Abstract

The CCAAT box transcription factor (CBTF) is a multimeric transcription factor that activates expression of the haematopoietic regulatory factor, GATA-2. The 122 kDa subunit of this complex, CBTF122, is cytoplasmic in fertilized Xenopus eggs and subsequently translocates to the nucleus prior to activation of zygotic GATA-2 transcription at gastrulation. Here we present data suggesting both a role for CBTF122 prior to its nuclear translocation and the mechanism that retains it in the cytoplasm before the midblastula transition (MBT). CBTF122 and its variant CBTF98 are associated with translationally quiescent mRNP complexes. We show that CBTF122 RNA binding activity is both necessary and sufficient for its cytoplasmic retention during early development. The introduction of an additional nuclear localization signal to CBTF122 is insufficient to overcome this retention, suggesting that RNA binding acts as a cytoplasmic anchor for CBTF122. Destruction of endogenous RNA by microinjection of RNase promotes premature nuclear translocation of CBTF122. Thus, the nuclear translocation of CBTF122 at the MBT is likely to be coupled to the degradation of maternal mRNA that occurs at that stage.

Keywords: CCAAT factor/GATA-2/nuclear translocation/ribonucleoprotein/Xenopus

Introduction

Control of early development is dependent upon stringent regulation of gene activity. At the time of zygotic gene activation (ZGA), transcription is under the control of maternally inherited factors. In order to prevent aberrant expression of genes normally transcribed at, or soon after ZGA, the activity of these maternal transcription factors must be tightly regulated. The control of GATA-2 gene expression by the maternally inherited multisubunit CCAAT box transcription factor (CBTF) exemplifies such regulation.

GATA-2 expression is necessary for both haematopoietic and urogenital development in mice (Tsai et al., 1994; Tsai and Orkin, 1997; Zhou et al., 1998) and is implicated in the formation of ventral mesoderm in Xenopus (Sykes et al., 1998). The CBTF binding site in the GATA-2 promoter is evolutionarily conserved and is necessary for the correct regulation of GATA-2 transcription in amphibian embryos and in avian and murine haematopoietic cells (Brewer et al., 1995; Fleenor et al., 1996; Minegishi et al., 1998; Nony et al., 1998). Xenopus CBTF activity is controlled, at least in part, by its subcellular localization (Brewer et al., 1995; Orford et al., 1998). CBTF activity is present in the oocyte nucleus where GATA-2 is initially transcribed (Zon et al., 1991; Walmsley et al., 1994; Partington et al., 1997; Orford et al., 1998). However, after fertilization, CBTF activity is cytoplasmic and re-localizes to the nucleus only at the gastrula stage when zygotic GATA-2 transcription commences (Brewer et al., 1995).

Biochemical evidence indicates that CBTF122 is an essential subunit of CBTF (Orford et al., 1998). Moreover, expression of a dominant-negative form of CBTF122 inhibits GATA-2 transcription specifically in animal pole explants (C.Robinson and M.Guille, manuscript in preparation). The subcellular distribution of CBTF122 changes during development: CBTF122 is nuclear in oocytes, becomes cytoplasmic upon germinal vesicle breakdown during meiotic maturation and is then re-imported into the nucleus between stages 8 and 9. Thus, the exclusion of CBTF122 from embryonic nuclei prior to the gastrula stage may provide a crucial regulatory step to govern GATA-2 activation (Orford et al., 1998).

In this paper we show that both CBTF122 and a highly related isoform, CBTF98, are associated with translationally quiescent mRNP complexes and that RNA binding is both necessary and sufficient for the cytoplasmic retention of CBTF122 prior to stage 9. Taken together, these data show that CBTF122 is a bifunctional protein and that its role as an mRNP component negatively regulates its activity as a transcription factor by precluding its nuclear localization. Furthermore, as the artificial destruction of RNA prior to the midblastula transition (MBT) leads to premature nuclear accumulation of CBTF122, we propose that the degradation of maternal mRNA that occurs at this stage promotes the nuclear accumulation of CBTF122.

Results

Isolation and sequence analysis of a CBTF122 cDNA

A partial cDNA corresponding to CBTF122 and a full-length CBTF98 cDNA designated previously as 4F.2/ubp4 and 4F.1/ubp3, respectively, were initially isolated from a Xenopus ovarian expression library in a screen to identify double-stranded (ds) RNA binding proteins (Bass et al., 1994; Wormington et al., 1996). We independently isolated a partial-length cDNA encoding CBTF122 in a similar expression library screen, to identify proteins that bind to translational control elements located within the 5′-untranslated region (5′-UTR) of ribosomal protein mRNAs (Avni and Shama, 1996). Additional screening using this partial-length cDNA as a hybridization probe and for 5′ RACE PCRs resulted in the isolation of a full-length CBTF122 cDNA. The cDNA-derived amino acid sequences for CBTF122 and CBTF98 are shown in Figure 1. The CBTF98 coding region is 99.8% identical to the corresponding coding region in the CBTF122 cDNA. At present, we cannot determine whether two separate genes encode the 4 kb CBTF122 and 3 kb CBTF98 mRNAs (Figure 2A) or if these mRNAs are derived by alternative splicing of a single transcript. The correspondence between these mRNA species and the two cDNA sequences was shown by probing of northern blots using 3′-UTR-specific probes (data not shown). Although the predicted sizes of CBTF122 and CBTF98 are 95 and 74 kDa, respectively, they migrate aberrantly as 122 and 98 kDa polypeptides in SDS–polyacrylamide gels (Figure 2B).

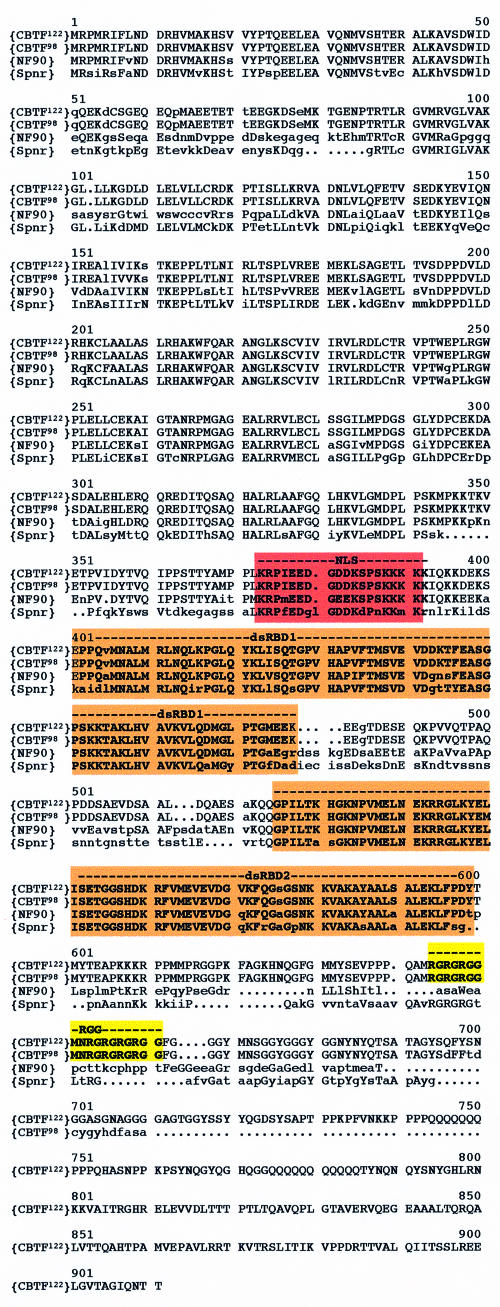

Fig. 1. Amino acid alignment of Xenopus CBTF122 and CBTF98, human NF90 and mouse Spnr proteins. The amino acid sequences shown were aligned using the Pileup program of the GCG software package. NLS, dsRBD1, dsRBD2 and RGG box are boxed in red, orange and yellow, respectively.

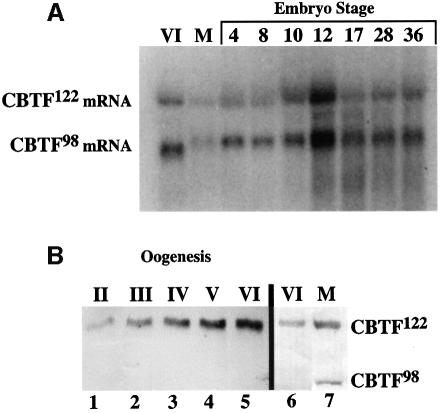

Fig. 2. CBTF122 and CBTF98 mRNA and protein levels during development. (A) Northern blot of total RNA isolated from two oocytes and embryos was probed with 32P-labelled antisense RNA transcribed from the CBTF122 cDNA. The stage of oogenesis (Dumont, 1972) or embryogenesis (Neiuwkoop and Faber, 1967) is indicated at the top of each lane. Lane M shows progesterone-matured oocytes. (B) A western blot of total soluble proteins from five oocytes at the indicated stages (lanes 1–5) was probed with affinity-purified anti-CBTF122/98 antibody. A separate western blot (lanes 6 and 7) of total soluble protein from two stage VI or progesterone-matured oocytes (M) was probed with affinity-purified anti-CBTF122/98 antibody.

Both CBTF122 and CBTF98 have two regions with significant homology to the dsRNA binding domain (dsRBD) initially delineated for Drosophila staufen (Figure 1; St Johnston et al., 1991). An arginine/glycine rich region (RGG box) is present in the C-terminal portions of both CBTF122 and CBTF98 (Figure 1). The RGG box is responsible for the RNA binding activities of proteins such as hnRNP U and nucleolin (for reviews see Dreyfuss et al., 1993; Burd and Dreyfuss, 1994). A bipartite nuclear localization signal (NLS) (Robbins et al., 1991) precedes the first dsRBD, consistent with the nuclear localization of both CBTF122 and CBTF98 (Orford et al., 1998; also see Figures 5 and 7). CBTF122 and CBTF98 share significant sequence homology with the murine RNA binding protein, Spnr (Schumacher et al., 1995), and the putative human transcription factor, NF90 (Corthesy and Kao, 1994; Kao et al., 1994) (Figure 1). Both Spnr and NF90 lack the C-terminal RGG box, but have 76 and 80% sequence similarity and 62 and 69% sequence identity to CBTF122, respectively. The two dsRBDs share higher amino acid identity with the dsRBDs of CBTF122 and CBTF98 (90% for NF90 and 81% for Spnr).

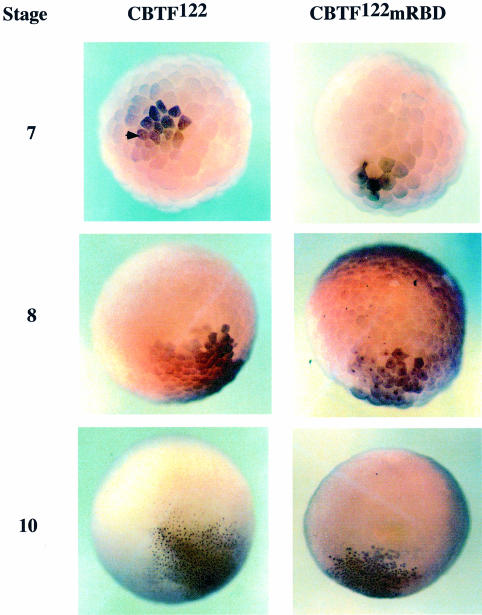

Fig. 5. CBTF122 with mutated dsRBDs is nuclear during early development. Embryos from a single female Xenopus were injected with 200 pg of synthetic RNA encoding myc-tagged CBTF122 or CBTF122mRBD. At the stages shown the embryos were fixed, bleached and immunohistochemistry was performed using an anti-myc-tag antibody. The antibody was visualized by using a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse antibody and DAB staining (brown). The arrow highlights an example of an unstained nucleus.

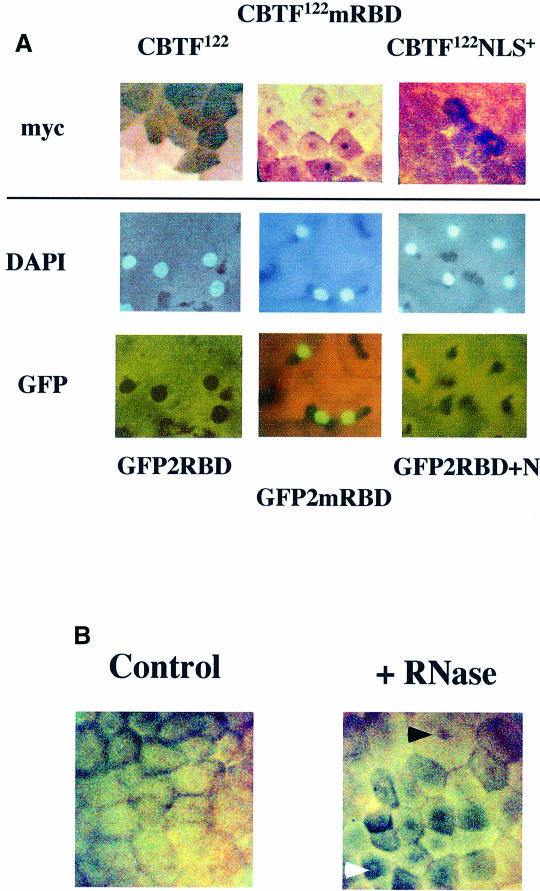

Fig. 7. RNA acts as a cytoplasmic anchor for CBTF122. (A) An additional NLS does not make CBTF122 nuclear during early development. Two-cell embryos from a single female Xenopus were injected with 200 pg of synthetic RNA encoding the proteins shown into the animal pole of each cell and allowed to develop. At stage 8, embryos injected with RNA encoding the full-length myc-tagged proteins were fixed and exogenous protein visualized by immunohistochemistry of the myc tag (top panels). For embryos expressing the GFP constructs, animal pole explants were removed and squashed gently under a coverslip in the presence of DAPI. This released nuclei from the surrounding, intrinsically fluorescent yolk granules. GFP and DAPI staining were then visualized by fluorescence microscopy. (B) Degradation of endogenous RNA leads to nuclear translocation of CBTF122 before the MBT. Embryos from a single female Xenopus were taken at stage 6 and a single blastomere injected with 1 nl of either buffer (control) or buffer containing 50 ng of RNase A (+RNase). After incubation for a further 60 min, cell division was arrested by incubation in cycloheximide. Embryos were fixed, endogenous CBTF122/98 was visualized by immunohistochemistry and the embryos cleared. The cell receiving the RNase injection is markedly larger than those around it and shows nuclear staining (black arrow), as do some surrounding cells that also received RNase. The white arrow shows perinuclear staining, which has been observed previously at these early stages. Only limited perinuclear staining is observed in controls.

CBTF122 and CBTF98 are present throughout early development

Northern analysis shows that both CBTF122 and CBTF98 mRNAs are present at similar levels through development of the swimming tadpole stage (Figure 2A). This is in agreement with the gradual accumulation of both proteins throughout embryogenesis reported previously by Bass et al. (1994). The increased size of maternal CBTF98 mRNA after oocyte maturation is due to its cytoplasmic polyadenylation and coincides with its recruitment onto polysomes (Figure 2A; Wormington et al., 1996). Steady-state levels of CBTF122 and CBTF98 during oocyte development were determined by immunoblot analysis of proteins extracted from staged oocytes (Figure 2B). A polyclonal antibody generated against bacterially expressed CBTF122 recognizes both CBTF122 and CBTF98 isoforms. CBTF122 accumulates throughout oogenesis. In contrast, CBTF98 is not detected before progesterone-induced maturation, consistent with the translational unmasking of its cognate mRNA (Wormington et al., 1996).

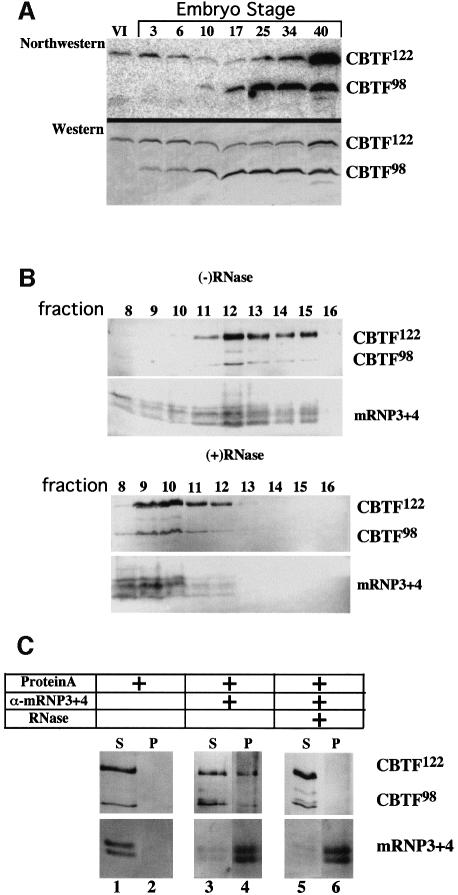

CBTF122 and CBTF98 bind the L1 5′-UTR in vitro and are associated with non-translating mRNPs in vivo

To determine the RNA binding activity of endogenous CBTF122 and CBTF98 during development, we performed a northwestern blot analysis in which total non-yolk proteins from oocytes and embryos were separated by SDS–gel electrophoresis, transferred to membranes and probed with a radiolabelled ribosomal protein L1 5′-UTR. RNA fold analysis predicts that the L1 5′-UTR forms a stem–loop secondary structure (–19.4 kcal/mol) with a single-stranded 5′-terminal polypyrimidine tract (Avni and Shama, 1996). The northwestern blot was first probed with the radiolabelled L1 5′-UTR and subsequently incubated with anti-CBTF122/98 antibody (Figure 3A). The L1 5′-UTR binding profile for CBTF122 is similar to its expression pattern. In contrast, the RNA binding activity of CBTF98 is undetectable before stage 10 and increases steadily thereafter. Northwestern blots of immunoprecipitated CBTF122 and CBTF98 probed with the radiolabelled L1 5′-UTR demonstrated that CBTF122 and CBTF98 are the sole proteins responsible for the RNA binding activity detected on northwestern blots of total protein extracts (data not shown). In addition, binding of CBTF122 and CBTF98 to a truncated form of the L1 5′-UTR that lacks the second half of the stem is reduced 10-fold. This suggests that dsRNA is necessary for efficient binding, in agreement with the initial results of Bass et al. (1994) (data not shown).

Fig. 3. CBTF122 and CBTF98 bind RNA in vitro and are associated with non-translating mRNAs in cleavage stage embryos. (A) Northwestern blot analysis of total soluble proteins from two stage VI oocytes (VI) or two embryos at the stages shown. Proteins were separated by SDS–PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose. The blot was probed first with 32P-labelled L1 5′-UTR (northwestern) and subsequently probed with affinity-purified anti-CBTF122/98 antibody (western). (B) Cytoplasmic proteins from cleavage-stage embryos were incubated in the absence or presence of RNase A and T1 as indicated and then sedimented through a 20–60% nycodenz gradient. Protein precipitated from the indicated fractions was analysed by western blotting using affinity-purified anti-CBTF122/98 antibody or anti-mRNP3+4 antibody. (C) Fractions 12 and 13 of the (–)RNase gradient were mixed and aliquots were incubated in the absence or presence of RNase A and T1. The RNase-treated or untreated aliquots were incubated with anti-mRNP3+4 antiserum (α-mRNP3+4) and protein A beads as shown. Western blots of the supernatant (S) and pellet (P) fractions were probed with affinity-purified anti-p122/p98 (upper panel) or anti-mRNP3+4 (lower panel) antibodies.

To determine whether CBTF122 and CBTF98 associate with mRNAs in vivo, free cytosolic proteins were separated from non-polysomal (mRNP) and polysomal ribonucleoprotein complexes by sedimentation of cytoplasmic extracts through 20–60% Nycodenz gradients (Tafuri and Wolffe, 1993). The distribution of CBTF122 and CBTF98 was determined by western blot analysis (Figure 3B). The sedimentation of RNA within the gradients was confirmed by ethidium bromide staining and northern blot analysis of individual fractions (data not shown). The identification of mRNP-containing fractions was ascertained by examining the distribution of mRNP3+4 (FRGY2), the major protein constituent of translationally inactive mRNPs in oocytes and early embryos (Murray et al., 1992; Tafuri and Wolffe, 1993; Wormington et al., 1996). CBTF122 and CBTF98 co-sediment with mRNP3+4, suggesting that they are associated with non-translating mRNAs in cleavage stage embryos [Figure 3B, (–)RNase]. The co-sedimentation of CBTF122, CBTF98 and mRNP3+4 is RNA dependent, as all three proteins shifted to slower sedimenting fractions of the gradient if extracts were treated with RNase A and T1 prior to centrifugation [Figure 3B, (+)RNase].

To determine whether CBTF122, CBTF98 and mRNP3+4 are associated within the same mRNP complex, mRNP-containing gradient fractions were immunoprecipitated with anti-mRNP3+4 antibody. Supernatant and immunoprecipitated fractions were then separated by SDS–gel electrophoresis and analysed using immunoblots probed individually with anti-mRNP3+4 and anti-CBTF122/98 antibodies (Figure 3C, lane 4). These results indicate that a significant fraction of both CBTF122 and CBTF98 is found in the same mRNP complex as mRNP3+4. As expected, this association is also RNA dependent, as CBTF122 and CBTF98 remain in the supernatant if gradient fractions are pre-treated with RNase prior to immunoprecipitation with anti-mRNP3+4 (Figure 3C, lanes 5 and 6).

Clearly then, both CBTF122 and CBTF98 are present as mRNP components early in development. However, we have shown previously that CBTF122 also has a role in transcriptional control and that it becomes nuclear between stages 8 and 9 (Orford et al., 1998). As RNA binding has been implicated in regulating the subcellular distribution of certain proteins that shuttle between the nucleus and cytoplasm (Guttridge and Smith, 1995; Rudt and Pieler, 1996; Yang et al., 1999), we tested whether RNA binding activity controls the cytoplasmic retention and subsequent nuclear accumulation of CBTF122 during development.

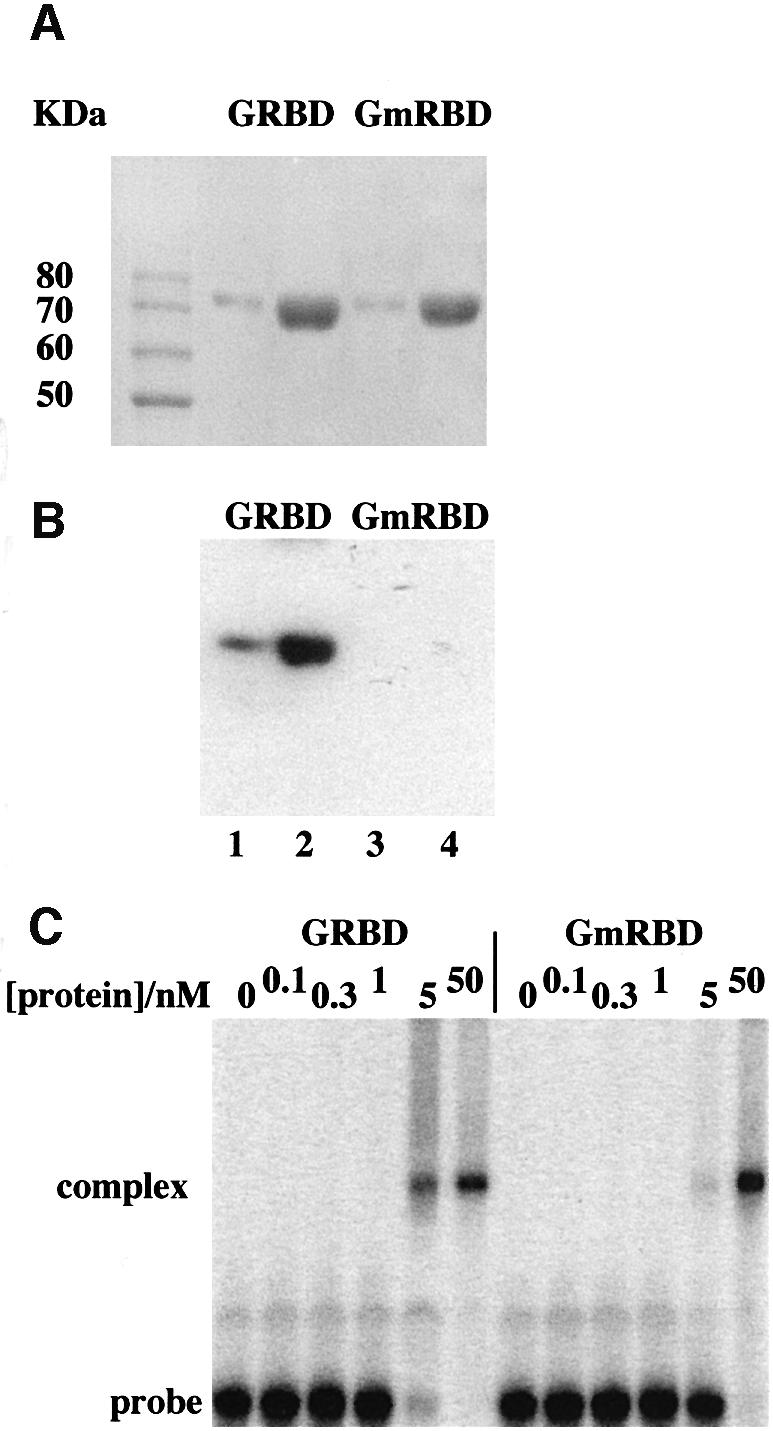

Mutations within the dsRBDs of CBTF122 reduce dsRNA binding activity

A mutation of a conserved phenylalanine to alanine within the staufen and xlrbp60a dsRBDs has been shown to reduce their abilities to bind dsRNA (Bycroft et al., 1995; Krovat and Jantsch, 1996). We introduced this double mutation (F435A and F559A) into the dsRBDs of CBTF122 (CBTF122mRBD) and expressed fragments of the wild-type and mutated proteins containing residues 283–671 as glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins in Escherichia coli (GRBD and GmRBD, respectively). These were purified to produce a single species of the expected size on a Coomassie-stained gel (Figure 4A). Northwestern blotting of these proteins showed that only the wild-type protein binds dsRNA. Therefore, these two F→A mutations render GmRBD unable to form a stable complex with dsRNA (Figure 4B). As this result may have been due to differences in the abilities of the two proteins to refold after SDS–PAGE, we directly tested their binding to dsRNA by gel shift. Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) confirmed that the mutations in GmRBD cause a decrease in its affinity for dsRNA compared with the wild-type protein (Figure 4C).

Fig. 4. Mutation of the dsRBDs of CBTF122 decreases the stability of its complex with dsRNA. (A) The region of CBTF122 containing the dsRBDs (amino acids 283–671) was expressed as a GST fusion protein in E.coli and purified by affinity chromatography on glutathione–Sepharose and a matrix to which a multimerized CBTF binding site had been attached. The proteins shown [1 µg (lanes 2 and 4) or 0.2 µg (lanes 1 and 3)] were run on a 10% SDS–polyacrylamide gel and stained with Coomassie Blue. The 10 kDa ladder (Gibco BRL) is also shown. (B) A duplicate of this gel was transferred to nitrocellulose and underwent a northwestern blot with a 32P-labelled dsRNA 56mer probe. After washing off excess probe, the filter was exposed to X-ray film overnight. (C) GRBD or GmRBD protein was added to 50 pM 32P-labelled 35mer-dsRNA probe at the concentrations shown and allowed to bind at 4°C for 30 min. RNA–protein complexes were then separated by native PAGE and visualized by phosphoimager.

RNA binding is necessary and sufficient for retention of CBTF122 in the cytoplasm of pre-MBT embryos

The effect of the above mutation on the subcellular distribution of CBTF122 was tested by expressing either myc-tagged CBTF122 or CBTF122mRBD protein in embryos and following their locations by immunohistochemistry using anti-myc epitope antibody. Cells ectopically expressing CBTF122 or CBTF122mRBD are stained brown (Figure 5). The myc-tagged CBTF122 protein behaves identically to its endogenous counterpart (Orford et al., 1998), remaining cytoplasmic at stage 7. At that stage, unstained nuclei can be observed through the weak cytoplasmic staining (Figure 5, arrow). It remains cytoplasmic at stage 8 but exhibits punctate nuclear staining before stage 10. In contrast, the CBTF122mRBD protein is predominantly nuclear from the earliest stage at which we can detect it (Figure 5, and see also Figure 7A). As RNA binding activity was necessary for cytoplasmic retention of CBTF122 until stage 9 of development, we next tested which part of the CBTF122 protein was sufficient for prevention of nuclear import prior to that stage.

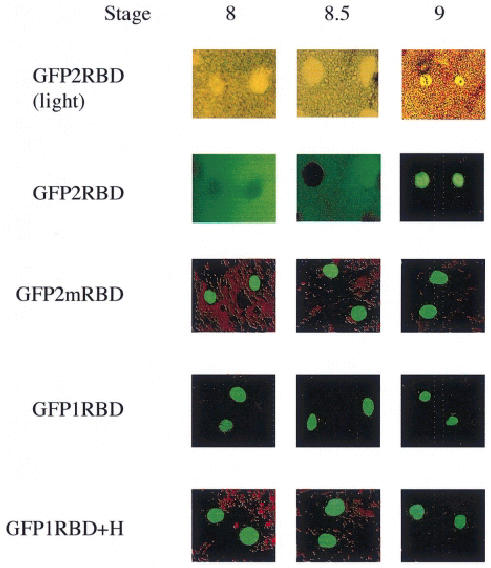

Segments of the CBTF122 protein were fused to green fluorescent protein (GFP) and expressed by RNA injection into the animal pole regions of both blastomeres of two cell embryos. Animal caps were removed from these at various stages to allow visualization of GFP away from the vegetal cells that contain yolk platelets with high intrinsic fluorescence. The region of CBTF122 including the NLS and both dsRBDs (amino acids 326–585; GFP2RBD) was sufficient to mimic the cytoplasmic-to-nuclear translocation of full-length CBTF122 protein. Nuclei show no GFP activity at stage 8, some nuclei show activity at stage 8.5 when endogenous CBTF122 begins to become nuclear, and all nuclei show GFP fluorescence by stage 9 (Figure 6). Consistent with our previous observations (Figure 5), the same mutations as those in CBTF122mRBD made in the context of the GFP fusion (GFP2mRBD) resulted in exclusively nuclear GFP activity from the earliest stages at which we could detect it (stage 5, not shown). In addition, a single dsRBD with the NLS (amino acids 326–454; GFP1RBD) was insufficient for cytoplasmic retention of GFP early in development, as was the addition of the region between the two RBDs (amino acids 326–497; GFP1RBD+H) (Figure 6).

Fig. 6. The NLS and two dsRBDs of CBTF122 are needed for cytoplasmic retention and nuclear translocation of a linked GFP. Embryos from a single female Xenopus were injected with 200 pg of synthetic RNA encoding the following regions of CBTF122 linked to GFP: the NLS and both dsRBDs (GFP2RBD); the NLS and both mutated dsRBDs (GFP2mRBD); the NLS and N-terminal dsRBD (GFP1RBD); the NLS and N-terminal dsRBD and the intervening region between the two dsRBDs (GFP1RBD+H). At the stages shown, animal pole explants were removed and squashed gently under a coverslip to release nuclei from the surrounding, intrinsically fluorescent yolk granules. GFP was then visualized by fluorescence microscopy.

RNA acts as a cytoplasmic anchor for CBTF122

To determine whether RNA binding prevented the nuclear translocation of CBTF122 by physically anchoring this protein in the cytoplasm or by occluding the NLS situated adjacent to the N-terminal dsRBD, we added a second NLS to the N-terminus of myc-tagged CBTF122 (CBTF122NLS+). If RNA were to act as a cytoplasmic anchor for CBTF122, then addition of an extra NLS to CBTF122 should not alter its subcellular localization. However, if the internal NLS were occluded by RNA binding, then the second NLS at the N-terminus would be expected to be accessible to dock with the nuclear pore complex and promote nuclear uptake. Such an approach has been used previously (Beg et al., 1992; Rudt and Pieler, 1996). The addition of the extra NLS did not result in nuclear localization by stage 8. This was true whether the intact CBTF122 protein was used (Figure 7A, top three panels) or whether an extra NLS was inserted into GFP2RBD, N-terminal to the six myc epitopes in this protein (Figure 7A, lower six panels). In agreement with our previous data, the mRBD versions of each protein were nuclear at this stage, whereas the wild-type versions remained in the cytoplasm (Figure 7A).

RNA degradation promotes premature nuclear translocation of CBTF122

One mechanism that immediately suggested itself for the nuclear translocation of CBTF122 at the MBT was the degradation of maternal mRNA that occurs at that stage (Duval et al., 1990). We therefore tested directly whether loss of its cytoplasmic mRNA anchor could trigger the premature nuclear localization of CBTF122. Microinjection of a high concentration of RNase into a single blastomere of a stage 6 embryo caused it to stop dividing, whereas proliferation of a subset of the adjacent cells was affected less markedly, presumably due to dilution of the nuclease. The injected cell (black arrow in Figure 7B) and its neighbours show nuclear CBTF122 staining, whereas cells further from the injection site show perinuclear staining as reported previously at early developmental stages (white arrow in Figure 7B) (Orford et al., 1998). Nuclear staining is absent in the buffer-injected control embryos. All RNase-injected embryos showed some degree of nuclear staining, albeit variable (n = 18, two experiments), whereas only limited perinuclear staining was apparent in controls (n = 20, two experiments).

Discussion

The cytoplasmic function of CBTF122 and CBTF98

The localization of CBTF122 and CBTF98 to the animal pole of the early embryo (Orford et al., 1998, and data not shown) suggests two hypotheses for their cytoplasmic function. CBTF122 and CBTF98 may act to transport or retain specific maternal mRNAs and/or proteins at the animal pole of the embryo, implying a role in embryonic axis determination, similar to the function of staufen (St Johnston et al., 1989, 1991). Alternatively, CBTF122 and CBTF98 may function to repress the translation in the animal pole of certain maternal mRNAs that are evenly distributed throughout the embryo. This would be similar to the negative translational regulation of maternal caudal mRNA by bicoid in Drosophila embryos (Dubnau and Struhl, 1996). A role in the translational repression of localized mRNAs is consistent with, but not definitively demonstrated by, the results from co-immunoprecipitation experiments. These showed that CBTF122 and CBTF98 are part of the same mRNP complex as mRNP3+4 (Figure 3B and C). mRNP3+4 is a constituent of a 320 kDa mRNP particle isolated from Xenopus oocytes that can non-specifically inhibit the translation of mRNAs in vitro (Yurkova and Murray, 1997). The involvement of CBTF122 and CBTF98 and mRNP3+4 in mediating translational repression via a functionally equivalent complex in embryos remains to be established.

A mammalian dsRNA binding protein has been implicated in the translational repression of the sperm-specific, protamine 1 (Prm-1) mRNA during male germ cell differentiation (Lee et al., 1996). The protamine RNA binding protein (Prbp) binds to the cis-acting translational regulatory element in the 3′-UTR of the Prm-1 mRNA and functions as a general repressor of translation. We found in similar experiments that recombinant CBTF122 also non-specifically inhibits translation in vitro (data not shown). However, as a number of recombinant dsRNA binding proteins bind RNA in a non-sequence-specific manner in vitro, these results must be interpreted cautiously. dsRNA binding proteins may recognize specific target sequences in vivo, as suggested for Drosophila staufen (St Johnston et al., 1991; Ferrandon et al., 1994), but such binding sites remain to be determined for the majority of dsRNA binding proteins, including CBTF122 and CBTF98.

A fraction of CBTF122 and CBTF98 is nuclear, chromatin-bound and present as a subunit of the CBTF complex that regulates activation of GATA-2 transcription (Brewer et al., 1995; Orford et al., 1998). The mechanism regulating the nuclear translocation of these proteins is potentially a critical determinant of transcription of their target genes.

RNA binding and the cytoplasmic retention of CBTF122

The decrease in dsRNA binding activity as a result of the mutations made in the dsRBDs is in agreement with the previous findings for both staufen and Xlrbpa (Bycroft et al., 1995; Krovat and Jantsch, 1996). No dimeric complex is observed in conditions of protein excess, thus suggesting that a 35mer dsRNA probe is too short for two protein molecules to bind simultaneously. This is in agreement with the previous report that 18–20 bp was the minimum length required for binding by the 4F proteins (Bass et al., 1994).

In contrast to the native protein, CBTF122mRBD protein is not retained in the cytoplasm during early embryonic development. The two dsRBD domains and NLS linked to GFP recapitulate the cytoplasmic-to-nuclear translocation of CBTF122. However, a single, native dsRBD linked to GFP is not retained in the cytoplasm during early development. This single dsRBD has been shown to bind RNA with greatly reduced affinity when compared with protein containing both dsRBD domains (Bass et al., 1994). The correlation between poor dsRNA binding (either as a result of mutation or truncation) and premature nuclear accumulation provides very strong evidence that RNA binding is necessary to regulate the nuclear translocation of CBTF122. The ability of the dsRBDs to confer both an initial cytoplasmic localization and subsequent nuclear translocation to the GFP reporter shows that RNA binding is sufficient for this regulation. The conservation of the dsRBDs within both CBTF122 and CBTF98 suggests that the same mechanism controls both these proteins. A dsRNA binding domain containing a zinc finger motif has recently been shown to be necessary for the nuclear import of JAZ, a protein whose function is as yet unclear. Mutations inhibiting RNA binding decrease nuclear accumulation of JAZ, an effect opposite to that observed for CBTF122 (Yang et al., 1999). This suggests that the simple binding of dsRNA is insufficient to render a protein cytoplasmic, and thus RNA binding specificity or protein–protein interactions are also likely to have roles.

The inhibition of nuclear import by RNA binding represents a novel mechanism for regulating the activity of a transcription factor by nuclear translocation. This mechanism has been suggested previously for Oct 1 (Guttridge and Smith, 1995), and RNA has been shown to occlude and inactivate the NLS of TFIIIA (Rudt and Pieler, 1996). However, in the case of TFIIIA, the biological significance for transcription regulation was unclear as this molecule is also involved in the export of 5S RNA from the nucleus at the stages examined. Several transcription factors have been shown to form complexes with RNA, for example WT1 (Ye et al., 1996), bicoid (Rivera-Pomar et al., 1996), glucocorticoid receptor (Eggert et al., 1997) and PU.1 (Hallier et al., 1996). Controlling transcription factor activity by regulating nuclear import is also common (Whiteside and Goodbourn, 1993; Vandromme et al., 1996). The mechanism we have observed for CBTF122 therefore may be widespread. However, in at least one case, that of WT1, RNA binding changes are not associated with a change in subcellular location (Ye et al., 1996).

The addition of an extra NLS to CBTF122 did not circumvent its cytoplasmic retention during early development, whether in the context of the native protein or a GFP fusion. This strongly suggests that CBTF122 is physically anchored within the cytoplasm via its interaction with dsRNA. This mechanism of cytoplasmic retention by anchoring, as opposed to masking of an NLS, is analogous to that observed for another Xenopus protein, xnf7, which alters its cytoplasm-to-nucleus distribution at the same stages as does CBTF122. However, the 22 amino acid cytoplasmic retention domain of xnf7 (Li et al., 1994a,b) lacks identity with any sequences in CBTF122 and there is no evidence that it binds to RNA.

Nuclear translocation of CBTF122 at the MBT and mRNA turnover

We tested three possible mechanisms that might underlie the nuclear translocation of CBTF122 at the MBT. Two of these, changes in phosphorylation state (Whiteside and Goodbourn, 1993; Li et al., 1994a; Vandromme et al., 1996) and cytoskeleton binding (Dong et al., 2000), have previously been shown to be important for the regulation of nuclear translocation. However, disruption of the cytoskeleton with either nocodazole or cytochalasin B failed to affect the subcellular distribution of CBTF122 as analysed by immunohistochemistry. Similarly, immunoprecipitation from embryos incubated with 32P failed to detect labelling of CBTF122 (which was visible by Coomassie staining), whereas other components of the CBTF complex were phosphorylated. These data strongly suggest that neither direct phosphorylation nor the cytoskeleton is involved in regulating CBTF122 localization in embryos at the MBT. In contrast, degradation of RNA in blastomeres prior to the MBT leads to nuclear accumulation of CBTF122. Thus, the degradation of the bulk of maternal mRNA that occurs at the MBT (Duval et al., 1990) is highly likely to release the cytoplasmic pool of CBTF122 for nuclear import. Clearly, this suggests a potentially novel mechanism for regulating the nuclear import of a class of transcriptional activators, which are also RNA binding proteins, and thereby couples activation of the zygotic genome with depletion of the maternal mRNA pool.

Materials and methods

cDNA isolation and DNA sequencing

A Xenopus stage 11.5 embryonic λ-Zap (Stratagene) cDNA expression library (kindly provided by D.DeSimone, University of Virginia) was screened (250 000 plaques) for LacZ fusion proteins that bind to a 32P-labelled L1 5′-UTR. A plasmid containing a 1.8 kb insert (pCBTF-1.8) was isolated by in vivo excision from a single positive λZAP plaque. To obtain additional cDNAs, an insert was used as a hybridization probe to re-screen the same cDNA library. The longest cDNA isolated was 3 kb. To obtain the remaining coding sequences and 5′-UTR, a 5′ RACE procedure (Bethesda Research Laboratories, BRL) was performed using Xenopus egg poly(A)+ mRNA as a template. All cDNAs were sequenced in both directions using the dideoxynucleotide chain termination method using modified T7 DNA polymerase (Sequenase II; US Biochemical Corp.).

Plasmid constructs

Myc-tagged CBTF122 and CBTF98. A full-length cDNA, corresponding to the CBTF122 mRNA, was constructed by subcloning the sequences contained in pCBTF-RACE (SpeI–Tth111I), pCBTF-1.8 (Tth111I–AflII) and pCBTF-G11 (AflII–XhoI) into pBluescript, creating pCBTF122-BS. The full-length cDNA corresponding to the CBTF98 mRNA (4F.1) was kindly provided by B.Bass (Bass et al., 1994). For optimal expression of synthetic CBTF mRNAs, the CBTF122 and CBTF98 coding regions were subcloned into pSP64TEN (Klein and Melton, 1994). A double-stranded oligonucleotide encoding the myc-epitope tag (Evan et al., 1985) was subcloned into the pSP64TEN constructs between an NcoI site engineered at the ATG translation start sequence and an internal ApaI site, creating pSP64T(CBTF122myc) and pSP64T(CBTF98myc), respectively.

dsRNA binding domain mutants. Site-directed mutagenesis was performed on pSP64T(CBTF122myc) to change two TTT codons (1223–1225 and 1581–1583) to TGC. This resulted in a phenylalanine→alanine substitution at positions 409 and 528.

Mutagenesis was carried out using the GeneEditor in vitro Site-Directed Mutagenesis System (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Mutations were checked by Sanger dideoxy sequencing using Sequenase II (USB).

Construction of GFP fusion proteins. The plasmid pCS2*mt-SGP (a gift from M.Klymkowsky) was used to introduce subfragments of CBTF122 into the 5′ end of GFP. Fragments of CBTF122 and CBTF122mRBD were amplified by PCR introducing EcoRI and NheI sites in their 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively. The following fragments were excised and subcloned into pCS2*mt-SGP: regions from CBTF122RBD– and CBTF122 containing the NLS and both RBDs (amino acids 326–585) termed GFP2RBD and GFP2mRBD, respectively; the CBTF122 NLS and N-terminal RBD (amino acids 326–454) termed GFP1RBD; and the CBTF122 NLS and the N-terminal RBD and hinge region (amino acids 326–497) termed GFP1RBD+H. Candidates carrying the fragments were sequenced as above using the N-terminal primer or SP6 promoter primer.

Incorporation of a second NLS. A bi-partite NLS with the same sequence as the CBTF122 NLS was subcloned into the N-terminus of CBTF122. The following oligonucleotides were synthesized containing the NLS sequence, a 5′ ApaI and a 3′ SpeI restriction site: 5′-GTACTAACTAGTAAGCGCCCTATTGAGGAGGATGGAGATGACAAGTCGCC AAGTAAGAAGAAAAAGAAGGGGCCCAAGAAA and 5′-TTTCTT GGGCCCCTTCTTTTTCTTCTTACTTGGCGACTTGTCATCTCCAT CCTCCTCAATAGGGCGCTTACTAGTTAGTAC. Oligonucleotides were inserted into the ApaI/SpeI sites in p-UT2Sfi(CBTF122) and sequenced.

Expression of truncated CBTF122

BamHI–EcoRI fragments (1.3 kb) encoding residues 283–671 of CBTF122 and CBTF122mRBD were cloned into pGEX-2T and transformed into E.coli DH5α. The GST fusion proteins encoded by these plasmids were expressed and purified as described previously (Read et al., 1994). The fusion protein was further purified by binding it to a double-stranded oligonucleotide–Sepharose column containing the sequence 5′-GAT CCGACTGGCTGGCGGAGGCTTGTGATCGGCTGGCCCG-3′ and elut ing with 500 mM NaCl in 1× EB (Brewer et al., 1995). The fusion protein was stored at –20°C as a 50% glycerol solution.

EMSA and northwestern analysis

EcoRI or HindIII linearized pGemCAT (Olmedo et al., 1990) was used as a template for a transcription reaction using SP6 or T7 RNA polymerase. This produced a 56 bp product corresponding to the plus and minus strands of the polylinker. In each case one strand was internally labelled using [α-32P]ATP. The template DNA was then degraded using DNase I and unincorporated nucleotides removed using a G25 column. The labelled strand was then annealed to the opposing strand. Northwestern analyses were performed as described previously (Gatignol et al., 1991). The bandshift reactions were performed as described by Brewer et al. (1995) using 50 pM dsRNA probe (an end-labelled 35mer synthetic dsRNA oligonucleotide) and 0–50 nM protein.

Anti-CBTF122/98 antibody and RNA synthesis

To generate antibodies against both CBTF proteins, the CBTF-1.8 cDNA insert, containing coding sequences common to both CBTF122 and CBTF98 was subcloned into the pGEX-2T vector (Pharmacia). A GST–CBTF fusion protein was expressed in E.coli and purified by glutathione–agarose affinity chromatography. The affinity-purified GST–CBTF was used by Spring Valley Laboratories, USA, to generate the rabbit polyclonal anti-CBTF122/98 antiserum. Antibody was affinity purified using SDS–gel-purified FLAG-CBTF122 immobilized on a Hybond C membrane (Harlow and Lane, 1988). pFLAG-CBTF122 was generated by cloning the CBTF122 open reading frame, from ApaI to SspI, into the KpnI site of the pFLAG-ATS vector (Kodak-IBI). FLAG-CBTF122, expressed in E.coli, was affinity purified by column chromatography utilizing a monoclonal antibody against the FLAG epitope, following the manufacturer’s protocols (Kodak-IBI). The L1 5′-UTR, 5′-GGGAACAAA AGCTGGGTACCCTTTTCTCTTCGTGGCCGCTGTGGAGAAGCG CGAGGAGCCATG (pBluescript vector sequence underlined), was transcribed in vitro using T3 RNA polymerase. The vector sequence was deleted by RNaseH digestion after hybridization of the appropriate antisense DNA oligo to generate the L1 5′-UTR binding probe as described (Hyman and Wormington, 1988).

Oocyte and embryo manipulation

Oocytes isolated from Xenopus ovaries were defolliculated with collagenase, cultured in modified Barth’s solution (Gurdon, 1976) at 18–20°C and staged according to Dumont (1972). Maturation was induced by the addition of progesterone (final concentration 10 µg/ml) and assayed for by the appearance of a white spot at the animal pole. Stage VI oocyte nuclei were obtained as described (Guille, 1999). Embryos were obtained as described by Smith and Slack (1983) and staged according to Nieuwkoop and Faber (1967). RNA preparation and microinjection were carried out as described previously (Guille, 1999; Moore and Guille, 1999). Embryos at the two-cell stage were injected with 4 nl of RNA solution, those at stage 6 were injected with 1 nl of RNase solution (50 ng of RNase) containing 10 mg/ml rhodamine dextran (+RNase) or 10 mg/ml rhodamine dextran alone (control).

RNA isolation and analysis

Total RNA from oocytes and embryos, and polysomal and non-polysomal RNA from oocytes, were isolated as described previously (Wormington, 1991). Northern blot analysis was performed according to Sambrook et al. (1989), and blots were probed with 32P-labelled antisense RNA transcribed in vitro from pCBTF-1.8. Embryonic extracts were fractionated on Nycodenz gradients as described (Tafuri and Wolffe, 1993), with minor modifications. For RNase treatment, nuclear and embryonic extracts, and nycodenz gradient fractions were incubated in the presence of 100 µg/ml RNase A (Sigma) and 1500 U/ml RNase T1 (Amersham) at 37°C for 30 min either before centrifugation or before immunoprecipitation.

Immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation

Immunoblot analyses were performed as described (Wormington et al., 1996). Affinity-purified anti-CBTF122/98 antibody was used at a 1:250 dilution. A guinea pig polyclonal antiserum directed against purified mRNP3+4 was used at a 1:20 000 dilution (Murray et al., 1991). Filters were incubated with appropriate alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibodies. Immunoreactive proteins were visualized using a Promega western blot AP detection system according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Extracts for immunoprecipitation were prepared as described (Wormington, 1989). Extracts were precleared with protein A–Sepharose before immunoprecipitation with either anti-CBTF122/98 or anti-mRNP3+4 antibodies. Immunoprecipitated proteins were extracted with SDS sample buffer and analysed by SDS–PAGE.

Immunohistochemistry

The exogenous myc-tagged CBTF122 was visualized by whole-mount immunohistochemistry using 9E10 antibody (Santa Cruz) as described previously (Robinson and Guille, 1999). Endogenous CBTF122/98 was visualized by whole-mount immunohistochemistry, using antiserum kindly provided by B.Bass, as described previously (Orford et al., 1998).

Visualization of GFP

GFP was visualized in animal cap explants by placing them in MBS saturated with ficoll containing 0.5 µg/ml DAPI. A coverslip was then dropped onto the explant from 2 cm, lysing many of the cells, and allowing the GFP- and DAPI-stained nuclei to be observed using a Nikon E800 Eclipse microscope equipped with fluorescence and dedicated GFP and DAPI filters.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Mike Klymkowski, Mary Murray and Brenda Bass for providing us with reagents, and to Colyn Crane-Robinson, Colin Sharpe and Alan Thorne for suggesting improvements to the manuscript. This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust (grants 051703, 046708 and 056901 to M.G.), the BBSRC (grant GO6890 to M.G. and G.K.; postgraduate studentships to R.O. and S.E.) and by the National Institutes of Health (grant HD17691 to M.W.).

References

- Avni D. and Shama,S. (1996) Translational control of ribosomal protein mRNAs in eukaryotes. In Hershey,J.W.B., Mathews,M.B. and Sonenberg,N. (eds), Translational Control. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, pp. 363–368. [Google Scholar]

- Bass B.L., Hurst,S.R. and Singer,J.D. (1994) Binding-properties of newly identified Xenopus proteins containing dsRNA-binding motifs. Curr. Biol., 4, 301–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beg A.A., Ruben,S.M., Scheinman,R.I., Haskill,S., Rosen,C.A. and Baldwin,A.S.,Jr (1992) IκB interacts with the nuclear localization sequences of the subunits of NF-κB: a mechanism for cytoplasmic retention. Genes Dev., 6, 1899–1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer A.C., Guille,M.J., Fear,D.J., Partington,G.A. and Patient,R.K. (1995) Nuclear translocation of a maternal CCAAT factor at the start of gastrulation activates Xenopus GATA-2 transcription. EMBO J., 14, 757–766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burd C.G. and Dreyfuss,G. (1994) Conserved structures and diversity of functions of RNA-binding proteins. Science, 265, 615–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bycroft M., Grunert,S., Murzin,A.G., Procter,M. and St Johnston,D. (1995) NMR solution structure of a double-stranded RNA-binding domain from Drosophila staufen protein reveals homology to the N-terminal domain of ribosomal protein S5. EMBO J., 14, 4385–4391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corthesy B. and Kao,P.N. (1994) Purification by DNA affinity chromatography of two polypeptides that contact the NF-AT DNA binding site in the interleukin 2 promoter. J. Biol. Chem., 269, 20682–20690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong C., Li,Z., Alvarez,R.,Jr, Feng,X.H. and Goldschmidt-Clermont,P.J. (2000) Microtubule binding to Smads may regulate TGF β activity. Mol. Cell, 5, 27–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyfuss G., Matunis,M.J., Pinol,R.S. and Burd,C.G. (1993) hnRNP proteins and the biogenesis of mRNA. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 62, 289–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubnau J. and Struhl,G. (1996) RNA recognition and translational regulation by a homeodomain protein. Nature, 379, 694–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumont J.N. (1972) Oogenesis in Xenopus laevis (Daudin) I. Stages of oocyte development in laboratory maintained animals. J. Morphol., 136, 153–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duval C., Bouvet,P., Omilli,F., Roghi,C., Dorel,C., LeGuellec,R., Paris,J. and Osborne,H.B. (1990) Stability of maternal mRNA in Xenopus embryos: role of transcription and translation. Mol. Cell. Biol., 10, 4123–4129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggert M., Michel,J., Schneider,S., Bornfleth,H., Baniahmad,A., Fackelmayer,F.O., Schmidt,S. and Renkawitz,R. (1997) The glucocorticoid receptor is associated with the RNA-binding nuclear matrix protein hnRNP U. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 28471–28478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evan G.I., Lewis,G.K., Ramsay,G. and Bishop,J.M. (1985) Isolation of monoclonal antibodies specific for human c-myc proto-oncogene product. Mol. Cell. Biol., 5, 3610–3616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrandon D., Elphick,L., Nusslein-Vollhard,C. and St Johnston,D. (1994) Staufen protein associates with the 3′UTR of bicoid mRNA to form particles that move in a microtubule-dependent manner. Cell, 79, 1221–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleenor D.E., Langdon,S.D., Decastro,C.M. and Kaufman,R.E. (1996) Comparison of human and Xenopus GATA-2 promoters. Gene, 179, 219–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatignol A., Buckler,W.A., Berkhout,B. and Jeang,K.T. (1991) Characterization of a human TAR RNA-binding protein that activates the HIV-1 LTR. Science, 251, 1597–1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guille M.J. (1999) Microinjection into Xenopus oocytes and embryos. In Guille,M. (ed.), Molecular Methods in Developmental Biology: Xenopus and Zebrafish. Methods in Molecular Biology, Vol. 137. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ, pp. 111–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurdon J.B. (1976) Injected nuclei in frog oocytes: fate, enlargement and chromatin dispersal. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol., 36, 523–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttridge K.L. and Smith,L.D. (1995) Xenopus interspersed RNA families, Ocr and XR, bind DNA-binding proteins. Zygote, 3, 111–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallier M., Tavitian,A. and Moreau-Gachelin,F. (1996) The transcription factor Spi-1/PU.1 binds RNA and interferes with the RNA-binding protein p54nrb*. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 11177–11181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlow E. and Lane,D. (1988) Antibodies: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Hyman L.E. and Wormington,W.M. (1988) Translational inactivation of ribosomal protein mRNAs during Xenopus oocyte maturation. Genes Dev., 2, 598–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao P.N., Chen,L., Brock,G., Ng,J., Kenny,J., Smith,A.J. and Corthesy,B. (1994) NFAT-sequence-specific DNA-binding protein is a novel heterodimer of 45-kDa and 90-kDa subunits. J. Biol. Chem., 269, 20691–20699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein P.S. and Melton,D.A. (1994) Induction of mesoderm in Xenopus laevis embryos by translation initiation factor 4E. Science, 265, 803–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krovat B.C. and Jantsch,M.F. (1996) Comparative mutational analysis of the double-stranded RNA-binding domains of Xenopus laevis RNA-binding protein A. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 28112–28119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K., Fajardo,M.A. and Braun,R.E. (1996) A testis cytoplasmic RNA-binding protein that has the properties of a translational repressor. Mol. Cell. Biol., 16, 3023–3034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Shou,W., Kloc,M., Reddy,B.A. and Etkin,L.D. (1994a) Cytoplasmic retention of Xenopus nuclear factor-7 before the mid-blastula transition uses a unique anchoring mechanism involving a retention domain and several phosphorylation sites. J. Cell Biol., 124, 7–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.X., Shou,W., Kloc,M., Reddy,B.A. and Etkin,L.D. (1994b) The association of Xenopus nuclear factor 7 with subcellular structures is dependent upon phosphorylation and specific domains. Exp. Cell Res., 213, 473–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minegishi N., Ohta,J., Suwabe,N., Nakaushi,H., Ishihara,H., Hayashi,N. and Yamamoto,M. (1998) Alternative promoters regulate transcription of the mouse GATA-2 gene. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 3625–3634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore W.M. and Guille,M.J. (1999) Preparation and testing of synthetic mRNA for microinjection. In Guille,M. (ed.), Molecular Methods in Developmental Biology: Xenopus and Zebrafish. Methods in Molecular Biology, Vol. 137. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ, pp. 99–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray M.T., Krohne,G. and Franke,W.W. (1991) Different forms of soluble cytoplasmic mRNA binding proteins and particles in Xenopus laevis oocytes and embryos. J. Cell Biol., 112, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray M.T., Schiller,D.L. and Franke,W.W. (1992) Sequence analysis of cytoplasmic mRNA-binding proteins of Xenopus oocytes identifies a family of RNA-binding proteins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 89, 11–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwkoop P.D. and Faber,J. (1967) Normal Table of Xenopus laevis (Daudin). North-Holland Publishing Company, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Nony P., Hannon,R., Gould,H. and Felsenfeld,G. (1998) Alternate promoters and developmental modulation of expression of the chicken GATA-2 gene in hematopoietic progenitor cells. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 32910–32919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmedo G., Ninfa,E.G., Stock,J. and Youngman,P. (1990) Novel mutations that alter regulation of sporulation in Bacillus subtilis—evidence that phosphorylation of regulatory protein SpooA controls the initiation of sporulation. J. Mol. Biol., 215, 359–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orford R.L., Robinson,C., Haydon,J., Patient,R.K. and Guille,M.J. (1998) The maternal CCAAT box transcription factor which controls GATA-2 expression is novel, developmentally regulated and contains a dsRNA-binding subunit. Mol. Cell. Biol., 18, 5557–5566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partington G.A., Bertwistle,D., Nicolas,R.H., Kee,W.J., Pizzey,J.A. and Patient,R.K. (1997) GATA-2 is a maternal transcription factor present in Xenopus oocytes as a nuclear complex which is maintained throughout early development. Dev. Biol., 181, 144–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read C.M., Cary,P.D., Preston,N.S., Lnenicek-Allen,M. and Crane-Robinson,C. (1994) The DNA-sequence specificity of HMG boxes lies in the minor wing of the structure. EMBO J., 13, 5639–5646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Pomar R., Niessing,D., Schmidt-Ott,U., Gehring,W.J. and Jackle,H. (1996) RNA binding and translational suppression by bicoid. Nature, 379, 746–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins J., Dilworth,S.M., Laskey,R.A. and Dingwall,C. (1991) Two interdependent basic domains in nucleoplasmin nuclear targeting sequence: identification of a class of bipartite nuclear targeting sequence. Cell, 64, 615–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson C. and Guille,M. (1999) Xenopus immunohistochemistry. In Guille,M. (ed.), Molecular Methods in Developmental Biology: Xenopus and Zebrafish. Methods in Molecular Biology, Vol. 137. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ, pp. 89–99. [Google Scholar]

- Rudt F. and Pieler,T. (1996) Cytoplasmic retention and nuclear import of 5S ribosomal RNA containing RNPs. EMBO J., 15, 1383–1391. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J., Fritsch,E.F. and Maniatis,T. (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher J.M., Lee,K., Edelhoff,S. and Braun,R.E. (1995) Spnr, a murine RNA-binding protein that is localized to cytoplasmic microtubules. J. Cell Biol., 129, 1023–1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J.C. and Slack,J.M.W. (1983) Dorsalisation and neural induction: properties of the organiser in Xenopus laevis.J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol., 78, 299–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St Johnston D., Driever,W., Berleth,T., Richstein,S. and Nusslein,V.C. (1989) Multiple steps in the localization of bicoid RNA to the anterior pole of the Drosophila oocyte. Development, 107, 13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St Johnston D., Beuchle,D. and Nusslein,V.C. (1991) Staufen, a gene required to localize maternal RNAs in the Drosophila egg. Cell, 66, 51–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sykes T.G., Rodaway,A.R.F., Walmsley,M.E. and Patient,R.K. (1998) Suppression of GATA factor activity causes axis duplication in Xenopus. Development, 125, 4595–4605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tafuri S.R. and Wolffe,A.P. (1993) Selective recruitment of masked maternal mRNA from messenger ribonucleoprotein particles containing FRGY2 (mRNP4). J. Biol. Chem., 268, 24255–24261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai F.Y. and Orkin,S.H. (1997) Transcription factor GATA-2 is required for proliferation/survival of early hematopoietic cells and mast cell formation, but not for erythroid and myeloid terminal differentiation. Blood, 89, 3636–3643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai F.Y., Keller,G., Kuo,F.C., Weiss,M., Chen,J., Rosenblatt,M., Alt,F.W. and Orkin,S.H. (1994) An early haematopoietic defect in mice lacking the transcription factor GATA-2. Nature, 371, 221–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandromme M., Gauthier-Rouviere,C., Lamb,N. and Fernandez,A. (1996) Regulation of transcription factor localization: fine tuning gene expression. Trends Biochem. Sci., 21, 59–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walmsley M.E., Guille,M.J., Bertwistle,D., Smith,J.C., Pizzey,J.A. and Patient,R.K. (1994) Negative control of Xenopus GATA-2 by activin and noggin with eventual expression in precursors of the ventral blood islands. Development, 120, 2519–2529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside S.T. and Goodbourn,S. (1993) Signal transduction and nuclear targeting: regulation of transcription factor activity by subcellular localisation. J. Cell Sci., 104, 949–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wormington M. (1989) Developmental expression and 5S rRNA-binding activity of Xenopus laevis ribosomal protein L5. Mol. Cell. Biol., 9, 5281–5288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wormington M. (1991) Preparation of synthetic mRNAs and analyses of translational efficiency in microinjected Xenopus oocytes. Methods Cell Biol., 36, 167–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wormington M., Searfoss,A.M. and Hurney,C.A. (1996) Overexpression of poly (A) binding protein prevents maturation-specific deadenylation and translational inactivation in Xenopus oocytes. EMBO J., 15, 900–909. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M., May,W.S. and Ito,T. (1999) JAZ requires the double-stranded RNA-binding zinc finger motifs for nuclear localisation. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 27399–27406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Y., Raychaudhuri,B., Gurney,A., Campbell,C.E. and Williams,B.R.G. (1996) Regulation of WT1 by phosphorylation: inhibition of DNA binding, alteration of transcriptional activity and cellular translocation. EMBO J., 15, 5606–5615. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yurkova M.S. and Murray,M.T. (1997) A translation regulatory particle containing the Xenopus oocyte Y box protein mRNP3+4. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 10870–10876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y.H. et al. (1998) Rescue of the embryonic lethal hematopoietic defect reveals a critical role for GATA-2 in urogenital development. EMBO J., 17, 6689–6700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zon L.I., Mather,C., Burgess,S., Bolce,M., Harland,R.M. and Orkin,S.H. (1991) Expression of GATA binding proteins during embryonic development in Xenopus laevis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 88, 10642–10646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]