Abstract

Diffusion tensor and structural MRI images were acquired on ninety-six patients with schizophrenia (69 men and 27 women between the ages of 18 and 79 (mean = 39.83, SD = 15.16 DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia according to the Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms and History). The patients reported a mean age of onset of 23 years (range = 13–38, SD = 6). Patients were divided into an acute subgroup (duration ≤ 3 years, n = 25), and a chronic subgroup (duration > 3 years, n = 64). Ninety-three mentally normal comparison subjects were recruited; 55 men and 38 women between the ages of 18 and 82 (mean = 35.77, SD = 18.12). The MRI images were segmented by Brodmann area, and the fractional anisotropy (FA) for the white matter within each Brodmann area was calculated. The FA in white matter was decreased in patients with schizophrenia broadly across the entire brain, but to a greater extent in white matter underneath frontal, temporal and cingulate cortical areas. Both normals and patients with schizophrenia showed a decrease in anisotropy with age but patients with schizophrenia showed a significantly greater rate of decrease in FA in Brodmann area 10 bilaterally, 11 in the left hemisphere and 34 in the right hemisphere. When the effect of age was removed, patients ill more than three years showed lower anisotropy in frontal motor and cingulate white matter in comparison to acute patients ill three years or less, consistent with an ongoing progression of the illness.

Keywords: Schizophrenia, White Matter, Diffusion Tensor Imaging, Anisotropy, Brodmann Areas, Age

1. Introduction

White matter changes and oligodendroglia dysfunction recently have been a growing area of research in schizophrenia (Davis et al., 2003). Much of the work has been done using Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI) to investigate the health and integrity of the white matter in living patients with the disorder. Since the earliest study (Buchsbaum et al., 1998) despite variation in the methods and measures used in DTI studies in schizophrenia, the most commonly used measure, Fractional Anisotropy (FA), has been shown to be decreased in the white matter of patients with schizophrenia in the majority of studies (See reviews in Kanaan et al., 2005; Kubicki et al., 2007; Schneiderman et al., 2009).

The majority of work in DTI has not investigated the role of age or duration of illness on diffusion anisotropy within white matter. Patients with schizophrenia between the ages of 10 and 20 showed a decrease in FA in the left anterior cingulate while normal adolescents showed an increase in FA with age (Kumra et al., 2005). We previously found different patterns of abnormality in anisotropy in white matter projections to the frontal lobe in adolescent and adult patients with schizophrenia (Schneiderman et al., 2009). Negative correlations between white matter anisotropy and duration of illness or age has been found in adults in the cingulum, uncinate, and corpus callosum (Jones et al., 2006; Mori et al., 2007; Carpenter et al., 2008; Rosenberger et al., 2008; Segal et al., 2010). A recent study by our group found that patients with schizophrenia showed a greater decline in FA with age in the forceps major and the inferior longitudinal fasciculus in patients then in normal controls (Friedman et al., 2008). Some studies however have failed to find age-related changes in FA in adults with schizophrenia (McIntosh et al., 2008; Kanaan et al., 2009; Voineskos et al., 2010). This study presents a comprehensive survey of the changes in FA in cerebral white matter, divided by Brodmann Area, between patients with schizophrenia and normal controls as well as the effects of duration of illness and age.

2. Methods

2.1 Subjects

Ninety-six patients with schizophrenia were recruited from inpatient, outpatient, day treatment, and vocational rehabilitation services at Mount Sinai Hospital (New York), Pilgrim Psychiatric Center (W. Brentwood, New York), Bronx Veterans Affairs Medical Center (Bronx, New York), Hudson Valley Veterans Affairs Medical Center (Montrose, New York), and Queens Hospital Center (Jamaica, New York) after approvals by each institutional review board and informed consent was obtained from each subject (see Tables 1 and 2). All patients had a DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia according to the Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms And History (CASH: Andreasen et al., 1992). Ninety-three mentally normal comparison subjects were recruited from the New York area and did not meet criteria for a DSM-IV axis I disorder (by CASH interview).

Table 1.

Subjects

| Group | Age | Sex | Handedness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (n=96) | 18–79 (mean = 39.83, SD = 15.16, unavailable for one patient) | 69 Male, 27 Female | 85 Right, 6 Left, 3 Mixed, 2 Unavailable |

| Controls (n=93) | 18–82 (mean = 35.77, SD = 18.12) | 55 Male, 38 Female | 84 Right, 8 Left, 1 Unavailable |

Table 2.

Patient Groups

| Group | Age | Sex | Handedness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute (n=25) | 18–35 (mean = 25.28, SD = 5.38) | 19 Male, 6 Female | 23 Right, 2 Left |

| Chronic (n=64) | 22–79 (mean = 45.39, SD = 14.34) | 46 Male, 18 Female | 57 Right, 3 Left, 3 Mixed, 1 Unavailable |

Subjects were excluded if they had, a positive urine-screen for drugs of abuse, medical diagnosis that might produce white matter changes (e.g., HIV, multiple sclerosis), brain disorder that might produce cognitive impairment or behavioral symptoms (e.g., head injury, cerebrovascular disease), unstable medical condition (e.g., poorly controlled diabetes or hypertension, symptomatic coronary artery disease), or lifetime history of substance dependence or evidence of substance abuse in the past year according to DSM-IV criteria. An examination of anisotropy differences by statistical parametric mapping in a subset of the subjects (64 patients with schizophrenia) has been previously published (Buchsbaum et al., 2006), as has a region of interest study (n=159) of the forceps minor, forceps major, corpus callosum and superior longitudinal fasciculus (Friedman et al., 2008). Tang et al. (2007) published findings on N-actylaspartate (NAA) as measured by Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (MRS) as correlated with regional fractional anisotropy in a much smaller subset of this sample (40 subjects with schizophrenia and 42 controls). This analysis has a much larger sample and analyzes specific white matter regions of interest.

2.2 Image Acquisition

Anatomical images were acquired (3.0 T Siemens Allegra; typical scanning time 50 minutes) with a magnetization prepared rapid gradient echo (MP-RAGE) sequence with TR = 2500 ms, TE = 4.4 ms, FOV = 21 cm, matrix size = 256 × 256, and 208 slices with thickness = 0.82 mm. Diffusion tensor images were acquired with a pulsed gradient spin-echo sequence with TR = 4100 ms, TE = 80 ms, FOV = 21 cm, matrix = 128 × 128, 28 slices, thickness = 3 mm skip 1 mm, b-factor = 1250 s/mm2, and 12 gradient directions. Five acquisitions were averaged to improve the signal-to-noise ratio.

2.3 Image Processing

2.3.1 DTI Preprocessing

Fractional Anisotropy (FA) was calculated for each subject as previously described (Buchsbaum et al., 2006; Mitelman et al., 2006). Brain masks for the DTI and MP-RAGE sequences were created with FSL Brain Extraction Tool (BET) and the skulls and scalps removed from the images (Jenkinson et al., 2005). The FA and MP-RAGE were coregistered with 12-parameter transformation using FSL FLIRT (Jenkinson and Smith, 2001).

2.3.2 Brodmann analysis

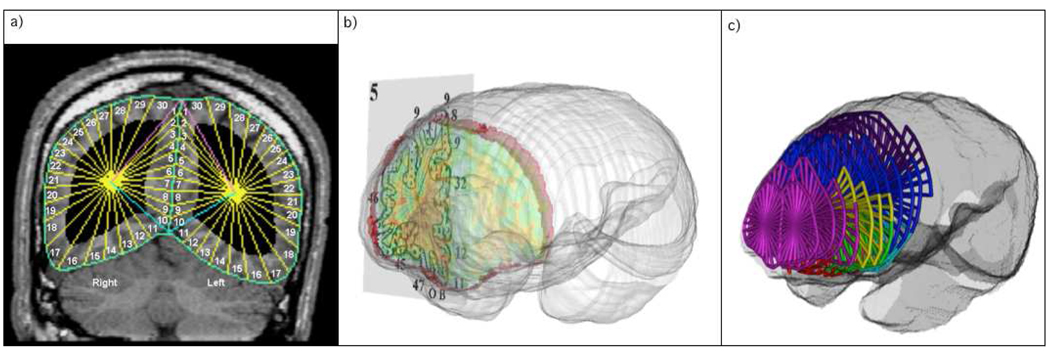

Perry et al. (1991) provided a coronal atlas composed of 33 axial maps of Brodmann’s areas (BA), based on microscopic examination of entire hemisphere of a post-mortem brain. Our earlier use of the Perry atlas approach was described in detail in (Hazlett et al., 1998; Stein et al., 1998; Simeon et al., 2000; Mitelman et al., 2005). Coronal slices in the subject’s native space MRI and perpendicular to the ACPC line were reconstructed in a 256×256 pixel matrix (Figure 1). The front and back of the brain were determined and 33 evenly spaced slices were identified. The temporal pole and the posterior extent of the Sylvian fissure were identified and the space was divided into 13 equally spaced slices. The brain edge was obtained on the approximately circular 33 non-temporal slices and 26 (13 in each hemisphere) temporal slices by depositing points visually on the tips of the gyri and fitting a spline curve to the points. Each slice was then divided into 20 radial sectors on each hemisphere surface and 10 midline sectors (Hazlett et al., 1998). Since this was done in native space for each individual MRI no coregistration to another atlas was necessary.

Figure 1. Segmentation Method.

a) Manually defined cortical edges and midline divided into radial sections. b) Perry Atlas overlay onto coronal slices. c) Coronal slices divided into Brodmann Regions.

Brodmann areas were then assessed for the gray, white, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pixels within each sector; FA means are weighted according to the number of sectors in each region of interest and proportionately combined to obtain a single measure (Mitelman et al., 2009). Some of the smallest Brodmann areas are combined (e.g. 1-2-3-5) for conservative simplicity and area 7 is split into 7a and 7b. Data from 39 Brodmann areas identified by Perry were obtained.

2.4 Statistical Processing

We examined FA using repeated measures MANOVA and ANOVA (StatSoft, 2003). We compared major brain regions previously reported to show fractional anisotropy differences with nested MANOVA with diagnostic category (patients, normals) as an independent group dimension and Lobe, Hemisphere and Brodmann area as repeated measures. Then follow-up and exploratory repeated measure ANOVAs between patient and control groups were performed on the lateral temporal lobes (areas 20, 21, and 22), cingulate (areas 23, 24, 25, 19 and 31), and the anterior (areas 8, 9 and 10), medial (areas 24, 25 and 32), orbital (areas 11, 12, and 47), and dorsal (areas 44, 45 and 46) portions of the frontal lobe. Between-group t-tests were then performed on the anisotropy values for the white matter in each Brodmann region between the control subjects and the schizophrenic patients to determine the effect of diagnosis. Factorial ANOVAs were performed with anisotropy as the dependent variable and diagnosis and sex as the categorical factors to determine if there were any gender by diagnosis interactions. To determine the effect of duration of illness analysis of covariance were performed on the anisotropy values controlled for age for the white matter in each Brodmann region between the acute and chronic subgroups. To determine any sex effects between the acute and chronic subgroups, sex was added as a categorical value in the analysis of covariance. Mixed factorial repeated-measures ANOVAs were employed to examine group differences in order to reduce the number of independent statistical tests and mitigate Type I statistical error. Since earlier investigators have reported extensively on a large number of brain areas (see introduction) we also present the full analysis set (38 BAs identified by Perry), for t-test comparisons with past and future analyses. Reports on nine of the 12 frontal Brodmann areas (Oh et al., 2009) and the tabular review of Kyriakopoulos et al. (2008) noting the abnormalities in “many diverse brain regions” in 40 studies are consistent with this approach. Further, it would not be appropriate to produce automated data on all 38 Brodmann’s areas in the right and left hemispheres and then adopt a Bonferroni corrected probability criterion that disconfirmed earlier reports or failed to find consistency with earlier single regional results. For these reasons, we present the map analysis at a p value equal or less than 0.05 and the illustrations have a color bar allowing interpretation of Brodmann areas as replication (p<0.05) or with correction for multiple testing (0.0013).

Correlations between age and anisotropy were performed for each Brodmann region in both the normal and patient populations. The correlation coefficient and the slopes of the linear regressions for the correlations were reported. To compare the slopes of the change in anisotropy in age between the normal and patient groups we used Statistica GLM Type III (StatSoft, 2003) decomposition to test the diagnostic group interaction with the slope of the age regression line.

3. Results

3.1 Diagnosis Effects

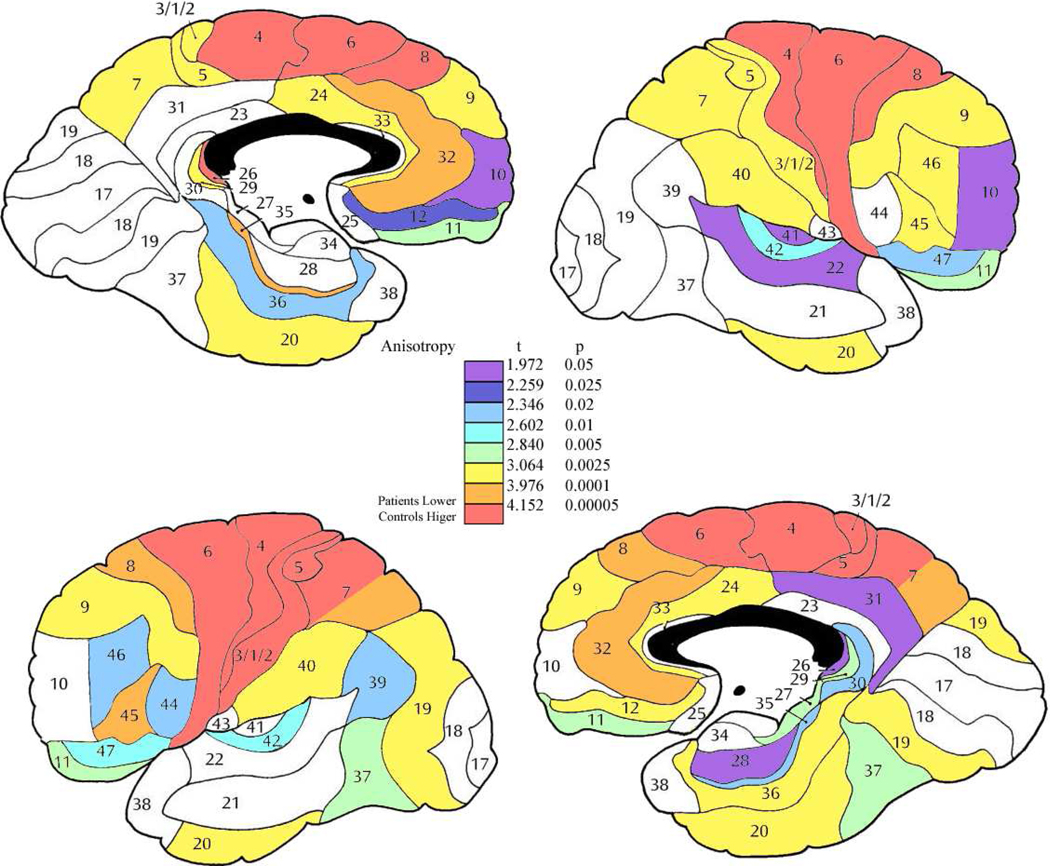

The nested MANOVAs showed lower anisotropy in the patient group as compared to the normal group in the frontal lobe (8,9,10, 11,12,47,24,25,32,44,45,46, F=17.54, df=1,187, p=0.000043), temporal lobe (areas 20, 21, and 22; F = 9.50, df = 1, 187, p = 0.0023) and the cingulate (areas 23, 24, 25, 19 and 31; F = 11.31, df = 1, 187, p = 0.00093, Figures 2 and 3). The ANOVAs showed that in the frontal lobe, the anterior (areas 8, 9 and 10; F = 14.29, df = 1, 187, p = 0.00021), medial (areas 24, 25 and 32; F = 13.53, df = 1, 187, p = 0.00031), orbital (areas 11, 12 and 47; F = 11.33, df = 1, 187, p = 0.00092), and dorsal (areas 44, 45, and 46; F = 13.98, df = 1, 187, p = 0.00025) regions all showed significantly lower anisotropy in patients with schizophrenia compared to healthy controls.

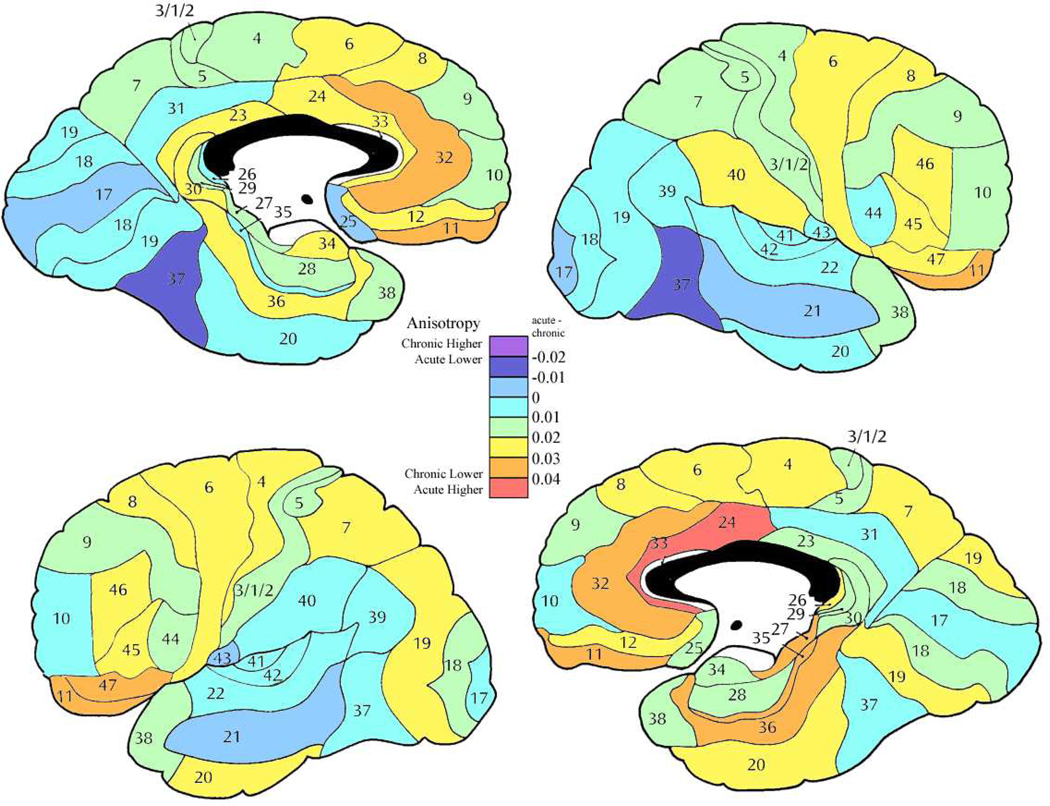

Figure 2. Anisotropy differences between normal volunteers and patient group.

Color scale shows results of t-tests comparing normal volunteers and patients. All areas showing significant differences were higher in normal volunteers than patients. Note that the color bar allows interpretation of the data as replication (Brodmann area 10 decreased FA as reported by ourselves and others earlier) or interpret the 38 areas as entirely independent and using the Bonferroni criteria evaluate areas significant at 0.0013 (orange and red).

Figure 3. Mean anisotropy differences between control and patient groups.

Color bar shows magnitude of FA differences indicates the normal volunteer minus patient difference values. All differences were positive (above zero) except for area 38 in the right hemisphere.

The frontal lobe has been compared with the occipital lobe in our previous MRI study (Mitelman et al., 2005). For this reason we compared the frontal and occipital lobes. Patients had significantly more anisotropy reduction in the orbitofrontal lobe (BA 11,12,47; controls = 0.328, patients = 0.308) than the occipital lobe (BA 17, 18, 19, controls = 0.241, patients = 0.233, group by lobe interaction, F=5.02, df=1,187, p=0.026, Wilks .97, F = 5.02, df = 1, 187, p =0 .026).

Due to the presence of auditory and somatosensory symptoms in schizophrenia, the primary sensory areas associated with these modalities were compared to primary visual cortex where symptomatology is rarer in schizophrenia. Patients had their greatest anisotropy reduction in somatosensory cortex (BA 1-2-3-5, 7a) with slightly less reduction in primary auditory cortex (BA41, 42) and little difference in primary visual cortex (BA 17,18; group by region interaction, F = 5.45, df = 2, 374, p = 0.0046),

The follow-up t-tests showed that lower anisotropy in the patient group was wide-spread throughout the brain in both hemispheres most notably in the bilateral anterior cingulate, bilateral medial parietal, bilateral posterior frontal, bilateral orbitofrontal, left superior parietal, and the left medial temporal regions (figures 2 and 3). Follow-up ANOVA including both diagnostic group and sex revealed that only area 41 on the left showed a diagnostic group by sex interaction effect with female patients showing lower anisotropy then female controls and men showing no significant difference in anisotropy between groups (F = 5.30, df = 1, 185, p = 0.022).

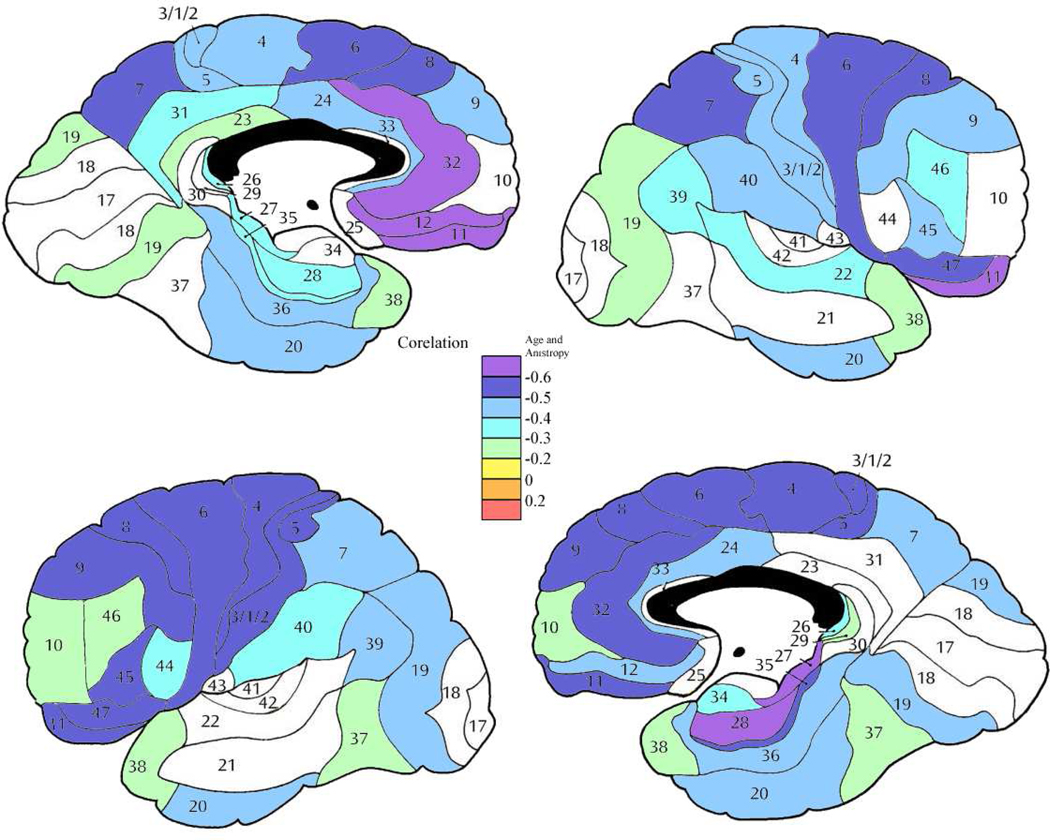

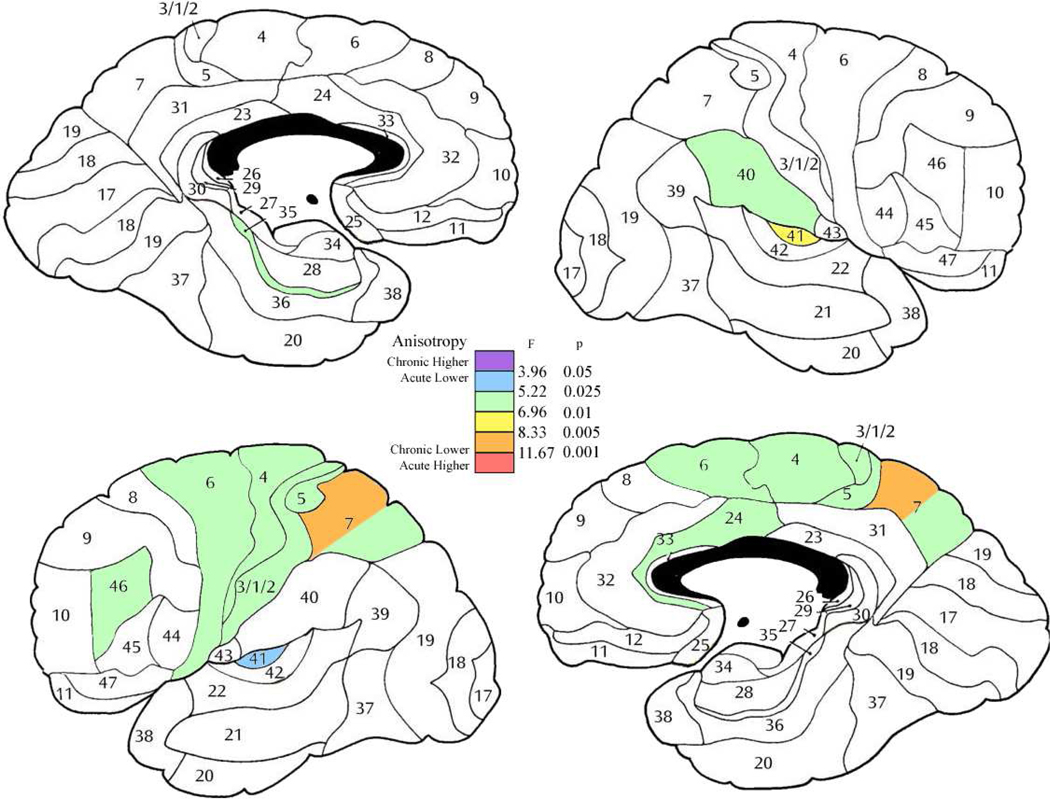

3.2 Acute vs. Chronic Schizophrenia Effects

In general, chronic patients showed lower anisotropy then acute with this effect largest in the anterior cingulate bilaterally, orbitofrontal bilaterally, and medial temporal in the left hemisphere (Figure 3). Several regions showed sex by subgroup (acute versus chronic) interaction. The most common of these interactions were that in the acute stage men had lower anisotropy then the women, but in the chronic stage men had a higher anisotropy then women. This was seen in dorsolateral frontal, orbitofrontal and superior temporal regions (right area 8 (F = 4.24, df = 1, 84, p = 0.042); left areas 9 (F = 5.61, df = 1, 84, p = 0.020), 12 (F = 4.96, df = 1, 84, p = 0.028), 22 (F = 4.72, df = 1, 84, p = 0.028) and 45 (F = 5.40, df = 1, 84, p =0.022)). In area 10 on the left, the women were approximately equal in both groups, but the men in the acute stage showed lower anisotropy then the women, and the men in the chronic stage higher anisotropy (F = 4.02, df = 1, 84, p = 0.048). However in area 46 on the left, the men had similar anisotropy values in the acute and chronic groups while the women in the acute stage had a higher anisotropy and the women in the chronic stage lower anisotropy (F = 8.81, df = 1, 84, p = 0.0038).

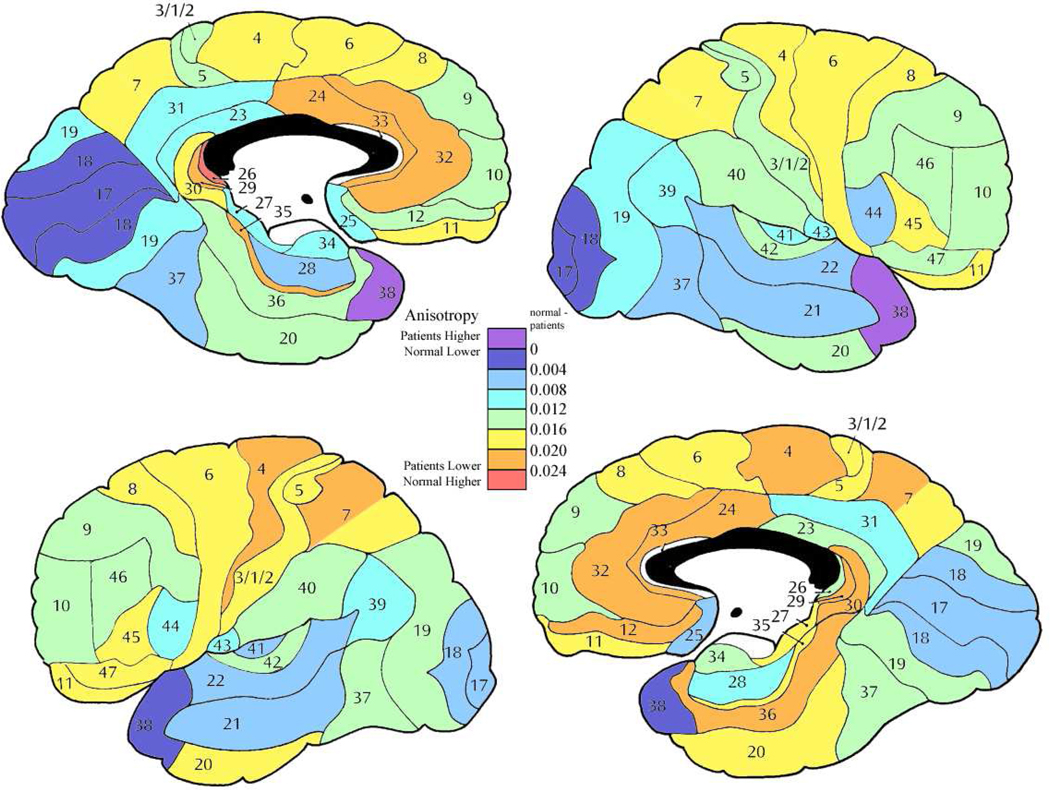

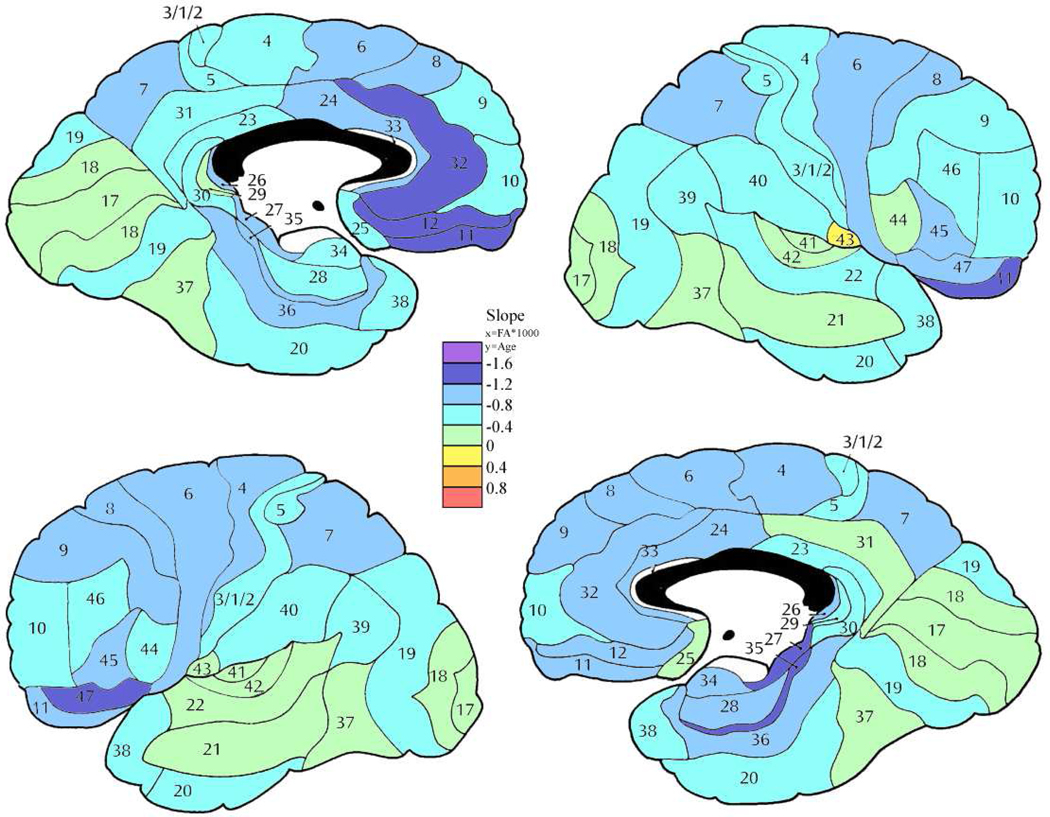

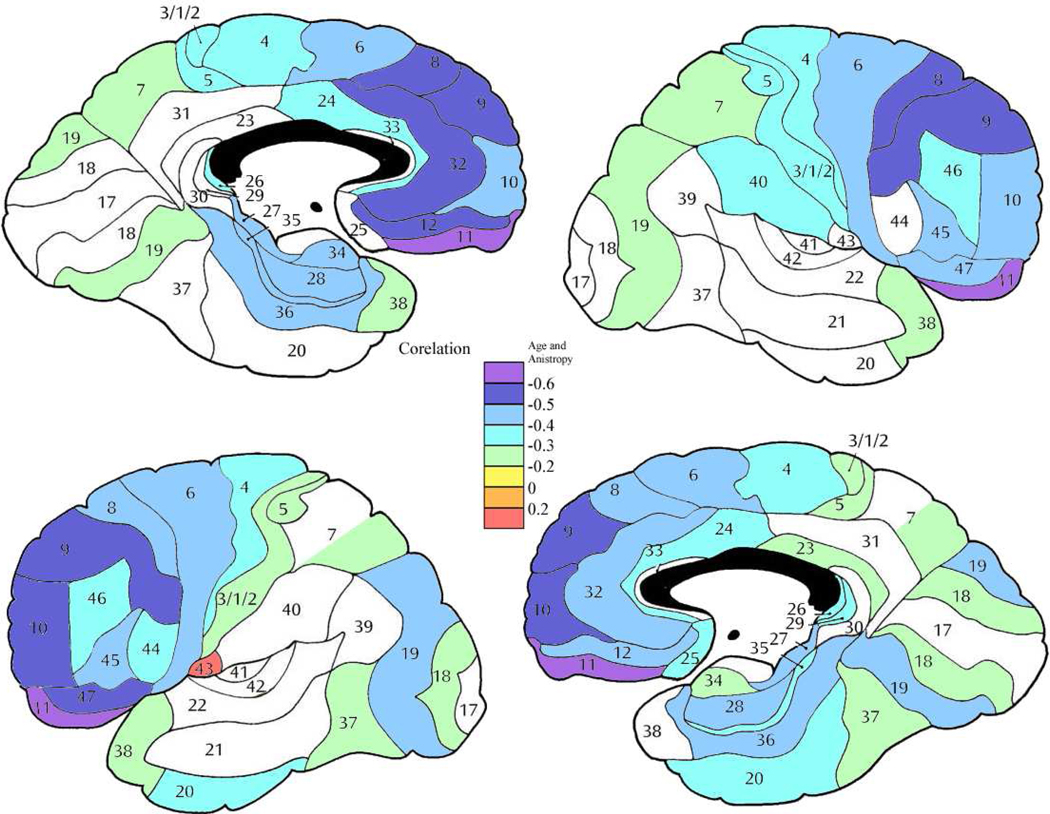

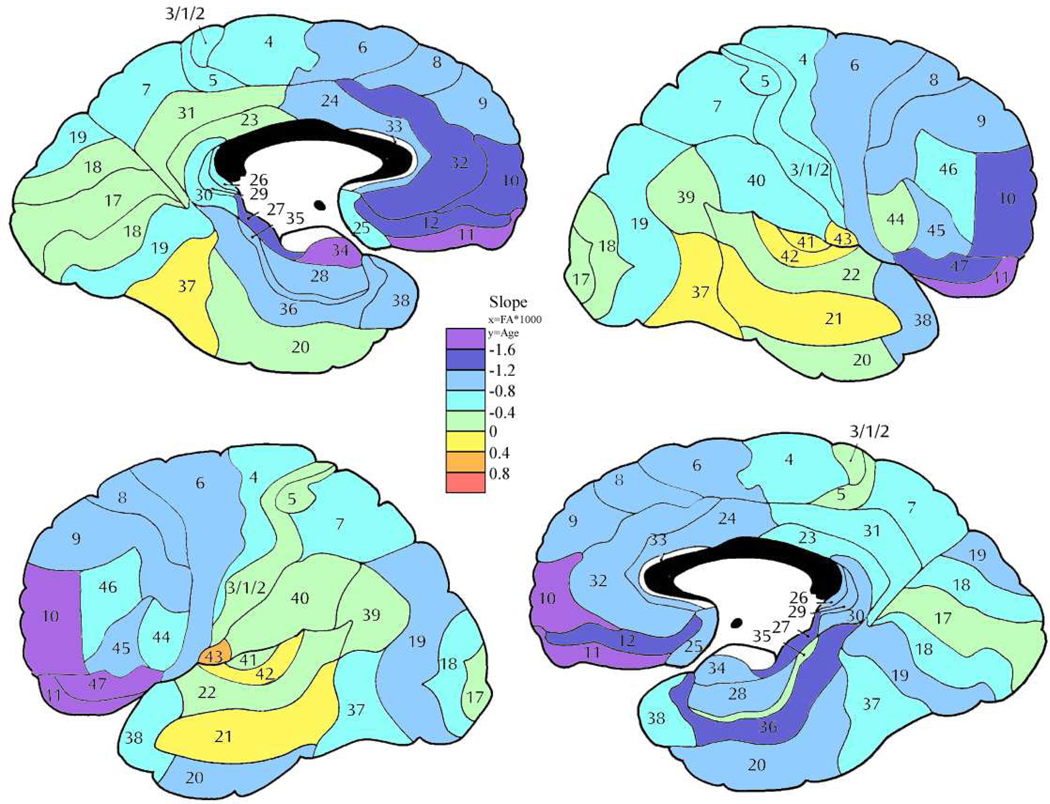

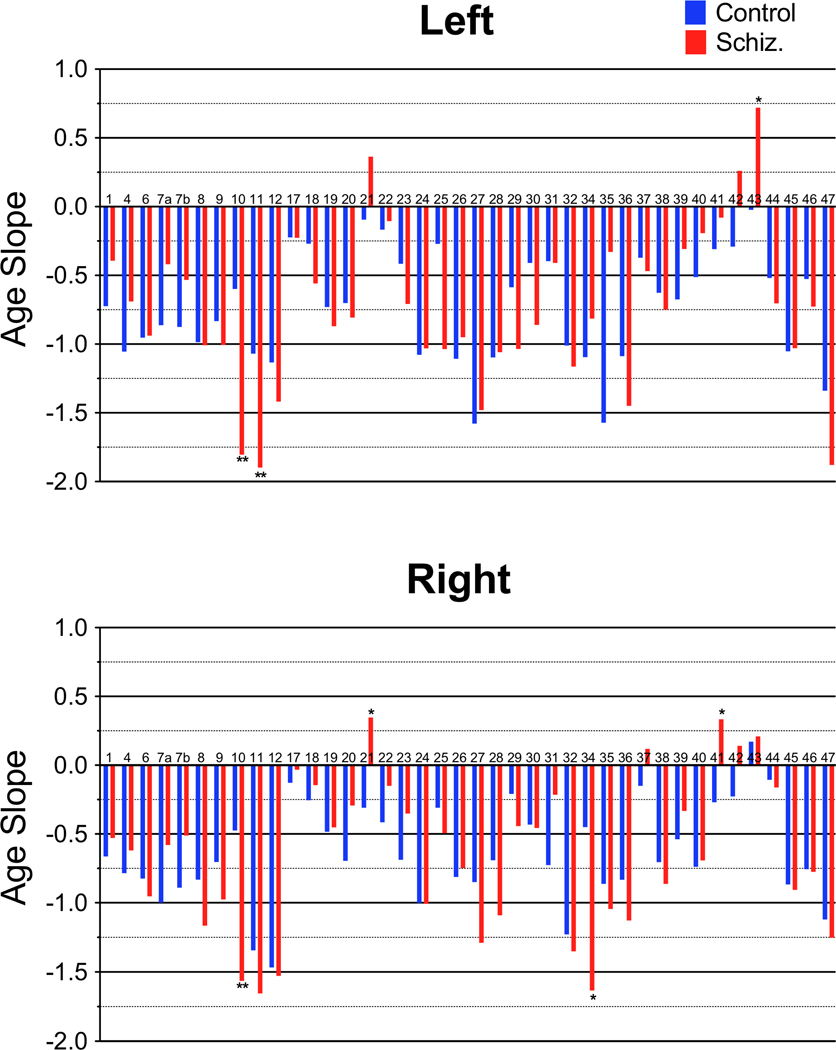

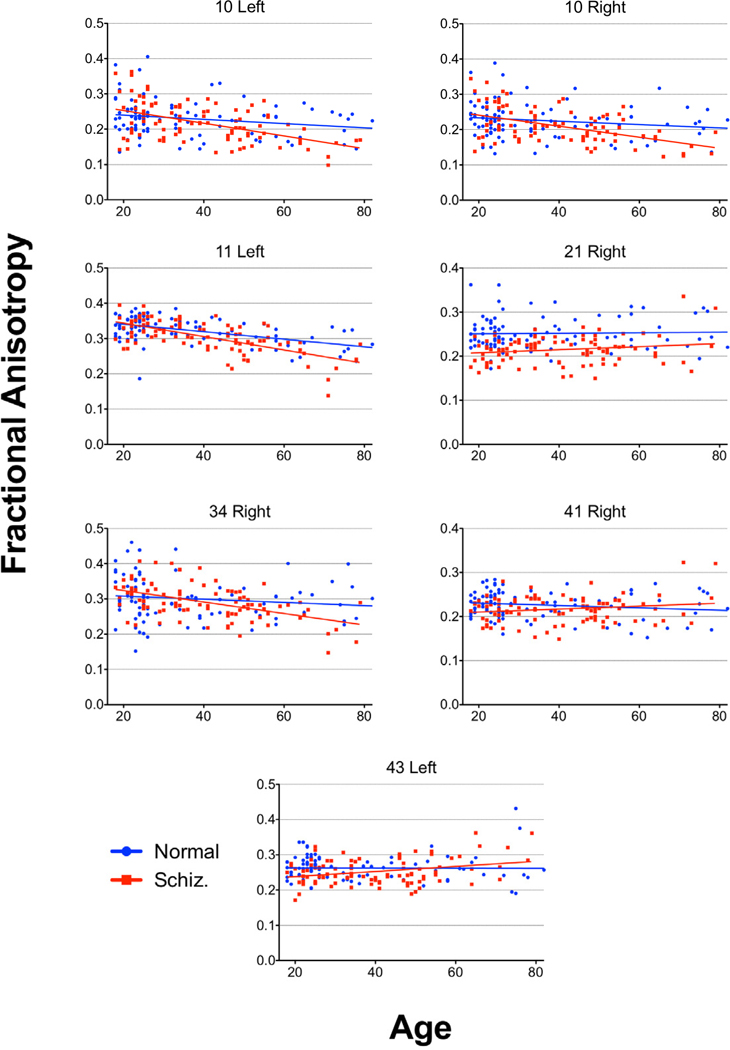

3.3 Age Regression

In control subjects, negative correlations between age and anisotropy were seen throughout the whole brain (Figures 6 and 7). Patients with schizophrenia also showed negative correlations between age and anisotropy (see Figure 8) broadly across the brain, with the effect greatest in similar areas. In most brain areas the slopes of the age regression lines in patients with schizophrenia had slopes similar to those seen in the normal population (Figure 9). However, patients with schizophrenia showed a greater rate of decrease in anisotropy with age in area 10 bilaterally (figures 10 and 11; left, F = 7.46, df = 1, 184, p = .0069; right, F = 7.08, df = 1, 184, p = 0.0084), area 11 on the left (F = 7.65, df = 1, 184, p = 0.0062) and area 34 on the right (F = 6.19, df = 1, 184, p = 0.013). In the left area 43 (F = 5.33, df = 1, 184, p = 0.022) and on the right areas 21 (F = 5.47, df = 1, 184, p = 0.020) and 41 (F = 5.01, df = 1, 184, p = 0.026) the control group showed a negative correlation between age and anisotropy but the patient group showed a positive correlation. None of these positive correlations in the patient group, by themselves were statistically significant.

Figure 6. Correlation between age and anisotropy in the normal volunteer group.

Color bar shows correlation coefficient between age and FA. Increased age is associated with diminished anisotropy widely across the brain but most strongly in frontal cortex.

Figure 7. Slope of the regression line for age and anisotropy in the control group.

Color bar shows rate of change of fractional anisotropy (FA*1000) per year.

Figure 8. Correlation between age and anisotropy in the patient group.

Color bar shows correlation coefficient

Figure 9. Slope of the regression line for age and anisotropy in the patient group.

Color bar shows rate of change of fractional anisotropy (FA*1000) by year. Compare with Figure 7.

Figure 10. Slopes of the regression line for age.

Slopes for the regression line for age in controls and patients. Area 1/2/3 labeled as 1 on graphs. Age X Group: *p<0.05, **p<0.01

4. Discussion

The overall lower anisotropy throughout the brain in patients with schizophrenia is consistent with a white matter deficit in the disorder. This is among the largest known samples to date to look at anisotropy in schizophrenia and the widespread results confirm regional anisotropy reduction findings in earlier studies (Kanaan et al., 2005; Kubicki et al., 2007; Schneiderman et al., 2009). The lower levels of anisotropy in particular in the anterior cingulate, orbitofrontal cortex and medial temporal lobe in the patient group reflect theses areas roles in emotional cognition, executive functioning and auditory processing all, which are impaired in schizophrenia (Kubicki et al., 2007).

Our FA differences between normal volunteers and patients are in the same range as obtained in studies using ROI-fiber-based tractography. Left cingulum bundle values using regions of interest defined by tractography (Nestor et al., 2008) were 0.460 ±0.034 for patients and .478 ±0.037 for controls, a difference of 0.018, effect size approximately 0.503. In comparison, our values for left Brodmann area 24 were 0.355 ±0.046 for patients and 0.333 ±0.048 for normals, a difference of 0.022 and an effect size of 0.468. Thus considering the FA of the entire white matter region indentified stereotaxically yields quite similar effects sizes despite slightly larger standard deviations. Since we assessed FA in all white matter, the lower FA and higher SD are to be expected because of the presence of multiple tracts within the area beneath cortical Brodmann areas and the lack of a FA threshold in identifying the region. Nevertheless, our effect sizes are not dissimilar, supporting the validity of our methods.

White matter underlying auditory and somatosensory cortex showed larger reductions in FA than white matter underlying visual cortex. This appears to parallel the incidence of auditory and somatosensory symptomatology in schizophrenia (DSM-IV, 2000). It is of interest that higher FA was observed in the left hemisphere of chronic patients with auditory hallucinations (Hubl et al., 2004). Our left hemisphere auditory area chronic patients had higher anisotropy than the acute patients. We did not however have hallucination frequency data for direct testing of the interesting Hubl data.

With age, a decrease in anisotropy was seen in throughout the brain, in line with gradually decreasing white matter health with age in the mature brain (Pfefferbaum et al., 2000; Nusbaum et al., 2001; Pfefferbaum et al., 2005). Patients with schizophrenia showing similar slopes in the decrease in anisotropy with age as normal controls along with the group differences in anisotropy in general throughout the brain suggests that the white matter deficit in schizophrenia is in place by adulthood and that patients with schizophrenia follow a parallel course with healthy individuals of anisotropy decrease with age in most of the brain. The steeper rate of decrease in anisotropy in age in patients with schizophrenia in area 10 bilaterally and 11 on the left are consistent with diminished emotional reactivity and impaired executive functioning in older patients (Malmo et al., 1951; Pantelis et al., 1997). Among the areas in which the patients with schizophrenia showed an increase in anisotropy in age as compared to the control subjects were areas in the primary auditory cortex, a key area of dysfunction in schizophrenia (Shergill et al., 2000). The increase in anisotropy with age is likely due to the selective decrease in the heath of one group of fibers in those regions. In an area with multiple fibers of different directionality, if a group of fibers with similar directionality is lost, while other fibers with a different directionality remain the anisotropy of the area will show an increase in anisotropy as the remaining fibers now are more homogeneous in their directionality (Basser et al., 2000; Oouchi et al., 2007).

The differences in anisotropy between those patients in the acute phase as compared to those in the chronic phase show that in some regions, the white matter deficit may be continuing to develop after the first break. In particular changes in the anterior cingulate, lateral frontal lobe, inferior parietal, and superior temporal lobe may reflect the worsening of areas of emotional processing, executive functioning and language processing between the acute and chronic states of the disease (Davidson et al., 1995).

4.1 Limitations

The primary limitation of this study is that the patients with schizophrenia were on antipsychotic medication at the time of the study and therefore medication effects cannot be ruled out. This is especially relevant as the chronic group had experienced a longer duration on medication then the acute group. Also it was not possible to do an analysis based on duration of treatment looking at more then the acute versus chronic group effects as the duration of illness was based on self-report, which is increasingly unreliable with increased illness duration, and was unavailable for many of the patients. Among the primary sensory areas, the presence of the largest anisotropy decrease in somatosensory cortex is of interest and might relate to motor and sensory changes associated with long term medication and possibly physical inactivity associated with institutionalization and/or motor retardation. In addition it is also possible that the experience of long term psychiatric care including institutionalization that the schizophrenic group experienced had an effect on the results. Lastly, a subset of the chronic patients may have undergone a dementing course and this could contribute to the acute/chronic differences; without longitudinal neuropsychological assessment this hypothesis cannot be fully evaluated. All of the subjects were imaged using exactly the same protocol and software in place at the study inception (5/30/2003); this allowed the data to be exactly compatible across groups and the accumulation of a large sample size. However the imaging protocol could not be altered during the course of data collection to add methodological improvements and this limited our introducing newer methods.

4.2 Conclusion

In patients with schizophrenia, white matter abnormality, as shown by lowered anisotropy is present throughout adulthood and throughout the brain. Overall, adult patients with schizophrenia show the gradual decline in anisotropy with age that is present in normal subject. In the frontal lobe and temporal lobes, areas of particular relevance to schizophrenia, FA decreases at a faster rate with age suggesting evidence for a continuation of white matter pathology in schizophrenia.

Figure 4. Mean anisotropy differences between acute and chronic patient subgroups.

Color bar shows magnitude of FA differences with red indicating greatest normal volunteer vs. patient difference and, orange, yellow, light green and light blue indicating lesser amounts of difference.

Figure 5. Analysis of covariance comparing acute and chronic patient subgroups.

Color bars indicate two-way ANCOVA results with diagnostic subgroup (acute, chronic) and sex as independent group dimensions and age as a covariate. df = 1, 84 for all regions.

Figure 11. Age Regressions.

Age regression graphs for areas with a significant Age X Group interactions.

Acknowledgements

None

Role of Funding Source

Funding was provided by NIMH Grant P50MH06639; the NIMH had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest

All of the authors have no biomedical financial interests related to this project or potential conflicts of interest.

Contributors

JS designed the study and conducted the analysis. JS and MB wrote the manuscript. EH aided in the revision of the manuscript and provided access to the data for the analysis. JF and VM were responsible for the recruitment and testing of the subjects. CT directed the MRI scanning and data transmission. KC and CT wrote the software to process the data. JS, JZ, CR, RN, YT, EC and JE processed the data.

Bibliography

- Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-IV-TR. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC, Flaum M, Arndt S. The Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms and History (CASH). An instrument for assessing diagnosis and psychopathology. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49(8):615–623. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080023004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basser PJ, Pajevic S, Pierpaoli C, Duda J, Aldroubi A. In vivo fiber tractography using DTMRI data. Magn Reson Med. 2000;44(4):625–632. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200010)44:4<625::aid-mrm17>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchsbaum MS, Friedman J, Buchsbaum BR, Chu KW, Hazlett EA, Newmark R, Schneiderman JS, Torosjan Y, Tang C, Hof PR, Stewart D, Davis KL, Gorman J. Diffusion Tensor Imaging in Schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry. 2006;60(11):1181–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchsbaum MS, Schoenknecht P, Torosjan Y, Newmark R, Chu KW, Mitelman S, Brickman AM, Shihabuddin L, Haznedar MM, Hazlett EA, Ahmed S, Tang C. Diffusion tensor imaging of frontal lobe white matter tracts in schizophrenia. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2006;5:19. doi: 10.1186/1744-859X-5-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchsbaum MS, Tang CY, Peled S, Gudbjartsson H, Lu D, Hazlett EA, Downhill J, Haznedar M, Fallon JH, Atlas SW. MRI white matter diffusion anisotropy and PET metabolic rate in schizophrenia. NeuroReport. 1998;9:425–430. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199802160-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter DM, Tang CY, Friedman JI, Hof PR, Stewart DG, Buchsbaum MS, Harvey PD, Gorman JG, Davis KL. Temporal characteristics of tract-specific anisotropy abnormalities in schizophrenia. NeuroReport. 2008;19(14):1369–1372. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32830abc35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson M, Harvey PD, Powchik P, Parrella M, White L, Knobler HY, Losonczy MF, Keefe RS, Katz S, Frecska E. Severity of symptoms in chronically institutionalized geriatric schizophrenic patients. The American journal of psychiatry. 1995;152(2):197–207. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KL, Stewart DG, Friedman JI, Buchsbaum M, Harvey PD, Hof PR, Buxbaum J, Haroutunian V. White matter changes in schizophrenia: evidence for myelin-related dysfunction. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(5):443–456. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.5.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman JI, Tang C, Carpenter M, Schmeidler J, Flanagan L, Golembo S, Kanellopoulou I, Ng J, Hof PR, Harvey PD, Tsopelas ND, Stewart D, Davis KL. Diffusion tensor imaging findings in first-episode and chronic schizophrenia patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(8):1024–1032. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07101640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazlett EA, Buchsbaum MS, Haznedar MM, Singer MB, Schnur DB, Jimenez EA, Buchsbaum BR, Troyer BT. Prefrontal cortex glucose metabolism and startle eyeblink modification abnormalities in unmedicated schizophrenia patients. Psychophysiology. 1998;35:186–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubl D, Koenig T, Strik W, Federspiel A, Kreis R, Boesch C, Maier SE, Schroth G, Lovblad K, Dierks T. Pathways that make voices: white matter changes in auditory hallucinations. Archives of general psychiatry. 2004;61(7):658–668. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.7.658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson M, Pechaud M, Smith S. BET2: MR-based estimation of brain, skull and scalp surfaces. Eleventh Annual Meeting of the Organization for Human Brain Mapping.2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson M, Smith S. A global optimisation method for robust affine registration of brain images. Med Image Anal. 2001;5(2):143–156. doi: 10.1016/s1361-8415(01)00036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DK, Catani M, Pierpaoli C, Reeves SJ, Shergill SS, O'Sullivan M, Golesworthy P, McGuire P, Horsfield MA, Simmons A, Williams SC, Howard RJ. Age effects on diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imaging tractography measures of frontal cortex connections in schizophrenia. Human brain mapping. 2006;27(3):230–238. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanaan R, Barker G, Brammer M, Giampietro V, Shergill S, Woolley J, Picchioni M, Toulopoulou T, McGuire P. White matter microstructure in schizophrenia: effects of disorder, duration and medication. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194(3):236–242. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.054320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanaan RA, Kim JS, Kaufmann WE, Pearlson GD, Barker GJ, McGuire PK. Diffusion tensor imaging in schizophrenia. Biological psychiatry. 2005;58(12):921–929. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubicki M, McCarley R, Westin CF, Park HJ, Maier S, Kikinis R, Jolesz FA, Shenton ME. A review of diffusion tensor imaging studies in schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41(1–2):15–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumra S, Ashtari M, Cervellione KL, Henderson I, Kester H, Roofeh D, Wu J, Clarke T, Thaden E, Kane JM, Rhinewine J, Lencz T, Diamond A, Ardekani BA, Szeszko PR. White matter abnormalities in early-onset schizophrenia: a voxel-based diffusion tensor imaging study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44(9):934–941. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000170553.15798.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriakopoulos M, Bargiotas T, Barker GJ, Frangou S. Diffusion tensor imaging in schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry. 2008;23(4):255–273. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmo RB, Shagass C, Smith AA. Responsiveness in chronic schizophrenia. J Pers. 1951;19(4):359–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1951.tb01500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh AM, Maniega SM, Lymer GK, McKirdy J, Hall J, Sussmann JE, Bastin ME, Clayden JD, Johnstone EC, Lawrie SM. White matter tractography in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64(12):1088–1092. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitelman SA, Buchsbaum MS, Brickman AM, Shihabuddin L. Cortical intercorrelations of frontal area volumes in schizophrenia. NeuroImage. 2005;27(4):753–770. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitelman SA, Canfield EL, Newmark RE, Brickman AM, Torosjan Y, Chu KW, Hazlett EA, Haznedar MM, Shihabuddin L, Buchsbaum MS. Longitudinal Assessment of Gray and White Matter in Chronic Schizophrenia: A Combined Diffusion-Tensor and Structural Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study. Open Neuroimag J. 2009;3:31–47. doi: 10.2174/1874440000903010031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitelman SA, Newmark RE, Torosjan Y, Chu KW, Brickman AM, Haznedar MM, Hazlett EA, Tang CY, Shihabuddin L, Buchsbaum MS. White matter fractional anisotropy and outcome in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori T, Ohnishi T, Hashimoto R, Nemoto K, Moriguchi Y, Noguchi H, Nakabayashi T, Hori H, Harada S, Saitoh O, Matsuda H, Kunugi H. Progressive changes of white matter integrity in schizophrenia revealed by diffusion tensor imaging. Psychiatry research. 2007;154(2):133–145. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestor PG, Kubicki M, Niznikiewicz M, Gurrera RJ, McCarley RW, Shenton ME. Neuropsychological disturbance in schizophrenia: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Neuropsychology. 2008;22(2):246–254. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.22.2.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusbaum AO, Tang CY, Buchsbaum MS, Wei TC, Atlas SW. Regional and global changes in cerebral diffusion with normal aging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22(1):136–142. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh JS, Kubicki M, Rosenberger G, Bouix S, Levitt JJ, McCarley RW, Westin CF, Shenton ME. Thalamo-frontal white matter alterations in chronic schizophrenia: a quantitative diffusion tractography study. Hum Brain Mapp. 2009;30(11):3812–3825. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oouchi H, Yamada K, Sakai K, Kizu O, Kubota T, Ito H, Nishimura T. Diffusion anisotropy measurement of brain white matter is affected by voxel size: underestimation occurs in areas with crossing fibers. AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology. 2007;28(6):1102–1106. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A0488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantelis C, Barnes TR, Nelson HE, Tanner S, Weatherley L, Owen AM, Robbins TW. Frontal-striatal cognitive deficits in patients with chronic schizophrenia. Brain : a journal of neurology. 1997;120(Pt 10):1823–1843. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.10.1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry R, Oakley A, Perry E. Coronal brain map and dissection guide: Localization of Brodmann areas in coronal sections. 1991 [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum A, Adalsteinsson E, Sullivan EV. Frontal circuitry degradation marks healthy adult aging: Evidence from diffusion tensor imaging. Neuroimage. 2005;26(3):891–899. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum A, Sullivan EV, Hedehus M, Lim KO, Adalsteinsson E, Moseley M. Age-related decline in brain white matter anisotropy measured with spatially corrected echo-planar diffusion tensor imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2000;44(2):259–268. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200008)44:2<259::aid-mrm13>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberger G, Kubicki M, Nestor PG, Connor E, Bushell GB, Markant D, Niznikiewicz M, Westin CF, Kikinis RAJS, McCarley RW, Shenton ME. Age-related deficits in fronto-temporal connections in schizophrenia: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Schizophr Res. 2008;102(1–3):181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneiderman JS, Buchsbaum MS, Haznedar MM, Hazlett EA, Brickman AM, Shihabuddin L, Brand JG, Torosjan Y, Newmark RE, Canfield EL, Tang C, Aronowitz J, Paul-Odouard R, Hof PR. Age and diffusion tensor anisotropy in adolescent and adult patients with schizophrenia. Neuroimage. 2009;45(3):662–671. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.12.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal D, Haznedar MM, Hazlett EA, Entis JJ, Newmark RE, Torosjan Y, Schneiderman JS, Friedman J, Chu KW, Tang CY, Buchsbaum MS, Hof PR. Diffusion tensor anisotropy in the cingulate gyrus in schizophrenia. Neuroimage. 2010;50(2):357–365. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.12.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shergill SS, Brammer MJ, Williams SC, Murray RM, McGuire PK. Mapping auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia using functional magnetic resonance imaging. Archives of general psychiatry. 2000;57(11):1033–1038. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.11.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simeon D, Guralnik O, Hazlett EA, Spiegel-Cohen J, Hollander E, Buchsbaum MS. Feeling unreal: a PET study of depersonalization disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(11):1782–1788. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.11.1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StatSoft I. Statistica. Tulsa, OK: 2003. http://www.statsoft.com. [Google Scholar]

- Stein DJ, Buchsbaum MS, Hof PR, Siegel BV, Jr, Shihabuddin L. Greater metabolic rate decreases in hippocampal formation and proisocortex than in neocortex in Alzheimer's disease. Neuropsychobiology. 1998;37(1):10–19. doi: 10.1159/000026471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang CY, Friedman J, Shungu D, Chang L, Ernst T, Stewart D, Hajianpour A, Carpenter D, Ng J, Mao X, Hof PR, Buchsbaum MS, Davis K, Gorman JM. Correlations between Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI) and Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (1H MRS) in schizophrenic patients and normal controls. BMC Psychiatry. 2007;7:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-7-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voineskos AN, Lobaugh NJ, Bouix S, Rajji TK, Miranda D, Kennedy JL, Mulsant BH, Pollock BG, Shenton ME. Diffusion tensor tractography findings in schizophrenia across the adult lifespan. Brain. 2010;133(Pt 5):1494–1504. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]