Abstract

PixD (Slr1694) is a BLUF (blue-light using FAD) photoreceptor used by the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 to control phototaxis toward blue light. In this study we probe the involvement of a conserved Tyr8-Gln50-Met93 triad in promoting an output signal upon blue light excitation of the bound flavin. Analysis of acrylamide quenching of Trp91 fluorescence shows that the side chain of this residue remains partially solvent exposed in both the lit and dark states. Mutational analysis demonstrates that substitution mutations at Tyr8 and Gln50 result in the loss of the photocycle while a mutation of Met93 does not appreciably disturb the formation of the light excited state and only minimally accelerates its decay from 5.7 s to 4.5 s. However, mutations in Tyr8, Gln50 and Met93 disrupt the ability of PixD dimers to interact with PixE to form a higher ordered PixD10-PixE5 complex, which is indicative of a lit conformational state. Solution NMR spectroscopy and X-ray crystallographic analyses confirm that a Tyr8 to Phe mutation is locked in a pseudo light excited state revealing flexible areas in PixD that likely constitute part of an output signal upon light excitation of wild type PixD.

Various photosynthetic and non-photosynthetic organisms use photoreceptors to regulate their physiology and behavior in response to light absorption at specific intensities and wavelengths. Recently, a family of photoreceptors termed blue light utilizing flavin (BLUF) was identified among a range of algal and bacterial proteins, all of which share a common protein fold and the use of FAD as a chromophore to absorb blue light (1–5). Examples of well-characterized BLUF photoreceptors include AppA that controls photosynthesis gene expression in Rhodobacter sphaeroides in response to blue light intensity and PixD (Slr1694) that is involved in regulation of blue light phototaxis of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 (1–5).

X-ray crystallographic analyses of several different BLUF domains indicate that they contain the same βαββαββ fold that is approximately 100 amino acid residues long, differing chiefly in the length of the final β5 strand and the presence of small α-helical extensions located C-terminal of the core BLUF domain (6–10). Early attention focused on a conserved glutamine (Gln50 in PixD) proximal to FAD of which the side chain orientation and hydrogen bond network has been a point of considerable debate (7–16). An early model suggested that dark adapted BLUF domain has a Trp (Trp91 in PixD) hydrogen bonded to Gln50 and that light-induces swapping of Trp91 with a nearby conserved methionine (Met93 in PixD) (6). However, recent fluorescence excitation and acrylamide quenching analysis of the BLUF domain from AppA indicated no significant light induced movement of the homologus Trp (17–18). These studies also suggest that Met93 rather then Trp91 is hydrogen bonded to Gln50 in the dark state as is observed in 9 of 10 subunits of PixD in the crystal structure (6).

There is considerable evidence that light excitation of the flavin ring results in alterations in the Tyr8-Gln50-Met93 hydrogen bond network. Specifically, photoexcitation of the flavin ring promotes donation of an electron and proton from Tyr8 to the light excited flavin (11, 19). This is followed by rearrangement of a hydrogen bond between Gln50 and the flavin ring such that a new hydrogen bond is formed between Gln50 and O4 of the flavin ring (11, 19). The newly formed Gln50-O4 hydrogen bond results in a 10 nm spectral shift of flavin absorption (20). Reversion of this spectral shift occurs upon decay to the ground state where Gln50 is hydrogen bonded to N5 of the flavin ring. It is still debatable whether light excitation of the flavin causes a reorientation of Gln50 or a tautomeric shift that ultimately induces a change in the Gln50 hydrogen bond interactions with the flavin ring (16, 21–22). Also not yet addressed is whether Met93 remains hydrogen bonded to Gln50 when the flavin is in its light excited state. It is also unclear how light-induced rearrangements of these protein/flavin hydrogen bonds ultimately affect the length of the β5 strand and changes in the C-terminus of the BLUF domain. Presumably, these changes are caused by a light induced alteration of the Gln50-Met93 hydrogen bond, but this has not been directly addressed.

Prior studies have revealed that PixD exists as dimer in solution and that subsequent interaction of PixD dimers with another protein called PixE results in the formation of a large oligomeric complex comprised of 10 subunits of PixD and 5 subunits of PixE (23–25). It has been shown that light excitation of the PixD10-PixE5 supercomplex results in disassembly into PixD dimers and PixE monomers (25). One interface among PixD dimers in the PixD10-PixE5 supercomplex involves an interaction between the α3 helix in one PixD subunit with a loop in a neighboring PixD subunit that connects the β4 and β5 strands. The β4 and β5 “domain interaction” loop is also known to become more dynamic when the flavin is in its light excited state (27–28). In this study we address movement of the loop between the β4 and β5 strand in PixD by monitoring light driven changes in acrylamide quenching of Trp91 fluorescence in wild type PixD as well as in Tyr8, Gln50 and Met93 mutant derivatives. We also monitor global changes in the PixD structure with a combination of solution NMR and X-ray crystallography. Our study provides new insight to the output signal that involves an alteration of the hydrogen bond network in the Tyr8-Gln50-Met93 triad. We show that the α1 and α3 helices, β2 and β3 strands and loops between β4-β5 and α3-α4 undergo alterations in a PixD mutant that is locked in a pseudo lit state and unable to productively interact with PixE.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Expression Plasmids Construction

A PixD expression plasmid for the Y8F mutant was previously constructed and provided by Dr. Shinji Masuda (29). Quick Change Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies) was used to construct the PixD W91A, M93A and Q50A mutants as described previously (6). To express PixE with a hexahistidine tag before the amino terminal Met, its coding fragment was amplified from the genomic DNA of Synechocystis PCC6803 by PCR. The fragment was then cloned into the NdeI/SalI sites of vector pET29a (Novagen).

Protein Expression and Purification

PixD and its mutants were expressed and purified as described previously (4). PixEHis6 was overexpressed in Escherichia coli Tuner (DE3) using 1 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside to induce the expression at 16°C for 16 hr. The cell pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer containing 0.05 M sodium phosphate (pH 8.0), 0.3 M NaCl, 10% glycerol, and 0.02 M imidazole. The cells were then passed through a continuous flow microfluidizer (Microfluidics). After centrifuging at 20,000 rpm (47810 g) for 30 min, the supernatant was incubated with Ni2+ charged His6-tag binding resin (Novagen) at 4°C for 1 hr. The resin was then washed with 0.06 M imidazole and the protein was eluted with 0.25 M imidazole. The PixEHis6 elution was then mixed with purified PixD (or its mutants) at a molar ratio of ~1:2 and incubated in dark for at least 2 hr before loading onto Superose 6 gel filtration column. The gel filtration analyses were performed as described before with 10–20 μM protein in buffer containing 0.02 M Tris (pH 8.0) and 0.1 M NaCl (25).

Acrylamide Quenching of Tryptophan Fluorescence

Fluorescence measurements were performed at 4°C with a Perkin-Elmer LS 50B luminescence spectrometer equipped with a circulating NESLAB water bath to control sample temperature. Fluorescence quenching experiments were performed according to the method described by Eftink et al. (30). Briefly, a small aliquot of 8.0 M of acrylamide, solubilized in the same buffer used for protein solution, was progressively added to 2.0 ml of protein sample. Dark and light state protein samples were obtained as described before (6). Fluorescence emission signal was monitored until stabilized before each dark state data point collection to make sure that protein returns to its ground state. Tryptophan fluorescence emission intensity at 360 nm (bandpass: 13 nm) was recorded with an excitation wavelength of 295 nm (bandpass: 5 nm). The protein samples were diluted to make sure the absorption at 295 nm was less than 0.1 to minimize the inner absorption effect. The inner-filter effect caused by protein and acrylamide absorption at 295 nm and the dilution effect caused by adding acrylamide solution were corrected according to the method described by Prieto et al. (31). Both flavin and tryptophan fluorescence spectra were recorded before and after the quenching experiment to monitor possible spectral change caused by acrylamide.

Theoretical Background of Acrylamide Fluorescence Quenching

Acrylamide is an excellent tryptophan fluorescence quencher (Q) used to probe tryptophan positioning in a protein (32). This quencher can decrease fluorescence emission from Trp by collisional (or dynamic) quenching which involves diffusional collision of acrylamide with light excited Trp (Trp*) that effectively quenches Trp*. A second quenching process is static quenching in which a “static” Trp*-acrylamide complex is present. Trp* quenching then happens nearly instantaneously because of the short distance.

For proteins that contain a homogeneous fluorophore, a combination of collisional and static quenching can be described by Stern-Volmer relationship (equation 1) (33):

| (1) |

in which F0 and F are fluorescence intensities in the absence or presence of quencher and KSV and V are Stern-Volmer quenching constants used to describe collisional and static quenching, respectively.

For systems that only exhibit collisional quenching, equation 1 can be written as

| (2) |

For protein that contain heterogeneous fluorophores, the Stern-Volmer relationship can also be written as

| (3) |

where fi is the maximum fractional fluorescence for fluorophore i, and KSVi and Vi are corresponding collisional or static quenching constants . If only collisional quenching is considered, equation 3 can be written as

| (4) |

or

| (5) |

where KQef f= Σ KSVi is taken as “effective” quenching constant, and is taken as “effective” fractional maximum accessible fluorescence of which 100% indicates a homogeneous fluorophore conformation (34).

Absorption Spectroscopy

Absorption spectra were recorded using HP 8453E UV-visible spectrophotometer. Light state spectra were taken on the same sample but with continuous illumination of white light from MK II fiber optic light source equipped with a 150 W halogen lamp at an intensity of ~1000 μmol m−2 s−1.

Protein denaturation

To denature PixD, the protein was mixed with 8 M urea in 20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl and then incubated at room temperature for 24 hr. Flavin released from denatured PixD and urea was removed by chromatographic buffer exchange in 20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl using a Econo-Pac desalting column from Bio-Rad.

NMR experiments

All NMR experiments were performed at 30°C on Varian INOVA 600 MHz and coldprobe-equipped 800 MHz spectrometers. 15N/1H TROSY experiments were collected on uniformly 15N labeled samples with protein concentrations between 150 and 250 μM. To obtain NMR spectra of photoexcited PixD samples, we generated blue light from a 5 W Coherent Inova-90C argon laser running in single wavelength mode at 457 nm, directing the output from this laser into a quartz fiber optic inserted into the NMR sample. Power levels at the end of this fiber were 90 mW as measured before each experiment. 15N/1H TROSY spectra of the light state of PixD were recorded by preceding each transient in the NMR experiment with a 300 ms laser pulse during the recycle delay (total recycle delay duration ~1.1 s).

NMRPipe (35) was used for NMR data processing and NMRViewJ (36) for data display and analysis.

Crystallization, data collection and processing

PixD(Y8F) was crystallized using hanging drop method against buffer containing 0.1 M (NH4)2SO4, 0.1 M Bis-Tris pH 6.5, 20% PEG 3350 and 0.01 M spermidine at room temperature. The crystals were transferred to the crystallization buffer plus 15% ethylene glycol as cryoprotectant and then flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Diffraction data was collected on beamline 4.2.2 at ALS. Data was indexed and scaled using XDS (37). The structure of Y8F was solved by molecular replacement using Phaser (38) with wild type PixD monomer as searching model (PDB code: 2HFN; chain A). Six molecules were found in the asymmetric unit. After NCS averaging using ccp4 program DM (39), the map was good enough to allow us to adjust the model. Model building was performed in Coot (40). The structure was refined in Phenix.refine (41). P21 space group was used with a twin operator of (-h,-k, l) for the refinement. Pairwise root mean square deviation (RMSD) comparisons between all molecules of the PixD wild type (10 molecules) and Y8F mutant (6 molecules) was performed using the McLachlan algorithm (42) as implemented in the program Profit software (Martin, A.C.R., http://www.bioinf.org.uk/software/profit). Fits were made between the CA atoms of residues 8–140 among the wild type ensemble and the Y8F ensemble.

RESULTS

Trp91 remains solvent exposed in lit and dark states thus confirming a Tyr8-Gln50-Met93 ground state

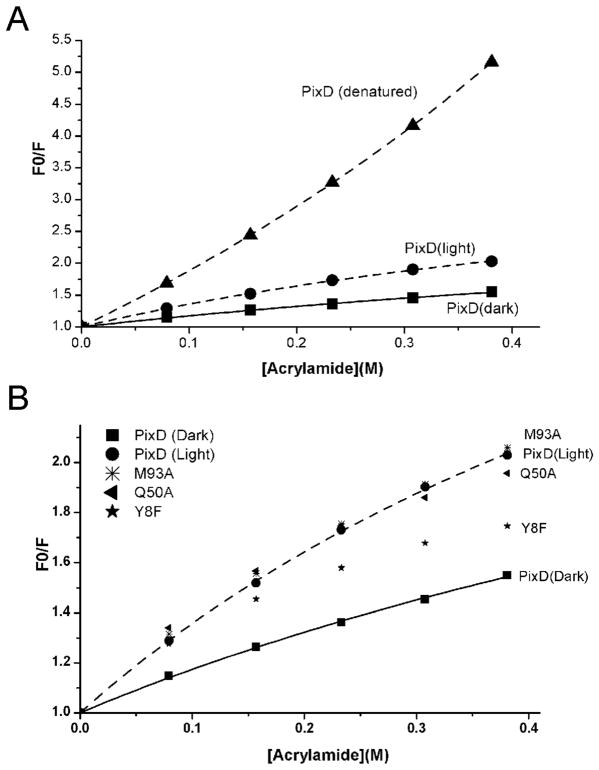

Recent mutational and spectroscopic studies on the BLUF domain of AppA demonstrated that homologs of Met93 and Trp91 do not swap positions upon light excitation (18). To determine if this is also the case for PixD, we analyzed Trp fluorescence in the presence of increasing amounts of acrylamide. PixD has only a single tryptophan, Trp91 located in the loop between β4 and β5 strands, thus recording Trp fluorescence emission intensity at 360 nm (excitation at 295 nm) in the presence (F) and absence (F0) of acrylamide, provides a measure of movement of this loop by probing for accessibility of Trp91 to collide with this quencher. As indicated in Fig. 2A, the observed F0/F acrylamide quenching plot with wild type denatured PixD has an upward curve which is contrasted to a downward curve observed with native folded PixD. An upward quenching plot can be assigned to static quenching which is a process where Trp is in contact with a quencher (acrylamide) at the time of light excitation (30). This is contrasted by a downward curve of native folded PixD that can be attributed to collisional (or dynamic) quenching, which is a process where light excited Trp must subsequently collide with the quencher before excitation energy transfer occurs.

Figure 2.

A: Acrylamide quenching of tryptophan fluorescence of PixD in its native and denatured states. F0 and F are the fluorescence intensity in the absence or presence of various concentrations of acrylamide, respectively. B: Acrylamide quenching of tryptophan fluorescence of PixD and its mutants (Y8F, Q50A and M93A). Only dark sate data are included for the mutants since light state data are essentially the same.

When fitting the curve for denatured PixD to Equation 1, both collisional and static quenching models can be dissected to give a Stern-Volmer constant (KSV) of 7.74 (± 0.16) M−1 and a static quenching constant (V) of 0.73 (±0.02) M−1. Note that if Equation 5 is used to fit the denatured PixD quenching curve, a similar KSV (7.64±0.02 M−1) is obtained with a faeff approaching ~100% (1.08±0.01), which indicates that denatured PixD contains a homogenous fluorophore. Inspection of the F0/F values in Fig. 2A also reveals that the quenching reaction is more efficient for denatured PixD over that of native PixD. This is because excitation energy transfer (quenching) is more efficient for static over collisional quenching. Illumination does not change the profile of the denatured PixD quenching curve.

In the case of native folded PixD that exhibits downward plots, only a heterogeneous fluorophore model can be fitted using Equation 5, suggesting that Trp91 is in at least two states. Using Equation 5 to fit a heterogeneous fluorophore for both dark- and light-adapted native PixD samples, we obtained KQeff = 2.73±0.20 M−1, faeff =0.69±0.03, and KQeff = 5.28±0.18 M−1, faeff=0.76±0.01, respectively. For native PixD, the quenching reaction happens more efficiently in the light-excited PixD relative to dark-adapted PixD as evidenced by the quenching curve of blue light adapted protein well above that of dark-adapted PixD (Fig. 2A). This can also be concluded from larger values of KQeff and faeff obtained from blue light excited over that of dark-adapted PixD. This result suggests that Trp91 is partially accessible to the quencher in the dark state and slightly more exposed to the quencher in the light excited state. As is the case of the recent acrylamide quenching study of the AppA BLUF domain (18), these PixD quenching results do not support large movement of Trp91 into a hydrophobic pocket that contains Gln50 and FAD that should be relatively inaccessible to the quencher (inaccessible Trp104 in AppA17–133 resulting in a horizontal quenching curve (18)). These results also suggest that the crystal structure where 9/10 PixD subunits have a hydrogen-bonded triad Tyr8-Gln50-Met93 (6) represents the true dark state of this photoreceptor.

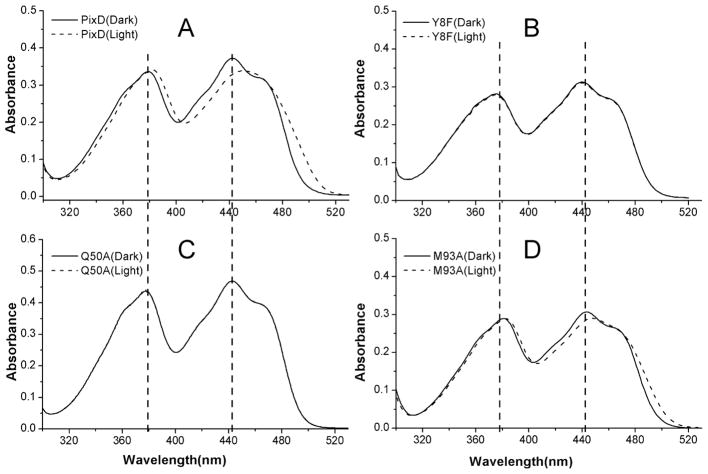

Tyr8 and Gln50 mutants are spectrally locked, while a Met93 mutant has a near normal photocycle

We addressed the role of the hydrogen bonded Tyr8-Gln50-Met93 triad by constructing substitution mutations at each of these positions. These PixD mutants were expressed, isolated and assayed for their ability to undertake a photocycle, as well as for their ability to interact with PixE to form a PixD10-PixE5 complex. As reported previously (4), illumination leads to a 10 nm red shift near 450 nm in the PixD visible absorbance spectrum (Fig. 3A), consistent with changes to the protein/flavin hydrogen bond network. Fig. 3B shows that mutating Tyr8 to Phe (Y8F) resulted in a loss of the photocycle coupled with a slight 2 to 3 nm blue shift of the absorption spectrum of the flavin relative to that observed with dark adapted wild type PixD. A Gln50 to Ala mutation (Q50A) also disrupted the photocycle and also has a normal dark absorption spectrum with peaks at 378 nm and 443 nm (Fig. 3C) as is observed with dark-adapted wild type PixD. These photocycle deficient mutants contrast with a Met93 to Ala (M93A) mutation at the final member of the triad that exhibits a reversible 10 nm spectral shift similar to that of wild type PixD (Fig. 3D). Analysis of the recovery rate shows that M93A exhibits a slightly faster decay to the ground state with a half time of 4.5±0.05 s. relative to 5.7±0.13 s observed with wild type PixD. In summary, Tyr8 or Gln50 mutations in the Tyr-Gln-Met triad completely eliminate the PixD photocycle while changing Met93 has only a minimal effect on the timing of the photocycle.

Figure 3.

UV-visible absorption spectra of PixD (A) and its mutants (Y8F [B], Q50A [C], and M93A [D]) in dark-adapted state (solid line) and light-adapted state (dashed line).

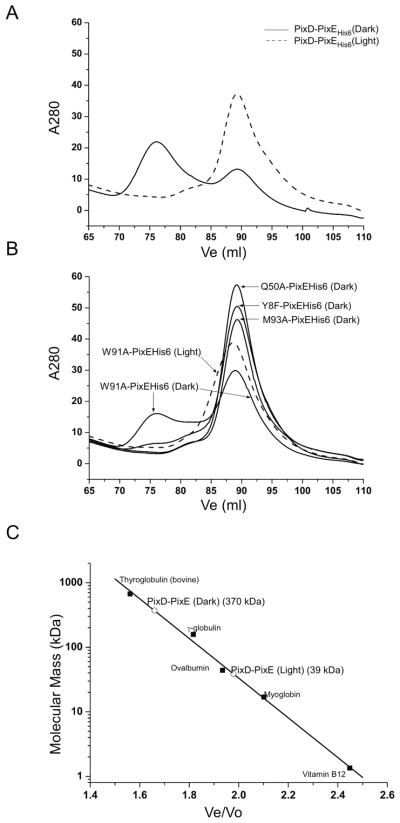

Mutations in the Tyr8-Gln50-Met93 triad lock the peptide into pseudo lit states

We recently demonstrated that addition of PixE promotes the assembly of PixD dimers into a PixD10-PixE5 supercomplex in the dark and that exposure to light dissociates the supercomplex back to PixE monomers and PixD dimers (25). We can therefore utilize the ability of PixE to promote formation of a PixD10-PixE5 supercomplex as a measure of whether PixD mutants mimic a dark or light induced signaling state (Fig. 4). For this analysis, 10–20 μM of wild type PixD, or various PixD mutants, were mixed with PixE at a molar ratio of ~2:1, incubated in the dark for at least two hours and then chromatographed through a Superose 6 gel filtration column under dark and light conditions. As shown in Fig. 4A and 4C, when wild type PixD and PixE are pre-incubated together and then chromatographed in the dark, there is a distinct peak at ~370 kDa (Ve=76 ml) representing the formation of the PixD10-PixE5 supercomplex as well as the presence of some unassembled PixD dimers and PixE monomers that co-elute at ~39 kDa (Ve=90 ml). In contrast, when the wild type PixD and PixE mixture are chromatographed in the light the PixD10-PixE5 supercomplex is absent, with only a single peak eluting at ~39 kDa. This result mimics our previous published study utilizing wild type PixD and PixE (25).

Figure 4.

Gel filtration profiles of PixD mixed with PixE His6. For Y8F, Q50A and M93A mixed with PixEHis6, only dark data are shown because the lit data are essentially the same. A: PixD-PixEHis6 mixture run in both dark and light conditions; B: Various PixD mutants-PixEHis6 mixture gel filtration profile. C: Size of the PixD:PixE complex in comparison with molecular weight standards.

We next assayed the Y8F and Q50A PixD mutants for their ability to participate in forming a PixD10-PixE5 supercomplex. As shown in Fig. 4B, both of these mutants were defective in associating with PixE in the dark. This result indicates that these mutants may mimic the lit state even though they exhibit dark state UV/visible absorbance spectra. This result is supported by acrylamide quenching data (Fig. 2B) that indicate that these mutants also exhibit a more Trp-exposed phenotype characteristic of light-adapted PixD. Similar analysis of PixD M93A mutant shows that this protein is also unable to form a complex with PixE (Fig. 4B), suggesting that this mutant is structurally exhibiting the lit state. This is surprising as the M93A mutant exhibits a near normal photocycle in regards to spectral shift and length of the photocycle, suggesting that this mutation interferes with transmission of structural changes from the chromophore through the rest of the protein rather than altering the photochemical step itself. Acrylamide quenching data (Fig. 2B) also indicate that this mutant constitutively exhibits a more Trp-exposed phenotype as is expected from a protein in a lit state even when assayed under dark conditions. Finally, we also undertook similar studies with the W91A mutant PixD that exhibits a normal 10 nm spectral shift and a significantly increased decay rate to the ground state (half-time of 0.62±0.04 s). The W91A mutant normally forms the PixD10-PixE5 supercomplex in the dark and dissociates out of this complex when illuminated, indicating that the W91A mutant is able to undergo a normal conformational change between dark and lit states (Fig. 4B). This contrasts with the M93A mutation that also retains a photocycle but lacks formation of a normal dark state structure that is needed for interaction with PixE.

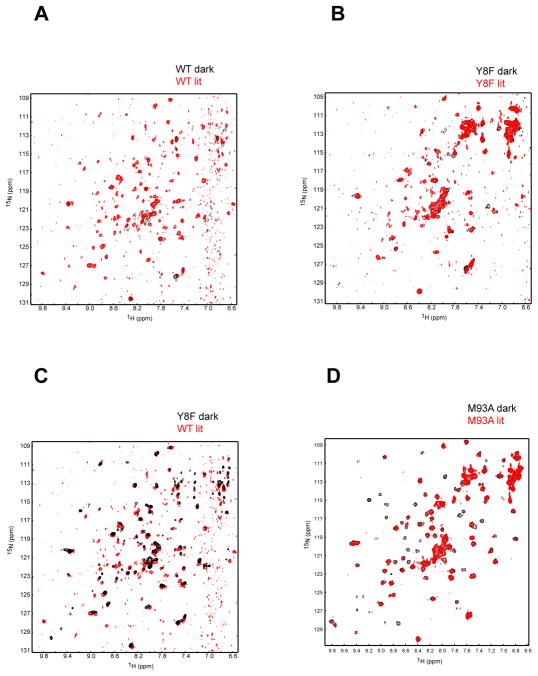

NMR and X-ray crystallography analyses indicate that Y8F is locked in a pseudo lit state

We utilized a combination of 15N/1H TROSY NMR spectroscopy and X-ray crystallization analyses to probe the structure of the Y8F and M93A mutants. Based on differences in signal intensity for 2D 15N/1H TROSY spectra, the NMR data are consistent with wild type PixD existing as larger oligomer than the Y8F mutant at the analyzed concentrations of 150–250 μM (Fig. 5). Wild type PixD exhibits numerous changes in peak intensity and location between lit and dark states, as expected from light dependent changes in the peptide backbone as well as changes in the oligomerization state (Fig. 5A). The latter is particularly evident by the increased number of peaks observed upon illumination. In contrast, analysis of spectra of dark and lit Y8F samples show much fewer spectral changes, with no apparent light-dependent breakage of its oligomeric state thereby confirming that this protein is photochemically inactive (Fig. 5B). Comparison of the lit wild type 15N/1H TROSY spectra against the dark Y8F spectra (Fig. 5C) indicates that most Y8F peaks are aligned with lit wild type peaks. There are also a few peaks in the lit wild type spectra that are not present in the dark Y8F spectra indicating that Y8F is in a “pseudo” lit state rather than in true wild type lit state. We show by crystallographic analysis below that these incongruences likely represent differences in oligomerization.

Figure 5.

15N/1H TROSY spectra of PixD under dark (black) and lit (red) conditions. Overlays are shown for WT (A), Y8F (B) and M93A (D) PixD proteins as indicated. Comparison between WT lit and Y8F dark as in (C)

Similar 2D 15N/1H TROSY spectral analysis of the M93A mutant is quite different (Fig. 5D). This spectrum yields a large number of well-resolved 15N/1H TROSY peaks with significantly higher intensity than observed with wild type and Y8F samples. This is consistent with a symmetric complex that we presume to be dimeric from gel filtration data (Fig. 4). The oligomeric state does not change with light-excitation indicating that this mutant is defective in forming the larger oligomeric structures as observed in the Y8F and wild type PixD spectra. While illumination does not cause significant chemical shift changes, we note that it instead causes a significant drop in signal intensity for some of the peaks as previously observed for the BlrB BLUF domain, likely due to intermediate timescale exchange broadening effects (28). These data indicate that this protein does indeed undergo a light-dependent conformational change that is likely restricted to increased motion and structural changes in the vicinity surrounding the flavin chromophore (as indicated by the wild type visible absorbance spectral characteristics).

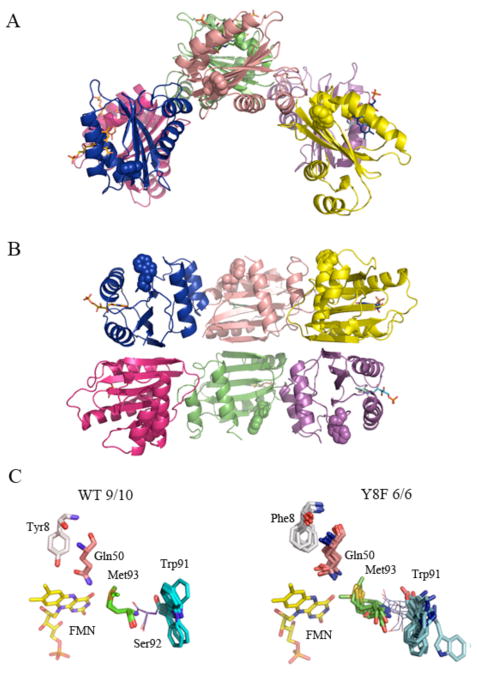

After many trials to crystallize all of the studied PixD mutants, Y8F mutant was the only one providing diffraction quality crystals and we were successful in solving its structure (refinement parameters are presented in Table 1). The Y8F asymmetric unit contains only 6 subunits arranged in a double-stacked semi-circle (Fig. 6A, B), unlike the wild type PixD that has 10 molecules arranged as a double-stacked pentameric ring observed from two different crystallization conditions (Fig. 1C).

Table 1.

Summary of crystallography statistics (PDB entry: 3MZI)

| Data Collection | |

| Space group | P1211 |

| Cell dimensions | |

| a,b,c (Å) | 41.85 119.48 93.26 |

| α,β, γ(°) | 90 102.89 90 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.240 |

| Resolution range (Å) a | 49.9–2.30 (2.4–2.3) |

| <I>/<σI> | 11.56 (3.13) |

| Completeness | 97.3(89.4) |

| Rsymb | 0.081(0.332) |

| Redundancy | 3.7 |

| Refinement | |

| Number of reflections | 91822 |

| Unique reflections | 24879 |

| Rwork/ Rfree | 0.165/0.216 |

| R.m.s. deviations | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.007 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.241 |

Values in parenthesis are for the highest resolution shell

Rsym= Σ(|I-<I>|)/Σ (I)

Figure 6.

Crystal structure of the PixD Y8F mutant.. A: Asymmetric unit of Y8F crystal (top view) B: side view. Trp91 side chains are represented as spheres. C: Superposition of Tyr8, Gln 50, Trp91 and Met93 in 9/10 subunits of wild type PixD and of Phe8, Gln50, Trp91 and Met93 in 6 molecules of the Y8F structure. Superposition was performed using Cα of residues 5–140; only amino acids of interest are shown. The FMN molecule was not included in the alignment; however, its position in one molecule is shown for better orientation.

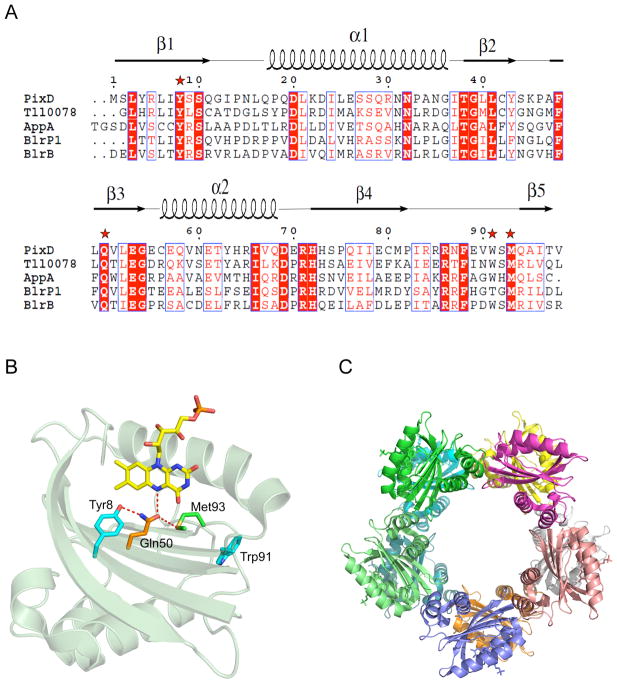

Figure 1.

A) Alignment of BLUF domains with known 3D structures (7–10, 46). Conserved amino acids are shown with red backgrounds, semi-conserved ones in red letters. Stars indicate residues important in BLUF domain photochemistry and are pictured in B. B) PixD monomer and amino acids (and their H-bonds) critical in the photochemistry. The α1 helix has been removed for clarity. C) The wild type PixD decamer crystal structure (6, PDB code: 2HFN).

A ribbon diagram of the structure of Y8F (Fig. 6A and B) shows the arrangement of 6 monomers in the semi-circle. As observed in wild-type PixD, this arrangement involves interactions between PixD monomers across two types of dimeric interfaces. An AB dimer is designated as a pair that contains one monomer from the top and one from the bottom ring (for example the blue and dark pink monomers in Fig. 6B), while an AC dimer is designated as a pair comprised of interacting PixD in one ring (for example blue and salmon monomers or dark pink and green monomers in Fig. 6B). We assessed which dimer pair has more contact area by performing contact analysis using the Protein Interfaces, Surfaces and Assemblies (PISA) server (43). The average area excluded in an AB dimer is 644 A2, while an AC dimer average excludes 493 A2. The Complexation Significance Score (CSS) suggested by PISA for the AB dimer is 0.47 while for the AC dimer is zero (a higher score indicates an interface necessary for complexation). Taken together, these data suggest that the AB interface will be more stable than the AC version.

Inspection of the Tyr8-Gln50-Met93 triad in the 9 wild type PixD subunits that has Trp91 exposed shows that each of these hydrogen bonded residues are remarkably fixed compared to Trp91 that shows some variability (Fig. 6C) Similar analysis of the 6 Y8F subunits show that the Phe8-Gln50-Met93 triad is much more variable. Movement of Phe8 is not unexpected as this substitution would result in loss of the hydrogen bond interaction that exists between Tyr8 and Gln50 in wild type PixD. Interestingly, inspection of the distance between Met93 and Gln50 in individual Y8F subunits shows distances ranging between 2.7 to 4.4 Å (as measured between Met93 Sγ and Q50 Nε) that is contrasted by a more narrow 3.2 to 3.4 Å range that occurs between these residues in the 9/10 subunits of wild type PixD. These distance variations, coupled with variable positions (Fig. 6C), suggest that that the Phe substitution at Trp8 also likely leads the loss of a hydrogen bond between Gln50 and Met93. Another interesting observation is that Trp91 samples variable positions in the Y8F subunits with a ~180º flip to different “out” conformations. This may correspond to the increase in acrylamide quenching observed with the Y8F mutant over that of dark adapted wild type PixD (Fig. 2B).

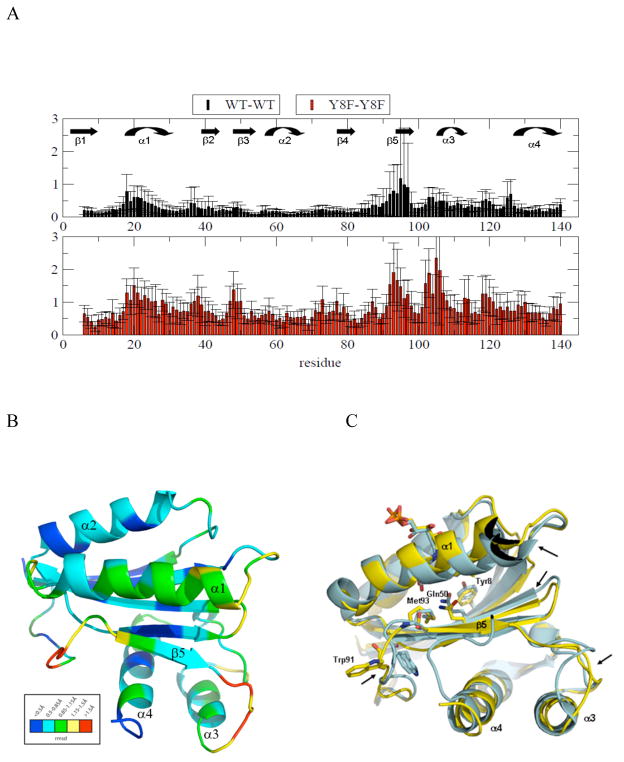

In addition to variability of Met93, we analyzed the variability of the backbone structure by undertaking comparative pair-wise Cα RMSD analyses of wild type PixD (10 molecules in the asymmetric unit, ref 6) and the Y8F mutant (6 molecule ensemble, vide infra). As observed in Fig. 7, the RMSD values among the wild type ensemble are generally lower than those of the Y8F ensemble. Note that Y8F structure also has higher overall B factor (91.9 Å2 @ 2.3 Å resolution) than that of wild type structure (39.4 Å2 @ 1.9 Å resolution). The larger RMSD within Y8F ensemble and higher B factor suggests that Y8F structure presents more flexibility that is consistent to the acrylamide quenching data suggesting Y8F adopts heterogeneous pseudo-lit conformation. Both wild type and Y8F proteins exhibit similar groupings of residues with low/high RMSD values, although the Y8F backbone has additional regions with high RMSD between residues 100 and 120 that are plotted in the Y8F structure as red/yellow in Fig. 7B. The variable regions are all adjacent to each other, suggestive of concerted movements. Regions of variability are primarily localized to the C-terminal half of the BLUF domain (residues 91–130), including β5, α3, α4 and the loops between them. Additional variability is also observed at α1 and to a lesser extent at β2, β3 and β4. Fig. 7C represents an alignment of molecule A between PixD WT and Y8F mutant structures. Visual inspection of both structures show that several areas of differences in the backbone occur (designated with arrows) corresponding to regions of high flexibility as shown in the heat map in Fig. 7B.

Figure 7.

A: RMSD graph for Cα atoms in an ensemble of PixD WT and PixD Y8F. RMSDs represent the average values with standard deviation among the monomers. B) RMSD deviations in PixD Y8F are heat-mapped to its 3D structure. C) Comparison of PixD Y8F structure (yellow) to PixD WT BLUF domain (blue). Areas or biggest differences observed by visual inspection are pointed out by arrows.

DISCUSSION

Several early studies using NMR, fluorescence and absorption spectroscopy predicted that Trp91 (or Trp104 in AppA) was likely buried in the hydrophobic FAD binding pocket (6, 9, 13, 17, 19, 44). However recent acrylamide quenching studies indicated that a Trp91 homolog in the native AppA is not located near the flavin in the dark state and that light excitation only promoted minimal movement of this aromatic residue (18). Similar acrylamide quenching analysis of tryptophan in this study with PixD also indicates that Trp91 is partially solvent exposed under dark condition with a slight increase in exposure under lit condition. Thus, the PixD dark state also likely contains the hydrogen bonded triad of Tyr8-Gln50-Met93 that is present in 9 of 10 subunits of the PixD crystal structure where Gln50 is also hydrogen bonded to N5 of the flavin ring (6). The observed slight increase in quenching of Trp91 by acrylamide under lit conditions is consistent with the observed increase in flexibility of the β4 and β5 connecting loop that contains Trp91 upon light exposure. Comparison of Trp91 in the wild type and Y8F crystal structures (Fig. 6C) also shows that this residue seems to sample more conformations in Y8F in comparison with two main orientations in wild type PixD dark state. This could explain why the Y8F acrylamide quenching curve is between the dark and lit state quenching curves of wild type PixD. Finally, the downward curve of acrylamide quenching observed with wild type PixD in the dark state can be explained by the presence of two main conformations of Trp91 under this condition. Dynamic sampling of different conformations by Trp91 could present a strategy for a ready response to even small perturbations of nearby H-bonds (Fig. 1B), either by mutation, or light-induced electron/proton transfer. Finally, mutating Trp91 itself does not affect the output signal as measured by PixD interaction with PixE but it does affect rate of the photocycle (6). This result is consistent with the likely location of Trp91 away from the Tyr8-Gln50-Met93 hydrogen bond network with the flavin yet located at the start of the β5 strand that is flexible and variable in length. Thus a mutation in Trp91 likely influences the dynamics of this region and ultimately the return to the dark ground state.

Tyr8 is thought to initiate the BLUF photocycle through donation of an electron and proton to the light excited flavin (11, 19). This is thought to be followed by either rotation (9, 11, 13) or tautomerization of Gln50 (16, 21), resulting in the formation of a new hydrogen bond to O4 of the flavin that leads to a 10 nm spectral shift (20, 45). Our observation that mutations of Tyr8 and Gln50 do not exhibit a photocycle, while an Ala substitution of Met93 does lead to a productive photocycle, suggests that Met93 is not a key residue for the primary photochemistry. This is not the case for the output signal as an Ala substitution of Met93 does lead to a loss of PixD interactions with PixE. Met93, which is conserved among BLUF proteins, must therefore be considered a key residue in propagating the output light signal. This role of Met93 is also reflected in a report that M93A substitution does not undergo similar light-induced conformation change of the peptide as does wild type PixD (26). Met93 is strategically located at a junction of the β4 and β5 loop that increases flexibility upon light excitation (Fig. 7C). Presumably, light excitation of the flavin disrupts the hydrogen bond that holds Gln50 to Met93 thereby allowing this loop to become “untethered” and subsequently move. This conclusion is also supported by our Trp quenching study that shows dark-adapted M93A mutant having an identical amount of quenching as lit wild type PixD (Fig. 2b). The loop that is “tethered” by Met93 contains Trp91 so the Met93 to Ala mutant should exhibit increased flexibility of this loop even under dark conditions, which is indeed the case. Finally, analysis of the crystal structure of the pseudo lit state Y8F mutant shows that Met93 exhibits significant variability from one subunit to another in its distance from Gln50 (Fig. 6C). This also suggests that Met93 is likely untethered to Gln50 in the Y8F mutant.

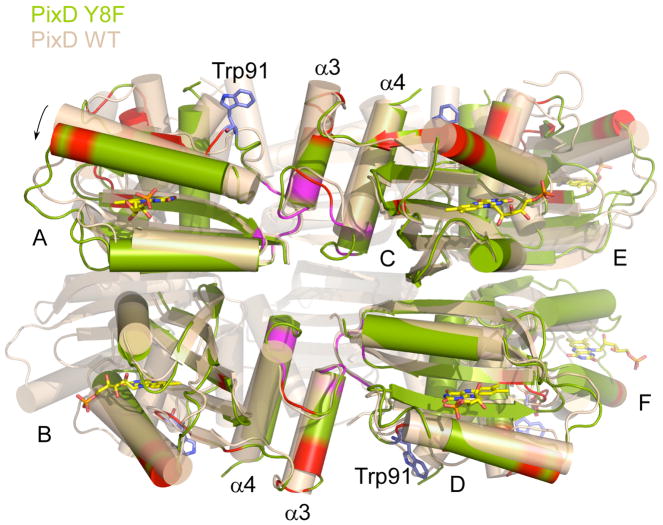

The asymmetry unit of Y8F crystal contains a hexamer with subunits arranged in a double half circle (Fig. 6) instead of a decamer comprised of two complete stacked circles as observed in wild type PixD (6). An interesting interacting region between sets of AB dimer pairs involves an interaction between α3 from one AB pair with the β4 and β5 flexible loop in a neighboring AB pair (Fig. 8). The β4 and β5 loop contains both Trp91 and Met93, and as discussed above, is known to undergo increased dynamic motion upon light excitation (Fig. 7). Note that all these interaction faces are also present in the wild type PixD dimer, which has a full ring comprised of 5 AB dimers instead of the open ring comprised of 3 AB dimers in Y8F. Even though one cannot rule out the possibility of crystallization condition affecting the packing form, considering the fact that wild type PixD adopts the same decamer conformation from two different crystallization conditions and cannot crystallize in the same condition of Y8F, the difference of Y8F oligomerization state seen in the structure is likely biologically relevant. One significant difference in the Y8F structure is that neighboring AB dimers are somewhat tilted away from the center of the half circle relative to neighboring pairs observed in the wild type structure (Fig.8). Thus, if additional Y8F dimers were added to complete a circular structure then the two ends would not align. An intriguing possibility is that this difference indicates that light illumination of wild type PixD could disrupt the higher oligomer of PixD by inducing a twist to the full circle that causes disruption of the pentameric arrangement. RMSD analysis of the Y8F structure also reveals changes in the β3 strand that contains Gln50 from where the light signal is propagated. Major changes are also present around β5 strand and α3 helix with the loop between α3 and α4 increasing flexibility. Interestingly, the loop connecting β4 to β5 in one AB dimer interacts with the α3 helix of a neighboring dimer (Fig. 8), suggesting that these regions may push against each other upon light excitation thereby inducing a twist that disrupts the interaction between neighboring AB dimer pairs leading to disassembly of the PixD decamer.

Figure 8.

Superposition of Y8F structure (green) on PixD WT structure (wheat). Chain C and D of Y8F were superposed on Ca atoms of WT structure. A tilt away from the circle center was observed on Y8F AB dimer or EF dimer (indicated by an arrow). The interface between AB dimer and CD dimer is highlighted in magenta. Residues with RMSDs > 1.25 among Y8F monomers are in red. Trp91 shown in blue sticks indicates the position of the loop between β4 and β5 strands.

Recently, light-excited structural changes were also reported for the BLUF domain of Klebsiella pneumoniae BlrP1, a light-dependent c-di-GMP hydrolase. This BLUF domain also possesses C-terminal a3 and a4 output helices akin to those observed in PixD (27, 46). Illumination led to significant changes in the position and intensity of NMR signals in residues within the β4-β5 loop, β5 strand and in the loop between the a3-a4 helices (27). When viewed in the context of the dark state crystal structure of full-length BlrP1 (46), these light induced structural changes of the BLUF domain appear to be integral to regulating the catalytic EAL domain. We find it interesting that the changes observed in BlrP1 closely match the major changes observed in the crystal structure of the PixD Y8F mutant suggesting that an output signal involving alteration of the flexibility of the β4-β5 loop and its propagation through the β5 strand to the a3-a4 helices may be a common output signal among BLUF domains.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants GM40941 to C. E. B. and Robert A. Welch Foundation grant I-1424 to K.H.G.

Abbreviations

- BLUF

blue-light sensing using FAD

References

- 1.Gomelsky M, Kaplan S. appA, a novel gene encoding a trans-acting factor involved in the regulation of photosynthesis gene expression in Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4609–4618. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.16.4609-4618.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gomelsky M, Klug G. BLUF: a novel FAD-binding domain involved in sensory transduction in microorganisms. Trends Biochem Sci. 2002;27:497–500. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)02181-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Masuda S, Bauer CE. AppA is a blue light photoreceptor that antirepresses photosynthesis gene expression in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Cell. 2002;110:613–623. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00876-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Masuda S, Hasegawa K, Ishii A, Ono TA. Light-induced structural changes in a putative blue-light receptor with a novel FAD binding Fold sensor of blue-light U\using FAD (BLUF); Slr1694 of Synechocystis sp. PCC6803. Biochemistry. 2004;43:5304–5313. doi: 10.1021/bi049836v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Masuda S, Ono TA. Biochemical characterization of the major adenylyl cyclase, Cya1, in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. FEBS Lett. 2004;577:255–258. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.09.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yuan H, Anderson S, Masuda S, Dragnea V, Moffat K, Bauer C. Crystal structures of the Synechocystis photoreceptor Slr1694 reveal distinct structural states related to signaling. Biochemistry. 2006;45:12687–12694. doi: 10.1021/bi061435n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kita A, Okajima K, Morimoto Y, Ikeuchi M, Miki K. Structure of a cyanobacterial BLUF protein, Tll0078, containing a novel FAD-binding blue light sensor domain. J Mol Biol. 2005;349:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.03.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jung A, Domratcheva T, Tarutina M, Wu Q, Ko WH, Shoeman RL, Gomelsky M, Gardner KH, Schlichting I. Structure of a bacterial BLUF photoreceptor: insights into blue light-mediated signal transduction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:12350–12355. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500722102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson S, Dragnea V, Masuda S, Ybe J, Moffat K, Bauer C. Structure of a novel photoreceptor, the BLUF domain of AppA from Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Biochemistry. 2005;44:7998–8005. doi: 10.1021/bi0502691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jung A, Reinstein J, Domratcheva T, Shoeman RL, Schlichting I. Crystal structures of the AppA BLUF domain photoreceptor provide insights into blue light-mediated signal transduction. J Mol Biol. 2006;362:717–732. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gauden M, van Stokkum IH, Key JM, Luhrs D, van Grondelle R, Hegemann P, Kennis JT. Hydrogen-bond switching through a radical pair mechanism in a flavin-binding photoreceptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:10895–10900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600720103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Unno M, Masuda S, Ono TA, Yamauchi S. Orientation of a key glutamine residue in the BLUF domain from AppA revealed by mutagenesis, spectroscopy, and quantum chemical calculations. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:5638–5639. doi: 10.1021/ja060633z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grinstead JS, Avila-Perez M, Hellingwerf KJ, Boelens R, Kaptein R. Light-induced flipping of a conserved glutamine sidechain and its orientation in the AppA BLUF domain. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:15066–15067. doi: 10.1021/ja0660103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonetti C, Mathes T, van Stokkum IH, Mullen KM, Groot ML, van Grondelle R, Hegemann P, Kennis JT. Hydrogen bond switching among flavin and amino acid side chains in the BLUF photoreceptor observed by ultrafast infrared spectroscopy. Biophys J. 2008;95:4790–4802. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.139246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iwata T, Watanabe A, Iseki M, Watanabe M, Kandori H. Strong donation of the hydrogen bond of tyrosine during photoactivation of the BLUF domain. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters. 2011;2:1015–1019. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Domratcheva T, Grigorenko BL, Schlichting I, Nemukhin AV. Molecular models predict light-induced glutamine tautomerization in BLUF photoreceptors. Biophys J. 2008;94:3872–3879. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.124172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toh KC, van Stokkum IH, Hendriks J, Alexandre MT, Arents JC, Perez MA, van Grondelle R, Hellingwerf KJ, Kennis JT. On the signaling mechanism and the absence of photoreversibility in the AppA BLUF domain. Biophys J. 2008;95:312–321. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.117788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dragnea V, Arunkumar AI, Yuan H, Giedroc DP, Bauer CE. Spectroscopic studies of the AppA BLUF domain from Rhodobacter sphaeroides: addressing movement of tryptophan 104 in the signaling state. Biochemistry. 2009;48:9969–9979. doi: 10.1021/bi9009067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dragnea V, Waegele M, Balascuta S, Bauer C, Dragnea B. Time-resolved spectroscopic studies of the AppA blue-light receptor BLUF domain from Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Biochemistry. 2005;44:15978–15985. doi: 10.1021/bi050839x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Masuda S, Hasegawa K, Ono TA. Light-induced structural changes of apoprotein and chromophore in the sensor of blue light using FAD (BLUF) domain of AppA for a signaling state. Biochemistry. 2005;44:1215–1224. doi: 10.1021/bi047876t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sadeghian K, Bocola M, Schutz M. A conclusive mechanism of the photoinduced reaction cascade in blue light using flavin photoreceptors. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:12501–12513. doi: 10.1021/ja803726a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Obanayama K, Kobayashi H, Fukushima K, Sakurai M. Structures of the chromophore binding sites in BLUF domains as studied by molecular dynamics and quantum chemical calculations. Photochem Photobiol. 2008;84:1003–1010. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2008.00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okajima K, Yoshihara S, Fukushima Y, Geng X, Katayama M, Higashi S, Watanabe M, Sato S, Tabata S, Shibata Y, Itoh S, Ikeuchi M. Biochemical and functional characterization of BLUF-type flavin-binding proteins of two species of cyanobacteria. J Biochem (Tokyo) 2005;137:741–750. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvi089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaneko T, Sato S, Kotani H, Tanaka A, Asamizu E, Nakamura Y, Miyajima N, Hirosawa M, Sugiura M, Sasamoto S, Kimura T, Hosouchi T, Matsuno A, Muraki A, Nakazaki N, Naruo K, Okumura S, Shimpo S, Takeuchi C, Wada T, Watanabe A, Yamada M, Yasuda M, Tabata S. Sequence analysis of the genome of the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803. II. Sequence determination of the entire genome and assignment of potential protein-coding regions. DNA Res. 1996;3:109–136. doi: 10.1093/dnares/3.3.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yuan H, Bauer CE. PixE promotes dark oligomerization of the BLUF photoreceptor PixD. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:11715–11719. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802149105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tanaka K, Nakasone Y, Okajima K, Ikeuchi M, Tokutomi S, Terazima M. Light-induced conformational change and transient dissociation reaction of the BLUF photoreceptor Synechocystis PixD (Slr1694) J Mol Biol. 2011;409:773–785. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu Q, Gardner KH. Structure and insight into blue light-induced changes in the BlrP1 BLUF domain. Biochemistry. 2009;48:2620–2629. doi: 10.1021/bi802237r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu Q, Ko WH, Gardner KH. Structural requirements for key residues and auxiliary portions of a BLUF domain. Biochemistry. 2008;47:10271–10280. doi: 10.1021/bi8011687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hasegawa K, Masuda S, Ono TA. Spectroscopic analysis of the dark relaxation process of a photocycle in a sensor of blue light using FAD (BLUF) protein Slr1694 of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC6803. Plant Cell Physiol. 2005;46:136–146. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pci003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eftink MR, Ghiron CA. Exposure of tryptophanyl residues in proteins - quantitative-determination by fluorescence quenching studies. Biochemistry. 1976;15:672–680. doi: 10.1021/bi00648a035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prieto ACaM. Ribonuclease T1 and alchohol dehydrogenase fluorescence quenchign by acrylamide. J Chem Education. 1993;70:425. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ghlron MREaCA. Fluorescence quenching of indole and model micelle systems. J Phys Chem. 1976;80:486–493. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stern O, Volmer M. On the quenching time of fluorescence. Phys Z. 1919;20:183–188. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lehrer SS. Solute perturbation of protein fluorescence. The quenching of the tryptophyl fluorescence of model compounds and of lysozyme by iodide ion. Biochemistry. 1971;10:3254–3263. doi: 10.1021/bi00793a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson BA, Blevins RA. Nmr View - a Computer-Program for the Visualization and Analysis of Nmr Data. J Biomolec Nmr. 1994;4:603–614. doi: 10.1007/BF00404272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kabsch W. Automatic Processing of Rotation Diffraction Data from Crystals of Initially Unknown Symmetry and Cell Constants. J Appl Crystallogr. 1993;26:795–800. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mccoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cowtan K. Joint CCP4 and ESF-EACBM Newsletter on Protein. Crystallography. 1994:34–38. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adams PD, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Hung LW, Ioerger TR, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Read RJ, Sacchettini JC, Sauter NK, Terwilliger TC. PHENIX: building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D. 2002;58:1948–1954. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902016657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mclachlan AD. Rapid Comparison of Protein Structures. Acta Crystallogr A. 1982;38:871–873. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krissinel E, Henrick K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J Mol Biol. 2007;372:774–797. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gauden M, Grinstead JS, Laan W, Stokkum IH, Avila-Perez M, Toh KC, Boelens R, Kaptein R, Grondelle RV, Hellingwerf KJ, Kennis JT. On the role of aromatic side chains in the photoactivation of BLUF domains. Biochemistry. 2007;46:7405–7415. doi: 10.1021/bi7006433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Masuda S, Hasegawa K, Ono TA. Adenosine diphosphate moiety does not participate in structural changes for the signaling state in the sensor of blue-light using FAD domain of AppA. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:4329–4332. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.06.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barends TR, Hartmann E, Griese JJ, Beitlich T, Kirienko NV, Ryjenkov DA, Reinstein J, Shoeman RL, Gomelsky M, Schlichting I. Structure and mechanism of a bacterial light-regulated cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase. Nature. 2009;459:1015–1018. doi: 10.1038/nature07966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]