Abstract

Objectives

Alcohol consumption is a known risk factor for traumatic injuries of all types and has been shown to produce detrimental effects on bone metabolism. While the mechanisms responsible for these detrimental effects are not well characterized, oxidative stress from alcohol exposure appears to play a central role. This study was designed to examine the effect of a short-term binge alcohol consumption pattern on fracture repair and the effect of an antioxidant, N-acetylcysteine, on fracture healing following binge alcohol consumption.

Methods

One hundred forty-four (144) adult male Sprague Dawley rats underwent unilateral closed femur fracture after injection of either saline or alcohol to simulate a binge alcohol cycle. Animals in the antioxidant treatment group received daily N-acetylcysteine following fracture. Femurs were harvested at 1, 2, 4 and 6 weeks following injury and underwent biomechanical testing and histological analysis.

Results

Binge alcohol administration was associated with significant decreases in biomechanical strength at one and two-week time points with a trend toward decreased strength at four and six-week time points as well. Alcohol-treated animals had less cartilage component within the fracture callus and healed primarily by intramembranous ossification. Administration of N-acetylcysteine in alcohol-treated animals improved biomechanical strength to levels comparable to the control animals and was associated with increased endochondral ossification.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that binge alcohol alters the quality of fracture healing following a traumatic injury and that concurrent administration of an antioxidant is able to reverse these effects.

Keywords: Fracture, binge alcohol, antioxidant, Canonical Wnt pathway

INTRODUCTION

Alcohol intoxication increases the risk of traumatic injury 1,2 with 25–35% of non-fatal injuries associated with alcohol use 3. Low energy injuries such as hip fractures can also be associated with alcohol use 4. Motor vehicle accidents that result from alcohol use cost the American public an estimated $114.3 billion annually 5. The pattern of alcohol consumption most often associated with traumatic injury is binge-drinking 6. Patients who abuse alcohol are at higher risk for complications following fracture including non-union 7. In rodents, alcohol exposure is associated with impaired osteoinduction and impaired healing of surgically induced fractures 8,9, decreases in bone mineral density, biomechanical strength 10, 11 and decreased serum levels of osteocalcin12.

The canonical Wnt signaling pathway plays a pivotal role in both the maintenance of bone mass and normal fracture repair 13, 14. Our laboratory has shown that alcohol exposure decreases the expression of several key genes associated with the canonical pathway and its downstream transcriptional targets15, however the mechanism(s) underlying this effect are not currently known. One possible mechanism may be related to alcohol-induced oxidative stress. Studies have shown that binge alcohol exposure induces the formation of reactive oxygen species through several mechanisms 16, and accumulation of oxygen radicals has been shown to down-regulate canonical Wnt pathway activity 17, 18. Recent clinical studies found that post-menopausal women with osteoporosis demonstrated lower levels of antioxidant enzymes and higher levels of plasma malondialdehyde, a biomarker for oxidative stress 19. Taken together, these findings suggest that alcohol-induced deficient fracture repair may be caused by an increased state of systemic oxidative stress inhibiting Wnt signaling activity required for normal bone healing.

Based on this information, we developed a novel rodent model of acute binge alcohol exposure followed by traumatic orthopaedic injury to test the hypothesis that alcohol-induced inhibition of bone fracture healing was related in part, to increased systemic oxidative stress. N-acetylcysteine (NAC) is a commonly studied and clinically used antioxidant 20, shown to have protective effects on pulmonary function in rats following femur fracture and to reduce oxidative stress in rats exposed to chronic alcohol 21, 22. To our knowledge, there have been no studies examining the effect of binge alcohol consumption on the healing of bone fracture injuries or the effect of anti-oxidant therapy on the repair process. We show evidence here that exposure to alcohol prior to orthopaedic trauma reduces fracture callus bridging strength and inhibits normal endochondral bone formation in the callus, while NAC treatment produces a beneficial effect on fracture callus strength and bone deposition compromised by prior alcohol exposure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Binge Alcohol Treatment Paradigm

This investigation received approval from the Loyola University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Adult male Sprague Dawley rats obtained at 16 weeks of age were randomly assigned to one of three treatment groups: Injury only (I), injury with binge alcohol exposure (IA), or injury with binge alcohol exposure and N-acetylcysteine treatment (IAN). Ten animals per group were utilized, based on a power analysis performed using preliminary fracture callus biomechanical strength data (not shown). Alcohol was administered by a single daily intraperitoneal (IP) injection of a 20% (vol./vol.) ethanol/saline solution at a dose of 3 g/kg, chosen to achieve peak blood alcohol levels (BAL) of approximately 300 mg/dl23, and a BAL of 200 mg/dl at the time of injury. Control animals were given an IP injection of an equal volume of sterile isotonic saline at the time of alcohol group injections. Alcohol or saline injections were given starting at 9:00 AM, 3 consecutive days per week for a total of 2 weeks. No IP injections were given during the intervening 4 days between binge cycles.

Surgical Procedure

One hour after the last alcohol or saline injection, animals were anesthetized (ketamine: 90 mg/kg, xylazine: 10 mg/kg/IP), prepped for surgery, and given gentamicin (5 mg/kg/SC). An anterior incision was made over the left knee and a medial parapatellar approach to the distal femur was performed with the patella dislocated laterally. A 1.25mm Kirschner wire (Synthes; West Chester, PA) was passed retrograde the length of the femoral canal to the level of the greater trochanter, and the distal end was cut flush with the femoral condyles. The patella was reduced, and the extensor mechanism and the skin were repaired with interrupted 4-0 Vicryl suture. Unilateral closed femur fractures were created using a blunt three-point guillotine device 24 consisting of a platform of 2 pins placed approximately 15 mm apart and a blunt point attached to a sliding rod aligned to drop between the 2 pins. The excursion of the sliding blunt device was adjusted to 5mm. The device was driven by dropping a 550-gram weight from a height of 20 centimeters. Following injury, animals were resuscitated with 5cc warmed normal saline IP and returned to home cages. Buprenorphine (0.02 mg/kg/SC/q8) was administered for pain control for the first 24 hours post-operatively and every 8 hours thereafter as required.

Post-operative Protocol

On post-operative day 1, animals in the IAN groups received N-acetylcysteine (400 mg/kg/IP), and animals in the remaining groups received 5cc sterile saline IP. Animals in IAN groups received N-acetylcysteine (10 mg/kg) by intraperitoneal injection daily five days per week for 1 week (1 week group) or 2 weeks (2, 4, and 6 week groups) starting on post-operative day 2; control animals received matched volume saline IP. At 1, 2, 4, and 6 weeks post-injury, animals were euthanized and both femurs were harvested through a lateral approach with the contralateral femur of Group I used as an uninjured control. Femurs were stored at −20° C for biomechanical testing or fixed in 10% formalin for histological analysis.

Biomechanical Testing

Femoral heads were removed to allow for better placement within the testing device and the intramedullary Kirschner wire was removed. Biomechanical testing was carried out using a four-point bending device. Biomechanical analysis was carried out using an Instron biomaterials testing device (Model 5544, Norwood, MA), with the testing protocol consisting of a constant extension of 0.5mm/min to produce a compressive force across the fracture callus. Fracture callus biomechanical failure was defined as a drop of 20% or greater in the amount of compressive force supported by the callus. Femurs were visually inspected at the time of testing to ensure material failure.

Histological Analysis

Fixed callus specimens were decalcified in 4% formic acid solution (Cal-Ex II fixative/decalcifier; Fisher Scientific; Pittsburgh, PA) for 14 days, embedded in paraffin, sectioned along the longitudinal axis of the femoral shaft and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Callus histology was visualized using a Leica MZ Apo Stereomicroscope (Leica Inc., Bannockburn, IL) and images were captured using a Nikon D80 digital camera system.

Statistical Analysis

For each outcome parameter, groups were compared at each time point using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey post-hoc test. Significance was considered for p≤0.05.

RESULTS

Fracture Callus Biomechanics

One-Week Group

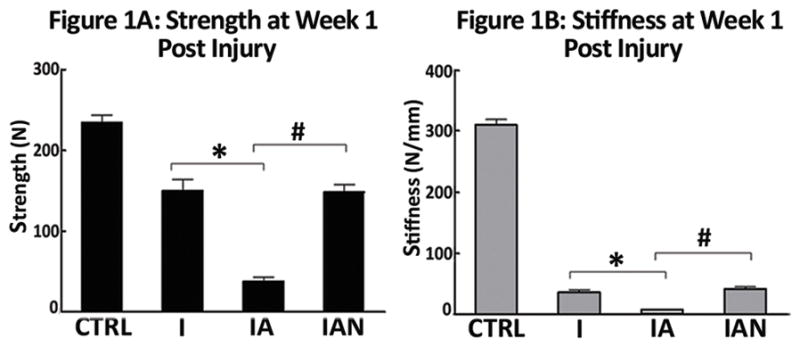

Binge alcohol exposure had a significant effect on fracture callus strength at one week post-injury (Figure 1A), with maximum load sustained by callus tissue decreasing from 119.5 N in Group I to 23.4 N in Group IA, (79% decrease, p<0.05). Treatment with NAC following injury prevented this alcohol-related decrease in fracture callus strength. Group IAN was significantly stronger than Group IA with a 4.6-fold increase in maximum load (p<0.05). Alcohol exposure also was also associated with changes in the material properties of the fracture callus (Figure 1B), with mean callus stiffness decreasing by 80% compared to callus from saline-treated animals (p<0.05). Administration of NAC also resulted in a statistically significant increase in callus stiffness in alcohol-treated animals (p<0.05).

Figure 1. Binge Alcohol and Anti-Oxidant Effects on Callus Biomechanics at One Weeks Post Injury.

(A) Bending strength; (B) Stiffness. Treatment groups: Injury, injury without alcohol; Injury + alcohol, injury with binge alcohol; Injury + alcohol + NAC, Injury with binge alcohol and N-acetylcysteine treatment. The alcohol-treated groups showed significantly less strength and stiffness than both the non-alcohol groups and the alcohol with NAC groups. Data was analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test and significance considered for p ≤ 0.05.

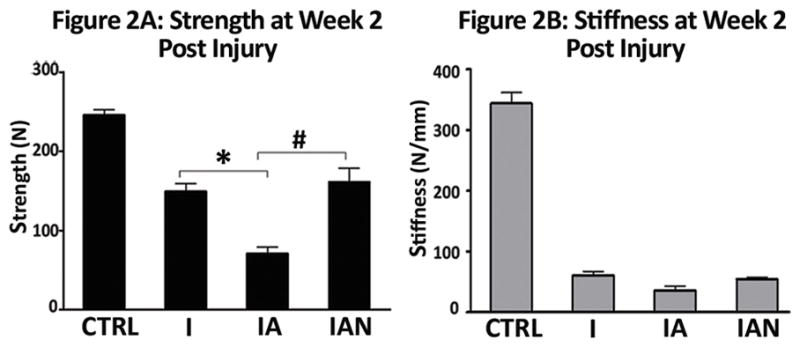

Two-Week Group

Binge alcohol continued to have detrimental effects on fracture callus strength two weeks following fracture injury (Figure 2A). A 53% reduction in callus strength was observed between Group I and Group IA (p < 0.05). Administration of NAC was again associated with an attenuation of alcohol-related effects on callus strength with a 128% increase in strength in Group IAN compared to Group IA (p<0.05). Binge alcohol treatment also continued to significantly decrease callus stiffness 2 weeks following injury (Figure 2B) (I versus IA, p < 0.05). No significant effect of NAC treatment on callus stiffness in alcohol-treated animals was observed at this time point.

Figure 2. Binge Alcohol and Anti-Oxidant Effects on Callus Biomechanics at 2 Weeks Post Injury.

(A) Bending strength; (B) Stiffness. Treatment groups: Injury, injury without alcohol; Injury + alcohol, injury with binge alcohol; Injury + alcohol + NAC, Injury with binge alcohol and N-acetylcysteine treatment. The alcohol-treated group showed significantly less strength than both the non-alcohol group and the alcohol with NAC group but no significant difference in stiffness. Data was analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test and significance considered for p ≤ 0.05.

Four and Six Week Groups

Data generated at four and six weeks following injury demonstrate continued fracture injury healing with increasing callus strength and stiffness observed at each time point in the I group (data not shown). No significant effects were noted at four or six weeks following injury in terms of biomechanical parameters between any of the treatment groups in comparison to control animals.

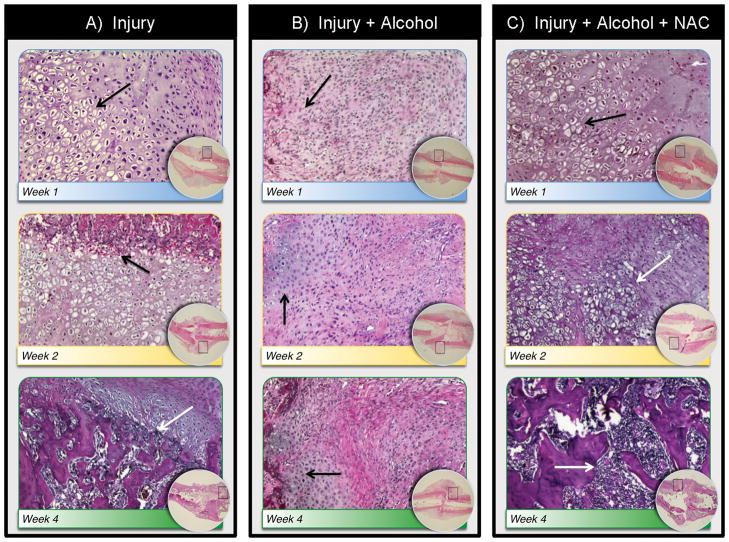

Fracture Callus Histology

Group I: At one week one post-injury, a well-developed cartilaginous external and periosteal callus were present (Figure 3A). At two weeks post-injury, hypertrophic chondrocytes were present throughout the external callus with associated endochondral ossification activity. By four weeks post-injury, the cartilaginous component of the external callus was largely replaced by woven bone. Focal areas of remodeling activity were also observed in the periosteal callus. Group IA: At one week post-injury, a highly cellular external callus composed of immature chondroblast-like cells with minimal matrix deposition was present with notable deposition of collagen fibers. Minimal effects on periosteal callus development were observed (Figure 3B). At two weeks week post-injury, external callus tissue remained immature in nature, highly cellular with continued evidence of collagen deposition. Small focal areas of hyaline cartilage deposition were observed without evidence of hypertrophic chondrocytes or endochondral bone formation. At four weeks post-injury, external callus tissue remained immature and fibrous in nature, however some focal areas of cartilage tissue and endochondral bone formation were now present. Group IAN: At one week post-injury, a well-developed periosteal and cartilaginous external callus was present, similar to control animals. (Figure 3C). At two weeks following injury, hypertrophic chondrocytes and robust endochondral bone formation was observed. By 4 weeks post-injury, the cartilaginous external callus was largely replaced by woven bone; remodeling activity producing compact lamellar bone was also observed. Similar trends in callus development were seen in all groups at 6 weeks following injury (data not shown).

Figure 3. Binge Alcohol and Anti-Oxidant Effects on Fracture Callus Structure and Composition.

Slides were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Low magnification images are shown as inset in each treatment group, with areas of higher magnification indicated by boxed outline. Calluses in Injury groups (A) showed mature and hypertrophic chondrocytes at week 1 (black arrow), endochondral ossification activity and appearance of woven bone at 2 weeks (black arrow) and remodeling activity by 4 weeks (white arrow). Calluses in the Injury + alcohol group (B) showed a fibrous callus with immature chondrocytes at week 1 (black arrow), continuing fibrous callus with the appearance of some mature chondrocytes without significant endochondral ossification activity at 2 weeks (black arrow) and delayed ossification at 4 weeks (black arrow). Samples in Injury + alcohol + NAC group (C) showed normal early cartilaginous callus formation in weeks 1 and 2(black arrows) and endochondral ossification at 2 weeks (black arrow) with active bone remodeling at 4 weeks (white arrow). Samples at 6 weeks showed similar trends (see discussion, data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Excessive alcohol consumption has detrimental effects on bone health 8,9,11,15,19 including a higher risk for complications following fracture injury including non-union 7. The mechanisms of alcohol-deficient fracture healing are not well characterized. In the current investigation we used a clinically relevant binge alcohol exposure model in rats to examine the effects of alcohol on fracture repair following trauma-induced injury of the femur. We found that exposure to alcohol prior to blunt orthopaedic traumatic injury was associated with impaired fracture healing for at least 2 weeks following injury. In addition, we found that administration of N-acetylcysteine during the early post injury period attenuated alcohol’s effects on fracture callus strength and histological structure, including restoration of normal tissue composition and endochondral bone formation. These results strongly suggest that the deleterious effects of alcohol on fracture healing are related to alcohol-induced oxidative stress.

After a fracture, osteoprogenitor cells and undifferentiated mesenchymal cells (MSCs) located in the adjacent periosteum are recruited to the site of injury to start the process of callus formation through both intramembranous and endochondral ossification mechanisms, with endochondral bone formation occurring in the overlying external callus that originates from the fracture hematoma and recruited mesenchymal cells 25. In our study, we observed immature chondroid-like tissue, fibrous tissue and a notable absence of hypertrophic chondrocytes in external callus from binge alcohol treated rats, indicating that alcohol consumption inhibits normal cartilage formation and subsequent endochondral bone formation during fracture repair. Cartilaginous callus formation at the site of injury and associated endochondral ossification was restored to near-normal levels in animals treated with NAC following injury. This data suggests that exogenous augmentation of anti-oxidant levels during fracture callus formation is protective against alcohol-related defects in callus integrity.

While the mechanisms of alcohol’s effects on fracture healing potential remain incompletely understood, recent work has identified an important role for the canonical Wnt signaling pathway in normal fracture repair 26 and MSC lineage commitment 15, 27. Our laboratory has demonstrated a connection between alcohol exposure and perturbation of canonical Wnt signaling activity both in intact bone15 and in fracture callus 28, suggesting that alcohol deficient fracture healing occurs, in part, through a targeted deregulation of canonical Wnt signaling. One possible connection between alcohol exposure and deactivation of the canonical Wnt pathway may be related to increased oxidative stress signaling activity 16. The Forkhead Box O (FoxO) family of proteins are activated by increased oxygen radical activity and the Wnt signaling protein beta-catenin is an important co-activator of FoxO. Oxidative stress promotes FoxO binding to beta-catenin, which leads to FoxO transcription activation 29. Beta-catenin is also an important co-activator in the Wnt pathway, and oxidative stress has been demonstrated to inhibit the Wnt pathway by shifting beta-catenin activity toward FoxO and away from binding to canonical Wnt transcription factor TCF 17, 18.

Based on this previous data, we hypothesized that binge alcohol exposure prior to injury would inhibit bone fracture repair and that antioxidant therapy would mitigate this effect. Our results support this hypothesis. While the current study does not explore molecular mechanisms underlying the inhibition of callus formation caused by alcohol or the reversal of this effect by NAC, the data does support the supposition that these results could be due an alcohol-related increase in oxidative stress, which in turn inhibits canonical Wnt activity crucial for normal fracture repair. This possibility is supported by our histology data. The dramatic decrease in endochondral ossification activity observed in callus from alcohol treated animals at two weeks post-injury is suggestive of a deregulation of canonical Wnt signaling activity. Previous studies have demonstrated that perturbation of the precise regulation of canonical Wnt signaling activity blocks chondrocyte hypertrophy and ensuing endochondral ossification activity in the growth plate 30 and that activation of beta-catenin-TCF mediated transcriptional activity induces de novo endochondral bone formation 6. Thus a deactivation of canonical wnt activity in the callus produces a callus histological phenotype similar to what we observe in alcohol-treated rats. When our alcohol-treated rats were given NAC, we observed a qualitative normalization of callus histological structure including recovery of hypertrophic chondrocytes and endochondral bone formation activity to levels indistinguishable from normal fracture healing observed in saline control rats, suggesting that antioxidant treatment reduces oxidative stress and restores the normal balance of oxidative stress and canonical Wnt signaling activity in the fracture callus of alcohol-treated animals.

We found no statistically significant differences in fracture callus strength between alcohol and saline-treated animals at 4 or more weeks post-injury. Since animal were treated with binge alcohol only prior to and not following bone fracture injury, the effects of alcohol on the repair process in our model, although significant, could be transient. It is possible that the downstream effects of binge alcohol-induced oxidative stress dissipate with time. In addition, administration of N-acetylcysteine was discontinued after 2 weeks, so the withdrawal of NAC may have allowed the alcohol-treated groups (with NAC and without NAC) to normalize relative to each other once the anti-oxidant effect was removed. While the effects of alcohol on callus strength does diminish over time, effects on callus histological structure were still readily apparent at later time points, suggesting that pre-injury exposure to alcohol has long lasting repercussions on the skeletal response to injury related to callus composition and structure. The replacement of cartilaginous tissue with fibrous repair tissue and/or increased intramembranous ossification activity is observed in non-stabilized fractures 31. These alternate healing mechanisms could result in a partial augmentation of callus bridging strength in the absence of normal callus architecture in alcohol-treated animals. How (or if) the fibrous callus produced in alcohol-exposed animals is eventually replaced by a normal healed bone structure in our model is not known and would require a longer term examination of callus structure during the remodeling stage of healing. Prolonged fibrous tissue formation in the callus is associated with delayed fracture healing 32. Thus, the long terms effects of pre-injury binge alcohol exposure on callus-remodeling activity and the eventual resolution of a bone fracture injury remain undetermined.

Limitations of the current study includes use of a rodent model of alcohol exposure and traumatic orthopaedic injury, however, this model has been utilized in previous studies of traumatic orthopaedic injury24, 33, 34. Because a blunt trauma device was used to create the injury, it was impossible to ensure exact reproducibility in fracture site and orientation; some fractures were slightly oblique or more distal than anticipated. Although somewhat variable, fracture injuries sustained likely replicate the clinical presentations of traumatic closed femur fractures. NAC administration was continued for only two weeks as we could find no reports in the literature of administration of NAC beyond 2 weeks in a rat model. In retrospect, it might have been beneficial to carry out NAC administration for the full 4 or 6 weeks to determine how long the effect lasts.

In summary, this study provides evidence that exposure to alcohol prior to traumatic bone injury has detrimental effects on fracture repair and that administration of NAC was associated with a reversal of alcohol-related effects on callus strength and fracture callus histological structure. Future studies may help delineate the mechanisms behind this effect. Further studies should also examine the long-term effects of NAC administration following alcohol exposure and traumatic injury to determine if NAC may indeed be a safe and useful agent in cases of orthopedic injury complicated by alcohol intoxication.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism:

(R01 AA016138 (JJC), F31 AA019613 (KL) and T32 AA013257.

Footnotes

No benefits in any form have been or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this manuscript.

This study was presented in part at the Annual Meeting of the Orthopaedic Trauma Association. Baltimore, Maryland, 2010.

References

- 1.McGinnis JM, Foege WH. Mortality and morbidity attributable to use of addictive substances in the United States. Proc Assoc Am Physicians. 2009;111:109–118. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1381.1999.09256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grieffenstein P, Molina PE. Alcohol-induced alterations on host defense after traumatic injury. Journal of Trauma. 2008;64:230–240. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318158a4ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lowenfels A, Miller T. Alcohol and trauma. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 1984;13:1056–1060. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(84)80070-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaukonen JP, Nurmi-Luthje I, Luthju P, Naboulsi H, Tanninen S, Kataja M, Kallio ML, Leppilampi M. Acute alcohol use among patients with acute hip fractures: A descriptive incidence study in southeastern Finland. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2006;41(3):345–348. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor D, Miller T, Cox K. Impaired driving in the United States: Cost fact sheets. National Highway traffic Safety Administration; Washington, D.C: 2002. http://www.nhtsa.dot.gov/people/injury/alcohol/impaired_driving_pg2/US.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kitagaki J, Iwamoto M, Liu JG, Tamamura Y, Pacifci M, Enomoto-Iwamoto M. Activation of β-catenin-LEF/TCF signal pathway in chondrocytes stimulates ectopic endochondral ossification. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2003;11(1):36–43. doi: 10.1053/joca.2002.0863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kristensson H, Lunden A, Nilsson BE. Fracture incidence and diagnostic roentgen in alcoholics. Acta Orthopaedic Scandanavia. 1980;51(2):205–207. doi: 10.3109/17453678008990787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trevisiol CH, Turner RT, Pfaff JE, Hunter JC, Menagh PJ, Hardin K, Ho E, Iwaniec UT. Impaired osteoinduction in a rat model for chronic alcohol abuse. Bone. 2007;41(2):175–180. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.04.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chakkalakal DA, Novak JR, Fritz ED, Mollner TJ, McVicker DL, Garvin KL, McGuire MH, Donohue TM. Inhibition of bone repair in a rat model for chronic and excessive alcohol consumption. Alcohol. 2005;36(3):201–214. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Broulik PD, Rosenkrancova J, Ruzicka P, Sedlacek R, Zima T. The effect of chronic alcohol administration on bone mineral content and bone strength in male rats. Physiological Research. 2009 Nov 20; (E-publication ahead of print) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Callaci JJ, Juknelis D, Patwardhan A, Sartori M, Frost N, Wezeman FH. The effects of binge alcohol exposure on bone resorption and biomechanical and structural properties are offset by concurrent bisphosphonate treatment. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2004;28(1):182–191. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000108661.41560.BF. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lauing K, Himes R, Rachwalski M, Strotman P, Callaci JJ. Binge alcohol treatment of adolescent rats followed by alcohol abstinence is associated with site-specific differences in bone loss and incomplete recovery of bone mass and strength. Alcohol. 2008;42(8):649–656. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clement-Lacroix P, Ai M, Morvan F, Roman-Roman S, Vayssiere B, Belleville C, Estrera K, Warman ML, Baron R, Rawadi G. Lrp5-independent activation of Wnt signaling by lithium chloride increases bone formation and bone mass in mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(48):17406–17411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505259102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Day TF, Guo X, Garrett-Beal L, Yang Y. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in mesenchymal progenitors controls osteoblast and chondrocyte differentiation during vertebrate skeletogenesis. Developmental Cell. 2005;8(5):736–750. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Himes R, Wezeman FH, Callaci JJ. Identification of novel bone-specific molecular targets of binge alcohol and ibandronate by transcriptome analysis. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32(7):1167–1180. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00736.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu D, Cederbaum AI. Alcohol, oxidative stress and free radical damage. Alcohol Research and Health. 2003;27(4):277–284. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shin SY, Kim CG, Jho EH, Rho MS, Kim YS, Kim YH, Lee YH. Hydrogen peroxide negatively modulates Wnt signaling through downregulation of β-catenin. Cancer Letters. 2004;212:225–231. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Almeida M, Han L, Martin-Millan M, O’Brien CA, Manolagas SC. Oxidative stress antagonizes Wnt signaling in osteoblast precursors by diverting b-catenin from T-cell factor to Forkhead Box O-mediated transcription. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282(37):27298–27305. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702811200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sendur OF, Turan Y, Tastaban E, Serter M. Antioxidant status in patients with osteoporosis: A controlled study. Joint Bone Spine. 2009;76(5):514–518. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zafarullah M, Li WQ, Sylvester J, Ahmad M. Molecular mechanisms of N-acetylcysteine actions. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2003;60(1):6–20. doi: 10.1007/s000180300001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Timlin M, Condron C, Toomey D, Power C, Thornes B, Kearns S, Street J, Murray P, Bouchler-Hayes D. N-acetylcysteine attenuates lung injury in a rodent model of fracture. Acta Orthop Scand. 2004;75(1):61–65. doi: 10.1080/00016470410001708120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferreira Seiva FR, Amauchi JF, Ribeiro Rocha KK, Souza GA, Ebaid GX, Burneiko RM, Novelli EL. Effects of N-acetylcysteine on alcohol abstinence and alcohol-induced adverse effects in rats. Alcohol. 2009;43(2):127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Penland S, Hoplight B, Obernier J, Crews FT. Effects of nicotine on ethanol dependence and brain damage. Alcohol. 2001;24(1):45–54. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(01)00142-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bonnarens F, Einhorn TA. Production of a standard closed fracture in laboratory animal bone. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 1984;2:97–101. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100020115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Einhorn TA. The cell and molecular biology of fracture healing. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 1998;355 (Suppl):S7–S21. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199810001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Komatsu DE, Mary MN, Schroeder RJ, Robling AG, Turner CH, Warden SJ. Modulation of Wnt signaling influences fracture repair. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 2010 Jan 8; doi: 10.1002/jor.21078. (E-publication ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen Y, Whetsone HC, Lin AC, Nadesan P, Wei Q, Poon R, Alman BA. Beta-catenin signaling plays a disparate role in different phases of fracture repair: Implications for therapy to improve bone healing. PLoS Medicine. 2007;4(7):1216–1229. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jung MK, Callaci JJ, Lauing KL, Otis JS, Radek KA, Jones MK, Kovacs EJ. Alcohol exposure and mechanisms of tissue injury and repair. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010 Nov 30; doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01356.x. Epublication ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manolagas SC. From estrogen-centric to aging and oxidative stress: A revised perspective of the pathogenesis of osteoporosis. Endocrine Reviews. 2010;31(3):1–35. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tamamura Y, Otani T, Kanatani N, Koyama E, Kitagaki J, Komori T, Yamada Y, Constantini F, Wakisaka S, Pacifci M, Iwamoto M, Enomoto-Iwamoto M. Developmental regulation of Wnt/β-catenin signals is required for growth plate assembly, cartilage integrity, and endochondral ossification. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280:19185–19195. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414275200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Giannoudis PV, Einhorn TA, Marsh D. Fracture healing: a harmony of optimal biology and optimal fixation. Injury. 2007;38(Suppl 4):S1–2. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(08)70002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holstein JH, Matthys R, Histing T, Becker SC, Fiedler M, Garcia P, Meier C, Pohlemann T, Menger MD. Development of a stable closed femoral fracture model in mice. J Surg Res. 2009;153(1):71–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2008.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brown KM, Saunders MM, Kirsch T, Donahue HJ, Reid JS. Effect of cox-2 specific inhibition on fracture-healing in the rat femur. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (Am) 2004;86-A(1):116–123. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200401000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hak DJ, Stewart RL, Hazelwood SJ. Effect of low molecular weight heparin on fracture healing in a stabilized rat femur fracture model. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 2006;24(4):645–652. doi: 10.1002/jor.20090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]