in weight-related concerns and behaviors among adolescent girls and boys: findings from Project EAT. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:963–974. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00486-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robinson TN, Chang JY, Haydel KF, Killen JD. Overweight concerns and body dissatisfaction among third-grade children: the impacts of ethnicity and socioeconomic status. J Pediatr. 2001;138:181–187. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.110526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nichter M. Fat Talk: what Girls and their Parents say about Dieting. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xie B, Chou CP, Spruijt-Metz D, et al. Longitudinal analysis of weight perception and psychological factors in Chinese adolescents. Am J Health Behav. 2011;35:92–104. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.35.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strauss RS. Self-reported weight status and dieting in a cross sectional sample of young adolescents: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:741–747. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.7.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Field AE, Austin SB, Taylor CB, et al. Relation between dieting and weight change among preadolescents and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2003;112:900–906. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.4.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Guo J, Story M, Haines J, Eisenberg M. Obesity, disordered eating, and eating disorders in a longitudinal study of adolescents: how do dieters fare 5 years later? J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106:559–568. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heinonen K, Raikkonen K, Keltikangas-Jarvinen L. Maternal perceptions and adolescent self-esteem: a six-year longitudinal study. Adolescence. 2003;38:669–687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hammond WA, Romney DM. Cognitive factors contributing to adolescent depression. J Youth Adolesc. 1995;24:667–683. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wichstrom L. Predictors of adolescent suicide attempts: a nationally representative longitudinal study of Norwegian adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:603–610. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200005000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilcox M, Sattler DN. The relationship between eating disorders and depression. J Soc Psychol. 1996;136:269–271. doi: 10.1080/00224545.1996.9714005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scheier LM, Botvin GJ, Griffin KW, Diaz T. Dynamic growth models of self-esteem and adolescent alcohol use. J Early Adolesc. 2000;20:178–210. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cash TF. Cognitive-bahavioral perspectives on body image. In: Cash TF, Pruzinsky T, editors. Body Image: a Handbook of Theory, Research, and Clinical Practice. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Striegel-Moore RH, Cachelin FM. Body image concerns and disordered eating in adolescent girls: risk and protective factors. In: Johnson NG, Roberts MC, editors. Beyond Appearance: a New Look at Adolescent Girls. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jáuregui Lobera I, León Lozano P, Bolaños Ríos P, et al. Traditional and new strategies in the primary prevention of eating disorders: a comparative study in Spanish adolescents. Int J Gen Med. 2010;3:263–272. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S13056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]