Abstract

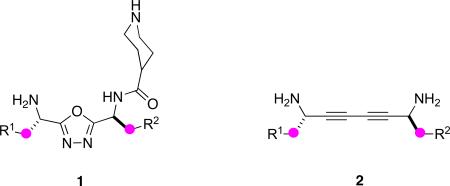

This paper concerns peptidomimetic scaffolds that can present side-chains in conformations resembling those of amino acids in secondary structures without incurring excessive entropic or enthalpic penalties. Compounds of this type are referred to here as minimalist mimics. The core hypothesis of this paper is that small sets of such scaffolds can be designed to analog local pairs of amino acids (including non-contiguous ones) in any secondary structure, ie they are universal peptidomimetics. To illustrate this concept we designed a set of four peptidomimetic scaffolds (1 – 4). Libraries based on these were made bearing side-chains corresponding to many of the protein-derived amino acids. Modeling experiments were performed to give an indication of kinetic and thermodynamic accessibilities of conformations that can mimic secondary structures. Together peptidomimetics based on scaffolds 1 – 4 can adopt conformations that resemble almost any combination of local amino acid side-chains in any secondary structure. Universal peptidomimetics of this kind are likely to be most useful in the design of libraries for high throughput screening against diverse targets. Consequently, data arising from submission of these molecules to the NIH Molecular Libraries Small Molecule Repository (MLSMR) is outlined.

Introduction

Peptides consist of polyamide main-chains bearing substituents. The term “peptidomimetics”1,2 can encompass compounds designed to resemble peptide main-chains, side-chains, or both. Peptidomimetics that can present side-chains on main-chain scaffolds containing amide bonds are ubiquitous because medicinal chemists frequently design analogs of bioactive peptides using this approach. For instance, peptidomimetics involving substitution of amide bonds with surrogates3-7 or transition state analogs,8-13 are common. Peptide-modifications to produce molecules that resemble secondary structures are also widespread. Many helical14-17 and turn18-23 mimics have been prepared like this, frequently by joining two amino acid substituents to constrain peptide fragments in relevant conformations.24-32

An important development in peptide mimicry has been the emergence of analogs of peptide secondary structures that mainly present selected side-chains, ie the main-chain polyamide backbone is abbreviated or totally absent. This approach is appealing because small molecules without polyamide backbones are more likely to be orally bioavailable and proteolytically stable. Early examples of this type of mimic were from Hirschmann and Smith who designed β-turn analogs based-on sugar,33,34 steroid35 or even catechol36 backbones. Similarly, Hamilton37-51 and others52-58 used biphenyl,52 terphenyl38,39,41,47,48,59-61 and related37,39,40,44,47,62,63 scaffolds to mimic helices. In our lab we refer to compounds that present only selected side-chains to resemble peptide secondary structures as minimalist mimics.64,65

Literature on minimalist mimics may give the impression that these types of molecules have one preferred conformation in solution that corresponds to the target secondary structure, but that is not the case. Scaffolds like those in Figure 1a do not exist as a single conformation in solution. They equilibrate between forms representing local minima in Boltzman distributions of energy states, and their global minimum does not necessarily correspond to the target secondary structure. Instead, it is sufficient that the pertinent conformations for mimicry have energies similar to the global minima so that they are populated, and that the transition-state energy barriers to arrive at them can be overcome at ambient temperatures. In other words, that there are no insurmountable thermodynamic or kinetic obstacles to attaining the target conformations. On the other hand, entropic considerations dictate that useful minimalist mimics cannot be totally flexible. Their scaffolds must have limited degrees of freedom to avoid significant entropic penalties on adopting the target secondary structure conformations.

Figure 1.

a Illustrative examples of minimalist mimics. b Favorable conformations of Hamilton's helical mimic shown in a.

One of the original helical mimics by Hamilton is discussed here to illustrate the validity of the assertions above. Figure 1b illustrates facets of the conformational equilibria for this helical mimic. It has only two significant degrees of freedom that affect the orientation of the side chains. Conformers (i) – (iv) approximate to minimum energy forms that alleviate steric interactions between the subsitutedphenyl groups.66 There can be no conformer that is substantially lower in energy than these so they are thermodynamically accessible with respect to the global minimum, ie they will all be significantly populated. In fact, they are approximately equal in energy so the population of each of these conformers is similar. Similarly, the transition state energy barriers that need to be surmounted to equilibrate conformers of such substituted terphenyls can be overcome at room temperature (those energies for terphenyls67,68 depend on the ortho-substitutents involved)69,70 so states (i) – (iv) are also kinetically accessible.

Conformers (i) and (iv) in Figure 1b correspond to helical orientations of the side chains with opposite handedness, while (ii) and (iii) do not display side chains in helical conformations. If this mimic binds to a substrate in the helical conformation (i), for instance, then it would do so by induced fit. This is possible because the target conformation of the mimic is kinetically and thermodynamically accessible, and not because it is thermodynamically preferred.

Identification of conformations in equilibrating ensembles that are both kinetically and thermodynamically accessible can only be done by comparing with similar systems that have been studied experimentally, or via computational methods. Spectroscopic techniques like NMR cannot detect a preferred solution-state conformer of a mimic like that shown in Figure 1b at room temperature, because there is none. Coupling constants and nOe measurements for the scaffolds would reflect conformational averaging and give no useful data. Even if the mimic were crystallized, the conformational state(s) in the crystal would be determined by lattice packing forces. Consequently, computational methods are highly desirable to assess kinetically and thermodynamically accessible solution conformations of minimalist mimics.

This paper outlines structural design criteria for ideal minimalist mimics. In particular, it describes how Cβ - Cβ distances can be used to estimate the correspondence of a minimalist mimic to a particular secondary structure, and how closer consideration of Cα - Cβ vectors can be used as a more stringent test. It then describes how a small number of complementary scaffolds can be used to target any local pair of amino acids in any secondary structure, ie universal mimics.71 Several scaffold types were designed to give a set of putative universal mimics, and libraries of each were generated to prove that a variety of amino acid side chain substituents could be incorporated. Computational methods were identified to assess kinetic and thermodynamic accessibilities of relevant mimic conformations. Finally, an indication of the types of biophysical data that can be obtained with these compounds is presented.

Results

Criteria For The Design Of Minimalist Mimics

To the best of our knowledge, criteria for design of minimalist mimics have never been specifically delineated before. Here we propose the following four structural design criteria:

facile syntheses with most amino acid side chains (eg Arg, Trp, His, etc);

kinetically and thermodynamically accessible conformations for induced fit (ie not too rigid); but also,

only moderate loss of entropy on docking (ie only a few significant degrees of freedom that influence the side chain orientations); and,

appropriate Cα - Cβ coordinates of an accessible conformation of the mimic matching those of the secondary structure.

Other considerations can be important too (eg water solubilities, toxicities, cell permeability, shelf lives). However, these four key parameters define the structural basis for designing minimalist mimics; if one of these is not satisfied, then concerns about the physical and pharmacological characteristics of the compounds may be inconsequential.

The first of the criteria listed above is self-evident from a practical perspective; a scaffold that cannot be easily made with most of the amino acid side chains found in proteins is generally not a good mimic. For instance, designs which only can be conveniently prepared with simple alkyl side-chains would be of limited value if it was necessary to present Asn, Asp, Arg, Gln, His, Lys, Ser, Thr, Trp and/or Tyr side chains.

The second and third criteria listed above relating to the kinetic and thermodynamic accessiblities, and to the significant degrees of freedom, have been addressed above. However, the fourth parameter, relating to correspondence of Cα - Cβ vectors, is unique to this work and warrants further explanation.

Others before us have tried to reduce conformations of secondary structures to the simplest possible terms. For instance, β-turn mimics72 have been classified according to Cα-atom separations73 or Cα - Cβ vectors,74 but, as far as we are aware, there have been no papers that suggest mimics of all secondary structures could be broadly categorized using similar factors.

We recently proposed that Cβ-atom separations are critical in the design of minimalist β-turn mimics.64,65 This is because the Cβ-positions represent the last atoms along the side-chains that are held with some rigidity in these secondary structures; Cβ - Cγ side-chains vectors, and all those further removed from the backbone, are flexible (Figure 2a). Scaffolds A and B were prepared based on this hypothesis (Figure 1b). Here we suggest that in general, accessibility of suitable distances between Cβ-atoms is a necessary condition for the design of minimalist peptidomimetics. This concept is shown for a β-turn in Figure 2, and similar diagrams could be drawn for any secondary structure.

Figure 2.

a A β-turn, and a minimalist mimic consisting of a scaffold affording appropriate Cβ-atom separations. b Minimalist mimics A and B prepared in our group.

Intuitively, Cβ - Cβ distances are useful as a “rough-cut” to gauge the fit of a proposed minimalist mimic to a secondary structure. However, more accurate fitting requires a higher level of sophistication. This comes by considering coordinates of the Cα - Cβ bond vectors of side chains because that parameter reveals how the side chain projects into space as well as Cβ - Cβ distances. Matching Cα - Cβ bond vectors to a particular secondary structure therefore gives a more realistic sense of the validity of the mimic; the only disadvantage is that considerations of Cα - Cβ bond vectors requires computation hence it is less convenient than the intuitive approach based on Cβ - Cβ distances alone.

Analyzing the properties of minimalist mimics led us to conclude there should be special subsets of these compounds that we now call universal peptidomimetics. The next section describes how Cβ - Cβ distances (abbreviated to “βs”) can be used as an intuitive guide to the suitability of possible mimics as secondary structure mimics, then how consideration of Cα - Cβ bond vectors provides a more stringent test.

Candidate Universal Peptidomimetics Selected On The Basis Of C β - Cβ Distances

Minimalist peptidomimetics do not have fixed Cβ - Cβ separations (βs values). For instance, peptidomimetics based on the triazoles B could have several different minimal energy conformations that correspond to preferred orientations of the two side-chains. Indeed, energy barriers for interconversion of between the conformers that place the two Cβ atoms as close, and as far apart, as possible are likely to be relatively insignificant, so this particular type of peptidomimetic could access a range of βs values between these two extremes. In general, extremely contracted and expanded Cβ - Cβ separations can be denoted as βsc and βse, respectively.

To calibrate the capacity of a minimalist peptidomimetic to span different Cβ - Cβ distances, we have defined a parameter called the extension factor, ef = βse/βse where βse and βsc represent maximally extended and contracted Cβ - Cβ separations among the conformers that are both kinetically and thermodynamically accessible (Figure 3). Some peptidomimetics could have kinetically or thermodynamically inaccessible Cβ - Cβ separations between βse and βsc, but for most, all conformations between βse and βsc will be accessible. Peptidomimetics with small extension factors can mimic a limited range of Cβ - Cβ separations, while those with large extension factors correspond to side-chain separations in more secondary structures. However, large extension factors are not always ideal in designs of universal peptidomimetics because they might also represent excessive flexibility in the scaffold, so ef values are predictors of scope rather than quality. On the other hand, scaffolds with large extension factors that can freeze in desired conformations with minimal loss of entropic stabilization are promising for the design of universal peptidomimetics.

Figure 3.

a Conformations of the triazole B can display side-chains aligned with Cβ atoms as close, or as far apart as possible, and these conformations are easily interconverted at room temperature. b Definition of the term “extension factor”.

Four templates 1 – 4 (listed in order of increasing average Cβ - Cβ separations) were conceived using the structural criteria listed for minimalist mimics. Piperidine or piperazine residues in scaffolds 1, 3, and 4 were also included to facilitate assembly of these molecules into heterobivalent forms,64,65,75 but this is of no immediate consequence here.

The following procedure was used to calculate extension factors. First, the significant degrees of freedom in the minimized energy scaffold were identified. Typically these are bonds that can be rotated to adjust the Cβ - Cβ separations. Rotations around these bonds were explored by setting this as the only variable, then monitoring energy as a function of rotation. This led to identification of the conformations that minimize and maximize the βs values, hence the extension factors can be determined. Figure 4 shows these conformations for peptidomimetics 1.

Figure 4.

a “Significant degrees of freedom” for mimic 1 (R1 = R2 = Me); rotation about only these bonds in the scaffold alters the βs. b Conformations corresponding to the βsc and βse in an abbreviated structure of compound 1 (piperidine ring omitted).

Table 1 shows the extension factors deduced for mimics 1, and for A, B, and 2 – 4. The data shown demonstrates that scaffold 1 allows the R1 and R2 side-chains to approach more closely than any other in the series of compounds examined (ie βsc is the smallest located). However, the value for βse is intermediate in the series hence the extension factor for this mimic is not the smallest of these compounds.

Table 1.

Extension factors calculated for the featured peptidomimetics.

| monomer | βsc (Å) | βse (Å) | extension factor ef |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 5.5 | 6.2 | 1.2 |

| B | 5.5 | 7.1 | 1.3 |

| 1 | 5.2 | 7.2 | 1.4 |

| 2 | 7.5 | 8.1 | 1.1 |

| 3 | 7.4 | 14.1 | 1.9 |

| 4 | 12.1 | 15.0 | 1.2 |

Table 2 shows data from modeling experiments we performed to assess Cβ - Cβ separations (βs) for the common elements of secondary structure. It reveals considerable overlap between βs values for different residues in different secondary structures with the range of βs accessible values by each mimic. For instance, the i + 1 to i + 3 βs in a type I β-turn is about equal to that for the i to i + 2 in a γ-turn (ca 7.4 Å), so a scaffold that can access this βs can mimic those side-chains in both secondary structures. Indeed, the extent of Cβ - Cβ separation-overlap in Table 2 indicates almost all the side-chain Cβ - Cβ separations could be mimicked with relatively few peptidomimetics. However, as noted above analyses of Cβ - Cβ separations provide rough approximations for the suitability of minimalist mimics. This parameter does not indicate the orientation of side chains; more stringent tests (based on Cα - Cβ bond vectors) are required for this.

Table 2.

Correspondence of Cβ - Cβ Distances for Peptidomimetics A, B, and 1 – 4 With Common Secondary Structures.a

| structure | sequence | D(Å) | A | B | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-helix | i-i+ 1 | 5.2 | ||||||

| i-i+ 2 | 7.1 | |||||||

| i-i+ 3 | 5.6 | |||||||

| i-i+ 4 | 6.5 | |||||||

| i-i+ 5 | 9.8 | |||||||

| i-i+ 6 | 10.8 | |||||||

| i-i+ 7 | 10.7 | |||||||

| i-i+ 8 | 12.9 | |||||||

| β-turn (type-I) | i-i+ 1 | 5.7 | ||||||

| i-i+ 2 | 5.1 | |||||||

| i-i+ 3 | 5.4 | |||||||

| i+1-i+2 | 5.2 | |||||||

| i+1-i+3 | 7.5 | |||||||

| i+2-i+3 | 5.6 | |||||||

| β-sheet (parallel) | i-i+ 1 | 5.8 | ||||||

| i-i+ 2 | 7.1 | |||||||

| i-i+ 3 | 11.1 | |||||||

| i-i+ 4 | 13.2 | |||||||

| i-i’ | 5.5 | |||||||

| i-i’+1 | 7.2 | |||||||

| i-i’+2 | 9.0 | |||||||

| i-i’+3 | 11.5 | |||||||

| i-i’+4 | 14.4 | |||||||

| β-sheet (anti-parallel) | i-i+ 1 | 5.8 | ||||||

| i-i+ 2 | 6.5 | |||||||

| i-i+ 3 | 11.0 | |||||||

| i-i+ 4 | 12.8 | |||||||

| i-i’ | 4.5 | |||||||

| i-i’+1 | 7.6 | |||||||

| i-i’+2 | 8.9 | |||||||

| i-i’+3 | 12.7 | |||||||

| i-i’+4 | 14.8 | |||||||

| γ-turn (classic) | i-i+ 1 | 5.2 | ||||||

| i-i+ 2 | 7.4 | |||||||

| i+1-i+2 | 5.3 | |||||||

| γ-turn (inverse) | i-i+ 1 | 6.3 | ||||||

| i-i+ 2 | 5.7 | |||||||

| i+1-i+2 | 6.2 |

Each of the four mimic designs 1 – 4 are now considered separately. These scaffolds were very carefully designed to conform to the four parameters delineated above for minimalist peptidomimetics, Syntheses of small libraries based on these scaffolds are described to illustrate a range of amino acid side-chains can be incorporated in each case. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations to explore the kinetic accessibility of the conformers are outlined. Thermodynamic accessibilities of the conformers pertinent to secondary structures are then described on the basis of a molecular dynamics and clustering procedure based on Cα - Cβ bond vectors.

Universal Peptidomimetics 1: 1,3,4-Oxadiazole-based

1,3,4-Oxadiazoles80-82 have been used extensively in the design of pharmaceuticals83,84 and have been shown to have a range of bioactivities and applications including bactericidal, fungicidal, analgesic, anti-inflammatory, antiproteolytic, anticonvulsant, nervous system depressant, sedative, and local anaesthetic.85-89 A 1,3,4-oxadiazole-containing pharmaceutical of current importance is Merck's anti-retroviral HIV drug, Raltegravir. 1,3,4-Oxadiazoles are also a compact 5-membered heterocycle that might be ideal for the formation of universal peptidomimetics.

Scheme 1a describes the procedure used to form the oxadiazole80,83,84,90 mimics 1 via formation of amino acid hydrazides 5,91 coupling these to another amino acid,92 then dehydrative cyclization to give 6. Several sets of conditions were tested for the cyclization step but the triphenylphosphine iodine system shown appeared to give the best results.93-95 Thereafter, a piperidine group was added (so that these monovalent compounds might later be assembled into bivalent ones)65,96 and the protecting groups were removed to give the target molecules 1. This synthetic strategy involved six linear steps and only two chromatographic separations to the protected forms 7. Those intermediates 7 probably have longer shelf-lives than the unprotected compounds 1, and are therefore the preferred way to store these materials. Many of these steps can be performed in parallel to facilitate rapid formation of a chemical library.

Scheme 1.

Two Methods for Preparing Monovalent Mimics 1.

A series of oxadiazole compounds that compliment the ones shown in Scheme 1a was also made (Scheme 1b); these contain N,N-dimethyl serine fragments.97 Three compounds containing this component were prepared via the slightly modified method shown in Scheme 1b. This is very similar to that in 1a, but involves an initial reductive amination step.

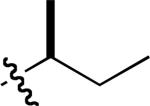

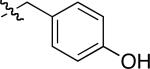

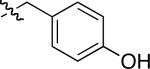

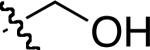

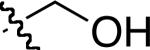

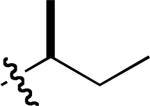

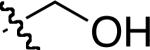

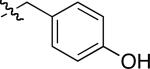

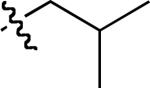

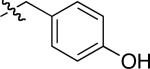

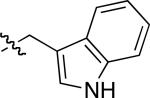

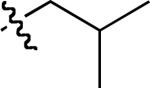

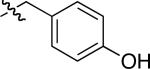

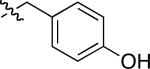

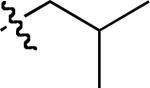

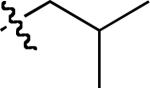

Table 3 lists the side-chains incorporated into the oxadiazole-based mimics 1. They are all derived from protein-based amino acids, including ones that have diverse and relatively reactive functionalities (eg Tyr, Lys, Glu, Ser, Asp, Ile, Thr). The patent literature contains a synthetic route similar to that shown in Scheme 1a,98 but does not encompass functionalized amino acids.

Table 3.

Oxadiazole-based Peptidomimetics 1.

| compound 1 | R1 | R2 |

|---|---|---|

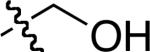

| a |

|

|

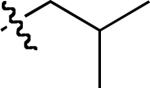

| b |

|

|

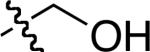

| c |

|

|

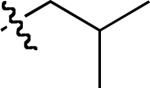

| d |

|

|

| e |

|

|

| f | H |

|

| g |

|

|

| h |

|

|

| i |

|

|

| j |

|

|

| k |

|

|

| l |

|

|

| m |

|

|

| n |

|

|

| o | H |

|

| p |

|

|

| q |

|

|

| r |

|

|

| s |

|

|

| t |

|

|

The following DFT method was used to investigate kinetic accessibility for compounds 1 and all the other scaffolds in the series. Briefly Gaussian 03 was used at the B3LYP level of theory with a 6-31+G(d’) basis set and a polarized continuum solvation model with a dielectric of 80 (see supporting). Figure 5 illustrates the data obtained for mimic 1. The global minimum energy structure that was identified was set to 0 kcal/mol and is shown on the left side of Figure 5a.

Figure 5.

a Transposition of the global minima of 1 into conformation that mimics the i and i + 3 residues in an α-helix by rotation around one of the significant bonds, then the other (ΔGo values shown in kcal/mol). b Overlay of the latter conformation on an ideal α-helix (shown color-coded on the left and in pink on the right).

Consideration of the likely energy barriers corresponding to rotations about the significant degrees of freedom for mimics 1 indicated many conformations other than the global minimum would be accessible. Consideration of Table 1 shows that scaffolds 1 can have Cβ - Cβ separations corresponding to the i to i + 3 residues of an α-helix. The conformation of 1 that best overlays with the Cβ atoms of the i and i + 3 residues in an α-helix is shown on the right hand side of Figure 5a, and an overlay of this mimic with an α-helix is illustrated in Figure 5b. That conformation is then a target for further computational studies to monitor accessibility. Mapping the variation of energy with rotation about the two significant degrees of freedom reveals that it takes 1.31 kcal/mol to overcome one rotational energy barrier, and 2.43 kcal/mol to surmount the other to arrive at the targeted α-helical conformations. Energy barriers of this magnitude are easily surmounted at room temperature so induced fit is possible. Further, the targeted conformation is only 0.41 kcal/mol above the global minima, so these molecules will populate shapes required for docking the i and i + 3 residues in an α-helical form even in the absence of other factors to induce that conformation.

The density functional theory method described above facilitates calculation of transition state energies and relative energies of resting conformations, but it does not show the all the conformations that can be formed and rank their relative energies, ie thermodynamic accessibility. To do that, we used a complementary computational technique: quenched molecular dynamics (QMD).99-102 In this technique the molecule is minimized then subjected to a molecular dynamics run at high temperature (1000 K) for a short time (600 ps); 600 conformational states are recorded during this run (ie every 1 ps) and minimized via molecular mechanics. The lowest energy structures below a user-defined cut-off are selected then clustered into families based on RMS deviations from user-defined atoms (see supporting).

The QMD technique applied to compound 1 (R1 = R2 = Me) illustrates the concept of universal peptidomimetics well. Application of a 0.45 kcal/mol energy cut-off gave 180 (out of 600, see above) minimized conformations. These 180 structures were clustered by overlay of the Cα and Cβ atoms (to within 0.3 Å RMS deviation); this method was chosen because it matches conformations in terms of both Cβ - Cβ distances and Cα - Cβ bond vectors. Sorting in terms of Cα - Cβ bond vectors as well as Cβ - Cβ distances is a refinement that facilitates selection of the sub-sets of conformations with similar side-chain orientations from within the larger category of conformations with similar βs values. This process gave seven families of conformations (Table 4). Family 3 has the most structures that overlaid (ie is the most “populated”) and the minimum energy structure in this family was only 0.15 kcal/mol above the overall minimum energy conformation of those sampled. Conformations within this family overlay well with the i – i + 3 side-chains of an ideal α-helix conformation; this is the same conclusion that was reached using the density functional theory method (Figure 6a; see also Figure 5b above). However, structures in this family also overlay the i – i + 2 side-chains of an ideal inverse γ-turn (Figure 6a). Furthermore, structures in family 5 overlay with an ideal type 1 β-turn at the i + 1 – i + 2 side-chains (Figure 6b). Thus the QMD technique illustrates how conformations of peptidomimetic 1, all of which are less than 0.45 kcal/mol from the overall minimum energy conformation identified, can mimic three secondary structures. It obviates the requirement for exploring conformational space in the density functional theory method described above, ie that the user should have target conformations in mind. QMD facilitates sampling of conformation space, and the DFT approaches can be used to reveal if the desired conformations are kinetically accessible.

Table 4.

QMD analysis of 1.

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | F6 | F7 | |

| population | 66 | 21 | 72 | 11 | 7 | 1 | 2 |

| | |||||||

| ΔE (kcal/mol) from lowest energy conformer overall | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.26 | 0.28 | 0.34 | 0.40 |

| | |||||||

| min. Cβ - Cβ in family | 6.32 | 6.07 | 5.91 | 5.93 | 5.65 | 6.50 | 6.92 |

| max. Cβ - Cβ in family | 6.93 | 6.32 | 6.48 | 6.53 | 5.92 | 6.50 | 6.92 |

| | |||||||

| corresponds toa | α-helix | β-turn | |||||

| γ-turn | |||||||

Representative structures in the families highlighted overlay with the these secondary structures as represented in the figures accompanying this table.

Figure 6.

QMD data for compound 1 (R1 = R2 = Me). a Data from family 3 illustrating overlay with an inverse γ-turn (overlay with a α-helix is shown in Figure 5b). b Data from family 5 illustrating overlay with a type 1 β-turn.

Table 1 was formulated by considering all the βs values that are open to a peptidomimetic and comparing them to common secondary structures. The QMD procedure described above is a more stringent test of whether a compound can be a minimalist of a particular secondary structure. This is because Cα and Cβ atoms are used to cluster conformations to within a specified RMS deviation, and only low energy conformations are considered (because of the application of low cut-off energies in the selection process). Thus the QMD analyses find structures that resemble all the conformations suggested in Table 1, but suggest the most favored of those based on Cβ and Cα atom orientations. Several secondary structures were represented in the most favorable conformations found for compound 1; these include helical and turn conformers (both β- and γ-).

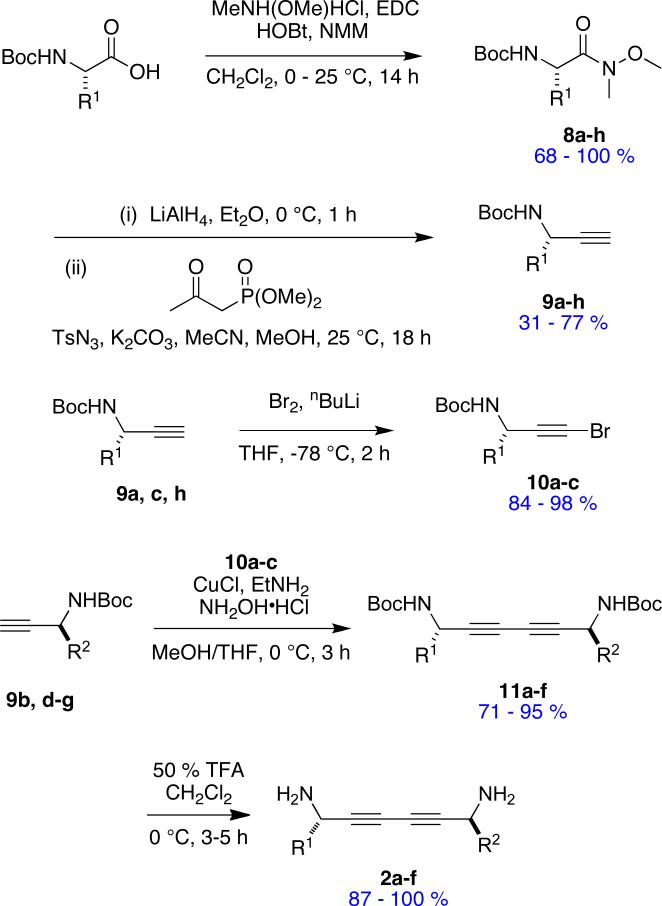

Universal Peptidomimetics 2: 1,3-Butadiyne based

1,3-Butadiynes are atypical scaffolds for pharmaceuticals, but are found in natural products.103 They provide a scaffold suitable for syntheses of minimalist peptidomimetics. One reason for this is that both halves of the molecules 2 can be derived from amino acids, so almost any side-chain can be incorporated. Scheme 2 illustrates how this concept was reduced to practice in a preparation of six peptidomimetics. Conversion of N-Boc amino acids into the corresponding alkynes 9 was achieved via routine chemistry with the Ohira-Bestmann modification104-106 of the Gilbert Seyferth reaction as the pivotal step; this proceeded without racemization. Coupling of two different alkynes to give unsymmetrical diynes rarely proceeds with good selectivity for the heterocoupling. After some experimentation we found it best to convert the alkynes bearing the least functional side-chain to the corresponding 1-bromo derivatives 10, then couple these to the parent alkynes 9 via Cadiot-Chodkiewicz conditions.107,108 This procedure gave the unsymmetrical products 11 in good yields after chromatographic purification. Table 5 shows the side-chains involved in the mimics 2 that were prepared.

Scheme 2.

Method for Preparing Diyne-based Mimics 2.

Table 5.

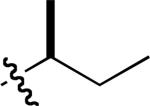

1,3-Butadiyne-based Peptidomimetics 2.

| compound 2 | R1 | R2 |

|---|---|---|

| a |

|

|

| b |

|

|

| c |

|

|

| d |

|

|

| e |

|

|

| f |

|

|

There is only one significant degree of freedom involved in moving the two Cβ-atoms closer or further away from each other, and simultaneously adjusting the orientation of the Cα - Cβ vectors. Consequently, these peptidomimetics are highly constrained to give Cβ separations between 7.5 and 8.1 Å (Figure 7) corresponding to an extension factor of 1.1 (Table 1).

Figure 7.

a Peptidomimetics 2 have only one significant degree of freedom (R1 = R2 = Me shown); b conformations corresponding to the βsc and βse; and, c overlay of one conformation of 2 with the i and i + 2 side-chains of a classical γ-turn.

Cα -Alkyne and alkyne-alkyne bonds in compounds 2 are essentially free to rotate. Nevertheless, for completeness, DFT calculations were performed on this system. They revealed the calculated energy maximum between the two conformations shown in Figure 7b was less than 0.01 kcal/mol, and the conformations were essentially equal in energy. Similarly, QMD calculations indicate that every possible conformation that holds the Cβ-atoms at distances between 7.5 and 8.1 Å has almost the same energy and is equally populated. These data show that this peptidomimetic would surrender very little entropy on induced fit docking that sets its Cβ-atoms between these ranges.

Being so constrained, it would be expected that compounds 2 have relatively low extension factors, and Table 1 shows this parameter is lower than every other mimic in the series A, B, 1 – 4. It follows that this compound should overlay side-chains only with a limited number of secondary structures and, again, Table 1 indicates this is so. However, it still can overlay side-chains with certain elements of β- and γ-turns and β-sheets, ie it is a useful member of the universal peptidomimetic set. For instance, Figure 7 shows the overlay of this with the i and i + 2 side-chains of a classical γ-turn.

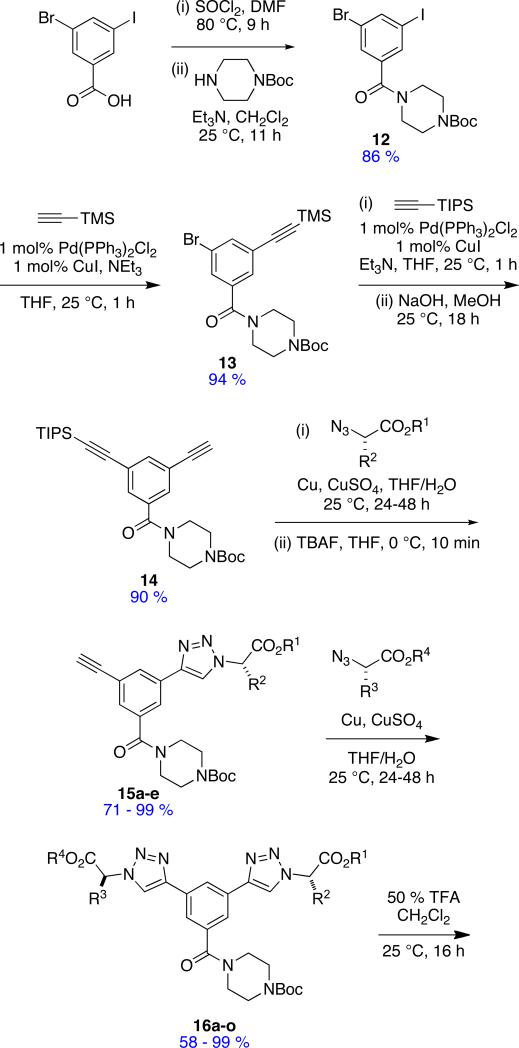

Universal Peptidomimetics 3: “Kinked” Bistriazole-based

Compounds that present side-chains at relatively large separations are necessary in a set of universal peptidomimetics if together they are to be comprehensive mimics of secondary structures. Minimalist mimetics 3 and 4 are included in this set to provide such extended Cβ-separations.

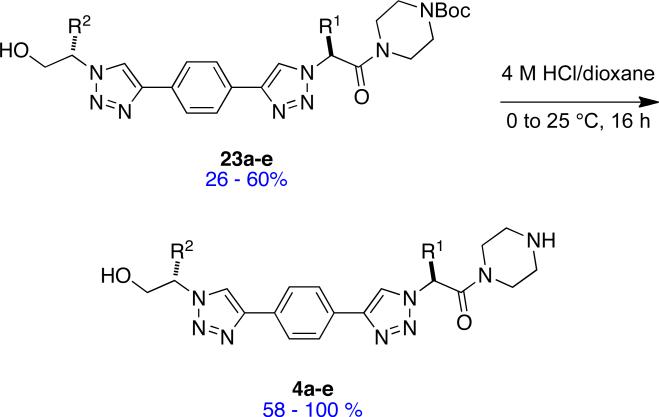

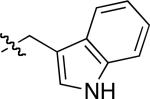

A monoprotected diyne scaffold similar to compound 14 has been prepared before,109 so preparation of that particular intermediate was relatively straight-forward (Scheme 3). Sequential click-deprotect-click reactions using amino acid-derived azides afforded the mimics 3 with a diverse set of side-chain functionalities corresponding to Glu, Ile, Leu, Lys, Ser, Trp and Tyr in the examples we elected to make (Table 6).

Scheme 3.

Method for Preparing Extended Mimics 3.

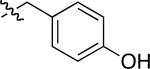

Table 6.

Kinked Bistriazole-based peptidomimetics 3.

| compound 3 | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | Me |

|

|

H |

| b | Me |

|

|

Me |

| c | Me |

|

|

H |

| d | Me |

|

|

H |

| e | Me |

|

|

Me |

| f | H |

|

|

H |

| g | H |

|

|

Me |

| h | H |

|

|

H |

| i | H |

|

|

Me |

| j | Me |

|

|

H |

| k | Me |

|

|

Me |

| l | Me |

|

|

H |

| m | H |

|

|

Me |

| n | H |

|

|

H |

| o | H |

|

|

Me |

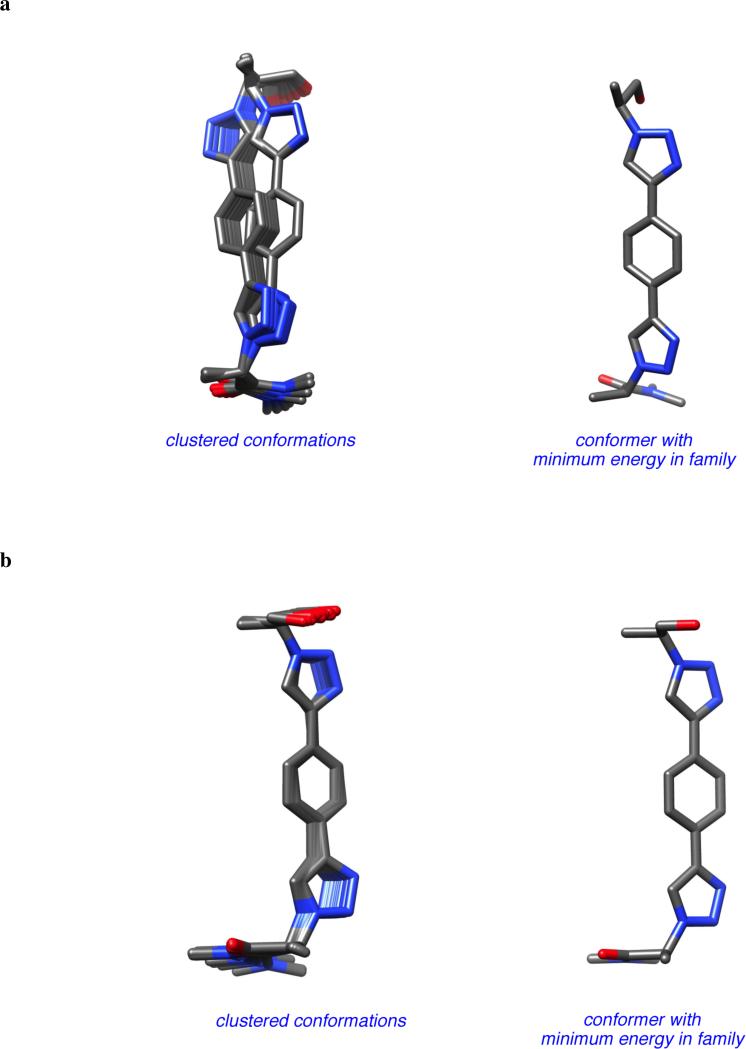

Figure 8 shows the four significant degrees of freedom for the scaffold 3. An extension factor of 1.9, the maximum in the series, was calculated for this framework, indicative of a concertina-like ability to expand and contract the distance between the Cβ-atoms. Table 2 indicates that this design is capable of presenting Cβ-atoms at separations that correspond to distal side-chains in a variety of secondary structures.

Figure 8.

a Peptidomimetics 3 have four significant degrees of freedom (R1 = R2 = Me shown); b conformations corresponding to the βsc and βse in an abbreviated model of structure 3 (piperazine ring omitted).

Calculations for the viability of interconversion of favoured conformers (density functional theory method) show such processes are relatively facile for compounds 3. For instance, changing the global minimum conformation into one that overlays with “cross strand” i - i'+3 residues of an anti-parallel β-sheet involves surmounting an energy barrier of only 4.04 kcal/mol and costs only 0.07 kcal/mol on arrival at that conformation (Figure 9). Thus the conformers are comparable in energy and will interconvert rapidly at room temperature.

Figure 9.

a Transposition of the global minima of 3 into conformation that mimics the i and i' + 3 residues in an anti-parallel β-sheet (ΔGo values shown in kcal/mol). b Overlay of the latter conformation on an anti-parallel β-sheet (shown color coded on the left and in pink on the right).

Table 7 collects the QMD data for an abbreviated structure of peptidomimetic 3 to illustrate the range of conformers that are accessible. Application of an energy cut-off value of 0.3 kcal/mol and clustering to within an RMS deviation of 0.3 Å gave eight major families. Conformers in family 3 overlaid with α-helix i - i + 8 residues, while members of family 4 contained conformers that overlaid well with the i - i' + 3 residues of an anti-parallel β-sheet, just as shown in the density functional theory calculations for this molecule. The lowest energy conformers in families 3 and 4 were only 0.03 and 0.07 kcal/mol less stable than the observed global minimum, respectively. Members of family 7 overlaid well with the i - i + 4 residues of a parallel β-sheet (lowest energy conformer 0.13 kcal/mol above observed global minima).

Table 7.

QMD analysis of 3.a

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | F6 | F7 | F8 | |

| population | 18 | 17 | 13 | 8 | 4 | 11 | 2 | 7 |

| | ||||||||

| ΔE (kcal/mol) from lowest energy conformer overall | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.15 |

| | ||||||||

| min. Cβ - Cβ in family | 13.36 | 12.00 | 12.79 | 12.38 | 11.43 | 11.04 | 11.33 | 9.51 |

| max. Cβ - Cβ in family | 13.77 | 12.60 | 13.65 | 12.92 | 11.84 | 11.73 | 11.39 | 10.17 |

| | ||||||||

| corresponds tob | α-helix | β-sheetc | β-sheetd | |||||

A total of 15 families were identified, but F9 - 15 were omitted for clarity. F9 and F12-15 have only one structure, and F10 and F11 have 4 and 5 structures respectively. All the conformers in F9 – 15 were more than 0.17 kcal/mol less stable than the global minimum.

Representative structures in the families highlighted overlay with the these secondary structures as represented in the figures accompanying this table.

Anti-parallel form.

Parallel form.

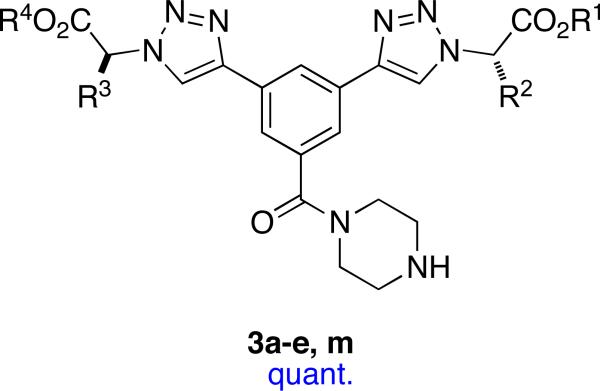

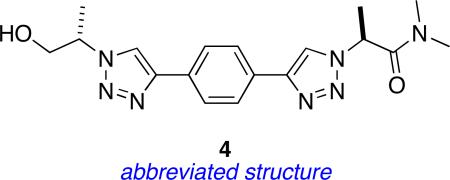

Universal Peptidomimetics 4: “Linear” Bistriazole-based

Peptidomimetics 3 feature a 1,3-disubstituted benzene as the central ring. An analogous 1,4-disubstituted benzene system gives a greater possible span between the two pertinent side-chains; the resulting design is peptidomimetics 4. These compounds can have Cβ - Cβ separations of up to 15.0 Å (Figure 11), but their extension factors are towards the smaller end of the range given in Table 3. Scheme 4 shows the strategy that was performed to obtain these materials; it is similar to that used in Scheme 3 except that the dialkyne framework was built during the synthesis rather than at the beginning. Table 8 summarizes the side-chains involved and the compounds formed.

Figure 11.

a Peptidomimetics 4 have four significant degrees of freedom (R1 = R2 = Me shown); b conformations corresponding to the βsc and βse in an abbreviated model of structure 4 (piperazine ring omitted).

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of the “Linear” Bistriazole-based Peptidomimetics 4.

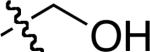

Table 8.

Synthesis of the “Linear” Bistriazole-based Peptidomimetics 4.

| compound 4 | R1 | R2 |

|---|---|---|

| a |

|

|

| b |

|

|

| c |

|

|

| d |

|

|

| e |

|

|

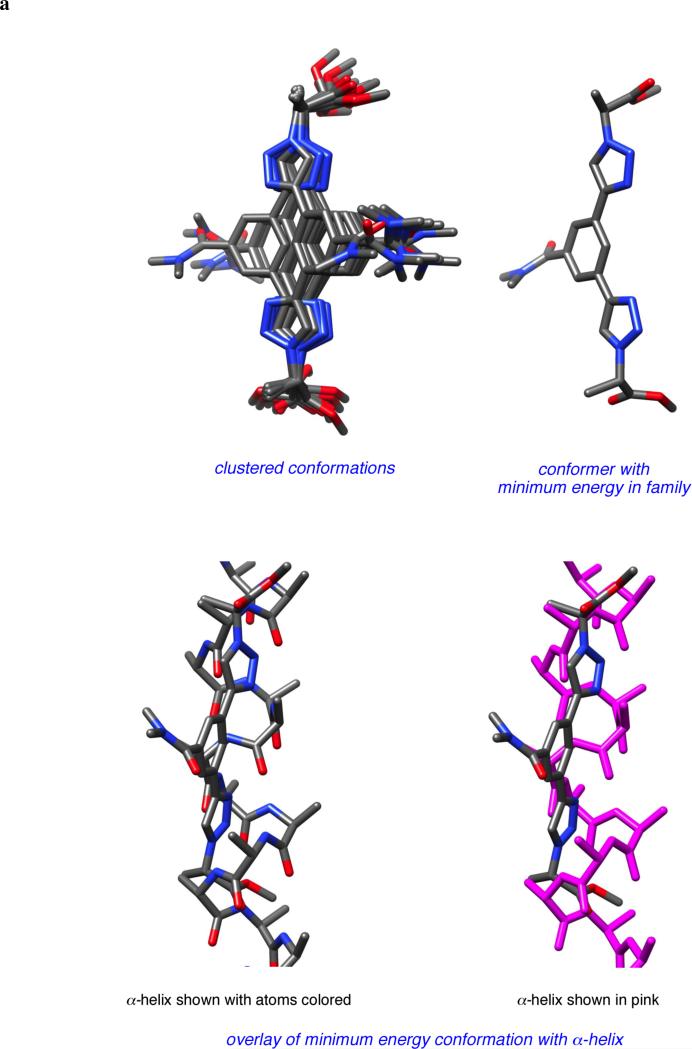

Table 1 indicates peptidomimetics 4 conformers might overlay with distal side-chains of several secondary structures including the i - i+4 Cβ-atoms from the same strand of a parallel β-sheet. Figure 12 shows relatively small energy barriers must be surmounted to reach this conformation from the observed global minimum, and only a 0.46 kcal/mol must be expended to do so.

Figure 12.

a Global minimum conformation of 4 from the density functional theory method must surmount energy barriers of just over 3 kcal/mol to reach conformations that mimic the i and i + 4 residues in a parallel β-sheet (ΔGo values shown in kcal/mol). b Overlay of the latter conformation on a parallel β-sheet (shown color coded on the left and in pink on the right).

QMD analyses of peptidomimetics 4 gave seven major families and, of these, family 2 conformers overlaid well with a parallel β-sheet placing the i and i + 4 Cβ-atoms at appropriate distances (Table 9). Similarly, Family 5 overlaid with an α-helix. Clustered conformations in these two families, and the minimum energy conformation in each, are shown in Figure 13.

Table 9.

QMD analysis of 4.a

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | F6 | F7 | |

| population | 25 | 19 | 16 | 13 | 17 | 5 | 6 |

| | |||||||

| ΔE (kcal/mol) from lowest energy conformer overall | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.24 | 0.33 | 0.50 | 0.85 |

| | |||||||

| min. Cβ - Cβ in family | 13.92 | 13.18 | 14.10 | 13.63 | 12.62 | 13.35 | 13.78 |

| max. Cβ - Cβ in family | 14.48 | 13.56 | 14.32 | 14.24 | 13.13 | 13.44 | 14.11 |

| | |||||||

| corresponds tob | β-sheetc | α-helix | |||||

A total 10 families were identified, but F8 - 10 were omitted. F8 and F10 have only one structure, and F9 has 3. All the conformers in F8 – 10 were at least 0.92 kcal/mol less stable than the global minimum.

Representative structures in the families highlighted overlay with the these secondary structures as represented in the figures accompanying this table.

Parallel form.

Figure 13.

Conformers generated in QMD (see Table 7). a family 2 (overlays with parallel β-sheet as in Figure 12); b family 5 overlays with an α-helix.

Biophysical Data

Scaffolds A and B were originally designed to be mimics of β-turns in neurotrophins. There is considerable evidence that the turn regions in the neurotrophins constitute hot-spots for their interactions with the Trk receptors.110,111 This assertion is supported by two studies from these laboratories that are now published. In the first, fluorescently labeled derivatives of compounds in series A were found to bind cells stably transfected with the TrkA receptor.65 In the second study, compounds in series B were subjected to direct binding, survival and neurito- genic, and biochemical signal transduction assays; these revealed eight agonistic ligands binding to the ectodomain of TrkC. These peptidomimetics afford discrete signals leading to either cell survival or neuritogenic differentiation, ie effects that are both attributed to the parent neurotrophin, NT-3.64

Universal peptidomimetics are likely to be most useful in the design of libraries for high throughput screening against diverse targets. This is because they can mimic a range of secondary structures and present any protein amino acid side-chain; this impacts the diversity space that corresponds to hot-spots112 in protein-protein interactions. Universal peptidomimetics are also likely to be useful for known targets where exact binding conformations are unknown. This represents a large number of situations including all those for which only one protein in a protein-protein interaction has been structurally characterized, and those for which solid-state structure analyses show a possible mode of association that is actually different in solution or in a cellular environment. Conversely, rigid peptidomimetics that are not universal tend to be more useful when the binding conformation is known with a high degree of confidence and can be accurately matched by the mimic.

Motivated by the reasoning presented above, compounds A, B, 1, and 3 (and protected precursors to these) were submitted to the NIH Molecular Libraries Small Molecule Repository (MLSMR) for screening. This is ideal for testing these compounds many of which were not designed for any particular target, just as secondary structure mimics in general. Screening centers test compounds in the MLSMR and publish the data on PubChem; thus samples submitted from this work can be exposed to a wide variety of screens, many more than it would be practical to establish in one lab. These screening centers have already identified cases where our molecules promote or inhibit protein-protein interactions of particular interest; a summary is given in the supporting material, and an abbreviated outline is given here.

An assay for the protein-protein interactions involving the Bcl-2 family proteins Mcl-1 and Bid (PubChem Assay ID, AID, 1021) showed some activities for compounds 1f (PubChem Structure ID, SID, 24708217) and 3e (SID 24707927). Another active compound, the peptidomimetic with scaffold A where R1 = n-butyl, R2 = Lys (SID, 24708065), was detected in a related study, also dealing with interactions between Bcl-2 proteins, but this time Bcl-XL with Bim (AID 2129). This is interesting because scaffolds A, 1, and 3 are all pertinent to helical conformations from the studies presented above, and interactions with helical protein segments in a binding cleft is characteristic of protein-protein interactions involving the Bcl-2 family proteins.47,113

Two assays identified small molecules that inhibited the PB1-domain interaction of MEK5 with either native or a Lys-Ala mutant of MEKK2. Peptidomimetics 3a (SID 24708115), 3b (SID 24708166) andtwo mimics derived from scaffold B (R1 = Leu, R 2 = Trp, SID 24707989 and also R1 = Ile, R2 = Trp, SID 24708162) were active in the assay with the native MEKK2 protein (AID 1531). Compound 3b was also active in the assay using a Lys-Ala mutant of MEKK2 (AID 1530). In confirmation assays, compound 3b showed inhibition of MEK5 with MEK Kinase 2 (WT, AID 1897) with an EC50 value of 5.51 μM. For the inhibition of MEK5 with MEK Kinase 2 (Lys-Ala mutant, AID 1895) the compound was active with an EC50 value of 4.44 μM.

Conclusion

1,3,4-Oxazoline-based mimics 1 were predicted to be useful mimics of many pairs in amino acids in conformations that resemble all of common secondary structures (Table 1). Modeling data for this scaffold indicated that conformations with a diverse set of βs values would be accessible; a typical energy maximum for interconversion of the conformers was only 2.43 kcal/mol (Figure 5). This assertion was born out by the range of conformations that emerged from the QMD studies, which also highlighted low energy conformers that resemble elements of α-helix, γ- and β-turn structures.

There are insignificant barriers to interconversion of the 1,3-butadiyne peptidomimetics 2 between conformational states that resemble amino acid pairs in γ-turns, β-turns, and β-sheets. These are relatively tight minimalist mimics, having only one significant degree of freedom for separation of the Cβ -atoms, hence their small extension factors, but it takes very little energy to interconvert between them. Conversely, the kinked bistriazole scaffolds 3 allow high βs variability. Favored conformations of this scaffold can mimic, for instance, relative close residues of an anti-parallel β-sheet, or closer side-chains in α-helices. All possible Cβ -atom separations are calculated to be accessible, as they are for all the mimics 1 - 4. Mimics 4 are similar to 3 except that they orient the triazole units in para- rather than meta-. This scaffold is a tool for mimicking relatively distal side-chains, even in relatively extended structures like the i and i + 4 Cβ-atoms from one strand of a parallel β-sheet.

Over the last decade there has been considerable interest in generic libraries prepared to supply high throughput screening projects, particularly in the pharmaceutical industry, with “drug-like” compounds to test. The small heterocyclic structures 1 – 4, and B can be decorated with the most pertinent pharmacophores for peptides and protein targets: amino acid side-chain. These specific non-peptidic structures may have some commercial potential, and a patent application on them has been published.114 However, it should not be difficult to conceive other scaffolds for universal peptidomimetics, and it is our hope that the concepts described here will facilitate this process.

Supplementary Material

Figure 10.

Conformers from QMD studies on compounds 3 (see Table 7). Family: a 3 overlaid with α-helix; b 4 overlaid with an anti-parallel β-sheet; and, c 7 overlaid onto a parallel β-sheet.

Acknowledgement

Financial support for this project was provided by the National Institutes of Health (MH070040, GM076261), and the Robert A. Welch Foundation. TAMU/LBMS-Applications Laboratory headed by Dr Shane Tichy and Dr Yohannes Rezenom provided mass spectrometric support and Dr Gillian Lynch at University of Houston supported our QMD work. We thank Shuhei Shimizu for some additional experiments.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Procedures for modeling experiments, synthesis and characterization data for all peptidomimetics are provided. These materials are available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Farmer PS. In: Drug Design. Ariens EJ, editor. Vol. 10. Academic Press; San Diego: 1980. pp. 119–143. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farmer PS, Ariens EJ. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1982;3:362–365. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spatola AF. In: Chemistry and Biochemistry of Amino Acids, Peptides, and Proteins: A Survey of Recent Developments. Weinstein B, editor. Vol. 7. Marcel Dekker; New York: 1983. pp. 267–357. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hruby VJ, Al-Obeidi F, Kazmierski W. Biochem. J. 1990;268:249–262. doi: 10.1042/bj2680249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lam KS, Lebl M, Krchnak V. Chem. Rev. 1997;97:411–448. doi: 10.1021/cr9600114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahn J-M, Boyle NA, MacDonald MT, Janda KD. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2002;2:463–473. doi: 10.2174/1389557023405828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hitotsuyanagi Y, Motegi S, Fukaya H, Takeya K. J. Org. Chem. 2002;67:3266–3271. doi: 10.1021/jo010904i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greenlee WJ. Med. Res. Rev. 1990;10:173–236. doi: 10.1002/med.2610100203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ripka AS, Rich DH. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 1998;2:441–452. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(98)80119-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lebon F, Ledecq M. Curr. Med. Chem. 2000;7:455–477. doi: 10.2174/0929867003375146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bursavich MG, Rich DH. J. Med. Chem. 2002;45:541–558. doi: 10.1021/jm010425b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oishi S, Niida A, Kamano T, Odagaki Y, Tamamura H, Otaka A, Hamanaka N, Fujii N. Org. Lett. 2002;4:1051–1054. doi: 10.1021/ol016834j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rich DH, Sun C-Q, Prasad JVNV, Pathiasseril A, Toth MV, Marshall GR, Clare M, Mueller RA, Houseman K. J. Med. Chem. 1991;34:1222–1225. doi: 10.1021/jm00107a049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patgiri A, Jochim AL, Arora PS. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:1289–1300. doi: 10.1021/ar700264k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang D, Chen K, Kulp JL, III, Arora PS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:9248–9256. doi: 10.1021/ja062710w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang D, Liao W, Arora PS. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:6525–6529. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chapman RN, Dimartino G, Arora PS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:12252–12253. doi: 10.1021/ja0466659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Veber DF, Freidinger RM, Perlow DS, Paleveda WJ, Holly FW, Strachan RG, Nutt RF, Arison BH, Homnick C, Randall WC, Glitzer MS, Saperstein R, Hirschmann R. Nature. 1981;292:55–58. doi: 10.1038/292055a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spanevello RA, Hirschmann R, Raynor K, Reisine T, Nutt RF. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32:4675–4678. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gierasch LM, Deber CM, Madison V, Niu C-H, Blout ER. Biochemistry. 1981;20:4730–4738. doi: 10.1021/bi00519a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bean JW, Kopple KD, Peishoff CE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:5328–5334. [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacDonald M, Vander Velde D, Aube J. Org. Lett. 2000;2:1653–1655. doi: 10.1021/ol005618s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.MacDonald M, Vander Velde D, Aube J. J. Org. Chem. 2001;66:2636–2642. doi: 10.1021/jo001308b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jackson DY, King DS, Chmielewski J, Singh S, Schultz PG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:9391–9392. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bracken C, Gulyas J, Taylor JW, Baum J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:6431–6432. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phelan JC, Skelton NJ, Braisted AC, McDowell RS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:455–460. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cabezas E, Satterthwait AC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:3862–3875. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schafmeister CE, Po J, Verdine GL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:5891–5892. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blackwell Helen E, Sadowsky JD, Howard RJ, Sampson JN, Chao JA, Steinmetz WE, O'Leary DJ, Grubbs RH. J. Org. Chem. 2001;66:5291–5302. doi: 10.1021/jo015533k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kelso MJ, Hoang HN, Oliver W, Sokolenko N, March DR, Appleton TG, Fairlie DP. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 200342:421–424. doi: 10.1002/anie.200390128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shepherd NE, Abbenante G, Fairlie DP. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:2687–2690. doi: 10.1002/anie.200352659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fujimoto K, Oimoto N, Katsuno K, Inouye M. Chem. Commun. 2004;11:1280–1281. doi: 10.1039/b403615h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hirschmann R, Nicolaou KC, Pietranico S, Salvino J, Leahy EM, Sprengeler PA, Furst G, Smith AB., III J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:9217–9218. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hirschmann R, et al. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:12550–12568. Cimplete reference in supporting material.

- 35.Hirschmann R, Sprengeler PA, Kawasaki T, Leahy JW, Shakespeare WC, Amos B, Smith I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:9699–9701. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mowery BP, Prasad V, Kenesky CS, Angeles AR, Taylor LL, Feng J-J, Chen W-L, Lin A, Cheng F-C, Smith AB, III, Hirschmann R. Org. Lett. 2006;8:4397–4400. doi: 10.1021/ol061488x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim IC, Hamilton AD. Org. Lett. 2006;8:1751–1754. doi: 10.1021/ol052956q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yin H, Lee G, Sedey KA, Kutzki O, Park HS, Orner BP, Ernst JT, Wang H-G, Sebti SM, Hamilton AD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:10191–10196. doi: 10.1021/ja050122x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davis JM, Truong A, Hamilton AD. Org. Lett. 2005;7:5405–5408. doi: 10.1021/ol0521228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ernst JT, Becerril J, Park H, Yin H, Hamilton AD. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003;42:535–539. doi: 10.1002/anie.200390154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kutzki O, Park HS, Ernst JT, Orner BP, Yin H, Hamilton AD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:11838–11839. doi: 10.1021/ja026861k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peczuh MW, Hamilton AD. Chem. Rev. 2000;100:2479–2494. doi: 10.1021/cr9900026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilson AJ, Hong J, Fletcher S, Hamilton AD. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2007;5:276–285. doi: 10.1039/b612975g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davis JM, Tsou LK, Hamilton AD. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007;36:326–334. doi: 10.1039/b608043j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Becerril J, Hamilton AD. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:4471–4473. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fletcher S, Hamilton AD. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2007;7:922–927. doi: 10.2174/156802607780906735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yin H, Lee G-I, Hamilton AD. Drug Discovery Res. 2007:281–299. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yin H, Hamilton AD. In: Chemical Biology: From Small Molecules to System Biology and Drug Design. Schreiber SL, Kapoor TM, Wess G, editors. Vol. 1. Wiley-VCH; 2007. pp. 250–269. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Becerril J, Rodriguez JM, Saraogi I, Hamilton AD. Foldamers. 2007:195–228. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rodriguez JM, Hamilton AD. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:8614–8617. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fletcher S, Hamilton AD. J. Royal. Soc., Interface. 2006;3:215–233. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2006.0115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jacoby E. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2002;12:891–893. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(02)00031-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jiang H, Leger J-M, Huc I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:3448–3449. doi: 10.1021/ja029887k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Che Y, Brooks BR, Marshall GR. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des. 2006;20:109–130. doi: 10.1007/s10822-006-9040-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Okuyama M, Laman H, Kingsbury SR, Visintin C, Leo E, Eward KL, Stoeber K, Boshoff C, Williams GH, Selwood DL. Nat. Methods. 2007;4:153–159. doi: 10.1038/nmeth997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ahn J-M, Han S-Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007;48:3543–3547. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Volonterio A, Moisan L, Rebek J., Jr. Org. Lett. 2007;9:3733–3736. doi: 10.1021/ol701487g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shaginian A, Whitby LR, Hong S, Hwang I, Farooqi B, Searcey M, Chen J, Vogt PK, Boger DL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:5564–5572. doi: 10.1021/ja810025g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Orner BP, Ernst JT, Hamilton AD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:5382–5383. doi: 10.1021/ja0025548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ellard JM, Zollitsch T, Cummins WJ, Hamilton AL, Bradley M. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;41:3233–3236. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020902)41:17<3233::AID-ANIE3233>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yin H, Lee G.-i., Park HS, Payne GA, Rodriguez JM, Sebti SM, Hamilton AD. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:2704–2707. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rodriguez JM, Hamilton AD. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:7443–7446. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Marimganti S, Cheemala MN, Ahn J-M. Org. Lett. 2009;11:4418–4421. doi: 10.1021/ol901785v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen D, Brahimi F, Angell Y, Li Y-C, Moscowicz J, Saragovi HU, Burgess K. ACS Chem. Biol. 2009;4:769–781. doi: 10.1021/cb9001415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Angell Y, Chen D, Brahimi F, Saragovi HU, Burgess K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:556–565. doi: 10.1021/ja074717z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tsuzuki S, Uchimaru T, Matsumura K, Mikami M, Tanabe K. J. Chem. Phys. 1999;110:2858–2861. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Johansson MP, Olsen J. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008;4:1460–1471. doi: 10.1021/ct800182e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Baraldi I, Ponterini G. J. Mol. Struct. 1985;23:287–298. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Leroux F. ChemBioChem. 2004;5:644–649. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Grein F. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2002;106:3823–3827. [Google Scholar]

- 71.1 first note.

- 72.Ball JB, Hughes RA, Alewood PF, Andrews PR. Tetrahedron. 1993;49:3467–3478. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Garland SL, Dean PM. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 1999;13:469–483. doi: 10.1023/a:1008045403729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Garland SL, Dean PM. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 1999;13:485–498. doi: 10.1023/a:1008014620568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Reyes SJ, Burgess K. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006;35:416–423. doi: 10.1039/b516721n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kee KS, Jois Seetharama DS. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2003;9:1209–1224. doi: 10.2174/1381612033454900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vass E, Hollosi M, Besson F, Buchet R. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:1917–1954. doi: 10.1021/cr000100n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Accelrys I. 2010.

- 79.Parisien M, Major F. Beta-Sheet's World website. 2004.

- 80.Weaver GW. Sci. Synth. 2004;13:219–251. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Stolle R. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1899;32:797–798. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pellizzari G. Real. Accad. dei Lincei. 1899;8:327–332. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hetzheim A, Moeckel K. Adv. Heterocycl. Chem. 1966;7:183–224. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hill J. Compr. Heterocycl. Chem. II. 1996;4:267–287. 905–1006. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Roda KP, Vansdadia RN, Parekh H. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 1988;65:807–809. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Raman K, Parmar SS, Salzman SK. J. Pharm. Sci. 1989;78:999–1002. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600781206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ergenc N, Buyuktimkin S, Capan G, Baktir G, Rollas S. Pharmazie. 1991;46:290–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Saxena VK, Singh AR, Agarwai RK, Mehra SC. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 1983;60:575–577. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mazzone G, Bonina F, Puglisi G, Panico AM, Arrigo Reina R. Farmaco, Ed. Sci. 1984;39:414–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Jakopin Z, Dolenc MS. Curr. Org. Chem. 2008;12:850–898. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Moutevelis-Minakakis P, Photaki I. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 1985:2277–2281. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhang X, Breslav M, Grimm J, Guan K, Huang A, Liu F, Maryanoff CA, Palmer D, Patel M, Qian Y, Shaw C, Sorgi K, Stefanick S, Xu D. J. Org. Chem. 2002;67:9471–9474. doi: 10.1021/jo026288n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mann E, Kessler H. Org. Lett. 2003;5:4567–4570. doi: 10.1021/ol035673b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Davies JR, Kane PD, Moody CJ. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:3967–3977. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wipf P, Miller CP. J. Org. Chem. 1993;58:3604–3606. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Pattarawarapan M, Reyes S, Xia Z, Zaccaro MC, Saragovi HU, Burgess K. J. Med. Chem. 2003;46:3565–3567. doi: 10.1021/jm034103e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Paquette LA, Mitzel TM, Isaac MB, Crasto CF, Schomer WW. J. Org. Chem. 1997;62:8960. doi: 10.1021/jo970274d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Coburn CA, Nantermet PG, Rajapakse HA, Selnick HG, Stauffer SR. A2. Merck & Co., Inc.; 2006. p. 47. US Patent. WO 2006/078576. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pettitt BM, Matsunaga T, Al-Obeidi F, Gehrig C, Hruby VJ, Karplus M. Biophys. J. 1991;60:1540–1544. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82188-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.O'Connor SD, Smith PE, Al-Obeidi F, Pettitt BM. J. Med. Chem. 1992;35:2870–2881. doi: 10.1021/jm00093a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Phillips JC, Braun R, Wang W, Gumbart J, Tajkhorshid E, Villa E, Chipot C, Skeel RD, Kale L, Schulten K. J. Comput. Chem. 2005;26:1781–1802. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. J. Mol. Graph. 1996;14:33–38. 27–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Shi Shun ALK, Tykwinski RR. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:1034–1057. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ohira S. Synth. Commun. 1989;19:561–564. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Eymery F, Iorga B, Savignac P. Synthesis. 2000:185–213. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Roth GJ, Liepold B, Muller SG, Bestmann HJ. Synthesis. 2004:59–62. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Siemsen P, Livingston RC, Diederich F. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2000;39:2632–2657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Yun H, Danishefsky SJ. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:4519–4522. doi: 10.1021/jo0341665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Tobe Y, Utsumi N, Kawabata K, Naemura K. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:9325–9328. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Pattarawarapan M, Burgess K. J. Med. Chem. 2003;46:5277–5291. doi: 10.1021/jm030221q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Saragovi HU, Burgess K. Exp. Opin. Ther. Patents. 1999;9:737–751. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Leigh DA. Chem. Biol. 2003;10:1143–1144. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Youle RJ, Strasser A. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:47–59. doi: 10.1038/nrm2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Burgess K. A1. Texas A&M University System, College Station, TX; 2009. pp. 1–103. US Patent. US 2009/0264315. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.