Abstract

BACKGROUND

Our goal was to characterize hospice enrollment and aggressiveness of care for pancreatic cancer patients at the end of life.

METHODS

We used Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) and linked Medicare claims data (1992–2006) to identify patients with pancreatic cancer who had died (n= 22,818). We evaluated hospice use, hospice enrollment ≥4 weeks before death, and aggressiveness of care as measured by receipt of chemotherapy, acute care hospitalization, and intensive care unit (ICU) admission in the last month of life.

RESULTS

Overall, 56.9% of patients enrolled in hospice, and 35.9% of hospice users enrolled for four weeks or more. Hospice use increased from 36.2% in 1992–1994 to 67.2% in 2004–2006 (P<0.0001). Admission to the ICU and receipt of chemotherapy in the last month of life increased from 15.5% to 19.6% (P<0.0001) and 8.1% to 16.4% (P<0.0001), respectively. Among patients with locoregional disease, those who underwent resection were less likely to enroll in hospice before death and much less likely to enroll early. They were also more likely to receive chemotherapy (14% vs. 9%, P<0.0001), be admitted to an acute care hospital (61% vs. 53%, P<0.0001), and be admitted to an ICU (27% vs. 15%, P<0.0001) in the last month of life.

CONCLUSIONS

While hospice use increased over time, there was a simultaneous decrease in early enrollment and increase in aggressive care at the end of life for patients with pancreatic cancer.

CONDENSED

This study examined hospice enrollment and aggressiveness of care for pancreatic cancer patients at the end of life. While hospice use increased over time, there was a simultaneous increase in aggressive care at the end of life for patients with pancreatic cancer.

Keywords: hospice care, aged, pancreatic neoplasms, SEER Program, Medicare, terminal care

INTRODUCTION

In 2010, there were 43,140 new cases of pancreatic cancer and 36,800 deaths in the U.S., making it the fourth leading cause of cancer-related death in men and women.1 Pancreatic cancer is an aggressive cancer; over two-thirds of patients present with advanced stage disease,2 and for all patients, the median survival is less than 6 months and 5-year survival less than 4%.3 Patients with pancreatic cancer, particularly advanced stage disease, experience symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, weight loss, obstructive jaundice, and intractable pain. Studies show increased intensity of symptoms and a sharp decline in quality of life in the 8 weeks before death in patients with advanced stage disease.4,5

Hospice care improves management of symptoms and quality of life for patients at the end of life.6–8 Rather than hastening death, hospice care may be associated with longer survival for some patients.9, 10 Hospice services are covered under Medicare Part A for terminally ill patients and include skilled nursing care, home health services, coverage of drugs for symptom control and pain relief, supplies for the terminal illness and related conditions, and other services.11 Healthcare utilization and costs are most intensive at the end of life;12 however, patients enrolled in hospice care have lower Medicare costs than patients who do not enroll, and lower costs are not due to shorter survival time.13

Though hospice utilization has increased over the past two decades,14, 15 many eligible patients are not enrolled, or are enrolled late.16, 17 As a result, at the end of life many cancer patients experience unmanaged symptoms, little psychosocial support, or aggressive care that may be of limited benefit.16–18 The median duration of hospice use, a measure of timing of referral, declined 12% from 1992–1998 for Medicare beneficiaries with cancer,14, 19 and according to recent statistics available from Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), mean duration of use declined 5.0% for pancreatic cancer patients from 1998–2008.20 Patients referred to hospice in a late terminal stage may not receive the full benefit of hospice services.21, 22 Moreover, there is evidence that aggressiveness of end-of-life cancer treatment has increased, including receipt of chemotherapy within 2 weeks of death and emergency room visits, hospitalizations, and intensive care unit (ICU) admissions in the last month of life.23–25

Previous studies have indicated that pancreatic cancer patients are more likely to use hospice compared to other cancer sites;15, 26 however, others have shown great consistency in hospice use and median length of use across cancer diagnoses.27 Previous studies have not examined patterns and predictors of hospice use in pancreatic cancer patients. We used Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) tumor registry and linked Medicare claims data to examine hospice utilization and aggressiveness of care among pancreatic cancer patients at the end of life. Patterns of utilization are described by disease stage, demographic characteristics and health care factors. In addition, trends in hospice utilization and aggressiveness of care were examined over a 14-year period.

METHODS

Data Source

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Texas Medical Branch.

The analysis used data from the National Cancer Institute’s SEER tumor registry and linked Medicare claims data collected by CMS. The SEER program is an epidemiological surveillance system of tumor registries from specific geographic areas currently representing 26% of the U.S. population.28 SEER registries collect data on patient demographics, cancer site, stage, histology, date of diagnosis, first course of therapy, and date of death.

The SEER-Medicare database links Medicare claims data for covered health care services, including inpatient and outpatient care and bills for hospice, to the SEER registry for patients age 65 years and older.29 The SEER-Medicare linkage matches approximately 93% of all SEER patients older than 65 with Medicare enrollment and claims files. The data used in this study include patients diagnosed from 1992 through 2005 and their Medicare claims from 1991 to 2006.

SEER-Medicare data were used to identify a cohort of Medicare beneficiaries based on the following inclusion criteria: 1) patients with International Classification of Disease-O-3 histology codes consistent with adenocarcinoma (neuroendocrine and acinar cell cancers excluded) and pancreatic cancer as first primary cancer, 2) patients diagnosed between 1992 and 2005, who died between 1992 and 2006, 3) patients aged 66 or older at date of diagnosis, and 4) patients enrolled in Medicare Part A and B without HMO for 12 months before and three months after diagnosis. Patients diagnosed at autopsy or death were excluded. The final cohort included 22,818 decedents.

Outcomes of Interest

Hospice use was assessed for each patient from date of diagnosis to date of death. Patients who enrolled in hospice at any point during this period were designated as hospice users, regardless of length of stay. Among hospice users, enrollment in hospice at least 4 weeks before death was also included as an indicator of early enrollment. One month was chosen as the time point for early enrollment in an attempt to capture appropriate hospice utilization. The median length of stay in hospice is approximately 30 days, though length of stay has declined over time.17, 21–23 Aggressiveness of care at the end of life was measured with indicator variables for receipt of chemotherapy, acute care hospitalization, and ICU admission in the last month of life.

Covariates

Demographic characteristics included age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, and geographic area of residence (urban, rural). ZIP code-level data from the 2000 U.S. Census were used to group patients into quartiles according to median household income and percent without high school education. Patient comorbidities were assessed in the year prior to date of diagnosis according to Klabunde’s modification of the Charlson comorbidity index.30 Patients were classified as having 0, 1, 2, or ≥ 3 comorbidities.

SEER does not provide American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage for pancreatic cancer. SEER historic stage was used to classify stage as localized (AJCC: 0, IA, IB), regional (AJCC: IIA, IIB, and III), and distant (AJCC: IV). SEER changed the coding and abstracting rules for the Collaborative Staging system in 2004 to include all information obtained during the period of diagnosis and work-up. As the new system may lead to more accurate staging or staging migration, localized and regional disease were analyzed together as locoregional stage. Other disease characteristics included tumor location and resectability based on SEER extent of disease codes. Patients with extension into major vascular structures (superior mesenteric vein, portal vein, celiac axis, superior mesenteric artery) were considered unresectable. Extension into any organ within the field of resection (duodenum, distal bile duct) and regional lymph nodes were considered resectable. In patients with locoregional stage disease, outcomes were analyzed by resectability status, as clinical management and end-of-life care are likely to differ between these two groups.

Patients with ICD-9 procedure codes for total pancreatectomy, pancreatico-duodenectomy, distal pancreatectomy, or other pancreatic resection (52.6, 52.7, 52.51, 52.52, 52.53, 52.59) in inpatient Medicare claims files were classified as having undergone curative pancreatic resection. Physician visits were documented in the 6 months prior to death and categorized as dichotomous variables (“visited physician vs. “did not visit physician”). Physician specialty was identified using Medicare specialty claims and categorized as primary care physician (PCP, general practice, family practice, internal medicine, geriatrics), general surgeon (including surgical oncologists), medical or radiation oncologist, and gastroenterologist. Physician visit variables were not mutually exclusive. For example, patients who visited an oncologist were compared to patients who did not visit an oncologist (but who may have visited other specialists) during the 6 months before death.

Statistical Analyses

Summary statistics were calculated for all covariates. Chi-square analyses were used to compare hospice use and early enrollment in hospice by sample characteristics. Among patients with locoregional disease, hospice use and indicators of aggressive care were compared by surgical resection status using chi-square analyses. Time trends in hospice use, timing of hospice, and aggressiveness of care indicators were evaluated using Cochran-Armitage tests for trend. Trend analyses were repeated, restricting to the SEER 11 sites that were constant over the time period, and results were equivalent. Logistic regression was used to assess independent predictors of hospice use. Covariates were removed from the model in backward sequential fashion based on AIC criteria, deviance per degree of freedom, and P<0.10. Age was forced into the model for patients with locoregional disease. Analyses were performed using SAS statistical software version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Statistical significance was defined as a two-sided P value of <0.05.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics and Hospice Use and Early Enrollment

Table 1 shows sample characteristics, hospice use, and early enrollment in hospice for the entire cohort of 22,818 patients. The majority of patients presented with distant disease (61.9%) and tumors in the head of the pancreas (51.9%). Most patients were female (56.3%), white (80.1%), lived in an urban area (85.6%), and had zero comorbidities (56.3%) in the year prior to diagnosis. The majority of patients had visited a PCP in the six months before death (86.4%), 59.1% had visited an oncologist, 41.8% had visited a surgeon, and 52.2% had visited a gastroenterologist.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics, Hospice Use, and Early Enrollment in Hospice (N = 22,818)

| Overall Cohort | % | % Hospice Use | P | % Early Enroll* | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Locoregional stage | |||||

| Resectable | 6,865 (30.09) | 56.53 | <0.0001 | 44.63 | <0.0001 |

| Unresectable | 1,817 (7.96) | 64.56 | 45.27 | ||

| Distant stage | 14,136 (61.95) | 56.17 | 30.26 | ||

| Age < 70 years | 16.13 | 54.19 | 0.0001 | 35.27 | 0.780 |

| 70–74 years | 24.45 | 56.29 | 35.42 | ||

| 74–79 years | 25.20 | 56.96 | 36.39 | ||

| 80–84 years | 18.90 | 59.17 | 36.74 | ||

| >85 years | 15.32 | 58.06 | 35.99 | ||

| Female | 56.30 | 59.50 | <0.0001 | 39.32 | <0.0001 |

| Male | 43.70 | 53.62 | 31.24 | ||

| White | 80.07 | 58.87 | <0.0001 | 36.28 | 0.0307 |

| Black | 9.81 | 49.73 | 33.33 | ||

| Hispanic | 5.12 | 52.72 | 38.81 | ||

| Other | 5.00 | 44.35 | 32.35 | ||

| Married | 50.47 | 56.88 | 0.8778 | 33.88 | <0.0001 |

| Not married | 49.53 | 56.98 | 38.14 | ||

| Urban residence | 85.86 | 57.21 | 0.0409 | 34.93 | <0.0001 |

| Rural residence | 14.14 | 55.29 | 42.66 | ||

| Income quartile | |||||

| Q1 | 27.43 | 55.08 | 0.0091 | 38.60 | <0.0001 |

| Q2 | 25.86 | 57.56 | 36.97 | ||

| Q3 | 23.39 | 57.41 | 35.66 | ||

| Q4 | 23.31 | 57.84 | 32.24 | ||

| Education quartile | |||||

| Q1 | 29.13 | 53.46 | <0.0001 | 35.47 | 0.7850 |

| Q2 | 23.60 | 57.43 | 36.33 | ||

| Q3 | 24.24 | 57.33 | 36.52 | ||

| Q4 | 23.03 | 60.26 | 35.65 | ||

| Comorbidity | |||||

| 0 | 56.33 | 57.71 | <0.0001 | 36.72 | 0.0069 |

| 1 | 25.54 | 57.81 | 36.04 | ||

| 2 | 10.67 | 54.12 | 35.17 | ||

| ≥ 3 | 7.46 | 52.07 | 30.91 | ||

| Tumor location | |||||

| Head | 51.94 | 56.18 | 0.0014 | 38.87 | <0.0001 |

| Body/tail | 19.55 | 59.30 | 34.36 | ||

| Not specified | 28.51 | 56.68 | 31.97 | ||

| Cause of death | |||||

| Pancreatic cancer | 86.37 | 59.57 | <0.0001 | 36.56 | <0.0001 |

| Other | 13.63 | 40.22 | 30.69 | ||

| Visit oncologist, 6 mo. | 59.11 | 60.40 | <0.0001 | 33.42 | <0.0001 |

| No visit | 40.89 | 51.93 | 40.31 | ||

| Visit surgeon, 6 mo. | 41.78 | 52.75 | <0.0001 | 31.41 | <0.0001 |

| No visit | 58.22 | 59.93 | 38.88 | ||

| Visit PCP, 6 mo. | 86.44 | 56.30 | <0.0001 | 33.85 | <0.0001 |

| No visit | 13.56 | 60.97 | 48.61 | ||

| Visit GI, 6 mo. | 52.15 | 55.06 | <0.0001 | 31.17 | <0.0001 |

| No visit | 47.85 | 58.97 | 40.90 | ||

Among hospice users, enrollment in hospice ≥4 weeks prior to death

PCP, primary care physician; GI, gastroenterologist

Hospice Use and Early Enrollment

Overall, 12,994 patients (56.9%) used hospice prior to death, 4,666 (35.9%) of whom enrolled at least 4 weeks prior to death. Hospice use was higher in patients with unresectable locoregional disease (64.6%) compared to patients with resectable locoregional (56.5%) or distant stage disease (56.2%) (P< 0.0001). Patients with tumors in the body or tail of the pancreas were more likely to use hospice. Hospice use was higher among older patients, females, and whites, and among patients living in urban and higher socioeconomic areas. Sixty percent of patients who visited an oncologist in the 6 months before death enrolled in hospice, compared to 51.9% of patients who had not visited an oncologist (P< 0.0001). In contrast, patients who had visited a surgeon, PCP, or gastroenterologist in the last 6 months of life were less likely to enroll in hospice compared to patients who had not seen a surgeon, PCP, or gastroenterologist, respectively (P<0.0001 for all).

Early enrollment in hospice was more common among females, Hispanics and whites, unmarried patients, and patients living in rural areas. Patients presenting with locoregional disease, resectable (44.6%) or unresectable (45.3%), also were more likely to enroll in hospice at least 4 weeks before death, compared to patients presenting with distant disease (30.3%, P<0.0001). Patients who had visited an oncologist, surgeon, PCP, or gastroenterologist in the 6 months prior to death were less likely to have early enrollment compared to, respectively, patients who had not visited an oncologist, surgeon, PCP, or gastroenterologist.

Multivariate Predictors of Hospice Care by Disease Stage

Multivariate logistic regression was used to identify independent predictors of hospice care by disease stage (Table 2). Patterns were similar for each stage. Older patients and females were more likely to use hospice. Racial/ethnic minorities and patients in rural areas were less likely to use hospice care. Hospice use increased approximately 11–13% per year over the study period. Hospice use was greater among patients who died of pancreatic cancer compared to those who died of other causes.

Table 2.

Multivariate Logistic Regression Predicting Odds of Hospice Use by Disease Stage

| Distant stage (N= 14,136) | Locoregional stage (N= 8,682) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI |

| Surgical resection | NA | 0.71 | 0.63, 0.80 | |

| Resectability | NA | 0.88 | 0.79, 0.99 | |

| Age 70–74 (ref. < 70) | 1.14 | 1.02, 1.28 | 1.05 | 0.91, 1.23 |

| Age 75–79 (ref. < 70) | 1.18 | 1.05, 1.32 | 1.03 | 0.88, 1.20 |

| Age 80–84 (ref. < 70) | 1.34 | 1.18, 1.52 | 1.12 | 0.95, 1.32 |

| Age ≥85 (ref. < 70) | 1.22 | 1.06, 1.40 | 1.05 | 0.88, 1.25 |

| Female | 1.28 | 1.19, 1.38 | 1.28 | 1.16, 1.40 |

| Black (ref. white) | 0.69 | 0.60, 0.79 | 0.72 | 0.61, 0.86 |

| Hispanic (ref. white) | 0.85 | 0.71, 1.02 | 0.91 | 0.73, 1.13 |

| Other (ref. white) | 0.64 | 0.52, 0.79 | 0.49 | 0.39, 0.62 |

| Rural area (ref. urban) | 0.66 | 0.58, 0.75 | 0.66 | 0.56, 0.78 |

| Income quartile 1 (ref 4) | 0.89 | 0.78, 1.01 | 0.76 | 0.65, 0.89 |

| Income quartile 2 (ref 4) | 0.93 | 0.83, 1.04 | 0.83 | 0.72, 0.96 |

| Income quartile 3 (ref 4) | 1.03 | 0.93, 1.16 | 0.86 | 0.75, 0.99 |

| Charlson 1 (ref. 0) | 1.02 | 0.93, 1.11 | 0.95 | 0.85, 1.06 |

| Charlson 2 (ref. 0) | 0.85 | 0.75, 0.97 | 0.90 | 0.77, 1.05 |

| Charlson ≥3 (ref. 0) | 0.85 | 0.73, 0.98 | 0.83 | 0.70, 1.00 |

| Year of death | 1.13 | 1.11, 1.14 | 1.11 | 1.10, 1.13 |

| Cause of death – pancreatic cancer | 1.94 | 1.74, 2.15 | 2.60 | 2.25, 3.00 |

| Visit oncologist | 1.18 | 1.08, 1.28 | 1.25 | 1.13, 1.38 |

| Visit surgeon | 0.84 | 0.78, 0.91 | 0.65 | 0.59, 0.72 |

| Visit PCP | 0.83 | 0.74, 0.93 | 0.86 | 0.75, 0.98 |

| Visit gastroenterologist | 0.88 | 0.82, 0.95 | 0.81 | 0.74, 0.90 |

Note: Models adjusted for SEER region

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; Ref, reference category; PCP, primary care physician

Among those with distant stage disease, patients who had visited an oncologist within the 6 months before death were 18% more likely to enroll in hospice (OR= 1.18, 95% CI 1.08, 1.28); however, patients who had visited other specialists were less likely to enroll. Patients with locoregional disease who underwent surgical resection were 29% less likely to enroll in hospice before death (OR = 0.71, 95% CI 0.63, 0.80).

Patients with resectable tumors had lower odds of hospice use (OR = 0.88, 95% CI 0.79, 0.99). Lower income was associated with reduced odds of hospice enrollment in this group. Patients who saw an oncologist in the last 6 months of life were 25% more likely to enroll in hospice (OR= 1.25, 95% CI 1.13, 1.38), while those who saw a surgeon were 35% less likely to enroll (OR= 0.65, 95% CI 0.59, 0.72).

Time Trends in Hospice Use and Aggressiveness of Care

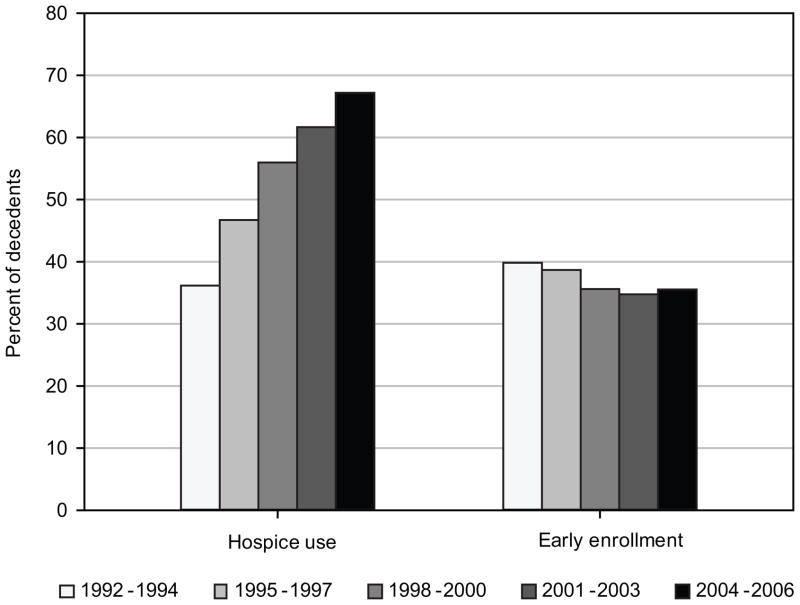

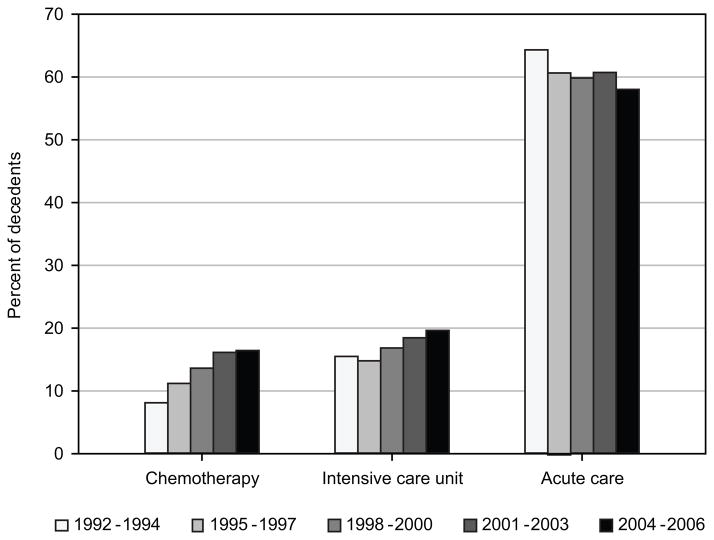

Time trends in hospice use and indicators of aggressiveness of care were estimated in 3-year intervals (Figure 1). Hospice use increased among decedents over time, from 36.2% in patients who died in 1992–1994 to 67.2% in patients who died in 2004–2006 (P<0.0001). Among hospice users, early enrollment in hospice declined from 39.8% in 1992–1994 to 35.5% in 2004–2006 (P= 0.002). On the other hand, among all decedents (including hospice users and nonusers in the denominator) early enrollment in hospice increased from 14.4% to 23.9% (not shown). Aggressiveness of care increased over time for two of the three selected indicators (Figure 2). In 1992–1994, 8.1% of patients received chemotherapy during the last month of life, compared to 16.5% of patients who died in 2004–2006 (P<0.0001). Admission to the ICU in the last month of life increased from 15.5% of patients in 1992–1994 to 19.6% in 2004–2006 (P<0.0001). However, admissions to acute care hospitals in the last month of life decreased 6 percentage points over the time period (P<0.0001).

Figure 1.

Time trends in hospice use and early enrollment in hospice (≥4 weeks prior to death) among pancreatic cancer decedents, 1992–2006

Figure 2.

Time trends in receipt of chemotherapy and admission to an intensive care unit or acute care hospital within the last month of life among pancreatic cancer decedents, 1992–2006

Aggressiveness of Care by Stage and Resection Status

Patients presenting with distant (15.8%) or unresectable locoregional pancreatic cancer (15.7%) were more likely to receive chemotherapy within the last month of life compared to patients with resectable locoregional disease (10.3%, P<0.0001) (Table 3). However, patients with unresectable locoregional stage disease were less likely to have an ICU admission (14.8%) within the last month of life compared to those with distant (17.7%) or resectable locoregional stage disease (18.2%) (P=0.003). Finally, patients with distant disease were more likely to have an inpatient admission within the last month of life (64.1%) compared to patients with resectable (54.9%) or unresectable (51.8%) locoregional stage disease (P<0.0001). For the overall cohort, 48% (6,341/12,994) of patients who enrolled in hospice received aggressive care (hospital admission, ICU use, or chemotherapy) in the last month of life prior to hospice enrollment.

Table 3.

Hospice Use and Aggressiveness of Care Among Patients by Disease Stage and Surgical Resection Status

| Overall cohort | Distant N= 14,136 | Resectable Locoregional | Unresectable Locoregional | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N= 6,865 | N= 1,817 | |||

| Hospice use | 56.17 | 56.53 | 64.56 | <0.0001 |

| Early enrollment (≥ 4 wks.)* | 30.26 | 44.63 | 45.27 | <0.0001 |

| Chemotherapy at end of life | 15.80 | 10.25 | 15.74 | <0.0001 |

| ICU at end of life | 17.71 | 18.19 | 14.80 | 0.003 |

| Inpatient at end of life | 64.13 | 54.93 | 51.84 | <0.0001 |

| Locoregional cancer patients | Resected N= 1,911 | Unresected N= 6,771 | P | |

| Resectable | N= 1,722 | N= 5,143 | ||

| Hospice use | 53.43 | 57.57 | 0.003 | |

| Early enrollment ( ≥ 4 wks.)** | 38.37 | 46.57 | 0.0001 | |

| Chemotherapy at end of life | 14.34 | 8.89 | <0.0001 | |

| ICU at end of life | 26.89 | 15.28 | <0.0001 | |

| Inpatient at end of life | 61.03 | 52.89 | <0.0001 | |

| Unresectable | N= 189 | N= 1,628 | ||

| Hospice use | 51.85 | 66.03 | 0.0001 | |

| Early enrollment (≥ 4 wks.)*** | 36.73 | 46.05 | 0.076 | |

| Chemotherapy at end of life | 23.28 | 14.86 | 0.003 | |

| ICU at end of life | 13.94 | 22.22 | 0.002 | |

| Inpatient at end of life | 60.85 | 50.80 | 0.009 |

Among hospice users, N = 7,940 for distant stage, N = 3,881 for resectable locoregional, N = 1,173 for unresectable locoregional

Among hospice users, N = 920 for resected, N = 2,961 for unresected

Among hospice users, N = 98 for resected, N = 1,075 for unresected ICU, intensive care unit

Among patients with resectable locoregional stage disease, those who underwent surgical resection were less likely to use hospice (53.4% vs. 57.6%, P=0.003) and to enroll in hospice for at least four weeks (38.4% vs. 46.6%, P<0.0001) (Table 3). Resected patients were more likely to receive chemotherapy (14.3% vs. 8.9%, P<0.0001) and be admitted to an acute care hospital (61.0% vs. 52.9%, P<0.0001) or ICU (26.9% vs. 15.3%, P<0.0001) in the last month of life.

DISCUSSION

We examined patterns of hospice utilization and aggressiveness of care among Medicare beneficiaries dying with pancreatic cancer from 1992–2006. Hospice services are covered by Medicare and provide comprehensive end-of-life care. However, 43% of decedents in this sample did not use hospice services and only a little over one-third of hospice users enrolled at least four weeks before death. While hospice use nearly doubled over the time period studied, we observed a simultaneous increase in the use of aggressive care at the end of life in both hospice and non-hospice users, with increasing rates of chemotherapy and ICU admissions in the last month of life. Our data imply that hospice is not being used optimally to provide end-of-life care for patients with pancreatic cancer.

Our study is the first to evaluate hospice use in conjunction with aggressiveness of care or to evaluate end-of-life care by tumor stage, resectability, or resection status for patients with pancreatic cancer. Our findings suggest that patients with resected locoregional disease are less likely to use hospice and more likely to receive aggressive care in the last month of life than those who are not resected. While decreased hospice use may imply better quality of life and symptom control, the increased use of chemotherapy and ICU care at the end of life suggest that treating physicians and/or resected patients are unable to make the transition to palliative care when curative-intent surgery fails. Awareness of this pattern and education on the benefits of hospice may help patients and physicians make the transition from curative to palliative care at the appropriate time, improving quality of life and reducing costs for futile aggressive care.

Patients with distant disease were more likely to receive chemotherapy in the last month of life and less likely to enroll early in hospice compared to those with resectable locoregional disease. The median survival of patients presenting with resectable locoregional disease was 6.0 months compared to 2.0 months for those presenting with distant disease. A large proportion of patients with distant disease have very little time to adjust to their illness and prognosis. Thus, the higher use of chemotherapy at the end of life and lower rates of early enrollment in hospice are likely a function of shorter survival times in this group.

In selecting the time point for early enrollment in this study, we wanted to capture appropriate hospice utilization, rather than poor quality care. In a national survey, internal medicine physicians recommended patients use hospice for 3 months prior to death.31 Given the poor survival of patients with pancreatic cancer, we selected 1 month as the length of stay indicating timely care. A survey of family members of decedents has shown that in cases where family members believed that hospice referral was made at the “right time,” the median length of stay in hospice was 31 days.32

Hospice experts have identified barriers to hospice enrollment and timely referral.33 Physicians’ difficulty with discussing death and their desire to continue curative-intent therapy into the last stages of disease contribute to late hospice referrals.33 Patients may prefer to receive potential life-prolonging therapy or aggressive care, despite toxicity or impaired quality of life. Many physicians lack training and experience in end-of-life care as well as knowledge about the benefits of hospice.33 Prognostic accuracy at the end of life is difficult and is likely to influence the timing of hospice referral. In addition, some physicians may delay discussions regarding hospice in the face of this uncertainty, not wanting their patients to lose hope. Cancer patients referred to hospice by physicians who accurately estimate survival are more likely to spend the recommended 3 months in hospice compared with patients whose physicians made inaccurate survival estimates.34

Previous reports have established patient and area-level characteristics associated with hospice enrollment.17, 35, 36 Our results showed that hospice use was lower in patients who were younger, male, black or Hispanic, or living in a rural or lower socioeconomic area. Cost concerns and patient preferences or cultural beliefs of family provision of care may contribute to underutilization of hospice services among low income and black and Hispanic populations.37 Additionally, many Medicare patients living in rural areas lack access to Medicare-certified home-based hospice services.38 We also found that patients with more comorbidities were less likely to use hospice and to enroll early. These patients had lower median survival and were more likely to die of a cause other than pancreatic cancer (19.9% in those with ≥3 comorbidities vs. 12.5% in those with none).

Patients with more comorbidities may have died before they could be enrolled in hospice, and died more quickly after enrollment (due to other conditions), contributing to lower hospice utilization and early enrollment. Patients’ interactions with the health care system, including physicians seen and inpatient and outpatient care, influence hospice enrollment.39 Hospice use is higher among patients seeing a cancer specialist.17, 39 However, patients referred by generalists lived longer in hospice than patients referred by oncologists,34 and patients cared for by an oncologist in the last month of life were more likely to enroll in hospice within 3 days of death.24 While we did not specifically evaluate the specialty of the referring physician, we found that patients who visited an oncologist in the last six months of life were more likely to use hospice services.

Some of the increase in hospice utilization during our study period may be attributable to the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, which changed reimbursement systems for home health and hospice services, resulting in an increase in hospice services and a decrease in home health.40 These reimbursement changes restricted eligibility requirements for home health services while relaxing those for hospice care. In addition, home health services were transitioned from fee-for-service to a prospective payment system. Nevertheless, steady increases in hospice utilization were observed over the entire study period with no significant incremental increase in 1998. Widespread efforts to educate health professionals regarding appropriate end-of-life care may have contributed to increasing trends in hospice utilization over the time period of this study.41 Increased acceptance of hospice and palliative care and the development of guidelines for hospice care also likely contributed to increased use of hospice services.41

Despite increased hospice use over time for a variety of cancers, increasing trends in the aggressiveness of treatment at the end of life for cancer patients have also been noted.24 Our findings were similar, with a doubling in the percentage of patients receiving chemotherapy in the last month of life and an increase in the percentage of patients admitted to the ICU in the last month of life. Increases in aggressive care at the end of life result in increased costs, with little survival benefit, and may impede timely referral to hospice. We found an 11% relative decrease in early enrollment among hospice users with pancreatic cancer between 1992 and 2006. Together, these findings imply that oncologists and other care providers are likely to refer to hospice much later in the process and only after aggressive and costly treatment. In fact, 48% of hospice patients in our study received some form of aggressive care in the last month of life prior to enrollment in hospice. Thus, a significant group of patients receive chemotherapy or are admitted to the ICU or acute care hospital in the last month of life before being referred to hospice to die. Earle and colleagues have concluded that hospice care is increasingly being used to manage death rather than provide end-of-life care, with patients being admitted within days or a few weeks of death.23

This study has several limitations. We identified decedents using SEER-Medicare data and assessed hospice use and care in the months before death. Some have criticized this study design as biased;42 however, the retrospective approach allows for identification of a cohort of patients, and allows all patients who die to be studied at the end of life.43 Nevertheless, in retrospective studies it is not possible to determine if and when physicians may have perceived patients’ terminal status. Some patients may not have been recognized as terminally ill before death, as prognostication at the end of life can be extremely difficult. We did not have information on patient/family preferences for enrollment in hospice or information regarding physician attitudes. In a population-based study we cannot determine appropriateness of care at the individual level. However, we can evaluate trends in the population, such as the increases in aggressive care in the last month of life. Over the time period of study, there has been no significant progress in the treatment of advanced stage pancreatic cancer that would explain a doubling in the use of chemotherapy at the end of life. We were unable to determine if chemotherapy was being used palliatively to alleviate tumor-related symptoms or as curative-intent treatment. However, pancreatic cancer is relatively chemoinsensitive (≤30% response rate to palliative chemotherapy),44 and use of chemotherapy in the last weeks of life has been described as potentially poor clinical judgment.44 Physician visits in the months prior to death may be an indication of whether the patient was known to have active disease; therefore, differences in hospice use between physician specialties may not reflect true differences in practice styles. Our study included Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries diagnosed with pancreatic cancer residing in SEER areas in the U.S.; results may not be generalizable to all patients with pancreatic cancer.

Pancreatic cancer is an aggressive cancer with 5-year survival of less than 4% and little effective therapy in the setting of advanced stage disease. While hospice use is increasing over time, 43% of patients dying with pancreatic cancer do not use these services. Moreover, increases in the use of aggressive care at the end of life and low early enrollment in hospice suggest that hospice is not being used optimally. Nearly half of those who use hospice do so only after receiving aggressive therapy in the last month of life. Additionally, patients who underwent surgical resection were more likely to receive aggressive care and less likely to enroll in hospice at the end of life. Hospice benefits include prolonged life, increased quality of life, and lower health care costs, and physicians play a crucial role in guiding the transition from curative to palliative goals of treatment for patients with pancreatic cancer.

Acknowledgments

Support: Jahnigen Career Development Scholars Award, NIH K07 Cancer Prevention, Control, and Population Sciences Career Development Award (1K07CA13098-01A1), and Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas (RP101207)

Footnotes

Disclosures: None

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA: a Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2010;60(5):277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riall TS, Nealon WH, Goodwin JS, et al. Pancreatic cancer in the general population: Improvements in survival over the last decade. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 2006;10(9):1212–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jemal A, Clegg LX, Ward E, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2001, with a special feature regarding survival. Cancer. 2004;101(1):3–27. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Labori KJ, Hjermstad MJ, Wester T, Buanes T, Loge JH. Symptom profiles and palliative care in advanced pancreatic cancer: a prospective study. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2006;14(11):1126–1133. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0067-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nieveen van Dijkum EJ, Kuhlmann KF, Terwee CB, Obertop H, de Haes JC, Gouma DJ. Quality of life after curative or palliative surgical treatment of pancreatic and periampullary carcinoma. British Journal of Surgery. 2005;92(4):471–477. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greer DS, Mor V. An overview of National Hospice Study findings. Journal of Chronic Diseases. 1986;39(1):5–7. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(86)90102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greer DS, Mor V, Morris JN, Sherwood S, Kidder D, Birnbaum H. An alternative in terminal care: results of the National Hospice Study. Journal of Chronic Diseases. 1986;39(1):9–26. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(86)90103-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wallston KA, Burger C, Smith RA, Baugher RJ. Comparing the quality of death for hospice and non-hospice cancer patients. Medical Care. 1988;26(2):177–182. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198802000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Connor SR, Pyenson B, Fitch K, Spence C, Iwasaki K. Comparing hospice and nonhospice patient survival among patients who die within a three-year window. Journal of Pain & Symptom Management. 2007;33(3):238–246. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363(8):733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Hospice Benefits. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riley GF, Lubitz JD. Long-term trends in Medicare payments in the last year of life. Health Services Research. 2010;45(2):565–576. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01082.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pyenson B, Connor S, Fitch K, Kinzbrunner B. Medicare cost in matched hospice and non-hospice cohorts. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2004;28(3):200–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.U.S. General Accounting Office. Medicare: More Beneficiaries Use Hospice But for Fewer Days. Washington, DC: U.S. General Accounting Office; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCarthy EP, Burns RB, Ngo-Metzger Q, Davis RB, Phillips RS. Hospice use among Medicare managed care and fee-for-service patients dying with cancer. JAMA. 2003;289(17):2238–2245. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.17.2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Field MJ, Cassel CK. Approaching death : Improving care at the end of life. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press; 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keating NL, Herrinton LJ, Zaslavsky AM, Liu L, Ayanian JZ. Variations in hospice use among cancer patients. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2006;98(15):1053–1059. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foley KM, Gelband H. Improving palliative care for cancer. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to Congress: Medicare Beneficiaries' Access to Hospice. Washington, DC: MedPAC; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hospice Overview. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; [Accessed October 15, 2010]. Available from: http://www.cms.gov/Hospice/ [Google Scholar]

- 21.Christakis NA. Timing of Referral of Terminally Ill Patients to an Outpatient Hospice. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1994;9(6):314–320. doi: 10.1007/BF02599178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Christakis NA, Escarce JJ. Survival of Medicare patients after enrollment in hospice programs. New England Journal of Medicine. 1996;335(3):172–178. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199607183350306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Earle CC, Neville BA, Landrum MB, Ayanian JZ, Block SD, Weeks JC. Trends in the aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2004;22(2):315–321. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Earle CC, Landrum MB, Souza JM, Neville BA, Weeks JC, Ayanian JZ. Aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life: Is it a quality-of-care issue? Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26(23):3860–3866. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.8253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharma G, Freeman J, Zhang D, Goodwin JS. Trends in end-of-life ICU use among older adults with advanced lung cancer. Chest. 2008;133(1):72–78. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iwashyna TJ, Zhang JX, Christakis NA. Disease-specific patterns of hospice and related healthcare use in an incidence cohort of seriously ill elderly patients. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2002;5(4):531–538. doi: 10.1089/109662102760269760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Virnig BA, Marshall McBean A, Kind S, Dholakia R. Hospice use before death: variability across cancer diagnoses. Medical Care. 2002;40(1):73–78. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200201000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results. National Cancer Institute; [Accessed October 5, 2010]. Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Health Services and Economics. SEER-Medicare: A Brief Description of the SEER-Medicare Database. National Cancer Institute; [Accessed October 5, 2010]. Available from: http://healthservices.cancer.gov/seermedicare/overview. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baldwin LM, Klabunde CN, Green P, Barlow W, Wright G. In search of the perfect comorbidity measure for use with administrative claims data: does it exist? Medical Care. 2006;44(8):745–753. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000223475.70440.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iwashyna TJ, Christakis NA. Attitude and self-reported practice regarding hospice referral in a national sample of internists. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 1998;1(3):8. doi: 10.1089/jpm.1998.1.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schockett ER, Teno JM, Miller SC, Stuart B. Late referral to hospice and bereaved family member perception of quality of end-of-life care. Journal of Pain & Symptom Management. 2005;30(5):400–407. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Friedman BT, Harwood MK, Shields M. Barriers and enablers to hospice referrals: an expert overview. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2002;5(1):73–84. doi: 10.1089/10966210252785033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lamont EB, Christakis NA. Physician factors in the timing of cancer patient referral to hospice palliative care. Cancer. 2002;94(10):2733–2737. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Virnig BA, Kind S, McBean M, Fisher E. Geographic variation in hospice use prior to death. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2000;48(9):1117–1125. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb04789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lackan NA, Ostir GV, Freeman JL, Mahnken JD, Goodwin JS. Decreasing variation in the use of hospice among older adults with breast, colorectal, lung, and prostate cancer. Medical Care. 2004;42(2):116–122. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000108765.86294.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Born W, Greiner KA, Sylvia E, Butler J, Ahluwalia JS. Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about end-of-life care among inner-city African Americans and Latinos. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2004;7(2):247–256. doi: 10.1089/109662104773709369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Virnig BA, Ma H, Hartman LK, Moscovice I, Carlin B. Access to home-based hospice care for rural populations: Identification of areas lacking service. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2006;9(6):1292–1299. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keating NL, Landrum MB, Guadagnoli E, Winer EP, Ayanian JZ. Care in the months before death and hospice enrollment among older women with advanced breast cancer. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2008;23(1):11–18. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0422-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.U.S. Health Care Financing Administration. Health Care Financing Review: Medicare and Medicaid Statistical Supplement. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kilgore ML, Grabowski DC, Morrisey MA, Ritchie CS, Yun H, Locher JL. The effects of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 on home health and hospice in older adult cancer patients. Medical Care. 2009;47(3):279–285. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181893c77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bach PB, Schrag D, Begg CB. Resurrecting treatment histories of dead patients: a study design that should be laid to rest. JAMA. 2004;292(22):2765–2770. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.22.2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Earle CC, Ayanian JZ. Looking back from death: the value of retrospective studies of end-of-life care. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(6):838–840. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.9388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kao S, Shafiq J, Vardy J, Adams D. Use of chemotherapy at end of life in oncology patients. Annals of Oncology. 2009;20(9):1555–1559. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]